Abstract

Ferulic acid (FA) is well known for its antioxidant properties and neuroprotective effects. To enhance these biological activities, we designed a novel series of FA derivatives by introducing a phenyl group at the α-position of the carboxyl moiety. Further structural modifications were achieved by incorporating hydroxy or alkoxy substituents at various positions on the two aromatic rings. A series of these derivatives were synthesized and evaluated for their antioxidant capacity using the DPPH radical scavenging assay, as well as their cytoprotective effects against oxidative stress in Neuro-2a cells. Among the synthesized compounds, one derivative exhibited significantly enhanced activity in both assays. Mechanistic studies indicated that this heightened efficacy is attributable to a unique reaction pathway involving dual antioxidant mechanisms.

1. Introduction

Cerebrovascular diseases (CVDs), particularly stroke, remain one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, historically ranking as the third most common cause of death [1]. While advancements in acute medical care have significantly improved survival rates among stroke patients, stroke continues to represent a significant health burden due to the long-term disabilities it often causes. As such, there is a persistent and pressing need for more effective therapeutic and preventive strategies.

Stroke can be broadly classified into three types: cerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and ischemic cerebrovascular disease (cerebral infarction) [2], with cerebral infarction accounting for approximately 70% of all stroke cases [3]. Cerebral infarction typically results from thrombotic occlusion or severe narrowing of cerebral blood vessels, leading to neuronal death and metabolic disruption due to reduced oxygen and nutrient supply. These pathophysiological events frequently result in severe neurological deficits such as hemiplegia, aphasia, and sensory impairment, necessitating urgent medical intervention.

Emerging evidence suggests that, in addition to ischemia induced by thrombus formation, oxidative stress caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) plays a pivotal role in the onset and progression of cerebral infarction [4,5]. Current acute-phase treatments, such as thrombolytic therapy [6,7] and neuroendovascular interventions [8,9], aim to restore cerebral blood flow. However, these treatments often lead to secondary damage due to reperfusion injury, predominantly mediated by oxidative stress [10,11].

At present, edaravone [12] is the only clinically approved antioxidant drug used to mitigate oxidative stress associated with cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. However, its application is severely limited—it is unsuitable for long-term use, cannot be prescribed prophylactically, and is contraindicated in patients with renal dysfunction [13]. Given the prevalence and unpredictability of CVD in daily life [14,15], there is a critical demand for safer, more versatile antioxidant compounds that could be used both therapeutically and preventively.

To address this need, our research has focused on ferulic acid—a naturally occurring phenolic compound found in members of the Poaceae family and in tomatoes—due to its broad pharmacological properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anti-glycation, neuroprotective, and anti-dementia effects [16,17,18,19]. Previous in vivo and in vitro studies have demonstrated that ferulic acid confers a certain degree of neuroprotection in models of cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury, likely attributable to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic mechanisms [20,21]. However, the magnitude of these protective effects has been relatively modest.

It is also well recognized that biologically important antioxidants act not only as radical scavengers but also by activating endogenous defense pathways such as the NRF2/KEAP1 signaling cascade, which enhances cellular resilience to oxidative stress [22]. Based on these insights, we aimed to design and synthesize new ferulic acid derivatives with enhanced and sustained antioxidant and neuroprotective potential.

