Abstract

With the significant increase in users’ privacy awareness and strict regulatory response, user privacy protection faces a dilemma between platform operational flexibility and commercial potential. The personal data use authorization has become an important mechanism influencing platform data transactions and government regulation, thereby shaping the development trajectory of the data trading market. Previous literature has yet to fully elucidate the complex interactions and evolutionary equilibrium strategies among the parties involved in data transactions. This study builds an evolutionary game model involving three parties—users, platforms, and the government—to explore the evolutionary equilibrium of users’ personal data use authorization strategy, platforms’ data trading strategy, and the government’s regulatory strategy. The findings reveal that: (1) User authorization does not always promote platform data transactions. Under the personal data use authorization mechanism, user authorization facilitates platform data transactions only when either the data transaction price is low and the value of user behavioral data exceeds a certain threshold, or the data transaction price is high and the value of user behavioral data falls within a specific range. (2) User authorization is not a sufficient condition for the government to impose strict regulatory measures on platform data transactions. When the regulatory cost is low, the government’s strict regulatory strategy is influenced by both the data transaction price and the value of user behavioral data. Specifically, under low-price–medium-value or high-price–high-value conditions, the government tends to strictly regulate platform data transactions when users do not authorize the use of personal data. Conversely, under low-price–high-value or high-price–medium-value conditions, the government is more inclined to enforce strict regulation when users authorize the use of personal data. This study contributes to evaluating the role of the personal data use authorization mechanism, offering valuable insights to platforms and the government on data transactions and regulation.

1. Introduction

As with most two-sided markets, platforms continuously accumulate data resources by connecting different user groups. These data resources help platforms gain deep insights into users’ needs and accurately predict market trends, as well as driving service optimization and product iteration. Currently, more and more platforms’ development strategies are evolving from “economies of scale” to “economies of scope”, with expanding into peripheral areas while consolidating their core markets. The demand for business diversification has directly led to an increase in platform data transactions. Data transactions refer to platforms exchanging or acquiring each other’s market user data based on data sharing or trading mechanisms. For example, Meituan and Baidu Maps, two leading Chinese enterprises in the local lifestyle services and online map services markets, respectively, are achieving mutual benefits through data transactions and sharing. Specifically, Meituan provides Baidu Maps with comprehensive data on local lifestyle service providers, including restaurants and entertainment venues, as well as user review data. This significantly enriches the map information and service content of Baidu Maps, enhancing its service quality and user experience. In return, Baidu Maps provides Meituan with precise geographical location and traffic flow data, which are crucial for optimizing logistics delivery routes and improving the accuracy of merchant recommendation algorithms. This model of platform data transactions enables the mutual exchange of resources among platforms, promoting the efficient utilization of data resources and fostering the synergistic development of inter-platform businesses. This injects new vitality into the prosperity of the digital economy.

However, obtaining user authorization for personal data is crucial during platform data transactions. As users’ awareness of data privacy protection has increased significantly, they are demanding greater control over their personal data and expecting transparency and informed consent during the collection and use of their data. China has recently issued several policy documents on data management, including the “Data Security Law of the People’s Republic of China”, the “Personal Information Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China”, and the “Electronic Commerce Law of the People’s Republic of China”. These regulations establish a normative framework for the collection, storage and transactions of data. They require platforms to strictly comply with legal provisions when conducting data transactions, strengthen user privacy protection and ensure the legality of data. Against this backdrop, platforms typically require users to read and agree to the data usage terms and conditions during registration, clarifying the scope of data use and potential sharing with third parties. Particularly, platforms commonly implement personal data authorization mechanisms, enabling users to access privacy settings and specify who can access their personal information. These privacy settings balance user authorization and data utilization, enabling users to control and manage their personal data. Under these mechanisms, platforms must obtain prior authorization from users when intending to trade or share their personal data.

While these mechanisms are effective in protecting user privacy and data security, they can also constrain platforms’ operational flexibility and limit their commercial potential, thereby undermining their capacity for service innovation and market expansion. In this context, exploring how user authorization impacts platform data transactions, thereby enriching data products and services and attracting more entities to participate in data transactions, is of great significance for promoting the development of the data transaction market. However, despite the growing discussion of data rights, existing research lacks a systematic theoretical framework with which to analyze the interactive mechanisms between the micro-level behaviors of users authorizing transactions and the transactions themselves. This hinders the provision of accurate assessments of the practical utility of user data ownership in market-based data allocation. At the regulatory policy level, an effective link between data ownership classification and differentiated regulatory strategies has yet to be established. Existing regulatory theories appear to be insufficiently adaptive when addressing complex ownership forms, such as the integration of personal and behavioral data. Additionally, similar studies on topics such as information/data protection policies and their impact on data transactions have primarily relied on static models, such as the Hotelling model, for analysis [1]. These models have yet to fully unravel the complex interactions and evolutionary equilibrium strategies among the parties involved. This study therefore examines users, platforms and the government operating under bounded rationality, whose strategic choices involve balancing dynamic data value against costs. The study focuses on two primary questions: (1) Under what specific conditions does user authorization facilitate or hinder platform data transactions? (2) How should government regulatory strategies be dynamically adjusted in response to the interplay of user authorization and platform decision? This study contributes by applying an evolutionary game framework to construct a tripartite model involving users, platforms, and the government in the context of data transactions. It analyses the dynamic evolution of user personal data authorization strategy, platform data transaction strategy and government regulatory strategy, exploring the evolutionary logic of tripartite strategy selection under user authorization mechanisms.

2. Literature Review

In recent years, data transactions and regulatory issues on platforms have become a hot topic of academic research. This study reviews the related literature primarily from the perspectives of data characteristics and value, data transactions, and the regulation of data transactions.

2.1. Research on Data Characteristics and Value

“Data” can be regarded as the portion of “information” that does not constitute “thought” or “knowledge” [2]. The same dataset can be used simultaneously by multiple enterprises or individuals [3]. Data possesses characteristics such as non-rivalry [4], non-excludability [5], uncertainty regarding data rights [6] and network externalities [7]. There is no absolute optimal solution regarding whether individuals or enterprises should hold data ownership, as this depends on several key factors [8,9]. The significant value of data manifests in several aspects: First, the development and application of data have shifted corporate decision-making from experience-driven to “data-driven decision-making,” substantially enhancing corporate revenue and competitive advantage [10,11,12,13]. Second, data boosts productivity and efficiency. Leveraging data for innovation facilitates the production of final goods in key economic sectors, e.g., agriculture [14,15], thereby driving economic growth [16]. Supported by digital technologies, modern enterprises can access vast amounts of data and utilize it to pursue various competitive advantages [17]. Third, data influences platform pricing behavior [18], enabling decision-makers to design personalized pricing algorithms based on existing data [19,20,21].

