Abstract

This literature review systematizes current data on the development of triploid seedless hybrids in the Cucurbitaceae Juss family. The absence of seeds simplifies the consumption and industrial preparation of products from cucurbits. In addition, triploids showed larger plant habitus, field resistance to infections, extended shelf life, and higher fruit quality. Phenotypic differences in polyploids can stem from altered chromatin organization and gene regulation, as the nucleus must accommodate a doubled chromosome set. The triploid watermelon cultivation method developed in 1951 failed to gain traction among other crops in the gourd (Cucurbitaceae) family. The challenges of triploid seed production and use include the need for the development of tetraploid and diploid parental lines, as well as bypassing the problem of the low viability of tetraploid parent pollen and the issue of thick seed coats and underdeveloped embryos in triploids. The research findings presented in this review can be applied to the development of triploid seedless hybrids for other members of the Cucurbitaceae family.

Keywords:

polyploidy; tetraploid; triploid; Citrullus lanatus; Cucurbita pepo; Cucumis sativus; Cucumis melo 1. Introduction

The Cucurbitaceae Juss family is the second largest among vegetable crops after Solanaceae and comprises about 1000 species, collectively referred to as cucurbits or gourds [1,2,3]. Based on world production, three genera—Cucumis (cucumbers, melons), Cucurbita (pumpkins, squash), and Citrullus (watermelons)—rank among the top 10 economically important vegetable crops worldwide [4]. Polyploidization is actively used for Cucurbitaceae breeding. This approach is often taken to expand the genetic diversity of the original breeding material. In cucurbits, polyploidization allows the production of tetraploid lines, which produce seedless triploid hybrids when crossed with diploid lines.

Triploid watermelons (Citrullus lanatus var. lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai) were first developed in the mid-20th century at Kyoto University in Japan [5]. Since then, this technology has been successfully implemented in commercial triploid watermelon production [6].

In addition to being seedless, triploid watermelons exhibit other advantageous characteristics. For instance, polyploid forms have been reported to show field resistance to Fusarium wilt [5], resistance to watermelon fruit blotch (Acidovorax citrulli) [7], enhanced resistance to nematodes in triploid watermelons [8], extended shelf life, and higher total soluble solids content [9]. However, the production of triploid watermelon seeds is a significantly more complex and costly process compared to that of diploid varieties and hybrids [5,10,11,12]. Despite these challenges in producing seedless watermelons, studies report not only higher economic profitability from their cultivation, but also their growing popularity [10,13].

Taste tests and consumer surveys have demonstrated significant market growth potential for triploid or seedless watermelons [10]. A survey revealed that consumers, when comparing the taste qualities of diploid-seeded watermelon varieties and seedless triploid hybrids, slightly preferred the latter and were willing to pay a higher price for them [10]. These factors have spurred the development of new triploid watermelon hybrids to meet rising consumer demand [14].

To our knowledge, there are no commercially available triploid hybrids of other popular vegetable crops in this family, such as zucchini (Cucurbita pepo var. giraumontias) and pattypan squash (C. pepo var. patisson, C. pepo var. melopepo). However, the production of a Coccinia grandis L. triploid hybrid, achieved by crossing a colchicine-induced tetraploid with a normal diploid parent, has been reported [15]. In our laboratory, we successfully produced a summer squash (C. pepo) triploid hybrid (unpublished data) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Triploid seedless summer squash (C. pepo) hybrid pollinated by diploid pollinator line. (A) Plant appearance, with two fruits at the end of the vegetative period. (B) Triploid female and male flowers. (C) Staminal column. (D) Pollen grains of the triploid hybrid that vary in size; (E). Cross-section of a mature seedless fruit.

The relevance of creating triploid seedless zucchini, pattypan squash, and pumpkins lies in the fact that the fruits of these crops are used for baby food, vegetable-based spreads (e.g., squash caviar), and, in the case of pumpkins and melons, juices and purees. Eliminating the need to remove seeds from the fruits would significantly simplify and reduce the cost of production technology for these products. Consequently, the development of tetraploids and triploids would not only diversify the original genetic pool but also create competitive polyploid lines and hybrids in demand by the canning industry.

2. Seedless Watermelon Technology Development and Commercialization

The first triploid (3n) seedless watermelon was developed in 1947 by Dr. Hitoshi Kihara, director of the Yokohama City University Kihara Institute for Biological Research [5,16,17]. Kihara H. was one of the first scientists to advocate for the active use of polyploidization as a tool in plant breeding. Noting that many popular Japanese varieties of oats, wheat, and strawberries were polyploids, his research demonstrated that induced polyploidization could address various breeding challenges in most agricultural crops [18].

Dr. Kihara H., in collaboration with Dr. Nishiyama I., conducted years of collaborative research on the morphology and inheritance of traits in triploid (3n) and tetraploid (4n) watermelon plants. These studies ultimately led to the successful production of a seedless fruit in a triploid watermelon hybrid. Following this breakthrough, it took an additional three years to develop a system for their commercial cultivation [19,20].

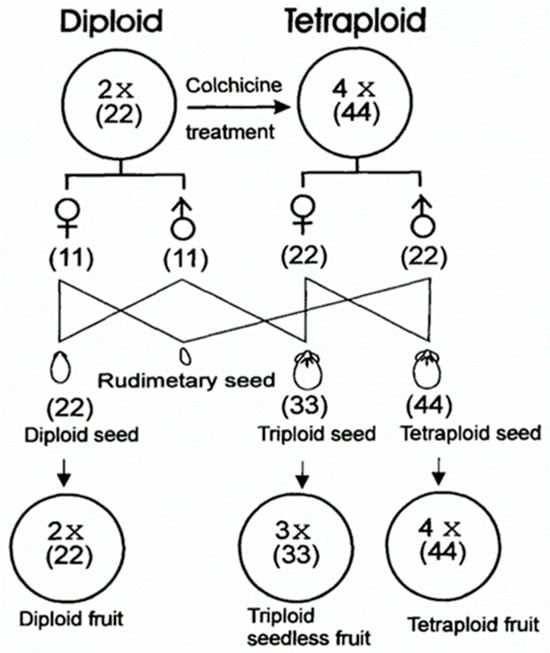

The process of creating triploid watermelons consists of several steps. The first step involves obtaining a tetraploid line (4n) of watermelon. To produce tetraploids, Hitoshi Kihara recommended treating diploid plants with colchicine (2 × 10−4 M to 6 × 10−2 M) for 48 h, following a previously published protocol [21]. After verifying ploidy in plants with confirmed doubled chromosome sets, self-pollination was conducted to generate seed progeny.

In the subsequent growing season, tetraploid (4n) plants were pollinated with diploid (2n) pollen from selected diploid lines (♀4n × ♂2n). Kihara’s experiments revealed that during reciprocal crosses using diploid lines as the maternal parent (♀2n × ♂4n), seeds either failed to develop or were malformed. Finally, in production settings, triploid plants grown in the following season were pollinated with diploid varieties (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Triploid seedless hybrid breeding scheme [5,22].

However, large-scale cultivation of triploid watermelon hybrids was not feasible at the time due to unresolved challenges, such as the low germination rate of tetraploid (4n) line seeds and the reduced number of seeds per fruit compared to diploid varieties. This resulted in higher production costs and market prices [23]. Industrial-scale production and commercialization only became viable by 1990 [24].

