Competition of the Addition/Cycloaddition Schemes in the Reaction Between Fluorinated Nitrones and Arylacetylenes: Comprehensive Experimental and DFT Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

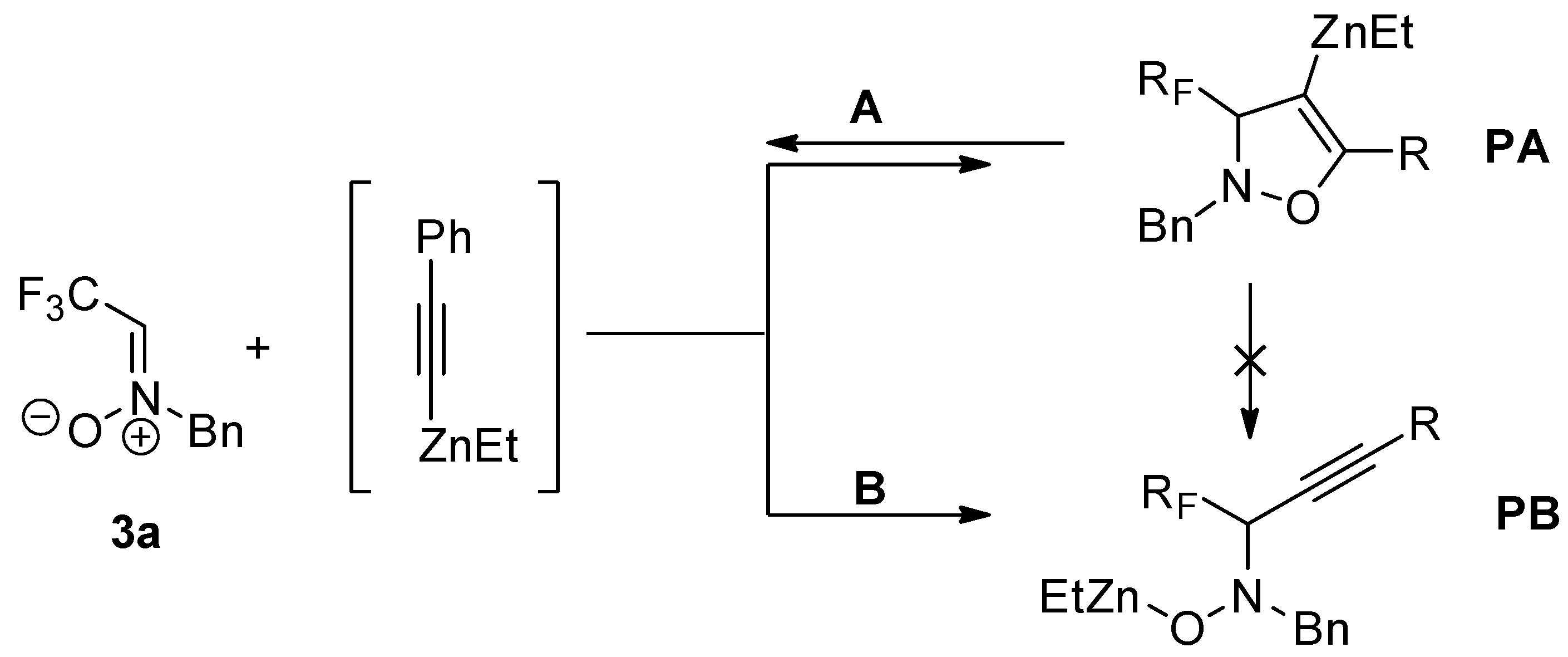

