Abstract

This paper presents a mathematical formalism for generative artificial intelligence (GAI). Our starting point is an observation that a “histories” approach to physical systems agrees with the compositional nature of deep neural networks. Mathematically, we define a GAI system as a family of sequential joint probabilities associated with input texts and temporal sequences of tokens (as physical event histories). From a physical perspective on modern chips, we then construct physical models realizing GAI systems as open quantum systems. Finally, as an illustration, we construct physical models realizing large language models based on a transformer architecture as open quantum systems in the Fock space over the Hilbert space of tokens. Our physical models underlie the transformer architecture for large language models.

1. Introduction

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) models are important for modeling intelligent machines as physically described in [1,2]. Generative AI is based on deep neural networks (DNNs for short), and a common characteristic of DNNs is their compositional nature (cf. [3]): data is processed sequentially, layer by layer, resulting in a discrete-time dynamical system. The introduction of the transformer architecture for generative AI in 2017 marked the most striking advancement in terms of DNNs (cf. [4]). Indeed, the transformer is a model architecture eschewing recurrence and instead relying entirely on an attention mechanism to draw global dependencies between input and output. At each step, the model is auto-regressive, consuming the previously generated symbols as additional input when generating the next. The transformer has achieved great success in natural language processing (cf. [5]).

The transformer has a modularization framework and is constructed by two main building blocks: self-attention and feed-forward neural networks. Self-attention is an attention mechanism relating different positions of a single sequence in order to compute a representation of the sequence. However, despite its meteoric rise within deep learning, we believe there is a gap in our theoretical understanding of what the transformer is and why it works physically (cf. [6]).

We think that there are two origins for the modularization framework of generative AI models. One is a mathematical origin in which a joint probability distribution can be computed by sequentially conditional probabilities. For instance, the probability of generating a text given an input X in a transformer architecture is equal to the joint probability distribution such that

where the conditional probability is given by the ℓ-th attention block in the transformer. Another is a physical origin, in which a physical process is considered to be a sequence of events as a history. As such, generating a text given an input X in a physical machine is a process in which, given an input X at time an event occurs at time an event occurs at time …, and last, an event occurs at time . A theory of the “histories” approach to physical systems was established by Isham [2], and the mathematical theory of it associated with joint probability distributions was then developed by Gudder [1]. Based on their theory, in this paper, we present a mathematical formalism for generative AI and describe the associated physical models.

To the best of our knowledge, physical models for generative AI are usually described by using systems of mean-field interacting particles (cf. [7,8] and references therein); i.e., generative AI models are regarded as classical statistical systems. However, since modern chips process data by controlling the flow of electric current, i.e., the dynamics of many electrons, they should be regarded as quantum statistical ensembles and open quantum systems from a physical perspective (cf. [9,10]). Consequently, based on our mathematical formalism for generative AI, we construct physical models realizing generative AI systems as open quantum systems. As an illustration, we construct physical models realizing large language models based on a transformer architecture as open quantum systems in the Fock space over the Hilbert space of tokens.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we include some notation and definitions on the attention mechanism, the transformer, and the effect algebras. In Section 3, we give the definition of a generative AI system as a family of sequential joint probabilities associated with input texts and temporal sequences of tokens. This is based on the mathematical theory developed by Gudder (cf. [1]) for a historical approach to physical evolution processes. Those joint probabilities characterize the attention mechanisms as well as the mathematical structure of the transformer architecture. In Section 4, we present the construction of physical models realizing generative AI systems as open quantum systems. Our physical models are given by an event-history approach to physical systems; we refer to [2] for the background of physics for this formulation. In Section 5, we construct physical models realizing large language models based on a transformer architecture as open quantum systems in the Fock space over the Hilbert space of tokens. Finally, in Section 6, we give a summary of our innovative points listed item by item and conclude the contributions of the paper.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we present a mathematical description of the attention mechanism and transformer architecture for generative AI and include some notations and basic properties of -effect algebras (cf. [11]). For the sake of convenience, we collect some notations and definitions. Denote by the natural number set and for we use the notation to represent the set For we denote by the d-dimensional Euclid space with the usual inner product For two sets we denote by the set of all maps from X into For a set we denote where is the set of all sequences of n elements in S; i.e., is the set of all finite sequences of elements in

