Abstract

As mobile payments gain global prevalence, understanding the factors driving their sustained usage becomes imperative. WeChat Pay, integrated into China’s dominant social platform, provides a distinctive context for examining mobile payment continuance intention. This study extends the Technology Acceptance Model by incorporating trust, network externalities, and application-specific features (red envelopes and interface design) to explore users’ continuance intention toward WeChat Pay. We analyzed 650 valid responses from experienced WeChat Pay users using partial least squares structural equation modeling. The results demonstrated that trust and network externalities significantly shape continuance intention, while red envelopes and interface designs further encourage ongoing use. This study offers a comprehensive integrated framework for understanding the continuance of mobile payments and provides actionable guidance for product development and strategic planning.

1. Introduction

With the advancement of mobile internet and smart devices, mobile payment has become a global trend and a primary payment method [1,2]. It is a payment method that uses mobile devices such as smartphones to pay for goods, services, and bills [3,4]. The simplicity and convenience of mobile payments enable them to serve as integrated payment services that replace traditional transaction tools [5,6]. Mobile payments have significantly increased the efficiency of financial services and provided users with a flexible and secure payment experience. They have opened new avenues for business innovation, boosting consumer market activity and supporting the growth of the digital economy. The market expanded markedly during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data from the GSM Association [7] indicates a 22% year-over-year increase, with daily transaction values exceeding USD 345 million in 2022.

WeChat Pay stands as a leading platform in China’s mobile payment market. Launched by the Chinese IT company Tencent in 2013, WeChat Pay introduced a novel payment model featuring a digital wallet integrated into the WeChat social platform [4]. It supports multiple payment methods, including quick payment, quick response (QR) code payment, web-based payment, and in-app payment [4]. Furthermore, WeChat provides secure and convenient payment services across diverse scenarios such as shopping, transportation, and bill payments. Building on WeChat’s vast user base and robust social networks, WeChat Pay has moved beyond being a simple payment tool to become an integrated ecosystem that combines social interaction, entertainment, commerce, and payments. According to Tencent’s financial report [8], WeChat Pay’s (including international versions) annual active users reached 1.3 billion in 2023. Moreover, WeChat Pay’s transaction volume amounted to 67.81 trillion yuan in the third quarter of 2023, ranking second in the Chinese market [9]. As a novel payment model embedded in China’s dominant social platform, investigating the factors influencing users’ continuance intention toward WeChat Pay is of significant value. Therefore, this study empirically examines these usage intentions to provide insights into the sustainable development of the mobile payment industry.

Mobile payment has been a focal point in academic research, with substantial literature examining its usage intentions [10,11]. However, few studies have explored users’ continuance intentions in the WeChat Pay context [4]. This gap highlights the need to introduce classical theoretical models to concretize this complex research phenomenon. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) provides a comprehensive framework for explaining users’ acceptance of information technology and systems [12,13]. Extensive studies have validated its applicability across diverse domains, including e-commerce [14], social media [15], and mobile applications [16]. To address specific research needs, scholars often extend TAM by combining it with other theories or by introducing new variables. For example, Nan et al. [17] combined TAM with Expectation Confirmation Theory and introduced perceived security, ubiquity, and enjoyment to explain the continued use of mobile payments. WeChat Pay integrates mobile payments with social media; therefore, extending TAM is necessary to capture users’ attitudes and responses. Accordingly, this study extends TAM by adding three variable groups: trust, network externalities, and application-specific features. We examined their influence pathways and predicted users’ continuance intentions.

Trust is recognized as an essential cognitive construct in online contexts involving uncertainty and risk [18]. This is particularly true for mobile payment scenarios, where users face risks, such as financial insecurity and privacy breaches [19]. Prior studies have identified trust as a significant factor that promotes user acceptance and the subsequent usage of mobile payments [10,20]. However, research on the antecedents of trust in this context remains limited [18]. Therefore, it is necessary to explore further how trust and its antecedents shape users’ continuance intention toward WeChat Pay. Furthermore, network externalities represent a key external factor influencing user behavior within platform ecosystems. This concept describes the phenomenon whereby the utility that a user derives from a product or service increases with the expansion of its user base [21]. They are generally divided into two types: direct and indirect network externalities [22,23]. Although prior research has examined network externalities in social media [24] and general mobile payments [25], their distinct roles in an integrated platform, such as WeChat Pay, have not been fully explored. Accordingly, this study explores the impact of direct and indirect network externalities on the continued usage intention toward WeChat Pay.

Beyond the cognitive and external factors discussed above, certain features of the application may attract users to continue using it. Therefore, this study innovatively introduces two key features of WeChat Pay: red envelopes and interface design. The red envelope function integrates financial payments with social interaction and has attracted a substantial number of users [1]. Its simple and memorable interface design also plays a key role in enhancing user experience [26]. These two core features constitute WeChat Pay’s differentiated competitive advantage and may influence users’ continued use of the service. Subsequently, by integrating these application-specific features with trust factors and network externalities, this study proposes a more comprehensive framework for understanding the determinants of WeChat Pay continuance intention. In summary, this study attempts to answer three specific questions tailored to the WeChat Pay context: (1) Does trust affect the continued use of WeChat Pay, and by what? (2) Do network externalities affect the continued use of WeChat Pay, and by what? (3) Do application-specific features affect the continued use of WeChat Pay, and by what?

For clarity, the study is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the theoretical foundation of this study. Section 3 presents the hypotheses. Section 4 describes the study’s methodology and research design. Section 5 presents data analysis and hypothesis tests. Section 6 discusses the findings of the study. Section 7 outlines the theoretical and practical implications of the study, as well as addresses its limitations and suggests directions for future research.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. TAM

TAM is widely recognized as one of the most influential theoretical frameworks for understanding user acceptance of information technology [27]. Originally developed by Davis [12] based on TRA, this model aims to elucidate how users perceive and adopt innovative technologies [28]. TAM has demonstrated significant potential in information systems research [29,30] as it offers a concise yet powerful explanation of technology use, enabling researchers and practitioners to identify key determinants and devise effective strategies. The applicability of this model has been extensively validated across various emerging technologies, including social media [31], mobile learning [32], mobile travel applications [16], social commerce [14], and artificial intelligence-enabled technologies [33].

TAM identifies two key determinants of technology adoption: perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use [34]. Perceived usefulness is defined as the degree to which an individual believes that using a technology will enhance their performance or efficiency, while perceived ease of use refers to the extent to which a user believes that using a specific system will be free of effort [12,35]. Furthermore, attitude is defined as an individual’s positive or negative evaluation of using a technology [12,36] and serves as another crucial variable within the model. This model posits that perceived ease of use positively affects perceived usefulness. Perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use jointly influence user attitudes, which subsequently affect usage intention and ultimately determine actual usage behavior [36]. This psychological-behavioral pathway forms a coherent causal chain that enables researchers to predict technology usage outcomes based on users’ cognitive perceptions [12].

Researchers frequently extend TAM by integrating other theories or incorporating specific variables to enhance the model’s explanatory power across different technological contexts. This practice of contextual refinement has solidified TAM’s position as a prevalent theoretical framework in mobile payment research [37]. For instance, Nan et al. [17] combined TAM with expectation-confirmation theory, adding variables such as perceived security, ubiquity, and enjoyment to explain the continued use of mobile payments. Similarly, Tian et al. [38] integrated TAM with the theory of planned behavior to investigate e-wallet adoption by examining the moderating roles of perceived trust and service quality. WeChat Pay blends payment and social media functions, making TAM extension especially relevant for understanding continuance intentions. Therefore, this study extends the TAM framework by incorporating variables such as trust, network externalities, and application-specific features to explore users’ continuance intention toward WeChat Pay.

