Abstract

(1) Background: Plastic and microplastic pollution in freshwater systems has emerged as a significant environmental and human health concern, yet limited research has explored how affected communities perceive these risks and support related policy interventions. This study addresses this gap by comparing the perceptions of pollution risk and preferred policy responses among stakeholders and the general public associated with the Tennessee River—one of the most plastic-polluted rivers globally. (2) Methods: Using an online survey, we collected data from 419 public respondents and 45 local stakeholders. Participants assessed perceived environmental and human health risks posed by six common pollutants and expressed support for a range of policy solutions. (3) Results: Results indicate that the public consistently perceives higher risks from pollutants than stakeholders, particularly for plastics, E. coli, and heavy metals. Surprisingly, stakeholders demonstrated significantly stronger support for regulatory policy interventions than the public, despite perceiving lower levels of pollution risk. Importantly, perceived harm from microplastics emerged as the most consistent predictor of policy support across all policy types. (4) Conclusions: These findings suggest that risk perceptions, particularly regarding microplastics, play a critical role in shaping policy preferences and highlight the importance of stakeholder engagement in designing effective freshwater pollution mitigation strategies.

Keywords:

plastic; microplastic; pollution; policy; preferences; survey; Tennessee river; stakeholder 1. Introduction

The Tennessee River is one of the most ecologically important and biodiverse waterways in the United States. Its 652-mile-long waters are home to 263 known fish species, and 58 of these species are found only in the Tennessee River [1]. This represents nearly half of all fish species known from the Southeastern USA, an area that is an exceptionally important global aquatic hotspot [2]. Furthermore, the Tennessee River has the most endemic (and therefore most at-risk) and species-rich proportion of fish, mussel, and crayfish species of all the watersheds comprising the Southeastern USA aquatic hotspot [2]. Beyond its ecological importance, the river plays a crucial role in the region’s economy and society, facilitating commercial operations such as barging and offering diverse recreational opportunities that generate billions of revenue dollars. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which monitors and manages much of the activity on the Tennessee River, estimates that recreational activity just on its reservoirs (lakes) alone generates almost $12 billion per year [3].

However, despite its socio-ecological importance, the Tennessee River faces an alarming number of rapidly expanding pollution challenges that are threatening the river’s rich biological resources and ecosystem services. According to the 2024 Monitoring and Assessment Report by the State Department of Environment and Conservation [4] Tennessee waterways (which are substantially comprised by the Tennessee River watershed) are significantly impacted by the following: E. coli (31%), siltation (25%), nutrient-related (17%), metals (3%), and organic chemicals (1%). These all pose serious environmental and public health concerns. As a result, large sections of the river have been classified as impaired by the state’s Department of Environment and Conservation [4].

In addition to these threats, plastic and microplastic pollution are emerging as a critical topic of increasing concern. One widely-cited study, which sampled plastic pollution along the river’s course, found that the Tennessee River experiences some of the highest levels of riverine plastic pollution anywhere in the world [5]. Significant non-point sources of plastic and other kinds of debris have been observed in several of the river’s tributaries, often associated with urbanized areas [6]. Also, municipal and construction activities contribute pollutants to 15% and 3% of Tennessee waterways, respectively, while waste sites account for an additional 2% [4]. Landfills, associated with urban areas, are major sources of plastics from leachates and surface water runoff [7]. Perhaps most importantly, the 2024 Report lists agriculture as the dominant single source of water pollution in Tennessee waterways, including vast stretches of the Tennessee River, accounting for almost half (47%) of all pollutants [4]. Agriculture is a major source of plastic water pollution, mainly via the extensive use of plastic mulch across the landscape [8].

While plastic pollution research has traditionally focused on marine environments, growing evidence suggests that freshwater plastic pollution presents similar environmental risks to marine plastic pollution [9]. One of the most important risks is the impact of species entanglement. Data collected using a citizen science approach found that freshwater aquatic birds were the group most commonly entangled, mostly with lethal consequences, and mostly caused by fishing gear and six-pack bottle rings [10]. Even more common than entanglement in that study was the use of plastic debris in freshwaters by birds for nest building, which also has potential for significant impacts but has been rarely studied [10]. Another major impact of plastic on freshwater species is via ingestion. It is well known that many marine species, including turtles, birds, and marine mammals, eat anthropogenic plastic debris and die from consequent gastrointestinal blockages, perforations, and malnutrition, as well as suffer sublethal impacts [11]. While freshwater species are much less well studied, there is significant evidence of similar exposure and consequences of plastic ingestion in freshwater turtles [12].

