Abstract

In recent years, scandals regarding the malpractices of many nonprofit organizations (NPOs) for selfish ends have eroded public trust in them. Therefore, it is necessary to consider whether the credibility of NPOs, as one of the three key implementers in cause-related marketing (CRM) campaigns, has a transfer effect on enterprise brand image. The aim of the current study is to examine the relationship between NPO credibility and enterprise brand image, along with its underlying mechanism and boundary conditions. Drawing on the affect-transfer model as well as attribution theory, we propose a theoretical model. This model highlights the mediating role of perceived corporate hypocrisy in the relationship between NPO credibility and enterprise brand image. Moreover, it incorporates public emergency, specifically in reference to the COVID-19 pandemic, as a moderator. Three experiments were conducted to test our model. Results reveal that consumers perceive a more negative enterprise brand image when the company partners with a low-credibility NPO compared to a high-credibility NPO. Additionally, the impact of NPO credibility on enterprise brand image is mediated by perceived corporate hypocrisy, which is weakened in the presence of a public emergency.

1. Introduction

Cause-related marketing (CRM), a marketing strategy that benefits the company, its customers and the cause of charity simultaneously, has maintained its popularity in marketing [1,2]. According to the 2025 Cause-Related Marketing Guide released by Labyrinth Inc., in 2022 alone, corporate donations through CRM campaigns reached USD 21 billion, with an annual growth rate of 13.4% [3]. These CRM initiatives span multiple sectors, including hospitality, retail, and e-commerce, with companies such as Marriott, 7-Eleven, and Alibaba participating [3,4]. In a CRM campaign, the nonprofit organization (NPO) serves as a crucial partner for the company, executing specific charitable projects or activities and profoundly influencing the effectiveness of the CRM campaign. However, a series of scandals and corruption incidents involving global NPOs has frequently come to light, undermining public perception of charitable causes and posing significant obstacles to the development of the charity industry [5]. For example, the American Heart Association’s “Heart-Check” program, designed to guide consumers toward heart-healthy food choices, included certified products that nevertheless contained high levels of sugar, salt, or saturated fat. This severely weakened the credibility of the NPO, elicited public backlash, and drew criticism as “greenwashing” [6]. Consequently, the credibility crisis faced by NPOs may hinder the smooth implementation of CRM practices.

The antecedents of CRM effectiveness have long been a focal point of scholarly attention. Existing research has primarily examined three categories of factors: consumer-related traits, execution-related factors, and product-related traits [7]. These studies suggest that CRM campaigns tend to be more effective when consumers are relatively familiar with the campaign, the promoted products are more utilitarian in nature, and the donation amounts are larger [2,8]. However, despite being a critical partner in corporate CRM initiatives, the characteristics of NPOs and their influence on CRM effectiveness have received limited attention. Moreover, NPO credibility is widely regarded as a key determinant for the success of CRM campaigns. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the impact of the credibility of NPOs collaborating with companies in a CRM context on corporate brand image. Furthermore, it explores the underlying mechanisms and boundary conditions of this relationship, thereby addressing the gap in the existing literature.

To achieve this objective, we propose exploring how NPO credibility impacts enterprise brand image through consumers’ perception of corporate hypocrisy. Corporate hypocrisy refers to the belief that a company claims to be something it is not [9]. According to previous research in corporate social responsibility (CSR), consumers respond negatively if they observe a significant discrepancy between a company’s declared CSR concept and their actual social responsibility actions, perceiving this as hypocritical [9,10]. By exploring the mediating role of perceived corporate hypocrisy in this research, we gain deeper insights into the impact of NPO credibility on CRM effectiveness. In other words, when a company announces its support for a particular cause or charitable project but partners with a low-credibility NPO, consumers’ lack of trust and confidence in the NPO will transfer to the cooperating company and its brand image due to the enhanced perception of word–deed misalignment and corporate hypocrisy.

Previous studies suggest that public emergencies (e.g., natural disasters) are crucial factors that can mitigate or reverse the negative consequences of word–deed misalignment in the CRM context [10]. Crises fundamentally reshape consumer attributions [11]: in the face of external crises, consumers are more likely to attribute corporate collaborations with low-credibility NPOs to situational constraints rather than opportunistic motives, thereby increasing their tolerance [12]. At the same time, public emergencies heighten consumers’ identification with the cause and evoke stronger moral emotions, such as moral elevation [13]. Such contexts also promote collective solidarity and empathy [14], further dampening consumers’ sensitivity to hypocrisy. Therefore, this study incorporates the COVID-19 pandemic as a moderating factor and posits that, in the context of public emergencies, the transfer effect of NPO credibility on corporate brand image is attenuated.

