Abstract

Background: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) progressively impairs motor function, compromising speech and limiting communication. Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) is essential to maintain autonomy, social participation, and quality of life for people with ALS (PALS). This review maps technological developments in AAC, from low-tech tools to advanced brain–computer interface (BCI) systems. Methods: We conducted a scoping review following the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews. PubMed, Web of Science, SciELO, MEDLINE, and CINAHL were screened for studies published up to 31 August 2025. Peer-reviewed RCT, cohort, cross-sectional, and conference papers were included. Single-case studies of invasive BCI technology for ALS were also considered. Methodological quality was evaluated using JBI Critical Appraisal Tools. Results: Thirty-seven studies met inclusion criteria. High-tech AAC—particularly eye-tracking systems and non-invasive BCIs—were most frequently studied. Eye tracking showed high usability but was limited by fatigue, calibration demands, and ocular impairments. EMG- and EOG-based systems demonstrated promising accuracy and resilience to environmental factors, though evidence remains limited. Invasive BCIs showed the highest performance in late-stage ALS and locked-in syndrome, but with small samples and uncertain long-term feasibility. No studies focused exclusively on low-tech AAC interventions. Conclusions: AAC technologies, especially BCIs, EMG and eye-tracking systems, show promise in supporting autonomy in PALS. Implementation gaps persist, including limited attention to caregiver burden, healthcare provider training, and the real-world use of low-tech and hybrid AAC. Further research is needed to ensure that communication solutions are timely, accessible, and effective, and that they are tailored to functional status, daily needs, social participation, and interaction with the environment.

1. Introduction

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease characterised by the degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons, resulting in muscle atrophy and paralysis [1]. Classified as a rare disease, its incidence is approximately two cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year. The etiopathology of ALS remains highly complex and is largely unknown, although several hypotheses have been proposed to explain its origin, highlighting a multifactorial etiopathology [2].

Clinical presentation varies considerably among individuals. Hallmark signs and symptoms of ALS include progressive muscle weakness, atrophy, fasciculations, cramps, spasticity, dysarthria (speech difficulties), dysphagia (swallowing difficulties), dyspnoea (shortness of breath, with progressive restrictive pattern), emotional lability (mood swings), and others [3]. In addition, individuals often experience chewing difficulties and may experience excessive drooling (sialorrhea) [4]. It is essential to note that while cognitive function is typically preserved, up to 15% of People with ALS (PALS) may exhibit signs of frontotemporal dementia in the early stages, and more than 50% may develop cognitive impairment as the disease progresses [5]. Importantly, sensory functions, eye movements, and functions related to sexual health, bowel control, and urinary control typically remain intact [1,3].

Dysarthria is one of the most impactful symptoms affecting communication, particularly in cases with bulbar onset. It involves changes in vocal quality, slowed speech, phonation, orofacial muscle weakness, prosody, imprecise articulation, and incoordination of the stomatognathic system [6,7], ultimately compromising oral communication.

As the condition progresses, 80% to 95% of PALS may lose the ability to use natural speech in daily interactions [8,9]. This progressive loss can lead to frustration, emotional distress, and significant social isolation, negatively influencing quality of life, psychological well-being, and interpersonal relationships [10]. Without adequate communication alternatives, PALS may experience profound barriers to social participation and a greater burden on caregivers [8,11,12].

Communication is inherent to human essence and is therefore fundamental throughout life. Thus, to ensure efficient communication, the parties involved must share a mutual understanding of the information exchanged. In this context, this represents a vital need, as well as a fundamental right, essential to life in society, and its privation can affect day-to-day activities, conditioning intrinsic cognitive and mental performance, as well as needs regarding the relation with the self and different domains (inter- or transpersonal) [10]. Failing to provide communication resources constitutes a barrier to inclusion and violates the principles of equity and participation. Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) resources are needed at some point in the progression of the disease due to the progressive loss of natural speech functionality [9]. This includes technology and training, both of which are necessary, as their practical use directly influences PALS’ quality of life and social interactions.

AAC encompasses any resource, strategy, or technology that enables communication for people with functional speech limitations, facilitating communication between PALS and their partners. It is crucial to refer individuals for AAC intervention as early as possible, as this allows for training and adaptation to begin before their motor condition deteriorates [9]. AAC strategies vary in complexity and cost and can be categorised by technology level. The key categories include [13]: unaided communication systems, relying on body movements, without the need for equipment, such as blinking, transitive gestures, facial expressions and even vocalisations; low-tech resources, which rely on the use of non-electronic tools, such as handwriting and communication boards; high-tech resources comprising electronic devices, speech-generating devices, adaptors, and sensors that can control the devices through body regions, ocular movements, electromyography (EMG), or other interfaces; and brain–computer interfaces (BCIs): a technology that enables the operation of computers through electroencephalography (EEG) signals without requiring neuromuscular activity [14]. This resource may be particularly beneficial for mechanically ventilated patients at risk of developing a locked-in syndrome (LIS) or total LIS, or for other individuals phenotypically similar. Nevertheless, low-tech resources continue to play a central and effective role in supporting everyday interaction and communication [15]. And since high-tech resources are valuable but not infallible, as they may be affected by software errors, technical problems, or power failures, they should be used alongside low-tech resources.

Considering the abovementioned, this study aims to map the existing literature on technological advancements in communication for PALS, with potential applicability to other conditions sharing similar functional and phenotypic trajectories.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review was conducted with the primary objective of mapping scientific knowledge and reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines–extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [16] and the methodological recommendations of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), including the framework of the corresponding Critical Appraisal Tools [17]. A registration number was also obtained: 10.17605/OSF.IO/UKD56 and can be found at the next link (https://osf.io/dtbw3/overview, accessed on 18 December 2025). The process followed the essential stages of evidence mapping: Formulation of the research question, definition of eligibility criteria, identification of descriptors and keywords, development of the search strategy, systematic database searching, screening and selection of studies, extraction of relevant data, narrative synthesis of the results, and preparation of the final report. Since this review used only previously published data and did not involve interaction with human participants or access to identifiable personal data, formal ethics committee approval was not required under applicable European Union regulations and institutional ethical guidelines. No generative artificial intelligence tools were used at any stage of the study.

2.1. Search Strategy

The search strategy was developed using the PCC framework and aimed to identify studies describing AAC technologies used by PALS (population: People with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; concept: Technological advancements in augmentative and alternative communication; context: Clinical and home settings where AAC is applied to support communication in ALS). The search was conducted in September 2025 and included studies published between 01 January 2000 and 31 August 2025. The databases consulted were PubMed, Web of Science, SciELO, Medline via PUBMED, and CINAHL via EBSCO. To maximise comprehensiveness, additional free searches were performed in Google Scholar (using the keywords “AAC augmentative alternative communication systems articles in ALS, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis”. The first 10 pages of results were screened, and 100 records were screened. Screening was stopped after this point, as subsequent pages yielded duplicate or irrelevant records). The complete search strategies for each database are provided in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Table S1). All records identified were imported into the Rayyan platform, where duplicates were removed.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were considered eligible if they addressed AAC technologies or technology-based communication interventions applied to PALS. Original full-text studies were included if they employed methodologies such as randomised controlled trials, cross-sectional studies, cohort studies (retrospective or prospective), case series, or conference communications involving PALS. Conference papers were considered only if they were full conference papers published in proceedings and provided sufficient detail (e.g., study design, data collection, and analysis). Single-case studies were only eligible if they addressed novel or emerging directions relevant to ALS and related phenotypes, such as locked-in syndrome, i.e., studies on the use of invasive BCIs. Review articles, commentaries and opinion papers, animal studies, posters, and communications without full papers and abstracts were excluded. Only studies written in English, French, Portuguese, or Spanish were considered. Articles focusing exclusively on conditions other than ALS were also excluded.

