Chemical Composition, Biological Activity, and In VivoToxicity of Essential Oils Extracted from Mixtures of Plants and Spices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Chemical Analysis of EOs

2.1.1. Chemical Composition of EOs

2.1.2. Chemical Class Composition of EOs

2.2. Antimicrobial Activity of EOs

2.3. Virucidal Activity

2.4. Antioxidant Activity

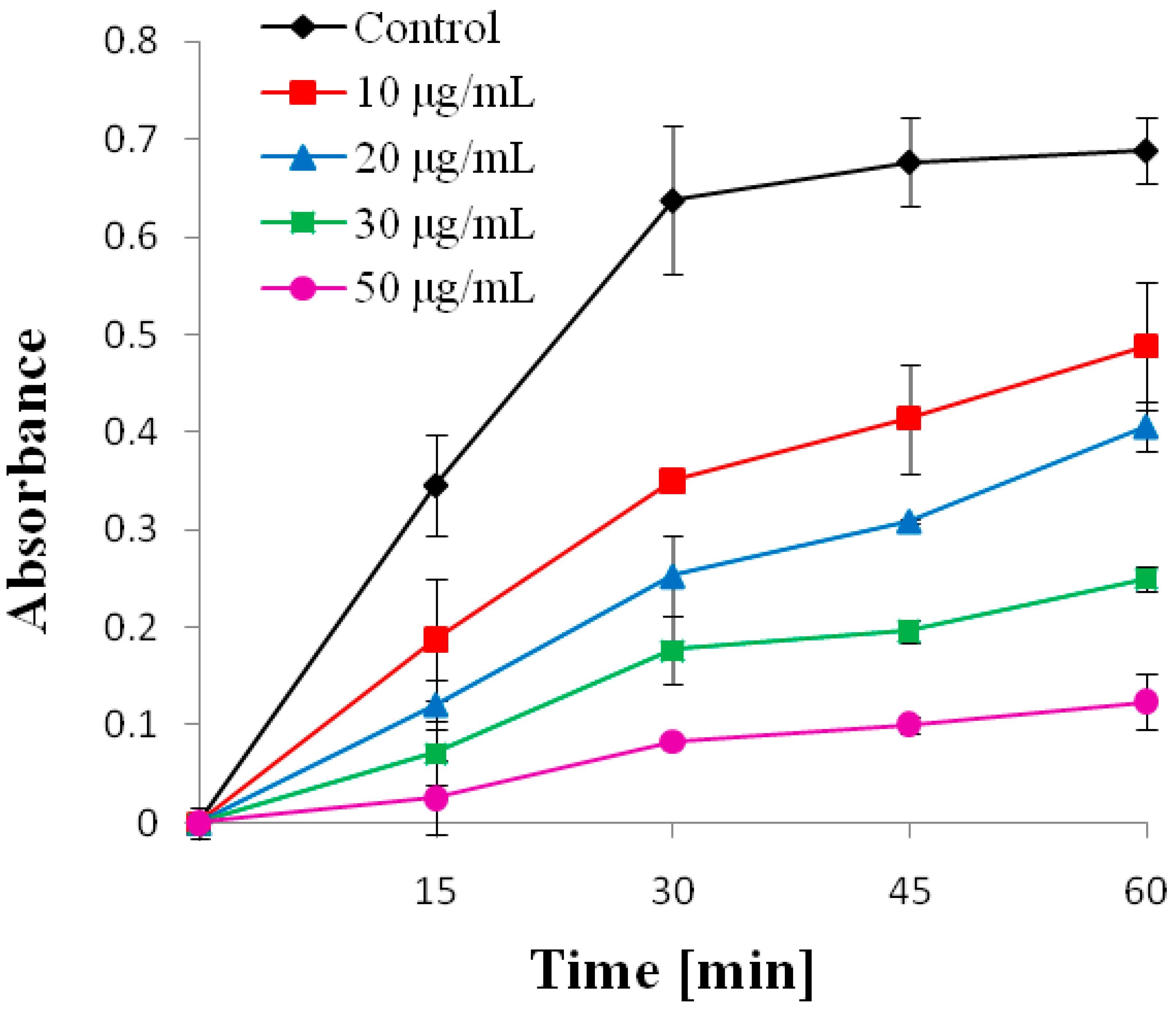

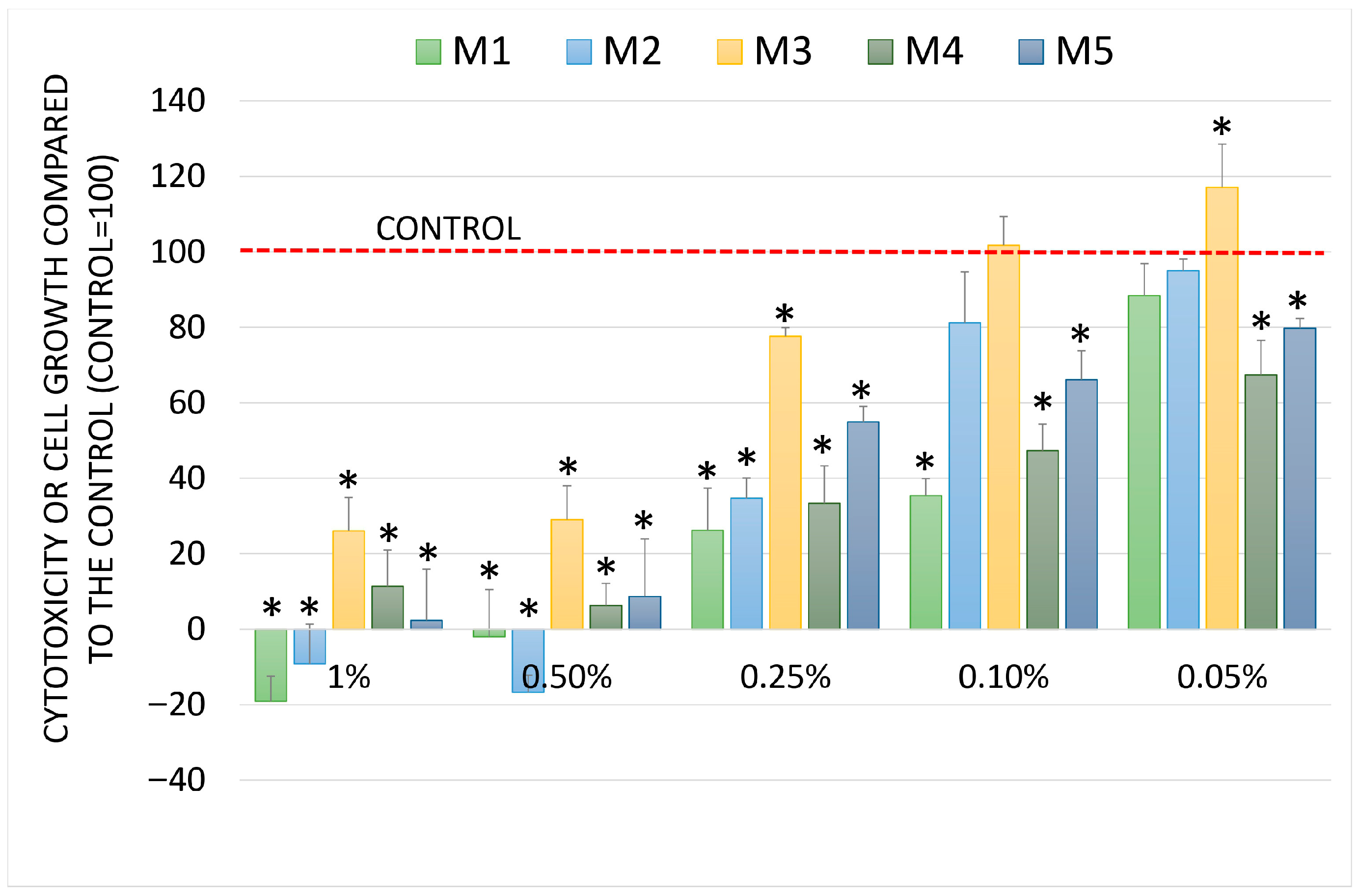

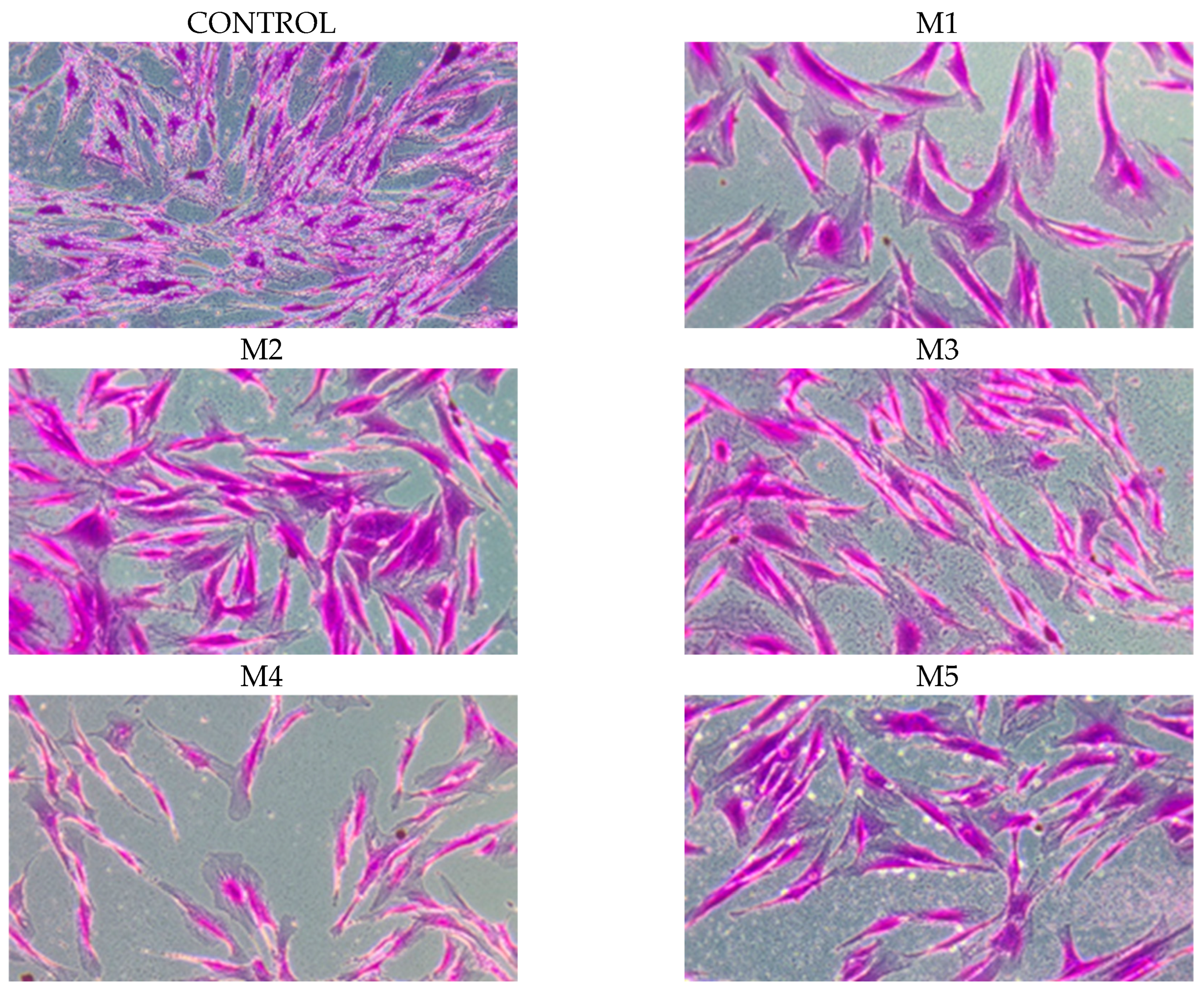

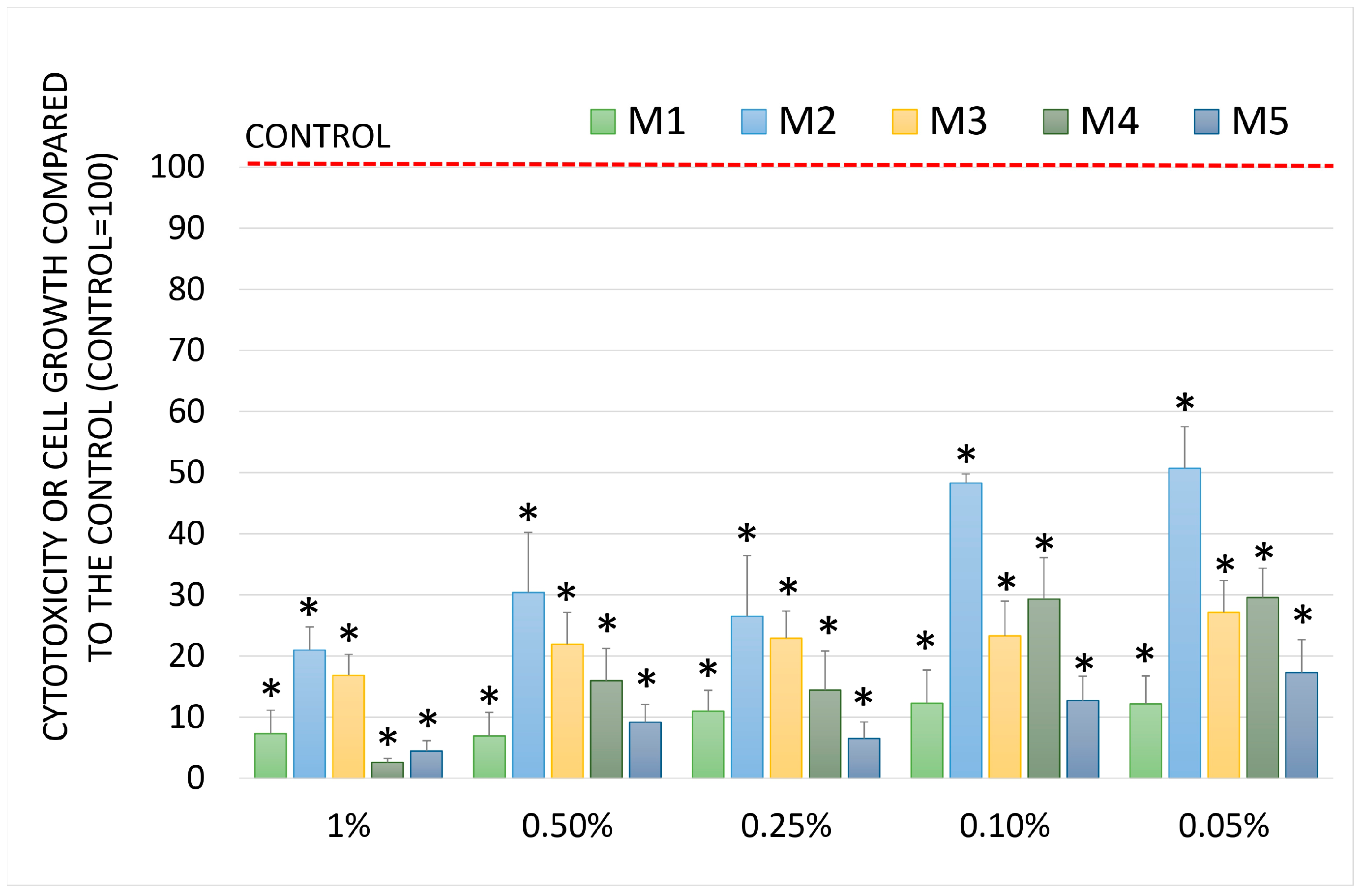

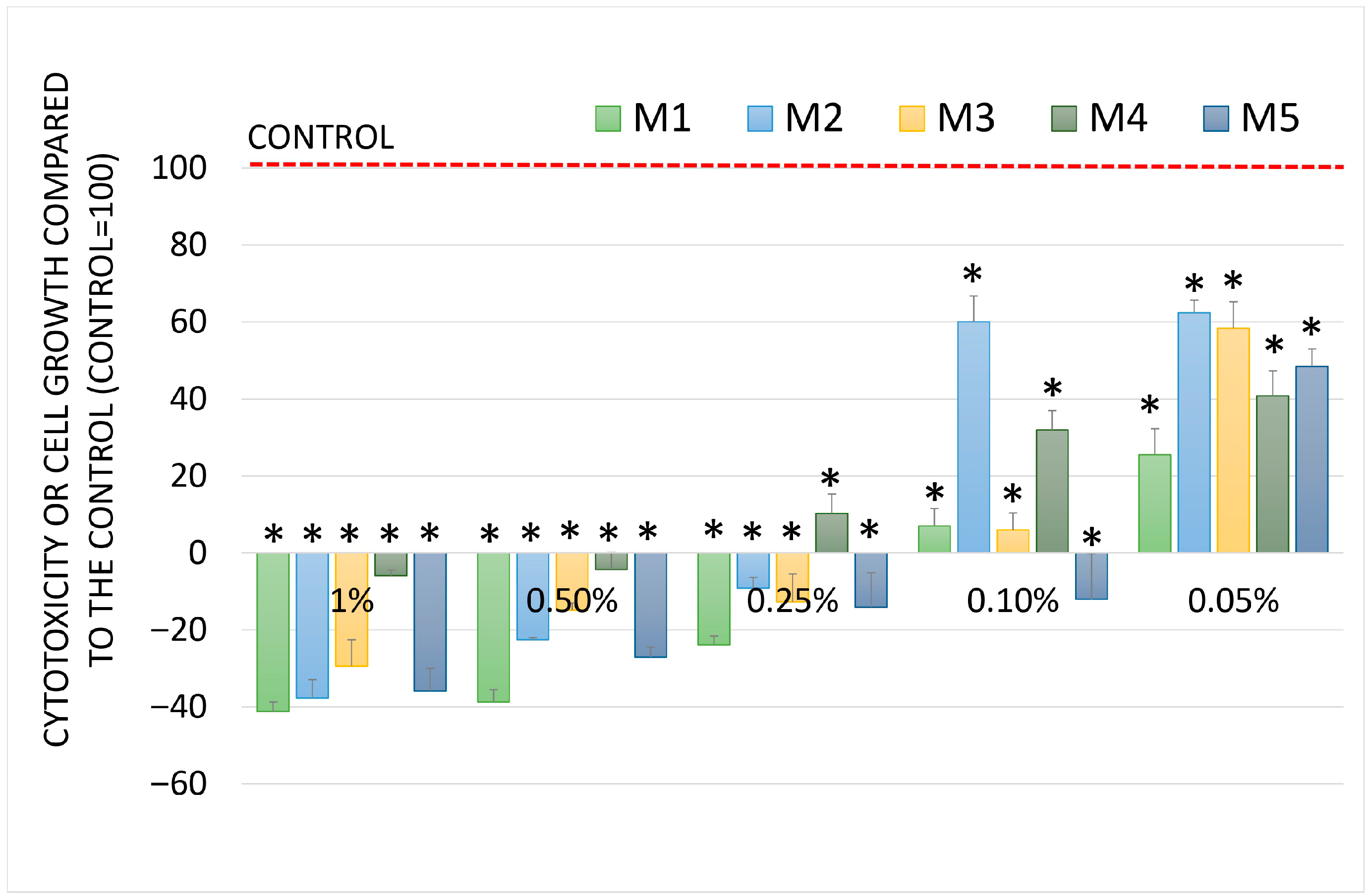

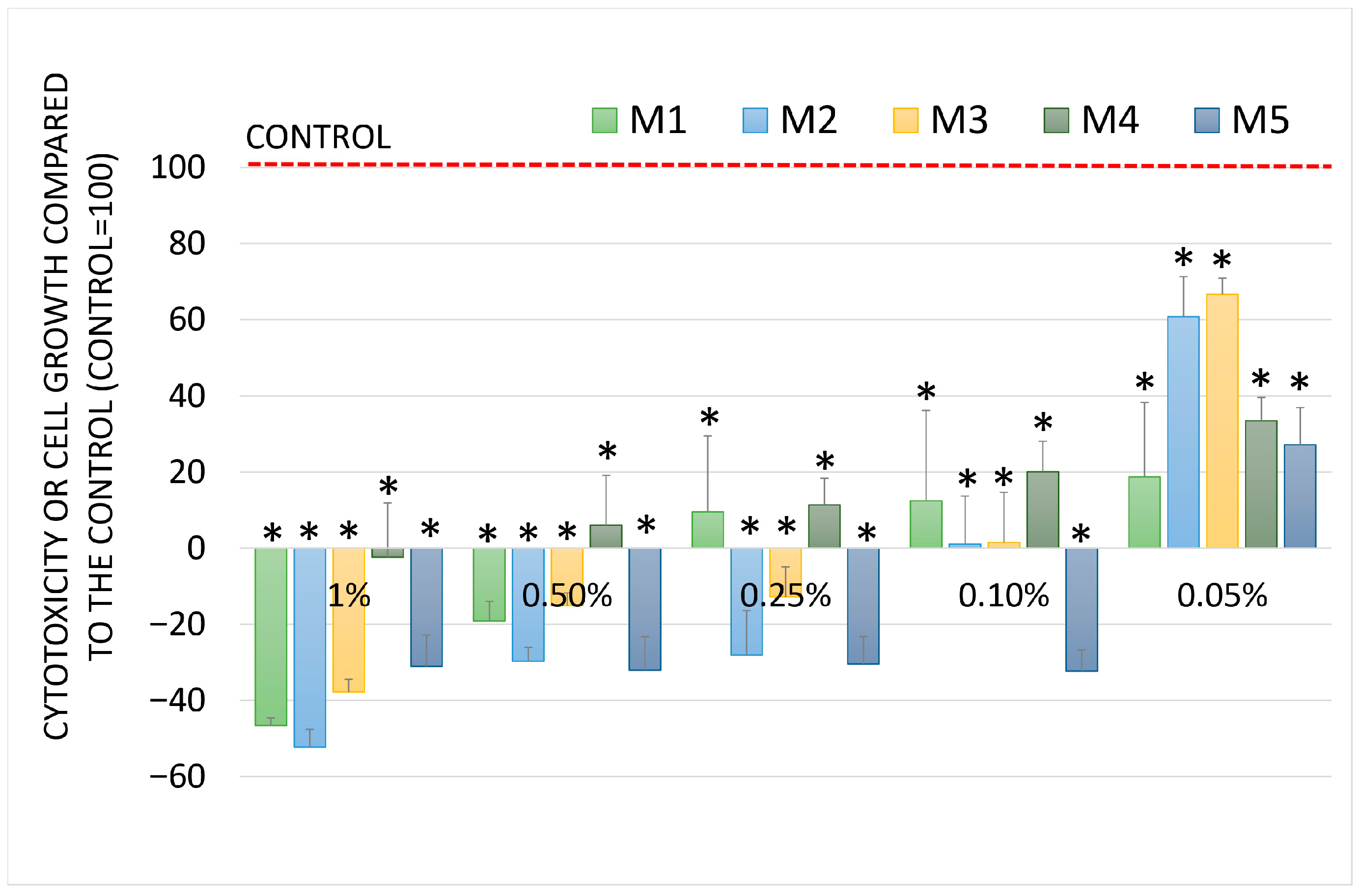

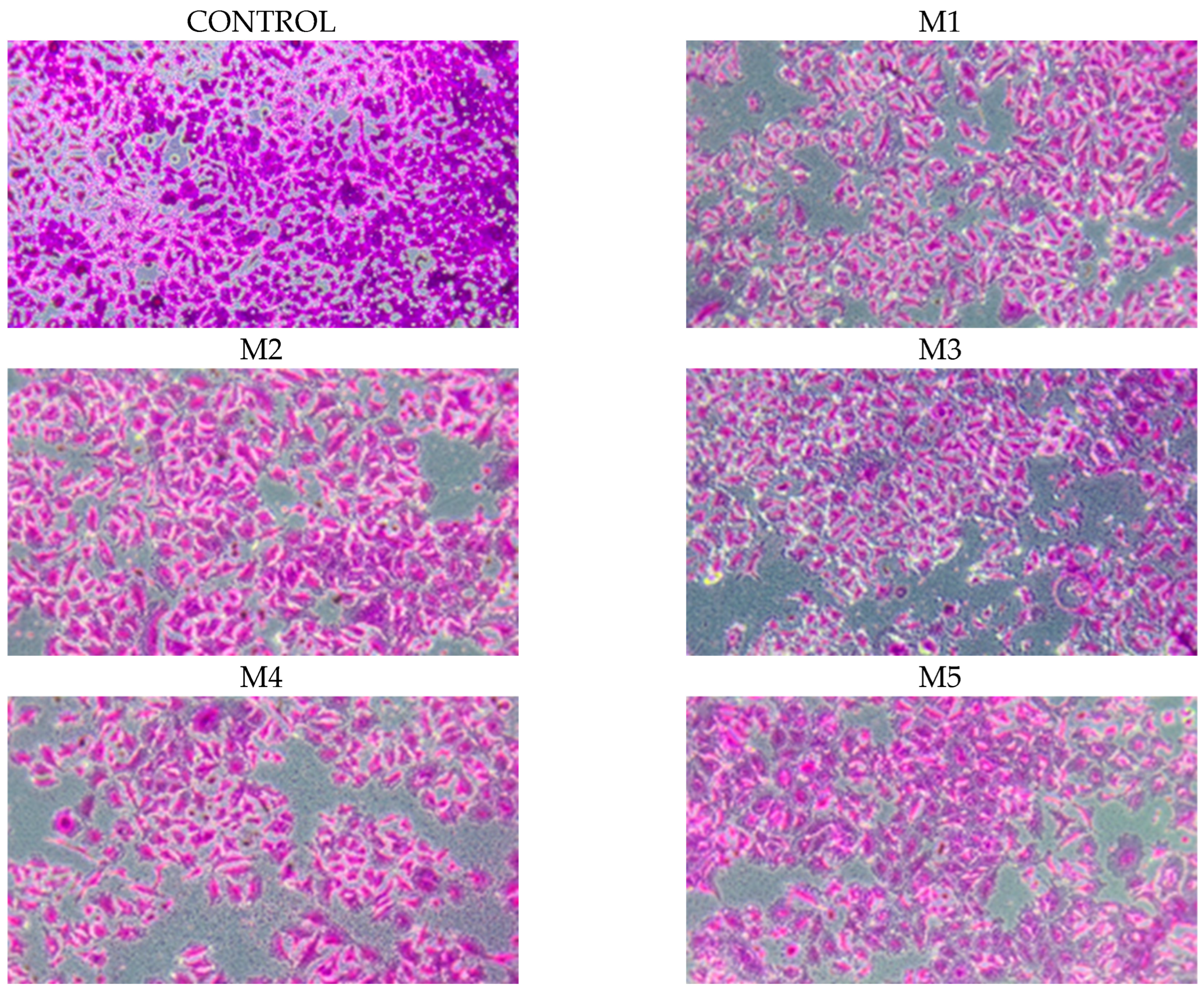

2.5. Chemopreventive Activity

2.6. Acute Oral Toxicity

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Preparation of Mixtures

4.3. GC-MS Analyses

4.4. Antibacterial Activity of EOs

4.4.1. Microbial Strains

4.4.2. Aromatogram Technique (Vincent Method)

4.4.3. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

4.4.4. Determination of Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

4.5. VirucidalActivity

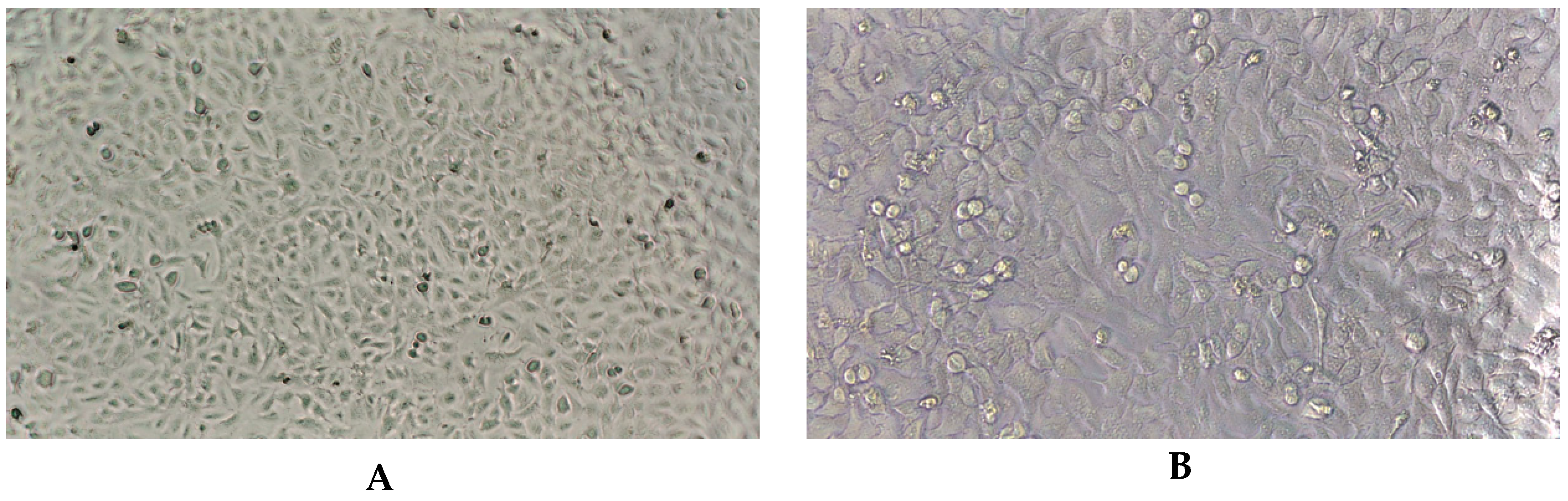

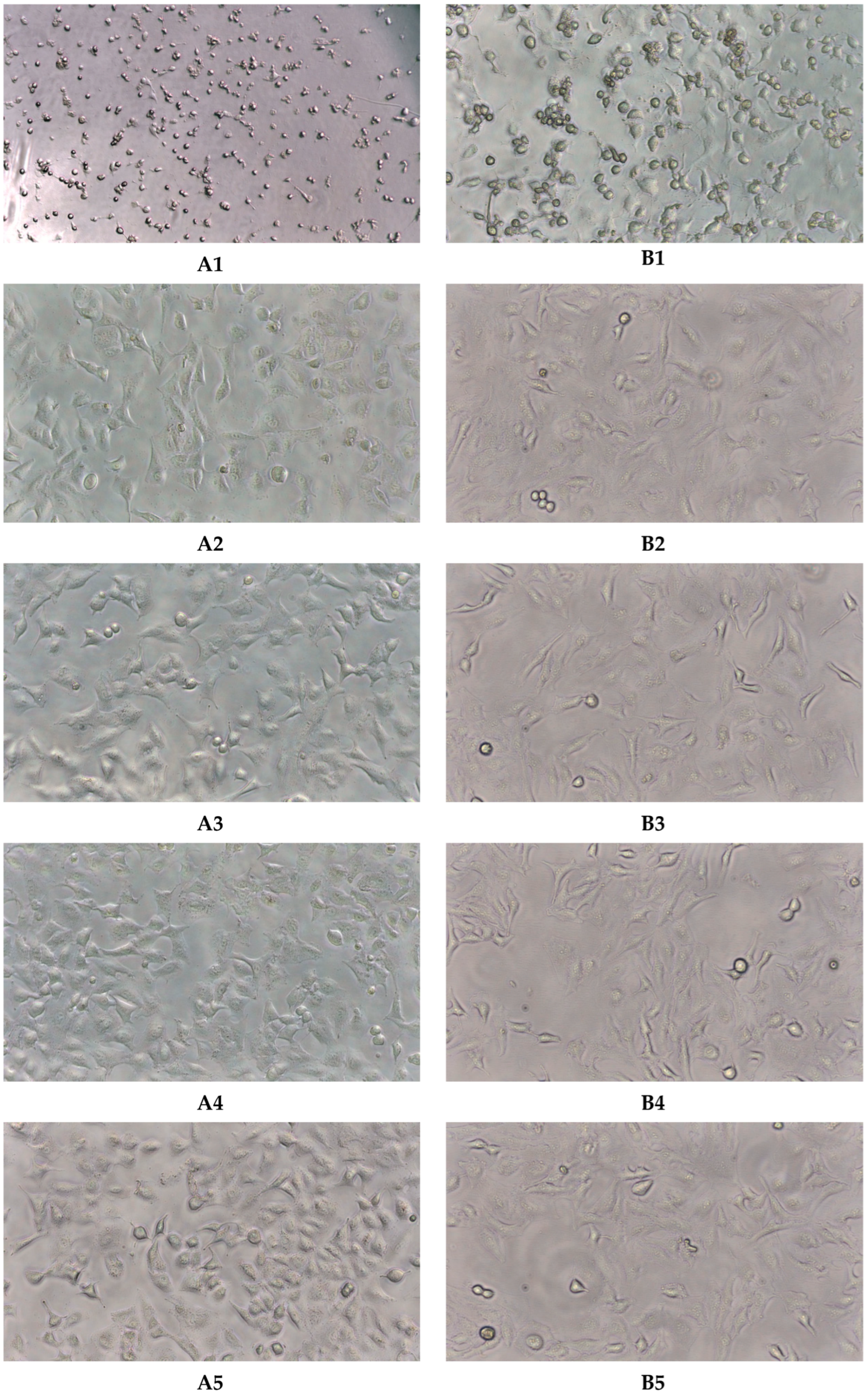

4.5.1. Cell Lines and Media

4.5.2. Virucidal Testing

4.6. Antioxidant Activity

4.7. Chemopreventive Activity

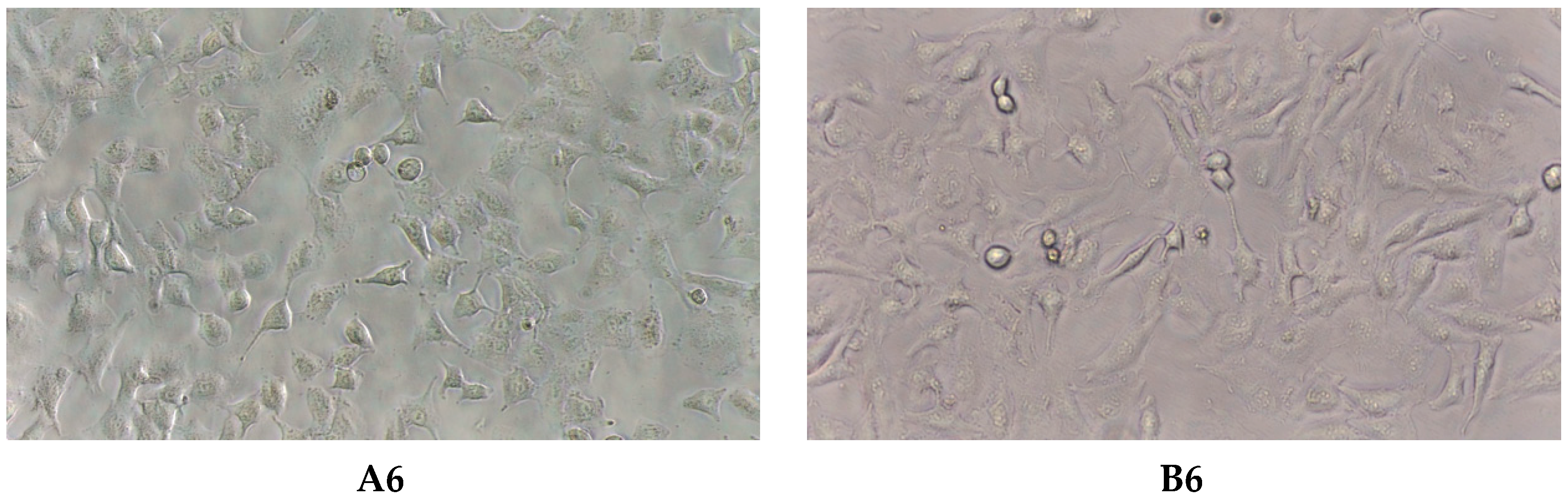

4.7.1. In Vitro Cell Culture

4.7.2. Evaluation of Cell Growth and Cytostatic Activity

4.8. Pharmacological Tests

4.8.1. Animals

4.8.2. Preparation of Test Samples

4.8.3. Acute Oral Toxicity

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LTv | Leaves of Thymus vulgaris |

| LAv | Leaves of Ammi visnaga |

| LMp | Leaves of Mentha pulegium |

| LLa | Leaves of Lavandulaangustifolia |

| PCs | orange peel Citrus sinensis |

| RZo | Roots of Zingiber officinale |

| BCv | Bark of Cinnamomum verum |

| CSa | Clove: Syzygium aromaticum |

| M1–M5 | Mixtures |

References