In the current study, we extend the CRM literature by not only examining how NPO credibility influences the enterprise brand image, but also exploring the mediating role of perceived corporate hypocrisy and the moderating role of public emergency. Three experimental studies were conducted to examine our hypotheses. Experiment 1 tests our prediction that, compared to a high-credibility NPO, consumers perceive a more negative enterprise brand image when the company partners with a low-credibility NPO. Experiment 2 tests whether perceived corporate hypocrisy mediates the relationship between NPO credibility and enterprise brand image. Experiment 3 tests the moderating role of public emergency on the relationship between NPO credibility and enterprise brand image, and the potential mediating role of perceived corporate hypocrisy in this relationship. In addition, to provide evidence of the overall strength of the above three studies, we conducted a single-paper meta-analysis.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Affect-Transfer Model

The affect-transfer model, originally used in brand extension research, postulates that consumers would transfer their attitudes about the parent brand to its extensions [15]. Subsequently, researchers have delved into how impressions of one brand are transferred or influenced by impressions of other strategically linked brands, a phenomenon known as the transfer effect in brand alliances [16]. Because consumers often believe that only high-quality products form alliances with other products of equal caliber, and they are aware that managers are driven to protect their product’s reputation from being tarnished by unfavorable alliances [17]. Consequently, when an unknown brand collaborates with a well-known brand, the lesser-known brand often benefits from a positive joint main effect due to the “transfer effect” of the renowned brand. Conversely, the established brand often experiences a negative joint main effect due to the “dilution effect” of the lesser-known brand. Essentially, well-known brands act as positive contextual cues, leading consumers to infer that the unknown brand shares the same quality standards through a process of assimilation [16].

Researchers have found that the reputation of a charitable organization can be transferred to its associated private enterprise. For instance, Huang and Wang discovered that the reputation damage of government-owned charitable organizations results in reputation punishment, leading to a significant decrease in the donation amount of private enterprises that collaborate with them, and this effect also extends to private charitable organizations [18]. Although previous research has indirectly shown the positive impact of NPO credibility on enterprise brand image, it has not delved into the underlying mechanism and boundary conditions that enable NPO credibility to positively influence enterprise brand image. Next, we elaborate on the mediating effect of perceived corporate hypocrisy and moderating effect of public emergency (i.e., COVID-19) in this transfer effect.

2.2. NPO Credibility and Enterprise Brand Image

Organization credibility refers to the public’s overall perception of an organization’s trustworthiness and reliability, reflecting the degree to which the organization is trusted to fulfill its stated objectives [19]. For NPO, credibility constitutes a valuable intangible asset that plays a crucial role in shaping donation decisions and public evaluations [20]. In CRM campaigns, enterprises and NPOs jointly design and implement public welfare activities, which require resource sharing and indicate mutual endorsement [21]. From a consumer standpoint, a company’s choice of NPO partner serves as a signal of its corporate responsibility and alignment with societal values [22,23].

Based on the affect transfer model and the findings related to emotional responses, it is evident that consumers not only evaluate NPO credibility in isolation but also take into account how the attributes of NPO influence their perception of the corporate partner [18]. This transfer of emotion stems from the association between the NPO’s reputation and the corporate brand, wherein consumers may project the positive or negative attributes of the NPO onto the company itself [22]. Consequently, the credibility of NPO becomes a salient cue that consumers use to evaluate both the effectiveness of CRM campaign and the corporate brand image. Thus, negative incidents such as scandals, corruption, or mismanagement can severely undermine public trust in NPOs, and these negative perceptions may spill over to the corporate partner, leading to unfavorable evaluations of the CRM campaign and the corporate brand image [18]. Conversely, alignment with highly reputable NPOs cultivates favorable attitudes toward the CRM campaign, and enhances the corporate brand image [24]. In summation, NPO credibility functions as a double-edged sword: collaborating with reputable NPOs exerts a positive influence on the corporate brand image, whereas partnering with low-credibility NPOs may harm it.

H1.

Consumers perceive a more negative enterprise brand image when the company partners with a low-credibility NPO compared to a high-credibility NPO.

2.3. Mediating Effect of Perceived Corporate Hypocrisy

Perceived corporate hypocrisy refers to the perception that corporations claim to possess moral and virtuous qualities they do not actually have, has become an increasing concern in both academic and practical circles [25]. Prior research suggests that inconsistencies in corporate social responsibility (CSR) information can elicit consumer perceptions of hypocrisy, which subsequently shape attitudes toward the company [9]. Moreover, a misalignment between a company’s CSR image and its CRM initiatives can intensify such perceptions. For instance, Ju et al. suggested that when a company’s business activities had a negative impact on a particular area (i.e., a tainted company), and it attempted to display positive behavior in that area, people were more likely to question its true motives [26].

