Abstract

Exemplified by EcoStruxure from Schneider and CASICloud, production-capacity-sharing platforms typically operate as two-sided platforms. These platforms contribute to carbon emission reductions while generating revenue through uniform membership fees, fixed service charges, or commission fees applied to one or both sides of the platform. As B2B platforms, however, they must determine whether to offer online payment options to participants on both sides of the market. We employ the theory of two-sided markets and the method of comparative analysis, developing a two-sided market model to investigate: (1) the platform’s optimal payment method selection strategies and (2) how same-side network externalities and user online search costs affect platform performance. We examine two payment modes: M mode (offline payments only) and F mode (combined offline/online payments). The F mode comprises two sub-modes—FF (two-sided users choose to pay offline) and FN (two-sided users choose to pay online)—determined by users’ payment preferences on each side. We conduct pairwise comparisons of the platform’s membership fee, fixed service fee, and online service level between: (i) FF and M modes and (ii) FN and M modes. Our results indicate that the optimal payment method selection varies across market conditions, with each mode demonstrating superior performance under specific market characteristics. The FF mode consistently yields higher profits compared to the M mode. When suppliers’ expected revenues fall below a certain threshold, the FN mode outperforms the M mode in terms of profit generation. Conversely, the M mode becomes preferable above this threshold. Furthermore, the effects of same-side network externalities and search costs vary significantly across different payment modes. Under the M mode and the FF1 mode, the effects of the same-side network externality on the platform’s membership fee are associated with two-sided users’ online search costs, which are more monotonous. Under the FN1 and FN2 modes, both the same-side network externality and two-sided users’ online search costs impact the platform’s optimal strategies monotonously, but they are not always the same in these two modes.

1. Introduction

Production capacity sharing has become more and more important in the manufacturing industry with the development of cloud manufacturing, 5G networks, and industrial IoT technologies [1]. As documented in the State Information Center’s (2023) Sharing Economy Report [2], the sector’s transaction volume is dominated by life services (48.4%), production capacity sharing (32.75%), and knowledge/skills platforms (12.54%). The report shows that the market size of production capacity sharing keeps growing at a rate of 1.5%, and the market share of production capacity sharing has kept up rapid development in these years compared to others. As a result, production-capacity-sharing platforms, such as EcoStruxure from Schneider and CASICloud, have attracted great attention due to the continuous growth of their transaction volume. Distinct from traditional capacity services, production-capacity-sharing platforms address three critical challenges: (1) mitigating manufacturers’ capacity imbalances [3], (2) enhancing supply chain resilience following disruption [4], and (3) reducing production-phase carbon emissions [5]. However, unlike many other sharing platforms, research on production-capacity-sharing platforms, such as the effects of network externalities and two-sided users’ online search costs on these platforms, is not detailed enough.

Case evidence from production-capacity-sharing platforms—including CASICloud and iSESOL—reveals divergent outcomes in payment system implementation: whereas iSESOL’s single-payment-option (online payment) approach failed, CASICloud’s multi-payment system (online payment and offline payment) succeeded. The reasons for the success of CASICloud mainly include the following points: (1) offering value-added online services for two-sided users, (2) establishing binding transaction contracts, and (3) ensuring timely payment processing. Notably, the suppliers (one of the two-sided users) prefer to pay the platform an extra fee for choosing online payment to utilize the platform’s online services, ensuring that they receive the total payment on time or some other beneficial services. As for the production-capacity-sharing platform, it could charge two-sided users more and earn extra revenue from the demander’s payment held in the platform when two-sided users choose online payment. Hence, the key to a production-capacity-sharing platform is to find a suitable payment method for two-sided users to maximize the platform’s profits.

Production-capacity-sharing platforms exhibit broad development prospects. Numerous scholars have investigated various aspects of production-capacity-sharing platforms. First, scholars have examined production-capacity-sharing phenomena among manufacturers [6,7], both with and without platform intermediation. Their findings demonstrate that production capacity sharing effectively resolves supply–demand mismatches and propose operational models for production-capacity-sharing platforms. However, the above studies neglect to incorporate platform network externalities. Second, researchers have investigated contractual arrangements in production capacity sharing [8,9]. However, most studies overlook the platform’s intermediary role and two-sided users’ dynamics, failing to account for platform profitability. Moreover, in the practice of the production-capacity-sharing platform, same-side network externalities are more obvious, because the synergy and positive effects of the same-side network externality make the platform attract more two-sided users, which is one of the key points to more effectively operate the platform. While cross-side network externality is more complicated and always performs differently between two-sided users, it is more difficult to quantify in the model. As a result, this study investigates the production-capacity-sharing platform’s optimal payment method for two-sided users by incorporating same-side network externalities and two-sided users’ online search costs. Furthermore, we analyze the distinct effects of same-side network externalities and two-sided users’ online search costs on platform performance. This research contributes novel insights for production-capacity-sharing platforms by addressing two critical questions:

(1) What constitutes the optimal payment method strategies for two-sided users of production-capacity-sharing platforms, particularly regarding the provision of online payment options?

(2) How do same-side network externalities and users’ online search costs influence these optimal strategies?

To address these research questions, we develop two-sided market models that incorporate the platform’s same-side network externalities and users’ online search costs. We examine two payment method strategies for production-capacity-sharing platforms: (1) M mode: exclusive offline payment options; (2) F mode: combined offline and online payment options. The M mode serves as our benchmark scenario, where the platform offers no additional online services and charges both user groups an identical membership fee. Subsequently, we analyze scenarios where the platform offers both payment options, and users self-select between offline and online payment methods. Under FF mode, when users select offline payments, the platform always imposes a uniform membership fee. In FN mode, online payment adopters benefit from platform-mediated funding security services, while the platform maintains the membership fee and additionally charges suppliers a fixed service fee. We conduct pairwise comparisons between FF mode and M mode and between FN mode and M mode. Furthermore, we separately analyze the effects of same-side network externalities and online search costs on the platform’s optimal strategies.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the extant literature on production-capacity-sharing platforms and two-sided markets. We then present our models in Section 3. In Section 4, we analyze the production-capacity-sharing platform’s optimal payment mode selection strategies, compare their performance implications, and investigate the effects of network externalities and online search costs. Section 5 concludes with managerial implications and proposes directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

Production-capacity-sharing has gained significant traction in recent years as a core component of the sharing economy. However, systematic academic research on this emerging phenomenon remains limited. A growing stream of literature has investigated the critical role of platform network externalities. For example, Katz and Shapiro (1985) examined the effects of network externalities (including the same-side network externality and the cross-side network externality) on the markets and indicated that the network externalities are closely associated with the demand economies of scale [10]. Rochet and Tirole (2003) examined the presence of the same-side network externalities and the platform’s pricing models [11]. More recently, Dou and Wu (2021) demonstrated how platforms can leverage pricing mechanisms to activate cross-side network effects [12]. Additional studies have applied network externality theory to elucidate the role of standardization and switching costs in network economies [10,13,14]. Anderson et al. (2014) examined performance investment strategies in two-sided platforms, with a particular emphasis on cross-side network externality effects [15]. Wu and Chamnisampan (2021) systematically analyzed how cross-side network externalities affect platform pricing and platform tactics [16]. Notably, the specific effects of same-side network externalities on production-capacity-sharing platforms’ payment mode selection for two-sided users remain underexplored in the existing literature. Furthermore, the abovementioned research mainly studied the relationship between the cross-side network externalities and the platform’s pricing strategies. Compared to the previous research, this study focuses on the same-side network externalities and studies how the production-capacity-sharing platform should react to make better payment method selections according to their fluctuations.

Our study also involves the recent literature examining how manufacturing enterprises share their idle capacity with or without a platform. In terms of the popularity of production capacity sharing, Li et al. (2017) showed that the emergence of the Internet of Things and artificial intelligence technologies has brought tremendous changes to the manufacturing industry and promoted the development of production-capacity-sharing models [17]. Qin et al. (2020) established production capacity sharing as an effective mechanism for addressing supply–demand mismatches in manufacturing ecosystems [6]. Zhao et al. (2020) comparatively analyzed platform pricing strategies, examining how product lifecycle fluctuations and demand uncertainty propagate through supply chain decision-making [7]. A parallel research stream focuses on capacity allocation mechanisms [18]. Chen et al. (2020) developed a supply chain model demonstrating that regulated capacity controls can enhance social welfare [19]. Dai and Nu (2020) derived equilibrium pricing models for capacity-constrained manufacturers across various sharing scenarios [20]. Their analysis further revealed how capacity constraints shape sharing modality selection and equilibrium outcomes. In a differentiated duopoly setting, Chen et al. (2020) quantified the impacts of three production-capacity-sharing regimes on profits, consumer surplus, and social welfare [21]. Furthermore, they identified critical implementation thresholds and empirically validated the moderating role of product differentiation. Complementary research has investigated non-platform-based production-capacity-sharing contracts. For instance, Argoneto and Renna (2011, 2016) proposed a coordination mechanism for production-capacity-sharing between two independent factories [22,23]. Aloui and Jebsi (2016) established platform governance frameworks showing inverse proportionality between expected participation levels and allocated capacity shares [24]. Guo and Wu (2018) rigorously compared ex-ante versus ex-post contracting strategies, identifying optimal profit-maximizing approaches for dyadic capacity sharing [8]. Fang and Wang (2020) analyzed strategic interactions under distinct contractual frameworks: linear transfer payments versus revenue-sharing agreements [9]. The abovementioned studies concentrate on how to solve the mismatches between supply and demand and provide capacity allocation strategies for the manufacturers without a production-capacity-sharing platform, but they ignore the role of the production-capacity-sharing platform. Distinct from prior work, our study emphasizes the role of the production-capacity-sharing platform and advances platform-centric payment method selection strategy formulation in production-capacity-sharing ecosystems.

