Abstract

The untreated discharge of dairy industry wastewater, characterized by high organic and nutrient loads, poses a severe eutrophication threat, leading to oxygen depletion and the disruption of aquatic ecosystems, which necessitates advanced treatment strategies. Anaerobic digestion (AD) represents an effective and sustainable alternative, converting organic matter into biogas while minimizing sludge production and contributing to Circular Economy strategies. This study investigated the effects of fat concentration and operational temperature on the anaerobic digestion of dairy effluents. Three types of effluents, skimmed, semi-skimmed, and whole substrates, were evaluated under mesophilic 35 °C and thermophilic 55 °C conditions to degrade substrates with different fat content. Low-fat effluents exhibited higher COD removal, shorter lag phases, and stable activity under mesophilic conditions, while high-fat substrates delayed start-up due to accumulation of fatty acids and brief methanogen inhibition. Thermophilic digestion accelerated hydrolysis and methane production but demonstrated increased sensitivity to lipid-induced inhibition. Kinetic modeling confirmed that the modified Gompertz model accurately described mesophilic digestion with rapid microbial adaptation, while the Cone model better captured thermophilic, hydrolysis-limited kinetics. The thermophilic operation significantly enhanced methane productivity, yielding 105–191 mL CH4 g−1VS compared to 54–70 mL CH4 g−1VS under mesophilic conditions by increasing apparent hydrolysis rates and reducing lag phases. However, the mesophilic process demonstrated superior operational stability and robustness during start-up with fat-rich effluents, which otherwise suffered delayed methane formation due to lipid hydrolysis and volatile fatty acid (VFA) inhibition. Overall, the synergistic interaction between temperature and fat concentration revealed a trade-off between methane productivity and process stability, with thermophilic digestion increasing methane yields up to 191 mL CH4 g−1 VS but reducing COD removal and robustness during start-up, whereas mesophilic operation ensured more stable performance despite lower methane yields.

1. Introduction

The dairy industry is a main provider to global food production, but, also, this industry generates wastewater and by-products with high organic load and nutrient content. These effluents originate from processes such as milk reception, pasteurization, cheese and butter production, and equipment cleaning. The effluents are typically characterized by elevated concentrations of chemical oxygen demand (COD), proteins, carbohydrates (mainly lactose), and lipids (FOG—fats, oils, and grease) [1,2]. Lipid content in dairy wastewater can range from less than 0.3 g L−1 to more than 40 g L−1 depending on the process and cleaning operations [3]. The elevated lipid concentration, in fact, serves as a critical physicochemical parameter distinguishing them from other industrial wastewater streams. Thus, compared with carbohydrate-rich fruit-processing streams or the variable fat content of meat-processing wastewater, dairy effluents consistently exhibit elevated and chemically stable lipid concentrations that substantially increase COD, challenge conventional aerobic treatment, and necessitate advanced approaches such as anaerobic digestion to mitigate environmental impacts.

If not properly treated, these lipid-rich wastewater can cause severe environmental problems, including eutrophication, oxygen depletion, clogging of pipelines, foam formation, and the emission of greenhouse gases during uncontrolled degradation [4]. Additionally, the high organic strength of dairy wastewater increases treatment costs and challenges for conventional aerobic systems, which are often energy-intensive and produce large amounts of sludge [5]. On the other hand, the dairy industry contributes significantly to climate change, largely through the emission of powerful greenhouse gases like methane (from enteric fermentation, i.e., cow burps) and nitrous oxide (from manure management and fertilizer use for feed crops).

Nevertheless, despite their high energetic potential and contribution to Circular Economy and Zero Waste strategies, the management of dairy wastewater through anaerobic digestion systems remains particularly demanding from an operational standpoint. Anaerobic digestion (AD) is promoted as an environmental technology widely employed for the treatment of high-strength organic industrial effluents, including those derived from the dairy industry. AD is a well-established biotechnological process that converts organic matter into biogas—a mixture primarily composed of CH4 and CO2—and a nutrient-rich digestate under oxygen-free conditions. Through four main stages, hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis, complex organic compounds are progressively degraded by specialized microbial consortia [6]. AD offers several advantages over aerobic treatment: lower sludge production, energy recovery in the form of biogas, and reduced operational costs [7]. The specific characteristics of lipids in dairy wastewater are paramount to system stability. Lipids are hydrolysed into long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) and volatile fatty acids (VFA), which are powerful precursors to methane. However, if these intermediates accumulate in the systems, they can lead to inhibitory effects, mainly on methanogenic archaea. The degradation of LCFAs is rate-limiting and often temperature-dependent, making AD performance highly sensitive to both the quantity and composition of fats present in the feedstock [8]. The milk fats could be highly inhibitory and significantly prolong the start-up lag phase, depending on temperature. To mitigate this inhibitory effect and ensure effective start-up, studies recommend maintaining milk fat concentrations below 100 mg/L [9].

Despite the inherent inhibitory nature of LCFA, systems can tolerate remarkably high concentrations under optimized operational and design conditions. Anaerobic digestion start-up has been successfully optimized at moderate temperatures (15–20 °C) when treating wastewater rich in LCFA, specifically when LCFA concentrations constitute 33–45% of the influent COD [10,11]. The stable operation, characterized by high COD removal (88–98%), was achieved in eight days approximately at 20 °C even with a high organic loading rate: 1333 mg COD-LCFA/L⋅d [11].