The introduction of seedless watermelons to US agricultural producers and consumers was largely driven by the efforts of two companies: American Sunmelon Seed Co. (Oklahoma City, OK, USA), which brought triploid seeds to market, and Sun World (Bakersfield, CA, USA), which launched a national marketing campaign in the late 1980s. At the time, the average price of seeds of traditional watermelon varieties was approximately USD 3 per 1000 seeds. Newer hybrid varieties cost USD 18–20 per 1000 seeds, while seedless watermelon seed pricing ranges from USD 150–200 per 1000 seeds. In addition, sowing triploid seeds using the same methods and quantities as diploid varieties was noted to increase expenses to USD 700–900 per 1000 seeds [10]. However, the high cultivation costs of triploid watermelons were offset by their high demand and premium pricing. Subsequent development of new triploid hybrids with improved seed germination rates and optimized cultivation techniques enhanced the profitability of seedless watermelon production [14,25,26,27].

The popularity of small-sized seedless watermelons among consumers and producers gradually captured a significant market share around the globe, including in the Americas, Asia, and Europe. For instance, the triploid watermelon market share in the United States rose from about 5% in the early 1990s to 85% in 2014 [13,28]. In China, seedless watermelons accounted for 20% of total watermelon production in 2005 [29], which rose to over 70% for consumers aged 25–35 in 2023 [30].

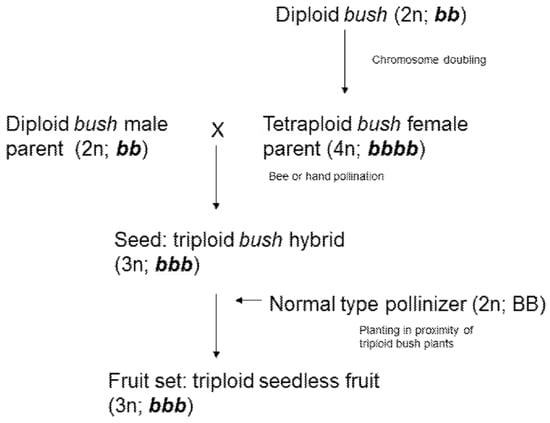

Open-source information includes registered and active patents related to the breeding and production of triploid watermelons. Examples include US20030172414A1 (USA), which patents an improved pollinator and the method to enhance seedless watermelon yield, and US7115800B2 (USA) that proposes a novel method to produce seedless watermelons with portion-sized fruits averaging less than 5 kg in weight. Notably, patent US10582683B2 describes the development of a seedless (3n) watermelon with a bush-type stem habit. This compact growth form simplifies fruit harvesting and plant maintenance. Below is the breeding scheme for producing seedless (3n) watermelons with this bush-type habit (Figure 3). The material was developed by Nunhems BV [31].

Figure 3.

Breeding scheme for producing triploid seedless watermelon: «b»—recessive “bush gene”; (bb) inbred diploid bush plants; (bbbb) inbred tetraploid (2n = 4x = 44) bush plants; (bbb) bush hybrid plants (according to the patent US10582683B2).

3. Morphological Characteristics of Polyploid Seeds and Methods for Promoting Germination

3.1. Morphological Characteristics of Polyploid Seeds

Seed production of triploid and tetraploid watermelon forms is challenging not only due to the extremely low number of fully developed seeds but also their low germination rate. The substantial air space in triploids also necessitates greater embryo enlargement before the radicle can penetrate the seed coat and emerge. Collectively, these issues significantly reduce the number of normally developed plants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Morphological characteristics of polyploid seeds in the Cucurbitaceae family.

3.2. Methods to Improve Germination in Polyploids

A number of methods were tested to address the poor germination of polyploid seeds. Scarification is widely used to enhance seed germination. This procedure aims to eliminate physical barriers to water uptake and gas diffusion while alleviating the mechanical restrictions on embryo growth. Although mechanical seed coat modification, such as scarification, notching, or lateral splitting, effectively improves triploid watermelon germination, integrating these pretreatment steps into production workflows has drawbacks, including the risk of embryo damage and increased labor time for seed processing [37]. This is why hydropriming is recommended as a method to enhance seed germination and germination vigor for industrial-scale applications. It represents a simple, effective, low-cost, and safe technique. Numerous studies on polyploid Cucurbitaceae confirm its efficacy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Methods that improve germination of polyploid seeds in the Cucurbitaceae family.

3.3. The Effect of Temperature on Germination of Polyploid Seeds

The germination of seeds, including those from polyploid forms, is influenced by numerous factors, with ambient air temperature and soil temperature being among the most critical. The optimal temperature range varies across species and can span a broad spectrum.

In the early 1950s, optimal soil temperatures for the germination of diploid seeds in Cucurbitaceae crops were established as ranging from 21 to 35 °C. A temperature of 35 °C was identified as optimal, while 15 °C and 40 °C were defined as the minimum and maximum thresholds, respectively [52].

When growing seedlings from polyploid watermelon seeds, it is crucial to select optimal temperatures to achieve uniform germination and ensure the development of compact seedlings without abnormally elongated hypocotyls. For instance, a study by Hassell R. L. et al. states that germination of triploid watermelon seeds necessitates maintaining temperatures between 29 and 32 °C for 24–48 h or until radicles emerge from the seed coat. On the other hand, some manufacturers recommend 24–38 °C for 24–72 h [52,53].

4. Growth, Development, and Pollination of Polyploid Pollen

When addressing the production of triploid plants, many research groups have encountered low viability of polyploid pollen grains in Cucurbitaceae species, such as watermelon [17,54] and melon [55].

In the study by Dumas de Vaulx, R., changes in diploid pollen germination and pollen tube growth were observed in tetraploid melons compared to haploid pollen in diploid samples; these changes included reduced viability, the formation of multiple pollen tubes, and the branching or hyper-development of pollen tubes within the ovule appear typical for polyploid plants [56].

A study on germinating tetraploid pollen revealed that while over two-thirds germinated normally, a small percentage released two, three, or four pollen tubes of normal size or a single bifurcated tube. Examination of some tetraploid pollen mother cells at the tetrad stage uncovered microsporocytes in addition to the four microspores. These anomalies in tetrad formation and the lower viability of tetraploid pollen were attributed to irregularities observed during meiosis. Despite the detected meiotic abnormalities, most tetraploid pollen remained viable. However, the authors suggested that these defects underlie the physiological self-sterility observed in tetraploids [57].

The slow growth rate of diploid pollen tubes in tetraploid watermelons during the later stages of germination, as observed by Dumas de Vaulx, may lead to haploid ovules losing their receptivity to fertilization by the time the pollen tubes reach them. This is corroborated by the significant increase in seed productivity of polyploid watermelons following the application of naphthaleneacetamide, a substance that prevents ovary degeneration, thereby enabling the slower diploid tubes to successfully fertilize the ovules [58].

The delayed growth of diploid pollen tubes does not appear to result from an inherent defect in the tube itself, as observed in self-pollination, but rather from a specific interaction with pistil tissues. Similar observations were documented in the work of Kishi and Fujishita. In their study on interspecific hybridization, which revealed incompatibility in this trait, pollen germinated on the stigma, and the pollen tube penetrated the pistil’s style. However, tube growth within the pistil tissues was significantly slower compared to self-pollination. Even 24, 48, or 72 h post-pollination, the pollen tube remained in the style, nearly ceasing growth, with some cases showing enlarged and branched tube tips. Furthermore, only a small number of flowers had pollen tubes that reached the ovary. Fertilized ovules were scarce, and most failed to develop [57].

The anomalies observed in diploid pollen germination and growth significantly impact the fertility of tetraploid plants. While diploid pollen grains are viable, the sterility observed is not absolute. This partial sterility may stem from minor cumulative changes that ultimately lead to a marked reduction in fertilization rates during pollination [55].

5. Morphology of Polyploid Plants

Multiple studies demonstrate that polyploidy results in enlarged morphological traits in polyploid forms compared to diploids (Table 3).

