Abstract

This study aimed to examine the role of ChatGPT in supporting travel decision-making by investigating its direct influence and the mediating effects of trust in AI-generated content, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use. Data were collected from 1208 qualified respondents and selected through non-probability convenience sampling from active digital travel communities on platforms. The results revealed that ChatGPT affects travel decision-making and also significantly influences users’ trust in AI-generated content, their perception of usefulness, and ease of use. Furthermore, all three mediators were found to significantly impact travel decision-making, and mediation analysis confirmed that these variables partially explain the link between ChatGPT usage and tourists’ behavioral intentions. These findings advance TAM by positioning trust as a central mechanism in AI adoption and demonstrate ChatGPT’s potential as a decision-support tool in tourism. This study offers practical insights for developers and policymakers seeking to improve transparency, reliability, and user experience of conversational AI in travel contexts.

1. Introduction

Travel decision-making is a multifaceted cognitive process shaped by personal, social, technological, and informational influences. In today’s digital landscape, travelers increasingly depend on online environments to evaluate destinations, compare alternatives, and construct itineraries [1]. Among emerging digital tools, artificial intelligence (AI)—particularly conversational agents such as ChatGPT—has become a transformative driver of tourist information search and evaluation. These systems provide rapid access to personalized, context-aware guidance that can streamline decision-making and reduce uncertainty [2,3].

ChatGPT represents a significant advancement in natural language processing, enabling human-like interactions, interpreting complex queries, and generating adaptive responses [4,5]. Within tourism contexts, ChatGPT increasingly functions not merely as an informational source but as a cognitive assistant that supports evaluation, comparison, and planning processes [6]. As travelers seek instant, tailored, and reliable insights, conversational AI systems shape preferences and behavioral outcomes more directly than traditional digital information sources [7].

Beyond functional assistance, ChatGPT also influences key psychological mechanisms—trust, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use—that determine whether tourists adopt AI tools in their planning activities [8,9]. Trust in AI-generated content is especially critical in contexts where decisions carry financial, experiential, or safety implications [10]. Similarly, perceived usefulness and ease of use reflect the tool’s ability to enhance planning efficiency and reduce cognitive load [11,12]. Together, these cognitive dimensions shape travelers’ willingness to rely on AI guidance [13].

The conceptual foundation for this inquiry is anchored in the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which—despite its parsimony—has evolved into one of the most widely validated and empirically supported frameworks for explaining user interactions with digital systems [14]. Extensive research across information systems, AI, and human–computer interactions has confirmed the robustness of TAM’s core propositions, namely that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use reliably predict individuals’ behavioral intentions toward new technologies [15]. Building on this foundation, recent theoretical developments in AI adoption have incorporated trust as an essential cognitive–affective construct, particularly in contexts where users rely on automated or generative content [16]. Positioning ChatGPT within this extended TAM framework offers a theoretically grounded lens for examining how travelers evaluate and integrate conversational AI into their decision-making processes [17,18]. Unlike traditional rule-based systems, generative AI operates through dynamic, dialogical interactions that heighten the relevance of trust, usefulness, and ease of use as key psychological mechanisms shaping user responses [19]. Accordingly, this study does not merely apply TAM but extends it by treating trust in AI-generated content as a central mediator that captures the psychological complexity of interacting with large language models. Through this perspective, the research aims to clarify how ChatGPT influences travel decision-making by activating these interconnected perceptual pathways.

While the tourism industry continues to undergo rapid digital transformation, the integration of generative AI —particularly conversational agents like ChatGPT—into travel decision-making remains insufficiently understood both theoretically and empirically [20]. Much of the existing research on AI in tourism has examined rule-based chatbots, static recommendation systems, or platform-specific applications that do not reflect the dynamic, adaptive, and dialogical capabilities of large language models (LLMs) [21,22]. This creates a substantial theoretical gap, as current frameworks do not adequately explain how travelers cognitively interpret, evaluate, or negotiate AI-generated advice in two-way conversational settings, where the user becomes an active participant rather than a passive information recipient [23]. This evolving interaction paradigm raises fundamental questions about the mechanisms through which generative AI shapes evaluation, reduces uncertainty, and influences actual behavioral outcomes during trip planning—questions that have not yet been systematically addressed.

Furthermore, although ChatGPT has rapidly become a widely accessed travel information resource [24], empirical research has not clarified how its use translates into actual decision-making outcomes. Existing studies often focus on general attitudes toward AI rather than specific cognitive pathways—such as trust, perceived usefulness, and ease of use—through which generative AI exerts influence [6,12,25]. Notably, trust in AI-generated content remains an underexplored construct in tourism, despite its established importance in automated and high-stakes decision environments [26]. This absence of empirical evidence limits our understanding of how travelers judge the credibility and reliability of AI responses and how such judgments shape behavioral intentions.

In addition, while the TAM has been widely applied across digital contexts [24,27], its extension to generative AI in tourism is still underdeveloped, especially in frameworks that consider trust as a central cognitive–affective mediator. No existing studies offer an integrated model that links exposure to generative AI with actual travel decision-making through these interconnected mediating perceptions. This gap highlights a critical need for a theoretically grounded and empirically validated framework that explains how generative AI systems shape tourist decision-making through cognitive and affective mechanisms. Addressing this gap not only advances AI adoption theory within tourism but also contributes novel empirical evidence on how conversational AI reshapes high-involvement consumer decisions. In addition, this gap underscores the need for a theory-driven investigation that adapts TAM to the unique characteristics of conversational AI—namely, interactivity, adaptiveness, and emergent reasoning. Accordingly, this study addresses these gaps by offering a large-scale empirical examination of how ChatGPT shapes travel decision-making, and by clarifying the mediating roles of trust, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use within an extended TAM framework.

To address the growing need to understand how generative AI tools influence tourist behavior, this study clearly aims to investigate the extent to which ChatGPT shapes travel decision-making by examining both its direct effects and the psychological mechanisms underlying users’ responses. The scope of the research is defined through three explicit objectives: (1) assess the effect of ChatGPT on travel decision-making, trust in AI-generated content, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use; (2) examine the effect of trust in AI-generated content, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use on travel decision-making; and (3) explore the mediating roles of trust in AI-generated content, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use in the link between ChatGPT and travel decision-making. These objectives establish a structured analytical pathway that clarifies how travelers evaluate AI-generated advice and how such evaluations inform their willingness to depend on ChatGPT during the travel-planning process. By framing the study in this way, the research positions trust as a central construct within an extended TAM framework, thereby expanding the theoretical underpinning and offering a more nuanced explanation of AI adoption in tourism contexts.

To further clarify this study’s direction, the following research questions guide the investigation:

- RQ1: To what extent does ChatGPT directly influence tourists’ travel decision-making?

- RQ2: How do trust in AI-generated content, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use affect travel decision-making?

- RQ3: How do trust, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use mediate the relationship between ChatGPT and travel decision-making?

This clearer articulation of the study’s aim, scope, and guiding questions strengthens the theoretical framing and provides a coherent foundation for the empirical analysis that follows.

2. Conceptual Framework for AI and Consumer Decision Behavior

Tourism behavior is widely recognized as a multi-phased and highly heterogeneous phenomenon, shaped by variations in travel purpose, prior experience, digital literacy, cultural background, risk perceptions, and information-search preferences. Tourists do not progress through the decision journey in a uniform manner, nor do they assign the same weight to the factors influencing their choices [28]. Acknowledging this complexity, the present study does not treat “tourism” or “tourists” as homogeneous constructs. Instead, it focuses on a specific and theoretically meaningful stage of the tourism buying process—the evaluation of information during the decision-making phase. This phase represents a universal cognitive task shared across diverse tourist types, even when their motivations and behaviors differ [10]. Within this stage, higher-order perceptual constructs such as trust, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use function as fundamental cognitive filters through which travelers assess digital content and AI-generated advice [13]. Accordingly, the study does not distinguish between specific types of travel-related decisions (e.g., flights, accommodations, sightseeing) or between short and long trips, as the aim is to examine how travelers evaluate and respond to AI-generated information at the cognitive level, regardless of the trip format or product category. By centering the analysis on this shared cognitive layer rather than on segment-specific motives, the study aligns with established research in tourism buying behavior and provides a focused lens for examining interactions with generative conversational AI.