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data were obtained using customised extraction forms. The following information was recorded for each study: study ID, author and year of publication, country, aim, and population details (diagnostic, sample size, ALS stage), AAC modalities and technology level, characteristics and outcomes assessed (for example: communication effectiveness, usability, user perception). The study selection process was conducted in two stages. First, two reviewers (FG, CD) independently screened titles and abstracts based on the predefined eligibility criteria (with an agreement coefficient of 0.98). Studies meeting the criteria, as well as those for which eligibility was unclear, were advanced to the next stage. In the second stage, the full texts of the selected studies were examined in detail by the same reviewers to confirm inclusion. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, and when necessary, a third reviewer (MIT) was consulted to reach a final decision. In parallel, a complementary analysis examined single-case participant studies that described emerging or experimental technologies relevant to ALS and related phenotypes, such as locked-in syndrome, including studies using invasive cortical electrodes.

Data extraction was performed using a structured form developed by the authors. Information was collected on study design, participant characteristics, technological modality, communication objectives, reported outcomes, and key contributions to the advancement of communication technologies. Given the heterogeneity of study designs, technologies assessed, and outcomes reported, the synthesis was conducted narratively, aiming to map the scope, characteristics, trends, and emerging directions of communication technologies applied to individuals with ALS. No new data was created or analysed in this study. Data sharing does not apply to this article.

3. Results

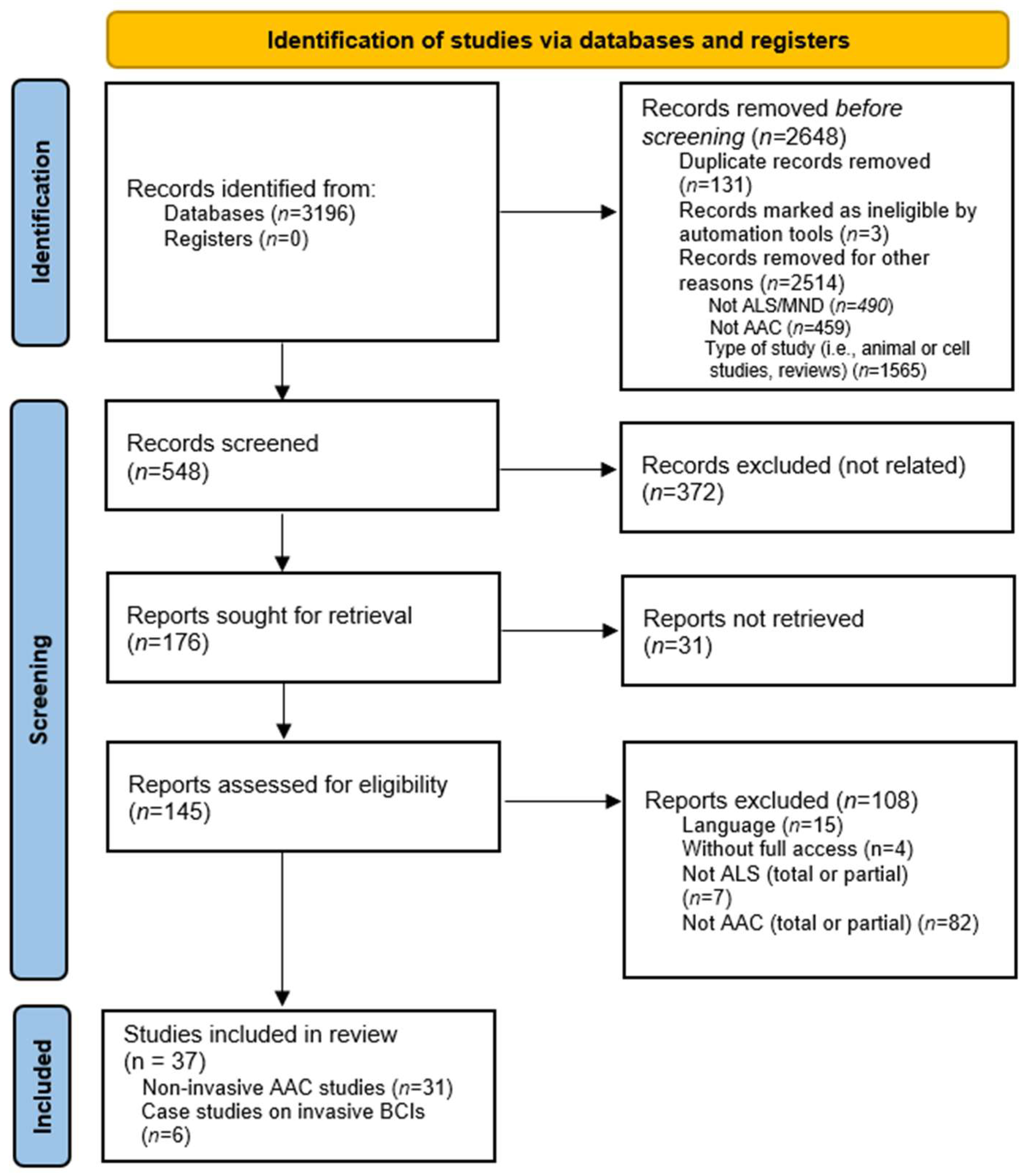

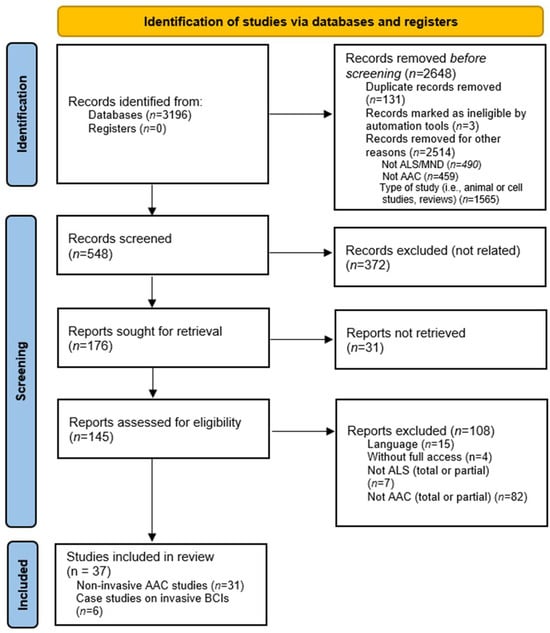

A total of 3196 papers were retrieved. After removing duplicate studies and articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria, 548 titles and abstracts were screened, and 145 were assessed for eligibility. After selection, 37 articles were included in the review. Most of the excluded studies were excluded because the participants were not people with ALS or because they did not assess/intervene at the level of functional communication through AAC systems. A flowchart illustrating the number of records identified, included, and excluded, along with the reasons for exclusions, is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A PRISMA flow chart of study selection.

3.1. General Characteristics of Included Studies

The selected studies were conducted in diverse settings, including specialised ALS clinics, rehabilitation centres, and research laboratories. The studies enrolled adult patients with varying degrees of disease progression, focusing on the implementation and testing of technologies such as eye-tracking, brain–computer interfaces, electromyography, and hybrid communication systems. No studies were performed on children or teenagers with juvenile ALS. Study designs ranged from exploratory cross-sectional analyses to longitudinal cohort investigations, as detailed in Table 1. Six case studies (from 2023 and 2024) that used electrocorticographic, as an invasive brain–computer interface procedure and intervention, are summarised in Table 2.