Temperature is equally critical, governing microbial kinetics, community composition, and overall time required for reactor stabilization. The operational temperature range spans psychrophilic (≤20 °C), mesophilic (21–40 °C), and thermophilic (>40 °C) conditions. At the upper end, thermophilic optimal conditions—around 55 °C—offer the fastest path to stable operation, significantly reducing the lag phase to less than one day and initiating rapid biogas production [12]. On the other hand, under mesophilic optimal conditions—around 55 °C—anaerobic digestion exhibits stable microbial activity with efficient degradation of organic matter, leading to consistent biogas yields and balanced process performance [13].

However, mesophilic systems often display a longer lag phase compared to thermophilic digestion, as the lower temperature reduces hydrolysis and methanogenic kinetics, resulting in slower system acclimation and methane onset [14,15].

In this context, the acclimation of inoculum is crucial for fostering specialized microbial populations capable of metabolizing fat substrates efficiently in cold environments. In terms of overall performance metrics during the start-up period, the literature indicates high soluble COD removal (>90% at 15 °C and high LCFA removal) [16], and 84–91% soluble COD removal under high LCFA loading at 20 °C [10,11]. However, the biogas output during the initial start-up phase may remain low, such as methane yield efficiency of only 5–9% in the first eight days, reflecting the energy required for biomass growth and stabilization [11].

The objective of this research was to evaluate the effect of fat concentration in dairy waste on the performance process of anaerobic digestion under two distinct temperature ranges. Three types of effluents with different fat contents were tested—skimmed, semi-skimmed, and whole substrates wastewaters—to represent realistic variations in lipid load. Additionally, the impact of operational temperature on the performance was analyzed by comparing mesophilic (35 °C) and thermophilic (55 °C) conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inoculum and Dairy Effluents

To investigate the anaerobic degradation of milk fat, synthetic wastewater was formulated using commercial milk products with controlled and well-defined compositions. Three substrates from the same brand (Pingo Doce, Lisbon-Portugal) were selected to represent different lipid contents: Skimmed milk (SM), Semi-skimmed milk (SSM), and Whole milk (WM). The synthetic wastewater was used since real industrial dairy effluents exhibit temporal variability, particularly concerning lipid fractionation and the presence of detergents or cleaning agents. By utilizing synthetic substrates prepared from commercial milk, the initial fat concentration and overall organic load is under control to study the hydrolysis and methanogenesis performance. The inoculum used for the anaerobic digestion assays consisted of granular sludge obtained from an industrial full-scale reactor operating under mesophilic conditions (35 ± 1 °C). Specifically, the sludge was provided by the company Lactimonte, located in Estremadura, Portugal based on a fluidized bed anaerobic reactor operating under steady-state conditions with a Hydraulic Retention Time (HRT) of approximately 6 h, with an organic matter removal efficiency of 90%. Inoculum acclimation was conducted in a two-stage process. First, thermal adaptation was achieved through a gradual, stepwise temperature increase over a one-week period, with continuous pH monitoring to mitigate potential system inhibition. Second, the thermally acclimated inoculum was selectively enriched by feeding it a diluted semi-skimmed dairy effluent for an additional week. This procedure ensured microbial adaptation and stable functionality prior to the main experimental phase.

2.2. Analytical Methods

The physicochemical characterization of the inoculum and synthetic milk wastewater was performed according to the Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater [17]. The following parameters were quantified: chemical oxygen demand (COD), pH, total solids (TS), volatile solids (VS), total suspended solids (TSS), volatile suspended solids (VSS), carbohydrates, proteins, and volatile fatty acids (VFA). Lipids were determined by liquid–liquid extraction followed by gravimetric quantification. Protein concentrations were measured using the Kjeldahl method, with total nitrogen converted to protein using a standard conversion factor of 6.25. Finally, carbohydrates were quantified using the phenol–sulfuric acid assay with glucose as the calibration standard. All analyses were carried out at the beginning and at the end of each experimental run to determine substrate degradation efficiency and to quantify the removal of organic matter. The VFA analysis was based on the concentrations of acetic, propionic, butyric, isobutyric, valeric, and isovaleric using a Hewlett Packard 5890 gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID). The total VFA was expressed as Acetic Acid equivalent in mg/L. Biogas samples were analyzed for quantitative composition using a Varian 3380 GC equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and two columns: Porapak S and a molecular sieve. Helium was used as the carrier gas, and the method utilized an external standard for quantification.

2.3. Equipment and Experimental Conditions

The stirred anaerobic reactors were configured based on Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) tests, following the inoculum and substrate concentration recommendations of [18]. This configuration was used to assess how fat concentration and temperature affect the start-up of the anaerobic digestion process. To prevent system inhibition from the accumulation of volatile fatty acids (VFA), the assays were conducted with an organic loading of 1 g COD/L (chemical oxygen demand). In fact, the study focused on volatile fatty acid (VFA) dynamics as key indicators of lipid degradation and potential process imbalance. The BMP tests were performed under wet anaerobic conditions: 4 total solids, TS.