2.2. Perceived Trust

Trust is a well-established construct that has been extensively studied across multiple disciplines [18], resulting in diverse conceptualizations. Trust is the set of beliefs that other people act appropriately [39]. Morgan and Hunt [40] defined trust as confidence in an exchange partner’s reliability and integrity. Mayer et al. [41] defined trust as “the willingness to be vulnerable based on the expectation that another party will perform a particular action important to the trustor.” Trust is particularly critical in online transaction contexts involving uncertainty and risk [42,43]. Previous studies have demonstrated that trust significantly influences users’ behavioral intentions in e-commerce platforms [44], social networking services [45], and financial services [46]. Trust is of particular significance to this study because monetary payments require substantial risks to be assumed by the consumer [19]. Trust reduces the need for oversight, facilitates information sharing, promotes long-term relationships, and strengthens continuance intention.

Scholars have proposed diverse perspectives regarding the antecedents of trust [47]. For instance, Kim and Han [48] identified four key factors that shape trust beliefs: satisfaction, reputation, disposition to trust, and information quality. Similarly, Ponte et al. [49] found that information quality, perceived security, and perceived privacy protection were positively associated with trust in e-commerce. Maqableh et al. [50] further demonstrated that both perceived privacy and perceived security significantly enhance user trust on social platforms, such as Facebook. Recently, Chin et al. [51] highlighted perceived security, perceived privacy, and familiarity as critical antecedents of trust in mobile payment environments. Although these studies provide a solid theoretical foundation, research specifically focusing on trust antecedents in mobile payment contexts remains relatively limited [18]. Since payment information is highly sensitive, users prioritize privacy, security, and accuracy. Accordingly, this study specifies perceived privacy, perceived security, and information quality as precursors of trust in WeChat Pay.

2.3. Network Externalities

Broadly speaking, network externality refers to “the value or effect that users obtain from a product or service will bring about more value to consumers with the increase of users, complementary products, or services” [21]. This effect typically occurs when an individual’s participation in a network generates value for other participants [52,53], implying that the potential benefit of the network grows with the number of users [54]. In other words, the utility of a product or service is positively correlated with the total number of users [55]. Network externalities are prevalent across a wide range of digital products and services, such as social media platforms, communication tools, and e-commerce systems [24,56,57], where they exert a considerable impact on users’ perceptions and behavioral intentions. For example, Li et al. [52] reported that network externalities shape user attitudes toward completing massive open online courses (MOOC). Furthermore, Zhang et al. [22] found that they also influence the continued use of social media platforms, such as WeChat.

Network externalities are generally categorized into direct and indirect types [22,23]. Direct network externalities arise when the benefits an individual gains from a product or service increase because a growing number of new consumers use analogous products [24,58]. Direct network externalities rely on the size of the consumer base, using analogous products or services [23,54]. By contrast, indirect network externalities are defined as the accumulated benefits resulting from a significant increase in available complementary goods and services [54,59]. This means that the value of a core technology increases with the expansion of compatible support products or services [60]. Extensive research has established that both types are crucial for network-facilitated technologies [60,61]. Therefore, this study analyzes the role of network externalities in WeChat Pay by examining both the direct and indirect types.

2.4. Application-Specific Features

Application-specific features can be regarded as innovative technical attributes of an information system that differentiate it from competitors [62] and significantly influence users’ initial and continued adoption behaviors [4,63]. A key feature of WeChat Pay is the red envelope function. In traditional Chinese culture, red envelopes are commonly given as gifts during special occasions such as the Lunar New Year, birthdays, and weddings [64,65], serving as a means to convey good luck and blessings, express care and respect, and maintain social relationships [66,67]. With the advancement of mobile payment systems, this tradition evolved into a digital format [68]. In 2014, WeChat launched the “digital red envelope” feature, enabling users to easily send cash red envelopes to individuals or groups through the chat interface [69,70]. As an innovative feature of WeChat Pay, WeChat red envelopes seamlessly integrate payment behavior into social scenarios, effectively blending economic transactions with social interactions [70]. By mirroring real-world ties, WeChat’s social graph has made the red envelope exchange a routine social activity.

Interface design is also critical in shaping user experience and evaluation. Studies have identified interface design as a core dimension of service quality in desktop and mobile settings [71,72]. Well-designed interfaces enable users to identify and acquire information more efficiently [73], whereas poorly designed interfaces tend to cause confusion and misunderstandings [74]. Empirical studies have further validated the impact of interface design across diverse mobile environments, including mobile commerce [72], live-stream e-commerce [26], and smartwatches [75]. However, few studies have specifically focused on mobile payment interface design. Among its various elements, color and graphics are two critical dimensions that shape the visual environment and affect users’ perceptions. Cool colors are perceived as comfortable and calming, making them preferable in retail settings [76]. Moreover, a graphical user interface serves as the primary mobile interface [77], where size contrast and visual illusions are employed to create intuitive spatial arrangements.

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. TAM to WeChat Pay Continuance Intention

Previous studies have indicated that perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness are key factors influencing users’ adoption and use of information technology [30]. According to TAM, perceived ease of use positively affects perceived usefulness. This relationship has been empirically supported across various contexts, including e-commerce [78], educational technology [79], and mobile payment services [11]. Furthermore, TAM suggests that both perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use shape users’ attitudes toward technology. Within the specific domain of mobile payments, these relationships have been validated by studies, such as [80,81]. Accordingly, if users perceive that WeChat Pay enhances productivity and that it is easy to use, they are likely to exhibit a favorable attitude. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a.

Perceived ease of use positively affects the perceived usefulness of WeChat Pay.

H1b.

Perceived ease of use positively affects attitudes toward using WeChat Pay.

H1c.

Perceived usefulness positively affects attitudes toward using WeChat Pay.

Continuance intention is a more relevant metric than initial adoption for measuring the long-term success of an information system. Bhattacherjee [82] defined continuance intention as users’ intention to reuse an information system. Recent studies have reported that users’ continuance intention in microblogging, web-based, and social networking apps is influenced by perceived usefulness and satisfaction [13,83]. Specifically, within mobile payment services, perceived usefulness has been identified as a key determinant of continuance intention [84,85]. Furthermore, prior research has demonstrated a significantly positive relationship between attitude and intention in mobile payment contexts [37,80]. Therefore, the following hypotheses are further proposed:

H1d.

Perceived usefulness positively affects continuance intention toward WeChat Pay.

H1e.

Attitude positively affects continuance intention toward WeChat Pay.

3.2. Perceived Trust and Its Antecedents

Perceived privacy is “an individual’s self-assessed state, where others have limited access to their information” [86]. Consumers may worry that mobile payment systems will collect and share personal information with third parties without consent, thereby violating their privacy [87]. Perceived privacy is central to sustaining user trust and confidence [88]. Evidence indicates a strong effect of trust in social networking services [50]. Insufficient privacy protection by WeChat Pay substantially undermines user trust.

Perceived security refers to the extent to which consumers believe that their property and personal information are protected when using mobile devices for transactions [89]. Security is critical to mobile payment systems, as users are particularly concerned about their protection against unauthorized interception, fraudulent use, and financial loss [51]. Customer trust in electronic payment systems relies on robust security mechanisms [90]. Several studies have confirmed a positive relationship between perceived security and trust [47,91]. Consequently, we anticipate a positive association between perceived security and trust.

Information quality refers to the extent to which users perceive the information provided as current, accurate, relevant, useful, and comprehensive [92]. Research indicates that information quality plays a vital role in facilitating trust in online transactional contexts such as social e-commerce [44] and mobile food delivery apps [93]. When users perceive the information from WeChat Pay as high quality, it positions the platform as a competent and credible provider, thereby enhancing trust in WeChat Pay. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2a.

Perceived privacy positively affects perceived trust in WeChat Pay.

H2b.

Information quality positively affects perceived trust in WeChat Pay.

H2c.

Perceived security positively affects perceived trust in WeChat Pay.

Trust has been recognized as a significant factor influencing the use of information systems [94,95]. Scholars have increasingly integrated trust into TAM to provide a more comprehensive explanation of user behavior [78,96]. Empirical studies support the positive effect of trust on both perceived usefulness and ease of use. For example, Tandon et al. [97] confirmed that trust positively influences perceived usefulness and ease of use within the context of social media usage among tourists. Similarly, Sullivan and Kim [98] demonstrated the positive effect of trust on perceived usefulness in e-commerce, whereas Al-Hujran et al. [99] highlighted its positive impact on perceived ease of use in the adoption of e-government services. In the context of WeChat Pay, users with a higher level of trust are more willing to explore its features, which helps them perceive it as a fully functional and valuable platform. Moreover, users’ trust in the platform reduces their concerns and the need for monitoring and control, making payments effortless. Considering this, we propose the following proposition:

H3a.

