Abstract

Despite widespread adoption of loyalty programs, little is known about how the shape of points accumulation frameworks influences consumer spending via psychological mechanisms and individual differences. Grounded in Prospect Theory and goal-gradient theory, this research examines the impact of linear versus accelerating points accumulation structures on spending intentions across four experiments (N = 1400) using online panels. Stages 1 and 2 manipulation experiments were conducted using simulated loyalty program brochures and e-commerce webpages, demonstrating that accelerating frameworks (versus linear) increase spending intentions by enhancing perceived reward value. Stage 3 used a 2 × 2 between-subjects design, manipulating the points framework with fictitious brochures and priming financial risk tolerance via a portfolio reflection task; temporal discounting was subsequently measured to assess its role (temporal discounting is the tendency for people to assign greater value to immediate rewards than to larger, delayed rewards), confirming the moderating effect of temporal discounting. Stage 4 also employed a 2 × 2 between-subjects design, manipulating the points framework and priming risk tolerance through a writing task, thereby confirming the moderating effect of financial risk tolerance. These findings identify perceived reward value as a key mediator and temporal discount rate and financial risk tolerance as critical moderators. Theoretical contributions include the first-time integration of temporal discounting and individual risk preferences into loyalty program theory, while practical implications offer guidance for designing loyalty programs tailored to specific market segments, thereby enhancing consumer engagement.

1. Introduction

Loyalty programs have become a central driver of consumer purchasing behavior, significantly shaping revenue and competitive strategy across industries. Research from CouponBirds (2024) [1] indicates that 94.3% of consumers belong to at least one customer loyalty program offering rewards, discounts, or other incentives, with an average of 7.5 programs per person. Studies by Accenture (2025) [2] show that loyalty program members generate 12–18% more incremental revenue than non-members. Moreover, tiered and points-based reward systems have been found to enhance revenue growth by increasing customer retention and purchase frequency. For example, Sephora’s loyalty program in North America, with 17 million members, increased cross-selling revenue by 22% [3]. These findings underscore the strategic significance of loyalty program design in driving consumer engagement and firm revenue, yet prior research largely focuses on aggregate behavioral outcomes rather than the psychological and structural mechanisms underlying these effects.

The structure of point accumulation can critically influence consumer spending, but the psychological mechanisms differentiating linear and accelerating designs remain insufficiently understood. Prior studies show that accumulation rates affect engagement and purchase intentions [4,5]. For instance, research in the restaurant industry suggests that as customers approach rewards, accelerating point accumulation significantly increases motivation, particularly beyond the midpoint of reward attainment [6], indicating that accelerating designs may outperform linear ones in driving spending. However, these effects have not been systematically examined across different customer segments or industries. Similarly, mathematical analyses indicate that income-based loyalty programs can enhance profitability by adjusting accumulation structures [7], but the impact of linear versus accelerating designs on consumers with varying income levels and purchase frequencies remains unexplored. Collectively, these observations highlight a critical research gap concerning the boundary conditions and psychological mechanisms of point accumulation structures.

This study investigates how linear and accelerating point accumulation structures influence consumer spending, proposing Perceived Value of Rewards as a mediator and examining temporal discount rate and financial risk tolerance as moderators within a Prospect Theory framework. By integrating these psychological and individual difference factors, the research provides a more nuanced understanding of how loyalty program design drives consumer responses, extending beyond existing literature focused primarily on behavioral outcomes.

Loyalty programs reward repeat purchases to encourage retention and increase expenditure, with program design playing a pivotal role in effectiveness. Linear designs provide a fixed rate of points per dollar, offering predictability, whereas accelerating designs increase point accumulation as spending thresholds are reached, potentially enhancing perceived reward value. McKinsey [8] reports suggest that accelerating schemes can drive revenue growth of 15–25% per annum through increased redemptions. Nevertheless, the psychological drivers underlying these effects—particularly how consumers perceive reward nearness and certainty—remain underexplored.

Perceived Value of Rewards, defined as consumers’ overall judgment of the benefits and attractiveness of rewards, goes beyond monetary worth to include functional and emotional dimensions [9,10]. In this study, it represents the subjective evaluation of accumulated points, influencing purchase intentions and engagement [11]. Accelerating designs enhance perceived value through milestone effects and psychological momentum, whereas linear designs provide stable but less stimulating returns [12]. Linking accumulation structures to Perceived Value of Rewards clarifies the mechanism by which program design drives consumer spending.

Prospect Theory suggests that decisions are made relative to a reference point, with outcome framing shaping choice under risk. In loyalty programs, points function as perceived gains, and the accumulation structure influences how value is assessed. Accelerating structures may amplify perceived gains by emphasizing increasing returns, whereas linear structures offer frequent but smaller gains, which can be undervalued when individuals assess risk. Perceived Value of Rewards is hypothesized to mediate the effect of accumulation structure on spending.

Individual differences such as temporal discount rate and financial risk tolerance are proposed as moderators. Temporal discount rate reflects preferences for immediate versus delayed payoffs; individuals favoring immediate satisfaction may respond more strongly to accelerating patterns, encouraging spending. Financial risk tolerance shapes engagement with reward structures: high-risk-tolerant consumers tend to prefer accelerating designs, while risk-averse consumers lean toward linear designs. These patterns align with Prospect Theory, which posits that subjective valuation influences how reward framing affects behavior.

Although prior literature extensively examines loyalty programs, research has not yet clearly addressed how linear versus accelerating point accumulation structures influence spending via Perceived Value of Rewards, nor how individual differences moderate these effects. This study addresses these gaps by posing three research questions:

RQ1: How do linear and accelerating designs affect consumer spending patterns?

RQ2: Does Perceived Value of Rewards mediate the relationship between accumulation structure and spending behavior?

RQ3: Do temporal discount rate and financial risk tolerance moderate these effects?

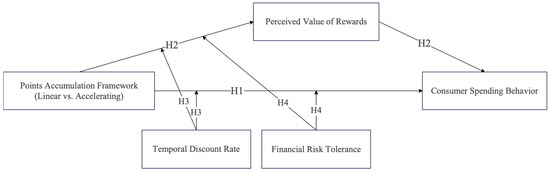

The proposed model suggests that point accumulation designs (independent variable) influence spending behavior (dependent variable) through Perceived Value of Rewards (mediator), moderated by temporal discount rate and financial risk tolerance. Grounded in Prospect Theory, the model posits that design manipulates perceived gains, mediated by reward valuation, with effects varying across individual preferences. Examining this model can identify causal mechanisms driving spending in loyalty programs.

This research makes several key contributions to theory and practice. Theoretically, it enhances understanding of how loyalty program structures shape perceptions of reward value and spending behavior. For instance, Perceived Value of Rewards is identified as a full mediator, indicating that effects stem from reward evaluation rather than interface aesthetics. Additionally, task involvement and browsing goals moderate these effects, and accelerating loyalty point structures increase spending intentions through Perceived Value of Rewards, with risk preferences and cultural differences further shaping effectiveness [13].

Practically, the findings offer actionable guidance for UX designers, digital marketers, and loyalty program managers. Accelerating point programs can increase engagement and revenue when visual cues and messaging emphasize progressive reward value. Tailoring strategies according to user involvement, browsing goals, risk tolerance, and cultural context allows firms to optimize both interface effectiveness and loyalty program performance across diverse digital environments.

2. Literature Review

In this study, we draw upon several established theories to explore the psychological and behavioral mechanisms that influence consumer spending in loyalty programs. Theories such as Prospect Theory [14] and Goal-Gradient Theory [15] provide the foundation for understanding consumer motivation and decision-making under conditions of reward accumulation. Furthermore, psychological concepts such as temporal discounting and financial risk tolerance are integrated into the framework to examine individual differences in consumer responses to loyalty program designs. Recent reviews also highlight how behavioral biases influence consumer decisions and loyalty program effectiveness [16,17].