- Aye, M.M.; Aung, H.T.; Sein, M.M.; Armijos, C. A review on the phytochemistry, medicinal properties and pharmacological activities of 15 selected Myanmar medicinal plants. Molecules 2019, 24, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysargyris, A.; Petrovic, J.D.; Tomou, E.M.; Kyriakou, K.; Xylia, P.; Kotsoni, A.; Gkretsi, V.; Miltiadous, P.; Skaltsa, H.; Sokovi’c, M.D. Phytochemical Profiles and Biological Activities of Plant Extracts from Aromatic Plants Cultivated in Cyprus. Biology 2024, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algammal, A.; Hetta, H.F.; Mabrok, M.; Behzadi, P. Editorial: Emerging multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens “superbugs”: A rising public health threat. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meroni, G.; Laterza, G.; Tsikopoulos, A.; Tsikopoulos, K.; Vitalini, S.; Scaglia, B.; Iriti, M.; Bonizzi, L.; Martino, P.A.; Soggiu, A. Antibacterial Potential of Essential Oils and Silver Nanoparticles against Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius Isolates. Pathogens 2024, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saifulazmi, N.F.; Rohani, E.R.; Harun, S.; Bunawan, H.; Hamezah, H.S.; Nor Muhammad, N.A.; Azizan, K.A.; Ahmed, Q.U.; Fakurazi, S.; Mediani, A.; et al. A Review with Updated Perspectives on the Antiviral Potentials of Traditional Medicinal Plants and Their Prospects in Antiviral Therapy. Life 2022, 12, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atampugbire, G.; Adomako, E.E.A.; Quaye, O. Medicinal Plants as Effective Antiviral Agents and Their Potential Benefits. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2024, 19, 1934578X241282923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, A.; Iacopetta, D.; Ceramella, J.; Scumaci, D.; Giuzio, F.; Saturnino, C.; Aquaro, S.; Rosano, C.; Sinicropi, M.S. Multidrug Resistance (MDR): A Widespread Phenomenon in Pharmacological Therapies. Molecules 2022, 27, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). The Evolving Threat