Abstract

Wound healing requires careful, directed, and effective therapies to prevent infections and accelerate tissue regeneration. In light of these demands, active biomolecules with antibacterial properties and/or healing capacities have been functionalized onto nanostructured polymeric dressings and their synergistic effect examined. In this work, various antibiotics, nanoparticles, and natural extract-derived products that were used in association with electrospun nanocomposites containing cellulose, cellulose acetate and different types of nanocellulose (cellulose nanocrystals, cellulose nanofibrils, and bacterial cellulose) have been reviewed. Renewable, natural-origin compounds are gaining more relevance each day as potential alternatives to synthetic materials, since the former undesirable footprints in biomedicine, the environment, and the ecosystems are reaching concerning levels. Therefore, cellulose and its derivatives have been the object of numerous biomedical studies, in which their biocompatibility, biodegradability, and, most importantly, sustainability and abundance, have been determinant. A complete overview of the recently produced cellulose-containing nanofibrous meshes for wound healing applications was provided. Moreover, the current challenges that are faced by cellulose acetate- and nanocellulose-containing wound dressing formulations, processed by electrospinning, were also enumerated.

1. Introduction

Skin is the largest and outermost organ that covers the entire body, forming 8% of the body weight [1]. It is responsible for the body physical protection and sensitivity, serves as barrier to microbial and UV radiation, and regulates biochemical, metabolic, and immune functions, such as temperature, water loss (preventing dehydration) and synthesis of vitamin D3 [2,3].

When the skin barrier is disrupted through wounds, a series of complex physiochemical processes take place in an attempt to repair and regenerate the damaged tissue [4]. Wound healing is based on a complex series of cellular and biochemical processes, starting with inflammatory reactions (immune response to prevent infection), followed by proliferation (regeneration of tissues), and finalizing with tissue remodeling [5]. Based on the time that is required for wound healing, two types of wounds can be established: acute and chronic. Acute wounds usually heal within eight to 12 weeks after injury, while chronic wounds that include diabetic, pressure, and venous stasis ulcers, are unable to follow the normal healing steps, taking more than three months to heal. This inability to heal in a predictable amount of time occurs due to local (e.g., trauma, infections, radiation) and systemic factors (e.g., genetic disorders, diabetes, old age, smoking habit, vitamin deficiencies). However, in most cases, the presence of bacteria and the development of infections are the main causes [2,6,7,8,9]. Wounds are often colonized by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Escherichia coli (E. coli), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) bacteria, and approximately 60% of chronic wounds display biofilms hindering their treatment. Biofilms are complex structures, which are formed of multiple groups of bacteria, often with different genotypes, which are further held together by extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). Their presence induces an immune response from the host. Local bacterial infections not only increase patient discomfort and delay wound healing, but they may also lead to more severe systemic infections. These microorganisms are responsible for high mortality rates in developing countries and have become an increasing cause of death in severely ill hospitalized patients, turning into an important economic burden in the health care system [10].

The first modern wound dressing was produced in the mid-1980s and it was characterized by its ability to maintain a moist environment and absorb fluids, and by playing a vital role in minimizing infection and promoting wound healing/management [11]. Modern dressings have evolved since then, being now recognized as interactive and bioactive solutions that combine the physical protection of traditional dressings with the ability of specialized bioactive molecules to stimulate cell regeneration through the proliferation and migration of fibroblasts and keratinocytes, to increase collagen synthesis, fight bacterial infections, and contribute with drug delivery functions for an efficient healing process. An optimal dressing is thus defined as capable of maintaining high humidity at the wounded site while also removing excess exudates, is non-toxic or allergenic, allows for oxygen exchange, can protect against microorganism invasion, and it is comfortable and cost effective. Modern dressings are designed as vehicles to deliver therapeutic agents at the wounded site, while assuming the most varied forms, including hydrogels, films, sponges, foams, and, more recently, nanofibrous mats [12,13,14,15].

Nanofiber-based dressings have attracted much attention in the fields of biomedicine, tissue engineering, and controlled drug delivery because of their intricate architecture. Dressings assembled while using nanofibers, produced via electrospinning, have shown clear advantages over conventional wound dressings. They resemble the morphological structure of the extracellular matrix (ECM) due to their nanoscale features, easily incorporating biomolecules or nanoparticles of interest, high porosity and large surface area [16,17]. In addition, these electrospun wound dressings have also shown good hemostasis, absorbability, and oxygen permeability, which are determinant factors for a fast and successful wound healing [18]. Various natural and synthetic polymers have been used in the production of polymeric nanofibrous mats via electrospinning, for prospective wound healing applications [19]. However, nowadays, there is a great demand for materials that are more sustainable, environmentally friendly, and capable of being processed at the nanoscale. When considering this, biomass-based polymers, such as cellulose and its derivatives, have become the hotspot of science due to their intrinsic properties. Cellulose, being one of the most abundant natural polymers on Earth, with relatively easy extraction, superior biocompatibility, non-toxicity, and biodegradability, has been considered as a factual option for wound dressings formulations, either as an additive or as base substrate. Acquired data has been very promising, with excellent effects being registered in regard to cell adhesion and growth [20,21]. However, the production of natural cellulose-based nanofibers, regenerated cellulose nanofibers, and even microfibers via electrospinning remains a very challenging process, due to their inability to dissolve in water and common organic solvents. In fact, most of the cellulose-containing nanofibers have been produced after extensive tests with a variety of solvents or by combining cellulose with other materials, e.g., polymers, metals or ceramics, and loading those formulations with bioactive molecules, such as drugs and growth factors [20,22]. The introduction of chemical groups within the structure of cellulose has facilitated processing and contributed for the emergence of cellulose derivatives, like cellulose acetate (CA), which is the most common derivative that is considered by the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) as a bio-based polymer [23]. CA is a polymer that is easily soluble in common organic solvents, such as acetone, acetic acid, N,N-dimethylacetamide, and their mixtures, low-cost derivative of cellulose with excellent biocompatibility, high water adsorption capacities, good mechanical stability, non-toxicity, and can be efficiently processed into membranes, films, and fibers from either solutions or melts [21,24,25,26,27,28]. Electrospinning allows for the production of CA-based nanomeshes with an intricate and complex architecture that can be functionalized with active biomolecules to address the specific demands of acute and chronic wounds via simple, reproducible and cost effective approaches [29,30,31]. The nanocellulose is another cellulose based material that has gathered much interest in the last few decades, for prospective biomedical field. Its biocompatibility, nontoxicity, biodegradability, water absorption capacity, optical transparency, and good mechanical properties have attracted researchers from all fields. Indeed, its incorporation in electrospun nanocomposites has contributed significantly for the overall composite increased mechanical properties, namely Young’s modulus and elongation at break [32,33,34].

When considering antimicrobial resistance one of the increasingly serious threats to human and animal health worldwide, there is an urgent need for more effective and target-directed therapies [35,36]. The present work provides an overview of the most recent dressing formulations containing natural-origin celluloses for chronic wound care. Their extraction, treatment, and further compatibility with other polymers were examined and their implications and potential to overcome these microbial threats was analyzed. The challenges in processing cellulose, cellulose acetate, and nanocellulose nancomposites via electrospinning were also highlighted.

2. Nanostructured Wound Dressings

Traditional dressings, which are also known as passive dressings (simple gauze or gauze-cotton composite dressings, available since the mid-1970s), have as main function the protection of the wounded bed from further harm or to serve as barrier against the external environment; not however treating the wound or preventing bacteria from colonizing the site [37,38,39]. In an attempt to prevent these threats, modifications to the dressings’ structure have been proposed, resorting to either the grafting of non-adhesive particles at the inner surface or by using antimicrobial polymers, inorganic nanoparticles, or biomolecules [40]. These modified dressings are known as interactive or bioactive. Interactive/bioactive dressings can be defined as dressings with the capacity to alter the wound environment, optimizing the healing process. This group includes films, foams, hydrocolloids, alginates, hydrogels, and collagen-, hyaluronic acid-, and chitosan-based dressings, which stimulate the healing cascade [41,42]. Modern dressings, beyond protecting the affected area, should generate an environment conducive to healing, by:

- ▪

- guaranteeing breathability;

- ▪

- maintaining a suitable physiological temperature;

- ▪

- ensuring a balanced moist environment, avoiding dehydration and cell death;

- ▪

- promoting debridement;

- ▪

- allowing proliferation and migration of fibroblasts and keratinocytes, and an enhanced collagen synthesis;

- ▪

- protecting the wound from bacteria and other external soiling; and,

- ▪

- adapting to the wound shape, without adhering [43,44,45].