2.1. Theory

Prospect theory, first introduced by Kahneman and Tversky in 1979 [14], is a psychological theory that deviates from expected utility theory by explaining how individuals make choices on potential gains and losses in uncertain environments. The core elements of the theory are reference dependence and loss aversion. Reference dependence suggests that individuals evaluate outcomes relative to a reference point rather than in absolute terms. Loss aversion implies that losses are psychologically more significant than equivalent gains, leading individuals to make decisions that avoid losses. These concepts explain why consumers may be more motivated to engage with loyalty programs, particularly those with accelerating point accumulation, as they seek to avoid the “loss” of not reaching the next reward threshold. This aligns with Goal-Gradient Theory, which suggests that the closer consumers get to a reward, the more motivated they become to achieve it [18]. The psychological distance to the reward is compressed in accelerating programs, directly boosting consumers’ spending intentions [19]. Recent research further suggests that loyalty programs incorporating behavioral economics principles, such as framing and default options, enhance participation and engagement [20].

The theory explains how different reward structures influence consumer expenditure by shaping reference points and perceived losses when progress toward rewards slows or accelerates [21]. These schemes exploit decreasing sensitivity by providing higher returns at higher levels, which are perceived as disproportionately valuable when expressed in points, rather than money [22]. Elements of time, in the form of time constraints, create urgency via the framing of loss in the event of incompletion or falling behind in a certain time frame but not cost–benefit trade-offs [23]. Grewal and Lindsey-Mullikin’s (2006) [24] experiments demonstrate that framing points in the form of plus and minus framing are closely associated with perceptions and consumer expenditure behaviors.

2.2. Points Accumulation Framework (Linear vs. Accelerating)

Points accumulation framework of loyalty schemes determines the regime by which consumers earn points from interactions with a company, more typically contrasted with accelerating and linear accumulation regimes. In a linear regime where points earn at a constant speed, e.g., one point per dollar, there is a predictable and transparent reward mechanism [25]. An accelerating regime, on the other hand, speeds up points’ acquisition pace upon reaching set boundaries or stop points, often through the use of gamification to encourage greater participation [26]. This sense of increasing returns is directly linked to Reward Acceleration Theory [9], which emphasizes that consumers perceive greater value when returns increase with higher levels of spending. These accelerating systems not only motivate higher engagement but also deepen brand commitment by creating a gamified experience, which elicits word-of-mouth promotion [27]. Meta-analytic evidence also confirms that program effectiveness varies by design and industry, with stronger effects on behavioral loyalty than attitudinal loyalty [25].

Notwithstanding these findings, gaps exist in the literature. There has been a glaring lack of longitudinal studies on how sustained impacts of accelerating versus linear systems affect customer loyalty and retention [28]. Few studies have experimentally tested the psychological mediators that explain how these designs influence consumer behavior. Psychological mechanisms such as perceived reward value and psychological distance have been identified as key factors, yet their roles remain underexplored in experimental settings. This gap in the literature is particularly important, as understanding these mediators could offer deeper insights into how loyalty program designs function beyond mere structural effects, thereby advancing both theoretical and practical applications of loyalty programs. Additionally, interactions among points accumulation structures and other marketing tools, such as experiential incentives or personalized communication, are not well understood [29]. Cultural variables, as well as context, are also potential moderators, but there are few cross-cultural studies. These gaps in information would be beneficial to be filled in order to optimize program design and also consumer engagement in markets that are different in their cultures. Emerging technologies such as blockchain-based programs add further complexity, as their acceptance depends on multiple behavioral and technological factors [30].

2.3. Perceived Value of Rewards

Perceived value of reward is defined here as consumers’ own judgment of the incentives’ value and attractiveness in loyalty schemes. It encompasses functional, emotive, and societal attributes that motivate consumers’ perception of and response to schemes of rewards [9]. Perceived value extends far beyond monetary valuation to include psychological benefit in the form of status and success recognition [10]. The chosen accumulation structure shapes these perceptions; for example, milestone-based designs can heighten engagement, whereas consistent-rate designs may appeal to those who prefer predictability [12,31].

Consumers’ perceived value of rewards significantly influences spending behavior through several mechanisms. First, higher perceived value increases consumers’ willingness to make purchases to redeem rewards [11,32]. Second, it affects brand-specific commitment, with social rewards fostering affective commitment and economic rewards fostering continuance commitment, where affective commitment leads to higher relational value [9]. Third, perceived reward value shapes a mental model that encourages consumers to accelerate spending when they see rewards as valuable [33]. Additionally, when consumers perceive rewards as autonomous rather than imposed, their engagement and spending are enhanced [19]. In summary, perceived reward value is a key mediator between loyalty program design and consumer spending.

Prospect Theory explains how individuals evaluate gains and losses relative to reference points, while goal-gradient theory supports the motivational power of accelerating rewards. The perceived value of rewards emerges as a central mediator, translating structural features into behavioral outcomes. Individual differences—namely temporal discounting and financial risk tolerance—further moderate these effects. Building on these insights, we now proceed to formally develop and test four hypotheses that integrate these mechanisms into a cohesive model of loyalty program effectiveness.

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Points Accumulation Framework, Perceived Value of Rewards and Spending Behavior

Drawing on goal-setting theory [15], points accumulation mechanisms in loyalty programs can systematically influence consumer spending behavior. This theory posits that clearly structured and progressively challenging goals enhance motivation and effort, suggesting that the design of points schemes may shape expenditure patterns. Specifically, accelerating points accumulation architectures—where later actions yield higher points—create a perception of escalating returns, potentially heightening consumer engagement. In contrast, linear architectures, in which points are earned at a constant rate, provide static incentives that are less likely to stimulate increased spending. Belli et al. (2021) [25] demonstrate that programmatic structures of loyalty schemes, e.g., points plan, enhance behavioral loyalty by translating rewards to effort contributed by consumers. In turn, Kunkel et al. (2023) [26] recognize that progress-based affordances, also a property of accelerating architectures, encourage activity by relating to actual-world benefits. Together, these theoretical insights suggest that accelerating architectures are more likely than linear architectures to increase consumer expenditure by amplifying motivational drive through escalating reward designs.

Building upon this assumption, perceived reward value mediates accelerated framework influence on expenditure behavior. Accelerated schemes increase perceived value by establishing a sense that more returns are offered through persistent effort, as argued by Melancon et al. (2011) [9], who state that reward structures determine relational worth. Such higher worth results from consumers’ cognitive assessment of reward attainability, along with its appeal, through accelerating schemes [31]. Higher perceived value, in turn, results in increased expenditure, as consumers act to reap the most benefits from points schemes. Arslanagic-Kalajdzic and Zabkar (2017) [34] point out that perceived value, both functional and affective, strongly predicts such behaviors as loyalty. Whittaker et al., 2021 [11], further demonstrate that reward-based mechanisms, e.g., points, have a direct influence on perceptions of value, then on behavior. This suggests a mediating mechanism: accelerating points accumulation architectures elevate perceived reward value, which in turn drives higher spending behavior [35].

In summary, integrating goal-setting theory and value perception theory provides a coherent framework for understanding how points accumulation mechanisms influence consumer behavior. Accelerating schemes are theorized to enhance motivation through escalating rewards, while perceived reward value translates this motivational effect into tangible spending behavior. Based on this framework, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1:

Non-linear (accelerating) points accumulation models lead to a higher perceived value of rewards compared to linear models.

H2:

Perceived reward value mediates the positive effect of accelerating points accumulation schemes on consumer spending behavior.

