Abstract

Background: Simulation-based laparoscopic training increasingly relies on portable, low-cost platforms that support home-based practice, but detailed descriptions of reproducible, do-it-yourself (DIY) trainers and their educational potential remain limited. Methods: We updated a low-budget laparoscopic simulator constructed from an inexpensive plastic container, wood components, a low-cost webcam, and plywood task pads modeled on Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) exercises. We then conducted informal qualitative usability testing in which 10 residents and 5 fellows from general surgery, gynecology, and urology used the simulator at home for one week and completed an eight-item feedback form plus free-text comments on assembly, ergonomics, realism, and educational value. Results: All participants successfully assembled and used the simulator; most described set-up as easy or intuitive, reported adequate image quality and lighting, and considered the platform useful for practicing depth perception, bimanual coordination, and cutting and suturing tasks. Feedback emphasized low cost, portability, and cross-specialty applicability, with only minor suggestions such as adjustable camera height or increased base weight. Conclusions: This DIY laparoscopic simulator could be assembled and used in a home-based setting, and trainees reported favorable usability and perceived educational value. More structured validation studies addressing face, content, and construct validity are needed to define its potential role within contemporary surgical curricula.

1. Introduction

Simulation-based education is now integral to laparoscopic training across general surgery, gynecology, and urology, allowing repetitive practice in a safe environment while reducing the initial learning curve in a pressure-free setting, outside the operating room, with no safety issues [1,2,3]. Over the past years, several reports have emphasized the value of portable and affordable simulators for skills acquisition, highlighting how access to low-barrier training tools can democratize surgical education and foster independent practice at home [4,5].

Recent multi-specialty “boot camp” initiatives underscore this shift toward blended, continuity-of-practice models. In a national program that provided each incoming resident with a personal laparoscopy trainer and basic instruments for take-home use, most participants rated the course highly and anticipated meaningful educational impact; notably, over 70% reported that having a simulator at home would support ongoing skills acquisition [6]. These findings highlight the practicality and perceived value of portable trainers for sustained practice beyond a single course or center, and they align with the growing emphasis on early, cross-disciplinary exposure to minimally invasive skills.

Evidence also supports the educational potential of affordable, task-based platforms: studies in box-trainer and low-cost model environments show that foundational tasks (e.g., peg transfer, pattern cutting, intracorporeal knot tying) can discriminate by experience level and lend themselves to structured assessment, thereby enabling progressive training pathways [7]. Inexpensive, procedure-specific silicone models have demonstrated face, content, and construct validity within introductory curricula, strengthening the argument that accessible simulators, when paired with basic metrics such as time, errors, and global rating scales, can deliver meaningful learning and assessment opportunities [8,9].

Crucially, feasibility extends to the home setting. Prior work on take-home simulation has shown that residents can reach high proficiency on core tasks without continuous in-lab supervision, making distributed, learner-paced practice a realistic adjunct to formal curricula and easing dependence on busy simulation centers [10,11,12,13,14,15]. These data support the concept that a compact, low-cost trainer—combined with simple, standardized tasks—can enable consistent practice despite variable schedules and resources.

Against this backdrop, we present an updated, do-it-yourself (DIY) laparoscopic trainer that can be built from readily available materials and used at home for basic skills practice. Building on our 2022 description, we (I) provide refined, step-by-step construction instructions; (II) report formative, qualitative feedback from general surgery residents and fellows after one week of home use, focusing on usability, realism, and educational potential; and (III) outline a pragmatic, literature-informed roadmap for future formal validation addressing face, content, and construct validity across novice, intermediate, and expert groups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Construction of the DIY Laparoscopic Simulator

The simulator was conceived as a low-cost, home-assembled trainer designed to reproduce essential laparoscopic ergonomics and tasks using readily available materials.

