Abstract

Sewage sludge was pyrolyzed at mass rate of 500 g/h in a bench-scale rotary kiln for methane-rich syngas production. The tested process variables were the pyrolysis temperature (600, 700 and 800 °C) and the CaO addition to the process (0 and 0.2 CaO/dried sewage sludge). Product distribution (char, condensable product, and gas) as well as their chemical composition were determined. At CaO/dried sewage sludge mass ratio equal to 0, with the increasing pyrolysis temperature from 600 to 800 °C, the gas yield increased from 31.4% to 45.6 wt.%, while the char yield decreased from 41.3 to 37.5 wt.%. At CaO/dried sewage sludge mass ratio equal to 0.2, significantly different product distribution and chemical composition were detected. In fact, syngas showed a net CO2 concentration reduction (under 10 mol %), while methane concentration increased at 600 and 700 °C up to 54 and 42 mol %, respectively. The total gas yield increased, probably because of the CaO behavior as catalyst of volatiles conversion reactions (cracking and reforming). In fact, the condensable product yield decreased up to 7 wt.% at 800 °C. At CaO/dried sewage sludge equal to 0.2 and pyrolysis temperature of 700 °C, the maximum methane yield of 150 g/kg SS was detected.

1. Introduction

Sewage sludge from municipal and industrial wastewater treatment plants contains inorganic and organic substances. In line with the principles of the circular economy, in 1986 the EU adopted Council Directive 86/278/EEC to recycle the nutrients contained in this kind of waste and encouraged its appropriate use in agriculture, without harmful effects on soil, plants, animals, and humans. In implementation of Council Directive 86/278/EEC, Italy adopted Legislative Decree No. 99 of 27 January 1992, which establishes the national criteria for the agricultural use of sewage sludge. In 2018, Italian law No. 130/2018 set threshold values for the concentration of a number of additional substances in sewage sludge (i.e., C10–C40 hydrocarbons, PAHs, PCDD/PCDFs, PCBs, toluene, selenium, beryllium, arsenic, and total and hexavalent chromium) that were not included in Legislative Decree N° 99/92. In 2022, in Italy, municipal sewage sludge production was more than three million tons on wet basis. Despite efforts to regulate the use of this waste to encourage its recycling, in 2022 in Italy, 54.2% of sewage sludge was sent for disposal, only 43.4% for recovery, and 2.4% remained in storage [1]. The main concern hindering its use in agriculture is due to the potential impact of its contaminants on health, safety, and the environment [2]. Consequently, alternative methods to recycling for agricultural use could solve the management challenges of sewage sludge; among these, thermochemical valorization is worthy of consideration [3].

Usually, the organic fraction of sewage sludge is higher and mostly biodegradable. Biodegradability encourages biological treatments (aerobic digestion, anaerobic digestion, and composting) where microorganisms break down organic pollutants and stabilize the sludge. Anyway, pathogen microorganisms, such as Salmonella and Streptococcus of human dejection that could be found in the sludge are dangerous for human health. From this point of view, thermal treatments, such as combustion, gasification, and pyrolysis, are methods to sterilize the sludge, to reduce the volume of the waste, and to recover secondary energy streams [4,5]. Additional drying of sewage sludge after dewatering is necessary to decrease the water content of the sludge and to increase its heating value before any thermal treatment; however, the energy duty required for the drying can be recovered by the thermal waste of the treatments.

Combustion or incineration is the most established and widely implemented thermochemical treatment process of the sewage sludge with the highest technological readiness level. There are currently hundreds of large sewage sludge incinerators in operation across the world, most of which generate heat and power, as well as converting the sludge to ash [6]. Gasification and pyrolysis as thermal treatment methods are also gaining traction as a suitable approach; however, several technological gaps must be faced, and they are underutilized worldwide compared to combustion.

Gasification is a thermochemical process for the conversion of a solid organic material, occurring through the partial oxidation of the feedstock at temperatures of 700–900 °C by means of a gasifying agent (usually air, oxygen, steam), and produces syngas, a mixture of CO, H2, CH4, C2-C3, and CO2, which is a valuable source for energy production and a precursor for the chemical industry [7]. By reducing atmosphere of gasification, SO2, NOx, dioxins, and furans emissions are drastically lowered compared to incineration [8,9]. From this point of view, gasification is a more environmentally sustainable alternative to conventional incinerators. Gasification is not as widely established as incineration, but it is more advanced than pyrolysis in terms of technological development. The TRL for the treatment of sewage sludge is between six and seven for gasification and five for pyrolysis in terms of commercial viability [10,11].

Pyrolysis is a thermochemical process for the conversion of a solid organic material in inert atmosphere at temperature range of 400–800 °C into char, oil, and gas, with their relative distribution depending on temperature, residence time of the feedstock and vapors in the reactor, heating rate, feedstock reactivity and particle size [12]. Pyrolysis processes can be classified in the following categories: slow, fast, and flash pyrolysis. Other emerging technologies are microwave pyrolysis, catalytic pyrolysis, hydro-pyrolysis, catalytic hydro-pyrolysis and hydrous pyrolysis [13].

Slow pyrolysis adopts relatively low temperature (400–500 °C), long residence time of the feedstock (up to hours), and low heating rate of about 10 °C/min. It is mainly used for char production (35–40 wt. %) [14]. Fast pyrolysis occurs at about 600 °C, with a heating rate of about 100–200 °C/s and a vapor residence time below 5 s, with feedstock particle size below 1 mm. Its main product is pyrolysis oil (about 50 wt. %). Flash pyrolysis occurs at 800–1000 °C, with heating rate higher than 1000 °C/s, vapor residence time below 0.5 s, and biomass particle size below 0.2 mm [15]. Several types of reactors were adopted to approach the target product such as batch and semi-batch, fixed and fluidized bed, conical spouted bed reactors, rotating cone, and rotary kilns [16].

Both gasification and pyrolysis are underutilized in many regions because of gaps in technological implementation and regulatory support. Regarding pyrolysis, the main technological bottlenecks are (1) lower heating value of pyrolysis gas compared to traditional fuel gas such as natural gas; (2) pyrolysis gas pollution with condensable organic molecules; (3) the challenging operation and maintenance of the plant because of the production of condensable organic vapors that could condense in the cold spots of the plant and clog equipment. Moreover, the valorization of secondary streams of the process, i.e., pyrolysis oil and char, is not profitably established. In this frame, the authors of the present work have carried out experimental tests in a bench-scale rotary kiln to face the issue of the relatively low heating value of pyrolysis gas by addressing the pyrolysis towards the higher methane yield and CO2 reduction. Methane-rich syngas has undiscussable advantages compared to conventional syngas that are using actual natural gas infrastructure, long-term storage, improving energy security, and versatility for heat, power, and transport. CO2 capture from the process gas is a foot towards the energy transition. Furthermore, useful data to increase the technological readiness level of sewage sludge pyrolysis were collected. Before establishing the experimental plan, a literature survey was conducted about this topic that is briefly summarized in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Scientific paper about sewage sludge pyrolysis.

