Abstract

Inefficient management of dissolved oxygen (DO) in intensive aquaculture systems limits fish welfare and productivity by creating oxygen-deficient zones and promoting hydrodynamic conditions that hinder their dispersion. Because water movement directly influences how oxygen is transported and mixed within the culture unit, inadequate flow management can allow localized hypoxia to persist even when total oxygen input appears sufficient. To address this issue, this study proposes an integrated methodology that combines in situ respirometry measurements with Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations to evaluate the spatial distribution of DO and diagnose the operational performance of aquaculture systems. The methodology quantifies oxygen consumption using intermittent-flow respirometry, applies a three-dimensional two-phase CFD model (water–oxygen) incorporating experimental oxygen consumption rates as boundary conditions, and validates the model under real operating conditions, focusing on active metabolism as the most demanding physiological state. The model generates a spatial distribution of DO patterns that are significantly modified by pond geometry, water flow characteristics, the metabolism of the fish and fish positioning. The differences between experimental and simulated values ranged from 7.8% to 10.7%, confirming the accuracy of the proposed method. The integration of in situ metabolic measurements with CFD modeling provides a realistic representation of DO dynamics, enabling system optimization and promoting more efficient and sustainable aquaculture.

1. Introduction

Dissolved oxygen (DO) is one of the most critical parameters for determining water quality in aquaculture systems. It plays a crucial role in fish respiration, the oxidation of nitrogenous compounds, and the microbial stability of aquatic ecosystems [1,2]. In intensive farming systems, limited DO concentrations represent one of the primary stressors for fish, leading to reduced growth, higher susceptibility to disease, and, in extreme cases, massive mortality [3,4]. Therefore, monitoring and regulation of oxygen have long been considered essential practices in aquaculture management [5].

Traditional DO management treats oxygen as a single-point water quality variable, focusing mainly on maintaining minimum concentrations and applying immediate corrective measures such as aeration or water exchange to prevent critical conditions that could compromise fish welfare [6]. These operational responses, although effective in preventing acute hypoxia, treat oxygen as a static, single-point variable. However, this approach is limited because oxygen is a dynamic metabolic resource whose availability depends on complex interactions among physical, chemical, and biological processes, as well as on the farmed biomass itself [7].

From this perspective, the concept of dissolved oxygen management should be understood as an integrated set of practices and tools aimed not only at maintaining adequate DO levels but also at anticipating, regulating, and optimizing its spatial and temporal distribution within aquaculture systems. This comprehensive management includes preventive (hydraulic design, recirculation, aeration), corrective (operational adjustments, stocking density, water renewal), and predictive (numerical modeling and experimental data integration) components. Hence, oxygen must be regarded as a dynamic variable essential for the efficiency and sustainability of aquaculture systems, rather than a static indicator of water quality.

The effective understanding and management of DO requires tools capable of representing its spatial–temporal behavior within production systems, as its distribution is neither homogeneous nor static. Factors such as pond geometry, flow velocity, biomass density, turbulence, and environmental conditions significantly influence internal oxygen gradients. Conventional monitoring methods based on portable probes or discrete point sampling [8,9,10,11], have proven insufficient for capturing the spatial–temporal variability of dissolved oxygen in production systems, as they do not allow the identification of internal gradients generated by hydrodynamics, biomass distribution, pond geometry, or metabolic variation among fish. These processes can lead to hypoxic zones, vertical DO stratification, or regions of reduced flow [6,12], thereby promoting the use of numerical modeling to predict and optimize DO dynamics under varying operational conditions.

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has emerged as a powerful tool for analyzing and optimizing aquaculture systems. Initially, CFD was applied to describe hydrodynamic patterns within ponds, allowing the identification of low-velocity zones, hydraulic short-circuiting, and recirculation regions that affect water exchange efficiency [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Later applications were expanded to include solid transport and sedimentation studies, improving waste removal, and optimizing the geometric design [20,21,22,23,24].

More recently, CFD has been used to model coupled hydrodynamic and water quality processes such as temperature, ammonium concentration, and DO [25,26], enabling a realistic 3D representation of gas dynamics within aquaculture systems. This has enlightened the influence of pond geometry, turbulence, aeration, and management practices for DO distribution [27,28,29,30]. Despite this progress, a critical limitation persists: most CFD studies focus primarily on describing the spatial distribution of DO within ponds and proposing improvements based on geometric modifications or aeration strategies, while neglecting the biological component namely, the fish that fundamentally drive oxygen consumption. In many cases, fish are either excluded from the simulations or represented using highly simplified assumptions that do not capture their physiological heterogeneity. Moreover, several investigations describe inflow or internal concentrations corresponding to oxygen saturation levels close to 100%, and in some cases involve the injection of pure oxygen or the use of high-efficiency aeration systems designed to maintain near-saturation conditions [14,31,32,33], a condition that is practically unattainable in commercial production units and thus introduces additional deviations from real operational scenarios.

Most importantly, the majority of CFD models still rely on theoretical, generalized, or laboratory-derived oxygen consumption rates that fail to represent actual metabolic activity under production conditions [29,34,35,36]. Because fish oxygen demand constitutes the dominant oxygen sink in aquaculture systems, inaccuracies in these metabolic inputs propagate directly into the model outputs. Integrating experimentally derived boundary conditions such as in situ respirometry measurements, can substantially enhance the predictive capacity of CFD simulations, yielding a more realistic and operationally useful tool for dissolved oxygen management and production optimization [14]. This approach is particularly relevant given that DO consumption depends strongly on the farmed species, biomass, metabolic state, and environmental conditions within the culture system.

Respirometry represents one of the most accurate tools to quantify oxygen consumption (O2) due to the capacity of evaluate physiological and population conditions for specific species [37,38,39]. Several methods have been used in fish, including static respirometry, continuous flow respirometry, and intermittent-flow respirometry [40,41]. The latter represents a practical intermediate alternative, combining closure periods during which the DO decrease is measured, with open flow or recirculation phases that restore the initial DO concentration, preventing hypoxia and waste accumulation without requiring a permanent continuous flow [38,42].

This approach allowed robust estimates of standard and active metabolism in laboratory studies and has been used to analyze the physiological responses of fish to temperature, hypoxia, salinity, or contaminants exposure [43,44,45]; remaining limited in aquaculture production contexts. Traditional intermittent flow equipment and protocols were designed for isolated individual organisms or small groups in airtight chambers, which restricts their scalability to dense populations. Furthermore, conventional systems do not realistically reproduce the hydrodynamic and environmental conditions of ponds or raceways, leading to discrepancies between laboratory data and field prediction [46,47].

Given the above-mentioned limitations, adapting intermittent flow respirometry to commercial aquaculture systems represents a significant methodological advance, as it allows for recording oxygen consumption under intensive farming conditions, provided the fish, water flow, and environmental underlying factors to massive production. Incorporating respirometry data into CFD models improves the predictive capacity of simulations, reducing uncertainty, and provides a robust tool for the design, evaluation, and improvement of oxygen management strategies in intensive aquaculture.

This study proposes a methodology that combines in situ intermittent-flow respirometry and CFD simulations to model DO distribution in a raceway aquaculture pond for rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). The approach allows for evaluating and diagnosing pond operation and identifying potential hydrodynamic retrofitting strategies for system improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

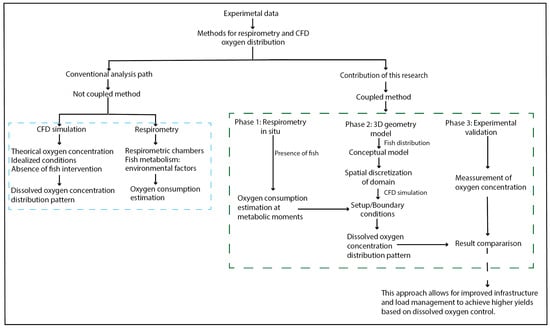

The research was structured into three integrated phases (Figure 1): (1) experimental measurement of DO consumption rates through in situ intermittent-flow respirometry under commercial production conditions using rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in standard (SMR), routine (RMR), and active/maximum metabolic states (AMR/MMR); (2) numerical modeling using three-dimensional two-phase CFD simulations (water–oxygen) to estimate the spatial distribution of DO in a raceway pond; and (3) validation of the numerical model under real operating conditions.

