Abstract

Limitations associated with traditional automation approaches within manufacturing have driven the pursuit of more flexible and intelligent robot guidance methods. One promising development in this area is the integration of external multitarget six degrees of freedom (6 DoF) distributed large-volume metrology (DLVM) into the control loop. Although multiple standards exist across dimensional metrology, motion tracking, indoor positioning, robot guidance, and machine tool accuracy, there is no harmonised, technology-agnostic standard that fully encompasses the unique challenges of 6 DoF DLVM systems for dynamic applications. This work identifies key gaps in the current standards’ landscape and presents a technology-agnostic candidate test methodology intended to support future standardisation of dynamic DLVM performance evaluation. The method provides a metrologically grounded spatial reference path and a temporal alignment strategy so that position and orientation errors can be reported in the intrinsic coordinates of the path. The paper covers the basic principle of the test, artefact construction, synchronisation strategies, preliminary error modelling, and a baseline uncertainty approach, and reports representative results from initial prototype trials on a multi-nodal distance-camera DLVM system. The prototype results demonstrate feasibility and highlight temporal sampling and traceable timing as current limiting factors for fully deconvolving latency and pose error; these aspects are therefore positioned as instrumentation requirements and the focus of ongoing work.

1. Introduction

Traditional robotic manipulators are proficient at performing repeat tasks in controlled manufacturing environments, exemplified by automotive assembly lines [1,2,3]. However, their rigid architectures, reliance on static programming, and complex calibration and validation requirements make them unsuitable for industries with intrinsically high production or process variability, e.g., industries dealing with small batches or customised products [4,5,6,7]. The potential productivity gains from flexible automation and its wider adoption across manufacturing have driven the pursuit of more intelligent robot guidance methods. Advances in integrated sensors [8,9], telecommunications [10,11], computational power [12], and increasingly sophisticated control methods [5,7,8,13] are creating a foundation for next-generation robotic systems capable of greater operational flexibility and autonomy. One promising development in this area is the integration of multitarget six degrees of freedom (6 DoF) distributed large-volume metrology (DLVM) systems into the robot control loop. By leveraging multiple, spatially distributed sensors, or nodes, working in concert, DLVM systems can track multiple objects simultaneously over large working envelopes. This approach overcomes the occlusion issues inherent in single-node systems and enables the concurrent monitoring of both the end-effector and workpiece within a common coordinate frame thereby enabling operations based on relative pose. Other advantages include the implementation of dynamic control zones intended to deliver enhanced performance only where necessary [14]. This can reduce costs associated with specialisation and could enable compliant generalist robots to execute precision tasks through loco-regional closed-loop control. Furthermore, by tracking tools and/or human co-workers in real time, DLVM could enhance human–robot interoperability and collaboration improving both agility of production and safety [9].

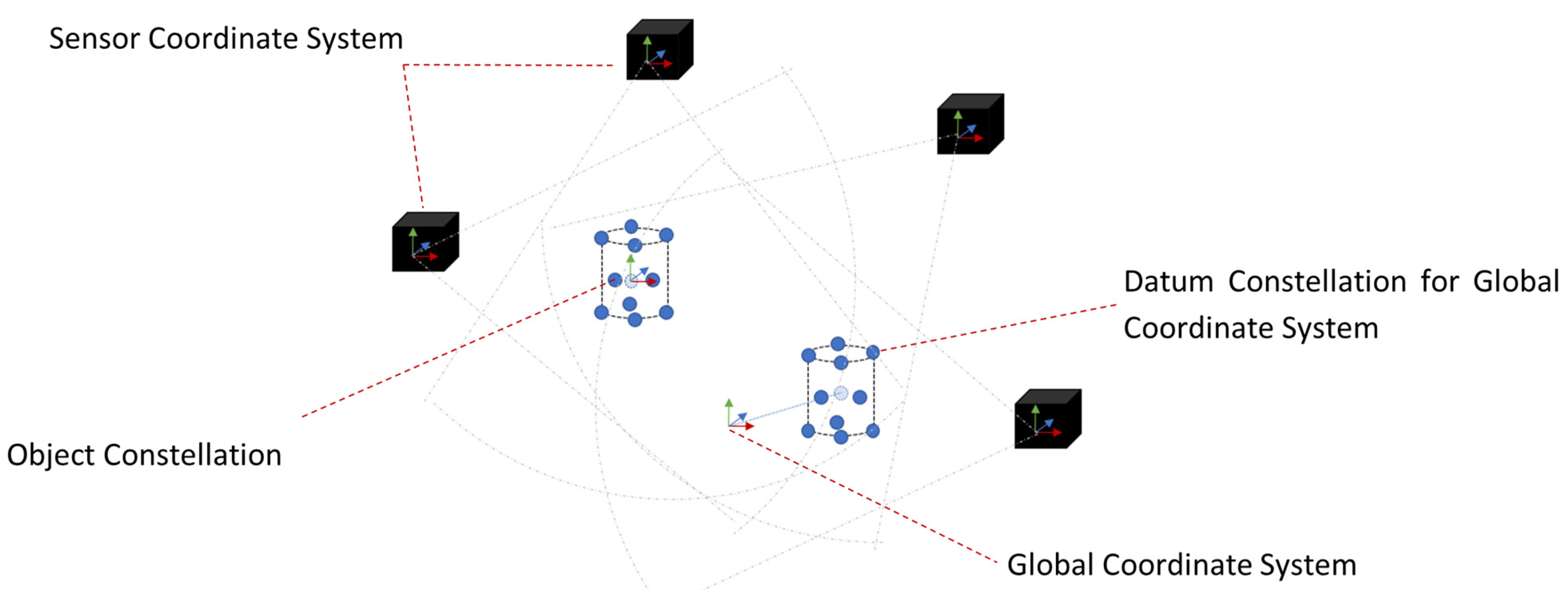

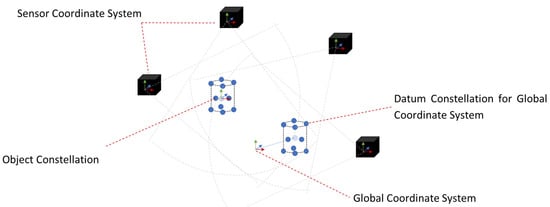

DLVM systems utilise a wide range of carrier signals, processing methods, and metrological principles. Technologies may incorporate elements of photogrammetry, laser radar, inverse kinematics, micro-electro-mechanical systems, structured light projection, interferometry, machine vision, or hybrid approaches. However, for precision applications, photogrammetric methods are most common. Figure 1 shows a diagrammatic representation of a typical photogrammetric DLVM system. A system may require calibration to determine the extrinsic parameters of the nodes or make measurements relative to a reference artefact or datum constellation on a frame-by-frame basis.

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of a distributed, multitarget, six degrees of freedom (6 DOF) large-volume metrology (DLVM) system. Black boxes represent imaging nodes with respective field-of-view represented by dotted lines. Two constellations are shown with the global coordinate system defined offset to the datum constellation.

The high initial investment required for DLVM, encompassing multiple high-precision sensors, calibration infrastructure, and integration with existing manufacturing systems, poses a significant barrier to its adoption. Alternative precision measurement approaches, such as single-point laser trackers, structured light scanners, or robotic vision systems, may provide sufficient accuracy at a fraction of the cost and complexity for a wide array of tasks. Indeed, traditional fixed tooling and jigs, while less flexible than DLVM, offer predictable and repeatable alignment without the need for continuous metrological feedback. Furthermore, advancements in robot calibration and in situ metrology such as force sensors, on-arm vision, and AI-driven corrections allow for enhanced accuracy without the full infrastructure of a distributed metrology system. However, despite the high cost, DLVM systems still have the potential to usher in a new paradigm in agile, traceable, precision automation. The potential impact on current manufacturing is most compelling in high-value sectors that require both precision and adaptability, such as aerospace assembly and large-scale industrial production [15,16]. In aerospace, DLVM enables measurement-assisted assembly, reducing reliance on tooling and improving repeatability, while in other large-scale industries, and more broadly Industry 4.0, it facilitates real-time quality assurance and adaptive manufacturing [16,17]. However, irrespective of cost and complexity, the adoption of DLVM within manufacturing remains constrained by a lack of standardisation in performance characterisation, which limits industrial confidence in measurement reliability and traceability [18].

Although multiple standards exist across dimensional metrology, motion tracking, indoor positioning, robot guidance, and machine tool accuracy, there is no harmonised, technology-agnostic standard that fully encompasses the unique challenges of 6 DoF DLVM systems for dynamic applications. Key performance metrics, including accuracy, repeatability, latency, and dynamic range, must be defined and measured in tests that account for environmental factors such as thermal expansion, refractive index variations, and mechanical vibrations [17]. Table 1 provides an overview of existing standards relating to the performance characterisation of large-volume metrology systems and lists their limitations when applied to DLVM systems with consideration of their application to robot guidance within a manufacturing setting.

Table 1.

Overview of standards relating to multitarget six degrees of freedom (6 DOF) large-volume metrology (DLVM) systems.

Although existing standards provide valuable guidance within their respective domains, none offer a comprehensive, unified framework for evaluating the performance of DLVM systems under dynamic, multitarget conditions. The existing methods often assume a particular instrument or setup, which can exclude emerging technologies. Intersystem comparison is a potential method to apply (ASTM E2919–22, ASTM E3064-16); however, this requires a sufficiently accurate metrologically traceable reference system which may not be available for dynamic measurements. Metrics related to temporal factors, such as latency, are mentioned but are the focus of ongoing research (ASTM E3064-16). Finally, from an application perspective, DLVM systems are intended to track targets within a dynamic environment introducing additional influence factors such as variable sensor occlusion. In summary, the identified gaps are the following:

Technology Agnosticism: The absence of a technology-agnostic test method suitable for different sensor types and metrological approaches.

Coherent Static and Dynamic Performance Characterisation: The lack of test procedures that adequately evaluate both static and dynamic measurement capabilities within a single, coherent framework.

Complex System or Process Variables: The inability to accommodate unique DLVM test variables when considering the application of robot guidance in a manufacturing process. These include sensor occlusion, sensor and target configuration, and the number and simultaneous movement of targets or multi-target constellations.

Industrial Relevance: The lack of tests that replicate industrially relevant environmental conditions, addressing real-world factors like temperature gradients, ambient lighting conditions, humidity, and vibration.

1.1. Addressing the Gap

An approach to address the identified gaps could be as follows: Static calibration and traceability: use ISO 10360 or VDI 2634 procedures to establish basic accuracy and traceability of a system under stable static conditions (e.g., verifying scale accuracy with calibrated lengths, as a baseline). Dynamic performance: application of a method akin to ASTM E3064-16 (dynamic trajectory and error analysis) to assess how accuracy degrades as a function of increasing speed, introducing temporal considerations such as latency and packet loss. Such tests may incorporate or extend elements of static 6DoF analysis methodologies described in ASTM E2919-22 and ISO/IEC 18305:2016. Environmental compensation: ensure procedures account for environmental variation potentially integrating guidelines from surveying standards (ISO 17123) for field temperature/pressure measurement. Ideally, the test, or elements of it, should be reproducible in situ to allow for (re)verification and acceptance testing of systems within the working environment. Generic tests for static measurement are well established, although dynamic range remains a challenge. Therefore, the proposed methodology will focus on dynamic performance testing.