Building on this behavioral foundation, the conceptual orientation of the study is anchored in the TAM, which—despite its simplicity—remains one of the most empirically validated and theoretically robust frameworks for explaining user cognition in technology-mediated environments [29,30]. TAM directly captures the perceptual mechanisms most relevant to understanding how individuals evaluate AI-generated information: perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and trust in system output [31]. This makes TAM particularly suitable for examining generative AI in tourism, where travelers’ decisions are shaped by cognitive effort, system reliability, and perceived informational value [24]. Recent extensions of TAM have further incorporated trust as a central cognitive–affective construct, especially in contexts involving automated or AI-generated content [15]. Positioning ChatGPT within this extended TAM framework, therefore, provides a theoretically grounded way to explain how travelers assess, internalize, and act upon conversational AI responses.

In this sense, the present study responds to a clear conceptual gap in the social science literature: although generative AI tools such as ChatGPT are increasingly involved in shaping consumer evaluations [32,33], existing theories have not sufficiently explained how travelers cognitively process AI-generated advice within multi-phased decision journeys. The integration of behavioral heterogeneity with a TAM-based cognitive framework allows this study to offer a coherent conceptual foundation for understanding how generative AI influences travel decision-making through trust, usefulness, and ease of use. This combined perspective establishes a structured theoretical platform for the hypotheses that follow.

2.1. ChatGPT and Travel Decision-Making

The integration of ChatGPT into the travel planning process introduces a new form of intelligent assistance that aligns with evolving theoretical perspectives on AI-supported consumer decision behavior. In contemporary digital environments, travelers increasingly rely on interactive systems that reduce uncertainty, facilitate information evaluation, and support complex reasoning during the decision journey [6,24]. As a generative conversational agent, ChatGPT functions as a cognitive stimulus that activates key perceptual processes involved in evaluating alternatives and forming travel-related judgments [34,35]. Building on the TAM, user interaction with a technological system begins with an external input that shapes subsequent cognitive evaluations—most prominently perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and trust [13,15]. Although TAM traditionally highlights usefulness and ease of use as central precursors to behavioral intention, recent work emphasizes that the system’s inherent capabilities must first generate user engagement [16]. In this context, ChatGPT provides immediate, tailored responses that simulate human-like consultation, thereby reducing perceived cognitive load and uncertainty during travel planning [3,6]. These functionalities position ChatGPT as a meaningful driver of decision quality, enabling travelers to clarify preferences, compare alternatives, and navigate unfamiliar choices with greater confidence [25]. Accordingly, and consistent with theoretical assumptions in TAM as well as emerging evidence on conversational AI in tourism, it is posited that interacting with ChatGPT contributes directly to more effective travel decision outcomes [10]. Hence, the following hypothesis is highlighted:

H1.

The use of ChatGPT has a significant positive effect on tourists’ travel decision-making.

2.2. ChatGPT and Trust in AI-Generated Content

Within the broader field of AI-driven consumer decision behavior, trust has become a foundational perceptual mechanism that determines whether individuals accept, rely on, or act upon system-generated recommendations [36]. As AI tools increasingly mediate information search and evaluation, trust operates as a cognitive filter through which users judge the credibility, accuracy, and integrity of machine-produced content [37]. Unlike rule-based decision aids, ChatGPT’s conversational structure and ability to generate contextually adaptive, human-like responses position it as a qualitatively different type of informational agent—one whose output is evaluated not only for factual value but also for perceived transparency and reasoning quality [5,38]. Emerging theoretical extensions of the TAM highlight that trust functions not merely as a by-product of system interaction but as a core antecedent enabling meaningful engagement with intelligent technologies [39,40]. From this perspective, users’ willingness to adopt generative AI hinges on their belief that its outputs are reliable, unbiased, and aligned with their expectations [41]. ChatGPT’s fluency, responsiveness, and adaptive dialogue capabilities can enhance these perceptions by simulating attributes typically associated with knowledgeable human advisors, thereby reinforcing trust formation through perceived coherence and contextual accuracy [42]. At the same time, trust in AI-generated content remains contingent on consistent system performance [43]. Users evaluate ChatGPT’s trustworthiness based on its ability to provide accurate and contextually relevant information while avoiding errors or misleading guidance. Consequently, exposure to ChatGPT is expected to shape users’ cognitive assessment of the system’s reliability and integrity, ultimately influencing their likelihood of accepting its recommendations [10,43]. Based on this, the following hypothesis is suggested:

H2.

The use of ChatGPT has a significant positive effect on users’ trust in AI-generated content.

2.3. ChatGPT and Perceived Usefulness

Within the broader domain of AI-enabled consumer decision behavior, perceived usefulness remains one of the most influential cognitive evaluations shaping how individuals integrate intelligent systems into task-related processes. As travelers navigate increasingly complex digital environments, they seek technologies that can enhance the efficiency, accuracy, and confidence of their planning efforts [36]. ChatGPT’s capacity to synthesize dispersed information into coherent, context-specific, and personalized responses positions it as a high-value decision-support tool, allowing users to bypass fragmented online searches and receive targeted guidance through a conversational interface [44]. From a theoretical standpoint, the TAM conceptualizes perceived usefulness as the degree to which a system is believed to improve task performance and facilitate better outcomes [27,45]. In the context of travel decision behavior, this translates into the traveler’s belief that ChatGPT meaningfully contributes to informed evaluations, reduces cognitive effort, and enhances planning clarity [6,46]. As users interact with ChatGPT, they assess not only the correctness of its outputs but also the degree to which the system supports goal-oriented decision tasks—ranging from itinerary comparison to contextual insight generation [47]. These cognitive evaluations align with AI adoption research showing that perceived usefulness becomes a central predictor of continued system reliance, especially when users experience tangible improvements in speed, quality, or confidence of their decisions [3,37]. Accordingly, user experience with ChatGPT is expected to strengthen perceptions of its instrumental value, thereby shaping behavioral acceptance and reinforcing its role as a meaningful contributor to travel decision-making [48]. So, the following hypothesis is developed:

H3.

The use of ChatGPT has a significant positive effect on tourists’ perceived usefulness of the tool.

2.4. ChatGPT and Perceived Ease of Use

Within AI-driven consumer decision environments, ease of use has become a defining criterion through which users evaluate whether a system can be seamlessly incorporated into their decision-making processes [47]. As travelers increasingly rely on digital tools to navigate complex planning tasks, their willingness to adopt a technology often depends on the cognitive effort required to interact with it [49]. Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT offer a distinct advantage in this regard: by enabling natural-language interaction, the system removes the procedural barriers, technical commands, and structured inputs that characterize traditional digital platforms [2]. This conversational fluidity allows users—including those with limited technical experience—to access meaningful information without encountering a steep learning curve [50]. The TAM conceptualizes perceived ease of use as the extent to which a system is believed to be free of physical or cognitive effort [51]. ChatGPT’s intuitive interface, rapid response generation, and ability to interpret unstructured user queries align directly with this construct by minimizing friction throughout the interaction process [52]. Unlike rigid booking engines or search platforms that demand sequential navigation and structured inputs, ChatGPT offers an adaptive, dialogic experience in which users can refine queries naturally, receive clarifications, and progress through iterative information search with minimal effort [2]. AI adoption research consistently shows that when users experience low-effort interactions, they are more likely to perceive the technology as accessible, user-friendly, and compatible with their existing digital habits—factors that strongly predict acceptance and behavioral intention [50,53]. Accordingly, ChatGPT’s design characteristics are expected to significantly enhance perceived ease of use, reinforcing its suitability as a decision-support tool in the tourism context [54]. Hence, the following hypothesis is highlighted:

H4.