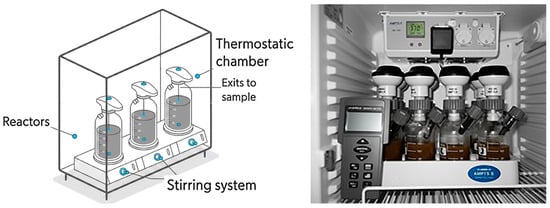

A total of twelve reactors with a total volume of 500 mL and a working volume of 250 mL were used. The reactors were equipped with pressure transducers (OxiTop WTW) and placed in thermostatic chambers to maintain either mesophilic (35 °C) and thermophilic (55 °C) conditions (Figure 1). Mixing was supported by magnetic stirring. Prior to inoculation, the granular sludge was processed to obtain a suspended microbial culture: the inoculum was first centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min to remove excess organic matter, and the supernatant was subsequently centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 5 min. The resulting pellet was resuspended in the reactor medium. The inoculum-to-reactor volume ratio was 10% (v/v), and the organic loading rate (OLR) was set at 1 g COD L−1 for all synthetic wastewaters: skimmed, semi-skimmed, and whole. Each condition was tested in triplicate. Additionally, a blank, only containing the inoculum and tap water, was tested in triplicate for each temperature. Before incubation, the headspace was purged with nitrogen gas to ensure anaerobic conditions. The experiments were conducted for 30 days to monitor performance and biogas accumulation in the stable phase.

Figure 1.

BMP experimental setup based on OxiTop WTW: schematic and photograph.

2.4. Kinetic Analysis and Modeling

The effects of temperature and substrate type on the anaerobic digestion performance were statistically analyzed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. Additionally, for the kinetic analysis of the experimental data, three models were selected: the first-order kinetic model, the Cone model, and the modified Gompertz model. The modified Gompertz model (Equation (1)) was chosen as the primary kinetic tool due to its established empirical strength in describing the dynamics of anaerobic digestion and its direct correlation with microbial growth phases. The first-order (Equation (2)) and Cone (Equation (3)) models were also applied as complementary tools.

where

H represents the cumulative methane production over time (t) (mL/gVS),

P denotes the potential for maximum methane production (mL/gVS),

Rm is the methane production rate (mL of methane/gVS day),

λ refers to the lag phase duration before significant methane generation begins (days),

t is the time associated with the cumulative methane production (H),

n indicates the deviations between experimental and predicted methane production values,

represents the apparent hydrolysis rate constant (day−1).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the Inoculum and Effluents

The physicochemical characterization of the inoculum and synthetic dairy wastewaters is summarized in Table 1. The granular inoculum exhibited a total solids (TS) content of approximately 14%, with volatile solids (VS) accounting for about 6%, representing nearly 43% of the total organic matter. These values indicate a well-stabilized, high-activity sludge suitable for use as inoculum in anaerobic digestion assays.

Table 1.

Characterization of effluents and inoculum used in the study.

Regarding the synthetic dairy wastewaters, clear differences were observed among the three types, primarily associated with their fat content. The lipid concentration varied significantly, from 36 ± 2 g L−1 in whole substrates, to 16 ± 1 g L−1 in semi-skimmed substrates, and less than 1 g L−1 in skimmed substrates, corresponding closely with their saturated fatty acid contents (25 ± 2, 10 ± 1, and <1 g L−1, respectively). As expected, the COD of the effluents followed the same trend, being largely determined by the lipid fraction: 190.98 ± 1.92 g L−1 for whole substrates, 129.51 ± 2.32 g L−1 for semi-skimmed substrates, and 105.74 ± 1.36 g L−1 for skimmed substrates.

In contrast, the carbohydrate and protein contents were relatively consistent in the substrates, averaging approximately 48–49 g L−1 and 32 g L−1, respectively. This homogeneity indicates that the primary compositional variation among the effluents is indeed due to their fat content rather than differences in other macronutrients.

The total suspended solids (TSS) and volatile suspended solids (VSS) also reflected the lipid content of each effluent. Whole substrates presented the highest TSS (5.40 ± 0.28 g L−1) and VSS (5.05 ± 0.45 g L−1), followed by semi-skimmed substrates (4.13 ± 0.33 g L−1 TSS; 4.03 ± 0.19 g L−1 VSS) and skimmed substrates (1.73 ± 0.72 g L−1 TSS; 1.63 ± 0.69 g L−1 VSS). In all cases, the volatile fraction accounted for approximately 95% of total suspended solids, consistent with the high biodegradability of dairy-based substrates.

3.2. Anaerobic Digestion of Synthetic Dairy Wastewaters in Mesophilic (35 °C)

The initial and final characteristics of the mesophilic reactors are shown in Table 2. As indicated, at start-up the reactors were loaded with 1 g COD L−1, and approximately 65% of the total COD was in the soluble fraction (CODs), indicating that more than half of the organic load is assimilable by the microbial community.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the initial and final effluent in mesophilic (35 °C) and thermophilic reactors (55 °C).

The pH dropped from 7.6 at start-up to values ranging from 6.62 (skimmed-milk effluent) up to 6.91 (whole-milk effluent) at the end of the 30 day experimental period mesophilic reactors. This pH decline reflects the onset of hydrolysis and acidogenesis, with accumulation of acids typical of early anaerobic stages. The more pronounced pH drop in the skimmed-milk effluent may indicate a faster acid accumulation rate relative to buffering capacity. In fact, the higher final pH recorded in the whole-milk substrate treatment indicates an enhanced buffering capacity, probably resulting from the increased lipid fraction, which may contribute to acid adsorption or stabilization within the system [4,19]. Total COD (CODt) values at the start were 1.09 g L−1 for whole-milk substrates, 1.66 g L−1 for semi-skimmed, and 1.17 g L−1 for skimmed. After the 30 days, CODt decreased modestly (to 0.91 g L−1 for whole substrates, 1.38 g L−1 for semi-skimmed, and 0.95 g L−1 for skimmed). Soluble COD (CODs) also dropped, indicating consumption of the readily available organic fraction. However, the extent of COD removal was clearly limited; the highest COD removal in mesophilic mode was observed for the skimmed-milk effluent 18.42%, compared to 16.13% for the whole-milk effluent.