1.2. Aim

This work aims to develop a generalised, technology-agnostic candidate test methodology for evaluating the performance of DLVM systems for dynamic applications, as a step towards future standardisation and third-party benchmarking. The work seeks to provide the essential validation tools and performance benchmarks by integrating relative motion between multiple constellations, combining static and dynamic measurements within a single framework, facilitating intersystem comparison, and accounting for temporal and environmental influence factors. The purpose of the test(s) is to facilitate third-party certification, (re)verification, and (re)acceptance to establish confidence in DLVM technologies thereby promoting their broader industrial adoption and ultimately enhancing the operational flexibility of automated systems within manufacturing settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Summary of Test Method

Table 2 identifies test parameters and defines the scope of the current test design. To simplify proof of concept a circular path perpendicular to the gravitational force vector has been selected which benefits from steady state motion at constant angular velocity. To realise this, a length gauge consisting of two rigidly affixed target constellations is mounted on a rotational actuator with the combined centroid nominally coincident with the axis of rotation. The pose of the two target constellations in relation to the axis of rotation is established through traceable measurement. When rotated, the target constellations transit a circular path of known radius. Adopting the standard definition of cartesian and spherical polar coordinates in BS EN ISO 80000-2 [31], location on the path is parameterised by the output of a precision rotational encoder, Φ, and synchronised with time, t, where synchronisation between the actuator, the data acquisition computer (DAQ), and—where feasible—the system under test is pursued in the present prototype via EtherCAT. However, the methodology is intended to remain compatible with alternative synchronisation architectures and traceable timing sources, recognising that the achievable update rate and timestamp definition can dominate the temporal uncertainty in early implementations. Sequential oscillating, stop-measure-move, and continuous motion data collection protocols are performed. The oscillating protocol establishes temporal alignment between the reference encoder and positional measurements of the system under test. The stop-measure-move protocol establishes transformations between the global coordinate frame of the system under test and the local coordinate frame of the rotating artefact and subsequently the intrinsic coordinates of the circular path. The continuous motion protocol rotates the target constellations at constant speed in discretely increasing steps and compares dynamic measurement performance against static measurement performance.

Table 2.

Overview of test design criteria.

Errors in both the position and orientation of individual constellations are reported in the intrinsic coordinates of the circular path , where is the direction of motion tangential to the circular path and er the radial orientation from the centroid of the circular path. Errors in the position and orientation of individual constellations are also reported relative to each other to provide supplementary time-invariant information.

The test facilitates three core measurement strategies to quantify system performance:

- Intra-system comparison: a path is determined statically using the stop-measure-move protocol. Dynamic performance is then expressed relative to static performance. This relative measurement is not influenced by uncertainty introduced by the calibration procedure but still requires temporal synchronisation. The test would have to be combined with other tests to characterise static performance.

- Inter-system comparison: transformations between the global and local coordinate frames are determined using calibration procedures combining in situ and ex situ methods. With sufficient characterisation of the artefact and a robust uncertainty model the path can be known absolutely. Static and dynamic performance is then compared against the ground truth path.

- Concurrent inter-system comparison: test will be designed such that systems able to operate concurrently can be directly compared in situ.

2.2. Path Selection

DLVM systems do not inherently provide an intrinsic coordinate system for error mapping. Except for specific orthogonal sensor configurations, linear motion typically introduces orientation changes relative to one or more sensors. To address this, a circular path was selected because it samples a wide range of orientations within a defined region, enabling robust performance evaluation across multiple variables. Circular paths also allow steady-state motion at constant angular velocity, require only a single reference encoder, can reduce exposure to spatial thermal gradients, and eliminate the need for additional space for acceleration or deceleration. Spatial specificity during steady-state motion can be achieved through trigger gating or by synchronising the rotational period with the measurement frame rate. During steady rotation, latency τ can be expressed as a phase offset ΔΦ = ωτ, so latency-aware comparisons can use the path frame evaluated at the previous position Φ(t − τ) and variance in Φ(t − τ) as a function of test variable can be reported.

Disadvantages include variation in radial position among targets within a constellation, which results in differing tangential speed and individual path curvatures, and centripetal acceleration (∝ ω2r) causing radial deflection.

Although the methodology broadly applies to arbitrary paths, establishing a traceable ground truth for complex trajectories is challenging due to actuation complexity and dynamic effects. The current setup is limited to horizontal rotations to minimise influence factors, but the apparatus can operate in any orientation. Ongoing work aims to characterise uncertainty under these conditions. The test currently evaluates performance as a function of velocity, position, and orientation, but could be extended to include acceleration and jerk. Additionally, radial position may be introduced as a test variable to study performance as a function of path curvature. If multiple orientations and curvatures are tested, results could inform predictions for more complex paths representative of real-world use cases; however, further work is required to achieve this.

2.3. Artefact and Actuator Assembly Design

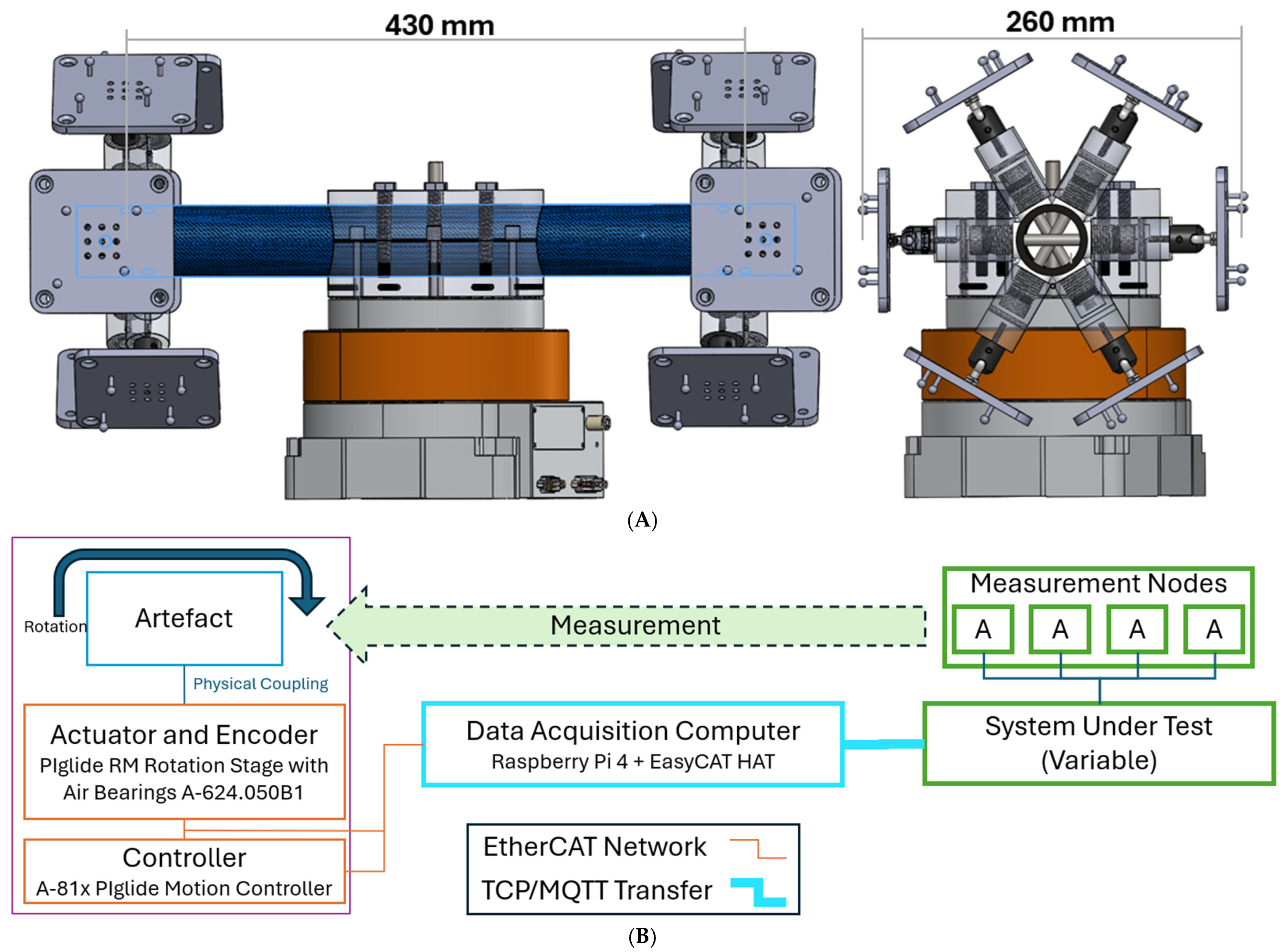

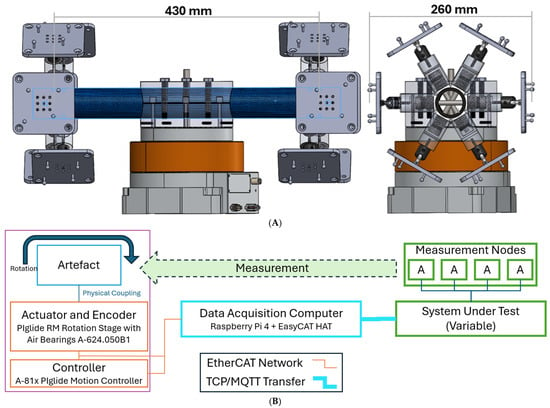

Figure 2 shows the artefact design with representative target constellations. The assembly consists of two target constellations, adjustable spokes, a tubular body, a split clamp, and a rotational actuator. The target constellations are exchangeable to accommodate different DLVM technologies and requirements. The current configuration accommodates the Iona system produced by InSphere, which is a multi-nodal distance camera system [33]. The target constellations comprise six tiles each supporting four spherical retroreflector targets.

Figure 2.

(A) CAD model test artefact mounting two multi-target constellations and mounted on a rotational actuator. (B) Schematic representation of the experimental apparatus.

The tiles are positioned in a collar formation with each retroreflective sphere achieving a similar rotational velocity during rotation. Each spoke consists of a lockable ball and socket connector atop a carbon fibre tube allowing the mounted targets to be reorientated, facilitating target constellation reconfiguration if required. The spokes of both target constellations connect to a body consisting of a single roll-wrapped carbon fibre tube. A tube was selected for simplicity and to allow the use of analytical modelling to estimate deflection. An aluminium split clamp couples the tubular body to the actuator. The mating surfaces of the tubular body are ground to match the cylindrical form of the clamp to produce a tight fit. The clamp is a solid cylindrical construction engineered to rigidly affix the tubular body in place thereby allowing each end of the tube to be modelled as a cantilever to a first approximation. Detailed mechanical modelling is ongoing. The assembly is nominally symmetrical with the addition of movable masses to facilitate balancing. A locator pin, nominally colinear with the axis of rotation, runs through the clamp, tubular body, and into the actuator to serve as a datum feature to construct a local coordinate frame. A PIglide RM Rotation Stage with Air Bearings A-624.050B1 and absolute angle measuring system provides precision rotational location and velocity. Additional features of the assembly include mountings for a Spherically Mounted Retroreflector (SMR) at each end of the tube and one near the locator pin on the split clamp to facilitate concurrent measurement using a laser tracker and/or to establish absolute position of the path.