The use of ChatGPT has a significant positive effect on tourists’ perceived ease of use.

2.5. Trust in AI-Generated Content and Travel Decision-Making

Within AI-mediated consumer decision environments, trust functions as a foundational cognitive mechanism through which users evaluate the credibility and actionability of algorithmically generated information [47]. In tourism—a domain characterized by financial risk, experiential uncertainty, and high involvement—trust becomes the decisive factor determining whether travelers translate digital recommendations into behavioral intention [55,56]. Because users cannot manually validate every piece of information produced by generative AI tools such as ChatGPT, they rely instead on perceived accuracy, coherence, consistency, and alignment with their expectations to form judgments of trustworthiness [13]. These perceptions collectively shape whether AI-generated content is accepted as reliable enough to guide real-world travel choices [57]. Although the original TAM framework emphasizes perceived usefulness and ease of use, contemporary extensions of the model increasingly position trust as a central antecedent in contexts characterized by automation, autonomy, and reduced human oversight [58]. In the tourism planning process, trust operates not merely as a supportive belief but as a cognitive enabler: it allows users to rely on ChatGPT’s suggestions, simplify information-processing demands, and move toward finalizing decisions without exhaustive cross-verification [28]. As generative AI becomes more embedded in consumer decision behavior, the perceived trustworthiness of its outputs plays a crucial role in determining whether travelers are willing to act upon the advice it provides [57]. Accordingly, trust in AI-generated content is expected to exert a direct and substantial influence on travel decision-making, shaping both the confidence users place in ChatGPT and the behavioral intentions that follow [8,9,24]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is developed:

H5.

Trust in AI-generated content has a significant positive effect on tourists’ travel decision-making.

2.6. Perceived Usefulness and Travel Decision-Making

Within AI-supported consumer decision environments, perceived usefulness represents a central cognitive evaluation through which travelers judge whether an intelligent system meaningfully enhances their ability to plan, compare, and select among alternatives [59]. In the TAM, usefulness is identified as a primary determinant of behavioral intention, reflecting the user’s belief that a system improves task performance [39]. This construct becomes particularly salient in tourism, where decisions are complex, information-intensive, and personally consequential [36]. Travelers are not merely seeking data; they are seeking interpretive guidance that reduces uncertainty and increases decision confidence [28]. Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT contribute to perceived usefulness by synthesizing fragmented information, contextualizing recommendations, and delivering tailored insights that align with user-defined constraints [6,7]. These capabilities allow travelers to bypass traditional search efforts and move more efficiently through the evaluation phase of the decision journey. When users experience ChatGPT as a system that clarifies options, accelerates planning, or enhances decision accuracy, they cognitively categorize the tool as instrumental to achieving their travel objectives [25,28]. Thus, usefulness operates not as an abstract perception but as a practical determinant of commitment: when travelers perceive ChatGPT as genuinely helpful, this perception becomes a catalyst that strengthens their willingness to translate AI-generated advice into actual travel choices [10]. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is reported:

H6.

Perceived usefulness has a significant positive effect on tourists’ travel decision-making.

2.7. Perceived Ease of Use and Travel Decision-Making

In AI-supported consumer decision environments, the cognitive effort required to interact with a system shapes both user engagement and downstream behavioral responses [47]. Perceived ease of use—defined within the TAM as the degree to which a system is free of mental or operational burden—plays a decisive role in reducing the cognitive load associated with complex evaluations [2,50]. In tourism, where travelers must simultaneously process interdependent variables such as timing, cost, logistics, and personal preferences, tools like ChatGPT derive much of their value from the intuitiveness and frictionless nature of their interaction design [28,60]. A system that feels effortless to navigate enables users to focus more fully on the evaluative task itself rather than on the mechanics of using the technology [24,61]. Within the TAM logic, ease of use traditionally operates through its influence on perceived usefulness; however, in high-involvement and time-sensitive contexts such as travel planning, ease of use can also exert a direct effect on decision-making [39]. When travelers experience interactional fluency and confidence while using ChatGPT, they are more likely to maintain engagement, avoid decision fatigue, and complete the planning process with greater trust in the generated outcomes [36,62]. This places ease of use not merely as an antecedent of adoption, but as a cognitive facilitator that supports the final act of commitment in the decision journey [63]. So, the following hypothesis is suggested:

H7.

Perceived ease of use has a significant positive effect on tourists’ travel decision-making.

2.8. The Mediating Role of Trust in AI-Generated Content

Within AI-supported consumer decision environments, the pathway from system exposure to behavioral action is rarely linear. Travelers’ engagement with ChatGPT involves not only processing functional outputs but also forming judgments about the credibility, integrity, and reliability of the information provided [17,64]. Although features such as rapid responses, dialogic fluency, and contextual relevance may encourage initial interaction, these features alone do not determine whether users ultimately incorporate the system’s recommendations into their decisions [2,65]. Instead, the influence of ChatGPT is filtered through trust, a core psychological mechanism that determines whether AI-generated content is accepted, questioned, or rejected [13]. In contemporary extensions of the TAM—particularly those applied to AI—trust is conceptualized as a pivotal mediating construct that bridges the gap between cognitive appraisal and behavioral intention [66]. Without sufficient trust, even highly sophisticated or contextually rich information may be dismissed, second-guessed, or subjected to extensive verification [67,68]. Conversely, when travelers perceive ChatGPT’s output as credible, impartial, and accurate, they are more willing to internalize its suggestions and translate them into concrete decisions [57]. This mediating role is especially salient in tourism, a domain characterized by high uncertainty, information asymmetry, and limited opportunities for direct validation. Travelers often depend on advisory content that cannot be independently verified prior to consumption [13]. In such contexts, trust functions as the cognitive mechanism that transforms system interaction into committed decision behavior, enabling users to rely confidently on ChatGPT during the planning process [10]. Consequently, the following hypothesis is adopted:

H8.

Trust in AI-generated content mediates the relationship between ChatGPT usage and tourists’ travel decision-making.

2.9. The Mediating Role of Perceived Usefulness

In AI-supported consumer decision environments, the influence of a system such as ChatGPT seldom emerges from mere exposure to technology. Instead, behavioral outcomes depend on the user’s cognitive appraisal of how effectively the tool contributes to their goals [36]. Within this evaluative process, perceived usefulness functions as a central psychological mechanism through which travelers assess whether ChatGPT enhances clarity, reduces complexity, or improves the overall quality of their decision-making [17,69]. Although ChatGPT can simplify information search, generate tailored suggestions, and structure complex choices, these capabilities affect behavior only when users consciously interpret the system as offering meaningful value [13]. In this sense, perceived usefulness operates as a cognitive filter: even superior system performance will not translate into action unless it is recognized as beneficial [70,71]. This aligns with extended TAM frameworks, where perceived usefulness is conceptualized as a key determinant that mediates the relationship between technology use and behavioral intention [14]. In the travel context—where decisions involve risk, uncertainty, and high personal relevance—perceived usefulness becomes especially influential. Travelers who judge ChatGPT as instrumental in organizing information, validating options, or providing decision confidence are significantly more likely to rely on its guidance [20,25]. Thus, the effect of ChatGPT on travel decision-making is expected to be indirect, shaped not simply by the presence of the tool but by the degree to which users perceive it as genuinely helpful in supporting their planning objectives [3,6]. Hence, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H9.

Perceived usefulness mediates the relationship between ChatGPT usage and tourists’ travel decision-making.