2.2. Research on Data Transactions

Current research on data transactions primarily focuses on the following aspects: First, facilitating data transactions is a crucial step in establishing and improving data factor markets while unlocking the potential of data as a production factor. Data sharing leverages the non-rivalrous nature of data, enabling more enterprises to utilize open data for technological research, development, and innovation [22]. Transaction markets promote the circulation of innovative ideas, enhance corporate productivity, and stimulate economic growth [23]. Second, regarding data transactions and pricing, data transaction pricing is influenced by the consistency between individual privacy considerations and rational preferences [24]. Pricing data elements requires specific transaction contexts and necessitates targeted valuation of data element value based on typical application scenarios [25,26,27]. Depending on the situation, this can be categorized as traditional accounting pricing [28], or multidimensional pricing of data asset value [29]. Data transactions and welfare can be maximized through logarithmic pricing functions [30]. Third, data markets play a crucial role in facilitating data circulation [31]. As data trading evolves, several challenges emerge: (1) Data-holding companies resist sharing data [32,33]. Despite the benefits of data circulation, firms often conceal data to maintain competitive advantages, creating data silos that severely hinder the realization of its economic value [2]. (2) Data ownership remains ambiguous. Johnson et al. note that strong property rights may lead to insufficient data sharing, harming consumers and advertisers, and propose reallocating property rights to consumers [34]. (3) Balancing “data security” and “data circulation” poses challenges. The negative externalities of data privacy may trigger “excessive data sharing,” creating a paradox where both data security and circulation cannot be simultaneously achieved in data transactions [35,36,37]. Sharing may compromise “data security”, highlighting the potential conflict between “data security” and “data circulation” [38,39,40], necessitating a balance between the two [41]. (4) Information asymmetry exists during data transactions [42]. Sellers hold an informational advantage regarding data quality, sources, and compliance, while buyers possess greater clarity about their intended use and the data’s ultimate value. This mutual uncertainty forms the tension in data transactions. In emerging data markets characterized by information asymmetry, trust is the key factor that facilitates transactional cooperation [43].

2.3. Research on the Regulation of Data Transactions

On one hand, some scholars have emphasized the necessity of data transaction regulation. Wang argues that the effectiveness of government data privacy legislation and the brand image of online enterprises positively influence trust in online businesses [44]. Sun et al. contend that personal data has become a vital resource for platform enterprises, discussing the potential economic impact of government data regulation on platforms and the role of personal data in fostering value creation and innovation [45]. Kang et al. contend that privacy regulation can increase users’ willingness to share personal data by strengthening their psychological ownership of such data and alleviating privacy concerns [46]. Marikyan argues that legal mechanisms must be introduced to safeguard the privacy and security of data exchanged between individuals and organizations [47]. On the other hand, some scholars have pointed out the possible negative effects caused by data transaction regulation. For example, data regulations in China, Europe, and the United States restrict internet platforms’ ability to collect and use personal data for personalized recommendation and may fundamentally impact internet commerce [45].

2.4. Identified Gaps and Research Contributions

A systematic review of extant literature reveals the following areas that merit attention to enhance the quality of current research: Firstly, despite the increasing academic exploration of data property rights, no systematic theoretical framework has yet been established to address the interactive relationship between user data authorization mechanisms and platform data transactions. The extant research has focused predominantly on the legal attributes of data rights confirmation, overlooking the impact of micro-level user authorization behaviors on platform data transactions. This oversight impedes the precise evaluation of the practical efficacy of user data ownership in the market-based allocation of data as a factor of production. Secondly, at the level of regulatory policy, extant literature predominantly accentuates the institutional functions of government regulation, yet it fails to establish a nexus between data ownership classifications and regulatory strategy selection. This limitation hinders the capacity of extant research to furnish an efficacious analytical framework for formulating diversified regulatory approaches. This is particularly evident in the context of addressing complex data ownership forms in the platform economy, such as the blending of personal and behavioral data. Current regulatory theories demonstrate an inadequate degree of adaptability in such situations.

Based on related work on data ownership confirmation, such as the work by Mahajan [48] and Li [49], the present study proposes a tripartite evolutionary game model encompassing users, platforms, and the government. By analyzing the dynamic evolution of strategic equilibria among user authorization behaviors, platform data transaction decisions, and government regulatory measures under a user data authorization mechanism, this study explores how the interaction between user authorization behaviors and government regulatory policies shapes and influences platform data transaction decisions. The objective of this research is to establish the theoretical underpinnings for platforms and governments in the context of data transactions and their regulation.

3. Evolutionary Game Model Description and Assumptions

3.1. Evolutionary Game Model

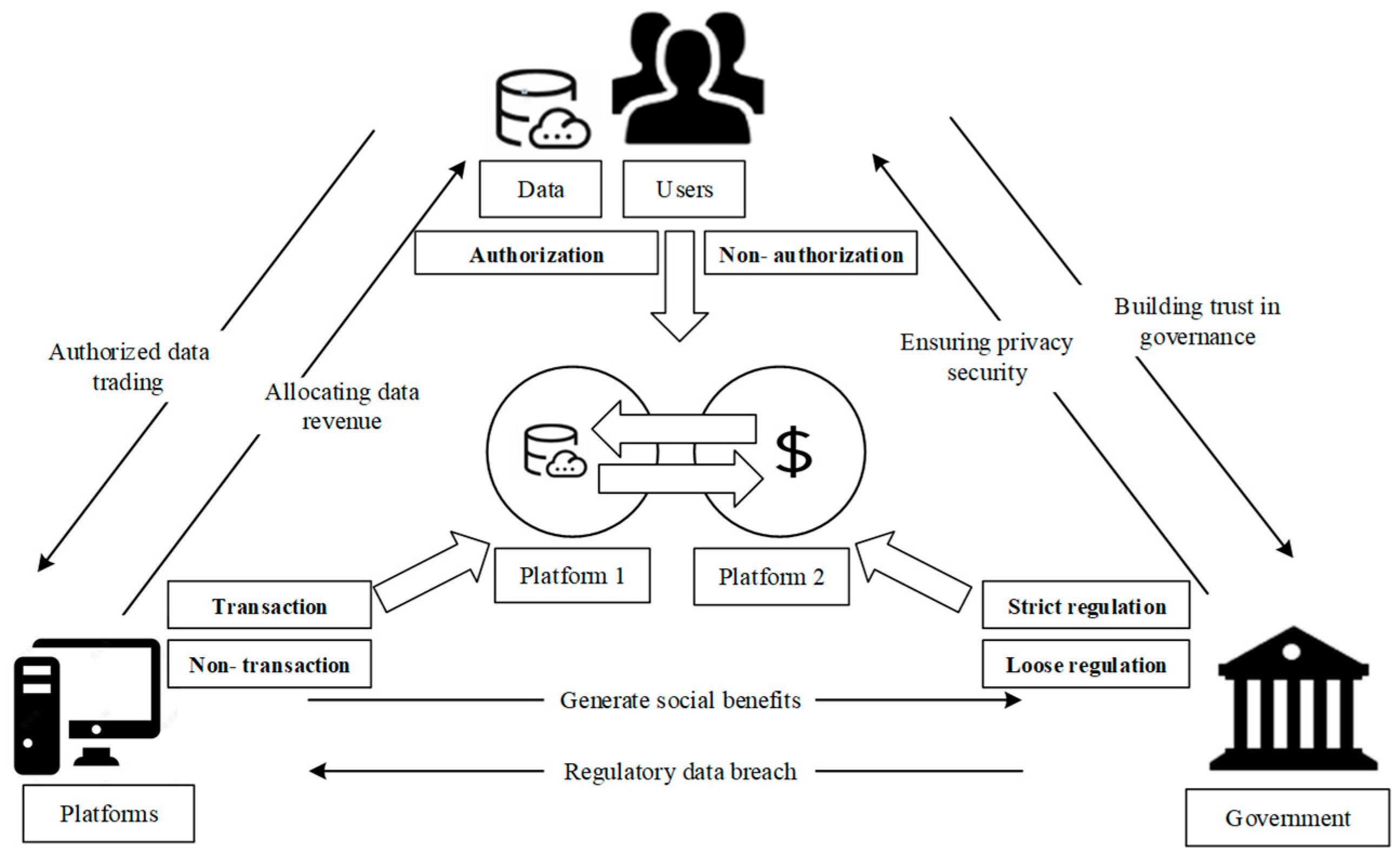

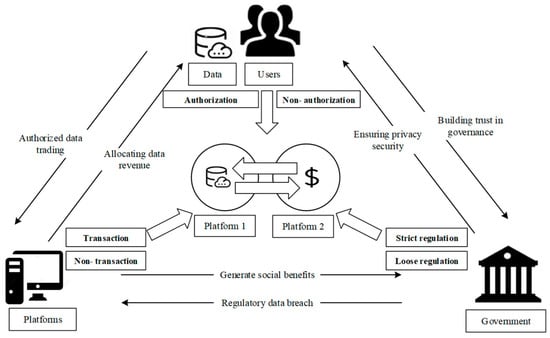

Data transactions involve three key parties: the government, platforms, and users. Each party acts with bounded rationality and possesses its own strategy space. The game relationships among these three parties are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Tripartite game involving users, platforms, and the government.

