Abstract

There is a need to develop comprehensive guidelines to encourage the promotion of oral hygiene care among older adults and to assist caregivers in this endeavor, taking into consideration the specific challenges that arise from aging, comorbidities and caregiving. This review was conducted by searching across relevant literature from meta-databases including Academic Google, PubMed, Scielo and Scopus for studies published from 2020 to 2024. PRISMA guidelines were followed. We included articles that described oral hygiene methods, caregiver education and mechanization status of older adults. Common themes, best practices, and gaps in current guidelines were tracked using extracted and analyzed data. The review revealed multiple factors affecting the oral hygiene of older adults, with themes relating to physical impairment, cognitive dysfunction, and caregiver involvement. Highlighted between the approaches are individualized therapy for oral hygiene, caregiver education, and the use of technology to improve adherence to oral hygiene. Barriers like dental care access, underlying medical conditions complicating dental treatments, and cost considerations were identified. The findings emphasize the necessity of clear recommendations that can help caregivers and advance dental care for older adults.

1. Introduction

Public health faces escalating challenges because worldwide, population aging advances forward [1,2]. From the perspective of the current context, it is essential to aim for the preservation of a satisfactory oral health condition in the elderly population. For this reason, the United Nations and the World Health Organization (WHO) allocated the years between 2021 and 2023 as the Decade of Healthy Aging with an intent to encourage concerted action to promote longer, healthier lives [3].

Insufficient oral care among older adults not only affect oral health but also has far-reaching biological, psychological, social, and economic consequences [4,5]. From a biological standpoint, deficient oral hygiene may cause infections and chronic diseases, greatly impairing quality of life and personal autonomy [6,7]. Psychologically, this leads to depression and anxiety, compounding self-esteem issues [8]. Oral health reflects socioeconomic status, educational background and self-care habits. It shapes hygiene practices, self-esteem and social inclusion, while also exposing disparities in access to preventive care and essential treatments [8,9]. Furthermore, the economic loss of handling these affairs might be significant for both people and public health systems [7,10,11]. Improving their oral hygiene is a critical factor for healthy aging and richer quality of life among seniors.

The WHO defines people over 60 as older persons even if they show physical and mental decline due to any cause [3]. In certain countries, people start categorizing individuals as senior citizens at 65 because of social security norms regarding retirement and insurance benefits [12].

It is important to practice oral hygiene, which can be taken in order to prevent the mouth from being infected and unhygienic [13], and is essential to prevent oral and systemic disease that are more common among older people. Some of the care includes brushing and flossing and check-ups at the dentist for checks and cleanings [14].

Oral diseases can have a very unfavorable effect on general health, life quality, and the ability of older people to swallow and talk [15,16]. However, a number of older people have severe impairments, intellectual disability, and poor access to oral care that makes it difficult to practice good oral hygiene [17,18].

Caregivers are healthcare professionals, family members, friends, social workers or members of religious organizations who provide assistance at home, in the hospital, or other health institutions. They are also known as the people who are responsible for the patient [19].

The importance of supporting the oral hygiene of older adults is also extended to caregivers so that specific education and resources for this group are needed. Training caregivers is also crucial to make sure that older adults get the right oral care and can maintain good oral health. In this context, studies often highlight that oral care training for caregivers is inconsistent and underdeveloped [15,16,18]. Researchers emphasize the need for standardized, evidence-based training programs.

2. Objective, Focus and Scope of This Review

This systematic review intends to aggregate and synthesize the body of literature pertaining to oral hygiene practices among older adults and the education of their caregivers. The objective of this research is to emphasize key factors that affect oral hygiene, identify exemplary practices, and propose recommendations for forthcoming research initiatives.

In line with the requirements of a systematic review [20], a preliminary protocol was developed that included a comprehensive literature search, organized data extraction and steps to ensure internal reliability. The target audience for this review are healthcare professionals such as dentists, dental hygienists, nurses, and doctors who work with older adults. Additionally, it would also be appropriate for caregivers of older adults, whether they are family members, friends, or professionals providing care in home or healthcare settings. Public health organizations, researchers in the field of oral health organizations, researchers in the field of oral health, and those interested in promoting the health and well-being of older adults could also find this review suitable.

Through this review, the authors aspire to provide a comprehensive overview of the present knowledge in this field and to improve the oral health of the elderly population.

3. Materials and Methods

This systematic review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews PROSPERO (Registration number: CRD420251053701) and based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analysis (PRISMA) 2020 guideline [21].

In this systematic review, three questions were addressed:

- (1)

- What is the impact of caregiver training on improving oral hygiene practices among the elderly population?

- (2)

- How does the level of caregiver training impact the effectiveness of oral hygiene procedures in older adults, considering their level of cognitive function and motor skills?

- (3)

- What educational strategies have been proven the most effective in improving the relationship between caregiver training and quality of oral hygiene care of older adults?

This review focused on the significance of an adequate oral hygiene care for older adults, highlighting the necessity for comprehensive education and training for caregivers in order to improve the overall oral health and well-being of this population.

3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Individual studies were included in the review if they (i)were peer-reviewed primary studies (e.g., randomized trials, observational studies, mix methods designs); (ii) reported on individuals 60 and older; (iii) pertained to oral hygiene methods, caregiver education and the mechanization status of older adults; (iv) were published in the English and Spanish language.

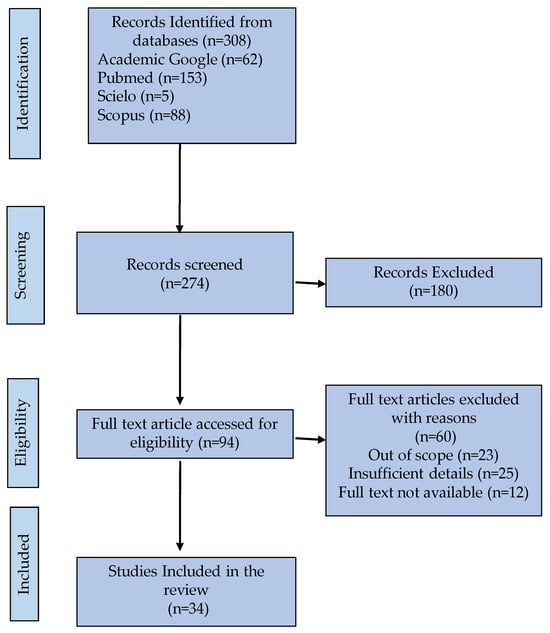

Studies were excluded if they (i) consist of non –peer- reviewed literature; (ii) reported on individuals under the age of 60; (iv) do not simultaneously address both oral hygiene strategies and either caregiver education programs or assistive technologies, (iii) were not written in the English and Spanish language; (v) were published as only abstracts or posters or were unpublished work. Figure 1 presented the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this review.