2.10. The Mediating Role of Perceived Ease of Use

In AI-supported consumer decision environments, the ease with which users can interact with a system plays a foundational role in determining whether they engage meaningfully with its features [13]. For travelers navigating information-intensive and time-pressured planning tasks, a tool that feels intuitive and effortless reduces cognitive strain and increases their willingness to rely on it [72]. Accordingly, perceived ease of use functions not merely as a usability attribute, but as a psychological mechanism that shapes how users internalize and respond to AI-generated guidance [10]. Within the extended TAM literature, ease of use is traditionally conceptualized as an antecedent to perceived usefulness, influencing whether users view a system as instrumental to their goals [73]. However, in complex real-world contexts such as tourism—where decisions entail uncertainty, risk, and personalization—perceived ease of use also operates as a mediating construct. It determines the degree to which initial interactions with a tool like ChatGPT translate into deeper engagement and ultimately into decision commitment [12,74]. When travelers experience smooth, low-friction interaction, they are more inclined to perceive the system as competent, reliable, and supportive. This favorable cognitive appraisal enhances their openness to the system’s suggestions and increases the likelihood that they will incorporate AI-generated advice into their decision process [28]. Thus, perceived ease of use serves as an indirect pathway through which ChatGPT influences travel decisions—reinforcing positive system evaluations and strengthening behavioral adoption [19,75]. So, the following hypothesis is suggested:

H10.

Perceived ease of use mediates the relationship between ChatGPT usage and tourists’ travel decision-making.

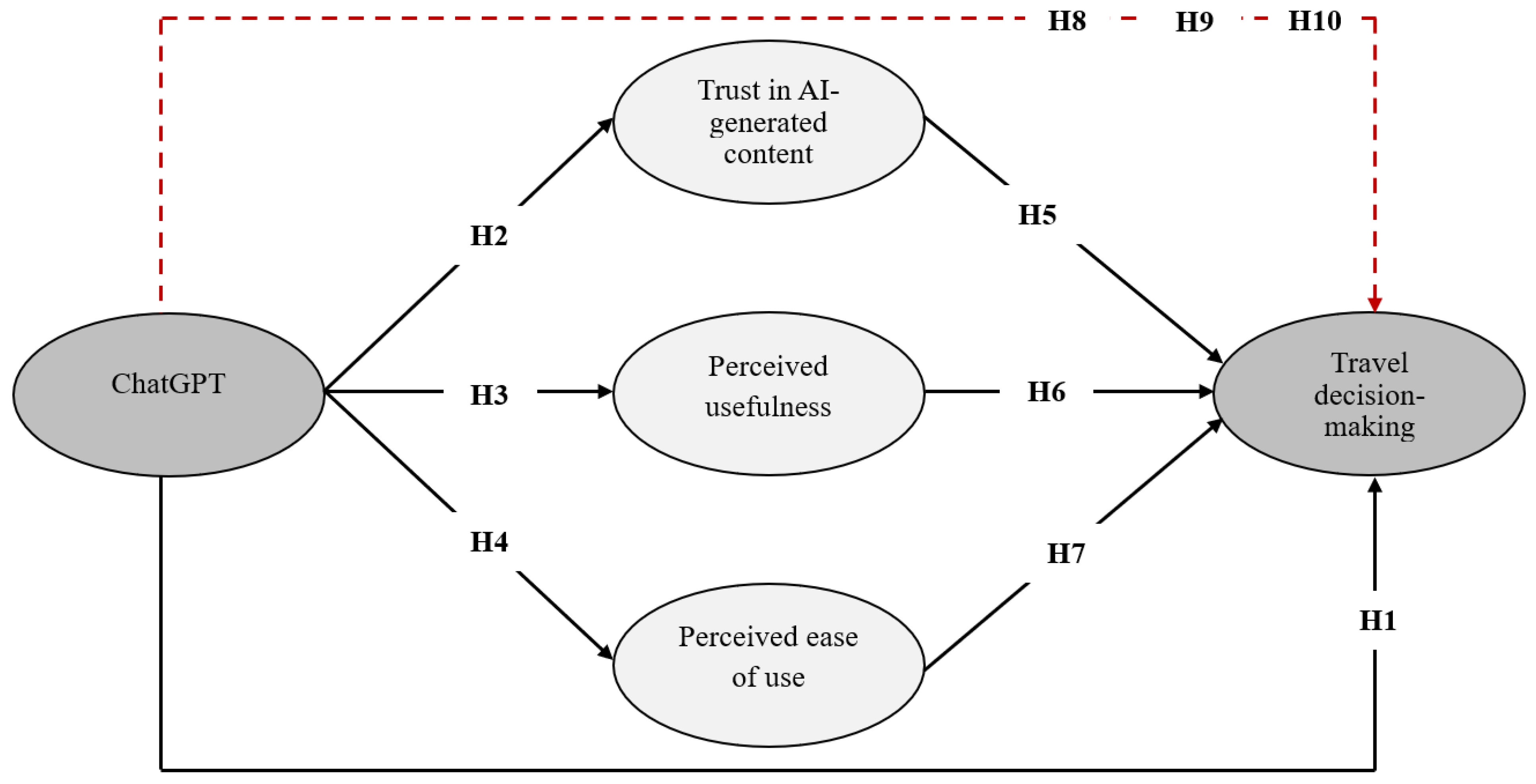

In alignment with TAM and its relevance to understanding user interaction with AI systems, the following conceptual model has been developed to capture the hypothesized relationships examined in this study (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The conceptual model.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

Understanding how travelers engage with ChatGPT during the planning stages of their trips required a method that could reach users in the very environments where such behaviors naturally occur—digital spaces [6,61]. Rather than relying on traditional sampling frames, the study embraced a digitally native approach, grounded in the logic that those who use conversational AI for tourism purposes are likely to be active in online communities. Consequently, data collection was embedded within the platforms that tech-savvy travelers already inhabit. This intentional focus on digitally active, tech-savvy users reflects the population segment most likely to adopt and meaningfully interact with AI-based travel tools [49], making the sampling strategy appropriate for the study’s aims. Given that the global population of travelers who use ChatGPT cannot be precisely quantified, the study operationally defines its research population as individuals who used ChatGPT for travel-related decisions within the past 12 months. Accordingly, the population is treated as analytically relevant yet numerically unbounded, a condition commonly encountered in studies examining emerging digital platforms and AI-enabled behaviors [13]. Because the global number of such users cannot be accurately measured across digital ecosystems, this study adopts a functional definition of the population rather than attempting numerical estimation, a practice consistent with established methodologies in digital-behavior and AI-usage research.

Between January and April 2025, the study deployed an electronic questionnaire, intentionally crafted to capture the nuanced experience of using ChatGPT for travel decision-making. A pilot test was not conducted because the instrument did not aim to develop new scales but to apply previously validated constructs to real users of ChatGPT in naturally occurring digital environments. In this context, the absence of a pilot test reflects a deliberate methodological choice rather than an omission, as the survey items were adapted from well-established scales that have demonstrated validity and reliability across prior empirical studies. Instead of piloting, methodological rigor was ensured through comprehensive post-data-collection validation procedures, detailed later in this section, which served a function equivalent to—and more statistically rigorous than—a preliminary pilot assessment. The survey was disseminated through a variety of channels, including organic posts in open-access travel forums, targeted direct outreach within interest-based groups, and carefully segmented digital campaigns. These platforms were not randomly selected but were chosen for their strong alignment with the study’s core audience—individuals who frequently seek, share, and discuss travel experiences through digital tools. As such, the sample represents early adopters who are more engaged with emerging technologies than the general traveler population, a characteristic that is acknowledged as part of the study’s analytical scope. This sampling approach is considered analytically representative because early adopters constitute the population segment most likely to engage meaningfully with conversational AI, aligning directly with the study’s theoretical and empirical scope.

To maintain privacy and comply with platform policies, the specific names of the online groups and communities used for recruitment are not disclosed [76]. However, these groups fell into three clearly identifiable categories: (a) large international travel-planning forums; (b) destination-focused discussion groups; and (c) AI-oriented digital communities where travelers compare and evaluate itinerary suggestions. Across these categories, follower counts typically range from approximately 50,000 to over 300,000 members. Recruitment was proportionally distributed across these group types, ensuring that no single community dominated the sample. This categorical description provides sufficient transparency for methodological replication without compromising confidentiality.