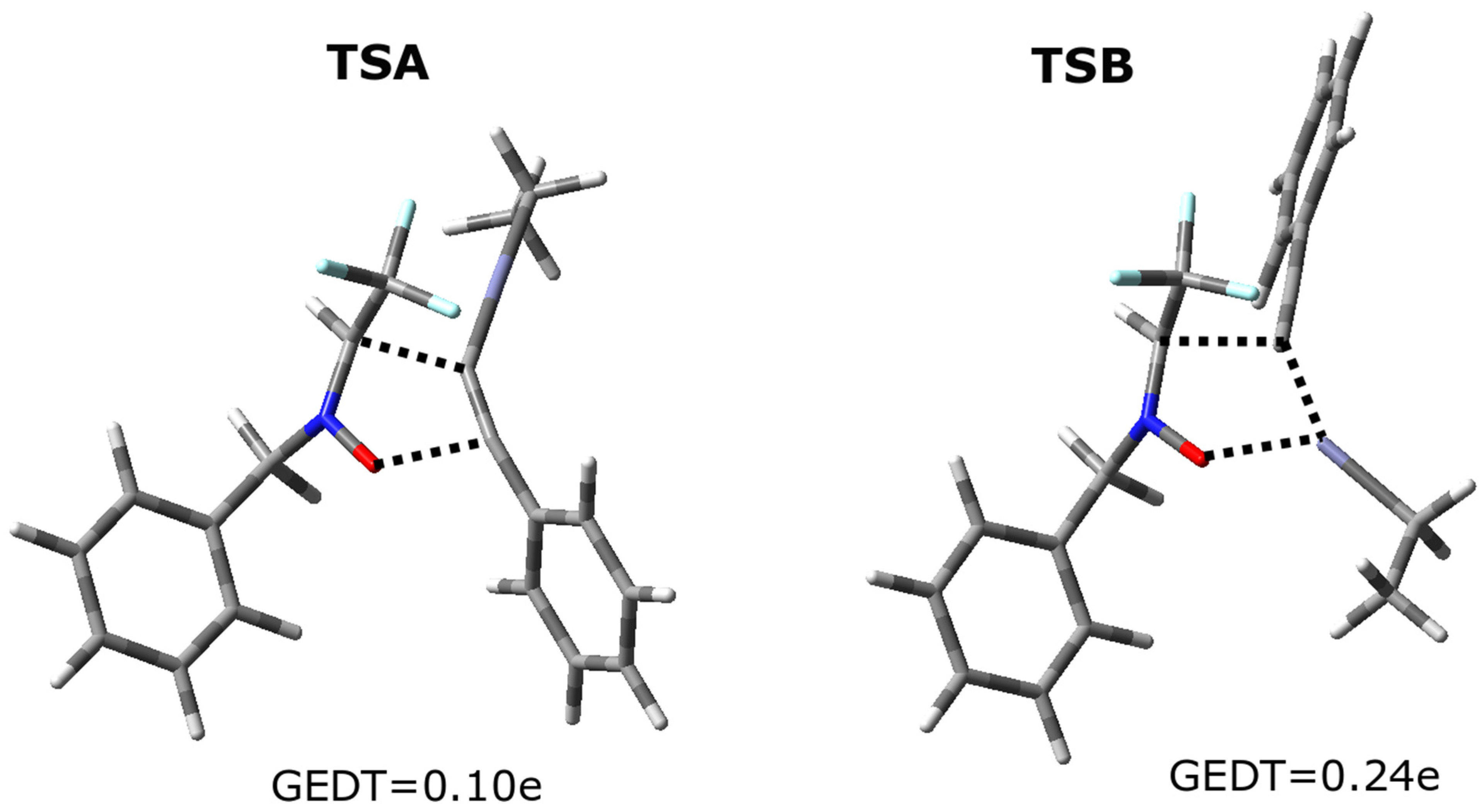

2.1. Additions of Acetylenes to Fluorinated Nitrones

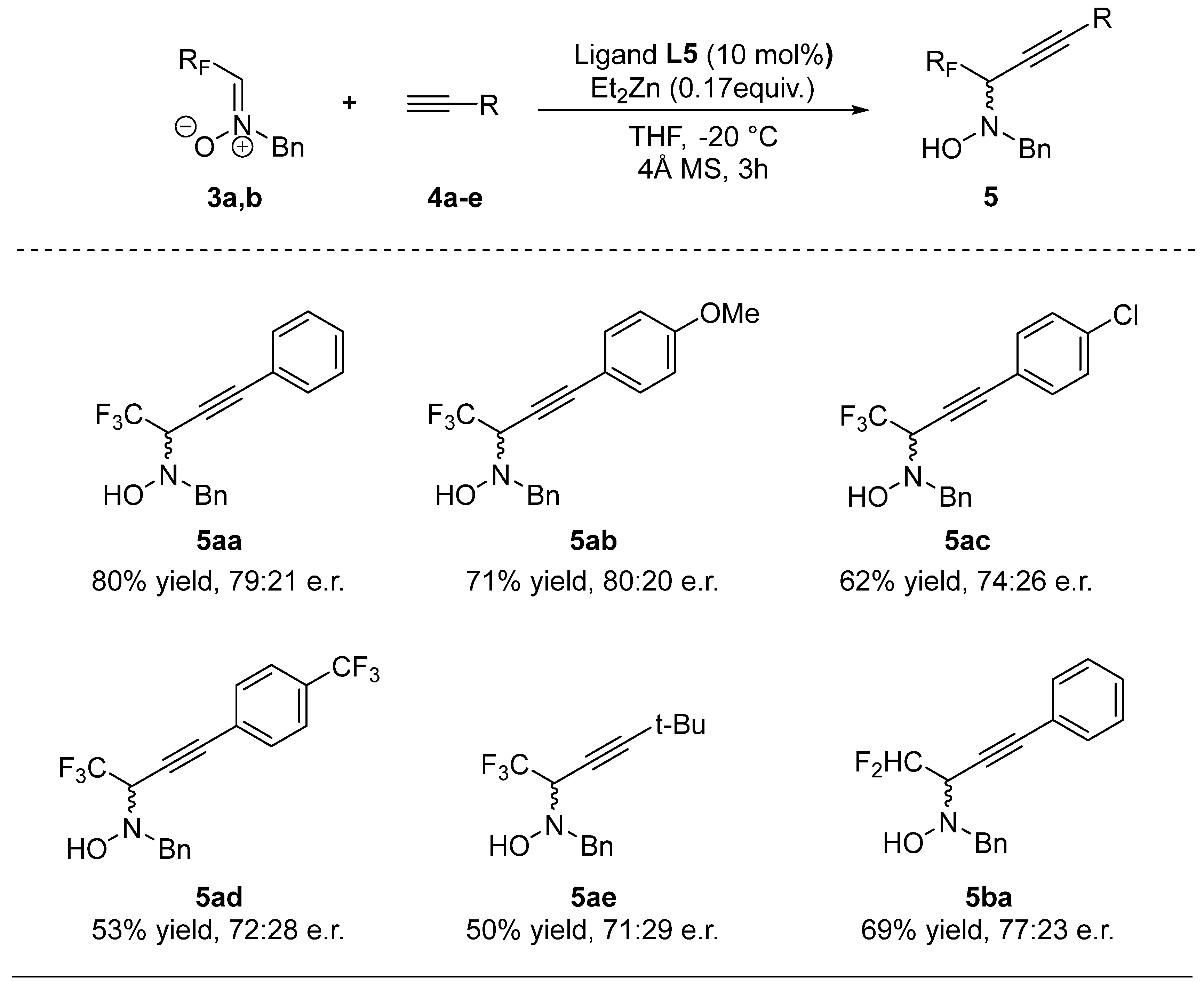

2.2. Enantioselective Protocol

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Information