3.2. Search Strategy

The review was conducted by searching relevant literature from meta-databases, including Academic Google, PubMed, Scielo and Scopus for studies published from 2020 to 2024. Articles that described oral hygiene methods, caregiver education and the mechanization status of older adults were included.

Mechanization refers to the various levels of assistance provided by devices or technologies that support users in their daily activities. As individuals age, they frequently experience a decline in physical abilities and mental acuity, leading them to seek external assistance to accomplish their activities. Common themes, best practices, and gaps in current guidelines were identified through the extraction and analysis of data. In this research, we employed a strategic selection of keywords, including “aged”, “frail elderly”, “healthy aging”, “oral hygiene”, “oral health”, “oral medicine”, “caregivers”, “family member”, “nursing staff”, “education”, “assistive technology” and “assistive device”. Additionally, we utilized Boolean logical operators such as “AND”, and “OR” to refine our search and enhance the relevance of the retrieved literature. A summary of the MeSH terms and keywords used for the search strategy is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the MeSH terms and keywords.

3.3. Study Records

3.3.1. Data Management/Selection Process

Search results were exported to Endnote (Clarivate Analytics (US) LLC, London, UK) and duplicates removed. Records were then exported to Rayyan [22], whereby two independent reviewers screened all titles, abstracts, and full texts against the predetermined eligibility criteria. Any disagreements regarding inclusion were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers. When consensus was not reached, a third reviewer (A.N.) was consulted.

3.3.2. Data Extraction

Data were extracted by the independent reviewers using a predefined data extraction proforma. The form included the following information: author (s) and year of publication; aim and objectives; study design; results; conclusions; recommendations/gaps in research.

3.3.3. Data Synthesis

A synthesis was informed using the Arksey and O’Malley framework [23]. The six-stage framework was applied to this study as follows: identifying the research question; identifying relevant studies; study selection; charting de data; collating; summarizing and reporting the results. Results were summarized to present an overview of the evidence, and quantitative and qualitative analyses were used to describe study characteristics. These analyses allowed major themes to be identified and redefined (D.M.A., S.B. and A.N.) and gaps in the literature to be identified.

3.3.4. Assessment of Study Quality

The methodological quality of the studies included in this review was assessed using tools validated for each study design. The (Table 2) 2018 version of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [24] was used for qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies and the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RoB-1) [25], from randomized controlled trials.

The search and selection process was thorough and based on clear criteria; however, a moderate risk of bias was identified due to language restrictions and exclusion of gray literature or unpublished studies. Three studies exhibited a high risk of bias, mainly due to lack randomization, no blinding and no control group. Five studies had moderate concerns due to quasi-experimental designs and incomplete reporting, and the heterogeneity of interventions and outcomes made direct comparisons and quantitative synthesis impossible.

Also, the prevalence of self-reported outcomes, short follow-up durations, and small sample sizes limited external validity and long-term effects. Selective reporting and publication bias were also noted.

The methodological quality and risk of bias for each included study was rated using a star system adapted from established tools [26]. This system considers factors such as study design, sample size, presence of control group, blinding, and completeness of data:

- –

- ★★★★★ (five stars): High quality, low risk of bias; robust methodology (e.g., randomized controlled trials with proper randomization and blinding).

- –

- ★★★★☆ (four stars): Good quality, moderate risk of bias; most methodological criteria met with minor limitations.

- –

- ★★★☆☆ (three stars): Moderate quality, notable risk of bias; small sample size, no control group, or short follow-up.

- –

- ★★☆☆☆ (two stars): Low quality, high risk of bias; significant methodological weaknesses (e.g., uncontrolled design, incomplete data).

- –

- ★☆☆☆☆ (one star): Very low quality, very high risk of bias; not enough evidence to draw conclusions.

In addition to applying validated appraisal tools such as the MMAT and the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool, we carefully considered the inherent limitations of observational studies included in this review. Many relied heavily on self-reported outcomes, single-institution samples, or cross-sectional designs, which introduce risks of recall bias, selection bias, and limited external validity. By incorporating a star-based quality rating system, we aimed to transparently differentiate between high-quality randomized trials and studies with moderate to high risks of bias, particularly within the observational category.

In summary, the overall risk of bias in this review is moderate to high, so the findings are not very certain.

4. Results

The findings of this systematic review highlight critical gaps and opportunities in oral hygiene care for older adults and the role of caregiver education. By synthesizing evidence from 34 studies across diverse geographic and institutional settings, this review accentuates the interplay between systemic barriers, caregiver preparedness, and the efficacy of educational interventions (Figure 1). Below, these findings are contextualized within current literature, their broader implications are explored, and actionable guidelines for future research are proposed.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection, exclusion and inclusion within the systematic review (PRISMA) [21].

Table 2.

Study characteristics of included studies.

Table 2.

Study characteristics of included studies.

| Reference Year | Study Design | Setting | Country | Participants (n, Age, caregiver Type) | Intervention (+Technology/Comparator) | Key Results | Limitations | Quality/Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aquilanti et al. [27] | Systematic review of studies on teledentistry | Community and domiciliary settings, residential aged care facilities | Various countries (studies from multiple settings internationally) | Elderly participants across included studies; sample sizes and caregiver types varied by study | Teledentistry interventions including remote consultations, telemonitoring, education, and oral health assessments; comparator usually usual care or no intervention | Teledentistry is feasible and can improve access to dental care for elderly populations

| Heterogeneity of included studies and interventions

| ★★★☆☆ Moderate quality due to heterogeneity and methodological limitations of included studies; moderate confidence in findings but limited by variability and few high-quality RCTs. |

| Brady et al. [28] | Pragmatic, multicenter, stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial (pilot) | 4 stroke rehabilitation wards | Scotland, UK | 325 patients (median age 76 years, range approx. 63–83), nursing staff (112 nurses) | Enhanced oral healthcare intervention: online training for nursing staff, oral health protocols, assessment tools, oral care equipment and products; Comparator: usual oral healthcare | No significant difference in stroke-associated pneumonia incidence (p = 0.62); no difference in dental plaque or oral health-related quality of life; intervention feasible and safe; poor oral healthcare documentation noted | Pilot study with small sample size; variability between sites; inability to blind staff and outcome assessors; poor oral healthcare documentation; limited power to detect differences in pneumonia. | ★★★★☆ (solid design and appropriate analysis, with a moderate risk of bias mainly due to the impossibility of blinding and the need for careful analysis to control temporal trends). |