Prior to the selection of the ideal dressing, health professionals should consider a number of parameters. Firstly, if there is necrotic tissue, debridement is required. Dead and decayed tissue in the wound area are critical, as they impede the healing process by stimulating bacteria proliferation, prolonging inflammation, and preventing reepithelization. Still, the healing process may be rekindled if conveniently cleaned. There are dressings that can facilitate autolytic debridement; the retention of moisture at the wound bed can help to soften and liquefy the accumulated dead cells and fibrinous deposits. Therefore, the selection of an ideal dressing is determined by the presence of necrotic tissue and biofilms as well as the type of tissue and its coloration, healing time, frequency of dressing changes, nursing costs, and need of secondary dressings, antibiotics, or analgesics [7,41,46,47].

The most widely used dressings in chronic wounds are the interactive/bioactive dressings, such as films, foams, hydrogels, hydrocolloids, and alginates (Figure 1) [48,49]. The films are flexible semipermeable dressings, impermeable to fluids and bacteria, and permeable to air and water vapor [50]. Hydrogels stand out by their insoluble, highly absorbent three-dimensional (3D) polymeric network, capable of maintaining a moist microenvironment at the wound bed. Hydrogels can be formulated as particles, sponges, films, and other 3D structures, and their porosity can be controlled by embedding particles of various sizes. These are particularly effective in wounds with minimal to moderate exudates [51,52,53,54]. Hydrocolloids typically consist in carboxymethylcellulose, pectin, or gelatin. In their intact state, hydrocolloids are impermeable to water vapors, but as the gelling process takes place the dressing becomes progressively more permeable. The loss of water enhances the ability of the dressing to cope with the exudates production and lower the pH, this way hindering the bacterial growth and contributing to an optimal, stable temperature, and moisture level that stimulates all phases of healing [46]. Alginates are usually classified as bioactive dressings, being available in the form of non-woven sheets and ropes or as calcium-enriched fibrous structures that are capable of absorbing fluid up to 20 times their weight [55,56]. Upon contact with the wound, calcium is exchanged with the sodium from the exudates turning the dressing into a gel. Because of this exchange, alginates act as a hemostat and are, therefore, useful in managing bleeding wounds. They also activate human macrophages to produce tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), which initiates the inflammatory signals. However, these dressings might not be the most suitable to fight infections, as they generate an environment that is conducive to bacteria proliferation [50,55,56].

Figure 1.

Structure of different wound dressings (adapted from [11], with permission from Elsevier, 2020).

As seen in the alginates, bioactive dressings can directly deliver active compounds to the wound. They may also be composed of materials with endogenous activity which play an active role in the healing process, by activating or driving cellular responses [57,58]. Various antibiotics, vitamins, proteins, minerals, enzymes, insulin, growth factors, cells, and antimicrobial agents have been used in this class of dressings to accelerate healing [26,29,59].

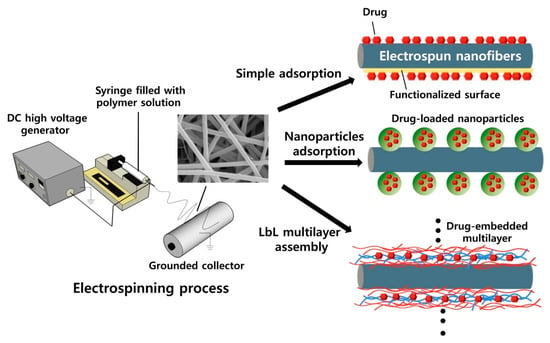

The production of nanofibrous dressings reinforced with active biomolecules has been accomplished through various techniques, including electrospinning, melt-blowing, phase separation, self-assembly, and template synthesis [45,60]. The electrospinning technique is perhaps the most researched as it allows the production of porous, randomly-orientated structures that mimic the 3D architecture of collagen fibers that are found within the ECM of normal skin [61]. This technique might be used to produce dressings belonging to each of the former categories (films, hydrogels, hydrocolloids or alginates) in its entirety or partially. Through simple blend with the polymer solution, while using one nozzle or multiaxial nozzles (coaxial or triaxial nozzle), core/shell, smooth and continuous structures may be engineered to increase the efficiency of the incorporated biomolecules and control their release kinetics. The incorporation of biomolecules within the polymeric solutions affects their viscosity and conductivity, which play a major role in their electrospinnability and in the resultant nanofiber morphologies. Alternatively, surface functionalization post-electrospinning, via chemical or physical methods, has been proposed. Electrospun nanofibers that are incorporated or functionalized with antimicrobial agents have shown enhanced antibacterial performance compared to traditional dressings. Depending on the application, the addition of specialized biomolecules to these nanofibrous networks may serve as platforms to increase oxygen exchange and absorption of exudates, and/or to stimulate proliferation, migration, and differentiation of cells, while promoting nutrient supply and controlling fluid loss [22,62,63,64,65].

Cellulose being a natural polymer has attracted lots of attention for biomedical applications, due to its inherent features, such as biodegradability, low price, abundance, renewability, high mechanical strength, and lightness. Considerable research has been undertaken on the use of cellulose, cellulose derivatives and nanocellulose for the production of electrospun 3D nanocomposites [66]. The most widely researched and employed cellulose derivative is CA, the acetate ester of cellulose. CA electrospun fibers have shown excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability, good thermal stability and chemical resistance [67]. For biomedical applications, the surface and structure modifications of CA-containing nanocomposites are commonly done. For instance, to generate a CA nanofiber mat with a honeycomb-like structure, F. Hamano et al. combined the electrospinning technique with a very simple oil spray method [68]. K.I. Lukanina et al., on its turn, generated a sponge-nonwoven CA matrix by filling the electrospun mat with chitosan and collagen and posteriorly freezing and vacuum drying the combination [69]. The natural, microbial, and biodegradable thermoplastic polymer poly(hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) was blended with CA and the processed by electrospinning to generate fibrous nanocomposites with a considerable capacity to induce cell adhesion and proliferation. At a higher CA content, it was seen that amorphous regions were more common and that the loss of fiber integrity occurred more quickly [70].

Recently, nanocelluloses have gained more interest in the biomedical field, due to their unique properties of low cost, biodegradability, biocompatibility, low cytotoxicity, outstanding mechanical properties, availability, and sustainability [71]. The great amount of -OH groups on the surface of these nanomaterials favors the formation of hydrogen bonds, playing an important role in promoting the adhesion between nanocellulose and other polymeric materials within the nanocomposites, aside from enhancing their water retention capacity [72]. Among the many types of nanocellulose available, bacterial cellulose (BC) has already been successfully applied, starting its commercialization in wound dressings in 1980 by Johnson & Johnson (New Brunswick, USA). A Brazilian company, BioFill Produtos Biotecnologicos, already created a new wound healing system that was based on BC, and Lohmann & Rauscher, a German company, has commercialize the Suprasorb X®. Bioprocess® and XCell® are other wound dressings that are also in the market. BC is capable of maintaining a moist environment at the wound bed and to absorb exudates during the acute inflammatory phase [73].

Many studies have been conducted to engineer bioactive dressings capable of facing the rising of microbial resistance pathogens without compromising the healing process. In the following sections, a complete review and discussion of the most successful alternatives, containing cellulose and its derivatives, to the conventionally used dressings was provided. Special attention will be given to clean strategies and to the issues still faced in this line of research, as the environment conservation remains a challenge and a major focus of this work.