This study contributes to the growing body of research on platform economics and operational strategy formulation [11,25,26,27,28,29], with particular relevance to recent advancements in industrial platform contexts [30,31,32,33]. For example, Armstrong (2006) systematically compared platform pricing strategies across three market structures: (i) monopoly platforms, (ii) competing platforms with single-homing agents, and (iii) competing platforms with multi-homing agents [27]. Cennamo and Santalo (2013) identified two critical strategic trade-offs in platform ecosystems: between innovation stimulation and consumer preference management, both being determinants of platform scalability and profitability [34]. Kung and Zhong (2017) took network externalities into consideration and examined a two-sided platform’s three different pricing strategies: membership-based pricing, transaction-based pricing, and cross-subsidization [35]. Their model provides an optimal profit-maximization framework for two-sided platforms. Adner et al. (2020) analyzed platform strategy formulation under compatibility constraints, quantifying its profit implications [36]. Tan et al. (2020) examined two-sided platforms’ pricing strategies when the platform invests in integration tools [37]. Dou and Wu (2021) studied the platform’s subsidization strategy under the effect of piggybacking [12]. The abovementioned studies mainly examined the pricing strategies and subsidization strategies of the sharing platforms, and the sharing platforms in these studies were usually not production-capacity-sharing platforms. Moreover, these studies ignore the payment method for two-sided users, and some of them do not consider the effects of same-side network externalities and online search costs. Our work makes distinctive theoretical departures from prior research by proposing non-subsidized operational modes that fundamentally reconfigure platform–user economic relationships.

This study is also related to the literature on two-sided users’ online search costs. Many studies indicate that a decrease in consumer search costs will decrease retail prices [38,39,40,41]. Some other works also indicate that the Internet has lowered consumers’ search costs and, hence, hurt the sellers’ profit [42,43,44]. Other studies show that online retailing lowers customers’ search costs [45,46,47]. Cachon et al. (2008) demonstrated that search cost reduction generates dual effects: intensifying price competition while simultaneously expanding market reach [48]. Our findings resonate with this dual-effect paradigm. Recent theoretical advances have formalized the search cost-utility tradeoff [49,50]. Dukes and Liu (2016) derived optimal search mechanism designs that balance product discoverability with cost containment [51]. Jiang and Zou (2020) quantified how search cost elasticity impacts platform profit maximization and fee structure optimization [52]. Wu and Chamnisampan (2021) modeled platform-mediated search costs as endogenous service fees that influence user participation decisions [16]. Gu and Wang (2022) decomposed search costs into cognitive and temporal dimensions, empirically validating their differential impacts on platform revenue streams [53].

The abovementioned studies mainly discuss the online search costs based on e-commerce platforms. Although some of them conducted studies in the context of sharing platforms, they are not related to two-sided users in production-capacity-sharing platforms. Departing from prior research, we establish a novel framework for analyzing bilateral search cost dynamics in production-capacity-sharing platforms, and we systematically study the effects of the same-side network externalities and two-sided users’ online search costs on the selection of the production-capacity-sharing platform’s payment method selection strategies. Furthermore, we advance the sharing economy literature by developing a typology of two-sided users’ payment method strategies with distinct network externality profiles, as well as revealing previously undocumented same-side externality mechanisms through comparative analysis.

3. Model

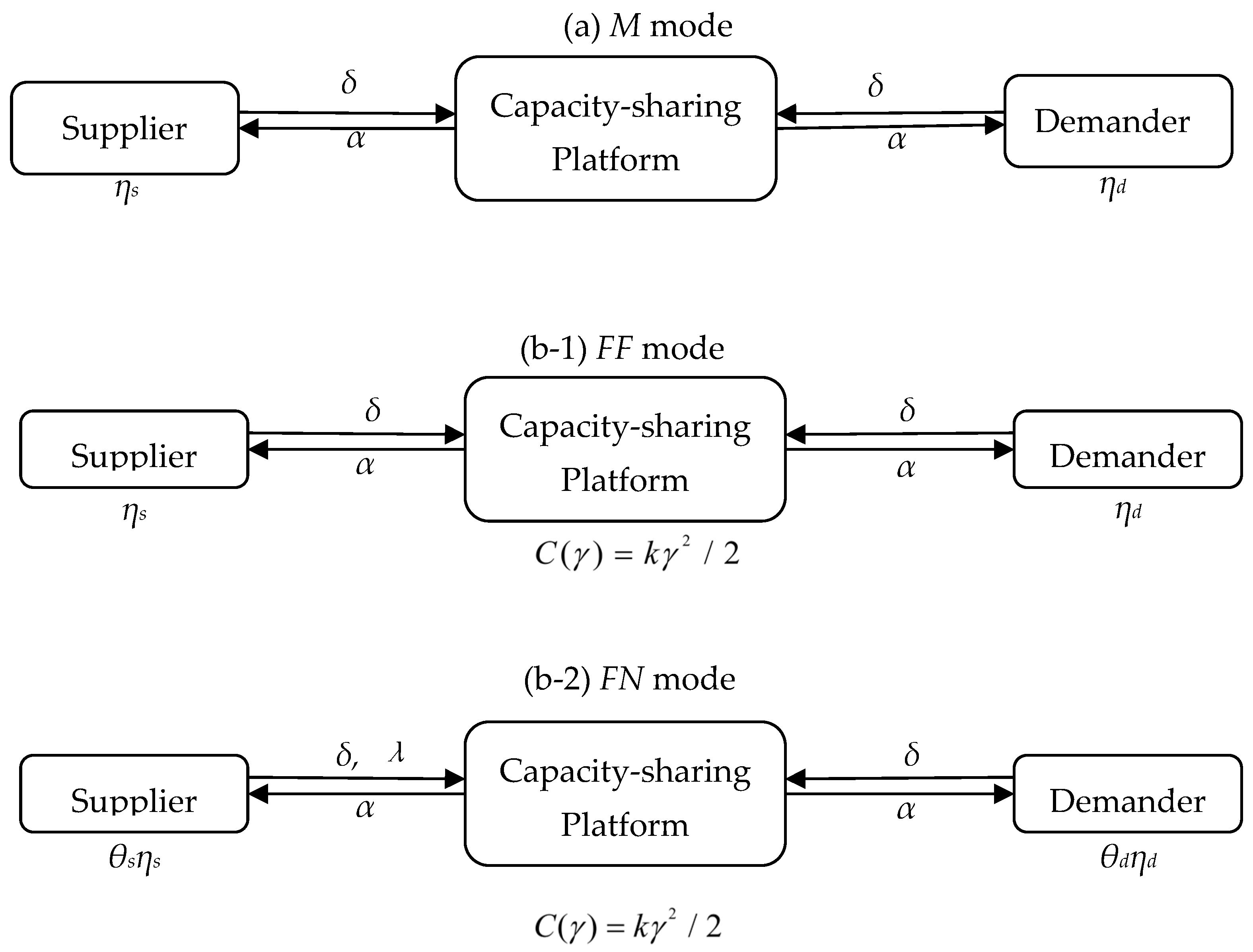

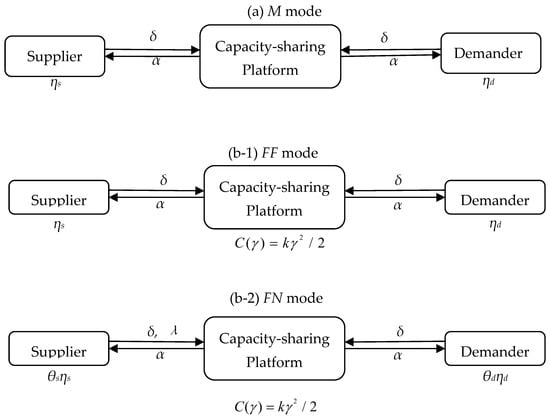

We developed a two-sided market model where capacity suppliers and capacity demanders share capacity via a production-capacity-sharing platform (platform). Two-sided users need to pay the platform for making transactions on the platform and utilizing the platform’s various services. The platform has two payment modes for two-sided users: One is the M mode, where the platform only provides offline payment. Under the M mode, the platform only charges two-sided users the same membership fee δ (δ > 0) for a certain period, e.g., a year, no matter how many transactions they have made on the platform. The M mode is the benchmark, where the platform charges two-sided users the same membership fee for better financial and operational management. The second mode is the F mode, where the platform provides both offline and online payment methods. Here, two-sided users have the right to decide their payment method, and only when two-sided users choose the same payment method simultaneously will they make transactions with one another successfully. Thus, the F mode has two sub-modes, which are decided by two-sided users’ payment choices: One is the FF mode, where two-sided users choose to pay offline, and the platform still only charges two-sided users the membership fee δ. The other is the FN mode, where two-sided users choose to pay online, and the platform charges two-sided users the same membership fee δ and the suppliers a fixed service fee λ (λ > 0) per transaction. Figure 1 illustrates these two payment modes.