Zangh et al. pyrolyzed sewage sludge and co-pyrolyzed it with low-rank coal in a thermogravimetric analyzer. They investigated the effect of pyrolysis temperature, heating rate, and mixing ratio on weight loss, energy changes, and kinetics. The main reaction stage of SS occurred at 180–580 °C, giving an activation energy of 265.91 kJ mol−1 calculated by model-free methods. SS pyrolysis process can be divided into dehydration, decomposition, and coking stages [17].

Gao et al. studied pyrolysis behavior of dried sewage sludge by thermogravimetric–Fourier transform infrared analysis (TG–FTIR) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) to investigate thermal decomposition and kinetics analysis. Two weight loss peaks were presented in the pyrolysis reaction in the ranges of 186–296 °C and 296–518 °C, with activation energy of 82.28 kJ mol−1 and 48.34 kJ mol−1, respectively. Moreover, they used a batch tubular laboratory furnace to pyrolyze 120–200 g of sewage sludge at temperature range of 450 to 650 °C at different heating rate to simulate slow and fast pyrolysis. The maximum tar yield obtained was 46.14% at the temperature of 550 °C under fast pyrolysis conditions [18].

Gasco et al. pyrolyzed four sewage sludges in a batch (20 g/batch) electrical furnace to produce activated carbon. Pyrolysis temperature was 650 °C, with a heating rate of 3 °C/min. Activated carbon with an iodine number of 527–554 mg I2/g was produced [19].

Guo et al. probed the effects of temperature (300–700 °C) and atmosphere (100% N2, 10 CO2/90%N2, 100% CO2) on the properties of biochar and gases obtained by sludge pyrolysis in a batch (1 g/batch) horizontal tube furnace. It was found that the CO, SO2, H2S, and NO emissions increased with increasing pyrolysis temperature, with CO as the main gaseous product. In the temperature range of 300–600 °C, the CO emission obtained for pyrolysis in a CO2 atmosphere was lower than that under a N2 atmosphere [20].

Agrafioti et al. pyrolyzed sewage sludge in a batch (20 g/batch) muffle furnace at temperature of 300–500 °C. Biomass chemical impregnation with K2CO3 and H3PO4 was investigated on the yield and quality of biochar. The highest biochar yield was obtained at a temperature of 300 °C. Biochar surface area increased with increasing pyrolysis temperature and was maximized (90 m2/g) by impregnating biochar with K2CO3 [21].

Barry et al. carried out slow pyrolysis of sewage sludge in a batch (100 g/batch) mechanically fluidized reactor and fast pyrolysis in a continuous fluidized bubbling bed (600 g/h). Slow pyrolysis biochar yields decreased from 51.6 wt% at 300 °C to 32 wt% at 500 °C. Similarly, fast pyrolysis biochar yields also decreased from 30 wt% at 400 °C to 26 wt% at 500 °C. An enthalpy of pyrolysis of 2.2 MJ kg−1 was calculated [22].

Khanmohammadi et al. pyrolyzed urban sewage sludge at temperature range of 300–700 °C in an electrical batch (1.4 kg/batch) furnace to study product distribution and biochar properties. Biochar yield significantly decreased from 72.5% at 300 °C to 52.9% at 700 °C, whereas an increase in temperature increased the gas yield. Biochar pH and electrical conductivity increased by 3.8 and 1.4 dS m−1, with the increasing temperature [23].

Pedrosa et al. pyrolyzed sewage sludge in a continuous (1 kg/h) rotary kiln plant. The maximum liquid yield was 10.5%, obtained at the temperature of 500 °C. The maximum char yield was 61.9%, obtained at 500 °C. The highest gas phase yield was 23.3%, obtained at 600 °C [24].

Li et al. pyrolyzed sewage sludge mixed with kaolin/zeolite at 450–650 °C in a rotary kiln reactor with a feedstock rate of 60 g/h to improve the immobilization of heavy metals in pyrolytic carbon. They found the effects of kaolin/zeolite on the immobilization efficiency mechanism of heavy metals (Cu, Zn, Cd, Pb, and Cr) in pyrolysis biochar [25].

Chen et al. gasified at 650–750 °C, by steam, sewage sludge in a laboratory batch (2 g/batch) fixed bed. CaO was used as the active sorbent of CO2, supported on Al2O3, La2O3, and ZrO2. The in situ CO2 removal produces hydrogen-rich syngas, and the addition of transition metal catalyst such as Co enhanced the sorbent activity. The hydrogen yield increased with the gasification temperature [26].

Trinh et al. executed fast pyrolysis of sewage sludge in a centrifuge reactor having a feedstock rate of 1.3 kg/h at temperature in the range 475–625 °C. The product distributions of fast sewage sludge pyrolysis with respect to organic oil, gas, char, and reaction water were determined, and the char and bio-oil properties were chemically characterized. An increasing gas yield and a decreasing char yield were observed with the increasing temperature. A maximal organic oil yield of 41 wt. % was obtained at the optimal reactor pyrolysis temperature of 575 °C [27].

From the above discussed works about sewage sludge pyrolysis, it can be argued that TG and TG-FTIR have been used to establish kinetic data such as activation energy and reaction orders. A strong interest was shown towards product distribution of pyrolysis of sewage sludge, and temperature was recognized as the most influent process variable. Most of the work was carried out at the laboratory scale using electrical furnace, with sewage sludge batches ranging from a few grams up to several hundred grams.

The paramount results, knowledge, and skills collected from the pyrolysis in batch electrical furnace are the base to run a continuous pyrolysis plant useful for an industrial scale up. In this framework, the novelty of this scientific work is the sewage sludge pyrolysis in a continuous rotary kiln with a feedstock rate of about 500 g/h. The influence of the pyrolysis temperature on the product distribution, as well as the sorbent addition into the reactor to chemisorb CO2 and to obtain a methane-rich gas, were investigated. Therefore, the investigation and discussion of scientifically relevant topics, such as sewage sludge disposal by pyrolysis in an industrially scalable rotary kiln plant and the CO2 sequestration by sorbent, enhance the scientific soundness of the paper.