Table 3.

Morphological differences in polyploid forms of the Cucurbitaceae family.

Polyploidization also influences the biochemical composition of watermelon fruits. The comparison of seven tetraploid watermelon lines with their diploid parents revealed higher total β-carotene and lycopene levels in tetraploid fruits. Additionally, tetraploid fruits exhibited elevated fructose (5.43%) and glucose (2.38%) content [32]. The type and concentration of sugars impact the flesh coloration and sweetness. Lycopene, a primary carotenoid, contributes to the red pigmentation of watermelon flesh. Hence, these factors are critical biochemical determinants of fruit quality and marketability [61,62]. Consequently, tetraploid watermelons, characterized by enhanced sugar levels, could be utilized to develop triploid hybrids with superior taste profiles [10].

6. Genome Organization in Polyploid Plants

The tetraploid precursor of the triploid watermelon exhibits numerous phenotypic differences compared to its diploid counterparts. Although the causes of these differences are not fully understood, it is evident that genome duplication leads to chromatin reorganization and gene expression alterations that result in phenotypic changes [63] (Table 4).

Table 4.

The effects of polyploidization on gene expression and chromatin organization in different species.

The analysis of chromatin organization by the Hi-C chromosome conformation capture method, which identifies physical interactions between DNA regions, was performed on diploid and isogenic tetraploid watermelon plants [59]. This technique cross-links interacting chromatin fragments, fragments the DNA, ligates the interacting regions, and performs high-throughput sequencing. It was found that tetraploid chromosomes displayed increased interactions, particularly between regions of different chromosomes. Hi-C also showed that several chromosomal regions in tetraploid watermelon have switched Compartments A and B, which correspond to active euchromatin and inactive heterochromatin, respectively. Compartment switching occurred in 8% (B→A) and 1% (A→B) of the tetraploid genome, with B→A transitions representing the predominant change. Chromosomes 2 and 10 exhibited the highest frequency of B→A switching, while A→B transitions were primarily confined to chromosome 4 [59,70].

Chromatin organization also differed at finer scales. Within Compartments A and B, chromatin is structured into megabase-sized clusters called topologically associating domains (TADs). TADs are demarcated by boundaries that act as insulators, promoting frequent physical interactions among DNA sequences within the same TAD. The study identified TAD boundaries in diploid and tetraploid watermelons, finding that 93 out of 346 boundaries differed between the two lines [59]. The studies on watermelon and on other species also showed alternative splicing [69] and the differential methylation and acetylation patterns in polyploid plants [59,68].

The described genome and epigenome reorganization ultimately leads to significant gene expression changes that underlie the phenotypic differences between diploid and tetraploid plants [6,59].

7. Creation and Propagation of Polyploid Lines

Tetraploid maternal and diploid paternal lines are produced from diploid inbred lines or doubled haploid (DH) plants. DH-lines are fully homozygous lines produced from gametophytes. Haploid plants require genome doubling to produce diploids. Tetraploids are also produced by genome doubling from diploid plants. Artificial and spontaneous genome doubling approaches are described below.

7.1. Creation of Tetraploid Maternal Lines Using Antimitotic Substances

Colchicine is the most widely used agent for induced polyploidization. It is generally used in the range of concentrations from 0.1 to 2%. Generally, plant apexes and seeds are used for colchicine treatment (Table 5) [5,71,72,73,74,75,76]. For example, Kurtar E. S. published protocols for doubling haploid lines in cucurbit crops, specifically winter squashes (C. maxima), hard-shell pumpkins (C. pepo), and summer squashes (C. pepo). According to his protocols, apical shoots are treated after plant acclimatization (at the age of 4–5 weeks) by placing a cotton swab soaked in a 1% colchicine solution on the shoot tip. The cotton is then covered with aluminum foil to prevent the evaporation of the colchicine solution and protect against direct sunlight. This treatment is recommended three times daily, leaving the soaked cotton on the shoot for one hour each time, after which the apical shoot is rinsed three times with distilled water [77,78,79].

In addition to colchicine, genome doubling can also be induced by treatment with dinitroaniline compounds (ethalfluralin, oryzalin) [80,81,82]. In most published studies, the chromosome doubling frequency and tetraploid formation rate are less than 5% (Table 5) [57]. The best results were achieved in Citrullus lanatus using a 1.0% colchicine solution, which induced tetraploidy in 82.2% of plants [35]. Additionally, such treatments often produce mixed populations of diploids, tetraploids, aneuploids, and sectorial or periclinal chimeras [83].

Table 5.

Creation of tetraploid lines using antimitotic agents.

Table 5.

Creation of tetraploid lines using antimitotic agents.

| Plant | Mitotic Inhibitor | Concentration | Part Used | Observations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai | Colchicine, PEG | Colchicine (0.2%, 0.3% & 0.4%) PEG (0.5%) | plant shoots | 14.16% Colchicine 0.2% | [36] |

| colchicine | (0.0%, 0.1% & 0.2%) | seeds | - | [84] | |

| Colchicine; dinitroanaline | 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 & 2.0% colchicine; 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 & 2.0% (6-dinitroanaline) | - | Tetraploid induction 82.2% | [35] | |

| colchicine | 0.2% and 0.4% | plant shoots and seeds | 4 tetraploid plants | [85] | |

| colchicine | 0.3% colchicine | growth point | 35 tetraploid plants | [40] | |

| colchicine; dinitroanaline (ethalfluralin, oryzalin) | colchicine (100, 500, 1000, 1500 µM); dinitroanaline (5, 10, 50, 100 µM) | buds | ethalfluralin at 10 µM and dinitroaniline at 50 µM induced 50% tetraploids | [81] | |

| colchicine | 0, 0.05, 0.1, or 0.5% | seeds | polyploid induction was highest after treatment with 0.5% colchicine for 72 h | [86] | |

| colchicine | 0.2, 0.4, and 0.6% | the meristem of seedlings at true leaf emergence stage | 4–6% tetraploids | [87] | |

| colchicine | 0.2, 0.4, or 0.6% | seedlings | The recovery of tetraploids varied from 3.3 to 5.5% in various lines (to colchicine concentrations of 0.2%) | [88] | |

| colchicine | 0.1% & 0.2% | seeds; shoot apex; Inverted hypocotyl | 29.5% tetraploids (0.2% colchicine) | [76] | |

| colchicine | 0.2% | seeds | 2.7% tetraploids | [89] | |

| Dinitroaniline; colchicine | dinitroaniline solution (12, 14, or 15 mg/L); colchicine solution (300, 400, or 500 mg/L) | seedlings | 30.3 to 40.0% tetraploids (12 mg.L−1 of dinitroanaline for 24 h); 22.0 to 27.3% tetraploids (400 mg.L−1 of colchicine for 36 h) | [80] | |

| oryzalin | 50 mg/L | cotyledon | - | [41] | |

| colchicine | 0.2% | seedlings | - | [90] | |

| colchicine; oryzalin | colchicine (0.05, 0.10, 0.20, and 0.50%); oryzalin (5, 15, 30, and 60 µM) | seedlings | - | [82] | |

| Cucumis melo L. | colchicine | 0.4% | cotyledon stage | Chromosome doubling in haploid plants was achieved in 30% of the plants, 55% were mixoploids (n + 2n), and only 14% remained fully haploid | [91] |

| Momordica dioica Roxb. | colchicine | (0.01%, 0.05% & 0.1%) | sprouted tubers | 9 plants (6%) out of 150 were obtained by treatment with 0.1% colchicine solution for 10 h. | [33] |

| Cucumis melo L. | oryzalin | One-week-old seedlings were treated with 50 mg.L−1 of oryzalin; 10 µL | the shoot apex | 58 plants were identified as tetraploids | [42] |