| Hernández-Santos and Díaz-García [29] | Intervention study with pre- and post-test design | Rest house for older adults | Mexico | 6 older adults (all women), mean age 82.5 ± 9.7 years; caregivers (type not specified, likely informal or institutional) | Weekly educational sessions on oral health for caregivers; no technology reported; comparator: baseline (pre-intervention) | Oral hygiene improved by 33.72% measured by simplified oral hygiene index; significant positive impact of caregiver education on elderly oral hygiene | Small sample size; no control group; short follow-up; limited generalizability | ★★★☆☆ (moderate risk of bias due to small sample size, lack of control group, and limited follow-up) |

| Girestam Croonquist et al. [30] | Randomized controlled trial (RCT), evaluator-blinded, open-ended design | 9 nursing homes | Sweden | 146 residents (mean age not specified, dependent older adults), caregivers: nursing home staff | Intervention: Monthly professional cleaning and individualized oral hygiene education by dental hygienists (RDHs). Comparator: usual daily oral care (self-care or assisted by nursing staff) | Significant improvements in oral hygiene (mucosal-plaque score, gingival bleeding), reduction in root caries in intervention group. Nursing staff showed improved knowledge and attitudes towards oral care after intervention | Follow-up limited to 6 months, possible bias due to lack of full blinding of participants and staff, limited generalizability to other countries or settings | ★★★★☆ (good quality with a moderate risk of bias mainly due to the impossibility of complete blinding) |

| Zimmerman et al. [31] | Cluster randomized controlled trial (cluster RCT) | 14 nursing homes (7 intervention, 7 control) | United States | 2152 residents (mean age 79.4 years; 66.2% women; caregivers: nursing home staff) | No significant reduction in pneumonia incidence over 2 years (IRR 0.90, p = 0.27); however, significant reduction during first year in adjusted post hoc analysis (IRR 0.69, p = 0.03). Improved staff knowledge and attitudes towards oral care. | No significant reduction in pneumonia incidence over 2 years (IRR 0.90, p = 0.27); however, significant reduction during first year in adjusted post hoc analysis (IRR 0.69, p = 0.03). Improved staff knowledge and attitudes towards oral care | Lack of sustained effect at 2 years possibly due to challenges in maintaining intervention fidelity; inability to blind participants and staff; generalizability limited to similar settings | ★★★★☆ (good quality with moderate risk of bias, mainly due to the impossibility of complete blinding and challenges in maintaining the intervention over the long term). |

| Díaz-Méndez and Huerta-Fernández. [32] | Protocol development/descriptive study | Long-term care facilities for older adults (ELEAM) | Chile | Institutionalized older adults (number and age not specified); caregivers and healthcare personnel | Oral hygiene protocol adapted for COVID-19 pandemic, including infection control measures, use of PPE, oral hygiene techniques to prevent aspiration pneumonia; no comparator | Provides detailed, practical hygiene protocol emphasizing prevention of aspiration pneumonia and infection control during COVID-19; highlights importance of caregiver training | No empirical data or evaluation of protocol effectiveness; descriptive only; no sample size or outcome measures | ★☆☆☆☆ (very high risk of bias due to descriptive protocol design without empirical data or outcome evaluation). |

| Wu et al. [33] | Pilot randomized controlled feasibility study (two-group pretest-posttest design) | Community-dwelling older adults with cognitive impairment; recruited from memory clinic and caregiver support groups | United States | 25 older adults (≥ 60 years) with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia; along with their informal caregivers (care partners); Treatment Group 1 (n = 7), Treatment Group 2 (n = 18) | Treatment Group 1: education with brochure and electric toothbrush. Treatment Group 2: brochure, personalized care plan, 4 coaching sessions for caregivers, and electric toothbrush. No traditional control group. |

|

| ★★★☆☆ (moderate quality; pilot experimental study with small sample size, no blinding, and no control group) |

| Oliveira et al. [34] | Cross-sectional | Home visits by primary care teams | Brazil | 238 homebound older adults; majority with informal caregivers, some with professional caregivers; age not specified | None (descriptive study, no intervention or comparator) |

|

| ★★☆☆☆ Descriptive cross-sectional study with non-probabilistic sampling; no control group or formal bias assessment; limited generalizability and causal inference. |

| Godoy et al. [35] | Quantitative, observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study | Elderly long-term care facilities (ELEAM) | Chile (Antofagasta) | 49 caregivers (all women); age not specified; formal caregivers in institutional setting | No intervention; assessment of oral health care beliefs using DCBS-sp questionnaire; no technology; comparator: none | 36.7% had oral health training; 97.96% perceived need for training; caregivers with training showed significantly more favorable beliefs regarding internal locus of control and self-efficacy | Cross-sectional design limits causality; self-reported data; no intervention tested; limited generalizability outside context | ★★★☆☆ (moderate risk of bias due to observational design and self-report measures). |

| Ryu et al. [36] | Before–After Interventional Study | Long-term care hospital | Japan | 37 elderly inpatients (mean age 83.3), 29 registered nurses (mean age 45.2); Nurses performed oral care daily | Interprofessional oral care program | Reduced tongue microbes; improved awareness, protocol adherence | No control group; single-site; prior training | ★★★★☆ (well-structured intervention with measured outcomes; lacks RCT design) |

| Boada- Cahueñas. [37] | Community-based intervention study | Geriatric center (Red Cross of Otavalo) | Ecuador | 35 older adults (age not specified), 15 caregivers (type not specified) | Educational intervention with virtual platforms on gerontological nutrition and oral health; diet plans based on oral health status; comparator: baseline | 85.3% of older adults had poor oral health; post-intervention, caregivers improved oral hygiene practices by 93%; diets adapted to oral health status (mostly semi-liquid) | Small sample size; limited demographic details; no control group; short follow-up | ★★★☆☆ (moderate risk of bias due to small sample size, lack of control group, and limited follow-up). |

| Wagner et al. [38] | Mixed methods qualitative study with field interviews and literature review | Nursing homes | Germany, Austria, Portugal (collaborative study) | Nursing home caregiving staff (number not specified); elderly residents indirectly involved | Deployment of sensor-based oral-care adherence aid system and electric toothbrushes integrated into daily workflow | Caregivers welcomed the system; helped identify residents unable to perform adequate oral self-care; potential to improve oral care and reduce morbidity and hospitalizations; economic benefits with return on investment estimated at 1:2.5 | Small sample size; initial reactions only (short-term); lack of quantitative outcome data on oral health improvements; limited generalizability | ★★★☆☆ (moderate quality; qualitative design with limited sample and short follow-up; useful for understanding caregiver perspectives but limited empirical outcome data) |