Figure 1.

General diagram of the research methodology.

The experimental DO consumption data were incorporated into a CFD model as initial and boundary conditions. The experimental design considered the three classic fish metabolic states: standard (SMR), routine (RMR), and active/maximum (AMR/MMR). The AMR/MMR state was prioritized in simulations, as it represents the most physiologically demanding condition, corresponding to sustained exercise and feeding activities in intensive aquaculture practices [37,48].

The numerical configuration replicated actual system conditions, including geometry, flow rate, water temperature, and site altitude, ensuring coherence between the modeled and experimental scenarios. The fish biomass was explicitly represented within the computational domain, serving as an oxygen sink boundary condition based on metabolic state.

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted at the TEPOZAN aquaculture production unit located in the municipality of Temoaya, State of Mexico, Mexico (19°29′09″ N 99°33′07″ W) at an altitude of 2792 mosl. A population of 486 adult rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) was maintained at the pond for respirometry stage, with an average individual weight of 1.16 ± 0.57 kg and an average total length of 39.0 ± 9.2 cm.

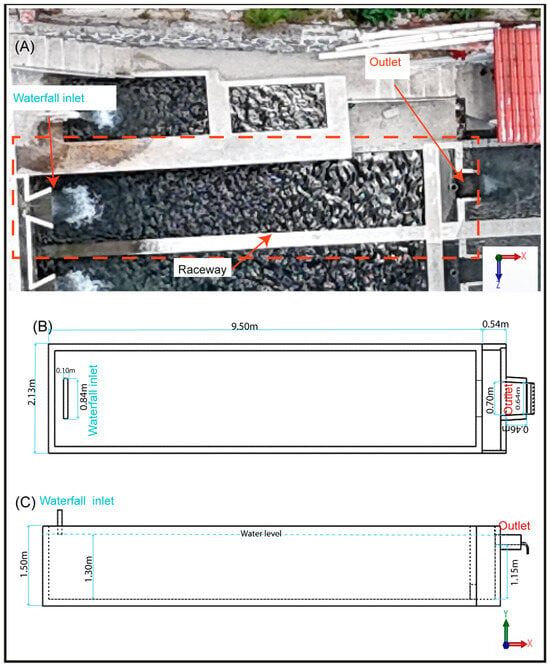

The aquaculture pond is a raceway type with 9.50 m in length, 2.13 m in width, and 1.50 m in depth, and a water volume of 24.7 m3.

The pond is supplied with clear water, free of microalgae and organic matter on the bottom of the raceway. Water was delivered through a cascade-type inlet located at the upstream end of the raceway, centered along the width of the pond and positioned 1.45 m above the water surface. The inlet opening measured 0.84 m × 0.10 m and provided a constant flow rate of 10 L/s at an average temperature of 12 °C. The outflow was located at the downstream end and consisted of a sharp-crested rectangular weir (0.70 m × 0.46 m), also centered along the pond width and positioned 1.30 m above the bottom (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Geometric model and components of the raceway. (A) Physical model, (B) 3D model in top view, (C) 3D model in lateral view.

2.2. Respirometry (Oxygen Consumption)

The oxygen consumption during the active metabolic state (AMR/MMR) of the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) was determined using the intermittent-flow respirometry technique applied in situ.

Unlike conventional methodologies that employ individual chambers or sealed respirometers, this study maintained the organisms under authentic commercial production conditions, meaning that the entire raceway pond functioned as a respirometry chamber. Under this assumption, the contributions of microbial respiration, organic matter oxidation, and atmospheric exchange were considered negligible relative to the total dissolved oxygen consumption and therefore were not isolated or controlled. At the beginning of each experimental trial, the inflow of water to the raceway was halted to prevent hydraulic exchange during the measurement period.

The operational conditions established for the raceway-as-respirometry-chamber accurately reflected those used by producers operating under intensive aquaculture schemes. These conditions included the use of a concrete raceway without supplemental oxygen supply, daily removal sediments; a stocking density (22.75 kg/m3) consistent with commercial practice, and a feeding regime based on balanced commercial diets provided according to established nutritional requirements for the species (2% of biomass daily). The system typically operated with a continuous flow of spring water, with water exchange rates aligned with commercial raceway standards (hydraulic retention time of 41 min). The fish used in the trials were reproductively mature organisms in optimal physiological condition, and both temperature and water quality parameters were maintained within the ranges characteristic of high-altitude aquaculture farms, specifically 12 °C and an oxygen saturation of approximately 78%.

Oxygen measurements within the pond were obtained using a previously calibrated multiparametric oximeter (YSI Pro20) with a precision of ±0.01 mg/L, equipped with a 31 µm thin membrane suitable for water velocities below 5 cm/s. Measurements were taken at two fixed locations within the raceway, both positioned in the mid-lower portion of the water column, equivalent to the recommended placement for respirometry chambers in conventional studies [25,30]: (1) at the inlet zone, immediately upstream of the flow-entry point, and (2) near the outlet, just upstream of the weir. Dissolved oxygen concentrations were continuously recorded as they progressively decreased until reaching a threshold of 5 mg/L to prevent biomass stress. This procedure was performed under different metabolic conditions: standard (SMR), routine (RMR), and active (AMR/MMR).

The oxygen consumption rate (, ) was estimated based on the decline in dissolved oxygen concentration (, in ) over the experimental period (, in h), considering the pond volume (, in L) and total biomass (, in kg of fish), as [49]:

Once estimated, the experimental values were converted into an equivalent oxygen mass flow rate (, kg/s) to ensure physical compatibility with the CFD boundary conditions. This conversion accounted for the total biomass present in the pond and the duration of the respirometry trial, allowing the experimentally derived oxygen demand to be expressed as a net sink term suitable for numerical implementation. The resulting values were then assigned to the fish-representative internal surfaces in the CFD domain, thereby achieving a direct physical and numerical coupling between the in situ metabolic measurements and the three-dimensional hydrodynamic–oxygen transport simulation.

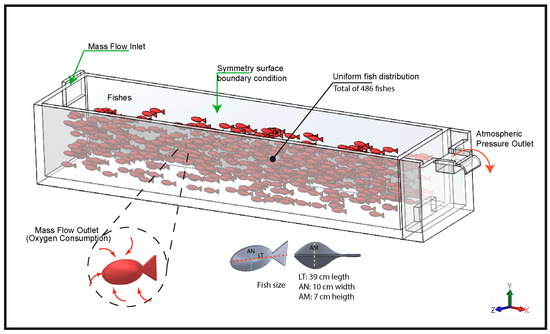

2.3. CFD Model Configuration

The implementation of the three-dimensional model was carried out using ANSYS Fluent 2022® (ANSYS Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA), explicitly incorporating fish biomass within the computational domain through spatial volumes configuration generated in SOLIDWORKS 2019. These volumes were scaled proportionally to the average size of the specimens (39 ± 9.2 cm total length, 7 ± 1.4 cm maximum height, and 10 ± 1.7 cm width). The volumes were uniformly distributed throughout the pond to adequately represent the spatial positioning of the organisms and their influence on hydrodynamics and DO distribution within the system.

The numerical modeling was structured under a conceptual framework designed to represent the hydrodynamic and oxygen transport processes in a raceway-type aquaculture system (Figure 3). For this purpose, the multiphase Mixture model was employed, defining water as the primary phase and dissolved oxygen as the secondary phase. In this formulation, oxygen was treated as a dilute dispersed phase transported solely by convection and turbulent diffusion. The governing transport equation for the secondary phase volume fraction can be expressed as seen on Equation (2). It depends on the mixture density ( kg/m3), the volumetric fraction of oxygen ( adimensional), the mixture velocity ( m/s) and the turbulent viscosity of the mixture ( kg/m·s).

Figure 3.

Conceptual model of the simulation.