Participants were not drawn randomly; instead, the study employed a purposive, convenience-based approach, optimized for relevance rather than representativeness [77]. In the light of [78], this decision was grounded in the assumption that prior exposure to ChatGPT for tourism-related inquiries was a prerequisite for valid responses. To uphold this criterion, the survey introduced a gatekeeping mechanism at its outset: respondents were first asked if they had used ChatGPT in the past 12 months for any tourism-related purpose. Only those answering “yes” proceeded to a secondary screening prompt, which clarified whether the tool was used to actively support travel decisions—such as comparing destinations or finalizing plans—rather than for casual or unrelated exploration. Only respondents meeting both conditions were retained. Out of a total of 2187 individuals who accessed the survey invitation, 1208 participants met the screening criteria and completed the full instrument. The remaining 979 responses were excluded due to insufficient relevance—either through lack of ChatGPT usage or through usage unrelated to decision-making. These 1208 valid cases form the empirical basis of the study’s analysis. Given both the size of the final sample and the targeted recruitment strategy, the dataset provides strong statistical power and a robust empirical foundation for testing the proposed relationships [49]. With this large sample size (n = 1208) drawn from naturally occurring AI-engaged communities, the dataset achieves strong statistical power and reflects real-world usage patterns, further supporting the analytical representativeness of the sample.

Given the rapid evolution of ChatGPT models and the coexistence of both free and paid versions during the data collection period, the study acknowledges that participants may have interacted with different system variants (e.g., GPT-4). While the survey did not differentiate between model types, this variability reflects real-world usage patterns among travelers. Importantly, the study focuses on users’ perceptions of trust, usefulness, and ease of use—constructs that remain meaningful regardless of the specific model version employed. This approach ensures that the analysis captures the experiential dimension of AI-assisted travel planning rather than model-by-model performance differences.

To ensure methodological rigor, the measurement model underwent a comprehensive set of validation procedures, including Common Method Bias testing, factor loadings, Cronbach’s Alpha, Composite Reliability (CR), Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Variance Inflation Factors (VIF), Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), the HTMT ratio, and correlation matrix analysis. These procedures collectively confirm convergent validity, discriminant validity, construct validity, and internal consistency reliability for all study constructs. All reliability indicators exceeded recommended thresholds, demonstrating that the questionnaire was statistically robust even without a preliminary pilot test.

3.2. Measures

The study utilized a structured measurement framework built upon previously validated scales to ensure conceptual accuracy and empirical reliability. All constructs were assessed using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), allowing for consistent evaluation of participants’ perceptions across the different dimensions of the research model [10]. The questionnaire was divided into two primary sections: demographic background and latent construct measurement. A complete list of all measurement items used for each construct is provided in Appendix A.

Demographic variables: Participants were first asked to provide basic demographic information to help describe the sample and control for potential background effects. These variables included gender, age group, nationality (open-ended), and highest level of educational attainment.

ChatGPT usage: To assess the role of ChatGPT in tourism-related contexts, four items were adapted from [79], focusing on the perceived relevance and engagement with the tool during travel planning. Sample statements include “I feel that it is important to use ChatGPT when searching for hospitality/tourism information.” These items captured both frequency and perceived necessity of using the tool.

Trust in AI-generated content: Trust was measured using a four-item scale drawn from [80], designed to assess participants’ confidence in the reliability, quality, and credibility of responses provided by ChatGPT. A sample item is “ChatGPT’s response and advice can meet my expectations.” This construct was essential in determining users’ willingness to rely on AI-driven suggestions.

Perceived usefulness: Three items, also adapted from [80], were used to gauge the degree to which participants felt that ChatGPT enhanced their effectiveness during travel planning. For example, respondents evaluated statements such as “I feel that ChatGPT is competent.” This construct reflects the cognitive value attributed to the tool in facilitating goal achievement.

Perceived ease of use: Two items adapted from [79] were included to assess how intuitively and effortlessly users were able to interact with ChatGPT. A representative item includes: “ChatGPT is easily accessible.” These measures provided insight into the friction (or lack thereof) in system usability.

Travel decision-making support: To capture the degree to which ChatGPT influenced concrete planning behavior, three items were drawn from [28] and [81]. These statements evaluated the user’s progression toward actionable travel decisions, such as “I feel confident in the travel choices I make.” This construct served as the study’s primary dependent variable.

3.3. Common Method Bias

Given the cross-sectional nature of data collection and reliance on self-reported measures, attention was directed toward evaluating the potential impact of common method variance (CMV)—a known threat in single-source surveys that may distort the observed relationships among variables. Recognizing that participants responded to all items within a single survey instrument at one time point, the risk of systematic response bias warranted formal assessment [82]. To address this, the study employed two commonly accepted statistical techniques to detect CMV: Harman’s single-factor test and Principal Component Analysis (PCA), following the guidelines recommended by [83]. The unrotated factor solution revealed no dominant factor, and the first component accounted for well under 50% of the total variance, indicating that the variance is adequately distributed across multiple constructs [84]. These results suggest that no substantial method bias exists and that the relationships among the variables are unlikely to have been artificially inflated by the data collection method. As such, the validity of the study’s findings is not considered compromised by CMV.

In addition to detecting potential CMV, PCA also served to preliminarily assess the factorial structure of the measurement items. A principal component analysis with varimax rotation was conducted to evaluate whether the observed items converged on the theoretically expected constructs. The analysis demonstrated clear factor separation, with all items loading strongly on their intended components and no cross-loadings exceeding acceptable thresholds. Eigenvalues for all retained components were above 1, and the cumulative variance explained exceeded recommended benchmarks, confirming that the factors captured a substantial proportion of the underlying variance. These results further validate the dimensionality and robustness of the measurement model prior to SEM estimation.

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Respondents’ Profile

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the respondents, including gender, age, nationality, and educational attainment. The sample consists of 57% males and 43% females. In terms of age distribution, participants are fairly spread across categories, with the majority falling between 25 and 45 years. Regarding nationality, the distribution indicates a mix of Arab (46.2%) and non-Arab (53.8%) respondents, serving only as a descriptive overview of the sample’s composition. Educationally, the majority of respondents (72.1%) hold a bachelor’s degree, followed by 18.9% with less than a bachelor’s level and 9% with postgraduate qualifications. These demographic details are presented to provide a clear and transparent description of the participants included in the study.

Table 1.

Respondents’ profile.

4.2. Measurement Model

Before moving into deeper structural interpretations, it was essential to evaluate whether the core constructs of the study were captured with sufficient clarity, coherence, and reliability. Rather than relying solely on numerical adequacy, the assessment aimed to verify that each latent construct was measured in a way that aligns meaningfully with its theoretical foundation and empirical behavior.

The analysis began by examining the consistency of item responses within each construct. Across all five dimensions, the measurement indicators demonstrated strong cohesion—evident through high item loadings, with most exceeding 0.85. Internal reliability metrics, such as Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR), further confirmed that each set of items performed as a unified scale rather than a collection of loosely connected variables. Notably, AVE scores comfortably surpassed the accepted minimum, indicating that each construct successfully captured more shared variance than error, which is essential in models dealing with perceptual and cognitive phenomena [85]. To safeguard against inflation or redundancy in the relationships between variables, multicollinearity was also assessed using VIF scores, which all remained well within acceptable bounds as Table 2 showed. This reinforces confidence that the effects observed in later structural paths are genuine rather than statistical artifacts.

Table 2.

Measurement model.

Looking at the broader picture of model structure, results from confirmatory factor analysis in Table 3 offered additional reassurance. The overall fit of the measurement model was not just statistically acceptable—it was strong by conventional standards. With a CMIN/DF ratio below 3 and goodness-of-fit indices (GFI, AGFI, CFI, NFI) all approaching or exceeding 0.95, the model reflects a close alignment between the theoretical framework and the actual data. The remarkably low RMSEA value of 0.008 points to a minimal level of approximation error, reinforcing the conclusion that the model holds together with notable precision [85].