3.1.1. Access Modality

To better map the current landscape of AAC technologies for ALS, the included studies were grouped according to access modality. Non-invasive approaches, such as eye-tracking systems, were most frequently studied, especially in early- to mid-stage ALS, showing high usability and extended daily use times (median 300 min), though ocular impairments and gaze fatigue limited access for some participants [18,19]. During the disease course, some studies highlight challenges related to calibration time, accuracy, and dropout in more dependent patients, including those with locked-in syndrome (LIS). Electrooculography (EOG)-based systems provided alternative communication channels, advantageous when eye-tracking was no longer feasible [20,21]. Electromyographic (EMG) methods, using facial and limb muscle signals, were explored for both communication and device control [22,23]. EEG-based BCIs employing P300 and steady-state visual evoked potentials (SSVEP) demonstrated variable accuracy and information transfer rates, with interest in applications for advanced ALS and locked-in states [14,24,25,26]. Invasive approaches using ECoG arrays [27,28] and BCIs (including neuroprosthesis) [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36] enabled communication in total locked-in syndrome, achieving functional typing rates. Still, cost, selection, training and day-to-day applicability are highlighted as disadvantages of this method [14,30,31,37]. Hybrid and multimodal systems combining these modalities sought to improve robustness and user experience [26,38]. Augmented reality was reported in one study [39].

3.1.2. Access Regarding ALS Stage and Phenotype

The distribution of technologies aligned closely with ALS disease stage and phenotype. Early-stage ALS patients primarily utilised switches, devices, eye-tracking, EMG, and other low- to high-tech AAC systems to support communication and daily activities [15,18,40,41,42]. As the disease progressed, particularly in advanced ALS and ventilated patients, EEG-based BCIs and invasive ECoG interfaces became more prominent due to the decline of conventional motor control [14,24,27,28]. Studies that included participants with locked-in syndrome (LIS) or total LIS (TLIS) emphasised the critical role of high-tech BCIs and tailored communication systems in maintaining interaction capabilities.

3.1.3. Outcome Categories and Metric Standardisation

Reported outcome metrics varied substantially, reflecting the diverse modalities and study designs. Commonly reported measures included accuracy (% correct selections) [19,22,30,32,33,43,44], spelling rate (characters per minute) [45], words per minute (WPM) [28], selections per minute [43], and information transfer rate (ITR, bits per minute). Caregiver burden and real-world usage time were also evaluated [33]. One study [46] evaluated the use of AAC in clinical settings, including its potential effects on decision-making. ITR measure of communication efficiency is commonly used in BCI studies and depends on accuracy, number of choices, and selection time and is not directly comparable across different paradigms [14,18,19,20,26,27]. EEG P300-based BCI systems often employ SWLDA (stepwise linear discriminant analysis) to classify target vs. non-target stimuli, optimising signal selection and improving spelling accuracy [24,25,47]. One study [20] used dynamic time warping (DTW) (a measure of similarity between two time-dependent sequences) and dynamic path wrapping (DPW) (a programming method similar to DTW, for path alignment of comparison in time-series data), which are algorithms used to align and preprocess time-varying signals such as eye movement or muscle activity before classification. A support vector machine (SVM) can then be applied as a classifier to interpret these processed signals into user commands. Finally, several studies have assessed how individuals interact with their environment through the use of AAC systems [18,19,23,26,39].

Because these metrics are task- and modality-specific, direct quantitative comparisons across access technologies are challenging to make and should be interpreted with caution. Instead, performance outcomes are contextualised within each access modality and disease stage, thereby better representing their practical utility.

Table 1.

Summary of state-of-the-art research studies on assistive technologies for PALS, including author, publication year, AAC modality, participant count and results.

Table 1.

Summary of state-of-the-art research studies on assistive technologies for PALS, including author, publication year, AAC modality, participant count and results.

| Author | Year | Participants | AAC Modality | Application | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horis, J. et al. [45] | 2006 | 5 PALS | EOG and VEB | Selection | Threshold-based, 78-Letters: 87.2%, 8.7 letters/min vs. 12-Letters: 94.1%, 8.9 letters/min |

| Nijboer, F. et al. [25] | 2008 | 6 PALS | EEG (P300) | Communication & Selection | SWLDA, 78% accuracy–online, ITR 9.7 bits/min |

| Mugler, EM. et al. [47] | 2010 | 10 Healthy 3 PALS | EEG (P300) | Internet/ Browser access | SWLDA, 73% accuracy–online, ITR 8.67 bits/min |

| Bloch, S. [15] | 2011 | 4 AAC Records | Text-to-Speech | Analysis of AAC conversation | Difficulties can arise from topic shifts, from understanding the intended action of an AAC word in progress, and from recognising the possible endpoint of an utterance in a natural conversation between a person using an AAC system and an oral speaker. |

| Morris AM. et al. [46] | 2013 | 3 PALS 2 PLS 7 CP or other | Multimodal: Low to High-Tech | AAC interaction and use in the clinical context | Highlight the key barriers and challenges users face when communicating with a healthcare provider: planning and preparing for the appointment, time barriers, inappropriate assumptions, medical decision-making, perception, and implementing the plan of care. |

| McCane, M. et al. [14] | 2014 | 25 PALS | EEG (P300) | Communication & Selection | SWLDA–accuracy [12–92%]. PALS in LIS stat are eligible to use a visual P300-based BCI for communication. In case of a visual impairment, auditory P300-based BCIs might be effective. |

| Spataro, R. et al. [18] | 2014 | 30 PALS | Eye-Track Computer System | Utilisation | Median daily utilisation: 300 min (IQR) for communication, internet browsing, social media, email and work. Oculomotor impairment (dysfunction, gaze fatigue, etc.) reached up to 23.3%, limited function and access. |

| Caron J. et al. [40] | 2015 | 9 PALS | High-tech Speech-Generating Device | Attitudes, Perspectives and Impressions | Providing multiple communication options, including social media, preserves contact and access to communication partners and expands support networks as ALS progresses. |

| Jarosiewicz B. et al. [27] | 2015 | 2 PALS 2 LIS | ECoG | Computer Access and Control | Board layout selection (ABCDEF vs. QWERTY) enhanced usability. Retrospective auto-calibration produced comparable accuracy to the standard decoder (12 vs. 11.4 correct characters per min). Good typing speeds persisted through extended self-typing trials (1–2+ h). [96-channel microarrays over the hand and arm knob area of the dominant motor cortex] |

| Lancioni GE. et al. [48] | 2015 | 42 Health and Care Providers 4 PALS | Microswitches | Technology-Aided Programme: Leisure activities | Microswitches (light-pressure sensors) are a valid resource for PALS when properly trained, anatomic selection, adjustment, and positioning are used. An optic microswitch can be used with a small lip/face response. |

| McCane, M. et al. [24] | 2015 | 14 Healthy 14 PALS | EEG (P300) | Access Speed and Accuracy of ERP-based BCI Systems | P300 speller accuracy and speed did not differ between visually capable PALS vs. controls, but ERP morphology (P300, N200, LN) did. Adding additional ERP components and alternative configurations may improve system performance for ALS. |

| Pasqualotto E. et al. [38] | 2015 | 11 PALS 1 PMND | EEG (P300, visual) and Eye-Track | Usability and Cognitive Workload | Eye-track outperformed visual P300 EEG in both ITR and usability (System Usability Scale), while cognitive workload was significantly higher for the BCI. Future visual BCI designs should incorporate eye–tracking–based control, or a multimodal approach. |

| Rahnama M. et al. [19] | 2015 | 4 Healthy 1 PALS | Eye-Track | Access and Control | A calibration-free eye-tracking system might be feasible for PALS. The mean error rate was 5.68%, which is acceptable. Accuracy was lower than that of some commercial systems but might compensate for ocular access issues. |

| Wang, Y. et al. [22] | 2015 | 3 Healthy 1 PALS | EMG | Rehabilitation | Accuracy: facial expressions 98% vs. finger movements 93.9% vs. hand and arm movements 100% Threshold-based |