of Antimicrobial Resistance; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Herpes Simplex Virus; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/herpes-simplex-virus (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Roberts, C.K.; Sindhu, K.K. Oxidative stress and metabolic syndrome. Life Sci. 2009, 84, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, M.J. Pharmacologie Médicale, 8th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Esazadeh, K.; Ezzati, N.D.J.; Andishmand, H.; Mohammadzadeh-Aghdash, H.; Mahmoudpour, M.; NaemiKermanshahi, M.; Roosta, Y. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of tert-butylhydroquinone, butylated hydroxyanisole and propyl gallate as synthetic food antioxidants. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 7004–7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Noohi, N.; Inavolu, S.S.; Sujata, M. Plantderived natural products for drug discovery: Current approaches and prospects. Nucleus 2022, 65, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, L.; Bu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Meng, X. Exploring the Mechanisms of the Antioxidants BHA, BHT, and TBHQ in Hepatotoxicity, Nephrotoxicity, and Neurotoxicity from the Perspective of Network Toxicology. Foods 2025, 14, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pammi, S.S.S.; Suresh, B.; Giri, A. Antioxidant potential of medicinal plants. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 26, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, P.; Mininni, M.; Deiana, G.; Marino, G.; Divella, R.; Bochicchio, I.; Giuliano, A.; Lapadula, S.; Lettini, A.R.; Sanseverino, F. Healthy Lifestyle and Cancer Risk: Modifiable Risk Factors to Prevent Cancer. Nutrients 2024, 16, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Malhotra, A.; Ranju Bansal, R. Chapter 15—Synthetic cytotoxic drugs as cancer chemotherapeutic agents. In Medicinal Chemistry of Chemotherapeutic