3. Cellulose and Its Derivatives

3.1. Cellulose

Cellulose is the most abundant organic, eco-friendly polymer on Earth. It is a polysaccharide that consists of D-glucopyranose units (commonly composed by 10,000–15,000 units, depending on the source) that are linked by a covalent β-1,4-glycosidic bond through acetal functions, between -OH groups of C4 and C1 carbon atoms, that forms a linear and high molecular weight homopolymer [74,75]. For each anhydroglucose unit, the reactivity of the -OH groups on different positions is heterogeneous. The -OH at the 6th position acts as a primary alcohol, whereas the -OH in the second and third positions behave as secondary alcohols. It has been reported that, on the structure of cellulose, the -OH group at the sixth position can react ten times faster than other -OH groups, while the reactivity of the -OH on the second position was found twice as high of that of the third position [71]. The many -OH groups that are present in the cellulose backbone establish numerous intra- and intermolecular bonds that result in its semicrystalline structure. However, this molecular structure may undergo modifications, depending on the source of the material, method of extraction, and treatment, giving rise to different polymorphs. There are four types of polymorphs of crystalline cellulose (I, II, III, IV). Cellulose I, which is also known as “natural” cellulose, is sourced in its vast majority from plants, tunicates, algae and bacteria, being a structural component in cell walls. Because its structure is thermodynamically metastable, cellulose I can be converted into cellulose II or III. Cellulose II is the most stable structure and it can be produced either by regeneration (solubilization and recrystallization) or by mercerization (aqueous sodium hydroxide treatments). This type of cellulose has a monoclinic structure and it has been used in the production of cellophane, Rayon, and Tencel. Cellulose III results from subjecting cellulose I and II to alkaline treatments, while cellulose IV originates from the thermal treatment of cellulose III [76,77]. Another important parameter that is influenced by the source and processing of cellulose is the degree of polymerization (DP), which is the number of monomer units in the polymer backbone and affects the material viscosity and mechanical properties. For instance, while cellulose from wood pulp has only 300–1,700 units, BC has a DP of 800–10,000 repeat units [78].

The primary natural source of cellulose is the lignocellulosic material that is present in wood (40–50 wt.%). It can also be extracted from vegetable fibers like cotton (87–90 wt.%), jute (60–65 wt.%), flax (70–80 wt.%), ramie (70–75 wt.%), sisal, and hemp. However, most of these sources require large arable spaces and considerable amounts of fresh water, fertilizers, and pesticides. Additionally, cellulose can also be produced from bacteria, algae, fungi, and some animals (e.g., tunicate) [74]. To reduce the environment impact associated with its production, strategies are being developed to effectively reuse wood pulp and agricultural and food wastes, or even take advantage of wastes from the textile industry (e.g., used garments) to recover cellulose and produce new fibers with similar properties to those regenerated from conventional wood pulp [74,78,79]. Table 1 introduces some of the alternative sources of cellulose and their inherent pretreatments to obtain an efficient extraction and new unconventional solvents systems that are applied in their solubilization. For instance, the solvent N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide (NMMO), which is used in Lyocell production (rayon fiber obtained from wood pulp), has been successful in dissolving cellulose, however it entails high costs and high temperatures; the NaOH/thiourea solvent system has been used in green processes for the production of regenerated cellulose textile fibers, yet it also entails limitations, namely the inability to effectively dissolve high degree polymerized cellulose or high concentrated cellulose solutions. The ionic liquids (IL) are another alternative that has attracted lots of attention for their effectiveness. However, even though they are compatible with cellulose, their elevated cost, toxicity and incapacity to be reused has hindered large-scale, multi-filament productions [80].

Table 1.

Extraction of cellulose from different sources.

Cellulose has attracted considerable interest in the last years because of its potential for generating several high-value products with low impact on the environment and low cost [81]. Among its important characteristics for large-scale production, the cellulose intrinsic mechanical, chemical, and biological properties make this polymer extremely suitable for applications in composite engineering, food science, filtration processes, paper engineering, and medical engineering [82]. The clinical application of cellulose-containing 3D scaffolds includes repair, reconstruction, and regeneration of almost all types of tissues in the mammalian organism; this polymer endows scaffolds with the ability to support cell adhesion and growth. In wound dressings, it is no accident that these cellulose-based materials have been used since the mid-1970s, in the form of cotton gauze or non-woven mixtures of rayon and polyester or cotton fibers, since they are capable of absorbing excess exudates through their bulk polar groups (-OH) and allow for the production of highly porous structures, permeable to air, steam, and heat, ensuring the patients comfort [83].

Nowadays, with the rise of nanotechnology approaches, cellulose nanofibers have been engineered by electrospinning in the form of nanocomposite wound dressings that not only protect the wounds, but they are capable of releasing drugs that inhibit post-operative adhesions, stimulate hemodialysis and hemostasis, and repair tissue defects [20]. Cellulose electrospun nanofibers have been studied due to their ultrafine and highly porous structure, biocompatibility, biodegradability, hydrophilicity, low density, thermostability, low thermal expansion, and easy chemical modification [20,84]. Even though research continues in this field, the disappointing mechanical properties and the difficulties in processing cellulose in the form of nanofibers via electrospinning remain very important challenges. Its strong inter- and intra-molecular interactions originated from hydrogen bonding, and its rigid backbone structure is responsible for its insolubility in most conventional solvent systems and its inability to melt [85]. Several strategies have been proposed to address these limitations. For instance, cellulose nanofibers have been obtained via direct electrospinning by using NMMO (one of the most popular cellulose solvents), lithium chloride/dimethylacetamide (LiCl/DMAc), or ionic solvents,nsuch as 1-ethyl-3 methylimidazolium acetate 1-ethyl-3 methylimidazolium acetate (EmimAc) [86]; however, these processes are cumbersome and very expensive. This has limited the use of cellulose in nanofibrous constructs for wound healing and has increased the use of cellulose derivatives, particularly CA [87].

3.2. Cellulose Acetate (CA)

Many cellulose derivatives have arisen in order to overcome the limited solubility of cellulose in general organic solvents [28]. CA is one of the most important cellulose derivatives, with applications in textile, plastics, cigarette filters, diapers, sensors, LCD screens, catalysts, coatings, semi-permeable membranes for separation processes, nano and macro composites, and fibers and films for biomedical devices [97,98]. This polymer is under great consideration in the biomedical industry due to its biodegradability, biocompatibility, mechanical performance, non-toxicity, high affinity, good hydrolytic stability, relative low cost, and excellent chemical resistance [99]. These exceptional properties have driven the processing of CA-containing polymeric blends in the form of electrospun nanofibrous composites, in this way generating a new smart option for biotechnology and tissue engineering, drug delivery systems and wound dressing applications [25,26,27]. Electrospun CA has also been used to immobilize bioactive substances as vitamins and enzymes, biosensors, bio-separation, and affinity purification membranes, while non-porous CA have been used for stent coatings or skin protection after burns or wounds. Interestingly, CA has also been proven as an effective material for tissue scaffold engineering, providing good mechanical stability, and ability to mimic the extracellular matrix for cell attachment, growth, and advanced formation of targeted tissues (e.g., bones and skin) [100]. Chainoglou et al. has even demonstrated the possibilities of CA for heart valve tissue engineering, through a successful promotion of cardiac cell growth and proliferation [101]. Each one of these applications is dependent on their overall properties, which, in turn, are dependent on the polymer chemical characteristics, such as molar mass, molar mass distribution, DP, and degree of substitution (DS) [102].

DS can be easily understood as the average number of acetyl groups replacing hydroxyl groups per glucose unit. The maximum degree of acetylation is obtained when all of the -OH groups are replaced by acetyl groups, which leads to a DS that is equal to three [103]. DS is a parameter that demands a detailed understanding as it affects the chemical, physical, mechanical and morphological properties of the polymer, altering its polarity, aggregation behavior, biodegradability, and solubility [103,104].