This model was selected because it provides a stable and fully coupled representation of oxygen transport in a domain containing fish-shaped internal surfaces configured as metabolic sinks, allowing the simulation to capture the spatial redistribution of oxygen under the combined effects of turbulence, flow perturbations, and biomass-induced consumption. In addition, this simplified model makes it possible to perform high-fidelity transport-only simulations while accounting for the presence of biomass, being more efficient than mass-transfer-based models. For turbulence estimation, the k–ε model was selected, which has been widely employed in hydraulic and aquaculture simulations due to its efficiency in reproducing turbulent mixing mechanisms and energy dissipation [49].

The inlet boundary condition was configured as a Mass Flow Inlet, ensuring controlled mass flow input to the system. The surface area of each fish was defined as a Mass Flow Outlet for the oxygen phase, representing the net oxygen consumption attributable to the biomass. The free water surface was idealized as a symmetry boundary, assuming an undeformed interface and no atmospheric exchange, whereas the outlet weir was modeled as a Pressure Outlet corresponding to the standard atmospheric pressure at the study site.

In accordance with the conceptual framework of the study, several methodological simplifications were established to ensure numerical stability and to focus the analysis on the hydrodynamic behavior and dissolved oxygen redistribution within the raceway. The simulation was limited to representing oxygen as a dilute secondary phase transported by convection and turbulent diffusion, without explicitly resolving gas–liquid mass transfer processes. The free water surface was therefore idealized as a symmetry boundary, assuming the absence of interfacial deformation and atmospheric exchange under the selected modeling conditions. Fish were incorporated as stationary, rigid internal volumes acting solely as metabolic sinks for the oxygen phase, which implies that locomotion, schooling behavior, and respiratory flows generated by opercular movements were not considered. Additionally, the k–ε turbulence model was applied as an engineering approximation of bulk mixing, acknowledging its limited capacity to capture fine-scale vortical structures. These assumptions enabled isolating the effects of biomass spatial distribution and metabolic oxygen demand on dissolved oxygen patterns. Consequently, the present model focuses on resolving the spatial distribution of DO rather than fully characterizing the complete multiphase oxygen dynamics of the system.

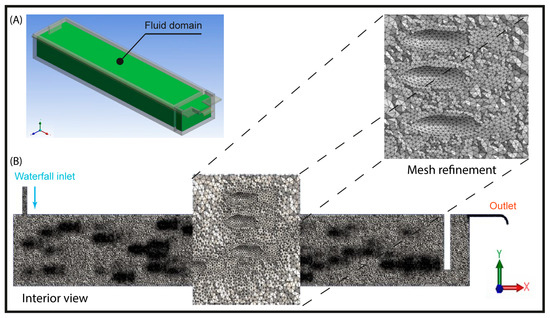

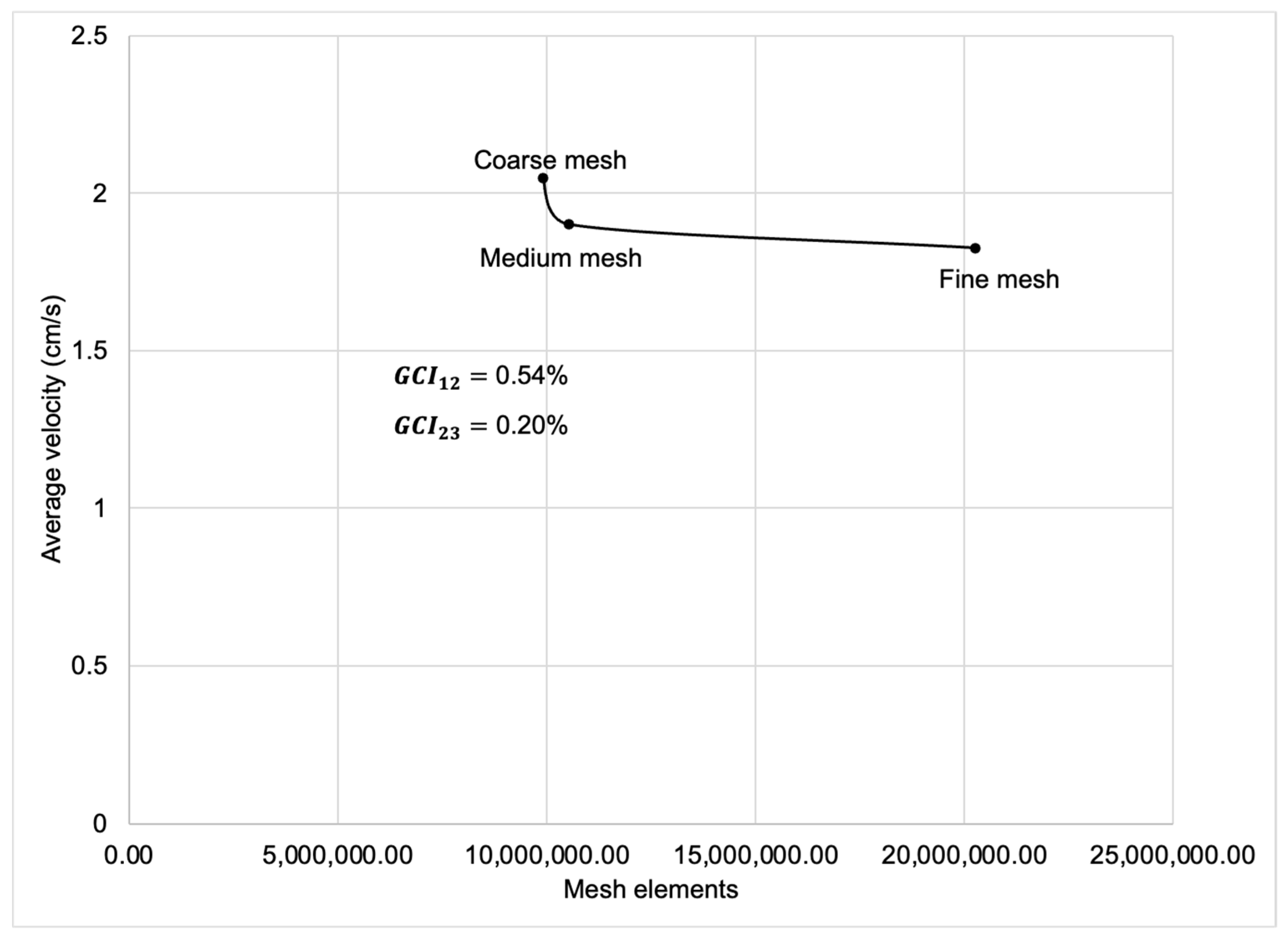

Spatial discretization was performed using a mesh composed of finite-volume hexahedral elements (Figure 4). For the computational analysis, three meshes with different spatial resolutions were generated, the characteristics of which are presented in Table 1 and Table 2. To ensure an optimal balance between computational cost and result accuracy, the medium-resolution mesh was selected as the basis for the numerical simulation.

Figure 4.

(A) Confined water volume, (B) Mesh detail of the fluid domain of the raceway.

Table 1.

Mesh characteristics.

Table 2.

Mesh medium properties.