2.1. Deep Neural Networks

A DNN is constructed by connecting multiple neurons. Recall that a (feed-forward) neural network of depth L consists of some number of neurons arranged in layers. Layer is the input layer, where data is presented to the network, while layer is where the output is read out. All layers in between are referred to as the hidden layers, and each hidden layer has an activation that is a map in the same layer. Specifically, let be a sequence of sets where indexes the neurons in layer and let be a sequence of vector spaces. A mapping is called a feed-forward neural network of depth L if there exists a sequence of maps and a sequence of maps , which is called the activation function at the layer such that

for where is called the input and is the output. We call the architecture of the neural network Of course, is determined by its architecture, and there exist different choices of architectures yielding the same

In their most basic form, is a finite set of elements and a feed-forward neural network is a function of the following form: the input is for and

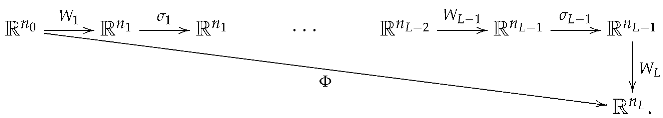

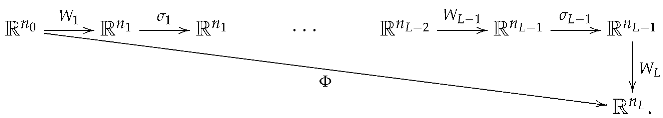

where is the output. This can be illustrated as follows:

Here, the map is usually of the form

where is an matrix called a weight matrix and is called a bias vector for each and the function represents the activation function at the ℓ-th layer. The set of all entries of the weight matrices and bias vectors of a neural network are called the parameters of These parameters are adjustable and learned during the training process, determining the specific function realized by the network. Also, the depth the number of neurons in each layer, and the activation functions of a neural network are called the hyperparameters of They define the network’s architecture (and training process) and are typically set before training begins. For a fixed architecture, every choice of network parameters as in (3) defines a specific function and this function is often referred to as a model.

Here, the map is usually of the form

where is an matrix called a weight matrix and is called a bias vector for each and the function represents the activation function at the ℓ-th layer. The set of all entries of the weight matrices and bias vectors of a neural network are called the parameters of These parameters are adjustable and learned during the training process, determining the specific function realized by the network. Also, the depth the number of neurons in each layer, and the activation functions of a neural network are called the hyperparameters of They define the network’s architecture (and training process) and are typically set before training begins. For a fixed architecture, every choice of network parameters as in (3) defines a specific function and this function is often referred to as a model.

In a feed-forward neural network, the inputs to neurons in the ℓ-th layer are usually exclusively neurons from the -th layer. However, residual neural networks (ResNets for short) allow skip connections; that is, information is allowed to skip layers in the sense that the neurons in layer ℓ may have as their input (and not just ). In their most basic form, and

where is a vector function, ’s are matrices, and ’s are vectors in In contrast to feed-forward neural networks, recurrent neural networks (RNNs for short) allow information to flow backward in the sense that may serve as input for the neurons in layer ℓ and not just We refer to [12] for more details, such as training for a neural network.

2.2. Attention

The fundamental definition of attention was given by Bahdanau et al. in 2014. To describe the mathematical definition of attention, we denote by the query space, the key space, and the value space. We call an element a query, a key, , and so on.

Definition 1

(cf. [13]). Let be a function. Let be a set of keys and a set of values. Given a the attention is defined by

where is a probability distribution over defined by

This means that a value in (6) occurs with probability for

For we define

In particular, when is said to be self-attention at and the mapping defined by

is called the self-attention map.

We remark that

- (1)

- For a finite sequence of real numbers, defineThen,as usual in the literature.

- (2)

- We have but in general.