2. Materials and Methods

In this paragraph the analytical procedures for the chemical characterization of the feedstock and of the pyrolysis products are carefully described together with the rotary kiln plant and the adopted method for the pyrolysis tests.

2.1. Feedstock Preparation and Characterization

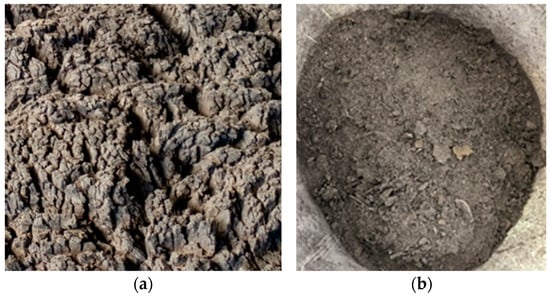

A southern Italian company working in the waste management supplied about 200 kg of raw sewage sludge, which was thoroughly analyzed in ENEA-Trisaia laboratories by proximate and ultimate analyses, metals, and heating value. To reduce biological hazards, the raw sewage sludge having a moisture of 73.7%, was dried in an oven at 105 °C for about 15 h according to ASTM D2216 [28]. The sewage sludge, after drying, contained cohesive large aggregates of 4–5 cm that posed significant challenges for feeding into the rotary kiln (Figure 1a). Consequently, a milling step was necessary to reduce the sludge to coarse granules with a diameter below 5 mm, as depicted in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

Details of feedstock used during pyrolysis test: (a) sewage sludge as received; (b) after thermal and mechanical pretreatment.

Analytical Techniques

Proximate Analysis. It was carried out by PerkinElmer TGA 7 thermogravimetric analyzer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) following the ASTM D1762-84 protocol [29].

Ultimate Analysis. It was carried out by Vario Macro Cube CHNS analyzer (Elementar, Langenselbold, Germany) following ASTM D5373) [30].

Lower Heating Value (LHV). The LHV was measured using an IKA Werke C5003 calorimeter cell (IKA, Staufen, Germany), in accordance with ASTM D5865 [31].

Metal Content Determination. A pretreatment step was performed to solubilize metals from the solid matrix: approximately 40 mg of sample was digested using a mixture of HNO3, HF, and H2O2. The resulting solution was filtered by a 0.45 µm membrane and analyzed via inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES).

2.2. Sampling and Characterization of Pyrolysis Products

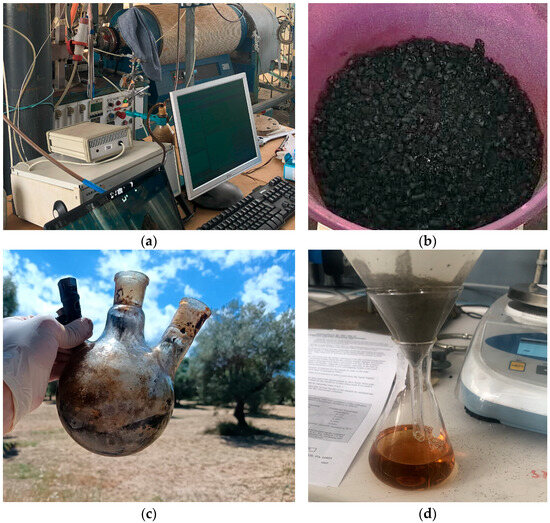

The products generated from the pyrolysis process—namely, non-condensable gases, char, and condensable products—were systematically collected and characterized (Figure 2). Char samples obtained at the end of each test, conducted at 600, 700, and 800 °C, were analyzed through proximate and ultimate analyses, as well as lower heating value (LHV) determination, following the procedures previously described. The condensable products were characterized as concerns LHV, viscosity, and moisture content.

Figure 2.

Overview of pyrolysis products: (a) quantification and compositional analysis of syngas; (b) char from pyrolysis; (c) condensable products from pyrolysis; (d) condensable products sample after homogenization and filtration, prepared for kinematic viscosity measurement.

Analytical Techniques

Syngas composition. The syngas composition—including H2, CO, CO2, CH4, CₙHₘ, and N2—was determined by continuous sampling upstream of the plant flare torch. Real-time measurements were performed by an Agilent 3000A mobile gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Condensable composition. Condensable compounds were identified using a GC-MS system (Agilent T5975), consisting of an HP 6890 gas chromatograph coupled with a quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with electron impact (EI) ionization.

Water content of condensable products. The water content in the condensable products was quantified by Karl Fischer titrator (Mettler DL18, Mettler-Toledo GmbH, Greifensee, Switzerland) following the ASTM E203 standard [32].

Kinematic viscosity of pyrolytic oil. The kinematic viscosity of the condensable product was measured using a Cannon-Fenske viscometer (CANNON Instrument Company, State College, PA, USA) following the procedure ASTM D445 [33].

Figure 2 illustrates the condensable product after homogenization and filtration, performed prior to kinematic viscosity measurement. The image refers to a sample obtained from a pyrolysis test conducted in the presence of a sorbent during thermal conversion. Under these process conditions, the condensable product is a well-homogenized and stable mixture, suitable for subsequent analytical procedures.

2.3. Bench-Scale Rotary Kiln Facility

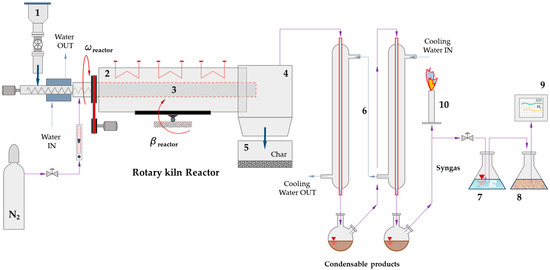

The pyrolysis tests were conducted by a bench-scale rotary kiln reactor (Figure 3). All pyrolysis tests were carried out with a fixed inclination angle of 3°, a rotation speed of 10 rpm, and a solid feed rate of 500 g/h. The reaction temperature varied between 600 °C and 800 °C. The selected parameters were designed to ensure an average residence time of the solid within the reactor ranging from 5 to 7 min, as estimated using Sullivan’s correlation so that the pyrolysis of the sewage sludge is ensured [34]. To assess the potential of CO2 sorption, additional pyrolysis tests were performed with same operating conditions by co-feeding a sorbent/catalyst material with the sewage sludge. CaO was selected as sorbent/catalyst for its chemical activity and low cost. It was uniformly mixed with the sewage sludge before loading the hopper. The mass ratio CaO/sewage sludge was 1/5 to approximately respect the stoichiometric coefficients of carbonatation reaction.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of bench-scale rotary kiln facility used during tests [12] (the description of numbered components is detailed in the text).