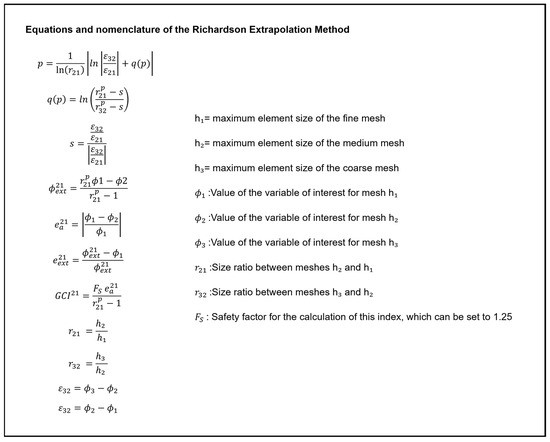

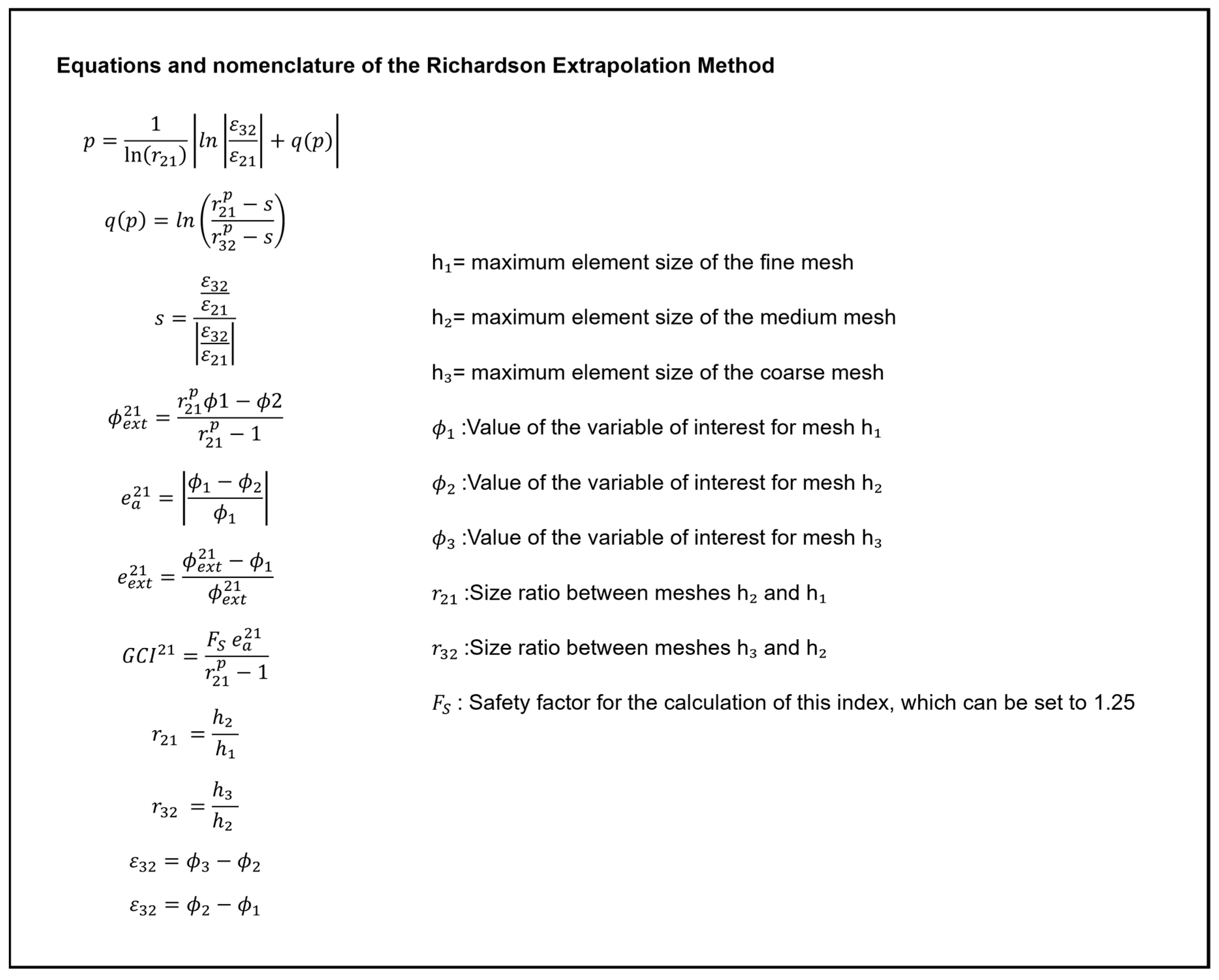

Mesh independence verification was conducted using the Richardson extrapolation method, confirming that the Grid Convergence Index (GCI) remained below 2% (Appendix A).

2.4. Simulation Conditions

For the implementation of the CFD model, the boundary conditions and initial parameter values were established according to the physical characteristics of the system, ensuring a realistic representation of the hydrodynamic processes and dissolved oxygen transport. Table 3 and Table 4 summarizes the conditions applied to each phase and zone of the model.

Table 3.

Boundary conditions and main parameters considered in the simulation.

Table 4.

Solution methods used in the model.

The convergence criterion was set at 1 × 10−6 for the continuity and momentum equations, and at 1 × 10−7 for the oxygen transport equations.

2.5. Simulation Validation

To validate the CFD model under real operating conditions, an independent experimental campaign was conducted directly in the full-scale raceway pond, using in situ dissolved oxygen (DO) measurements rather than a reduced physical model. The validation experiments were performed under the same hydraulic, thermal, and biomass conditions employed to parameterize the respirometry trials, including identical inlet flow rate, water temperature, and total fish biomass.

Spatial DO measurements were recorded at multiple locations along the length and depth of the pond using calibrated optical DO probes. The sensor positions were selected to match the representative monitoring points extracted from the CFD domain, enabling a direct point-to-point comparison between simulated and experimental concentrations [14].

The validation process consisted of comparing the experimentally measured DO values against the simulated predictions at corresponding spatial coordinates and operating conditions. Model performance was quantified based on the difference between the CFD-predicted and experimentally measured concentrations, providing an objective assessment of the level of agreement between both datasets. This approach allowed verification of the model’s capability to reproduce the spatial distribution patterns of dissolved oxygen resulting from the coupled hydrodynamic transport and biologically driven oxygen consumption within the real system.

3. Results and Discussion

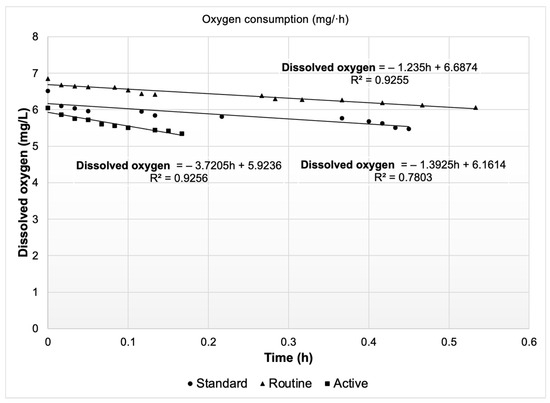

The initial results correspond to the first in situ experimental phase. Oncorhynchus mykiss exhibited differentiated DO consumption depending on the evaluated metabolic state. Figure 5 illustrates a progressive decline in dissolved oxygen concentration associated with the respiratory activity of the organisms during each metabolic condition, showing a continuous decrease pattern over time. This effect was most pronounced during the AMR/MMR state, where oxygen depletion occurred over a shorter time interval, reflecting a higher metabolic demand compared to the RMR and SMR states. This behavior is consistent with previous studies, in which oxygen consumption in salmonids has been shown to increase significantly with locomotor activity and metabolic stress [50,51,52,53].

Figure 5.

Variation in dissolved oxygen concentration (mg/L) over time (h) under different metabolic states of Oncorhynchus mykiss (standard, routine, and active).

The oxygen consumption values corresponding to the different metabolic states are presented in Table 5. These data directly reflect the implementation of the in situ method rather than an extrapolation based on individual or small-group measurements, as commonly occurs with traditional respirometers. Although the in situ respirometry approach adopted in this study is not frequently employed, the obtained oxygen consumption results are consistent with values reported in the literature [54,55,56].

Table 5.

Oxygen consumption of Oncorhynchus mykiss at different metabolic states.

This finding indicates that, despite being a robust estimation method, in situ respirometry provides reliable and practical information for assessing the current physiological state of biomass in a commercial aquaculture system. Such concordance suggests that in situ respirometry represents a strong alternative to traditional approaches, as it enables more representative estimations of DO consumption under real production scenarios. Laboratory measurements or those based on a limited number of individuals tend to underestimate intra-population variability and fail to adequately reflect the operational conditions of commercial aquaculture systems, potentially leading to biases in metabolic interpretation [55,57].

The interest in overcoming the limitations of conventional methods has driven the development of technologies that enable the application of respirometry under field conditions. Portable systems and mobile laboratories designed for in situ measurements have proven to be effective tools for obtaining continuous data that are comparable to those generated by traditional methods. These innovations not only facilitate real-time monitoring of oxygen consumption but also enhance producers’ ability to assess the physiological performance of populations under natural conditions [58,59,60,61].