- (3)

- The function is called a similarity function, usually given bywhere is a real matrix called a query matrix and is a real matrix called a key matrix. For the real number is interpreted as the similarity between the query q and the key

- (4)

- In the representation learning framework of attention, we usually assume the finite set of tokens has been embedded in where d is called the embedding dimension, so we identify each with one of finitely-many vectors x in We assume that the structure (positional information, adjacency information, etc) is encoded in these vectors. In the case of self-attention, we assume

Since the self-attention mechanism can be composed to arbitrary depth, making it a crucial building block of the transformer architecture, we mainly focus on it in what follows. In practice, we need multi-headed attention (cf. [4]), that process independent copies of the data X and combine them with concatenation and matrix multiplication. Let be the input set of tokens embedded in Let us consider -headed attention with the dimension for every head. For every let be (query, key, value) matrices associated with the i-th self-attention, and the similarity function

Let denote the output projection matrix, where is a matrix for every For the multi-headed self-attention (MHSelfAtt for short) is then defined by

that is, an output

occurs with the probability As such,

yields a basic building block of the transformer

as in the case of one-headed attention.

2.3. Transformer

In line with successful models, such as large language models, we focus on the decoder-only setting of the transformer, where the model iteratively predicts the next tokens based on a given sequence of tokens. This procedure is called autoregressive since the prediction of new tokens is only based on previous tokens. Such conditional sequence generation using autoregressive transformers is referred to as the transformer architecture.

Specifically, in the transformer architecture defined by a composition of blocks, each block consists of a self-attention layer a multi-layer perception and a prediction head layer First, the self-attention layer SelfAtt is the only layer that combines different tokens. Let us denote the input text to the layer by embedded in and focus on the n-th output. For each letting

where and are two matrices (i.e., the query and key matrices), we can interpret as similarities between the n-th token (i.e., the query) and the other tokens (i.e., keys); for satisfying the autoregressive structure, we only consider The softmax layer is given by

which can be interpreted as the probability for the n-th query to “attend” to the j-th key. Then, the self-attention layer can be defined as

where is the real matrix such that for any the output occurring with the probability is often referred to as the values of the token Thus, is a random map such that for each

If the attention is a multi-headed attention with heads of the dimension where for are the (query, key, value) matrices and is the (output) matrix of the i-th self-attention, then the multi-headed self-attention layer is defined by

where

i.e., an output occurs with the probability for each In what follows, we only consider the case of one-headed attention, since the multi-headed case is similar.

Second, the multi-layer perception is a feed-forward neural network such that with the probability () for each Finally, the prediction head layer can be represented as a mapping which maps the sequence of to a probability distribution where is the probability of predicting as the next token. Since contains information about the whole input text, we may define

such that the next token with the probability for

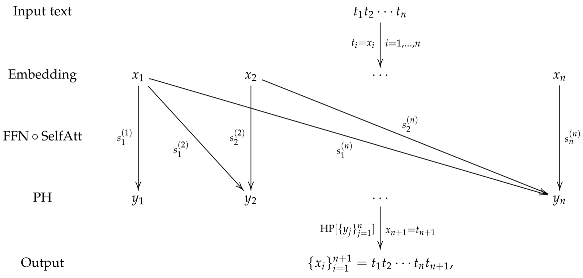

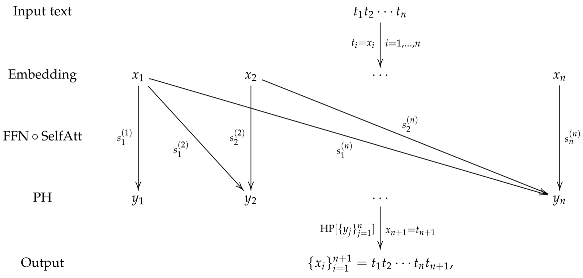

Hence, a basic building block for the transformer, consisting of a self-attention module (SelfAtt) and a feed-forward network (FFN) followed by a prediction head layer (PH), can be illustrated as follows:

where the input text is embedded as a sequence in occurs with the probability for each is generated with the probability for each and so the output is One can then apply the same operations to the extended sequence in the next block, obtaining to iteratively compute further tokens (there is usually a stopping criterion based on a special token or the mapping ). Below, without loss of generality, we omit the prediction head layer

where the input text is embedded as a sequence in occurs with the probability for each is generated with the probability for each and so the output is One can then apply the same operations to the extended sequence in the next block, obtaining to iteratively compute further tokens (there is usually a stopping criterion based on a special token or the mapping ). Below, without loss of generality, we omit the prediction head layer