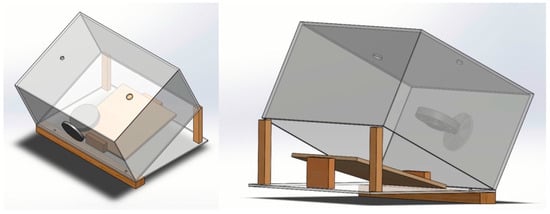

The box consists of a rigid plastic container with an opaque lid featuring two trocar entry ports positioned at a 60° angle (Figure 1). Standard 5 mm and 10 mm trocars (Medtronic Italia S.p.A., Milan, Italy) were used. A compact endoscopic camera with integrated LED illumination (30° viewing angle) provided internal visualization via a laptop or tablet (Trust International B.V., Dordrecht, The Netherlands).

Figure 1.

Low-budget laparoscopic simulator in isometric view from above and below.

All components were sourced from online or local stores and assembled with standard hand tools. Reprocessed disposable items (e.g., trocars, graspers) were obtained from hospital stock scheduled for disposal and underwent thorough cleaning and sterilization according to institutional safety guidelines. The characteristics of applied materials, their sources, and related costs are listed in Table 1. The total cost of the complete setup, including laparoscopic instruments, was €213.80. Of this amount, €170 was attributable to the laparoscopic instruments themselves, which are reusable and not specific to the trainer. The actual cost of constructing the simulator, including the container, camera, lighting system, support structure, and task pads, was therefore €43.80. This distinction highlights that the trainer can be assembled at very low cost when instruments are already available, as is often the case for trainees or training centers. To the best of our knowledge, no lower-cost laparoscopic simulators with comparable functionality are reported in the literature or commercially available, particularly when considering that many published models do not provide a detailed breakdown of material and assembly costs, limiting meaningful cost comparisons.

Table 1.

Characteristics of materials, sources, and costs.

This simulator consists of three main components: the simulation box, the simulation base and the simulation pads.

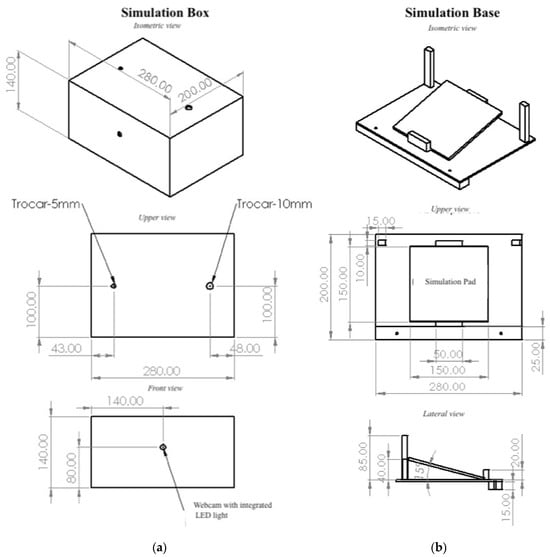

2.1.1. Simulation Box and Simulation Base

The SAMLA container (28 cm × 20 cm × 14 cm) bought from IKEA was used as a simulator box, allowing for the introduction of the trocars. Two holes were created on the top face of the SAMLA container using an electric drill. The first hole with a diameter of 5 mm was created on the median line at a distance of 43 mm from the left side whereas the second one with a diameter of 10 mm was realized on the same line at 48 mm from the right side. The trocars were positioned to achieve a 60° manipulation angle, allowing maximum efficiency in the operating field [16,17]. A third hole for the fixed camera was then realized on the front wall of the container at a distance of 80 mm from the bottom and 140 mm centrally from both sides (Figure 2a). We chose the Trust Spotlight Pro webcam as the fixed camera for its integrated LED lights. The webcam was disassembled and reassembled through the hole to be fixed. It was then connected to a laptop via cable to reproduce the video and images inside the simulation box ((we used a MacBook Pro running macOS Sequoia 15.6 and Quick Camera software, version 1.5.0 (3)).

Figure 2.

Overview of the main components of the simulator box in isometric, upper, and frontal view: (a) simulation box; (b) simulation base.

