Abstract

Optimizing copper recovery from sulfide minerals such as chalcopyrite, which constitutes over 70% of global copper reserves, is essential due to the depletion of conventional copper oxide resources. This study aimed to establish optimal ferric leaching conditions for a chalcopyrite-rich concentrate to maximize copper recovery and to evaluate the regeneration of the oxidizing potential in the residual leaching solution for reuse. Ferric sulfate (Fe2(SO4)3), as a ferric ion (Fe3+) carrier, was used as oxidizing agents at a concentration of [0.1 M] in sulfuric acid ([0.5 M] H2SO4), using a CuFeS2 concentrate (75% chalcopyrite) leached over 80 h. Copper was recovered through cementation with metallic iron, while the residual leaching solution, containing ferrous ions, was analyzed to determine total iron content via atomic absorption spectroscopy and to assess the presence of ferrous ions through KMnO4 titration. This step was crucial, as an excess of ferrous ions would indicate a loss of oxidizing potential of the ferric ion (Fe3+). Catalytic oxidation was conducted with microporous activated carbon (30 g/L) to regenerate Fe3+ for a second leaching cycle, achieving 90.7% Fe2+ oxidation. Optimal leaching conditions resulted in 95% soluble copper recovery at 1% solids, d80: 74 μm, pH < 2, Eh > 450 mV, 92 °C, [0.5 M] H2SO4, and [0.1 M] Fe2(SO4)3. In the second cycle, the regenerated solution reached 75% copper recovery. These findings highlight temperature as a critical factor for copper recovery and demonstrate catalytic oxidation as a viable method for regenerating ferric solutions in industrial applications.

1. Introduction

Currently, the mining industry has developed processes to extract valuable minerals and elements from primary sources. In the case of copper, it is mainly obtained from copper oxides. However, as these primary sources become depleted over time, there is a growing need to explore alternative methods for copper extraction. One promising alternative is the extraction of copper from sulfide minerals, such as chalcopyrite [1]. Chalcopyrite is the most common and abundant copper sulfide mineral in the Earth’s crust, accounting for approximately 70% of global copper reserves [2]. However, due to its complex structure, chalcopyrite is considered a refractory mineral for copper recovery using conventional hydrometallurgical methods.

Chile, one of the leading mining countries in Latin America and a major producer of metallic copper, expects an increase in the production of copper concentrates from ores with high sulfur content. It is estimated that concentrates will account for 89.9% of total copper production by 2027, up from 69.2% in 2015 [3]. Sulfide minerals are typically processed using pyrometallurgical techniques due to their high refractoriness, while hydrometallurgy is employed for the treatment of lower-grade ores [4]. Hydrometallurgy is considered less environmentally damaging than pyrometallurgy, as pyrometallurgical processes generate significant amounts of pollutant gases that must be treated before being released into the atmosphere.

In the study of chalcopyrite leaching in acidic media, the use of ferric ions as oxidizing agents has been explored. These ions are derived from compounds such as ferric sulfate (Fe2(SO4)3), dissolved in acidic solutions. According to research by Liu et al. [5], a mechanism is proposed in which ferric ions act as the oxidizing agents, with the primary dissolution reaction of chalcopyrite in ferric/ferrous sulfate systems being the oxidation of chalcopyrite by ferric ions. The general chemical equations representing this dissolution are presented below [5].

CuFeS2 + 4Fe3+ → Cu2+ + 5Fe2+ + 2S0

CuFeS2 + 4H+ + O2 → Cu2+ + Fe2+ + 2S0 + 2H2O

4Fe2+ + 4H+ + O2 → 4Fe3+ + 2H2O

Chalcopyrite, with the general formula CuFeS2, has a tetragonal crystal structure in which sulfide ions are coordinated by copper or iron atoms. This structure is similar to that of sphalerite, although there is a difference in the c-lattice parameter [6,7,8]. However, chalcopyrite exhibits slow dissolution kinetics due to its composition and crystal structure. A key factor in this slow dissolution is the phenomenon of passivation, which is illustrated by the formation of a low-porosity layer of elemental sulfur on the chalcopyrite surface, as proposed by Muñoz et al. [9]. This passivation reduces the contact between the chalcopyrite and reactive ions, thus hindering further dissolution. The chalcopyrite oxidation model by Fe3+ involves the conversion of sulfur atoms in chalcopyrite from a −2 state to 0, as shown in Equation (2), resulting in the formation of an elemental sulfur layer as a byproduct. This sulfur layer acts as a passivating barrier, reducing the contact between chalcopyrite and reactive ions, thereby slowing down the dissolution process. The dissolution rate is controlled by the formation of this sulfur layer and the diffusion of ferric ions through it [10,11].

The leaching of chalcopyrite involves a series of redox reactions, with copper dissolution being significantly influenced by the redox potential. Studies [4,12,13,14] suggest that higher recovery rates are achieved under strong oxidizing conditions, particularly at redox potentials above 0.45 V. The copper leaching rate increases within a specific potential range, with some studies indicating that the dissolution rate is higher in media with potentials between 0.42 and 0.6 V [15]. However, more recent research has concluded that the leaching rate improves at potential values above 0.5 V [2,16]. The Pourbaix diagram for chalcopyrite dissolution in acidic media, highlighting the formation of various intermediate sulfides, such as bornite (Cu5FeS4), covellite (CuS), and chalcocite (Cu2S), which become progressively richer in copper, can be found in the study by Córdoba et al. [10]. Optimal conditions for copper dissolution to Cu2+ are suggested to be pH < 4 and an oxidizing redox potential (Eh) > +0.4 V. To achieve these conditions, oxidizing agents are employed, with ferric ions, typically in the form of sulfate or chloride, being commonly used.