| Edman and Wardh [39] | Cross-sectional survey | Home care and special accommodations (nursing homes), | Sweden | 2167 care personnel; mean age 44.2 years; mostly assistant nurses and women; mix of experience levels | Nursing Dental Coping Beliefs Scale (N-DCBS) used to assess beliefs across 4 domains: Self-Efficacy, Internal/External Locus of Control, Oral Health Care Beliefs | Internal control higher in experienced staff; confidence high but practice inconsistent | High dropout; low consistency; regional limits | ★★★☆ (broad sample, validated scale; but limited generalizability and measurement consistency) |

| Sigurdardottir et al. [40] | Cross-sectional survey | 2 nursing homes | Iceland | 109 caregivers (94% female, avg. age 38.5); care assistants, practical nurses, and registered nurses | No intervention; survey using Nursing Dental Coping Belief Scale (NDCBS), and questions on beliefs, education, and practices | Low training levels; care assistants’ main providers; low floss use; beliefs varied | Two homes; small sample; Iceland-only survey. | ★★★☆☆ Moderate quality: findings are based on a small sample from only two nursing homes in Iceland. Self-report survey design may introduce response bias. |

| Alalshaikh et al. [41] | Cross-sectional survey study | Special needs centers, schools, and organizations | Saudi Arabia | 186 caregivers; mostly female | No intervention; perceptions of oral & general health | High awareness; younger caregivers’ better awareness; support for dentist role | Self-report bias; convenience sample; limited region | ★★★☆☆ (moderate; informative but limited generalizability) |

| An et al. [42] | Cross-sectional study | Tertiary hospital in Chenzhou, Hunan Province | China | 317 nurses; Mean age: 32.25 years; 95.9% female; Mostly with ≥5 years of clinical experience and bachelor’s degrees | HeLD-14 & behavior questionnaire | Higher OHL linked to better behaviors; poor flossing & dental visits | Self-report bias; single site; interested participants may bias sample | ★★★☆ (well-executed but limited in generalizability and causality) |

| Shirobe et al. [43] | Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial | Dental Clinics | Japan | 83 older adults (51 intervention, 32 control); mean age 78 years; caregiver type not specified | 12-week oral frailty program vs. none | Improved motor skills, tongue pressure, and masticatory function in intervention group | High dropout rate; small sample size; short-term follow-up only | ★★★☆ Moderate quality due to sample size and follow-up limitations |

| Balwanth and Singh [44] | Cross-sectional study | 7 Long-term care facilities in eThekwini District | South Africa | 188 formal caregivers; Majority female (96.8%); Mostly aged 30–42; 83.5% cared for elderly, rest for children or disabled adults | Self-reported KAP survey | High desire to improve knowledge; uncooperative residents as barrier; knowledge-attitude link | Self-report bias; COVID-19 restrictions | ★★★☆ (methodologically sound but limited generalizability) |

| Cao et al. [45] | Cross-sectional survey | Community settings (urban & rural) | China | 4218 community-dwelling older adults (aged ≥60); no caregivers included | No intervention; assessed oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices in relation to frailty using structured questionnaire | Knowledge linked to frailty; urban/rural differences; attitudes protective | Self-report bias; no caregiver data; limited generalizability | ★★★☆☆ Moderate (typical for small cross-sectional studies; informative but not generalizable) |

| Chau et al. [46] | Systematic review | Community & clinical settings (5 studies) | South Korea, Egypt, Australia, UK | 422 total participants aged ≥60; no caregivers included | 5 studies using mHealth (apps, web modules, SMS) to deliver oral health education vs. control groups or baselines | mHealth improved knowledge, behaviors; mixed clinical outcomes effectiveness across domains | High dropout; limited follow-up; adherence data lacking | ★★★☆☆/Fair to moderate quality; systematic review with limited included studies. Dropout rates, lack of follow-up data, and poor reporting on intervention adherence affect reliability. |

| Smith et al. [47] | Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | Nursing home | Spain | 45; ≥75 yo, dementia; Formal caregivers | Training + electric toothbrushes (app) vs. usual care | 40% plaque reduction | Small sample size | ★★★☆Moderate quality RCT., limited by very small sample size, lack of long-term follow-up, and unclear generalizability. |

| Idris et al. [48] | Qualitative (Constructivist Grounded Theory) | In-home aged care services | Australia (Perth, WA) | 15; all aged ≥65 clients; 13 support workers, 2 case managers | No intervention; barriers/enablers to care | Barriers: priority, responsibility, affordability, system; Enablers: autonomy, integration, training | Small sample; limited generalizability; interview setting may bias | ★★★☆☆Moderate quality based on qualitative reporting standards. Study provides valuable insights using grounded theory, but the small sample size, limited geographic setting bias limit generalizability. |

| Pahlevanynejad et al. [49] | Systematic review | Home care settings for elderly individuals | Various (studies included from multiple countries; review of international literature) | Elderly adults receiving home care; caregivers include informal (family) and formal caregivers; exact sample sizes vary across included studies | Personalized mobile health (mHealth) interventions including mobile apps, wearable devices, telemonitoring, and digital education tools designed to support elderly home care. Comparators varied or were absent depending on included studies. |

|

| ★★★☆☆ (moderate quality; systematic review with some variability in included studies’ quality and methodology) |

| Bashirian et al. [50] | Systematic review of 23 interventional studies (17 RCTs, 6 quasi-experimental) | Various community, clinical, and institutional settings | Multiple countries (studies included from various countries) | Older adults >60 years; caregivers included in some studies; total sample sizes vary by included studies | Educational interventions targeting older adults and/or their caregivers; methods included lectures, group discussions, motivational interviewing, e-learning, booklets; comparators were usual care or no intervention. | Educational interventions significantly improved oral health knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and oral health-related quality of life in older people; practical education was more common in caregiver-focused interventions; evidence supports effectiveness of education for both older adults and caregivers | Heterogeneity in intervention types and settings; variability in outcome measures; some studies of moderate quality; limited number of high-quality trials; lack of long-term follow-up in many studies. | ★★★☆☆ (moderate quality with a moderate risk of bias, mainly due to heterogeneity in study designs and limitations in reporting and follow-up). |