Perceived trust positively affects the perceived usefulness of WeChat Pay.

H3b.

Perceived trust positively affects the perceived ease of use of WeChat Pay.

3.3. Direct and Indirect Network Externalities

When users depend on others to use an identical network product, direct network externalities are enhanced [59]. This indicates that the number of users affects direct network externalities [22], and an expanded perceived network yields wider benefits. In social networking services, a broader user base facilitates more frequent interactions and information sharing [100]. Growing adoption also drives continual product and service optimization, broadening available technologies, and improving functionality [22]. Most scholars view network size as a core dimension of direct network externalities [56]. Perceived network size reflects users’ beliefs that “many people are using the same mobile service” [101].

This perception acts as social proof, signaling that the platform is reliable and well-regarded. This reduces uncertainty and perceived risk when using WeChat Pay, thereby strengthening trust. Previous studies have demonstrated that network size positively influences perceived ease of use. Broader-perceived networks increase users’ sense of control over technology [61], which further enhances ease of use. Ghosh et al. [101] similarly argues that when a substantial number of users adopt the same mobile payment application, it becomes more usable for others. Evidence also links network size to perceived usefulness [102,103]. As the user base expands, the platform can leverage richer data to refine the services and infrastructure, resulting in greater functionality. This growth also encourages more merchants to join the ecosystem, expanding the range of WeChat Pay services and strengthening their overall utility. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H4a.

Perceived network size positively affects perceived trust in WeChat Pay.

H4b.

Perceived network size positively affects the perceived ease of use of WeChat Pay.

H4c.

Perceived network size positively affects the perceived usefulness of WeChat Pay.

Indirect network externalities occur if the networks could offer complementary products and services [22,104]. When a product or service is recognized as having such supplementary offerings, it generates greater benefits and induces a higher demand from users [54,105]. In other words, increased usage of compatible products enhances the value of complementary counterparts, thereby raising the overall utility of the original product or service [106]. Previous studies have identified perceived complementarity as a core dimension of indirect network externalities [57,107]. It describes users’ perceptions of congruity between an extended product and the main product in terms of their ability to satisfy their requirements.

WeChat Pay, as a payment tool embedded on the WeChat social platform, exhibits strong perceived complementarity. It was developed through the tight integration of services across the ecosystem, including social interaction, shopping, transport, and bill payments. This integration increases access to complementary services, amplifies network benefits, and supports their continued use. As WeChat expands its ecosystem, a broader scale and professionalism further strengthen trust in WeChat Pay. Chen and Li [108] reported that new applications and services in mobile social networks increase the availability of complementary goods, which enhances perceived usefulness. Zhang et al. [22] similarly demonstrated that integrating complementary services in a mobile payment platform raises the technology’s utility and promotes continued usage. When users perceive WeChat Pay as complementary to other services, the payment experience is seamless and integrated, which improves perceived ease of use. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H5a.

Perceived complementarity positively affects perceived trust in WeChat Pay.

H5b.

Perceived complementarity positively affects the perceived usefulness of WeChat Pay.

H5c.

Perceived complementarity positively affects the perceived ease of use of WeChat Pay.

3.4. Red Envelopes and Interface Design

While most studies on mobile payment technologies focus on cognitive and external factors [19,109,110], few studies have examined the application-specific features [4]. The red envelope function and interface design exemplify the unique characteristics of WeChat Pay. The red envelope feature gained instant success upon its launch [111] and has since been used to enhance social and emotional expression and build a larger ‘guanxi’ network. Interface design, which forms users’ first impressions of an application, plays a pivotal role in shaping the user experience [26]. In most cases, interface design factors positively influence the actual performance of user interaction [75,112]. These factors highlight the significance of WeChat Pay’s distinctive features and provide valuable insights for developers in designing and developing related technologies.

As a distinctive feature of WeChat Pay, red envelopes serve the dual purpose of social interaction and payment. The red envelopes make the virtual relationship real and strengthen real-life relationships. When set to “random,” sending red envelopes becomes a highly attractive and entertaining online social activity [113]. This randomness satisfies users’ curiosity and gaming mentality, enhancing enjoyment and participation. Furthermore, WeChat and merchants often use red envelopes as rewards in promotional campaigns [114], and such incentives are positively correlated with perceived usefulness [115]. Previous studies also highlight the role of red envelopes in promoting interpersonal connections and reinforcing social identity [66]. Mei and Deng [67] further suggests that WeChat red envelopes combine monetary incentives with social visibility, facilitating relationship-building and user participation within acquaintance networks. Notably, Wong et al. [68] confirmed that the gamification of red envelopes enhances users’ perceived usefulness and attitudes toward WeChat Pay. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H6a.

Red envelopes positively affect the perceived usefulness of WeChat Pay.

H6b.

Red envelopes positively affect attitude toward using WeChat Pay.

Interface design serves as another key attribute of WeChat Pay that influences user perception through both visual and interactive elements. The platform employs a cool-toned color scheme based on green and white, which not only ensures high recognizability but also helps reduce users’ visual fatigue and psychological stress [76]. Furthermore, WeChat Pay utilizes graphical symbols to represent functions, enabling users to intuitively understand and operate the interface and effectively minimizing the need for lengthy learning processes. Through numerous updates, WeChat Pay has continuously simplified its payment process and optimized its interface design. Existing studies indicate that users perceive interfaces to be easy to use when they are simple, straightforward, user-friendly, and efficient [116]. Park et al. [117] found that interface design elements can affect the perceived efficiency and overall satisfaction of users. Moreover, an attractive user interface can evoke positive emotions and higher-quality perceptions during use [118]. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H7a.

Interface design positively affects the perceived ease of use of WeChat Pay.

H7b.

Interface design positively affects attitude towards using WeChat Pay.