Figure 1.

Two payment modes. (a) M mode: only provide offline payment; (b-1) FF mode: two-sided users choose to pay offline; (b-2) FN mode: two-sided users choose to pay online.

When two-sided users successfully make transactions with one another, each supplier can obtain an expected revenue () from all of their transactions, and each demander can obtain an expected revenue () from the consumers. We assume that both the demanders and the suppliers seek positive profits. As a result, we can determine that . Furthermore, two-sided users can obtain the benefits brought by the platform’s network externalities. In this paper, we only consider the same-side network externality α (0 < α < 1), and we assume that both two-sided users utilize the identical same-side network externality [54], because the platform can weaken or enhance the same-side effect on one side to make it tend towards balance through product design.

The platform’s evaluation features allow two-sided users to rate and remark on each transaction they have completed there. These remarks and comments represent two-sided users’ rates of satisfaction with the platform’s sharing capacity. Let () denote a supplier’s or a demander’s rate of satisfaction with the potential transaction on the platform. Each two-sided user incurs a positive online search cost when they search for potential trading on the platform. The online search cost is due to various factors of online transactions, including having to spend time talking with potential suppliers or demanders and waiting for product delivery, or worries about online transaction security and privacy [16,55]. Furthermore, two-sided users differ in their attitudes toward online transactions on the platform and in their willingness to wait for the supplier’s capacity delivery or the payment from the demander [56]. Let () denote a two-sided user’s online search cost, with an average online search cost of across all two-sided users [55]. Note that our model incorporates heterogeneity among two-sided users according to their relative online search costs for choosing different payment methods. This difference in the relative online search costs between two-sided users influences their choices of payment methods and enables us to thoroughly study various payment method selection strategies of the platform.

Note that under the FF mode and the FN mode, the platform provides an online funding security service (online service) for two-sided users, which they cannot obtain when paying offline. To better service two-sided users, the platform will invest in its online service level γ (0 ≤ γ ≤ 1) with a cost of . Here, k () is the platform’s investment efficiency for online service. We assume that the platform is completely rational and aims to maximize profit. The notations are as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of notations.

3.1. Two-Sided Users’ Utilities

Two-sided users can obtain utilities when they join the platform, and they receive different utilities under the platform’s three different payment modes. Under the M mode, a demander’s expected revenue Rd is their basic utility, and the demander can obtain the utility αnd that is brought by the same-side network externality. Meanwhile, the demander needs to pay the platform a membership fee δ and has an online search cost ηd [16]. Similarly, a supplier’s utility under the M mode consists of their basic utility Rs and αns minus the platform’s membership fee δ and their online search cost ηs. Thus, the demander’s utility function and the supplier’s utility function under the M mode are as follows:

Under the FF mode, a supplier’s utility is the same as . Because the supplier cannot utilize the platform’s online service, the supplier obtains no extra value in this situation, but the demander can obtain an extra utility ε, because the demander has more flexibility in payments to the supplier. Moreover, paying offline means that there will be no commission charged by the platform, and this gives the demander stronger bargaining power. Here, () is the demander’s extra utility from paying offline. Thus, the demander’s utility function and the supplier’s utility function under the FF mode are as follows:

Under the FN mode, two-sided users will pay online. As a result, two-sided users can utilize the platform’s online service. Furthermore, the supplier’s perception of the platform’s online service is greater than that of the demander, because when two-sided users choose to pay online, the demander must put the payment into the platform’s account before receiving the capacity from the supplier. The platform would deposit part of the payment into the supplier’s account at once when the demander confirms the capacity and sends a signal to the platform.

For instance, when a supplier and a demander on CASICloud successfully search for one another to make a transaction and make an agreement to use online payment methods, they need to sign a contract that is regulated by the platform, and the demander needs to put the contract payment into the platform first. Then, the supplier delivers the capacity to the demander. The platform will put part of the contract payment (the contract payment minus the supplier’s commission charge) into the supplier’s account after the demander has examined the capacity. Similarly, if the demander finds that the supplier’s capacity does not meet pre-agreed norms, the demander can communicate with the platform, and the platform will give the demander their refund. According to the above example, although both two-sided users utilize the platform’s online service, the FN mode is more beneficial to the supplier because the supplier has higher financial security insurance under the FN mode than the other two modes. As for the demander, their flexibility in cash flow under the FN mode is less than that under the other two modes, while the demander utilizes the platform’s online service at the same time.

Here, a supplier can obtain an extra utility βsγ for utilizing the platform’s online service, and βs (0 ≤ βs ≤ 1) is the supplier’s perception coefficient of the platform’s online service level. A demander can obtain an extra utility βdγ for utilizing the platform’s online service, and βd (0 ≤ βd ≤ 1) is the demander’s perception coefficient of the platform’s online service level. Note that the supplier’s perception of the platform’s online service level is higher than that of the demander (βs > βd). Furthermore, two-sided users’ online search costs under the FN mode are lower than those under the FF mode. This is because when the platform provides an online service, it also provides other related online services. For instance, when two-sided users choose to pay online, they can add this payment condition to their search criteria and then obtain more specific search results, and such a search is less time-consuming compared to other modes. As a result, two-sided users’ online search costs are (i = s, d), where θi is the user i’s rate of satisfaction with the potential transactions on the platform. We make θiηi represent two-sided users’ online search costs under the FN mode, because it means that two-sided users will have better experiences when they have a higher satisfaction rate, which reduces their online search costs. Obviously, θiηi < ηi, so θiηi can represent two-sided users’ online search costs under the FN mode. The supplier needs to pay the platform λnd to utilize the platform’s online service. Here, we assume that a supplier will make one transaction with all potential demanders, so a supplier’s total service fee is λnd. Then, the demander’s utility function and the supplier’s utility function under the FN mode are as follows:

3.2. Production-Capacity-Sharing Platform’s Profit

The production-capacity-sharing platform has different profits under these different payment modes. Under the M mode, the only source of the platform’s profit is two-sided users’ membership fees. Under the FF mode, the platform’s profit is two-sided users’ membership fees minus the platform’s investment kγ2/2 (0 < k < 1) in the platform’s online service. Under the FN mode, the platform’s profit is that of the FF mode and the supplier’s fixed service fee from potential transactions on the platform. Note that the platform’s profit is from all suppliers’ potential transactions on the platform. We assume that ndns represents the total number of potential transactions on the platform [57]; i.e., each supplier will make one transaction with each demander. This assumption, with ndns as the upper limit of the platform’s transaction scale, demonstrates the exponential growth of two-sided users’ scales. If we restrict this matching assumption, it would weaken the essence of the same-side network externalities and influence the results. We can formulate the platform’s profit under the three different payment modes as follows:

The platform maximizes its profit by deciding its decision variables under three payment modes. We focus on the platform’s positive maximal solutions.

4. Analysis

In this section, we first derive two-sided users’ numbers and the best options for the platform under each of these payment modes. We then examine the effects of three different payment modes by comparing the optimal solutions of two sub-modes of the F mode with those of the M mode. Finally, we examine how the platform’s same-side network externality and two-sided users’ online search costs affect the platform’s optimal solutions.

4.1. Production-Capacity-Sharing Platform’s Optimal Solutions

The optimal solutions of the production-capacity-sharing platform depend critically on the number of two-sided users. In the benchmark, we can derive two-sided users’ numbers easily. In the F mode, we need to compare the user i’s utilities of the two sub-modes, and then we can derive the numbers of two-sided users of these two modes under different conditions.

4.1.1. M Mode

In the M mode, we can derive two-sided users’ numbers according to and . Then, the numbers of two-sided users are as follows:

We put and into , and we maximize the platform’s profit:

Based on the platform’s first-order and second-order derivative conditions, we can derive that the platform has the maximum profit when , and . These three constraints reflect the relationship between the same-side network externality and two-sided users’ online search costs. The platform does not need to maintain a very high level of same-side network externality when two-sided users’ online search costs are high, because when those costs are high, the switch cost for the users to transfer to another platform is high. It would be more cost-effective for them to stay on the original platform. The platform’s optimal solutions are as follows.

Lemma 1.

Under the M mode, the production-capacity-sharing platform charges two-sided users the same membership fee , and its optimal profit is , where

Then, we can derive two-sided users’ numbers under the M mode as shown in Equation (13) by putting into Equation (10).