7.2. Spontaneous Chromosome Doubling in Tissue Culture In Vitro

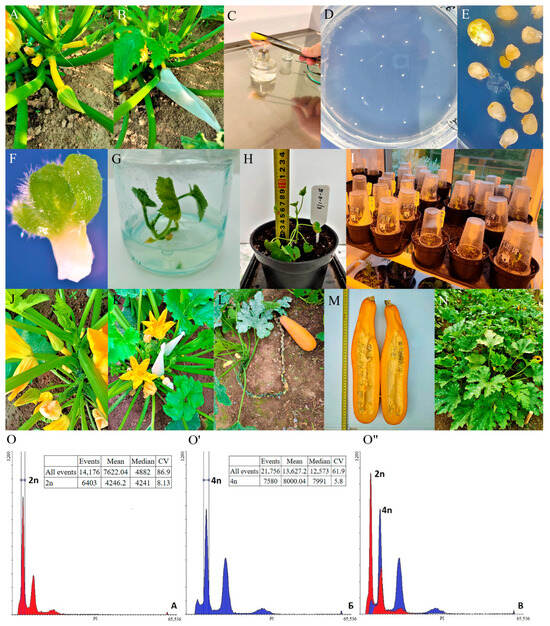

Spontaneous genome doubling in tissue culture provides an alternative method for producing doubled haploid and tetraploid plants (Figure 4), which may be more effective than colchicine treatment because of reducing the incidence of aberrant plants. This approach allowed us to obtain tetraploid summer and winter squash, as well as pattypan squash (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The production of doubled haploids in summer squash (C. pepo L.) plants in non-pollinated seedpod culture in vitro produces plants of different ploidy. (A) The female summer squash flower bud 1 day before flowering. (B) The isolation of female flower by paper cap. (C) Sterilization of an ovary by short-term burning. (D) The isolation of unpollinated ovules on IMC induction nutrient medium. (E) The formation of embryoids after 35–60 days of cultivation. (F) The embryoid that is ready to be transferred to MS regeneration nutrient medium. (G) The regeneration of a plantlet from the embryoid (microclonal multiplication is possible at this stage). (H,I) The adaptation of regenerant plants to ex vitro conditions. (J) The R0 regenerant plants in a film greenhouse. (K) The inbreeding of R0 regenerant plants. (L) The fruit’s development to the phase of biological ripeness. (M) A fruit with seeds from self-pollination; evaluation of internal structure of fruit. (N) Doubled haploid line for the next growing year [92]. (O–O”) Spontaneous tetraploid plants were revealed among summer squash regenerants using flow cytometry. (O) A standard diploid summer squash sample (2n = 2x = 40). External standardization was used. (O’) Tetraploid regenerant (2n = 4x = 80). (O”) Combined histogram of the diploid summer squash sample and the tetraploid sample. Mean—mean values of the peaks; CV—coefficient of variation in the peak [92].

However, the influence of factors such as genotype, nutrient medium, and hormones (cytokinins, auxins) exerts a strong effect on embryogenesis and genome doubling (Table 6). Depending on the aforementioned conditions, it is impossible to predict chromosome doubling in regenerant plants during in vitro culture.

Table 6.

Tetraploid line creation in in vitro culture.

Table 6.

Tetraploid line creation in in vitro culture.

| Plant | Culture Medium | Identified Polyploids | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cucumis melo L. | MS medium with 3% sucrose, 1 mg/L 2,4 dichlorophenoxy acetic acid (2,4-D), 2 mg/L naphthalene acetic acid (NAA), and 0.1 mg/L benzylaminopurine (BAP) | The frequency of tetraploid plants from somatic embryos and adventitious shoots was 31% and 30%, respectively | [93] |

| Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai | MS salts, plus (per liter) 30 g sucrose, 100 mg myo-inositol, 2 mg glycine, 0.5 mg pyridoxine HCI, 0.5 mg nicotinic acid, 0.1 mg thiamine HCI | The percentage of tetraploid regenerants varied from 5% to 20% | [94] |

| Cucumis melo L. | MS salts supplemented with B5 vitamins, 100 mg myoinositol/liter, 3% sucrose, and 5 μM benzylamino-purine (BAP) (+10 μM indole-3-acetic acid (IAA); +5 μM BAP). | >75% of the somaclonal variants were tetraploid | [95] |

| Winter squash (Cucurbita maxima Duch.) | MS medium with 30 g/L sucrose, (0.01 mg/L IAA; 0.5, 1 mg/L BAP + 0.25, 0.5, 1 mg/L TDZ) and 8 g/L agar | 4 tetraploid plants out of 122 plants | [96] |

| Honeydew melon (Cucumis melo L. inodorus) | M1 (MS basal + 1·mg L−1 BA), M2 (MS basal + 1·mg L−1 BA + 0.26·mg L−1 ABA), M3 (MS basal + 1·mg L−1 BA + 0.8·mg L−1 IAA), M4 (MS basal + 1·mg L−1 BA + 0.26·mg L−1 ABA + 0.8·mg L−1 IAA). | 17 plants (53.1%) appeared to be tetraploid or mixoploid (diploid + tetraploid or tetraploid + octoploid) | [97] |

| Melon (Cucumis melo L.) (cvs. Revigal, Topmark, and Kirkagac), and a cucumber (C. sativus L. cv. Taoz) | MS medium with 3% sucrose, MS vitamins, and 8 g·L−1 Agar | Regeneration from the cotyledons of the three melon cultivars resulted in 43% to 70% polyploid regenerants (All but one of the polyploid plants were tetraploid, the exception being an octaploid plant) | [98] |

| Winter squash (Cucurbita maxima Duch.) | MS medium supplemented with 1, 2, 5, or 10 mg/L BA. | The frequency of mixoploids increased with BA concentration in both cultivars. Of 213 adventitious shoots, 73.7% were diploid, 25.8% were mixoploid, and 0.5% were tetraploid. | [99] |

| Cucumis melo L. | MS medium containing 10 µM benzyladenine | Less than 50% of single bud-derived culture lines were mixoploid | [100] |

7.3. Spontaneous Polyploidization in Cucurbits Under Field Conditions

During the cultivation of cucumbers (Cucumis sativus L.) in a greenhouse and open fields, polyploid plants that deviate morphologically from the cultivated variety or the hybrid have been observed. This issue is particularly critical for greenhouse parthenocarpic cucumber production, where a single seed can cost over USD 1.

The occurrence of spontaneous polyploid cucumbers was first reported by Shifriss, who identified a tetraploid (4x) plant in a field of 25,000 plants (0.004%) [101,102]. In another study, a quantitative assessment of spontaneous polyploidy in cucumbers revealed 2.2% polyploids among 1422 plants. The study noted that polyploidization aligns with endoreduplication and is a continuous process during plant growth [103].

7.4. Ways to Produce Triploid Plants Besides Hybridization

Somatic hybridization through protoplast fusion allows the combination of complete parental genomes, overcoming reproductive barriers and creating allotetraploid hybrids with intermediate and novel traits. These serve as valuable breeding material [104]. Compared to conventional breeding and genetic engineering, somatic hybridization possesses the unique ability for simultaneous transfer of nuclear and cytoplasmic genes, including mono- and polygenic traits from incompatible species, bypassing genetic segregation [105]. In this specific case, triploids are obtained by fusing diploid protoplasts from one plant with haploid protoplasts from another [106].

