Abstract

Vicia faba is an agriculturally and nutritionally important legume whose growth and productivity are strongly influenced by biotic stress factors. Understanding the mechanisms by which plants respond to stress is therefore essential for improving agricultural productivity and enabling the selection of stress-tolerant cultivars. This study evaluated whether biochemical and physiological parameters can serve as early indicators of stress induced by Aphis fabae infestation in young V. faba plants. Plants were exposed to two levels of aphid infestation (low- and high-stress) and compared with aphid-free controls. Low stress caused minimal alterations in antioxidant responses: catalase (CAT) activity increased by 9.9%, glutathione (GSH) content by 20%, and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels decreased by 17.6% relative to controls. Under high stress, oxidative damage and antioxidant activation were pronounced, with CAT activity rising 2.4-fold, GSH content increasing 2.6-fold, and MDA accumulating 2.6-fold compared to control plants. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activities increased under both stress levels, though without large differences, while nitrate reductase (NR) activity showed non-significant variation. Proline accumulation remained largely unchanged, showing only a slight 13–15% increase relative to controls. Photosynthetic pigment analysis revealed that low stress reduced contents of chlorophyll a and total chlorophyll, while increasing contents of chlorophyll b and carotenoids. Stress markedly altered pigment balance, yielding a 25.4% higher chlorophyll a/b ratio compared with control plants. The results indicate that V. faba plants can tolerate low-intensity aphid stress with minimal biochemical disturbance, whereas high infestation elicits strong oxidative stress and significant physiological changes. The measured biochemical markers, particularly CAT, MDA, and GSH, proved sensitive to early stress onset, offering valuable tools for early detection of biotic stress before visible symptoms appear. The research contributes to a better understanding of plant responses to stress, enables early detection of stress factors affecting plant physiology, facilitates the assessment of their adaptive potential, and may aid in the development of strategies to improve faba bean resistance to pest infestations. This research enhances understanding of V. faba stress responses, enabling early detection of stress factors and assessment of the plant’s adaptive potential. The insights gained may support the development of strategies to improve faba bean resistance to pest infestations and contribute to more sustainable agricultural productivity.

1. Introduction

Faba bean (Vicia faba L.) belongs to the most nutritionally and agronomically important legume crops in the world, after soybean (Glycine max L.) and pea (Pisum sativum L.). It is characterized by high protein content and an exceptional capacity for atmospheric nitrogen fixation, contributing 120–160 kg N ha−1 and enhancing soil fertility when included in cereal-based rotations [1,2,3,4]. It plays a significant role in human nutrition, animal feed, and sustainable agricultural systems [5], while its popularity has increased in response to the global shift toward plant-based diets [2]. The species contains diverse bioactive constituents—including levodopa, natriuretic compounds, antioxidant peptides, anticarcinogenic lectins, and dietary fiber—associated with human health benefits [1,6]. However, individuals with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency may experience favism upon consumption [6].

Vicia faba is cultivated in more than 66 countries, spanning major agroecological regions from the Mediterranean to East Asia, Oceania, and the Americas [7,8]. It grows on a wide range of soil types and tolerates pH values from 4.5 to 9.0 [1]. Despite its agronomic value, its production is constrained by susceptibility to diseases, environmental stressors, and insect pests, resulting in unstable yields. Among these, the black bean aphid Aphis fabae Scopoli is one of the most damaging pests globally, reducing yield by up to 37% in conditions without pest control and posing a strong threat to the grain industry [9,10]. Aphid feeding inflicts direct damage through phloem extraction and indirect damage via virus transmission and honeydew deposition, which supports sooty mold growth and suppresses photosynthesis [11]. A. fabae is widespread across Europe, Western Asia, Africa, and South America [10], infesting approximately 1500 plant species and using V. faba as a secondary host [12,13]. Its development, reproduction, and impact are shaped by multiple biotic and abiotic factors [14,15,16].

Plant responses to insect herbivory frequently involve changes in photosynthesis, respiration, stomatal conductance, and transpiration [17,18], while research on plant–aphid interactions has focused mainly on stress responses, pest-tolerant genotypes, and eco-friendly control strategies [19].

Studies on Vicia faba responses to Aphis fabae have mostly focused on morphology and pigments. Nikolova (2023) evaluated 12 cultivars, finding reduced chlorophyll, height, and protein in susceptible plants, while Goławska et al. (2010) reported declines in chlorophyll a and b [19,20]. Early detection via hyperspectral imaging is possible [21]. However, integrated studies combining biochemical markers (CAT, GSH, MDA) with physiological responses are lacking, leaving the overall redox-mediated stress response under aphid pressure insufficiently explored.

Given the substantial physiological stress caused by A. fabae, a comprehensive investigation of biochemical and redox responses is needed to better elucidate tolerance mechanisms and support breeding strategies aimed at improving V. faba resilience. This is the first report on the biochemical stress responses of the “Stereo” cultivar.

The present research aimed to determine whether biochemical parameters can serve as early indicators of biotic stress in V. faba prior to the onset of visible damage. Quantified biochemical markers included several stress-related enzymatic parameters—catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and nitrate reductase (NR)—along with non-enzymatic indicators such as malondialdehyde (MDA), reduced glutathione (GSH), and proline (Pro). Additionally, alterations in chlorophyll pigment content were evaluated to assess the physiological status of infested versus non-infested plants. Chlorophyll content is a widely accepted indicator of photosynthetic capacity, plant health, productivity, and overall physiological status [20,22], and is known to fluctuate under stress conditions or during natural leaf senescence [23]. Herbivory alters photosynthetic traits in various ways depending on the herbivore’s feeding strategy [24,25], while chlorophyll loss in infested plants varies with aphid species, infestation duration, and host plant genotype [26]. Understanding the mechanisms that enable plants to grow and develop under stressful conditions is crucial for improving agriculture and selecting cultivars with preserved or higher yields.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

The commercially and locally used Stereo broad beans variety of V. faba seeds was obtained from Oroseeds, Aleksinac, Republic of Serbia. Seeds were classified by size. The largest, equally sized group was used in the experiment. Seeds were pre-soaked in distilled water for six days at 28 °C in darkness to stimulate germination. Uniform, healthy seedlings with fully developed organs were selected and subsequently transplanted into pots (d 8 cm × H 25 cm) containing soil. The experiment took place in a greenhouse under a controlled temperature regime of 25 ± 3 °C, with a 16/8 h day/night photoperiod. Commercially available ‘Agromarket’ soil, characterized by suitable physico-chemical properties, was used as the substrate for pot cultivation. It had a pH of 6.60, dry matter of 48%, humidity of 52%, nitrogen of 100–200 mg L−1, phosphorus (P2O5) of 100–250 mg L−1, and potassium (K2O) of 100–300 mg L−1. Its physical properties included granulation less than 500 mm, water capacity of 320%, and specific mass of 480 g L−1. Plants were watered every other day by adding 150 mL of distilled water to prevent the soil from drying out. When the plants reached approximately 20 cm in height, 30 pots were transferred to the field to allow for natural infestation by A. fabae. Within several days, black aphids were observed colonizing the apical regions, stems, and leaves of the plants. Identification of A. fabae and maintenance of the aphid population occurred in the laboratory of zoology at the Department of Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Sciences and Mathematics, University of Niš. The infested plants served as the starting pool for further infestation to create stressful conditions. Both plants and A. fabae were maintained in mesh-covered cages (45 × 85 cm) to prevent insect escape. Three cages were used. The first cage was a plant control group with no pests. The other two housed infested plants to establish varying stress intensities in V. faba. All plants used for biochemical assays were at the same developmental stage, BBCH 35 (five visibly extended internodes). The cages with potted plants were kept in a growth chamber under the described environmental conditions. For each treatment, values were obtained from three independent replicates. The leaves were collected from three plants per group (control, low- and high-stressed).