2.4. Coordinate System Construction and Calibration Strategy

Calibration activities establish the position and orientation of the artefact’s features relative to datums that simplify the mathematical description of the rotational motion and deformation of the artefact due to dynamic forces.

To avoid ambiguity in coordinate frame definitions and usage, we adopt three frames with fixed meanings throughout:

- Global coordinate frame refers to the reference frame of the system under test; the frame within which the reports pose and in which inter-system transformations are established for comparisons and benchmarking.

- Local coordinate frame refers to the artefact’s calibration frame constructed from its physical datums (e.g., Datum A: axis of rotation; Datum B: tubular body axis) and origin definition and is the frame in which the circular path and its intrinsic coordinates are parameterised.

- Object coordinate frame refers to a frame attached to an individual target constellation or feature mounted on the artefact (e.g., tiles, SMRs, locator devices), used when reporting pose relative to the local frame or when defining constellation-specific orientations.

Transformations are applied in the order Global ↔ Local ↔ Object, with error reporting clearly stating the frame of reference. Unless otherwise noted, path-intrinsic errors are expressed in the local frame of the artefact, and constellation orientations are aligned with the path directions as follows:

The following outlines a strategy for constructing the artefact’s local coordinate system during calibration:

- (1)

- Datum A is the axis of rotation which defines the z direction.

- Datum A is determined by measurement of a locator pin feature nominally coincident with the axis of rotation. Error associated with the rotation or misalignment of the locator pin can be accounted for by measuring the locator pin multiple times whilst rotating the artefact using the actuator as an additional step in the calibration procedure.

- (2)

- Datum B is the axis of the tubular body. The orientation of the projection of Datum B onto the plane perpendicular to Datum A defines the x orientation.

- The axis of the tubular body is measured by sampling the outer surface of the tube at both sides of the split clamp.

- (3)

- The origin is determined by the point of closest approach between the axis of rotation (Datum A) and the axis of the tubular body (Datum B) projected onto Datum A within the plane perpendicular to Datum A.

- (4)

- The y orientation is defined as orthogonal to the x and z directions.

- (5)

- The target constellation centroids are determined by measuring the relative positions of the target(s) that constitute the constellation.

- For the example given in Figure 2 this involves measuring the centroids of multiple spherical retroreflector targets and taking the average. Although technically challenging it is, conceptually, a simple measurement of physical spheres. For other technologies the traceable measurement of the target constellation centroids may be non-trivial

- (6)

- The origin of the respective paths of the two target constellation centroids is defined as the projection of the centroids onto the axis of rotation (Datum A) within the plane perpendicular to Datum A.

- (7)

- A coordinate frame is established for each target constellation with the origin at the centroid of the spheres orientated with the ex_constellation = er_path, ey_constellation = eθ_path, and ez_constellation = eφ_path, where er_path, eφ_path, eθ_path describe the intrinsic coordinates of the circular path of the constellation centroid as it rotates around Datum A.

- (8)

- Additional features, e.g., SMRs or physical locator devices, can be incorporated into the artefact assembly and their position and orientation within the object coordinate system measured during calibration procedures.

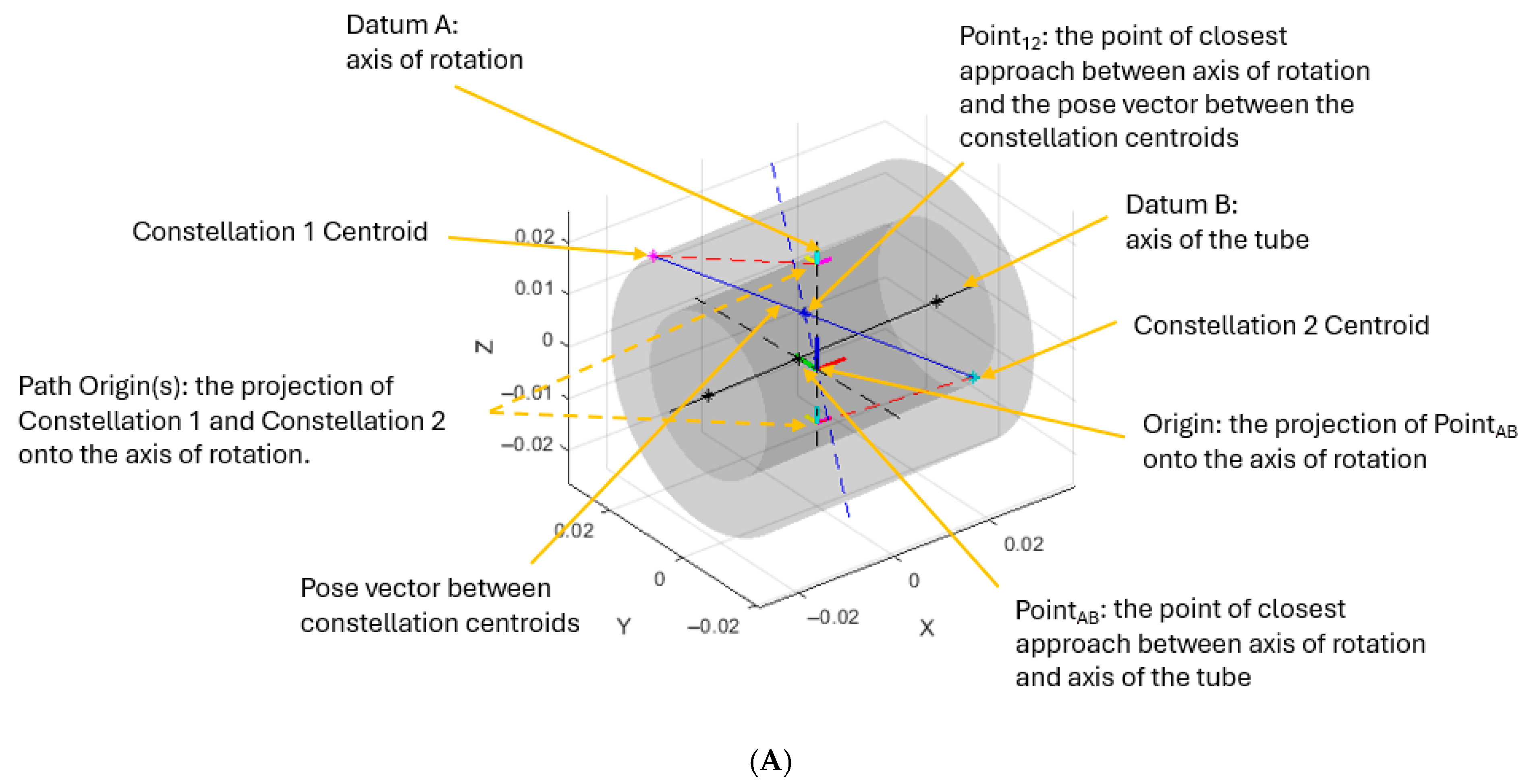

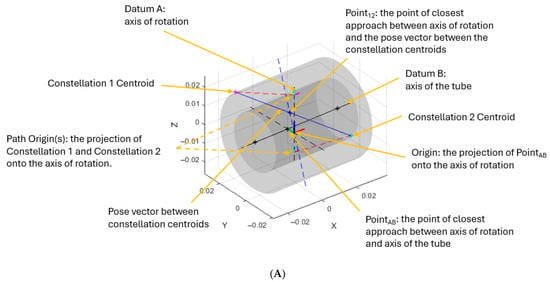

Figure 3 shows a representation of the artefact geometry complete with kinematic errors expected due to limitations imposed by manufacturing tolerances. To visualise these errors the length of the tube constituting the tubular body has been reduced to be equal to its outer diameter thereby accentuating geometric errors. The deviations from nominal are as follows: non-coincidence of the axis of rotation and the axis of the tubular body, non-collinearity of the tubular body and the plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation, and non-collinearity of the axis of the tubular body and the inter-constellation centroid pose vector.

Figure 3.

The potential deviations from ideal artefact geometry that constitute kinematic error (A) annotated overview of plot elements and (B) orthogonal views of A along cardinal axes.

Additional calibration activities can be performed on the rotational actuator; however, these are covered within existing standards [34]. Except for variation in the orientation of the rotational axis over a full rotation, dynamic effects are not included in the calibration strategy and must be accounted for in the error model or mitigated in the analysis.

2.5. Data Acquisition

Data is collected in three distinct protocols:

Protocol 1: Oscillation—the rotational actuator operated under positional control slowly oscillates between two locations, e.g., +/−5°, over a set period following a sinusoidal pattern. The system under test samples this motion. For completeness, this protocol can be repeated at the start and end of data collection to check for consistency over the test duration. The amplitude and frequency of the oscillation is chosen such that the motion is well resolved both spatially and temporally to allow robust model fitting and to avoid accelerations that could induce dynamic effects. Precise guidance on optimal parameters will require further elucidation. Indeed, alternative methods such as cross-correlation of chirp-like motions may be more practical and should be investigated further.

Protocol 2: Stop-Measure-Move—the actuator performs one complete rotation waiting at several discrete locations to allow the system under test to capture multiple measurement frames of the static target constellation(s). The resulting measurements thereby sample the path of the target constellation(s) over one complete rotation whilst benefiting from laws of averaging. For completeness, the protocol can be repeated before and after the dynamic protocol to check repeatability and detect drift over the test duration.

Protocol 3: Continuous Motion—the actuator rotates at constant angular velocity whilst the system under test captures multiple measurement frames. Pose information is timestamped at the point it is registered and telegraphed by the system under test and received by the data acquisition computer (DAQ). The pose of the actuator remains unchanged over all protocols. Excluding dynamic effects, which will be discussed in the error evaluation section, the path sampled by Protocol 2 and Protocol 3 is nominally identical. The measurement frame rate or angular velocity should be adjusted such that the whole path is well sampled throughout data collection. Alternatively, synchronising the data collection rate with the periodicity of the rotation can allow for repeat measurements at discrete locations.

Protocol 3 requires temporal synchronisation of the actuator and DAQ to correlate location on the path as measured by the actuator encoder against position measured by the system under test. Synchronisation is achieved via EtherCAT, which theoretically provides sub-microsecond alignment by continuously adjusting receiver clocks to the transmitter, compensating for drift and skew. Hardware timestamping eliminates software delays, enabling deterministic communication, while propagation delay compensation maintains alignment across devices. Although EtherCAT supports sub-microsecond synchronisation, the actual update rate achieved for actuator position was approximately 170 ms, far higher than expected, likely due to limitations of the EasyCAT Py HAT used in the current setup. At the maximum test speed (3 m·s−1), this corresponds to ~500 mm of travel between samples, introducing significant temporal uncertainty. While interpolation during steady-state motion mitigates some effects, discretisation remains a dominant uncertainty source and analysis of the system under test’s temporal characteristics is limited. Future iterations will address this by improving data collection, potentially eliminating reliance on EtherCAT bus scrubbing entirely, and incorporating a traceable ground truth source of time.

Synchronisation between the actuator and system under test is beneficial to minimise temporal effects, i.e., latency, jitter and drift. However, the test should attempt to quantify these error sources and, if possible, deconvolve temporal error from pose measurement error within the data analysis. To fully deconvolve temporal effects it may be necessary to run the data collection protocols in a synchronised and unsynchronised state.