| Belmonte et al. [51] | Qualitative study (content analysis) | Home care, post-hospital discharge | Brazil | Caregivers of older adults with oropharyngeal dysphagia recently discharged from hospital; number not specified; informal caregivers | Semi-structured interviews analyzed with IRaMuTeQ software; no technology intervention; descriptive of caregiver strategies | Identified three main strategy categories: safe food offering, oral hygiene care, and continuity of speech therapy follow-up; caregivers rely on tacit knowledge and effective transitional care | Sample size and participant details not fully specified; qualitative design limits generalizability; no quantitative outcomes | ★★★☆☆Moderate risk of bias typical of qualitative studies; potential for subjective interpretation; limited transferability |

| ★★★★☆ Comprehensive systematic review with clear methodology; some included studies have variable quality; overall moderate risk of bias due to observational nature of most data. | ||||||||

| Razzaq et al. [52] | Intervention study using data from the LENTO (Lifestyle, Nutrition, and Oral Health in Caregivers) intervention; mixed methods with pre/post assessment of oral health care service use among family caregivers and care recipients | Community and home settings in Eastern Finland; involving family caregivers and their older care recipients | Finland | Informal family caregivers (n = 125) and care recipients (n = 120), all aged 65 years or older, living in Eastern Finland. Caregivers are mostly informal/unpaid family members providing care at home. | Individually tailored preventive oral health intervention aimed at improving use of oral health care services by caregivers and care recipients. Intervention included education, counseling, and support tailored to participants’ needs. No explicit comparator group mentioned; pre/post comparison used. |

|

| ★★★☆☆ (moderate quality; non-randomized intervention study with pre/post design, potential self-report bias, no control group) |

| Bøtchiær et al. [53] | Umbrela Review (Systematic Reviews, Meta-analyses, Scoping Review) | Nursing Homes | Multiple | up to 133,857; ≥65; nurses, staff, dentists | Professional care, mouthwash, education, nutrition | Professional care may reduce pneumonia; malnutrition & QoL linked to oral health; education effect unclear | High heterogeneity; few high-quality studies | ★★☆☆☆ Low quality due to 14 of 17 included reviews not reporting risk of bias. GRADE: Mostly Very Low—some High (nutrition/OHRQoL). |

| Wong and Leung [54] | Quasi-experimental longitudinal study | Two long-term care institutions | Hong Kong SAR | 40 total (20 intervention, 20 control); healthcare providers, majority female, avg. age ~38 | Oral Health Educational Program (4 sessions: 2 theory, 2 skill demos) vs. usual care | Knowledge sustained; practice/attitude change non-significant | Small sample; 2 facilities; limited generalizability | ★★★★☆/Low risk of bias; study used a clear quasi-experimental design with an intervention and control group, but quality is limited by small sample size, selection from only two facilities, and lack of randomization. |

| James et al. [55] | Mixed Method Study (Quantitative + Qualitative) | Old Age Homes | India | 54 elderly, 54 caregivers; ≥60 yo; full-time caregivers | No intervention; caregiver perceptions and oral health status | Poor oral health; high DMFT; barriers: autonomy, finances, knowledge, time | Small sample; convenience sample; localized to Bengaluru | ★★★☆☆Moderate (qualitative stronger; higher bias quantitative) |

| Dumbuya et al. [56] | Qualitative Study (Semi-structured Interviews) | Nursing Homes (10 sites, affiliated with UT Health San Antonio) | United States | 19; caregivers & administrators; 20–69 yo | No intervention; in-person interviews | Caregivers confident but time-limited; administrators unsure; need more training | Small sample; convenience sampling; COVID-19 impact | ★★★☆☆ (rigorous qualitative design, but lacks generalizability due to sampling) |

| Nitschke et al. [57] | Cross-sectional study | Multiple care settings | Germany | 79 caregivers; mean age 37.5 (range 16–63); mostly nursing assistants and semi-skilled labor nurses | Assessment of caregiver knowledge, attitudes, and hopes regarding implementation of the German Expert Nursing Standard “Promotion of Oral Health in Nursing” (GENS-POHN); Pre-implementation evaluation | Positive attitudes; knowledge gaps identified | Small sample; limited region; residents not included | ★★★☆☆ (moderate; observational design, but detailed pre-implementation evaluation) |

| Weening-Verbree et al. [58] | Cross-sectional explorative study | Home care nursing organizations | Netherlands | 141 older adults; mean age 84 (SD 7.4); caregivers: home care nurses (HCNs) of varying training levels | Simplified Oral Indicator (SOI) by HCNs vs. OHAT-NL by dental hygienists and GOHAI-NL self-assessment | SOI sensitivity/specificity poor; weak correlation to other scales | Small sample; denture wearers overrepresented | ★★★☆☆ (moderate quality; exploratory pilot study) |

| Salazar et al. [59] | Systematic review of 30 randomized clinical trials | Community and long-term care facilities | Multiple countries (not specified) | Dependent older adults (varied sample sizes across studies), including community-dwelling and institutionalized; caregiver types varied | Educational and non-educational oral health interventions; comparators included usual care or no intervention | Interventions may reduce dental plaque short-term (low certainty)

| Heterogeneity of included studies

| ★★★☆☆ Moderate quality; risk of bias assessed with Cochrane tool; limitations due to study quality and imprecision |

Note: The table illustrates the quality assessment for included studies and highlights specific methodological concerns such as small sample size, absence of blinding, or short follow-up period.

5. Discussion

The evidence gathered in this systematic review underscores the critical role of ongoing education for both formal and informal caregivers in enhancing oral hygiene among older adults. In particular, the study by Girestam Croonquist et al. [30] demonstrated that these educational interventions lead to significant reductions in dental plaque and gingival bleeding, alongside substantial increases in caregiver knowledge and self-efficacy. Hernández-Santos and Díaz-García [29] found comparable results; their research showed that weekly educational sessions led to oral hygiene scores improving by 33.72%.

In this context, several studies provide concrete examples of effective individualized strategies. For instance, Girestam Croonquist et al. [30] reported that monthly professional cleaning combined with targeted caregiver education significantly improved mucosal-plaque scores, gingival bleeding, and root caries incidence among nursing home residents. Similarly, Wu et al. [33] demonstrated that personalized caregiver coaching sessions, supported by electric toothbrushes, led to greater reductions in plaque and gingivitis among older adults with cognitive impairment compared to basic educational materials alone. These examples highlight that individualized, context-sensitive interventions can translate into measurable improvements in oral health outcomes for older adults.

Currently, smart devices and teledentistry, along with other emerging technologies, are reshaping geriatric dental care by providing greater access to monitoring and attending to one’s oral health care. [27,38,47]. Despite the progress we’ve made, there are still significant challenges to overcome. These include limited access to broadband, a high turnover rate in the workforce, and a lack of widely accepted organizational procedures, all of which can weaken the long-term effectiveness of these ongoing changes [28,31,49].