Another crucial factor is temperature, which has a significant impact on this type of leaching. The relation between temperature and copper dissolution from chalcopyrite has been observed, with increased dissolution occurring at higher temperatures. In some studies, leaching tests conducted in a chlorinated acidic medium, where a previously sulfurized copper concentrate was leached, achieved a copper recovery of over 95% at a temperature of 100 °C [17]. It is important to note that chalcopyrite leaching is a complex process and may require specific conditions to achieve efficient copper dissolution. Factors such as temperature, lixiviant concentration, and contact time can significantly affect the effectiveness of the process.

Recent studies have highlighted the challenges associated with leaching chalcopyrite-rich concentrates, which exhibit refractory characteristics that make them difficult to process using conventional hydrometallurgical methods. The recoveries observed in existing processes are generally low. For instance, Yang [14] emphasized the crucial role of mixed potential in leaching kinetics, suggesting that optimizing this factor could improve recovery rates. Similarly, Tian [2] discussed the effects of redox potential on the leaching process, indicating that adjustments in this parameter can lead to significant improvements. Additionally, Liu [18] investigated the speciation of copper, iron, and sulfur during bioleaching, revealing that microbial interactions can influence dissolution rates, which may further impact recovery efficiency. Furthermore, it is essential to consider the environmental aspects of chalcopyrite leaching, as the use of sulfuric acid or other lixiviants can generate acidic waste that must be properly managed to avoid negative environmental impacts.

In this context, during the acid leaching of chalcopyrite, a copper and iron solution is obtained, which is then subjected to a cementation process to recover the copper. In this final step, a residual solution is produced with a high content of dissolved iron, predominantly in the form of Fe2+, along with smaller amounts of Fe3+.

The residual solution can be treated by catalytic oxidation to regenerate the oxidative potential of the solution. Fe2+ ions are oxidized to Fe3+ ions using activated carbon. The surface of the activated carbon has particular characteristics depending on the activation treatment it has undergone, and it has been shown that the functional groups present on its surface are responsible for its catalytic activity [19]. The interactions that occur in the oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ suggest a two-step mechanism. In the first step, hydrogen peroxide is formed when the carbon comes into contact with the oxygen in the aqueous solution. In the second step, the ability of the carbon to reoxidize is considered [20].

The objective of this study was to determine the optimal working conditions to achieve higher copper recovery through acid leaching using ferric ion as the oxidizing agent. Additionally, the residual solution obtained during the first leaching cycle was regenerated to be recirculated in a second cycle, with the aim of evaluating the copper recovery obtained with this recirculated leaching solution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

The leaching medium was prepared using reagent-grade sulfuric acid (PanReac, Castellar del Vallès, Spain, 98%). The oxidizing agents employed were ferric sulfate (Fe2(SO4)3·nH2O, Baker, 75%) and ferric chloride (FeCl3·6H2O, LOBAChemie, Mumbai, India, 97%).

The samples analyzed consisted of a copper and iron concentrate obtained from flotation processes in the southern region of Ecuador. A total mass of 50 kg of concentrate was used. Initially, a representative sample of the copper sulfide mineral was collected. This initial sample was quartered and homogenized to produce a final representative sample weighing approximately 2 kg, which was used for the subsequent assays and analyses described below.

2.2. Analysis and Characterization of the Concentrate

Mineralogical characterization was performed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) on a D8 ADVANCE diffractometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). The chemical composition was then determined using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) with the S8 Tiger equipment (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany).

The contents of gold and silver were determined using fire assay and atomic absorption techniques with the Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 300 (Perkin Elmer, Shelton, CT, USA). Due to the high copper and iron content in the concentrate, a pretreatment step was required. Specifically, 20 g of copper concentrate were weighed and roasted in a muffle furnace at 500 °C for 3 h, followed by an additional hour at 600 °C. After pretreatment, the sample was leached in the pulp with a 10% solids sulfuric acid solution (concentration 60 g/L) with magnetic stirring for 2 h. The leached sample was then washed with distilled water (35 °C), filtered, dried, and subjected to fire assay for gold and silver analysis.

The physical characterization of the concentrate included the evaluation of three parameters: particle size, moisture content, and volatile material content. A particle size analysis was performed using sieve analysis to determine the distribution of particle sizes within the sample. For moisture content, a 30 g sample of the concentrate was dried at 90 °C for 48 h, and the moisture was measured by mass difference. The volatile material content was determined by calcining the sample at 600 °C for 6 h.

2.3. Pretreatment of the Concentrate

To eliminate residual chemicals from the flotation process, including surfactants, frothers, and other reagents, the concentrate was washed with water at 35 °C. After washing, the sample was dried at 90 °C for 48 h to remove any remaining moisture before being used in the leaching experiments.

2.4. Leaching Experiments with Different Oxidants—Preliminar Test

In the initial stage, leaching experiments were conducted under the ambient pressure (0.72 atm) and temperature conditions typical of Quito, Ecuador (20 °C). The leaching medium was prepared using sulfuric acid at a concentration of 0.5 M. An oxidizing agents (Fe2(SO4)3 or FeCl3) was added to increase the initial electrochemical potential of the leaching solution to Eh > 550 mV, with a concentration of 0.1 M. Leaching tests were performed with Fe2(SO4)3 or FeCl3 as oxidizing agents to facilitate copper dissolution, as recommended in the literature [4,13,14].

The operating conditions included a pulp volume of 500 mL with 15% solids, mechanical agitation at 450 rpm, pH < 1.5, and Eh > 450 mV during the process, with continuous monitoring using a HANNA HI98121 m, equipped with an Ag/AgCl reference electrode. The experiments lasted for a total of 80 h. Solution samples were taken at 24, 48, 72, and 80 h to evaluate the copper dissolution kinetics.