For government, two regulatory strategies are available: strict regulation or loose regulation. Under strict regulation, platform data transactions are effectively regulated and supervised, ensuring user data security. However, the government must bear the associated regulatory costs. In the presence of loose regulation, transactions involving platform data are prone to inadequate regulation, which can lead to significant risks, including data security breaches. As a result, the government is often compelled to bear the consequences of reputational damage caused by data leaks. For platforms, two strategic options are available: the first is to engage in data transactions, and the second is to not engage in such transactions. Engaging in data transactions enables platforms to generate substantial profits by selling user data or data analysis services, thereby improving products and services. However, engaging in data transactions entails the risk of data leaks post-transaction. Not engaging in data transactions, on the one hand, serves to mitigate the risk of user privacy data leaks, thereby enhancing the platform’s brand image. However, this practice also hinders the extraction and realization of data value. Two strategies are available to users: they may authorize or not authorize platforms to use their personal data. When users authorize such access, they potentially risk data breaches but in return gain access to customized product and service recommendations and a streamlined consumption experience. In instances where users do not authorize, their privacy and personal information are effectively protected; however, their service experience is compromised.

3.2. Assumptions

Assumptions 1.

All three parties in the evolutionary game possess bounded rationality. The strategic space of users is {Authorization, Non-authorization}, with respective probabilities of , ; the strategic space of platform is {Transaction, Non-transaction}, with probabilities of , ; the strategic space of government is {Strict regulation, Loose regulation}, with probabilities of , .

Assumptions 2.

Platform data resources comprise two categories: user personal data and user behavioral data [50]. User personal data includes individual information, browsing history, and bookmarked products or services. This data is individual-specific and can be used for precision marketing. User behavioral data is derived from processing and analyzing aggregate user behavior records, such as consumer psychological states, service preferences, and market trends. This data reflects general behavioral patterns of users, possesses group characteristics, and can be utilized for business opportunity forecasting and algorithm refinement. Both data types first generate value within the platform, termed internal value, denoted as and , respectively. This value manifests primarily through internal applications such as optimizing products and services, enhancing user experience, and improving operational efficiency. Greater internal value from these data resources yields increased benefits for both the platform and users. Let and represent the benefit coefficients derived by users and the platform, respectively, from the internal value of data resources.

Assumption 3.

A platform may choose to trade its accumulated data resources with other platforms, thereby generating data transaction value. Here, represents the price coefficient for data transactions, and represents the cost of data transactions. When users grant authorization, platforms can trade both personal data and behavioral data resources together, with a data leakage probability of . When users do not grant authorization, platforms can only trade behavioral data, with a data leakage probability of . Since data transfers and two-party storage are involved in platform data transactions when users grant authorization, the risk of data leakage is higher, so there is . Once data leakage occurs, the loss of user is set at .

Assumption 4.

From the societal perspective of developing and utilizing the value of data, the government can directly or indirectly derive benefits from platform data transactions. Specifically, when both user personal data and behavioral data are traded by platforms, the government benefit is ; when only behavioral data is traded by platforms, the government benefit is . Under strict government regulation, regulatory costs amount to . Users gain trust benefits of from enhanced data security. Simultaneously, if data breaches occur during platform transactions, government fines imposed on platforms total . Under loose regulation, the government incurs a reputational damage of upon data breaches.

Parameter symbols and their specific meanings are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Model symbols and their meanings.

3.3. Establishing the Revenue Matrix

Based on the above assumptions, the payoff matrices for each party in the three-party strategy evolution model involving the government, platforms, and users are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Evolutionary game payoff matrix.

4. Solving the Evolutionary Stabilization Strategy

4.1. Expected Payoff of Users

The expected payoff for users choosing the authorization strategy is , and the expected payoff for users choosing the non-authorization strategy is . Users’ expected payoff is . Therefore,

The replication dynamic equation of users is:

The first derivative of the replication dynamic equation is:

According to the stability theorem of the replicator dynamics equation, to achieve policy stability, conditions and must be satisfied. The corresponding point is then the stable point of the evolutionary game.

Letting yields:

Therefore, when , there is

,

, and

represents a stable point in the evolutionary game, at which users choose the authorization strategy; when

, there is

,

, and

represents a stable point in the evolutionary game, at which users choose the non-authorization strategy; when

, there is

, it indicates that all points on

are in a stable state, meaning users’ strategy does not change over time. This leads to the following proposition:

Proposition 1.

When , is users’ evolutionarily stable strategy; when , is users’ evolutionarily stable strategy; when , the stable strategy cannot be determined.