From an economic perspective, these educational and technological interventions validate a favorable return on investment. Wagner et al. [38] estimate that for every monetary unit invested in technological systems and caregiver training, up to 1:2.5 units can be saved by preventing morbidity and avoidable hospitalizations. These findings reinforce the concept that prevention and caregiver education in oral hygiene are cost-effective investments that reduce both direct and indirect costs for individuals and public health systems [48,59].

Even though there are some enormous advantages, significant challenges persist related to inequities in funding, limited insurance coverage for dental care in older adults, and insufficient prioritization of oral health in public policies, which hinder equitable implementation and access to these interventions [28,48]. Many of the studies on this topic do not include a thorough cost-effectiveness analyses or long-term follow-up data which makes it hard to measure potential economic savings accurately [59].

Additionally, older adults living institutions often face cognitive and physical challenges, and different levels of digital skills among caregivers create obstacles. This means that it is needed to create specific interventions that fit the unique cultural and personal requirements of each situation [44,48]. From a research perspective, most of the studies have limitations such as small sample sizes, short follow-up times, and a lack of control groups. These issues make it difficult to apply the findings more broadly and highlight the need for more detailed studies that involve multiple centers and take place over a longer period [28,59].

Moreover, improving oral hygiene for older adults relies heavily on strong support from institutions. This includes ongoing training programs, regular supervisions and clear guidelines to help ensure that best practice are followed and monitored [37,46,54]. To achieve both clinical and economic benefits while promoting fair oral health for this vulnerable group we must enhance interdisciplinary caregiver training to make technology more accessible and strengthen institutional resources.

The findings of this review underscore the necessity of developing a specific curriculum for healthcare professionals and auxiliary staff who care for older adults. Training modules should address not only clinical oral hygiene techniques, but also behavioral management for patients with cognitive impairment, use of assistive technologies, and interdisciplinary collaboration in geriatric care. A standardized curriculum integrated into medical, nursing, and caregiver education would strengthen professional preparedness, reduce variability in practice, and align with the WHO Decade of Healthy Aging goals.

Technological tools such as teledentistry, mobile health applications, and sensor-based adherence systems hold considerable promise in bridging gaps in oral health care for older adults, particularly by enhancing monitoring, communication, and accessibility [60,61]. However, their broader implementation faces multiple challenges. Previous studies (e.g., [18,62]) have documented barriers such as high operational costs, insufficient institutional encouragement, concerns about patient privacy and data security, poor internet connectivity, and language or communication challenges. Additional obstacles include a lack of the necessary digital skills among older adults and caregivers, limited teledentistry infrastructure in low-resource settings, and resistance among some dental professionals to integrate these technologies into routine practice [18]. Beyond technological hurdles, socioeconomic inequalities strongly influence both caregiver education and access to dental care: lower-income families may struggle with affordability, while caregivers with limited education may face difficulties engaging with digital platforms or understanding preventive guidelines. These findings suggest that for technological interventions to be widely and equitably adopted, policies must address affordability through subsidies or insurance coverage, improve digital infrastructure, and provide culturally tailored training programs to enhance digital literacy among caregivers and older adults.

While heterogeneity in health conditions among older adults makes a single universal protocol challenging, there is a strong case for establishing a standardized preventive framework for people aged 65 and older. This framework should recommend more frequent preventive dental visits (every 3–6 months), individualized oral hygiene plans, and integration of assistive technologies to address functional limitations. Standardized recommendations can serve as a baseline, while remaining adaptable to comorbidities, care-dependency levels, and cultural contexts, ensuring that older adults receive both consistent and personalized care.

A critical examination of methodological quality reveals that while randomized controlled trials provided stronger evidence for caregiver training and oral hygiene interventions, the majority of observational studies were constrained by small sample sizes, short follow-up durations, and reliance on self-report data. These limitations weaken causal inferences and reduce the generalizability of findings across different populations and care settings. Nevertheless, such studies remain valuable in highlighting contextual barriers, caregiver perceptions, and cultural considerations that may not be fully captured in experimental designs. Recognizing these trade-offs is essential for interpreting the strength and scope of the evidence base.

Moreover, at the study and outcome level, the included studies varied in design, sample size, and methodological rigor, which may introduce heterogeneity in the results. As highlighted in our risk of bias assessment, some studies carried moderate or high risk of bias, and their findings should be interpreted with caution. At the review level, despite a comprehensive search strategy, the possibility of incomplete retrieval of relevant studies cannot be excluded, particularly unpublished or non-English research. Furthermore, reporting bias may have influenced the available evidence, as studies with positive findings are more likely to be published. These limitations underscore the need for cautious interpretation of our synthesis and highlight the importance of conducting further high-quality, well-reported research in this area.

6. Conclusions

The oral health of the elderly is a challenge to take care of, influenced by several health problems and the lack of sufficient support. Dentists or healthcare workers should give individualized care to promote oral health care education, while also exploring technology use. Barriers to effective oral hygiene care includes limited access to dental care, various comorbidities, and costs associated with care.

Caregiver training is crucial for the oral hygiene of older adults. Future research should include study designs and outcome measures that are relevant to actual clinical practice, culturally appropriate, and make a lasting contribution to the field. Demonstrating the leadership required from the dental professional in promoting education and protocols alongside advocating for policies will empower future older adults to decrease health disparities and promote health and active aging.

Looking ahead, future research should build on the findings of this review by addressing the methodological and contextual gaps identified. Well-designed multicenter randomized controlled trials with larger and more diverse populations are needed to provide stronger evidence on the effectiveness of caregiver education and individualized oral hygiene strategies. Studies should also incorporate longer follow-up periods to evaluate the sustainability of interventions over time, as well as cost-effectiveness analyses to assess their economic feasibility. Furthermore, research should explore the integration of technological tools—such as teledentistry, mobile health applications, and sensor-based adherence systems—while paying close attention to barriers related to digital literacy, infrastructure, and socioeconomic inequalities. Cross-cultural and interdisciplinary investigations could offer valuable insights into how caregiver education and oral hygiene interventions can be adapted to diverse care settings and health systems, ultimately advancing equitable and sustainable oral health for older adults.

Despite advances in this field, several gaps in knowledge remain. There is a lack of longitudinal studies that can evaluate the sustainability of caregiver education and oral hygiene interventions over time. Cost-effectiveness analyses are scarce, limiting the ability of policymakers to prioritize investments in preventive oral health for older adults. Additionally, most studies focus on high-income countries, leaving low-resource and culturally diverse contexts underrepresented. The evaluation of standardized caregiver curricula across different healthcare professions is also limited, despite evidence of significant knowledge gaps. Finally, research is needed on how to implement and scale up teledentistry and digital tools in ways that address barriers such as affordability, digital literacy, and professional acceptance. Addressing these gaps will be essential to advancing equitable, evidence-based oral health care for older adults in the coming years.