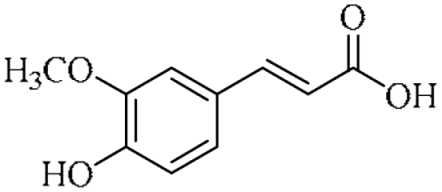

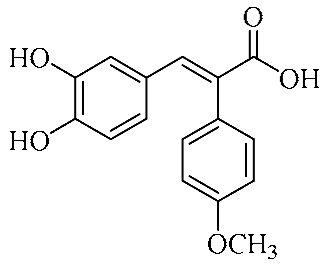

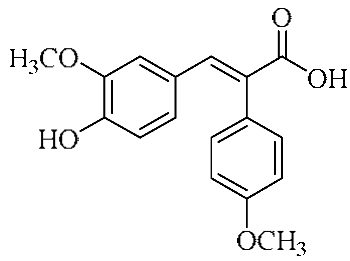

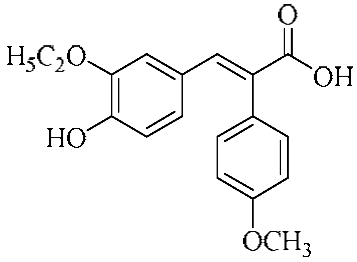

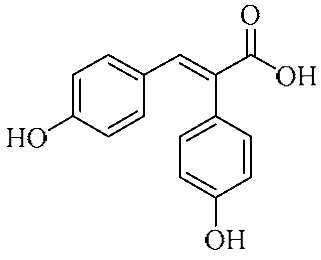

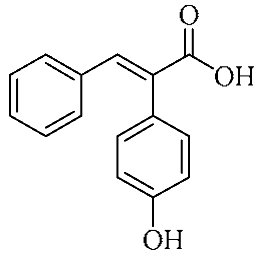

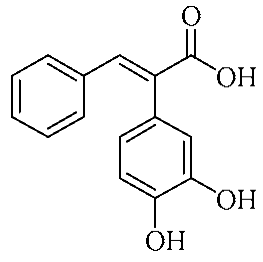

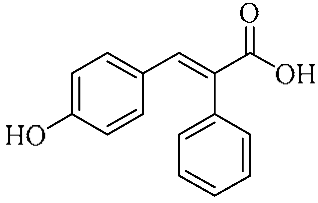

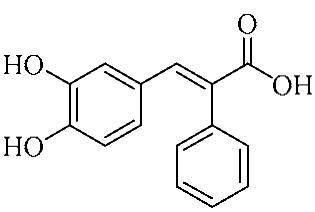

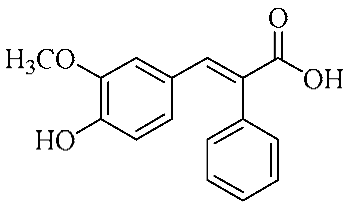

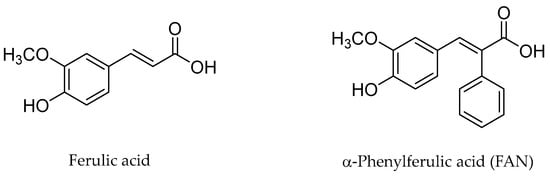

In an effort to enhance these bioactivities, we have synthesized approximately 100 derivatives of ferulic acid over the past several years [23,24]. It is well-established that the antioxidant properties of ferulic acid are primarily mediated by its phenolic hydroxyl group [16,25], which can stabilize the resulting phenoxyl radical via resonance following ROS scavenging. Based on this mechanistic insight, we designed a novel class of ferulic acid derivatives (FAN) by introducing a phenyl group at the α-position of the carboxyl moiety, thereby extending the conjugated system and potentially enhancing resonance stabilization (see Figure 1). While several α-phenyl ferulic acid derivatives have been previously synthesized, their biological evaluations have largely focused on antimicrobial and general pharmacological properties [26,27]. To our knowledge, no comprehensive structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies have been conducted with respect to their antioxidant capacity and cytoprotective effects under oxidative stress conditions.

Figure 1.

Structures of ferulic acid and α-phenylferulic acid.

Accordingly, our current work is aimed at synthesizing a series of α-phenyl ferulic acid derivatives, systematically modified by introducing hydroxyl and alkoxy substituents at various positions on both aromatic rings. We are evaluating the antioxidant potential of these compounds using two complementary approaches: (1) the DPPH radical scavenging assay to assess chemical antioxidant activity, and (2) a cellular model using Neuro-2a cells to evaluate cytoprotective effects against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemistry

2.1.1. Reagents and Instruments for the Synthesis of FANs

1H NMR spectra were recorded at 400 MHz, 13C NMR spectra at 100 MHz, and 19F NMR spectra at 376 MHz on a Bruker AVANCE NEO 400 spectrometer (Bruker Corporation, Yokohama-city, Kanagawa, Japan) using acetone-d6 as the solvent. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in ppm relative to the solvent signal, and coupling constants (J) are given in hertz (Hz). IR spectra were recorded using a Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrophotometer (IRAffinity-1, Shimadzu, Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto, Japan). Since all samples were in the solid state, the measurements were carried out using the KBr pellet method with potassium bromide (KBr) as the matrix. High-resolution and low-resolution mass spectra were obtained at the Microanalytical Laboratory of Josai University using electron impact (EI) ionization on a JEOL JMS-700 mass spectrometer (JEOL Ltd., Akishima-city, Tokyo, Japan). Elemental analyses were carried out at the same laboratory using a JSL MicroCorder JM11 (J-Science Lab Co., Ltd., Minami-ku, Kyoto, Japan, Yanaco Technical Science Co., Ltd., Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan). Flash column chromatography was performed on silica gel 60 N (40–50 μm, spherical, neutral; Kanto Chemical Co., Inc., Chūo-ku, Tokyo, Japan). Unless otherwise specified, all reagents and solvents were of reagent grade and used as received from commercial suppliers without further purification. Reported yields refer to recrystallized products.

2.1.2. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay [28]

The radical scavenging activity of FAN was evaluated using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH, Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Chūo-ku, Tokyo, Japan) assay, with ferulic acid (FA, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as a reference compound. FA and 17 FAN derivatives were adjusted to final concentrations of 0.005–1.500 mM and used for the assay. Each sample was mixed with an equal volume of 0.1 mg/mL DPPH solution in 96-well plates and incubated for 30 min in the dark at 25 °C. Absorbance was measured at 525 nm with a microplate reader (SpectraMax Pro M5e, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). The radical scavenging activity of each compound was determined as the concentration that produced a 50% reduction in DPPH radicals (EC50).

2.2. Biology

2.2.1. Cell Culture [29]

Mouse neuroblastoma Neuro-2a cells (IFO5008, Lot No. 03152018, JCRB Cell Bank, Izumisano-city, Osaka, Japan) were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Nichirei Biosciences, Chūo-ku, Tokyo, Japan), 1% non-essential amino acids (NEAA; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Miyazaki-city, Miyazaki, Japan), and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Miyazaki-city, Miyazaki, Japan). Cells were maintained in 10 cm culture dishes (Falcon, REF 353003; Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. For experiments, cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates (Cat. No. 655180; Greiner Bio-One GmbH, Kremsmünster, Austria), and assays were performed 2 days after seeding.

2.2.2. Evaluation of Cytoprotective Effects Under Oxidative Stress [23]

Oxidative stress was induced by treating cells with 120 μM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Miyazaki-city, Miyazaki, Japan) for 9 h. This concentration was selected based on preliminary tests (100–200 μM), where 120 μM produced approximately 50% cell viability and yielded a relatively stable oxidative injury [30,31,32]. Injury caused by H2O2 treatment may vary depending on culture conditions. To minimize variation, H2O2 was freshly prepared and added within 5 min after preparation, and experimental conditions were kept as consistent as possible. Data were normalized to the control group on the same plate. Test compounds were applied 1 h prior to H2O2 exposure, resulting in final concentrations of 1.25–100 μM during the oxidative stress period. Cell viability was then determined using the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Cat. G7571, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, an equal volume of reagent was added to the culture medium in each well. After incubation for 10 min at room temperature, luminescence was measured with a microplate reader (SpectraMax M5; Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). Relative viability was expressed as the luminescence of each treatment group normalized to that of the untreated control group.

2.2.3. Statistical Analysis

All results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Each experiment was performed independently at least three times. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test with GraphPad Prism (version 10.1.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of Ferulic Acid Derivatives (FAN)

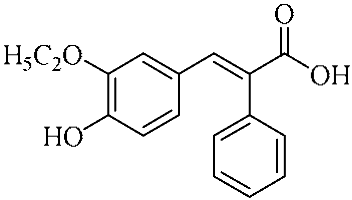

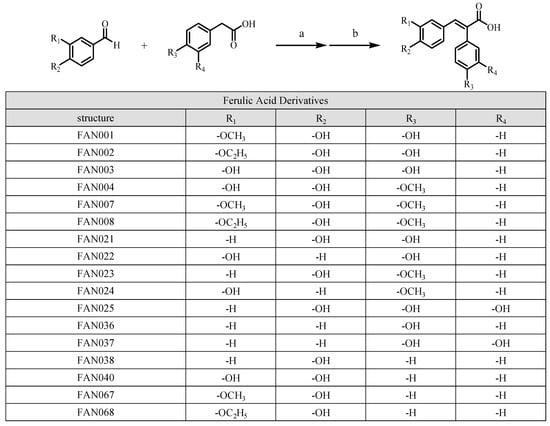

Showing the synthetic route and the structure of the synthesized FAN (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Syntheses of FANs (table of derivatives). General synthetic routes to ferulic acid derivatives: (a, Perkin reaction) Et3N, Ac2O, 90 °C, 5 h. (b, deacetylation) KOH solution, 0 °C, 1 h.