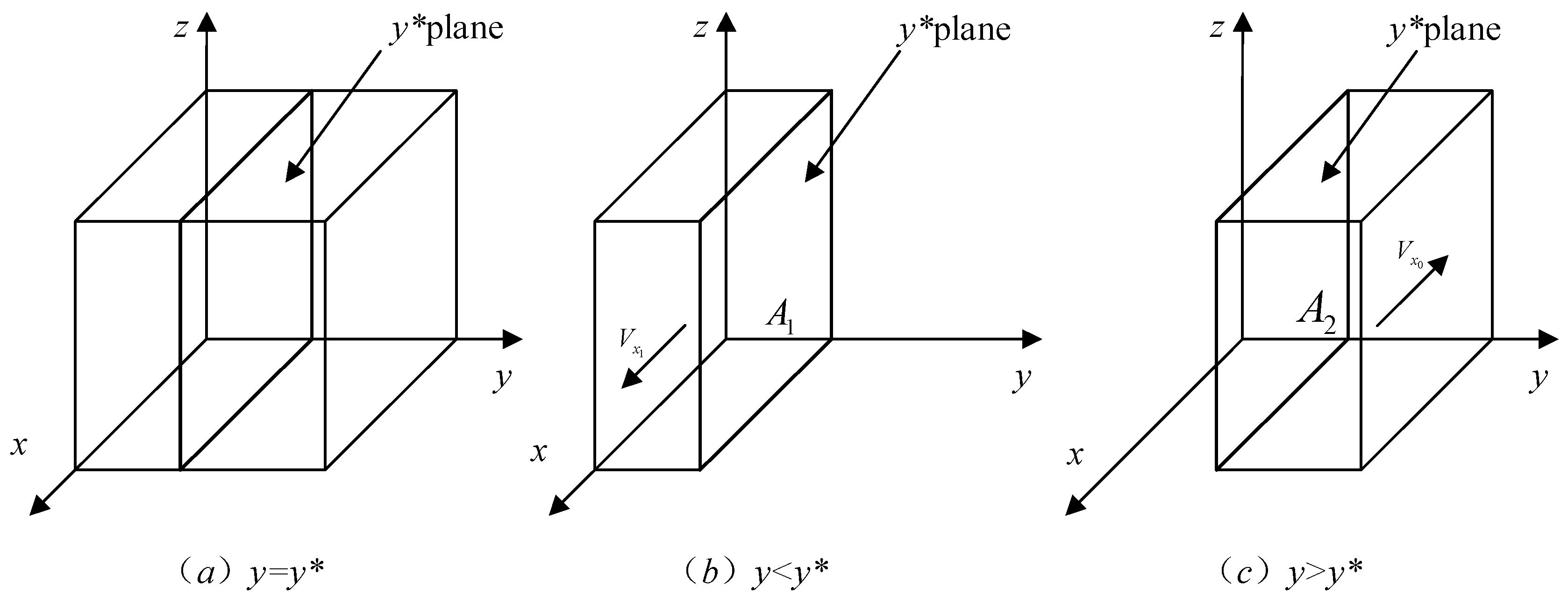

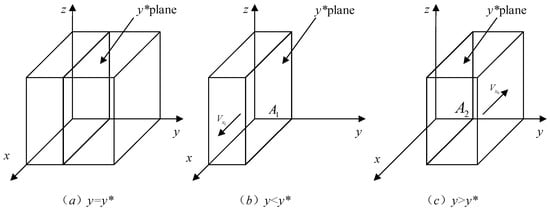

Proposition 1 indicates that, with other parameters constant, users’ strategy is influenced to some extent by platforms’ initial strategy probability. As platforms’ transaction probability increases, the probability of users’ authorization strategy decreases. Figure 2 shows the phase diagram of users’ strategy evolution dynamics.

Figure 2.

Dynamic phase diagram of users’ strategy evolution.

The first-order partial derivatives of each parameter yield the following results. When , there is , indicating that increases as increases; the plane moves along the positive direction of the axis. As a result, the volume of , which is the probability of user authorization, increases. When , there is , indicating that decreases as increases; the volume of decreases, indicating a reduced probability of authorization. Similarly, when , there is ; when , there is ; and , , , , . This leads to the following proposition:

Proposition 2.

Regarding the probability of users selecting the authorization strategy, when , it is positively correlated with ; when , it is positively correlated with . Additionally, it is positively correlated with , , and , but is negatively correlated with and .

Proposition 2 illustrates that users’ authorization decisions involve a trade-off between benefits and risks. Specifically, the greater the benefit coefficient users derive from data value, or the higher the price coefficient of data transactions, the greater their potential gains—thereby increasing their inclination to authorize. Conversely, the lower the probability of data leakage when not authorizing, or the higher the probability of leakage when authorizing coupled with greater losses to user benefits from such leakage, the greater the risks of authorization—thereby increasing users’ inclination to not authorize. Furthermore, only when the behavioral data value is high will users increasingly favor authorizing their personal data, since authorization allows them to gain more from platforms’ data transactions. However, when the data transaction price is high, users will increasingly favor not authorizing their personal data as the value of their behavioral data increases. This is because they can already obtain sufficient benefits from platforms’ behavioral data transactions, making them more inclined to not authorize.

4.2. Expected Payoff of Platforms

The expected payoff when platforms choose to engage in data transaction is , the expected payoff when platforms choose not to engage in data transaction is , and platforms’ expected payoff is . Therefore,

The replication dynamic equation of platforms is:

The first derivative of the replication dynamic equation is:

Letting yields:

Therefore, when , there is , , and is the equilibrium point of the evolutionary game, platforms adopt the non-transaction strategy at this point; when , there is , , and is the equilibrium point of the evolutionary game, at which platforms choose the transaction strategy; when , there is , it indicates that all points on are in a stable state, meaning platforms’ strategy does not change over time. This leads to the following proposition:

Proposition 3.

When , is platforms’ evolutionarily stable strategy; when , is platforms’ evolutionarily stable strategy; when , the stable strategy cannot be determined.

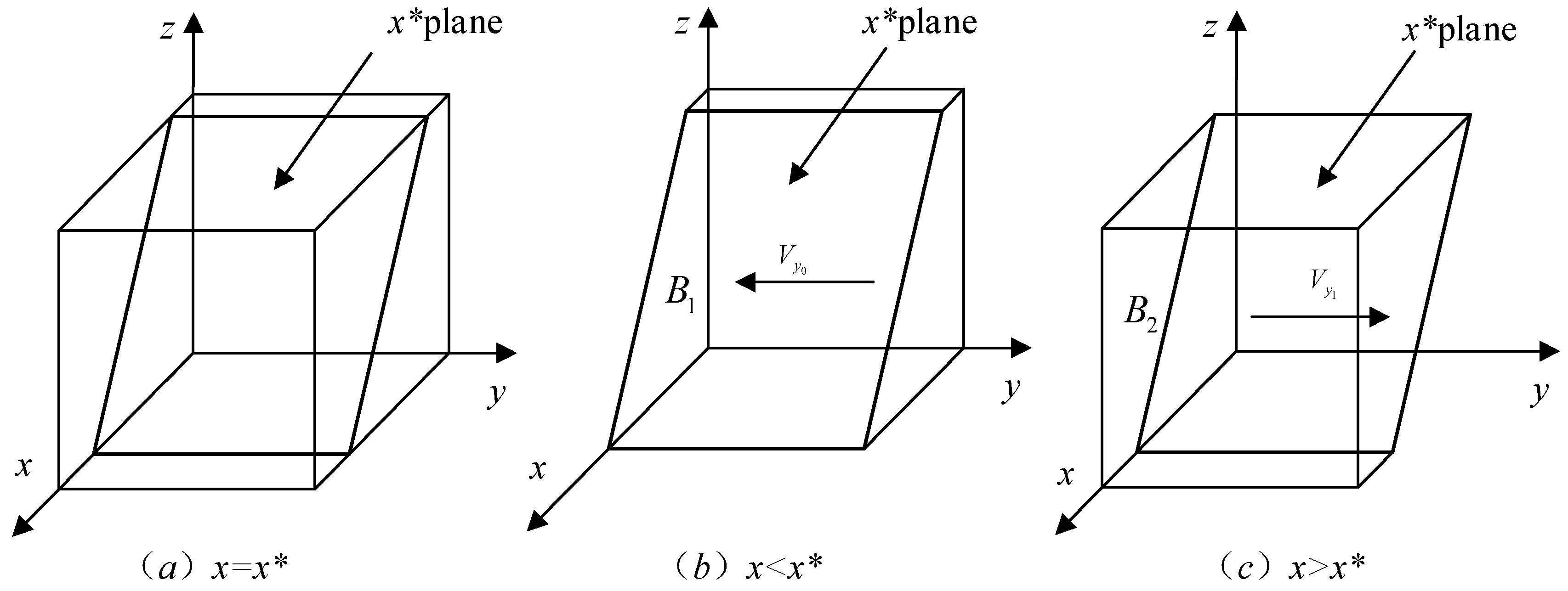

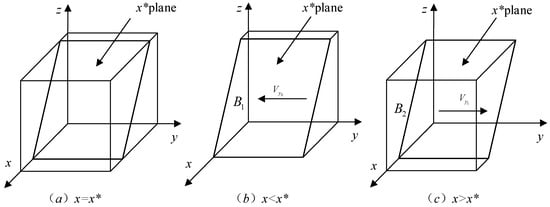

Proposition 3 indicates that, holding other parameters constant, platforms’ strategy is influenced to some extent by the probability of users’ initial strategy. The higher the initial probability of users’ authorization, the greater the probability that platforms will choose the transaction strategy. The phase diagram of platforms’ strategy evolutionary dynamics is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Dynamic phase diagram of platforms’ strategy evolution.

Further analysis reveals that when , there is . It means that decreases as increases, and plane moves along the negative direction of axis . As a result, the volume of , which represents the probability of platforms selecting a transaction strategy, increases. Similarly, when , there is ; when and , there is ; when , there is ; when , there is ; when , there is ; when and , there is . The following proposition is thus summarized:

Proposition 4.