4.1.2. F Mode

In the F mode, two-sided users’ numbers are not fixed. We need to compare two-sided users’ utilities under two sub-modes of the F mode and then derive the number of two-sided users under each mode. According to , , , , and , we can derive the numbers of two-sided users under the FF mode and the FN mode:

(I) FF mode

According to Equations (14) and (15), we need to calculate the platform’s optimal solutions under different combinations of two-sided users’ numbers under the FF mode. Note that the platform can only make a profit when both two-sided users’ numbers are positive. Thus, the combinations of (14-a) and (16-c), (14-b) and (16-c), (14-c) and (15-a), (14-c) and (16-b), and (14-c) and (16-c) are ineffective. Under the FF mode, we only need to calculate four combinations: (14-a) and (15-a), (14-a) and (16-b), (14-b) and (15-a), and (14-b) and (16-b). We use the subscripts 1, 2, 3, and 4 to distinguish these four combinations under the FF mode, i.e., FF1, FF2, FF3, and FF4. According to our calculations, we derive that only the FF1 mode is available. This is mainly because the platform’s online security service level should be zero in the FF mode for two-sided users who are still choosing to pay offline. The platform does not need to make efforts with respect to the online security service level. However, the platform’s optimal online security service level under the FF2, FF3, and FF4 modes is not zero, according to the calculations. This demonstrates that the platform will incur additional costs, but it will not obtain increased profit from this investment. Thus, we only list the results of the FF1 mode here. The calculations of the other three combinations can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

By solving the FF1 mode, we derive two-sided users’ numbers and :

Then, we put and into , and we maximize the platform’s profit:

Based on the platform’s first-order and second-order derivative conditions, we can derive that the platform has the maximum profit when 0 < α < and 0 < α < . The platform’s optimal solutions are as follows:

Lemma 2.

Under the FF1mode, the production-capacity-sharing platform charges two-sided users the same membership fee , the platform’s optimal online service level is , and its optimal profit is , where

Here, the platform’s online service level because two-sided users will not utilize the platform’s online service under the FF1 mode. As a result, the platform does not need to make efforts with respect to its online service. This is consistent with our intuition.

Then, we can derive two-sided users’ numbers under the FF1 mode as shown in Equation (20) by putting into Equation (18).

(II) FN mode

According to Equations (14)–(17), we need to calculate the platform’s optimal solutions under different combinations of two-sided users’ numbers under the FN mode. Similarly to the FN mode, a transaction can only happen when both two-sided users’ numbers are positive. Thus, the combinations of (15-a) and (17-a), (15-a) and (17-b), (15-a) and (17-c), (15-b) and (17-a), and (15-c) and (17-a) are ineffective. We only need to calculate four combinations: (15-b) and (17-b), (15-c) and (17-c), (15-b) and (17-c), and (15-c) and (17-b). Similarly to the FN mode, we use FN1, FN2, FN3, and FN4 as the four sub-modes of the FN mode. According to our calculations, the FN3 and FN4 modes are ineffective (the detailed proof can be found in the Supplementary Materials). The calculations for the other two combinations are as follows.

(i) FN1 mode

By solving Equations (15-b) and (17-b), we can derive the two-sided users’ numbers and :

Then, we put and into , and we maximize the platform’s profit:

Based on the platform’s first-order and second-order derivative conditions, we can derive that the platform has the maximum profit when , and . The following are the platform’s optimal solutions:

Lemma 3.

Under the FN1mode, the production-capacity-sharing platform charges two-sided users a same membership fee and the suppliers a fixed service fee , the platform’s optimal online service level is , and its optimal profit is , where

Here, , , , , , , , , , , , and .

Then, we can derive two-sided users’ numbers under the FN1 mode as shown in Equation (23) by putting , , and into Equation (21):

(ii) FN2 mode

By solving Equations (15-c) and (17-c), we can derive the two-sided users’ numbers and :

Then, we put and into the platform’s profit function, and we maximize the platform’s profit:

Based on the platform’s first-order and second-order derivative conditions, we can derive that the platform has the maximum profit when , and . The following are the platform’s optimal solutions:

Lemma 4.

Under the FN2mode, the production-capacity-sharing platform charges two-sided users a same membership fee and the suppliers a fixed service fee , the platform’s optimal online service level is , and its optimal profit is , where

Then, we can derive the two-sided users’ numbers under the FN2 mode as shown in Equation (26), by putting , and into Equation (24).

4.2. The Comparison of the Three Modes

Given the diverse payment modes of the production-capacity-sharing platform, we are interested in the following important question: Should the platform offer two-sided users online payment methods? This question is particularly interesting based on the findings of the following section, comparing two sub-modes of the F mode with the M mode.

4.2.1. The Comparison of the FF1 Mode with the M Mode

First, we compare the platform profit under the FF mode and the M mode.

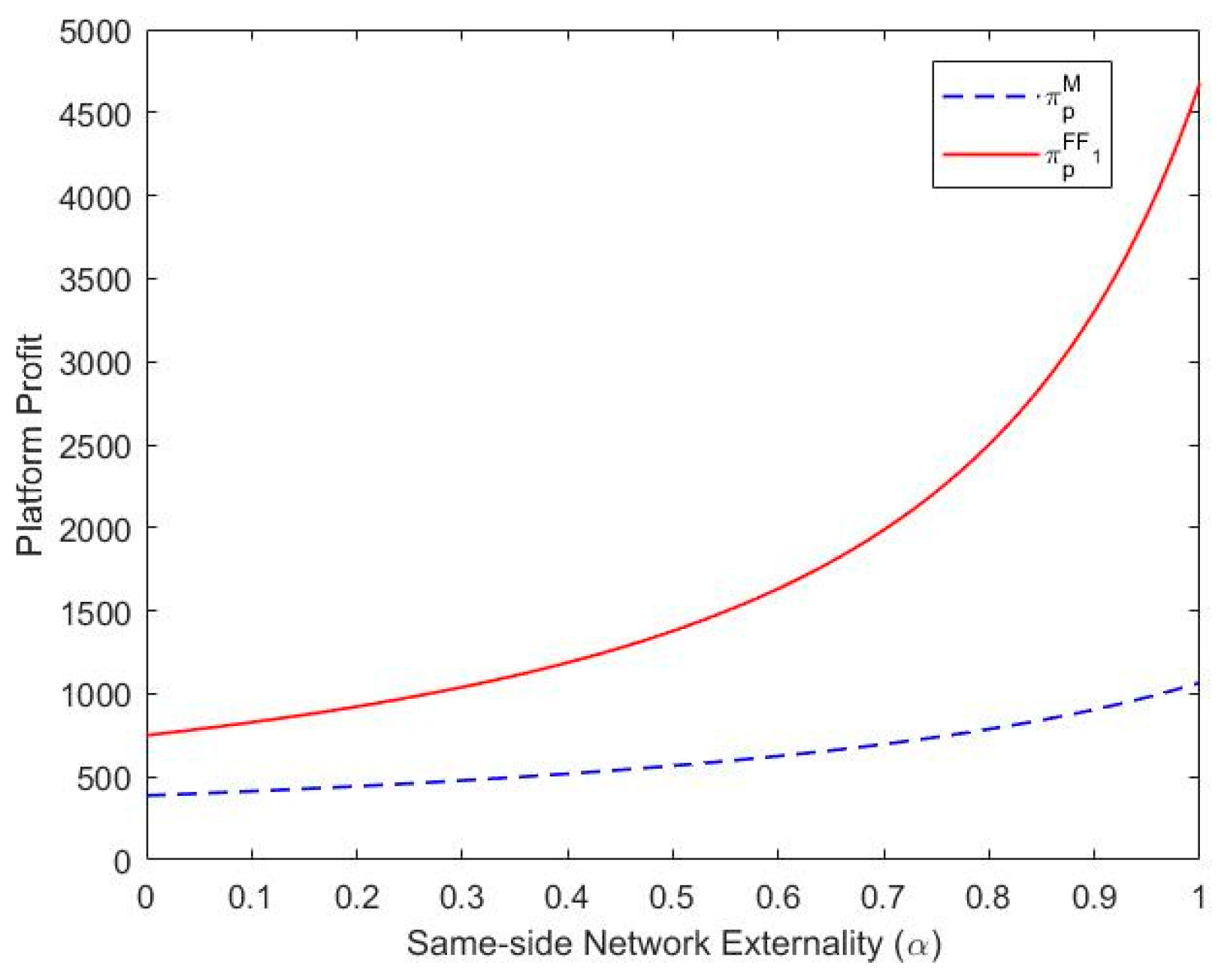

Theorem 1.

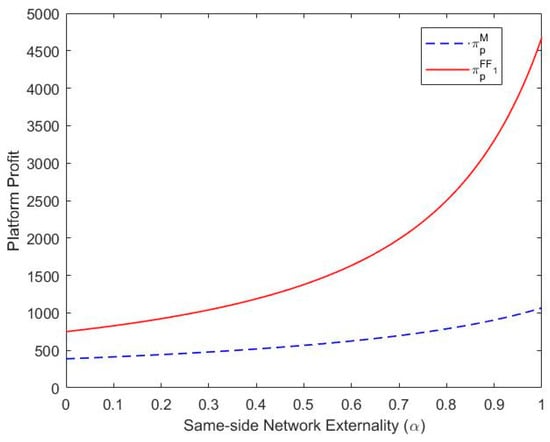

The profit of the production-capacity-sharing platform under the FF1mode is always higher than that of the M mode (i.e., ).

Theorem 1 shows that compared to the M mode, the FF1 mode always produces higher profits for the platform. This is because the optimal membership fee of the FF1 mode is bigger than that of the M mode, and the numbers of two-sided users under the FF1 mode are also greater than under the M mode. Note that the profit function of the FF1 mode has the same expressions as that of the M mode, except for one expression about the online service level γ. Although the expression about γ is negative in the FF1 mode’s profit function, the optimal solution of γ is zero. Thus, we only need to compare two similar profit expressions of these two modes. As a result, the profit of the platform under the FF1 mode is always higher than that under the M mode, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the FF1 mode with the M mode. Note. , , , , .