In addition to direct impacts on organismal health, ingestion may also have major impacts on the ecosystem, especially from ingesting small plastic particles. As with marine environments, freshwater plastics will fragment into microplastics (particles < 5 mm) and nanoplastics (particles < 0.001 mm), which pose additional hazards. Microplastics and nanoplastics are readily ingested by aquatic species, often leading to reduced fitness, higher mortality rates, and the potential for bioaccumulation up the food chain. A review found documented evidence of microplastic ingestion by 206 freshwater species ranging from invertebrates to mammals. More importantly, there is growing evidence that these ingested micro/nano plastics act as adsorption substrates for many highly toxic substances ranging from metals to pesticides [13]. They are thus vectors that transport and concentrate these toxins in freshwater organisms, which can lead to bioaccumulation up the food chain as well as harming the organism [14]. For example, a recent review of 46 papers found nano/microplastics increased the bioaccumulation of toxic organic compounds and metals in freshwater fishes by 58% and 42%, respectively [15]. Beyond these ecological threats noted above, riverine plastic and microplastic pollution can also undermine human well-being by contaminating drinking water supplies [16], limiting recreational opportunities [17], and increasing flood risks due to the blockage of water channels by massive amounts of accumulating plastic debris [18].

To date, most research in this area has focused on quantifying environmental impacts, while comparatively little attention has been devoted to understanding this issue from a social perspective. However, understanding how these risks are perceived by the public and by stakeholders who have a vested interest in the river’s health is fundamental to organizing collective actions. Given some emerging evidence that public and political awareness of plastic-related issues is increasing [19], contributing to growing support for national and international efforts to reduce plastic consumption and improve waste management [20], it is important to quantify perceptions on local scales. Understanding stakeholder and public perceptions is essential because these perceptions influence both policy debates and the implementation of pollution control strategies. Specifically, there is a need to examine (1) how the perceived risks of (micro)plastics compare to other pollutants, (2) how these perceptions vary across stakeholder groups, and (3) how risk perceptions shape support for different types of policy interventions aimed at pollution mitigation.

Socio-ecological research has consistently demonstrated the value of comparative stakeholder analysis in revealing how perceptions differ across groups [21,22,23]. Stakeholders bring diverse forms of knowledge, interests, and motivations to environmental issues, often resulting in differing perceptions of environmental risks and preferred interventions [24,25,26]. Comparative stakeholder analysis helps identify both discrepancies and areas of agreement among groups, which is vital for improving the social feasibility of policy solutions and building consensus around environmental management strategies [27]. For instance, if stakeholders perceive the risks of microplastic pollution differently, disagreement over appropriate interventions may arise. In contrast, shared risk perceptions may foster collective support for more effective policy interventions.

While there is a growing literature employing comparative stakeholder analysis in environmental contexts, few studies have explicitly examined how stakeholders perceive the risks of microplastic pollution relative to other pollutants. Even fewer have investigated which types of policy interventions stakeholders are more or less willing to support. Although it is generally accepted that stakeholder agreement influences the level of policy support, little attention has been paid to the types of policies being supported. Public policy literature suggests that different types of policy solutions—regulatory, distributive, redistributive, and constituent—garner varying levels of public and political support [28,29,30,31]. Regulatory and redistributive policies tend to be politically contentious and often face greater resistance, whereas distributive and constituent policies are typically less controversial and more widely accepted [28]. This distinction is important when analyzing risk perceptions, as higher perceived risk may increase willingness to support more interventionist policy solutions.

Therefore, to address these gaps, this study surveyed 419 members of the local public and 45 local stakeholders associated with the Tennessee River. Our analyses compare public and stakeholder knowledge of plastic pollution, perceived environmental and human health impacts, and preferences for various policy interventions. Given likely differences between the groups in terms of knowledge types, roles, and motivations, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H1.

There are significant differences between the public and stakeholder groups in their perceptions of the risk posed by various pollutants.

H2.

The public and stakeholder groups differ significantly in their support for policy solutions.

H3.

Different types of plastic-related risk perceptions will be associated with differing levels of support for government policy solutions.

Overall, this study finds that perceptions of pollution risks and preferences for policy interventions vary notably between the public and stakeholder groups. Across multiple pollutants, the public consistently perceived higher environmental and human health risks than stakeholders, particularly for plastics, microplastics, E. coli, and metals. Interestingly, despite these differences, stakeholders expressed stronger preferences for regulatory policy approaches, while public respondents showed greater variability. Importantly, the perceptions of microplastic harm emerged as the most consistent and significant predictor of support for all types of policy solutions, underscoring the importance of how risk perceptions shape willingness to engage with environmental policy.