These results not only confirm the sensitivity of oxygen consumption to different metabolic states but also provide essential quantitative data to strengthen the modeling and evaluation of the system through CFD analysis. The incorporation of these consumption rates enables the establishment of more accurate boundary conditions, which in turn allows for a faithful representation of oxygen distribution processes under various physiological scenarios. This connection between experimental measurement and numerical simulation is particularly relevant, as the validity of CFD models largely depends on the quality of the input data.

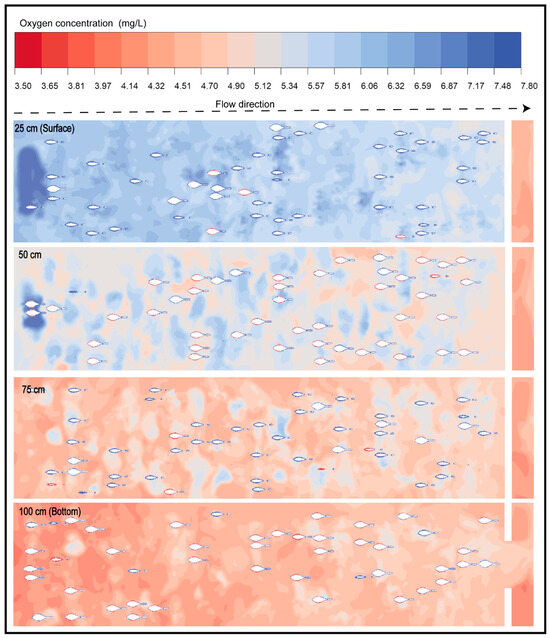

Through this modeling procedure, it was possible to identify the spatial patterns of DO distribution within the pond. In the specific case of the AMR/MMR state—considered the most critical phase for the organisms [62,63,64], Figure 6 reveals a generalized decline in DO levels throughout the system, with lower values observed in the deeper zones of the pond (75 and 100 cm), where critical concentrations below 5 mg/L are represented in reddish tones. This condition reflects an oxygen deficit that may induce severe physiological stress in the fish, affecting their growth, immunocompetence, and survival [4,65].

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of dissolved oxygen concentration (mg/L) under active metabolism in a raceway system at different depths.

Conversely, in the upper zones near the water surface (25 and 50 cm), regions with concentrations exceeding 6 mg/L were still recorded. However, the spatial distribution of DO remains limited and was primarily concentrated near the water inlet. This pattern corresponds to the competition between oxygen input (7.8 mg/L) and the high metabolic demand characteristic of the AMR/MMR state.

These results confirm that hydrodynamics directly influence the availability and distribution of DO, generating vertical microgradients that define potentially critical zones for the organisms [66,67,68]. The numerical simulation enabled visualization of these gradients with high spatial resolution, confirming that the CFD model is an effective tool for evaluating DO dynamics and anticipating hypoxia risks in high-density aquaculture systems [4,6].

Despite advances in numerical modeling, the scarcity of integrated approaches combining computational and experimental studies has limited the capacity to comprehensively understand the physical and biological factors governing DO dynamics. In this study, the explicit inclusion of fish within the simulations allowed for a more realistic representation of the operational conditions in aquaculture ponds by accounting for the interaction between biomass and flow dynamics. This integrative approach enabled the simultaneous analysis of the physical and biological processes determining oxygen distribution, thereby enhancing the understanding of the phenomena associated with mixing and collective metabolic consumption [69].

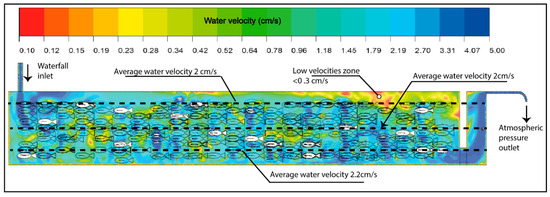

The implemented methodology demonstrated its capacity to describe in detail the zones of highest oxygen demand and their relationship with the system’s hydrodynamics (Figure 7), providing a solid quantitative basis for the management and optimization of aquaculture production units. In this context, the velocities recorded in the system were below 3 cm/s values considered low relative to the morphometric characteristics of the evaluated organisms. This range is below the recommended flow velocity of approximately 0.5 times the fish’s body length per second, a condition essential to promote health, muscular development, and efficient respiration [69,70].

Figure 7.

Water velocity in the raceway.

Furthermore, to achieve effective oxygenation and mixing within the pond, several authors suggest maintaining flow velocities above 10 cm/s, as this range promotes adequate oxygen transfer from the gaseous to the liquid phase and ensures a more homogeneous distribution of dissolved oxygen throughout the water column. Such conditions help prevent the formation of hypoxic zones and optimize mixing processes, ensuring a more stable environment for the cultured organisms [71,72,73,74,75].

This approach overcomes the limitations of simplified models employed in previous research, in which individual bodies or idealized configurations were analyzed without incorporating the actual metabolic demand of a production system [76,77,78,79]. Although more recent studies have advanced toward coupled simulations that consider group movement [80,81,82,83] or theoretical oxygen consumption [31], most of them do not integrate the simultaneous interaction among hydrodynamics, biomass, and respiration. In contrast, the simulation developed in this study, incorporating a representative biomass of 486 fish, enabled a comprehensive capture of stratification and collective consumption phenomena, providing a more accurate representation of DO behavior under production conditions.

Taken together, the results confirm that the application of computational fluid dynamics constitutes a robust tool for understanding and optimizing oxygenation processes in aquaculture systems. The capability to integrate both physical and biological factors within a single model allows not only visualization of the spatial distribution of DO but also identification of critical zones that could compromise oxygenation, health, and organism welfare.

Results Validation

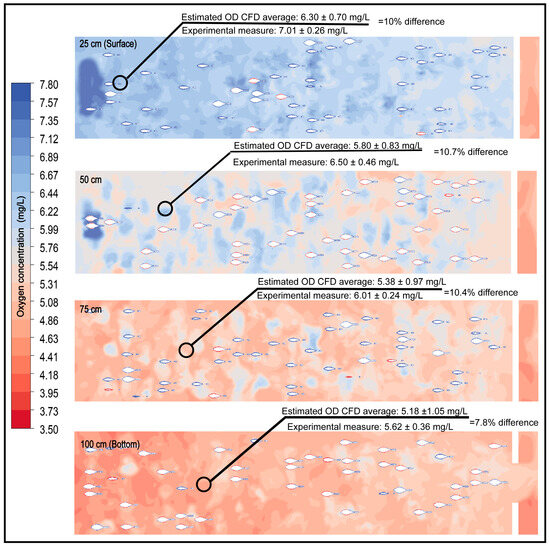

The integration of respirometry as an input for CFD-based numerical modeling yielded dissolved oxygen estimates with a high degree of agreement relative to experimental measurements (Figure 8). The percentage differences between the mean values at the pond’s central section for each depth and those observed during experimentation ranged from 7.8% to 10.7%, which is considered an acceptable range in validation studies of aquaculture systems [29,31,82,83,84,85].

Figure 8.

Comparison between the average central concentrations of dissolved oxygen (DO) obtained experimentally and those estimated through CFD simulation at different tank depths.

The proximity between simulated and experimentally measured values confirms the CFD model’s capability to accurately represent DO dynamics under real operational conditions. The validation in this study was based on point measurements collected at strategically selected locations within the raceway, chosen for their hydrodynamic and physiological relevance. This type of point-based validation is a common practice in CFD applications in aquaculture [14,86,87,88], particularly when the objective is to analyze critical zones where local DO gradients may develop and when continuous or high-resolution experimental monitoring is not feasible or would not provide substantial additional benefit. This level of agreement supports the inclusion of biomass and respirometry as essential components for predicting collective oxygen consumption, thereby improving the accuracy of carrying-capacity estimations for the system.

The results obtained in this study, which combine field experimental measurements with CFD modeling, have relevant practical implications for the operational management of dissolved oxygen in aquaculture production systems. The three-dimensional representation of hydrodynamic patterns and spatial DO gradients made it possible to identify low-velocity zones, recirculation areas, and regions where the metabolic demand of the fish increases the local risk of hypoxia [12,87]. This information is particularly valuable because it provides a spatial resolution that is difficult to achieve through traditional point-based monitoring campaigns.