Building on these insights, we argue that the credibility of the NPO involved in a CRM campaign plays a critical role. According to attribution theory, individuals often infer the causes of observed outcomes by attributing them to internal dispositions or external circumstances [27,28]. When a company collaborates with a low-credibility NPO, consumers may doubt the ability of NPO to translate the company’s promises into concrete outcomes. This perceived execution risk highlights a discrepancy between the company’s stated intentions and the expected results, which can trigger consumers to make internal attributions regarding the company’s motives. Consumers are likely to attribute the initiative to the company’s self-interest rather than to genuine concern for social impact. Consequently, such internal attributions increase the perception of hypocrisy, as consumers interpret the company’s words and actions as misaligned. Furthermore, if consumers form the impression that these activities are publicity stunts or self-serving, such actions can result in a deterioration of the company’s image [29]. Therefore, we hypothesize that collaborations with low-credibility NPOs in CRM campaigns will lead consumers to perceive the company as engaging in showmanship or self-serving behavior, thereby fostering higher perceptions of hypocrisy and, ultimately, a worse brand image.

H2.

The impact of NPO credibility on enterprise brand image is mediated by perceived corporate hypocrisy.

2.4. Moderating Effect of Public Emergency

Public emergencies are unexpected events, including natural disasters, accidents, public health crises, and social security incidents, which can cause substantial social harm and require urgent interventions [30]. In the study of CRM, public emergencies are crucial external environmental factors that shape consumers’ reactions [31,32]. For instance, consumers tend to exhibit higher tolerance for CSR failures during sudden natural disasters or financial crises compared to crises initiated by the company itself, and are more likely to support corporate actions that help alleviate their concerns [33]. Furthermore, Zheng et al. found that when the cause involves a sudden disaster rather than an ongoing tragedy, consumers experience stronger moral sentiments, leading to more favorable attitudes toward products associated with such charity campaigns [34].

In recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly affected the world, resulting in numerous casualties and significant economic losses [35,36]. Given this context, the present study predicts that the COVID-19 pandemic will influence the relationship between NPO credibility and corporate brand image. Specifically, in the face of external crises, consumers are more likely to attribute corporate collaborations with low-credibility NPOs to situational constraints rather than opportunistic motives, increasing their tolerance [12]. At the same time, public emergencies enhance consumers’ identification with the cause and evoke stronger moral emotions, such as moral elevation [13], which reduces sensitivity to perceived hypocrisy and thereby mitigates the negative impact of low-credibility NPOs on corporate brand image.

H3.

The impact of NPO credibility on enterprise brand image is weakened in the presence of public emergency.

H4.

Perceived corporate hypocrisy mediates the interactive effects of NPO credibility and public emergency on enterprise brand image.

3. Empirical Studies

To bolster our predictions, we undertook three experimental studies, which were complemented by a single-paper meta-analysis. The experimental scenarios were systematically developed to simulate genuine CRM campaigns conducted on leading e-commerce platforms (e.g., Gongyi Baobei Campaign). Our participants were predominantly sourced from either a major university or the Credamo professional survey platform in China. A detailed overview of the participants’ demographics (e.g., gender, age, political status and disposable income) is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of participants of three experiments.

3.1. Experiment 1

In Experiment 1, we tested our prediction that consumers perceive a more negative enterprise brand image when the company partners with a low-credibility NPO compared to a high-credibility NPO (e.g., test H1).

3.1.1. Participants, Procedure and Stimuli

140 undergraduate students from a major university in China participated in Experiment 1, and nine participants were excluded due to incomplete or invalid data. After completing the experiment, participants would receive one gift. Participants were randomly assigned to a three-page booklet. On the first page, they were asked to envision purchasing a notebook and were told that the Xilin Stationery Company was selling a notebook. To mitigate the influence of the participants’ existing attitudes, we used a corporate brand (Xilin) and an NPO (Liqi Foundation), both of which are virtual, and designed the experimental context with reference to real CRM campaigns. Then, participants were provided with a brief description of the notebook, including its color, size, and price. They were informed that “2% of the sales of this notebook will be donated to the Liqi Foundation for purchasing school supplies for children in poor areas.” Subsequently, we manipulated the NPO credibility through three aspects, establishment time, historical experience in CSR, and future development, as shown in Table 2 [37].

Table 2.

Stimuli for Experiment 1.

