Abstract

This paper presents a theoretical framework modeling space-time as a quantized elastic medium. This elastic model is not intended to replace general relativity, but to offer a complementary mechanical interpretation in the approximation of the weak gravitational field. The goal is not to redefine gravity, but to explore whether this elastic formalism can simplify certain aspects of space-time dynamics, provide new insights, and generate falsifiable predictions—particularly in contexts where analytical solutions in general relativity are difficult to obtain. As originally envisaged by A. Sakharov, who associated general relativity with the concept of space-time behaving like an elastic medium, this paper introduces the notion of the “elasther” and reinterprets gravitational effects, time dilation, and phenomena commonly attributed to dark energy and dark matter through analogies with established mechanical principles such as Hooke’s law, thermal expansion, and creep.

1. Introduction

Long before the rise of modern physics, time was a central theme in philosophical inquiry—from Plato’s vision of time as the ‘moving image of eternity’ to Kant’s conception of it as a pure form of intuition. Over the centuries, thinkers have explored time as both a metaphysical and experiential phenomenon, laying the groundwork for its later formalization in scientific theories.

With the scientific revolution and the writing of nature in mathematical language that began with G. Galilei, I. Newton (1643–1727) introduced into his “philosophiae naturalis Principia Mathematica” (1687) [1] the idea of an “absolute, true, and mathematical time, flowing uniformly” (tempus absolutum), independent of space and events. A. Einstein (1879–1955) showed in 1905, and again in 1915 and 1916, in his theory of special [2] and general [3,4] relativity, that time is relative, inseparable from the geometry of space-time, and influenced by gravitation. Quantum mechanics, on the other hand, retained an external and uniform time to describe probabilistic phenomena, without managing to unify it with general relativity. Since then, more than 120 years of measurements have shown that he was 100% right (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Principal tests of general relativity.

Time is no longer an independent and absolute entity. Since the work of Einstein, it must be considered as inseparable from space, together forming a four-dimensional structure: space-time. With special relativity, durations lengthen as we draw closer to the speed of light: time becomes relative to motion. General relativity shows that time is sensitive to gravitation: it slows down near large masses.

But beyond these physical effects, fundamental questions remain: What is time? What is its driving force? What is it that makes each present moment tirelessly become the past, replaced without interruption by a new present moment, which has occurred since the dawn of time? Why is there an arrow of time, this irreversible orientation that prohibits us from rewriting the past, which is frozen forever?

What if time was not a primitive given, but an emergence linked to deeper phenomena—gravitation, entropy, temperature, and the structure of space-time itself? Thus, each one of us, in his or her own way, has tried to unravel the mystery of time, but no one—neither a philosopher nor a physicist, to our knowledge—has considered, as this work proposes, that time can be the manifestation of a mechanical deformation of a quantified elastic medium.

This paper does not claim to answer all these questions, far from it. It simply envisages approaching time from a different, more mechanistic angle since we will see that general relativity in weak fields can be modeled as an elastic medium that behaves like true space-time, an idea suggested by A Sakharov in his 1968 paper [12], subsequently taken up by many authors (J.L. Synge [13]; C.W. Misner, K.S. Thorne, and may others [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. The concept of a “deformable elastic quantified elastic medium or jelly” is detailed by T. Damour in his book Si Einstein m’était conté [30] and in at least one of his lectures or other books [31]. L.D. Landau and E.M. Lifchitz in [32] and C.W. Misner, K.S. Thorne, J.A Weeler in [33]) and particularly well formalized the concept of spacetime strained elastically by its intrinsic loading It is therefore this original approach to relativistic time [34,35,36,37] associated with an equivalent elastic medium that I will study in this paper. In [12], according to A. Sakharov, the action of space-time depends on curvature (R is the invariant of the Ricci tensor and G the gravitational constant).

The presence of this action results in a “metric elasticity” of space, that is, the generalized forces that oppose the curve of space.

This manuscript presents a unifying synthesis, bringing together for the first time within a single paradigm—that of “quantum beams”—phenomena previously justified in a scattered manner across the literature. Its innovative and relevant character lies in this integration.

The approach is to model space-time not as a mere pedagogical metaphor, but as a tangible physical hypothesis: a quantized elastic medium, termed the ‘elasther,’ different of the old ether that was not possible to measure following A.A Michelson, E.W. Morley [34] under weak-field conditions. In parallel, relativistic effects of the time have been measured by J.C. Hafele, R.E. Keating [35,36,37]. This proposition, grounded in prior publications and measurements from general relativity (gravitational waves A. Einstein [38], Lense-Thirring effect. cf. Table 1), is formulated as a testable physical and ontological model of a vacuum structure, a sort of crystal that behaves as a potential elastic medium made of these quantum beams, where the space-time strains manifest themselves. The article therefore focuses on presenting the hypotheses, models, results, and validation tests, with detailed mathematical demonstrations systematically referenced in the relevant paragraphs and cited publications (e.g., [9] for the Shapiro effect of time, [39,40] for the vacuum energy from Casimir force, [41,42,43] for Higgs theory and associated tests, [44,45,46] for the geometric torsion and defect theory).

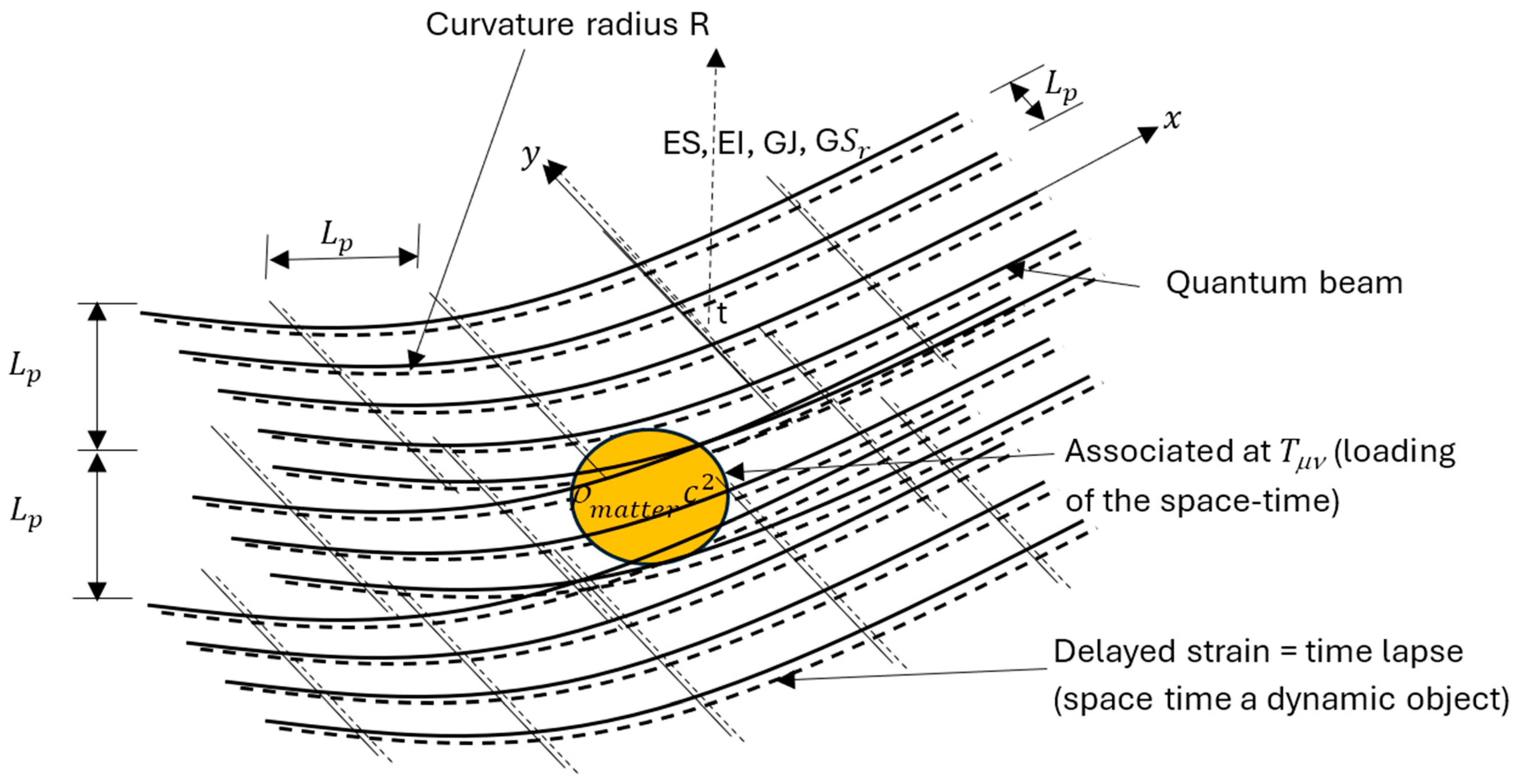

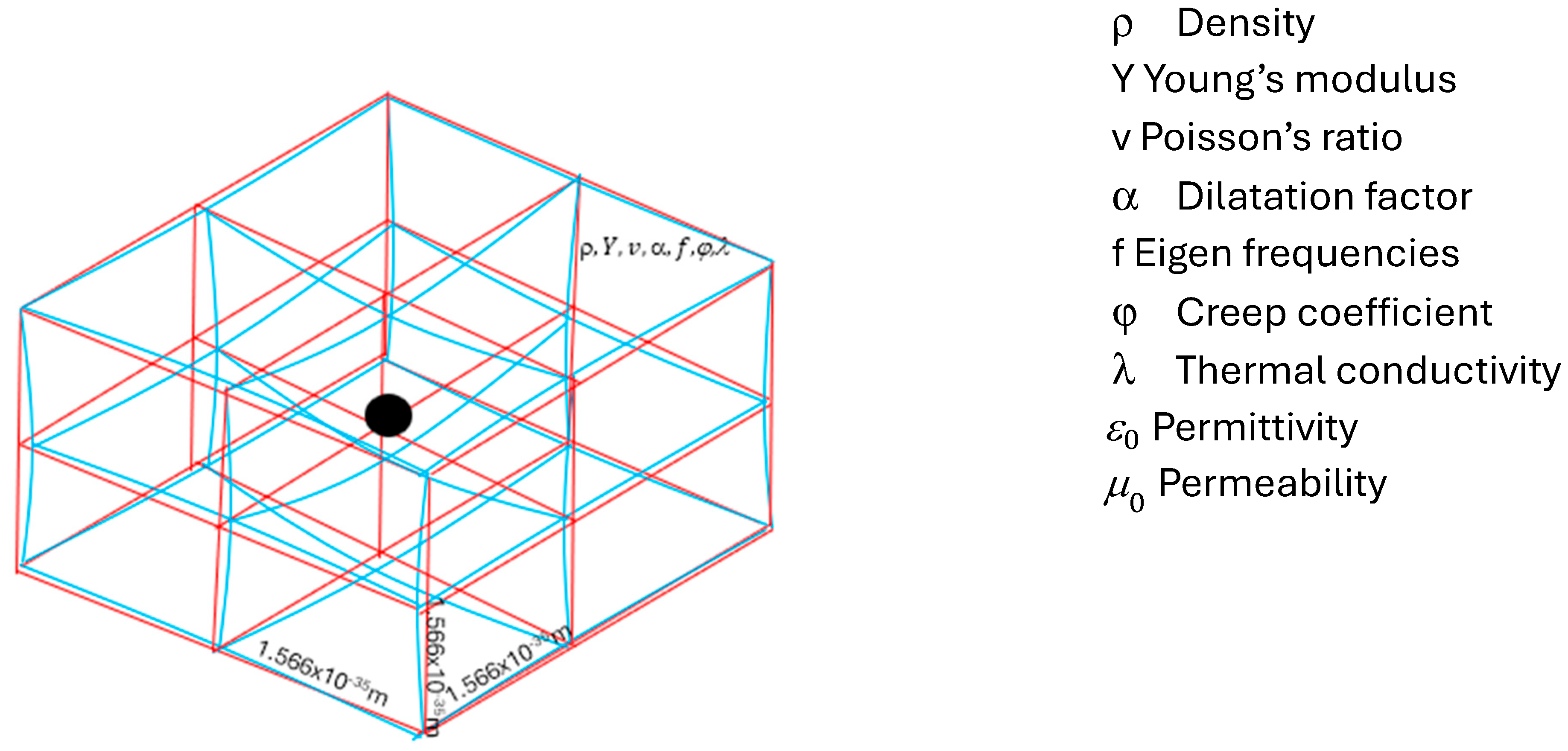

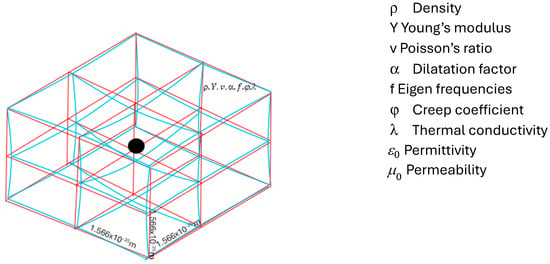

The theory of quantum beams is a mechanical and mathematical model that discretizes space-time (and the quantum vacuum) into a network of Timoshenko beams (see Figure 1 (D. Izabel, Y. Remond, M.L Ruggiero [25,26,27,28]) basing on crystal analogy [47,48,49]. These elements possess mechanical properties such as Young’s modulus E = Y, density ρ, Poisson’s ratio ν, inertia in bending I and torsion or shear G, thermal conductivity λ, dilatation , and a creep coefficient φ. This formalism allows for the reproduction of space-time strains (see Table 1) and elastic behaviour demonstrated by the sun eclipse and stars motions by A. Eddington in 1919 [5]. The different aspects of the model and their connections with various physical theories are as follows:

- Statically: General relativity in weak field, e.g., the instantaneous strains of gravitational waves are modeled by trusses of beams (D. Izabel, Y. Remond, M.L Ruggiero [25,26,27,28]).