2. Materials and Methods

This study used an online questionnaire to measure and compare local (1) public and (2) stakeholder perceptions regarding pollution and preferred policy solutions for the Tennessee River. In total, we surveyed 419 members of the public and 45 stakeholders (N = 464). The survey focused on six pollutants known to be present in the Tennessee River: plastic, microplastic, E. coli, agricultural contaminants, heavy metals, and excess sediment. Ethical approval for this research was granted by the University of Tennessee, Knoxville Institutional Review Board (UTK IRB-24-08472-XM).

2.1. Social Sampling Strategy

Participants were sampled from two distinct populations: (1) local public and (2) local stakeholders. The public sample consisted of residents from any of the 33 counties in East Tennessee, as designated by the state. This region was chosen due to its proximity to the Tennessee River headwaters in Knoxville. The stakeholder sample included individuals who, within the survey, self-identified as members of clubs or organizations associated with the Tennessee River.

Sampling followed a two-phase strategy. In the first phase, participants were recruited through the Qualtrics participant panel, which provided incentivization for online survey participation, resulting in 423 complete responses collected over a two-week period in February 2025. In the second phase, additional respondents were recruited opportunistically via Facebook groups affiliated with recreational use of the Tennessee River, including the Knoxville Rowing Association, University of Tennessee Rowing Club, Knoxville Open Water Swimmers, East Tennessee Bass Angling Club, East Tennessee Bank Fishing Club, and the Tennessee River Wakeboarding Club, yielding 41 additional responses. Notably, while this opportunistic approach was adopted to bolster the sample size, its non-probabilistic nature may reduce the representative nature of the sample to the broader population. As such, some caution must be adopted in considering the inferences drawn.

In total, we collected 464 responses, with 45 (9.70%) of respondents self-identified as stakeholders, while the remaining 419 respondents (90.30%) reported no club affiliation and were categorized as public participants.

2.2. Questionnaire Design

The survey instrument consisted of four sections: demographics, recreational behavior, perceived harm from pollutants, and preferences for policy solutions (see Supplementary S1). The same questionnaire was administered to both the Qualtrics and Facebook samples. Eligibility criteria included being at least 18 years old and residing within one of the 33 East Tennessee counties. All participants were informed of the voluntary nature of this study, its approximate 15-min completion time, its sole purpose for research, and that it aimed to assess perceptions rather than knowledge.

The first section collected demographic information, including education, gender, age, race, political affiliation, number of children, household income, and any organizational affiliation related to the Tennessee River. The second section asked about recreational behavior regarding river-based activities, including the type of activity, primary motivation, and duration of involvement.

Section three assessed perceptions of harm associated with six pollutants. Using a five-point Likert scale, participants were asked two questions, “Based on your understanding, how much do you think the following pollutants are currently harming the environmental health of the Tennessee River?” and “Based on your understanding, how much do you think the following pollutants are currently harming human health in relation to the Tennessee River?”

The fourth section examined support for policy solutions targeting plastic and microplastic pollution. Eight hypothetical policies were developed, grounded in Lowi’s four policy typologies: distributive, regulatory, redistributive, and constituent [28]. Each typology included two example policies (see Supplementary S1). For instance, one distributive policy read, “Local government provides financial incentives to local businesses to reduce plastic waste,” while a regulatory policy stated, “Ban the sale of single-use plastics.” Respondents rated their support for each policy using a five-point Likert scale.

2.3. Data Analysis

Survey data were downloaded and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 29.0; Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp., 2023). A Shapiro–Wilk test confirmed that the data violated the assumption of normality, making non-parametric tests appropriate. Analyses were conducted using 90%, 95%, and 99% confidence intervals to identify both conventional and marginal significance.

To compare public and stakeholder perceptions regarding pollutant impacts on environmental and human health, and policy solution preferences, a series of Mann–Whitney U tests were performed, as this test is suitable for comparing differences between two independent groups. For policy solution preferences, new variables were created by averaging respondents’ scores for the two policy items within each typology (distributive, regulatory, redistributive, and constituent). An additional variable, total policy support, was computed by averaging respondents’ scores across all policy items.

To examine the relationship between risk perceptions and policy support, a series of rank-based linear regression models was conducted using the full sample. Composite harm scores were created for plastic and microplastic pollution by averaging respondents’ ratings of perceived harm to both environmental and human health, resulting in single risk perception scores for each pollutant. Reliability analyses indicated acceptable internal consistency for the composite scores: plastic (α = 0.763) and microplastic (α = 0.822), both exceeding the conventional threshold of 0.70. Four regression models were estimated—one for each policy typology—using plastic and microplastic composite scores as predictors. This approach aimed to isolate the influence of plastic-specific risk perceptions on support for different policy interventions.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.1.1. Public Sample Description