| Geronimo A. et al. [37] | 2016 | 15 Healthy 25 PALS | EEG (P300) | Access and Selection | Cognitive deficits lower the task-relevant EEG signal-to-noise ratio and reduce BCI accuracy; behavioural dysfunction further impairs P300 performance. Age influences paradigm suitability, with older PALS performing better on P300 speller outcomes than on motor-imagery tasks. Triage should include cognitive and behavioural screening. |

| Chang, WD. et al. [20] | 2017 | 18 Healthy 3 PALS | EOG | Communication | DTW/DPW/SVM Accuracy: Healthy [91–95%] vs. PALS [81–85%] |

| Poletti B. et al. [49] | 2017 | 21 PALS | Eye-Track | Assessment of Cognitive Abilities | Eye tracker–based cognitive testing outperformed the Frontal Assessment Battery8 and matched MoCA/WM in diagnostic accuracy while maintaining consistent usability. It enables a comprehensive assessment of ALS-specific cognitive domains and overcomes the limitations of standard paper-based tools in later stages of ALS. |

| Guy, V. et al. [43] | 2018 | 20 PALS | EEG (P300) | Communication & Selection | PALS completed all spelling tasks and were efficient, with 65% selecting more than 95% of the correct symbols. The number of correct symbols selected/minute: [3.6 (without prediction) vs. 5.04 (with)]. |

| Kin DY. et al. [21] | 2018 | 10 Healthy 2 PALS (LIS) | EOG | Communication | Accuracy was 94% for healthy subjects and PALS with 6s decision windows. In a binary (yes/no) task, PALS scored 94% in a 26–30 question. |

| Milekovic T. et al. [28] | 2018 | 1 PALS 1 LIS | ECoG | Restore Communication in LIS state | Participants performed functional tasks (typing messages, using text-to-speech, and sending emails) at spelling rates of 3.07–6.88 correct characters per minute. [6-channel intracortical multielectrode array implanted in the dominant precentral gyrus arm area]. |

| Nuyujukian P. et al. [50] | 2018 | 2 PALS 1 SPI (C4) | ECoG | Multielectrode arrays (hand ar ea: Dominant motor cortex) | A point-and-click Bluetooth mouse enabled participants to browse, email, chat, play music apps, and send texts; two users used the BCI to chat with each other live. |

| Dash, D. et al. [32] | 2020 | 7 Healthy 3 PALS | MEG | Decoding | Performance for PALS is lower than for healthy subjects but still significantly above chance level. PALS scored 94% on a 26–30 binary (yes/no) question task. |

| Geronimo A. et al. [33] | 2020 | 15 PMND 15 Caregivers | EEG (P300) | TeleBCI to operate a virtual keyboard | Setup and spelling times improved between sessions; 7 PMND reached proficiency and used the advanced notepad speller to communicate. High performers increased P300 spelling accuracy by 2.6% per session. PMND reported the EEG demanded more time, space, and stamina than expected. |

| Peters B. et al. [26] | 2020 | 2 PALS | EEG (SSVEP) & Eye-Tracking | Multimodal/Combinatory controls | SSVEP BCI outperformed eye-tracking for shuffle-spell typing in advanced (LIS) PALS. Fatigue and performance drop-off can occur. |

| Rocha, LAA. et al. [51] | 2020 | 10 Healthy 4 PALS | EMG & EOG | Communication & Selection | Selection times: healthy–300 ms (EMG), 550 ms (EOG), 450 ms (acceleration), 175 ms (ON/OFF sensors) vs. PALS–600 ms/280 ms (after 30 days) |

| Tonin A. et al. [44] | 2020 | 4 PALS (LIS) | EOG (auditory) | Communication and Interaction | A binary-based auditory speller enabled sentence-level communication in PALS with minimal eye movement (±200 μV to ± 40 μV). One PALS maintained use for over a year, while the capability for eye-tracking movement declined. |

| Bona S. et al. [39] | 2021 | 12 PALS | Augmented Reality with Integrated Eye-track | Environment Control | PALS showed improved system engagement and self-management, with gains in competence, adaptability, and self-esteem—indicating a positive psychosocial impact of the assistive device. Ocular symptoms in some patients may affect performance. |

| Manero AC. et al. [23] | 2022 | 4 PALS | EMG | Mobility Device Control | Wheelchair Skills Test with progressive improvement and time to complete/drive: 75% improvement in mobility/ conduction. Threshold-based |

| Peters B. et al. [42] | 2023 | 222 PALS | Low-tech (unaided communication) vs. High-tech (aid AAC) | Assessment of utility and usability | Higher score in CPIB in the high-tech group (mean increase: 4.75). PALS with anarthria (ALSFRS-R speech rating = 0) reported better participation under the all-methods condition than those who used residual speech in combination with non-speech methods. |

| Bettencourt. R. et al. [30] | 2024 | 5 Healthy 1 PALS (LIS) | EEG (P300) | Communication & Selection | 10-month follow-up, 90% online accuracy in one session vs. subsequent sessions average accuracy [56.4 ± 15.2%] |

| Cave, R. [52] | 2024 | 6 PALS | ASR | Communication & Interactions | 12-month follow-up. PALS reported lower-than-expected ASR accuracy when used in conversation and felt ASR captioning was only helpful in specific contexts. Future improvements might increase day-to-day usability. |

Legend: AAC—augmentative and alternative communication, ALSFRS-R—Revised ALS Functional Rating Scale, ASR—automated speech recognition, BCI—brain computer interface, CP—cerebral palsy, DPW—dynamic path wrapping, CPIB—General Short Form of the Communicative Participation Item Bank, DTW—dynamic time warping, ECoG—electrocorticographic, EEG—electroencephalography, EMG—electromyography, EOG—electrooculogram, ERP—Event-Related Potentials, IQR—interquartile range, ITR—information transfer rate, MEG—Magnetoencephalography, PALS—People with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, PLS—primary lateral sclerosis, PMND—People with motoneuron disease, SSVEP—steady state visual evoked potential, SWLDA—stepwise linear discriminant analysis, SVM—support vector machine.

Table 2.

Research single-case studies on intracortical implants (invasive brain–computer interface), for PALS.

Table 2.

Research single-case studies on intracortical implants (invasive brain–computer interface), for PALS.

| Author | Year | Participants | AAC Modality | Local | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luo S. et al. [53] | 2023 | 1 PALS | ECoG | Two 8 × 8 implants (motor and somatosensory areas) | Commands were reliably detected as the PALS navigated a communication board and controlled devices (room lights, streaming TV). Stable decoders with few (re)calibrations are required for home use. [arrays over the upper extremity and speech functions] |

| Willet FR. et al. [35] | 2023 | 1 PALS | ECoG | Two 8 × 8 Microarrays (area 6v), two 8 × 8 (area 44) | ALS reached 62 words per minute, markedly higher than other systems in use. Accuracy was lower, 9.1% word error rate on a 50-word vocabulary vs. 23.8% for 125,000-words. [3.2 mm arrays] |

| Angrick M. et al. [29] | 2024 | 1 PALS | ECoG | Two 8 × 8 Electrode Arrays (Sensorimotor Areas) | An RNN-based pipeline identified, decoded, and synthesised speech from ciBCI signals recorded from motor, premotor, and somatosensory areas, achieving 80% word intelligibility by human listeners. Training used an initial learning rate of 0.001. [arrays over face, tongue, and upper limb regions representations] |

| Candrea DN. et al. [31] | 2024 | 1 PALS | ECoG | Two 8 × 8 Subdural Grids (Sensoriomotor Cortex) | Median spelling rate of 10.2 characters per minute. Low subjective workload was assessed by NAS-TLX scores (mental demand, physical, temporal and performance). [36.6 mm × 33.1 mm, over representations for speech and upper extremity movements in the left hemisphere] |

| Card, N. et al. [34] | 2024 | 1 PALS | ECoG | 4 Microelectrode Arrays (left ventral precentral gyrus) | Decode and attempt to speak with an accuracy of 99.6% (50 words vocabulary) vs. after training, 97.5% (125,000 words, rate of approximately 32 words per min, with the use of text-to-speech software and pre-recorded voice) [3.2 × 3.2 mm in size and electrode depth 1.5 mm] |

| Wyse-Sookoo et al. [36] | 2024 | 1 PALS | ECoG | Two 64-channel grids (ventral sensorimotor cortex) | After an initial increase in signal strength during the first 5 months, high gamma responses remained stable for at least 12 months [36.66 mm × 33.1 mm, 8 × 8 configuration]. |

Legend: AAC—augmentative and alternative communication, EEG—electroencephalography, ciBCI—chronically implanted BCI, ECoG—electrocorticographic, PALS—Person with amyotrophic lateral.