This indicates that when the platform provides online payment methods for two-sided users, the number of two-sided users will be very different from that under the M mode. Although two-sided users will not choose to pay online under the FF1 mode, and the profit functions are similar under the FF1 mode and the M mode, the FF1 mode will attract more users than the M mode. This is because the platform becomes more attractive to two-sided users due to its online service when it provides online payment options. At this time, two-sided users will compare their utilities of the FF1 mode with those of the M mode, and the outcome of the comparison makes them more willing to make transactions on the platform under the FF1 mode under certain conditions. Thus, the numbers of two-sided users under the FF1 mode are higher than those under the M mode.

Moreover, the numbers of demanders and suppliers can be unequal under the M mode and the FF1 mode. Intuitively, these two numbers should be the same as in many other studies about sharing platforms [58], but those are always the C2C or B2C sharing platforms’ results. In this paper, the production-capacity-sharing platform is a B2B sharing platform. The suppliers and the demanders of such platforms are not individuals but, rather, the firms. Each supplier can serve more than one demander on the platform as long as their idle capacity is sufficient. Similarly, each demander has her unique requirements for extra capacity and may need to share capacity with several suppliers to satisfy extra requests. As a result, each demander can make transactions with every potential supplier. Thus, the number of suppliers and the number of demanders can be unequal.

Furthermore, we find that both two-sided users’ numbers increase with the same-side network externality α. This is consistent with the definition of the same-side network externality. Moreover, an increase in any of the two-sided users’ online search costs decreases the numbers of two-sided users. Consequently, the platform can make efforts to improve its same-side network externality and decrease two-sided users’ online search costs to attract more two-sided users.

Moreover, two-sided users seek positive profits. Thus, when the user i’s expected revenue from the platform increases, the user i prefers to join the platform. Conversely, an increase in the other-side user’s expected revenue hurts the user i’s revenue. According to the above characteristics, the platform can attract more two-sided users by enabling both two-sided users to receive high expected revenue from the platform under these two modes.

Finally, the platform’s optimal profit is related to two-sided users’ expected revenues ( and ). Two-sided users’ expected revenues increase the platform’s optimal profit. This means that the platform does not compete with two-sided users; in fact, they have a mutual win–win relationship. Theorem 1 indicates that the production-capacity-sharing platform should provide online payment methods for two-sided users, although two-sided users may still choose to pay offline.

4.2.2. The Comparison of the FN1 Mode with the M Mode

We make satisfy . The comparison of the production-capacity-sharing platform’s profit under the FN1 mode with that of the M mode is shown in Theorem 2.

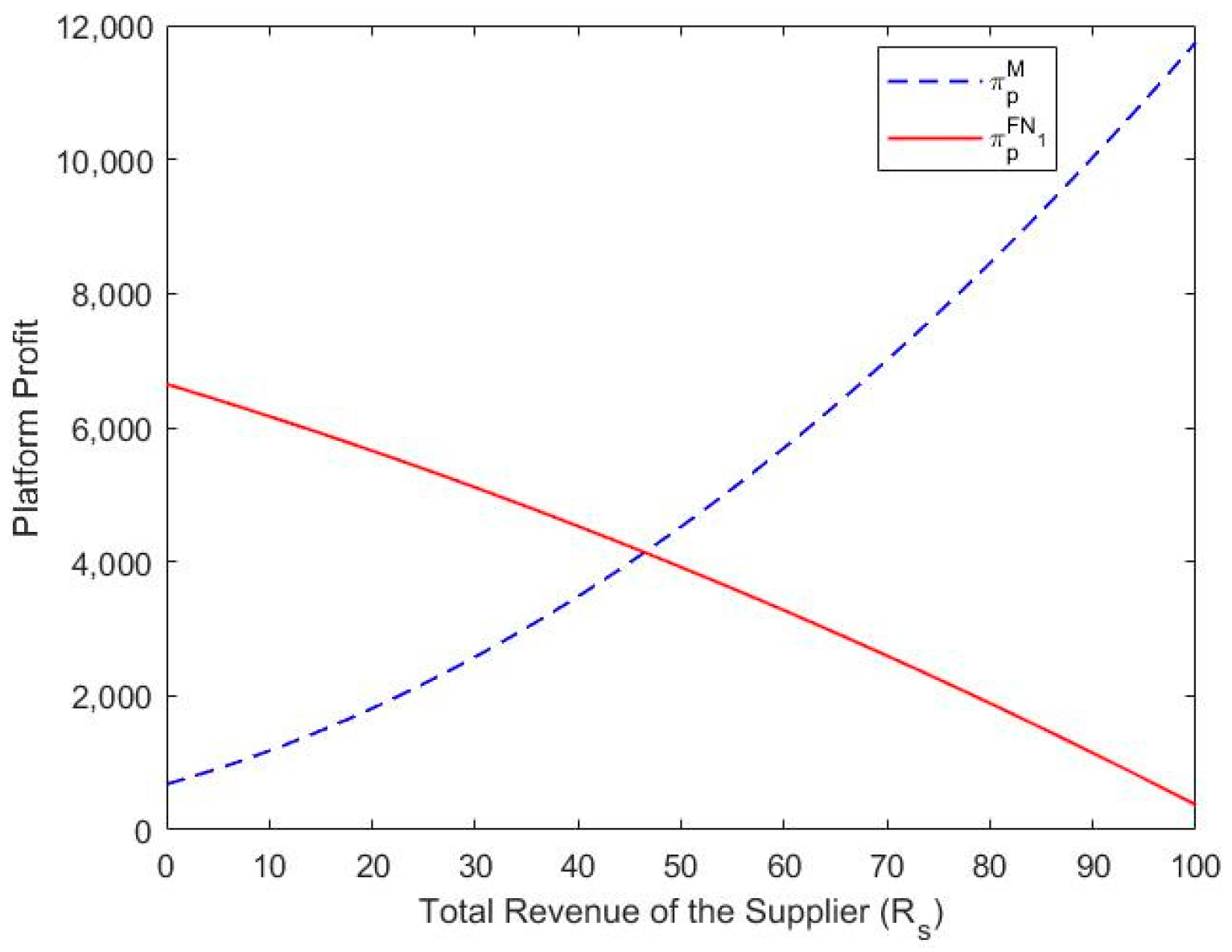

Theorem 2.

- (a)

- If , the production-capacity-sharing platform generates higher profit under the FN1mode than the M mode (i.e., ).

- (b)

- If , the production-capacity-sharing platform generates higher profit under the M mode than the FN1mode (i.e., ).

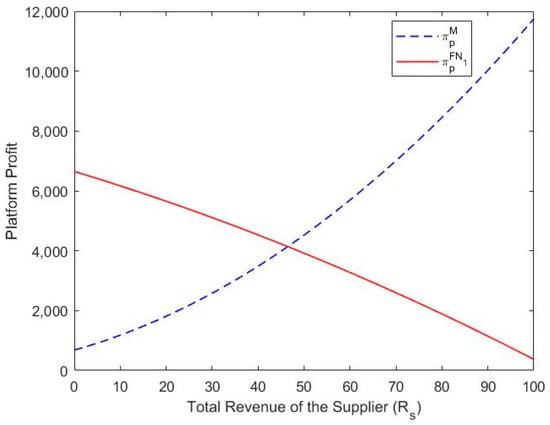

Theorem 2 reveals that either the FN1 mode or the M mode can generate higher platform profit, depending on market conditions. Figure 3 illustrates the comparison of these two modes.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the FN1 mode with the M mode. Note. , , , , , , , , , .

Note that represents the expected revenue of the supplier. When the platform forecasts that the supplier’s expected revenue will be less than , the FN1 mode will be the platform’s best choice. Otherwise, the M mode will be the platform’s best choice. The conditions of segment the potential suppliers of the platform. The suppliers who choose the FN1 mode are those who have the intention to learn about paying online. Interestingly, we find that the number of suppliers under the M mode is always higher than that under the FN1 mode, while the number of demanders under the M mode is always less than that under the FN1 mode. Furthermore, the platform’s optimal membership fee under the M mode is initially less than that under the FN1 mode, and then it becomes larger as increases. According to the above comparisons, we can conclude that two-sided users’ numbers, the platform’s optimal membership fee, and the platform’s profit are closely related to the supplier’s expected revenue . Although the platform has extra income from a fixed service fee when employing the FN1 mode, the platform’s profit under the FN1 mode also relates to the platform’s membership fee, online service level, and number of two-sided users, which are not always superior to those under the M mode. Thus, when the supplier’s expected revenue is less than , the platform could charge two-sided users a higher membership fee under the FN1 mode and obtain higher profit under this mode. As increases, the number of suppliers under the M mode increases, while that under the FN1 mode decreases. The optimal membership fee of the platform under the M mode is higher than that under the FN1 mode. Considering the other parameters, the platform receives superior profit under the M mode when is larger than .

