- Article

Clock Synchronization with Kuramoto Oscillators for Space Systems

- Nathaniel Ristoff,

- Hunter Kettering and

- James Camparo

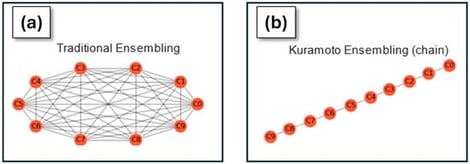

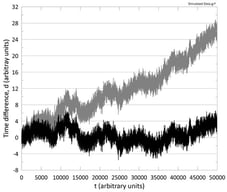

As space systems evolve towards cis-lunar missions and beyond, the demand for precise yet low-size, -weight, and -power (SWaP) clocks and synchronization methods becomes increasingly critical. We introduce a novel clock synchronization approach based on the Kuramoto oscillator model that facilitates the creation of an ensemble timescale for satellite constellations. Unlike traditional ensembling algorithms, the proposed Kuramoto method leverages nearest-neighbor interactions to achieve collective synchronization. This method simplifies the communication architecture and data-sharing requirements, making it well suited for dynamically connected networks such as proliferated low Earth orbit (pLEO) and lunar or Martian constellations, where intersatellite links may frequently change. Through simulations incorporating realistic noise models for small-scale atomic clocks, we demonstrate that the Kuramoto ensemble can yield an improvement in stability on the order of 1/√N, while mitigating the impact of constellation fragmentation and defragmentation. The results indicate that the Kuramoto oscillator-based algorithm can potentially deliver performance comparable to established techniques like Equal Weights Frequency Averaging (EWFA), yet with enhanced scalability and resource efficiency critical for future spaceborne PNT and communication systems.

15 January 2026