The PRISMA 2020 checklist for systematic reviews has been completed and is provided as Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/hygiene5040050/s1, Table S1: PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.A. and A.N.; methodology, D.M.A., K.M., and A.N.; validation, D.M.A. and A.N.; formal analysis, D.M.A., A.N., and S.B.; investigation, D.M.A., A.N., and S.B.; data curation, D.M.A., A.N., and S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.A.; writing—review and editing, D.M.A., A.N., S.B., M.A.E., and K.M.; visualization, D.M.A., A.N., and S.B.; supervision, A.N., K.M., and M.A.E.; project administration, D.M.A., A.N., and M.A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Khan, H.T.A.; Addo, K.M.; Findlay, H. Public health challenges and responses to the growing ageing populations. Public Health Chall. 2024, 3, e213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso García, M.; Pérez Manso, B.; Licea Alfonso, D.M. Dilemas y desafíos de una población en proceso de envejecimiento. Rev. Cuba. Med. Gen. Integr. 2021, 37, e1559. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Decade of Healthy Ageing; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/decade-of-healthy-ageing (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Slack-Smith, L.; Arena, G.; See, L. Rapid oral health deterioration in older people: A narrative review from a socioeconomic perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, J.P.; Nair, R.U. Oral health factors related to rapid oral health deterioration among older adults: A narrative review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, C.; Konig, H.H.; Hajek, A. Oral health and quality of life: Findings from Survey of Health Ageing and Retirement in Europe. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badewy, R.; Singh, H.; Quiñonez, C.; Singhal, S. Impact of Poor Oral Health on Community-Dwelling Seniors: A Scoping Review. Health Serv. Insight 2021, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, T.L.; Moss, K.L.; Jones, J.A.; Preisser, J.S.; Weintraub, J.A. Loneliness and low life satisfaction associated with older adults’ poor oral health. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1428699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papi, S.; Hosseini, S.V.; Bahadori, F.; Rezapour, V.; Moghadasi, A.M.; FadayeVatan, R. Oral Problems and Psychological Status of Older Adults Referred to Hospital and its Relationship with Cognition Status, Stress, Anxiety, and Depression. Iran. J. Health Sci. 2022, 10, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.S.; Veitz-Keenan, A.; McGowan, R.; Niederman, R. What is the societal economic cost of poor oral health among older adults in United States? A scoping review. Gerodontology 2021, 38, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Gallagher, J.E. Healthy ageing and oral health: Priority, policy and public health. BDJ Open 2024, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OMS. Resumen: Informe Mundial Sobre El Envejecimiento y la Salud; Organización Mundial de la Salud: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://www.who.int/es/publications/i/item/9789241565042 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Sánchez Benítez, M.; Hernández Fernández, L.; Rodríguez Corría, R.; Tejeda Castañeda, E. Protección al adulto mayor: Necesario enfoque multidimensional por profesionales de la salud en Cuba. EDUMECENTRO 2022, 14, e1848. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenhart, A.L.; Nagy, H. Assisting Patients with Personal Hygiene. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Asanza, D.; Guanche Martínez, A.S.; Reyes Puig, A.C. La odontogeriatría en la formación y superación de especialistas en Cuba. Rev. Cub. Med. Mil. 2020, 49, e0200502. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Asanza, D.; Rojas Herrera, I.A.; Njoku, A.; Reyes Puig, A.C.; Mouloudj, F.; Gómez Capote, I.; Maupome, G. Study Plans and Programs Supporting Geriatric Dentistry Teaching in Cuba: An Update. In Geriatric Dentistry in the Age of Digital Technology; Martínez Asanza, D., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, M.S.; Singh, T.; Zakeri, G.; Hung, M. Oral Health and Older Adults: A Narrative Review. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouarar, A.C.; Asanza, D.M.; Mouloudj, S.; Bouarar, A.; Mouloudj, K.; Bozorgi, M. Elderly’s Intention to Use Teledentistry Services: Antecedents and Challenges. In Geriatric Dentistry in the Age of Digital Technology; Martínez Asanza, D., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Caregiver. NCI Cancer Dictionary. 2011. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/caregiver (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P. A Conceptual Framework for Critical Appraisal in Systematic Mixed Studies Reviews. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2019, 13, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.5; Cochrane: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lunny, C.; Kanji, S.; Thabet, P.; Haidich, A.B.; Bougioukas, K.I.; Pieper, D. Assessing the methodological quality and risk of bias of systematic reviews: Primer for authors of overviews of systematic reviews. BMJ Med. 2024, 3, e000604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilanti, L.; Santarelli, A.; Mascitti, M.; Procaccini, M.; Rapelli, G. Dental care access and the elderly: What is the role of Teledentistry? A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.C.; Stott, D.J.; Weir, C.J.; Chalmers, C.; Sweeney, P.; Barr, J.; Pollock, A.; Bowers, N.; Gray, H.; Bain, B.J.; et al. A pragmatic, multi-centered, stepped wedge, cluster randomized controlled trial pilot of the clinical and cost effectiveness of a complex Stroke Oral healthCare intervention plan Evaluation II (SOCLE II) compared with usual oral healthcare in stroke wards. Int. J. Stroke. 2020, 15, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hernández-Santos, D.M.; Díaz-García, I.F. Intervención educativa en cuidadores y su impacto en la higiene bucal de adultos mayores institucionalizados. Rev. Estomatol. 2020, 28, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girestam Croonquist, C.; Dalum, J.; Skott, P.; Sjögren, P.; Wårdh, I.; Morén, E. Effects of Domiciliary Professional Oral Care for Care-Dependent Elderly in Nursing Homes—Oral Hygiene, Gingival Bleeding, Root Caries and Nursing Staff’s Oral Health Knowledge and Attitudes. Clin. Interv. Aging 2020, 15, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zimmerman, S.; Sloane, P.D.; Ward, K.; Wretman, C.J.; Stearns, S.C.; Poole, P.; Preisser, J.S. Effectiveness of a Mouth Care Program Provided by Nursing Home Staff vs Standard Care on Reducing Pneumonia Incidence: A Cluster Randomized Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e204321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Méndez, F.; Huerta-Fernández, J. Protocolo de Higiene Oral para Establecimientos de Larga Estadía para Adultos Mayores en Estado de Pandemia COVID-19. Prevención de Neumonía por Aspiración. Int. J. Odontostomat. 2020, 14, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Anderson, R.A.; Pei, Y.; Xu, H.; Nye, K.; Poole, P.; Bunn, M.; Downey, C.L.; Plassman, B.L. Care partner-assisted intervention to improve oral health for older adults with cognitive impairment: A feasibility study. Gerodontology 2021, 38, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, T.F.S.d.; Embaló, B.; Pereira, M.C.; Borges, S.C.; Mello, A.L.S.F.d. Oral health of homebound older adults followed by primary care: A cross sectional study. Rev. Bras. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2021, 24, e220038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, J.; Rosales, E.; Garrido-Urrutia, C. Oral health care beliefs among caregivers of the institutionalized elderly in Antofagasta, Chile, 2019. Odontoestomatología 2021, 23, e214. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, M.; Ueda, T.; Sakurai, K. An Interprofessional Approach to Oral Hygiene for Elderly Inpatients and the Perception of Caregivers Towards Oral Health Care. Int. Dent. J. 2021, 71, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boada Cahueñas, A. Dietas nutricionales basadas en el estado bucal de adultos mayores mediante TICs: Nutritional diets based on the oral status of older adults using ICTs. Caminos Investig. 2022, 3, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.; Rosian-Schikuta, I.; Cabral, J. Oral-care adherence. Service design for nursing homes—initial caregiver reactions and socio-economic analysis. Ger. Med. Sci. GMS E-J. 2022, 20, Doc04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edman, K.; Wårdh, I. Oral health care beliefs among care personnel working with older people—follow-up of oral care education provided by dental hygienists. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2022, 20, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigurdardottir, A.S.; Geirsdottir, O.G.; Ramel, A.; Arnadottir, I.B. Cross-sectional study of oral health care service, oral health beliefs and oral health care education of caregivers in nursing homes. Geriatr. Nurs. 2022, 43, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alalshaikh, M.; Alsheikh, R.; Alfaraj, A.; Al-Khalifa, K.S. Caregivers’ Perception about the Relationship between Oral Health and Overall Health in Individuals with Disability in Qatif, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Dent. 2022, 2022, 8586882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- An, R.; Chen, W.F.; Li, S.; Wu, Z.; Liu, M.; Sohaib, M. Assessment of the oral health literacy and oral health behaviors among nurses in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shirobe, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Hirano, H.; Kikutani, T.; Nakajo, K.; Sato, T.; Furuya, J.; Minakuchi, S.; Iijima, K. Effect of an Oral Frailty Measures Program on Community-Dwelling Elderly People: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Gerontology 2022, 68, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Balwanth, S.; Singh, S. Caregivers’ knowledge, attitudes, and oral health practices at long-term care facilities in KwaZulu-Natal. Health SA. 2023, 28, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cao, C.; Liao, S.; Cao, W.; Guo, Y.; Hong, Z.; Ren, B.; Hu, Z.; Bai, Z. Differences in the association of oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices with frailty among community-dwelling older people in China. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chau, R.C.W.; Thu, K.M.; Chaurasia, A.; Hsung, R.T.C.; Lam, W.Y.-H. A Systematic Review of the Use of mHealth in Oral Health Education among Older Adults. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, M.J.; Nijholt, W.; Bakker, M.H.; Visser, A. The predictive value of masticatory function for adverse health outcomes in older adults: A systematic review. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2024, 28, 100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, S.; Aghanwa, S.; O’Halloran, J.; Durey, A.; Slack-Smith, L. Homebound oral care for older adults: A qualitative study of professional carers’ perspectives in Perth, Western Australia. Gerodontology 2024, 41, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahlevanynejad, S.; Niakan Kalhori, S.R.; Katigari, M.R.; Eshpala, R.H. Personalized Mobile Health for Elderly Home Care: A Systematic Review of Benefits and Challenges. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2023, 2023, 5390712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashirian, S.; Khoshravesh, S.; Ayubi, E.; Karimi-Shahanjarini, A.; Shirahmadi, S.; Solaymani, P.F. The impact of health education interventions on oral health promotion among older people: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmonte, M.S.; Pedreira, L.C.; Gomes, N.P.; Oliveira, D.V.; Souza, A.C.F.S.E.; Pinto, I.S. Home caregiver strategies for feeding older adults with dysphagia after dehospitalization. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2024, 58, e20230318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razzaq, S.; Nykänen, I.; Välimäki, T.; Koponen, S.; Savela, R.M.; Schwab, U.; Suominen, A.L. Use of oral health care services by family caregivers and care recipients: The LENTO intervention. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2024, 83, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bøtchiær, M.V.; Bugge, E.M.; Larsen, P. Oral health care interventions for older adults living in nursing homes: An umbrella review. Aging Health Res. 2024, 4, 100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, F.M.F.; Leung, W.K. Sustainability of an Educational Program on Oral Care/Hygiene Provision by Healthcare Providers to Older Residents in Long-Term Care Institutions: A Follow-Up Study. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- James, A.; Km, S.; Krishnappa, P. Perception of Caregivers about Oral Health Services for Institutionalized Older Adults: A Mixed Method Study. Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2024, 28, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dumbuya, J.; Marwaha, R.S.; Shah, P.K.; Challa, S. To assess the knowledge, attitudes, and confidence of caregivers and administrators towards the oral health of nursing home residents in San Antonio, Texas. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nitschke, I.; Schulz, F.; Ludwig, E.; Jockusch, J. Implementation of the Expert Nursing Standard: Caregivers’ Oral Health Knowledge. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weening-Verbree, L.F.; Schuller, A.A.; Krijnen, W.P.; Van der Schans, C.P.; Zuidema, S.U.; Hobbelen, J.S.M. Validation of a simplified oral indicator for home care nurses to refer older people to dental care professionals. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2024, 83, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, J.; Andersen, C.; Øzhayat, E.B. Effect of oral health interventions for dependent older people-A systematic review. Gerodontology 2024, 41, 200–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascadopoli, M.; Zampetti, P.; Nardi, M.G.; Pellegrini, M.; Scribante, A. Smartphone Applications in Dentistry: A Scoping Review. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Cheng, L.; Wang, H. Challenges and Opportunities for Dental Education from COVID-19. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouloudj, K.; Bouarar, A.C.; Asanza, D.M.; Saadaoui, L.; Mouloudj, S.; Njoku, A.U.; Evans, M.A.; Bouarar, A. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Digital Health Apps: An Extended Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). In Integrating Digital Health Strategies for Effective Administration; Bouarar, A., Mouloudj, K., Martínez Asanza, D., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).