The public sample consisted of 419 respondents. The majority of public respondents were aged 45 and older, with 19.6% between 55 and 64 years, 19.8% between 45 and 54 years, and 31.0% aged 65 and older, indicating a generally older sample. Only 3.1% were between 18 and 24 years old. The sample was predominantly White (94.9%), with small proportions identifying as Black (2.4%), Asian (1.0%), or Other (0.7%). Educational attainment was relatively diverse: 25.5% held a high school diploma or GED, 22.4% had some college but no degree, 19.8% held a bachelor’s degree, and 15.0% had a graduate degree. Politically, most public respondents identified as Republican (46.1%), followed by Independent (27.0%), Democrat (16.9%), and Undecided (10.0%). The majority (76.8%) reported having no children, while 12.4% had one child and 6.5% had two. Income levels were varied, with the largest group earning between $25,000 and $49,999 (28.6%). Additionally, 21.7% earned less than $25,000, while roughly 20% each earned between $50,000 and $74,999 and between $100,000 and $149,999. In terms of gender, 67.3% of respondents identified as female and 32.7% as male.

3.1.2. Stakeholder Sample Description

The stakeholder sample included 45 respondents. Stakeholders were mostly concentrated in the 45–54 (28.9%) and 35–44 (22.2%) age groups. Most stakeholders identified as White (90.7%), with smaller proportions identifying as Black (2.3%), Asian (2.3%), or choosing not to disclose their race (4.7%). Compared to the public sample, stakeholders exhibited higher educational attainment, with 22.2% holding a bachelor’s degree and 20.0% holding a graduate degree. Only 2.2% of stakeholders had not completed high school. Political affiliations were relatively balanced among Democrats (31.1%), Republicans (31.1%), and Independents (33.3%), with a small portion identifying as Undecided (4.4%). The majority of stakeholders (60.5%) reported having no children, while 23.3% had one child and 11.6% had two. Stakeholders were more concentrated in middle to upper income brackets, with 22.7% earning $100,000–$149,999, 18.2% earning $50,000–$74,999, and 15.9% earning $25,000–$49,999. Gender distribution was nearly even, with 51.1% identifying as male and 48.9% as female.

3.2. Risk Perception and Environmental Health

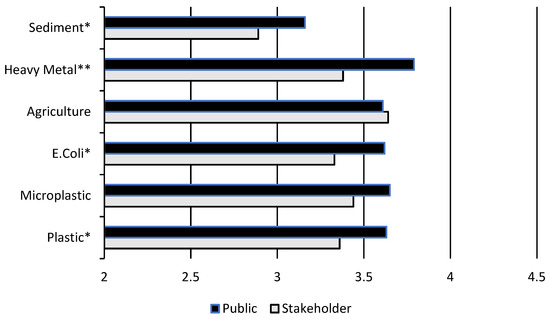

Significant differences emerged between the public and stakeholders regarding perceptions of environmental harm associated with pollutants (Figure 1). Using Mann–Whitney U tests, the public perceived plastic (z = –1.72, p = 0.086), E. coli (z = –1.68, p = 0.092), sediment (z = –1.66, p = 0.098), and metals (z = –2.43, p = 0.015) as significantly more harmful to the environment than stakeholders, all at at least the 90% confidence level. However, no significant differences were observed between the groups for perceptions of environmental harm related to microplastics or agricultural runoff.

Figure 1.

Mean public (solid black bars) and stakeholder (solid grey bars) perceptions of environmental risk across six pollutants, measured on a five-point Likert-scale (1, very low risk to 5, very high risk). Asterisks indicate significance levels: p < 0.10 (*) and p < 0.05 (**).

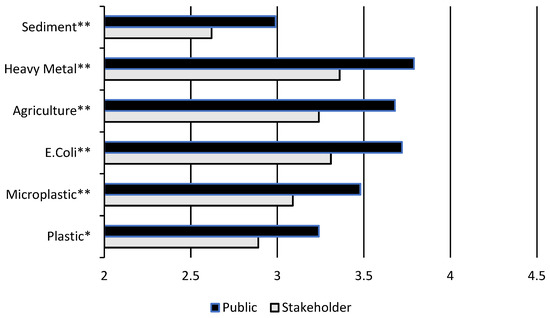

3.3. Risk Perception and Human Health

The public consistently perceived pollutants as more harmful to human health compared to stakeholders (Figure 2). Specifically, the public reported significantly higher perceived risks for plastic (z = –1.89, p = 0.059), microplastics (z = –2.09, p = 0.036), sediment (z = –2.05, p = 0.041), heavy metals (z = –2.23, p = 0.025), E. coli (z = –2.37, p = 0.018), and agriculture (z = –2.40, p = 0.017) as significantly more harmful to human health than stakeholders. These results indicate a consistent pattern where the public expresses greater concern regarding human health risks across all pollutant types.