All of the synthesized compounds are (E)-2,3-diphenylprop-2-enoic acid derivatives. The synthesis of these compounds was achieved via the Perkin reaction, a well-established method that preferentially yields the E-isomer. This reaction involves the condensation of an aromatic aldehyde with an acetic acid derivative, with the E-configuration being the dominant product due to the steric and electronic factors inherent to the reaction mechanism [27,33]. All instrumental data and the purity of the synthesized FAN are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

3.2. Antioxidant Activity Evaluation by DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Ability Measurement

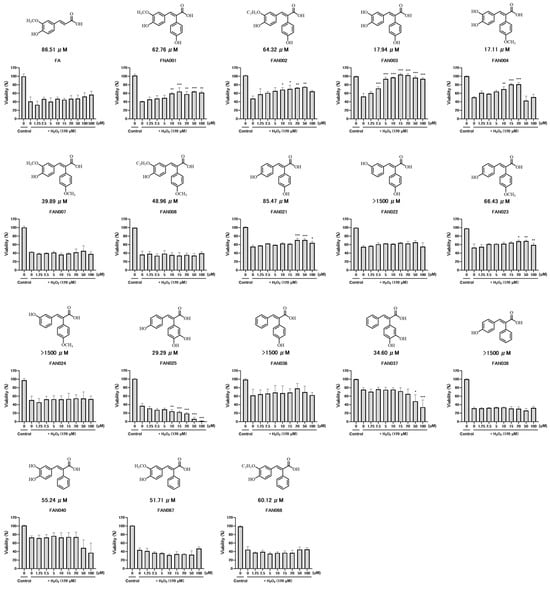

Table 1 and Figure 2 summarize the antioxidant activity of the synthesized ferulic acid derivatives (FAN001–FAN068), as evaluated by their DPPH free radical scavenging capacity, expressed as EC50 values (μmol/L). Ferulic acid (FA) was used as the reference compound, displaying an EC50 of 86.51 μmol/L. Compounds for which the EC50 exceeded 1500 μmol/L were considered inactive under the experimental conditions, as they did not exhibit measurable scavenging activity even at the highest tested concentrations.

Table 1.

EC50 (μmol/L) in FA and FA derivatives by DPPH assay.

Figure 2.

Cytoprotective effect assay against oxidative stress. Neuro-2a cells were pretreated with FAN derivatives (1.25–100 μM) for 1 h, followed by exposure to 120 μM H2O2 for 9 h. Cell viability was determined using the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay. Relative viability was calculated as the luminescence ratio of each treatment group to that of untreated controls. Data are presented as means ± S.E.M. (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test: +, p < 0.05; ++, p < 0.01; +++, p < 0.001 vs. H2O2 alone; n.s., not significant (p ≥ 0.05).

Of the seventeen representative compounds evaluated, thirteen demonstrated measurable antioxidant activity. However, four derivatives—FAN022, FAN024, FAN036, and FAN038—did not exhibit any significant radical scavenging activity. Notably, both FAN036 and FAN038 contain hydroxyl substituents, which are generally associated with enhanced antioxidant potential due to their ability to donate electrons and stabilize free radicals. Despite this, neither compound showed appreciable activity, suggesting that the presence of hydroxyl groups alone is insufficient to confer antioxidant properties.

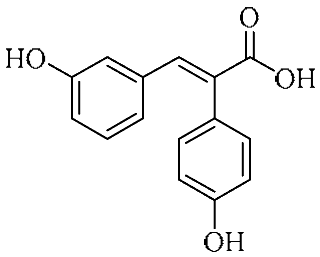

Similarly, FAN022 and FAN024, both bearing two hydroxyl groups, also failed to exhibit antioxidant activity. In contrast, their structural isomers, FAN021 and FAN023, demonstrated significant activity, with EC50 values of 85.46 μmol/L and 66.43 μmol/L, respectively. These findings highlight the critical importance of the positional arrangement of substituents rather than merely their number.

The structure–activity relationship (SAR) analysis based on these results suggests that the spatial orientation of functional groups, particularly hydroxyl and alkoxy substituents, plays a decisive role in determining antioxidant efficacy. Specifically, the presence of electron-donating groups at the para-position of both the left and right aromatic rings appears to be a key structural feature necessary for optimal radical scavenging activity.