- Dynamically: The eigen vibrations of these beams reproduce the quantized aspects of quantum mechanics (D. Izabel approach of the 4th order and 2nd order Schrödinger equation).

- Instabilities: The buckling of beams under compression provides an analogy for symmetry breaking in quantum field theory e.g., for the Higgs symmetry breaking mechanism (J. Iliopoulos approach).

- Plasticity: The overloading of beams through the formation of a plastic hinge under a localized and intense load can be seen as an analogy to the black hole mechanism described by J.P. Luminet [50], where a heavy mass is concentrated geometrically in a very small region (a singularity) on the fabric of space-time.

- Defects in the crystal lattice: They provide an analogy for the Einstein–Cartan extension of GR, where intrinsic spin (ħ/2) of fermions couples algebraically to geometric torsion in space-time (Hehl and al approach). These defects also suggest a way to assembly sheets of space along the propagation direction of the gravitational waves (D. Izabel, Y. Remond, M.L Ruggiero [25,26,27,28]).

- Gravitational wave: the interconnected network of stiff beams enables the propagation of vibrations generated by intense astrophysical events such as black holes coalescence [10] or neutron stars kilonovae [11].

The model also generates new and falsifiable predictions, notably other polarizations for gravitational waves (primarily in the direction of propagation) (D. Izabel, Y. Remond, M.L Ruggiero [27,28]) and lateral movements of interferometer arms (D. Izabel [25]). Furthermore, it proposes mechanistic explanations for several cosmological enigmas:

- Dark Energy: Interpreted as curvature induced by a thermal gradient between the cold vacuum and the warm cosmic web. This includes phenomena such as Hawking’s black hole evaporation [51,52,53,54], the effects of time and temperature [55,56], black hole evaporation through hydroacoustic analogy [57], thermal curvature of space and dark energy (D. Izabel [58]), as well as other aspects related to time and thermodynamics [59,60,61,62,63].

- Dark Matter: Replaced by additional vacuum deformations due to creep under long-term loading since the big bang (D. Izabel [64]), without requiring additional exotic mass.

Thus, the various strains [6,10,11,65] within this ‘cosmological crystal,’ which may contain defects [66], form the basis of a new quantum beam model of space-time and vacuum.

The quantum vacuum is no longer empty but consists of a foliated structure. To reconstruct the elastic medium in 3D, general relativity must be supplemented with an elastic tensor describing the vacuum’s behavior (D. Izabel, Y. Remond, M.L Ruggiero [28]), and the Einstein constant (κ) the flexibility of the space time is modulated by a creep coefficient (φ) (D. Izabel [64]). The 3D structure is finally connected via the addition of geometric torsion of the Einstein–Cartan type (D. Izabel, Y. Remond, M.L Ruggiero [27]).

This model does not claim to explain everything. It remains silent on the ultimate nature of these quantum beams or the global shape of the universe. Instead, it offers a unifying framework for disparate physical phenomena (general relativity, quantum mechanics, quantum field theory, dark energy and matter) under a single mechanical, elastic paradigm of the vacuum. It resembles a new theory of the ‘elasther,’ emerging from the energy of the vacuum (see e.g., Casimir Energy) and exhibiting static, dynamic, unstable, thermomechanical, and viscoelastic behaviors.

Finally, this quantum beam model connects with other theories through certain concepts: it borrows the idea of vibrating elements from string theory (G. Veneziano [67]) but replaces them with much stiffer beams, consistent with the extreme rigidity of space-time (1/κ); and it adopts the discretization principle of loop quantum gravity (C. Rivolli and L. Smolin [68]) by reconstructing space-time from 3D assemblies of beams, integrating the fourth dimension through the evolution of deformations (total deformations = instantaneous deformations + time-delayed deformations). This model, which preserves symmetry and covariance (see Appendix A) and is compatible with the ADM formalism [69] used in numerical relativity, In certain respects, this approach aligns with alternative theories such as MOND [70,71,72], through the pursuit of a minimal set of foundational hypotheses in accordance with Occam’s razor. Furthermore, the quantum beam model resonates with cosmological phenomena, including the concept of a ‘cosmological crystal’ at the epoch of cosmic microwave background emission [73,74], and gravitational lensing (space curvature) [7,8].

The term “quantized elastic medium” used throughout this manuscript refers to a structured model in which space-time is discretized into elementary elastic units—quantum beams in vibration—each endowed with mechanical properties such as bending inertia, torsion, Young’s modulus as defined by R. Weiss in its Nobel lecture [75] shear modulus, thermal expansion, and creep coefficients. These beams form a laminated crystal-like structure, as developed in [25,27,28], and their collective behavior reproduces both gravitational and quantum phenomena. The quantization arises from the discrete nature of these beams and their vibrational modes, which are analogous to quantized energy levels in solid-state physics D. Izabel [76]. The macroscopic image of this crystal can be interpreted through the power spectrum of temperature fluctuations emitted by the cosmic microwave background, viewed as an inverse X-ray diffractogram, where the first four peaks are predicted by a new cosmological Bragg law D. Izabel [77]. The link of the model with the standard model and Quantum Field Theory is the correlation and analogy between the discretization aspect of the vibration of the beams and quanta in quantum mechanics [76,78,79,80], the instability in compression of the beam and the symmetry break mechanism in QFT J. J. Iliopoulos [81].

In summary, the elastic model of space-time is treated here as a testable effective field model rather than a metaphysical ontology. Whether the underlying structure of the vacuum truly corresponds to a physical substrate or only to a useful mathematical analogy remains open and must be decided by experimentation.

2. Methodology

While this work originates from an analogy between general relativity and continuum mechanics, it goes beyond metaphor. The elastic model proposed here is not intended to replace general relativity, but to offer a complementary mechanical interpretation in the weak-field regime. It is treated as a testable effective model, grounded in measurable strain phenomena such as gravitational waves and Shapiro delay. The goal is not to redefine gravity, but to explore whether this elastic formalism can simplify certain aspects of space-time dynamics, provide new insights, and generate falsifiable predictions—particularly in contexts where analytical solutions in GR are difficult to obtain.

Consequently, in this paper, I analyze the following aspects:

- I start by addressing the state of the art regarding time with the following:

- The time bent by gravitation according to the general relativity of A. Einstein.

- Then, I present contemporary developments concerning time, all published in reputable peer-reviewed journals:

- Elastic time in the context of the model of space-time with an elastic medium;

- Temperature-sensitive space-time according to Hawking radiation to temperature-sensitive elastic time;

- Creep-sensitive elastic space-time and consequences for time;

- Plasticity of the elastic medium and infinite stretching of time;

- Foliation of space-time and time lapse in the case of gravitational waves—modified theory of general relativity with addition of Einstein–Cartan geometric torsion,

- In the context of a discussion of the elastic medium model, I highlight the different consequences implied by the different research studies noted in Section 2:

- Consequence of a variation in time and space as a function of temperature in connection with dark energy;

- Consequence of a variation in time and space by creep of space-time in connection with dark matter;

- Consequence of the foliation of space-time for the nature of time in the case of an equivalent elastic medium in connection with the possible emerging mechanistic nature of time.

3. State of the Art

Time Bent by Gravitation According to the General Relativity of A. Einstein

In 1915 [3], and again in 1916 [4], Albert Einstein published the theory of general relativity. This is based in particular on the principle of equivalence, according to which it is impossible to locally distinguish a physical experiment carried out in an elevator subject to the Earth’s gravity from an identical experiment conducted in an elevator located in a vacuum, far from any mass or energy that could generate gravitation, but accelerated upwards.

Einstein shows that in an accelerated elevator, a ray of light passing horizontally through the elevator appears to deflect downwards, hitting the opposite wall at a lower position. By reciprocity, as stated according to his principle of equivalence, he concludes that gravity must also bend the path of light, even though it is devoid of mass. Gravitation is therefore no longer considered a force in the classical sense, but a manifestation of the geometric curvature of space-time induced by the presence of mass and energy. Light follows this curvature during its propagation.

Einstein calculated his field as shown in Equation (2), so that in the weak-field regime (3), they found the Poisson equation (4), which, in turn, led to Newton’s law of gravitation, which works very well in this low-gravitation regime. Remarkably, this correspondence is obtained from the temporal component of Einstein’s equations (μ = 0,ν = 0), whereas Newton based his mechanics on an exclusively spatial conception. This was a major conceptual reversal in the history of physics. Thus, the equation of general relativity without a cosmological constant Λ (I will come back to this when I discuss the effects of temperature and dark energy on space and time) is written with the Ricci tensor, R the scalar curvature, the metric, and the energy momentum tensor:

In a weak field, this equation becomes, for the time component 00 with the Laplacian operator, the gravitational potential, and ρ the mass density,

Simplifying by c2/2, this again gives Poisson’s equation, where is the Laplacian operator, the gravitational potential, and the mass density:

In a weak field, Einstein’s equation of the linearized gravitational field is written [38] as

where h is the trace of , the D’Alembert operator, and the stress energy tensor. The gauge state taken is with

Then, he showed in 1916 [38] that in a vacuum, there is no “loading” of the space-time (); gravitational waves exist based on the following equation:

Thus, the equation of general relativity of A. Einstein [38] in a weak field uses a flat metric called Minkowski, to which is added a small geometric perturbation related to gravitation. The indices μ and ν are 0 for time and 1 to 3 for space coordinates.

It is recalled that in general relativity, each term constituting this metric , which in fact represents gravitation as a geometric effect, that is to say, space-time strain, constitutes the coefficients of the terms of an infinitesimal distance interval squared a Pythagoras theorem extension in 4 dimensions. The indices 00, 01, 02, and 03 and their symmetric represent the components of the tensors related to time. Component 00 represents the 100/100 temporal aspect of this space-time metric. Thus, is the term associated with it, which therefore reflects the distortion of space-time related to time.

The proper time τ measured by a clock is then written as

So, it is clear that gravity affects the rate at which proper time elapses for an observer. This is Einstein’s second great discovery. Since then, we have taken measures that confirm this. Indeed, a remarkable test of general relativity, demonstrating that gravitation curves time, is the Shapiro effect. Proposed by Irwin Shapiro in 1964 [9], this effect consists of measuring the time delay experienced by a radio signal when it passes close to a massive body, such as the Sun. According to general relativity, the presence of mass bends space-time, and this curvature slows down the propagation of the signal, even if it travels at the speed of light. This measurable delay—called Shapiro delay—is direct evidence that time is affected by gravitation. This phenomenon has been confirmed experimentally thanks to radar measurements sent to planets such as Venus or Mercury and is one of the four classic tests of general relativity. Thus, time is no longer a primitive and absolute quantity, but a dynamic physical variable that depends on motion and gravitation. This relativistic view, confirmed by more than a century of experiments (see Table 1), will serve as a foundation for the rest of this paper, where I propose going further: simulating time deformation as a mechanical deformation within a quantized elastic medium—a paradigm shift that opens up new perspectives on the nature of the vacuum and the structure of space-time.