3.2. Temporal Discount Rate

Building on the theoretical foundations of intertemporal choice and temporal discounting, individual differences in discount rates are expected to influence how consumers perceive rewards in loyalty programs [25,29]. Temporal discount rate reflects the degree to which consumers devalue future rewards relative to immediate ones [36,37]. Lower discount rates indicate a stronger orientation toward future benefits, whereas higher discount rates reflect a preference for immediate gains. From the perspective of Construal Level Theory, such devaluation of delayed outcomes can also be interpreted as a function of psychological distance, where rewards positioned further in time are perceived as less concrete and therefore discounted more heavily [38]. A central element of these schemes is the points accumulation model, and this has been developed along either a linear, where points are accumulated at a fixed rate, or an accelerating rate, where accumulating points is faster at higher expenditure levels [9,12].

The mechanism linking temporal discount rates to reward perception lies in the interaction between points accumulation design and consumers’ time preferences. Consumers with lower temporal discount rates are more sensitive to future-oriented rewards and may perceive accelerating points structures as more valuable because the potential for higher future gains aligns with their future-focused orientation [39,40]. In contrast, consumers with higher discount rates are more focused on immediate outcomes and may be less responsive to future-oriented accelerating structures, reducing perceived reward value. In this sense, psychological distance provides the underlying lens through which temporal discounting shapes reward evaluation, reinforcing the conceptual logic of our hypotheses. Perceived reward value, a fundamental mediator here, has a significant bearing on consumer expenditure, where increased perceived value leads to a higher level of engagement and expenditure [10,34].

Taken together, this theoretical reasoning suggests that the temporal discount rate moderates the effectiveness of points accumulation frameworks in enhancing perceived reward value. Specifically, accelerating structures are likely to produce stronger perceived reward value among consumers with lower temporal discount rates, while this effect is attenuated for those with higher discount rates. Therefore, we propose:

H3:

Temporal discount rate moderates the relationship between accelerating points programs and perceived reward value.

3.3. Financial Risk Tolerance

Financial risk tolerance represents an individual’s propensity to engage in decisions with uncertain outcomes, reflecting the perceived trade-off between potential gains and losses [41]. In the context of loyalty programs, points accumulation frameworks—either linear, where points are earned at a fixed rate, or accelerating, where points accumulate faster with higher expenditure—shape consumers’ perceptions of reward value [12,25]. Accelerating designs may enhance perceived reward value by emphasizing attainability and progress, thereby encouraging greater spending [9,12].

Perceived reward value serves as a key motivator of consumer spending, as consumers are more likely to increase expenditure when they perceive rewards as commensurate with effort [9]. However, whether perceived reward value translates into actual expenditure depends on individual differences in financial risk tolerance [41]. Consumers with high financial risk tolerance are more likely to act on perceived reward value by increasing spending, because they perceive potential gains as outweighing the uncertainty associated with higher expenditure [42]. In contrast, consumers with lower financial risk tolerance may recognize the attractiveness of rewards but remain hesitant to increase spending, due to discomfort with financial risk [43].

Accordingly, financial risk tolerance is expected to moderate the indirect effect of points accumulation frameworks on consumer spending behavior through perceived reward value. Specifically, the positive indirect effect of accelerating (versus linear) frameworks on spending, mediated by perceived reward value, should be stronger for consumers with higher financial risk tolerance, and weaker for those with lower tolerance. This moderation highlights how individual differences shape the effectiveness of loyalty program designs in driving consumer behavior (see Figure 1). Accordingly, we propose:

H4:

Financial risk tolerance moderates the indirect effect of accelerating points frameworks on consumer spending behavior through perceived reward value.

Figure 1.

Research Framework.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design and Methodology

Across four experiments, we examine how the shape of a loyalty program’s points accumulation framework influences consumer decision making and the psychological processes at play. Study 1 (N = 200, MTurk) manipulates the points accumulation framework to examine how linear and accelerating structures affect consumer spending intentions. Study 2 (N = 400, Prolific) replicates the main effect observed in Study 1 and investigates the mediating role of perceived reward value in the relationship between framework design and spending intentions. Study 3 (N = 400, Prolific) extends this investigation by exploring how different points accumulation frameworks influence temporal discounting, particularly among consumers with varying levels of financial risk tolerance. Finally, Study 4 (N = 400, Prolific) tests whether the impact of the points accumulation framework on planned spending is moderated by financial risk tolerance. These studies collectively aim to provide a deeper understanding of how the design of loyalty programs influences consumer behavior, with a particular emphasis on psychological factors and individual differences [44].

To enhance statistical reliability, a power analysis was performed using G*Power, verifying that the number of participants in each study was sufficient for detecting effects of moderate magnitude [45]. The study aimed for a participant count of approximately 100 per experimental group, which would offer an 80% chance of identifying effects of medium magnitude (Cohen’s d = 0.40) at a significance threshold of α = 0.05 (two-tailed).

4.2. Stage 1: Main Effect of Loyalty Program

4.2.1. Purpose

This study investigates whether the structure of a loyalty program’s points accumulation framework affects consumer spending intentions. We hypothesize that non-linear (accelerating) points accumulation models will increase perceived reward value compared to linear models, leading to higher spending intentions. Specifically, we aim to test whether the accelerating framework enhances consumer spending more than the linear framework by increasing the perceived value of rewards.

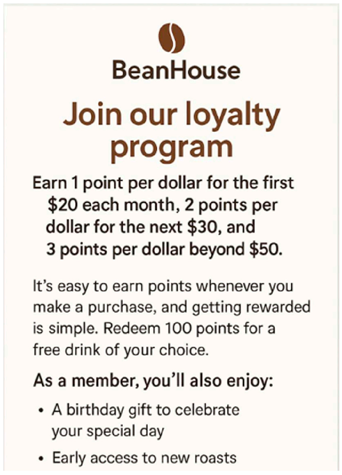

4.2.2. Stimuli and Pretest

Because no ready-made stimuli were available, we created two information-symmetric program brochures for a fictitious coffeehouse chain, “BeanHouse.” Each brochure displayed an identical layout, typography, colors, and length (≈180 words); only the points formula differed. In the linear condition, customers earned “1 point for every $1 spent.” In the accelerating condition, customers earned “1 point per dollar for the first $20 each month, 2 points per dollar for the next $30, and 3 points per dollar beyond $50,” thereby operationalizing a clearly increasing marginal reward (see Appendix A). Both brochures stated that 100 points could be redeemed for a free drink and listed identical non-monetary benefits (birthday gift, early access to new roasts).

A pretest with U.S. panelists (N = 160; 52% female; Mage = 34.27) verified the manipulation. Participants were randomly exposed to one brochure and then rated perceived reward acceleration on a single 7-point item (“The rewards became increasingly generous as spending grew”). Respondents in the accelerating condition reported significantly higher perceived acceleration (M = 5.96, SD = 0.83) than those in the linear condition (M = 2.48, SD = 1.05), t(158) = 24.17, p < 0.001. Thus, the stimuli successfully captured the intended distinction.

4.2.3. Procedure

Two hundred U.S. adults were recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk in return for $1.50 (51% female; Mage = 35.12, SD = 10.41). The university’s Institutional Review Board approved all procedures, and informed consent was obtained. Participants were randomly assigned to view either the linear or accelerating brochure in a between-subjects design. After reading the brochure for a mandatory minimum of 30 s, they completed a 90 s numeric Stroop task to reduce potential carry-over priming. The dependent variable, intended spending, was measured with three 7-point items adapted from Otterbring, Wu, and Kristensson (2021) [46]: “I would spend a lot of money at BeanHouse,” “I would increase my monthly spending at BeanHouse,” and “I am willing to spend more than usual at BeanHouse next month” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The items formed a reliable composite (α = 0.87). The manipulation check repeated the pretest item (“The reward structure became more generous the more I spent,” 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). To ensure the quality of responses, attention checks were incorporated into the study. These checks included both instructed-response items (e.g., “Please select ‘4’ for this item”) and content-specific questions (e.g., “Please answer the following question to confirm your attention: What is the main topic of the study?”). Participants who failed the attention checks were excluded from the analysis to maintain the integrity of the data. Finally, participants completed demographic questions and were debriefed. After attention tests, none of the participants were excluded.