Typically, a transformer of depth L is defined by a composition of L blocks, denoted by consisting of L self-attention maps and L feed-forward neural networks that is,

where the indices of the layers SelfAtt and FFN in (24) indicate the use of different trainable parameters in each of the blocks. This can be illustrated as follows:

that is,

Also, we can consider the transformer of the form

where denotes the identity mapping in commonly known as a skip or residual connection.

that is,

Also, we can consider the transformer of the form

where denotes the identity mapping in commonly known as a skip or residual connection.

2.4. Effect Algebras

For the sake of convenience, we collect some notations and basic properties of -effect algebras (cf. [1,11,14] and references therein). Recall that an effect algebra is an algebraic system where is a non-empty set, , which are called zeroes and unit elements of this algebra, respectively, and ⊕ is a partial binary operation on that satisfies the following conditions for any :

- (E1)

- (Commutative Law): If is defined, then is defined and which is called the orthogonal sum of a and

- (E2)

- (Associative Law): If and are defined, then and are defined andwhich is denoted by

- (E3)

- (Orthosupplementation Law): there exists a unique such that is defined and such is unique and called the orthosupplement of

- (E4)

- (Zero–One Law): if is defined, then

We simply call an effect algebra in the sequel. From the associative law (E2), we can write if this orthogonal sum is defined. For any we define if there exists a such that this c is unique and denoted by so We also define if is defined; i.e., a is orthogonal to It can be shown (cf. [14]) that is a bounded partially ordered set (poset for short) and if and only if For a sequence in if is defined for all such that exists, then the sum of exists and define We say that is a -effect algebra if exists for any sequence in satisfying that is defined for all It was shown in (Lemma 3.1, [1]) that is a -effect algebra if and only if the least upper bound exists for any monotone sequence i.e.,

Let and be -effect algebras. A map is said to be additive if for implies that and An additive map is -additive if for any sequence such that exists, exists and A -additive map is said to be a -morphism if and moreover, is called a -isomorphism if is a bijective -morphism and is a -morphism. It can be shown (cf. [1]) that

- (1)

- A map is additive if and only if is monotone in the sense that implies

- (2)

- An additive map is -additive if and only if implies

- (3)

- A -morphism satisfies

The unit interval is a -effect algebra defined as follows: For any is defined if and in this case Then, we have that and are the zero and unit elements, respectively. In what follows, we always regard as a -effect algebra in this way. Let be a -effect algebra, a -morphism is called a state on and we denote by the set of all states on A subset S of is said to be order determining if for all implies

Another example of a -effect algebra is a measurable space defined as follows: For any is defined if and in this case, We then have and We always regard a measurable space as a -effect algebra in this way. Let be a -effect algebra, a -morphism is called an observable on with values in (a -valued observable for short). The elements of a -effect algebra are called effects, and so an observable X maps effects in into effects in ; i.e., is an effect in for We denote by the set of all -valued observables. Note that is equal to the set of all probability measures on For and we have which is called the probability distribution of X in the state

3. Mathematical Formalism

In this section, we introduce a mathematical formalism for generative AI. We utilize the theory of -effect algebras to give a mathematical definition for a generative AI system. Let be a -effect algebra and a measurable space. An orthogonal decomposition in is a sequence in such that exists, and moreover, it is complete if We denote by the set of all completely orthogonal decomposition in A completely orthogonal decomposition in is called a countable partition of i.e., a sequence of elements in such that for and We denote by the set of all countable partitions of For an ordered n-tuple of effects in is called a n-time chain-of-effect, and we interpret as an inference process of an intelligence machine in which the effect occurs at time for where Alternatively, no specific times may be involved and we regard as a sequential effect in which occurs first, occurs second, …, and occurs last.

Definition 2.

With the above notations, a generative artificial intelligence system is defined to be a triple where is a σ-effect algebra, is a measurable space, such that

- (G1)

- The input set of is equal to the set ; i.e., an input is interpreted by a state

- (G2)

- The output set of is equal to the set ; i.e., the set of all finite sequences of elements in

- (G3)

- An inference process in is interpreted by a chain-of-effect for

Remark 1.