Regarding the probability of platforms selecting the transaction strategy, when , it is positively correlated with and negatively correlated with ; When , it is positively correlated with ; When and , it is positively correlated with ; when , it is positively correlated with ; when , it is negatively correlated with ; when and , it is negatively correlated with .

Proposition 4 indicates that while the probability of platforms’ data transaction strategy is primarily determined by the relative strength of potential gains versus potential risks, it does not strictly increase with the growth of potential gains such as data value, benefit coefficient, or transaction price coefficient. Nor does it strictly decrease with the growth of potential risks such as data leakage probability or government fines. These factors mutually constrain each other, collectively influencing the probability of platforms’ data transaction strategy, resulting in a highly complex pattern of strategy selection.

4.3. Expected Payoff of Government

The expected payoff when the government chooses a strict regulation strategy is , the expected payoff when the government chooses a loose regulation strategy is , and the expected payoff of the government is . Therefore,

The replication dynamic equation of the government is:

The first derivative of the replication dynamic equation is:

Letting yields:

Therefore, when , there is , , and is the equilibrium point of the evolutionary game, at which the government chooses the loose regulation strategy; when , there is , , and is the equilibrium point of the evolutionary game, at which the government chooses the strict regulatory strategy; when , there is , it indicates that all points on are in a stable state, meaning the government’s strategy does not change over time. This leads to the following proposition:

Proposition 5.

When , is the government’s evolutionarily stable strategy; when , is the government’s evolutionarily stable strategy; when , the stable strategy cannot be determined.

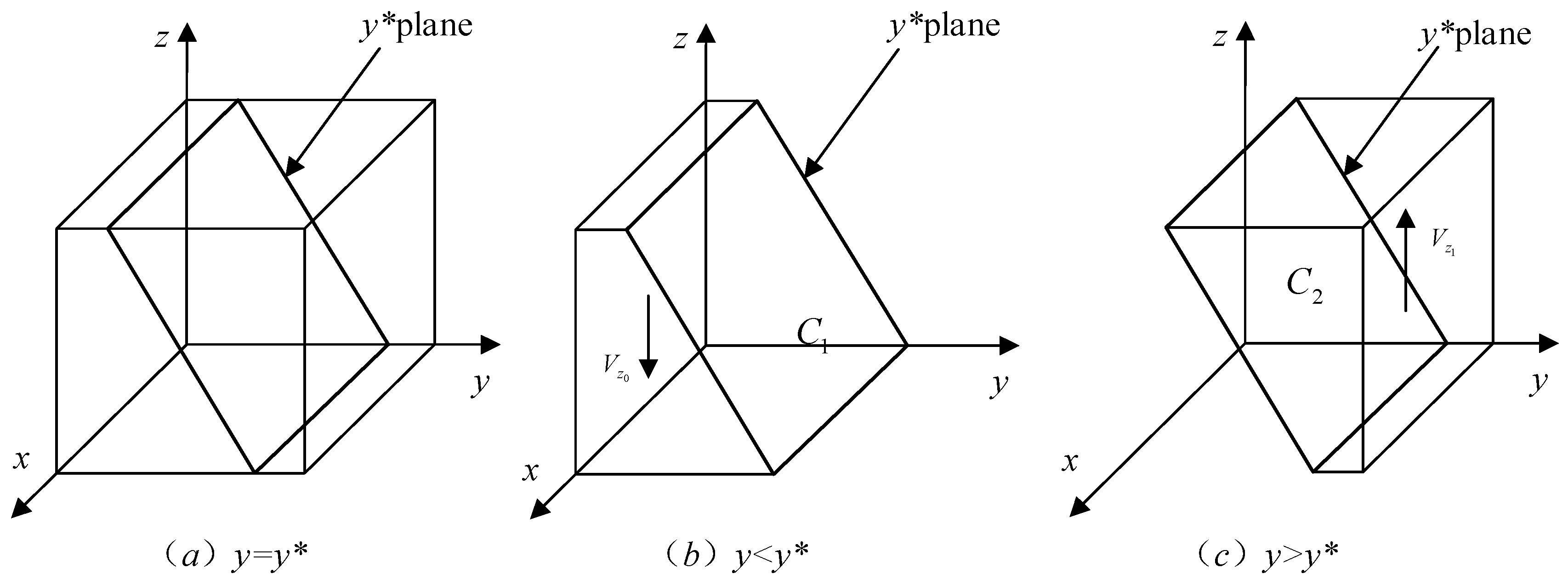

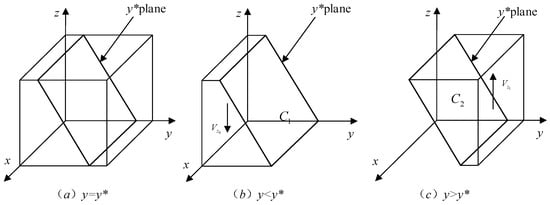

Proposition 5 indicates that, holding other parameters constant, the probability of the government choosing strict regulation is to some extent related to the probability of platforms’ initial strategy. The higher the probability that platforms choose the transaction strategy, the greater the probability that the government will opt for strict regulation. The phase diagram of the government’s strategy evolution dynamics is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Dynamic phase diagram of the government’s strategy evolution.

Computing the first-order partial derivatives of each parameter with respect to , yields , , and . That is to say, as , , , increases, decreases, the plane moves toward the negative direction of axis , and increases in volume—meaning the probability of the government choosing the strict regulatory strategy increases. Additionally, suggests that increases as increases, the plane moves toward the positive direction of axis , and decreases in volume—meaning the probability of the government choosing the strict regulation decreases. Based on the above, the following proposition is summarized:

Proposition 6.

Regarding the probability of the government selecting the strict regulatory strategy, it is positively correlated with , , and , but is negatively correlated with .

Proposition 6 indicates that government regulatory strategy is primarily based on a comparison between the benefits of strict regulation and the associated costs. When the fines imposed on platforms following data breaches, the probability of data leaks, and reputational damage are greater, the government tends to favor stricter regulation; conversely, when the costs of strict regulation are higher, it leans toward loose regulation.

4.4. Analysis of the Evolutionary Stabilization Strategy

Based on the above tripartite evolutionary game model and their respective expected payoffs, the three-dimensional replicating dynamical system equation is derived as follows:

Based on the three-dimensional replicating dynamic system model, the Jacobian matrix is obtained as follows:

Based on Lyapunov stability theory, the evolutionary game equilibrium in asymmetric games is a pure strategy equilibrium. Therefore, this study only investigates the pure strategy equilibrium points under conditions , , . The system equilibrium points can be determined as , , , , , , and . The system equilibrium points and eigenvalues are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

System equilibrium points and eigenvalues.

4.5. Analysis of Stabilization Conditions

The equilibrium point is an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS) if and only if the eigenvalues of its Jacobian matrix simultaneously meet , , and . Based on the model assumptions, we have: , . Therefore, the only possible stable points are , , , , and . Analyzing the eigenvalue conditions in Table 3 yields the following five scenarios.

Scenario 1. In this scenario, the evolutionary game’s stable point is , indicating the strategy combination of the three parties is (non-authorization, transaction, loose regulation). Specifically, users choose not to authorize, platforms opt for behavioral data transaction, and the government selects loose regulation. The conditions required for this stable point are in Table 4.

Table 4.

The condition of , and for the stable point .

This condition indicates that when the data transaction price is low and behavioral data value falls within a certain range, or when the data price is high and behavioral data value exceeds a specific threshold, users choose not to authorize the use of their personal data in exchange for greater benefits. Meanwhile, the profits generated by platforms trading behavioral data outweigh the costs of data transactions, prompting them to opt for data transaction. Simultaneously, the high costs of strict regulation render it unaffordable for government, leading it to choose loose regulation.