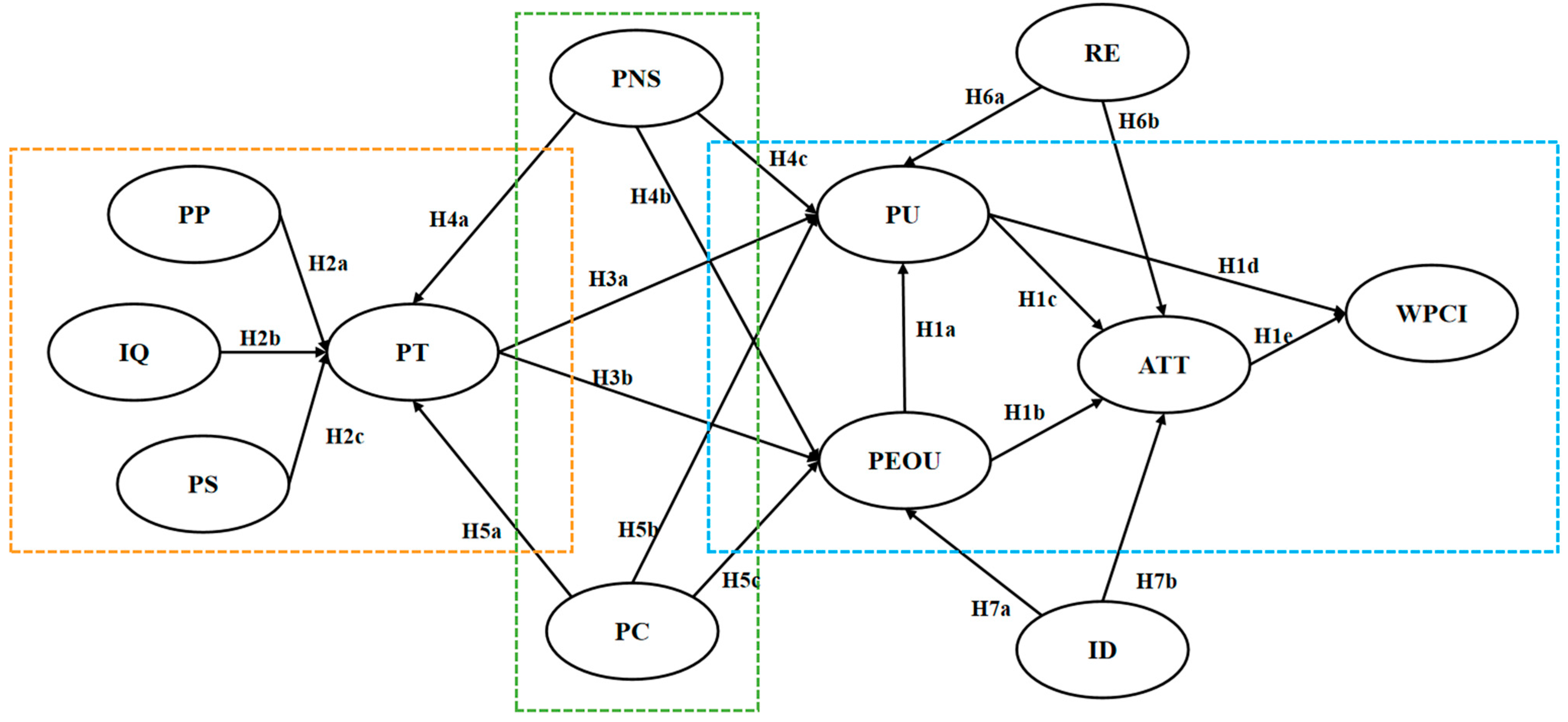

Based on the previous literature and proposed hypotheses, we developed our research conceptual model as follows (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research conceptual model. Note: PP = Perceived privacy; IQ = Information quality; PS = Perceived security; PT = Perceived trust; PNS = Perceived network size; PC = Perceived complementarity; RE = Red envelopes; ID = Interface design; PEOU = Perceived ease of use; PU = Perceived usefulness; ATT = Attitude; WPCI = WeChat Pay continuance intention.

4. Methodology

4.1. Measurements

A total of 60 items from 12 constructs were obtained, including perceived privacy—six items [49,86,119], information quality—six items [120,121], perceived security—four items [122], perceived trust—five items [123,124], perceived network size—four items [22,60], perceived complementarity—five items [22,61], red envelopes—four items [122], interface design—four items [71], perceived ease of use—six items [122,125], perceived usefulness—six items [125,126], attitude—four items [127,128], and WeChat Pay continuance intention—six items [22,129].

The questionnaire consists of two parts. The first part collected the respondents’ demographic information, including their gender, age, education level, usage time, frequency, and experience with both WeChat and WeChat Pay. The second part contained all the measurement items of the constructs of the study model. A seven-point Likert scale was used for all survey items, ranging from “strongly disagree” (one point) to “strongly agree” (seven points).

4.2. Sampling and Data Collection Procedures

Integrated within WeChat, China’s leading social platform, WeChat Pay supports instant payment on smartphones. It provides diverse payment options and social payment functions. This study focused on users in Mainland China who have prior experience using WeChat Pay.

This study was performed in two stages. The first stage was a pre-test to establish validity and ensure that the items measured the target constructs. The draft questionnaire underwent two rounds of evaluation. First, three graduate students were interviewed to review the questionnaire items and provide feedback. Revisions were made to improve clarity and comprehensibility. Second, forty marketing undergraduates completed the questionnaire and commented on each item. Their feedback indicated that the instructions and questions were well-understood.

The second stage involved the main survey. Respondents were recruited through Sojump, an established online Chinese survey platform with a large consumer panel [129,130]. The survey link was posted online, and only individuals with prior experience using WeChat Pay were eligible. A small monetary incentive was offered upon completion. Data were collected from November 2023 to February 2024, yielding 673 submissions with a mean completion time of approximately 20 min. Data quality screening excluded responses completed in less than 5 min, responses with identical scores across all items, and cases with substantial missing data. Twenty-three submissions were removed for inattentive or incomplete responses, leaving 650 valid cases for the analysis. The valid response rate was 96.6%.

4.3. Demographic Data

The respondents’ demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Among the 650 respondents, 58.5% were males and 41.5% were females. A total of 34% of the participants were aged 18–25 years, and 39.4% were aged 26–33 years, collectively accounting for 73.4% of the total sample. Most respondents were highly educated and held either undergraduate or graduate degrees. In terms of WeChat use, 72.1% of the participants reported using the platform for more than four years. Moreover, 70.4% used it more than nine times per day, and 61.1% spent more than 3 h daily. Regarding WeChat Pay, 72.5% used the service at least two to three times per day, and 65.1% reported more than three years of experience.

Table 1.

Demographics of Respondents.

5. Data Analysis and Results

We used partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to evaluate the research model, which allowed us to assess the measurement and structural components simultaneously [131]. Unlike covariance-based SEM, PLS-SEM does not assume multivariate normality and can accommodate complex models with relatively small sample sizes [132]. Given these advantages, PLS-SEM is well-suited for this study. The data were analyzed using SmartPLS 3.0.

5.1. Measurement Model

The reliability and validity of the measurement model were assessed. First, the reliability coefficient was calculated for the items of each construct. Following Chin’s [133] recommendation, the lower bound of Cronbach’s alpha was set to 0.7. Items that did not contribute significantly to reliability were eliminated. As illustrated in Table 2, the values of Cronbach’s α for all constructs exceeded 0.70, indicating good reliability.

Table 2.

Consistency and Reliability Test.

In terms of convergent validity, Bagozzi and Yi [134] proposed three measurement standards: (1) all indicator factor loadings should exceed 0.5, (2) composite reliability (CR) should exceed 0.7 [135], and (3) the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct should exceed 0.5. Following Hair et al. [131] and Kline [136], in structural equation modeling (SEM), particularly for higher-order models, the recommended minimum for outer factor loadings was set at 0.70. Applying this strict rule, we removed 20 items with loadings below 0.70. As presented in Table 2, the remaining 40 items were retained for analysis, and all outer loadings were significant at above 0.70. Table 2 also indicates that CR for all constructs exceeded 0.83, surpassing the 0.70 benchmark. Furthermore, the AVE for all constructs was greater than 0.50, thus supporting adequate convergent validity.

The discriminant validity of the measurement model was assessed using two established criteria. First, the Fornell-Larcker criterion was employed by comparing the square root of the AVE for each construct with its correlations with all other constructs. As depicted in Table 3, the square root of the AVE for each construct was greater than its highest correlation with any other construct, indicating good discriminant validity.

Table 3.

Discriminant Validity of Constructs: Fornell-Larcker.

Second, the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) was calculated as an additional test. HTMT statistic is defined as the ratio of the average correlation of items measuring different constructs to the geometric mean of the average correlation of items measuring the same construct. Discriminant validity is supported when the HTMT estimate is below the threshold of 0.9. As displayed in Table 4, the largest HTMT value in the matrix was 0.876, which is below the 0.9 threshold, further confirming that the model possesses good discriminant validity [137,138].

Table 4.

Discriminant Validity of Constructs: HTMT.

5.2. Structural Model

The bootstrap resampling method with 5000 iterations was employed to examine the significance of the path coefficients. SEM results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Hypothesis testing results.