The acetylation process reduces CA crystallinity and insolubility in water [100]. Industrially, CA is produced by the reaction of cellulose with an excess of acetic anhydride in the presence of sulfuric acid or perchloric acid as catalysts, in a two-step process of acetylation, followed by hydrolysis [105,106]. These steps are taken due to the heterogeneous nature of the reaction, since the structure of cellulose is made up of amorphous parts, which react first, and crystalline parts, which then react second; hence, being impossible to synthesize directly partially substituted CAs. An extra hydroxylation step is required for producing CA with the desired DS [21]. CA production entails very high-quality cellulose as raw material, with a high alpha cellulose content [21,105,106,107,108,109,110]. This high-quality cellulose is generally obtained from cotton or wood dissolving pulp, where the cellulose rate is generally more than 95%. However, this is considered to be an expensive material. Alternative sources of cellulose have been researched, finding lignocellulosic biomass as an attractive alternative due to its renewability and large availability worldwide. Preliminary work has uncovered some important sources of CA that are based on biomass that include microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), cotton linter pulp, wheat straw pulp, bamboo pulp, bleached softwood sulfite dissolving pulp, bleached hardwood kraft pulp (HP) [21], oil palm empty fruit bunches [105], sugarcane straw [106], waste cotton fabrics [107], sugarcane bagasse [108], sorghum straw [109], babassu coconut shells [110] and waste polyester/cotton blended fabrics (WBFs) [111]. Still, there is a long way until process optimization occurs, since there are major barriers to the production of cellulose-containing products from agricultural residues, including the heterogeneity of the raw material, the processing conditions reproducibility, the heterogeneous phase of the synthesis reaction, the difficulty of purification, the effluent disposal, and the control of product quality [112].

Many researchers apply alkali or acid pretreatment to remove lignin and hemicellulose of material resources to increase the yield of CA production from wastes, affecting the cellulose crystalline structure, which then becomes more amorphous [110,112,113]. For instance, L. Cao et al. used diluted phosphoric acid at different temperatures and B. Ass et al. used NaOH to disrupt the crystalline structure of cellulose, which increases the amorphous region and renders cellulose more accessible to acetic anhydride, resulting in an acetylation process more effective for CA production [113,114]. Additionally, H.R. Amaral et al. resorted to acid pretreatment of babassu coconut shells to increase the yield of the acetylation of cellulose to obtain CA [110]. These works have shown the importance of pretreating lignocellulosic biomass to increase CA synthesis yield. However, bio-residues from these treatments are a serious environmental challenge due to their aggregation with household wastes, causing disturbances in the ecological cycle of the soil, and resulting in soil infertility and environmental pollution; thus, attention should be urgently paid [110,113,115]. A great opportunity has arisen to explore more of these bio-based polymers and their alternative production methods, given the current environmental and energy policies. Table 2 offers a general overview of this topic, covering some of the most effective alternative solutions for CA processing.

Table 2.

Production of CA from different sources.

3.3. Nanocellulose

The increased demand for high-performance materials with tailored mechanical and physical properties has elevated the nanocellulose status to one of the most attractive renewable materials for advanced medical applications. Nanocellulose is a considered to be a new generation of nanomaterials that combines important cellulose properties, including high specific strength, hydrophilicity, low density, flexibility and chemical inertness, with the ability to be chemically modified to incorporate specific features at the nanoscale [120,121]. In biomedicine, its exceptional water-retention capacity and large surface area that are associated with enhanced cell attachment, proliferation, and migration with no reports of toxic responses, has increased its desirability for a variety of uses that include packages, membranes for hemodialysis, vascular grafts, drug delivery systems, wound dressings, and tissue engineering strategies [122,123,124].

Nanocelluloses can be classified in three main categories: (1) cellulose nanofibers (CNFs), also known as microfibrillated cellulose (MFC), and nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC); (2) cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs), also designated by nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) or cellulose nanowhiskers (CNWs); and, (3) BC or also named bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) [121]. The major difference between the CNFs and CNCs lies in their dimensions and crystalline structure. While CNFs have lengths in the microscale and diameters in the nanoscale, CNCs have both length and diameter that are in the nanoscale [125]; more precisely, CNFs are fibrils with lengths of a few micrometers and with diameters that range between 3 and 50 nm, whereas CNCs have a rod-like nanocrystal configuration with lengths ranging from 10 to 500 nm and diameters of few nanometers (Figure 2) [120]. Differences in the CNFs and CNCs crystalline structure result from their extraction process. CNF contains either crystalline regions or amorphous regions, in which the amorphous domains provide a certain flexibility to NFC. In turn, CNC are mostly nanoparticles that are made predominately of pure crystalline cellulose [126,127].

Figure 2.

a) TEM image of cellulose nanofibers (CNFs); b) SEM image of cellulose nanowhiskers (CNCs) that has been deagglomerated; and, c) SEM image of BC (adapted from [77] with permission from Royal Society of Chemistry, 2020).

The isolation of CNFs from different cellulosic origins is accomplished by means of mechanical treatments, often in combination with some chemical or enzymatic pretreatment followed by a disintegration step. The most common chemical pretreatments are perhaps those that render the pulp fibers (used when the source is wood) charged, e.g., anionic or cationic. This modification increases the electrostatic repulsion between the fibers, which is beneficial in the subsequent mechanical treatment steps, as it further promotes the fibers disintegration into nanofibers. The most used mechanical processes are the high-pressure homogenization, microfluidization, refining, and grinding, while the least used are the electrospinning, ultrasonication, cryocrushing, and steam explosion. However, all of these mechanical processes demand high energy consumption. Hence, chemical and enzymatic pretreatments, such as cationization, hydrolysis, (2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl) oxyl(TEMPO)-mediated oxidation, acetylation, and silylation, have been used to ease the mechanical treatment and, thus, reduce the energy consumption, while attaining a desirable surface chemistry. Still, caution should be taken during mechanical processing, since the nanofibers length depends on the degree to which the material has been exposed to this processing step. In addition, the cellulose source will also play a major role in the final product, as it determines the pretreatments that are to be carried out [127,128].

Two steps are also required to process CNC from raw cellulose: (1) homogenization pretreatment/purification, and (2) the separation of the purified cellulose into nanocrystals. To obtain cellulose nanocrystals, cellulose can be directly hydrolyzed. Acid hydrolysis has been the method of choice for many years to produce CNC. Generally, it requires sulfuric and hydrochloric acids, which starts by dissolving the disordered or para-crystalline regions, leaving behind the crystalline domains or the CNC that possess a higher acidic resistance. The temperature and time of hydrolysis, nature, and concentration of the acids and the fiber-to-acid ratio play an important role in the CNCs particle size, morphology, crystallinity, thermal stability, and mechanical properties. It is worth noting that surface sulfate esters are introduced to the CNCs during sulfuric acid hydrolysis, conferring the surface with a highly negative charge and making it accessible, for instance, to enzymes or proteins, a desirable outcome in biomedical applications [71]. Aside from hydrolysis, other methods have been reported to isolate CNCs, such as enzymatic hydrolysis, mechanical refining, ionic liquid treatment, subcritical water hydrolysis, and oxidation processes. Different sources, like plant cell walls, cotton, microcrystalline cellulose, algae, animals, and bacteria, have been used to obtain CNCs [81,129]. Like CNFs, the geometric dimensions and the final properties of the CNCs are directly dependent on the cellulosic source, the post- or pretreatments, and the subsequent preparation and processing conditions [130]. CNCs are characterized by their biocompatibility, biodegradability, high level of crystallinity (54–88%), excellent stability and mechanical performance (high strength as well as modulus), exceptional optical properties, and flexible surface chemistry [123,131].