Each test generated the following fractions: pregnant solution, wash solution, and tailings. To determine the copper content in the solutions, atomic absorption analysis was performed using a Perkin Elmer AA 300 (Perkin Elmer, Shelton, CT, USA). For the tailings (sludges), acid digestion (using nitric, hydrochloric, and hydrofluoric acids) was conducted prior to copper content analysis via atomic absorption with the Perkin Elmer AA 300. If the copper concentration in the tailings was above 1%, copper analysis was repeated using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) with the Bruker S8 Tiger (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). This approach allowed for the determination of copper concentration in each fraction and the monitoring of copper dissolution in solution during the leaching process.

2.5. Influence of Temperature and Solid Content on Copper Recovery During Leaching with Ferric Sulfate

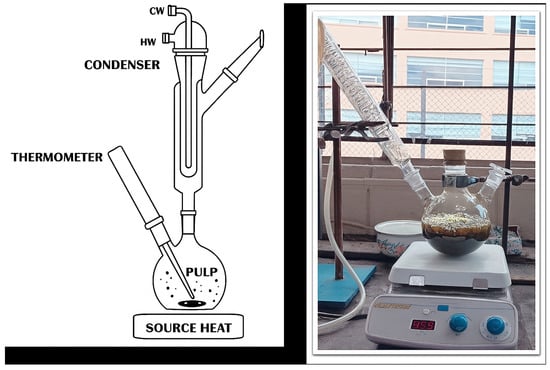

In the second stage, experiments were conducted to evaluate the impact of temperature, solid content (1%), a solid content of 1% was selected based on previous studies reporting improved leaching kinetics at low pulp densities [1,21]. Preliminary tests at 15% solids resulted in lower copper recovery, confirming that higher pulp density limits mass transfer and reduces leaching efficiency; and electrochemical potential (>450 mV) on copper recovery using sulfuric acid leaching with ferric sulfate as the oxidizing agent. Ferric sulfate (Fe2(SO4)3) was used as the oxidizing agent at a concentration of [0.1 M] in the pulp. The leaching temperature was increased to 92 °C, with a heating system employed to achieve this temperature, and a cooling system was adapted to the reactor to prevent solution loss due to evaporation (Figure 1). The solid content was set at 1%, and the leaching was conducted with magnetic stirring at 450 rpm, using a pulp volume of 500 mL. Aliquots were taken at 24, 48, 72, and 80 h to determine copper dissolution. The resulting fractions were collected and analyzed for copper content. Copper content in the solution was determined using atomic absorption spectroscopy with a Perkin Elmer AA 300 (Perkin Elmer, Shelton, CT, USA). For the obtained tailings, an acid digestion (nitric, hydrochloric, and hydrofluoric acids) was performed before copper content analysis using atomic absorption with the Perkin Elmer AA 300 (Perkin Elmer, Shelton, CT, USA). If the copper concentration was above 1%, copper analysis was repeated using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) with a Bruker S8 Tiger (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). After obtaining the copper content values for each fraction, a metallurgical balance was performed to determine the recovery.

Figure 1.

Heating and Cooling Systems to Prevent Solution Loss from Evaporation.

2.5.1. Copper Cementation

Once the pregnant leach solution (PLS) was obtained from the leaching experiment, copper recovery was carried out through a cementation process using solid iron. During this operation, the PLS was continuously agitated at 500 RPM to ensure thorough mixing and effective contact between the solution and the solid iron. Solid iron filings were gradually introduced into the agitated solution. As the cementation reaction occurred, copper in the leach solution reacted with the iron filings, leading to the precipitation of metallic copper (Figure 2). The precipitated copper was then separated from the solution, collected, and further processed as needed.

Figure 2.

Copper obtained by cementation.

2.5.2. Regeneration of the Oxidizing Potential of the Iron Residual Solution

Before the catalytic oxidation stage, the residual solution obtained after copper cementation was conditioned by dilution with 0.1 M H2SO4 in a 1:1 ratio. This adjustment was performed to match the iron concentration of the fresh leach solution and ensure comparable conditions. The pH of the solution was measured immediately after the cementation stage and again after dilution with 0.1 M H2SO4; in both cases, the pH remained below 1.5. Therefore, no additional acid was required to restore the pH conditions of the fresh leaching solution.

Catalytic oxidation was conducted under the following conditions: pH < 1.5; 3 g of activated carbon per 100 mL of residual solution; mechanical agitation at 500 rpm; and ambient temperature. The activated carbon used was a steam-activated microporous coconut shell carbon, with a specific surface area of 1200 m2/g, more than 95 % of which is in micropores, and an ash content of 2 %. Boehm titration indicated that the main surface functional groups were carboxyl, lactone, and phenol groups with a total acidic group content of 0.16 mmol/g [22].

The progression of Fe2+ oxidation was monitored by titration with 0.1 N potassium permanganate (KMnO4) at 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 24, 48, 72, 80, and 90 h. For each measurement, a 1 mL aliquot of the solution was titrated until a pale pink endpoint was reached. Once the maximum oxidation was achieved, the regenerated solution was recirculated in a second leaching cycle to assess copper recovery.

The residual solution, both before and after catalytic oxidation, was analyzed for iron and copper contents using Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (Perkin Elmer AA 300, Shelton, CT, USA). Additionally, pH and oxidation potential (Eh) were measured with a HANNA HI98121 m equipped with an Ag/AgCl reference electrode. The reported potentials were not corrected to the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE). Measurements were performed at ambient temperature (~20 °C) in the conditioned residual solution.