In addition, the endosperm in vitro culture can be used for triploid production. The endosperm is a triploid tissue providing nutrition to the developing embryo. It is formed by the fusion of a haploid sperm nucleus with the two nuclei of the central cell of the embryo sac [107]. Due to its parenchymatous nature and lack of vascular tissues, the endosperm serves as a suitable explant for the in vitro regeneration of triploid plants via micropropagation [106,108].

7.5. Ploidy Determination Methods for Cucurbitaceae Crops

Treatments with antimitotic agents like colchicine or in vitro culture methods can generate different polyploids and chimeric plants.

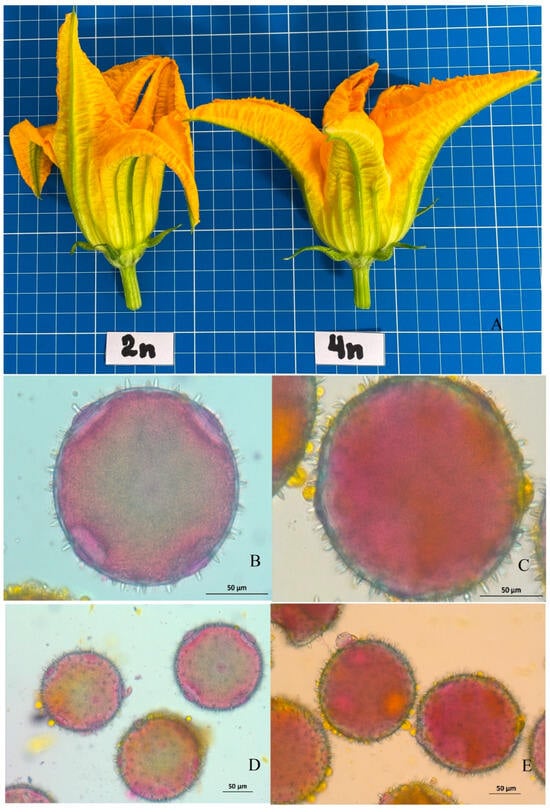

Ploidy confirmation can be performed by comparing pollen grain size. It is known that the pollen grain size in tetraploid watermelon is approximately 1.44 times larger than in diploids. Additionally, the pollen may have a higher number of pores/colpi (four instead of three) [9]. In our laboratory, the pollen grain size in the obtained tetraploid lines of zucchini and pattypan squash was approximately 1.5 times larger compared to the original donor diploid samples and doubled haploids (DH). We did not observe any differences in the number of pores (Figure 5) [9]. The number of chloroplasts per pair of guard cells also serves as a reliable indicator of plant ploidy [95]. Diploid, triploid, and tetraploid plants exhibit differences in key parameters of the abaxial epidermis: stomatal guard cell dimensions (width and length), stomatal density (number of stomata per mm2), and chloroplast count (per guard cell). However, environmental conditions can strongly influence abaxial epidermal traits such as stomatal guard cell size and stomatal density. Therefore, only the chloroplast count in stomatal guard cells is proposed as a meaningful indicator, serving as an indirect method for determining ploidy level.

Figure 5.

Male flowers of diploid and tetraploid summer squash (C. pepo), derived from the same genotype and grown under identical conditions. (A) Appearance of male flowers. (B,D) Mature pollen of the diploid. (C,E) Mature pollen of the tetraploid.

For example, studies report that in pattypan squash (C. pepo var. patisson) and zucchini (C. pepo var. melopepo), the average chloroplast counts in guard cells ranged from 9.41 to 11.31 for diploid samples, 14.84 to 16.3 for triploid samples, and up to 17.58 for tetraploid samples [109]. Studies revealed an average chloroplast count of 19.1 for tetraploid regenerants compared to 11.2 for diploid watermelon [94]. In another study, the chloroplast counts equaled 12 for diploid lines and 22.8 for tetraploid lines. Lines with chloroplast numbers ranging from 8 to 13–15 were classified as mixoploids, later confirmed by flow cytometry. Similar results were reported in a separate study, which observed 10–14 chloroplasts in diploid watermelon and 20–22 in tetraploids [82]. Chloroplast counting helped to identify tetraploid plants for crossing with diploid pollinators, thereby producing triploid hybrids [84,89,94].

The labor-intensive yet straightforward and cost-effective method of determining ploidy by counting chloroplasts in stomatal guard cells can serve as a preliminary screening tool to eliminate chimeric material and identify polyploids. However, it should be complemented by other, more precise ploidy assessment techniques, such as chromosome counting and flow cytometry [76,87], which assess chromosome number and nuclear DNA content, respectively. These are direct methods for determining ploidy, which avoid the ambiguity of morphological traits that may be confounded by the mixoploid nature of plants [55,88].

The assessment of ploidy is complicated by polysomaty—varying ploidy levels in somatic tissues. The endopolyploidy and polysomaty in C. sativus are continuous, sequential processes occurring at all developmental stages, from seed to flowering plant. Endogenous auxins and cytokinins play a significant role in this phenomenon [110]. The study revealed that 60% of nuclei in the leaves of the examined genotype were diploid (2n), while the remaining 40% were tetraploid (4n), octoploid (8n), and hexadecaploid (16n), indicating ongoing endoreduplication during development [110]. Polysomaty has also been documented in C. melo, C. pepo, and Citrullus vulgaris through the examination of the periblem (meristematic tissue) of primary and secondary root tips, as well as the stem apex and leaf primordia [111]. Since flow cytometry analyzes DNA staining intensity in thousands of nuclei, it serves as the quickest method to determine the true ploidy and the presence of polysomaty.

8. Conclusions

Triploid hybrid breeding is popular for different fruits, vegetables, and ornamental species, including watermelon, citrus, grape, mulberry, banana, sugar beet, poplar, and others. It gained popularity due to the improved characteristics it was able to produce, including nutritional value and the absence of seeds [106].

The development of Cucurbitaceae triploid seedless hybrids can also be used as a viable approach to improve agronomically valuable traits, including yield, nutritional value, and tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses. At the moment, the commercially successful seedless hybrids have been developed only for watermelon. Seedless watermelon hybrids continually demonstrate an increasing market share around the world. The commercialization and tremendous popularity of triploid hybrids became possible because a number of technical challenges were resolved, including the development of tetraploid lines, selection against sterility and abnormal fruit development in tetraploid lines, a parental line with a thin seed coat selection or overcoming thick seed coat-mediated germination issues, reduced seed productivity, decreased seed germination vigor, and the creation of efficient diploid pollinators.

Triploid watermelon gained commercial success because of the fruit’s anatomy. Diploid watermelons are more difficult to consume because of the seed distribution in the fruit. Therefore, the absence of seeds is extremely favorable for consumers. Other Cucurbitaceae species do not pose this problem since the seeds are accumulated in the center. However, seedless hybrids are often preferred by the canning industry since they reduce the number of steps required for fruit processing. Also, triploid hybrids can have improved qualities due to increased ploidy.

The development of triploid cantaloupe, pumpkin, cucumber, summer and pattypan squash, zucchini, and others will require the same issues that were reported for watermelon to be overcome. Currently, summer squash and Coccinia grandis prototype triploid hybrids have been developed that require further testing and commercialization.

Implementing advanced biotechnological tools alongside refined triploid production techniques will undoubtedly expand their potential in modern agriculture. Continued research and development in this field will unlock new applications for triploid production technology in other species. Future research on triploid plant production should focus on the incorporation of advanced breeding techniques (CRISPR-Cas9, improved chemical induction methods) for efficient polyploid generation.