BC is another class of nanocellulose materials that has been engineered with the goal of surpassing the limitations of cellulose and other natural or synthetic materials [132]. BC is chemically similar to the cellulose obtained from plants; however, it is free from lignin, pectin, and hemicelluloses, and it has a very low amount of carbonyl and carboxyl in its structure. BC is a biocompatible, highly porous, and highly crystalline (84–89%) polymer, with a high degree of polymerization (up to 8000), a finer web like network, and an extraordinary mechanical strength, particularly in the wet state, which was comparable to other nanofibers from plants. It is characterized by a superior water-retention capacity, and the ability to accelerate granulation tissue formation, making it very attractive for wound healing (Figure 2) [75,126]. Another, relevant property of BC is its in situ moldability (e.g., shaping during biosynthesis) [133]. Many bacteria from the genus Acetobacter, Agrobacterium, Pseudomonas, Rhizobium, Achromobacter, Bacillus, Azotobacter, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Salmonella, and Sarcina have been reported to secret BC as a protection mechanism against ultraviolet light or other microorganisms, like fungi and yeasts [126,129]. BC properties are highly influenced by the origin organism and culture conditions [128]. The most common BC producer is the gram-negative bacteria Gluconacetobacter xylinus, previously known as Acetobacter xylinum and secretes cellulose during metabolism of carbohydrates [132]. The fermentation method that is used more to produce BC has been the static culture, which increases the yields of BC, by producing BC layers of several centimeters of thickness under the surface of the culture medium. Here, however, it is necessary to monitor the media pH, since the accumulation of acids, such as gluconic, acetic or lactic, decreases the pH far below the optimum for bacteria growth and cellulose production. Alternatively, agitated cultures, airlift bioreactors, rotating disk bioreactors, stirred tank reactors with a spin filter, biofilm reactors with plastic composite supports, and trickling bed reactors may also be employed in the production of this cellulose type, preventing the conversion of cellulose-producing strains into cellulose-negative mutants [128]. BC can be produced in various forms, depending on the fermentation method; pellicles arise under static culture condition, while fibrils and sphere-like particles emerge under motion conditions [134]. The wastes from several industries (often rich in sugars), e.g., domestic, agricultural, cotton-based textiles, among others, are also gaining significance as carbon sources for BC production, as evidenced in Table 3 [132]. Celluloses with different degrees of crystallinity can be produced, depending on the source and culture production [133]. This is one of the most important properties in BC, since the crystalline microfibrils in its structure are responsible for its high tensile strength (200–300 MPa) and thermal stability. Its poor solubility in physiological media, as well as the absence of cellulases and beta-glucanases, which increase the stability and functionality of the polymer, has increased the interest of BC as additive or base for potential new biomaterials. To date, BC has been employed in the development of biomaterials for wound dressings, blood vessels, dental implants, scaffolds for tissue engineering of cornea, heart valve, bone and cartilage, and drug delivery applications [134].

Table 3.

Production of nanocelluloses (CNF, CNCs, and BC) from different sources.

4. Application in Wound Healing: Synergistic Effect with Specialized Biomolecules

In wound care, infections are a major concern, since they delay the healing process, leading to tissue disfigurement or even patient death. S. aureus and P. aeruginosa are the most common bacteria that are isolated from chronic wounds, being S. aureus usually detected on top of the wound and P. aeruginosa in the deepest regions. They can express virulence factors and surface proteins that affect wound healing. The co-infection of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa is even more problematic, since the virulence is increased; both bacteria have intrinsic and acquired antibiotic resistance, making the clinical management of these infections a real challenge [147]. In fact, the World Health Organization considers P. aeruginosa as one of the organisms in urgent need for novel, highly effective antibacterial strategies that combat its prevalence. Multiple strains of S. aureus, including methicillin-resistant and vancomycin-resistant strains, have been identified as high priority microbes in the fight against antimicrobial resistance build up [15]. In addition to the above, other microorganisms, such as beta-hemolytic streptococci, and mixtures of Gram-negative species, such as E. coli and Klebsiella strains, are also present in wounds. Bacterium native to human skin such as Staphylococcus epidermidis (Gram-positive), may also turn pathogenic when exposed to systemic circulation in the wound bed [148]. Therefore, immediate care of open wounds is pivotal in preventing infection [149]. To treat this problem, new alternatives of wound dressings have emerged with incorporated bio actives that are capable of fighting these infections and accelerating the healing process.

The performance of bioactive dressings processed via electrospinning is dependent on the polymer or polymer blends properties (i.e. hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity), drug solubility, drug-polymer synergy, and mat structure. Antimicrobial agent-loaded electrospun mats have shown superior performance to films produced by other techniques, in regard to water uptake (four to five times superior), water permeability, drug release rate, and antibacterial activity [9].

Drugs, nanoparticles, and natural extracts (Table 4) are some of the antimicrobial agents that have been incorporated in nanofibrous dressings, in order to reduce the risk of infection [61]. These compounds have been used for their anti-inflammatory, pain-relieving, vasodilation, and antimicrobial features [11].

Table 4.

Examples of compounds incorporated in electrospun nanostructures containing cellulose or its derivatives.

Several researchers claim that producing cellulose-based electrospun mats is a big challenge due to its highly crystalline structure, long chain length, increased rigidity, and strong inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bonding [150]. Selecting a proper solvent, adding other complementary polymers, or converting cellulose into its derivatives can facilitate this task. As seen in Section 3.1, the solvents or solvent systems most used for cellulose are the ILs, aqueous alkali/solvents (NaOH/urea), and polar aprotic solvents in combination with electrolytes (DMAc/LiCl); however, these are not very volatile, not being completely removed during electrospinning and, thus, limiting the use of cellulose in large scale productions. A proper solvent system is also very important in attaining appropriate viscosity levels, required for a successful electrospinning process. In fact, this is such an important processing parameter that to guarantee proper polymer solubilization, heaters have been placed within the electrospinning apparatus generating a new system, the melt-electrospinning (minimize the viscosity of spinning dopes) [151]. The option of transforming cellulose into its derivatives, such as CA, cellulose acetate phthalate (CAP), ethyl cellulose (EC), carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), hydroxypropylcellulose (HPC), among others, is by far the most recurrent alternative to reduce the complexity of processing cellulose via electrospinning. Besides, most of these derivatives require different pHs for solubilization, which is a great advantage in biomedical applications [152].

Modifications have been proposed to increase the effectiveness of immobilized drugs, natural compounds, peptides, or other biomolecules within a cellulose-based nanostructured surface. For example, Nada et al. activated CA by introducing azide functional groups on the residual -OH groups of the polymeric chains, enhancing the release kinetics of capsaicin and sodium diclofenac from the electrospun mat and, thus, promoting patient relief [153]. To confer biocidal properties to CA nanofibers, Jiang et al. modified their surface with 4,4’-diphenylmethane diisocyanate (MDI). This resulted in a 100% inactivation of S. aureus and a 95% of E. coli within 10 min of exposure, and complete death after a 30 min contact [154]. Nano complexes with CNCs were developed with cationic b-cyclodextrin (CD) containing curcumin by ionic association and used in the treatment of colon and prostate cancers [155]. Nanocellulose has also contributed to the development of new and more efficient strategies for these biomolecules’ delivery. The three -OH groups that were present in each individual glucose unit originate a highly reactive structure, which allows interaction with other molecules or with enzymes and/or proteins, contributing to overcome the low solubility of most drugs in aqueous medium [127]. Besides, the -OH groups can also be tailored by physical adsorption, surface graft polymerization, and covalent bonding to further improve the performance of the biomolecules. As a consequence of the bonds established, strong polymer-filler interactions are generated, significantly increasing the mechanical properties of material [156]. Nonetheless, the in vivo behavior of nanocelluloses is still little explored. Studies have reported that its toxicity depends on the solution concentration and its surface charges. In recent literature, nanocelluloses have not shown any toxicity at concentrations lower than 1 mg/mL; however, there are studies that reveal a concentration-dependent apoptotic toxicity of CNFs at 2–5 mg/mL. Additionally, anionic nanocelluloses, e.g., carboxymethylated CNF, have been reported to be more cytotoxic than cationic nanocelluloses, e.g., trimethylammonium-CNF [34]. Toxicity effects might arise from the diversity of chemical structures and properties between cellulose types and sources. Among nanocelluloses, BC is considered to be the most biocompatible and has already been applied in wound dressings [71]. Still, its electrospinnability is very challenging for the same structural reasons of cellulose [150].

The incorporation of BC into synthetic and natural polymers has been carried out to enhance their morphological features as well as physicochemical and biological performances. A wide variety of polymers, such as chitosan, polycaprolactone (PCL), polyethylene oxide (PEO), ethylene vinyl alcohol (EVOH), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polylactic acid (PLA), polyacrylonitrile (PAN), polyester, silk, and zein, have been blended with BC and processed by electrospinning. Functionalization with 3-aminopropyl triethoxysilane (APS) has been attempted to further enhance cell attachment and antibacterial properties of BC-containing electrospun membranes for wound healing. BC membranes grafted with two organosilanes and acetyled have also shown an improved moisture resistance and hydrophobicity [134]. Naeem et. al even synthetized in situ BC on CA-based electrospun mats in a process known by self-assembly to produce a new generation of wound dressings [157].