The main specifications of the rotary kiln test facility are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Main specifications of rotary kiln pyro-gasifier reactor.

As illustrated in Figure 3, the bench-scale pyrolysis system consists of a sequence of interconnected components designed to ensure controlled thermal conversion of the feedstock. The material was initially loaded into the hopper (1), from which it was conveyed into the rotary kiln reactor (3) via a screw feeder. The reactor was externally heated by an electric furnace (2). Temperature was controlled by PID (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) system. To prevent premature vaporization of the feedstock, the screw conveyor was equipped with a water-cooled jacket that maintained the wall temperature below the vaporization threshold. Sorbent/catalyst was premixed and roughly homogenized with sewage sludge before loading into the hopper. During pyrolysis, a known nitrogen flow was introduced into the reactor to enable syngas quantification. The pyrolysis process yielded three main products: char, condensable liquids, and non-condensable gases. The vapor and gas phases passed through the settling chamber (4), which was maintained above the condensation temperature (250 °C) to prevent premature liquefaction. Solid char was collected in the bottom reservoir (5), while condensable products—primarily pyrolytic oils and water—were liquefied in the condensation section (6). The remaining gas continued downstream. A fraction of the gas stream crossed two gurglers (7) and (8) and was analyzed by the online gas chromatograph (9). Most of the residual gas was safely combusted via a flare torch (10). More details about the experimental facility are available in our previous work [12].

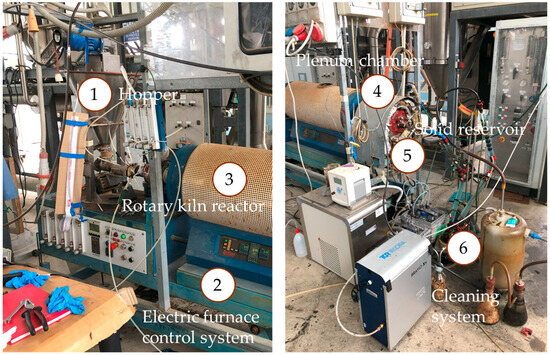

Figure 4 provides an overview of the bench-scale rotary kiln pyrolysis plant. The image highlights the feeding system with hopper (1) for feedstock storage, the rotary kiln reactor (3) with electric heaters and temperature controller (2), the settling chamber (4), where the solid fraction is separated from the gas and vapors stream before being collected in the solid reservoir (5), and the cleaning section (6).

Figure 4.

Pilot-scale rotary kiln pyro-gasifier test facility. The image shows (1) feedstock hopper; (2) temperature control system; (3) rotary kiln reactor with electric heaters; (4) settling chamber for gas–solid separation; (5) solid product reservoir; (6) cleaning section.

Mass balances were performed by measuring the residual char collected in the reservoir, the oil fraction in the condensation section, and the unreacted material inside both the reactor chamber and the feeding system. As previously mentioned, the gas fraction was determined by quantifying the amount of nitrogen introduced during the process and its mole fraction in the gas phase. This value was then used to verify mass closure with respect to the feeding material.

When the sorbent was employed, the amount of CO2 captured as CaCO3 was calculated by measuring the inorganic carbon fraction within the solid residue, which consisted of char, unreacted CaO, and CaCO3. All experiments were repeated at least three times to ensure the reproducibility of the results, and all data are reported as mean values.

Since the tests were conducted on a bench-scale pyrolysis reactor, where the heat required for conversion was supplied by an electrical system, accurate energy balances could not be performed. Based on the energy flow associated with each stream, it was only possible to estimate the overall energy term—calculated as the difference between energy input and output—which represents the conversion process as a whole, without the ability to distinguish individual contributions (e.g., system thermal losses and heat required for pyrolysis).

Before each pyrolysis test, nitrogen was injected into the plant to create an inert atmosphere. Once the nitrogen mole fraction reached approximately 95%, the feedstock feeding started. At the end of each test, nitrogen injection was continued to avoid oxidation of the char and remaining unconverted solid material. Nitrogen purging was stopped when the reactor temperature decreased to around 150 °C. After completing the shutdown procedures, the liquid and solid product fractions were collected and quantified.

3. Results

The results of proximate and ultimate analyses, along with the lower heating value (LHV) of sewage sludge, are summarized in Table 3. Sewage sludge proximate analysis shows an interesting volatiles content (66 wt. %), which assesses the feedstock as a valuable resource for conversion to gas. The relatively high ash content suggests investigating low-temperature conversion process, such as pyrolysis, to avoid issues related to fly ash, slagging, and fouling. Table 4 shows the metal content of sewage sludge, highlighting that Si, Ca, P, and Fe were the most abundant elements in the ash of the sewage sludge.

Table 3.

Chemical and physical properties of sewage sludge.

Table 4.

Metals of the sewage sludge.

The output pyrolysis products were char, condensable products, and permanent pyrolysis gas.

Char was a black granular solid that visually had the shape of the sewage sludge, although it was more comminuted by the mechanical forces and by thermochemical process to which the sewage sludge was subjected in the rotary kiln.

The condensable product was a dark brown, pungent smelling heterogeneous mixture of water and organic chemical compounds, both water-soluble both water-insoluble; the latter showed a pitchy consistency.

The permanent pyrolysis gas was a mixture of combustible molecules such as hydrogen, carbon monoxide, methane, and light hydrocarbons C2-C3, along with inert carbon dioxide. Pyrolysis gas can be considered as the extreme degradative product of cleavage of complex macromolecules that form sewage sludge.

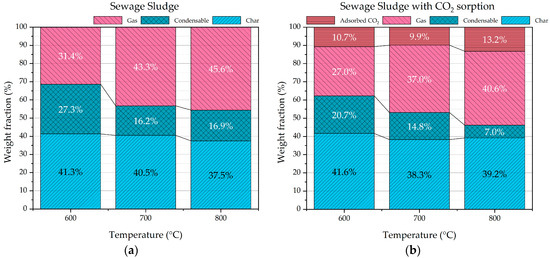

In the case of sewage sludge pyrolysis, it was observed that with the increasing pyrolysis temperature, the char yield has a decreasing trend from 41.3 to 37.5 wt.%, while the gas yield has a clear increasing trend from 31.4 to 45.6 wt.% (Figure 5a). This evidence agrees with the degradative thermal process of pyrolysis. As concerns the condensable product yield, a generally decreasing and fluctuating trend is observed in the explored temperature range.