This indicates that the platform’s optimal payment method strategy is associated not only with the same-side network externality but also with the supplier’s expected revenue from the platform. The platform could make a forecast about the supplier’s potential revenue when making payment method selections. To be specific, the platform can make a rough estimate about the supplier’s revenue based on the historical data. Moreover, the platform can also build a machine learning model to accurately predict the revenue of the supplier by analyzing historical data, the behavior of the supplier, and the market demand. Furthermore, the platform can also advise the supplier that they will earn less or more expected revenue than , and can then make payment method selection strategies accordingly.

Moreover, we find that the FN1 mode has some similarities with the M mode and the FF1 mode. For instance, the numbers of two-sided users under the FN1 mode can also be unequal. The rationale for this result under the FN1 mode is comparable to that under the M mode and the FF1 mode. Furthermore, the platform has three variables—membership fee, fixed service fee, and online service level—to adjust to attract two-sided users to join and conduct transactions on the platform. The platform’s online service level is not zero, unlike that of the FF1 mode, because two-sided users will utilize the platform’s online service under the FN1 mode; thus, the platform should make efforts in terms of its online service to make itself more attractive.

Finally, we observe that the numbers of two-sided users under the M mode and the number of demanders under the FN1 mode increase with α, while the number of suppliers under the FN1 mode decreases with α. As a result, the platform can improve its same-side network externality to attract more demanders, no matter which mode the platform adopts. However, the platform can only attract more suppliers by improving its same-side network externality when it employs the M mode. In other words, increasing the same-side network externality is not always good for the platform. The platform should ensure that the same-side network externality satisfies its corresponding conditions under each mode when the platform tries to improve it.

4.2.3. The Comparison of the FN2 Mode with the M Mode

Let satisfy . Theorem 3 summarizes the comparison of the production-capacity-sharing platform’s profit under the FN2 mode with the M mode:

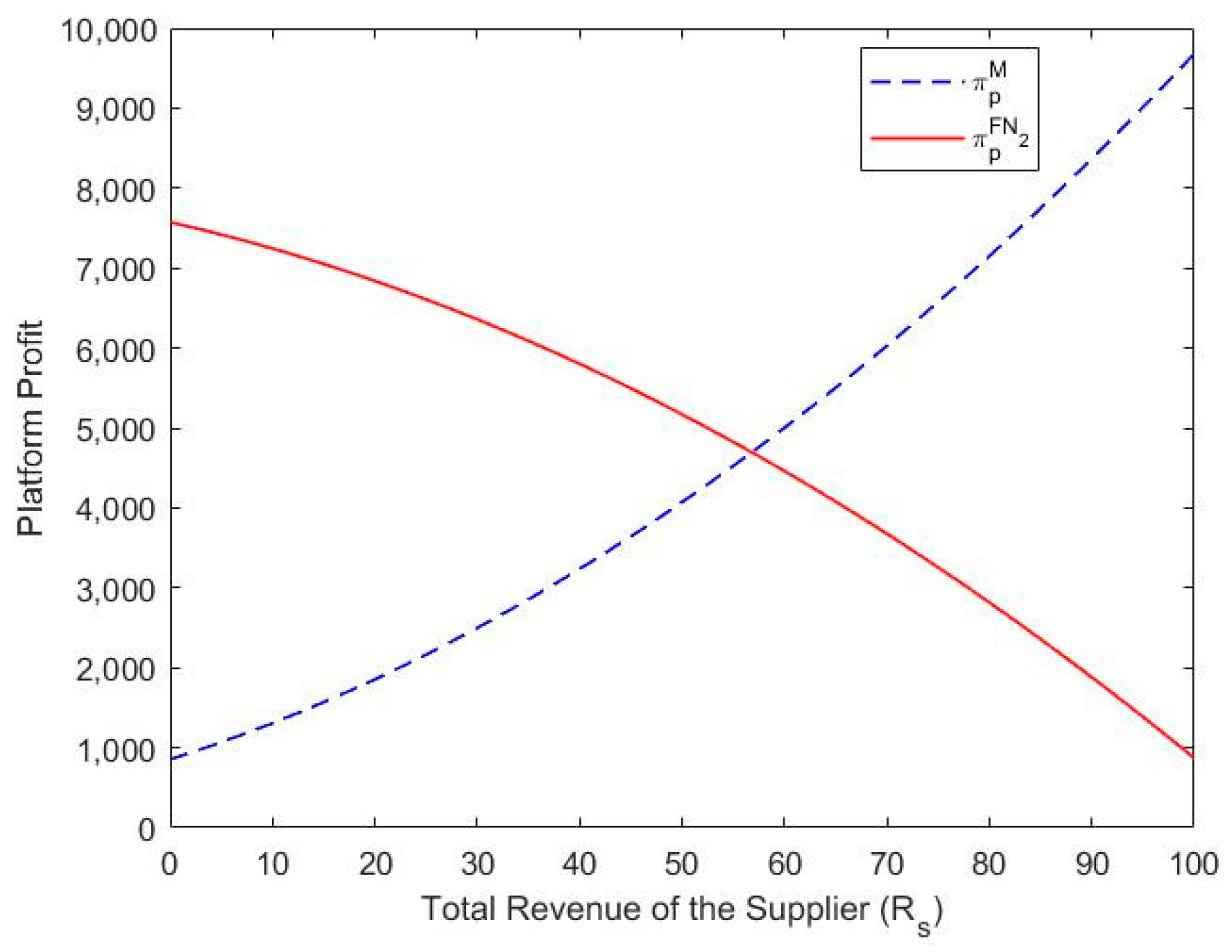

Theorem 3.

- (a)

- If , the production-capacity-sharing platform generates higher profit under the FN2mode than the M mode (i.e., ).

- (b)

- If , the production-capacity-sharing platform generates higher profit under the M mode than the FN2mode (i.e., ).

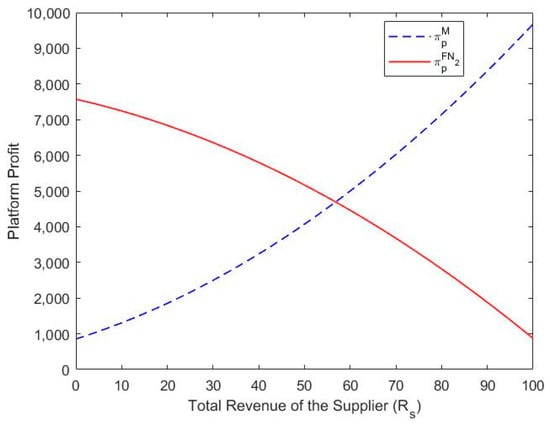

Theorem 3 reveals that either the FN2 mode or the M mode can generate higher platform profit, depending on market conditions. The reason for choosing the parameter as the benchmark is similar to that of Theorem 2. Figure 4 illustrates the comparison of the FN2 mode with the M mode.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the FN2 mode with the M mode. Note: , , , , , , , , , .

Here, the parameter is the expected revenue of the supplier. When the platform forecasts that will be less than , the platform’s best choice will be the FN2 mode; otherwise, the M mode will be the platform’s best option. The conditions of segment the potential suppliers of the platform. Note that the number of suppliers under the M mode is less than that under the FN2 mode when is no more than , while the number of suppliers under the FN2 mode is less than that under the M mode when is larger than . Meanwhile, the number of demanders under the M mode is always less than that under the FN2 mode, and the membership fee under the FN2 mode is always higher than that under the M mode. Thus, the two-sided users’ numbers are the key to the platform’s profit. The platform can make efforts to attract more two-sided users to join the platform for higher profits.

Finally, similar to the above three modes, we find that two-sided users’ numbers under the FN2 mode can be unequal. This is because the platform is a B2B sharing platform. Moreover, the platform has three variables—membership fee, fixed service fee, and online service level—to adjust to attract two-sided users. The platform’s online service level is not zero, which is similar to that under the FN1 mode.

4.3. Impacts of the Same-Side Network Externality and the Online Search Costs

In this section, we examine the roles of the platform’s same-side network externality and two-sided users’ online search costs in the production-capacity-sharing platform. The platform’s same-side network externality is α, and the two-sided users’ online search costs are ηd and ηs, respectively. Therefore, we calculate the marginal impacts of these three parameters on the platform’s optimal solutions under these different payment modes.

Theorem 4.

Under the M mode and the FF1mode,

- (a)

- The platform’s same-side network externality increases the platform’s membership fee when (i.e., and ), and decreases the platform’s membership fee when (i.e., and );

- (b)

- The platform’s same-side network externality increases the platform’s profit (i.e., and );

- (c)

- The online search cost of the demander decreases the platform’s membership fee and the platform’s profit (i.e., , , and );

- (d)

- The supplier’s online search cost increases the platform’s membership fee (i.e., and ), and decreases the platform’s profit (i.e., and ).