We refer to [15] for a mathematical definition of general artificial intelligence systems in terms of topos theory, including quantum artificial intelligence systems.

In practice, we are not concerned with a generative AI system itself but deal with models for such as large language models. To this end, we need to introduce the definition of a model for in terms of joint probability distributions for observables associated with

For and we may view the effect as the event for which X has a value in For a partition we may view as a set of possible alternative events that can occur. One interpretation is that represents a building block of an artificial intelligence architecture for processing X and the alternatives result from the dial readings of the block. Given an ordered n-tuple of events is called an n-time chain-of-event, and we interpret as an inference process of an intelligence machine in which has a value in first, has in s, …, and has in last, so that the output result is We denote the set of all n-time chain-of-events by and the set of all chain-of-events by

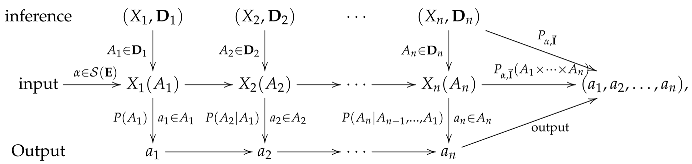

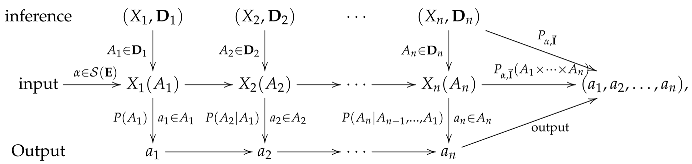

A n-step inference set has the form where We interpret as ordered successive processes of observables with partitions for We denote the collection of all n-step inference sets by and the collection of all inference sets by If and such that for every we say the chain-of-event is an element of the inference set and write This can be illustrated as follows:

which means that the machine firstly obtains as part of an output with the probability then obtains with the conditional probability …, and lastly obtains with the conditional probability and finally combines them to obtain the output result with the probability

where will be explained later.

which means that the machine firstly obtains as part of an output with the probability then obtains with the conditional probability …, and lastly obtains with the conditional probability and finally combines them to obtain the output result with the probability

where will be explained later.

If and are two inference sets, then we define their sequential product by

and obtain a -step inference set. Mathematically, we can include the empty inference set ∅ that satisfies such that becomes a semigroup under this product.

For a partition we denote by the -subalgebra of generated by and for n partitions we denote by the -algebra on generated by i.e.,

We denote by the set of all probability measures on Also, we write for Given an input for an inference set , we denote by the probability measure such that for is the probability within the inference set that the event occurs first, occurs second, …, occurs last. We call the joint probability distribution of an inference set under the input

For interpreting a model for a generative AI system, ’s need to satisfy physically motivated axioms as follows.

Definition 3.

With the above notations, a model for is defined to be a family of joint probability distributions of inference sets

that satisfies the following axioms:

- (P1)

- For and if for all then

- (P2)

- For if and thenfor every

- (P3)

- For with if then

- (P4)

- If and for thenfor every

For the physical meanings of the model structure axioms, we remark that

- (1)

- The axiom means that the input set can distinguish different events;

- (2)

- The axiom means that the partition of the last processing is irrelevant;

- (3)

- The axiom means that the last processing does not affect the previous ones;

- (4)

- The axiom means that the probability of a chain of events does not depend on the partitions and hence is unambiguous. However, for in in general if ’s are quantum observables due to quantum interference.

If and are two inference sets, and if is an input such that then we define the conditional probability of B given A within under the input as follows:

Since is a probability measure on where for and for so is a probability measure on which is called a conditional sequential joint probability distribution.

Proposition 1.

Given and if then the conditional sequential joint probability distribution satisfies the axioms (P2)–(P4) in Definition 3.

Proof.

By the axiom (P2), we have

hence, satisfies the axiom (P2), and so does the axiom (P3). Similarly, the axiom (P4) implies that satisfies the axiom (P4); we omit the details. □

We remark that when observables are quantum ones, Bayes’ formula need not hold, i.e.,

in general. This is because the left-hand side is and the right-hand side is so the order of the occurrences is changed. For instance, consider a qubit with the standard basis and Let If and ; then

and so, We refer to Section 4 for more details.