4.2.4. Results

Manipulation check. A one-way ANOVA confirmed that the accelerating brochure was perceived as markedly more accelerating (M = 6.02, SD = 0.80) than the linear brochure (M = 2.55, SD = 1.11), F(1, 198) = 310.84, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.61, validating the manipulation.

Spending intention. A second one-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of points accumulation framework on intended spending, F(1, 198) = 22.36, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.10. Participants exposed to the accelerating program expressed higher spending intentions (M = 5.35, SD = 1.02) than those exposed to the linear program (M = 4.67, SD = 1.19).

4.2.5. Discussion

Study 1 demonstrated that merely reframing a loyalty program from linear to accelerating significantly elevated consumers’ intended spending. The effect aligns with the goal-gradient proposition that increasing marginal returns intensify motivation as progress accumulates, thereby encouraging greater economic engagement. For managers, adopting an accelerating points structure can stimulate incremental revenue without altering headline redemption thresholds. These findings set the stage for Study 2, which examines whether the observed spending lift is mediated by a higher value toward the reward.

4.3. Stage 2: Mediating Role of Perceived Value of Reward

4.3.1. Purpose

Study 2 was designed to establish the causal impact of the structure of a loyalty program’s points accumulation framework on consumers’ prospective spending, and to probe the mediating role of the perceived value of the program’s rewards. Building on reward-acceleration theory, we proposed that an accelerating framework—whereby each successive purchase earns proportionally more points than the previous one—would heighten perceived reward value and, in turn, increase intended spending relative to a linear points framework that provides a constant points-per-dollar ratio.

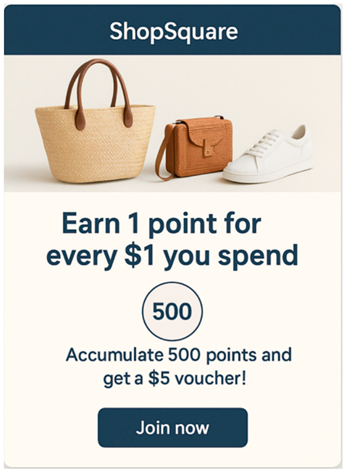

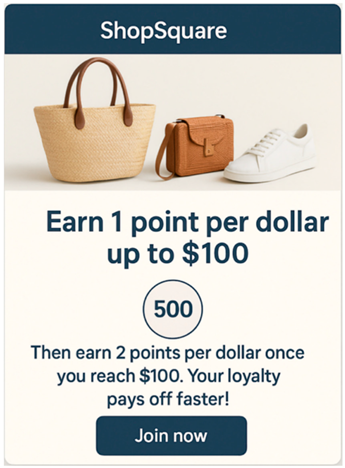

4.3.2. Stimuli and Pretest

Two visually identical mock e-commerce landing pages for a fictitious retailer named “ShopSquare” were constructed to manipulate the points accumulation framework while holding all other information constant (merchandise, imagery, color palette, program tiers, and copy length). Retail environments, particularly those offering low-cost, everyday products, provide a familiar context for participants, making it easier to generalize findings to real-world consumer decisions. The linear-framework page stated: “Earn 1 point for every $1 spent. Redeem 500 points for a $5 voucher.” The accelerating-framework page stated: “Earn 1 point for the first $100 spent and an extra 0.1 point for every additional dollar—so your points grow faster the more you shop. Redeem 500 points for a $5 voucher.” In both conditions, the economic value of points was identical; only the earning trajectory differed, ensuring informational symmetry (see Appendix B).

A pretest with 160 U.S. Prolific users (55% female, Mage = 33.41) confirmed that the manipulation altered the perceived acceleration of point accumulation. Participants rated “The speed at which points accumulate in this program increases over time” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The accelerating framework was perceived as far more accelerating (M = 5.92, SD = 0.96) than the linear framework (M = 2.83, SD = 1.18), t(158) = 18.34, p < 0.001, validating the stimuli.

4.3.3. Procedure

Four hundred participants (51.3% female, Mage = 35.07, SD = 11.42) were recruited from Prolific in March 2025 to complete an online “retail website evaluation.” A priori power analysis (d = 0.35, α = 0.05) recommended at least 360 respondents; we oversampled to 400 to accommodate potential exclusions, but no cases failed the instructed-response attention check (“select ‘4’ for this item”). Participants were randomly assigned to view either the linear or accelerating landing page (between-subjects). After a mandatory 25 s exposure, they completed a three-item aesthetic-rating filler task (e.g., “The layout is visually appealing”) to reduce demand characteristics.

The manipulation check asked, “In this program, the rate at which points accumulate accelerates over time” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Perceived value of rewards was measured with three seven-point items adapted from Dose et al. (2019) [47] is program seem highly valuable,” “Earning rewards here feels worthwhile,” and “These rewards are attractive” (α = 0.90). Intended spending was assessed with three items adapted from prior loyalty research: “I would spend more money at ShopSquare next month,” “I am likely to increase my spending with this retailer,” and “I intend to allocate a larger share of my purchases to ShopSquare” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; α = 0.88). An alternative-explanation item captured perceived program complexity (“This loyalty program seems complicated,” 1 = not at all, 7 = extremely). All measures appeared in randomized order and were followed by demographics. The study protocol was approved by the University of Midtown Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained electronically. After applying attention checks, no participants were excluded from the analysis, as all participants passed the attention checks.

4.3.4. Results

Manipulation check. A one-way ANOVA showed a strong effect of points accumulation framework on perceived acceleration, F(1, 398) = 372.45, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.19; the accelerating condition (M = 5.90, SD = 1.02) was perceived as more accelerating than the linear condition (M = 2.85, SD = 1.15).

Dependent variable. Intended spending differed significantly across conditions, F(1, 398) = 27.08, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.06. Participants in the accelerating condition reported higher spending intentions (M = 5.30, SD = 1.22) than those in the linear condition (M = 4.62, SD = 1.31).

Perceived reward value. Perceived reward value was also higher under the accelerating framework (M = 5.72, SD = 1.05) than under the linear framework (M = 4.38, SD = 1.21), F(1, 398) = 115.76, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.13.

Perceived program complexity. The analysis showed that perceived program complexity did not differ significantly between the linear (M = 3.92, SD = 1.20) and accelerating (M = 3.85, SD = 1.22) conditions, F(1, 398) = 0.67, p = 0.413, η2 = 0.00.

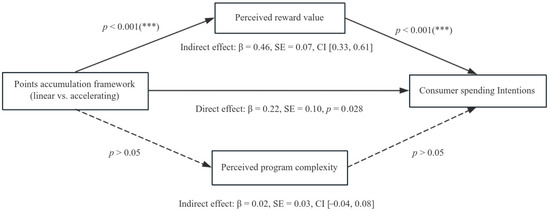

Mediation analysis. Hayes PROCESS Model 4 (5000 bootstrap samples; 95% CI) revealed a significant indirect effect of framework on spending intentions through perceived reward value (β = 0.46, SE = 0.07, CI [0.33, 0.61]). The direct effect of framework on spending fell but remained significant (β = 0.22, SE = 0.10, p = 0.028), indicating partial mediation. Incorporating perceived program complexity as an alternative mediator yielded a non-significant indirect path (β = 0.02, SE = 0.03, CI [−0.04, 0.08]), and the main indirect effect via reward value remained stable, supporting the proposed mechanism.