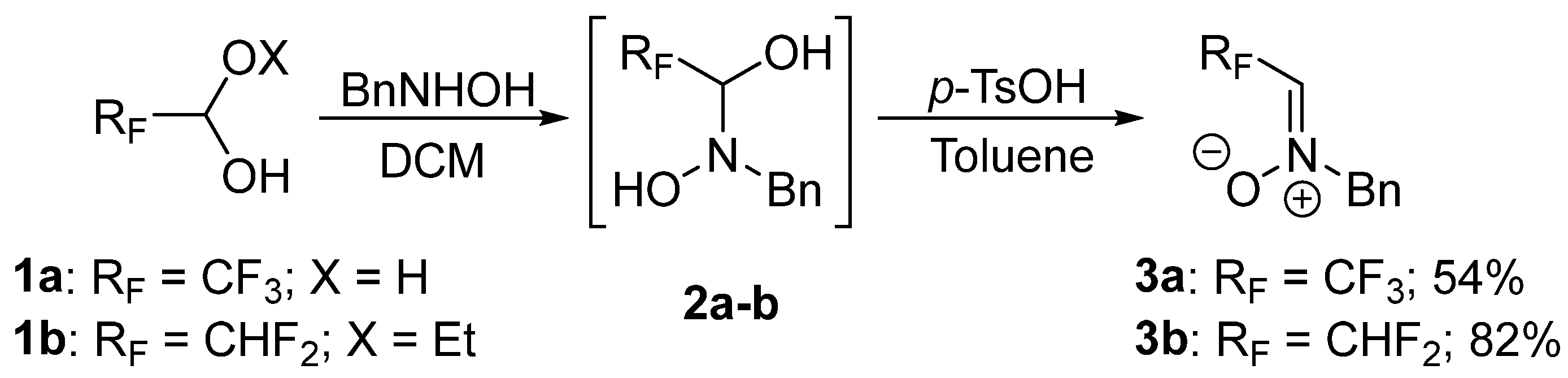

3.2. Synthesis of Nitrones Derived from Trifluoroacetaldehyde and Difluoroacetaldehyde

3.3. Reactions of Nitrones 3 Derived from Fluorinated Aldehydes with Acetylenes 4

- (a)

- Reactions leading to racemic products

- (b)