From an applied perspective, the findings of the model allow the optimization of the placement and operation of aeration devices, since the critical zones with lower DO availability can be targeted more effectively [87,88], thereby reducing unnecessary energy use without compromising fish health. Likewise, the ability to visualize the spatial distribution of oxygen under different metabolic states of the fish provides an objective basis for adjusting biomass density and distribution, especially at times when metabolic activity increases oxygen demand.

Similarly, the hydrodynamic structure revealed by the simulation provides elements to improve the design and operation of recirculating systems, including the configuration of inlets and outlets, the internal geometry of the tank, and flow management in zones prone to stratification [5,67]. Finally, by enabling the evaluation of operational and biological scenarios prior to implementation, the integrated approach employed in this study serves as a robust tool to anticipate critical oxygen conditions, prevent mortalities, and strengthen evidence-based decision-making within intensive aquaculture systems.

From an applied perspective, this concordance has direct implications for production management. By comparing the minimum DO concentration obtained experimentally with the oxygen consumption corresponding to the evaluated metabolic state, the system’s maximum capacity—based on the estimated DO concentration—reaches 582 kg of biomass, whereas the theoretical value calculated from the DO concentration measured in the pond is 632.4 kg. This difference, equivalent to approximately 70.3 kg, demonstrates that small variations in dissolved oxygen concentration can result in significant changes in the system’s carrying capacity and, consequently, in overall production performance.

4. Conclusions

The computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations developed in this study enabled visualization of the spatial distribution of dissolved oxygen (DO) within a raceway-type aquaculture system. The results revealed a vertical stratification of DO, with concentrations reaching up to 6.5 mg/L in the surface layers and progressively decreasing toward the bottom, where values as low as 3.5 mg/L were recorded. This trend was attributed to the metabolic oxygen consumption by fish uniformly distributed throughout the pond, as well as to the inlet and outlet flow conditions, which generated local gradients and low-concentration zones, particularly in areas with high biomass density.

The incorporation of experimental data obtained through in situ respirometry strengthened the validity of the numerical results by providing direct and reliable estimates of oxygen consumption. This demonstrates that in situ respirometry constitutes a robust tool not only for assessing organism metabolism but also for calibrating CFD models in aquaculture applications.

Within this methodological framework—integrating respirometry and CFD simulation—it was possible to accurately reproduce real operational conditions, observing differences of up to 10.7% between experimental and simulated values. This representational capacity broadens the applicability of the model to various aquaculture production scenarios, complemented by its flexibility to modify system geometry, inlet and outlet flow configurations, and the quantity and spatial arrangement of cultivated biomass. Collectively, the validation results demonstrate that the model faithfully reproduces the dissolved oxygen behavior within the system, supporting its use as a decision-support tool for aquaculture management and production optimization.

Furthermore, this approach not only enhances oxygen management and the sustainability of production systems but also opens opportunities for new research avenues, enabling the evaluation of conditions involving higher metabolic demands or changing environmental scenarios—without compromising fidelity to real-world conditions.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, A.T.-R.; writing—review and editing, A.T.-R., I.G.-A. and B.M.L.-R.; conceptualization and supervision, D.G.-M., I.C.-Z., A.T.-R., I.G.-A., J.R.F.-F., R.A.-M. and B.M.L.-R.; translating, R.A.-M. and B.M.L.-R.; data curation, J.R.F.-F., D.G.-M., I.C.-Z., A.T.-R., I.G.-A. and B.M.L.-R.; formal analysis, J.R.F.-F., A.T.-R., I.G.-A. and B.M.L.-R.; investigation, A.T.-R., I.G.-A. and B.M.L.-R.; visualization, D.G.-M., I.C.-Z., J.R.F.-F. and R.A.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was reviewed and approved by the Research Department of the Secretariat for Research and Advanced Studies at the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, under approval code DOCAGM-00524, dated 17 January 2024. The organisms used in the study were the property of the “El Tepozan” Aquaculture Production Unit, and permission from the owners was obtained to conduct the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest to anybody or any organization.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DO | Dissolved Oxygen |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| SMR | Standard Metabolism |

| RMR | Routine Metabolism |

| AMR/MMR | Active/Maximum Metabolism |

Appendix A

Validation of Mesh Independence Using the Richardson Extrapolation Method

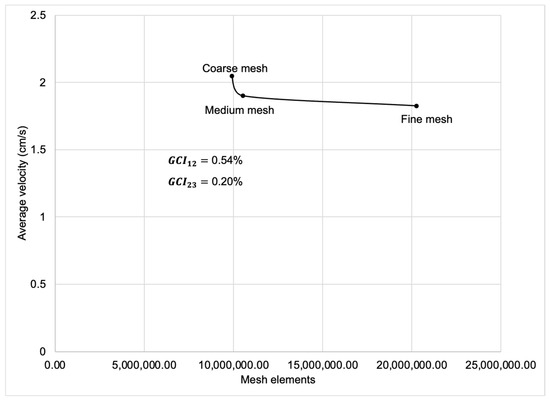

Figure A1.

Mesh elements comparison with average velocity, trough Richardson extrapolation method.

Figure A1.

Mesh elements comparison with average velocity, trough Richardson extrapolation method.

Figure A2.

Flowchart of the Richardson extrapolation method.

Figure A2.

Flowchart of the Richardson extrapolation method.

Figure A3.

Equations and nomenclature of the Richardson Extrapolation Method.

Figure A3.

Equations and nomenclature of the Richardson Extrapolation Method.

References

- Boyd, C.E.; Tucker, C.S. Handbook for Aquaculture Water Quality; Craftmaster Printers: Auburn, AL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Colt, J. Dissolved Gas Concentration in Water: Computation as Functions of Temperature, Salinity and Pressure; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Xu, D.; Jin, Y. Effects of Hypoxia on Growth, Immunity and Survival of Aquaculture Species: A Review. Aquaculture 2021, 541, 736850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntsson, E.V.C.; Stevik, T.K.; Bergheim, A.; Persson, D.; Stormoen, M.; Liland, K.H. Managing the dissolved oxygen balance of open Atlantic salmon sea cages: A narrative review. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, e12992. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, C.I.M.; Eding, E.H.; Verdegem, M.C.J.; Heinsbroek, L.T.N.; Schneider, O.; Blancheton, J.P.; d’Orbcastel, E.R.; Verreth, J.A.J. New Developments in Recirculating Aquaculture Systems in Europe: A Perspective on Environmental Sustainability. Aquac. Eng. 2010, 43, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colt, J. Water Quality Requirements for Reuse Systems. Aquac. Eng. 2006, 34, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihara, M.; Sakakura, Y. Dissolved Oxygen Dynamics in Aquaculture Ponds: Implications for Fish Physiology and Management. Aquac. Res. 2020, 51, 1467–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Luna, J.C.; Jaramillo-Peralta, D.A.; Julian-Laime, E.; Holgado-Apaza, L.A. IoT Based System for Monitoring Dissolved Oxygen and Temperature in Fish Larviculture. Agrária Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Agrár. 2023, 18, e3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotynski, R.; Marinelli, R.L. Water Quality Monitoring Framework Using IoT Sensors and Machine Learning for Pond Aquaculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 207, 107767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Kashem, M.A.; Alyami, S.A.; Moni, M.A. Monitoring Water Quality Metrics in Ponds Using IoT Sensors and Machine Learning for Predicting Fish Species Survival. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2023, 102, 104930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YSI Incorporated. Pro 20 Pro 20i User Manual. YSI Incorporated. 2016. Available online: https://www.ysi.com/File%20Library/Documents/Manuals/YSI_Pro20_Pro20i_User_Manual_English.pdf?srsltid=AfmBOopP98qG23KP_paRFrpLu2TyUc-CVwaJ5_IBupVPsJjeWJanng6J (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Oca, J.; Masaló, I. Flow Pattern in Rectangular Fish Tanks. Aquac. Eng. 2007, 37, 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, L.; Fu, L.; Wu, H.; Xia, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Tan, J.; Guo, Y. Modeling Dissolved Oxygen in a Crab Pond. Ecol. Model. 2021, 440, 109385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Ong, M.C.; Lee, J.; Kim, T. Numerical Simulation of Oxygen Transport in Land-Based Aquaculture Tank. Aquaculture 2021, 543, 736973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wambua, D.M.; Home, P.G.; Raude, J.M.; Ondimu, S. Environmental and Energy Requirements for Different Production Biomass of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) in Kenya. Aquac. Fish. 2021, 6, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.; Paing, S.T.; Wakes, S.; Vennell, R.; Rhone, S.; Kregting, L.; Black, S. The Influence of Length–Width Ratio of an Unconventional Mobile Finfish Structure on the Drag Force and Dissolved Oxygen: Laboratory Experimentation and Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). Aquac. Eng. 2025, 110, 102538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.; Summerfelt, S. Solids Flushing, Mixing, and Water Velocity Profiles within Large (10 and 150 m3) Circular “Cornell-Type” Dual-Drain Tanks. Aquac. Eng. 2004, 32, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Xie, Y.; Zhu, D.; Xie, J. Modeling Re-Oxygenation Performance of Fine-Bubble–Diffusing Aeration System in Aquaculture Ponds. Aquac. Int. 2019, 27, 1353–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Patiño, M.A.; Hernández, D.R.; González, L.D. Hydraulic and Hydrodynamic Characterization of Fish Raceways Using CFD. Aquac. Eng. 2021, 95, 102164. [Google Scholar]