4. Contemporary Developments over Time

4.1. Elastic Time in the Context of the Space-Time Model with an Elastic Medium

4.1.1. Elastic Model and Theory

In weak gravitational fields, as shown in the introduction, space-time behaves as a deformable elastic medium that we call “elasther” a sort of “elastic jelly” that could be modeled following our approach with a quantum microscopic structure made of quantum beams (see Figure 1). Thus, vacuum is no longer empty; it is inhabited by space-time and by the quantum fluctuations of the vacuum in field theory, as shown in particular by Casimir with the experiment of the two plates that come together under the effect of the fluctuations of the quantum vacuum, whose ground state is not zero (H. Casimir [39,40]), or in 2012, with the Higgs field and its famous boson, which makes it possible to give mass to particles [41,42]. This space-time, a “deformable elastic quantified elastic medium [29,30,31]”, or “elasther”, which is a cosmic web or cosmological crystal [44,45,46,47,48,49], according to the name given to it by various authors, follows Hooke’s law D(g) = K T [30], where D(g) represents the tensor of the deformations as a function of the metric g, K the flexibility in the mechanical sense (force F, displacement δ) of space-time (F = kδ or δ = 1/k F = K δ), and T the tensor of tensions within this space-time.

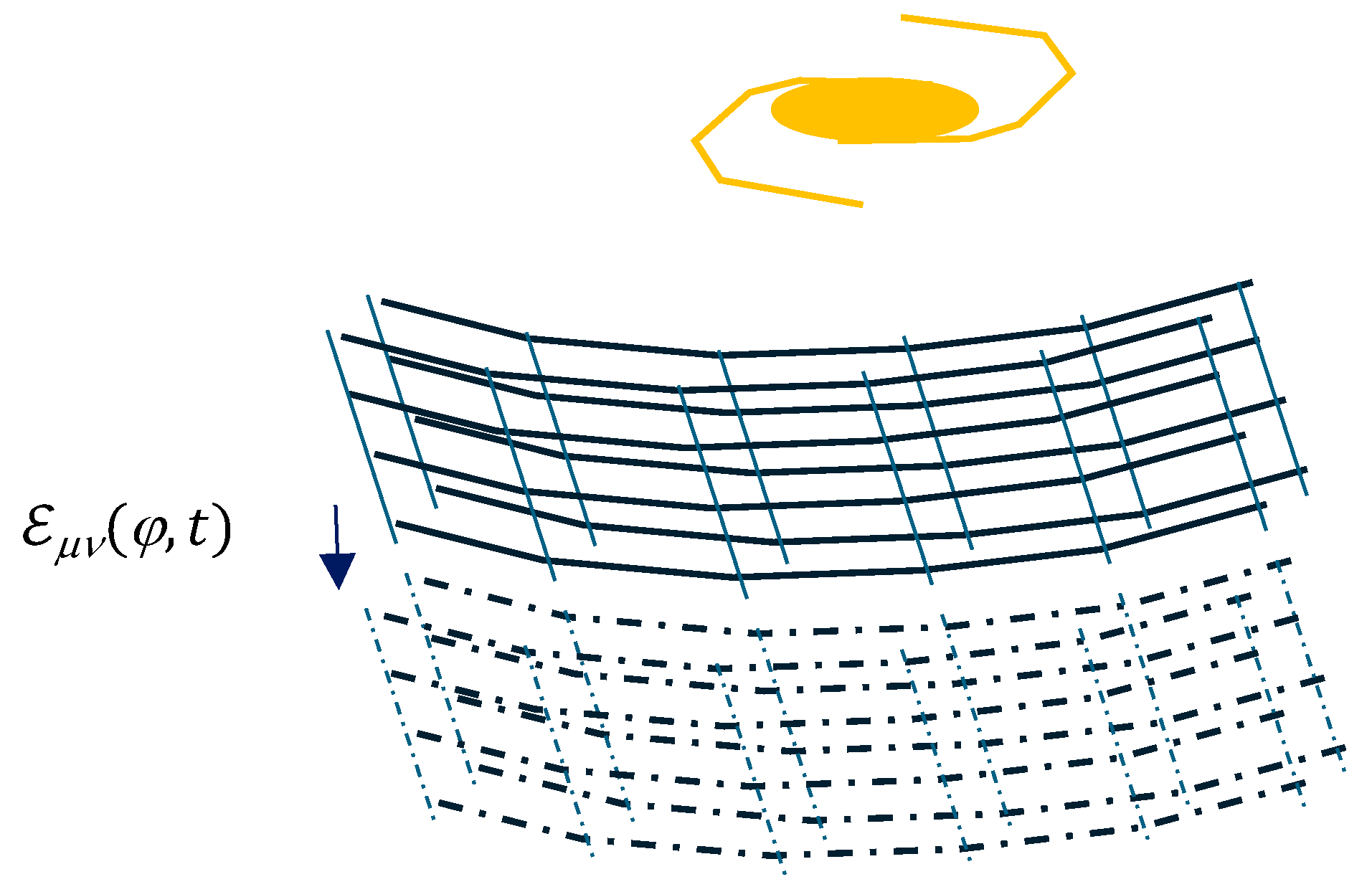

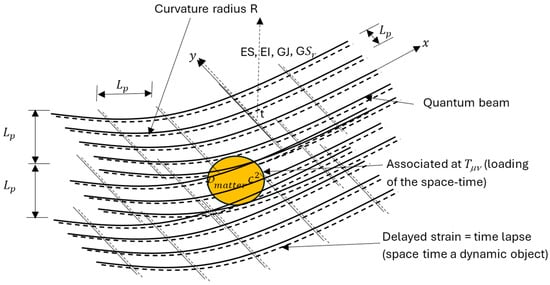

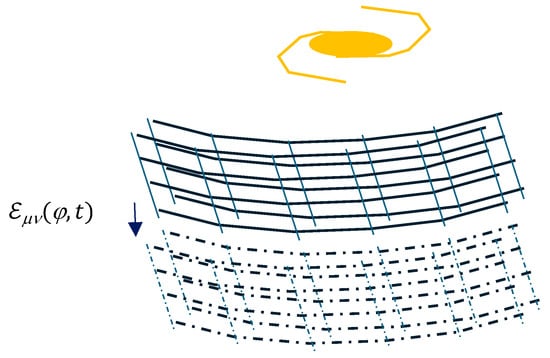

Figure 1.

Representation of the “elasther” in 4 dimensions in the framework of the model of the elastic medium made up of small quantum-dimensional beams (link with A Sakharov)—the dashed lines represent the deformations associated with time propagating at the speed of light arriving with a delay, and the instantaneous deformations related to space are represented in solid lines.

In the weak-field approximation of gravitation, the space-time metric is considered a small perturbation of the flat Minkowski metric, expressed as , where represents the perturbation tensor. Within this regime, a formal analogy emerges with continuum mechanics: the metric perturbation tensor becomes equivalent to twice the strain tensor of an elastic medium (T. Tenev and M.F Horstemeyer [19,20]). Consequently, Einstein’s coupling constant can be interpreted as the mechanical flexibility of the medium, analogous to the expression , where is Poisson’s ratio and Young’s modulus. Furthermore, the energy momentum tensor corresponds to the stress tensor in the elastic framework, representing internal constraints within the structured vacuum. can be seen also as the loading of the space-time within it. This analogy provides a mechanical interpretation of gravitational phenomena in weak fields, bridging general relativity and the physics of deformable media.

This model was envisaged first by A. Sakharov [12] and was then mathematically developed by many authors [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], including T. Tenev and M.F. Horstemeyer, who, in [19,20], have concretely shown that this perturbation of the metric is equivalent to twice one elastic strain tensor as described in continuum mechanics. We will come back to this later.

When applied to the 00 component, this implies that the temporal dimension (c × dt) constitutes a genuine elastic displacement, to be considered alongside the classical spatial displacements of continuum mechanics for each of the spatial coordinates . The effect of time’s curvature by gravitation is thus visualized through a mirror analogy, mechanized by a deformation acting in the fourth dimension of a particular geometry linked to space-time.

Furthermore, within the elastic medium framework, publications [19,25,26,27,28] demonstrate that the energy-momentum tensor corresponds to a four-dimensional stress tensor . Indeed, the expression of the stress tensor at low speed as a function of the energy density ρ and based on the multiplication of velocities and (see [25] Appendix A) is

In general relativity, the energy momentum tensor for a pressure-less dust is given by

where is the energy density, and the four-velocity. However, this expression is a simplified approximation valid only for non-interacting particles moving collectively. For a continuous medium, a more general formulation is required:

where is the energy density, the pressure, and the metric tensor. In the context of the elastic metric approximation proposed here, an analogous formulation remains to be fully developed. Nevertheless, the stress energy tensor may be interpreted as the mechanical stress tensor of the elastic medium, incorporating both internal energy and pressure-like terms arising from deformation. This opens up the possibility of extending the model to include anisotropic stresses and elastic moduli, bridging relativistic dynamics and continuum mechanics.

In the context of vacuum modeling, the classical energy momentum tensor vanishes, as no matter or non-gravitational fields are present. However, to preserve the mechanical analogy and maintain a Hookean-type relationship between stress and strain, it becomes necessary to introduce an additional tensor as done by several authors [82,83,84,85] representing the intrinsic elastic stress energy of the vacuum itself. We will see later the connection with the covariant aspects [86,87], long time strains with dark matter [88], crystal characteristic [89,90,91,92] or other dark matter effects [93,94,95,96,97]. This tensor characterizes the internal constraints and deformation energy of the structured vacuum, modeled as an elastic medium that can be considered an isotropic transverse. In this framework, Einstein’s field equations are extended to include this contribution, taking the form (see [28]).

where (see D. Izabel’s thesis), with being the effective, what we call Young’s modulus matrix of the vacuum and the strain tensor.

This addition allows the vacuum to be treated as a mechanically active medium, capable of storing and transmitting deformation energy even in the absence of external sources, thereby reinforcing the elastic interpretation of space-time in the weak-field regime. Thus, the quantum beam model of vacuum, as defined in D. Izabel’s thesis [98], incorporates the following key mechanical characteristics:

- : Space-time couplings. Could describe the Lense–Thirring effects. Related to the geometric twist in Einstein–Cartan;

- : Spatial Poisson coefficients as found for the GW waves [25,26,27,28]. between space sheets;

- Symmetry: In classical elasticity, . Poisson’s ratio of such an anisotropic medium is equal to = 1 (issued of GW strains [25,26,27,28]);

- Young’s modulus associated with space components in the transverse plane (issue of truss plane models working in traction/compression described in D. Izabel’s thesis [98]); in the propagation direction, small (value unknown because no experience allows us to determine it (see [25,26,27,28]));

- Young’s modulus associated with time component (issue of membrane model generally used to simulate Newton gravitation and Poisson’s equation described in D. Izabel’s thesis [98]).

The addition of a supplementary tensor to the right-hand side of Einstein’s equations requires careful consideration regarding general covariance (see Appendix A) and conservation laws. To prevent any violation of covariant invariance, we assume that derives from an effective Lagrangian describing the intrinsic elasticity of the vacuum. Furthermore, the conservation condition must be respected, implying that is not independent but coupled to the matter energy-momentum tensor. In our approach, interacts with the space-time geometry in a covariant manner, and its interpretation as a vacuum deformation energy tensor allows it to respect the geometric constraints imposed by the Einstein tensor. This extension, while bold, is grounded in a logic that preserves the fundamental principles of general relativity.