Figure 2.

Mean public (solid black bars) and stakeholder (solid grey bars) perceptions of human health risk across six pollutants, measured on a five-point Likert-scale (1, very low risk to 5, very high risk). * Asterisks indicate significance levels: p < 0.10 (*) and p < 0.05 (**).

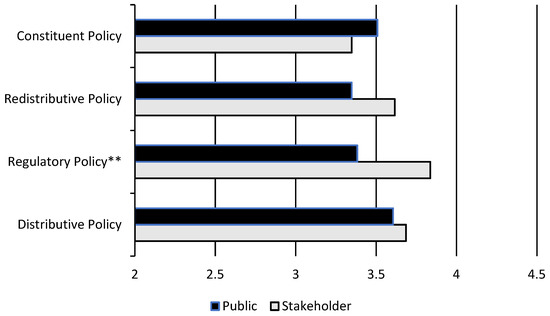

3.4. Policy Solution Preferences

When examining differences in preferences for public policy solutions, the results (Figure 3) reveal significant differences between stakeholders and the public for only one policy solution type. Using the Mann–Whitney U test, stakeholders showed significantly stronger preferences for regulatory policy (z = −2.73, p = 0.006) compared to the public. No statistically significant differences were found for distributive policy, redistributive policy, or constituent policy. Furthermore, when evaluating overall policy support—calculated as respondents’ average support across all policy types—no significant difference emerged between public and stakeholder groups (z = –1.06, p = 0.287). This suggests that despite some variation in the types of policies preferred, both groups were similarly supportive of policy action to address pollution more broadly.

Figure 3.

Mean public (solid black bars) and stakeholder (solid grey bars) policy solution preferences, measured on a five-point Likert scale (1, no support to 5, full support). ** Asterisks indicate significance levels: p < 0.05 (**).

3.5. Risk Perception and Policy Solution Preferences

Finally, a series of rank-based linear regression models was conducted to assess whether perceived harm from plastic and microplastic pollution predicted support for four types of policy solutions: distributive, regulatory, redistributive, and constituent (see Table 1). Across all models, perceived harm from microplastics consistently emerged as a significant and positive predictor of policy support. Specifically, microplastic harm significantly predicted support for distributive (β = 0.258, p = 0.001), regulatory (β = 0.466, p < 0.001), redistributive (β = 0.413, p < 0.001), and constituent (β = 0.288, p < 0.001) policies, all at or beyond the 99% confidence level. In contrast, perceived harm from plastic was only marginally associated with support for distributive policies (β = 0.133, p = 0.094) and was not a significant predictor of support for regulatory (β = –0.098, p = 0.215), redistributive (β = –0.117, p = 0.150), or constituent (β = 0.040, p = 0.621) policies. These findings suggest that the perceptions of microplastic harm, more so than plastic pollution in general, are a key driver of support for pollution-related policy interventions.

Table 1.

Summary of rank-based linear regression models assessing whether perceived harm from plastic and microplastic pollution relates to support for four types of policy solutions: distributive, regulatory, redistributive, and constituent. * Asterisks indicate significance levels: p < 0.10 (*), p < 0.05 (**), and p < 0.01 (***).

4. Discussion

While riverine plastic and microplastic pollution has become an increasingly important topic in ecological research, comparatively little attention has been paid to its social dimensions. There is limited understanding of how people perceive these forms of pollution and how such perceptions shape their preferences for policy interventions. This study contributes to addressing this gap by examining differences between public and stakeholder perceptions of pollutant risks and preferred policy responses related to the Tennessee River—one of the most plastic-polluted rivers globally [5,6]. To contextualize perceptions of plastic and microplastic pollution, we assessed them alongside four other common pollutants found in the Tennessee River. Given likely differences in priorities, knowledge, and values between the two groups, we hypothesized that public and stakeholder perceptions would differ.

Our first hypothesis (H1) predicted significant differences between the public and stakeholder groups in their perceptions of the risks posed by various pollutants. The results supported this hypothesis. Across both environmental and human health dimensions, the public consistently perceived higher levels of risk from pollutants than the stakeholders. These differences were especially pronounced for E. coli and heavy metal pollutants. More broadly, the public expressed greater and more widespread concern across all pollutant types (though not all at a statistically significant level), reflecting a heightened perception of environmental and human health risks relative to stakeholders. Our second hypothesis (H2) proposed that the public and stakeholder groups would differ significantly in their support for policy solutions. This hypothesis received partial support. While most policy preferences did not differ significantly between groups, stakeholders expressed significantly stronger support for regulatory policy, which is generally considered the most restrictive and enforceable form of intervention. This finding suggests that although both groups were similarly supportive of pollution mitigation overall, stakeholders were more inclined to favor formal regulatory approaches. Finally, our third hypothesis (H3) predicted that different types of plastic-related risk perceptions would be associated with varying levels of support for policy solutions. The results provided strong support for this hypothesis. Perceived harm from microplastics consistently and significantly predicted support for all four policy types: distributive, regulatory, redistributive, and constituent. In contrast, perceived harm from plastic was only marginally significant in predicting distributive policy support and was unrelated to the other three policy types. These findings suggest that concern about microplastic pollution, specifically—not plastic pollution more broadly—is the key driver of support for government intervention in this case.