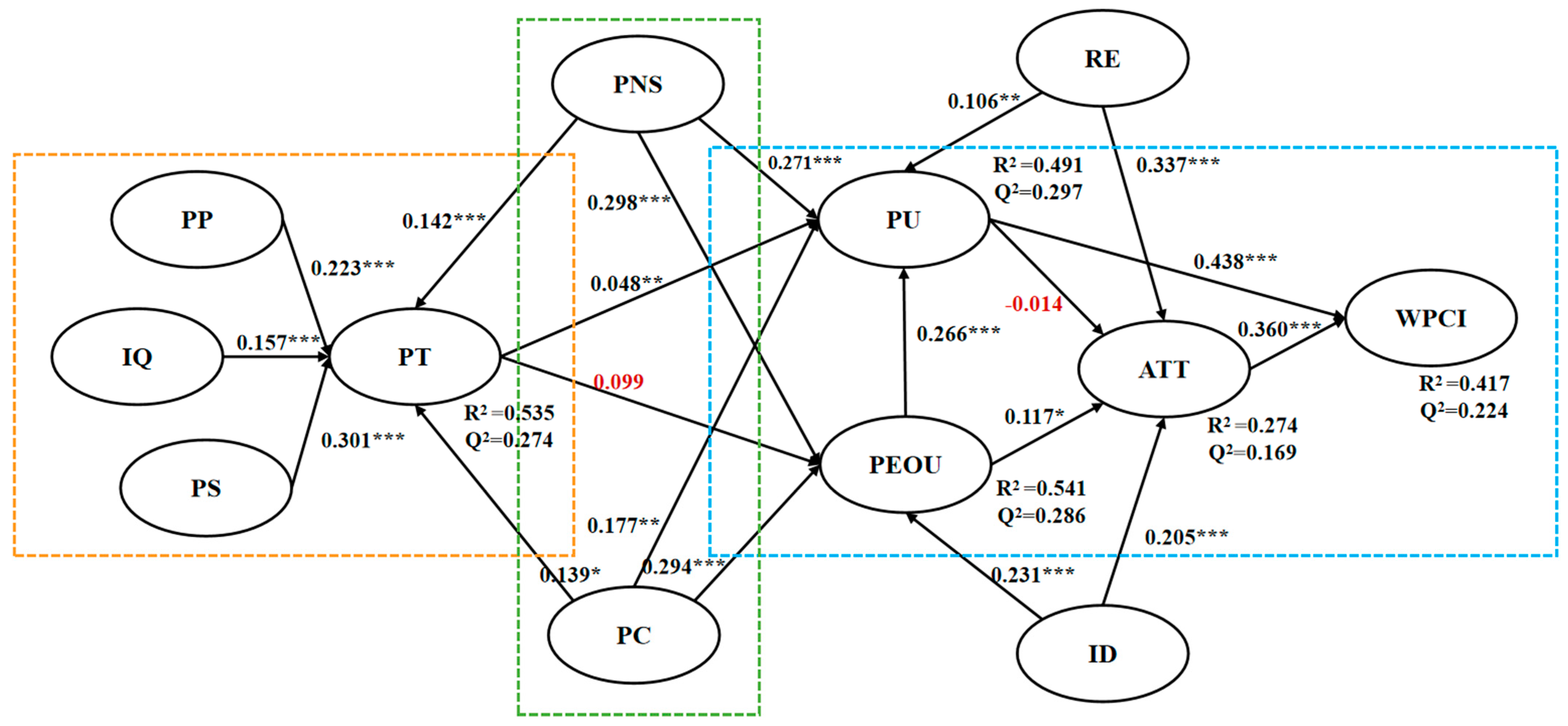

The analysis of TAM factors revealed that perceived ease of use significantly influenced perceived usefulness (t = 5.711, p < 0.001) and attitude (t = 2.392, p < 0.05). Both perceived usefulness (t = 12.305, p < 0.001) and attitude (t = 10.502, p < 0.001) positively influenced WeChat Pay continuance intentions. Therefore, H1a, H1b, H1d, and H1e were supported. However, because the effect of perceived usefulness on attitude was not significant (t = 0.303, p > 0.05), H1c was not supported. Perceived privacy (t = 4.603, p < 0.001), information quality (t = 3.840, p < 0.001), and perceived security (t = 6.300, p < 0.001) all exhibited significant positive effects on perceived trust, thus supporting H2. While perceived trust positively influenced perceived ease of use (t = 2.565, p < 0.01), supporting H3b, its effect on perceived usefulness was not significant (t = 1.263, p > 0.05). Thus, H3a was not supported. Regarding network externalities, perceived network size significantly influenced perceived trust (t = 3.342, p < 0.001), perceived ease of use (t =7.507, p < 0.001), and perceived usefulness (t = 6.001, p < 0.001), thus supporting H4. Similarly, perceived complementarity positively influenced perceived trust (t = 2.527, p < 0.05), perceived usefulness (t = 3.074, p < 0.01), and perceived ease of use (t = 6.371, p < 0.001), thus supporting H5. In terms of platform features, red envelopes positively influenced perceived usefulness (t = 2.828, p < 0.01) and attitude (t = 8.012, p < 0.001), supporting H6. Interface design positively influenced perceived ease of use (t = 5.643, p < 0.001) and attitude (t = 4.300, p < 0.001), confirming H7. Figure 2 presents the path coefficients and the significance of each path succinctly.

Figure 2.

Results of structural modeling analysis. Note: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; red highlights non-significant results. PP = Perceived privacy; IQ = Information quality; PS = Perceived security; PT = Perceived trust; PNS = Perceived network size; PC = Perceived complementarity; RE = Red envelopes; ID = Interface design; PEOU = Perceived ease of use; PU = Perceived usefulness; ATT = Attitude; WPCI = WeChat Pay continuance intention.

The predictive accuracy of the structural model was assessed using the coefficient of determination (R2). According to Chin [133], R2 values of 0.19, 0.33, and 0.67 represent weak, moderate, and strong explanatory power, respectively. In this study, the model explained 27.4% of the variance in attitude, 54.1% in perceived ease of use, 49.1% in perceived usefulness, 53.5% in perceived trust, and 41.7% in WeChat Pay continuance intentions. Moreover, the Q2 for all constructs was >0, which verifies the predictive relevance of all endogenous constructs in the structural model. Collectively, the demonstrated explanatory power and relevance substantiate the predictive validity of the model [139].

Furthermore, the goodness of fit (GOF) was computed following Tenenhaus et al. [140] to evaluate the overall quality of the proposed model. GOF integrates the performance of measurement and structural models and is calculated as follows:

The obtained GOF value exceeded the cut-off criterion 0.36 for a large effect size, thereby confirming the model’s strong global fit.

5.3. Common Method Variance

This study collected data using self-reported surveys in a single method, which may suffer from a potential common method bias (CMB) threat [141]. First, we used Harman’s single-factor test to assess CMB. The results indicate that no single factor accounted for most of the covariance among the variables. The maximum covariance explained by one factor was 31.6%, which was below the 40% cut-off value [142], indicating that the results may not be contaminated by CMB. Moreover, this study employed the rigorous approach suggested by Kock [143] to test CMB by performing a full collinearity assessment. All variance inflation factors (VIF) were below 3.3, indicating that common method bias was not a grave concern in this study [143].

6. Discussion

This study investigated the determinants of continuance intention toward WeChat Pay by developing an extended TAM framework that incorporates trust, network externalities, and application-specific features. The results indicate the strong explanatory power of the proposed model, with most hypotheses being supported. First, the relationships among the core TAM constructs were examined in the context of continued WeChat Pay usage. The findings demonstrate that perceived ease of use significantly enhances both perceived usefulness and attitude, which aligns with the findings of previous studies [78,80]. An important and unexpected result is the non-significant effect of perceived usefulness on attitude, which departs from the traditional TAM. This departure may reflect WeChat Pay’s deep integration into daily life. Users no longer treat it as a technology to be evaluated but as a taken-for-granted utility. In this mature stage, usage appears to be driven more by immediate functional values and automated routines than by attitude as a mediator. Nevertheless, both perceived usefulness and attitude exhibited significant positive effects on continuance intention. Thus, although the perceived usefulness–to–attitude pathway is attenuated, TAM retains its core predictive power for WeChat Pay continuance intention.