In most cases VSS (expressed as % or g/L) increased slightly, reflecting microbial growth. For example, TSS and VSS increased from 0.24% to 0.35% in the whole-milk test. This suggests that although substrate conversion was limited, biomass generation did occur during the acidogenic phase [20].

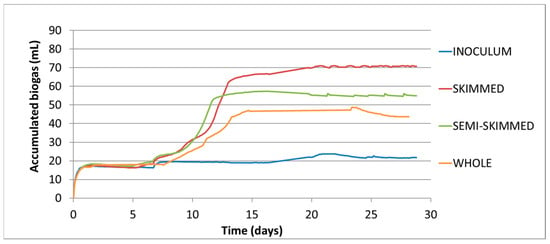

Related to biogas, the reactors were tested continuously for a fixed time of 30 days. Figure 2 shows the development of the biogas produced in the mesophilic systems. The arithmetic mean of the three replicates tested for each condition is shown. A differentiated generation of biogas, depending on the substrate composition, is observed in study. Thus, the skimmed effluent reached a production of biogas accumulates of 72 mL, followed by semi-skimmed with an accumulation of 55 mL, and finally the whole effluent with an accumulation of 44 mL. In this line, it shows that the increase in acidity in the system with lower fat content was higher than in the system with higher fat content, 38.89% from the 35.48%.

Figure 2.

Evolution of the biogas production during the mesophilic anaerobic digestion of synthetic dairy wastewaters: whole, semi-skimmed and skimmed, and the mesophilic inoculum employed.

3.3. Anaerobic Digestion of Synthetic Dairy Wastewaters in Thermophilic (55 °C)

Table 2 presents the initial and final data for the thermophilic reactors. Like the mesophilic tests, the initial reactor charge was 1 g COD L−1, with CODs again roughly 60–65% of total COD, indicating a major fraction of readily available organics substrates for the microorganisms.

Contrary to the expectation of consistent acidification, the thermophilic reactors exhibited a final pH of 7.58 for the blank control, but much lower values in the whole-milk, semi-skimmed, and skimmed effluents (6.98, 6.76, 6.53, respectively). These low pH values indicate acidification, likely due to the increased hydrolysis rate at 55 °C but insufficient downstream consumption of acids, what lead to the VFA accumulation.

CODt values at the start were 1.51–1.54 g L−1 for the fat-containing effluents. After the test period, CODt were reported: 1.45 g L−1 for whole-milk, 1.42 g L−1 for semi-skimmed, and 1.38 g L−1 for skimmed synthetic effluents, implying low COD removal in thermophilic conditions, much lower than under mesophilic conditions.

TSS and VSS remained low (<0.25% in most cases) and in some cases decreased slightly, suggesting that microbial growth was limited or that biomass washout or cell lysis may have occurred due to inhibitory conditions, such as low pH and VFA accumulation [19,21].

In this study, the fact that COD removal was lower in the thermophilic mode than in the mesophilic mode suggests that the system could not cope with the high lipid content at 55 °C within the 30-day test period. The more severe acidification and low pH values indicate that acidogenesis outpaced acetogenesis/methanogenesis, likely due to VFA inhibition or metabolic imbalance.

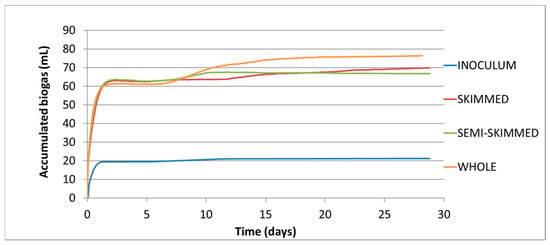

On the other hand, related to biogas production, Figure 3 represents its evolution in thermophilic reactors. As mentioned above, each line represents the arithmetic mean of the three replicates tested for each condition. It shows how the generation of biogas is almost immediate upon contact between the inoculum and organic matter; the exponential phase of biogas generation occurs during the first hours of operation, so the lag phase is short. The accumulated biogas is quite similar among all the treated effluent, with no clear differences as in the mesophilic treatment difference, although there are certain differences. In this case, the reactors with lower fat content have a similar accumulation with 68–70 mL and the system effluent enriched with fat content reaches 77 mL of accumulate biogas.

Figure 3.

Evolution of biogas production during the thermophilic anaerobic digestion of synthetic dairy wastewaters: whole, semi-skimmed, and skimmed; and the thermophilic inoculum employed.

3.4. Performance of AD of Synthetic Dairy Wastewater in Mesophilic (35 °C) and Thermophilic (55 °C)

The results presented in Table 3 highlight the influence of temperature regime and substrate composition, based on fat concentration, on the overall performance of anaerobic digestion (AD) of synthetic dairy wastewater. Both mesophilic (35 °C) and thermophilic (55 °C) conditions showed marked differences in degradation efficiency, organic matter removal, and stability. Positive values indicate net parameter removal, whereas negative values signify a net accumulation or increase relative to the initial concentration, often suggesting poor performance or the release of intermediate compounds.

Table 3.

Overall removal efficiency (%) of key parameters for mesophilic and thermophilic anaerobic digestion.