- Cripps, S.J.; Bergheim, A. Solids Management and Removal for Intensive Land-Based Aquaculture Production Systems. Aquac. Eng. 2000, 22, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, P.; Guerrero, N.; Sobarzo, M.; Sepúlveda, H.H. Hydrodynamic Modification in Channels Densely Populated with Aquaculture Farms. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, M.B.; Guerdat, T.C.; Vinci, B.J. Recirculating Aquaculture, 4th ed.; Ithaca Publishing Company: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Xue, B.; Ren, X.; Ye, Z.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Q. Influence of Inlet Placement on the Hydrodynamics of the Dual-Drain Arc Angle Tank for Fish Growth. Aquac. Eng. 2023, 101, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Rebollar, B.M.; Salinas-Tapia, H.; García-Pulido, D.; Durán-García, M.D.; Gallego-Alarcón, I.; Fonseca-Ortiz, C.R.; Díaz-Delgado, C. Performance Study of Annular Settler with Gratings in Circular Aquaculture Tank Using Computational Fluid Dynamics. Aquac. Eng. 2021, 92, 102143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Lee, S.; Baek, S.; Lee, S.; Seo, J.; Shin, D.; Sung, Y. Numerical Analysis of Thermal and Hydrodynamic Characteristics in Aquaculture Tanks with Different Tank Structures. Ocean Eng. 2023, 287, 115880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.; Cho, S.; Jeon, W.; Kim, Y.; Kwon, K.; Jeong, D.Y. Recirculating Aquaculture System Design and Water Treatment Analysis Based on CFD Simulation. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2023, 17, 3083–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oca, J.; Masaló, I.; Reig, L. Comparative Analysis of Flow Patterns in Aquaculture Rectangular Tanks with Different Water Inlet Characteristics. Aquac. Eng. 2004, 31, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ren, X.; Liu, C.; Shi, X.; Gui, J.; Bi, C.; Xue, B. The Influence Study of Inlet System in Recirculating Aquaculture Tank on Velocity Distribution. In Proceedings of the 29th International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 16–21 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Li, D.; Li, W.; Wang, Y. Numerical Investigations on Dissolved Oxygen Field Performance of Octagonal Culture Tank Based on Computational Fluid Dynamics. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 218, 108737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Jia, C.; Gui, F.; Xu, J.; Yin, X.; Feng, D.; Zhang, Q. Recent Advances in the Hydrodynamic Characteristics of Industrial Recirculating Aquaculture Systems and Their Interactions with Fish. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, V.; Parrella, L.; Falcucci, M. Modelling Dissolved Oxygen Dynamics in Coastal Lagoons. Ecol. Model. 2008, 211, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Chen, J. Computational Modeling of Fish Oxygen Consumption in Intensive Aquaculture Tanks. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 207, 107713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Ma, M.; Guo, Y.; Li, R. Investigation of Flow Field and Dissolved Oxygen Concentration Distribution in Aquaculture Tanks Based on Computational Fluid Dynamics. Aquac. Eng. 2025, 111, 102577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.D.; Sandblom, E.; Jutfelt, F. Aerobic Scope Measurements of Fishes in an Era of Climate Change: Respirometry, Relevance and Recommendations. J. Exp. Biol. 2013, 216, 2771–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabot, D.; Steffensen, J.F.; Farrell, A.P. The Determination of Standard Metabolic Rate in Fishes. J. Fish Biol. 2016, 88, 81–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lighton, J.R.B. Measuring Metabolic Rates: A Manual for Scientists; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen, J.F. Some Errors in Respirometry of Aquatic Breathers: How to Avoid and Correct for Them. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 1989, 6, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, M.B.S.; Bushnell, P.G.; Steffensen, J.F. Sources of Variation in Oxygen Consumption of Aquatic Animals Demonstrated by Simulated Constant Oxygen Consumption and Respirometers of Different Sizes. J. Fish Biol. 2016, 89, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, M.B.S.; Bushnell, P.G.; Steffensen, J.F. Design and Setup of Intermittent-Flow Respirometry System for Aquatic Organisms. J. Fish Biol. 2016, 88, 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, E.F.; Krause, S.L.; Santos, L.M.; Naumann, M.S.; Kikuchi, R.K.; Smith, D.J.; Suggett, D.J. The “Flexi-Chamber”: A Novel Cost-Effective In Situ Respirometry Chamber for Coral Physiological Measurements. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norin, T.; Malte, H.; Clark, T.D. Differential Plasticity of Metabolic Rate Phenotypes in a Tropical Fish Facing Environmental Change. Funct. Ecol. 2016, 30, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, M.D.; Mandic, M.; Dhillon, R.S.; Lau, G.Y.; Farrell, A.P.; Schulte, P.M.; Richards, J.G. Don’t Throw the Fish Out with the Respirometry Water. J. Exp. Biol. 2019, 222, jeb200253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt von Herbing, I.; Pan, T.C.; Méndez-Sánchez, F.; Garduño-Paz, M.; Hernández-Gallegos, O.; Ruiz-Gómez, M.D.L.; Rodríguez-Vargas, G. Chronic Stress of Rainbow Trout Oncorhynchus mykiss at High Altitude: A Field Study. J. Fish Biol. 2015, 87, 138–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, G.G.; Tenzing, P.; Clark, T.D. Experimental Methods in Aquatic Respirometry: The Importance of Mixing Devices and Accounting for Background Respiration. J. Fish Biol. 2016, 88, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killen, S.S.; Christensen, E.A.F.; Cortese, D.; Závorka, L.; Norin, T.; Cotgrove, L.; Papatheodoulou, M. Guidelines for Reporting Methods to Estimate Metabolic Rates by Aquatic Intermittent-Flow Respirometry. J. Exp. Biol. 2021, 224, jeb242522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Li, D.; Wang, Y. Investigation on Aeration Efficiency and Energy Efficiency Optimization in Recirculating Aquaculture Coupling CFD with Euler–Euler and Species Transport Model. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Ma, M.; Guo, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, R. Effect of Flow Rate and Dissolved Oxygen Distribution on Aeration of Recirculating Aquaculture Tank. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 234, 110290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, R.A.; Shiddiqie, H.L.A.; Ahmad, H.N.; Nugroho, A.N.A. CFD Simulation on the Flow inside a Fish Culture Tank. J. Inotera 2022, 7, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerezo-Valverde, J.; García-García, B. Influencia del Peso y la Temperatura sobre el Consumo de Oxígeno de Rutina del Dentón Común (Dentex dentex Linnaeus, 1758). Rev. Aquat. 2004, 21, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Claireaux, G.; Chabot, D. Responses by Fishes to Environmental Hypoxia: Integration through Fry’s Concept of Aerobic Metabolic Scope. J. Fish Biol. 2016, 88, 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldrop, T.; Summerfelt, S.; Mazik, P.; Kenney, P.B.; Good, C. The Effects of Swimming Exercise and Dissolved Oxygen on Growth Performance, Fin Condition and Survival of Rainbow Trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. Aquac. Res. 2020, 51, 2582–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, J.; Wood, C.M. The First Direct Measurements of Ventilatory Flow and Oxygen Utilization after Exhaustive Exercise and Voluntary Feeding in a Teleost Fish, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 49, 1129–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsson, H.; Svendsen, M.B.S.; Steffensen, J.F. Model of Oxygen Conditions within Aquaculture Sea Cages. Biology 2023, 12, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claireaux, G.; Couturier, C.; Groison, A.L. Effect of Temperature on Maximum Swimming Speed and Cost of Transport in Juvenile European Sea Bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). J. Exp. Biol. 2006, 209, 3420–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royer, E.; Faccenda, F.; Pastres, R. Estimating Oxygen Consumption of Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in a Raceway: A Precision Fish Farming Approach. Aquac. Eng. 2021, 92, 102141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArley, T.J.; Morgenroth, D.; Zena, L.A.; Ekström, A.T.; Sandblom, E. Normoxic Limitation of Maximal Oxygen Consumption Rate, Aerobic Scope and Cardiac Performance in Exhaustively Exercised Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). J. Exp. Biol. 2021, 224, jeb242614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinzing, T.S.; Zhang, Y.; Wegner, N.C.; Dulvy, N.K. Analytical Methods Matter Too: Establishing a Framework for Estimating Maximum Metabolic Rate for Fishes. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 9987–10003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetti, R.; Chamberlin, C.; Dey, A.; Jones, D.R.; Luthy, M.; Cunjak, R.A. Metabolic Rates of Rainbow Trout Eggs in Reconstructed Salmonid Egg Pockets. Water 2024, 16, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochnacz, N.J.; Kissinger, B.C.; Deslauriers, D.; Guzzo, M.M.; Enders, E.C.; Anderson, W.G.; Treberg, J.R. Development and Testing of a Simple Field-Based Intermittent-Flow Respirometry System for Riverine Fishes. Conserv. Physiol. 2017, 5, cox048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.J.; Harris, L.N.; Malley, B.K.; Schimnowski, A.; Moore, J.S.; Farrell, A.P. The Thermal Limits of Cardiorespiratory Performance in Anadromous Arctic Char (Salvelinus alpinus): A Field-Based Investigation Using a Remote Mobile Laboratory. Conserv. Physiol. 2020, 8, coaa036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, A.G.; Dressler, T.; Kraskura, K.; Hardison, E.; Hendriks, B.; Prystay, T.; Eliason, E.J. Maxed Out: Optimizing Accuracy, Precision, and Power for Field Measures of Maximum Metabolic Rate in Fishes. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2020, 93, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treberg, J.R.; Killen, S.S.; MacCormack, T.J.; Lamarre, S.G.; Enders, E.C. Estimates of Metabolic Rate and Major Constituents of Metabolic Demand in Fishes under Field Conditions: Methods, Proxies, and New Perspectives. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2016, 202, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakoso, V.A.; Chang, Y.J. Metabolic Rates (SMR, RMR, AMR, and MMR) of Oplegnathus fasciatus on Different Temperature and Salinity Settings. Indones. Aquac. J. 2018, 13, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raby, G.D.; Doherty, C.L.J.; Mokdad, A.; Pitcher, T.E.; Fisk, A.T. Post-Exercise Respirometry Underestimates Maximum Metabolic Rate in Juvenile Salmon. Conserv. Physiol. 2020, 8, coaa063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.W.; Dalton, D.A.; Kramer, S.; Christensen, B.L. Physiological (Antioxidant) Responses of Estuarine Fishes to Variability in Dissolved Oxygen. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2001, 130, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerfelt, S.T.; Davidson, J.; Wilson, J.; Waldrop, T. Advances in Fish Harvest Technologies for Circular Tanks. Aquac. Eng. 2009, 40, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, M.B.; Ebeling, J.M. Recirculating Aquaculture, 3rd ed.; Ithaca Publishing: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Losordo, T.M.; Westers, H. System Carrying Capacity and Flow Estimation. In Aquaculture Water Systems: Engineering Design and Management; Timmons, M.B., Losordo, T.M., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 9–60. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, B.; Zhao, Y.; Bi, C.; Cheng, Y.; Ren, X.; Liu, Y. Investigation of Flow Field and Pollutant Particle Distribution in the Aquaculture Tank for Fish Farming Based on Computational Fluid Dynamics. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 200, 107652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Rebollar, B.M. Aplicación de CFD-ANSYS-FLUENT en el Estudio Hidrodinámico de Tanques de Recirculación Empleados en Acuacultura. Master’s Thesis, Centro Interamericano de Recursos del Agua, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, Toluca, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, J.; Good, C.; Welsh, C.; Brazil, B.L.; Summerfelt, S. Heavy Metal and Waste Metabolite Accumulation and Their Affect on Rainbow Trout Performance in a Replicated Water Reuse System Operated at Low or High System Flushing Rates. Aquac. Eng. 2009, 41, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerfelt, S.T.; Vinci, B.J. Better Management Practices for Recirculating Aquaculture Systems. In Environmental Best Management Practices for Aquaculture; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 389–426. [Google Scholar]