Moreover, the constant (Unit N−1) is strictly equivalent if we reduce it to m2, with the elastic flexibility of space-time (and so a vacuum in our analogy) in Pa−1, i.e., inversely to its Young’s modulus E = Y in Pa [25,26,27,28]. So, the state of the art is sufficiently consistent and verified, allowing us to affirm that general relativity in a weak gravitational field is, by mirror effect or model, the equivalent of one of Hooke’s laws, such as the one used in the strength of materials and well known in structural engineering. This Hooke’s law takes two forms depending on whether we are considering elongation or shortening ε under normal stresses σ:

or considering angular distortions γ under tangential stresses τ.

Both depend on Young’s modulus E and Poisson’s ratio ν, characterizing the equivalent elastic medium.

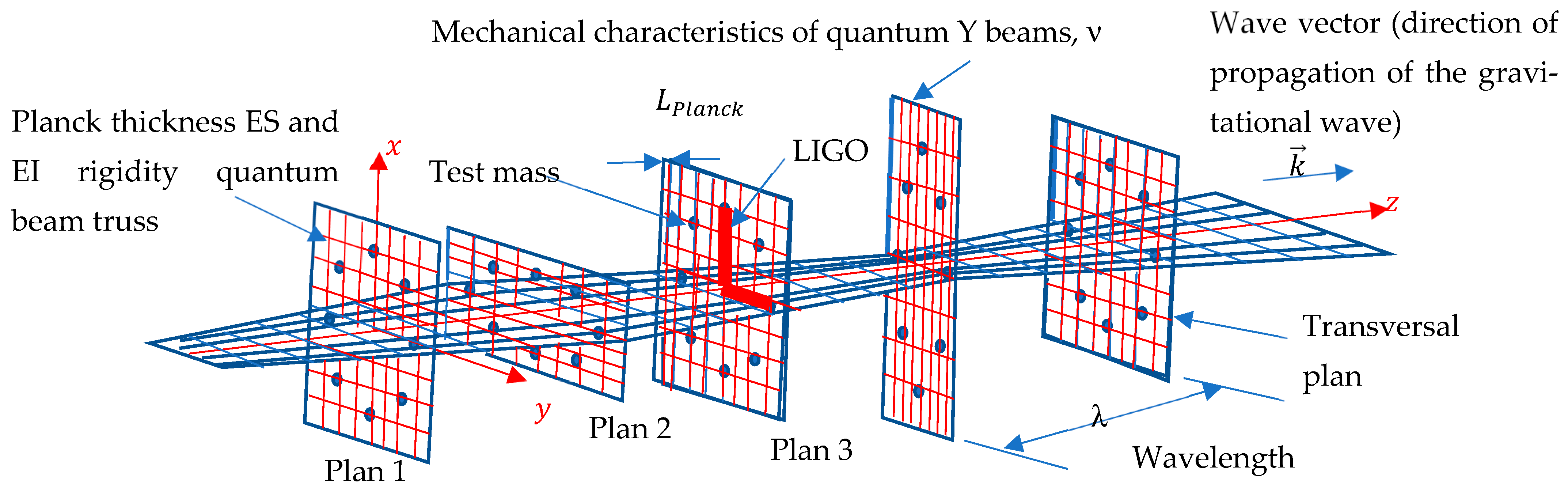

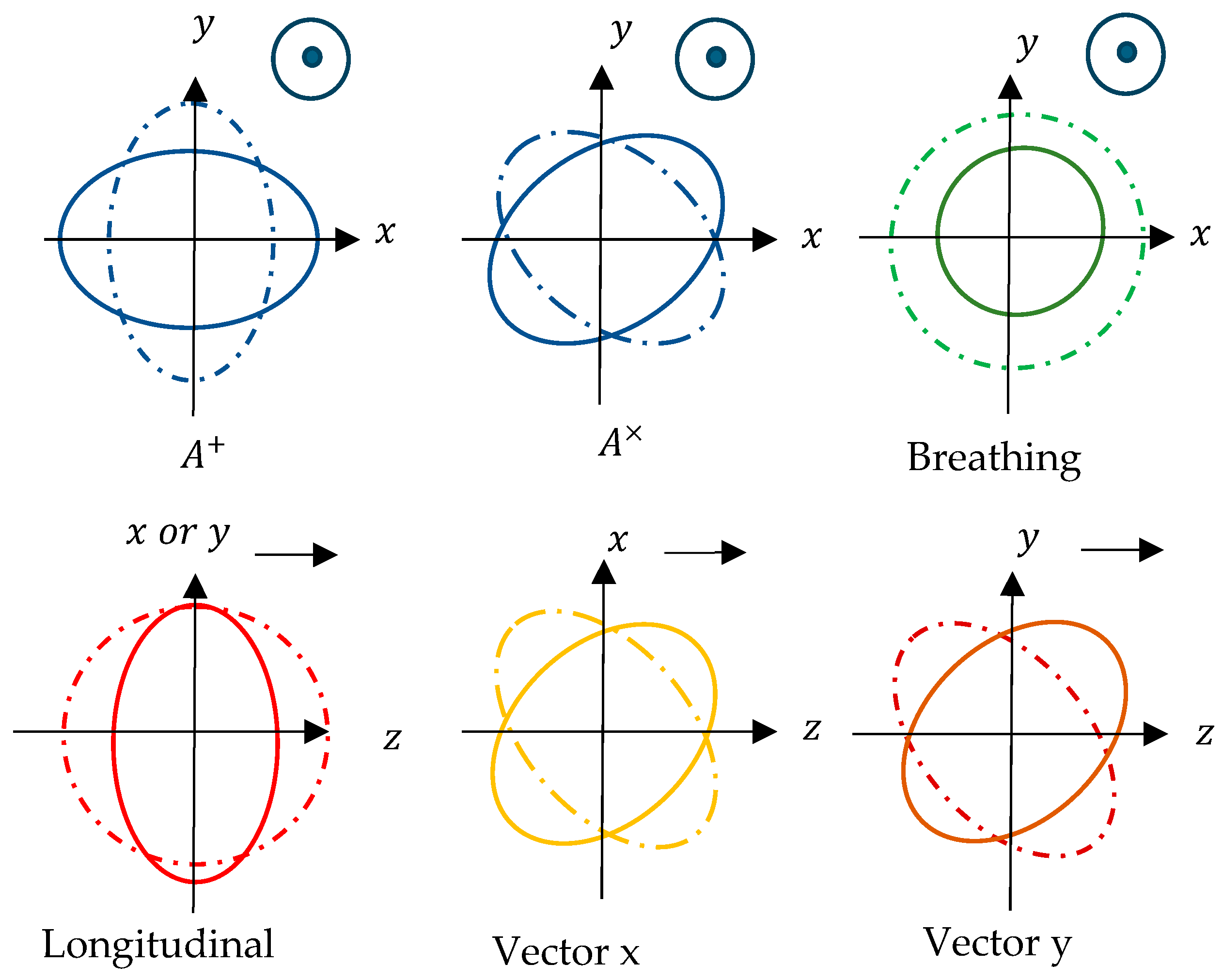

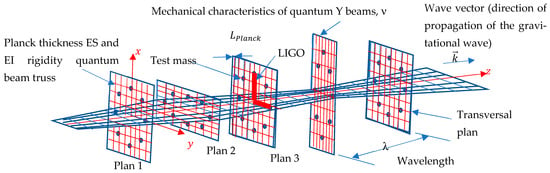

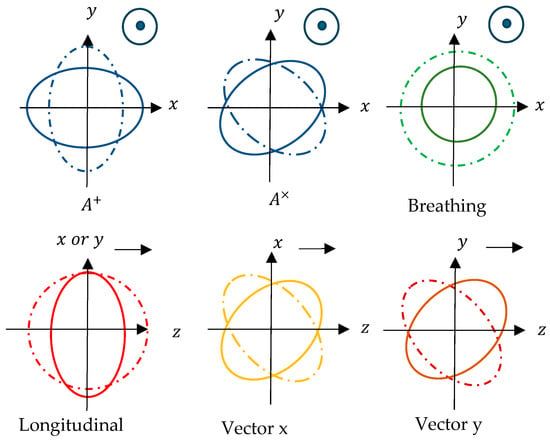

The parallelism between each of the components of the perturbation tensor of the weak-field metric and the deformation tensor of elastic space-time in four dimensions is detailed component by component in the publication [28]. Each of the components is identified with confirmed experiments of general relativity (Lense–Thirring effect [6,65], gravitational waves [10,11], gravitational lensing effect [7,8]). But we also see in this publication that certain physical phenomena or complementary polarizations associated in particular with the direction of propagation of the plane wave and about the components (see Figure 2; , (see Formula (21)) remain to be discovered [28].

Figure 2.

Lattice model (quantum beam) of space in case of gravitational wave perturbation (deformation h = 2ε) in several successive transverse planes—view of the foliated space associated with GW.

The parallelism of the equations of non-linearized general relativity (16a), then linearized (16b), then the elastic model with the equivalent generalized Hooke’s law (17) is given here in a tensor mathematical way, which is valid regardless of the frame of reference considered below, with E Young’s modulus, v Poisson’s ratio of the equivalent elastic material, the elastic strain energy,the strain tensor, and the Kronecker symbol:

In an isotropic transverse plane, the generalized Hooke law is applicable [98]:

We can see clearly that , and , equivalent to Hooke’s law.

Noted that in the vacuum, (no loading of the space-time). We must then add a tensor related to the energy of the vacuum deformation, to keep the complete model with Hooke’s law. This is explained in [27,28].

Various measurements of strains and angular distortions of space-time [28] (gravitational lensing effect, Lense–Thirring effect), space (gravitational waves), and time (Shapiro effect) have allowed us to be certain that Einstein is right (see Table 1). Space-time is a physical, deformable elastic object subject to strain. Space must be associated with time to constitute space-time. This space-time is not infinitely rigid and absolute, but deformable (very little in fact); this is how the constant κ = 2.0766 × 10−43 N−1 translates. This order of magnitude is also reached in publication [92].

Another way to see how space is rigid is to consider the order of magnitude of Young’s modulus (1020 × R. Weiss [22,75]) or the order of magnitude of the strain created by gravitational wave 10−21! Space-time is elastic and malleable, a kind of “deformable elastic quantified elastic medium” as Thibault Damour calls it in his lectures (e.g., on gravitational waves, Banyuls-sur-Mer: explanation of the old and new ether during the question session. 2017 1:03:14–1:05:37) or in his books [30,31]. The elastic aspect, i.e., its ability to return to its initial shape after loading without residual deformation, was validated by measurements of the deviation of the positioning of stars during a solar eclipse in 1919 by A. Eddington [5]. The light manifesting the position of the stars shifted under the distortion of space-time in the presence of the Sun, and then the stars returned to their initial position when the Sun left. Space-time did have an elastic response. There is no residual deformation once the “load” is removed. In structural engineering, this corresponds to the serviceability limit state, as opposed to the effect of a black hole, which corresponds to the achievement of the ultimate step of ruin of space-time, i.e., in the engineering of structures in the ultimate limit state. Space-time, subjected to a moderate load, behaves like a kind of “deformable quantized elastic medium” [29,30,31], as described by A. Sakharov. This “normal or current” load level of the space-time corresponds to the serviceability limit states in structural engineering that remain in the elastic regime in this case. We will therefore call the elastic medium that behaves like space-time “elasther”, represented in Figure 1 so as not to leave any confusion.

In the context of this model, we can therefore take the expression of proper time and transpose it into an elastic deformation of a new elastic equivalent Sakharov medium, which is deformable.

We then obtain the expression of proper time in terms of equivalent elastic deformation associated with the fourth dimension of space-time within the framework of the model of the equivalent elastic medium, as demonstrated by T. Tenev and M.F. Horstemeyer in [19,20]:

This leads to a missed period of time of their own with :

In the context of this model, everything happens considering that we had in the “elasther” a super-elastic material with four dimensions, and one of the variations in geometric dimensions, the depends directly on the variations in time. Time is thus found in the “mechanized” model. We will see later the fundamental consequences of this point for dark energy and dark matter if we push the model of the elastic medium of this “deformable elastic quantified elastic medium” [29,30,31] to the end.

Thus, many theorists try either to develop four-dimensional mechanics of continuous media from the mechanics of three-dimensional continuous media, or to start from general relativity and transform it into mechanics of continuous media in four dimensions. We are following the second approach in this paper.