Agents; Acharya, P.C., Kurosu, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 499–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny, M.V. Selective protection of normal cells from chemotherapy, while killing drug-resistant cancer cells. Oncotarget 2023, 14, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Caballero-Gallardo, K.; Quintero-Rincón, P.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Aromatherapy and Essential Oils: Holistic Strategies in Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Integral Wellbeing. Plants 2025, 14, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Elmaidomy, A.H. Exploring the therapeutic potential of essential oils: A review of composition and influencing factors. Front. Nat. Prod. 2025, 4, 1490511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Biswas, S.; Satyaprakash, K. Exploring the synergistic effects of plant powders and essential oil combination on the quality, and structural integrity of chicken sausages during storage. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benamar-Aissa, B.; Gourine, N.; Ouinten, M.; Yousfi, M. Synergistic effects of essential oils and phenolic extracts on antimicrobial activities using blends of Artemisia campestris, Artemisia herba alba, and Citrus aurantium. Biomol. Concepts 2024, 15, 20220040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hushang, A. EBN AL-BAYṬĀR, ŻĪĀʾ-AL-DĪN ABŪ MOḤAMMAD ʿABD-ALLĀH. In Encyclopaedia Iranica; Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume VIII, pp. 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Vernet, J. Ibn Al-Bayṭār Al-Mālaqī, ḌiyāʾAl-Dīn AbūMuḥammadʿAbdllāh Ibn Aḥmad. In Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography; Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 1970–1980. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, B.; Said, O. “3.3”. Greco-Arab and Islamic Herbal Medicine; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2011; ASIN B005526C6O. [Google Scholar]