The effects of same-side network externality on the profits of the platform under the mode and the FF1 mode, as shown by Theorem 4(b), are consistent with noted findings about the implications of network externalities on the sharing platform [27]. In addition, we find that α does not always increase the platform’s membership fee under these two modes. As shown by Theorem 4(a), when the supplier’s online search cost is higher than the demander’s, an increase in α benefits the platform’s membership fees under these two modes. When the supplier’s online search cost is lower than the demander’s, an increase in α forces the platform to reduce its membership fees under these two modes. This result arises because of the consideration of two-sided users’ online search costs, which are not fixed. To be specific, these two costs are variable as the outside transaction environment changes. For instance, the supply chain could be broken, and many manufacturers might have to stop their production for certain emergencies, such as the COVID-19 outbreak. As a result, if such manufacturers join the platform, they are the demanders on the platform, and they are in urgent need of the available idle capacity of the suppliers on the platform. Note that the demanders are more anxious than the suppliers about their orders. Thus, the demanders’ online search cost is higher than the suppliers’ in this situation.

In contrast, when the whole economic environment is stable, the manufacturers can always finish their orders through their capacity, and some of them may have extra capacity after finishing their orders. Under this situation, such manufacturers are the suppliers on the platform, and they are more aggressive in finding potential demanders to make profits from their idle capacity. Thus, the demanders’ online search cost is less than the suppliers’ in this situation. Consequently, α increases the platform’s membership fee when .

As shown by Theorem 4(c), an increase in the demander’s online search cost always decreases the platform’s membership fees and profits under these two modes. This is consistent with our intuition. When the demander’s online search cost increases, the demander’s utility and the number of demanders who join the platform under these two modes decrease. Thus, the platform needs to set a lower membership fee to attract the demanders to join the platform, which leads to a decrease in the platform’s profit.

As for the impacts of the supplier’s online search cost, they differ slightly from those of the demander’s, as shown by Theorem 4(d). An increase in the supplier’s online search cost benefits the platform’s membership fees but reduces the platform’s profits under the M mode and the FF1 mode. This is counterintuitive. When the supplier’s online search cost increases, the supplier still prefers to join the platform because they have a stronger desire to complete as many transactions on the platform as possible, compared to the demander for their idle capacity. However, according to the number of expressions of the suppliers under these two modes, the number of suppliers decreases with the supplier’s online search cost. As a result, the platform profits under these two modes will decrease with the supplier’s online search cost for these comprehensive reasons.

Theorem 5.

Under the FN1mode and the FN2mode,

- (a)

- The platform’s same-side network externality increases the platform’s membership fee, fixed service fee, online service level, and profit (i.e., , , , , , , and );

- (b)

- The demander’s online search cost decreases the platform’s membership fee, fixed service fee, online service level, and profit (i.e., , , , , , , and );

- (c)

- The supplier’s online search cost decreases the platform’s membership fee, fixed service fee and profit (i.e., , , , , and ), increases the platform’s online service level (i.e., ) under the FN1mode, and decreases the platform’s online service level (i.e., ) under the FN2mode.

The implications of same-side network externality (α) for the platform’s membership fee, fixed service fee, online service level, and profit under the FN1 mode and the FN2 mode, as shown by Theorem 5(a), are also consistent with the results about the impacts of network externality on the sharing platform [27]. When α increases, more two-sided users are attracted to join the platform, which encourages the platform to increase its membership fee, fixed service fee, and online service level, and then the platform’s profit increases accordingly.

As shown by Theorem 5(b), an increase in the demander’s online search cost decreases the platform’s membership fee, fixed service fee, online service level, and profit under these two modes. When increases, the demander’s utilities under these two modes decrease, forcing the number of demanders joining the platform to decline. Thus, the platform decreases its membership fee and its fixed service fee to attract more demanders to join the platform. When the platform decreases its membership fee and fixed service fee, the platform’s profit decreases. As a result, the platform does not have a strong will to improve its online service level, preferring to reduce costs. When increases, the platform’s profit decreases under these two modes.

As for Theorem 5(c), the impacts of the supplier’s online search cost are slightly different from those of the demander’s. Similarly to Theorem 5(b), when increases, the platform decreases its membership fee and fixed service fee under these two modes to attract more suppliers to join the platform. As for the platform’s online service level, has different impacts on it under these two modes. An increase in increases the platform’s online service level under the FN1 mode and decreases it under the FN2 mode. This result arises because the two-sided users under these two modes are quite different. Under the FN1 mode, this result is due to two-sided users’ different perceptions of the platform’s online service. The supplier obtains more utility from the platform’s online service than the demander. Thus, the platform would prefer to increase its online service level under the FN1 mode to attract more suppliers to join the platform. Under the FN2 mode, the reason for the impact of on the platform’s online security level is that the number of suppliers decreases with the increase in , and the number of suppliers under the FN2 mode declines at a much faster rate than under the FN1 mode. Although the platform wants more suppliers to join the platform, improving its online service level is not a good idea anymore, because the deep decline in the number of suppliers does not encourage the platform to invest more in its online service level. As a result, when increases, the platform decreases its online service level.

Overall, the analysis in this section indicates the impacts of the same-side network externality and two-sided users’ online search costs on the platform’s best solutions under the M mode, the FF1 mode, the FN1 mode, and the FN2 mode. Although most of the effects of the same-side network externality on the production-capacity-sharing platform could be the same as those in the sharing platforms in qualitative terms, the impacts under the M mode and the FN1 mode are new and reveal the importance of two-sided users’ online search costs. Moreover, the effects of two-sided users’ online search costs are complicated and show their importance to the production-capacity-sharing platform.

5. Conclusions

Motivated by the growing popularity of production-capacity-sharing platforms, we examined the payment method strategies of two-sided users for production-capacity-sharing platforms in a sharing economy context, where the two-sided users have online search costs when they search for potential trading on the platform. We considered two payment modes—M mode and F mode (with sub-modes FF1, FN1, and FN2)—and examined the implications of the platform’s same-side network externality and two-sided users’ online search costs on the platform. We found that the platform that adopts the FF1 mode always generates higher profit than that under the M mode, while the comparisons of the FN1 and FN2 modes with the M mode showed quite different results. We found that which mode benefits the platforms depends critically on the same-side network externality or the expected revenue of the supplier. Meanwhile, there are significant variations in the implications of these modes for the platform.

Our analysis yields two key findings: First, regarding the provision of online payment options, our results demonstrate the following: (1) Two-sided users’ optimal payment mode selection is context-dependent, with each mode demonstrating superiority under specific market conditions. When users exhibit strong offline payment preferences, platforms lack economic incentives to introduce online options. (2) When suppliers’ expected revenues fall below a critical threshold (), platforms should implement online payment systems. Conversely, when , maintaining offline-only systems proves optimal. Therefore, platform operators must incorporate suppliers’ revenue expectations into strategic decision-making. Second, platform performance is significantly influenced by both same-side network externalities () and users’ online search costs (). Notably, these effects exhibit modality-specific variations across payment modes. Specifically, under the FN mode, platform benefits increase monotonically with network externality strength, which is consistent with noted findings about the implications of network externalities on the sharing platform [27]. However, in M mode and FF mode, network externality effects are moderated by users’ search costs. Most critically, increased search costs generally impair platform performance across all modes, with limited exceptions near optimal solutions.

This study also makes three key theoretical and practical contributions: First, we have developed a novel two-sided market model that captures the essential features of production-capacity-sharing platforms, providing a theoretical framework for understanding the platforms’ payment mode selection strategies. Second, we have shown the strategic interdependence between platforms and their two-sided users. In practice, they need to observe one another’s behaviors to make better decisions. Third, we have derived actionable insights for platforms to optimize user acquisition and profitability through strategic management of network externalities and online search costs.

Our findings generate several managerial implications. First, our study emphasizes how crucial market factors are to the platform’s different payment modes. Although the FF1 mode always brings higher profit for the production-capacity-sharing platform than the M mode without any conditions, the M mode does not always perform badly compared with the FN1 and FN2 modes. In the production-capacity-sharing economy, where the expected revenue of the supplier is higher than the computed thresholds, the M mode performs better than the FN1 and FN2 modes. Hence, the platform could build a machine learning model to accurately predict the expected revenue of the supplier by analyzing historical data, such as the transaction amounts of historical orders on the platform, the behavior of the supplier, and the market demand, allowing it to make the best selection of payment method strategies. When the platform makes a good decision, the platform could encourage more two-sided users to join the platform through certain business strategies, such as improving the same-side network externality.

Second, our study highlights the important implications of the same-side network externality on the production-capacity-sharing platform. Given the novelty of the production-capacity-sharing platform, the platform must understand the complexities of its same-side network externalities associated with the various payment modes that it has adopted. For instance, our results indicate that, unlike the wisdom in the existing sharing platform literature, the implications of the same-side network externality on the production-capacity-sharing platform’s optimal solutions are not always positive; they are also associated with two-sided users’ online search costs. Therefore, from the production-capacity-sharing platform’s point of view, even though an increase in the same-side network externality usually benefits the platform, the platform should consider two-sided users’ online search costs to ensure that the impacts are positive.

Third, our study reveals the significant implications of two-sided users’ online search costs for the production-capacity-sharing platform. Most of the literature about sharing platforms ignores the effects of two-sided users’ online search costs, which are generated when they use the platform. Our study indicates that two-sided users’ online search costs have different effects on the platform under different payment modes. Although an increase in both two-sided users’ online search costs decreases the platform’s profit no matter which modes the platform takes, some differences exist in the effects of such an increase on the platform’s membership fee and online service level. Our results suggest that the platform could raise its membership fee when the platform employs the M mode and the FF1 mode. When the platform takes the FN mode, the platform should consider two-sided users’ online search costs more clearly. The platform does not always need to decrease its online service level when the supplier’s online search cost increases but rather to improve its online service level appropriately to attract more suppliers to join the platform. Finally, the platform could take advantage of the various changes in these market characteristics.