Scenario 2. In this scenario, the evolutionary game stabilizes at point , indicating the strategy combination of the three parties is (non-authorization, transaction, strict regulation). Specifically, users choose not to authorize, platforms opt for behavioral data transaction, and the government opts for strict regulation. The conditions required for this stable point are in Table 5.

Table 5.

The condition of , and for the stable point .

The conditions for this scenario are similar to those in Scenario 1. When behavioral data is valued within a certain range at a lower transaction price, or when its value exceeds a specific threshold at a higher transaction price, users choose not to authorize while platforms opt to transact. The key difference lies in the lower strict regulatory costs, which enable the government to achieve a balanced budget through revenues such as fines and enhanced reputation. This creates a stronger incentive for the government to adopt stricter regulatory measures.

Scenario 3. In this scenario, the evolutionary game’s stable point is , indicating the strategy combination of the three parties is (authorization, non-transaction, loose regulation). Specifically, users choose to authorize, platforms choose not to transact, and the government chooses loose regulation. The conditions required for this stable point are . In this scenario, the value of user behavioral data is relatively low. Users have an incentive to authorize platforms to use their personal data in exchange for greater benefits, leading them to choose authorization. However, the low value of behavioral data means platforms’ revenue from data transactions is less than the cost of conducting such transactions, prompting platforms to choose not to trade. Platforms’ non-trading strategy reduces the government’s incentive for strict regulation, leading it to opt for loose regulation.

Scenario 4. In this scenario, the evolutionary game theory stable point is . This stable point represents the strategy combination of the three parties: (authorization, transaction, loose regulation). Specifically, users choose authorization, platforms choose transaction, and the government chooses loose regulation. The conditions required for this stable point are in Table 6.

Table 6.

The condition of , and for the stable point .

This condition indicates that when the data transaction price is low and the value of user behavioral data exceeds a certain threshold, or when the data transaction price is high and the value of user behavioral data falls within a specific range, users can gain additional benefits by granting authorization, leading them to choose authorization. Simultaneously, platforms’ revenue from trading personal data and behavioral data exceeds the transaction costs, prompting platforms to engage in data transaction. Significant strict regulatory costs diminish platforms’ willingness to enforce strict regulation, compelling the government to adopt a more lenient regulatory strategy instead.

Scenario 5. In this scenario, the evolutionary game theory stable point is . This stable point represents the strategy combination of the three parties: (authorization, transaction, strict regulation). Specifically, users choose authorization, platforms choose transaction, and the government chooses strict regulation. The conditions required for this stable point are in Table 7.

Table 7.

The condition of , and for the stable point .

In this scenario, the strategy of users and platforms resembles that of Scenario 4. Users choose to authorize and platforms choose to engage in data transactions when behavioral data value exceeds a certain threshold under a lower data transaction price, or when behavioral data value falls within a specific range under a higher data transaction price. The difference lies in the fact that larger fines and reputational gains enable the government to bear the costs of strict regulation, thereby incentivizing it to opt for strict regulation.

As demonstrated in Scenarios 1 and 2, platforms may trade user behavioral data even without user authorization. Scenario 3 shows that even with user authorization, platforms may refrain from any data transactions despite being able to trade personal and behavioral data. Thus, user authorization does not invariably promote platform data transactions. In summary, under the user authorization mechanism, platforms’ choice of data transaction strategy is closely tied to the transaction price and the value of user behavioral data. As demonstrated by Scenarios 4 and 5, platforms will choose to trade both personal and behavioral data when the transaction price is low and the value of behavioral data exceeds a certain threshold, or when the transaction price is high and the value of behavioral data falls within a specific range. Therefore, only under these conditions can user authorization effectively promote platform data transactions.

As demonstrated in Scenario 2, even without user authorization, the government may still impose strict regulation on the trading of user behavioral data by platforms. As shown in Scenario 4, even with user authorization, the government may still implement loose regulation on the trading of both personal and behavioral user data by platforms. This indicates that user authorization alone is not a sufficient condition for the government to adopt a strict regulatory strategy toward platform data transactions. In summary, under the user authorization mechanism, the government’s regulatory strategy for platform data transactions is closely tied to the transaction price, the value of user behavioral data, and regulatory costs. Scenario 5 indicates that a three-party equilibrium where the government imposes strict regulation on platform data transactions under user authorization only emerges when either the transaction price is low, the value of user behavioral data is high, and regulatory costs are low, or the transaction price is high, the value of user behavioral data is moderate, and regulatory costs are low.

5. Evolutionary Simulation Analysis

5.1. Evolutionary Stable Strategies

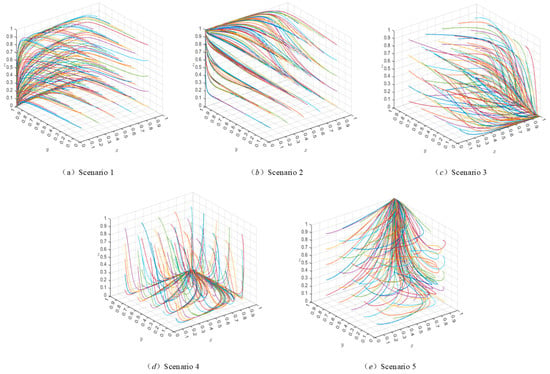

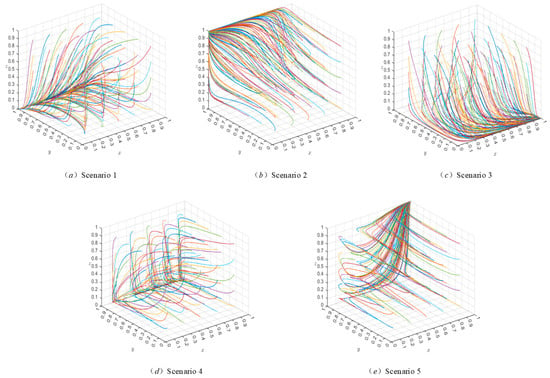

To further validate the model’s correctness, this study employs MATLAB R2023b to simulate the evolutionary process of the three-party strategy, exploring the evolutionary equilibrium of strategies among users, platforms, and government. Based on the actual context of this study, different parameter values are set under conditions and for simulation analysis. Specifically, when , the parameter values are as shown in Table 8, and when , the values of each parameter are as shown in Table 9.

Table 8.

Parameter settings for scenario .

Table 9.

Parameter settings for scenario .

Based on the above parameter settings, this study simulates the evolutionary trajectory of the evolutionary game system by setting the initial values for each strategy to be 0.1, with increments of 0.4 up to 0.9. The MATLAB R2023b evolutionary paths are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6. Here, the , and axes represent the probabilities that users , platforms , and the government , respectively, choose the strategy of authorization, transaction, and strict regulation. Each colored line represents the evolutionary path of the system over time, starting from a random initial state. The colors are used solely to distinguish trajectories originating from different initial points and carry no special meaning.

Figure 5.

System evolution pathway when .

Figure 6.

System evolution pathway when .

5.2. Parameter Analysis

Based on the discussion in Section 4.4, simulation analyses were conducted to examine how changes in the value of user behavior data under scenarios of higher or lower data prices affect the evolution of the tripartite strategy equilibrium. The results are as follows.