2.2. Determination of A. fabae Infestation—Visual Screening of Biotic Stress

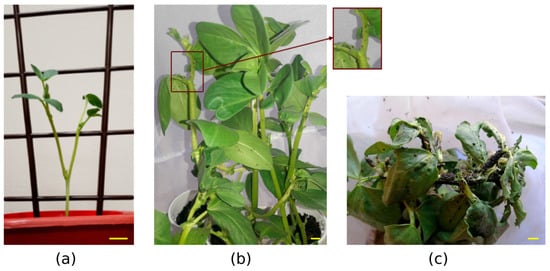

The infestation level of faba bean with black aphids was measured as in similar research studies [5,27,28], according to the visual method of Banks (1954) [29]. The infestation indices were estimated using the percentage of plant surface covered with aphids. For screening of biotic stress, we used a scale of 0–4 for the infestation index (I index). The indexes were as follows: 0, without infestation (no aphids visible on the plant); 1, low infestation (several aphids present on the stem, though still not confined to the uppermost leaves, and less than 20% of the plant colonized); 2, average infestation (aphids present in large numbers and diffusely infesting a large proportion of leaves and stems, and almost half of the plant colonized); and 3, high infestation (aphids present in large numbers, very dense, infesting leaves, with stems usually blackened by aphids, and almost the entire plant colonized) (Figure 1). Three groups of plants that differed in terms of the presence of stress were used in the experiment. The groups were designated as control (aphid-free plants), low-stressed plants (LS; low-infested plants), and high-stressed plants (HS; high-infested plants) according to the scale described.

Figure 1.

Plant material of Vicia faba during the experimental setup. (a) Plant prepared for transfer to the field. (b) Vicia faba plants under low-stress conditions. The red arrow indicates the enlarged part of the plant stem under low-stress conditions. (c) Vicia faba plants under high-stress conditions. Yellow lines represent scale bars = 2 cm.

2.3. Plant Sampling

For extract preparation, leaves were collected from each group of plants. We selected equally positioned upper leaves that were approximately the same size and had equal exposure to light. Using a soft brush, we removed aphids from the leaves of stressed plants. The leaves were used immediately after sampling to prepare extracts for biochemical analyses.

2.4. Chemicals and Instruments

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Co., St. Louis, MO, USA. Spectrophotometric assays were performed on a double-beam UV–VIS spectrophotometer Perkin Elmer lambda 15 Waltham Massachusetts (Waltham, MA, USA).

2.5. Biochemical Status in Vicia faba

2.5.1. Determination of Catalase Activity

Catalase activity was determined by the spectrophotometric method according to Aebi (1974) [30]. Extracts were obtained by homogenizing the fresh plant material in a cold awn with the addition of 0.05 M KH2PO4 buffer (pH 7). After homogenization, the homogenates were quantitatively transferred to a centrifuge tube. The obtained extracts were centrifuged, and the supernatants were used as samples for further analyses. The reaction mixture contained 50 mmol dm-3 K-phosphate buffer (pH 7) and 30% H2O2. The working sample was obtained by mixing a 1.9 mL 50 mM K-phosphate buffer (pH 7), a 100 μL sample of extract, and 1 mL 30% H2O2 solution. As a blank sample, K-phosphate buffer solution (pH 7) was used instead of the extract. Catalase activity was measured based on the decrease in H2O2 absorbance in the presence of the enzyme extract at λ = 240 nm. CAT activity was expressed as units per milligram of protein (U mg−1). The unit of catalase activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that causes the degradation of 1 μmol H2O2 per minute at 25 °C. The soluble protein content was determined by the Bradford method (1976) [31].

2.5.2. Determination of Superoxide Dismutase Activity

According to Giannopolitis and Ries (1977), the reaction mixture contained 2.6 mL 0.05 M K-phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 100 μL 13 mM L-methionine, 100 μL 75 μmol nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT), 100 μL 0.1 mM EDTA-2 Na, and 50 μL 2 μM riboflavin [32]. The working sample was obtained by adding 50 μL of the enzyme extract prepared in 0.05 M KH2PO4 (pH 7.8) to the test tube with the reaction mixture. A blank sample was obtained by adding K-phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) to the reaction mixture instead of the extract. The absorbance at λ = 560 nm was recorded on the spectrophotometer. SOD activity is expressed as units per milligram of protein (U mg−1). A unit of SOD activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that inhibits the reduction of NBT by 50% at 25 °C and λ = 560 nm.

2.5.3. Determination of Nitrate Reductase Activity

The enzyme activity was recorded according to the Hageman and Reed (1980) method [33]. To determine the activity of the nitrate reductase enzyme, the extraction was obtained by homogenizing 0.2 g of fresh plant material with the addition of 5 mL 0.25 M KH2PO4 (pH 7.4). The reaction mixture contained 0.8 mL K-phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 2 mL distilled water, 0.6 mL indicator 0.1% N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine chloride (NEDD), and 0.6 mL 1% sulfanilamide. The working sample was a mixture of a reaction medium and 0.8 mL sample extract after incubation in a water bath at 36 °C. The absorbance was recorded on a spectrophotometer at a wavelength of λ = 540 nm. The blank sample contained a K-phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) instead of the extract. Nitrate reductase enzyme activity is expressed in μM NO2− g−1 h−1. The concentration of NO2− in the sample was determined from the standard curve.

2.5.4. Determination of Lipid Peroxidation Intensity Level

Following the protocol described by Heath and Packer (1968), malondialdehyde (MDA) contents were evaluated [34]. The working sample was obtained by mixing the 500 μL extract of fresh plant material (prepared with 0.1 M KH2PO4 buffer (pH 7)), 1500 μL 8.9% trichloroacetic acid (TCA), and 2 m 0.6% thiobarbituric acid (TBA). For the blank test, 0.1 M K-phosphate buffer (pH 7) was used instead of the sample. The amount of MDA in the samples was determined according to the standard curve of MDA standard (1,1,3,3 tetraetoxypropane) at a concentration range of (0–50 µM) and expressed as nM MDA mg−1 protein.

2.5.5. Determination of the Amount of Reduced Glutathione

The amount of reduced glutathione was determined based on the color reaction of non-protein thiol (-SH) groups in the presence of DTNB (5.5-dithiobis [2-nitrobenzoic acid]), and the absorbance of the colored product is measurable at λ = 412 nm [35]. The GSH content was estimated by the spectrophotometric method of Sedlak and Lindsay (1968) [36]. The reaction mixture contained 2 mL 0.4 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.9) and 0.1 mL 6 mM DTNB. The working sample was obtained by mixing the reaction mixture with 0.1 mL of the sample extract, which was obtained by homogenizing 1 g of fresh leaves in 10 mL 0.1 M KH2PO4 buffer (pH 7). For the blank test, a K-phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was used instead of the extract. The amount of GSH was determined according to the standard curve of GSH (0–100 µM), and the result was expressed as nM GSH mg−1 protein.

2.5.6. Determination of Proline Content

Proline content was detected according to the method of Bates et al. (1973) [37]. To determine the proline content, 3% sulfosalicylic acid (SSA) was used for extract preparation. The reaction mixture contained 10 mL 3% cold sulfosalicylic acid (SSA), 2 mL acetic acid, 2 mL fresh ninhydrin reagent, and 4 mL toluene. The ninhydrin reagent was prepared by dissolving 1.25 g of ninhydrin in a solution containing 30 mL of acetic acid and 20 mL of 6 M orthophosphoric acid. The working sample was obtained by mixing the reaction medium with the sample extract. A blank was obtained by adding 3% SSA to the reaction medium instead of the extract. Absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of λ = 520 nm. Proline content was determined based on a standard curve of proline (0–100 µM), and the results were expressed in micromoles of proline per gram of fresh weight (µmol g−1 FW).