Second, this study examined the antecedents of trust and its impact on the core constructs of TAM. The results indicate that perceived privacy, information quality, and perceived security significantly influence perceived trust. These findings integrate and confirm the roles of the key antecedents identified in prior studies [44,49,50,51]. WeChat Pay’s comprehensive privacy protocols, secure transactions, and high-quality information help to reduce uncertainty and risk in financial transactions, thereby instilling greater user trust. Prior studies have incorporated trust into TAM frameworks [144,145]. However, this study specifically examined its impact on the model’s two core constructs. In line with Al-Hujran et al. [99], perceived trust significantly enhances perceived ease of use. However, its effect on perceived usefulness is not significant, in contrast to findings in e-commerce contexts [98]. This non-significant association may reflect participants’ prior experience with WeChat Pay. Experienced users have a high baseline of trust, which weakens the effect of trust on perceived usefulness. With long-term, routine adoption in China, usefulness becomes assumed rather than appraised.

Third, this study demonstrates the significant role of network externalities in driving users’ continuance intention toward WeChat Pay. Given the established effect of network externalities on technology adoption and usage [22,52], this study distinguishes between direct and indirect network externalities by employing perceived network size and complementarity as representative variables. Scholars have posited a strong association between perceived network size and both perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use [101,103]. Our findings reinforce the proposed relationships between these constructs. A larger network increases the utility and convenience by expanding the pool of potential transaction partners and use cases. Perceived complementarity positively influences perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, indicating that deeper integration of payment services into a user’s digital ecosystem enhances practical value and usability. Perceived network size and complementarity are also positively related to trust, suggesting that these extrinsic drivers meaningfully shape trust formation.

Fourth, this study innovatively incorporates two application-specific features, red envelopes and interface design, to examine their effects on continuance intention. Both features clearly promote the continued use of WeChat Pay. Red envelopes significantly enhance the perceived usefulness and user attitudes. They carry strong traditional cultural significance [64,67], and their integration into WeChat satisfies social interaction needs, thereby increasing the platform’s appeal. This feature also functions as a frequent reward, consistent with the established link between rewards and perceived usefulness [115]. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of interface design for the user experience [72]. Our results demonstrated that interface design is significantly correlated with both perceived ease of use and attitudes, corroborating the findings of [117,118]. Compared with other factors, interface design creates an immediate impression. The distinctive green-and-white color scheme and intuitive icons reduced operational complexity, increased perceived ease of use, and facilitated more positive attitudes.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical Implications

This study presents several important theoretical implications. First, this study extends TAM to investigate mobile payment continuance intentions. While previous studies have employed TAM to examine the usage intention of mobile payments, studies on the mechanisms influencing continuance intention, particularly in the context of WeChat Pay, are still insufficient. Given the unique context of WeChat Pay embedded within a social media platform, this study expands TAM by incorporating trust, network externalities, and application-specific features. The findings of this study confirm that perceived usefulness, ease of use, and attitude serve as significant mediators, elucidating how cognitive, external, and application-specific factors jointly shape continuance intentions. To further enrich the model, this study investigated the antecedents of trust and examined the impact of both cognitive and technical factors on trust formation. Overall, this study expands TAM and demonstrates its strengthened explanatory power in the context of social media-based mobile payments, offering more comprehensive insights into the continuance intention of mobile payment users.

Second, this study advances the application of the network externality theory in mobile payment research. Unlike previous studies that focused solely on social media [61,103] or general mobile payment systems [25,58], we innovatively applied this theory to social media-based mobile payment environments. By distinguishing between direct network externalities (represented by perceived network size) and indirect network externalities (represented by perceived complementarity), this study offers a more refined understanding of the influence of network externalities on users’ continuance intention. The findings reveal that both perceived network size and perceived complementarity not only enhance perceived usefulness and ease of use but also strengthen perceived trust. These results confirm that the advantages of network externalities are pronounced and that these variables effectively explain how external factors shape continuance intention. Overall, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of the structural dimensions of network externalities and provides insight into how network effects promote the continued use of mobile payments.

Third, this study establishes application-specific features as novel determinants of mobile payment continuance intentions. Existing studies have primarily focused on external and cognitive factors influencing mobile payment usage intentions [109,110], overlooking the inherent features of the applications themselves. This study highlights two key application features that influence the continuance intention toward WeChat Pay: red envelopes and interface design. The red envelope leverages WeChat’s embedded robust social network, demonstrating the value of integrating social interaction into mobile payments. This study indicates that red envelopes are a critical factor in enhancing users’ perceived usefulness and attitude. Another unique feature is the interface design, and this study analyzes it through intuitive visual elements such as colors and graphics. The findings indicate that a well-designed interface increases perceived ease of use and facilitates positive user attitude, offering initial insights into the role of interface design in continuance intention. Consequently, scholars should conduct in-depth research on application-specific features and align them with actual user needs to better understand users’ behavioral intentions.

7.2. Practical Implications

Our findings provide several actionable guidelines for the operators and developers of mobile payment platforms. First, understanding the antecedents of perceived trust and how they act can guide strategies. Perceived privacy is central to the formation of trust. In response to rising concerns, platforms should strengthen their privacy policies, make them effective in practice, and provide users with more choices over data protection. Perceived security is equally important. Developers should upgrade security systems on a continual basis and enhance secure payment features by adopting advanced encryption and multi-factor authentication to maintain a safe transaction environment. Information quality is also a key predictor of trust. Platform content should be accurate, clear, timely, and easy to understand to raise users’ trust. Finally, because perceived trust increases perceived ease of use but not perceived usefulness, operators should optimize trust-relevant interactions by streamlining tasks and offering clear progress feedback to improve ease of use.

Second, network externalities play a pivotal role in the post-adoption stage. They strengthen positive perceptions and help to retain users. Operators should distinguish between direct and indirect network effects to tailor interventions. The perceived network size often influences continued use. To expand the actual network, operators can partner with more merchants under high-frequency scenarios and offer targeted incentives to attract users. They can also increase the perceived network size by displaying the daily user counts in prominent locations within the app. To achieve perceived complementarity, developers should build a broad set of supporting tools and services that make the payment function indispensable in specific contexts. They should actively integrate public services and e-commerce ecosystems to create a coherent service environment.

Third, demonstrating the links between application-specific features and continuance intention can help inform product updates. The red envelope feature of WeChat Pay blends cultural traditions with social interaction. This demonstrates that mobile payments should extend beyond transactions and be embedded in everyday social and consumption routines. The element of randomness creates a playful experience that encourages continued use. Developers should therefore ground feature design in user experience and emphasize entertainment value where appropriate. As mobile payments replace cash in time-sensitive settings, users prefer simple and intuitive actions with rapid access to required information. Interfaces should remain straightforward, easy to navigate, and have low visual strain. Generally, developers should attend to the role of platform-specific features in the post-adoption phase, continually refine functionality, and enrich the total product experience.

7.3. Limitations and Future Work

This study offers theoretical and practical contributions, although several limitations and directions for future research remain. First, our sample was collected entirely from China owing to practical constraints. WeChat Pay has gained traction in Southeast Asia and other regions of the world. Cultural differences may limit the generalizability of the determinants of continuance intention. Future studies should validate and extend these findings to other cultural settings. We also prioritized broad applicability; therefore, the sample spanned a wide age range. Targeted sampling could examine specific cohorts, such as Generation Z or older adults, to clarify subgroup dynamics.