4. Discussion

Human communication primarily relies on speech, a capability that is severely compromised in PALS, presenting a significant barrier to their social interactions. In this context, AAC stands out as an essential technological breakthrough. Ranging from simple, low-tech solutions to advanced, high-tech tools, AAC empowers individuals to engage meaningfully and participate more fully in society and daily living activities [7,13]. The success of AAC is rooted in a comprehensive, personalised assessment that addresses each person’s unique challenges and potential within their specific life circumstances and personal characteristics [7,10,12,13]. The analysed literature shows strong consensus on the importance of utilising AAC, particularly highlighting the roles of BCIs as a potential technology [30,35,37,43] and of eye trackers [18,20,41,45,49] as a more versatile and accessible tool throughout the course of ALS. The studies included in this review demonstrated that AAC technologies, ranging from low-tech to invasive BCIs, provide critical communication support across different stages of ALS, with the choice of modality often determined by motor function and disease progression. Performance metrics indicate that non-invasive systems are generally effective from early to advanced-stage ALS [18,49,51,54,55], while brain computer interfaces may be necessary to maintain communication in LIS/TLIS patients [27,30,31,33,37,43]. In this matter, Consistent with earlier reviews, we observed that EEG-based BCIs yield variable accuracy and workload, highlighting the need for individualised device selection [14,21,24,25]. Invasive EEG seems promising [29,31,34,52], but further investigation is needed. This review may also highlight a lack of studies addressing more accessible, day-to-day technologies, ranging from indirect to direct communication strategies, different switches, and adaptations required throughout the ALS journey, including software and apps, laser and gaze/ocular access, AI, virtual reality, avatars, agents, voice-bank donation or archiving, and others that reflect practical experience. Many of these resources are routinely used as essential tools in clinical rehabilitation and palliative care, forming part of the options that can further support communication for PALS.

Studies have shown that early implementation of AAC systems can significantly enhance PALS’ participation in daily activities and improve interactions with communication partners [28,39,42]. Strategies and interventions that effectively utilise technological resources can strengthen the remaining communicative abilities of these individuals, promote social inclusion, and contribute to the development of a more inclusive society [11,40,55]. For individualised AAC care plans to be implemented effectively, they must be supported by continuous training and be easy to use and affordable. These factors are essential because many healthcare professionals are not fully confident in applying AAC solutions. A lack of training and usability can compromise communication, lead to unmet expectations, and increase frustration and misunderstandings among people with ALS and their communication partners, including healthcare providers [12,46,56].

High-tech AAC systems allow for complex, caregiver-independent communication with minimal or no head or limb movement, such as eye-tracking computer systems [41] or a click-to-activate activation surface (like buttons, switches, microswitches, etc., with tactile and auditory feedback and 10 to 75 g of force to activate) [48]. Eye-tracking technology is widely used because it allows PALS to operate speech-generating devices through eye movements [9,18], often one of the last muscle functions to decline [1,3,57]. However, its effectiveness can be reduced by factors such as fatigue, ocular sensitivity changes, or eyelid ptosis, in addition to visual impairments and environmental conditions, making it unreliable in specific contexts [12,39,54,57]. Furthermore, it requires appropriate positioning of the individual relative to the device, and communication is generally slower compared to spontaneous speech. Training is not implicit at first contact but represents an essential part of the adaptation process. In view of these challenges, there is growing interest in novel AAC methods. EMG is reemerging as a promising tool because it measures muscle electrical activity and records it noninvasively using surface EMG (sEMG), which is relevant for PALS, as many retain control over upper facial muscles, such as those involved in eye and eyebrow movements or periorbital contractions [22]. EMG has garnered attention for its potential in rehabilitation and for environmental and functional activities, such as operating a power wheelchair [23]. However, its application in AAC systems remains underexplored, though some studies and commercial solutions show promise [22,51]. Hybrid or personalised approaches that can adapt to various daily scenarios may serve as effective communication strategies [10,39,40,42]. Furthermore, EMG, combined with generative artificial intelligence, facilitated rapid, low-effort interactions through calibration [22,51]. However, most of these innovations have been primarily tested on healthy individuals, indicating a need for further research in relevant contexts for PALS. EOG has been explored as an AAC method that allows users to communicate through eye movements or blinks, such as selecting letters or navigating a virtual keyboard [45]. EOG-based systems can achieve high accuracy, often exceeding 80%, with typing speeds ranging from 6.4 to 11 letters per minute, sometimes outperforming EEG-based systems [20,21,44]. Advantages of EOG include minimal sensitivity to changes in lighting, portability, low cost, and reduced complexity [45]. Additionally, EOG can detect eye motion even when the eyes are closed. However, it is usually less effective than camera-based eye tracking due to lower spatial accuracy [44,54]. As a result, it is better suited for analysing relative eye movements (such as left or right gaze) rather than determining the exact point a person is looking at.

More severe states, such as LIS (partial to total), can particularly benefit from AAC technologies, including BCI and eye tracking, as these can significantly improve their QoL [18,28,30,44,58]. EEG, especially P300-evoked potentials, is the most common non-invasive BCI solution in this field [24,25,30,33,38,43,47]. Invasive chronic implants are a possible solution to this state [5,29,31,34,35,53,59], but further studies are needed, and careful ethical considerations are required [59]. Other factors should also be accounted for, such as durability, accuracy, safety, privacy, potential burden imposed on caregivers, and usability in home and day-to-day scenarios. As well, the increasing accessibility and continuous advancements in technologies, such as virtual reality (VR) goggles [27,60], portable eye trackers, and head-mounted displays, have led to an uptick in their use and may promote the exploration of novel communication solutions. While VR offers promising applications in this context, careful attention must be paid to affordability and to interface design tailored specifically for this population. A user-centred design approach is critical for developing functional, widely accepted communication technologies that account for factors such as positioning, fatigue, ventilation requirements, and musculoskeletal deformities resulting from amyotrophy. Furthermore, the design of high-technology systems for individuals with LIS must integrate technological and environmental considerations across home, healthcare, and other settings, as these elements profoundly influence patient well-being and the effectiveness of communication interfaces [61]. Thus, a comprehensive understanding of how these technologies facilitate emotional expression and interaction with caregivers and support networks is essential [61,62].

Regarding speech production, in words per minute (WPM), eye gaze fixation typically ranges from 10 to 20 WPM [63]. This is significantly lower than natural speech at approximately 150 WPM and standard keyboard typing at around 40 WPM [63]. Factors such as calibration, positioning, lighting, fatigue, and ocular health can further compromise WPM and accuracy [18,19,38]. The primary biosignal-based access methods include EEG, EOG, and EMG [20,21,22,24,30,45]. These methods may provide long-term solutions when traditional systems that depend on eye-gaze or on adaptive switches become ineffective. Among these, the P300 event-related potential, characterised by a positive deflection in EEG around 300 ms post-stimulus, is the most commonly used [24,25,33,43,44]. Research indicates that while many users achieve high accuracy with the P300 speller, others experience variable accuracy and fatigue, resulting in communication rates of only 1.5 to 4.1 selections per minute [14,24,43]. Furthermore, mastering BCI technology is more complex than using non-BCI AAC systems, as it requires users to learn to control their brain activity [54,64], properly apply electrodes, and maintain user comfort, focus, and awareness. Healthcare professionals also need specialised training.