4.3.5. Discussion

Study 2 demonstrated that simply framing a loyalty program as accelerating rather than linear increased consumers’ intended spending, and this effect was largely explained by enhanced perceived value of the rewards. The absence of mediation by perceived complexity rules out the possibility that the results were driven by cognitive overload or ease of understanding.

4.4. Stage 3: Moderating Role of Temporal Discount Rate

4.4.1. Purpose

In study 3, we investigated the moderating role of temporal discount rate in the relationship between the points accumulation framework (linear vs. accelerating) and consumer decision-making (specifically, spending intentions).

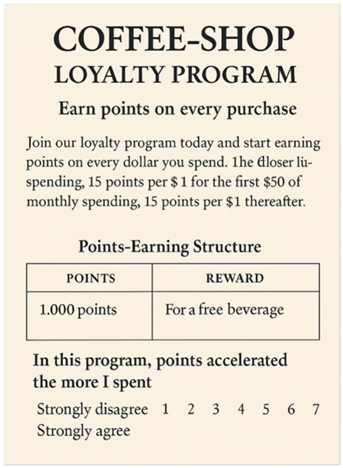

4.4.2. Stimuli and Pretest

Independent-variable stimuli were two fictitious coffee-shop loyalty brochures of identical length (165 words), layout, color palette, and reward table. Coffee shops represent a common context for loyalty programs, where consumers make frequent, relatively low-cost purchases [24]. This setting is ideal for studying consumer behavior in everyday contexts, where the effects of loyalty programs on spending intentions are likely to be more directly observable. The linear version stated that customers earned “10 points for every $1 spent,” whereas the accelerating version stated “5 points per $1 for the first $50 monthly spending, 15 points per $1 thereafter.” Both listed that 1000 points could be redeemed for a free beverage. A single manipulation-check item (“In this program, points accelerated the more I spent,” 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) captured perceived acceleration.

We manipulated temporal discounting in two conditions: high temporal discounting and low temporal discounting. Participants in the high temporal discounting condition were offered a choice between $5 immediately or $10 in 6 months. Participants in the low temporal discounting condition were offered a choice between $5 immediately or $50 in 6 months. These different reward structures were used to induce varying levels of temporal discounting, with the expectation that participants in the low temporal discounting condition would more likely choose the delayed reward. Temporal discount rate was measured with three seven-point items adapted from Kirgios and Zhao (2020) [48]: “I would rather receive $45 today than $60 in one month,” “Waiting one month for an extra 30% return is worthwhile” (reverse-scored), and “I prefer smaller-sooner to larger-later rewards” (α = 0.88). Higher scores indicated greater discounting (stronger preference for immediacy).

A pretest with 160 U.S. panelists (Mage = 36.9, 53% female) randomly assigned to one of the four cells confirmed both manipulations. Perceived acceleration was higher for the accelerating brochure (M = 6.21, SD = 0.79) than for the linear brochure (M = 2.18, SD = 1.01), t(158) = 26.91, p < 0.001. Perceived temporal discount rate was also significant (t(158) = 15.89, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.03), with participants in the low temporal discounting group (M = 3.07, SD = 0.98) showing a lower temporal discount rate compared to those in the high temporal discounting group (M = 5.58, SD = 0.90).

4.4.3. Procedure

400 U.S. adults were recruited via Prolific (52.5% female, Mage = 37.42, SD = 11.84) and randomly assigned to a 2 (points framework: linear vs. accelerating) × 2 (Temporal discount rate: low vs. high) between-subjects design. After consent, participants completed the two-minute reflection prime, read a 30 s filler article about urban gardening to reduce priming salience, and then viewed the assigned loyalty brochure for a minimum of 20 s. A 45 s word-search puzzle served as an unrelated distraction.

Next, respondents completed the single-item points-acceleration manipulation check and the temporal discount rate check (α = 0.89). The dependent variable, intended spending, was measured with three 7-point items adapted from prior spending intention research (“How much would you be willing to spend at BeanPerks next month?”; “How likely are you to increase your purchases at BeanPerks?”; “How large would your monthly coffee budget for BeanPerks be?”; 1 = very little/very unlikely/very small, 7 = very much/very likely/very large; α = 0.88). Attention was monitored with an instructed-response item; 12 participants failed and were replaced to maintain the target N. Finally, demographic questions were asked, and participants were debriefed.

4.4.4. Results

Manipulation check. A one-way ANOVA confirmed that perceived acceleration differed by brochure, F(1, 398) = 432.18, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.19 (Maccelerating = 6.18, SD = 0.82; Mlinear = 2.14, SD = 1.07). A separate ANOVA showed that the risk-tolerance prime affected financial risk propensity, F(1, 398) = 391.04, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.17 (Mhigh = 5.62, SD = 0.88; Mlow = 3.05, SD = 0.95).

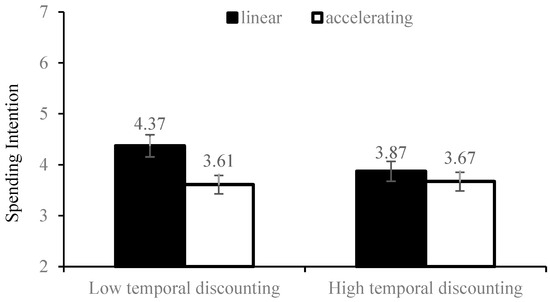

Temporal discount rate. A 2 × 2 ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of points framework, F(1, 398) = 21.76, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05, with accelerating programs lowering discounting (M = 3.64, SD = 1.04) relative to linear programs (M = 4.12, SD = 1.12). The main effect of temporal discount rate was also significant, F(1, 398) = 12.91, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.03; with participants in the low temporal discounting group (M = 3.70, SD = 1.10) showing higher spending intentions compared to those in the high temporal discounting group (M = 4.06, SD = 1.09). Crucially, the interaction was significant, F(1, 398) = 17.25, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.04 (see Figure 2). Low temporal discounting participants exhibited significantly higher spending intentions under the accelerating framework condition (M = 4.37, SD = 1.05) compared to the linear framework condition (M = 3.61, SD = 1.02), with markedly reduced discounting, F(1, 398) = 35.48, p < 0.001. Among high temporal discounting consumers, the same contrast was smaller and nonsignificant (Maccelerating = 3.67 vs. Mlinear = 3.87), F(1, 398) = 2.07, p = 0.151, demonstrating moderation (see Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Mediating Role of Perceived Reward Value.

Figure 3.

Moderating Role of Temporal Discount Rate.

4.4.5. Discussion

In Study 3, H3 was tested, and we found that the relationship between accelerating programs and perceived reward value was stronger for consumers with lower temporal discount rates. This aligns with Tsukayama and Duckworth (2010) [36], who showed that consumers with lower discount rates are more likely to value delayed rewards, and further extends research by Hardisty and Weber (2009) [39], who observed that those with lower discount rates are more responsive to reward structures with future benefits.

4.5. Stage 4: Moderating Role of Financial Risk Tolerance

4.5.1. Purpose

Study 4 investigated whether consumers’ financial risk tolerance moderates the impact of a loyalty program’s points accumulation framework on planned spending. Prior research suggests that accelerating rewards (earning disproportionately more points as spending grows) increase purchase motivation because they create a perception of faster progress toward a goal. However, consumers differ in their proclivity to embrace financially risky propositions. We predicted that the positive effect of an accelerating framework on intended spending would be stronger among high-risk-tolerant consumers, who are generally more comfortable with variable, performance-contingent returns, than among low-risk-tolerant consumers, who prefer stable, predictable outcomes.