The integration of omics approaches (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, genomics) will deepen our understanding of the genetic and molecular foundations of morphological differences observed in polyploids. Knowing the molecular mechanisms underlying polyploid morphological advantages compared to diploid counterparts would facilitate the development of stress-tolerant, nutritionally enhanced hybrids of different Cucurbitaceae crops.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E. and E.D.; investigation, A.E., M.F. and E.D.; resources, A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, A.E.; writing—review and editing, M.F. and E.D.; supervision, E.D.; funding acquisition, A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Russian Science Foundation (RSF) under research project No. 24-76-00062, https://rscf.ru/en/project/24-76-00062/, accessed on 3 December 2025.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in publicly accessible repositories and all the references have been provided in the Reference Section.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ma, L.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Guo, J.; Yuan, S.; Fu, A.; Bai, C.; Zhao, X.; Zheng, S.; Wen, C. Cucurbitaceae Genome Evolution, Gene Function, and Molecular Breeding. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhab057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yuan, M.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, S.; Hao, Y.; Ding, Y.; Gao, X.; Yu, Z.; Xu, Q. A Common Whole-Genome Paleotetraploidization in Cucurbitales. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 2430–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Xu, W.; Hu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Huang, C.-H.; Ma, H. Phylotranscriptomics in Cucurbitaceae Reveal Multiple Whole-Genome Duplications and Key Morphological and Molecular Innovations. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1117–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, A.A.; Paris, H.S. Melons, Squashes, and Gourds. Ref. Module Food Sci. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihara, H. Triploid Watermelons. Proc. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1951, 58, 217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Verhage, L. Diploid, Triploid, Tetraploid-Chromatin Organization in Polyploid Watermelon. Plant J. 2021, 106, 586–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garret, J.J.; Rhodes, B.B.; Zhang, X. Triploid Watermelons Resist Fruit Blotch Organism. Cucurbits Genet. Coop. Rep. 1995, 18, 56–57. [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo, A.E.; Esnard, J. Reaction of Ten Cultivars of Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) to a Puerto Rican Population of Meloidogyne Incognita. J. Nematol. 1994, 26, 640. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, B.; Zhang, X. Hybrid Seed Production in Watermelon. J. New Seeds 1999, 1, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, C.W.; Gast, K.L. Reactions by Consumers in a Farmers’ Market to Prices for Seedless Watermelon and Ratings of Eating Quality. HortTechnology 1991, 1, 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, M. Priming of Watermelon Seeds for Low-Temperature Germination. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1977, 102, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Sukprakarn, S.; Thongket, T.; Juntakool, S. Effect of Hydropriming and Redrying on the Germination of Triploid Watermelon Seeds. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2002, 36, 219–224. [Google Scholar]

- Karst, T. Seedless Watermelon Sure to Grow. Grower 1990, 23, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, D.N.; Elmstrom, G.W. Triploid Watermelon Production Practices and Varieties. II Int. Symp. Spec. Exot. Veg. Crops 1992, 318, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, K.S.; Rajan, S. A Promising Triploid of Little Gourd. J. Trop. Agric. 2001, 39, 162–163. [Google Scholar]

- Kihara, H.; Nlshiyama, I. An Application of Sterility of Autotriploids to the Breeding of Seedless Water Melons. Seiken Ziho 1947, 3, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kihara, H. Breeding of Seedless Fruits. Seiken Ziho 1958, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Crow, J.F. Hitoshi Kihara, Japan’s Pioneer Geneticist. Genetics 1994, 137, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, I. Studies on Artificial Polyploid Plants, I. Production of Tetraploids by Treatment with Colchicine. Am. J. Bot. 1939, 32, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, I.; Shimotsuma, M.; Yabuno, T. A Comparative Study of the Development of Polyploid Seed in the Water Melon. Seiken Zihô 1952, 5, 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Nebel, B.R. Mechanism of Polyploidy through Colchicine. Nature 1937, 140, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-H.; Liang, N.N. The Discovery of the Breeding of Seedless Watermelon. In Discoveries in Plant Biology: Volume II; World Scientific: Singapore, 1998; pp. 349–367. [Google Scholar]

- Hassell, R.L.; Schultheis, J.R. Seedless Watermelon Transplant Production Guidelines 2004. Available online: https://scholar.google.co.uk/scholar?hl=zh-TW&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Seedless+Watermelon+Transplant+Production+Guidelines&btnG= (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Maynard, D.N. Watermelons: Characteristics, Production, and Marketing; ASHS Press: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Motsenbocker, C.E.; Arancibia, R.A. In-Row Spacing Influences Triploid Watermelon Yield and Crop Value. HortTechnology 2002, 12, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NeSmith, D.S.; Duval, J.R. Fruit Set of Triploid Watermelons as a Function of Distance from a Diploid Pollinizer. HortScience 2001, 36, 60–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, S.A. Honey Bee Pollination Requirements for Triploid Watermelon. HortScience 2005, 40, 1268–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watermelon|Agricultural Marketing Resource Center. Available online: https://www.agmrc.org/commodities-products/fruits/watermelon (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Liu, W.G. Review and Perspectives of Scientific Research and Production Cooperation of Seedless Watermelon in China. China Watermelon Melon 2005, 2, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kaseb, M.O.; Umer, M.J.; Lu, X.; He, N.; Anees, M.; El-Remaly, E.; Yousef, A.F.; Salama, E.A.; Kalaji, H.M.; Liu, W. Comparative Physiological and Biochemical Mechanisms in Diploid, Triploid, and Tetraploid Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus L.) Grafted by Branches. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Groot, E.; Chiapparino, E.; Berentsen, R.B. Triploid Watermelon Plants with a Bush Growth Habit. 2020. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/EP2814316A1/en?oq=+EP+2814316 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Jaskani, M.J.; Kwon, S.W.; Kim, D.H. Comparative Study on Vegetative, Reproductive and Qualitative Traits of Seven Diploid and Tetraploid Watermelon Lines. Euphytica 2005, 145, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirala, D.; Tiwari, J.K.; Sahu, N.K.; Sinha, S.K. Morphological and Physiological Changes (Variation) in Colchicine Induced Tetraploids of Spine Gourd (Momordica dioica Roxb.) in Comparison to Their Diploid Counterparts. Plant Physiol. Rep. 2023, 28, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adıgüzel, P.; Solmaz, İ.; Karabıyık, Ş.; Sarı, N. Comparison on Flower, Fruit and Seed Characteristics of Tetraploid and Diploid Watermelons (Citrullus Lanatus Thunb. Matsum. and Nakai). Int. J. Agric. Environ. Food Sci. 2022, 6, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.A.; Min, K.H.; Choi, Y.S.; Park, S.B.; Kim, Y.C.; Cho, S.M. Development of Tetraploid Watermelon Using Chromosome Doubling Reagent Treatments. Korean J. Plant Resour. 2015, 28, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirveedi, V.K. Standardization of Techniques for Induction of Tetraploidy in Watermelon (Citrullu slanatus Thunb.). Master’s Thesis, Dr. Y.S.R. Horticultural University, West Godavari, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, T.V.; Ashok, P.; Rao, E.S.; Sasikala, K. Studies to Improve Seed Germination in Tetraploids Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus Thunb.). Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2014, 4, 341. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin, A.; Yetişir, H. A Comparative Study of Morphological Characteristics in Diploid and Tetraploid (Auto and Allotetraploids) Citrullus Genotypes. Folia Hortic. 2023, 35, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grange, S.L.; Leskovar, D.I.; Pike, L.M.; Cobb, B.G. Excess Moisture and Seedcoat Nicking Influence Germination of Triploid Watermelon. HortScience 2000, 35, 1355–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Bao, Y.; Xie, Z.; Huang, X.; Sun, Y.; Feng, G.; Zeng, H.; Ren, J.; Li, Y.; Xiong, J.; et al. Efficient Characterization of Tetraploid Watermelon. Plants 2019, 8, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Bi, Z.; Fu, D.; Feng, L.; Min, D.; Bi, C.; Huang, H. A Comparative Study of Morphology, Photosynthetic Physiology, and Proteome between Diploid and Tetraploid Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus L.). Bioengineering 2022, 9, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.-Y.; Deepo, D.M.; Islam, M.M.; Nam, S.-C.; Kim, H.-Y.; Han, J.-S.; Kim, C.-K.; Chung, M.-Y.; Lim, K.-B. Induction of Polyploidy in Cucumis melo ‘Chammel’ and Evaluation of Morphological and Cytogenetic Changes. HST 2021, 39, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grange, S.; Leskovar, D.I.; Pike, L.M.; Cobb, B.G. Seedcoat Structure and Oxygen-Enhanced Environments Affect Germination of Triploid Watermelon. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2003, 128, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunarlim, N.; Zam, S.I.; Purwanto, J. Pelukaan Benih Dan Perendaman Dengan Atonik Pada Perkecambahan Benih Dan Pertumbuhan Tanaman Semangka Non Biji (Citrullus vulgaris Schard L.). J. Agroteknologi 2012, 2, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pandya, J.B.; Mehta, K.J.; Patale, V.V. Germination Treatments for Watermelon Seeds. Biosci. Guard. 2012, 2, 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Duval, J.R.; NeSmith, D.S. Treatment with Hydrogen Peroxide and Seedcoat Removal or Clipping Improve Germination of `Genesis’ Triploid Watermelon. HortScience 2000, 35, 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerson, H.; Paris, H.S.; Karchi, Z.; Sachs, M. Seed Treatments for Improved Germination of Tetraploid Watermelon. HortScience 1985, 20, 897–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, J.R.; NeSmith, D.S. Emergence of ‘Genesis’ Triploid Watermelon Following Mechanical Scarification. J. -Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1999, 124, 430–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phat, P.; Sheikh, S.; Lim, J.H.; Kim, T.B.; Seong, M.H.; Chon, H.G.; Shin, Y.K.; Song, Y.J.; Noh, J. Enhancement of Seed Germination and Uniformity in Triploid Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. and Nakai). Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2015, 33, 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Malik, A.; Dalal, P.K.; Raj, M.P. Impact of Hydropriming on Fresh and Naturally Aged Seeds of Bottle Gourd (Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl). Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2022, 41, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phat, P.; Ju, H.-J.; Noh, J.; Lim, J.; Seong, M.; Chon, H.; Jeong, J.; Kwon, S.; Kim, T. Effects of Hydropriming and Explant Origin on in Vitro Culture and Frequency of Tetraploids in Small Watermelons. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2017, 58, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, J.F.; Minges, P.A. Vegetable Seed Germination. Bot. Gaz. 1954, 115, 205–225. [Google Scholar]