- Galovičová, L.; Borotová, P.; Valková, V.; Vukovic, N.L.; Vukic, M.; Štefániková, J.; Ďúranová, H.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Čmiková, N.; Kačániová, M. Thymus vulgaris Essential Oil and Its Biological Activity. Plants 2021, 10, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndayambaje, M.; Wahnou, H.; Sow, M.; Chgari, O.; Habyarimana, T.; Karkouri, M.; Limami, Y.; Naya, A.; Oudghiri, M. Exploring the multifaceted effects of Ammi visnaga: Subchronic toxicity, antioxidant capacity, immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory activities. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2024, 87, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chraibi, M.; Mouhcine Fadil, M.; Farah, A.; Lebrazi, S.; Fikri-Benbrahim, K. Antimicrobial combined action of Mentha pulegium, Ormenis mixta and Mentha piperita essential oils against S. aureus, E. coli and C. tropicalis: Application of mixture design methodology. LWT 2021, 145, 111352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, C.; Abidet, N.E.; Djebaili, R.; Guira, Z. Enquête Ethnobotanique, Caractérisation Pharmacognosique et Exploration des Potentialités Biologiques des Huiles Essentielles de Rosmarinus Officinalis et Lavandula Anguestifolia. Master’s Thesis, Université Constantine, Constantine, Algeria, 2024; p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- Mbaveng, A.; Kuete, V. Zingiber officinale. In Medicinal Spices and Vegetables from Africa; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 627–639. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, R.; Sharma, H.A. Review on Medicinal Uses of Cinnamomum verum (Cinnamon). J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2021, 11, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, M.; Gupta, N.; Parashar, P.; Mehra, V.; Khatri, M. Phytochemical evaluation and pharmacological activity of Syzygium aromaticum: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bahramikia, S.; Habibi, S.; Shirzadi, N. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activities of methanol extract and essential oil of two varieties of Citrus sinensis L. in Iran. Nat. Product. Res. 2024, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, M.P.; Messing, A.M. Methods for comparing the antibacterial activity of essential oils and other aqueous insoluble compounds. Bull. Nat. Formul. Comm. 1949, 17, 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Marmonier, A.A. Introduction aux techniques d’étude des antibiotiques. In Bactériologie Médicale, Techniques Usuelles; DOIN Edition: Paris, France, 1990; pp. 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Włoch, A.; Kapusta, I.; Bielecki, K.; Oszmiański, J.; Kleszczyńska, H. Activity of hawthorn leaf and bark extracts in relation to biological membrane. J. Membr. Biol. 2013, 246, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włoch, A.; Strugała, P.; Pruchnik, H.; Żyłka, R.; Oszmiański, J.; Kleszczyńska, H. Physical Effects of Buckwheat Extract on Biological Membrane In Vitro and Its Protective Properties. J. Membr. Biol. 2016, 249, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, M.; ZainalAbidin, Z.; Yoshida, H.; Yunus, R.; Awang, B.D.R. Towards Higher Oil Yield and Quality of Essential Oil Extracted from Aquilariamalaccensis Wood via the Subcritical Technique. Molecules 2020, 25, 3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sisto, F.; Carradori, S.; Guglielmi, P.; Traversi, C.B.; Spano, M.; Sobolev, A.P.; Secci, D.; Di Marcantonio, M.C.; Haloci, E.; Grande, R. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Carvacrol-Based Derivatives as Dual Inhibitors of H. pylori Strains and AGS Cell Proliferation. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhou, F.; Ji, B.P.; Pei, R.S.; Xu, N. The antibacterial mechanism of carvacrol and Thymol against Escherichia coli. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 47, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Jeyakumar, E.; Lawrence, R. Journey of Limonene as an Antimicrobial Agent. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 15, 1094–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Marshall, M.R.; Cornell, J.A.; Preston, J.F.; Wei, C.I. Antibacterial Activity of Carvacrol, Citral, and Geraniol against Salmonella typhimurium in Culture Medium and on Fish Cubes. Food Sci. 1995, 60, 1364–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, A.A.; Krämer, T.; Kavanagh, K.; Stephens, J.C. Cinnamaldehydes: Synthesis, antibacterial evaluation, and the effect of molecular structure on antibacterial activity. Results Chem. 2019, 1, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; He, L.; Zhao, Z.; Mao, X.; Zhang, C. The specific effect of (R)-(+)-pulegone on growth and biofilm formation in multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli and molecular mechanisms underlying the expression of pgaABCD genes. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 134, 111149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, A.; Barbieri, R.; Coppo, E.; Orhan, I.E.; Daglia, M.; Nabavi, S.F.; Izadi, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Nabavi, S.M.; Ajami, M. Antimicrobial activity of eugenol and essential oils containing eugenol: A mechanistic viewpoint. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 43, 668–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboubi, M. Zingiber officinale Rosc. essential oil, a review on its composition and bioactivity. Clin. Phytosci. 2019, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahham, S.S.; Tabana, Y.M.; Iqbal, M.A.; Ahamed, M.B.K.; Ezzat, M.O.; Majid, A.S.A.; Majid, A.M.S.A. The Anticancer, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of the Sesquiterpene β-Caryophyllene from the Essential Oil of Aquilaria crassna. Molecules 2015, 20, 11808–11829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanishlieva, N.V.; Marinova, E.M.; Gordon, M.H.; Raneva, V.G. Antioxidant activity and mechanism of action of thymol and carvacrol in two lipid systems. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beena; Kumar, D.; Rawat, D.S. Synthesis and antioxidant activity of thymol and carvacrol based Schiff bases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarjono, P.R.; Putri, L.D.; Budiarti, C.E.; Mulyani, N.S.; Ngadiwiyana; Ismiyarto; Kusrini, D.; Prasetya, N.B.A. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of secondary metabolite endophytic bacteria from papaya leaf (Carica papaya L.). IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 509, 012112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.N.; Muralidhara, M. Analysis of the antioxidant activity of geraniol employing various in-vitro models: Relevance to neurodegeneration in diabetic neuropathy. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2017, 10, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondrak, G.T.; Villeneuve, N.F.; Lamore, S.D.; Bause, A.S.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, D.D. The Cinnamon-Derived Dietary Factor Cinnamic Aldehyde Activates the Nrf2-Dependent Antioxidant Response in Human Epithelial Colon Cells. Molecules 2010, 15, 3338–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghorab, A.H. The Chemical Composition of the Mentha pulegium L. Essential Oil from Egypt and its Antioxidant Activity. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2006, 9, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabuto, H.; Tada, M.; Kohno, M. Eugenol [2-Methoxy-4-(2-propenyl) phenol] Prevents 6-HydroxydopamineInduced Dopamine Depression and Lipid Peroxidation Inductivity in Mouse Striatum. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höferl, M.; Stoilova, I.; Wanner, J.; Schmidt, E.; Jirovetza, L.; Trifonovab, D.; Stanchevd, V.; Krastanov, A. Composition and Comprehensive Antioxidant Activity of Ginger (Zingiber officinale) Essential Oil from Ecuador. Nat. Product. Commun. 2015, 10, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilling, D.H.; Kitajima, M.; Torrey, J.R.; Bright, K.R. Antiviral efficacy and mechanisms of action of oregano essential oil and its primary component carvacrol against murine norovirus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 116, 1149–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandi, T.; Khanna, M. Anti-Viral Activity of Thymol against Influenza A Virus. EC Microbiol. 2022, 18, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, A.; Przychodna, M.; Sopata, S.; Bodalska, A.; Fecka, I. Thymol and Thyme Essential Oil-New Insights into Selected Therapeutic Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxeberria, I.; Garcia, J.; Ibáñez, A.; García-Moyano, A.; Paniagua-García, A.I.; Díaz, Y.; Díez-Antolínez, R.; Barrio, A. Antimicrobial Activity of Lignin-Based Alkyd Coatings Containing Soft Hop Resins and Thymol. Coatings 2025, 15, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, L.A.; Stashenko, E.; Ocazionez, R.E. Comparative Study on In Vitro Activities of Citral, Limonene and Essential Oils from Lippia citriodora and L. alba on Yellow Fever Virus. Nat. Product. Commun. 2013, 8, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheraghali, Z.; Mohammadi, R.; Jalilzadeh-Amin, G. Planimetric and Biomechanical Study of Local Effect of Pulegone on Full Thickness Wound Healing in Rat. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 24, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benencia, F.; Courrèges, M.C. In vitro and in vivo activity of eugenol on human herpesvirus. Phytother. Res. 2000, 14, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, V.K.; Kumar, S.; Maurya, S.; Ansari, S.; Paweska, J.T.; Abdel-Moneim, A.S.; Saxena, S.K. Structure-based drug designing for potential antiviral activity of selected natural products from Ayurveda against SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and its cellular receptor. Virus Dis. 2020, 31, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrinho, A.C.N.; de Morais, S.M.; Marinho, M.M.; de Souza, N.V.; Lima, D.M. Antiviral activity on the Zika virus and larvicidal activity on the Aedes spp. of Lippia alba essential oil and β-caryophyllene. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 162, 113281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Sharma, N.R. Emerging Anticancer Metabolite, Carvacrol, and its Action Mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India—Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2024, 94, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Khalipha, A.B.R.; Bagchi, R.; Mondal, M.; Smrity, S.Z.; Uddin, S.J.; Shilpi, J.A.; Rouf, R. Anticancer activity of thymol: A literature-based review and docking study with Emphasis on its anticancer mechanisms. IUBMB Life 2019, 71, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo-Filho, H.G.; Dos Santos, J.F.; Carvalho, M.T.B.; Picot, L.; Fruitier-Arnaudin, I.; Groult, H.; Quintans-Júnior, L.J.; Quintans, J.S.S. Anticancer activity of limonene: A systematic review of target signaling pathways. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 4957–4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, G.; Mukherjee, E.; Mittal, R.; Ganjewala, D. Geraniol and citral: Recent developments in their anticancer credentials opening new vistas in complementary cancer therapy. Z. Naturforschung C 2024, 79, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Song, X.; Yu, W.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jian, H.; He, B. The role and mechanism of cinnamaldehyde in cancer. J. Food Drug Anal. 2024, 32, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amtaghri, S.; Slaoui, M.; Eddouks, M. Mentha Pulegium: A Plant with Several Medicinal Properties. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2024, 24, 302–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issa, H.; Loubaki, L.; Al Amri, A.; Zibara, K.; Almutairi, M.H.; Rouabhia, M.; Semlali, A. Eugenol as a potential adjuvant therapy for gingival squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, M.M.; Upadhyay, T.K.; Upadhye, V.; Sharangi, A.B.; Saeed, M. Phytocompound identification of aqueous Zingiber officinale rhizome (ZOME) extract reveals antiproliferative and reactive oxygen species mediated apoptotic induction within cervical cancer cells: An in vitro and in silico approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 42, 8733–8760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, E.A. The Potential Therapeutic Role of Beta-Caryophyllene as a Chemosensitizer and an Inhibitor of Angiogenesis in Cancer. Molecules 2025, 30, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amraoui, A.; Bahri, F.; Wanner, J. Chemical composition, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activity of Algerian Ammi visnaga essential oil. Plant Arch. 2022, 22, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flechas, M.C.; Ocazionez, R.E.; Stashenko, E.E. Evaluation of in vitro Antiviral Activity of Essential Oil Compounds Against Dengue Virus. Pharmacogn. J. 2018, 10, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadisa, E.; Weldearegay, G.; Desta, K.; Tsegaye, G.; Hailu, S.; Jote, K.; Takele, A. Combined antibacterial effect of essential oils from three most commonly used Ethiopian traditional medicinal plants on multidrug resistant bacteria. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahdani, M.; Faridi, P.; Zarshenas, M.M.; Javadpour, S.; Abolhassanzadeh, Z.; Moradi, N.; Bakzadeh, Z.; Karmostaji, A.; Mohagheghzadeh, A.; Ghasemi, Y. Major Compounds and Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oils from Five Iranian Endemic Medicinal Plants. Pharmacogn. J. 2011, 3, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.J.; Beserra, F.P.; Souza, M.C.; Totti, B.M.; Rozza, A.L. Limonene: Aroma of innovation in health and disease. Chemico-Biol. Interact. 2018, 283, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Guleriaa, S.; Razdanb, V.K.; Babu, V. Synergistic antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of essential oils of some selected medicinal plants in combination and with synthetic compounds. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 154, 112569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, S.; Brandt, W.; Porzel, A.; Athmer, B.; Bennewitz, S.; Schäfer, P.; Kortbeek, R.; Bleeker, P.; Tissier, A. A single cytochrome P450 oxidase from Solanumhabrochaites sequentially oxidizes 7-epi-zingiberene to derivatives toxic to whiteflies and various microorganisms. Plant J. 2021, 105, 1309–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, G.S.; Marques, J.N.J.; Linhares, E.P.M.; Bonora, C.M.; Costa, E.T.; Saraiva, M.F. Review of anticancer activity of monoterpenoids: Geraniol, nerol, geranial and neral. Chemico-Biol. Interact. 2022, 362, 109994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruckmann, F.; Viana, A.; Lopes, L.Q.S.; Santos, R.C.V.; Muller, E.I.; Mortari, S.R.; Rhoden, C.R.B. Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Activity Evaluation of Magnetite-Functionalized Eugenol. J. Inorg. Organom. Polym. 2022, 32, 1459–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibi1, A.A.; Kyuka, C.K. Sources, extraction and biological activities of cinnamaldehyde. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2022, 8, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepetkin, I.A.; Özek, G.; Özek, T.; Kirpotina, L.N.; Klein, R.A.; Khlebnikov, A.I.; Quinn, M.T. Composition and Biological Activity of the Essential Oils from Wild Horsemint, Yarrow, and Yampah from Subalpine Meadows in Southwestern Montana: Immunomodulatory Activity of Dillapiole. Plants 2023, 12, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, T.; Qureshi, H.; Fatima, A.; Sattar, K.; Albasher, G.; Kamal, A.; Ayaz, A.; Zaman, W. Citrus Sinensis Peel oil extraction and evaluation as an antibacterial and antifungal agent. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nostro, A.; Papalia, T. Antimicrobial activity of carvacrol: Current progress and future prospectives. Recent. Pat. Antiinfect. Drug Discov. 2012, 7, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachur, K.; Suntres, Z. The antibacterial properties of phenolic isomers, carvacrol and thymol. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 60, 3042–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelli, W.; Sysak, A.; Bahri, F.; Szumny, A.; Pawlak, A.; Obmińska-Mrukowicz, B. Chemical Composition, Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activity of Essential Oils of Algerian Thymus vulgaris L. Acta Pol. Pharm. Drug Res. 2019, 76, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Xing, Z.; Su, R.; Wang, Y.; Xia, X.; Shi, C. Antibacterial Effect of Eugenol on Shigella flexneri and Its Mechanism. Foods 2022, 11, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Chen, W.; Sun, Z. Antimicrobial activity and mechanism of limonene against Staphylococcus aureus. J. Food Saf. 2021, 41, e12918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaki, M.; Nara, T.; Sakaiya, S.; Yamanouchi, K.; Tsujiguchi, T.; Chounan, Y. Biotransformation of citronellal, geranial, citral and their analogs by fungus and their antimicrobial activity. Trans. Mat. Res. Soc. Japan 2018, 43, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.; Tang, Z.; Han, W.; Chen, H.; Chen, W.; Hu, Y.; Chen, W. Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of Caryophyllene against Brochothrix thermosphacta. Food Sci. 2020, 41, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Dey, S.; Sahoo, R.K.; Sahoo, S.; Subudhi, E. Antibiofilm and Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oil Bearing Zingiber officinale Rosc. (Ginger) Rhizome Against Multi-drug Resistant Isolates. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2019, 22, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalich, S.; Fadili, K.; Fahim, M.; EL Hilali, F.; Zaïr, T. Polyphenols content and antioxidant power of fruits and leaves of Juniperus phoenicea L. from Tounfite (Morocco). Mor. J. Chem. 2016, 4, 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Lengyel, E.; Panaitescu, M. Chemical Compounds from Thymus vulgaris and their Antimicrobial Activity, Management of Sustainable Development. Sciendo 2019, 11, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.Q.; Liu, X.X.; Wang, X.Y.; Xie, Y.H.; Yang, Q.; Liu, X.X.; Ding, Y.Y.; Cao, W.; Wang, S.W. Cinnamaldehyde Derivatives Inhibit Coxsackievirus B3-Induced Viral Myocarditis. Biomol. Ther. 2017, 25, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryati; Dachriyanus; Irwandi, J.; Faridah, Y. Chemical Profiling and Antibacterial Activity of Javanese Turmeric (Curcuma xanthorriza) Essential Oil on Selected Wound Pathogen. Adv. Health Sci. Res. 2021, 40, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhahli, A.S.; Al-Hassani, F.A.; Mohammed Alarjani, K.; Yehia, H.M.; Al Lawati, W.M.; Azmi, S.N.H.; Shah Alam Khan, S.K. Essential oil from the rhizomes of the Saudi and Chinese Zingiber officinale cultivars: Comparison of chemical composition, antibacterial and molecular docking studies. J. King Saud. Univ.-Sci. 2020, 32, 3343–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cai, J.; Chen, H.; Zhong, Q.; Hou, Y.; Chen, W.; Chen, W. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of linalool against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 141, 103980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Yang, C.; Zhang, N.; Peng, Y.; Ma, Y.; Gu, K.; Zhao, L. Menthone Exerts its Antimicrobial Activity Against Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus by Affecting Cell Membrane Properties and Lipid Profile. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2023, 17, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, R.; Yang, S.; Fu, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, M.; Qi, Y.; Xu, N.; Wu, Q.; Hua, Q.; Wu, Y.; et al. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of the sesquiterpeneδ-cadinene against Listeria monocytogenes. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 203, 116388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Farhana, K.A.; Warada, I.; Al-Resayes, S.I.; Foudab, M.M.; Ghazzalia, M. Synthesis, structural chemistry and antimicrobial activity of -(-) borneol derivative. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 2010, 8, 1127–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zheng, H.; Yang, S.; Qi, Y.; Li, W.; Kang, S.; Hu, H.; Hua, Q.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Z. Antimicrobial activity and mechanism of α-copaene against foodborne pathogenic bacteria and its application in beef soup. LWT 2024, 195, 115848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S. Essential oils: Their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods—A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miladi, H.; Zmantar, T.; Kouidhi, B.; Al Qurashi, Y.M.A.; Bakhrouf, A.; Chaabouni, Y.; Mahdouani, K.; Chaieb, K. Synergistic effect of eugenol, carvacrol, thymol, p-cymene and γ-terpinene on inhibition of drug resistance and biofilm formation of oral bacteria. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 112, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiki, L.M.; Barbieri, A.M.E.; Araujo, R.C.; Ferreira, J.F.S. Synergistic interaction of ten essential oils against Haemonchus contortus in vitro. Vet. Parasitol. 2017, 243, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Atki, Y.; Aouam, I.; El Kamari, F.; Taroq, A.; Nayme, K.; Timinouni, M.; Lyoussi, B.; Abdellaoui, A. Antibacterial activity of cinnamon essential oils and their synergistic potential with antibiotics. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2019, 10, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, B.; Zhang, Q.; Ge, J. Human neutralizing antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature 2020, 584, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Beuchat, L.R.; Ryu, J.H. Synergistic antimicrobial activities of plant essential oils against Listeria monocytogenes in organic tomato juice. Food Control 2021, 125, 108000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Ye, X.; Li, X.; Kai, H. Synergy effects of herb extracts: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic basis. Fitoterapia 2014, 92, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaelli, M.; da Silva, B.P.; Weidlich, L.; Hoehne, L.; Flach, A.; da Costa, L.; Ethur, E.M. Antimicrobial activities of six essential oils commonly used as condiments in Brazil against Clostridium perfringens. J. Microbiol. 2016, 47, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faleiro, M.L. The Mode of Antibacterial Action of Essential Oils. In Science against Microbial Pathogens: Communicating Current Research and Technological Advances; Mendez-Vilas, A., Ed.; Formatex Research Center: Badajoz, Spain, 2011; pp. 1143–1156. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233920172 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Jeyakumar, G.E.; Lawrence, R. Mechanisms of bactericidal action of Eugenol against Escherichia coli. J. Herbal. Med. 2021, 26, 100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, A.S.Y.; Maran, S.; Yap, P.S.X.; Lim, S.H.E.; Yang, S.K.; Cheng, W.H.; Tan, Y.H.; Lai, K.S. Anti- and Pro-Oxidant Properties of Essential Oils against Antimicrobial Resistance. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Lv, B.; Zhang, C.; Shi, L.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Q. Antibacterial activity of the biogenic volatile organic compounds from three species of bamboo. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1474401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Li, B.; Lv, Y.; Wei, S.; Zhang, S.; Hu, Y. Synergistic effects of combined cinnamaldehyde and nonanal vapors against Aspergillus flavus. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 402, 110277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Yang, G.; Huang, S.; Li, B.; Li, A.; Kan, J. Chemical composition of Zanthoxylum schinifolium Siebold & Zucc. essential oil and evaluation of its antifungal activity and potential modes of action on Malassezia restricta. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 180, 114698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasena, M.T.; Rafi, A.; MohdZobir, S.A.; Hussein, M.Z.; Ali, A.; Kutawa, A.B.; Abdul Wahab, M.A.; Sulaiman, M.R.; Adzmi, F.; Ahmad, K. Phytochemicals Profiling, Antimicrobial Activity and Mechanism of Action of Essential Oil Extracted from Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe cv. Bentong) against Burkholderia glumae Causative Agent of Bacterial Panicle Blight Disease of Rice. Plants 2022, 11, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shen, Y.; Thakur, K.; Han, J.; Zhang, J.G.; Hu, F.; Wei, Z.J. Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of Ginger Essential Oil against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Molecules 2020, 25, 3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akermi, S.; Smaoui, S.; Fourati, M.; Elhadef, K.; Chaari, M.; ChakchoukMtibaa, A.; Mellouli, L. In-Depth Study of Thymus vulgaris Essential Oil: Towards Understanding the Antibacterial Target Mechanism and Toxicological and Pharmacological Aspects. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 3368883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Z.; Ding, T.; Ye, X.; Liu, D.; Guo, M. Antibacterial mechanisms of thyme essential oil nanoemulsions against Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Staphylococcus aureus: Alterations in membrane compositions and characteristics. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 75, 102902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słońska, A.; Miedzińska, A.; Chodkowski, M.; Bąska, P.; Mielnikow, A.; Bartak, M.; Bańbura, M.W.; Cymerys, J. Human Adenovirus Entry and Early Events during Infection of Primary Murine Neurons: Immunofluorescence Studies In Vitro. Pathogens 2024, 13, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piret, J.; Boivin, G. Resistance of Herpes Simplex Viruses to Nucleoside Analogues: Mechanisms, Prevalence, and Management. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lurain, N.S.; Chou, S. Antiviral drug resistance of human cytomegalovirus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 689–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamalabadi, M.; Astani, A.; Nemati, F. Anti-viral Effect and Mechanism of Carvacrol on Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1. Int. J. Med. Lab. 2018, 5, 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Elshaarawy, F.S.; Abdelhady, M.I.S.; Hamdy, W.; Haitham, A.I. Investigation of the Essential Oil Constituents of Pimenta racemosa Aerial Parts and Evaluation of Its Antiviral Activity against Hsv 1 and 2. Trends Adv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichling, J. Antiviral and Virucidal Properties of Essential Oils and Isolated Compounds—A Scientific Approach. Planta Med. 2022, 88, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Sureda, A.; Tenore, G.C.; Daglia, M.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Valussi, M.; Tundis, R.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Loizzo, M.R.; Ademiluyi, A.O.; et al. Biological Activities of Essential Oils: From Plant Chemoecology to Traditional Healing Systems. Molecules 2017, 22, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astani, A.; Reichling, J.; Schnitzler, P. Screening for antiviral activities of isolated compounds from essential oils. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2011, 2011, 253643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Yuan, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, T.; Wang, B. Comparison of different methods for extraction of Cinnamomi ramulus: Yield, chemical composition and in vitro antiviral activities. Nat. Product. Res. 2017, 31, 2909–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firuj, A.; Aktar, F.; Akter, T.; Chowdhury, J.A.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Kabir, S.; Büyükerand, S.M.; Amran, M.d.S. Anti-viral Activity of 62 Medicinal Plants, Herbs and Spices Available in Bangladesh: A Mini Review. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 22, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, M.; Kita, M.; Nakaya, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Kuriyama, H.; Imanishi, J. The inhibitory effect of essential oils on herpes simplex virus type-1 replication in vitro. Microbiol. Immunol. 2003, 47, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, D.P.; Damasceno, R.O.S.; Amorati, R.; Elshabrawy, H.A.; de Castro, R.D.; Bezerra, D.P.; Nunes, V.R.V.; Gomes, R.C.; Lima, T.C. Essential Oils: Chemistry and Pharmacological Activities. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Astani, A.; Schnitzler, P. Antiviral activity of monoterpenes beta-pinene and limonene against herpes simplex virus in vitro. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2014, 3, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lai, W.L.; Chuang, H.S.; Lee, M.H.; Wei, C.L.; Lin, C.F.; Tsai, Y.C. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 by thymol-related monoterpenoids. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 1636–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, Y.M.; Roa-Linares, V.C.; Betancur-Galvis, L.A.; Durán-García, D.C.; Stashenko, E. Antiviral activity of Colombian labiatae and verbenaceae family essential oils and monoterpenes on human herpes viruses. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2016, 28, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagno, V.; Sgorbini, B.; Sanna, C.; Cagliero, C.; Ballero, M.; Civra, A.; Donalisio, M.; Bicchi, C.; Lembo, D.; Rubioloet, P. In vitro anti-herpes simplex virus-2 activity of Salvia desoleana Atzei & V. picci essential oil. PLoS ONE 2018, 12, e0172322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wałaszek, M.; Różańska, A.; Wałaszek, M.Z.; Wójkowska-Mach, J.; The Polish Society of Hospital Infections Team. Epidemiology of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia, microbiological diagnostics and the length of antimicrobial treatment in the Polish Intensive Care Units in the years 2013–2015. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnitzler, P. Essential oils for the treatment of herpes simplex virus infections. Chemotherapy 2019, 64, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, D.M.; Castillo, E.; Duarte, L.F.; Arriagada, J.; Corrales, N.; Farías, M.A.; Henríquez, A.; Agurto-Muñoz, C.; González, P.A. Current antivirals and novel botanical molecules interfering with herpes simplex virus infection. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, A.R.; Yadav, K.; Khursheed, A.; Rather, M.A. An updated and comprehensive review of the antiviral potential of essential oils and their chemical constituents with special focus on their mechanism of action against various influenza and coronaviruses. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 152, 104620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, B.S.; Whittaker, G.R.; Daniel, S. Influenza Virus-Mediated Membrane Fusion: Determinants of Hemagglutinin Fusogenic Activity and Experimental Approaches for Assessing Virus Fusion. Viruses 2012, 4, 1144–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Yao, L. Antiviral Effects of Plant-Derived Essential Oils and Their Components: An Updated Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, P.S.X.; Yusoff, K.; Lim, S.-H.E.; Chong, C.-M.; Lai, K.-S. Membrane Disruption Properties of Essential Oils—A Double-Edged Sword? Processes 2021, 9, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francenia Santos-Sánchez, N.; Salas-Coronado, R.; Villanueva-Cañongo, C.; Hernández-Carlos, B. Antioxidant Compounds and Their Antioxidant Mechanism. In Antioxidants; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandimali, N.; Bak, S.G.; Park, E.H. Free radicals and their impact on health and antioxidant defenses: A review. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S.; Sotondoshe, N.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Carvacrol and Thymol Hybrids: Potential Anticancer and Antibacterial Therapeutics. Molecules 2024, 29, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motie, F.M.; Howyzeh, M.S.; Ghanbariasad, A. Synergic effects of DL-limonene, R-limonene, and cisplatin on AKT, PI3K, and mTOR gene expression in MDA-MB-231 and 5637 cell lines. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 136216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Atawy, M.A.; Hanna, D.H.; Bashal, A.H.; Ahmed, H.A.; Alshammari, E.M.; Hamed, E.A.; Aljohani, A.R.; Omar, A.Z. Synthesis, Characterization, Antioxidant, and Anticancer Activity against Colon Cancer Cells of Some Cinnamaldehyde-Based Chalcone Derivatives. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rajhi, A.M.H.; Qanash, H.; Almuhayawi, M.S.; Al Jaouni, S.K.; Bakri, M.M.; Ganash, M.; Salama, H.M.; Selim, S.; Abdelghany, T.M. Molecular Interaction Studies and Phytochemical Characterization of Mentha pulegium L. Constituents with Multiple Biological Utilities as Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Anticancer and Anti-Hemolytic Agents. Molecules 2022, 27, 4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhy, I.; Paul, P.; Sharma, T.; Banerjee, S.; Mondal, A. Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Eugenol in Cancer: Recent Trends and Advancement. Life 2022, 12, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujahid, M.H.; Tarun, K.U. Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Antidiabetic, Antiglycation, and Biocompatibility Potential of Aqueous Zingiber officinale Rhizome (AZOME) Extract. J. Angiother. 2024, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Nguyen, K.T.; Nguyen, L.T.; Nguyen, C.; Nguyen, N.T.; Kuo, P.C.; Tran, G.B.; Anh, L.N.; Tran, T.; Nguyen, N.T. Research on chemical constituents, anti-bacterial and anti-cancer effects of components isolated from Zingiber officinale Roscoe from Vietnam. Plant Sci. Today 2023, 11, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sotto, A.; Mancinelli, R.; Gullì, M.; Eufemi, M.; Mammola, C.L.; Mazzanti, G.; Di Giacomo, S. Chemopreventive Potential of Caryophyllane Sesquiterpenes: An Overview of Preliminary Evidence. Cancers 2020, 12, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayala, B.; Bassole, I.H.; Scifo, R.; Gnoula, C.; Morel, L.; Lobaccaro, J.M.; Simpore, J. Anticancer activity of essential oils and their chemical components—A review. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2014, 4, 591–607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sharma, M.; Grewal, K.; Jandrotia, R.; Batish, D.R.; Singh, H.P.; Kohli, R.K. Essential oils as anticancer agents: Potential role in malignancies, drug delivery mechanisms, and immune system enhancement. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, J.J.L.; Pinheiro, A.A.V.; de Oliveira, A.F.M. Chemical Composition and Anticancer Activity of Essential Oils from Cyperaceae Species: A Comprehensive Review. Sci. Pharm. 2025, 93, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, M.; Estell, R.; Tellez, M.; Fredrickson, E. A retention index calculator simplifies identification of plant volatile organic compounds. Phytochem. Anal. 2009, 20, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussena, A. Résistance Bactérienne et Phytomolécules Antimicrobiennes Issues d’Ephedra Alata et d’Haloxylon Scoparium. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Mostaganem, Mostaganem, Algérie, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- NCCLS/National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests: Approved Standard M2-A7; National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards Wayne: Wayne, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Oussou, K.R.; Kanko, C.b.; Guessend, N.; Yolou, S.; Koukoua, G.; Dosso, M.; N’Guessan, Y.T.; Figueredo, G.; Chalchat, J.C. Activités antibactériennes des huiles essentielles de trois plantes aromatiques de Côte-d’Ivoire. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2004, 7, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koné, M.W.; Atindehou, K.K.; Kacou-N’Douba, A.; Dosso, M. Evaluation of 17 medicinal plants from Northern Côte d’Ivoire for their in vitro activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2007, 4, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 14476; Chemical Disinfectants and Antiseptics—Quantitative Suspension Test for the Evaluation of Virucidal Activity in the Medical Field—Test Method and Requirements (Phase 2/Step 1). European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- Strugała, P.; Urbaniak, A.; Kuryś, P.; Włoch, A.; Kral, T.; Ugorski, M.; Hof, M.; Gabrielska, J. Antioxidant and pro-apoptotic activities of purple potato extract and its interaction with liposomes, albumin and plasmid DNA. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 1271–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelli, W.; Bahri, F.; Romane, A.; Höferl, M.; Wanner, J.; Schmidt, E.; Jirovetz, L. Chemical Composition and Anti-inflammatory Activity of Algerian Thymus vulgaris L. Essential Oil. Nat. Product. Commun. 2017, 12, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Test No. 423: Acute Oral toxicity—Acute Toxic Class Method; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Name | tR (min) | KI Exp. SH-5 | KI Lit. | Ident. | Area (%) | ||||