On the second page, we required all participants to complete measurements for the dependent variable, control variables, and manipulated variable. The corporate brand image was measured through brand attitude and evaluation, using four items (Cronbach’s α = 0.87), such as “Do you think Xilin is a good brand?”, with 1 = “Strongly disagree” and 5 = “Strongly agree” [38]. We also measured two control variables to test their effects on the dependent variable: participation experience in relevant charity campaigns and the perceived importance of the donation [34]. Additionally, participants also responded to their perception of NPO credibility, using six items (Cronbach’s α = 0.95), such as “Do you think Liqi Foundation is honest?”, with 1 = “Strongly disagree” and 5 = “Strongly agree” [39]. On the third page, participants reported their socio-demographic information, such as gender, age, political status, and disposable income.

3.1.2. Analysis and Results

Manipulation checks for NPO credibility: A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine the impact of perceived NPO credibility as the dependent variable. The results were highly significant (Mlow = 3.02, Mhigh = 3.92; F(1, 130) = 51.18, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.28). This provides confirmation that the manipulation of NPO credibility in Experiment 1 was successfully implemented.

The impact of NPO credibility on enterprise brand image: The results of our ANOVA analysis revealed that, while participation experience in relevant charity campaigns had minimal impact on enterprise brand image (p = 0.80), the perceived importance of the donation was a significant factor (p < 0.001). When controlling for these two variables, we found that a partnership with a low-credibility NPO led to a more negative perception of the enterprise brand image among consumers (Mlow = 3.45, Mhigh = 3.91; F(1, 130) = 14.35, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.10). This provides strong support for Hypothesis 1, which posited that NPO credibility would significantly impact the enterprise brand image.

3.2. Experiment 2

In the second study, our primary objective is to examine whether the influence of NPO credibility on the corporate brand image is mediated by corporate hypocrisy (e.g., test H2).

3.2.1. Participants, Procedure and Stimuli

Experiment 2 utilized the dataset marketplace of China’s Credamo platform to recruit 220 participants online. After completing the experiment, participants were compensated with cash. The participants in Experiment 2 were randomly allocated to either of two groups: one presented with a low-credibility NPO and the other with a high-credibility NPO. The manipulation of NPO credibility (Cronbach’s α = 0.97), dependent variable (Cronbach’s α = 0.91), control variables and socio-demographic characteristics were identical to those in Experiment 1. Participants also reported their perception of corporate hypocrisy using six items (Cronbach’s α = 0.94), such as “Do you think Xilin act hypocritically?”, with response options ranging from 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree” [9]. Additionally, we utilized a new product type (i.e., a water purifier) and a fresh charity campaign (i.e., caring for the empty nester) in this experiment.

3.2.2. Analysis and Results

Manipulation checks for NPO credibility: The results of one-way ANOVA were highly significant (Mlow = 2.60, Mhigh = 4.34; F(1, 219) = 249.54, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.53). Therefore, the manipulation of NPO credibility in Experiment 2 was successfully implemented.

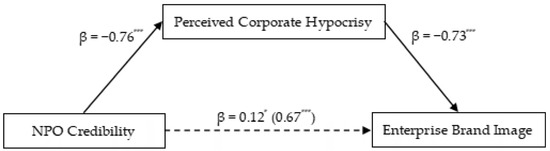

The mediating role of perceived corporate hypocrisy: To investigate the intermediary influence of perceived corporate hypocrisy on the relationship between NPO credibility and enterprise brand image, we employed the recommended indirect bootstrapping technique (Model 4 with 5000 bootstrap samples) [40]. The findings indicate a positive and highly significant mediating effect of perceived corporate hypocrisy (Effect = 0.6962, SE = 0.0980, 95% CI = 0.5093, 0.8867). Furthermore, after incorporating participation experience in relevant charity campaigns and the perceived importance of the donation into the model, the mediating effect of perceived corporate hypocrisy remained significant (Effect = 0.5480, SE = 0.0929, 95% CI = 0.3696, 0.7288). After incorporating the mediating variable (perceived corporate hypocrisy), the impact of NPO credibility on enterprise brand image remained significant (F(1, 219) = 4.29, p = 0.04, η2p = 0.02). The specific path coefficients are shown in Figure 1. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is supported. In other words, when the company partners with a low-credibility NPO compared to a high-credibility NPO, consumers would be likely to experience more corporate hypocrisy, and then perceive a more negative enterprise brand image.

Figure 1.

The mediating effect of perceived corporate hypocrisy on the relationship between NPO credibility and enterprise brand image (results of Experiment 2). Note: *** indicates p < 0.001, * indicates p < 0.05.

3.3. Experiment 3

In Experiment 3, our objective is to explore the moderating influence of public emergency on the relationship between NPO credibility and enterprise brand image (e.g., test H3), as well as examining whether the moderating impact of public emergency is mediated by perceived corporate hypocrisy (e.g., test H4).