Table 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

The results presented in Table 4 and Table 5 collectively confirm that the model’s constructs exhibit strong discriminant validity. In Table 4, the square roots of the AVE values, shown on the diagonal, are consistently higher than any of the inter-construct correlations in their respective rows and columns. This pattern indicates that each construct captures substantially more variance from its own indicators than from other constructs, demonstrating clear conceptual separation. For instance, the square root of the AVE for Perceived ease of use is 0.907—substantially higher than its correlations with Perceived usefulness (0.453) and Trust in AI-generated content (0.555). Likewise, Table 5 reinforces this evidence through HTMT ratios that remain well below the conservative 0.85 threshold. The highest observed HTMT value is 0.613 (between Trust and Perceived usefulness), which still reflects a safe degree of distinctiveness. Taken together, these results confirm that the constructs are empirically distinguishable, thereby supporting the validity and reliability of subsequent interpretations within the structural model [85].

Table 4.

Squared roots of AVE.

Table 5.

Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio.

To complement the AVE and HTMT assessments, a correlation matrix was computed to further evaluate inter-construct relationships and verify the absence of multicollinearity. As shown in Table 6, all correlations fall within acceptable theoretical boundaries and remain well below the critical threshold of 0.85, confirming adequate discriminant validity and supporting the robustness of the measurement model.

Table 6.

Correlation Matrix.

4.3. Structure Model

The results of the structural model (Table 7) provided full empirical support for all seven proposed direct hypotheses. Hypothesis H1, which proposed that ChatGPT usage has a direct effect on travel decision-making, was confirmed, with a significant path coefficient (β = 0.554, t = 7.103, p < 0.001), indicating a strong positive relationship. Hypothesis H2, predicting that ChatGPT positively influences trust in AI-generated content, was also confirmed (β = 0.612, t = 7.649, p < 0.001), suggesting that exposure to the tool enhances users’ confidence in the credibility of its outputs. Similarly, H3 was supported, as ChatGPT showed a significant impact on perceived usefulness (β = 0.508, t = 5.644, p < 0.001), reflecting its value as a helpful planning tool. In support of H4, ChatGPT was also found to positively affect perceived ease of use (β = 0.411, t = 5.479, p < 0.001), confirming that users find the system intuitive and accessible. Hypothesis H5, which linked trust in AI-generated content to travel decision-making, was confirmed as well (β = 0.602, t = 7.341, p < 0.001), highlighting the importance of trust in shaping behavioral intentions. In line with expectations, H6 was also supported, showing that perceived usefulness significantly contributes to travel decision-making (β = 0.488, t = 5.951, p < 0.001). Finally, H7, which proposed that perceived ease of use has a positive effect on travel decision-making, was confirmed (β = 0.366, t = 5.013, p < 0.001), indicating that the more effortless the interaction, the more likely users are to act on the tool’s recommendations. These findings confirm the validity of all direct path hypotheses, reinforcing the theoretical model and highlighting the significant role of ChatGPT and associated user perceptions in influencing travel behavior.

Table 7.

Direct effects.

The mediation analysis using bias-corrected bootstrapping provided strong evidence in support of all three hypothesized indirect effects (Table 8). Hypothesis H8, which suggested that the effect of ChatGPT on travel decision-making is mediated by trust in AI-generated content, was confirmed (β = 0.368, S.E = 0.069), with the confidence interval (LLCI = 0.232, ULCI = 0.503) excluding zero—indicating a statistically significant mediation effect. Similarly, H9 proposed that perceived usefulness would act as a mediator in the relationship between ChatGPT usage and travel decisions. This hypothesis was also supported (β = 0.247, S.E = 0.060), as the bootstrapped confidence interval (LLCI = 0.129, ULCI = 0.364) demonstrated significance. Lastly, Hypothesis H10, which tested perceived ease of use as a mediating construct, was confirmed as well (β = 0.150, S.E = 0.051), with its confidence interval (LLCI = 0.105, ULCI = 0.249) entirely above zero.

Table 8.

Bias-Corrected Bootstrapped result.

5. Discussion

Grounded in the extended TAM, this study explored how ChatGPT shapes user behavior in the context of travel planning by influencing key perceptual factors and decision-making processes. The empirical findings offer strong support for the proposed conceptual model and provide insights into both the direct and indirect mechanisms through which ChatGPT operates.

The first key finding—that the use of ChatGPT has a significant positive effect on tourists’ travel decision-making—demonstrates the growing cognitive role of conversational AI in high-involvement choices. This aligns with Al-Romeedy and Singh [28], who highlight the overwhelming complexity travelers face when synthesizing fragmented online information. The present result strengthens this argument by showing that AI does not simply reduce information overload; it actively structures decision pathways, confirming McGeorge [47] observation that conversational systems decrease decision fatigue through real-time clarification. Additionally, Shalan [13] notes that ChatGPT enables travelers to navigate trade-offs more effectively than traditional search tools. The current findings extend this insight by revealing that the system’s adaptive dialogue fosters greater decisional certainty—indicating that ChatGPT functions as more than a passive information channel and increasingly resembles an interactive cognitive support mechanism.

The second major result showed that the use of ChatGPT significantly enhances users’ trust in AI-generated content. This outcome aligns with Alam et al. [86], who regard trust as the core determinant of whether users accept algorithmic suggestions, especially in experiential domains such as tourism. However, the present study provides deeper insight by confirming that trust develops not merely through exposure but through perceived conversational responsiveness and contextual relevance. Sridhar [50] argues that natural dialogue fosters an illusion of transparency, while Ghazali [87] explains that repeated coherent outputs strengthen credibility over time. The current results reinforce these claims but also indicate that trust becomes a decisive cognitive filter through which users validate recommendations before acting on them—an effect more pronounced in high-risk contexts involving financial and experiential consequences. Thus, trust appears to transform AI from a descriptive tool into a decision-enabling partner.

Regarding perceived usefulness, the results confirmed that interacting with ChatGPT significantly increases travelers’ perception of its value in improving planning efficiency. Patil et al. and Rihova and Alexander [88,89] argue that travelers increasingly seek tools that simplify complexity and convert scattered information into concise, actionable insights. The present study expands on these conclusions by demonstrating that usefulness is not merely recognized intellectually; it manifests behaviorally through increased reliance on the system during decision formation. Kontogianni et al. [19] notes that perceived usefulness enhances readiness to act, and the current findings provide empirical evidence for this effect within generative AI contexts. Importantly, usefulness appears to operate not just as a cognitive belief but as a motivational force that drives commitment to decisions, particularly in environments where time, clarity, and confidence are critical.

A similar pattern emerged in the finding that ChatGPT use significantly enhances perceived ease of use. This result speaks directly to the accessibility advantages of natural language interfaces. Algabri [2] argues that conversational systems eliminate traditional navigation barriers, while Sridhar [50] confirms that intuitive interactions increase the likelihood of deeper engagement. The present study adds nuance to these observations by showing that ease of use does not merely reduce effort; it lowers psychological resistance and encourages exploratory behavior. Wang et al. [3] found that ease of use promotes system familiarity, and the present findings reinforce this by demonstrating that tourists who perceive ChatGPT as effortless are more inclined to integrate it into complex planning tasks. Thus, ease of use becomes a cognitive enabler rather than a surface-level usability feature.

The results also showed that trust in AI-generated content has a significant positive effect on travel decision-making. Prior work by Shalan [13] suggests that trust is the psychological bridge that converts algorithmic suggestions into behavioral decisions. The present findings support this claim by showing that trust reduces hesitation and increases confidence in making choices that cannot be directly verified—such as destination suitability or itinerary feasibility. Farahat [10] emphasizes that trust is especially pivotal in tourism because travelers must often commit to decisions with financial or experiential risks. The current study extends this understanding by empirically illustrating that trust allows users to transition from passive information absorption to decisive action, highlighting its central behavioral role in human–AI interaction.