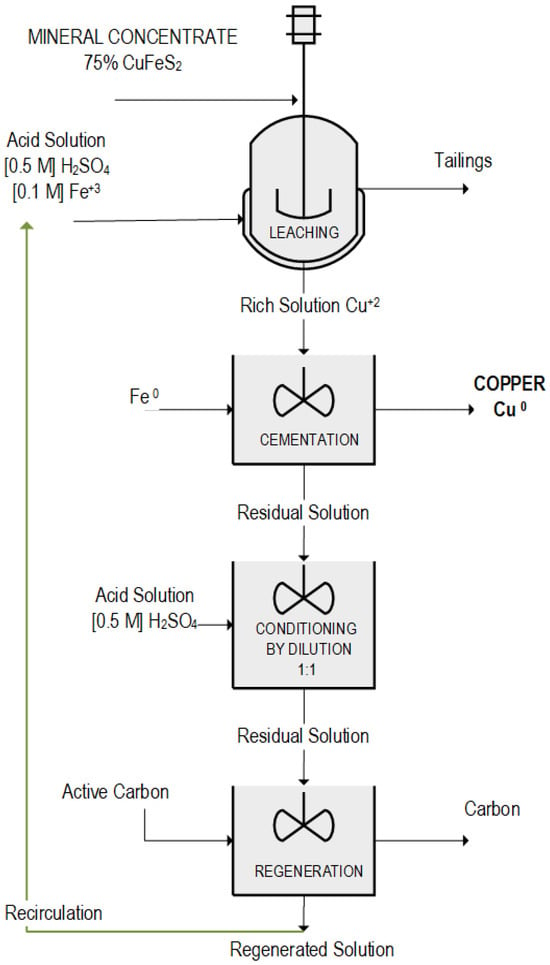

Figure 3 shows a schematic of the overall process carried out, illustrating the stages of ferric leaching with sulfuric acid, copper cementation, and regeneration of the oxidizing potential of the residual solution.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the Process.

All experiments under optimized conditions were performed in triplicate, and the reported values correspond to the mean of the most consistent replicates.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the Chalcopyrite-Rich Concentrate

The analysis conducted in this study determined that the concentrate sample contains 75% chalcopyrite and 10% pyrite as the major minerals, according to X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The elemental chemical analysis using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) revealed concentrations of Fe, Cu, and S at 16%, 15%, and 14%, respectively. The gold and silver contents, determined by fire assay, were 4 and 74 g/ton, respectively. These results, along with the physical characteristics of the concentrate, are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characterization and Properties of the Chalcopyrite-Rich Concentrate.

The chalcopyrite-rich flotation concentrate displayed a moisture content of 6.5%, and the volatile material removed by calcination at 600 °C for 6 h was 17.3%.

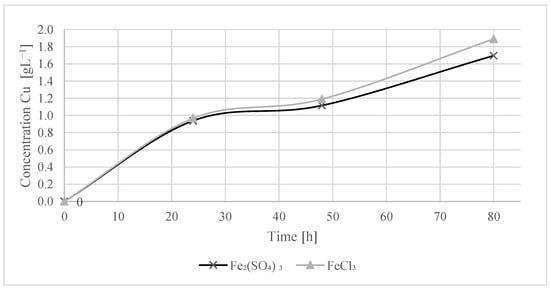

3.2. Influence of Ferric Sulfate and Chloride as Oxidizing Agents in Sulfuric Acid Leaching

The leaching process of the chalcopyrite-rich concentrate under normal environmental conditions (17 °C) showed a slow copper dissolution rate when treating a pulp with 15% solids. Figure 4 illustrates the copper dissolution over time using Fe2(SO4)3 and FeCl3 as oxidizing agents. The copper dissolution was similar with both reagents, with less than 2 g/L dissolved over 80 h (3.3 days). This indicates that less than 1 g of copper was dissolved from the 500 mL pulp, whereas the concentrate entering the process contained 11.55 g of copper. Therefore, the copper recoveries using Fe2(SO4)3 and FeCl3 were determined to be 7.5% and 8.2%, respectively. Table 2 provides a detailed summary of the recovery data obtained for each fraction resulting from the process.

Figure 4.

Dissolution of copper in sulfuric acid; T = 17 °C; 15% solids; [H2SO4] = 0.5 M; [Fe2(SO4)3] = 0.1 M or [FeCl3] = 0.1 M.

Table 2.

Copper Recovery via Ferric Leaching at 17 °C, 80 h.

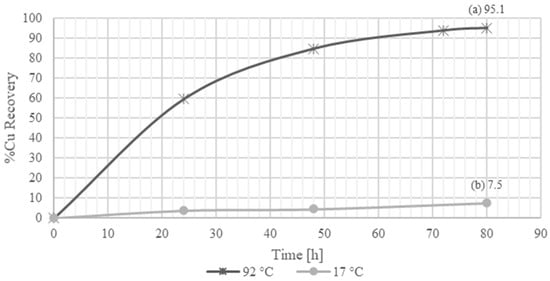

3.3. Influence of Solid Content in the Pulp and Temperature Conditions in Sulfuric Acid Leaching with Ferric Sulfate as an Oxidizing Agent

The impact of temperature and solids content in the pulp on leaching efficiency was investigated, given that low recovery (<8%) was observed with the initial conditions, which consisted of 15% solids and ambient temperature (17 °C), as described in the previous Section 3.2. In response to these results, new conditions were explored following literature recommendations [23], to use a lower solid percentage and increase the temperature in the leaching tests. The results obtained from leaching with sulfuric acid and ferric sulfate as the oxidizing agents at 92 °C and with a solid content of 1% in the pulp over a total time of 80 h (3.3 days) are detailed in Table 3. Figure 5 shows the recoveries as a function of time obtained in the process. The percentage of copper recovery in the pregnant solution was 95.1%. Compared to leaching at 17 °C and 15% solid content in the pulp, the recovery increased from 7.5% to 95.1%, indicating that approximately 13 times more copper was recovered by using higher temperature and lower solid content in the pulp. A direct relationship between temperature and copper dissolution in chalcopyrite-rich minerals has been established. Chalcopyrite dissolution involves high activation energy values according to various studies [10,24], highlighting the importance of high temperatures to break the bonds in the crystal structure of chalcopyrite. Furthermore, this activation energy is often lower when an oxidizing agent is added to the system.

Table 3.

Copper Recovery via Ferric Leaching at 92 °C, 80 h.

Figure 5.