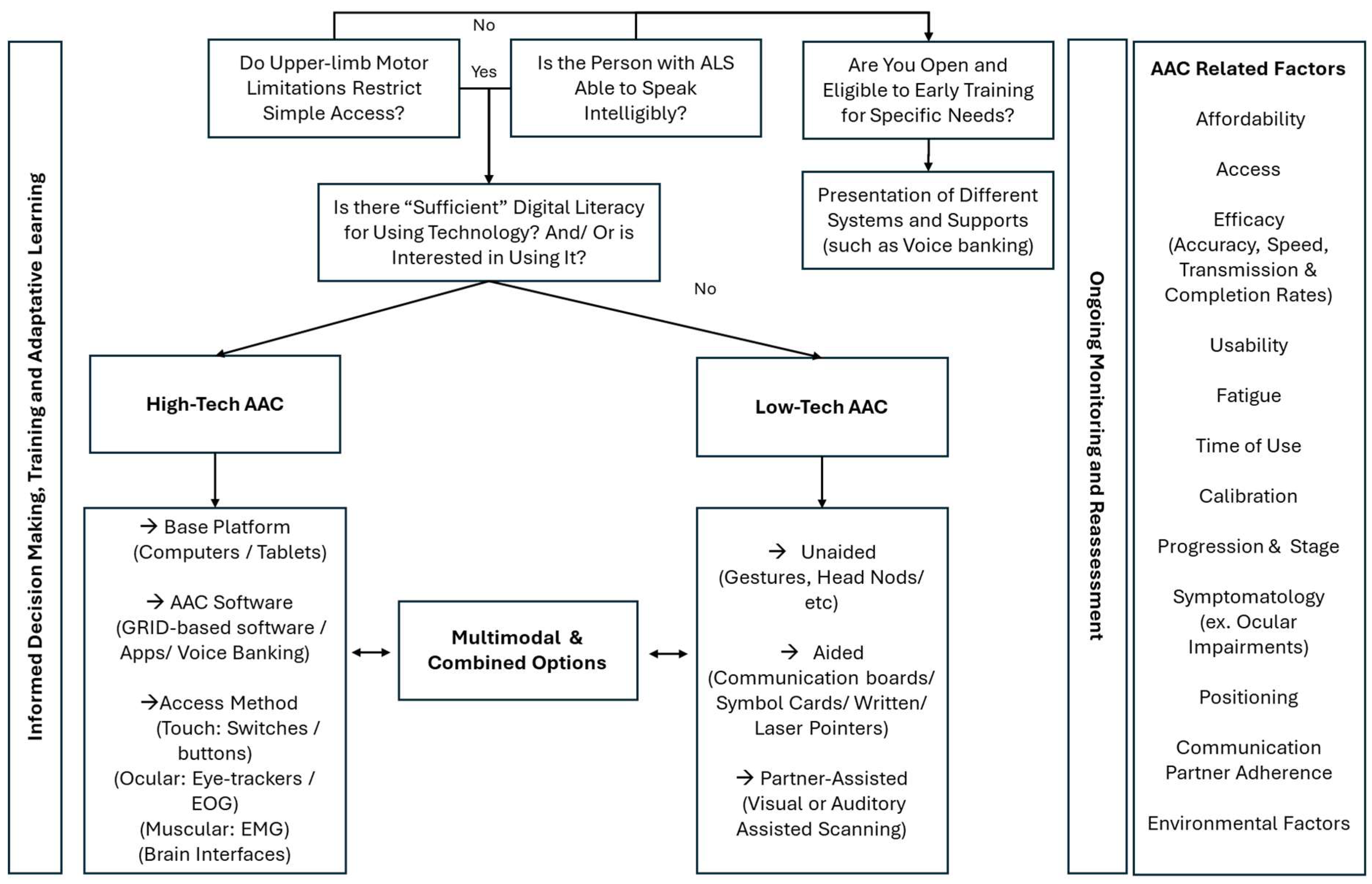

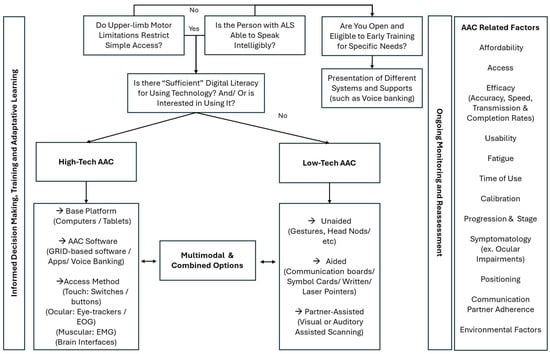

Nevertheless, alongside the use of high-tech communication resources, it is essential to provide low-tech strategies (Figure 2). These complementary resources enable a practical and more immediate communication in situations where the use of electronic devices is unfeasible or unavailable at a given time, with problems related to equipment itself (e.g., technological failure, batteries, breakdowns, etc.), clinical progression of the PALS, that can compromise high-tech usability (calibration, synchronisation, activation, errors, etc.) or that can significant reduce PALS tolerability and time of use of the AAC systems [11,19,28,53].

Figure 2.

Assessing the Communication Needs of People with ALS.

This review has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Regarding BCIs, many of the included studies rely on low-sample designs or case studies, particularly in invasive EEG, and there is substantial heterogeneity in task design and behavioural paradigms. Despite methodological strengths in most studies, limitations such as inconsistent outcome measures were noted. Variations in tasks—such as motor imagery and speech decoding—affect decoding accuracy, cognitive load, and system reliability, underscoring the need for standardised protocols and performance metrics. The studies also present a wide range of AAC solutions that may not be representative of the systems used daily by PALS in different functional states. This limits generalisability, as the samples do not reflect individuals with varying levels of disease severity, literacy, or degrees of social and digital participation and engagement. Participant attrition, while common in degenerative conditions, introduces potential bias, and self-reported data can lead to recall bias, affecting the verification of usage frequency criteria. Finally, the AAC solutions described in the analysed studies may not accurately reflect what is actually available and used in everyday life. This is because studies often overlook practical, commonly used solutions, such as environmental controllers (via Bluetooth or infrared), speech generators, direct-access software, apps, pointers/lasers, adapted mice, and various eye-trackers. Many of these technologies are already widely accepted by rehabilitation teams and the PALS community, which results in few formal studies or reports on their daily use, even though they are frequently prescribed. Additionally, while commercial AAC solutions may be available or under development, they are often not classified as health or rehabilitation products but are instead categorised for commercial use and licensing. To improve comparability and applicability, future research should employ broader sampling methods, standardised reporting protocols, and longitudinal designs, with particular attention to the different functional phenotypes of ALS and its diverse trajectories.