The container lid served as the simulator’s base (Figure 2b). Two 85 mm-high plywood rods were vertically fixed in the rear corners of the base using wood screws inserted from the bottom. These two rods acted as columns to rest and place the simulation box. Two plywood bases (the posterior/distal one was 40 mm high whereas the anterior/proximal one was 20 mm high) were then assembled and fixed with wood screws at a mutual distance of 150 mm. These two bases allowed the simulation pad to be blocked at an angle of 15 degrees.

The simulation box was positioned on the plywood columns (in the rear corners of the container lid) and fixed in the back at an angle of 45 degrees. In this way, the difference in inclination angles between the camera (45 degrees) and the simulation pad (15 degrees) produced a 30-degree camera viewing angle. The simulator box and the base were fixed at the front with a wooden parallelepiped, long as the lower side of the base (280 mm), using wood screws positioned from top to bottom.

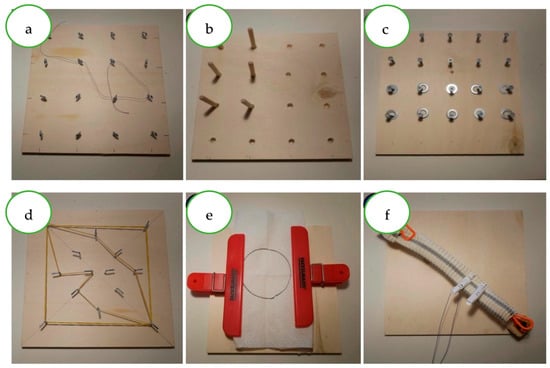

2.1.2. Simulation Pads

Many 150 mm × 150 mm plywood tablets were used as simulation pads (Figure 3). Every simulation pad was modified and adapted using several tools with the aim of performing different exercises and basic surgical maneuvers. We took inspiration from exercises proposed on YouTube or in the Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) program [18,19,20]. FLS is a standardized laparoscopic simulation course, approved by the American College of Surgeons (ACS), consisting of didactic material and manual skills serving as a basic curriculum to guide and train surgical residents for laparoscopic surgery. A Supplementary Video (Video S1: Demonstration of basic laparoscopic exercises on the DIY training pads) accompanies this article and illustrates how the pads are used to perform these fundamental tasks.

Figure 3.

Simulation Pads.

The training approach was to perform the exercises in order of difficulty, using the time to complete the exercise as an evaluation criterion:

- -

- Simulation pad N°1 (Figure 3a): The goal of the exercise is to insert the thread into the rings following a path established from the beginning.

- -

- Simulation pads N°2 and N°3 (Figure 3b,c): These pads aim to simulate the “peg transfer,” moving an object (wooden cylinders or rings) from one position to another using both left and right hands; the exercise is then repeated in the reverse direction.

- -

- Simulation pad N°4 (Figure 3d): This exercise aims to pull an elastic band to a new fixation point established from the beginning, using both left and right hands.

- -

- Simulation pad N°5 (Figure 3e): This trains the use of scissors; the goal is to cut out the circle drawn on the gauze.

- -

- Simulation pad N°5 (Figure 3f): This pad trains for multiple activities, such as placing an elastic band on a target or realizing intracorporeal sutures and anastomoses.

2.2. Informal Usability and Realism Testing

To explore the simulator’s usability and educational potential, we conducted a brief formative evaluation among 10 general surgery residents (postgraduate years 1–5) and 5 surgical fellows from multiple specialties (general surgery, gynecology, and urology). Each participant assembled or used the simulator at home for one week.

Participants were provided exclusively with written assembly instructions and illustrative diagrams, as shown in this article, and no additional guidance or direct support was offered by the authors. Communication between participants was not restricted during the home-use period, reflecting a real-world, self-directed learning setting.

Participants were encouraged to practice freely on standard tasks (peg transfer, cutting, suturing). At the end of the week, they provided short written comments and completed a concise feedback form assessing key aspects of the simulator. No personal or performance data were collected, and participation was voluntary and anonymous.