2.6. Physiological Status in Vicia faba Plants

Leaf Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Levels

The content of chlorophyll a (Chl a), chlorophyll b (Chl b), and carotenoids (Car) was measured spectrophotometrically, in 100% methanol, and expressed as mg g−1 fresh weight. Plant extracts were prepared in the dark and at low temperature by macerating 0.05 g of fresh leaves in 5 mL of methanol. After centrifugation for 10 min at 4 °C and 300 rpm, the supernatants were used for spectrophotometric analysis. The absorbance of the extract was measured at 665, 652, and 470 nm using a spectrophotometer, and the pigment concentrations were calculated according to Lichtenthaler (1987) [38]. The equations used to determine the pigment concentrations were:

chlorophyll a ca (μg/mL) = 16.72 A665.2 − 9.16 A652.4

chlorophyll b cb (μg/mL) = 34.09 A652.42 − 15.28 A665.2

carotenoids c(x+c) (μg/mL) = (1000 A470 − 1.63 ca − 104.96 cb)/221

Conversion of pigment concentrations expressed in μg/mL to pigment content in mg/g fresh leaf mass was performed using the formula:

where C is the pigment content in the leaf (mg/g fresh mass), c is the pigment concentration in the extract (μg/mL), V is the total extract volume (mL), R is the dilution factor (if the extract was diluted), m is the fresh mass of the leaf sample (g), and 1000 is the unit-conversion factor from μg to mg.

C = c · V · R/(m · 1000)

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All measurements were performed in triplicate. We used a few statistical analyses. One-way ANOVA was performed using STATISTICA software for Windows ver. 8 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

The normality of the data distribution was assessed, and comparisons between the control and experimental groups were made using the Student’s t-test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS software, version 19.0.

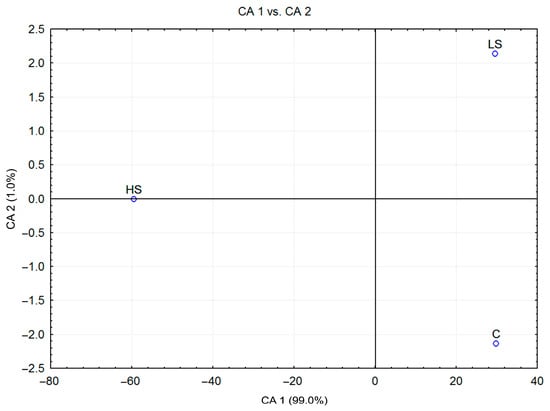

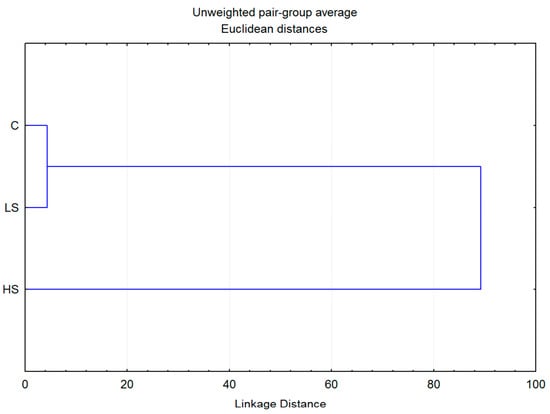

The statistical analysis—descriptive statistics, canonical discriminant analysis (CDA), and cluster analysis (CA) of the biochemical stress parameters (SOD, CAT, ANR, MDA, GSH, and proline) data set—was performed using the STATISTICA software for Windows ver. 8 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). CDA was performed to test the hypothesis that the analyzed sample was composed of three discrete groups of individuals that were chemically differentiated from each other. The stress parameters from three a priori groups of individuals, including low- and high-stress groups and a control group (C), were processed using CDA. The centroids, as the mean discriminant scores for each a priori group on the canonical discriminant functions, were used to display their relationships on a scatterplot. The similarity of the biochemical profile was analyzed by CA, employing linkage distance as a method of determining the distance between clusters in hierarchical clustering. All multivariate analyses were performed on log-transformed data.

3. Results

In plants under stress, various biochemical defense mechanisms are activated, and enzymatic and non-enzymatic components are recruited. To understand the underlying defense mechanisms of pest-induced injury impacts, we analyzed changes in the enzymatic activity of CAT, SOD, and NR and the content of MDA, GSH, proline, and Chl a, Chl b, and Car in V. faba plants during infestation with A. fabae.

3.1. Biochemical Parameters in V. faba Plants Under Biotic Stress

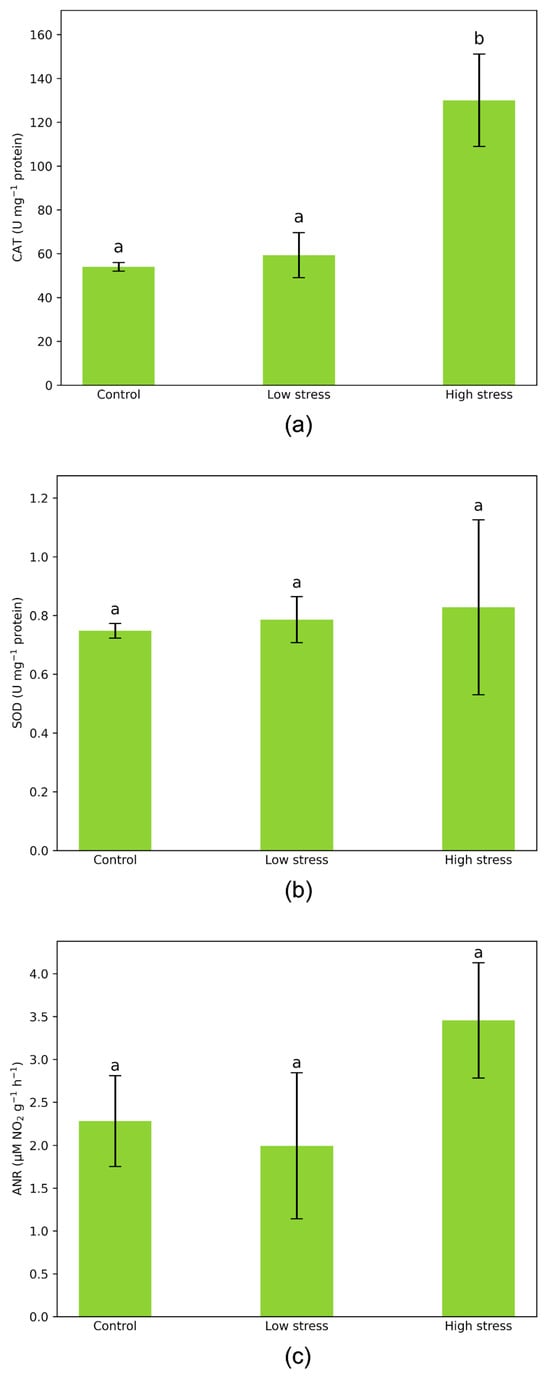

Comparing the activity of all tested enzymes for plants during low-stress (infestation index 1) and in the absence of stress, only slight differences were observed. We noticed that plants in high-stress conditions (infestation index 3) exhibited remarkably high activity for the enzyme catalase. It was 2.4 times higher compared to aphid-free plants. Low stress did not alter enzyme activity significantly, and it was 9.9% higher than in control plant samples (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Enzymatic activities of (a) CAT (U mg−1 protein), (b) SOD (U mg−1 protein), and (c) ANR (μM NO2− g−1 h−1) in leaves of Vicia faba plants under control and aphid-infested conditions. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three biological replicates. n = 3. Vertical bars represent SD. Letters denote statistically significant differences between infested plants and controls as determined by the Student’s t-test (p < 0.05).