The starting pose of the artefact, including position and orientation of the axis of rotation and the encoder value, Φ, can be determined through static measurement. Therefore, with reference to the calibration data, the nominal path can be determined absolutely within measurement space.

Initially, to simplify the test, rotation is performed horizontally, with the axis of rotation colinear to the gravitational force vector, enabling steady state motion to be established. This reduces orientation-dependent deflection of the cantilevers and the potential for resonant vibration at specific rotational velocities. However, the test could in principle be performed in any orientation with a sufficiently rigid artefact and appropriate error model.

Increased accuracy could be achieved though compensation using integrated sensors, e.g., strain gauges or temperature sensors built into the body to measure vibration, extension, and deflection, or thermal effects such as expansion or drift in material properties, respectively.

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Overview

Data collected over the three protocols provides rich information on the performance of the system under test. This section details the data analysis. Table 3 provides a summary of the analysis which is then expanded upon in the subsequent sections.

Table 3.

Summary of analysis and intended measurement.

2.6.2. Analysis 1: End-to-End Latency Measurement—Temporal Synchronisation

Data collected during Protocol 1, oscillation, is stored in a database of timestamped events. Events include each frame of the EtherCAT bus which contains information on time, encoder position, and pose information of the system under test. If synchronisation between the DAQ and system under test cannot be established, pose capture events are recorded and timestamped at the points they are triggered, telegraphed, and received. Data is synchronised at the time it is received by the DAQ. The encoder position is interpolated with the sin function used to drive the motion. The interpolated encoder signal is then aligned to the system under test’s positional data. The offset, or phase lag, is the temporal latency between the actuator encoder values and the system under test’s data capture event. The correction includes latency between the system under tests data capture and time stamping events due to processing at the node level.

While the oscillation protocol provides a practical method to estimate latency through phase offset analysis, a fully traceable measurement requires temporal synchronisation across all components to a stable, high-accuracy time source. Incorporating a grandmaster clock for deterministic timestamping is therefore a key focus of ongoing work.

2.6.3. Analysis 2: Comparison to Expected Path

Protocol 2, stop-measure-move, samples the path of a target constellation as measured by the system under test statically at discrete locations. Statistical averaging over repeat measurements cancels out stochastic error resulting in a precise measure of the target constellation pose at a recorded location on the path parameterised by the actuator’s encoder, Φ, value. Fitting a circular model to the data and comparing against expected values determined through calibration activities and uncertainty estimation provides a measure of scale error and trueness. Robust fitting methods such as Random Sample Consensus (RANSAC) can be used to reduce the influence of outliers. Assuming a normal dispersion of measurement points, an uncertainty envelope, e.g., 95% confidence interval, on the position of a single measurement is represented by a triaxial ellipsoid centred on the path at a given location. The discrete locations on the path and their associated uncertainty envelope can be interpolated with a circular model. Results can be reported as deviation from model parameters within the intrinsic coordinate of the target constellation path and/or visualised as deviations from model parameters as a function of Φ.

If the positional data exhibits low circularity and/or statistically significant locoregional deviations from the expected path interpolation can be performed using a spline method or kernel-based method for fitting localised data.