Even though CNF has already been applied as a reinforcing agent in many polymeric composites via electrospinning, no reports have been found regarding the incorporation of biomolecules along its fibers [158]. As such, in the following sections BC and CNCs will be explored in more detail.

4.1. Drug Loading

Numerous hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs have been incorporated into electrospun polymeric nanofibers. In general, the polymer is dissolved in an organic solvent and the drug is slowly added to the polymer solution under stirring in order to guarantee a homogeneous distribution. This strategy allows for a large amount of drugs to be loaded into the nanofibers by simply adjusting the final concentration of the solution. However, adding drugs directly to a polymer solution alters its conductivity, viscosity, and surface tension, affecting the electrospinnability of the polymer and the morphology of the obtained nanofibers. Besides, in this scenario, drugs tend to very rapidly leach in an aqueous environment [193], since they are preferentially located at or near the fibers’ surface [166]. The conventional electrospinning technique allows a somewhat control of drug release by modulating the pores size and density, and the polymers degradation rate; still, bursts of drug followed by cytotoxic effects remain [63]. Several research teams have focused on developing new drug delivery systems with a so-called effective controlled release to overcome this weakness. Multiple-fluid, coaxial and triaxial electrospinning approaches, capable of generating complex nanostructures, may allow a more effective control of this initial burst release by confining part of the drug to the fiber core and another to the surface. This way, during dissolution, the molecules at the core need to diffuse through an insoluble shell until reaching the bulk solution [169]. However, this is not always as straightforward. Yu et al. compared nanofibers that were produced from coaxial electrospinning at varying feeding rates. They realized that by varying just this one parameter the morphologies of the fibers obtained were completely different and that to condition drug release. They proved that the production of high quality ketoprofen-loaded CA nanofibers is not simply a result of dilution of the core solution by the sheath solvent. The most uniform fibers, with the smallest diameters, and extended drug release time were those that were produced with the lowest feed rate being applied to the sheath of CA [171].

Many attempts have been made to optimize the release kinetics of drugs over time resorting to different immobilization methods (Figure 3). Table 5 compiles some of the most successful formulations of drug and electrospun nanocomposites containing cellulose, CA, or any variation of nanocellulose. As explained earlier, CA is the oldest, most researched derivative of cellulose, and, as such, the drug loading of CA-containing electrospun wound dressings are more recurrent.

Figure 3.

Three modes of physical drug loading on the surface of electrospun nanofibers (reproduced from [194], with permission from Elsevier 2020).

Table 5.

Processing of cellulose-, CA- and nanocellulose-containing electrospun mats incorporated with drug molecules.

4.2. Nanoparticles (NPs)

Nanotechnology tools, particularly NPs, have been recognized as occupying a fundamental role in promoting wound healing, with reports on their exceptional antimicrobial, angiogenesis, immunomodulation, and cell and drug delivery, leading the way to new strategies for improving the response to antimicrobial and tissue regeneration therapies [8].

NPs are classified in light of their impact in cellular uptake, dimension (1–100 nm), shape, role, and nature (inorganic and organic). Carbon-based, metal and metal oxide, semiconducting and ceramic NPs are classified as inorganic, while organic NPs integrate those that are produced from polymers and derived from biomolecules [195]. NPs can act as delivery vehicles, protecting and releasing active compounds locally, or by intervening in specific functions via their intrinsic properties [6]. Their antibacterial potential results from their production of reactive oxygen species and their capability to bind and disrupt DNA or RNA functions that obstruct microbial reproduction [130]. By associating NPs with a textile or polymeric matrix synergistic actions can be revealed, generating a new formulation of active dressings [6,148]. The NPs with antimicrobial activity that have been explored in combination with dressings are the bioactive glass, gold, copper, cerium, zinc oxide, carbon-based, titanium dioxide, gallium, nitric oxide, and AgNPs [130]. These display bacteriostatic and bactericidal capacity, reduced in vivo toxicity (at low concentrations), are low cost, and possess physical, chemical, and biological features that trigger complex biological responses [196]. AgNPs can be highlighted from the group for their proved potential against multidrug resistant (MDR) bacteria [188]; they are capable of blocking the respiratory pathways of specific enzymes and damage the bacteria DNA, or even block the action of selected proteins involved in key metabolic processes [189,197]. In addition, AgNPs have been associated with decreased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-8 and increased levels of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-4, EGF, KGF, and KGF-2, with enhanced fibroblast migration and differentiation into myofibroblasts, macrophage activation, and improved proliferation and relocation of keratinocytes, all being very important phenomena in wound healing [198,199]. AgNPs are already clinically used, being found in dressings, gels or ointments for topical treatment of infected burns and open wounds, including chronic ulcers [6]. However, there are still some adverse effects arising from the excess use of AgNPs. At high concentrations, AgNPs may be toxic to the human cells, by inhibiting the recruitment of immune cells, the regrowth of epidermal cells, and, ultimately, hindering wound healing. Besides, like antibiotics, prolonged treatment with metal ions may result in the emergence of resistant bacterial strains. A balance between cell exposure and action against microorganisms is, therefore, required to prevent such events. Table 6 summarizes some of the most recent systems for wound healing that combine NPs with electrospun mats containing cellulose or its derivatives, in the most successful way.

Table 6.

Processing of cellulose-, CA- and nanocellulose-containing electrospun mats incorporated with nanoparticles.

Nowadays, the growing awareness of the NPs impact in the environment has led to the development of more eco-friendly approaches for inorganic NPs synthesis, which justifies new choices of solvents and reductive and stabilizing agents [200]. In fact, there are now approaches that resort to microbes, fungi, and vegetable, fruit, and plant extracts to produce metal and metal oxide NPs. There is still a long way until the optimization of such alternatives; however, it is already clear their economic and environmental potential over the current physical and chemical technologies [201,202].

4.3. Natural Extracts

Biomolecules that are derived from natural extracts are gaining more interest in biomedicine as alternatives to overcome the concerns associated with the resistance and toxicity of antibiotics and the overuse of silver-based compounds [206,207]. The use of plant extracts for the treatment of wounds and wound-related diseases is a very common practice. Thymol, asiaticoside, curcumin, zein, acid gallic, and gingerol are some examples of bioactive molecules used in combination with cellulose derivatives-containing electrospun nanocomposites. Their bioactive properties arise from alkaloids, phenolic, flavonoids, and terpenoids compounds, which are also endowed with immunomodulatory activities, which make these biomolecules capable of controlling the inflammatory response. Besides, these compounds are also responsible for these biomolecules antibacterial, insecticidal, antiviral, antifungal, and antioxidant properties.

The use of plant extracts in medicine dates back hundreds of years. For instance, natural extracts derived from Aloe vera such as emodin (3,8-trihydroxy-6-methyl-anthraquinone), an antioxidant compound, have been frequently used in the treatment of burns. Neem (Azadiracta indica) extracts containing omega fatty acids also have numerous medical and cosmetic applications. Ginsenosides found in the plant genus Panax (Ginseng) are often used in traditional Chinese medicine and exhibit anticancer activity. Indeed, various plant extracts and active components, formulated as nanofibers or nanoparticles, are regaining interest for therapeutic purposes [208], because of their low cost, bioavailability, and superior efficacy, with limited side effects, over the more current and synthetic alternatives.