4.5.2. Stimuli and Pretest

Points accumulation framework was manipulated with two fictitious but visually identical webpages for a coffeehouse loyalty program named “BeanPerks.” Each page contained the same logo, color palette, and 110 words describing membership benefits, differing only in the sentence explaining how points accrue. In the linear condition, the text read: “For every dollar you spend, you earn one point—consistently, every time.” In the accelerating condition, the parallel sentence stated: “For every dollar you spend, you earn one point, but once you reach 100 points you earn two points per dollar, and after 300 points you earn three points per dollar.” (see Appendix C) Readability (Flesch–Kincaid grade = 7.1) and valence (VADER compound = 0.61) were equated. Perceived reward acceleration was assessed with a 7-point item (“The rate at which points increase in this program is: 1 = very slow, 7 = very fast”).

Financial risk tolerance was experimentally manipulated with a three-minute writing prime adapted from Weber et al. (2002) [39]. In the high-risk-tolerance version, participants recalled and described three occasions when taking a financial risk paid off, then indicated how comfortable they had felt on a 7-point scale. In the low-risk-tolerance version, they recalled three occasions when avoiding a financial risk was the smarter choice and rated their comfort. Both prompts required 120 words minimum to maintain cognitive load symmetry. Manipulation effectiveness was captured with a single item (“Right now I feel comfortable taking financial risks”) on the same 7-point scale.

A separate pretest recruited 160 U.S. adults from Prolific (52% female; Mage = 36.2, SD = 11.4). Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four cells (n = 40). A t-test confirmed that the accelerating webpage conveyed stronger perceived reward acceleration (M = 6.19, SD = 0.83) than the linear webpage (M = 2.81, SD = 1.04), t (158) = 21.35, p < 0.001. A second t-test showed that the risk prime operated as intended: high-risk-tolerant respondents felt more comfortable with financial risks (M = 5.88, SD = 0.84) than low-risk-tolerant respondents (M = 3.02, SD = 0.97), t(158) = 18.97, p < 0.001. No interaction emerged for either check (Fs < 1), confirming orthogonality.

4.5.3. Procedure

The main experiment employed a 2 (points framework: linear vs. accelerating) × 2 (financial risk tolerance: low vs. high) between-subjects design. Four hundred U.S. adults were recruited via Prolific (50.3% female; Mage = 38.9, SD = 12.6) and randomly assigned to one of the four conditions (n = 100 each). Participants completed the appropriate risk-tolerance writing task. They then viewed the assigned BeanPerks webpage for at least 25 s; a disguised two-minute puzzle served as a distraction. After that, participants indicated their perceived reward acceleration (1 item, as above) and momentary financial risk tolerance (1 item, α not applicable). The dependent variable, intended spending, was measured with three 7-point items adapted from prior spending intention research (“How much would you be willing to spend at BeanPerks next month?”; “How likely are you to increase your purchases at BeanPerks?”; “How large would your monthly coffee budget for BeanPerks be?”; 1 = very little/very unlikely/very small, 7 = very much/very likely/very large; α = 0.88). Finally, respondents completed demographic items and an attention-check question before debriefing. After applying attention checks, no participants were excluded from the analysis, as all participants passed the attention checks.

4.5.4. Results

Manipulation check for points framework. A one-way ANOVA revealed that participants in the accelerating condition perceived a faster points increase (M = 6.10, SD = 0.91) than those in the linear condition (M = 2.93, SD = 1.02), F(1, 398) = 862.34, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.18.

Manipulation check for financial risk tolerance. A separate one-way ANOVA confirmed higher risk-comfort ratings in the high-risk-prime condition (M = 5.80, SD = 0.88) relative to the low-risk-prime condition (M = 3.12, SD = 1.01), F(1, 398) = 731.20, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.16.

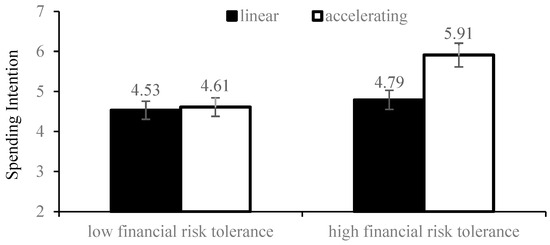

Intended spending. A 2 × 2 ANOVA on the spending index showed main effects of points framework, F(1, 398) = 17.23, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.04, and financial risk tolerance, F(1, 398) = 8.67, p = 0.003, η2 = 0.02, qualified by a significant interaction, F(1, 398) = 21.45, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05. Among high-risk-tolerant participants, accelerating rewards increased intended spending (M = 5.91, SD = 0.90) compared with linear rewards (M = 4.79, SD = 1.05), F(1, 398) = 32.81, p < 0.001. Among low-risk-tolerant participants, the same contrast was nonsignificant (Maccelerating = 4.61, SD = 1.10 vs. Mlinear = 4.53, SD = 0.98), F(1, 398) = 0.41, p = 0.523. Simple-effects findings support the predicted pattern (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Moderating Role of Financial Risk Tolerance.

4.5.5. Discussion

The results revealed that financial risk tolerance moderated the effect of points framework on spending intentions, with high-risk-tolerant consumers showing a significantly stronger relationship between accelerating frameworks and increased spending. This supports Rolison and Shenton (2020) [41], who found that financial risk tolerance shapes how individuals respond to reward-based systems, and Li et al. (2015) [42], who noted that high-risk consumers are more likely to engage with uncertain but high-reward scenarios.

5. General Discussion

This research investigated how the structure of retail loyalty programs—specifically comparing linear versus accelerating points accumulation frameworks—influences consumer spending behavior. Through four experimental studies, we established a consistent effect and identified both mediating and moderating mechanisms (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of study designs. All experiments were conducted on the Instagram platform.

In Study 1, we demonstrated that an accelerating points accumulation framework (where points earned per dollar increase with spending) led to significantly higher spending intentions compared to a traditional linear framework (constant points per dollar). This finding resonates with prior research showing that tiered or progressive reward schemes can increase consumer motivation [21,27]. However, our study extends this work by showing that even when the objective redemption thresholds remain identical (100 points for a free drink), the perception of accelerating returns alone is sufficient to stimulate spending behavior. The substantial effect size (η2 = 0.10) highlights practical significance for retail managers, supporting meta-analytic evidence that well-designed loyalty programs can generate sizable revenue improvements [25].

Study 2 replicated this main effect using a different retail context (e-commerce) and identified the mediating role of perceived reward value. While previous studies have emphasized fairness, transparency, or program complexity as drivers of consumer response [31,49], our findings demonstrate that the critical mechanism lies in how consumers assess the value of rewards rather than the complexity of program design. Mediation analysis showed that higher perceived reward value partly explains the spending uplift under accelerating frameworks, ruling out perceived program complexity as an alternative explanation. This provides more precise evidence than prior work by clarifying that motivation—not cognitive load—drives program effectiveness, thereby advancing theoretical understanding of consumer engagement with loyalty programs.

Study 3 expanded our investigation to explore how loyalty program structure influences temporal discount rates. We found that an accelerating points framework reduced consumers’ preference for immediate rewards, but this effect was moderated by financial risk tolerance. Particularly, accelerating framework effectiveness in lowering temporal discounting was more pronounced in consumers who were low in risk tolerance but weakened in those high in risk tolerance. It appears that accelerating programs can be especially effective in combating present-bias among consumers who are averse to financial risks.