The feedback form consisted of eight short items, rated qualitatively (agree/disagree or brief comment), addressing the domains shown in Table 2. Responses were summarized descriptively without quantitative scoring. Selected anonymized quotations illustrating recurring themes were extracted for inclusion in the Results.

Table 2.

Eight-item informal feedback form used for home-based simulator evaluation.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

This activity was exempt from Institutional Review Board evaluation under the applicable European, National, and Regional regulations. The informal testing consisted solely of anonymous and voluntary educational feedback from surgical trainees about the usability of the simulator. No personal data, clinical information, identifiable material, or health-related information was collected, and no patients or clinical procedures were involved. Anonymous educational feedback does not constitute human-subject research under Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (GDPR), Italian Legislative Decree 196/2003 as amended, or the remit of the Territorial Ethics Committees of the Lazio region. All participants were verbally informed of the educational purpose of the activity and provided voluntary verbal consent.

3. Results

All fifteen participants (10 residents and 5 fellows) successfully assembled and used the simulator at home for one week. Assembly typically required less than 120 min, residents and fellows generally reported that the trainer was straightforward to assemble, with most describing the setup process as intuitive and achievable without additional guidance. All materials and tools used to assemble the simulator were easily sourced from local and online stores. The laparoscopic simulator proved to be durable and easily portable. The major difficulty was finding durable laparoscopic instruments similar to those used in the operating room. The simulation box was used recreating an operating room scenario: the computer screen was placed on a shelf aligned at face height, and the laparoscopic box was fixed on a table with a height between 64 and 77 cm. The summary of informal feedback themes is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Findings of the eight-item informal feedback form.

Overall, the simulator was well received. Approximately 80% of participants described the assembly process as “easy” or “intuitive,” and most found the workspace adequate for basic laparoscopic tasks. Several participants appreciated the opportunity for flexible, self-paced training, particularly during off-duty hours. A few suggested minor adjustments, such as adding adjustable camera height or increasing base weight to further enhance stability. A majority found the camera and integrated lighting adequate for basic tasks, with some describing the image as “clear enough to focus on technique rather than equipment.” No participant reported technical malfunctions or difficulties maintaining the setup over the week.

Perceptions of realism centered on the ability to rehearse fundamental motor skills. While users acknowledged that pads did not replicate the exact tactile properties of living tissue, most felt that the trainer provided a credible platform for practicing depth perception, bimanual coordination, and precision movements. Fellows in particular highlighted that the simulator allowed them to refine instrument handling and maintain dexterity between lab or operating room sessions.

The educational value of the simulator emerged as a recurring theme. Participants described the experience as low-pressure, convenient, and motivating, particularly because it enabled deliberate practice without scheduling constraints. Several residents reflected that they would have appreciated access to a similar tool earlier in their training, and two explicitly suggested that the model could be incorporated into introductory skills curricula for medical students or junior trainees.

Suggestions for improvement were modest and focused on refining ergonomics: a small number of users recommended adding an option to adjust the camera height or to increase the weight of the base to enhance stability during high-tension tasks. Despite these comments, the overall sentiment was that the trainer provided an unexpectedly robust platform for early laparoscopic practice, especially given its low cost and easily sourced materials.

Commonly cited strengths were its low cost, ease of replication, and versatility across specialties. Two users specifically emphasized its potential value for medical students or junior residents before attending a structured skills course.

4. Discussion

This study describes the development of a low-cost, home-assembled laparoscopic simulator and reports preliminary qualitative impressions from residents and fellows after one week of independent use. The feedback obtained suggests that a simple, portable trainer can provide meaningful opportunities for early laparoscopic practice outside the simulation laboratory. Participants appreciated the ease of assembly, the stability of the setup, and the adequacy of camera and lighting, and they highlighted the educational value of short, repeated practice sessions incorporated into daily routines. These observations are consistent with recent initiatives emphasizing early exposure to minimally invasive skills and the use of take-home simulators as components of blended training curricula [21,22].