In mesophilic, the reduction in total and soluble chemical oxygen demand (CODt and CODs) was moderate (16.5–18.8% and 45.5–56.2%, respectively), suggesting partial substrate conversion and accumulation of intermediate metabolites. The decrease in total and volatile suspended solids (TSS and VSS) was more pronounced in semi-skimmed substrates (−84.8% and −78.8%), indicating an efficient conversion of organic solids into biogas precursors. On the other hand, the accumulation of volatile fatty acids (VFA) was highest in skimmed substrates, 34.8%, consistent with enhanced hydrolytic and acidogenic activity under lower lipid-content availability. The anaerobic degradation of lipids proceeds through hydrolysis of triglycerides to glycerol and long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) [10], followed by syntrophic β-oxidation of LCFAs into acetate, hydrogen, and formate. These intermediates are subsequently converted to methane by acetoclastic and hydrogenotrophic methanogens. However, LCFAs are known to exert inhibitory effects by adsorbing onto microbial cell membranes and interfering with mass transfer processes [10].

In contrast, thermophilic digestion resulted in more pronounced organic matter degradation, particularly for lipid-rich substrates. The CODt and CODs removals were generally lower (4–7.8% and 13.6–23%) compared to mesophilic operation, likely due to increased solubilization but incomplete conversion of organics at elevated temperatures [22]. However, the lipid degradation reached values up to 79.7%, demonstrating the enhanced lipolytic activity of thermophilic consortia, which has been reported to accelerate fatty acid hydrolysis. The higher removal efficiencies of carbohydrates (91.9–92.9%) and proteins (84.8–87.0%) under thermophilic conditions confirm improved enzymatic performance and solubilization rates [23].

Despite these benefits, some instability was observed in TSS and VSS reductions, suggesting possible biomass washout under thermophilic operation. This agrees with previous reports that emphasize the trade-off between higher metabolic rates and process stability in thermophilic digesters [24].

Overall, the thermophilic process exhibited superior degradation of lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins, while the mesophilic process maintained better COD removal and pH stability, particularly in low-fat substrates. These findings indicate that substrate composition strongly modulates the microbial activity balance between hydrolysis, acidogenesis, and methanogenesis, aligning with previous observations in mixed-dairy wastewater digestion [25,26].

The high methane content observed in the final biogas (79–82%) is consistent with the elevated lipid content of the substrates, as lipid-rich wastes are well known to produce biogas with disproportionately high methane fractions. This behavior reflects the inherently higher theoretical methane potential of lipids relative to carbohydrates and proteins, resulting in a higher-quality biogas characterized by an increased CH4/CO2 ratio. Controlled Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) assays containing substantial fat, oil, and grease (FOG) fractions frequently report methane contents between 75% and 85%—a trend repeatedly documented in comprehensive experimental studies involving lipid-rich substrates [27]. In this way, ref. [4] demonstrated exceptionally high methane recoveries, exceeding 93%, in batch assays using a lipid-rich model substrate (triolein) once the initial adaptation phase was overcome. Thus, the elevated methane fractions reported in this study are fully aligned with the established stoichiometric advantages and energetic efficiency associated with the anaerobic degradation of highly reduced, lipid-dominated organic matter. Related to the biogas and methane yield in mesophilic and thermophilic reactors, the data in Table 4 show a clear influence of both temperature and lipid content on methane productivity during anaerobic digestion of dairy substrates. Under mesophilic conditions, skimmed substrates produced the highest methane yield: 70.2 mL CH4 g−1 VS; followed by whole: 60.1; and semi-skimmed substrates: 54.0 mL CH4 g−1 VS. When operating under thermophilic conditions, methane yields increased markedly for all substrates, reaching 191.3 mL CH4 g−1 VS for skimmed substrates, 120.9 mL CH4 g−1 VS for semi-skimmed, and 105.8 mL CH4 g−1 VS for whole substrates. This enhancement in methane productivity at higher temperatures is consistent with previous reports indicating that thermophilic digestion promotes faster hydrolysis, improved solubilization of organics, and enhanced methanogenic activity compared with mesophilic systems [14,15].

Table 4.

Methane productivity according to temperature and concentration in lipids.

Interestingly, the increase in methane yield was inversely correlated with the VS concentration added, particularly under thermophilic conditions. The highest specific yield (191.3 mL CH4 g−1 VS) corresponded to the lowest VS loading (1.2 g L−1), suggesting that lower organic loads favor microbial efficiency by reducing potential inhibition. High lipid concentrations are known to generate fatty acids that can adsorb onto microbial surfaces and inhibit methanogenesis [28]. Therefore, the lower lipid content of skimmed substrates may have mitigated such inhibitory effects, explaining its superior performance relative to semi-skimmed and whole substrates. These findings align with previous results showing that lipid-rich substrates can provide high theoretical methane potential but often suffer from reduced biodegradability and process instability when the lipid fraction is excessive [4].

3.5. Statistical Influence of Temperature and Fat Content

A one-way ANOVA was performed to evaluate whether methane yield differed significantly between mesophilic and thermophilic conditions (Table 5). The analysis revealed a strong effect of temperature (F = 8.47), with thermophilic digestion producing substantially higher methane yields (mean = 139.3 mL CH4 g−1 VS) compared with mesophilic digestion (mean = 61.4 mL CH4 g−1 VS). So, significant differences were observed between mesophilic and thermophilic conditions for all substrates. This result indicates that temperature is a major determinant of methane productivity under the tested conditions.

Table 5.