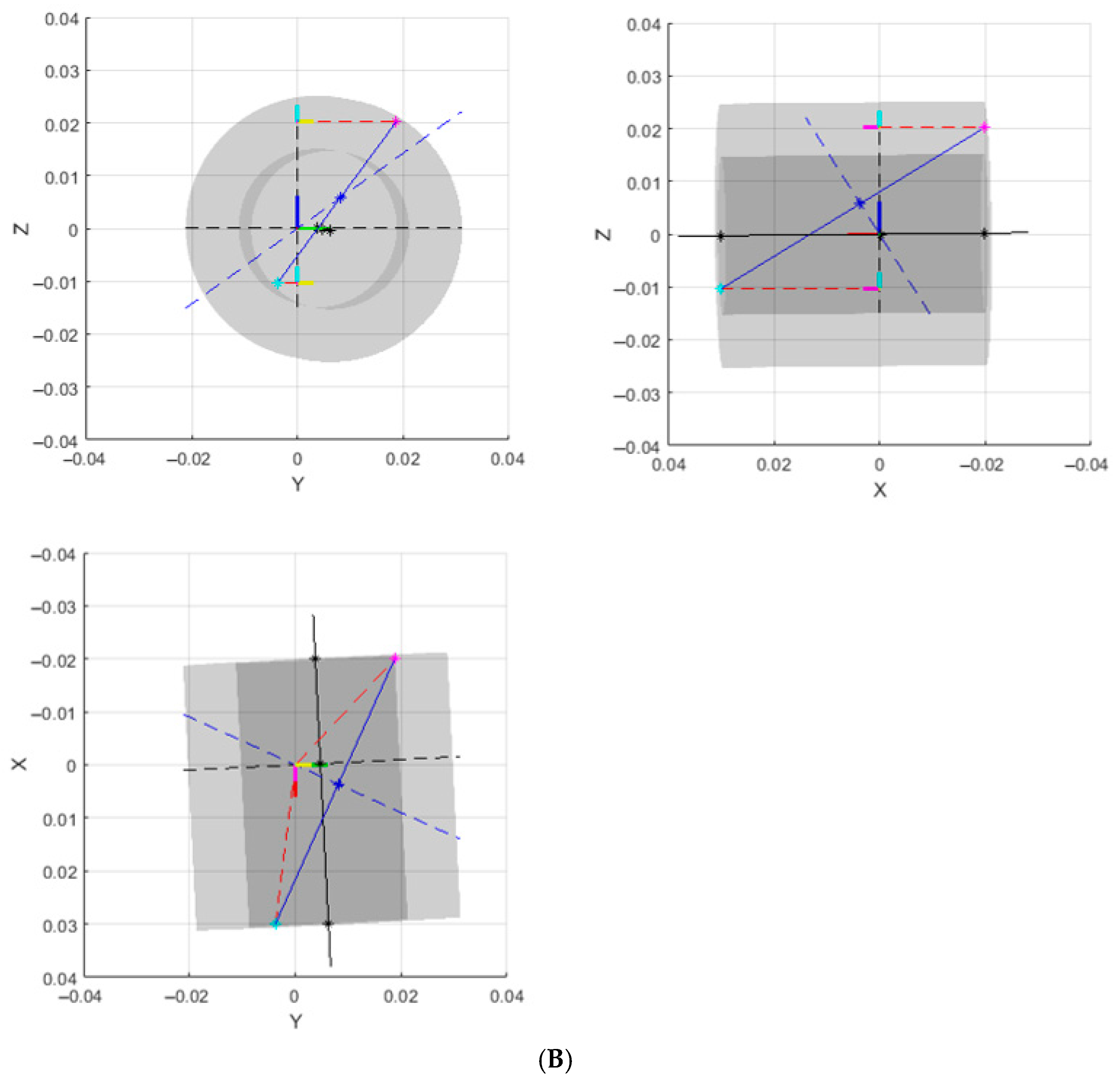

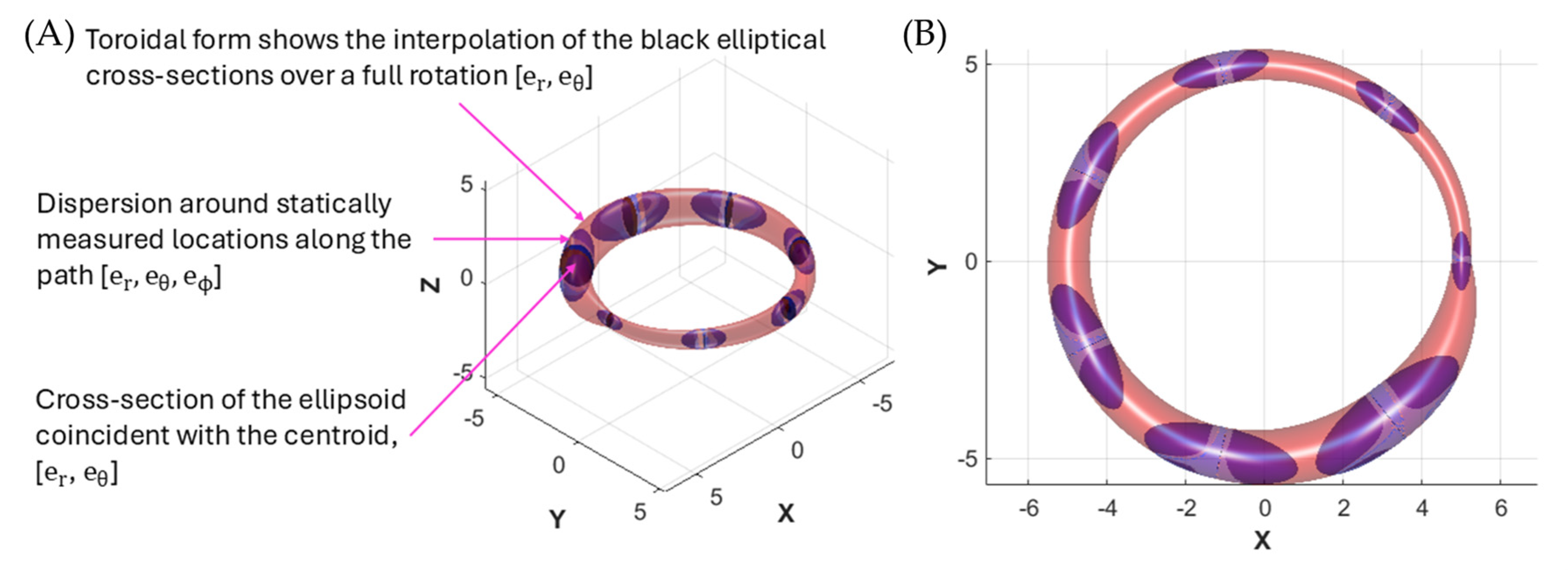

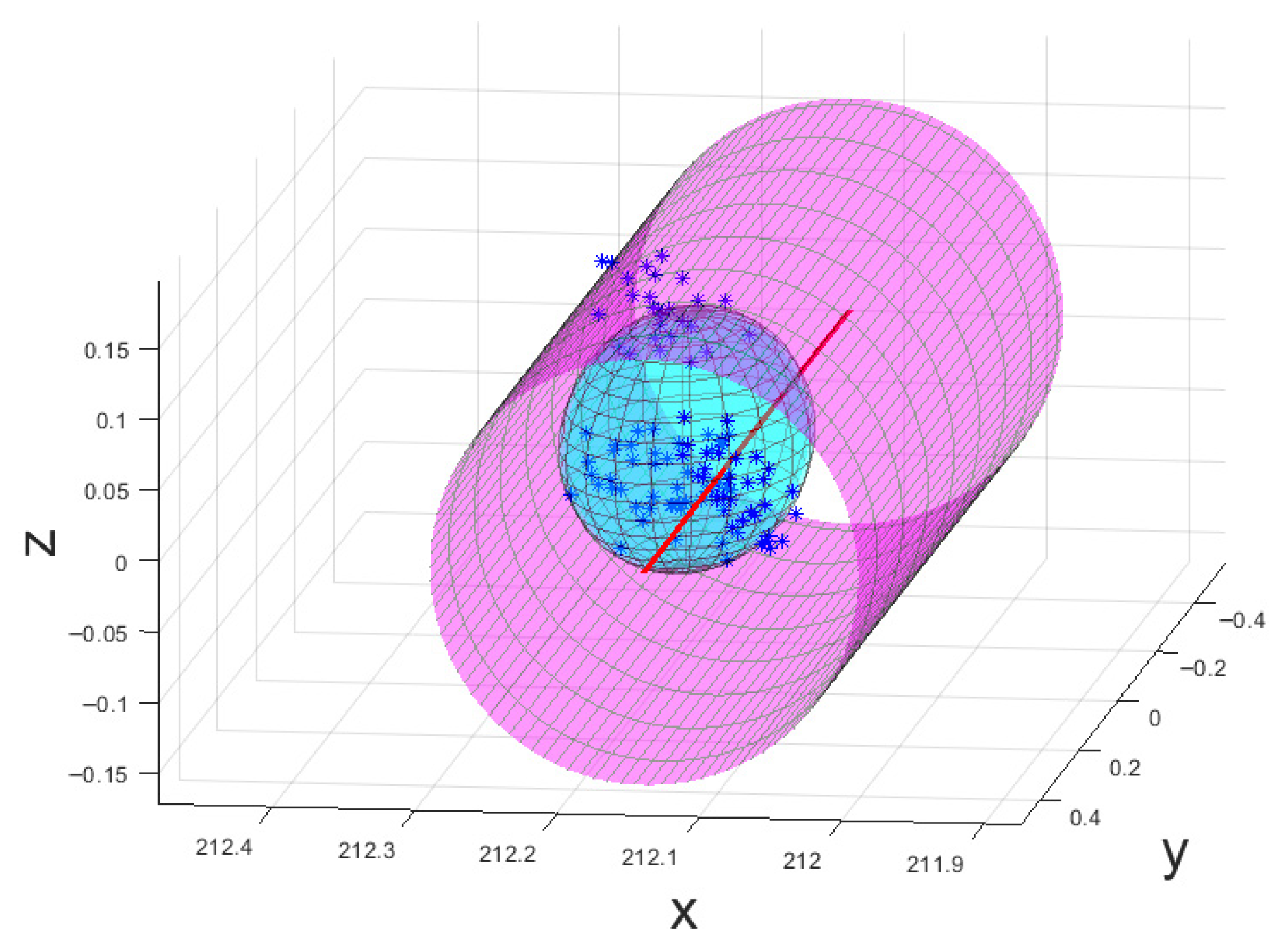

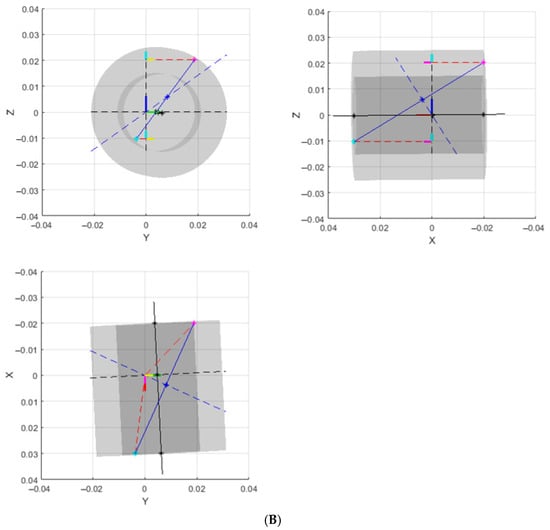

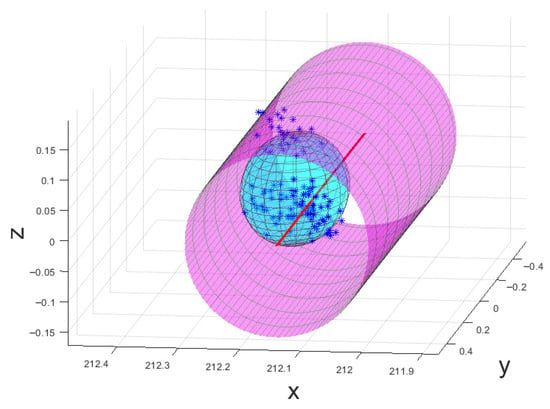

Figure 4 illustrates an uncertainty envelope associated with a path interpolated between seven static measurement locations taken using Protocol 2, stop-measure-move, and a triaxial ellipsoid representing the components of the 95% confidence interval in the er, eθ, eϕ directions. Uncertainty in six degrees of freedom is swept to form the envelope; however, the toroidal envelope shows only er and eθ. Quaternion representation of orientation facilitates interpolation. Seven locations exhibiting distinct dispersions were chosen to illustrate path uncertainty and interpolation. However, the number of locations taken in a real test will be much greater to ensure appropriate spatial sampling and minimise interpolation error.

Figure 4.

Illustrative representation of an uncertainty envelope of a path interpolated between seven discrete locations measured using a stop-measure-move protocol from (A) perspective [0.5, 0.5, 0.5] and (B) perspective [0, 0, 1] colinear with the axis of rotation.

2.6.4. Analysis 3: Intra-System Comparison—Dynamic Measurement Against Statistically Determined Path

This method compares a system’s dynamic performance against its own static performance. Data is collected with Protocol 3, continuous motion, over a range of angular velocities. Depending on the interpolation method used to determine the static path systematic bias in the measurement of position or orientation which is present in both the static and dynamic data, cancel out allowing the effect of motion to be better isolated. Performance relative to static performance can be reported within the intrinsic coordinates of the path. Results can be expressed as a function of angular velocity in the form of summary statistics across the full test or data can be plotted against Φ to visualise systematic reductions in measurement performance relative to location on the path and its corresponding position and orientation in real space.

Temporal domain errors, e.g., sensor integration time, node synchronisation accuracy, event clock jitter, and variable processing and signal telegraphy, will manifest within the spatial domain as latency or jitter along the path. Therefore, a metric should be provided on the measure path location vs. actual path location, e.g., angular deviation from reference encoder (Φmeas − Φref) and the corresponding arc length along the path.

2.6.5. Analysis 4 Relative Pose of the Two Target Constellations

The pose of Constellation B can be measured within the coordinate frame of Constellation A. Constellation B is nominally static relative to Constellation A. Deviations from reference measurements in the pose vector between the two target constellations can be plotted as a function of encoder Φ or as summary statistics over any arbitrary static or dynamic path. Summary statistics are independent of temporal error. For a circular path, motion is nominally orthogonal to the pose vector which may limit sensitivity to motion-induced error, e.g., any effect that biases both target constellations equally along the path will not show up in the data. The test is similarly insensitive to systematic error that affects both target constellations equally, e.g., pose error on a third datum constellation or any other method to determine the global coordinate frame on a frame-by-frame basis. Additionally, orientation error on the datum constellation, Constellation A, will present as positional and orientational error of Constellation B. This convolution or error sources weakens the interpretability of the results.

2.6.6. Analysis 5 Correlation of Paired Target Constellation Pose Deviations from Mean

Some DLVM systems determine their global coordinate system on a frame-by-frame basis. Error associated with this can be tested by measuring the correlation between paired deviations of the two quasi-independently measured target constellations from their respective group mean values during static data collection for a single location. Correlation is observed only when an influence factor operates on both target constellations to induce a similar deviation from their respective means. Any correlation in the paired deviation from mean over repeat measurements of a static artefact can be assumed to be a consequence of the global coordinate frame or global influence factor, e.g., ambient lighting conditions. This test may be useful for (re)verification and acceptance testing for specific sensor or target configurations.

2.6.7. Analysis 6: Inter-System Comparison

An inter-system comparison can be performed against a reference system with data collected concurrently or sequentially. Applying the principles of ASTM E2919–22 a well-characterised benchmark system with an accuracy greater than ten times the system under test could be used to streamline the test. Additionally, owing to the nature of the test, a 3 DoF system can be elevated to a 6 DoF system if used to measure a circular path. The method therefore accommodates a greater range of potential reference systems, notably, a laser tracker. Assuming both the reference system and system under test can operate concurrently, and trigger events can be synchronised, certain sources of error could be eliminated.

2.7. Error Modelling

Table 4 provides a preliminary list of factors contributing to uncertainty on the reference values in the proposed static and dynamic tests for a horizontal path. Lines 4–5 and 13–14 are fixed offsets drawn once that can be minimised by calibration activities. Calibration is performed in a loaded state reducing error associated with flexure of the cantilevers due to the weight of the target constellations. Aerodynamic, humidity, electromagnetic interference, and environmental vibration are considered negligible influences (contribute < 1% of variance); however, they should be tracked and may be significant for certain technologies being tested. End-to-end latency is determined via the oscillation protocol phase error ; however, this currently assumes no temporal drift over the data collection window. Error due to temporal jitter can become significant even at modest speeds. The absence of a traceable absolute measure of time within the test is a significant limitation that is currently being addressed. Temporal errors, including skew and drift, are handled by the EtherCAT protocol but require close integration between the test apparatus and the system under test which may not be feasible. Additional factors such as packetisation and packet loss must be considered separately and are the focus of ongoing work. A separate error model is required for each degree of freedom; however, early estimations on positional accuracy suggest an achievable uncertainty (k = 2) of <30 µm. Work is ongoing to define the error model and apply uncertainty estimation via the Monte Carlo Method.

Table 4.

Sources of error contributing to reference value uncertainty for the proposed static and dynamic test when performed perpendicularly to the gravitational force vector.

It was noted in Section 2.5 that the achieved sample rate of ~6 Hz was significantly less than the expected 1000 Hz. Sample rate is a critical factor because it determines the temporal resolution of actuator position updates and directly influences spatial uncertainty during dynamic motion. At high speeds, coarse sampling intervals result in large positional gaps between recorded points, which cannot be fully corrected by interpolation. For example, at 3 m·s−1, a 170 ms update interval corresponds to ~500 mm of travel between samples, far exceeding the intended tens-of-micron accuracy target. Even with deterministic synchronisation, insufficient sampling frequency masks true latency and jitter effects and dominates the uncertainty budget in the temporal domain. If the sample rate was improved to 1 ms and synchronised to a traceable global time source, the travel between samples at 3 m·s−1 would reduce from ~500 mm to ~3 mm. Combined with deterministic timestamping, this should allow interpolation and error modelling to achieve the intended tens-of-micron uncertainty target, shifting dominant uncertainty contributions away from temporal discretisation toward artefact and actuator kinematics.

3. Results and Discussion

Preliminary results are presented based on data collected from a prototype artefact covering the minimal analysis related to each protocol. Analyses #1–3 are covered in this report. Analyses #4–6 will be covered in future publications. The system under test was an Iona system by InSphere. The Iona is not marketed as a dynamic measurement device but is technically capable to detecting moving targets.