Similarly, perceived usefulness was found to positively influence travel decision-making. This aligns with Ferrer-Rosell et al. [36], who explain that users rely more heavily on systems they perceive as helpful in achieving their goals. The present findings contribute to this perspective by revealing that usefulness operates as a decision catalyst: when travelers perceive that ChatGPT improves clarity, reduces uncertainty, or streamlines complex comparisons, they are more inclined to act upon its suggestions. Solomovich and Abraham [34] highlights that usefulness often determines whether users accept or reject automated recommendations; the current study provides empirical support for this mechanism within generative AI contexts, further confirming that usefulness is a decisive predictor of action rather than merely a perception of benefit.

Perceived ease of use was also found to significantly predict travel decision-making. This finding builds upon the arguments of Li et al. and Qadeer et al. [24,90], who assert that systems requiring minimal cognitive effort are more likely to influence behavior, especially when decisions are time-sensitive. The present study extends these insights by demonstrating that ease of use enhances decisional momentum: when users can interact fluidly with AI, they become more willing to explore options, evaluate alternatives, and ultimately commit to choices. Kontogianni et al. [19] states that ease of use indirectly contributes to decision-making by shaping user confidence, and the current findings confirm this mechanism within conversational AI environments.

Finally, the study confirmed that each of the three perceptions—trust, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use—acts as a mediator between ChatGPT usage and travel decision-making. Rather than treating these perceptions collectively, the results show distinct pathways: trust converts system interaction into behavioral confidence, usefulness transforms interaction into perceived value, and ease of use transforms interaction into reduced cognitive burden. This layered structure aligns with the conceptualization of Shalan and Kontogianni et al. [13] and [19], who argue that AI influence is always mediated through subjective interpretation. The present findings reinforce this position by demonstrating that generative AI does not directly determine behavior; instead, decisions are shaped by how users cognitively interpret the interaction, which reflects a nuanced and psychologically grounded adoption process.

6. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the theoretical literature by developing a coherent conceptual framework that integrates the TAM with contemporary perspectives on AI-driven consumer decision behavior. While TAM has long served as a foundational model for explaining technology adoption, the rise in generative conversational AI introduces new cognitive and affective mechanisms that extend beyond classical assumptions [91]. By embedding TAM within the broader behavioral paradigm of how consumers process AI-generated information, this study offers a more comprehensive, psychologically grounded explanation of how travelers interpret and act upon conversational AI guidance.

First, the findings demonstrate that interacting with ChatGPT produces not only perceptual responses but also direct behavioral influence, showing that conversational AI can actively shape consumer evaluations and decisions [12]. This positions ChatGPT as a cognitive decision agent rather than merely a technological tool, expanding TAM beyond its traditional orientation toward intention formation [29,30]. In doing so, the study aligns TAM with contemporary theories of AI-assisted decision behavior, which view intelligent systems as participants in the cognitive process rather than passive interfaces.

Secondly, the results affirm that trust, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use co-evolve during AI interaction, supporting their integration into a unified conceptual model. Within the context of generative AI, trust emerges as a central evaluative mechanism—distinct from, yet interdependent with, usefulness and ease of use [28,92]. This supports theoretical arguments in consumer behavior research that decision-making in AI-rich environments depends on perceived credibility, emotional reassurance, and reduced uncertainty [93]. Accordingly, this study theoretically advances TAM by demonstrating that trust is not an auxiliary construct but a core mediator essential for understanding how consumers navigate AI-generated advice.

Third, by establishing that all three perceptual constructs significantly influence actual travel decision-making—not merely intentions—the study challenges the classical linearity of TAM and instead supports a multi-layered cognitive pathway consistent with behavioral decision theories. This finding aligns TAM with broader social science literature on AI-mediated judgment, which emphasizes that consumers increasingly outsource evaluation tasks to intelligent systems when cognitive effort is reduced, and trust is established [94].

Most importantly, the empirical confirmation that trust, usefulness, and ease of use mediate the relationship between ChatGPT usage and decision outcomes provides a theoretically integrated mechanism linking AI interaction to consumer behavior. This mediation structure demonstrates that users interpret AI responses through layered psychological filters, which collectively shape final choices [10]. The study therefore contributes a refined conceptual model that bridges TAM with emerging theories of AI persuasion, human–machine collaboration, and cognitive offloading in digital environments.

In sum, this research offers a theoretically strengthened and contextually relevant extension of TAM—one that is aligned with the realities of generative AI and consumer decision processes. By situating TAM within a broader conceptual framework of AI-enabled cognition, the study provides scholars with a rigorous, updated lens for understanding how travelers evaluate, trust, and ultimately act upon conversational AI in real-world decision-making scenarios.

7. Practical Implications

The findings of this study offer actionable direction for tourism stakeholders and AI developers seeking to strengthen the role of conversational AI in travel decision-making. Since trust emerged as the strongest mediator in the model, practical implications must move beyond general statements and focus on how AI systems can be deliberately engineered to enhance transparency, reliability, and user confidence.

To achieve this, AI developers should embed explicit transparency and explainability mechanisms into system design. This includes providing users with clear indications of how and why recommendations are generated. For example, itinerary suggestions could be accompanied by “reasoning cues” that summarize the underlying logic—such as seasonal factors, budget constraints, or similarity to prior user preferences. In addition, integrating “Why this recommendation?” explanation modules allows users to inspect the rationale behind AI outputs, turning opaque responses into interpretable guidance. Such features directly address trust-building, ensuring that users perceive content not as algorithmic guesses but as informed, accountable suggestions.

Developers can further enhance trust by incorporating source attribution and data-quality signals, such as referencing verified databases, indicating freshness of information, or displaying confidence levels associated with recommendations. These design choices align with industry expectations for responsible AI and strengthen the perceived credibility of generative outputs.

Beyond trust, the findings highlight the importance of engineering usefulness into system behavior. AI tools should be capable of contextual adaptation—interpreting trip duration, user constraints, cultural preferences, and risk tolerance to deliver timely and relevant recommendations. Implementing adaptive preference-learning frameworks supports this objective by refining outputs through continuous interaction rather than treating user input as static. Similarly, ease of use requires purposeful interface design. Features such as predictive query suggestions, seamless cross-device continuity, and interaction flows that reduce repetition can meaningfully lower cognitive load. A frictionless experience not only improves usability but reinforces the psychological comfort that underpins trust and intention to rely on AI during more complex decision processes.

Finally, the results also speak to policymakers and tourism organizations. Embedding cultural nuances, sustainability priorities, safety considerations, and destination-specific guidelines within AI systems can ensure that recommendations are not only accurate but also aligned with national tourism strategies. This transforms conversational AI from a general-purpose tool into a localized, strategic asset that supports visitor experience and sustainable tourism development.

8. Limitations and Future Research

While the current study provides valuable insights into how ChatGPT influences travel decision-making through perceived trust, usefulness, and ease of use, several limitations should be acknowledged, each offering opportunities for future research advancement. First, although this study relied on previously validated measurement scales and demonstrated strong post hoc reliability and validity indicators, a formal pilot study was not conducted prior to full-scale data collection. This methodological choice was justified given the use of established constructs and the robustness of the statistical validation procedures; however, the absence of a pilot study may limit early detection of context-specific wording ambiguities or item interpretation nuances. Future research should incorporate a pilot phase to further refine survey items, test contextual clarity, and enhance measurement sensitivity across different technological and cultural environments.

The sample was collected using non-probability convenience sampling, which, while appropriate for targeting tech-engaged users, may limit the generalizability of findings across different traveler types and demographic profiles. Given that the study intentionally focused on digitally active, tech-savvy users—who represent early adopters of AI-based travel tools—the findings primarily reflect the perceptions of this segment rather than the broader traveler population. Accordingly, the results should be interpreted as analytically generalizable to AI-engaged traveler segments rather than statistically generalizable to all travelers. This limitation aligns with the study’s scope but should be considered when interpreting the transferability of results. Future studies could apply quota or stratified sampling to include travelers with varying levels of digital literacy, thereby enabling comparisons between tech-savvy and non-tech-savvy users. Such efforts could help determine whether the strong relationships observed in this study extend to traveler groups that are less technologically engaged or culturally distinct. In addition, employing stratified or quota sampling across different cultural and demographic segments can enhance the generalizability of findings and allow future research to conduct more robust cross-cultural comparisons.