In both groups of stressed plants, recorded SOD activities were higher than in aphid-free plants, though the differences were not pronounced. SOD activity increased by 10.7% under high stress and by about half that under mild stress, compared to non-stressed plants (Figure 2).

Activity of nitrate reductase (NR) varied with stress intensity, although these differences were not statistically significant. In low-stress conditions, NR activity decreased by 12.6% compared to optimally growing (control) plants. In contrast, plants under severe infestation exhibited a 51.4% increase in NR activity relative to the control group (Figure 2).

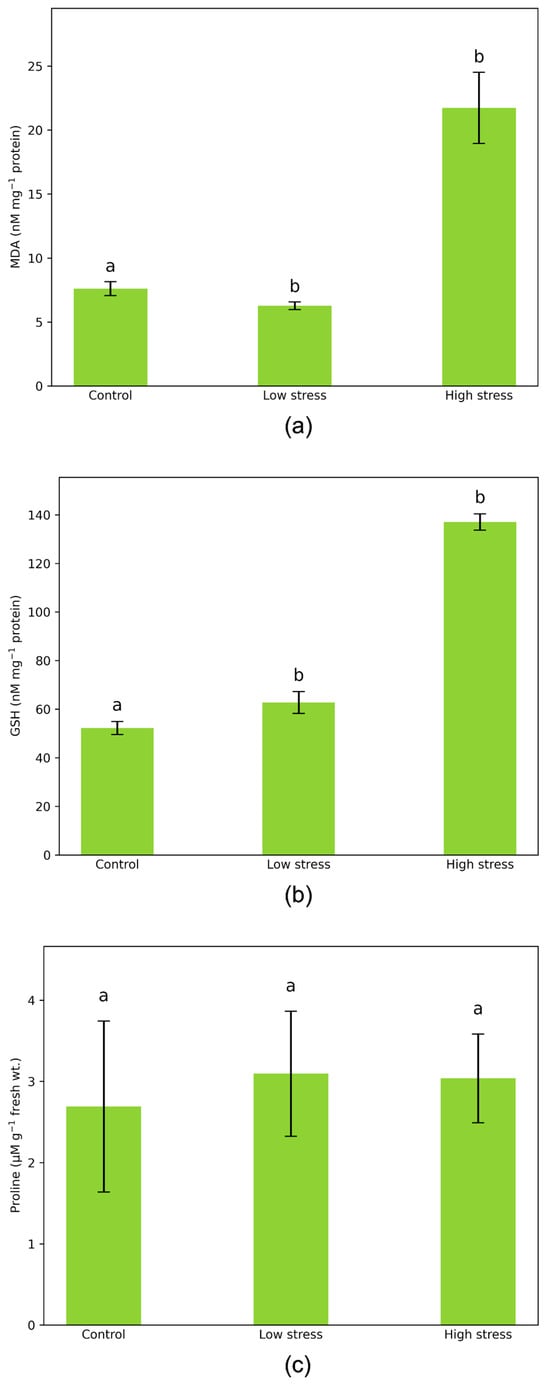

GSH content values range from 52.2 to 137.1 nM mg−1 proteins (Figure 3). In the low-stressed plants, GSH content was 20% higher than in the control plants. In the high-stressed plants, GSH content increased markedly and was 2.6 times higher compared to the control plants.

Figure 3.

(a) MDA (nM MDA mg−1 protein), (b) GSH (nM GSH mg−1 protein), and (c) proline (µmol g−1 FW) content in leaves of Vicia faba plants under control and aphid-infested conditions. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three biological replicates. n = 3. Vertical bars represent SD. Letters denote statistically significant differences between infested plants and controls as determined by the Student’s t-test (p < 0.05).

The content of malondialdehyde (MDA), which is one of the final products of membrane lipid degradation in cells, is used as a measure of the intensity of lipid peroxidation (LP). In low-stressed plants, MDA content was 17.6% lower than in non-stressed plants. Plants exposed to high stress were particularly vulnerable to the direct actions of aphids, and MDA content in their leaves was extremely high, 2.6 times that in the leaves of non-stressed plants (Figure 3).

The proline content in plants subjected to varying levels of A. fabae infestation was comparable to that in control plants (Figure 3). Its accumulation was only marginally affected by infestation, showing a slight increase of 13–15% compared to non-stressed plants.

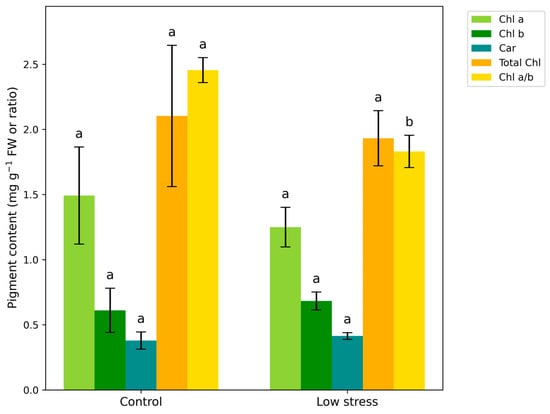

3.2. Physiological Responses of V. faba Plants Under Biotic Stress

The leaves of plants grown in low-stress conditions had lower levels of chlorophyll (16.2%) and total chlorophyll (8.13%) compared to control plants, but higher levels of chlorophyll b (11/8%) and carotenoids (9.23%). Leaves of infested plants expressed a significantly higher chlorophyll a/b ratio of 25.4% than leaves in control conditions (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Chl a, Chl b, and Car content, and Chl a/b ratio in leaves of Vicia faba plants under control and aphid-infested conditions. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three biological replicates. n = 3. Vertical bars represent SD. Letters denote statistically significant differences between infested plants and control as determined by the Student’s t-test (p < 0.05).

3.3. Multivariate Analyses (CDA and CA) of V. Faba Biochemical Stress Parameters

Different biochemical parameters that include enzymatic antioxidants (CAT, SOD), enzyme NR, non-enzymatic antioxidants (GSH, Pro) and stress marker MDA of V. faba plants infested with A. fabae and non-infested plants, were compared by canonical discriminant analysis (CDA) as well as cluster analysis (CA).

The CDA of V. faba plants from different stress conditions, considered as three a priori groups, showed that the first two canonical axes participated in 100.0% of the total discrimination, of which the first axis (CA 1) accounted for 99.0% (Table 1). Furthermore, the scatter diagram in the projection of the first two axes (Figure 5) revealed a clear separation of the centroids of the group of plants grown under high-stress conditions (SH), located in the negative zone of CA 1, compared to plants grown under low-stress conditions (SL) and without stress (C). The coefficient values for SOD, NR, GSH, Pro, and CAT primarily loaded the first canonical axis, which carries the majority of the total variability, thus providing an absolute contribution to discrimination (Table 1). On the other hand, SOD had an impact on both canonical axes. Further segregation of plants cultivated in the absence of aphids (C) and in low-stress conditions (SL) was possible along the CA 2. p. The second discriminant axis, which was defined by the content of SOD (Table 1), generally separated the control group (CO) from a group of low-stressed plants (Figure 5) with less significance. The measured mean values of SOD, GSH, MDA, NR, and CAT were higher in the group of high-stressed plants compared to the other individuals, confirming the obtained segregation pattern. This indicated the dissimilarity of biochemical compounds between the high-stressed plants and those exposed to low stress or without infestation.

Table 1.