The positive reception of this model also reinforces prior evidence showing that accessible and low-cost platforms can support introductory laparoscopic training across specialties. Studies evaluating basic laparoscopic curricula have demonstrated that simple, task-based environments can discriminate between experience levels and facilitate progressive skill acquisition, even when constructed from inexpensive materials [10,11,12,13,14,15]. In this context, low-cost DIY laparoscopic simulators have been reported to achieve comparable technical skill development to commercial systems. Taylor S. [10] found no statistically significant differences in performance between DIY and commercial box trainers across multiple laparoscopic tasks, this finding has been further supported by meta-analytic evidence indicating that simple laparoscopic trainers are equally effective for skill acquisition when compared with video-based commercial platforms [23].

Beyond effectiveness, affordability and accessibility remain key advantages of DIY solutions. Non-commercial simulators have been reported to cost substantially less than commercial systems, enabling wider dissemination and independent practice. Previous reviews have shown that, while commercial trainers achieve higher rates of formal face validation, portable low-cost simulators represent equitable and practical solutions for basic laparoscopic skills training, particularly during early learning phases [24]. In addition, learner-rated quality of homemade simulators has been reported to be comparable to that of commercial alternatives [25]. Consistent with these findings, participants in our cohort perceived the simulator as a credible environment for practicing depth perception, bimanual coordination, and basic instrument handling, and suggested potential applicability not only for general surgery but also for gynecology and urology trainees.

4.1. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the number of participants was small and the activity was designed as an informal, exploratory exercise rather than a structured validation study. Feedback was collected in an unstandardized manner and was based on subjective perceptions, without the use of validated assessment tools or objective performance metrics. No control group or comparator simulator was included, and no pre- or post-training evaluation of technical skills was performed. In addition, participants were self-selected trainees, which may have introduced selection bias. Finally, the simulator was not evaluated in relation to established curricular outcomes or training benchmarks.

These limitations are inherent to the exploratory nature of the study but nevertheless offer a useful foundation for designing a more structured validation process.

4.2. Future Perspectives

A formal validation study is the logical next step to determine the educational robustness of the simulator. A realistic approach should incorporate established frameworks assessing face, content, and construct validity, using study designs similar to those adopted in recent evaluations of basic laparoscopic skills curricula and silicone-based task models. These should be assessed by structured questionnaires administered to a diverse group of surgeons, including experts from general surgery, gynecology, and urology. Participants would evaluate the realism of the visual field, tactile feedback, ergonomics, and the appropriateness of tasks for early skills training. Semi-structured interviews or free-text responses could complement numerical ratings to capture nuanced impressions.

To determine whether the simulator can discriminate across experience levels, performance should be compared among three predefined groups:

- -

- Novices (medical students or PGY1 residents);

- -

- Intermediates (PGY3–5 residents);

- -

- Experts (fellows or attending surgeons with ≥50 laparoscopic cases).

Participants would complete a series of standardized tasks such as peg transfer, pattern cutting, and intracorporeal knot tying—tasks that have shown discriminative ability in prior simulation studies. Outcome measures would include time-to-completion, predefined error counts, and validated global performance scales such as GOALS [26]. A short test–retest protocol could additionally support assessment of reliability. Given the growing interest in take-home simulation for continuity of practice, the validation protocol could incorporate an optional home-use component. Tracking feasibility, adherence, and user satisfaction in this context would provide valuable information on whether the trainer can realistically support distributed, self-paced learning.