Moreover, this study did not explicitly examine the role of demographic variables as moderators. It is plausible that age, education level, or prior AI familiarity influences how users perceive usefulness, ease of use, or trust. Future models should explore these moderating effects to uncover segmented patterns of adoption and decision-making behavior, especially as AI becomes more prevalent across generations with differing digital expectations. Additionally, while the current model treated users as a homogeneous group, cultural context may play a crucial role in shaping how trust is built and how AI advice is interpreted. Future comparative studies across different cultural settings could assess whether cultural dimensions such as uncertainty avoidance, power distance, digital literacy, or collectivism influence the weight users assign to AI-generated content. Understanding these cultural dynamics is essential, particularly for global tourism platforms deploying AI in multilingual and multicultural environments. In addition, although the focus on ChatGPT provided a clear and current lens into generative AI use, future research should broaden the scope by comparing ChatGPT with alternative AI-based systems or hybrid human–AI travel advisors. Such comparisons would help determine the specific psychological, emotional, and decision-support advantages unique to conversational AI.

Furthermore, one important limitation of the current study lies in the way mediating variables—trust in AI-generated content, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use—were modeled as independent pathways without examining their potential interactions or causal sequencing. While each mediator demonstrated a significant individual effect, the underlying dynamics between them—such as whether trust precedes usefulness, or whether ease of use amplifies trust—were not explored. From a theoretical standpoint, prior TAM and AI adoption in the literature suggests that ease of use often acts as an antecedent that reduces cognitive effort and perceived risk, thereby fostering trust, which, in turn, strengthens perceived usefulness as users come to view reliable systems as more valuable for decision-making [29,30,95,96]. Although the present study did not empirically test this sequencing, acknowledging these theoretically grounded pathways provides a clearer rationale for how these mediators may influence each other in practice. In addition, treating these mediators as fixed perceptions within a cross-sectional design overlooks the evolving nature of users’ experiences with AI. Constructs such as trust, usefulness, and ease of use are not static qualities; rather, they develop and change over time as individuals repeatedly interact with an AI system and receive feedback. A longitudinal research design would therefore provide deeper insight into how these perceptions mature, stabilize, or shift across different phases of user engagement. Longitudinal or time-lagged designs could capture the evolution of these constructs and identify when in the user journey each mediator exerts the most influence. Understanding the temporal and structural relationships among mediators would contribute to a more refined and psychologically grounded framework for AI adoption in tourism, ultimately enhancing the theoretical utility of TAM and its extensions in dynamic, trust-sensitive contexts.

Finally, because different versions of ChatGPT (e.g., free and paid models) coexisted during the data collection period, participants may have interacted with varying system variants. The study did not differentiate between these versions, as its analytical focus centers on users’ perceptions rather than model-specific performance. Nonetheless, acknowledging this contextual variability is important, and future research should examine whether model differences influence trust, adoption intentions, or perceived reliability among diverse traveler segments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S.A.-R. and T.A.; methodology, B.S.A.-R. and T.A.; software, B.S.A.-R.; validation, B.S.A.-R.; formal analysis, B.S.A.-R. and T.A.; investigation, B.S.A.-R. and T.A.; resources, B.S.A.-R. and T.A.; data curation, B.S.A.-R. and T.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.S.A.-R. and T.A.; writing—review and editing, B.S.A.-R. and T.A.; visualization, B.S.A.-R. and T.A.; supervision, T.A.; project administration, T.A.; funding acquisition, T.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, under grant no. (IPP: 510-209-2025). The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thank DSR for technical and financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Tourism and Hotels, University of Sadat City (10 November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from researchers who meet the eligibility criteria. Kindly contact the first author privately via e-mail.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used QuillBot and Grammarly for the purposes of language proofreading and stylistic editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Constructs | Mean | SD |

| ChatGPT | 3.57 | 0.66 |

| I feel that it is important to use ChatGPT when searching for hospitality/tourism information | 3.55 | 0.75 |

| I usually turn to ChatGPT whenever I need information or clarification about hospitality or tourism topics | 3.59 | 0.72 |

| I depend on ChatGPT as a main tool when conducting searches related to hospitality and tourism | 3.66 | 0.69 |

| I regularly use ChatGPT when searching for hospitality and tourism-related information | 3.47 | 0.63 |

| Trust in AI-generated content | 3.45 | 0.72 |

| ChatGPT’s response and advice can meet my expectations | 3.44 | 0.70 |

| ChatGPT is honest and truthful | 3.40 | 0.73 |

| ChatGPT is capable of addressing my issues | 3.51 | 0.80 |

| I trust the suggestions and decisions provided by ChatGPT | 3.47 | 0.71 |

| Perceived usefulness | 3.70 | 0.64 |

| I feel that ChatGPT is competent | 3.65 | 0.63 |

| I feel that ChatGPT is clever | 3.77 | 0.69 |

| I feel that ChatGPT is intelligent | 3.67 | 0.66 |

| Perceived ease of use | 3.93 | 0.72 |

| ChatGPT is easily accessible | 3.87 | 0.80 |

| ChatGPT is easily available to use | 3.98 | 0.71 |

| Travel decision-making | 3.95 | 0.69 |

| I make travel decisions based on careful evaluation of available options | 3.88 | 0.70 |

| I feel confident in the travel choices I make | 3.96 | 0.77 |

| The information I review helps me finalize my travel plans | 4.00 | 0.73 |

References

- Saini, H.; Kumar, P.; Verma, R. Social Media and Its Influence on Travel Decision Making. In Decoding Tourist Behavior in the Digital Era: Insights for Effective Marketing; Azman, N., Valeri, M., Albattat, A., Singh, A., Eds.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algabri, H. Artificial Intelligence and ChatGPT; Academic Guru Publishing House: Bhopal, India, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Miao, H.; Xiong, M.; Wang, Y. How does ChatGPT-generated information influence travel planning? The mediating role of inspiration. Tour. Rev. 2025. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P. A deep introspection into the role of ChatGPT for transforming hospitality, leisure, sport, and tourism education. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2024, 35, 100504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, G.; Chamola, V.; Hussain, A.; Guizani, M.; Niyato, D. Transforming conversations with AI—A comprehensive study of ChatGPT. Cogn. Comput. 2024, 16, 2487–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiou, D.; Nella, A. ChatGPT and Tourist Decision-Making: An Accessibility–Diagnosticity Theory Perspective. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.; Lian, Q.; Sun, D. Autonomous travel decision-making: An early glimpse into ChatGPT and generative AI. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 56, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, M.; Baek, T. Enhancing user experience with a generative AI chatbot. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kang, S.; Hall, C.; Kim, J.; Promsivapallop, P. Unveiling the impact of ChatGPT on travel consumer behaviour: Exploring trust, attribute, and sustainable-tourism action. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 28, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahat, E. Applications of Artificial Intelligence as a Marketing Tool and Their Impact on the Competitiveness of the Egyptian Tourist Destination. Doctoral Dissertation, Minia University, Minya, Egypt, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Foroughi, B.; Iranmanesh, M.; Yadegaridehkordi, E.; Wen, J.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Senali, M.; Annamalai, N. Factors Affecting the Use of ChatGPT for Obtaining Shopping Information. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2025, 49, e70008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Hailu, T. Effects of AI ChatGPT on travelers’ travel decision-making. Tour. Rev. 2024, 79, 1038–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalan, I. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Improving Tourism Service Quality in The Egyptian Destination. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Sadat City, Sadat City, Egypt, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ishengoma, F. Revisiting the TAM: Adapting the model to advanced technologies and evolving user behaviours. Electron. Libr. 2024, 42, 1055–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]