- Enantioselective reactions

3.4. Computational Study

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maienfish, P.; Hall, R.G. The importance of fluorine in the life science industry. Chimia 2004, 58, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, P. Modern Fluoroorganic Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bégué, J.-P.; Bonnet-Delpon, D. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry of Fluorine; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, A.S.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, S.; Sukumaran, S.; Koyiparambath, V.P.; Pappachen, L.K.; Rangarajan, T.M.; Kim, H.; Mathew, B. FDA-Approved Trifluoromethyl Group-Containing Drugs: A Review of 20 Years. Processes 2022, 10, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuer, H. Nitrile Oxides, Nitrones and Nitronates in Organic Synthesis: Novel Strategies in Synthesis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Murahashi, S.-I.; Imada, Y. Synthesis and transformations of nitrones for organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 4684–4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Hamme II, A.T. Zinc mediated direct transformation of propargyl N-hydroxylamines to α,β-unsaturated ketones and mechanistic insight. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 1086–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Chit Tsui, G. Copper-mediated domino cyclization/trifluoromethylation of propargylic N-hydroxylamines: Synthesis of 4-trifluoromethyl-4-isoxazolines. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 2971–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariyama, T.; Kusakabe, T.; Sato, K.; Funatogawa, M.; Lee, D.; Takahashi, K.; Kato, K. Pd(II)-Catalyzed ligand-controlled synthesis of 2,3-dihydroisoxazole-4-carboxylates and bis(2,3-dihydroisoxazol-4-yl)methanones. Heterocycles 2016, 93, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Wada, N.; Soeta, T.; Fujinami, S.; Inomata, K.; Ukaji, Y. One-pot stereoselective synthesis of 2-acylaziridines and 2-acylpyrrolidines from N-(propargylic)hydroxylamines. Chem. Asian J. 2013, 8, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norihiro, W.; Kentaro, K.; Yutaka, U.; Katsuhiko, I. Selective Transformation of N-(propargylic)hydroxylamines into 4-isoxazolines and acylaziridines promoted by metal salts. Chem. Lett. 2011, 40, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C.R.; Vijaykumar, J.; Jithender, E.; Pavan, G.; Reddy, K.; Grée, R. One-pot synthesis of 3,5-disubstituted isoxazoles from propargylic alcohols through propargylic N-hydroxylamines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 2012, 5767–5773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayon, E.; Szymczyk, M.; Gérard, H.; Vrancken, E.; Campagne, J.-M. Stereoselective and catalytic access to β-enaminones: An entry to pyrimidines. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 9205–9220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlostoń, G.; Obijalska, E.; Celeda, M.; Mittermeier, V.; Linden, A.; Heimgartner, H. 1,3-Dipolar cycloadditions of fluorinated nitrones with thioketones. J. Fluor. Chem. 2014, 165, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, M.K.; Mlostoń, G.; Obijalska, E.; Linden, A.; Heimgartner, H. First application of fluorinated nitrones for the synthesis of fluoroalkylated β-lactams via the Kinugasa reaction. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 5305–5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, R. A new mechanistic insight on β-lactam systems formation from 5-nitroisoxazolidines. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 50070–50072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Ohsuga, M.; Sugimoto, Y.; Okafuji, Y.; Mitsuhashi, K. Applications of the fluorinated 1,3-dipolar compounds as the building blocks of the heterocycles with fluorine groups. Part XII. Synthesis of trifluoromethylisoxazolines and their rearrangement into trifluoromethylaziridines. J. Fluor. Chem. 1988, 39, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Sugimoto, Y.; Okafuji, Y.; Tachikawa, M.; Mitsuhashi, K. Regio- and stereoselectivity of cycloadditions of C-(Trifluoromethyl)nitrone with olefins. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1989, 26, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milcent, T.; Hinks, N.; Bonnet-Delpon, D.; Crousse, B. Trifluoromethyl nitrones: From fluoral to optically active hydroxylamines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 3025–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Nie, J.; Zhang, F.-G.; Ma, J.-A. Zinc mediated enantioselective addition of terminal 3-en-1-ynes to cyclic trifluoromethyl ketimines. J. Fluor. Chem. 2018, 208, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, D.E.; Fässler, R.; Carreira, E.M. Catalytic in Situ Generation of Zn(II)-Alkynilides under Mild Conditions: A Novel C=N Addition Process Utilizing Terminal Acetylenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 11245–11246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschwanden, P.; Frantz, D.E.; Carreira, E.M. Synthesis of 2,3-Dihydroisoxazoles from Propargylic N-Hydroxylamines via Zn(II)-Catalyzed Ring-Closure Reaction. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 2331–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabuga, S.; Karakaya, I.; Ulukanli, S. 3-Aminoquinazolinones as chiral ligands in catalytic enantioselective diethylzinc and phenylacetylene addition to aldehydes. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2014, 25, 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, A.; Sadowski, M.; Jasiński, R. Selectivity and molecular mechanism of the Au(III)-catalyzed [3+2] cycloaddition reaction between (Z)-C,N-diphenylnitrone and nitroethene in the light of the molecular electron density theory computational study. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2024, 60, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M. A Useful Classification of Organic Reactions Based on the Flux of the Electron Density. Sci. Radices 2023, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Mohammad-Salim, H.A.; Acharjee, N. Unveiling substituent effects in [3+2] cycloaddition reactions of benzonitrile N-oxide and benzylideneanilines from the molecular electron density theory perspective. Sci. Radices 2023, 2, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, K.; Sadowski, M. Regio- and stereoselectivity of [3+2] cycloaddition reactions between (Z)-1-(anthracen-9-yl)-N-methyl nitrone and analogs of trans-β-nitrostyrene on the basis of MEDT computational study. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2023, 59, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafaa, F.; Nacereddine, A.K. A molecular electron density theory study of mechanism and selectivity of the intramolecular [3+2] cycloaddition reaction of a nitrone–vinylphosphonate adduct. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2023, 59, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, A.L.; Paixão, M.W.; Westermann, B.; Schneider, P.H.; Wessjohann, L.A. Acceleration of Arylzinc Formation and Its Enantioselective Addition to Aldehydes by Microwave Irradiation and Aziridine-2-methanol Catalysts. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 2879–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlos, A.M.M.; Contreira, M.E.; Martins, B.S.; Immich, M.F.; Moro, A.V.; Lüdtke, D.S. Catalytic asymmetric arylation of aliphatic aldehydes using a B/Zn exchange reaction. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 1202–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-C.; Wang, Y.-H.; Li, G.-W.; Sun, P.-P.; Tian, J.-X.; Lu, H.-J. Applications of conformational design: Rational design of chiral ligands derived from a common chiral source for highly enantioselective preparations of (R)- and (S)-enantiomers of secondary alcohols. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2011, 22, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzyński, S.; Leśniak, S.; Pieczonka, A.M.; Rachwalski, M. N-Trityl-aziridinyl alcohols as highly efficient chiral catalysts in asymmetric additions of organozinc species to aldehydes. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2015, 26, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzyński, S.; Utecht, G.; Leśniak, S.; Rachwalski, M. Highly enantioselective asymmetric reactions involving zinc ions promoted by chiral aziridine alcohols. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2017, 28, 1774–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini, B.F.; Capitò, E.; Comes-Franchini, M.; Fochi, M.; Riccia, A.; Zwanenburg, B. Aziridin-2-yl methanols as organocatalysts in Diels–Alder reactions and Friedel–Crafts alkylations of N-methyl-pyrrole and N-methyl-indole. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2006, 17, 3135–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, B.M.; Hung, C.-I.J.; Koester, D.C.; Miller, Y. Development of Non-C2-symmetric ProPhenol Ligands. The Asymmetric Vinylation of N-Boc Imines. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 3778–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-Y.; Hua, Y.-Z.; Wang, M.-C. Asymmetric 1,6-Conjugate Addition of para-Quinone Methides for the Synthesis of Chiral β,β-Diaryl-α-Hydroxy Ketones. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 09. Revision D.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Domingo, L.R. A new C–C bond formation model based on the quantum chemical topology of electron density. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 32415–32428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalmani, G.; Frisch, M.J.J. Continuous surface charge polarizable continuum models of solvation. I. General formalism. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 114110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supranovich, V.I.; Levin, V.V.; Struchkova, M.I.; Dilman, A.D. Photocatalytic Reductive Fluoroalkylation of Nitrones. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 840–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, D.W.; Owens, J.; Hiraldo, D. α-(Trifluoromethyl)amine Derivatives via Nucleophilic Trifluoromethylation of Nitrones. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 2572–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, T.; Moriyasu, K.; Ishihara, T. A Remarkable Access to γ-Fluoroalkylated Propargylamine Derivatives or Fluoroalkylated Dihydroisoxazoles via the Reaction of Fluoroalkylated Acetylides with Various Nitrones. Synthesis 2009, 7, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agilent. CrysAlis PRO; Agilent Technologies Ltd.: Yarnton, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT–Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Cryst. 2015, A71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hübschle, C.B.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Dittrich, B. ShelXle: A Qt graphical user interface for SHELXL. J. Appl. Cryst. 2011, 44, 1281–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Cryst. 2015, C71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry | Ligand | M | Yield [%] b | e.r. [%] c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L1 | Et2Zn | 51 | 54:46 |