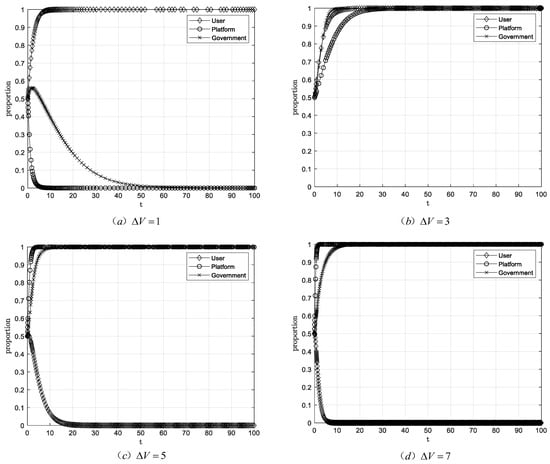

5.2.1. The Impact of When

The initial scenario was set with a step size of 2, while other parameter values remained consistent with the baseline scenario. The resulting system simulation evolution path is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Evolutionary equilibrium when .

Figure 7 simulation results indicate that when the value of user behavioral data falls below a certain threshold, the stable strategy combination is (authorization, non-transaction, loose regulation). When the value of user behavioral data exceeds a certain threshold, platforms adopt the transaction strategy. As analyzed in Proposition 5, the probability of government’s strict regulation increases continuously until the strict regulation strategy is selected, ultimately reaching the stable strategy (authorization, transaction, strict regulation). As the value of user behavioral data further increases, the stable policy combination evolves to (non-authorization, transaction, strict regulation). This trend indicates that when and the value of user behavioral data falls within a certain range, platforms’ strategy can stabilize on transaction under user authorization; when the value of user behavioral data exceeds this range, platforms’ strategy can still stabilize on transaction under non-authorization; however, when the value of user behavioral data falls below this range, platforms’ strategy stabilizes on non-transaction. Furthermore, when and the value of user behavior data falls within a certain range, the government strategy can stabilize at strict regulation when users grant authorization. When the value of user behavior data exceeds this range, the government strategy can still stabilize at strict regulation even when users do not grant authorization.

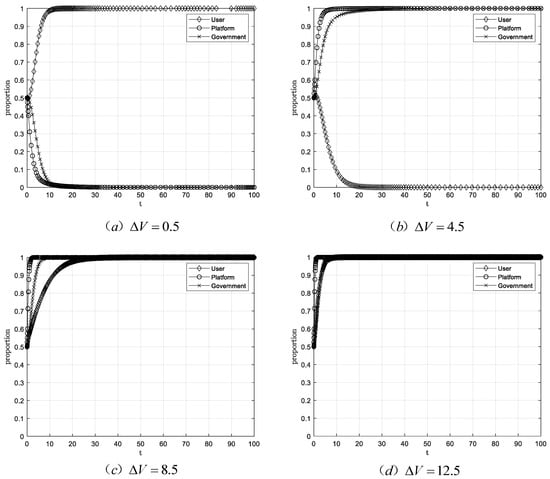

5.2.2. The Impact of When

Modifying the value of user behavior data, under the initial scenario with a step size of 4 and all other parameters consistent with the baseline scenario, yields the system simulation evolution path shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Evolutionary equilibrium when .

Figure 8 simulation results indicate that when the value of user behavioral data falls below a certain threshold, the stable strategy combination is (authorize, non-transaction, loose regulation). When the value exceeds this threshold, the stable strategy becomes (non-authorization, transaction, strict regulation). As the value of user behavioral data continues to increase, it ultimately reaches a stable point (authorization, transaction, strict regulation). This trend indicates that when and the value of user behavioral data falls within a certain range, platforms’ strategy can stabilize on trading when users do not grant authorization. When the value of user behavioral data exceeds this range, platforms’ strategy can still stabilize on transaction when users grant authorization. However, when the value of user behavioral data falls below this range, platforms’ strategy stabilizes on non-transaction. When and the value of user behavioral data falls within a certain range, the government’s strategy can stabilize at strict regulation when users do not grant authorization. When the value of user behavioral data exceeds this range, the government strategy can still stabilize at strict regulation when users grant authorization.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Findings

This study builds a tripartite evolutionary game model involving users, platforms, and the government to explore the interactions and evolutionary equilibrium among users’ data authorization strategy, platforms’ data transaction strategy, and the government’s regulation strategy under a user-authorized personal data mechanism. The key findings are as follows:

(1) Under the personal data authorization mechanism, the promotional effect of user authorization on platform data transactions is conditional. The study finds that user authorization does not necessarily enhance the activity of platform data transactions; its effectiveness primarily depends on the data transaction price and the value of user behavioral data. Specifically, user authorization can effectively promote platform data transactions only when the data transaction price is low and the value of user behavioral data exceeds a certain threshold, or when the data transaction price is high and the value of user behavioral data falls within a moderate range. Conversely, user authorization has limited promotional effects on platform data transactions and may even suppress such activities due to data leakage risks. This conclusion indicates that relying solely on user authorization mechanisms cannot fully resolve efficiency issues in data trading markets; synergistic optimization involving both data market supply–demand dynamics and data value assessment is necessary.

(2) Under the personal data authorization mechanism, government regulation of platform data transactions depends on multidimensional factors, with user authorization not constituting a sufficient condition for strict regulatory strategies. Research indicates that whether the government imposes stringent regulation on platform data transactions is influenced not only by user authorization behavior but more critically by the dynamic interplay of regulatory costs, data transaction prices, and the value of user behavioral data. Specifically, when regulatory costs are low, the government tends to impose strict regulation on platform data transactions under two conditions: when the data price is low and behavioral data value is moderate, or when the data price is high and behavioral data value is high—even without user authorization. Conversely, when user authorization exists, the government leans toward strict regulation under two conditions: when the data price is low and behavioral data value is high, or when the data price is high and behavioral data value is moderate. This indicates that the government’s regulatory logic is significantly guided by a “cost–benefit” approach, where user authorization serves only as one of the reference factors in regulatory decision-making, rather than a decisive condition.

6.2. Recommendations

The evolutionary equilibrium of options made by users, platforms, and government policies must foster a virtuous ecosystem characterized by user authorization, platform transactions, and strict government regulation. From the perspective of factors influencing behavioral strategies, the following policy recommendations are proposed:

(1) A standardized data trading market system should be established so that data transaction price reflects actual supply–demand dynamics. It is suggested to create a unified data exchange platform with tiered classification standards—categorizing data as foundational, critical, core, etc.—accompanied by differentiated pricing guidelines. Simultaneously, supporting mechanisms for data rights confirmation, registration, and settlement should be refined to effectively evaluate and adjust pricing standards, ensuring alignment with market value.

(2) A scientific data valuation mechanism should be developed to quantify the value of user personal data and behavioral data . It is suggested to establish national standards for data valuation, creating multidimensional quantitative models that incorporate factors like data quality and application scenarios. Professional third-party assessment agencies should be cultivated to provide objective value references for data transactions. Simultaneously, platform enterprises should be encouraged to implement dynamic pricing based on assessment results and enhance data transparency by clearly disclosing data flow and usage to users.