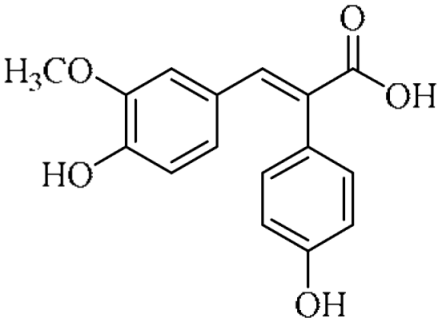

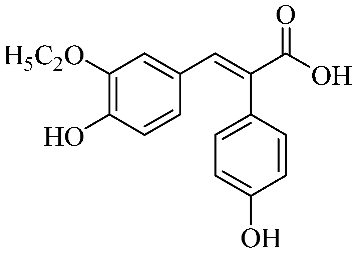

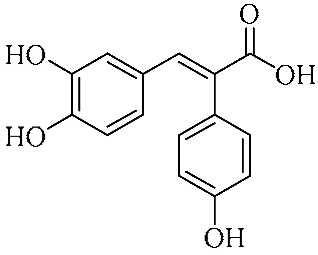

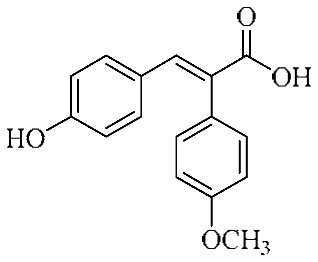

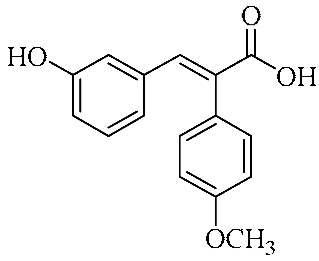

Among the synthesized derivatives, FAN067 (59.51 μmol/L) and its structural analogue FAN068 (62.53 μmol/L), both incorporating a phenyl group at the α-position of ferulic acid to generate a 2,3-diphenylprop-2-enoic acid core, exhibited enhanced antioxidant activity compared to the parent compound (FA). Further modification by introducing a hydroxyl group at the para-position of the α-phenyl ring yielded FAN001 (62.75 μmol/L) and FAN002 (64.32 μmol/L), which showed comparable radical scavenging abilities.

Interestingly, substitution with a methoxy group at the same para-position in FAN007 (48.46 μmol/L) and FAN008 (51.59 μmol/L) resulted in even greater antioxidant activity than their hydroxy-substituted counterparts. These findings suggest that the extension of conjugation via α-aryl substitution significantly enhances antioxidant activity, and that electron-donating alkoxy groups may further augment this effect.

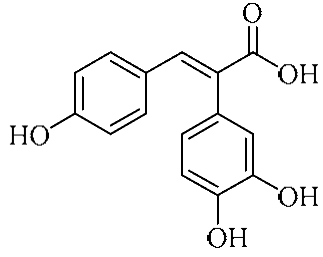

To investigate the influence of catechol moieties, the methoxy groups in FAN067 and FAN068 were replaced with hydroxyl groups at adjacent positions to create a catechol-containing structure, resulting in FAN040 (51.29 μmol/L). This compound demonstrated comparable activity to FAN067 and FAN068, indicating that the introduction of a catechol ring does not inherently reduce activity.

Subsequent substitution of FAN040 with either a hydroxy or methoxy group at the para-position of the α-phenyl group led to the synthesis of FAN003 and FAN004, respectively. These derivatives exhibited significantly improved antioxidant activity, with EC50 values of 17.94 μmol/L (FAN003) and 17.11 μmol/L (FAN004)—markedly lower than those of their precursors. These results suggest a synergistic effect between the catechol group on the ferulic acid core and para-substituted aromatic modifications.

Despite the similarity in chemical structure, the six derivatives bearing a 4-hydroxy-3-alkoxy substitution pattern—FAN067, FAN068, FAN001, FAN002, FAN007, and FAN008—showed relatively comparable antioxidant activity, ranging between 48–64 μmol/L. In contrast, the incorporation of a catechol unit, as in FAN003 and FAN004, conferred significantly greater activity, indicating that catechol functionality plays a critical role in enhancing radical scavenging capacity.

To further explore the contribution of the catechol moiety on the α-phenyl substituent, structural isomers of FAN040 and FAN003 were synthesized, wherein the catechol structure was introduced specifically on the α-phenyl ring, yielding FAN037 and FAN025, respectively. FAN037 exhibited an EC50 of 34.60 μmol/L, while FAN025 showed an EC50 of 30.45 μmol/L. Although both compounds demonstrated greater activity than FAN040 (51.29 μmol/L), their activity remained lower than FAN003 (17.94 μmol/L), suggesting that the position of the catechol moiety on the FA scaffold plays a critical role in optimizing antioxidant function.

Overall, FAN003 and FAN004 emerged as the most potent radical scavengers among the compounds tested. Their superior performance implies the presence of a unique structural feature or synergistic electronic effect that substantially enhances antioxidant efficacy, warranting further mechanistic investigation.

3.3. Biological Experiment

3.3.1. Evaluation of Cytoprotective Effects Against Oxidative Stress in Neuro-2a Cells

Following the chemical evaluation of antioxidant activity via the DPPH assay, the next phase of this study focused on assessing the cytoprotective potential of ferulic acid and 17 of its derivatives under oxidative stress conditions in neuronal cells.

Oxidative stress was experimentally induced in Neuro-2a cells by hydrogen peroxide treatment, and the protective effects of the tested compounds were evaluated based on cell viability. The survival rates of Neuro-2a cells treated with FA and selected derivatives are summarized below (see Figure 2/Table 1). This assay enabled us to assess whether the antioxidant properties observed in chemical assays correlate with biological protection at the cellular level. Although notable variations in cell viability after H2O2 exposure were observed among experiments, each compound was tested in triplicate under similar conditions, and the data were normalized to the control within the same plate.

FA has been reported, and in certain cases clinically demonstrated, to confer protective effects against ischemic cerebrovascular disease [11,12,34]. Consistent with these findings, the present study revealed that FA elicited a concentration-dependent, progressive enhancement in cell viability under conditions of oxidative stress [23]. FA showed a slight, but not statistically significant, increase in cell viability compared with the control.

Notably, six FA derivatives—FAN001, FAN002, FAN003, FAN004, FAN021, and FAN023—displayed significantly stronger protective effects than FA itself. Among these, FAN003 was particularly effective, demonstrating a pronounced improvement in cell survival. Remarkably, its protective effect was evident at concentrations as low as 2.5 μmol/L, and at concentrations above this threshold, cell viability consistently approached 100%.

By contrast, FAN037 and FAN040 markedly reduced cell viability at 50 μmol/L, while FAN025 demonstrated cytotoxic effects beginning at 10 μmol/L. These three derivatives share the structural feature of a catechol moiety, consistent with previous reports implicating catechol groups in cytotoxic mechanisms [35]. However, this correlation does not appear to be absolute: for instance, although FAN004 also possesses a catechol structure, it enhanced cell viability at low concentrations but exerted cytotoxic effects at higher concentrations.

Overall, FAN003 emerged as the most promising derivative, conferring robust cytoprotective activity without detectable cytotoxicity. Given its distinctive profile compared with other derivatives, these findings raise the possibility that FAN003 may engage an as-yet-unidentified mechanism of cellular protection.