Copper Recovery in Ferric Sulfuric Acid Medium [H2SO4] = 0.5 M; [Fe2(SO4)3] = 0.1 M: (a) T = 92 °C, 1% solids; (b) T = 17 °C, 15% solids.

3.3.1. Copper Cementation

After the cementation process was performed using the copper-rich solution by adding iron filings, a final concentration of Cu in solution of <0.1 g/L was obtained, with a 98.4% recovery of Cu through cementation. The conditions of the residual solution are shown in Table 4, which is presented further on.

Table 4.

pH, Eh (mV), copper and iron concentration (g L−1) of the residual solution before and after regeneration with activated carbon.

Table 4 presents a comparison between the parameters of a fresh leaching solution and a residual solution resulting from the leaching and cementation processes. The pH of the fresh solution ranges from 1.3 to 1.5, while the residual solution has a lower pH, between 0.9 and 1, indicating a slightly more acidic environment in the latter. Regarding the oxidation-reduction potential (Eh), the fresh solution shows a value greater than 550 mV, suggesting a higher oxidizing capacity, in contrast to the Eh of 291 mV in the residual solution. In terms of copper concentrations, the fresh solution does not present a value, while the residual solution shows a concentration of less than 0.1 g/L, indicating that most of the copper has been extracted.

3.3.2. Regeneration of the Electrochemical Potential of the Residual Iron Solution

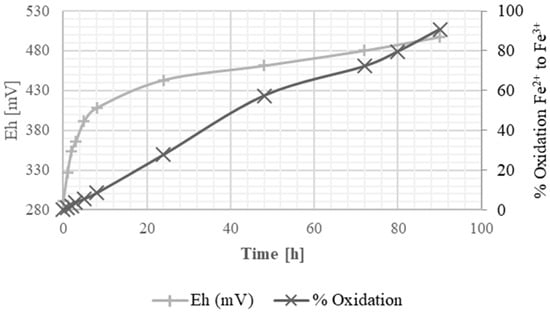

The regeneration of the electrochemical potential (Eh) of the residual iron solution was achieved through catalytic oxidation using activated carbon in a stirred reactor. This process facilitated the oxidation of Fe2+ ions to Fe3+, thereby enhancing the solution’s oxidizing potential. Figure 6 illustrates the percentage of Fe2+ oxidized over time, highlighting the effectiveness of activated carbon as a catalyst in this oxidation process.

Figure 6.

Electrochemical potential and Oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ vs. time for the residual solution during the oxidative regeneration process (pH < l.5, carbon mass/volume of solution: 3 g/100 mL, 500 RPM).

As shown in Figure 6, the catalytic oxidation of Fe2+ exhibited a gradual progression during the initial hours of treatment, achieving an oxidation percentage of only 5.6% after 5 h. Over time, the oxidation percentage significantly increased, reaching 57.4% after 48 h of treatment. The highest observed oxidation percentage was 90.7%, achieved after 90 h of treatment.

Figure 6 also illustrates the variation in the electrochemical potential (Eh) during the regeneration process. Within the first eight hours, the electrochemical potential increased by 40.2%, rising from 291 mV to 408 mV. This behavior contrasts with the findings of Ahumada [20], who reported a faster increase in electrochemical potential during oxidation with activated carbon, attributed to the immediate formation of hydrogen peroxide on the carbon surface.

Table 5 compares the residual solution before and after regeneration process with activated carbon. As presented in Table 5, three of the four parameters measured in the leach solution remained constant after the regeneration process. These parameters were pH (0.9–1) and the concentration of Cu (0.1 g L−1) and Fe (~11 g L−1). The residual content of copper in the regenerated solution would influence the leaching characteristics of the regenerated solution. The invariability in the content of Fe implies that activated carbon did not affect the concentration of this metal during the regeneration process. Finally, the electrochemical potential increased from 291 m V to 497 m V, making possible the recirculation of this regenerated solution in a new leaching cycle although the original value in a fresh solution was higher with a value of 550 m V. In the next section the results of using this regenerated solution in a new leaching cycle are discussed.

Table 5.

Comparative Data of Fresh Leaching Solution vs. Residual Solution.

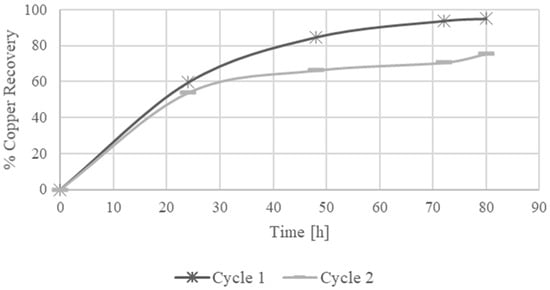

3.3.3. Recirculation of the Treated Solution in a New Leaching Cycle (Cycle 2)

The regenerated leach solution (pH = 0.9–1, Eh > 495 mV) obtained previously was used in a new ferric leaching process (1% solids, 92 °C, 0.5 mol L−1 of H2SO4, 0.1 mol L−1 of Fe2(SO4)3) and 450 RPM). The recovery of copper using this regenerated solution (cycle 2) is presented in Figure 7. Additionally, Figure 7 includes the copper recovery obtained by using a fresh leach solution (cycle 1).

Figure 7.

Copper recovery from chalcopyrite concentrate vs. time using a fresh leach solution (cycle 1) and a regenerated leach solution (cycle 2); [1% solids, 92 °C, 0.5 mol L−1 of H2SO4, 0.1 mol L−1 of Fe2(SO4)3) and 450 RPM].

As presented in Figure 7, the copper recovery obtained in the two cycles (cycle 1: fresh and cycle 2: regenerated) before 24 h were similar, reaching recovery percentages of 59.6% and 53.9%, respectively. After 24 h, the increase in copper recovery for the regenerated solution (cycle 2) was lower compared to the recovery obtained with a fresh leach solution (cycle 1). In fact, after 80 h of ferric leaching the recovery percentage of copper using a regenerated solution as leach agent (cycle 2) was only 75.6%, while the leaching with fresh solution reached a copper recovery of 95.1%.