At first glance, these results may appear counterintuitive. It would be reasonable to expect that stakeholders, given their direct exposure to the Tennessee River and firsthand knowledge of its conditions, would report higher perceptions of pollution risk. However, the opposite pattern emerged. On average, the public consistently reported higher levels of perceived risk from pollutants than stakeholders did. Regarding environmental harm, the public reported five out of the six pollutants as posing a greater risk when compared to the stakeholders, though not all differences were statistically significant. For perceived human health impacts, the pattern was even more striking, with the public reporting higher levels of risk for all six pollutants, several of which reached statistical significance.

One possible explanation for this counterintuitive pattern is that stakeholders may have become habituated to pollution in the Tennessee River. Frequent exposure to the river’s conditions may normalize certain forms of pollution, leading stakeholders to perceive them as less threatening compared to members of the public who are less regularly exposed. This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as risk normalization, is well-documented in environmental risk perception literature, especially as it relates to climate change [32] and air pollution risks [33,34,35]. For example, Yan Zhang and others (2020) found that urban residents in China become habituated to severe air pollution, which reduces their perception of it as a risk [33]. Similarly, residents in Texas, USA, who live near large industrial sources of toxic industrial air pollution, have normalized chronic risks of industrial pollution [35]. In this case, stakeholders along the river, particularly those engaged in recreation, seem to become desensitized to the threats imposed by the plastic contaminants in the Tennessee River. Perhaps they adjust their risk perceptions over time as a coping mechanism or from a perceived lack of immediate negative outcomes.

A similar dynamic may help explain why the perceptions of microplastic harm were the most consistent predictor of policy support across all intervention types in this study. Social science research suggests that public concern about microplastics is often shaped more by heightened perceptions of risk than by established scientific evidence regarding their actual ecological and human health impacts [20,36,37]. Recent meta-analyses highlight that a sharp increase in media attention on microplastics has likely amplified public perceptions of their risks [38]. While this surge in attention has helped bring plastic pollution to the policy agenda, it has also raised concerns among scientists that alarmist or oversimplified media reporting may distort risk perceptions, leading to disproportionate public and political focus on microplastic pollution relative to other, potentially more severe, environmental threats [38]. Our findings align with this pattern; although both groups expressed broad concern about a range of pollutants, it was perceived microplastic harm specifically that consistently predicted stronger support for a variety of policy interventions, suggesting that media-amplified risk perceptions may be playing a significant role in shaping policy preferences.

Given these findings, future research should dive deeper into the possible role of the risk normalization phenomenon and the role of the media in heightening awareness of microplastics. In particular, the use of devoted survey questions may be able to tease out their respective levels of influence on perceptions. More broadly, future research may also look to broaden the scope of investigation to include a more diverse group of stakeholders. Due to practical sampling limitations, we did not include other relevant stakeholder groups, such as non-profit organizations involved in pollution mitigation and local resource managers and decision makers. The inclusion of such groups would likely broaden the scope of inference and further increase the relevance of findings to local-level action.

Overall, perhaps the most important finding of this study is that stakeholders showed a stronger preference for regulatory policy solutions compared to the public. Conventional wisdom in environmental policy scholarship suggests that higher perceived risk leads individuals to oppose policies that increase and support policies that reduce that risk [39]. However, this study finds the opposite pattern; the public perceives significantly higher levels of risk from pollutants in the Tennessee River than stakeholders, but does not exhibit significantly greater support for policies to mitigate that risk. Instead, stakeholders, despite perceiving lower levels of risk, are more likely to support regulatory policies. One possible explanation is that individuals or groups with closer proximity to a problem are often more likely to favor regulatory policy [40]. This is because regulatory policies typically impose restrictions and costs on producers—in this case, the sources of pollution—while stakeholders benefit from reduced risks and improved environmental outcomes without directly bearing those costs. In other words, stakeholders gain from pollution reduction without necessarily absorbing the regulatory burdens themselves.