3.3.2. Investigation of the Comprehensive Structure-Activity Relationship Between Antioxidant Activity and Cytoprotective Effect

To further elucidate structure–activity relationships, we compared data from the antioxidant activity assay (EC50) with the cytoprotective effect assay. Integration of these datasets revealed that derivatives lacking measurable antioxidant activity also failed to exhibit cytoprotective effects. Accordingly, subsequent analyses focused on compounds demonstrating antioxidant activity.

- Substituents at the α-carbon:

A comparison of FAN001, FAN007, and FAN067—each bearing different aromatic substituents at the α-carbon—suggested that introduction of phenyl groups at this position enhances the antioxidant properties of FA. Among these, FAN007, incorporating a p-anisole moiety, displayed particularly strong antioxidant activity. In contrast, FAN001, containing a p-phenol substituent, produced a more pronounced cytoprotective effect in a concentration-dependent manner. Substitution of methoxy with ethoxy groups (yielding FAN002, FAN008, and FAN067, respectively) produced trends broadly consistent with those of the parent derivatives. These findings indicate that the incorporation of a p-phenol group at the α-carbon is optimal for simultaneously enhancing both antioxidant and cytoprotective activities.

- Substituent effects on the phenyl ring of FA:

We next examined modifications on the phenyl ring of FA itself. FAN021 and FAN023, which are demethoxylated analogues of FAN007, exhibited reduced antioxidant activity relative to FAN007, yet demonstrated improved cytoprotective effects at higher concentrations. Conversely, FAN022 and FAN024, structural isomers of FAN021 and FAN023, lacked both antioxidant activity and cytoprotective effects. These results suggest that for FA derivatives to exhibit both properties, the FA phenyl ring and the α-phenyl substituent must each retain at least one hydroxy or methoxy substituent in the para position. This hypothesis is supported by the activity profiles of FAN001 and FAN002, which both include the structural motif of FAN021 and indeed displayed strong antioxidant and cytoprotective effects.

- Substituents at the meta position:

FAN001 and FAN002 both showed stronger antioxidant activity than FAN021, suggesting that substituents at the meta position of the FA phenyl ring influence activity. To explore this, we compared FAN003, FAN004, and FAN040 with FAN001 and FAN002. FAN003, a derivative containing the structural core of FAN021 with an additional hydroxy group at the meta position (forming a catechol structure), demonstrated outstanding antioxidant and cytoprotective activities, surpassing FAN001. However, its structural isomer, FAN025—bearing a catechol structure on the α-phenyl substituent—proved strongly cytotoxic despite containing the same core scaffold. This finding highlights that the position of the catechol group is critical in determining whether it contributes to cytoprotection or cytotoxicity.

FAN004, which incorporates the structure of FAN023 along with a catechol motif, displayed antioxidant activity comparable to FAN003, but its cytoprotective effect was markedly weaker. In contrast, FAN040, which also contains a catechol structure but lacks a para substituent on the α-phenyl group, exhibited diminished antioxidant activity relative to FAN003 and FAN004. Moreover, FAN040 failed to show cytoprotective activity and was cytotoxic at higher concentrations.

- Structure–activity relationship summary:

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the presence of a catechol group generally enhances antioxidant activity in FA derivatives. However, robust cell viability requires the additional presence of a substituent in the para position of the α-phenyl group. While these structural determinants account for much of the observed activity profile, the exceptionally strong dual antioxidant and cytoprotective properties of FAN003 cannot be fully explained within this framework, suggesting the possibility of an additional, as yet unidentified, protective mechanism.

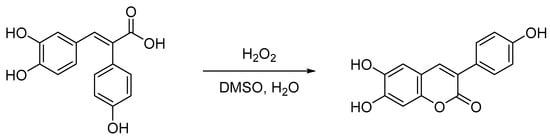

As a further line of investigation, we examined an intriguing phenomenon observed during cytoprotective assays. Specifically, a distinct color change in the culture medium was noted exclusively in the presence of FAN003, which was subsequently confirmed to be attributable to fluorescence. To elucidate the origin of this fluorescence, FAN003 was exposed to H2O2 under conditions mimicking the cell culture experiments. This treatment led to the conversion of FAN003 into a coumarin derivative (Scheme 2). In the absence of cells, the reaction proceeded relatively slowly, with preliminary data indicating a 38% conversion to the coumarin product after 24 h. The reaction employed a stoichiometric ratio of 1 equivalent FAN003 to 10 equivalents H2O2, suggesting that the reaction may persist under prolonged exposure to oxidative conditions.

Scheme 2.

Syntheses of coumarin derivative (FAN003-C) from FAN003.

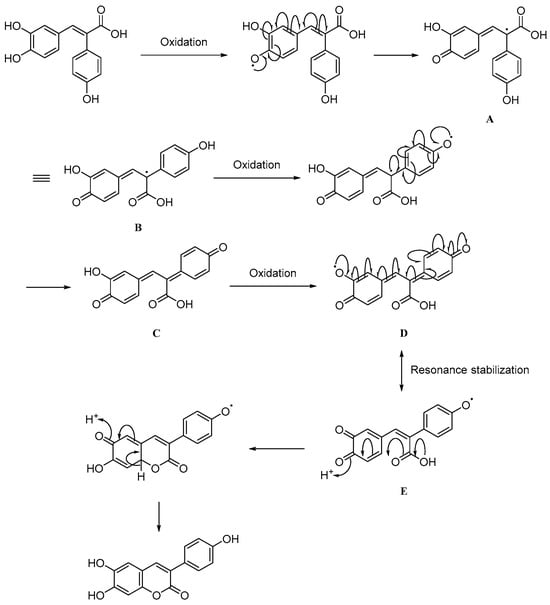

We next examined whether this transformation was unique to FAN003 by testing all other FA derivatives under identical conditions. None of the other derivatives underwent conversion to a coumarin derivative, indicating that FAN003 follows a specific and structurally dependent reaction pathway. To rationalize this unique phenomenon, we propose a mechanistic hypothesis, illustrated in Figure 3. The pathway begins with the oxidation of FAN003 to generate intermediate A, then the α-β single bond of A subsequently rotates to afford intermediate B. This change is favored due to steric hindrance imposed by the two benzene rings, driving the system toward a more stable conformation. The para-hydroxyl group on the α-phenyl substituent of B is then oxidized to yield the stilbene-quinone intermediate C. Further oxidation of the remaining phenolic hydroxyl group produces resonance-stabilized intermediates D and E, which ultimately undergo intramolecular cyclization to form the coumarin derivative, designated FAN003-C. Of all the derivatives synthesized, only FAN003 possesses the structural features necessary to access intermediates D and E. Specifically, both a catechol motif on the FA phenyl ring and a para-hydroxy substituent on the α-phenyl group are required for this reaction sequence to proceed.