4. Physical Models for Generative AI

Physical models for generative AI are usually described by using systems of mean-field interacting particles, such as large language models based on attention mechanisms (cf. [7,8] and references therein); i.e., generative AI systems are regarded as classical statistical ensembles. However, since modern chips process data through controlling the flow of electric current, i.e., the dynamics of largely many electrons, they should be regarded as quantum statistical ensembles from a physical perspective (cf. [10]). Consequently, we need to model modern intelligence machines involving open quantum systems. To this end, combining the history theory of quantum systems (cf. [2]) and the theory of effect algebras (cf. [1,14]), we construct physical models realizing generative AI systems as open quantum systems.

Let be a separable complex Hilbert space with the inner product being conjugate-linear at the first variable and linear at the second variable. We denote by the set of all bounded linear operators on by the set of all bounded self-adjoint operators, and by the set of all orthogonal projection operators. We denote by I the identity operator on Unless stated otherwise, an operator means a bounded linear operator in the sequel. An operator T is positive if for all and in this case we write We define for a positive operator where is an orthogonal basis of It is known that is independent of the choice of the basis, and it is called the trace of T if A positive operator is a density operator if and the set of all density operators on is denoted by Each positive operator is self-adjoint, and if two self-adjoint operators such that we write or We refer to [16,17,18] for more details on the theory of operators on Hilbert spaces.

A self-adjoint operator E that satisfies is called an effect, and the set of all effects on is denoted by For we define if and in this case we write It can be shown (cf. (Lemma 5.1, [1])) that is a -effect algebra, and each state on has the form for every where is a unique density operator on and vice versa. Thus, we identify Let be a measurable space. An observable is a positive operator valued (POV for short) measure on ; i.e.,

- (1)

- is an effect on for any

- (2)

- and

- (3)

- For an orthogonal decomposition inwhere the series on the right-hand side is convergent in the strong operator topology on i.e.,for every

To understand the inference process, let us show the conventional interpretation of joint probability distributions in an open quantum system that is subject to measurements by an external observer. To this end, let denote the time-evolution operator from time s to where ’s are usually called Kraus operators, such that

That is, are quantum operations (cf. [19]) such that for every state

in the Schrödinger picture, while for each observable

in the Heisenberg picture. We refer to [9] for the details on the theory of open quantum systems.

Then the density operator state at time evolves in time to the state where

Suppose that a measurement is made at time where and Then the probability that an event with occurs is

If the result of this measurement is kept, then, according to the von Neumann–Lüders reduction postulate, the appropriate density operator to use for any further calculation is

Next, suppose a measurement is performed at time Then, according to the above, the conditional probability of an event for occurs at time given that the event occurs at time (and that the original state was ) is

where and the appropriate density operator to use for any further calculation is

The joint probability of occurring at and occurring at is then

Generalizing to a sequence of measurements at times where and for the sequential joint probability of associated events with occurring at for is

where for and

for

Therefore, given an inference set for an input the sequential joint probability within the inference set that the event occurs at occurs at …, occurs at where for and is given by

where and

for in the Schrödinger picture operator defined with respect to the fiducial time

Proposition 2.

Let be a separable complex Hilbert space, and let be a measurable space. A physical model associated with defined by

where s’ are given by (49), satisfies the axioms in Definition 3.

Proof.

For and by (49) we have

If for all then i.e., the axiom (P1) holds.

Remark 2.

Note that the probability family ’s are determined by the time-evolution operators ’s. Therefore, a family of the discrete-time evolution operators defines a physical model realizing a generative AI system, based on the mathematical formalism in Definition 3 for models of generative AI systems.