- Hassell, R.L.; Dufault, R.J.; Phillips, T.L. Influence of Temperature Gradients on Triploid and Diploid Watermelon Seed Germination. HortTechnology 2001, 11, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.K.; Roy, R.P.; Mishra, D.P. Artificial Triploids in Luffa Echinato Roxb. Cytologia 1979, 44, 739–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susiacue;n, I.; Álvarez, J.M. Fertility and Pollen Tube Growth in Polyploid Melons (Cucumis melo L.). Euphytica 1997, 93, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas de Vaulx, R. Etude Des Possibilités d’utilisation de La Polyploidie Dans l’amélioration Du Melon (Cucumis melo L.). Ann. L’amélioration Plantes 1974, 24, 389–403. [Google Scholar]

- Lower, R.L.; Johnson, K.W. Observations on Sterility of Induced Autotetraploid Watermelons. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1969, 94, 367–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoner, A.K.; Johnson, K.W. Overcoming Autosterility of Autotetraploid Watermelons. Proc. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1965, 86, 621–625. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Lozano, M.; Natarajan, P.; Levi, A.; Katam, R.; Lopez-Ortiz, C.; Nimmakayala, P.; Reddy, U.K. Altered Chromatin Conformation and Transcriptional Regulation in Watermelon Following Genome Doubling. Plant J. 2021, 106, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; He, N.; Anees, M.; Yang, D.; Kong, W.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, L.; Luo, X.; Zhu, H.; Liu, W. A Comparison of Watermelon Flesh Texture across Different Ploidy Levels Using Histology and Cell Wall Measurements. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutton, L.L.; Cullis, B.R.; Blakeney, A.B. The Objective Definition of Eating Quality in Rockmelons (Cucumis melo). J. Sci. Food Agric. 1981, 32, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, T.; Abe, K.; Sanada, T.; Yamaki, S. Levels and Role of Sucrose Synthase, Sucrose-Phosphate Synthase, and Acid Invertase in Sucrose Accumulation in Fruit of Asian Pear. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1992, 117, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, E.S.; Liu, C. Three-Dimensional Chromatin Packing and Positioning of Plant Genomes. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.J.; Potter, B.I.; Doyle, J.J.; Coate, J.E. Gene Balance Predicts Transcriptional Responses Immediately Following Ploidy Change in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 1434–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, D.; Tong, C.; Ge, X.; Liu, S.; Li, Z. Gene Expression Changes during the Allo-/Deallopolyploidization Process of Brassica Napus. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.; Chen, Z.J. Genomic and Expression Plasticity of Polyploidy. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchler, J.A.; Veitia, R.A. Gene Balance Hypothesis: Connecting Issues of Dosage Sensitivity across Biological Disciplines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 14746–14753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Kim, E.-D.; Ha, M.; Lackey, E.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Chen, Z.J. Altered Circadian Rhythms Regulate Growth Vigour in Hybrids and Allopolyploids. Nature 2009, 457, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, H.; Liu, Z.; Zou, J.; Meng, J.; Wang, J. Genome-Wide Analysis of Alternative Splicing Divergences between Brassica Hexaploid and Its Parents. Planta 2019, 250, 603–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaburn, K.J.; Misteli, T. Chromosome Territories. Nature 2007, 445, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, K.; Nukaya, T.; Sudo, M.; Yahata, M.; Tominaga, A.; Mukai, H.; Kunitake, H. Effects of in Vitro Colchicine Treatment on Tetraploid Induction in Seeds of Polyembryonic Cultivars of the Genera Citrus, Fortunella, and Poncirus. Trop. Agric. Dev. 2022, 66, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Wu, J.; Sang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, P.; Liu, M. Effects of Colchicine on Populus Canescens Ectexine Structure and 2n Pollen Production. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eigsti, O.J.; Dustin, P., Jr.; Gay-Winn, N. On the Discovery of the Action of Colchicine on Mitosis in 1889. Science 1949, 110, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernice, B. Sulla Cariocinesi Delle Cellule Epiteliali e Dell’endotelio Dei Vasi Della Mucosa Dello Stomaco e Dell’intestino, Nello Studio Della Gastroenterite Sperimentale (Nell’avvelenamento per Colchico). Sicil. Med. 1889, 1, 265–279. [Google Scholar]

- Andrus, C.F. Production of Seedless Watermelons; US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1971.