3.3.1. Participants, Procedure and Stimuli

In Experiment 3200 undergraduate students from a major university in China participated. However, twelve participants were disqualified due to incomplete or invalid responses. This study employed a 2 (low-credibility NPO vs. high-credibility NPO) × 2 (public emergency: COVID-19 vs. no COVID-19) between-subjects design, with participants randomly assigned to one of the four conditions. The manipulation of NPO credibility (Cronbach’s α = 0.95), the dependent variable (Cronbach’s α = 0.86), the mediating variable (Cronbach’s α = 0.90), control variables, and socio-demographic characteristics were identical to those in Experiment 1 and 2. Additionally, to test whether our manipulation of public emergency was successful, we also measured participants’ perception of public emergency [10].

3.3.2. Analysis and Results

Manipulation checks for NPO credibility and public emergency: We conducted two two-way ANOVAs with NPO credibility, public emergency, and their interaction as the independent variables, and perceived credibility or perceived public emergency as the dependent variable. The results revealed that NPO credibility had a significant main effect on perceived credibility (Mlow = 2.80, Mhigh = 3.80; F(1, 187) = 84.94, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.32), and public emergency had a significant main effect on perceived emergency (Mno COVID-19 = 3.11, MCOVID-19 = 3.77; F(1, 187) = 21.30, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.10). Consequently, the manipulation of NPO credibility or public emergency in Experiment 3 was successfully implemented.

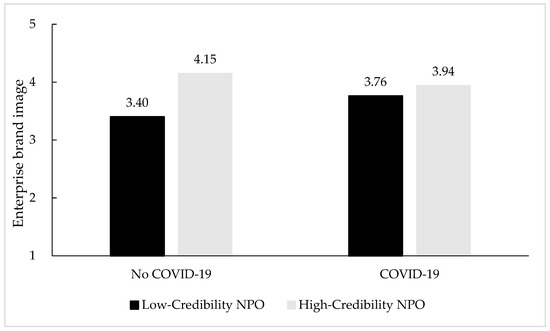

The moderating role of public emergency: We conducted a two-way MANOVA with NPO credibility, public emergency, and their interaction as the independent variables, and enterprise brand image as the dependent variable. The results indicated a significant interactive effect of NPO credibility and public emergency on enterprise brand image (F(1, 187) = 9.64, p = 0.002, η2p = 0.05). Furthermore, after adding participation experience in relevant charity campaigns and the perceived importance of the donation to the model, the moderating effect of public emergency remained significant (F(1, 187) = 10.06, p = 0.002, η2p = 0.05). The results of follow-up contrast analyses revealed that in the no COVID-19 condition, consumers perceive a more negative enterprise brand image when the company partners with a low-credibility NPO compared to a high-credibility NPO (Mlow = 3.40, Mhigh = 4.15; F(1, 87) = 37.78, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.31); whereas in the COVID-19 condition, the impact of NPO credibility on enterprise brand image was in the expected direction but not significant (Mlow = 3.76, Mhigh = 3.94; F(1, 99) = 2.01, p = 0.16, η2p = 0.02) (as shown in Figure 2). Thus, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Figure 2.

The interactive effect of NPO credibility and public emergency on enterprise brand image (results of Experiment 3).

The mediating role of perceived corporate hypocrisy: To examine the mediating effect of perceived corporate hypocrisy on the interactive relationship between NPO credibility and public emergency in shaping enterprise brand image, we utilized the recommended indirect bootstrapping technique (Model 8 with 5000 bootstrap samples) [40]. The outcomes indicated a significant and negative mediation effect of perceived corporate hypocrisy on NPO credibility and public emergency’s impact on enterprise brand image (Effect = −0.1890, SE = 0.0900, 95% CI = −0.3800, −0.0307). Furthermore, after incorporating participation experience in relevant charity campaigns and the perceived importance of donations into the analysis, the mediating role of perceived corporate hypocrisy remained significant (Effect = −0.1857, SE = 0.0801, 95% CI = −0.3561, −0.0361). Thus, Hypothesis 4 is supported. Furthermore, in the no COVID-19 condition, perceived corporate hypocrisy had a positive and significant mediating effect on the relationship between NPO credibility and enterprise brand image (Effect = 0.2218, SE = 0.0696, 95% CI = 0.0951, 0.3673), whereas in the COVID-19 condition, the mediating effect of perceived corporate hypocrisy was in the predicted direction but not significant (Effect = 0.0361, SE = 0.0530, 95% CI = −0.0604, 0.1495).

Table 3 summarizes all the results of our hypothesis tests.

Table 3.

Summary of hypothesis test results.