Standardized coefficients for the first two canonical axes (CA) of variation in 6 Vicia faba biochemical parameters from the discriminant functional analysis of 3 a priori groups. Significant coefficients are in boldface.

Figure 5.

Canonical discriminant analysis (CDA) based on contents of 6 Vicia faba biochemical parameters isolated from plants of 3 a priori groups.

Additionally, cluster analysis showed that the control plants and plants grown in low-stress conditions were the most similar in terms of contents of analyzed biochemical parameters, while high-infested plants exhibited a considerable degree of individuality (Figure 6). A significant difference was observed for the high-stressed group, which showed a very low level of similarity to both other groups. However, these results are sufficient to assume the existence of two clear entities: individuals grown in low- or stress-free conditions and those belonging to an A. fabae high-stress group.

Figure 6.

Dendrogram obtained by cluster analysis of 3 groups of Vicia faba plants based on 6 biochemical parameters.

3.4. One-Way ANOVA of V. faba Biochemical Stress Parameters

ANOVA results for enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant parameters are presented in Table 2. Malondialdehyde and reduced glutathione were highly significant (p = 0.000), with GSH showing the highest discriminative power [F(2,8) = 277.86]. Along with catalase, these parameters were the most informative for differentiating the biochemical responses of V. faba under varying stress conditions. In contrast, superoxide dismutase, proline, and nitrate reductase had the lowest F values, indicating a smaller contribution to distinguishing stress responses among the experimental groups.

Table 2.

Results of ANOVA of 6 Vicia faba analyzed biochemical parameters. Significant coefficients are in boldface.

4. Discussion

Different studies have shown that the main physiological mechanisms of plant tolerance to biotic stress caused by pest infestation are increased photosynthetic activity and enhanced detoxification mechanisms that eliminate the negative effects of plant aphid feeding [39,40]. This study enables novel insights into the biochemical and physiological responses of young V. faba plants to A. fabae infestation. It is the first investigation to characterize the stress response of the cultivar Stereo during the vegetative growth stage under aphid pressure. To gain better insight into plant responses, we exhibit plants at two intensity levels of stress conditions, low and high. When plants are under stress conditions, they must alter their biochemical and physiological activity so they can adapt to harmful stress effects. Changes in biochemical processes precede or follow changes in physiological parameters and can be observed early, long before morphological changes become visible. As a result, the present study included a comparative analysis of biochemical stress parameters in stressed and optimally growing plants.

This research was conducted in a laboratory, as field experiments depend on many uncontrolled biotic and abiotic factors (e.g., predators, pollinators, parasitoids, and climate factors such as rain, temperature, wind, and humidity) that act together on plants and aphids, influencing their interaction [41]. Larger seeds were selected due to their higher germination rates and their potential to produce taller plants with more branches and higher yields. Seeds of local cultivars were selected to evaluate plants’ responses to biotic stress, as they are more resistant to various local environmental conditions, such as pathogens and abiotic stress factors [2]. Aphid-induced damage is closely linked to a plant’s developmental stage, with early colonization during ontogenesis causing greater harm and negatively affecting yield potential [42]. Field observations show that aphids predominantly infest plants during early vegetative growth, when interspecies interactions are minimal. Therefore, young plants at growth stage BBCH 35 were selected as the focus of this study.

Different studies examined the relationship between plant morphological characteristics, primarily plant height and the preference of aphids, and conclusions were very diverse, even contradictory [19]. Accordingly, measurements of morphological parameters were omitted. Given that leaf age significantly influences plant–aphid interactions, as reported by Pincebourde and Ngao (2021), leaves of comparable developmental stages were used in this study [17].

Exposure to biotic stresses poses significant threats to plant growth and productivity. One of the key molecular responses to such stress is the enhanced generation of reactive oxygen species, which leads to oxidative stress [43]. Vicia faba plants exposed to Aphis craccivora infestation activate an enzymatic antioxidant defense system, with peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase playing key roles in scavenging reactive oxygen species and protecting against oxidative damage. However, data on the involvement of other antioxidants in the plant’s defense and adaptive responses during V. faba plant–A. fabae interaction remain limited. Creating reliable biochemical markers for evaluating insect resistance remains a major challenge [44].

Under stress conditions characterized by increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), the activity of the enzyme catalase is elevated, reflecting its role in catalyzing the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [45]. Faba bean plants exposed to high stress exhibited markedly elevated catalase activity. A comparable pattern of catalase and superoxide dismutase activity was observed in tobacco leaves subjected to biotic stress. Catalase played a central role in the tobacco defense response against aphid infestation in the presence of Bemisia tabaci, whereas SOD exhibited limited involvement in the antioxidant defense mechanism [46]. In response to stress conditions, plants may increase the activity of antioxidant enzymes depending on the plant species, plant metabolism, plant development, and the duration and intensity of the stress [47]. In contrast to V. faba, chickpea plants infested with Helicoverpa armigera exhibited an opposite antioxidant response, showing a decrease in CAT activity and an increase in SOD activity [48]. Although changes in SOD activity were recorded during barley infestation with Pyrenophora teres f. teres, Kunos et al. (2022) did not establish a clear correlation between SOD activity and seedling resistance [49]. Superoxide dismutases (SODs) are present in chloroplasts, mitochondria, cytosol, and the apoplast, converting superoxide radicals into hydrogen peroxide to initiate downstream antioxidant defenses. During biotic stress, SOD responses in legumes and crops are generally modest. In Medicago truncatula exposed to aphids, cytosolic SOD increased slightly, while CAT and GSH were more strongly activated [50]. Potato infected with Phytophthora infestans showed significant chloroplastic and cytosolic SOD increases [51], whereas wheat infested with Sitobion avenae exhibited minor SOD changes relative to CAT and GSH [52]. These observations are consistent with our results in Vicia faba, where SOD activity did not differ significantly among stress levels. This suggests that aphid infestation induces only limited superoxide accumulation, while downstream antioxidant mechanisms, such as CAT and GSH, play the dominant role in mitigating oxidative stress. The pattern reflects the early and compartment-specific action of SOD in the plant’s defense response.

Glutathione is distributed throughout various compartments of plant cells and participates in a wide range of physiological processes during plant growth and development. Its most prominent role lies in antioxidant defense, where it contributes to cellular protection under stress conditions (Ogawa, 2005) [53]. The present study demonstrated that infestation by black aphids in V. faba plants led to alterations in GSH content in leaves under both mild and severe stress conditions [53]. A pronounced increase in GSH levels was observed in plants subjected to heavy aphid infestation, consistent with the established role of GSH as a scavenger of reactive oxygen species [35]. Activation of the GSH defense system is important for maintaining a reduced cellular redox state [54]. Given the substantial difference in stress intensity between the two groups of infested cultivated plants, it can be assumed that the content of GSH increases gradually with the intensification of infestation.

Miller et al. (2010) identified MDA as a key biomarker for assessing the extent of membrane lipid peroxidation [55]. Under stress conditions, the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) induces oxidative damage, which is positively correlated with MDA levels in plants [56]. Biotic stress caused by aphid colonization resulted in significantly different and even opposite changes in MDA content between the two groups of stressed plants compared to non-infested plants. Considering that stress-tolerant plants typically exhibit lower or only slightly elevated MDA content, it is plausible that V. faba plants possess a degree of tolerance to mild aphid infestation. The increase in lipid peroxidation indicates that high infestation provoked oxidative stress in faba bean plants. Elevated malondialdehyde levels in stressed plants indicate a decline in membrane fluidity, damage to membrane components, disruption of ion channels, and increased plasma membrane permeability [57]. Plants under severe stress respond to increased MDA content by increasing the activity of catalase, which plays a role in the detoxification of ROS, and maintaining the balance between their production and scavenging [58].