Figure 3.

Proposed mechanism of conversion of FAN003-C from FAN003.

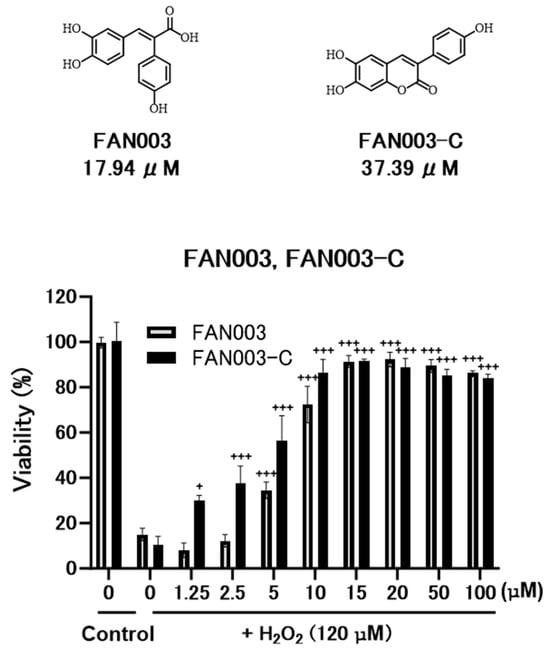

Accordingly, we proceeded to evaluate the antioxidant activity of FAN003-C using the DPPH radical scavenging assay, as well as its cytoprotective effects against oxidative stress in Neuro-2a cells.

As shown in Figure 4, FAN003-C exhibited substantial antioxidant activity, although its potency was lower than that of the parent compound, FAN003. In terms of cytoprotective effects, FAN003-C demonstrated a protective response at a lower concentration than FAN003. Based on preliminary observations, FAN003 and FAN003-C showed no apparent cytotoxicity up to 1.25–20 μM, whereas a modest decrease in viability was observed at ≥20 μM. The maximal cytoprotection under H2O2 occurred within this 10–20 μM range, suggesting that the observed effects were not artifacts of basal cytotoxicity or other nonspecific cellular responses.

Figure 4.

Top: Structure of FAN003 and FAN003-C with the results of DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay. Bottom: Graph of Cytoprotective Effects Against Oxidative Stress. Neuro-2a cells were treated with FAN003 or FAN003-C (1.25–100 μM) for 1 h prior to 9 h exposure to 120 μM H2O2. Cell viability was assessed using the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay. Relative viability was expressed as the luminescence ratio of treated to untreated control groups. Data represent means ± S.E.M. (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. +, p < 0.05; +++, p < 0.001 vs. H2O2 alone; n.s., not significant (p ≥ 0.05).

FAN003 undergoes gradual oxidative conversion to its coumarin derivative, FAN003-C, with both species retaining antioxidant and cytoprotective activities. If a comparable time-dependent transformation occurs in vivo, FAN003 may afford sustained antioxidant protection extending into the delayed phase of ischemic injury. This pharmacodynamic profile contrasts with that of edaravone—the only clinically approved antioxidant-type neuroprotectant—which requires administration within 24 h of stroke onset and whose long-term use is constrained by serious adverse effects. A compound such as FAN003, capable of maintaining protective efficacy over extended periods with a favorable safety margin, could therefore address these limitations and mitigate the progression of delayed neuronal death [36,37].

Most small-molecule antioxidants are irreversibly consumed following radical scavenging and require regeneration by auxiliary redox systems to sustain activity. In contrast, cascade-type antioxidants, in which the parent molecule is converted into an active metabolite that independently retains antioxidant capacity, are uncommon. The observed FAN003 → FAN003-C transformation thus represents a distinctive example of such a cascade antioxidant mechanism, potentially enabling prolonged neuroprotection under persistent oxidative stress conditions [38,39,40,41,42,43].

It should be noted, however, that the present findings are limited to in vitro evaluations employing chemical assays and Neuro-2a cell models. Future investigations are warranted to determine whether the protective effects of FAN003 translate to in vivo systems and to comprehensively assess its pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and overall safety [37]. Such studies will be essential to evaluate the therapeutic potential of FAN003 as a candidate for cerebrovascular disease intervention.

The discrepancy between chemical and cellular antioxidant activities may arise from differences in cell permeability, intracellular distribution, and compound stability, which collectively influence the compound’s interactions with redox-sensitive targets.

Although intracellular oxidative markers such as ROS, GSH, and MDA were not examined in this study, we acknowledge this as an important limitation. Further validation using these assays is currently underway in our laboratory.

The dose–response profiles of FAN003 and FAN003-C indicate a context-dependent, biphasic (hormetic) pattern typical of phenolic antioxidants, displaying cytoprotection at lower concentrations and decreased viability at higher doses [44,45,46].

This study mainly focused on the radical-scavenging properties of FAN derivatives. Further work will be needed to determine whether these compounds also modulate endogenous antioxidant defense pathways such as NRF2/KEAP1 [22].

This study primarily focused on the DPPH radical scavenging assay as a representative chemical method for evaluating antioxidant activity. However, other complementary assays, such as ABTS, ORAC, and FRAP, are widely employed to provide a broader understanding of radical-scavenging capacity [47]. Future studies will integrate multiple assay systems to further elucidate the antioxidant profiles and structure–activity relationships of FAN derivatives.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we selected ferulic acid (FA) as a lead compound due to its well-documented antioxidant properties and subsequently designed derivatives by introducing a phenyl substituent at the α-position of the carboxyl moiety to enhance its functionality. A series of derivatives were synthesized by varying the position and nature of hydroxy or alkoxy substituents on the two aromatic rings.