Another way to see these four dimensions is to note the non-static nature of space-time on the one hand and to take into account the limit speed c of transport of deformations within it on the other hand. Thus, when an observer makes a measurement of deformation (elongation or shortening, angular variation) at a point in space-time, there are certainly the deformations that they measure in their own time instantaneously where they are, but there are also, in a way, complementary deformations in the process of arriving, given that nothing can go faster than the speed of light. In a model of elastic mechanical deformation, in a chosen reference frame, it takes time for the deformation to move from one location in the simulated space-time to another. It should be emphasized that the elastic model is merely an analogy, arising from the similarity between the formulas of general relativity and those of a mechanical elastic medium. Therefore, the phrase “the speed of time propagation” makes sense in such a model. It is not instantaneous. If the Sun disappeared, it would take 8.20 min for us to realize on Earth the change in deformation associated with this disappearance where the Earth is positioned in relation to the Sun. The final measurement will therefore take into account the instantaneous deformations and the delayed deformations of the “elasther”. This is why in all measurements of deformations of space-time in general, the final deformations are greater than those alone predicted by Newton (e.g., the angle of shift of light rays by the Sun predicted and measured in general relativity is twice as large as that predicted by Newtonian calculation alone). So, the deformation measurements must be made in four dimensions, i.e., taking into account those related to space but also those due to time. In the “elasther” model, time implies deformations complementary to that of space and therefore space-time must be considered in any elastic model.

It is important to note that the elastic tensor added to the Einstein field equations in our model is defined covariantly (see Appendix A), ensuring that the Lorentz invariance and general covariance of the theory are strictly preserved. No preferred frame is introduced; the elastic coefficients act as scalar or rank-2 tensors under coordinate transformations, maintaining full symmetry consistency with GR.

4.1.2. Experimental Validation for the Elastic Behaviour

At this point, the reader is entitled to ask, what are the experimental validations of this elastic model that behaves like space-time? There are three of them:

- As we have seen, each of the components of the perturbation tensor of the metric corresponds in nature (position and type) to that of the associated deformation tensor of the “elasther” . When it is elongation and shortening (e.g., the gravitational waves measured by laser interferometers on 11 February 2016 GW150914 [10] or GW170817 [11]), it is indeed elongation and shortening, so the space components in the strain tensor have a magnitude of 10−21. Similarly, when angular distortions are involved (e.g., the Lense–Thirring effect [65] measured via gravity probe B gyroscopes in 2011 [6]), the same angular distortions are measured in the strain tensor (see (20), (21)). The time component is associated with isotropic compression in all directions of Newtonian gravitation.

In summary, these observations demonstrate that the relation holds both physically and mathematically, as is explained and demonstrated in detail in the publication of D. Izabel, Y. Remond, and M.L Ruggiero [28]. We can see in (20) that each component of the perturbation tensor is associated with a general relativity experiment (e.g., is associated with gravitational waves in space). We can see also that the components with “?” are unknown today.

- Any elastic medium, when dynamically stressed, presents elastic compression waves whose velocity is and shear with Y Young’s modulus, μ the shear modulus sometimes noted as G in engineer calculations, and ρ the density of the medium. Gravitational waves, being transverse waves, correspond to the elastic space-time medium dynamically solicited in an extreme way given the extremely high rigidity of its structure (1/κ) [25,30]. The elastic model explains why the speed of light is what it is: it corresponds in a way to the ability of photons to penetrate the elastic medium constituting the “elasther”. At speed c, a screen effect of sorts prevents you from exceeding 299,792,458 m/s whatever happens. To draw a parallel, it is a bit like a bullet fired into a pile of sand and which loses its power of penetration at a certain speed, an impassable limit, due in particular to the frictional forces exerted by the grains of sand throughout its course and to the effect of the bullet tip screen by the compressed grains. This is detailed in [19,20,25,27].

- General relativity in a vacuum implies, as we have seen, gravitational waves. They are manifested only by two polarizations, and . Why physically two polarizations and not more? The equivalent elastic medium provides an elegant response. Indeed, physically, the gravitational waves measured to date are generated by two black holes, neutron stars, or mixed systems rotating relative to each other. In short, these two objects mechanically twist space-time. In the mechanics of continuous media, the tensor of deformations and therefore of stresses takes one of two forms depending on the orientation of the facets considered, which are at 45° of each other. The first corresponds to pure tension–compression, i.e., elongation or shortening according to Hooke’s first law, and the second to pure shear, i.e., angular distortion according to Hooke’s second law. The two polarizations A+ and Ax are also 45° apart. And the polarizations measured to date by the LIGO/VIRGO/KAGRA interferometers are indeed elongations and shortenings. It works! The model of the elastic medium reproduces well and explains the physics of gravitational waves, Lense–Thirring effects, and classical gravitation observed today.

Therefore, general relativity implies in our elastic model a bending curvature of quantum beams in the case of Newtonian gravitation or Lense-thirring effect, as well as normal and shear stress in the case of gravitational waves.

4.1.3. Predictive Power of the Model

Does the model possess predictive power regarding new phenomena? Indeed, it offers testable predictions through three principal avenues:

- The first one we have just seen is angular distortions related to shear stresses, so potentially interferometers have their arms moving laterally. Having exchanged with Rainer Weiss (2017 Nobel Prize in Physics) on this subject in 2020, I can state that they are not designed to measure these potential lateral motions. On the other hand, the future LISA interferometer will (see [27]);

- The second point is the analysis of the components of the perturbation tensor of the metric ; there remain the components to be associated with a new physical phenomenon in the propagation direction (z) (see [28]);

- The third point is that space-time appears in our model as layered and isotropic transverse when we analyze the deformations generated by gravitational waves calculated and measured according to traditional general relativity in weak fields [27]. To reconstitute a cohesive medium, and thus reassemble these sheets of space and bring them together, or what amounts to the same but with possible deformations in the direction of propagation of gravitational waves, it is necessary to add geometric torsion to the Riemann tensor (whose mirror is the theory of defects in crystallography with plasticity, by M. L. Ruggiero and A. Tartaglia [44,45]), [91] and this generates complementary polarizations in the z direction. These potential new polarizations, if they exist, will be measured by LISA (see [27]).

At this point, we can be confident about this elastic model of space-time to represent the real behavior of space and time in a weak field when loaded in an elastic regime that is pushed to its limits (thermal aspect, creep aspect, elastic yield stress), a model that can be used to teach us about physics and these contemporary mysteries. This is what I will explore in the next paragraphs, by studying other mechanical properties of all elastic media, and, in particular, the expansion coefficient α and creep coefficient φ.

4.2. Hypothesis of Temperature-Sensitive Space-Time According to Hawking Radiation to Temperature-Sensitive Elastic Time

4.2.1. Elastic Model and Theory

When a massive giant star explodes, it generates, if its mass exceeds a certain threshold, such a localized density of energy that space-time is overloaded or locally plasticized, meaning it collapses. It is compressed and twisted so intensely that it generates a black hole. In their article [50], J.P. Luminet explains, “The black hole must be understood not as a mass that attracts with an irresistible force, but as an extreme distortion of space-time”. Gravitational waves have shown that mergers of black holes (GW150914) [10] or neutron stars (GW1701817) [11] do exist. The shadow of a black hole has been observed twice thanks to the global Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration: that of our galaxy Sagittarius A* on 12 May 2022 and that of the galaxy M87* on 10 April 2019. In short, today, there is no longer any doubt about the existence of black holes, which are intensely distorted space-time.

However, black holes contain a central singularity, necessitating the incorporation of quantum mechanics alongside general relativity for a complete description. This is what Stephen Hawking did in [51,52,53,54]. He discovered that black holes, and therefore intensely twisted space-time, emit radiation, that they have a temperature and end up evaporating in the very long term. However, a black hole is above all space and time, intensely distorted, as explained by J.P. Luminet [50]. The implacable consequence of having assembled space with time is therefore that not only is space sensitive to temperature, but within the framework of the model under consideration, time can also presumably depend on temperature, as envisaged in the publications of U. Lucia and G. Grisolia [55] and A. Chatterjee and G. Lannacchione [56]; we will return to this. The radiation discovered by Hawking is written with the Boltzmann constant :

This radiation from black holes has not yet been directly measured, but hydrodynamic–acoustic analogies have indeed highlighted this phenomenon S.S. Dave [57].

In [55,56], by studying the variation in entropy [62], they then introduce a function τ related to the frequency ν of a physical system serving as a clock, in accordance with A. Einstein’s idea. This time, this clock depends on the temperature T, Planck’s constant h, and Boltzmann’s constant . They get

In the case of blackbody radiation, the variation in the time flow t as a function of the temperature T can then be written as

According to Table 1 of [55], the effect remains extremely small: for example, for T = 106 K (mean temperature of the cosmic web [70]) and n = 1, the temporal variation is in the order of 4.8 × 10−17 s. Although very small, this value is of the same order of magnitude as the space-time strain amplitude observed for gravitational waves (typically around 10−21), suggesting that such thermal effects on time, while subtle, may still be physically meaningful and potentially measurable in extreme astrophysical environments.

By inverting the expression and relating it to time t, we obtain a term that plays the role of a coefficient of thermal expansion of time:

By identification, it becomes

where has the dimension of a time-dependent coefficient of thermal expansion (K−1).

Thus, time appears to be influenced at the quantum level by the temperature T, the fundamental constants h, and therefore by the entropy of the medium S. In this sense, time is quantified in multiples of nh.

This result can be reconciled with what we have seen in Section 4.1 in the case of the “elasther”. Indeed, all elastic bodies are sensitive to temperature and have an expansion coefficient associated with this material. So, if space-time behaves in modeling like a quantized medium, then like any elastic medium, it is sensitive to temperature and expands, contracts, and curves under the effect of a temperature gradient. So, when starting from modeling physics by equivalence, time then becomes sensitive to temperature. This is quite logical since already, thanks to special relativity, we know that it lengthens when we approach the speed of light.

If we postulate that the model of the elastic medium continues to apply under temperature as it applies without temperature, then the strain in the “elasther” must be sensitive to temperature and become Based on the principle of equivalence between the elastic model and space-time in weak fields being bijective and having to work in the model direction towards relativistic physics, then time must be effectively sensitive to temperature, as explicitly envisaged in publications [55,56], and as implicitly envisaged by the Hawking radiation of black holes, which are infinitely distorted pure space-time.

The thermal elasticity of time can also be established in the following way as developed in [58] in connection with [55,56] and the Hawking radiation of black holes [51,54]. To do this, we start with the “cosmic fabric” model developed by T. Tenev and M.F. Horstemeyer [19,20], in which the time lapse is related to the speed of propagation of a signal within space-time. The variation in this time lapse is then written as

with

where is the Laplacian of the volumetric deformation, c is the speed of light, κ is Einstein’s constant, and ρ is the matter-energy density.

The term represents a scalar field describing the fractional increase in the volume of a hypersurface of the fabric:

and the usual strain tensor is

Thus, time depends on a volume variation dV related to the energy-stress tensor, which acts as a tension on the elastic medium:

When modeling with a classical elastic medium, this volume variation can also originate from a temperature rise related to a temperature gradient ΔT and a coefficient of thermal expansion :

Finally, when transposed to time, this relationship is expressed as a ratio between the length of the spatial fabric (in which the speed of light plays an intrinsic role) and thermal expansion:

This expression is demonstrated by D. Izabel [58] and shows how time should vary as a function of temperature if we believe the model of the equivalent elastic medium in a weak gravitational field. Of course, all articles related to a possible variation in time as a function of temperature [55,56,58,59,60,61,62,63] remain for the moment theoretical as long as a real measurement experiment has not been carried out to confirm or refute this prediction. So, we treat thermal time not as a metaphor but as a hypothesis: that the proper time interval is modulated by local entropy gradients, as suggested by Hawking radiation and thermodynamic models [55,56,57,58]. This effect is expected to be measurable in environments with extreme temperature gradients, such as near black holes or in the early universe.

4.2.2. Experimental Validation for the Time Aspects

An experiment consisting of comparing two identical clocks [60,63], one at room temperature and the other subjected to a heated environment, could reveal a temporal drift. However, this drift would probably be due to thermal effects on the clock components, and not to a change in universal time. To test the hypothesis of a fundamental link between temperature and temporality, it would be necessary to design an experiment capable of isolating time as an independent physical quantity, eliminating all instrumental influence. This could involve the study of quantum or cosmological phenomena where temperature plays a dynamic role in the very structure of space-time.