ANOVA statistical analysis.

On the other hand, a two-way ANOVA was also applied to explore the relative contributions of temperature and substrate type (skimmed, semi-skimmed, whole) to methane yield. Both factors explained a substantial proportion of the total variability, with temperature accounting for the largest share of the sum of squares (SS = 9102.6), followed by substrate type (SS = 2786.7). Although the lack of replication prevents a formal statistical test of the interaction term, the interaction sums of squares (SS = 1512.0) and the interaction plot suggest a differential response of substrates to temperature. Skimmed substrate exhibited the largest increase in methane yield under thermophilic conditions. Thermophilic operation resulted in a statistically significant increase in methane yield (p < 0.05), with average values more than doubling those obtained under mesophilic conditions (139.3 vs. 61.4 mL CH4 g−1 VS). In contrast, substrate type exhibited only a moderate influence, and the interaction term remained relatively small, suggesting limited differential responses among substrates. Thus, the results demonstrate that thermophilic operation markedly enhances methane yield, and that the effect of temperature is modulated by substrate composition, with skimmed substrate showing the highest temperature-dependent improvement.

3.6. Kinetic Analysis

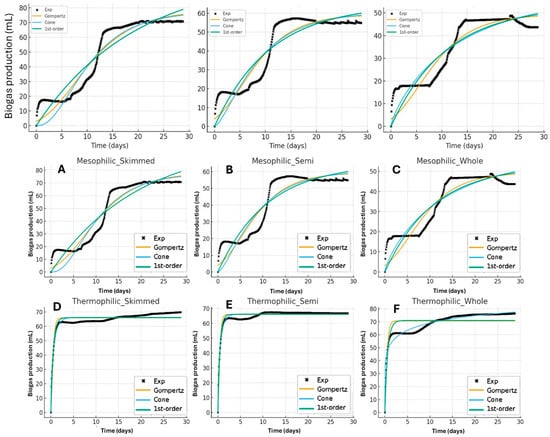

The cumulative biogas production profiles for the six experimental conditions were fitted using three empirical models widely applied to anaerobic digestion kinetics: the modified Gompertz, Cone, and first-order models (Figure 4). Table 6 presents the estimated kinetic parameters and goodness of fit indices.

Figure 4.

Graphical fit of the modified Gompertz, Cone, and first-order kinetic models to cumulative biogas production data from dairy substrates. In mesophilic conditions: (A) Skimmed milk, (B) Semi-skimmed milk, and (C) Whole milk; and in thermophilic conditions: (D) Skimmed milk, (E) Semi-skimmed milk, and (F) Whole milk.

Table 6.

Estimation of kinetic coefficients for dairy substrates via adjustment to the modified Gompertz, Cone, and first-order kinetic models.

Among the models tested, the modified Gompertz model provided the best description for the mesophilic assays, especially for the skimmed substrates, with R2 = 0.93 and RMSE = 6.27. This model captures the sigmoidal nature of cumulative biogas production through its explicit lag term (λ) and growth-related rate constant (Rm), reflecting microbial adaptation and subsequent exponential activity [29,30]. For the mesophilic treatments, the lag phase (λ 1.2 d) was short for skimmed substrates but negligible for semi-skimmed and whole substrates, suggesting rapid microbial acclimation and balanced nutrient availability under mesophilic conditions [31].

In contrast, thermophilic digestion yielded higher kinetic rates (Rm = 80–92 for skimmed and semi-skimmed substrates), with the Gompertz model still describing the data satisfactorily (R2 = 0.84–0.89). However, the Cone model achieved the overall best performance for thermophilic samples, particularly for semi-skimmed substrates (R2 = 0.94, RMSE = 1.50), indicating that the cumulative curves followed a smooth saturation pattern rather than a pronounced sigmoid. The fitted shape factors (n 0.55–0.77) were below unity, implying that gas production rate decreased gradually after the initial rapid phase, something typical of hydrolysis-limited processes under thermophilic operation [32].

The first-order model exhibited acceptable fits in all cases, R2 > 0.83 except for thermophilic whole substrates, confirming that biogas production was predominantly governed by substrate hydrolysis, as expected for soluble and easily degradable substrates such as milk [33]. Nevertheless, its inability to represent the early lag or curvature phases led to higher RMSE values compared to the Gompertz and Cone models.

Comparing effluents, the skimmed substrates showed the highest specific rates (k = 0.051 d−1 mesophilic; 1.93 d−1 thermophilic) and the shortest lag, consistent with its low lipid content and higher fraction of soluble carbohydrates and proteins. Whole substrates, with higher fat content, exhibited slower kinetics (Gompertz Rm = 3.25 mesophilic), and poorer fit quality under thermophilic conditions (R2 = 0.53), suggesting that lipid hydrolysis and possible long-chain fatty acid (LCFA) inhibition delayed methane formation [10,19,28].

Overall, temperature strongly influenced the kinetic response. The comparison between mesophilic and thermophilic operation increased apparent hydrolysis rates (k increased from 0.05 to 0.09 to 1.6–2.2 d−1) and reduced the lag phase, reflecting enhanced microbial activity and faster substrate conversion at higher temperatures. These findings align with previous studies reporting higher reaction rates but also greater sensitivity to inhibition under thermophilic conditions [4,34,35].

Based on the above, the modified Gompertz model is most suitable for describing mesophilic digestion dynamics where lag and microbial adaptation are relevant, while the Cone model best represents thermophilic behavior with smooth hydrolysis-controlled kinetics. Fat concentration modulated these effects: skimmed substrates degraded fastest, and whole substrates showed the slowest kinetics, consistent with the inhibitory influence of lipids and VFA accumulation during start-up.