Figure 5.

Product distribution of sewage sludge pyrolysis (a) and sewage sludge pyrolysis with CaO (b).

When CaO was added to the sewage sludge pyrolysis tests, an increasing trend of the gas yield was confirmed as function of the increasing pyrolysis temperature, and a marked decreasing trend of the condensable product was observed (Figure 5b). It is also very interesting to observe that when CaO is added to the process, the condensable product yield decreases from 27 to 21 wt.% at 600 °C, from 16 to 15 wt.% at 700 °C, and from 17 to 7 wt.% at 800 °C. It is very likely that CaO works as a catalyst for steam reforming, steam dealkylation, thermal cracking, and dry reforming reactions of condensable organic molecules that produce permanent gases such as CO, H2, CH4, and C2 and C3 hydrocarbons, as reported in several scientific papers. The detailed routes of catalytic mechanisms remain ambiguous because of the complexity of the multi-phase reaction system and because of the numbers of chemical species. Anyway, it is accepted that the organic molecule conversion starts with their absorption with H2O/CO2 on the CaO active sites. The basic sites of CaO can promote the dehydrogenation (cleavage of C-H), the dealkylation (cleavage of Caryl-C), and the ring-opening of tar molecules (cleavage of aromatic C=C) to form active carbon deposit and gas species (CxHy and H2). With reference to the topic of the present work, it is worth highlighting that dealkylation (reactions 1, 2, and 3), cracking, and hydrocracking (reactions 4 and 5) promote the formation of methane and light hydrocarbons C2–C3 [12,35,36,37]. In the following reactions (1–5), CnHm refers to heavy hydrocarbons, while CxHy refers to light hydrocarbons.

CnHm + H2O → CxHy + H2 + CO

CnHm + H2O → CxHy + H2 + CO2

CnHm + H2 → CxHy + CH4

CnHm → CxHy + H2

CnHm + H2→ CH4

At a fixed temperature, the total gas yield (gas+ adsorbed CO2) is higher when CaO is added to the process (Figure 5b) compared to the sewage sludge pyrolysis (Figure 5a). The catalytic effect of CaO is more evident at 800 °C, where a decrease in condensable product from 17 to 7 wt.% was observed together with an increase in total gas yield from 46 to 54 wt.%. This relevant result was obtained also with different feedstock such as dry digestate by using the same experimental condition and rig [12]. From a kinetic point of view, the conversion reaction rates of condensable organic products increase with the temperature.

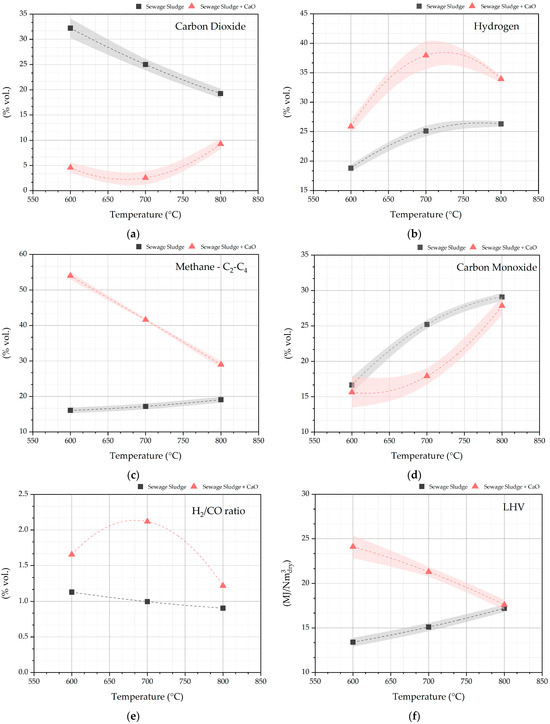

In Figure 6, the volumetric pyrolysis gas composition and heating value are plotted at pyrolysis temperatures (600, 700, and 800 °C). The interpolative curves are probable trends that should be confirmed by pyrolysis tests at stricter temperature range. The effect of the chemisorption of CO2 by CaO to form CaCO3 can be proved by the very low CO2 concentration in the pyrolysis gas when CaO is added to the pyrolysis of sewage sludge (reaction (6)). CO2 concentrations below 10 mol % were always detected (Figure 6a).

CaO + CO2 ↔ CaCO3 ΔH° = −178.3kJ mol−1

Figure 6.

Pyrolysis gas composition: CO2 (a) H2 (b), CH4 (c), CO (d); H2/CO (e); LHV (f).

CaCO3 formation is favored by lower temperatures because of the exothermicity of the reaction (1) and by high CO2 partial pressure. In fact, the highest reductions in CO2 concentration were observed at temperatures of 600 and 700 °C, when CaO is added to the process (Figure 6a). The chemical sorption of CO2 shifts the chemical equilibrium of the gas phase in the reactor. Thus, by adding CaO to the process at temperature of 600 and 700 °C, higher concentrations of hydrogen, methane, and light hydrocarbons are detected (Figure 6b,c). Surely, CO2 sorption shifts the chemical equilibrium of the following reactions (7)–(9) towards the reactants by the Le Chatelier principle.

H2 + CO2 ↓ + ↔ CO + H2O

CH4 + CO2 ↓↔ 2CO + 2H2

CnHm + nCO2 ↓↔ 2nCO + m/2 H2

At 600 and 700 °C, the perturbation of the chemical equilibrium by CO2 sorption has lowered the CO molar concentration in the pyrolysis gas under the values detected for the pyrolysis of sole sewage sludge (Figure 6d). At 800 °C, the calcination reaction of CaCO3 starts, and the chemical equilibrium of reaction (6) is more shifted towards the reactants CO2 and CaO. Consequently, at 800 °C, because of Le Chatelier’s principle, a decrease in CH4 and CnHm is stored (reactions (8) and (9)).

Figure 6e shows that when CaO is added to the process, the molar ratio H2/CO increases, and it is 2.1 at 700° C. Once again, the absorption of CO2 by CaO shifts the chemical equilibrium of the water—gas shift reaction (7) toward the production of hydrogen by converting CO and water.

Globally, the pyrolysis of sewage sludge with CaO gives a pyrolysis gas with a low heating value in the range 25–18 MJ/Nm3 at the process temperature of 600–800 °C (Figure 6f), which is higher than the pyrolysis of sole sewage sludge.