- Noh, J.; Sheikh, S.; Chon, H.G.; Seong, M.H.; Lim, J.H.; Lee, S.G.; Jung, G.T.; Kim, J.M.; Ju, H.-J.; Huh, Y.C. Screening Different Methods of Tetraploid Induction in Watermelon [Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Manst. and Nakai]. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2012, 53, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtar, E.S.; Seymen, M. Anther Culture in Cucurbita Species. In Doubled Haploid Technol.: Vol. 3: Emerg. Tools, Cucurbits, Trees, Other Species; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtar, E.S.; Seymen, M. Gynogenesis in Cucurbita Species. In Doubled Haploid Technol.: Vol. 3: Emerg. Tools, Cucurbits, Trees, Other Species; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtar, E.S.; Seymen, M. Induction of Parthenogenesis by Irradiated Pollen in Cucurbita Species. In Doubled Haploid Technol.: Vol. 3: Emerg. Tools, Cucurbits, Trees, Other Species; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Omran, S.A.; Guerra-Sanz, J.M.; Cardenas, J.G. Methodology of Tetraploid Induction and Expression of Microsatellite Alleles in Triploid Watermelon. In Proceedings of the Proceedings IXth Eucarpia meeting on genetics and breeding of Cucurbitaceae, Avignon, France, 21–24 May 2008; pp. 381–384. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Whitesides, J.F.; Rhodes, B. In Vitro Generation of Tetraploid Watermelon with Two Dinitroanilines and Colchicine. Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, G.-C. Tetraploid Production of Moodeungsan Watermelon. J.-Korean Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2002, 43, 671–676. [Google Scholar]

- McCuistion, F.; Elmstrom, G.W. Identifying Polyploids of Various Cucurbits by Stomatal Guard Cell Chloroplast Number. Proc. Fla. State Hortic. Soc. 1993, 106, 155–157. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, C.M.D.J.; Dias, R.D.C.S.; Santos, J.S.D.; Souza, F.D.F.; Melo, N.F.D. Induction of Polyploidy in Watermelon Genotype with Powdery Mildew Resistance (Podosphaera xanthii). Rev. Caatinga 2022, 35, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswat, A.; Hayati, P.D. Penampilan Morfologi Dan Sitologi Tanaman Semangka (Citrullus lanatus Thunb.) Hasil Induksi Senyawa Kolkisin. Jagur J. Agroteknologi 2025, 7, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.-E.-A.; Hassan, J.; Biswas, M.S.; Khan, H.I.; Sultana, H.; Suborna, M.N.; Rajib, M.M.R.; Akter, J.; Gomasta, J.; Anik, A.A.M. Morphological and Anatomical Characterization of Colchicine-Induced Polyploids in Watermelon. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2023, 64, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskani, M.J.; Kwon, S.W.; Kin, D.H. Flow Cytometry of DNA Contents of Colchicine Treated Watermelon as a Ploidy Screening Method at MI Stage. Pak. J. Bot. 2005, 37, 685. [Google Scholar]

- Jaskani, M.J.; Kwon SungWhan, K.S.; Koh GabCheon, K.G.; Huh YunChan, H.Y.; Ko BokRai, K.B. Induction and Characterization of Tetraploid Watermelon. J. Korean Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2004, 45, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, F.d.F.; Queiroz, M.d.A.; Dias, R.d.C.S. Desenvolvimento de Híbridos Triplóides Experimentais de Melancia. Sitientibus Série Ciências Biológicas 2001, 1, 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Zhao, S.; Lu, X.; He, N.; Gao, L.; Dou, J.; Bie, Z.; Liu, W. Genome Duplication Improves the Resistance of Watermelon Root to Salt Stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 133, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, S. Induced Tetraploidy in Muskmelons. J. Hered. 1952, 43, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolaev, A.S.; Domblides, E.A. Optimization of Steps in the Technology of Obtaining Doubled Haploids of Summer Squash (Cucurbita Pepo L.) in the Culture of Unpollinated Ovules in Vitro. Veg. Crops Russ. 2022, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezura, H.; Amagai, H.; Yoshioka, K.; Oosawa, K. Highly Frequent Appearance of Tetraploidy in Regenerated Plants, a Universal Phenomenon, in Tissue Cultures of Melon (Cucumis melo L.). Plant Sci. 1992, 85, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, M.E.; Gray, D.J.; Elmstrom, G.W. Identification of Tetraploid Regenerants from Cotyledons of Diploid Watermelon Cultured in Vitro. Euphytica 1996, 87, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassuliotis, G.; Nelson, B.V. Regeneration of Tetraploid Muskmelons from Cotyledons and Their Morphological Differences from Two Diploid Muskmelon Genotypes. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1992, 117, 863–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtar, E.S.; Balkaya, A.; Kandemir, D. A Productive Direct Regeneration Protocol for a Wide Range of Winter Squash (Cucurbita maxima Duch.) and Pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch.) Lines. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020, 25, 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Bang, H.; Gould, J.; Rathore, K.S.; Patil, B.S.; Crosby, K.M. Shoot Regeneration and Ploidy Variation in Tissue Culture of Honeydew Melon (Cucumis melo L. Inodorus). Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. -Plant 2013, 49, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curuk, S.; Ananthakrishnan, G.; Singer, S.; Xia, X.; Elman, C.; Nestel, D. Regeneration in Vitro from the Hypocotyl of Cucumis Species Produces Almost Exclusively Diploid Shoots, and Does Not Require Light. HortScience 2003, 38, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Chung, W.I.; Ezura, H. Efficient Plant Regeneration via Organogenesis in Winter Squash (Cucurbita maxima Duch.). Plant Sci. 2003, 164, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelberg, J.W.; Rhodes, B.B.; Skorupska, H.T. Generating Tetraploid Melons in Tissue Culture. In Proceedings of the II International Symposium on In Vitro Culture and Horticultural Breeding 336, Baltimore, MD, USA, 28 June–2 July 1992; pp. 373–380. [Google Scholar]

- Grimbly, P.E. Polyploidy in the Glasshouse Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Euphytica 1973, 22, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifriss, O. Polyploids in the Genus Cucumis. J. Hered. 1942, 33, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Madera, A.O.; Miller, N.D.; Spalding, E.P.; Weng, Y.; Havey, M.J. Spontaneous Polyploidization in Cucumber. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2017, 130, 1481–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.-J.; Yun, S.-H.; Park, S.-M.; Jin, S.-B.; Song, K.-J. Characterization of Allotetraploids Derived from Protoplast Fusion between Navel Orange and Kumquat. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2020, 56, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokka, V.-M. Protoplast Technology in Genome Manipulation of Potato Through Somatic Cell Fusion. In Somatic Genome Manipulation; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 217–235. ISBN 978-1-4939-2389-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan, R.; Banadka, A.; Dubey, S.; Al-Khayri, J.M.; Nagella, P. Advances in Triploid Plant Production: Techniques, Benefits, and Applications. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 2025, 160, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, N.T.; Silva, L.A.S.; Reis, A.C.; Machado, M.; de Matos, E.M.; Viccini, L.F.; Otoni, W.C.; de Carvalho, I.F.; Rocha, D.I.; da Silva, M.L. Endosperm Culture: A Facile and Efficient Biotechnological Tool to Generate Passion Fruit (Passiflora Cincinnata Mast.) Triploid Plants. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 2020, 142, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, Z.-M.; Zhi, S.; Xu, F. Breeding Triploid Plants: A Review. Czech J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2016, 52, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domblides, E.; Ermolaev, A.; Belov, S.; Kan, L.; Skaptsov, M.; Domblides, A. Efficient Methods for Evaluation on Ploidy Level of Cucurbita Pepo L. Regenerant Plants Obtained in Unpollinated Ovule Culture In Vitro. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilissen, L.J.W.; Van Staveren, M.J.; Creemers-Molenaar, J.; Verhoeven, H.A. Development of Polysomaty in Seedlings and Plants of Cucumis Sativus L. Plant Sci. 1993, 91, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervin, C.D. A Study of Polysomaty in Cucumis Melo. Am. J. Bot. 1941, 28, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.