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Ferric Sulfate and Chloride as Oxidizing Agents in Sulfuric Acid Leaching

The slow copper dissolution observed in the leaching of chalcopyrite-rich concentrate at 17 °C with a 15% solid content highlights several critical aspects of the leaching process. The results indicate that using Fe2(SO4)3 and FeCl3 as oxidizing agents under these conditions yielded relatively low copper recoveries, with values of 7.5% and 8.2%, respectively.

Copper dissolution from chalcopyrite is influenced by several factors, including the mineral’s complex structure, its refractory nature, and the passivation phenomenon that occurs during leaching. These factors collectively contribute to a gradual and slow dissolution process. Khoshkhoo [16] and Dixon [11] found that the presence of pyrite in chalcopyrite-rich concentrates enhances copper dissolution. Pyrite appears to have a galvanic effect that facilitates copper recovery. These studies suggest that working within an electrochemical potential range of 420–450 mV, especially in the presence of pyrite, improves copper recovery. Furthermore, Khoshkhoo [16] highlighted a significant difference in the leaching performance between fresh and aged sulfide mineral concentrates, noting that aged minerals, which have partially altered surface compositions, show reduced recovery when subjected to electrochemical potentials below 620 mV.

Studies have demonstrated the challenges of leaching chalcopyrite. For instance, Yang [14] reported that copper recoveries often remain below 10% even under optimal conditions over a 72 h leaching period. Further investigation into the effect of the initial redox potential revealed that at 35 °C, the impact of redox potential was negligible, with copper extractions remaining very low (below 2.5%) across all cases [10]. This low reactivity of the chalcopyrite surface is consistent with minimal consumption of the oxidizing agent (Fe3+) and highlights the challenges in improving recovery rates under such conditions.

Typically, the leaching process for chalcopyrite-rich ores extends over approximately 15 days, with recoveries often less than 40%, contingent on the ore’s specific characteristics [2,23]. The use of ferric oxidizing agents, such as ferric sulfate, plays a crucial role in enhancing leaching efficiency. Ferric sulfate acts as a potent oxidizing agent, facilitating the dissolution of chalcopyrite and improving copper recovery.

The similarity in performance between Fe2(SO4)3 and FeCl3 suggests that neither reagent significantly outperforms the other in terms of enhancing copper recovery. However, it is important to note that ferric ions play a crucial role as oxidizing agents in the leaching process. While the overall improvement in copper recovery was modest under the tested conditions, ferric ions are essential for facilitating the oxidation of chalcopyrite and enhancing dissolution rates.

Despite the limited difference in performance between Fe2(SO4)3 and FeCl3, ferric sulfate (Fe2(SO4)3) was selected in subsequent sections. This choice aims to minimize the introduction of additional foreign ions into the system, which could complicate the leaching process and affect overall efficiency. By focusing on ferric sulfate, we seek to simplify the process and optimize conditions for improved copper recovery while maintaining a simpler chemical system. To manage the challenges identified, it is crucial to explore alternative leaching conditions. Increasing the temperature could enhance the reactivity of both chalcopyrite and the oxidizing agents, potentially improving copper dissolution rates.

The minor components (9%) of the concentrate mainly include clinoclore ((Mg,Fe)5Al(Si,Al)4O10(OH)8), sodalite (Na8(AlSiO4)6(ClO4)2), plagioclase group ((Na,Ca)Al(Si,Al)Si2O8), muscovite (KAl2(AlSi3O10)(OH)2), and sphalerite (ZnS). These minerals may slightly affect the pH and consume a small fraction of the leaching agent. Nevertheless, their overall influence on copper recovery is negligible due to their minor proportion.

4.2. Influence of Solid Content in the Pulp and Temperature Conditions in Sulfuric Acid Leaching with Ferric Sulfate as an Oxidizing Agent

Increasing the temperature and reducing the solids content in the pulp significantly enhance leaching efficiency for copper recovery from chalcopyrite-rich minerals. Adjusting the conditions to 92 °C and reducing the solids content to 1% resulted in a remarkable increase in recovery, reaching 95.1%. This result aligns with findings from Khoshkhoo [16], who achieved approximately 80% copper recovery in just 24 h using ferric acid leaching on a concentrate composed of 62% CuFeS2 and 32% FeS2, also with 1% solids at 80 °C and an electrochemical potential of 420 mV. Additionally, a recovery of 75% was obtained with a concentrate containing 92% CuFeS2 using only 0.3% solids, at the same temperature and an oxidation potential of 450 mV. These comparisons underscore the critical role of both temperature and solids content in optimizing copper recovery from chalcopyrite-rich materials.

Koleini [23] highlights that the solids content influences copper recovery during leaching. At higher solids content (14.5%), recovery decreases, suggesting that reducing solids could optimize the leaching process. In their experiments, with a redox potential of 410 mV and at 85 °C, a solid content of 2.5% achieved approximately 75% recovery after 24 h. In comparison, our research, conducted at 92 °C and with only 1% solids, reached 60% recovery in the same time.

Regeneration of the Electrochemical Potential of the Residual Iron Solution and Recirculation of the Treated Solution in a New Leaching Cycle (Cycle 2)

After the leaching process, a cementation step was conducted to recover the dissolved copper. This process successfully extracted copper as a solid phase, leaving behind a residual solution with conditions that differed significantly from the initial leaching solution. The fresh leaching solution demonstrates a high Eh value, above 550 mV, which reflects its strong oxidizing capacity and its effectiveness in dissolving metals. In contrast, the residual solution has a lower Eh of 291 mV and does not have the oxidative properties needed for efficient leaching. This difference highlights the need to regenerate the oxidizing potential of the residual solution to maintain leaching efficiency in future cycles.