4. Conclusions

The main results from both mesophilic and thermophilic reactors confirm that the anaerobic digestion of dairy effluents is highly influenced by fat concentration and operational temperature. Under mesophilic conditions, low-fat effluents demonstrated greater process stability and higher COD removal, whereas high-fat substrates caused operational challenges, particularly under thermophilic conditions. On the other hand, thermophilic digestion enhanced methane productivity, with specific methane yields ranging between 105 and 191 mL CH4 g−1 VS, compared with 54–70 mL CH4 g−1 VS under mesophilic conditions. The lower COD removal 5% and higher acidity 37% observed at 55 °C—relative to mesophilic operation, 17% and 30%, respectively—support the hypothesis of VFA accumulation and partial inhibition of methanogenic activity.

Operationally, skimmed effluents achieved the best start-up performance, reflecting lower inhibition risks and improved microbial adaptation. The higher final pH observed in whole-milk assays may indicate greater buffering capacity due to the lipid fraction, which can mitigate acidification. Overall, the results demonstrate that while thermophilic conditions yield higher methane productivity, mesophilic operation exhibits greater robustness during the start-up phase of fat-rich dairy effluent digestion. This conclusion is rigorously confirmed by both the ANOVA statistical analysis of the performance data and the kinetic modeling of the biogas production. Thus, the modified Gompertz model best described mesophilic anaerobic digestion, capturing the short lag of 1.2 days and rapid microbial adaptation of skimmed substrates (R2 = 0.93, RMSE = 6.27), whereas the Cone model more accurately represented thermophilic digestion, particularly for semi-skimmed substrates (R2 = 0.94, RMSE = 1.50), reflecting hydrolysis-limited kinetics. Additionally, the temperature and fat content strongly influenced biogas kinetics, with thermophilic conditions increasing apparent hydrolysis rates (k = 1.93–2.2 d−1) and reducing lag phases, while high-fat whole substrates showed slower methane formation (Gompertz Rm = 3.25 mL CH4 g−1 VS, R2 = 0.53), consistent with delayed lipid hydrolysis and VFA inhibition.

In short, this study quantitatively demonstrates that temperature is the primary driver of methane productivity, whereas fat concentration governs process stability and start-up behavior. The combined statistical and kinetic analysis reveals that higher methane yields under thermophilic conditions are achieved at the expense of lower COD removal and increased VFA accumulation, providing an explanation for the reported instability of thermophilic digestion of lipid-rich substrates.

From an operational perspective, these results indicate that mesophilic digestion is more suitable for the start-up and stable treatment of fat-rich dairy effluents, whereas thermophilic operation should be selected when maximum methane recovery is prioritized and adequate control strategies are in place.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F.-R.; methodology, J.F.-R. and D.F.; software, J.F.-R. and D.F.; validation, J.F.-R. and M.P.; formal analysis, J.F.-R.; investigation, J.F.-R. and D.F.; resources, J.F.-R. and M.P.; data curation, J.F.-R. and D.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F.-R.; writing—review and editing, J.F.-R. and M.P.; visualization, M.P.; supervision, M.P.; funding acquisition, J.F.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been developed in the research Unit of Bioenergy of the National Laboratory of Energy and Geology (LNEG)-Lisbon (Portugal). This work has received support from the project SUSMILK—Re-design of the dairy industry for sustainable milk processing (FP7-KBBE 613589), funded by the European Union under the Seventh Framework Programme; the funding of the Banco Santander Grants.

Data Availability Statement

The main data supporting the findings are included in the manuscript. Additional data information will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author wishes to express her profound gratitude to Santino Di Beradino (R.I.P.) for his valuable scientific guidance and human generosity in welcoming her into his research group to undertake this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Demirel, B.; Yenigun, O.; Onay, T.T. Anaerobic treatment of dairy wastewaters: A review. Process Biochem. 2005, 40, 2583–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.; Prazeres, A.R.; Rivas, J. Cheese whey wastewater: Characterization and treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 445–446, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kougias, P.G.; Angelidaki, I. Biogas and its opportunities—A review. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2018, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirne, D.G.; Paloumet, X.; Björnsson, L.; Alves, M.M.; Mattiasson, B. Anaerobic digestion of lipid-rich waste—Effects of lipid concentration. Renew. Energy 2007, 32, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goli, A.; Shamiri, A.; Khosroyar, S.; Talaiekhozani, A.; Sanaye, R.; Azizi, K. A Review on Different Aerobic and Anaerobic Treatment Methods in Dairy Industry Wastewater. J. Environ. Treat. Tech. 2019, 6, 113–141. [Google Scholar]