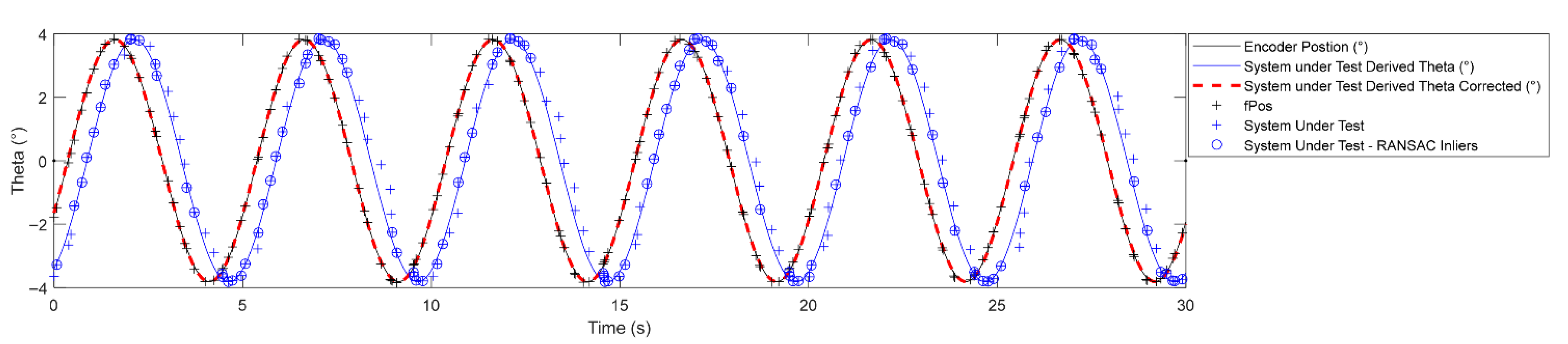

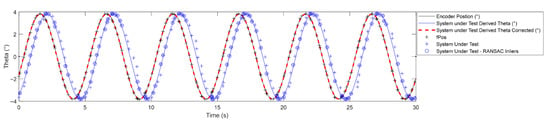

3.1. Analysis #1

Figure 5 shows the encoder feedback position and θ derived from pose information published by the system under test collected during Protocol 1, oscillation; 30 s out of 240 are shown. Fitting sine functions to the data allows an offset to be measured of Δt = −0.4963 ± 0.0038 (95% CI) seconds. This offset represents temporal latency between receipt at the DAQ of encoder output from the actuator and pose information from the system under test. Data was fitted robustly using the M-estimator sample consensus (MSAC) algorithm [35]. The confidence interval is estimated based on the combined uncertainty of the phase shift in the two fits. A −0.4963 s temporal offset is assumed constant and is used to align data collection in the subsequent protocols. Work is ongoing to improve temporal synchronisation and incorporate temporal uncertainty into the test metric. Regardless, Figure 5 illustrates how Protocol 1, oscillation, provides a data-driven method to detect temporal latency based on measured position using cross-correlation between measured signals.

Figure 5.

Plot of data collected during Protocol 1, oscillation, showing offset correction for temporal latency.

3.2. Analysis #2

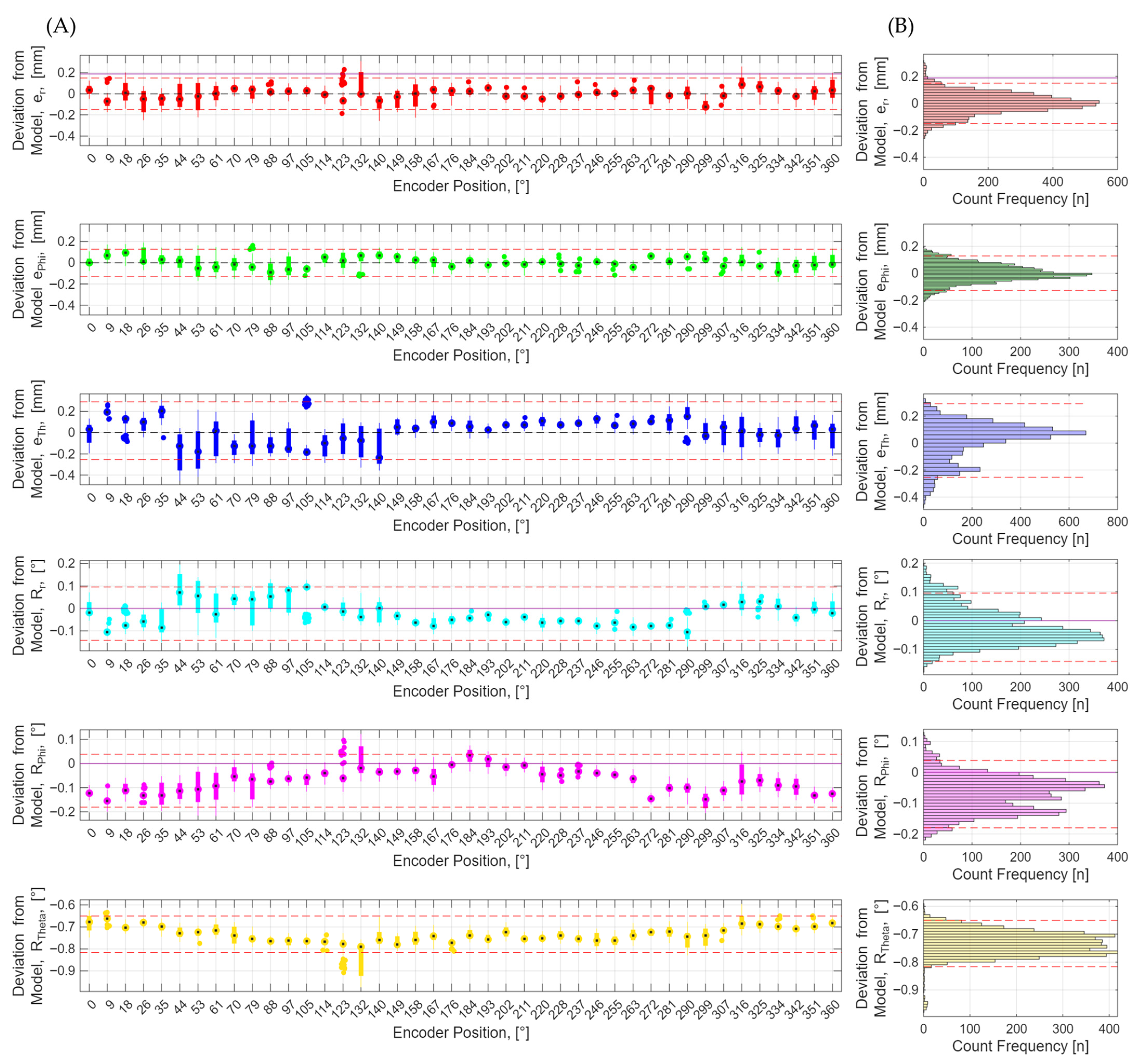

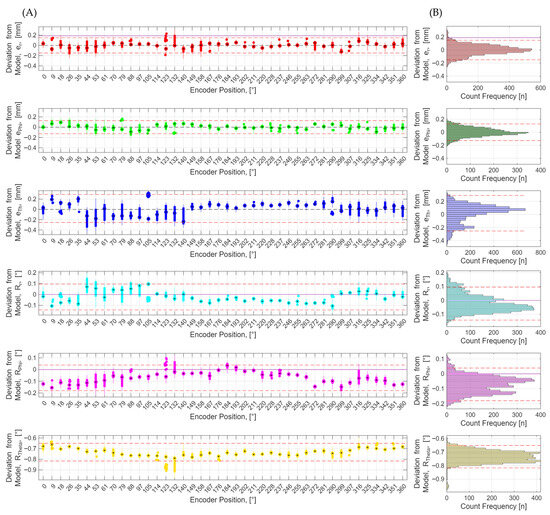

Data is collected using the stop-measure-move protocol and processed as previously described. Figure 6 shows the data for 42 points collected over a full rotation reported in the intrinsic coordinates of a fit circular path where points 1 (0°) and 42 (360°) are repeat points captured after one full rotation.

Figure 6.

Measurement output of the system under test in the intrinsic coordinates of the path in six degrees of freedom . Column (A) shows data plots against the discrete locations of the rotational encoder taken during the stop-measure-move protocol. Column (B) shows positions pooled together into a histogram with associated 95% confidence interval marked by the red hashed lines. The dots represent the median value, the box represents the upper and lower quartiles, the whiskers represent the range, and outliers are defined as 1.5 times the interquartile range above or below the edge of the box.

The positional data, [r, Φ, Θ], is well described by the circular model with each group median exhibiting a similar deviation from the fit circular path value of [0, 0, 0]. However, the radius, r, is approximately 0.2 mm smaller than the expected reference value. The orientational data, [Rr, RΦ, RΘ], is well described by a circular model; however, Rθ exhibits a bias with values centred around −0.72 degrees. There is good agreement between repeated points collected at angles 0° and 360° in both group mean values and variances across all degrees of freedom.

The deviations from expected reference values in r could be a scale error in the system under test or reference data. Alternatively, both r and Rθ could be explained by an increase in the deflection of the tubular body between calibration and test data capture activities or because of target displacement during transport of the artefact to the test location. Constellation B shows a similar bias in Rθ suggesting a systematic effect. Characterisation work is ongoing to measure the thermos–mechanical stability of the artefact and assign robust uncertainty to the reference values to improve confidence in the accuracy of the results thereby allowing for conclusions to be drawn explicitly on the performance of the system under test. Regardless, assuming the artefact is stable over the relatively short duration of the test (<1 h), the relative change in performance as a function of angular velocity is still valid.

Group median and group variance appear to structurally vary with location on the path potentially due to the changes in locoregional measurement conditions, e.g., sensor/target occlusion and/or sensor coverage. The measurability of any structural effects warrants more in-depth statistical analysis; however, it is first necessary to develop a robust uncertainty model on the reference path to determine if this is a detectable property of the system under test or a limitation of the test apparatus, calibration procedure, and/or path fit procedure. Ultimately, these structural effects, if deemed measurable, could be reported and/or compensated by the application of interpolation methods as previously discussed to better isolate motion effects over other volumetric errors. For simplicity the circular model is deemed adequate for this preliminary example and all groups will be pooled into summary statistics that describe the whole path.