4.3. Hypothesis of an Elastic Space-Time Sensitive to Creep and Consequences on Time

4.3.1. Elastic Model and Theory

When extending the elastic medium model to weak-field space-time, we note that any viscoelastic medium is also subject to creep effects i.e., to amplifications of deformations in time under constant loading. This approach to space-time that can flow has been studied by D. Izabel in [64]. In this publication, I show for the first time, as a logical consequence of all that we have seen so far, that time within the framework of the model of the elastic medium could flow if the model still applies.

In the model with an elastic medium, space-time is thought of as a fabric that includes both space and time [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. To introduce the idea of time creep, we need to relate the potential time drift to the time elasticity in general relativity. In a weak field, we have [19,20]

Proper time is then written with the interval convention (+−−−):

Or in a different way:

Compare that with the usual expression of general relativity:

where we see that .

By identification, we obtain

Hence, the temporal distortion is

By introducing the creep effect, modeled by an increase in the gravitational factor of G according to as carried out in [64], we have

The creep coefficient φ can be isolated:

Let us also have

This relationship that links temporal drift to a creep effect was published in [64].

Creep is modeled as a time-dependent deformation of space-time under constant stress energy loading. Its effect on galactic dynamics is quantified via a creep coefficient φ derived from MOND-like behavior [64]. This hypothesis must be tested against gravitational lensing data and rotation curves of stars in galaxies.

On the hypothesis of time creep and its compatibility with general relativity, the concept of time creep introduced in this work is not intended to contradict the equivalence principle of general relativity, but rather to extend the analogy of space-time as a deformable medium into the domain of long-term dynamical behavior. In classical mechanics, creep refers to the time-dependent deformation of materials under constant stress, typically linked to molecular rearrangements. In our framework, space-time is modeled as a structured elastic vacuum—termed elasther—whose deformation energy evolves under sustained gravitational loading. The proposed creep coefficient φ is not derived from atomic physics, but from a continuum-level interpretation of observed gravitational anomalies, such as galactic rotation curves and lensing effects, without invoking dark matter. This approach remains consistent with the weak-field approximation and preserves general covariance by introducing a supplementary elastic tensor coupled with the Einstein tensor. Indeed, this creep effect is introduced in the constant κ, which does not change the covariance principle. While speculative, this hypothesis is grounded in measurable strain effects and offers falsifiable predictions, such as a potential drift in Shapiro delay over cosmological timescales. We acknowledge the limits of the analogy and explicitly state that the model does not apply in strong-field regimes or replace the geometric foundations of general relativity but rather complements them with a mechanical interpretation of space-time dynamics. The paper [64] details this approach.

4.3.2. Experimental Validation for the Creep Aspects

Again, only a measurement of the variation in time by the creep effect of space-time will be able to confirm or inform this prediction. To do this, it would be necessary to reproduce a Shapiro-type measurement [9] over time to see if there is indeed a deviation in the measurement of the effect of gravitation related to time, with all other parameters being kept fixed elsewhere.

Unlike the creep of terrestrial materials, which occurs on scales of hours or years, the creep of space-time would occur on cosmological scales in the order of a billion years, consistent with the characteristic times of galactic evolution.

4.4. Plasticity of the Elastic Medium and Infinite Stretching of Time

Until now, we have been interested in deformations in weak gravitational fields, which are already partly covered by Newtonian gravitation, but general relativity aims, and this is its whole interest, at gravitation in strong fields such as neutron stars or black holes. In this case, it is well known that space-time at the level of these singularities is intensely distorted until it breaks, giving rise to the singularity. The mirror effect of this in the case of the elastic medium model is plasticization. The fibers that make up the fabric of space-time plasticize and stretch until they break. If space-time can be modeled as an elastoplastic crystal as the authors do in [47,48,49], then the small quantum beams constituting the equivalent crystal lattice [19,20,25,28] are subject to plastic hinge joints and the crystal collapses. The answer for time in this elastic–plastic model is then the plastic bearing of the material in the law of stresses on the -axis and strain on the -axis. Time stretches infinitely within a black hole like plasticized fibers that leave Hooke’s law; i.e., we enter the realm of plastic irreversible deformations.

It is interesting to note that the loading ratio between the bi-triangular stress diagram used for beams and the bi-rectangular diagram in plasticity ranges from 1.5 to 2. This ratio also corresponds to the difference in space-time loading when comparing the mass of a neutron star (1.4 at 2 solar mass)—at the limit of the elastic domain—with the mass required to form a black hole (2.5 at 3 solar mass), which can be interpreted as the plasticization threshold of space-time.

It is important to emphasize that extending the elastic analogy to the regime of strong gravitational fields—such as those encountered near black hole singularities—goes beyond the strict framework of the formal correspondence established in the weak-field limit. This extrapolation is based on the speculative hypothesis that the underlying quantum structure of space-time could exhibit elastoplastic-like behavior, even under extreme conditions. While this approach offers a suggestive mechanical picture of spatio-temporal deformation, it is not currently grounded in a direct mathematical correspondence with non-linear general relativity. It should therefore be considered a heuristic extension of the analogy, whose physical relevance must be evaluated through future tests.

4.5. Space-Time Lamination and Time Lapse in the Case of Gravitational Waves—Einstein–Cartan Modified Theory of General Relativity

In his publication [38], A. Einstein showed that in the case of general relativity in a weak field, gravitational waves are transverse plane waves generating deformations in planes perpendicular to the direction of propagation (Figure 2). In the publication [27], D. Izabel, Y. Remond, and M.L Ruggiero study these deformations from the point of view of an elastic isotopic transverse model. These works are based on Izabel’s Thesis [98]. It emerges that space appears when following this model as laminated or a kind of multi-sandwich with deformations localized in these transverse planes, where space has a behavior corresponding to a particular elastic medium made up of a stack of sheets of equivalent elastic materials without any coherence between them. Based on [98] and Formula (14b), Poisson’s ratio of such an anisotropic medium is equal to = 1 (see GW strains). Young’s modulus for space is in the transverse planes; in the propagation direction, it is small but unknown due to a lack of experimentation for this component, as detailed in [28]. For the time component, , as shown by [19,20,98]. Then, space and therefore space-time become through modeling an anisotropic elastic medium, i.e., isotropic transverse (see Figure 2). To reconstruct a coherent medium, the authors show in [27] that it is necessary to use general relativity with geometric torsion, i.e., to add a complementary term called the torsion tensor to the traditional Riemann tensor. In this model, the time interval intervenes to transmit information from one sheet of space to another, as detailed in [27], via an equivalence with the burger vector in crystallography in defect theory [44,45,91].