Aphid infestation can increase leaf gas exchange and nitrogen content while reducing growth rate, potentially inducing mild water deficit due to elevated transpiration and stomatal conductance [17,59]. In wheat plants, NR activity was shown to decline with decreasing soil moisture content [60]. Nitrate reductase (NR), a key cytosolic enzyme in nitrate assimilation and NO signaling, typically shows only minor changes under moderate biotic stress. In Medicago truncatula and Arabidopsis, NR activity was largely stable during aphid or pathogen challenge [50,61]. Consistently, in V. faba, NR activity did not differ significantly across stress levels, suggesting early-stage aphid feeding does not strongly disrupt nitrogen metabolism or NO-mediated defense, while slight increases under severe stress may reflect adaptive maintenance of nitrate transport from roots to shoots.

Proline is widely recognized as a multifunctional osmoprotectant that accumulates in both the vacuole and cytoplasm under stress, where it contributes to osmotic adjustment, protein stabilization, and the detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through the formation of stable complexes that limit lipid peroxidation [62,63,64,65,66]. Its accumulation is often higher in stress-tolerant genotypes, as demonstrated in wheat, where increased proline levels were associated with reduced lipid peroxidation under stress [67]. Proline concentrations are generally elevated in stress-tolerant plants compared to those that are stress-sensitive [54]. However, proline responses vary considerably among species and cultivars [62,63]. In the present study, Vicia faba exhibited only minimal proline accumulation under aphid infestation, in sharp contrast to the pronounced proline elevation commonly observed in legumes exposed to abiotic stressors such as drought or salinity [68,69]. Unlike osmotic stress, which induces strong proline biosynthesis to maintain turgor and limit ROS, aphid feeding primarily causes localized wounding and oxidative stress without triggering substantial osmotic imbalance. Consistent with this, V. faba under high aphid pressure showed markedly elevated MDA levels and strong activation of CAT and GSH, indicating that antioxidant defenses rather than proline-mediated osmoprotection dominate the plant’s response. These findings suggest that, during biotic attacks, proline plays a limited role in mitigating oxidative damage in V. faba, whereas enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants serve as the primary components of redox regulation and stress tolerance.

Vicia faba plants heavily colonized by aphids exhibit sensitivity to biotic stress. Antioxidant components, including catalase and glutathione, were activated to counteract the detrimental effects of reactive oxygen species, indicating their protective role against oxidative damage in highly infested plants.

Aphids grow and develop rapidly, and in a short time, numerous colonies on V. faba plants cause damage by altering the rate of photosynthesis, plant growth, and physiological processes [70]. Under intense aphid infestation, leaves exhibit pronounced morphological and pigment-related changes, including wrinkling, curling, discoloration, chlorosis, deformation, drying, and necrosis [10,24]. These symptoms, clearly visible on leaves under high-stress conditions, indicate substantial chlorophyll loss. Since chlorophyll content is a reliable indicator of plant vigor [20], the physiological status and agronomic potential of the high-stressed plants were evidently compromised. Based on the appearance of low-stressed plants, without visible stress symptoms or damage, it is not possible to determine whether their potential for achieving favorable agronomic traits has been compromised.

There were no significant differences in the content of photosynthetic pigments between control and infested plants except for the chlorophyll a/b ratio, where a reduced value indicates alterations in the composition of the photosynthetic antenna complexes [23]. Lack of statistical significance in photosynthetic pigment content between control and infested plants indicates that plants are tolerant to aphid colonization in low-stress conditions. The obtained results are consistent with observations in wheat [71] and soybean [72] under biotic stress conditions caused by aphid infestation. Different studies suggest that the ability of plants to maintain photosynthetic activity under herbivore attack may represent an adaptive, compensatory strategy [20,25]. This physiological resilience not only supports continued growth but may also reflect a strategic reallocation of resources toward defense, distinguishing tolerant genotypes from susceptible ones [25]. The decrease in chlorophyll a and total chlorophyll levels (although not statistically significant) could be associated with an enhanced allocation of resources to the production of plant defense-related metabolites [20]. Given that increased total photosynthetic pigment content in V. faba leaves has been shown to significantly enhance agronomic productivity—including yield and its components, such as the number of pods per plant and seed yield [73]—it can be inferred that a reduction in total chlorophyll levels may negatively affect key agronomic traits. Since plant productivity is driven by photosynthesis, alterations in the levels of photosynthetic pigments can serve as sensitive indicators of physiological disturbances caused by different stress conditions [74].

In Vicia faba, biochemical and physiological responses to aphid infestation reflect a coordinated stress-response model. High infestation triggers strong antioxidant activation (CAT, GSH) and increased MDA, indicating substantial oxidative stress, which aligns with reductions in chlorophyll a, total chlorophyll, and altered chlorophyll a/b ratios, suggesting photosynthetic impairment. Elevated carotenoids under low stress likely support ROS buffering and photosynthetic maintenance. Together, these markers provide an integrated profile of stress progression, linking early redox imbalance to effects on pigments and photosynthetic efficiency, offering a basis for early detection and characterization of biotic stress.

Based on the statistical differences in biochemical responses, it is obvious that the high level of infestation with A. fabae significantly affected the content of biochemical compounds in V. faba. Differences in the contents of GSH and similarity in the contents of other antioxidant parameters among plants grown during low stress and control plants, indicate their potential to tolerate a low intensity of biotic stress. On the other hand, the significantly high concentrations of CAT and GSH recorded in plants grown during high stress, as well as a high value of the stress marker MDA, indicate the plant’s sensitivity to A. fabae infestation.