| p-Cymene | 15.858 | 1024 | 1025 | KI, MS, S | 3.336 | 3.263 | 1.422 | ||

| Limonene | 16.32 | 1030 | 1030 | KI, MS, S | 6.313 | 10.438 | 22.64 | 12.403 | 1.31 |

| Eucalyptol | 16.594 | 1033 | 1032 | KI, MS, S | 1.592 | ||||

| γ-Terpinene | 19.435 | 1057 | 1060 | KI, MS, S | 2.598 | 2.608 | 1.369 | ||

| Linalool | 24.516 | 1099 | 1099 | KI, MS, S | 0.926 | 2.998 | 0.946 | ||

| Camphor | 29.888 | 1142 | 1144 | KI, MS, S | 2.163 | ||||

| Menthone | 31.189 | 1146 | 1148 | KI, MS, S | 4.863 | 0.834 | |||

| endo-Borneol | 33.139 | 1162 | 1167 | KI, MS | 4.116 | 0.98 | |||

| Pulegone | 41.761 | 1235 | 1237 | KI, MS, S | 24.542 | 4.452 | |||

| Geranial + Cinnamylaldehyde | 46.57 | 1272 | 1270/1274 | KI, MS, S | 32.146 | 1.667 | 50.675 | ||

| Unknown | 48.401 | 1289 | n.d. | n.d. | 4.031 | 2.556 | 1.055 | 2.134 | |

| Thymol | 49.582 | 1290 | 1291 | KI, MS, S | 25.095 | 15.954 | 6.26 | 8.553 | |

| Carvacrol | 50.472 | 1298 | 1299 | KI, MS, S | 41.098 | 21.933 | 1.091 | 8.891 | |

| Eugenol | 56.905 | 1355 | 1358 | KI, MS, S | 1.978 | 5.556 | 61.042 | ||

| Copaene | 58.873 | 1373 | 1376 | KI, MS, S | 1.777 | 0.257 | 1.943 | ||

| Caryophyllene | 64.058 | 1403 | 1419 | KI, MS, S | 1.062 | 10.272 | |||

| Humulene | 68.352 | 1440 | 1454 | KI, MS, S | 1.199 | ||||

| α-Curcumene | 72.269 | 1473 | 1485 | KI, MS, S | 2.02 | 4.375 | 1.376 | ||

| Zingiberene | 74.066 | 1493 | 1495 | KI, MS, S | 3.992 | 0.965 | 5.298 | 1.309 | 2.529 |

| β-Bisabolene | 75.537 | 1506 | 1509 | KI, MS, S | 1.638 | 3.148 | 1.444 | ||

| δ-Cadinene | 76.376 | 1520 | 1523 | KI, MS, S | 1.434 | 1.594 | |||

| β-Sesquiphellandrene | 77.283 | 1524 | 1527 | KI, MS | 1.684 | 2.961 | 1.174 | ||

| Microorganisms | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | Positive Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | 38.32 (0.15) | 29.22 (0.42) | 27.24 (0.15) | 33.17 (0.23) | 37.12 (0.00) | ETP: 10.0 (0.80) |

| P. aeruginosa | 17.45 (0.12) | 16.18 (0.55) | 11.32 (0.14) | 15.25 (0.00) | 14.14 (0.23) | ETP: 30.50 (0.20) |

| E. hormaechei | 32.45 (0.43) | 30.12 (0.14) | 27.08 (0.26) | 29.19 (0.12) | 28.31 (0.25) | ETP: 30.50 (0.20) |

| E. auxiensis | 28.29 (0.51) | 27.34 (0.12) | 25.15 (0.00) | 29.25 (0.45) | 30.21 (0.00) | RD: 22.50 (0.80) |

| K. pneumoniae | 20.39 (0.51) | 18.24 (0.00) | 20.18 (0.12) | 17.21 (0.00) | 21.27 (0.14) | ETP: 14.5 (1.20) |

| S. aureus | 40.23 (0.00) | 35.12 (0.32) | 38.32 (0.17) | 39.36 (0.41) | 39.08 (0.00) | RD: 21.0 (0.50) |

| Microorganisms | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | MIC (μL/mL) | 0.312 | 0.312 | 0.312 | 0.312 | 0.312 |

| MBC (μL/mL) | 0.312 | 0.625 | 0.312 | 0.625 | 0.312 | |

| MBC/MIC | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Activity | bactericidal | bactericidal | bactericidal | bactericidal | bactericidal | |

| P. aeruginosa | MIC (μL/mL) | 0.625 | 0.312 | 1.25 | 0.312 | 0.312 |

| MBC (μL/mL) | 0.625 | 0.312 | 10 | 0.625 | 0.312 | |

| MBC/MIC | 1 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 1 | |

| Activity | bactericidal | bactericidal | Bacteriostatic | bactericidal | bactericidal | |

| E. hormaechei | MIC (μL/mL) | 0.312 | 0.625 | 1.56 | 0.312 | 0.312 |

| MBC (μL/mL) | 0.625 | 0.625 | 1.56 | 0.625 | 0.312 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Activity | bactericidal | bactericidal | bactericidal | bactericidal | bactericidal | |

| E. auxiensis | MIC (μL/mL) | 2.5 | 5 | 5 | 2.5 | 5 |

| MBC (μL/mL) | 5 | 5 | 10 | 2.5 | 5 | |

| MBC/MIC | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Activity | bactericidal | bactericidal | bactericidal | bactericidal | bactericidal | |

| K. pneumoniae | MIC (μL/mL) | 5 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| MBC (μL/mL) | 5 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 5 | |

| MBC/MIC | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Activity | bactericidal | bactericidal | bactericidal | bactericidal | bactericidal | |

| S. aureus | MIC (μL/mL) | 0.312 | 0.625 | 0.312 | 0.312 | 0.312 |

| MBC (μL/mL) | 0.312 | 0.625 | 0.625 | 0.312 | 0.625 | |

| MBC/MIC | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Activity | bactericidal | bactericidal | bactericidal | bactericidal | bactericidal |

| Mixtures | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV | Log | 3 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 4 | 4 |

| % | 99.9 | 99.95 | >99.99 | 99.99 | 99.99 | |

| SD | 0 | 0.577 | 0.577 | 0 | 0 | |

| HAdV-5 | Log | 3.5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| % | 99.95 | 99.99 | 99.99 | >99.99 | 99.99 | |

| SD | 0.577 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mixture | |

|---|---|

| IC50 ± SD (μg/mL) | |

| M1 | 14.02 ± 3.72 |

| M2 | 27.75 ± 3.41 |

| M3 | 281.60 ± 23.78 |

| M4 | 60.11 ± 1.16 |

| M5 | 25.90 ± 0.34 |

| Species | Region | Geographic Coordinates |

|---|---|---|

| T. vulgaris | Kharrouba (Mostaganem) | Altitude: 80 m, longitude: 0°6′16″1 E, latitude: 35°58′742 ″N. |

| A. visnaga | Béni-saf | Altitude:25 m, longitude: 1°23′1″ O, latitude: 35°18′8″ N. |

| L. angustifolia | SebaaChioukh (Tlemcen) | Altitude: 514 m, longitude: 1°21′21 O, latitude: 35°9′22″ N. |

| M. pulegium | Abdelmalek Ramdane (Mostaganem) | Altitude: 101 m, longitude: 0°13′25 E, latitude: 36°06′46″ N. |

| C. sinensis | SidiBelAbbès | Altitude: 483 m, longitude: 0°38′29″ O, latitude: 35°12′0″ N. |

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTv | 24.85 | 24.85 | |||

| LAv | 18 | 18 | 29.6 | ||

| LMp | 12.74 | 13.16 | |||

| LLa | 12.74 | 13.16 | 22.11 | ||

| RZo | 24.12 | 41.84 | |||

| BCv | 3.94 | 21.66 | |||

| CSa | 3.94 | 6.45 | |||

| PCs | 53.21 | 53.21 | 50.4 | 52.02 | |

| Weight | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTv | 0.63 | 0.46 | |||

| LAv | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.95 | ||

| LMp | 0.34 | 0.28 | |||

| LLa | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.70 | ||

| RZo | 0.64 | 1.34 | |||

| BCv | 0.07 | 0.46 | |||

| CSa | 0.10 | 0.21 | |||

| PCs | 1.34 | 0.97 | 1.34 | 1.11 | |

| Weight | 2.52 | 1.83 | 2.65 | 2.13 | 3.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bahri, F.; Szumny, A.; Figiel, A.; Bahri, Y.; Włoch, A.; Bażanów, B.; Chwirot, A.; Gębarowski, T.; Bugno, P.; Bahri, E.M.; et al. Chemical Composition, Biological Activity, and In VivoToxicity of Essential Oils Extracted from Mixtures of Plants and Spices. Molecules 2025, 30, 4579. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234579

Bahri F, Szumny A, Figiel A, Bahri Y, Włoch A, Bażanów B, Chwirot A, Gębarowski T, Bugno P, Bahri EM, et al. Chemical Composition, Biological Activity, and In VivoToxicity of Essential Oils Extracted from Mixtures of Plants and Spices. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4579. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234579

Chicago/Turabian StyleBahri, Fouad, Antoni Szumny, Adam Figiel, Youcef Bahri, Aleksandra Włoch, Barbara Bażanów, Aleksandra Chwirot, Tomasz Gębarowski, Paulina Bugno, El Mokhtar Bahri, and et al. 2025. "Chemical Composition, Biological Activity, and In VivoToxicity of Essential Oils Extracted from Mixtures of Plants and Spices" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4579. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234579

APA StyleBahri, F., Szumny, A., Figiel, A., Bahri, Y., Włoch, A., Bażanów, B., Chwirot, A., Gębarowski, T., Bugno, P., Bahri, E. M., & Benabdeloued, R. N. (2025). Chemical Composition, Biological Activity, and In VivoToxicity of Essential Oils Extracted from Mixtures of Plants and Spices. Molecules, 30(23), 4579. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234579