Second, although the two application-specific features analyzed are representative, WeChat Pay includes many additional functions and services. WeChat has evolved into a super app that integrates social networking, communication, payment, content, and services. Within this ecosystem, WeChat Pay extends beyond basic transactions and is embedded in everyday social and consumption routines. As its capabilities expand, the influence of the newly introduced features on continuance intention remains uncertain. Future research should investigate other distinctive features to provide a more comprehensive account of their continued use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H. and W.Y.; methodology, Y.H. and M.W.; software, Y.H.; validation, Y.H. and M.W.; formal analysis, Y.H.; investigation, Y.H. and W.Y.; resources, Y.H.; data curation, M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H., M.W. and W.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.H. and M.W.; visualization, Y.H.; supervision, Y.H.; project administration, Y.H.; funding acquisition, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Beijing Municipal Social Science Foundation [Grant No. 22GLC047].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it did not involve any interventions or procedures that required ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all individuals who provided informal advice, encouragement, or practical assistance throughout the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Mu, H.L.; Lee, Y.C. Examining the influencing factors of third-party mobile payment adoption: A comparative study of Alipay and WeChat pay. J. Inf. Syst. 2017, 26, 257–294. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.Y.; Li, Y. Analysis of the development process of payment methods and mobile payment technology diffusion trend in china. Technol. Invest. 2020, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dahlberg, T.; Mallat, N.; Ondrus, J.; Żmijewska, A. Past, present and future of mobile payments research: A literature review. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2008, 7, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, X.; Lu, Y.; Shi, D.; Deng, W. Understanding the continuous usage of mobile payment integrated into social media platform: The case of WeChat Pay. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 60, 101275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dewitte, S. A replication study of the credit card effect on spending behavior and an extension to mobile payments. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Akram, U.; Khan, Y.; Khan, N.R.; Hameed, I. Exploring consumer mobile payment innovations: An investigation into the relationship between coping theory factors, individual motivations, social influence and word of mouth. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSM Association. The State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money. 1–84. Available online: http://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-for-development/grma_resources/state-of-the-industry-report-on-mobile-money-2023-2/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Tencent. Financial Report for the Third Quarter of 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.tencent.com/zh-hk/investors/financial-reports.html (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Forward Industry Research Institute. Analysis of the Competitive Landscape and Market Share of China’s Mobile Payment Industry in 2024: High Market Concentration. Qianzhan. 2024. Available online: https://bg.qianzhan.com/trends/detail/506/240417-7adf968d.html (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Qu, Y.; Rong, W.; Chen, H.; Ouyang, Y.; Xiong, Z. Influencing factors analysis for a social network web based payment service in china. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018, 13, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Pham, V.K.; Duong, N.T. Why do users adopt mobile payment? An integrated model. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 4364–4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, B.; Oliveira, T.; Tam, C. Wearable technology: What explains continuance intention in smartwatches? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, H.; Thavisay, T.; Lee, S.H. Enhancing the role of flow experience in social media usage and its impact on shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armah, A.K.; Li, J. Generational cohorts’ social media acceptance as a delivery tool in sub-Sahara Africa motorcycle industry: The role of cohort technical know-how in technology acceptance. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A.; Troise, C.; Kozak, M. Functionality and usability features of ubiquitous mobile technologies: The acceptance of interactive travel apps. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2023, 14, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, D.; Kim, Y.; Park, M.H.; Kim, J.H. What motivates users to keep using social mobile payments? Sustainability 2020, 12, 6878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Liu, Y.L.; Yan, W. Should I scan my face? The influence of perceived value and trust on Chinese users’ intention to use facial recognition payment. Telemat. Inform. 2023, 78, 101951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Siddiqui, A.; Siddiqui, M.; Rana, N.P.; Dash, G. Mobile payment apps filling value gaps: Integrating consumption values with initial trust and customer involvement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Guo, Y. Antecedents of trust and continuance intention in mobile payment platforms: The moderating effect of gender. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 33, 100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.L.; Shapiro, C. Network externalities, competition, and compatibility. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 424–440. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.B.; Li, Y.N.; Wu, B.; Li, D.J. How WeChat can retain users: Roles of network externalities, social interaction ties, and perceived values in building continuance intention. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Yan, Y. Does network externality affect your project? Evidences from reward-based technology crowdfunding. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 180, 121667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ryu, M.H.; Lee, D. A study on the reciprocal relationship between user perception and retailer perception on platform-based mobile payment service. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 48, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Zhang, K.Z.K.; Chen, C.; Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, M.K.O. What drives self-disclosure in mobile payment applications? The effect of privacy assurance approaches, network externality, and technology complementarity. Inf. Technol. People 2020, 33, 1174–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Oh, C.; Kim, N.Y.; Choi, H.; Kim, B.; Ji, Y.G. Evaluating and eliciting design requirements for an improved user experience in live-streaming commerce interfaces. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 150, 107990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, D.; Fu, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Qu, X. A systematic review and meta-analysis of user acceptance of consumer-oriented health information technologies. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 104, 106147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamary, Y.H.S. Why do students adopt and use learning management systems? Insights from Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Kwon, K.H. Clicks intended: An integrated model for nuanced social feedback system uses on Facebook. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 39, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, N.; Khan, S.U.; Shaheen, I.; ALotaibi, F.A.; Alnfiai, M.M.; Arif, M. Chat-GPT; validating Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in education sector via ubiquitous learning mechanism. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 154, 108097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doleck, T.; Bazelais, P.; Lemay, D.J. Examining the antecedents of social networking sites use among CEGEP students. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2017, 22, 2103–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, M.A.; Zhang, W.; Sleiman, K.A.A. Factors affecting students’ intention to use m-learning: Extending the technology acceptance model (TAM). Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2024, 61, 1184–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Nah, S.; Makady, H.; McNealy, J. Understanding user attitudes towards AI-enabled technologies: An integrated model of Self-Efficacy, TAM, and AI Ethics. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 3053–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.M.; Dias, A.; Rodrigues, M.S. Continuity of use of food delivery apps: An integrated approach to the health belief model and the technology readiness and acceptance model. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Okaily, M. So what about the post-COVID-19 era?: Do users still adopt FinTech products? Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 876–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, T.; Balasubramanian, S.A.; Kasilingam, D.L. Understanding the intention to use mobile shopping applications and its influence on price sensitivity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 37, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.; Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N.P.; Raghavan, V. Understanding consumer adoption of mobile payment in India: Extending Meta-UTAUT model with personal innovativeness, anxiety, trust, and grievance redressal. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 54, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Chan, T.J.; Suki, N.M.; Kasim, M.A. Moderating role of perceived trust and perceived service quality on consumers’ use behavior of alipay e-wallet system: The perspectives of technology acceptance model and theory of planned behavior. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 2023, 5276406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. The effect of initial trust on user adoption of mobile payment. Inf. Dev. 2011, 27, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreen, M.; Ghazali, Z.; Mia, M.S. The impact of perceived risk and trust on adoption of mobile money services: An empirical study in Pakistan. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 347–355. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Wang, X.; Qu, H. The influence of peer-to-peer accommodation platforms’ green marketing on consumers’ pro-environmental behavioural intention. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 37, 976–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Tang, H.; Zhang, Y. Electronic word-of-mouth and consumer purchase intentions in social e-commerce. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2020, 41, 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Hiekkanen, K.; Dhir, A.; Nieminen, M. Impact of privacy, trust and user activity on intentions to share Facebook photos. J. Inf. Commun. Ethics Soc. 2016, 14, 364–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Herath, T.; De’, R.; Rao, H.R. Contextual facilitators and barriers influencing the continued use of mobile payment services in a developing country: Insights from adopters in India. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2020, 26, 394–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareef, M.A.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kumar, V.; Davies, G.; Rana, N.; Baabdullah, A. Purchase intention in an electronic commerce environment, a trade-off between controlling measures and operational performance. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 1345–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Han, I. The role of trust belief and its antecedents in a community-driven knowledge environment. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 1012–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, E.B.; Carvajal-Trujillo, E.; Escobar-Rodriguez, T. Influence of trust and perceived value on the intention to purchase travel online: Integrating the effects of assurance on trust antecedents. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqableh, M.; Hmoud, H.Y.; Jaradat, M.; Masa’deh, R. Integrating an information systems success model with perceived privacy, perceived security, and trust: The moderating role of Facebook addiction. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, A.G.; Harris, M.A.; Brookshire, R. An empirical investigation of intent to adopt mobile payment systems using a trust-based extended valence framework. Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 24, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, X.H.; Tan, S.C. What makes MOOC users persist in completing MOOCs? A perspective from network externalities and human factors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 85, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Khare, A. Influence of expectation confirmation, network externalities, and flow on use of mobile shopping apps. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 1449–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H. Do direct and indirect network externalities matter? Unpacking the causal antecedents of perceived gratifications and user loyalty toward mobile social media. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 76, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Li, M.; Zheng, J. Switching cost, network externality and platform competition. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 84, 428–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Li, H.; Liu, Y. Understanding mobile IM continuance usage from the perspectives of network externality and switching costs. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2015, 13, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.H.; Yu, C.K.; Chien, F.C. Enhancing effects of value co-creation in social commerce: Insights from network externalities, institution-based trust and resource-based perspectives. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2021, 41, 1755–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, H.; Abu-Shanab, E. Drivers of mobile payment acceptance: The impact of network externalities. Inf. Syst. Front. 2016, 18, 1021–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Lin, J.C.-C. An empirical examination of consumer adoption of Internet of Things services: Network externalities and concern for information privacy perspectives. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.Y.; Lu, H.P. Why people use social networking sites: An empirical study integrating network externalities and motivation theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1152–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lu, Y. Enhancing perceived interactivity through network externalities: An empirical study on micro-blogging service satisfaction and continuance intention. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 53, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matemba, E.D.; Li, G. Consumers’ willingness to adopt and use WeChat wallet: An empirical study in South Africa. Technol. Soc. 2018, 53, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yu, J.; Zo, H.; Choi, M. User acceptance of wearable devices: An extended perspective of perceived value. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.S. The “lucky money” that started it all-the reinventionof the ancient tradition “red packet” in digital times. Soc. Media + Soc. 2021, 7, 20563051211041643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.T.; Liu, X.Y.; Xiong, H.; Gong, H. A gateway toacquaintance community: Elderly migrants’ collective domesticationof interest-oriented group chats in China. New Media Soc. 2024, 26, 4390–4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.P.; Chen, L.; Chen, X. Identifying user relationshipon WeChat money-gifting network. IEEE Trans. Onknowl. Data Eng. 2022, 34, 3814–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Deng, N. Do Monetary Gifts Influence User Engagement on Social Media? An Empirical Study About Red Packets on the WeChat Interest-Based Groups. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.; Liu, H.F.; Meng-Lewis, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. Gamifiedmoney: Exploring the effectiveness of gamification in mobile paymentadoption among the silver generation in China. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 35, 281–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.F.; Ma, J.Q.; Wei, J.N.; Yang, S.Q. The role ofperceived integration in WeChat usages for seeking information andsharing comments: A social capital perspective. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Monetized socialization on the front end: Exchanging money as social activities through Red Packet and Transfer on WeChat. J. Cult. Econ. 2025, 18, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes, K.M.; Michael, M.; Ayon, C. Service quality assessment of Internet banking: Empirical evidences from Namibia. e-Serv. J. 2016, 10, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaatz, C. Retail in my pocket–replicating and extending the construct of service quality into the mobile commerce context. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.C.; Tai, K.H.; Hwang, M.Y.; Kuo, Y.C.; Chen, J.S. Internet cognitive failure relevant to users’ satisfaction with content and interface design to reflect continuance intention to use a government e-learning system. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J. Driving factors of post adoption behavior in mobile data services. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 1212–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, J. Do the Emotions Evoked by Interface Design Factors Affect the User’s Intention to Continue Using the Smartwatch? The Mediating Role of Quality Perceptions. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2022, 39, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.F.; Wu, C.S.; Leiner, B. The influence of user interface design on consumer perceptions: A cross-cultural comparison. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrab, M.; Elbasir, M.; Alnaeli, S. Towards a quality model of technical aspects for mobile learning services: An empirical investigation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wistedt, U. Consumer purchase intention toward POI-retailers in cross-border E-commerce: An integration of technology acceptance model and commitment-trust theory. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 104015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Adwan, A.S.; Li, N.; Al-Adwan, A.; Abbasi, G.A.; Albelbisi, N.A.; Habibi, A. Extending the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to Predict University Students’ Intentions to Use Metaverse-Based Learning Platforms. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 15381–15413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, M.D.; Kolog, E.A.; Boateng, R. Effect of gratification on user attitude and continuance use of mobile payment services: A developing country context. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2020, 22, 351–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laksamana, P.; Suharyanto, S.; Cahaya, Y.F. Determining factors of continuance intention in mobile payment: Fintech industry perspective. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 1699–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oghuma, A.P.; Libaque-Saenz, C.F.; Wong, S.F.; Chang, Y.W. An expectation-confirmation model of continuance intention to use mobile instant messaging. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.H.; Kim, D.J.; Hur, Y.; Park, K. An Empirical Study of the Impacts of Perceived Security and Knowledge on Continuous Intention to Use Mobile Fintech Payment Services. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2018, 35, 886–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, S.; Dhir, A.; Khalil, A.; Mohan, G.; Islam, A.N. Point of adoption and beyond. Initial trust and mobile-payment continuation intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, T.; Xu, H.; Smith, J.H.; Hart, P. Information privacy and correlates: An empirical attempt to bridge and distinguish privacy-related concepts. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2013, 22, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, M.J.; Babb, J.S.; Lowry, P.B.; Furner, C.P.; Abdullat, A. The role of mobile-computing self-efficacy in consumer information disclosure. Inf. Syst. J. 2015, 25, 637–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abumalloh, R.A.; Nilashi, M.; Halabi, O.; Ali, R. Does metaverse improve recommendations quality and customer trust? A user-centric evaluation framework based on the cognitive-affective-behavioural theory. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Shao, M.; Li, Y.; Huang, X. Understanding users’ attitude toward mobile payment use: A comparative study between China and the USA. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2018, 118, 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Tao, W.; Shin, N.; Kim, K.-S. An empirical study of customers’ perceptions of security and trust in e-payment systems. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilzadeh, J.; Ozturk, A.B.; Bilgihan, A. Security-related factors in extended UTAUT model for NFC based mobile payment in the restaurant industry. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 70, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stvilia, B.; Mon, L.; Yi, Y.J. A model for online consumer health information quality. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 1781–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.N.; Nguyen, N.A.N.; Nguyen, L.N.T.; Luu, T.T.; Nguyen-Phuoc, D.Q. Modeling consumers’ trust in mobile food delivery apps: Perspectives of technology acceptance model, mobile service quality and personalization-privacy theory. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2022, 31, 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Moon, J.; Kim, Y.J.; Yi, M.Y. Antecedents and consequences of mobile phone usability: Linking simplicity and interactivity to satisfaction, trust, and brand loyalty. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Hooda, A.; Jeyaraj, A.; Seddon, J.J.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Trust, risk, privacy and security in e-government use: Insights from a MASEM analysis. Inf. Syst. Front. 2025, 27, 1089–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, B.; Yaoyuneyong, G.; Pollitte, W.A.; Sullivan, P. Adopting retail technology in crises: Integrating TAM and prospect theory perspectives. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2023, 51, 939–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, U.; Ertz, M.; Bansal, H. Social vacation: Proposition of a model to understand tourists’ usage of social media for travel planning. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Y.W.; Kim, D.J. Assessing the effects of consumers’ product evaluations and trust on repurchase intention in e-commerce environments. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hujran, O.; Al-Debei, M.M.; Chatfield, A.; Migdadi, M. The imperative of influencing citizen attitude toward e-government adoption and use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 53, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.-T.; Chen, L.S.-L. Forming relationship commitments to online communities: The role of social motivations. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Mishra, R.; Mishra, A. Role of network externalities and trust facilitators in shaping mobile payment application continuance intentions: Variations across stages of adoption. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2025. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Deng, Z.; Wang, B. Exploring factors affecting Chinese consumers’ usage of short message service for personal communication. Inf. Syst. J. 2010, 20, 183–208. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.; Cheng, H.; Huang, H.; Chen, C. Exploring individuals’ subjective well-being and loyalty towards social network sites from the perspective of network externalities: The Facebook case. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Li, X.; Xia, Y.; Wang, M.; Sun, X. Technology acceptance model of mobile social media among Chinese college students. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2021, 6, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.; Saloner, G. Standardization, compatibility, and innovation. RAND J. Econ. 1985, 16, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-L.; Lin, S.-L. Determinants and consequences of social media apps usage: From the perspective of the value theory. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2022, 20, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Shao, B.; Chen, H. What influences users’ continuance intention of internet wealth management services? A perspective from network externalities and herding. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]