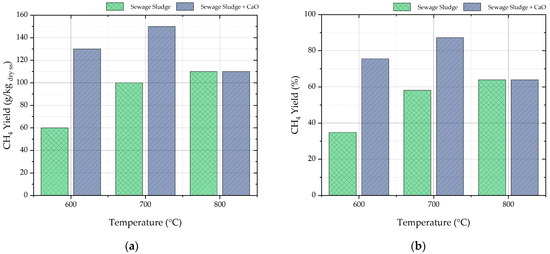

From the ultimate analysis of sewage sludge of Table 3, it can be easily calculated that hydrogen is the limiting element for the methane production, and the maximum theoretical methane yield is 170 g/kg of dry sewage sludge.

Figure 7a shows that methane yield increases with the temperature of sewage sludge pyrolysis. When CaO is added to the process, the methane yield shows a maximum at 700 °C, with a methane yield of 150 g/kg dry sewage sludge. Figure 7b shows the percentage methane yields, calculated as ratio between the methane yield and the maximum theoretical methane yield calculated from ultimate analysis. In the case of pyrolysis of sole sewage sludge, the percentage methane yield ranged from 35 to 64% with increasing temperature. When CaO was added, the maximum percentage methane yield of 87% was detected at 700 °C. This value denotes that the sewage sludge was converted to methane-rich gas with an efficiency close to the ideal. This interesting experimental evidence is strictly related to the CaO capacity to chemisorb CO2 and to the shift in the chemical equilibrium of reactions (8) and (9) toward the reactants. CaO chemisorbs CO2 until the mesoporous structure of CaO is preserved; at higher temperatures (e.g., 800 °C), thermal sintering and pore blockage confine the chemical interaction only to the CaO surface [38]. Furthermore, from a thermodynamic point of view, the higher temperature helps the calcination reaction of CaCO3 that releases CO2.

CaCO3(s) → CaO (s) + CO2 ΔH° = +178.3 kJ mol−1

Figure 7.

Methane yield from sewage sludge pyrolysis expressed as g/kg dry ss (a) and percentage methane yield compared to theoretical yield (b).

The equilibrium of CO2 chemisorption reaction by CaO is related to the CO2 partial pressure and volumetric concentration in the pyrolysis gas. In fact, for reaction (6), keq = 1/pco2. Figure 6a shows that CO2 volumetric percentage in the pyrolysis gas from sewage sludge decreases with increasing temperature, shifting the equilibrium of the reaction (6) towards CaO.

With the goal to increase the methane yield further, catalytic methanation tests of the gas will be planned. Ideal H2/CO molar ratio equal to 3 would satisfy stoichiometric constraint of the methanation reaction:

3H2 + CO ↔ CH4 + H2O

In conclusion, sewage sludge pyrolysis with CaO at 700 °C gives the highest percentage methane yield and the pyrolysis gas with the highest H2/CO molar ratio, as shown in Figure 6e.

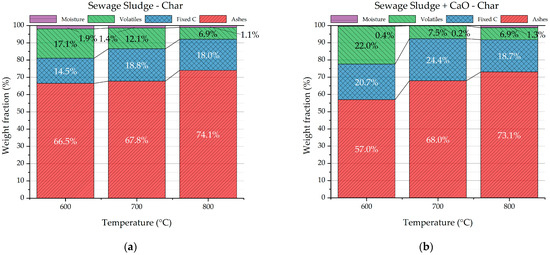

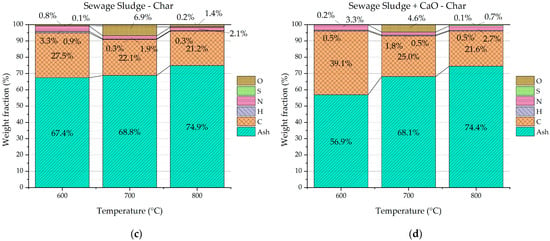

The chars from the pyrolysis tests were analyzed in terms of proximate and ultimate analyses. Similar qualitative trends were observed for proximate and ultimate analyses of chars from both the pyrolysis process of sole sewage sludge and sewage sludge with CaO. Figure 8a,b clearly show that the ash content of char increases with the temperature, while the volatiles and, overall, the organic matter (volatiles + fixed carbon) decrease. Figure 8c,d point out the decreasing elemental carbon with the pyrolysis temperature. The trends observed in Figure 8 can be justified by the higher severity of the pyrolysis process with the increasing temperature. In fact, the higher thermal energy provided to the feedstock degrades the organic matter favoring devolatization of uncondensable gas as well as organic volatile molecules. Consequently, the solid biochar is richer in ash and poorer in organic matter as the pyrolysis temperature increases. The detected trends are in accordance with several scientific studies reported in the literature [39,40]. Temperature emerges as a pivotal parameter that significantly shapes the chemical characteristics of sludge-based biochar.

Figure 8.

Proximate and ultimate analysis of chars from sewage sludge pyrolysis (a,c) and from sewage sludge pyrolysis with CaO (b,d).

The organic fraction of the condensable products obtained from sewage sludge pyrolysis was investigated through GC–MS analysis. The detected compounds were classified by the ECN tar scheme to facilitate the interpretation of the results and of the process. The percentual abundances of the molecular classes identified in the pyrolysis tests are reported in Table 5. The results highlight qualitative similarities with those previously observed in pyrolysis oils derived from digestate, as discussed in earlier work [12]. In both cases, the most abundant species at all operating temperatures belong to class 3, consisting of single-ring aromatic compounds such as toluene, styrene, and 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene. For sludge pyrolysis oils, clear temperature-dependent trends were observed: as the pyrolysis temperature increased, the relative abundance of class 4 molecules decreased, while class 3 molecules became more prominent.

Table 5.

Relative abundance of the major classes of organic compounds of the condensable products derived from sewage sludge pyrolysis (wt. %).

When calcium oxide (CaO) was introduced during pyrolysis, the distribution of organic molecules shifted significantly. GC–MS analysis revealed a more balanced relative weight distribution between class 2 and class 3 compounds. At the same time, a reduction in class 4 molecules was recorded compared with sludge pyrolysis performed without CaO. This behavior can be attributed to the catalytic cracking activity of calcium oxide, which promotes the fragmentation of heavier or more complex organic species and favors the formation of lighter aromatic compounds.

Overall, the GC–MS characterization confirms that pyrolysis conditions, particularly temperature and the presence of CaO, strongly influence the molecular profile of condensable products, shaping both the qualitative and quantitative distribution of organic classes.