Lastly, Study 4 investigated financial risk tolerance more directly as a moderator of the relationship between points accumulation structure and spending intentions. Previous research has noted consumer heterogeneity in loyalty program responses [50,51], but few studies have empirically tested risk tolerance in this context. Our findings demonstrate that accelerating frameworks significantly increase spending intentions among consumers with high financial risk tolerance but show no effect among risk-averse consumers. This aligns with Prospect Theory’s emphasis on individual risk preferences [14] and complements recent evidence that risk tolerance shapes consumer financial decisions [41,43]. This type of moderation suggests that financial risk orientation differences among consumers are substantially engaged in the determination of responsiveness to program design.

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

This study makes several important theoretical contributions to the literature on loyalty programs, consumer psychology, and behavioral decision-making. First, it integrates Prospect Theory with the concept of psychological distance to explain how the design of loyalty programs shapes consumer spending. By demonstrating that accelerating frameworks reduce perceived temporal distance and enhance reward salience, our research advances a more nuanced understanding of how individuals evaluate future versus immediate gains in loyalty contexts, thereby extending Prospect Theory beyond its traditional financial and risk-based applications [39,52,53].

Second, the study identifies perceived value of rewards as a pivotal mediator in the relationship between program design and consumer spending behavior. While prior loyalty program research has emphasized structural features (e.g., tiered vs. linear), our findings highlight that the psychological appraisal of reward value—not complexity or transparency—drives consumer engagement. This contribution aligns with and extends existing literature on value perception [9,11], offering a theoretically grounded explanation of why accelerating frameworks are particularly effective in stimulating spending.

Third, the research establishes financial risk tolerance as a critical boundary condition that moderates the effect of loyalty program structures. Specifically, consumers high in financial risk tolerance respond more strongly to accelerating frameworks, while risk-averse consumers are less influenced. By incorporating individual-level risk preferences into the study of loyalty programs, this work expands the scope of marketing and consumer behavior research, bridging insights from behavioral economics and consumer psychology [41,43,54].

5.2. Practical Contribution

This study provides useful practical implications for loyalty program managers, marketers, and retailers aiming to maximize consumer expenditures. The findings confirm that accelerating points accumulation structures, compared with linear ones, significantly increase spending intentions even when redemption thresholds remain constant. This means that firms can stimulate incremental purchases simply by reframing reward progression, without changing the overall value of rewards. Because this redesign is low in implementation cost but high in motivational impact, it represents a practical and scalable approach for retailers, e-commerce platforms, and service providers seeking to enhance customer engagement and boost long-term profitability.

The results further demonstrate that the perceived value of rewards is the central psychological mechanism driving program effectiveness. When consumers believe that rewards become increasingly valuable as they continue spending, their motivation to engage with the program rises significantly. This insight directs managers to design communication that emphasizes progression in value rather than focusing on technical program details or tier structures. Instead of highlighting how many points equal a voucher, firms should stress the accelerating payoff of continued participation, creating a sense that each additional purchase brings disproportionately greater benefits. To operationalize this, managers can craft marketing messages that use clear, motivational phrasing such as “the more you spend, the faster your rewards grow.” Digital platforms provide additional opportunities: loyalty apps can display visual progress indicators that accelerate as spending increases, interactive dashboards can showcase upcoming milestones, and gamification elements can transform the accumulation process into a journey of achievement [55,56]. Such tools not only make accelerating benefits more salient but also sustain consumer engagement over time by providing psychological reinforcement [57]. Moreover, by demonstrating that program complexity does not drive engagement—whereas perceived value does—our findings caution against overengineering loyalty programs. Instead, managers should prioritize simplicity in structure but richness in perceived benefits, ensuring that consumers clearly understand and appreciate the accelerating nature of rewards [58].

Finally, the study highlights the importance of consumer heterogeneity and cultural context in loyalty program design. Financial risk tolerance shapes how consumers interpret accelerating versus linear structures: risk-tolerant consumers respond strongly to accelerating programs because they embrace variability, whereas risk-averse consumers prefer stability and predictable progress. These differences call for tailored communication strategies—for example, emphasizing security and certainty in risk-averse markets, while stressing potential gains and progress speed in risk-tolerant segments. Beyond individual differences, cultural and sectoral variations further influence program effectiveness, meaning that global brands must adapt designs and messages to local preferences. By recognizing and leveraging these nuances, managers can create loyalty programs that are not only efficient but also responsive to diverse consumer needs across markets.

5.3. Limitation

A number of constraints qualify these findings from being interpreted as generalizable to real-world contexts, including: First, all studies used hypothetical contexts and self-reports of spending intentions, as opposed to measuring actual buying behavior in real-world purchasing contexts. This poses a fundamental concern for ecological validity, as the reliance on intentions rather than real expenditures may limit the extent to which causal pathways and impacts can be transferred to natural consumption environments [59,60]. Future work should therefore prioritize field experiments, or longitudinal measurement of actual expenditures, to test causal mechanisms as well as points accumulation framework impacts in real-world contexts. Second, subjects were recruited through crowdsourcing websites, again primarily from American consumer panels, limiting generalizability across cultural settings, where loyalty program standards as well as risk thresholds may vary [61]. Cross-cultural field tests as well as sector-specific re-tests are required to determine boundary constraints. Third, although perceived reward value was found to be a first-order mediator, no direct testing was conducted on alternative psychological drivers, such as anticipated regret or signaling of higher social standing, that may be additional mediators of these impacts. In loyalty settings, anticipated regret may influence consumer engagement, as individuals seek to avoid the negative emotions associated with missing potential rewards, thereby reinforcing program participation. Likewise, social status signaling may heighten the perceived attractiveness of rewards when benefits also serve as public indicators of prestige or exclusivity, a factor particularly relevant in competitive or status-sensitive markets. Neglecting these mechanisms risks underestimating the motivational complexity underlying program responsiveness. Future studies need to utilize multi-method strategies to isolate these further mediators.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and J.F.; methodology, H.Z.; formal analysis, A.U.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, J.F.; supervision, J.F.; funding acquisition, J.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [the National Social Science Fund of China General Project (Grant No. 20BSH103)], [the Chengdu Philosophy and Social Science Research Base (Grant No. LD2024Z10)], and [the Soft Science Research Project of Chengdu Science and Technology Bureau (2025) (Grant No. 2025-RK00-00216-ZF)].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Southwest Jiaotong University, with the approval number IRB-2025-SEM-0702B.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All the data can be found in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Stimuli Used in Study 1

| Present Gamification Elements in Sustainability Apps | Absent Gamification Elements in Sustainability Apps |

|  |

Appendix B. Stimuli Used in Study 2

| Present Gamification Elements in Sustainability Apps | Absent Gamification Elements in Sustainability Apps |

|  |

Appendix C. Stimuli Used in Study 3

| Present Gamification Elements in Sustainability Apps | Absent Gamification Elements in Sustainability Apps |