Comprehensive evaluation of these derivatives using two complementary assays—the DPPH radical scavenging assay and a cytoprotective assay against oxidative stress in Neuro-2a cells—led to the identification of FAN003 as a particularly potent compound. Further investigation revealed that the exceptional activity of FAN003 arises from a unique oxidative transformation pathway. Under conditions mimicking the cytoprotective assay (i.e., in the presence of hydrogen peroxide), FAN003 undergoes structural conversion to yield a coumarin derivative, FAN003-C. This transformation product was confirmed to retain both antioxidant activity and cytoprotective effects, thereby establishing that FAN003 exerts its biological activity through a sequential process: initial oxidation followed by structural rearrangement and a second oxidation to generate the active coumarin species.

Looking forward, further studies will be directed toward quantifying the conversion dynamics of FAN003 to FAN003-C in cellular environments and conducting detailed toxicity assessments to establish safety profiles. Collectively, these findings position FAN003 as a novel class of compounds with therapeutic potential, and they provide a framework for the rational design of safer and more efficacious derivatives for both preventive and therapeutic applications in CVDs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/appliedchem5040037/s1, Table S1: Purity data of FANs; Figure S1: Chart of HPLC of FANs for purity test; Synthesis and various instrument data of FANs; Figure S2: 1H and 13C NMR chart of FANs.

Author Contributions

J.T., T.S. and M.X. conceived the project and supervised this study. K.S. conducted the experiments, synthesized of FANs, DPPH assay, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. M.X. conducted and advised with cytoprotective effect assay, DPPH assay and data analysis. H.M., B.Y. and M.O. helped to analyze biological data. T.S. and H.T. designed of FANs. J.T. evaluated the results, revised the manuscript, and finalized the submission. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI, grant number 20K16531, 24K10604, awarded to M.X.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available within this article and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the valuable contributions of Yuta Muraoka and Takuma Okusawa, who performed experiments as part of their undergraduate research. We would like to thank Aeri Park for assistance with preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CVDs | cerebrovascular diseases |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| FA | ferulic acid |

| FAN | ferulic acid derivative |

| SAR | structure–activity relationship |

| NMR | nuclear magnetic resonance |

| FT-IR | fourier transform infrared |

| DPPH | 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl |

| MEM | minimum essential medium |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| NEAA | non-essential amino acids |

| NEt3 | triethylamine |

| Ac2O | acetic anhydride |

| mp | melting point |

| DMSO | dimethylsulfoxide |

| EC50 | 50% effective concentration |

References

- Naghavi, M.; Ong, K.L.; Aali, A.; Ababneh, H.S.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasgholizadeh, R.; Abbasian, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; et al. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2100–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y. Special report from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Classification of cerebrovascular diseases III. Stroke 1990, 21, 637–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syme, P.D.; Byrne, A.W.; Chen, R.; Devenny, R.; Forbes, J.F. Community-based stroke in a Scottish population: The Scottish Borders Stroke Study. Stroke 2005, 36, 1837–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.H. Reactive Oxygen Radicals in Signaling and Damage in the Ischemic Brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2001, 21, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.L.; Bayraktutan, U. Oxidative stress and its role in the pathogenesis of ischaemic stroke. Int. J. Stroke 2009, 4, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 333, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Mori, E.; Minematsu, K.; Nakagawa, J.; Hashi, K.; Saito, I.; Shinohara, Y.; on behalf Japan Alteplase Clinical Trial (J-ACT) Group. Alteplase at 0.6 mg/kg for Acute Ischemic Stroke Within 3 Hours of Onset: Japan Alteplase Clinical Trial (J-ACT). Stroke 2006, 37, 1810–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.S.; Ko, S.B.; Lee, J.S.; Yu, K.H.; Rha, J.H. Endovascular Recanalization Therapy in Acute Ischemic Stroke: Updated Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Stroke 2015, 17, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Menon, B.; van Zwam, W.H.; Dippel, D.W.J.; Mitchell, P.J.; Demchuk, A.M.; Davos, A.; Majoie, C.B.L.M.; van der Lugt, A.; de Miquel, M.A.; et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: A meta-analysis of individual patient date from five randomized trials. Lancet 2016, 387, 1723–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeris, T.; Baines, C.P.; Krenz, M.; Korthuis, R.J. Cell Biology of Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 298, 229–317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eltzsching, H.K.; Eckle, T. Ischemia and reperfusion-from mechanism to translation. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otomo, E.; Tohgi, H.; Kogure, K.; Hirai, S.; Takamura, K.; Terashi, A.; Gotoh, F.; Maruyama, S.; Tayaki, Y.; Shinohara, Y.; et al. Effect of a novel free radical scavenger, edaravone (MCI-186), on acute brain infarction: Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study at multicenters. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2003, 15, 222–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zamami, Y.; Sagara, H.; Kayano, Y.; Koyama, T.; Shiraishi, N.; Esumi, S.; Ugawa, T.; Sendo, T.; Ujike, Y.; Nakamura, H. Risk factor of acute renal failure induced by edaravone in patients with cerebrovascular disorder. J. Jpn. Soc. Emerg. Med. 2016, 19, 461–465. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, K.J.; Quintanilha, A.T.; Brooks, G.A.; Packer, L. Free radicals and tissue damage produced by exercise. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1982, 107, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, F.; Kagawa, Y.; Sakuma, M.; Kawabata, T.; Kaneko, Y.; Otgontuya, D.; Chimedregzen, U.; Narantuya, L.; Purvee, B. Investigation of oxidative stress and dietary habits in Mongolian people, compared to Japanese people. Nutr. Metab. 2006, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, E. Antioxidant potential of Ferulic acid. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 1992, 13, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, M.; Sudheer, A.R.; Menon, V.P. Ferulic Acid: Therapeutic Potential Through Its Antioxidant Property. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2007, 40, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgarbossa, A.; Giacomazza, D.; Carlo, M.D. Ferulic Acid: A Hope for Alzheimer’s Disease Therapy from Plants. Nutrients 2015, 7, 5764–5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubashini, M.S.; Rukkumani, R.; Menon, V.P. Protective effects of ferulic acid hyperlipidemic diabetic rats. Acta Diabetol. 2003, 40, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yang, H. Ferulic acid exerts neuroprotective effects against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion-induced injury via antioxidant and anti-apoptotic mechanisms in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 40, 1444–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.Y.; Su, S.Y.; Tang, N.Y.; Ho, T.Y.; Chiang, S.Y.; Hsieh, C.L. Ferulic acid provides neuroprotection against oxidative stress-related apoptosis after cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting ICAM-1 mRNA expression in rats. Brain Res. 2008, 1209, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Liu, Q.; Sha, H. The Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidant Mechanisms of the Keap1/Nrf2/ARE Signaling Pathway in Chronic Diseases. Aging Dis. 2019, 10, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano, T.; Xuan, M.; Iwata, N.; Takayama, J.; Hayashi, K.; Kato, Y.; Aoyama, T.; Sugo, H.; Matsuzaki, H.; Yuan, B.; et al. Involvement of the Restoration of Cerebral Blood Flow and Maintenance of eNOS Expression in the Prophylactic Protective Effect of the Novel Ferulic Acid Derivative FAN012 against Ischemia/Reperfusion Injuries in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugoh, H.; Matsuzaki, H.; Takayama, J.; Iwata, N.; Xuan, M.; Yuan, B.; Sakamoto, T.; Okazaki, M. FAD012, a Ferulic Acid Derivative, Preserves Cerebral Blood Flow and Blood–Brain Barrier Integrity in a Photothrombotic Stroke Model in Rats. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanski, J.; Akesnova, M.; Stoyanova, A.; Butterfield, D.A. Ferulic acid antioxidant protection against hydroxyl and peroxyl radical oxidation in synaptosomal and neuronal cell culture systems in vitro: Structure-activity studies. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2002, 13, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Park, Y.; Park, C.; Lee, S.; Kang, D.; Yang, J.; Akter, J.; Chun, P.; Moon, H.R. Antioxidant, anti-tyrosinase and anti-melanogenic effects of (E)-2,3-diphenylacrylic acid derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2019, 27, 2192–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Yan, B.; Xun, L.; Li, R.; Wang, P.; Zhao, Q. Design, synthesis, antiviral activities of ferulic acid derivatives. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1133655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, H.; Arai, A.; Xuan, M.; Yuan, B.; Takayama, J.; Sakamoto, T.; Okazaki, M. CUD003, a Novel Curcumin Derivative, Ameliorates LPS-Induced Impairment of Endothelium-Dependent Relaxation and Vascular Inflammation in Mice. Int. J Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, K.; Matsuzaki, H.; Oguchi, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Sato, M.; Yamamoto, N.; Fujita, S. Ferulic acid derivative protects Neuro2a cells from oxidative stress-induced cell death. Neurosci. Lett. 2005, 373, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffari, H.; Venkataramana, M.; Ghassam, B.J.; Nayaka, S.C.; Nataraju, A.; Geetha, N.P.; Prakash, H.S. Rosmarinic acid mediated neuroprotective effects against H2O2-induced neuronal cell damage in N2A cells. Life Sci. 2014, 113, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Xun, Y.; Liu, H.; Wei, C.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.; Yuan, S.; Liu, N.; Xiang, S. Polydatin protects neuronal cells from hydrogen peroxide damage by activating CREB/Ngb signaling. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 25, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Tan, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Shi, F.; Wang, M.; Zhang, G.; Wang, H.; Dong, R. Peroxiredoxin 1 alleviates oxygen-glucose deprivation/ reoxygenation injury in N2a cells via suppressing the JNK/ caspase-3 pathway. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2023, 26, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar]