Essential oils (EOs), which are extracted from aromatic plants, have intrinsic antibacterial, antifungal and insecticidal properties. Moreover, EOs are widely available natural compounds with a low degree of toxicity. They can be easily and efficiently combined with polymeric matrices to generate nanocomposites with improved antimicrobial features [67,168]; these are mainly conferred by active molecules present in their composition, namely terpenes, terpenoids, and other aromatic and aliphatic compounds. The EOs, and their respective components, hydrophobic character promote the partition of the lipids that are present in the bacteria cell membrane, increasing their permeability and, consequently, leading to the membrane rupture and leakage of intracellular content, ultimately inducing cell death. Therefore, EOs loaded dressings may act as powerful tools to circumvent bacteria multi-drug resistance in infected wounds [209]. In fact, studies have already shown the improved synergistic effect of the oregano EO with CA-based nanofibers against S. aureus, E. coli and the yeast Candida albicans (C. albicans), as a result of the potent antimicrobial character of the oregano oil molecular components carvacol and thymol [67]. Cinnamon, lemongrass, and peppermint EOs that are loaded onto CA electrospun mats have shown similar outcomes. However, it was also seen that the morphology of the mat is a determinant factor in the EOs antimicrobial assessment as the nanostructure fibrous network developed might impair direct contact with large sized microorganism, such as C. albicans. Regarding the modified dressings cytotoxicity, even though fibroblasts and human keratinocytes could attach and spread on the fibers surface, cell viability seemed to decrease with exposure time. The anti-proliferative effect of EOs against eukaryotic cells has already been reported [168]. This is the greatest limitation to a large-scale use of EOs as antimicrobial and regenerative biomolecules in wound healing. Still, the capacity to design and engineer systems that allow a gradual and continuous release of EOs at concentrations below the cytotoxic, while using the electrospinning technique, has been improving and has already revealed very promising results. In fact, studies have shown that CA-based electrospun nanostructures loaded with EOs to display a higher capacity to retain water and aromatic compounds, thus reducing the initial drug burst and extending release over time, this way increasing the effectiveness of the therapy above other non-reticulated systems [179,180]. Table 7 presents some of the most recent EOs loaded electrospun systems containing cellulose, CA or nanocellulose formulations, in which the above-mentioned properties and outcomes are the most noticeable. Several of those works also report on the modifications introduced by the EOs to the fiber diameters and the relative porosity of the engineered mats, which intimately affect the cell proliferation, migration, and capacity of EOs release without an adverse biological response.

Table 7.

Processing of cellulose-, CA-, and nanocellulose-containing electrospun mats incorporated with natural products.

4.4. Wound Healing Alternative Methods Containing Cellulose-Based Compounds

Wound healing is a highly complex process of tissue repair that relies on the synergistic effect of a number of different cells, cytokines, enzymes, and growth factors. A deregulation in this process can lead to the formation of a non-healing chronic wounds. Current treatment options are unable to meet the demand set by the environment surrounding these wounds. Therefore, multifaceted bioactive dressings have been developed to more efficiently respond to these wounds demands [206].

Surfaces have been physically and chemically modified, by changing the dressing topography or by introducing functional groups, like cell-recognizable ligands and bioactive molecules at the outermost layer, in order to improve the performance of electrospun polymeric nanofibers for skin regeneration. To accomplish such task, surface functionalization techniques, like the wet-chemical method, plasma treatment and graft polymerization have been applied. Pre- and post-electrospinning surface modifications are also very common; in pre-electrospinning bioactive molecules can be dissolved or dispersed in the polymeric solution, while in pos-eletrospinning physical adsorption, layer-by-layer (LbL) assembly and chemical immobilization are the most common strategies [61].

Alternatively to the earlier mentioned additives, drugs, nanoparticles, or natural extracts, other molecules, like growth factors, hormones, or enzymes, have also been incorporated onto nanofibrous dressings to promote wound healing [211]. Huang et al. produced CA nanofibrous mats that were used as a substrate to deposit LbL films, alternating between positively charged lysozyme-N-[(2-hydroxy-3-trimethyl-ammonium)propyl] chitosan chloride (LY–HTCC) compositions and negatively charged sodium alginate. The average fiber diameter increased with the increased number of bilayers, but only the samples that contained lysozymes were effective against bacteria [212]. Similar observations were made by Li et al. Here, lysozyme was combined with rectorite and electrosprayed onto negatively charged electrospun CA nanofibrous mats. The release profiles of lysozyme and its activity over time both demonstrated this formulation suitability for long-term applications [213]. Bio-based electrospun nanocomposites containing a pain reducing local anesthetic, the benzocaine (BZC), and the in situ pH-detecting dye bromocresol green (BCG) have been engineered to serve as a dual nano-carrier system for the treatment of infected wounds. BZC and BCG were introduced to CA-based nanofibers while using a single-step needleless electrospinning process. In vitro release studies demonstrated a pH dependent, controllable release of BZC, and confirmed the expected maximum drug release rate at pH 9.0, the average pH of an infected wound [214]. B. Ghorani et al. designed a β-Cyclodextrins (β-CD)/CA electrospun nanocomposite to efficiently trap and adsorb volatile molecules that are responsible for the unpleasant odors in chronic wounds. The data demonstrated an enhanced direct adsorption of a model odor compound, the hexanal (up to 80%), indicating the feasibility and potential of this formulation [24]. Vitamin A or retinol and Vitamin E or α-tocopherol have also been combined with CA solutions and electrospun in the form of cross-sectionally round, smooth fibers, with the average diameters ranging between 247 and 265 nm. The contents of Vitamin E and Vitamin A within the as-spun fiber mats were of ≈ 83% and ≈ 45%, respectively. Vitamin E was found to be more stable over time, with a maximum release of ≈ 95% of its loaded content after a 24 h period, against an ≈ 96% release of Vitamin A in only 6 h [215]. Cui et al., to improve the interaction between cells and scaffolds, modified the surface of thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) nanofibers with CNF particles by ultrasonic-assisted technique and used polydopamine as binding agent. These composites increased cell attachment and viability, revealing excellent biological and mechanical properties [216]. In another approach Kolakovic et al. produced drug loaded CNF microparticles via the spray drying method and revealed a sustained drug release by means of a tight network that limited the drug diffusion from the system [217]. These studies offer new structures for the delivery of effective treatments in wound healing, in which the sustainability of the materials and the preservation of the environment are decisive factors during processing.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Wound healing is a complex process that is regulated by three essential and distinct phases. Dysregulation or disruption of this process results in non-healing, very difficult to treat chronic wounds. In the last decades, remarkable progress has been achieved in the development of therapeutic approaches for these wounds. Electrospinning is regarded as one of the most effective tools for the production of dressings with a 3D structure that is similar to the skin extracellular matrix. These electrospun dressings display a large surface area-to-volume ratio and a porous structure that enhances homeostasis, exudates absorption, gas permeability, cell adhesion, migration, and proliferation and prevents the development of complicated infections. Herein, insights on the recent advances attained in the production of electrospun nanofiber meshes containing cellulose and its derivatives and modified with specialized biomolecules were provided. New, different, and more effective approaches have been developed for overcoming the concerns that are associated with the resistance generated by antibiotics and the overuse of silver compounds. Natural extracts from plants, alternative drugs, and organic and inorganic nanoparticles have been combined with selected nanofibrous systems based on cellulose components for an accelerated wound healing.