|  |

References

- Loyalty Program Statistics—2024 Data and Reports. Available online: https://www.couponbirds.com/research/loyalty-program-statistics (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Do Loyalty Programs Really Work? What the Research Says. Available online: https://www.tremendous.com/blog/how-loyalty-programs-work/ (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Nishio, K.; Hoshino, T. Joint Modeling of Effects of Customer Tier Program on Customer Purchase Duration and Purchase Amount. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.X.; Irina, Y.Y.; Chan, H.; Zeng, K.J. Retain or Upgrade: The Progress-Framing Effect in Hierarchical Loyalty Programs. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stourm, V.; Bradlow, E.T.; Fader, P.S. Stockpiling Points in Linear Loyalty Programs. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 52, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.L.; Song, T.H. Nonlinear Reward Gradient Behavior in Customer Reward and Loyalty Programs: Evidence from the Restaurant Industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2025, 49, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.; Alzoubi, H. Loyalty Program Effectiveness: Theoretical Reviews and Practical Proofs. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2020, 8, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carluccio, J.; Eizenman, O.; Rothschild, P. Next in Loyalty: Eight Levers to Turn Customers into Fans; McKinsey & Company: New York City, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Melancon, J.P.; Noble, S.M.; Noble, C.H. Managing Rewards to Enhance Relational Worth. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryanto, A.; de Ruyter, K.; Wetzels, M.; Patterson, P.G. Service Firms and Customer Loyalty Programs: A Regulatory Fit Perspective of Reward Preferences in a Health Club Setting. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, L.; Russell-Bennett, R.; Mulcahy, R. Reward-Based or Meaningful Gaming? A Field Study on Game Mechanics and Serious Games for Sustainability. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 981–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Jeon, H.; Choi, B. Segregation vs. Aggregation in the Loyalty Program: The Role of Perceived Uncertainty. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 1238–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Malerba, F. Catch-up Cycles and Changes in Industrial Leadership: Windows of Opportunity and Responses of Firms and Countries in the Evolution of Sectoral Systems. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, T. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decisions Under Risk; University of Rochester, Graduate School of Management, Managerial Economics Research Center: Rochester, NY, USA, 1979; pp. 263–291. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. A Theory of Goal Setting & Task Performance; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, K.; Guhl, D.; Klapper, D.; Spann, M.; Stich, L.; Yegoryan, N. Behavioral Biases in Marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 449–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mandler, T.; Meyer-Waarden, L. Three Decades of Research on Loyalty Programs: A Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivetz, R. Promotion Reactance: The Role of Effort-reward Congruity. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 31, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Huang, S.-C. Been There, Done That: The Impact of Effort Investment on Goal Value and Consumer Motivation. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 38, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, L.; Holston, D.; Long, A. Modeling Behavioral Economic Strategies in Social Marketing Messages to Promote Vegetable Consumption to Low-Resource Louisiana Residents: A Conjoint Analysis. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 122, A21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagengast, L.; Evanschitzky, H.; Blut, M.; Rudolph, T. New Insights in the Moderating Effect of Switching Costs on the Satisfaction–Repurchase Behavior Link. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 408–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, N.U.; Frohlich, N.; Bruning, E. The Influence of Involvement on the Endowment Effect: The Moveable Value Function. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zushi, N.; Curlo, E.; Thomas, G.P. The Reflection Effect in Time-Related Decisions. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 793–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Lindsey-Mullikin, J. The Moderating Role of the Price Frame on the Effects of Price Range and the Number of Competitors on Consumers’ Search Intentions. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belli, A.; O’Rourke, A.-M.; Carrillat, F.A.; Pupovac, L.; Melnyk, V.; Napolova, E. 40 Years of Loyalty Programs: How Effective Are They? Generalizations from a Meta-Analysis. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, T.; Hayduk, T.; Lock, D. Push It Real Good: The Effects of Push Notifications Promoting Motivational Affordances on Consumer Behavior in a Gamified Mobile App. Eur. J. Mark. 2023, 57, 2592–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeira, M.; Pontes, N.; Thomas, D.; Krishnan, S. Framing as Status or Benefits? Consumers’ Reactions to Hierarchical Loyalty Program Communication. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 488–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D. The State of the Art in Privacy Impact Assessment. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2012, 28, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesel, P.; Zabkar, V. Relationship Quality Evaluation in Retailers’ Relationships with Consumers. Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 1334–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddodi, C.B.; Upadhyaya, P. Are Animated In-App Banner Ads Intrusive? Examining the Interplay of Structural and Semantic Ad Factors. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, D.I.; Daryanto, A.; de Ruyter, K.; Wetzels, M. Take It or Leave It: Using Regulatory Fit Theory to Understand Reward Redemption in Channel Reward Programs. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 42, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.-C.; Tseng, Y.-F. Research Note: E-Store Image, Perceived Value and Perceived Risk. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, H.-H.; Yang, P.-H.; Chang, C.-L. Reminding Customers to Be Loyal: Does Message Framing Matter? Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 783–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslanagic-Kalajdzic, M.; Zabkar, V. Is Perceived Value More than Value for Money in Professional Business Services? Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 65, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Y.; Li, C.; Peng, S. The Effect of Matching Strategies and Advertising Performance: The Roles of Perceived Goal Progress and Customer Search Behaviors. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukayama, E.; Duckworth, A.L. Domain-Specific Temporal Discounting and Temptation. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2010, 5, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, G.B. Temporal Discounting and Utility for Health and Money. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 1996, 22, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-Level Theory of Psychological Distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardisty, D.J.; Weber, E.U. Discounting Future Green: Money versus the Environment. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2009, 138, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaskill, A.C.; Hunt, M.J.; Milfont, T.L. On the Associations between Delay Discounting and Temporal Thinking. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 141, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolison, J.J.; Shenton, J. How Much Risk Can You Stomach? Individual Differences in the Tolerance of Perceived Risk across Gender and Risk Domain. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2020, 33, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sang, Z.; Zhang, Z. Expressive Suppression and Financial Risk Taking: A Mediated Moderation Model. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 72, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechler, C.J.; Lutfeali, S.; Huang, S.; Morris, J.I. Working Hard for Money Decreases Risk Tolerance. J. Consum. Psychol. 2024, 34, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Basic but Frequently Overlooked Issues in Manuscript Submissions: Tips from an Editor’s Perspective. J. Appl. Bus. Behav. Sci. 2025, 1, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G* Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterbring, T.; Wu, F.; Kristensson, P. Too Close for Comfort? The Impact of Salesperson-Customer Proximity on Consumers’ Purchase Behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 1576–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dose, D.B.; Walsh, G.; Beatty, S.E.; Elsner, R. Unintended Reward Costs: The Effectiveness of Customer Referral Reward Programs for Innovative Products and Services. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 47, 438–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirgios, E.L.; Chang, E.H.; Levine, E.E.; Milkman, K.L.; Kessler, J.B. Forgoing Earned Incentives to Signal Pure Motives. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 16891–16897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisjak, M.; Bonezzi, A.; Rucker, D.D. How Marketing Perks Influence Word of Mouth. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmark, C.L.; Noble, S.M.; Bell, J.E. Open versus Selective Customer Loyalty Programmes. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 770–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, S.; Gao, Y.; Rabbanee, F.K. Status Demotion in Hierarchical Loyalty Programs and Customers’ Revenge and Avoidance Intentions. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 363–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Editorial–What Is an Interactive Marketing Perspective and What Are Emerging Research Areas? J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Demonstrating Contributions through Storytelling. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025, 19, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, J.; Hao, A. Effects of Vividness, Information and Aesthetic Design on the Appeal of Pay-per-Click Ads. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 848–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Xue, F.; Barton, M.H. Visual Attention, Brand Personality and Mental Imagery: An Eye-Tracking Study of Virtual Reality (VR) Advertising Design. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, S.; Duan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Meng, L. The Impact of Visual Perspectives in Advertisements on Access-Based Products. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Kou, S.; Duan, S.; Jiang, Y.; Lü, K. How a Blurry Background in Product Presentation Influences Product Size Perception. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1633–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, K.; Donnell, L.V.; Gilmore, A.; Reid, A. Loyalty Card Adoption in SME Retailers: The Impact upon Marketing Management. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 467–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaway, A.W.; Gooner, R.M.; Berkowitz, D.; Davis, L. Deriving and Exploring Behavior Segments within a Retail Loyalty Card Program. Eur. J. Mark. 2006, 40, 1317–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.; Huan, T.-C.T.; Xu, Y.; Nam, I. Extending Prospect Theory Cross-Culturally by Examining Switching Behavior in Consumer and Business-to-Business Contexts. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).