- Appels, L.; Baeyens, J.; Degrève, J.; Dewil, R. Principles and potential of the anaerobic digestion of waste-activated sludge. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2008, 34, 755–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, R.; Pandey, A.K.; Kumar, S.; Tyagi, V.V.; Tyagi, S.K. Different aspects of dry anaerobic digestion for bio-energy: An overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 174–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansing, S.; Martin, J.F.; Botero, R.B.; da Silva, T.N.; da Silva, E.D. Methane production in low-cost, unheated, plug-flow digesters treating swine manure and used cooking grease. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 4362–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perle, M.; Kimchie, S.; Shelef, G. Some biochemical aspects of the anaerobic degradation of dairy wastewater. Water Res. 1995, 29, 1549–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Rinta-Kanto, J.M.; Kettunen, R.; Tolvanen, H.; Lens, P.; Collins, G.; Kokko, M.; Rintala, J. Anaerobic treatment of LCFA-containing synthetic dairy wastewater at 20 °C: Process performance and microbial community dynamics. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 691, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Holohan, B.C.; Mills, S.; Castilla-Archilla, J.; Kokko, M.; Rintala, J.; Lens, P.N.L.; Collins, G.; O’fLaherty, V. Enhanced Methanization of Long-Chain Fatty Acid Wastewater at 20 °C in the Novel Dynamic Sludge Chamber–Fixed Film Bioreactor. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.K.; Soupir, M.L. Escherichia coli inactivation kinetics in anaerobic digestion of dairy manure under moderate, mesophilic and thermophilic temperatures. AMB Express 2011, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appels, L.; Baeyens, J.; Degrève, J.; Dewil, R. Influence of temperature and retention time on methane yield in anaerobic digestion of solid organic waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 8180–8187. [Google Scholar]

- Ariunbaatar, J.; Panico, A.; Esposito, G.; Pirozzi, F.; Lens, P.N.L. Pretreatment methods to enhance anaerobic digestion of organic solid waste. Appl. Energy 2014, 123, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, R.; Massé, D.I.; Singh, G. A critical review on inhibition of anaerobic digestion process by excess ammonia. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 143, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Ramiro-Garcia, J.; Paulo, L.M.; Braguglia, C.M.; Gagliano, M.C.; O’Flaherty, V. Psychrophilic and mesophilic anaerobic treatment of synthetic dairy wastewater with long chain fatty acids: Process performances and microbial community dynamics. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 380, 129124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APHA; AWWA; WEF. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 22nd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Holliger, C.; Alves, M.; Andrade, D.; Angelidaki, I.; Astals, S.; Baier, U.; Bougrier, C.; Buffière, P.; Carballa, M.; de Wilde, V.; et al. Towards a standardization of biomethane potential tests. Water Sci. Technol. 2016, 74, 2515–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasit, N.; Idris, A.; Harun, R.; Wan Ab Karim Ghani, W.A. Effects of lipid inhibition on biogas production of anaerobic digestion from oily effluents and sludges: An overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 45, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, M.; Daufin, G.; Gesan-Guiziou, G. Effect of prehydrolysis of milk fat on its conversion to biogas. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91, 4062–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.M.; Pereira, M.A.; Sousa, D.Z.; Cavaleiro, A.J.; Picavet, M.; Smidt, H.; Stams, A.J.M. Waste lipids to energy: How to optimize methane production from long-chain fatty acids (LCFA). Microb. Biotechnol. 2009, 2, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Cheng, J.J.; Creamer, K.S. Inhibition of anaerobic digestion process: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 4044–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Loh, K.C.; Zhang, J.; Mao, L.; Tong, Y.W.; Wang, C.H.; Dai, Y. Three-stage anaerobic co-digestion of food waste and waste activated sludge: Identifying bacterial and methanogenic archaeal communities and their correlations with performance parameters. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 285, 121333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Ahn, Y.H.; Speece, R.E. Comparative process stability and efficiency of anaerobic digestion; mesophilic vs. thermophilic. Water Res. 2002, 36, 4369–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labatut, R.A.; Angenent, L.T.; Scott, N.R. Conventional mesophilic vs. thermophilic anaerobic digestion: A trade-off between performance and stability? Water Res. 2014, 53, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, M.; Dębowski, M.; Krzemieniewski, M. Dairy wastewater treatment in anaerobic reactor with active filling. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2016, 47, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, T.M.; Santos, M.T. Biochemical Methane Potential Assays for Organic Wastes as an Anaerobic Digestion Feedstock. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palatsi, J.; Laureni, M.; Andrés, M.V.; Flotats, X.; Nielsen, H.B.; Angelidaki, I. Strategies for recovering inhibition caused by long chain fatty acids on anaerobic thermophilic biogas reactors. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 4588–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lay, J.J.; Lee, Y.D.; Noike, T. Feasibility of biological hydrogen production from kitchen garbage. Water Res. 1999, 33, 2579–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nopharatana, A.; Pullammanappallil, P.C.; Clarke, W.P. Kinetics and dynamic modelling of batch anaerobic digestion of municipal solid waste in a stirred reactor. Waste Manag. 2007, 27, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugba, P.N.; Zhang, R. Treatment of dairy wastewater with two-stage anaerobic sequencing batch reactor systems—Thermophilic versus mesophilic operations. Bioresour. Technol. 1999, 68, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavilin, V.A.; Qu, X.; Mazéas, L.; Lemunier, M.; Duquennoi, C.; He, P.; Bouchez, T. Methanosarcina as the dominant aceticlastic methanogens during mesophilic anaerobic digestion of putrescible waste. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2008, 94, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, C.; Zhou, Q.; Fu, G.; Li, Y. Semi-continuous anaerobic co-digestion of thickened waste activated sludge and fat, oil and grease. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 1752–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Wu, C.; Zhang, J.; Han, S.; Peng, Y.; Song, X. Impacts of lipids on the performance of anaerobic membrane bioreactors for food wastewater treatment. J. Memb. Sci. 2023, 666, 121104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Su, H.; Baeyens, J.; Tan, T. Reviewing the anaerobic digestion of food waste for biogas production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 38, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.