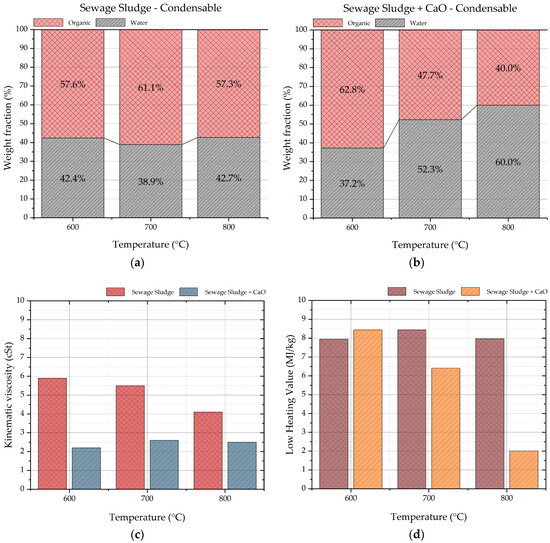

The condensable pyrolysis product was characterized in its water content, cinematic viscosity, and heating value. As written above, it was very heterogeneous, and a representative sample was obtained after a vigorous shaking of the product.

Figure 9a,b show the water content of condensable products derived from sole sewage sludge and from sewage sludge plus CaO pyrolysis, respectively. Figure 9b shows a clear increasing trend of water content and decreasing trend of organic content with the temperature that speeds up the kinetic rates of reforming and cracking reactions of organic molecules. Moreover, at 700 and 800 °C, the organic content is lower in the case of sewage sludge pyrolysis with CaO (48 and 40 wt.%) compared to sewage sludge pyrolysis (61 and 57 wt.%). These value and the condensable product yield of Figure 2a,b underlines CaO activity as a catalyst in cracking and reforming reactions of organic molecules to smaller incondensable ones.

Figure 9.

Water and organic content (a,b), kinematic viscosity (c) and heating value of condensable products (d).

The kinematic viscosity of condensable products ranges from 6 to 2 cSt; the higher values were detected for condensable products obtained from pyrolysis of sole sewage sludge (Figure 9c). Probably, this is linked to less amount of water in these products.

The low heating value ranges from 8.4 to 2 MJ/kg (Figure 9d), assessing the condensable product as bad combustible, also considering their heterogeneous nature, chemical reactivity, and their chemical-physical instability in the time [41,42].

4. Conclusions

Global population growth and the always more stringent regulations regarding waste disposal are driving the civil administrations to establish proper sewage sludge disposal plans tailored to the social environmental context. Virtuous management of sewage sludge, such as spreading in land as fertilizer, composting, and thermal treatments for energy recovery, are slowly taking the place of landfill disposal. The main finding of the present scientific paper is that dry sewage sludge pyrolysis with CaO addition was assessed as a robust technology to recover methane-rich syngas by a bench-scale continuous rotary kiln. The best result was obtained when sewage sludge was pyrolyzed with CaO at 700 °C. A gas with a CH4 and light hydrocarbons content of 40 mol % was obtained with a percentage methane yield of 87%. CO2 content was very low (2 mol %) because CaO worked as CO2 sorbent. Moreover, considering the reduction in condensable products by CaO addition, CaO presumably worked as a catalyst of chemical conversion reactions of organic vapors. The H2/CO molar ratio of the gas was the highest, i.e., 2.1, so that, after H2 enrichment, it could be exploited for further methanation. The gas yield was 37 wt.%; therefore, exploitation of the byproducts of the process would strengthen the economic feasibility of the process at industrial scale. In this regard, the condensable product could be burnt for energy recovery inside of the process, while the exhaust sorbent/catalyst detained in the char could be regenerated in a calcinatory providing thermal energy. The make-up of fresh sorbent should be evaluated as function of sorbent comminution, elutriation in the plant, and the loss of activity of the regenerated sorbent. In the future, experimental activities about the cyclic regeneration of the exhaust sorbent and about sludges of different provenience will be scheduled to improve and consolidate the process principles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.F., C.F., A.L.P. and M.S.; methodology, C.F.; validation, E.F. and C.F.; formal analysis, C.F.; investigation, E.F. and C.F.; resources, C.F., V.V. and A.R.; data curation, E.F. and C.F.; writing—original draft preparation, E.F.; writing—review and editing, E.F., C.F., A.L.P., A.R. and V.V.; visualization, E.F.; supervision, G.C.; project administration, E.F. and G.B.; funding acquisition, G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MUR—Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca—PON “Ricerca e Innovazione” 2014–2020 (MUR n. 1735, 13 July 2017), grant number MUR 0001867, 22 July 2021—Wet Waste to Green Fuel (ARS01_00868, WWGF Project): Gassificazione rifiuti organici umidi con acqua supercritica per produzione di biometano—GNL.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Adolfo Le Pera and Miriam Sellaro were employed by Calabra Maceri e Servizi s.p.a. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SS | Sewage sludge |

| TRL | Technological readiness level |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| FTIR-DSC | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy-Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