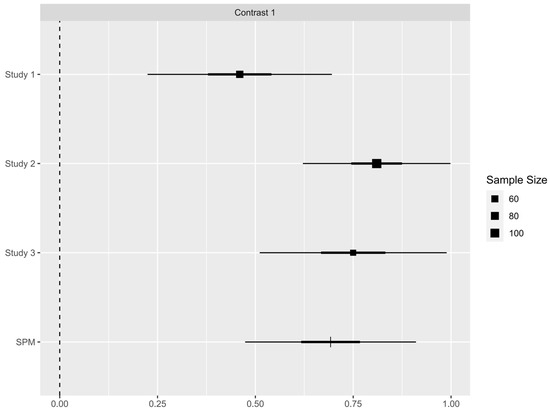

3.4. Single-Paper Meta-Analysis

Through our three experimental studies, we have convincingly demonstrated that consumers perceive a more negative enterprise brand image when a company partners with a low-credibility NPO compared to a high-credibility NPO. To further validate the robustness of our findings and the overall strength of each study, we employed the single-paper meta-analysis method proposed by Mcshane and Böckenholt [41]. The results of this analysis are presented in Figure 3. The prediction value for the low-credibility NPO condition is 3.47 (SE = 0.10), while the prediction value for the high-credibility NPO condition is 4.16 (SE = 0.10). The comparison difference prediction value between the two conditions is 0.69 (SE = 0.11) (95% CI = 0.4739, 0.9104). These findings suggest that the effect of this study is robust and reliable.

Figure 3.

Results of the single-paper meta-analysis.

4. Discussion

This study investigates the impact of NPO credibility on enterprise brand image within CRM campaigns, its mediating mechanism, and its boundary conditions, employing three progressively advancing and mutually corroborative experiments along with a single-paper meta-analysis. The results indicate that collaborating with a low-credibility NPO negatively affects the enterprise brand image. This finding contrasts with existing literature, which primarily focuses on the positive effects of CRM campaigns [42,43]. Our research, however, reveals the potential negative impact of partnering with a low-credibility NPO on the enterprise brand image. Furthermore, this effect is mediated by consumers’ perceptions of corporate hypocrisy. When companies collaborate with low-credibility NPOs, consumers’ perceptions of corporate hypocrisy are heightened, leading to negative evaluations of the brand image. Unlike existing literature, we find that this perception of corporate hypocrisy is not solely dependent on the company’s CSR actions [25], but is influenced by the NPO credibility. Additionally, our study responds to previous calls for considering contextual factors [33,44] by examining the moderating role of public emergencies in the relationship between NPO credibility and enterprise brand image. We find that during public emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the impact of NPO credibility on brand image is significantly weakened. This is because, in times of crisis, consumers are more likely to attribute collaborations with low-credibility NPOs to situational constraints rather than opportunism, making them more tolerant [12].

4.1. Theoretical Implications

This study offers several theoretical contributions to the literature. Initially, it delves into the efficacy of CRM campaigns and the factors that shape its impact from the perspective of NPOs. Previous research on CRM effectiveness has been extensively explored from the perspectives of consumer-related traits, execution-related factors, and product-related traits [7]. However, there has been little attention paid to how the characteristics of NPOs collaborating with companies influence the effectiveness of CRM. This study examines the influence mechanism of NPO credibility on corporate brand image through the lens of the affect-transfer model. The findings of this study not only enhance the theoretical framework examining the CRM effectiveness research, enriching the research perspective, but also expand the applicable scenarios of the affect-transfer model, highlighting its application value in the domain of customer relationship management and laying the foundation for future academic research on the affect-transfer model.

Secondly, based on attribution theory, this study reveals the negative mechanisms through which NPO credibility influences corporate brand image. Previous CRM research has primarily focused on its positive effects, demonstrating that CRM significantly enhances emotional connections between companies and consumers, thereby boosting brand loyalty and consumer purchase intentions [42,43]. However, limited attention has been given to its potential negative impacts and underlying mechanisms. This study, from the perspective of corporate hypocrisy perceptions, explores the psychological mechanisms through which NPO credibility affects corporate brand image, confirming that when companies collaborate with highly reputable NPOs, consumers tend to attribute more positive qualities, resulting in a more favorable corporate brand image. Conversely, when partnering with less reputable NPOs, negative attributions lead consumers to perceive corporate hypocrisy, which negatively affects the corporate brand image. This research not only underscores the theoretical value of attribution theory in CRM studies, extending the scope of attribution theory, but also provides a solid theoretical foundation for future research on the double-edged sword effect of CRM.