Alternatively, the public’s lower support for regulatory solutions may also be explained by variations in the ideological orientations of respondents. In our study, the public sample was predominantly Republican (46.1%) or Independent (27.0%), while the stakeholder sample was more balanced among Democrats (31.1%), Republicans (31.1%), and Independents (33.3%). A substantial body of research demonstrates that support for environmental policy is often shaped more by values, belief systems, and political identities than by risk perception alone [41]. For example, research has found that even when individuals acknowledge the harms associated with environmental concerns like climate change, they may resist regulatory interventions if such policies conflict with deeply held beliefs about government intervention, market freedom, or personal responsibility [41]. Moreover, other research has shown that subjective factors, such as ideology, are often more influential in shaping policy preferences than the actual perceptions of environmental risk [42]. This suggests that the politicization of environmental policy may be reducing support for regulation within the public sample, reflecting ideological resistance rather than a lack of risk awareness [42]. In the context of the Tennessee River, this may mean that concerns about human and ecological health, while recognized, may not be the most important factor influencing public support for mitigation policies aimed at reducing pollution.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microplastics4030040/s1, S1: The questionnaire survey tool.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G.; methodology, R.M. and M.M.; validation, R.M.; formal analysis, S.G. and R.M.; investigation, S.G. and R.M.; data curation, S.G.; writing—original draft, S.G., R.M. and M.M.; writing—reviewing and editing, R.M. and M.M.; funding acquisition, S.G. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a University of Tennessee, Knoxville, internal research grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Tennessee, Knoxville (protocol code UTK IRB-2408472-xm and date of approval 3 March 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy considerations of survey respondents.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Environment and Energy Study Institute. The Tennessee River Resilient and Healthy Rivers Series. 2024. Available online: https://www.eesi.org/briefings/view/121124rivers (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Elkins, D.; Sweat, S.C.; Kuhajda, B.R.; George, A.L.; Hill, K.S.; Wenger, S.J. Illuminating hotspots of imperiled aquatic biodiversity in the southeastern US. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 19, e00654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennessee Valley Authority. UTIA Study Finds $1M-Per-Mile Economic Impact of TVA Reservoirs. 2017. Available online: https://www.tva.com/news-media/releases/utia-study-finds-1m-per-mile-economic-impact-of-tva-reservoirs (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation. Tennessee’s Clean Water Act Monitoring & Assessment Report. 2024. Available online: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/5d4aa1dae4754b98a6cd9baf01d1477d (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Tennessee Aquarium. A Plastic Pandemic German Scientist’s Analysis Finds Staggering Levels of Microplastic Pollution in Tennessee River. 2018. Available online: https://tnaqua.org/newsroom/a-plastic-pandemic-german-scientists-analysis-finds-staggering-levels-of-microplastic-pollution-in-tennessee-river/ (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Greeves, S. Tracking Trash: Understanding Patterns of Debris Pollution in Knoxville’s Urban Streams. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Chu, R.; Pei, Y.; Ma, J. Effect of landfill age on the physical and chemical characteristics of waste plastics/microplastics in a waste landfill sites. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 306, 119366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadu, I.; Farsang, A.; Kiss, T. Quantification of macroplastic litter in fallow greenhouse farmlands: Case study in southeastern Hungary. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023, 35, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blettler, M.C.; Wantzen, K.M. Threats underestimated in freshwater plastic pollution: Mini-review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2019, 230, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blettler, M.C.; Mitchell, C. Dangerous traps: Macroplastic encounters affecting freshwater and terrestrial wildlife. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 798, 149317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, L.; Schuyler, Q.; Wilcox, C.; Hardesty, B.D. Plastic pollution is killing marine megafauna, but how do we prioritize policies to reduce mortality? Conserv. Lett. 2021, 14, e12781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clause, A.G.; Celestian, A.J.; Pauly, G.B. Plastic ingestion by freshwater turtles: A review and call to action. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo-Santos, V.M.; Brito, M.F.; Manoel, P.S.; Perroca, J.F.; Rodrigues-Filho, J.L.; Paschoal, L.R.; Goncalves, G.R.L.; Wolf, M.R.; Blettler, M.C.M.; Andrade, A.C. Plastic pollution: A focus on freshwater biodiversity. Ambio 2021, 50, 1313–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, V.; Chauhan, J.S. Microplastic in freshwater ecosystem: Bioaccumulation, trophic transfer, and biomagnification. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 9389–9400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, F.; Pavlaki, M.D.; Loureiro, S.; Sarmento, R.A.; Soares, A.M.; Tourinho, P.S. Systematic Review of Nano-and Microplastics’(NMP) Influence on the Bioaccumulation of Environmental Contaminants: Part II—Freshwater Organisms. Toxics 2023, 11, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Redondo-Hasselerharm, P.E.; Nor, N.H.M.; De Ruijter, V.N.; Mintenig, S.M.; Kooi, M. Risk assessment of microplastic particles. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.B.; Maity, S.; Sarkar, A. Potential human health risk assessment of microplastic exposure: Current scenario and future perspectives. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Emmerik, T.H. The impact of floods on plastic pollution. Glob. Sustain. 2024, 7, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidbreder, L.M.; Bablok, I.; Drews, S.; Menzel, C. Tackling the plastic problem: A review on perceptions, behaviors, and interventions. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramm, J.; Völker, C. Understanding the Risks of Microplastics: A Social-Ecological Risk Perspective. In Freshwater Microplastics: Emerging Environmental Contaminants? Wagner, M., Lambert, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Graves, A.; Dandy, N.; Posthumus, H.; Hubacek, K.; Morris, J.; Prell, C.; Quinn, C.H.; Stringer, L.C. Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendtsen, E.B.; Clausen, L.P.W.; Hansen, S.F. A review of the state-of-the-art for stakeholder analysis with regard to environmental management and regulation. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 279, 111773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.J.; Martín-López, B.; García-LLorente, M.; Aguilera, P.A.; López, E.; Cabello, J. Social preferences regarding the delivery of ecosystem services in a semiarid Mediterranean region. J. Arid. Environ. 2011, 75, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J.H.; Görg, C.; Settele, J. Stakeholder involvement in ESS research and governance: Between conceptual ambition and practical experiences—risks, challenges and tested tools. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 16, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintas-Soriano, C.; Brandt, J.S.; Running, K.; Baxter, C.V.; Gibson, D.M.; Narducci, J.; Castro, A.J. Social-ecological systems influence ecosystem service perception: A Programme on Ecosystem Change and Society (PECS) analysis. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeves, S.; McGovern, R.; Castro, A. A social assessment of ecosystem services: A comparative stakeholder analysis of the Portneuf River Watershed, Idaho. Ecosyst. People 2025, 21, 2478568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowi, T.J. Four Systems of Policy, Politics, and Choice. Public Adm. Rev. 1972, 32, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Savani, M.; Shreedhar, G. Public support for ‘soft’ versus ‘hard’ public policies: Review of the evidence. JBPA 2021, 4, 1–24. Available online: https://journal-bpa.org/index.php/jbpa/article/view/220 (accessed on 26 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.B. Typologies, Taxonomies, and the Benefits of Policy Classification. Policy Stud. J. 2002, 30, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, E.; Axsen, J.; Jaccard, M. Exploring Citizen Support for Different Types of Climate Policy. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 137, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricart, S.; Gandolfi, C.; Castelletti, A. How do irrigation district managers deal with climate change risks? Considering experiences, tipping points, and risk normalization in northern Italy. Clim. Risk Manag. 2024, 44, 100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, C.H.; Li, D.; Zhang, H. Willingness to pay for environmental protection in China: Air pollution, perception, and government involvement. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 18, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, R.; Ripberger, J.; Fox, A.; Carlson, N.; Gupta, K.; Silva, C.; Jenkins-Smith, H. Where there’s smoke there’s fire: The relationship between perceived and objective wildfire smoke risk. Environ. Hazards 2024, 23, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.A.; Elliott, J.R.; Chavez, S. Community perceptions of industrial risks before and after a toxic flood: The case of Houston and Hurricane Harvey. Sociol. Spectr. 2018, 38, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, G.A., Jr. Stressor Exposures Determine Risk: So, Why Do Fellow Scientists Continue to Focus on Superficial Microplastics Risk? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 13515–13516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backhaus, T.; Wagner, M. Microplastics in the Environment: Much Ado about Nothing? A Debate. Glob. Chall. 2020, 4, 1900022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catarino, A.I.; Kramm, J.; Völker, C.; Henry, T.B.; Everaert, G. Risk posed by microplastics: Scientific evidence and public perception. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 29, 100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoutenborough, J.W.; Vedlitz, A.; Liu, X. The Influence of Specific Risk Perceptions on Public Policy Support: An Examination of Energy Policy. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2015, 658, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkland, T.A. Lessons of Disaster: Policy Change After Catastrophic Events; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Available online: https://muse.jhu.edu/book/13054 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Kahan, D.M.; Peters, E.; Wittlin, M.; Slovic, P.; Ouellette, L.L.; Braman, D.; Mandel, G.N. The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 732–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.; Shelley, T.O.; Chiricos, T.; Gertz, M. Environmental Risk Exposure, Risk Perception, Political Ideology and Support for Climate Policy. Sociol. Focus 2017, 50, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).