To restore the oxidative properties of the residual solution, catalytic oxidation with activated carbon was employed. This treatment effectively increased the Eh to 497 mV, enabling the regenerated solution to recover some of its oxidizing capacity. As a result, the treated solution could be recirculated for use in a new leaching cycle, demonstrating the potential for improved resource efficiency and reduced waste generation. The oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ in the presence of activated carbon occurs predominantly through a heterogeneous catalytic mechanism. The activated carbon used in this study was steam-activated microporous coconut shell carbon, with a specific surface area of 1200 m2/g, a micropore fraction >95 %, ash content of 2 %, and acidic surface functional groups (carboxyl, lactone, phenol) totaling 0.16 mmol/g, determined via Boehm titration. These structural and chemical properties provide active sites that facilitate electron transfer between Fe2+ and dissolved oxygen. The surface functional groups participate transiently in the redox cycle and are subsequently regenerated, enhancing the oxidation rate. Therefore, the process can be considered predominantly catalytic, with the microporous structure and surface functionalities of the carbon actively contributing to the Fe2+ oxidation efficiency [20,25,26].

Although the electrochemical potential (Eh) increased significantly during the first eight hours, the trend of Fe3+ concentration does not exactly follow the Eh profile. This discrepancy can be explained by the nature of the redox system. Eh reflects the overall redox potential, which is influenced not only by the Fe2+/Fe3+ pair but also by dissolved oxygen, H2O2, and other oxidizing species. The oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ may proceed at a slower rate than the change in Eh, reflecting kinetic differences. Additionally, some H2O2 or Fe2+ may participate in parallel reactions, further contributing to the observed deviation between Eh and Fe3+ trends.

During the initial leaching cycle, not only copper but also other ions from the concentrate dissolve into the solution. These additional ions, combined with residual copper, influence the ion transfer dynamics and slow the oxidation kinetics of chalcopyrite during the second cycle. This phenomenon creates competition for reaction sites, hindering the efficiency of the regenerated solution. Future experiments could include specific quantification of these ions before and after the reaction to better understand their potential to occupy reaction sites or generate secondary products. Furthermore, the higher concentration of ions in solution may hinder mass transfer, thereby reducing the overall dissolution efficiency. This aspect is acknowledged and discussed as an opportunity for further investigation.

The regenerated solution had an initial Eh of 497 mV, which, while improved compared to the residual solution, remained lower than the Eh of fresh leaching solution (550 mV). This reduced oxidizing potential is directly linked to the decreased copper recovery observed in the second leaching cycle.

In fact, increasing the electrochemical potential of the solution during the regeneration process by catalytic oxidation is needed. Some alternatives for increasing the electrochemical potential would include bubbling air to keep a constant level of dissolved oxygen during the catalytic process or using stronger oxidants like ozone or permanganate. However, this study has demonstrated that catalytic oxidation with activated carbon was capable of regenerate the residual solution rendering possible the recirculation of the leach solution.

5. Conclusions

The recovery of copper from chalcopyrite-rich concentrates is significantly influenced by the mineralogical characteristics of the concentrate. The results obtained in this study are specific to the chalcopyrite-rich concentrate analyzed, reflecting its unique mineral composition and properties. The concentrate composition was 75% chalcopyrite and 10% pyrite. Additionally, there are concentrations of 15% copper (Cu), 16% iron (Fe), and 14% sulfur (S). Furthermore, the precious metal content is notable, with 4 g/ton of gold (Au) and 74 g/ton of silver (Ag).

Ferric sulfate (Fe2(SO4)3) and ferric chloride (FeCl3) as oxidizing agents, under ambient conditions (17 °C) and with a 15% solids pulp, show that the copper dissolution is relatively low. Both oxidizing agents exhibited similar effectiveness, achieving copper recoveries of 7.5% and 8.2%, respectively, after a period of 80 h. In subsequent trials, ferric sulfate was selected as the oxidizing agent to avoid adding more species to the system.

The recovery rates for copper leaching with sulfuric acid and ferric sulfate as the oxidizing agent varied significantly with the leaching conditions. At 17 °C with 15% solids, the copper recovery was 7.5%. In contrast, at 92 °C with 1% solids, the recovery rate improved substantially to 95.1% after 80 h. This demonstrates a strong positive correlation between temperature and copper dissolution, indicating that higher temperatures enhance copper recovery.

The cementation process effectively recovered copper, reducing the final copper concentration in the solution to less than 0.1 g/L and achieving a solid copper recovery rate of 98.4%.

To enhance the oxidizing potential of the residual solution, catalytic oxidation with activated carbon was performed, effectively converting ferrous ions (Fe2+) into ferric ions (Fe3+). The initial potential of the residual solution was 291 mV, and through the catalytic oxidation process, it was regenerated to 497 mV, restoring 90.7% of its oxidizing potential. The catalytic oxidation method demonstrates potential for industrial regeneration of ferric solutions by restoring the oxidizing potential of the leaching solution. Compared with traditional pyrometallurgical processes, it offers advantages including lower energy consumption, reduced environmental impact, and the potential for reuse of leaching solutions, thereby enhancing sustainability.

The fresh leaching solution initially exhibited a potential of >550 mV due to the action of ferric ions, achieving a copper recovery of 95.1% during the first leaching cycle. The regenerated solution enabled a second leaching cycle, yielding a copper recovery of 75.6%.