5. Conclusions

Vicia faba plants play an important role in nutrition and health improvement, and they are environmentally friendly nitrogen fixators. Because of this, their cultivation should not be neglected. A comprehensive understanding of V. faba responses to various stress conditions is essential for advancing breeding strategies and enhancing yield potential. We compared biochemical stress parameters between aphid-infested plants exposed to different infestation intensities and unstressed control plants. We observed that MDA and GSH contents differed significantly between stressed and non-stressed plants, while CAT activity was particularly elevated in plants subjected to severe aphid infestation. SOD and NR enzymatic activities were not markedly altered. Our findings suggest that the antioxidant compounds CAT, GSH, and MDA can serve as a practical means for early detection of oxidative stress in Vicia faba under aphid infestation and contribute to a better understanding of when stress becomes a high threat for plants, before obvious visual symptoms are observed. These parameters can be used to screen cultivars for stress tolerance, as genotypes with higher antioxidant activity and lower MDA under stress are likely to be more resilient. Monitoring chlorophyll levels can serve to assess plant stress tolerance and as a tool for predicting faba bean yield, especially under challenging stress conditions. In field applications, small leaf samples can be rapidly analyzed using portable or high-throughput methods, supporting timely management decisions and guiding marker-assisted breeding programs in the development of stress-resilient faba bean cultivars. Although this study was conducted under control conditions with a limited scope, future research should validate these findings across multiple cultivars under field conditions and investigate rapid, high-throughput detection methods to support practical applications in stress monitoring and breeding programs, thereby improving the resilience of Vicia faba and other leguminous crops and optimizing management strategies in agroecosystems.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the formation and design of this study. Methodology, S.M.T., N.J. (Nataša Joković), J.V., M.I.M. and M.S.; validation, S.M.T., N.J. (Nataša Joković), N.J. (Nikola Jovanović) and M.S.; formal analysis, S.M.T., J.V. and N.J. (Nataša Joković); investigation, S.M.T., N.J. (Nataša Joković) and N.J. (Nikola Jovanović); writing—original draft preparation, S.M.T.; writing—review and editing, S.M.T., N.J. (Nataša Joković), J.V. and N.J. (Nikola Jovanović); supervision, N.J. (Nataša Joković) and S.M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia through contract No. 451-03-137/2025-03/200124.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are presented within the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Singh, A.K.; Bhatt, B.P.; Upadhyaya, A.; Kumar, S.; Sundaram, P.K.; Singh, B.K.; Chandra, N.; Bharati, R.C. Improvement of faba bean (Vicia faba L.) yield and quality through biotechnological approach: A review. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 15264–15271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atnafu, D.; Wobale, Z. Review on effect of seed sources and sizes on faba bean (Vicia faba L.) production in Ethiopia: Review. Am. J. Plant Biol. 2025, 10, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Zhang, F.; Song, Y.; Sun, J.; Bao, X.; Guo, T.; Li, L. Nitrogen fixation of faba bean (Vicia faba L.) interacting with a non-legume in two contrasting intercropping systems. Plant Soil 2006, 283, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jithesh, T.; James, E.K.; Iannetta, P.P.M.; Howard, B.; Dickin, E.; Monaghan, J.M. Recent progress and potential future directions to enhance biological nitrogen fixation in faba bean (Vicia faba L.). Plant Environ. Interact. 2024, 5, e10145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béji, B.; Bouhachem, S.; Bouktila, D.; Mezghani Khemakhem, M.; Salah, R.; Kharrat, M.; Makni, M.; Makni, H. Identification of sources of resistance to the black bean aphid, Aphis fabae Scopoli, in faba bean (Vicia faba L.) accessions. J. Crop Prot. 2015, 2015, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.; Morton, J.D.; Maes, E.; Kumar, L.; Serventi, L. Exploring faba beans (Vicia faba L.): Bioactive compounds, cardiovascular health, and processing insights. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 4354–4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulti, M.; Meseret, C.; Mulatu, W. Reconsidering the economic and nutritional importance of faba bean in Ethiopian context. Cogent Food Agric. 2019, 5, 1683938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, D.A.; Lawes, D.A.; Hawtin, G.C.; Saxena, M.C.; Stephens, J.S. Faba bean (Vicia faba L.). In Grain Legume Crops; Summerfield, R.J., Roberts, E.H., Eds.; William Collins Sons Co., Ltd.: London, UK, 1985; pp. 199–265. [Google Scholar]

- Munyasa, A.J. Evaluation of Drought Tolerance Mechanisms in Mesoamerican Dry Bean Genotypes. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chaker, B.; Ali, B.B.; Hmed, B.N. A review of the management of Aphis fabae Scopoli (Hemiptera: Aphididae). J. Oasis Agric. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 3, 32–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shannag, H.K. Effect of black bean aphid, Aphis fabae, on transpiration, stomatal conductance and crude protein content of faba bean. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2007, 151, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, J. The aphids and their host plants. In Host Plant Catalog of Aphids: Palaearctic Region; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 7–651. [Google Scholar]

- Petrović-Obradović, O. Biljne Vaši (Homoptera: Aphididae) Srbije; Poljoprivredni Fakultet Univerziteta u Beogradu: Beograd, Serbia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman, R.L.; Eastop, V.F. Aphids on the World’s Crops: An Identification and Information Guide, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 2000; p. 476. [Google Scholar]

- Goggin, F.L. Plant-aphid interactions: Molecular and ecological perspectives. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007, 10, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalouf, F.; Hu, J.; O’Sullivan, D.M.; Zong, X.; Hamwieh, A.; Kumar, S.; Baum, M. Breeding and genomics status in faba bean (Vicia faba). Plant Breed. 2019, 138, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincebourde, S.; Ngao, J. The impact of phloem feeding insects on leaf ecophysiology varies with leaf age. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 625689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backus, E.; Lin, P.-A.; Chang, C.J.; Shih, H.-T. Electropenetrography: A new diagnostic technology for study of feeding behavior of piercing-sucking insects. J. Taiwan Agric. Res. 2015, 65, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, I. Stability of Vicia faba L. cultivars and responsible traits for Aphis fabae Scopoli, 1763 preference. Acta Agric. Slov. 2023, 119, 2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goławska, S.; Łukasik, I.; Goławski, A. Black bean aphid populations and chlorophyll composition changes as responses of guelder rose to aphid infestation stress conditions. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2023, 22, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidan, A.; Caulfield, J.; Vuts, J.; Yang, N.; Fisk, I. Detection of aphid infestation on faba bean (Vicia faba L.) by hyperspectral imaging and spectral information divergence methods. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2025, 132, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawełek, A.; Wyszkowska, J.; Cecchetti, D.; Dinka, M.D.; Przybylski, K.; Szmidt-Jaworska, A. The Physiological and Biochemical Response of Field Bean (Vicia faba L. (partim)) to Electromagnetic Field Exposure Is Influenced by Seed Age, Light Conditions, and Growth Media. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziwulska-Hunek, A.; Myśliwa-Kurdziel, B.; Matwijczuk, A.; Szymanek, M. A case study in photosynthetic parameters of perennial plants growing in natural conditions. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljaković-Pajnik, L.; Nikolić, N.; Kovačević, B.; Vasić, V.; Drekić, M.; Orlović, S.; Kesić, L. Aphid Colonisation’s Impact on Photosynthetic and CHN Traits in Three Ornamental Shrubs. Insects 2024, 15, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ederli, L.; Brunetti, C.; Centritto, M.; Colazza, S.; Frati, F.; Loreto, F.; Marino, G.; Salerno, G.; Pasqualini, S. Infestation of Broad Bean (Vicia faba) by the Green Stink Bug (Nezara viridula) Decreases Shoot Abscisic Acid Contents under Well-Watered and Drought Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sytykiewicz, H.; Czerniewicz, P.; Sprawka, I.; Krzyżanowski, R. Chlorophyll content of aphid-infested seedlings leaves of fifteen maize genotypes. Acta Biol. Cracov. Bot. 2013, 55, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcanua, E.; Agapie, O.L.; Gherase, I.; Tănase, B.E.; Dobre, G.; Vînātoru, C. Screening of Vicia faba accessions to abiotic and biotic stresses under field conditions. Acta Hortic. 2023, 1384, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovgard, H.; Stoddard, F.L. Reproductive potential of the black bean aphid (Aphis fabae Scop.) on a range of faba bean (Vicia faba L.) accessions. Legume Sci. 2023, 5, e199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, C.J. A method for estimating populations and counting large numbers of Aphis fabae Scop. Bull. Entomol. Res. 1954, 45, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebi, H. Catalase. In Methods of Enzymatic Analysis; Bergmeyer, H.U., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1974; pp. 673–684. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannopolitis, C.N.; Ries, S.K. Superoxide dismutases: I. Occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 1977, 59, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hageman, R.H.; Reed, A.J. Nitrate reductase from higher plants. In Methods in Enzymology; San Pietro, A., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; Volume 69, pp. 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, R.L.; Packer, L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts. I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1968, 125, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Awasthi, J.P.; Sunkar, R.; Panda, S.K. Determining glutathione levels in plants. In Plant Stress Tolerance: Methods in Molecular Biology; Clifton, N.J., Ed.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlak, J.; Lindsay, R.H. Estimation of total, protein-bound, and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman’s reagent. Anal. Biochem. 1968, 25, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Chlorophylls and Carotenoids: Pigments of Photosynthetic Biomembranes. In Methods in Enzymology; Plant Cell Membranes; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1987; Volume 148, pp. 350–382. [Google Scholar]