Finally, this study confirms that public emergency serves as a critical boundary condition in determining the impact of NPO credibility on corporate brand image. The public emergency posed by the novel coronavirus pneumonia has had a profoundly negative impact on society. However, prior research has paid less attention to how the impact of corporate CRM activities on corporate brand image may change during public emergencies [2,7]. Our findings indicate that during public emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, consumers’ perception of corporate hypocrisy in CRM campaigns is mitigated. Additionally, the negative impact on a company’s brand image resulting from collaborating with a low-reputation NPO is reversed. This study not only identifies a common and effective boundary condition for CRM, enriching the theoretical framework of CRM research, but also provides a theoretical reference for future studies examining the contextual effects of public emergencies in related fields.

4.2. Practical Implications

This study provides several important managerial implications for companies engaging in CRM activities. First, companies should exercise caution when selecting NPOs to collaborate with, particularly regarding the credibility of the NPO. The findings of this study indicate that partnering with low-credibility NPOs may harm a company’s brand image, especially in the context of declining public trust in NPOs due to scandals or corruption cases. For instance, recent corruption scandals have tarnished the reputations of certain charitable organizations, and when companies collaborate with these organizations, consumers may perceive their actions as hypocritical or merely a publicity stunt. Therefore, companies should prioritize selecting NPO partners with high social recognition, professionalism, and promising future prospects. By doing so, companies can not only avoid negative consumer perceptions of their philanthropic efforts but also enhance the public’s positive perception of their brand.

Second, companies must carefully select the timing of their CRM initiatives. While there may be situations where companies must collaborate with lower-credibility NPOs, strategically choosing the appropriate timing can mitigate the negative impact of partnering with such organizations. For example, the study finds that during public emergencies (such as the COVID-19 pandemic), the negative impact of low-credibility NPOs on a company’s brand image is reduced. During such times, consumers are more tolerant of companies’ charitable actions, which in turn enhances the company’s image of social responsibility. Based on these findings, companies should seize the opportunity during public crises and proactively engage in relevant charitable activities to enhance brand visibility and promote a sense of corporate social responsibility.