Even though many studies have reported on the availability of cellulose, its processing remains very challenging, with researchers turning to CA for facilitating dressing production via electrospinning. Indeed, CA is the most recurrent derivative of cellulose applied in wound dressings production, with many drug-loaded systems already engineered. Yet, nowadays, nanocellulose is gaining more ground by promoting binding with various biomolecules, including proteins and enzymes, via its highly available -OH groups that are also responsible for overcoming the low solubility of other forms of cellulose. These nanofillers have also contributed to significantly increasing the mechanical properties of wound dressings. Despite these advantages, more in vivo studies are required, since there is no consensus regarding its toxicity to human cells. From the collected data, it is clear that the different forms of cellulose presented are very attractive as renewable materials for wound dressings applications due to their high specific strength, high water-retention capacity, enhanced cell attachment, proliferation, and migration with no reports of toxic responses, and ability to be chemically modified to incorporate specific biomolecules. However, the incorporation of these agents is not always simple, with it being necessary to overcome the limitations that are associated with their electrospinnability. The correct selection of appropriated solvents, combination of polymers, pre-treatments to increase the solubility of these natural resources, and introduction of new chemical functional groups at the surface for biomolecule binding, are essential to obtain reproducible and effective wound dressings. The studies analyzed in this review reflect well the hard work around this subject and the increasing concern with the development of sustainable solutions that are still capable of accelerating the healing of wounds and preventing possible infections. There is still a long way for these formulations to reach large scale production with little environment impact. Even though, there are already greener alternatives resorting to clean solvents, low energy demand technologies, and biodegradable complementary polymers, there is still much work to be done to obtain a “green” and effective wound dressing to treat of infected wounds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.T., M.C.P. and H.P.F.; writing original draft, M.A.T.; writing-review and editing, H.P.F.; supervision, M.C.P., M.T.P.A. and H.P.F.; funding acquisition, M.T.P.A. and H.P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) under the scope of the projects PTDC/CTM-TEX/28074/2017 (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-028074) and UID/CTM/00264/2020.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), FEDER funds by means of Portugal 2020 Competitive Factors Operational Program (POCI) and the Portuguese Government (OE) for funding the project PEPTEX with reference PTDC/CTM-TEX/28074/2017 (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-028074). Authors also acknowledge project UID/CTM/00264/2020 of Centre for Textile Science and Technology (2C2T), funded by national funds through FCT/MCTES. M.A.T. also acknowledges FCT for the PhD grant SFRH/BD/148930/2019.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ghaffari-bohlouli, P.; Hamidzadeh, F.; Zahedi, P.; Fallah-darrehchi, M. Antibacterial nanofibers based on poly (l-lactide-co-d, l-lactide) and poly (vinyl alcohol) used in wound dressings potentially: A comparison between hybrid and blend properties. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2020, 31, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simões, D.; Miguel, S.P.; Ribeiro, M.P.; Coutinho, P.; Mendonça, A.G.; Correia, I.J. Recent advances on antimicrobial wound dressing: A review. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 127, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeli, H.; Khorasani, M.T.; Parvazinia, M. Wound dressing based on electrospun PVA/chitosan/starch nanofibrous mats: Fabrication, antibacterial and cytocompatibility evaluation and in vitro healing assay. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 122, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.H.; Huang, B.S.; Horng, H.C.; Yeh, C.C.; Chen, Y.J. Wound healing. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2018, 81, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Kowalczuk, M.; Heaselgrave, W.; Britland, S.T.; Martin, C.; Radecka, I. The production and application of hydrogels for Wound Management: A Review. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 111, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthet, M.; Gauthier, Y.; Lacroix, C.; Verrier, B.; Monge, C. Nanoparticle-Based Dressing: The Future of Wound Treatment? Trends Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, P.; Rezaeian, I.; Ranaei-Siadat, S.O.; Jafari, S.H.; Supaphol, P. A review on wound dressings with an emphasis on electrospun nanofibrous polymeric bandages. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2010, 21, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, N.; Karponis, D.; Mosahebi, A.; Seifalian, A.M. Nanoparticles in wound healing from hope to promise, from promise to routine. Front. Biosci. 2018, 23, 1038–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Unnithan, A.R.; Gnanasekaran, G.; Sathishkumar, Y.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, C.S. Electrospun antibacterial polyurethane-cellulose acetate-zein composite mats for wound dressing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 102, 884–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalise, A.; Bianchi, A.; Tartaglione, C.; Bolletta, E.; Pierangeli, M.; Torresetti, M.; Marazzi, M.; Di Benedetto, G. Microenvironment and microbiology of skin wounds: The role of bacterial biofilms and related factors. Semin. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 28, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambekar, R.S.; Kandasubramanian, B. Advancements in nano fi bers for wound dressing: A review. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 117, 304–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felgueiras, H.P.; Teixeira, M.A.; Tavares, T.D.; Homem, N.C.; Zille, A.; Amorim, M.T.P. Antimicrobial action and clotting time of thin, hydrated poly (vinyl alcohol)/cellulose acetate films functionalized with LL37 for prospective wound-healing applications. Appl. Polym. 2019, 48626, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghomi, E.R.; Khalili, S.; Khorasani, S.N.; Neisiany, R.E. Wound dressings: Current advances and future directions. Appl. Polym. 2019, 47738, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jannesari, M.; Varshosaz, J.; Morshed, M.; Zamani, M. Composite poly(vinyl alcohol)/poly(vinyl acetate) electrospun nanofibrous mats as a novel wound dressing matrix for controlled release of drugs. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011, 6, 993–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Dart, A.; Bhave, M.; Kingshott, P. Antimicrobial Peptide-Based Electrospun Fibers for Wound Healing Applications. Macromol. Biosci. 2019, 1800488, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Williams, G.R.; Wu, J.; Lv, Y.; Sun, X.; Wu, H.; Zhu, L.M. Thermosensitive nanofibers loaded with ciprofloxacin as antibacterial wound dressing materials. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 517, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M.A.; Amorim, M.T.P.; Felgueiras, H.P. Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) Based Nanofibrous Electrospun Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi Majd, S.; Rabbani Khorasgani, M.; Moshtaghian, S.J.; Talebi, A.; Khezri, M. Application of Chitosan/PVA Nano fiber as a potential wound dressing for streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 92, 1162–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Windbergs, M. Functional electrospun fibers for the treatment of human skin wounds. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 119, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golizadeh, M.; Karimi, A.; Gandomi-ravandi, S.; Vossoughi, M.; Khafaji, M.; Joghataei, M.; Faghihi, F. Evaluation of cellular attachment and proliferation on di ff erent surface charged functional cellulose electrospun nano fi bers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 207, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, K.; Cao, X.; Sun, R. Cellulose acetate fibers prepared from different raw materials with rapid synthesis method. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 137, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoshnevisan, K.; Maleki, H.; Samadian, H.; Shahsavari, S.; Sarrafzadeh, M.H.; Larijani, B.; Dorkoosh, F.A.; Haghpanah, V.; Khorramizadeh, M.R. Cellulose acetate electrospun nanofibers for drug delivery systems: Applications and recent advances. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 198, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, R.M.D.; Siqueira, N.M.; Prabhakaram, M.P.; Ramakrishna, S. Electrospinning and electrospray of bio-based and natural polymers for biomaterials development. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 92, 969–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorani, B.; Kadkhodaee, R.; Rajabzadeh, G.; Tucker, N. Assembly of odour adsorbent nanofilters by incorporating cyclodextrin molecules into electrospun cellulose acetate webs. React. Funct. Polym. 2019, 134, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadian, H.; Salehi, M.; Farzamfar, S.; Vaez, A.; Sahrapeyma, H.; Goodarzi, A.; Ghorbani, S. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of electrospun cellulose acetate/gelatin/hydroxyapatite nanocomposite mats for wound dressing applications. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 1401, 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsekova, P.B.; Spasova, M.G.; Manolova, N.E.; Markova, N.D.; Rashkov, I.B. Electrospun curcumin-loaded cellulose acetate/polyvinylpyrrolidone fibrous materials with complex architecture and antibacterial activity. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 73, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, R.R.M.; Senna, A.M.; Botaro, V.R. Influence of degree of substitution on thermal dynamic mechanical and physicochemical properties of cellulose acetate. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2017, 109, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yue, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, W.; Han, G. Preparation of cellulose acetate-polyacrylonitrile composite nanofibers by multi-fluid mixing electrospinning method: Morphology, wettability, and mechanical properties. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2020, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrigo, M.; McArthur, S.L.; Kingshott, P. Electrospun nanofibers as dressings for chronic wound care: Advances, challenges, and future prospects. Macromol. Biosci. 2014, 14, 772–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felgueiras, H.P.; Teixeira, M.A.; Tavares, T.D.; Amorim, M.T.P. New method to produce poly (vinyl alcohol)/cellulose acetate films with improved antibacterial action. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M.A.; Amorim, M.T.P.; Felgueiras, H.P. Cellulose Acetate in Wound Dressings Formulations: Potentialities and Electrospinning Capability. In Proceedings of the XV Mediterranean Conference on Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing—MEDICON 2019, Coimbra, Portugal, 26–28 September 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 76, pp. 1515–1525. [Google Scholar]

- Poonguzhali, R.; Basha, S.K.; Kumari, V.S. Novel asymmetric chitosan/PVP/nanocellulose wound dressing: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 1300–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]