- Ramn, C.; Saathoff, A.; Donze, T.; Heng-Moss, T.; Baxendale, F.; Twigg, P.; Baird, L.; Amundsen, K. Expression profiling of four defense-related buffalo grass transcripts in response to chinch bug (Hemiptera: Blissidae) feeding. J. Econ. Entomol. 2013, 106, 2568–2576. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.H.; Pan, M.Z.; Liu, H.R.; Wang, S.H.; Liu, T.X. Antibiosis and tolerance but not antixenosis to the grain aphid, Sitobion avenae (Hemiptera: Aphididae), are essential mechanisms of resistance in a wheat cultivar. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2015, 105, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndakidemi, B.; Mbega, E.; Ndakidemi, P.; Stevenson, P.C.; Belmain, S.R.; Arnold, S.E.J.; Woolley, V. Natural pest regulation and its compatibility with other crop protection practices in smallholder bean farming systems. Biology 2021, 10, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotta, V.; Toma, I.; Forlano, P.; Fanti, P.; Prieto, J.D.; Battaglia, D. The age of tomato plants affects the development of Macrosiphum euphorbia (Thomas, 1878) (Hemiptera) colonies. Agron. Colomb. 2021, 39, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M. Plant oxidative stress: Biology, physiology and mitigation. Plants 2022, 11, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soffan, A.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Aldawood, A.S. Peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase activity in moderate resistant and susceptible Vicia faba induced by Aphis craccivora (Hemiptera: Aphididae) infestation. J. Insect Sci. 2014, 14, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Štolfa, I.; Pfeiffer, T.Ž.; Špoljarić, D.; Teklić, T.; Lončarić, Z. Heavy metal-induced oxidative stress in plants: Response of the antioxidative system. In Reactive Oxygen Species and Oxidative Damage in Plants Under Stress; Gupta, D., Palma, J., Corpas, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 127–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Sun, X.; Xue, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q. Antioxidant enzyme responses induced by whiteflies in tobacco plants in defense against aphids: Catalase may play a dominant role. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.R.; Chaitanya, K.V.; Vivekanandan, M. Drought-induced responses of photosynthesis and antioxidant metabolism in higher plants. J. Plant Physiol. 2004, 161, 1189–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San, S.; Dodda Chowdappa, S.; Krishnan, V.; Awana, M.; Singh, A.; Bhowmik, A.; Singh, R.; Chander, S. Effects of Helicoverpa armigera (Hubner) infestation on metabolic sensors dynamics in chickpea. Allelopath. J. 2022, 57, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunos, V.; Cséplő, M.; Seress, D.; Eser, A.; Kende, Z.; Uhrin, A.; Bányai, J.; Bakonyi, J.; Pál, M.; Mészáros, K. The stimulation of superoxide dismutase enzyme activity and its relation with the Pyrenophora teres f. teres infection in different barley genotypes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusnierczyk, A.; Winge, P.; Jørstad, T.S.; Reese, J.C.; Troczyńska, J.; Bones, A.M. Biochemical and transcriptional responses of Medicago truncatula to aphid feeding. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2008, 21, 647–658. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, X. Antioxidant enzyme activities and ROS dynamics in potato leaves during Phytophthora infestans infection. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 142, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Q. Oxidative stress responses of wheat to grain aphid (Sitobion avenae) feeding. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2020, 14, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, K. Glutathione-associated regulation of plant growth and stress responses. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2005, 7, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, N.A.; Aref, I.M.; Duarte, A.C.; Pereira, E.; Ahmad, I.; Iqbal, M. Glutathione and proline can coordinately make plants withstand the joint attack of metal(loid) and salinity stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Suzuki, N.; Ciftci-Yilmaz, S.; Mittler, R. Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signalling during drought and salinity stresses. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundararajan, P.; Manivannan, A.; Ko, C.H.; Jeong, B.R. Silicon enhanced redox homeostasis and protein expression to mitigate the salinity stress in Rosa hybrida ‘Rock Fire’. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 37, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luan, Q.; Jiang, J.; Li, Y. Prediction and utilization of malondialdehyde in exotic pine under drought stress using near-infrared spectroscopy. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 735275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, S.; Zhu, M.; Chen, S. Proteomics of Arabidopsis redox proteins in response to methyl jasmonate. J. Proteomics 2009, 73, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio-Tejo, P.; Sánchez-Díaz, M. Nodule and leaf nitrate reductases and nitrogen fixation in Medicago sativa L. under water stress. Plant Physiol. 1982, 69, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Komy, H.; Hamdia, M.; Abd El-Baki, G.K. Nitrate reductase in wheat plants grown under water stress and inoculated with Azospirillum spp. Biol. Plant. 2003, 46, 281–287. [Google Scholar]

- Mur, L.A.J.; Mandon, J.; Persijn, S.; Cristescu, S.M.; Moshkov, I.E.; Novikova, G.V.; Hall, M.A.; Harren, F.J.M.; Hebelstrup, K.H.; Gupta, K.J. Nitric oxide in plants: An assessment of the current state of knowledge. AoB Plants 2013, 5, pls052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, D.A.; Oliva, M.A.; Ruiz, H.A.; Martinez, C.A. Contribution of proline and inorganic solutes to osmotic adjustment in cotton under salt stress. J. Plant Nutr. 2001, 24, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, F.; Akram, N.A.; Ashraf, M. Osmoprotection in plants under abiotic stresses: New insights into a classical phenomenon. Planta 2019, 251, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Zhu, J.K. Molecular and genetic aspects of plant responses to osmotic stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2002, 25, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinari, H.B.C.; Marur, C.J.; Daros, E.; De Campos, M.K.F.; De Carvalho, J.F.R.P.; Filho, J.C.B.; Pereira, L.F.P.; Vieira, L.G.E. Evaluation of the stress-inducible production of proline in transgenic sugarcane (Saccharum spp.): Osmotic adjustment, chlorophyll fluorescence and oxidative stress. Physiol. Plant. 2007, 130, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiral, T.; Turkan, I. Does exogenous glycinebetaine affect antioxidative system of rice seedlings under NaCl treatment? J. Plant Physiol. 2004, 161, 1089–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vendruscolo, E.C.; Schuster, I.; Pileggi, M.; Scapim, C.A.; Molinari, H.B.; Marur, C.J.; Vieira, L.G.E. Stress-induced synthesis of proline confers tolerance to water deficit in transgenic wheat. J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 164, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzetti, M.; Bertolini, E.; Trovato, M. Proline Metabolism Genes in Transgenic Plants: Meta-Analysis under Drought and Salt Stress. Plants 2024, 13, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Wang, D.; Peng, Y.; Peng, D.; Li, Z. Cross-Stressful Adaptation to Drought and High Salinity Is Related to Variable Antioxidant Defense, Proline Metabolism, and Dehydrin b Expression in White Clover. Agronomy 2025, 15, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannag, H. Influence of black bean aphid, Aphis fabae Scopoli, on growth rates of faba bean. World J. Agric. Sci. 2007, 3, 344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, M.W.; Ghani, H.; Ayyub, M.; Ali, Q.; Ahmad, H.M.; Faisal, M.; Ali, A.; Qasim, M.U. Performance of some wheat cultivars against aphid and its damage on yield and photosynthesis. J. Glob. Innov. Agric. Soc. Sci. 2019, 7, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Montano, J.; Reese, J.; William Schapaugh, W.; Campbell, L. Chlorophyll Loss Caused by Soybean Aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae) Feeding on Soybean. J. Econ. Entomol. 2007, 100, 1657–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Baky, Y.R.; Abouziena, H.F.; Amin, A.A.; Rashad El-Sh, M.; Abd El-Sttar, A.M. Improve quality and productivity of some faba bean cultivars with foliar application of fulvic acid. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2019, 43, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherin, G.; Aswathi, K.P.R.; Puthur, J.T. Photosynthetic Functions in Plants Subjected to Stresses Are Positively Influenced by Priming. Plant Stress 2022, 4, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).