- Timmons, M.B.; Ebeling, J.M. Recirculating Aquaculture, 2nd ed.; Cayuga Aqua Ventures, LLC.: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Adkins, D.; Yan, Y.Y. CFD Simulation of Fish-Like Body Moving in Viscous Liquid. J. Bionic Eng. 2006, 3, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palit, S.; Sinha, S.; Britto, R.A.; Selvakumar, A. CFD Analysis of Flow around Fish. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1276, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, K.; Takagi, T.; Mitsunaga, Y.; Torisawa, S. Hydrodynamical Effect of Parallelly Swimming Fish Using Computational Fluid Dynamics Method. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Nagy, M.; Graving, J.M.; Bak-Coleman, J.; Xie, G.; Couzin, I.D. Vortex Phase Matching as a Strategy for Schooling in Robots and in Fish. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Ren, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Li, M. Numerical Modeling and Application of the Effects of Fish Movement on Flow Field in Recirculating Aquaculture System. Ocean Eng. 2023, 285, 115432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xue, B.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Du, S. Numerical Simulation of Bionic Fish Group Movement in a Land-Based Aquaculture Tank. Aquac. Eng. 2024, 104, 102388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winthereig-Rasmussen, H.; Simonsen, K.; Patursson, Ø. Flow through Fish Farming Sea Cages: Comparing Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulations with Scaled and Full-Scale Experimental Data. Ocean Eng. 2016, 124, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khater, E.S.; Bahnasawy, A.; El-Ghobashy, H.; Shaban, Y.; Elsheikh, F.; El-Reheem, S.A.; Aboegela, M. Mathematical Model for Predicting Oxygen Concentration in Tilapia Fish Farms. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, T.; Kamath, A.; Wang, G.; Bihs, H. Modelling Open Ocean Aquaculture Structures Using CFD and a Simulation-Based Screen Force Model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, D.; Song, J.; Bao, E.; Wang, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Wu, Z. Numerical Calculation and Experimental Analysis of Thermal Environment in Industrialized Aquaculture Facilities. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isiordia-Pérez, J.E.; Isiordia-Cortez, A. Dissolved oxygen concentration in a experimental culture system of tilapia Oreochromis niloticus using floating cages. Rev. Acta Pesquera. 2024, 54, 6112–6124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwegoha, W.J.S.; Kaseva, M.E.; Sabai, S.M.M. Mathematical Modeling of Dissolved Oxygen in Fish Ponds. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 4, 625–638. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, D.; Li, T. Numerical Investigation on Hydrodynamics and Dissolved Oxygen Distribution in Recirculating Aquaculture Raceways. Aquac. Eng. 2021, 92, 102147. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Li, T.; Yan, B.; Chen, Y. Optimization of Aeration Efficiency in Intensive Aquaculture Ponds Using CFD Simulations. J. Hydrodyn. 2020, 32, 801–811. [Google Scholar]

- Su, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, H.; Li, D. Investigation on Aeration Efficiency and Energy Optimization in Recirculating Aquaculture Systems Using CFD. Aquac. Eng. 2023, 100, 102349. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.