Although we offer several interesting findings in this paper, it still has a few limitations that could lead to more research. First, we made some assumptions to simplify the calculation, such as the same membership fee and same-side network externality for two-sided users and the potential transactions under the FN mode. Relaxing these assumptions may generate different results. Second, we could consider the cross-side network externality in the platform’s profit models as a future research direction. Third, many two-sided users first select potential businesses on the platform and then choose to make transactions without the platform, because such behavior can enable them to avoid paying the platform. Based on this paper, future studies could explore how to make two-sided users obey the platform’s business rules and not trade without the platform. Fourth, the production-capacity-sharing platform is beneficial to the development of low-carbon supply chains. We could study how the production-capacity-sharing platform could reduce carbon emissions and promote the development of low-carbon supply chains. Finally, we did not consider the situation where some two-sided users choose to pay offline while others choose to pay online. In reality, this is more complicated than our models in this paper. We will build new models to explore this situation in our future research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jtaer21010005/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y. and D.Z.; methodology, S.Y.; software, S.Y.; validation, S.Y., Z.Y. and J.H.; formal analysis, S.Y.; investigation, S.Y., J.H. and Z.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.; writing—review and editing, S.Y. and Z.Y.; supervision, D.Z.; funding acquisition, D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number 72072125. And the APC was funded by Daozhi Zhao.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, T.; Leng, J.; Zhu, S.; Fu, R. Digital Transformation and Enterprise Innovation Capability: From the Perspectives of Enterprise Cooperative Culture and Innovative Culture. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Information Center’s Sharing Economy Research Center. Annual Report on the Development of China’s Sharing Economy; State Information Center’s Sharing Economy Research Center: Beijing, China, 2023. (In Chinese)

- Liepold, C.J.; Arslan, O.; Laporte, G.; Schiffer, M. The Impact of Partial Production Capacity Sharing via Production as a Service. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 165, 106587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Han, P.; Qi, L. Time-sensitive supply chain disruption recovery and resource sharing incentive strategy. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2021, 6, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, H.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ran, Y. Knowledge Sharing Strategy and Emission Reduction Benefits of Low Carbon Technology Collaborative Innovation in the Green Supply Chain. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 9, 783835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, Z.; Xia, L. Revenue sharing contracts for horizontal capacity sharing under competition. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 291, 731–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Han, H.; Shang, J.; Hao, J. Decisions and coordination in a capacity sharing supply chain under fixed and quality-based transaction fee strategies. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 150, 106841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Wu, X. Capacity Sharing Between Competitors. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 3554–3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Wang, J. Horizontal capacity sharing between asymmetric competitors. Omega 2020, 97, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.L.; Shapiro, C. Network externalities, competition, and compatibility. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 424–440. [Google Scholar]

- Rochet, J.C.; Tirole, J. Platform competition in two-sided markets. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2003, 1, 990–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Wu, D. Platform Competition Under Network Effects: Piggybacking and Optimal Subsidization. Inf. Syst. Res. 2021, 32, 820–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, C.; Varian, H. Information Rules; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, C.; Varian, H. The art of standards wars. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1999, 41, 8–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.G.; Parker, G.G.; Tan, B. Platform Performance Investment in the Presence of Network Externalities. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 152–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chamnisampan, N. Platform entry and homing as competitive strategies under cross-sided network effects. Decis. Support Syst. 2021, 140, 113–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Hou, B.; Yu, W.; Lu, X.; Yang, C. Applications of artificial intelligence in intelligent manufacturing: A review. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. C 2017, 18, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Willems, S.P.; Dai, Y. Channel Selection and Contracting in the Presence of a Retail Platform. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2019, 28, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xie, X.; Liu, J. Capacity sharing with different oligopolistic competition and government regulation in a supply chain. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2020, 41, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Nu, Y. Pricing and capacity allocation strategies: Implications for manufacturers with product sharing. Nav. Res. Logist. 2020, 67, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Chu, Z. Capacity sharing, product differentiation and welfare. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2020, 33, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, P.; Argoneto, P. Capacity sharing in a network of independent factories: A cooperative game theory approach. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2011, 27, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argoneto, P.; Renna, P. Supporting capacity sharing in the cloud manufacturing environment based on game theory and fuzzy logic. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2016, 10, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloui, C.; Jebsi, K. Platform optimal capacity sharing: Willing to pay more does not guarantee a larger capacity share. Econ. Model. 2016, 54, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, B. Competing in multi-sided markets: Divide and conquer. Am. Econ. J. Microecon. 2011, 3, 186–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Van Alstyne, M.W. Two-sided network effects: A theory of information product design. Manag. Sci. 2005, 51, 1494–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M. Competition in two-sided markets. RAND J. Econ. 2006, 37, 669–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Bhaskaran, S.; Mukherjee, R. An analysis of search and authentication strategies for online matching platforms. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 2412–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Chen, M. Ex-ante versus ex-post destination information model for on-demand service ride-sharing platform. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 279, 301–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Jia, L.; Hu, X. Operation decision model in a platform ecosystem for car-sharing service. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 59, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhen, L.; He, X.; Tian, X. Operations optimization for third-party e-grocery platforms. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 332, 831–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Du, Z.; Zhang, X. Clustering analysis and punishment-driven consensus-reaching process for probabilistic linguistic large-group decision-making with application to car-sharing platform selection. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2022, 29, 2002–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, M.; Yang, S. Differential pricing strategies of ride-sharing platforms: Choosing customers or drivers? Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2022, 29, 1089–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cennamo, C.; Santalo, J. Platform competition: Strategic trade-offs in platform markets. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 1331–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, L.; Zhong, G. The optimal pricing strategy for two-sided platform delivery in the sharing economy. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2017, 101, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adner, R.; Chen, J.; Zhu, F. Frenemies in Platform Markets: Heterogeneous Profit Foci as Drivers of Compatibility Decisions. Manag. Sci. 2020, 66, 2432–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Anderson, E.G.; Parker, G.G. Platform Pricing and Investment to Drive Third-Party Value Creation in Two-Sided Networks. Inf. Syst. Res. 2020, 31, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.P.; Renault, R. Pricing, Product Diversity, and Search Costs: A Bertrand-Chamberlin-Diamond Model. RAND J. Econ. 1999, 30, 719–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salop, S.; Joseph, S. Bargains and Ripoffs: A Model of Monopolistically Competitive Price Dispersion. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1977, 44, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, D.O. Oligopolistic Pricing with Sequential Consumer Search. Am. Econ. Rev. 1989, 79, 700–712. [Google Scholar]

- Wolinsky, A. True Monopolistic Competition as a Result of Imperfect Information. Q. J. Econ. 1986, 101, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Smith, M.D. Frictionless commerce? A comparison of Internet and conventional retailers. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 563–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.R.; Goolsbee, A. Does the Internet make markets more competitive? Evidence from the life insurance industry. J. Polit. Econ. 2002, 110, 481–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, A.T. Equilibrium price dispersion in retail markets for prescription drugs. J. Polit. Econ. 2000, 108, 833–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.P. Intermediation and Electronic Markets: Aggregation and Pricing in Internet Commerce; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo, A. Are Online and Offline Prices Similar? Evidence from Large Multi-Channel Retailers. Am. Econ. Rev. 2017, 107, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.G. Do Electronic Marketplaces Lower the Price of Goods? Commun. ACM 1998, 41, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachon, G.P.; Terwiesch, C.; Xu, Y. On the effects of consumer search and firm entry in a multiproduct competitive market. Mark. Sci. 2008, 27, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulayev, S. Estimating Demand in Online Search Markets, with Application to Hotel Bookings. Rand J. Econ. 2014, 45, 553–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Santos, B.; Hortacsu, A.; Wildenbeest, M.R. Search with Learning for Differentiated Products: Evidence from E-Commerce. J. Econ. Bus. Stat. 2017, 35, 626–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukes, A.; Liu, L. Online Shopping Intermediaries: The Strategic Design of Search Environments. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 1064–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Zou, T. Consumer Search and Filtering on Online Retail Platforms. J. Mark. Res. 2020, 57, 900–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Wang, Y. Consumer Online Search with Partially Revealed Information. Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 4215–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.L.; Shapiro, C. Systems Competition and Network Effects. J. Econ. Perspect. 1994, 8, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, A.; Sundaresan, S.; Zhang, B. Browse-and-Switch: Retail-Online Competition under Value Uncertainty. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2014, 23, 1129–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frambach, R.T.; Roest, H.C.A.; Krishnan, T.V. The impact of consumer internet experience on channel preference and usage intentions across the different stages of the buying process. J. Interact. Mark. 2007, 21, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhou, R.; Yang, S. Research on Pricing Strategy of Capacity Sharing Platform Considering Service Level. Control. Decis. 2023, 38, 805–814. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, J.; Raghunathan, S. Two-Sided Platform Competition in a Sharing Economy. Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 8909–8932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.