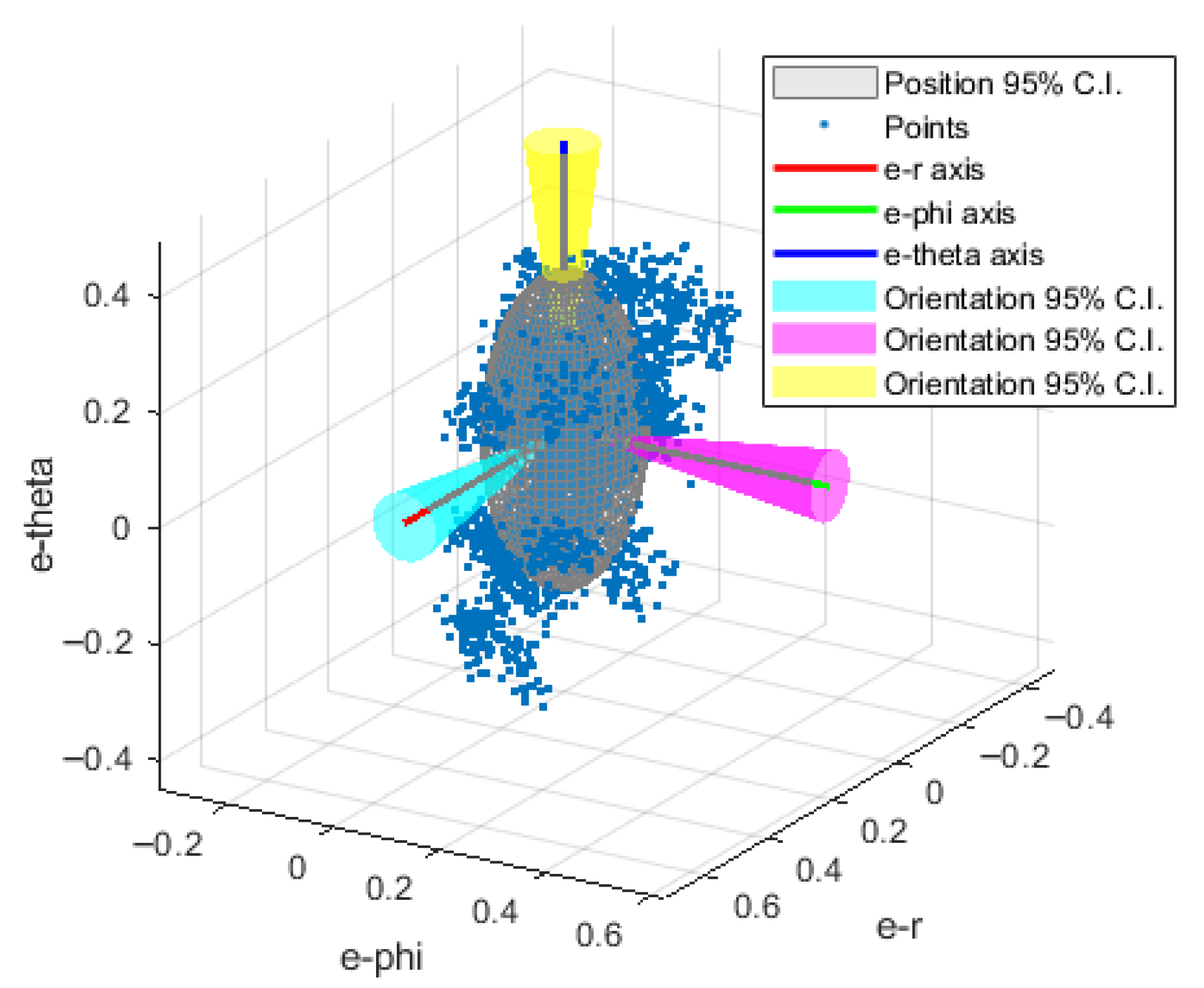

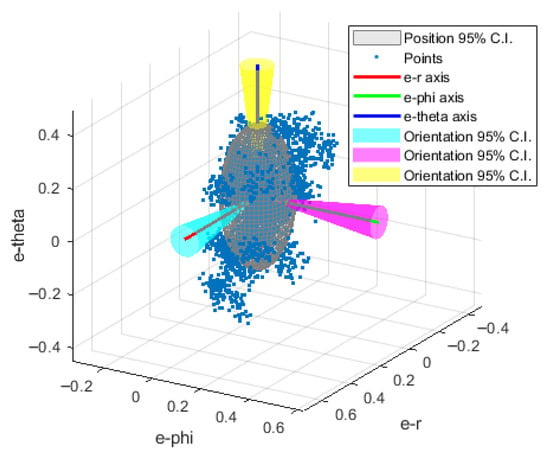

Figure 7 shows all data presented in Figure 6 pooled and reported in the intrinsic coordinates of the path. The 95% confidence interval is shown for all 6 DoF. The figure shows a succinct method to visualise position and orientation data to aid in intra- and inter-system comparison.

Figure 7.

System under test’s static 6 DoF measurement performance reported in the intrinsic coordinates of a circular path over one full rotation. The 95% confidence interval shown for the orientation has been multiplied by a factor of 100 to aid observation of both positional and orientation uncertainty at the same scale.

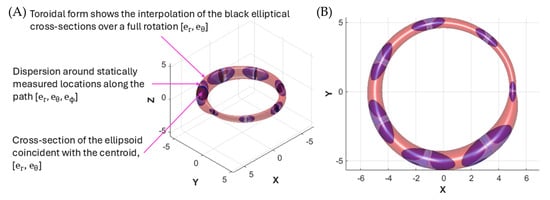

For illustrative purposes, Figure 8 shows the positional information of data collected at a single location plot relative to the path in the local coordinate frame of the artefact with the uncertainty bracket in er and eθ determined from all data points.

Figure 8.

The positional information of data collected at a single location, represented by the blue “*” markers and cyan triaxial ellipsoid, plot relative to the path determined from all data presented in the local coordinate frame of the artefact, represented by the solid red line, with the er and eθ components of the statically determined uncertainty bracket of the path represented by the cylindrical magenta mesh.

3.3. Analysis #3

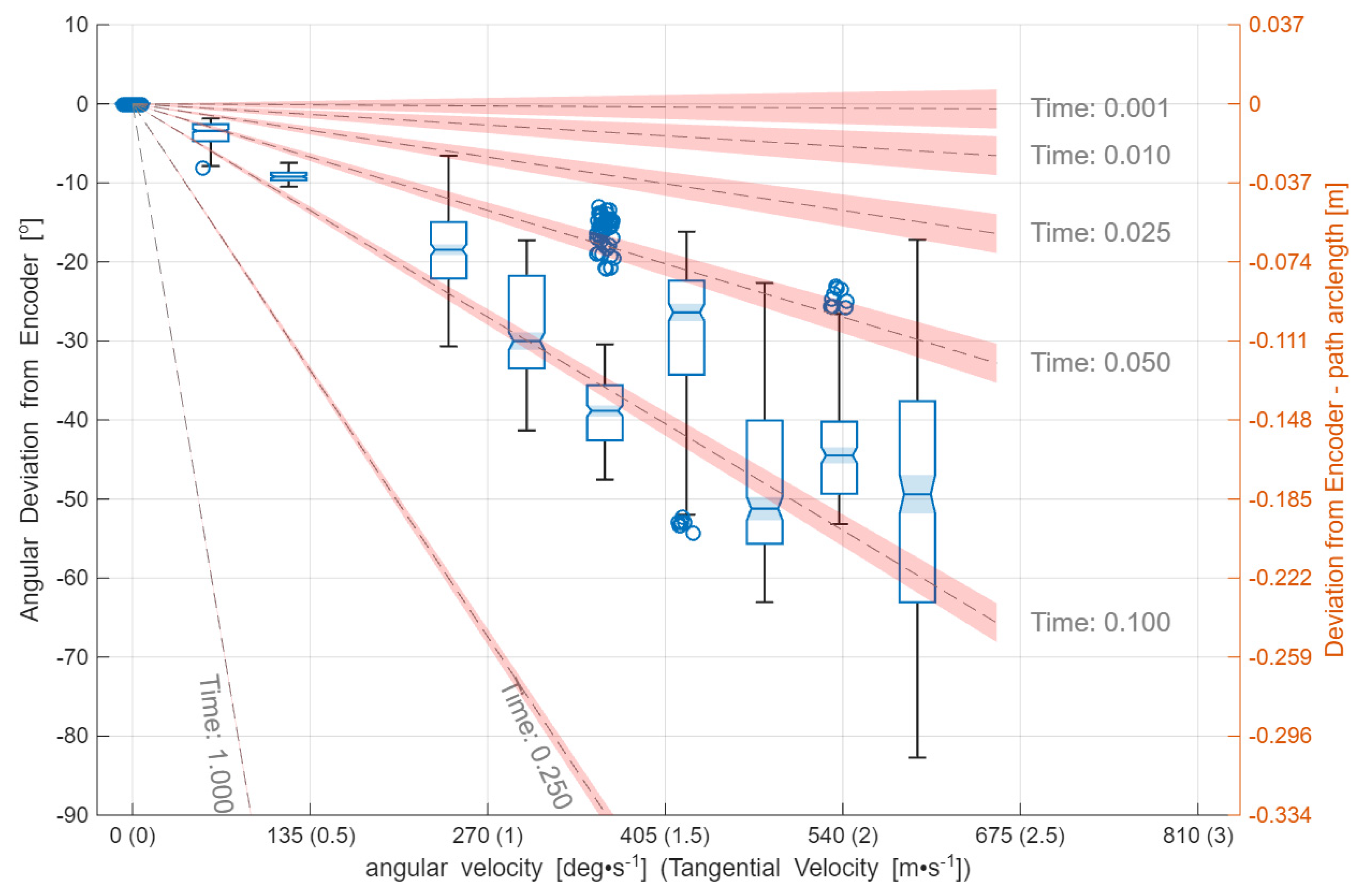

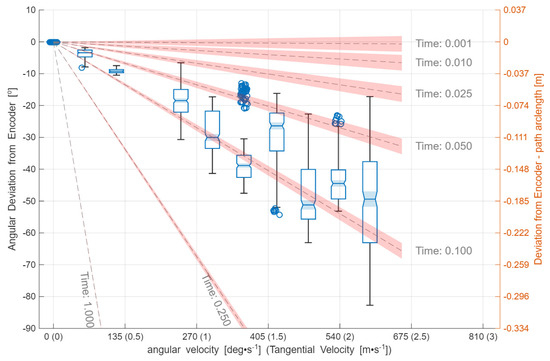

Figure 9 shows the angular deviation of the system under test from encoder values after constant latency correction obtained in Analysis #1, plotted as a function of discretely increasing angular speeds.

Figure 9.

Angular deviation between the path location reported by the system under test and the reference actuator encoder value, after applying the constant latency correction (Analysis #1), shown as a function of discretely increasing angular speed. The corresponding tangential velocity is reported alongside angular speed, and the right-hand axis expresses the angular deviation as an equivalent arc length along the path. Contours indicate the angular deviation expected for a given measurement delay; the contour uncertainty is denoted by the shaded area around each contour and reflects the ±0.0038 s (95% CI) uncertainty on the constant latency estimate from Analysis #1.

A residual, speed-dependent phase error remains: the deviation increases approximately linearly with angular speed, consistent with an additional effective time delay of ~0.06 s inferred from a linear fit to Figure 9. One plausible explanation is image-based integration effects (e.g., motion blur) if the exposure/integration period is of comparable magnitude. Other contributing mechanisms may include node synchronisation limits and temporal jitter within the system under test.

Regarding the system under test, it should be noted that it is not marketed as a dynamic measurement device and is not expected to deliver accurate pose at the highest tested speeds. Notably, the output timestamp was referenced to the control PC’s internal CMOS clock and the system was not disciplined to an external timing source (e.g., NTP/PTP), limiting absolute timing accuracy and potentially contributing to timestamp variability. Nevertheless, the system continued to detect the target constellation and report position and orientation up to 2.4 m·s−1, indicating that with system optimisation and improved temporal accuracy, improved dynamic performance may be achievable even at high speeds.

Interpretation of the residual delay and the observed increase in dispersion must be considered in the context of the current test infrastructure: the actuator position update rate was substantially lower than intended and there was no global source of time, so discretisation and interpolation effects remain a dominant limitation and restrict the extent to which latency and jitter can be deconvolved from pose error. Until these temporal limitations are reduced, full path-intrinsic spatial errors relative to the path determined in Analysis #2 are not reported, because they would primarily reflect end-to-end dynamic behaviour dominated by temporal discretisation rather than isolated pose-measurement performance. Full path-intrinsic spatial error maps will be reported in future work once actuator sampling and traceable timing are improved to enable robust separation of temporal and spatial contributions.