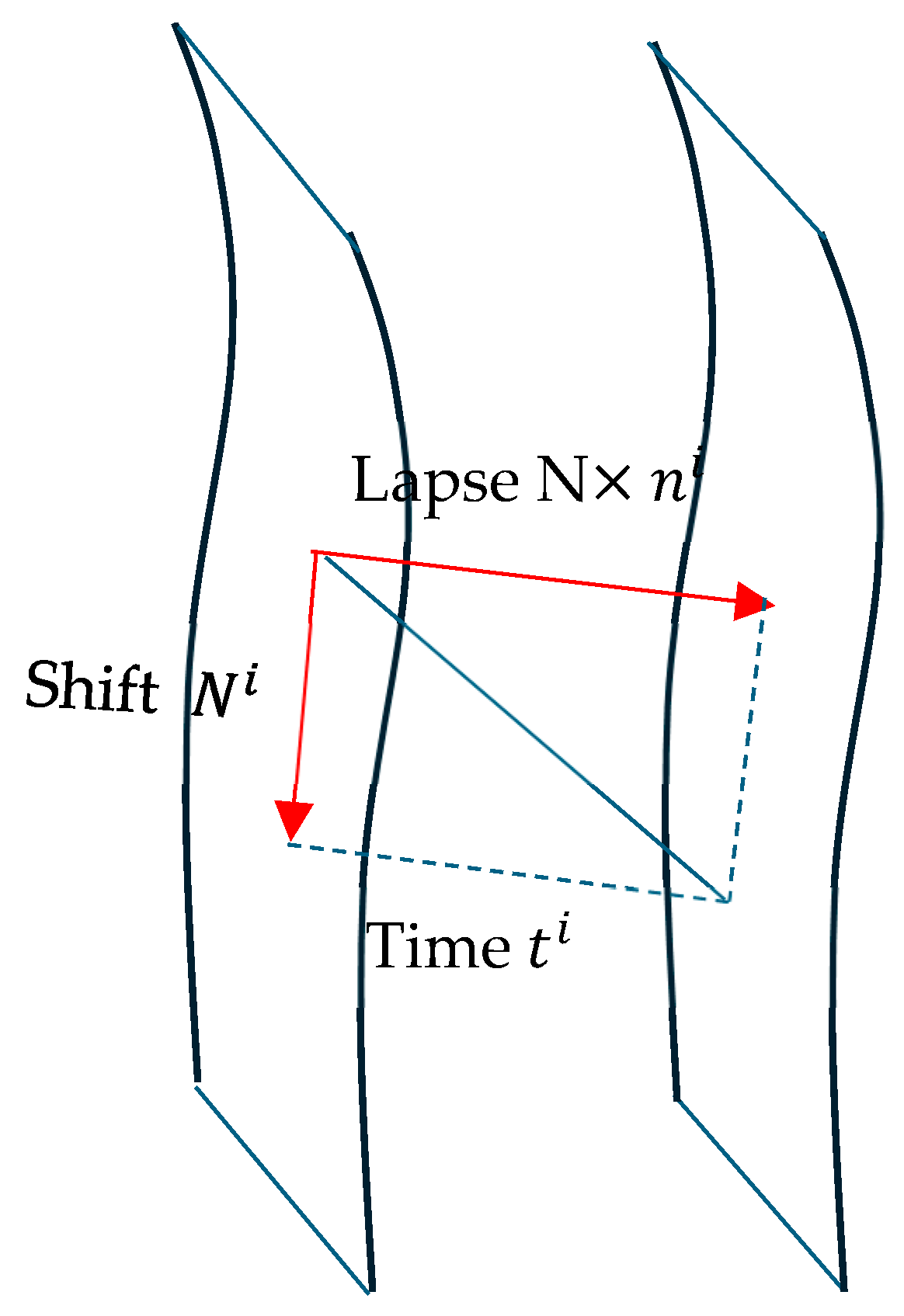

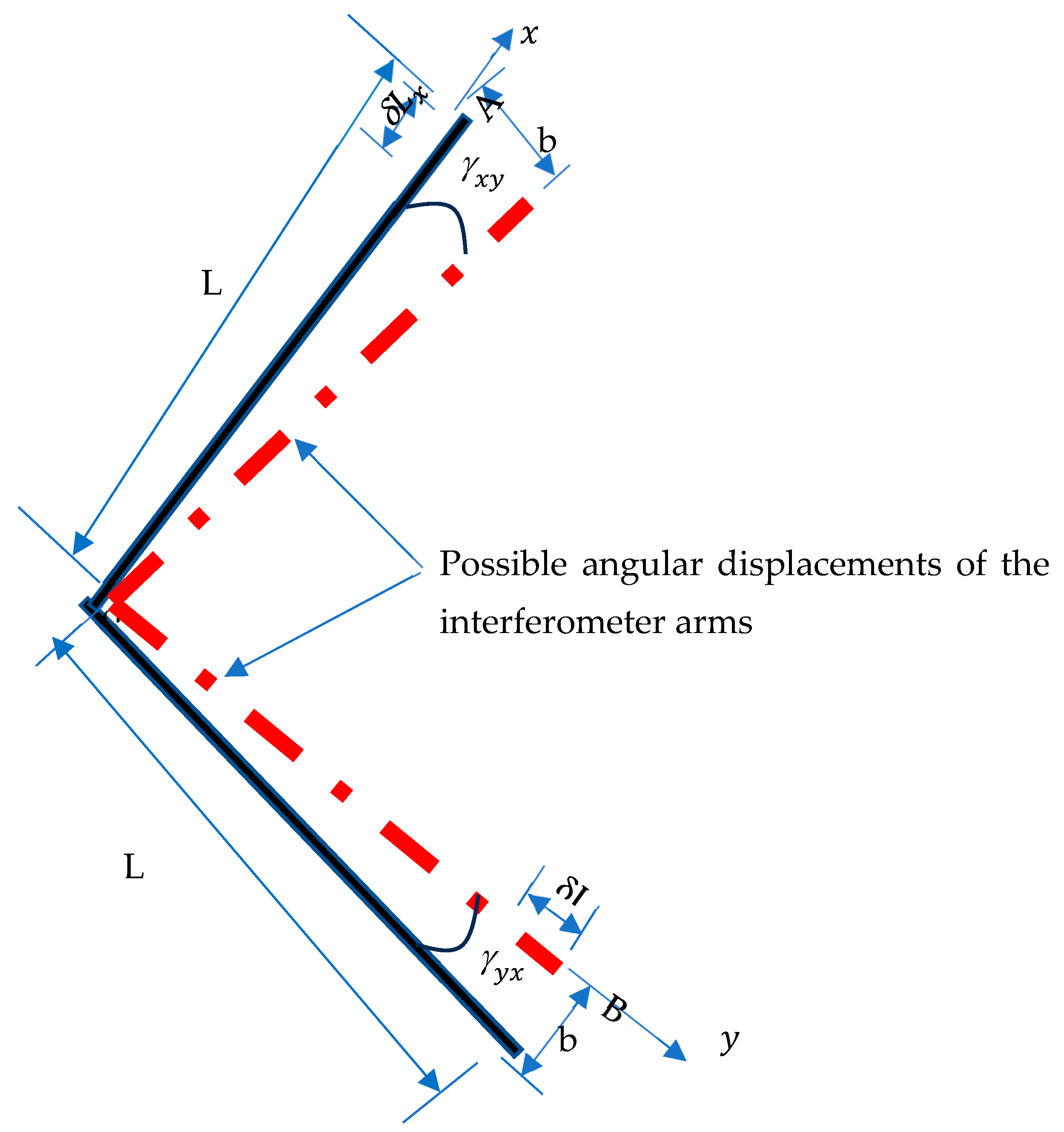

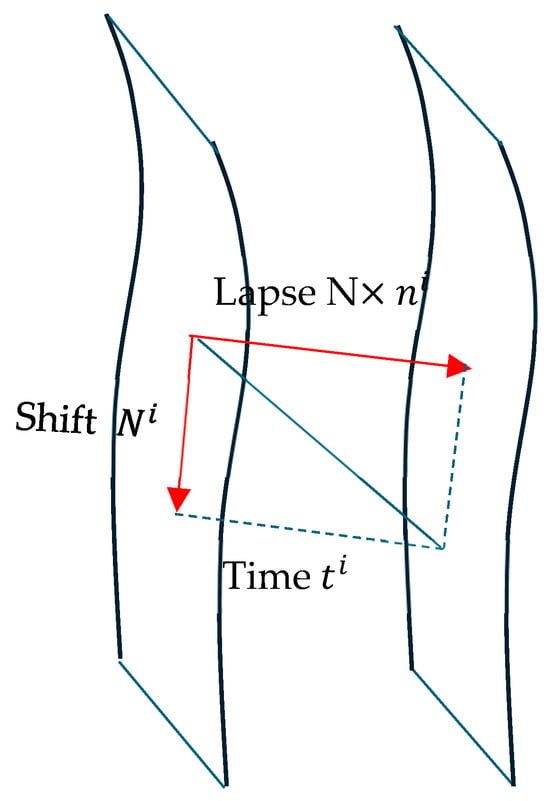

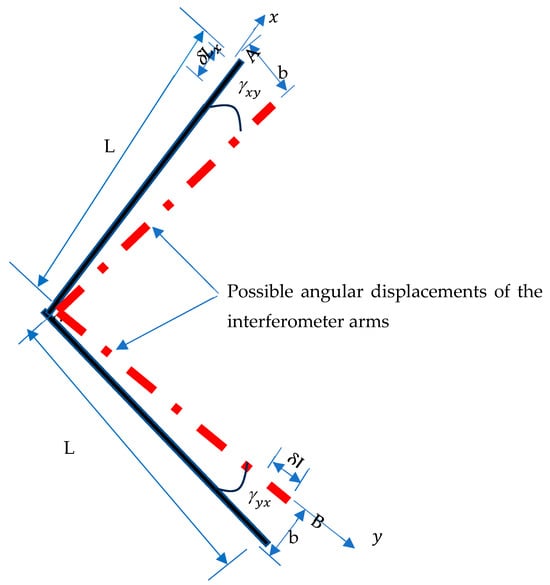

In [69], by R. Arnowitt, S. Deser, and C.W. Misner (ADM), space-time is divided into a family of spatial hypersurfaces , parameterized by a time of coordinate t. Each is a three-dimensional hypersurface, provided with a spatial metric , based on which the initial data is defined. To describe the transition from to , [69] introduces two gauge functions (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Illustration of the ADM structure of space-time.

- The lapse , which measures the normal proper time interval at between two hypersurfaces;

- The shift , which describes the spatial shift of points from one hypersurface to another.

The spatio-temporal metric then takes the following form:

Moving on to Hamiltonian formalism, ADM [69] chooses t as the evolution parameter and defines for each hypersurface the canonical variables (), where is conjugated to . Two types of constraints appear:

- Hamiltonian stress H ≈ 0, which generates the normal evolution at the surface (via lapse);

- ≈ 0 moment constraints, which describe tangent rearrangements (via shift).

Time then becomes a generator of transformations, and the total Hamiltonian is written as

Thus, choosing a lapse function N is equivalent to fixing the way in which time flows from one hypersurface to another, while the shift adjusts the spatial coordinate system.

The interpretation of time that results from this is twofold:

- There is a relativity of time: no absolute time, but a plurality of internal “clocks” depending on the choices of lapse and shift.

- Time is dynamic: it corresponds to the successive sliding of spatial hypersurfaces, which reflects the evolution of the gravitational metric.

In summary, the ADM formulation [69] describes time as a foliation parameter of space-time, defined by gauge functions (lapse and shift) and integrated into a Hamiltonian formalism, where it becomes the generator of dynamic evolution. This vision is in line with both our elastic model (transmission of deformations from one leaf to another) and the foliation of space-time revealed by gravitational waves [27] or hypersurfaces developed by T. Tenev and M.F. Horstemeyer in [19,20].

This ADM method is widely used in numerical general relativity and allows us to faithfully reproduce the behavior of the observed space-time.

Important warning: While both the ADM formalism and wave propagation involve transverse structures, it is crucial to distinguish their fundamental geometric natures:

- ADM formalism: Space-time is decomposed into complete 3D spatial hypersurfaces, orthogonal to a time-like direction. The foliation represents a mathematical separation of space and time.

- [Full 3D spatial sheet at t = 1]

- [Full 3D spatial sheet at t = 2] ← Time ⊥ sheets (time-like)

- [Full 3D spatial sheet at t = 3]

- Wave propagation: Electromagnetic and gravitational waves propagate along light-like directions, with oscillations confined to 2D transverse planes perpendicular to the propagation direction.

- → → → Propagation direction (light-like)

- | | |

- | | | ← 2D transverse wave surfaces ⊥ propagation of the wave

- | | |

What unites these physically distinct structures is a common constraint of transversality:

- ADM: The Hamiltonian constraint ∇ⱼπⁱʲ = 0 imposes transversality in phase space.

- Waves: The physical oscillations are strictly transverse to the propagation direction.

This paper explores whether that shared transversality, despite geometric differences (2D sheets in gravitational waves, 3D sheets in ADM), could reveal a fundamental foliated architecture of space-time where both mathematical and physical constraints emerge from a common underlying structure. A common objection to the physical interpretation of the ADM foliation is that it appears to break diffeomorphism invariance, a fundamental principle of general relativity. This objection is resolved if the foliation is understood as an intrinsic geometric structure rather than an arbitrary coordinate choice. Gerhardt’s [66] and Pawłowski, and all [89] work on CMC foliations shows precisely that, under reasonable physical conditions (global hyperbolicity, timelike convergence), a regular and unique foliation emerges naturally, without violating covariance. In this framework, the time function is not a gauge choice but a geometric quantity determined by the mean curvature of the hypersurfaces. Thus, the foliation does not break diffeomorphism invariance; it reveals a preexisting structure of spacetime, consistent with the principle of covariance. This approach aligns with that of “Shape Dynamics” proposed by Barbour & Foster (2008) [86], where the foliation arises from a spontaneous symmetry breaking that preserves fundamental invariance.

In the case of light, the solutions are plane waves of velocity c, with E⊥B⊥k polarization and interferometry experiments have confirmed this structure. The electric and magnetic fields develop perpendicular to the direction of propagation of the electromagnetic wave like the gravitational wave.