4.3. Limitation and Future Research

The current study has several limitations that provide directions for future research. First, the experiments relied primarily on textual descriptions to convey CRM campaign content. However, in the “Internet +” era, online CRM campaigns increasingly present consumers with multiple information formats, including texts, images, and videos, offering a richer understanding of the campaigns [29,45]. Future research should aim to bridge this gap and more closely replicate online CRM environments. Second, this study predominantly draws on empirical research centered around CRM activities and participants in China, overlooking the potential influence of cultural factors on the outcomes. Considering that consumer perceptions of corporate hypocrisy and trust in NPOs may differ substantially across diverse cultural settings, this oversight could constrain the generalizability of our findings. Future research should incorporate cross-cultural analyses to further substantiate and broaden the scope of our findings, thereby strengthening the universal applicability of its conclusions. Third, this study focused on CRM campaigns during the COVID-19 pandemic and on specific types of NPOs, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should examine whether the effects of NPO credibility on corporate brand image hold in other public emergency contexts and across different types of NPOs to enhance external validity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W., L.Z., X.L. and C.G.; methodology, L.Z. and X.L.; software, L.Z. and X.L.; validation, J.W.; formal analysis, L.Z. and X.L.; investigation, L.Z. and X.L.; resources, L.Z.; data curation, L.Z. and X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Z. and X.L.; writing—review and editing, J.W. and L.Z.; visualization, J.W., L.Z., X.L. and C.G.; supervision, J.W.; project administration, J.W.; funding acquisition, J.W. and L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Scientific Research Project of Tianjin Municipal Education Commission [grant number 2022SK194].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of School of Management, Guizhou University (protocol code GDGY20210915001, 16 September 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Deng, N.; Jiang, X.; Fan, X. How social media’s cause-related marketing activity enhances consumer citizenship behavior: The mediating role of community identification. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schamp, C.; Heitmann, M.; Bijmolt, T.H.A.; Katzenstein, R. The effectiveness of cause-related marketing: A meta-analysis on consumer responses. J. Mark. Res. 2023, 60, 189–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labyrinth Inc. The Ultimate Guide to Cause Marketing: How Brands Are Driving $2B+ in Social Impact (2025 Playbook). 2025. Available online: https://labyrinthinc.com/cause-marketing-2b-social-impact-guide-2025/ (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Alibaba. Environmental, Social and Governance Report 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.alibabagroup.com/esg (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Wang, M.; Wang, Y. Trust crisis and charity donation: An empirical study based on the provincial data in 2002–2016. Manag. Rev. 2020, 32, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plant Based News. American Heart Association Facing Lawsuit Over ‘Heart-Check’ Labels on Red Meat. 2022. Available online: https://plantbasednews.org/lifestyle/health/american-heart-association-lawsuit-heart-check-labels-meat/ (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Fan, X.; Deng, N.; Qian, Y.; Dong, X. Factors affecting the effectiveness of cause-related marketing: A meta-analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 175, 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyravene, R.; Rabbanee, F.K. Corporate negative publicity–the role of cause related marketing. Australas. Mark. J. 2016, 24, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate hypocrisy: Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, N. The negative consumer perception of brand charity geographical inconsistency and its reversal mechanism. J. Manag. World 2016, 1, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davvetas, V.; Ulqinaku, A.; Abi, G.S. Local impact of global crises, institutional trust, and consumer well-being: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Int. Mark. 2022, 30, 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T. Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2007, 10, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Hernández, S.N.; Terán-Bustamante, A.; Martínez-Velasco, A. COVID-19, social identity, and socially responsible food consumption between generations. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1080097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elcheroth, G.; Drury, J. Collective resilience in times of crisis: Lessons from the literature for socially effective responses to the pandemic. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 59, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Ma, M. The mechanism of the parent brand effect in brand extension. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 11, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, I.P.; Levin, A.M. Modeling the role of brand alliances in the assimilation of product evaluations. J. Consum. Psychol. 2000, 9, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.R.; Ruekert, R.W. Brand alliances as signals of product quality. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wang, Y. Damage to the reputation of government-owned charitable organizations, reputation punishment and donation of private enterprises. Manag. Rev. 2023, 35, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, J.; Abu Bakar, H. Revisiting organizational credibility and organizational Reputation—A situational crisis communication approach. SHS Web Conf. 2017, 33, 00083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloderer, M.P.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. The relevance of reputation in the nonprofit sector: The moderating effect of socio-demographic characteristics. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2014, 19, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Ko, W.W. An analysis of cause-related marketing implementation strategies through social alliance: Partnership conditions and strategic objectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 253–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, D.R.; Drumwright, M.E.; Braig, B.M. The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported nonprofits. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, H.; Yang, S.U.; Lee, J. Strategic partnerships with nonprofits in corporate social responsibility (CSR): The mediating role of perceived altruism and organizational identification. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3213–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A.; Lueth, A.K.; Mccafferty, R. An evolutionary process model of cause-related marketing and systematic review of the empirical literature. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 951–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, S.; Ha-Brookshire, J.; Bonifay, W. Measuring perceived corporate hypocrisy: Scale development in the context of U.S. retail employees. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, F.; Xie, Z.; Huang, W. Charity or hypocrisy: Public perception and evaluation of CSR activities of companies with undesirable reputation. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2014, 10, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychol. Rev. 1985, 92, 548–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Tian, Z. A study on the formation mechanism of consumers’ perception of CSR hypocrisy. J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law 2017, 2, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Innovation of emergency system model and collaborative path of artificial intelligence in modern governance of global public emergency risk under the background of COVID-19 prevention and control. China Soft Sci. 2021, 7, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Trent, E.S.; Sullivan, P.M.; Matiru, G.N. Cause-related marketing: How generation Y responds. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2003, 31, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Du, L.; Li, J. Cause’s attributes influencing consumer’s purchasing intention: Empirical evidence from China. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2008, 20, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, C.D.; Kim, J. The effects of CSR communication in corporate crises: Examining the role of dispositional and situational CSR skepticism in context. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, R. The mediating role of moral elevation in cause-related marketing: A moral psychological perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Kim, H.E.; Youn, N. Together or alone on the prosocial path amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: The partitioning effect in experiential consumption. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Huang, E.; Song, W.; Zhao, T. The effects of public health emergencies on altruistic behaviors: Empirical research on the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Res. Sq. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A. The relevance of fit in a cause-brand alliance when consumers evaluate corporate credibility. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferle, C.L.; Kuber, G.; Edwards, S.M. Factors impacting responses to cause-related marketing in India and the United States: Novelty, altruistic motives, and company origin. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhamme, J.; Lindgreen, A.; Reast, J.; van Popering, N. To do well by doing good: Improving corporate image through cause-related marketing. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcshane, B.B.; Böckenholt, U. Single-paper meta-analysis: Benefits for study summary, theory testing, and replicability. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 43, 1048–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partouche, J.; Vessal, S.; Khelladi, I.; Castellano, S.; Sakka, G. Effects of cause-related marketing campaigns on consumer purchase behavior among French millennials: A regulatory focus approach. Int. Mark. Rev. 2020, 37, 923–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brink, D.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Pauwels, P. The effect of strategic and tactical cause-related marketing on consumers’ brand loyalty. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlinova, A.; Kukacka, J. Corporate social responsibility and stock prices after the financial crisis: The role of strategic CSR activities. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 182, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Guo, Y.; Lv, L.; Wu, Y. Literature review and prospects of virtual CSR co-creation. Soft Sci. 2021, 35, 112–116+130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).