In addition to the apparent speed-dependent phase error, the dispersion in angular deviation increases with rotational speed. This behaviour is expected because timing uncertainty (e.g., synchronisation jitter and timestamp variability) maps into spatial uncertainty along the path with a sensitivity proportional to speed. While a detailed attribution of error mechanisms is beyond the scope of this paper, the result demonstrates the utility of the proposed methodology for reporting dynamic DLVM performance.

4. Conclusions

Existing standards such as ISO 10360, VDI/VDE 2634, ASME B89.4.19, and ASTM E2919-22/E3064 provide guidance for static or technology-specific measurements but lack a unified, technology-agnostic framework for dynamic evaluation of DLVM systems. This paper contributes a combined static–dynamic candidate methodology that defines path-intrinsic error metrics and a practical protocol structure and clarifies the spatial and temporal reference requirements needed to support future traceable, standardised implementation.

Initial trials with a multi-nodal distance-camera DLVM system demonstrate feasibility: the test exposed a constant latency of ~0.5 s, a velocity-dependent angular error equivalent to ~0.06 s additional latency at 2.4 m s−1, increasing variance as a function of speed, and spatially non-uniform dispersion around the reference path. These results illustrate how dynamic performance can be reported in the intrinsic coordinates of the path and referenced to a statically determined baseline. However, in the present prototype the actuator position update rate was substantially lower than intended, such that temporal discretisation dominates the dynamic uncertainty; consequently, full path-intrinsic spatial error maps relative to the static path are deferred until actuator sampling and traceable timing are improved. This outcome highlights the extent to which actuator sampling and traceable timing must be improved before a standard-ready separation of temporal and spatial contributions can be demonstrated.

Review of existing standards highlighted four distinct gaps; we have addressed each gap as follows:

- Gap 1—Technology agnosticism. By designing a generalisable geometric test defining performance in the intrinsic coordinates of the path and enabling both intra-system and inter-system comparison (including concurrent operation when feasible), the method decouples evaluation from specific instrument architectures and supports cross-technology benchmarking. It is however noted that calibration of specific targets/beacons depending on technology may be a complicating factor.

- Gap 2—Coherent static and dynamic characterisation. The methodology integrates three protocols: oscillation for latency/synchronisation, stop-measure-move for static path determination, and continuous motion for speed-dependent dynamic performance within a single framework, so dynamic outcomes are referenced to an internally consistent static baseline. Although not covered in detail the presence of two constellations allows the artefact to be used for relative pose measurements in line with ASTM E3064-16.

- Gap 3—Complex system/process variables. The artefact design accommodates reconfigurable target constellations and minimises self-occlusion, providing a practical baseline. We acknowledge that comprehensive coverage of occlusion patterns, sensor/target configurations, multi-target motion, and large workspaces is impractical solely via physical testing; thus, we propose virtualisation and modular extensions to broaden applicability.

- Gap 4—Industrial relevance and environmental realism. The method is conceived for in situ (re)verification and acceptance and explicitly considers environmental influence factors in the test design and uncertainty model. However, rigorous environmental robustness (temperature, ambient lighting, humidity, vibration) and high-rate temporal metrics (clock-skew, packet loss) remain open areas; we therefore commit to integrating formal environmental monitoring and a traceable ground-truth time source in future iterations to demonstrate industrial relevance at scale.

Despite current limitations in absolute time integration and restricted interoperability with systems not designed for dynamic measurement, the proposed methodology offers practical tools for benchmarking DLVM systems against task-specific accuracy and latency requirements. The prototype was scoped for tens-of-micron accuracy at high speeds, which may exceed the needs of applications prioritising either high speed with lower accuracy or vice versa; the device is intended primarily as a development aid for future solutions. The method is inherently scalable and tuneable to different industry requirements. However, widespread adoption will depend on three key advances: (i) rigorous uncertainty budgeting for the moving artefact across multiple orientations, (ii) integration of a robust, traceable timing source, and (iii) formal environmental monitoring combined with virtualisation to address occlusion-stress and multi-target scenarios. These areas are the focus of ongoing work. A dedicated follow-on publication will address temporal metrology in depth, including timestamp definition, traceable timing integration, and quantification of latency and jitter under high-frequency measurement.

Author Contributions

D.G., Supervision; Conceptualisation (lead); Methodology (lead); Writing—Original Draft (lead); Formal analysis (lead); Writing—Review and Editing (equal); Data Curation (supporting); Software (supporting). C.P., Investigation (lead); Writing—Original Draft (supporting); Data Curation (lead); Software (lead). M.C., Investigation (supporting); Methodology (supporting); Writing—original draft (supporting); S.J., Methodology (supporting), Software (supporting). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Innovate UK project Advanced Machinery & Productivity Initiative, Reference: 84646. https://gtr.ukri.org/projects?ref=84646 (accessed on 18 January 2026) and the National Measurement Service for the United Kingdom.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are preliminary and form part of an ongoing research programme. As such, they are not yet suitable for public dissemination. No publicly shareable dataset is available currently.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Centre for Precision Technologies at the University of Huddersfield for granting access to their robotic cell for testing and the Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre at the University of Sheffield in Cymru.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sitjongsataporn, S.; Paenoi, N. Development of Single-Arm Robots for Automotive Body Assembly Automation. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Power, Energy and Innovations (ICPEI 2023), Hua Hin, Thailand, 18–20 October 2023; pp. 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P. Implementing Advanced Robotics to Optimize Manufacturing Cycle Times in Automotive Production Lines. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2023, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, S. Engineering the Future: Robotics in the Automotive Industry Explained. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Manag. 2024, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfving, M.; Almström, P.; Jarebrant, C.; Wadman, B.; Widfeldt, M. Evaluation of flexible automation for small batch production. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 25, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilancia, P.; Schmidt, J.; Raffaeli, R.; Peruzzini, M.; Pellicciari, M. An Overview of Industrial Robots Control and Programming Approaches. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, E.R.; Saidi, K.S. Research Opportunities for Advancing Measurement Science for Manufacturing Robotics Research Opportunities for Advancing Measurement Science for Manufacturing Robotics; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Adebayo, R.A.; Obiuto, N.C.; Olajiga, O.K.; Festus-Ikhuoria, I.C. AI-enhanced manufacturing robotics: A review of applications and trends. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2023, 21, 2060–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonič, M.; Hrovat, M.M.; Džeroski, S.; Ude, A.; Nemec, B. Determining Exception Context in Assembly Operations from Multimodal Data. Sensors 2022, 22, 7962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Rab, S.; Suman, R. Significant applications of Cobots in the field of manufacturing. Cogn. Robot. 2022, 2, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitry, C.; Raj, H.; Wangchuk, S.; Madan, A.K. Extensive Review of Advancements in Telecommunications/Iot With Mems and Rf Passives. Int. Res. J. Mod. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2023, 5, 2582–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielis, J.; Shankar, A.; Prorok, A. A Critical Review of Communications in Multi-robot Systems. Curr. Robot. Rep. 2022, 3, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyle, D.; Hampton, L. 21St Century Progress in Computing. Telecomm. Policy 2023, 48, 102649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaweera, N.; Webb, P. Metrology-assisted robotic processing of aerospace applications. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2010, 23, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, R.P.; Strand, D.; Nilsson, M.; Collins, V.; Torstensson, J.; Kressin, J.; Spensieri, D.; Archenti, A. 3D Model-Based Large-Volume Metrology Supporting Smart Manufacturing and Digital Twin Concepts. Metrology 2023, 3, 29–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralikrishnan, B.; Phillips, S.; Sawyer, D. Laser trackers for large-scale dimensional metrology: A review. Precis. Eng. 2016, 44, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trends in Aerospace Assembly: Measurement Assisted Assembly. Available online: https://www.faro.com/en/Resource-Library/Article/trends-in-aerospace-assembly-introduction#:~:text=As%20we%20shall%20see%20in,less%20complexity%20and%20less%20cost (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Grant Agreement Number 17IND03 Project Short Name LaVA Project Full Title Large Volume Metrology Applications. Available online: http://empir.npl.co.uk/lava/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Franceschini, F.; Galetto, M.; Maisano, D.; Mastrogiacomo, L. Combining multiple Large Volume Metrology systems: Competitive versus cooperative data fusion. Precis. Eng. 2016, 43, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10360-2:2009; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Acceptance and Reverification Tests for Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMM)—Part 2: CMMs Used for Measuring Linear Dimensions. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2010.

- ISO 10360-10:2021; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Acceptance and Reverification Tests for Coordinate Measuring Systems (CMS)—Part 10: Laser Trackers. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2021.

- ISO 10360-12:2016; Geometrical Products Specifications (GPS)—Acceptance and Reverification Tests for Coordinate Measuring Systems (CMS)—Part 12: Articulated Arm Coordinate Measurement Machines (CMM). British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2016.

- ISO 10360-13:2021; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Acceptance and Reverification Tests for Coordinate Measuring Systems (CMS)—Part 13: Optical 3D CMS. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2021.

- VDI/VDE 2634; Optical 3D Measuring Systems—Part 1 Imaging Systems with Point-by-Point Probing. Verein Deutscher Ingenieure: Berlin, Germany, 2002.

- VDI/VDE 2634; Optical 3D Measuring Systems—Part 3 Multiple View Systems Based on Area Scanning. Verein Deutscher Ingenieure: Berlin, Germany, 2008.

- ASME B89.4.19-2006; Performance Evaluation of Laser Based Spherical Coordinate Measurement Systems. ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

- ASTM E2919-22; Standard Test Method for Evaluating the Performance of Systems That Measure Static, Six Degrees of Freedom (6DOF), Pose. ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–18. [CrossRef]

- ASTM E3064-16; Standard Test Method for Evaluating the Performance of Optical Tracking Systems that Measure Static, Six Degrees of Freedom (6DOF) Pose. ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–16. [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 18305:2016; Information Technology—Real Time Locating Systems—Test and Evaluation of Localization and Tracking systems. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2016.

- BS EN ISO 9283:1998; Manipulating Industrial Robots. Performance Criteria and Related Test Methods. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 1998.

- ISO 17123; Optics and Optical Instruments—Field Procedures for Testing Geodetic and Surveying Instruments. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2022.

- ISO 80000-2:2019; Quantities and Units—Part 2: Mathematics. BSI Standards Publication: London, UK, 2019.

- Cieslik, K.; Łopatska, M.J. Research on Speed and Acceleration of Hand Movements as Command Signals for Anthropomorphic Manipulators as a Master-Slave System. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, O.; Southon, N.; Meekums, P.; Davey, C.; Yu, N. Comparing performance evaluation methods for assessing an industrial robot tracking system. In Proceedings of the Lamda Map 2023, Laser Metrology and Machine Performance XV—15th International Conference and Exhibition on Laser Metrology, Coordinate Measuring Machine and Machine Tool Performance, Edinburgh, UK, 14–15 March 2023; pp. 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 230-7:2015; Test Code for Machine Tools—Part 7: Geometric Accuracy of Axes of Rotation. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2015. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/56624.html (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Torr, P.H.S.; Zisserman, A. MLESAC: A new robust estimator with application to estimating image geometry. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2000, 78, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.