5. Conclusions

This low-cost, home-assembled laparoscopic simulator offers a practical and accessible platform for early skills practice across surgical specialties. In this formative experience, residents and fellows reported that the trainer was easy to assemble, stable during use, and useful for rehearsing basic laparoscopic tasks in a self-directed manner. Although these impressions do not constitute formal evidence of training efficacy, they highlight the potential educational value of simple, portable trainers, particularly in settings where access to simulation laboratories is limited. Building on these encouraging observations, a structured validation study incorporating face, content, and construct assessments is now warranted. Such work will help define the simulator’s role within contemporary surgical curricula and clarify how low-budget, DIY models can complement established simulation resources.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ime5010003/s1, Video S1: Demonstration of basic laparoscopic exercises on the DIY training pads; Figure S1: Assembled DIY laparoscopic simulator showing box layout, ports, and internal workspace.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.; methodology, M.P. and A.P.; data curation, M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.; writing—review and editing, M.P., F.L., C.R., A.P., A.A.M., P.C., C.V. and C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the regulations of the Territorial Ethics Committees (CET) in Lazio, which are defined by the Ministerial Decree of 30 January 2023, by Determination GSA n. G01659 of 10 February 2023, and by Determination n. G05811 of 28 April 2023. These regulations make clear that CETs are responsible for the ethical oversight of clinical and biomedical research involving human participants. Since the present activity does not involve human subjects, clinical research, identifiable data, or procedures requiring participant protection, it does not fall within the remit of CET review as defined by the regional system.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants after a brief explanation of the purpose of the feedback collection. No identifiable information, personal data, or images of participants were collected.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DIY | Do-It-Yourself |