5. Conclusions

Recent research reveals a growing focus on assistive communication technologies, especially BCIs and eye-tracking systems, since 2006. However, there are significant gaps in their real-world application for PALS. To enhance participatory inclusion and engagement, it is crucial to personalise care, adapt communication methods, and integrate technology, including direct and indirect access to high-tech AAC, low-tech devices, software, apps, and new technologies, to explore the best options for each PALS fully. Additionally, research must consider the impact of these technologies on caregivers and healthcare providers, as well as on training, burden, and access. While assistive technologies are vital for fostering communicative autonomy, dignity and adapted QoL, further investigation is needed to bridge implementation gaps and create more accessible, on-time, and effective interventions for users and caregivers alike.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information: search strategy, summarised in Supplementary Table S1, can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/sclerosis4010002/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: F.G. and C.D.; methodology: F.G., validation: F.G. and C.S.F.; formal analysis: F.G., C.D. and M.I.T. (3rd reviewer); investigation, F.G., C.D. and M.I.T.; data curation F.G., C.D. and M.I.T.; writing—original draft preparation F.G., C.D. and C.S.F.; writing—review and editing F.G., C.S.F., C.D., M.I.T. and C.M.; supervision, F.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAC | Augmentative Alternative Communication |

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| BCI | Brain Computer Interface |

| DPQ | Dynamic path wrapping |

| DTW | Dynamic time warping |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| ECoG | Electrocorticographic |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| EOG | Electrooculogram |

| PALS | People with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| SWLDA | Stepwise linear discriminant analysis |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TLIS/LIS | Total locked-in syndrome/locked-in syndrome |