(3) Data breach prevention and control should be strengthened by optimizing penalty and regulatory costs . Tiered fines linked to data value and harm severity should be implemented to impose strict penalties for high-value data breaches or major violations. Blacklist and credit punishment mechanisms should be refined to conduct regular security inspections, and data trading parties should be urged to implement protective measures like encryption and access controls to enhance overall security standards.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study presents a tripartite evolutionary game model focusing on the interactions between users, platforms and the government under a user data authorization mechanism, and examines their strategies and evolutionary equilibrium. However, the model is primarily based on the characteristics of China’s data trading market and involves certain contextual simplifications. The universality of its conclusions across different institutional environments therefore warrants careful scrutiny. Specifically, the model framework may have limitations when applied to different data governance systems, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Additionally, elements unique to digital markets, including multiple user groups and network effects, remain outside the analytical scope of the current model. Therefore, future research could test the model within broader institutional and market contexts. Particular emphasis should be placed on validating and expanding the theoretical findings of this study in real-world scenarios involving cross-border data flows and the interaction of multiple governance frameworks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, Z.L. and J.L.; writing, Z.L. and J.L.; supervision, Z.L.; numerical simulation, J.L., M.Q. and Z.C.; investigation and visualization, J.L., M.Q. and Z.C.; Project administration and writing—review and editing, Z.L. and J.L.; Supervision and writing—review and editing, Z.L. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China (grant number 25BGL127).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions to improve the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, Q.; Serfes, K. Customer Information Sharing among Rival Firms. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2006, 50, 1571–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.I.; Tonetti, C. Nonrivalry and the Economics of Data. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 2819–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquisti, A.; Taylor, C.; Wagman, L. The Economics of Privacy. J. Econ. Lit. 2016, 54, 442–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldkamp, L.; Chung, C. Data and the Aggregate Economy. J. Econ. Lit. 2024, 62, 458–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaessler, F.; Wagner, S. Patents, Data Exclusivity, and the Development of New Drugs. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2022, 104, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varian, H.R. Artificial Intelligence, Economics, and Industrial Organization; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tomak, K.; Keskin, T. Exploring the Trade-off Between Immediate Gratification and Delayed Network Externalities in the Consumption of Information Goods. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2008, 187, 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abowd, J.M.; Schmutte, I.M. An Economic Analysis of Privacy Protection and Statistical Accuracy as Social Choices. Am. Econ. Rev. 2019, 109, 171–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosis, A.; Sand-Zantman, W. The Ownership of Data. J. Law. Econ. Organ. 2023, 39, 615–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.R.; Tucker, C. Privacy Protection, Personalized Medicine, and Genetic Testing. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 4648–4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besbes, O.; Mouchtaki, O. How Big Should Your Data Really Be? Data-Driven Newsvendor: Learning One Sample at A Time. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 5848–5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Gill, S.; Brynjolfsson, E.; Hak, N. Helping Small Businesses Become More Data-Driven: A Field Experiment on EBay. Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 7345–7372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; George, J.F. Toward the Development of A Big Data Analytics Capability. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 1049–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, H.; Chang, Q.; Mao, Q. A Comprehensive Review of Digital Twins Technology in Agriculture. Agriculture 2025, 15, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, M.F.; Mao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Elmasry, G.; Awad, M.A.; Abdalla, A.; Mousa, S.; Elwakeel, A.E.; Elsherbiny, O. Emerging Technologies for Precision Crop Management towards Agriculture 5.0: A Comprehensive Overview. Agriculture 2025, 15, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.W.; Xie, D.; Zhang, L. Knowledge Accumulation, Privacy, and Growth in A Data Economy. Manag. Sci. 2021, 67, 6480–6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, S.; Thaichon, P.; Martin, K.D.; Weaven, S.; Palmatier, R.W. Digital Technologies: Tensions in Privacy and Data. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2022, 50, 1299–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, C.; Cong, J.; Wang, C. Softening Competition Through Unilateral Sharing of Customer Data. Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 526–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Cire, A.A.; Hu, M.; Lagzi, S. Model-Free Assortment Pricing with Transaction Data. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 5830–5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Miao, S.; Momot, R. Privacy-Preserving Personalized Revenue Management. Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 4875–4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouah, A.; Bahamou, A.; Besbes, O. Optimal Pricing with A Single Point. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 5866–5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beraja, M.; Yang, D.Y.; Yuchtman, N. Data-Intensive Innovation and the State: Evidence from AI Firms in China. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2023, 90, 1701–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcigit, U.; Celik, M.A.; Greenwood, J. Buy, Keep, or Sell: Economic Growth and the Market for Ideas. Econometrica 2016, 84, 943–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Weber, R.A. Revealed Privacy Preferences: Are Privacy Choices Rational? Manag. Sci. 2025, 71, 2657–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J. A Survey on Data Pricing: From Economics to Data Science. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2020, 34, 4586–4608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J.; Pathak, P.A.; Tirole, J. The Dynamics of Open-Source Contributors. Am. Econ. Rev. 2006, 96, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wu, S.; Banker, R. Best pricing strategy for information services. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2010, 11, 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergemann, D.; Bonatti, A. Selling Cookies. Am. Econ. J. Microecon. 2015, 7, 259–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T.; Hazarika, D.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E. Recent Trends in Deep Learning Based Natural Language Processing. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2018, 13, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer-Hänsel, I.; Liu, Q.; Tessone, C.J.; Schwabe, G. Designing A Blockchain-Based Data Market and Pricing Data to Optimize Data Trading and Welfare. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2024, 28, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.E.; Agahari, W.; van de Ven, M.; Zuiderwijk, A.; de Reuver, M. Business Data Sharing through Data Marketplaces: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 3321–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutroumpis, P.; Leiponen, A.; Thomas, L.D.W. Markets for Data. Ind. Corp. Change 2020, 29, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zha, X.; Zhang, H.; Dan, B. Information Sharing in A Cross-Border E-Commerce Supply Chain Under Tax Uncertainty. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2022, 26, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.P.; Jungbauer, T.; Preuss, M. Online Advertising, Data Sharing, and Consumer Control. Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 7984–8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergemann, D.; Bonatti, A.; Gan, T. The Economics of Social Data. RAND J. Econ. 2022, 53, 263–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorzik, N.; Kirchhof, P.J.; Mueller-Langer, F. Industrial Data Sharing and Data Readiness: A Law and Economics Perspective. Eur. J. Law. Econ. 2024, 57, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Ghosh, P.; Ruan, T.; Zhang, Y. Transient Customer Response to Data Breaches of Their Information. Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 4105–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, R.; Câmara, O. Organizing Data Analytics. Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 3123–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbonavicius, S. Relative Power of Online Buyers in Regard to A Store: How It Encourages Them to Disclose Their Personal Data? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhou, L.; Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, R.; Zhu, G. Platform Perspective Versus User Perspective: The Role of Expression Perspective in Privacy Disclosure. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebbecke, C.; van Fenema, P.C.; Powell, P. Managing Inter-Organizational Knowledge Sharing. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2016, 25, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notheisen, B.; Cholewa, J.B.; Shanmugam, A.P. Trading Real-World Assets on Blockchain: An Application of Trust-Free TransAction Systems in the Market for Lemons. Bus. Inform. Syst. Eng. 2017, 59, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Gefen, D. Building Effective Online Marketplaces with Institution-Based Trust. Inform. Syst. Res. 2004, 15, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.-T. Role of Privacy Legislations and Online Business Brand Image in Consumer Perceptions of Online Privacy Risk. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 14, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Yuan, Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, K.; Xu, J. The Value of Personal Data in Internet Commerce: A High-Stakes Field Experiment on Data Regulation Policy. Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 2645–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Lan, J.; Huang, S.; Chen, L. Effects of Privacy Regulatory Protection on Users’ Data Sharing in Mobile Apps. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marikyan, D.; Papagiannidis, S.; Rana, O.F.; Ranjan, R. General Data Protection Regulation: A study On Attitude and Emotional Empowerment. Behav. Inform. Technol. 2024, 43, 3561–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S. Data Marketplaces: A Solution for Personal Data Control and Ownership? Sustainability 2020, 14, 16884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, H.; Tao, C. Evolutionary Game of Platform Enterprises, Government and Consumers in the Context of Digital Economy. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 167, 113858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Hauwers, R.; Vandercruysse, L. Competitive Advantage and Personal Data Ecosystems: A Typology of Personal Data Control Constellations. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.