As this work represents an initial laboratory-scale approach, future developments based on these findings could explore strategies to optimize the handling of the excess leaching solution generated during the conditioning step by dilution. Such considerations would contribute to improving process efficiency and scalability under industrial conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.d.l.T. and V.C.-A.; methodology, E.d.l.T. and V.C.-A.; validation, E.d.l.T. and V.C.-A.; formal analysis, V.C.-A.; investigation, V.C.-A.; resources, E.d.l.T. and V.C.-A.; data curation, V.C.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, V.C.-A. and C.F.A.-T.; writing—review and editing, V.C.-A. and C.F.A.-T.; visualization, V.C.-A.; supervision, E.d.l.T.; project administration, E.d.l.T.; funding acquisition, E.d.l.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research presented in this study was made possible by funding from the Department of Extractive Metallurgy (DEMEX) of the Escuela Politécnica Nacional, with thanks to research project PVIF-20-01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ibáñez, T.; Velásquez, L. The dissolution of chalcopyrite in chloride media | Lixiviación de la calcopirita en medios clorurados. Rev. Metal. 2013, 49, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Li, H.; Wei, Q.; Qin, W.; Yang, C. Effects of redox potential on chalcopyrite leaching: An overview. Miner. Eng. 2021, 172, 107135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Chilena del Cobre (COCHILCO). Sulfuros primarios: Desafíos y Oportunidades; DEPP 17/2017; Registro Propiedad Intelectual Nº 2833439; 2017. Available online: https://www.studocu.com/cl/document/instituto-profesional-iacc/extraccion-minas-subterraneas/sulfuros-primarios-desafios-y-oportunidades/61949135 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Córdoba, E.M.; Muñoz, J.A.; Blázquez, M.L.; González, F.; Ballester, A. Leaching of chalcopyrite with ferric ion. Part I: General aspects. Hydrometallurgy 2008, 93, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Y.; Li, H.; Zhou, L. Study of galvanic interactions between pyrite and chalcopyrite in a flowing system: Implications for the environment. Environ. Geol. 2007, 52, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira, C.; De Lima, G.F.; De Abreu, H.A.; Duarte, H.A. Reconstruction of the chalcopyrite surfaces-A DFT study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 6357–6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Dreisinger, D. Copper leaching from chalcopyrite concentrate in Cu(II)/Fe(III) chloride system. Miner. Eng. 2013, 45, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qian, L.; Sun, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Kim, H.; Qiu, G. The dissolution and passivation mechanism of chalcopyrite in bioleaching: An overview. Miner. Eng. 2019, 136, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.B.; Miller, J.D.; Wadsworth, M.E. Reaction mechanism for the acid ferric sulfate leaching of chalcopyrite. Metall. Trans. B 1979, 10, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba, E.M.; Muñoz, J.A.; Blázquez, M.L.; González, F.; Ballester, A. Leaching of chalcopyrite with ferric ion. Part II: Effect of redox potential. Hydrometallurgy 2008, 93, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, D.G.; Mayne, D.D.; Baxter, K.G. GALVANOX™–A Novel Galvanically-Assisted Atmospheric Leaching Technology for Copper Concentrates. Can. Metall. Q. 2008, 47, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kawashima, N.; Kaplun, K.; Absolon, V.J.; Gerson, A.R. Chalcopyrite leaching: The rate controlling factors. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2010, 74, 2881–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gan, X.; Zhao, H.; Hu, M.; Li, K.; Qin, W.; Qiu, G. Dissolution and passivation mechanisms of chalcopyrite during bioleaching: DFT calculation, XPS and electrochemistry analysis. Miner. Eng. 2016, 98, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Qin, W.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Mixed potential plays a key role in leaching of chalcopyrite: Experimental and theoretical analysis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 1733–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, Å.; Shchukarev, A.; Paul, J. XPS characterisation of chalcopyritechemically and bio-leached at high and low redox potential. Miner. Eng. 2005, 18, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshkhoo, M.; Dopson, M.; Engström, F.; Sandström, Å. New insights into the influence of redox potential on chalcopyrite leaching behaviour. Miner. Eng. 2017, 100, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, R.; Zambrano, P.; Ruiz, M.C. Cinética de la Lixiviación de Calcopirita Sulfurizada. Congreso CONAMET/SAM-Simposio Materia. 2002. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/doc/130349969/CINETICA-DE-LA-LIXIVIACION-DE-CALCOPIRITA-SULFURIZADA (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Liu, H.C.; Nie, Z.Y.; Xia, J.L.; Zhu, H.R.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, C.H.; Zheng, L.; Zhao, Y.D. Investigation of copper, iron and sulfur speciation during bioleaching of chalcopyrite by moderate thermophile Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans. Int. J. Miner. Process 2015, 137, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.F.R.; Orfao, J.J.M.; Figueiredo, J.L. Oxidative dehydrogenation of ethylbenzene on activated carbon catalysts. 2. Kinetic modelling. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2000, 196, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahumada, E.; Lizama, H.; Orellana, F.; Suárez, C.; Huidobro, A.; Sepúlveda, A.; Rodríguez, F. Catalytic oxidation of Fe(II) by activated carbon in the presence of oxygen: Effect of the surface oxidation degree on the catalytic activity. Carbon 2002, 40, 2827–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winarko, R.; Dreisinger, D.B.; Miura, A.; Tokoro, C.; Liu, W. Kinetic modelling of chalcopyrite leaching assisted by iodine in ferric sulfate media. Hydrometallurgy 2020, 197, 105481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Torre Miranda, N. Functionalization of Activated Carbon for Recovery of Gold Thiosulfate. Ph.D. Thesis, Université catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Koleini, S.J.; Aghazadeh, V.; Sandström, Å. Acidic sulphate leaching of chalcopyrite concentrates in presence of pyrite. Miner. Eng. 2011, 24, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harahsheh, M.; Kingman, S.; Hankins, N.; Somerfield, C.; Bradshaw, S.; Louw, W. The influence of microwaves on the leaching kinetics of chalcopyrite. Miner. Eng. 2005, 18, 1259–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Mu, C.; Wang, D.; Huang, D.; Zhang, X. Activated carbon accelerates the oxygenation of ferrous ion and hydroxyl radical production. Environmental Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 11232–11240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, K.; Uchida, H.; Kato, M. Catalytic mechanism of activated carbon-assisted bioleaching of chalcopyrite. Hydrometallurgy 2020, 195, 105383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).