References

- ISPRA. Rapporto Rifiuti Speciali N° 402; ISPRA: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kominko, H.; Gorazda, K.; Wzorek, Z. Sewage Sludge: A Review of Its Risks and Circular Raw Material Potential. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 63, 105522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijo, B.; Nobre, C.; Brito, P.; Ferreira, P. An Overview of the Thermochemical Valorization of Sewage Sludge: Principles and Current Challenges. Energies 2024, 17, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Wang, S.; Xu, D.; Guo, Y.; Tang, X.; Wang, L. Treatment of Municipal Sewage Sludge in Supercritical Water: A Review. Water Res. 2016, 89, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freda, C.; Cornacchia, G.; Romanelli, A.; Valerio, V.; Grieco, M. Sewage Sludge Gasification in a Bench Scale Rotary Kiln. Fuel 2018, 212, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaoka, M.; Yoo, J.; Mizuno, T.; Sonoda, K.; Ueda, A.; Hosho, F.; Miyamoto, T. Historical Trends, Roles, and Future Challenges of Sewage Sludge Thermal Treatment in Japan. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2025, 27, 2811–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, A.; Freda, C.; Catizzone, E. Techno-Economic Assessment of Bio-Syngas Production for Methanol Synthesis: A Focus on the Water–Gas Shift and Carbon Capture Sections. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdziarz, A.; Wilk, M. Thermal Characteristics of the Combustion Process of Biomass and Sewage Sludge. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2013, 114, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porshnov, D. Evolution of Pyrolysis and Gasification as Waste to Energy Tools for Low Carbon Economy. WIREs Energy Environ. 2022, 11, e421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Kamran, K.; Quan, C.; Williams, P.T. Thermochemical Conversion of Sewage Sludge: A Critical Review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2020, 79, 100843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherghel, A.; Teodosiu, C.; De Gisi, S. A Review on Wastewater Sludge Valorisation and Its Challenges in the Context of Circular Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, E.; Freda, C.; Romanelli, A.; Valerio, V.; Le Pera, A.; Sellaro, M.; Cornacchia, G.; Braccio, G. Thermochemical Conversion of Digestate Derived from OFMSW Anaerobic Digestion to Produce Methane-Rich Syngas with CO2 Sorption. Processes 2025, 13, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, C.Z.; Pal, K.; Yehye, W.A.; Sagadevan, S.; Shah, S.T.; Adebisi, G.A. Pyrolysis: A Sustainable Way to Generate Energy from Waste; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, D.A.; Brown, R.C.; Amonette, J.E.; Lehmann, J. Review of the pyrolysis platform for coproducing bio-oil and biochar. Biofuel Bioprod. Biorefin. 2009, 3, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahnila, M.; Koskela, A.; Sulasalmi, P.; Fabritius, T. A Review of Pyrolysis Technologies and the Effect of Process Parameters on Biocarbon Properties. Energies 2023, 16, 6936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rumaihi, A.; Shahbaz, M.; Mckay, G.; Mackey, H.; Al-Ansari, T. A review of pyrolysis technologies and feedstock: A blending approach for plastic and biomass towards optimum biochar yield. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; Shen, J.; Yang, Y. Sewage Sludge Separate Pyrolysis and Co-Pyrolysis with Low Rank Coal: Characteristics, Kinetics, and Mechanism. Thermochim. Acta 2025, 753, 180110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Li, J.; Qi, B.; Li, A.; Duan, Y.; Wang, Z. Thermal Analysis and Products Distribution of Dried Sewage Sludge Pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2014, 105, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascó, G.; Blanco, C.G.; Guerrero, F.; Méndez Lázaro, A.M. The Influence of Organic Matter on Sewage Sludge Pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2005, 74, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Xiong, X.; Che, D.; Liu, H.; Sun, B. Effects of Sludge Pyrolysis Temperature and Atmosphere on Characteristics of Biochar and Gaseous Products. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 38, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrafioti, E.; Bouras, G.; Kalderis, D.; Diamadopoulos, E. Biochar Production by Sewage Sludge Pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2013, 101, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, D.; Barbiero, C.; Briens, C.; Berruti, F. Pyrolysis as an Economical and Ecological Treatment Option for Municipal Sewage Sludge. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 122, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanmohammadi, Z.; Afyuni, M.; Mosaddeghi, M.R. Effect of Pyrolysis Temperature on Chemical and Physical Properties of Sewage Sludge Biochar. Waste Manage. Res. 2015, 33, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroza, M.M.; Sousa, J.F.; Vieira, G.E.G.; Bezerra, M.B.D. Characterization of the Products from the Pyrolysis of Sewage Sludge in 1 Kg/h Rotating Cylinder Reactor. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2014, 105, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhong, Z.; Du, H.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, B.; Jin, B. Co-Pyrolysis of Sludge and Kaolin/Zeolite in a Rotary Kiln: Analysis of Stabilizing Heavy Metals. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2022, 16, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhao, Z.; Soomro, A.; Ma, S.; Wu, M.; Sun, Z.; Xiang, W. Hydrogen-Rich Syngas Production via Sorption-Enhanced Steam Gasification of Sewage Sludge. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 138, 105607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, T.N.; Jensen, P.A.; Dam-Johansen, K.; Knudsen, N.O.; Sørensen, H.R. Influence of the Pyrolysis Temperature on Sewage Sludge Product Distribution, Bio-Oil, and Char Properties. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2216; Standard Test Methods for Laboratory Determination of Water (Moisture) Content of Soil and Rock by Mass. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D1762-84; Standard Test Method for Chemical Analysis of Wood Charcoal. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D5373-21; Standard Test Methods for Determination of Carbon, Hydrogen and Nitrogen in Analysis Samples of Coal and Carbon in Analysis Samples of Coal and Coke. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D5865/D5865M-19; Standard Test Method for Gross Calorific Value of Coal and Coke. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019. [CrossRef]

- ASTM E203-16; Standard Test Method for Water Using Volumetric Karl Fischer Titration. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D445-24; Standard Test Method for Kinematic Viscosity of Transparent and Opaque Liquids (and Calculation of Dynamic Viscosity). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.D.; Maier, C.G.; Ralston, O.C. Passage of Solid Particles Through Rotary Cylindrical Kilns. US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Corella, J.; Aznar, M.-P.; Gil, J.; Caballero, M.A. Biomass Gasification in Fluidized Bed: Where to Locate the Dolomite To Improve Gasification? Energy Fuels 1999, 13, 1122–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Magoua Mbeugang, C.F.; Huang, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, S. A Review of CaO Based Catalysts for Tar Removal during Biomass Gasification. Energy 2022, 244, 123172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Xiao, B.; Liu, S.; Guo, X.; Luo, S.; Xu, Z.; Feng, Y.; Hu, Z. Hydrogen-Rich Gas from Catalytic Steam Gasification of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW): Influence of Steam to MSW Ratios and Weight Hourly Space Velocity on Gas Production and Composition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 2174–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Fang, J.; Han, Z.; Chen, P.; Xu, X.; Liao, J. Optimizing CaO-based CO2 adsorption: Impact of operating parameters. iScience 2025, 34, 113127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.K.; Strezov, V.; Chan, K.Y.; Ziolkowski, A.; Nelson, P.F. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on production and nutrient properties of wastewater sludge biochar. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Sheng, Q.; Dai, X.; Dong, B. Upgrading of sewage sludge by low temperature pyrolysis: Biochar fuel properties and combustion behavior. Fuel 2021, 300, 121007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanovic, M. Some Remarks on the Viscosity Measurement of Pyrolysis Liquids. Biomass Bioenergy 2000, 18, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordella, M.; Berrueco, C.; Santarelli, F.; Paterson, N.; Kandiyoti, R.; Millan, M. Yields and Ageing of the Liquids Obtained by Slow Pyrolysis of Sorghum, Switchgrass and Corn Stalks. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2013, 104, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.