5. Discussion

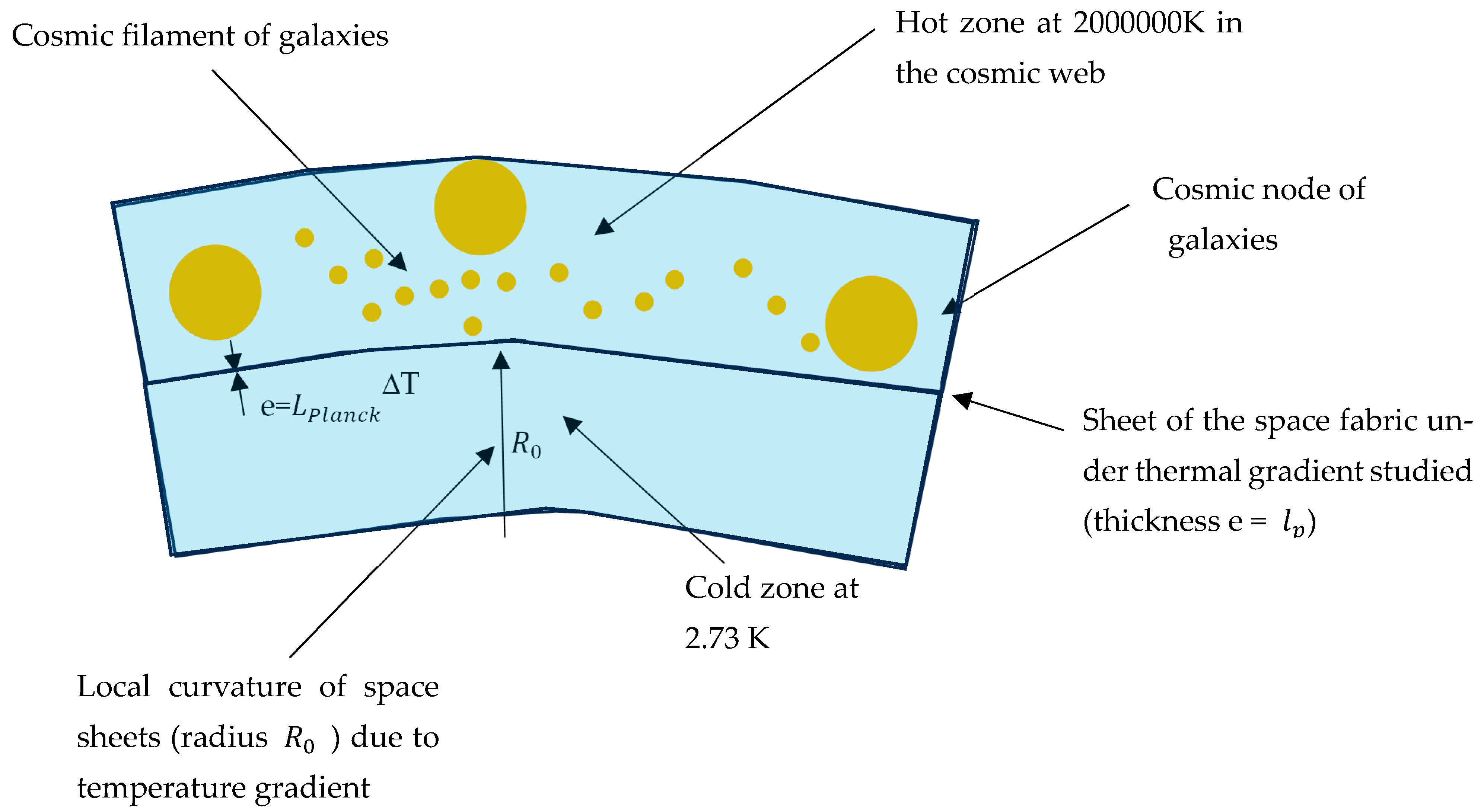

5.1. Consequence of a Variation in Time and Space as a Function of Temperature

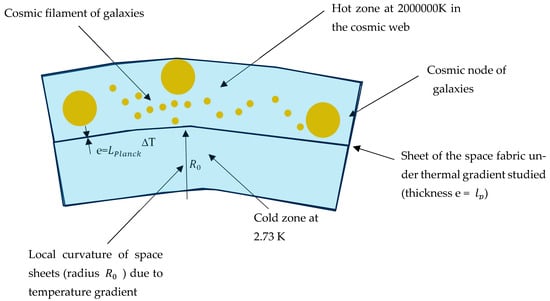

We have seen, whether it is through Hawking radiation [51,52,53,54] or in publications [55,56,58,59,60,61,62,63], that time, in the context of a four-dimensional elastic medium, can be sensitive to temperature since it becomes associated with a deformation of an equivalent elastic medium that can be dilated (the “elasther”, i.e., the “deformable elastic quantified elastic medium” (T. Damour [29,30,31]); the cosmic crystal [47,48,49]). In these same publications, based on physics experiments, D. Izabel [58] shows that naturally space is also sensitive to temperature that gives a strain . As a result, space-time is sensitive to temperature, and therefore, temperature gradients within space-time, if they exist, can, according to the model of the “elastic space-time quantified elastic medium” [29,30,31], generate a thermal curvature of it. Thus, a thermal gradient between the cosmic web and the vacuum applied to Planck thickness sheets of thermal conductivity of vacuum λ = 0 W/m2.K, which would constitute it [19,20,27,69], would bend space-time in the opposite direction of gravitation, giving us the illusion of a mysterious dark energy. This is therefore equivalent to placing the cosmological constant Λ on the left side of Einstein’s equation, that is, on the curvature side and not on the right on the dark energy side (46). The following two equations show the parallel between the one-dimensional elastic beam model and Einstein’s four-dimensional equation. In summary, what can create curvature in space-time is not only the density of mass energy but also a temperature gradient applied between two faces of a laminated insulating medium [19,20,27,69], as taken into account in structural engineering and as envisaged in the ADM model [69].

In structural engineering, 1/R2 expresses the bending curvature squared (1/m2), R (m) the radius of curvature of the beam, I its inertia (, L its span in meters, U (N.m) the different bending energies’ indices M and thermal energy indices ΔT, E its Young’s modulus (N/m2 = Pa), α ( its coefficient of thermal expansion, ΔT the thermal gradient (K), and e its thickness in meters:

In parallel with the expression of general relativity with Λ the cosmological constant,

In the publication [58], D. Izabel has shown that such a process is conceivable and that in the case of space, as in the case of time, we obtain a coefficient of thermal expansion α 1.0 × 10−6 K−1 if we consider a thermal gradient between the cosmic web and the vacuum, as given in the publication [70]. This phenomenon of thermal curvature linked to a thermal gradient would then, within the framework of our elastic model, be an excellent candidate to explain what dark energy is and where dark energy comes from, which would then be, according to the publication [58], only an intrinsic thermal curvature of space-time, and therefore of the space and time of the different leaves that would constitute it, according to the formulation with Λ the cosmological constant:

with e the thickness of the space-time sheet of Planck size, the curvature of the space sheet under the effect of the thermal gradient ΔT, and the coefficient of thermal expansion of the quantified elastic medium [29,30,31], space-time. Figure 4 illustrates this thermal curvature on a space sheet.

Figure 4.

Effect of dark energy replaced by a thermal curvature of space-time.

This effect of thermal curvature and therefore of dark energy may have varied over time since the cosmic web that is the source of the thermal gradient has only evolved since the Big Bang, as shown in the recent publications [73,74].

5.2. Consequence of a Variation in Time and Space by Creep of Space-Time

To explain the stability of stars on the periphery of galaxies that should be ejected due to a lack of gravitation calculated from visible mass alone, physicists, based on Newton’s law, have assumed the existence of a hidden or black mass (Fritz Zwicky 1933 [88]) to amplify the effects of gravitation and hold the various stars in place. The same principle has been considered to explain the increase in gravitational lensing effect, or at the time of the CMB, to explain the small anisotropies in the emission of the cosmic microwave background. The problem is that the hidden mass needed to generate this missing gravitation has remained hopelessly undetected for 70 years despite the colossal deployment of experiments around the world to bring it to light. As a result, some physicists have been led to transform this ontological problem into a legislative solution. Change Newton’s law in a certain regime. And the agreement is excellent. This is the approach developed by M. Milgrom, and which became the MOND theory “Modified Newtonian dynamics” [71,72], but it is performed at the cost of a new constant of unknown origin, = 1.2 × 10−10 m s−2.

The model of the elastic medium allows us to consider a completely different approach. It is not like the MOND theory in modifying Newton’s law, or like Zwicky in adding dark matter, but returns to what we learned from general relativity by using the elastic medium that reproduces the deformations of space-time. Gravitation is not a force linked to masses as I. Newton had envisaged; instead, it is an illusion, a deformation of space and time. So, if there is more gravity needed to keep stars on the periphery of the galaxy—or, in the case of gravitational lensing, or at the time of CMB emission, with all the anisotropies observed at the level of the temperatures of the cosmic microwave background—it is because there are more deformations than the visible mass alone can provide, whatever the origin of this excess deformation. This second part is the key part here. The elastic model then allows us to consider another solution rather than adding mass or changing Newton’s simplified law. Once again, the solution is not external through densities of mass, or energy that loads elastic space-time within it, but within space-time itself. In the intrinsic vacuum structure are our quantum beams, as Einstein taught us to solve Newton’s paradox with its mysterious forces acting at a distance, forces that could not act on light, which has no mass, and which is nevertheless bent by gravitation. This is shown in the publication by D. Izabel [64] based on the well-known knowledge of structural engineering. An increase in deformation can also occur under a constant load if the medium constituting the structure is subject to creep, i.e., a reorganization of the molecules, noting the elastic material under the effect of prolonged loading over time, typical of viscoelastic behavior. The creep of space-time and therefore of time like space can therefore alone explain the physical observations of gravity more intensely than mass producing it without adding missing or black mass. This is the great consequence of the creep of time via and space-time. In the publication by D. Izabel [64], it is thus shown that the MOND law, which works well to explain the stability of stars on the periphery of galaxies, can be reformulated as a creep coefficient of space-time according to the following formulation:

with and which suddenly takes on a mechanical origin.

Figure 5 shows the amplification of space-time deformations by the creep effect.

Figure 5.

Deformation of space-time by creep effect.

This creep effect, and therefore dark matter, may have varied over time depending on the texture of the elastic deformable quantified elastic medium [29,30,31], as shown by the recent publication resulting from the DESI experiment [7].

5.3. Consequence of the Foliation of Space-Time for the Nature of Time in the Case of an Equivalent Elastic Medium

The goal of this whole study is to try to understand what becomes of time in the case of our model of an elastic medium. Like an investigator, we must gather all the clues at our disposal.

- (a)

- First of all, in any elastic medium, the relations between the speed of propagation of the waves and the elastic characteristics of the medium Y, ν, and ρ are written according to [19,20]

However, in the case of space-time, there are gravitational waves predicted by A. Einstein [38] and measured for the first time during the GW150914 event [10].

Moreover, it was shown during the GW170817 event [11] that these waves propagate precisely at the speed of light c, which is, therefore, on the basis of our model and the two formulations above, a key parameter that characterizes the space-time elastic crystal structure [98], the “elasther”.

An important point has to be mentioned here. In our model, space-time is treated as a structured elastic medium—referred to as “elasther”—whose behavior is closer to that of a solid than a fluid. Consequently, the propagation of deformations such as gravitational waves must be described using the elastic wave equations valid for solids. In particular, transverse waves, which are absent in fluids, are permitted in solids and correspond to the shear modes observed in gravitational wave detection. The speed of these waves is governed by the elastic properties of the medium, such as Young’s modulus , Poisson’s ratio , and density , through relations like . While longitudinal wave speeds are often expressed as in solids, the analogy remains heuristic and must be interpreted with caution. It is essential to emphasize that this mechanical analogy does not imply a literal equivalence with classical elasticity theory but rather serves as a conceptual framework to explore the emergent properties of space-time, including the nature of time itself.

- (b)

- Then, according to special relativity, time expands [2].

- (c)

- In general relativity, time can indeed be associated with deformation, and we have seen that this translates into the 00 component of the tensors involved in general relativity [19,20,25,27,28]. And we have seen that time can be expressed from this deformation in the fourth dimension of general relativity, .

- (d)

- In the context of our elastic model, I hypothesize that space-time may exhibit a laminated structure at microscopic scales, potentially composed of thin layers with Planck-scale thickness. This idea does not arise from standard general relativity or gravitational wave theory but is introduced here as a speculative mechanism equating to the GW analysis in [98], to account for the anisotropic deformation patterns observed in our simulations in the case of gravitational waves [27]. While this laminated structure is not experimentally confirmed at this stage (see LISA experiment), it provides a conceptual framework for modeling the transmission of elastic deformations and the emergence of time intervals in a discretized space-time. I emphasize that this remains a hypothesis and does not reflect a consensus in the current literature [19,20,25,27,28].Furthermore, in a recent publication [77], D. Izabel shows that the Bragg law can be extracted from the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), interpreting its power spectrum as an “inverse diffractogram X” of a laminated crystal structure of the early universe. This supports the hypothesis that space-time possesses a quantized internal architecture, consistent with the elastic model proposed here.

- (e)

- Finally, in classical kinematics, the time required for a signal or deformation to travel a given distance is expressed as , where is the propagation speed in the medium. This relation does not define time itself but describes how time intervals emerge from the dynamics of propagation. In the context of our elastic model, we interpret proper time as the result of deformation transmission within a structured medium, where the speed of propagation depends on the elastic properties of the vacuum. This approach does not imply that time “propagates,” but rather that the measurement of time reflects the mechanical response of the medium to stress and curvature.

All these elements put together invite us to postulate that time could also be “mechanized” and defined in the framework of our elastic model as a deformation that propagates over a given distance more or less quickly depending on the characteristics of the environment, its Young’s modulus, its Poisson’s ratio, its density, etc., and would be influenced by the coefficient of creep φ and expansion coefficient α. The overall vision of the elastic paradigm then appears as follows:

- Gravitation curves time [3,4] and slows it down since space-time is bent, so “the deformable elastic quantified elastic medium” [29,30,31] lengthens, thus increasing the travel time of the deformation compared to the initial flat length not deformed before the effect of gravitation.

- Nothing, not even information, can exceed the speed of light since this is a characteristic of elastic space-time [19,20,25,27,28].

- An increase in temperature slows down time since lengths dilate and the travel time to transmit a deformation increases relative to an initial L length [51,52,53,54,55,56,58,59,60,61,62,63].

- The creep of space-time increases gravitation and therefore the curvatures and the distances to be covered to transmit information with respect to an initial length L [64].

- In a black hole, time dilates, until it seems to stop, since the deformation enters the plastic regime and stretches to infinity.

Thus, mathematically, proper time becomes that shown below, following the direction considered, since according to publication [27], space is isotropic transverse:

As a logical consequence of all our reasoning, the mechanical definition of tenses is

Let us use a metaphor to explain these mechanical formulations of time. A human being who has aged over time is characterized, among other things, by the wrinkles on their face. However, these wrinkles or deformation waves depend on the elasticity and density of their skin. These wrinkles are deformities that spread over a given distance, the face, and which are more or less important depending on the elasticity and density of the skin, its curvature, its tensions, its creep with the relaxation of the muscles, and the dilation with temperature. Time emerges through the transfer of deformations, which solicits the elastic medium according to the flexibility and density of the medium.

5.4. Adequacy of the Model with the Symmetry Principle