| VEM | Voluntary eye blink |

References

- Hardiman, O.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Chio, A.; Corr, E.M.; Logroscino, G.; Robberecht, W.; Shaw, P.J.; Simmons, Z.; van den Berg, L.H. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiò, A.; Mazzini, L.; D’Alfonso, S.; Corrado, L.; Canosa, A.; Moglia, C.; Manera, U.; Bersano, E.; Brunetti, M.; Barberis, M.; et al. The multistep hypothesis of ALS revisited: The role of genetic mutations. Neurology 2018, 91, e635–e642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, P.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Andersen, P.M.; Chiò, A.; Couratier, P.; De Carvalho, M.; Hardiman, O.; Kuźma-Kozakiewicz, M.; Ludolph, A.; McDermott, C.J.; et al. European Academy of Neurology (EAN) guideline on the management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in collaboration with European Reference Network for Neuromuscular Diseases (ERN EURO-NMD). Eur. J. Neurol. 2024, 31, e16264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelica, B.; Petri, S. Narrative review of diagnosis, management and treatment of dysphagia and sialorrhea in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 6508–6513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahams, S. Neuropsychological impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-frontotemporal spectrum disorder. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2023, 19, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiaramonte, R.; Bonfiglio, M. Acoustic analysis of voice in bulbar amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies. Logop. Phoniatr. Vocol. 2020, 45, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkonen, T.; Ruottinen, H.; Puhto, R.; Helminen, M.; Palmio, J. Speech deterioration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) after manifestation of bulbar symptoms. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2018, 53, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londral, A. Assistive Technologies for Communication Empower Patients with ALS to Generate and Self-Report Health Data. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 867567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beukelman, D.; Fager, S.; Nordness, A. Communication Support for People with ALS. Neurol. Res. Int. 2011, 2011, 714693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.; Teixeira, M.I.; Rego, F.; Magalhães, B. The role of spiritual care management—Needs and resources in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Insights from a mixed-methods study. Palliat. Support. Care 2025, 23, e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.; Magalhães, B. Effects of prolonged interruption of rehabilitation routines in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Palliat. Support. Care 2022, 20, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linse, K.; Aust, E.; Joos, M.; Hermann, A. Communication Matters-Pitfalls and Promise of Hightech Communication Devices in Palliative Care of Severely Physically Disabled Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried-Oken, M.; Mooney, A.; Peters, B. Supporting communication for patients with neurodegenerative disease. NeuroRehabilitation 2015, 37, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCane, L.M.; Sellers, E.W.; McFarland, D.J.; Mak, J.N.; Carmack, C.S.; Zeitlin, D.; Wolpaw, J.R.; Vaughan, T.M. Brain-computer interface (BCI) evaluation in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2014, 15, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloch, S. Anticipatory other-completion of augmentative and alternative communication talk: A conversation analysis study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 33, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; Al, E. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Stone, J.C.; Aromataris, E.; Klugar, M.; Sears, K.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Barker, T.H. Assessing the risk of bias of quantitative analytical studies: Introducing the vision for critical appraisal within JBI systematic reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spataro, R.; Ciriacono, M.; Manno, C.; La Bella, V. The eye-tracking computer device for communication in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2014, 130, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnama-ye-Moqaddam, R.; Vahdat-Nejad, H. Designing a pervasive eye movement-based system for ALS and paralyzed patients. In Proceedings of the 2015 5th International Conference on Computer and Knowledge Engineering (ICCKE), Mashhad, Iran, 29 October 2015; pp. 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.D.; Cha, H.S.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Im, C.H. Development of an electrooculogram-based eye-computer interface for communication of individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Han, C.-H.; Im, C.-H. Development of an electrooculogram-based human-computer interface using involuntary eye movement by spatially rotating sound for communication of locked-in patients. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Su, A.W.Y.; Han, T.Y.; Lin, C.L.; Hsu, L.C. EMG based rehabilitation systems—Approaches for ALS patients in different stages. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), Torino, Italy, 29 June–3 July 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manero, A.C.; McLinden, S.L.; Sparkman, J.; Oskarsson, B. Evaluating surface EMG control of motorized wheelchairs for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCane, L.M.; Heckman, S.M.; McFarland, D.J.; Townsend, G.; Mak, J.N.; Sellers, E.W.; Zeitlin, D.; Tenteromano, L.M.; Wolpaw, J.R.; Vaughan, T.M. P300-based brain-computer interface (BCI) event-related potentials (ERPs): People with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) vs. age-matched controls. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2015, 126, 2124–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijboer, F.; Sellers, E.W.; Mellinger, J.; Jordan, M.A.; Matuz, T.; Furdea, A.; Halder, S.; Mochty, U.; Krusienski, D.J.; Vaughan, T.M.; et al. A P300-based brain–computer interface for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008, 119, 1909–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.; Bedrick, S.; Dudy, S.; Eddy, B.; Higger, M.; Kinsella, M.; McLaughlin, D.; Memmott, T.; Oken, B.; Quivira, F.; et al. SSVEP BCI and Eye Tracking Use by Individuals with Late-Stage ALS and Visual Impairments. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 595890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosiewicz, B.; Sarma, A.A.; Bacher, D.; Masse, N.Y.; Simeral, J.D.; Sorice, B.; Oakley, E.M.; Blabe, C.; Pandarinath, C.; Gilja, V.; et al. Virtual typing by people with tetraplegia using a self-calibrating intracortical brain-computer interface. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 313ra179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milekovic, T.; Sarma, A.A.; Bacher, D.; Simeral, J.D.; Saab, J.; Pandarinath, C.; Sorice, B.L.; Blabe, C.; Oakley, E.M.; Tringale, K.R.; et al. Stable long-term BCI-enabled communication in ALS and locked-in syndrome using LFP signals. J. Neurophysiol. 2018, 120, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angrick, M.; Luo, S.; Rabbani, Q.; Candrea, D.N.; Shah, S.; Milsap, G.W.; Anderson, W.S.; Gordon, C.R.; Rosenblatt, K.R.; Clawson, L.; et al. Online speech synthesis using a chronically implanted brain–computer interface in an individual with ALS. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, R.; Castelo-Branco, M.; Gonçalves, E.; Nunes, U.J.; Pires, G. Comparing Several P300-Based Visuo-Auditory Brain-Computer Interfaces for a Completely Locked-in ALS Patient: A Longitudinal Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candrea, D.N.; Shah, S.; Luo, S.; Angrick, M.; Rabbani, Q.; Coogan, C.; Milsap, G.W.; Nathan, K.C.; Wester, B.A.; Anderson, W.S.; et al. A click-based electrocorticographic brain-computer interface enables long-term high-performance switch scan spelling. Commun. Med. 2024, 4, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, D.; Ferrari, P.; Babajani-Feremi, A.; Borna, A.; Schwindt, P.D.D.; Wang, J. Magnetometers vs Gradiometers for Neural Speech Decoding. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2021, 2021, 6543–6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geronimo, A.; Simmons, Z. TeleBCI: Remote user training, monitoring, and communication with an evoked-potential brain-computer interface. Brain Comput. Interfaces 2020, 7, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Card, N.S.; Wairagkar, M.; Iacobacci, C.; Hou, X.; Singer-Clark, T.; Willett, F.R.; Kunz, E.M.; Fan, C.; Nia, M.V.; Deo, D.R.; et al. An Accurate and Rapidly Calibrating Speech Neuroprosthesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, F.R.; Kunz, E.M.; Fan, C.; Avansino, D.T.; Wilson, G.H.; Choi, E.Y.; Kamdar, F.; Glasser, M.F.; Hochberg, L.R.; Druckmann, S.; et al. A high-performance speech neuroprosthesis. Nature 2023, 620, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyse-Sookoo, K.; Luo, S.; Candrea, D.; Schippers, A.; Tippett, D.C.; Wester, B.; Fifer, M.; Vansteensel, M.J.; Ramsey, N.F.; Crone, N.E. Stability of ECoG high gamma signals during speech and implications for a speech BCI system in an individual with ALS: A year-long longitudinal study. J. Neural Eng. 2024, 21, 046016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geronimo, A.; Simmons, Z.; Schiff, S.J. Performance predictors of brain-computer interfaces in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neural Eng. 2016, 13, 026002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualotto, E.; Matuz, T.; Federici, S.; Ruf, C.A.; Bartl, M.; Olivetti Belardinelli, M.; Birbaumer, N.; Halder, S. Usability and Workload of Access Technology for People with Severe Motor Impairment: A Comparison of Brain-Computer Interfacing and Eye Tracking. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2015, 29, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bona, S.; Donvito, G.; Cozza, F.; Malberti, I.; Vaccari, P.; Lizio, A.; Greco, L.; Carraro, E.; Sansone, V.A.; Lunetta, C. The development of an augmented reality device for the autonomous management of the electric bed and the electric wheelchair for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A pilot study. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2021, 16, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, J.; Light, J. “My World Has Expanded Even Though I’m Stuck at Home”: Experiences of Individuals with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Who Use Augmentative and Alternative Communication and Social Media. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2015, 24, 680–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caligari, M.; Godi, M.; Guglielmetti, S.; Franchignoni, F.; Nardone, A. Eye tracking communication devices in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Impact on disability and quality of life. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2013, 14, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, B.; Wiedrick, J.; Baylor, C. Effects of Aided Communication on Communicative Participation for People with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2023, 32, 1450–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, V.; Soriani, M.H.; Bruno, M.; Papadopoulo, T.; Desnuelle, C.; Clerc, M. Brain computer interface with the P300 speller: Usability for disabled people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 61, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonin, A.; Jaramillo-Gonzalez, A.; Rana, A.; Khalili-Ardali, M.; Birbaumer, N.; Chaudhary, U. Auditory Electrooculogram-based Communication System for ALS Patients in Transition from Locked-in to Complete Locked-in State. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, J.; Sakano, K.; Miyakawa, M.; Saitoh, Y. Eye Movement Communication Control System Based on EOG and Voluntary Eye Blink. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Miesenberger, K., Klaus, J., Zagler, W.L., Karshmer, A.I., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germnay, 2006; pp. 950–953. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M.A.; Dudgeon, B.J.; Yorkston, K. A qualitative study of adult AAC users’ experiences communicating with medical providers. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2013, 8, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugler, E.M.; Ruf, C.A.; Halder, S.; Bensch, M.; Kubler, A. Design and implementation of a P300-based brain-computer interface for controlling an internet browser. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2010, 18, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancioni, G.E.; Simone, I.L.; De Caro, M.F.; Singh, N.N.; O’Reilly, M.F.; Sigafoos, J.; Ferlisi, G.; Zullo, V.; Schirone, S.; Denitto, F.; et al. Assisting persons with advanced amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in their leisure engagement and communication needs with a basic technology-aided program. NeuroRehabilitation 2015, 36, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poletti, B.; Carelli, L.; Solca, F.; Lafronza, A.; Pedroli, E.; Faini, A.; Ticozzi, N.; Ciammola, A.; Meriggi, P.; Cipresso, P.; et al. An eye-tracker controlled cognitive battery: Overcoming verbal-motor limitations in ALS. J. Neurol. 2017, 264, 1136–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuyujukian, P.; Albites Sanabria, J.; Saab, J.; Pandarinath, C.; Jarosiewicz, B.; Blabe, C.H.; Franco, B.; Mernoff, S.T.; Eskandar, E.N.; Simeral, J.D.; et al. Cortical control of a tablet computer by people with paralysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, L.A.A.; Naves, E.L.M.; Morére, Y.; de Sa, A.A.R. Multimodal interface for alternative communication of people with motor disabilities. Res. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 36, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cave, R. How People Living with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Use Personalized Automatic Speech Recognition Technology to Support Communication. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2024, 67, 4186–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Angrick, M.; Coogan, C.; Candrea, D.N.; Wyse-Sookoo, K.; Shah, S.; Rabbani, Q.; Milsap, G.W.; Weiss, A.R.; Anderson, W.S.; et al. Stable Decoding from a Speech BCI Enables Control for an Individual with ALS without Recalibration for 3 Months. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2304853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F.; Barbalho, I.; Bispo Júnior, A.; Alves, L.; Nagem, D.; Lins, H.; Arrais Júnior, E.; Coutinho, K.D.; Morais, A.H.F.; Santos, J.P.Q.; et al. Digital Alternative Communication for Individuals with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: What We Have. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.; Rodrigues, I.T.; Gonçalves, H.; Duarte, I. Communication strategies for adults in palliative care: The speech-language therapists’ perspective. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.; Teixeira, M.I.; Magalhães, B. The role of spirituality in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and their caregivers: Scoping review. Palliat. Support. Care 2023, 21, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, A.; Xia, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Gao, S. A Visual Feedback Supported Intelligent Assistive Technique for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patients. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4, 2100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larradet, F.; Barresi, G.; Mattos, L.S. Affective Communication Enhancement System for Locked-In Syndrome Patients. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Design Approaches and Supporting Technologies; Antona, M., Stephanidis, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Vansteensel, M.J.; Klein, E.; van Thiel, G.; Gaytant, M.; Simmons, Z.; Wolpaw, J.R.; Vaughan, T.M. Towards clinical application of implantable brain–computer interfaces for people with late-stage ALS: Medical and ethical considerations. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 1323–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, J.L.; Saredakis, D.; Hutchinson, A.D.; Crawford, G.B.; Loetscher, T. Virtual Reality in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penedos-Santiago, E.; Simões, S.; Amado, P.; Giesteira, B. Drawing for Social Re-Connectivity Through Collaborative and Digital Environments. Preliminary Drawing Activities. In Perspectives and Trends in Education and Technology; Abreu, A., Carvalho, J.V., Mesquita, A., Sousa Pinto, A., Mendonça Teixeira, M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 242–247. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Deng, C.; Peng, M.; Hao, Y. Experiences and perceptions of palliative care patients receiving virtual reality therapy: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mott, M.; Williams, S.; Wobbrock, J.; Morris, M. Improving Dwell-Based Gaze Typing with Dynamic, Cascading Dwell Times. In Proceedings of the CHI ‘17: 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Akcakaya, M.; Peters, B.; Moghadamfalahi, M.; Mooney, A.R.; Orhan, U.; Oken, B.; Erdogmus, D.; Fried-Oken, M. Noninvasive Brain–Computer Interfaces for Augmentative and Alternative Communication. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2014, 7, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.