| 2 | L2 | Et2Zn | 58 | 59:41 |

| 3 | L3 | Et2Zn | 38 | 51:49 |

| 4 | L4 | Et2Zn | 60 | 57:43 |

| 5 | L5 | Et2Zn | 67 | 72:28 |

| 6 d | L5 | Zn(OTf)2 | 21 | 52:48 |

| Entry | Ligand (mol%) | Solvent | Time [h] | T [°C] | Yield [%] c | e.r. [%] d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | THF | 3 | 20 | 67 | 72:28 |

| 2 | 10 | DCM | 3 | 20 | 56 | 64:36 |

| 3 | 10 | Toluene | 3 | 20 | 49 | 59.5:40.5 |

| 4 | 10 | Et2O | 3 | 20 | 23 | 55:45 |

| 5 | 10 | THF | 4 | 0 | 70 | 74:26 |

| 6 | 10 | THF | 4 | −20 | 76 | 76.5:23.5 |

| 7 | 10 | THF | 4 | −78 | 68 | 75:25 |

| 8 | 20 | THF | 4 | −20 | 73 | 76:24 |

| 9 | 5 | THF | 5 | −20 | 77 | 73.5:26.5 |

| 10 b | 10 | THF | 4 | −20 | 80 | 79:21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jarzyński, S.; Krempiński, A.; Pietrzak, A.; Jasiński, R.; Obijalska, E. Competition of the Addition/Cycloaddition Schemes in the Reaction Between Fluorinated Nitrones and Arylacetylenes: Comprehensive Experimental and DFT Study. Molecules 2025, 30, 4578. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234578

Jarzyński S, Krempiński A, Pietrzak A, Jasiński R, Obijalska E. Competition of the Addition/Cycloaddition Schemes in the Reaction Between Fluorinated Nitrones and Arylacetylenes: Comprehensive Experimental and DFT Study. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4578. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234578

Chicago/Turabian StyleJarzyński, Szymon, Andrzej Krempiński, Anna Pietrzak, Radomir Jasiński, and Emilia Obijalska. 2025. "Competition of the Addition/Cycloaddition Schemes in the Reaction Between Fluorinated Nitrones and Arylacetylenes: Comprehensive Experimental and DFT Study" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4578. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234578

APA StyleJarzyński, S., Krempiński, A., Pietrzak, A., Jasiński, R., & Obijalska, E. (2025). Competition of the Addition/Cycloaddition Schemes in the Reaction Between Fluorinated Nitrones and Arylacetylenes: Comprehensive Experimental and DFT Study. Molecules, 30(23), 4578. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234578