5. Large Language Models

In this section, we describe physical models for large language models based on a transformer architecture in the Fock space over the Hilbert space of tokens. Consider a large language model with the set of N tokens. A finite sequence of tokens is called a text for simply denoted by or where n is called the length of the text

Let be the Hilbert space with being an orthogonal basis, and we identify for Let be the Fock space over that is,

where is the n-fold tensor product of We refer to [16] for the details of Fock spaces. In what follows, for the sake of convenience, we involve the finite Fock space

for a large integer Note that an operator for satisfies that for all

and in particular, if for then Given and a sequence for the operator is defined by

for every In particular, if then

where denotes the zero operator in for

Since large language models are based on a transformer architecture, we suffice to construct a physical model in the Fock space () for a transformer (24) with a composition of L blocks, consisting of L self-attention maps and L feed-forward neural networks Precisely, let us denote the input text to the layer by As noted above,

where and

Then, a physical model for consists of an input and a sequence of quantum operations in the Fock space defined above, where We show how to construct this model step by step as follows.

To this end, we denote by and write At first, the input state is given as

Then there is a physical operation in (see Proposition 3 below), depending only on the attention mechanism and such that

where and Define by

and for every

Making a measurement at time we obtain an output with probability , and the appropriate density operator to use for any further calculation is

for every where and

Next, there is a physical operation in (see Proposition 3 again), depending only on the attention mechanism and at time such that

for where (with ) and Define by

and for every

Making a measurement at time we obtain an output with probability , and the appropriate density operator to use for any further calculation is

for each where and

Step by step, we can obtain a physical model with the input state such that a text is generated with the probability

within the inference

Thus, we can obtain a physical model for if we prove that ’s exist.

Proposition 3.

With the above notations, there exists a physical model in () for a transformer (24) such that given an input text a text is generated with the probability

within the inference

Proof.

We regard and as elements in in a natural way, i.e.,

for We need to construct to satisfy (60). We first define

where is a certain token. Secondly, define

and in general, for define

for any and Let

Then extends uniquely to a positive map from into that is,

where are any complex numbers for Since is a commutative -algebra, by Stinespring’s theorem (cf. (Theorem 3.11, [20])), it follows that is completely positive. Hence, by Arveson’s extension theorem (cf. (Theorem 7.5, [20])), extends to a completely positive operator in (note that is not necessarily unique), i.e., a quantum operation in By the construction, satisfies (60). Also, by Kraus’s theorem (cf. [19]), we conclude that has the Kraus decomposition (39).

In the same way, we can prove that exists and satisfies (65). Step by step, we can thus obtain a physical model as required. □

Remark 3.

Physical models satisfying the above joint probability distributions associated with a transformer are not necessarily unique. However, a physical model uniquely determines the joint probability distributions; that is, it defines a unique physical process for operating the large language model based on Therefore, in a physical model for training for corresponds to training for the Kraus operators which are adjustable and learned during the training process, determining the physical model, as corresponding to the parameters and in From a physical perspective, to train for a large language model is just to determine the Kraus operators associated with the corresponding physical system (cf. [22]).

Example 1.

Let be the set of two tokens embedded in such that and Then, with the standard basis and Let

Suppose that in , and let i.e., and Below, we construct a quantum operation associated with and in To this end, define

and

We regard () as elements in in a natural way. Let

Then is a subspace of and Φ extends uniquely to a positive map from into i.e.,

for any As shown in Proposition 3, can extend to a completely positive operator in which is a quantum operation in associated with and in Note that is not necessarily unique.

Example 2.

As in Example 1, is the set of two tokens embedded in such that and Then with the standard basis and Let Assume an input text The input state is then given by

If and in an associated physical operation at time satisfies

By measurement, we obtain with probability and obtain with probability while

If and in an associated quantum operation at time satisfies

and

By measurement at time when occurs at we obtain with probability and obtain with probability when occurs at we obtain with probability and obtain with probability

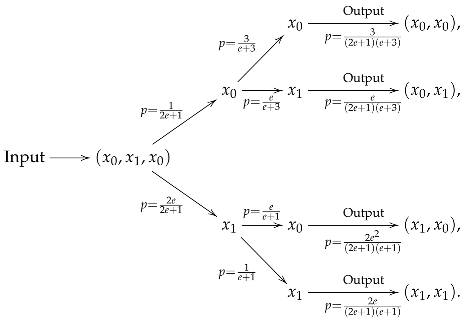

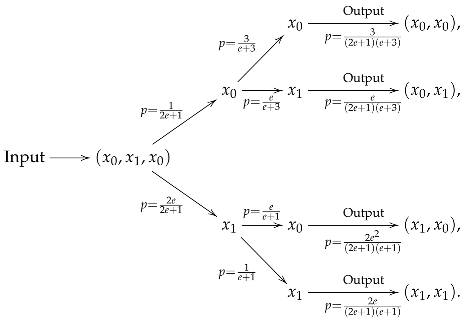

Therefore, we obtain the joint probability distributions:

This can be illustrated as follows:

6. Conclusions

Our primary innovative points are summarized as follows:

- Mathematical formalism for generative AI models. We present a mathematical formalism for generative AI models by using the theory of the history approach to physical systems developed by Isham and Gudder [1,2].

- Physical models realizing generative AI systems. We give a construction of physical models realizing generative AI systems as open quantum systems by using the theories of -effect algebras and open quantum systems.

- Large language models realized as open quantum system. We construct physical models realizing large language models based on the transformer architecture as open quantum systems in the Fock space over the Hilbert space of tokens. The Fock space structure plays a crucial role in this construction.

In conclusion, we present a mathematical formalism for generative AI and describe physical models realizing generative AI systems as open quantum systems. Our formalism shows that a transformer architecture used for generative AI systems is characterized by a family of sequential joint probability distributions. The physical models realizing generative AI systems are described by sequential event histories in open quantum systems. The Kraus operators in the physical models correspond to the query, key, and value matrices in the attention mechanism of a transformer, which are adjustable and learned during the training process. As an illustration, we construct physical models in the Fock space over the Hilbert space of tokens, realizing large language models based on a transformer architecture as open quantum systems. This means that our physical models underlie the transformer architecture for large language models. We refer to [23] for an argument on the physical principle of generic AI and to [15] for a mathematical foundation of general AI, including quantum AI.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the anonymous referees for making helpful comments and suggestions, which have been incorporated into this version of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gudder, S. A histories approach to quantum mechanics. J. Math. Phys. 1998, 39, 5772–5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isham, C.J. Quantum logic and the histories approach to quantum theory. J. Math. Phys. 1994, 35, 2157–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; et al. A survey of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.18223. [Google Scholar]

- Minaee, S.; Mikolov, T.; Nikzad, N.; Chenaghlu, M.; Socher, R.; Amatriain, X.; Gao, J. Large language models: A Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.06196. [Google Scholar]

- Geshkovski, B.; Letrouit, C.; Polyyanskiy, Y.; Rigollet, P. A mathematical perspective on transformers. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 2025, in press.

- Vuckovic, J.; Baratin, A.; Combes, R.T. A mathematical theory of attention. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.02876. [Google Scholar]

- Breuer, H.P.; Petruccione, F. The Theory of Open Quantum Systems; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Villas-Boas, C.J.; Máximo, C.E.; Paulino, P.J.; Bachelard, R.P.; Rempe, G. Bright and dark states of light: The quantum origin of classical interference. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 134, 133603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvurečenskij, A.; Pulmannová, S. New Trends in Quantum Structures; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, P.; Zech, J. Mathematical Theory of Deep Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2407.18384v3. [Google Scholar]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.0473. [Google Scholar]

- Foulis, D.J.; Bennett, M.K. Effect algebras and unsharp quantum logics. Found. Phys. 1994, 24, 1331–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ding, L.; Liu, H.; Yu, J. A topos-theoretic formalism of quantum artificial intellegence. Sci. Sin. Math. 2025, 55, 1–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.; Simon, B. Method of Mordern Mathematical Physics, Vol. I; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.; Simon, B. Method of Mordern Mathematical Physics, Vol. II; Academic Press: Cambridge, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Rudin, W. Functional Analysis, 2nd ed.; The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen, V. Completely Bounded Maps and Operator Algebras; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, H.; Qin, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Gu, Q.; Yao, A.C. Tensor product attention is all you need. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.06425. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, K.; Cerezo, M.; Cincio, L.; Coles, P.J. Trainability of dissipative perceptron-based quantum neural networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 128, 180505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z. Turing’s thinking machine and ’t Hooft’s principle of superposition of states. ChinaXiv 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).