- Perkin, W.H. XI.—On the formation of coumarin and of cinnamic and of other analogous acids from the aromatic aldehydes. J. Chem. Soc. 1877, 31, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, T.; Matsuzaki, H.; Iwata, N.; Xuan, M.; Kamiuchi, S.; Hibino, Y.; Sakamoto, T.; Okazaki, M. Protective Effects of Ferulic Acid against Chronic Cerebral Hypoperfusion-Induced Swallowing Dysfunction in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monks, T.J.; Hanzlik, R.P.; Cohen, G.M.; Ross, D.; Graham, D.G. Quinone chemistry and toxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1992, 112, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, S.; Ogasawara, K.; Kuroda, S.; Itabashi, R.; Toyoda, K.; Itoh, Y.; Iguchi, Y.; Shiokawa, Y.; Takagi, Y.; Ohtsuki, T.; et al. Japan Stroke Society Guideline 2021 for the Treatment of Stroke. Int. J. Stroke 2022, 17, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapchak, P.A. A critical assessment of edaravone acute ischemic stroke efficacy trials: Is edaravone an effective neuroprotective therapy? Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2010, 11, 1753–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niki, E. Interaction of ascorbate and α-tocopherol. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1987, 498, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, K.K.A.C.; Shiroma, M.E.; Damous, L.L.; de Jesus Simões, M.; Simões, R.D.S.; Cipolla-Neto, J.; Baracat, E.C.; Soares-Jr, J.M. Antioxidant actions of melatonin: A systematic review. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galano, A.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. On the free radical scavenging activities of melatonin’s metabolites AFMK and AMK. J. Pineal Res. 2013, 54, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Superti, F.; Russo, R. Alpha-Lipoic Acid: Biological Mechanisms and Health Benefits. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, M.B.; Negrato, C.A. Alpha-lipoic acid as a pleiotropic compound with potential therapeutic use in diabetes and other chronic diseases. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2014, 6, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcox, C.S. Effects of tempol and redox-cycling nitroxides in models of oxidative stress. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 126, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriazis, M.; Swas, L.; Orlova, T. The Impact of Hormesis, Neuronal Stress Response, and Reproduction, upon Clinical Aging: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, V.; Cornelius, C.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Calabrese, E.J.; Mattson, M.P. Cellular Stress Responses, The Hormesis Paradigm, and Vitagenes: Novel Targets for Therapeutic Intervention in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 13, 1763–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carocho, M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. A review on antioxidants, prooxidants and related controversy: Natural and synthetic compounds, screening and analysis methodologies and future perspectives. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 51, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kancheva, V.D.; Dettori, M.A.; Fabbri, D.; Alov, P.; Angelova, S.E.; Slavova-Kazakova, A.K.; Carta, P.; Menshov, V.A.; Yablonskaya, O.I.; Trofimov, A.V.; et al. Natural Chain-Breaking Antioxidants and Their Synthetic Analogs as Modulators of Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).