| FLS | Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery |

| ACS | American College of Surgeons |

| PGY | Postgraduate Year |

| N.A. | Not Available |

| GOALS | Global Operative Assessment of Laparoscopic Skills |

References

- Aydın, A.; Ahmed, K.; Abe, T.; Raison, N.; Van Hemelrijck, M.; Garmo, H.; Ahmed, H.U.; Mukhtar, F.; Al-Jabir, A.; Brunckhorst, O.; et al. Effect of Simulation-Based Training on Surgical Proficiency and Patient Outcomes: A Randomised Controlled Clinical and Educational Trial. Eur. Urol. 2022, 81, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyltander, A.; Liljegren, E.; Rhodin, P.H.; Lönroth, H. The Transfer of Basic Skills Learned in a Laparoscopic Simulator to the Operating Room. Surg. Endosc. 2002, 16, 1324–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charokar, K.; Modi, J.N. Simulation-Based Structured Training for Developing Laparoscopy Skills in General Surgery and Obstetrics & Gynecology Postgraduates. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zendejas, B.; Brydges, R.; Hamstra, S.J.; Cook, D.A. State of the Evidence on Simulation-Based Training for Laparoscopic Surgery: A Systematic Review. Ann. Surg. 2013, 257, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, L.S.; Sherman, V.; Fried, G.M. Using Simulators to Assess Laparoscopic Competence: Ready for Widespread Use? Surgery 2004, 135, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, S.G.; Gonçalves, M.R.; Azevedo, C.; Ruivo, A.; Guidi, G.; Marinho, R.; Teles, J.P.; Domingos, A.S.; Borges, A.L.; Quintas, F.R.; et al. First Touch Course—The Impact of a Nation-Wide Boot Camp on the Transition to Surgical Residency. Updates Surg. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sroka, G.; Feldman, L.S.; Vassiliou, M.C.; Kaneva, P.A.; Fayez, R.; Fried, G.M. Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery Simulator Training to Proficiency Improves Laparoscopic Performance in the Operating Room—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Surg. 2010, 199, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackier, J.M.; Berci, G.; Paz-Partlow, M. A New Training Device for Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Surg. Endosc. 1991, 5, 158–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.R.; Marinho, R.; Reis, S.G.; Viveiros, R.; Teixeira, M.M.; Andrade, A.K.; Do Carmo Girão, M.; Rodrigues, P.P.-V.; Castelo-Branco Sousa, M. LapAppendectomy4all: Validation of a New Methodology for Laparoscopic Appendectomy Simulation and Training. Updates Surg. 2025, 77, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, T.; Ghannam, M.; Asantey, K.; Klei, J.; Olive, E.; Roach, V.A. An Early Introduction to Surgical Skills: Validating a Low-Cost Laparoscopic Skill Training Program Purpose Built for Undergraduate Medical Education. Am. J. Surg. 2021, 221, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Bhattacharya, G.; Vance, S.J.; Bistolarides, P.; Merchant, A.M. Construction and Validation of a Low-Cost Laparoscopic Simulator for Surgical Education. J. Surg. Educ. 2013, 70, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccelli, J.; Kahol, K.; Ashby, A.; Smith, M.; Ferrara, J. The Validity of Take-Home Surgical Simulators to Enhance Resident Technical Skill Proficiency. Am. J. Surg. 2011, 201, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, E.; Schwameis, R.; Louridas, M.; Göbl, C.; Kuessel, L.; Polterauer, S.; Husslein, H. Training on an Inexpensive Tablet-Based Device Is Equally Effective as on a Standard Laparoscopic Box Trainer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Medicine 2016, 95, e4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriero, D.; Atzori, G.; Barra, F.; Pertile, D.; Massobrio, A.; Conti, L.; Gusmini, D.; Epis, L.; Gallo, M.; Banchini, F.; et al. Development and Validation of a Homemade, Low-Cost Laparoscopic Simulator for Resident Surgeons (LABOT). IJERPH 2020, 17, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khine, M.; Leung, E.; Morran, C.; Muthukumarasamy, G. Homemade Laparoscopic Simulators for Surgical Trainees. Clin. Teach. 2011, 8, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, G.B.; Shimi, S.; Cuschieri, A. Influence of Direction of View, Target-to-Endoscope Distance and Manipulation Angle on Endoscopic Knot Tying. Br. J. Surg. 1997, 84, 1460–1464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muhlmann, M.D.; Rodrigues, S.J.; Wong, S.W. Ergonomic Port Placement in Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery. Color. Dis. 2012, 14, 1132–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, N.E.; Nepomnayshy, D.; De, S.; Banks, E.; Breitkopf, D.M.; Campagna, R.; Gomez-Garibello, C.; Green, I.; Jacobsen, G.; Korndorffer, J.R.; et al. What Are Essential Laparoscopic Skills These Days? Results of the SAGES Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) Committee Technical Skills Survey. Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 7676–7685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, R.M.; Turbati, M.S.; Goldblatt, M.I. Preparing for and Passing the Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) Exam Improves General Surgery Resident Operative Performance and Autonomy. Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 6438–6444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmiederer, I.S.; Kearse, L.E.; Jensen, R.M.; Anderson, T.N.; Dent, D.L.; Payne, D.H.; Korndorffer, J.R. The Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery in General Surgery Residency: Fundamental for Junior Residents’ Self-Efficacy. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 36, 8509–8514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joosten, M.; Bökkerink, G.M.J.; Verhoeven, B.H.; Botden, S.M.B.I. Evaluating the Use of a Take-Home Minimally Invasive Surgery Box Training for At-Home Training Sessions Before and During the COVID Pandemic. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2023, 33, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, M.; Hillemans, V.; Bökkerink, G.M.J.; De Blaauw, I.; Verhoeven, B.H.; Botden, S.M.B.I. The Feasibility and Benefit of Unsupervised At-Home Training of Minimally Invasive Surgical Skills. Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.; Braga, L.H.; Hoogenes, J.; Matsumoto, E.D. Commercial Video Laparoscopic Trainers versus Less Expensive, Simple Laparoscopic Trainers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Urol. 2013, 190, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.M.; George, J. A Systematic Review of Low-Cost Laparoscopic Simulators. Surg. Endosc. 2017, 31, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łysak, J.M.; Lis, M.; Więckowski, P.R. Low-Cost Laparoscopic Simulator—Viable Way of Enabling Access to Basic Laparoscopic Training for Medical Students? Surg. 2023, 21, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliou, M.C.; Feldman, L.S.; Andrew, C.G.; Bergman, S.; Leffondré, K.; Stanbridge, D.; Fried, G.M. A Global Assessment Tool for Evaluation of Intraoperative Laparoscopic Skills. Am. J. Surg. 2005, 190, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.