Abstract

This bibliometric study analyses scientific output over the last 10 years on music using the following keywords “youth”, “culture” and “education”. Based on a sample of 904 documents extracted from the Web of Science database, the research analyses emerging trends in the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia, in patterns of collaboration between authors and countries, and the main topics related to music, culture, identity and young people. To this end, we have applied a quantitative bibliometric methodology, using the Biblioshiny tool from RStudio, generating frequency network maps, multiple correspondence analysis and thematic graphs showing the relationships between keywords and those used by authors. The results show that the United States is the leading scientific producer in this field. The two main terms obtained in the analysis are popular culture and popular music, in addition to related concepts such as identity, gender and education, among others. In conclusion, this study shows how globalisation alters popular culture by influencing the behaviour of adolescents. The research is limited in terms of contributions from the Global South, given the database used, but it is presented as an inclusion in future lines of research.

1. Introduction

Adolescence is a stage marked by numerous personal and developmental changes, with mental health issues currently standing out. This reality has sparked growing interest in identifying the everyday skills that adolescents use to promote their well-being []. In this process, the influence of peer groups and the impact of social media are playing an increasingly important role in today’s society []. It is at this stage that adolescents begin to realise how music can be used to achieve different personal goals, influence mood, disconnect from their surroundings, and create and strengthen social bonds, all of which are particularly relevant at this stage of life. This function of music has been enhanced in the last two decades, thanks to the advancement and integration of new technologies in the daily lives of young people and artificial intelligence (AI) [,,]. The society in which we live is increasingly complex and constantly changing, and these changes are also taking place in music. Young people use song lyrics to express all the issues of the moment [].

Music has always been and continues to be present in society, especially in so-called ‘popular music’, understood as the set of commercial musical styles, regardless of their cultural and economic origin, which are the most influential among adolescents []. This music becomes a means of representation and identification for them []. Proof of this can be found, for example, in popular urban genres such as rap, hip-hop and reggaeton. The lyrics of these songs reproduce the gender stereotypes prevalent in each social and cultural context []. Music has the ability to generate emotions such as tranquillity, euphoria, relaxation, enthusiasm or happiness, making it a valuable resource for improving mood and personal well-being. For this reason, adolescents use it as an escape in times of stress, especially during exams, to distract themselves from daily worries, pass the time or simply avoid boredom, which are common experiences at this stage of development [,].

The emergence of new cultural forms is driving a break with stereotypes associated with traditional identities, both female and male, and a renewal of what is considered masculine identity []. Social change not only challenges inherited roles but also redefines how gender identities are constructed and lived []. Although music is relevant to all ages, we know that it plays a particularly significant role in the lives of young people, as it contributes to the formation of social identity [,] as it is considered a learning tool [].

There are studies in which the cultural component of music has been analysed, cultural studies, case studies and empirical experiments that explore the impact of music on different social groups [,,,,,,,], which adopt a sociological approach, focusing on the musical experience of listeners, influenced by their interaction with the media []. Globalisation, increased cultural diversity, and the resurgence of ethnic, religious, and gender identities have driven significant developments in research on intercultural communication []. This phenomenon is also reflected in the field of music education. New technologies, the Internet, and now (AI) facilitate the expansion of knowledge and values of music from different cultures and/or local culture and the construction of new musical cultural identities [,].

For example, from a global perspective, the studies by [,] stand out, addressing the use of AI, the Industrial Revolution 6.0, and mobile phones. At the local level, Paschalidou []’s research explores tools such as three-dimensional motion capture, video, and videoconferencing, which we know as ‘convergence culture.’ Authors such as [] argue that the link with a culture’s own music can strengthen ethnic identity and become a mechanism of resilience in the face of the changes brought about by acculturation.

According to [], music is one of the cultural manifestations that best expresses and establishes relationships between cultures and societies, reflecting the particularities of each one, hence the importance of the concept of urban popular music and popular culture, and its inclusion in the school curriculum []. Crossman [] defines popular culture as a set of cultural products consumed by most of society, such as music, new media culture, film, television, fashion and radio.

In general, popular culture refers to the ‘culture of the people’ that prevails in a particular society at a particular time. The way people interact in their daily lives defines popular culture. Music, television programmes, fashion, food and our style of dress are examples of topics in popular culture. Thus, this comprehensive and multidimensional approach has also been adopted in the present study, under the premise that music exerts a complex influence on the development of youth personality [].

From the perspective of the sociology of music, it is argued that the musical experience generates spaces for cultural activity and plays an active role in society, recognising that music is a symbolic activity that must be experienced and shared []. In this sense, music enables adolescents to identify and reflect themselves in the models proposed by the music industry when belonging to a group, thereby fulfilling a dual function: on the one hand, socialising, facilitating understanding and cohesion among members who share the same cultural codes, and on the other hand, a differentiating function, highlighting the particular and genuine characteristics of each community through unique codes [].

This study uses quantitative bibliometric methodology to analyse the evolution of scientific research on youth, music, culture and education using the keywords “music criticism”, “musicology”, “new religious”, “popular culture”, “popular music” and “youth culture”. The aim is to investigate the perspectives from which musical education for young people has been approached in the sociocultural and educational scientific world over the last 10 years, providing a general overview that allows us to identify the concepts that are linked to this type of education.

2. Methods

This research was conducted using a quantitative-bibliometric methodology through the Web of Science (WOS) database, with a total of 904 scientific documents belonging to the fields of Education, Social Sciences, and Musicology forming our study sample.

The search for information was carried out in the database using the title of the article, the abstract and keywords. The final search function used the boolean operators “and” and “or” and was “youth” and “music” and “culture” and “education” or “music criticism” or “musicology” or “new religious” or “popular culture” or “popular music” or “youth culture”. The search covers the last 10 years, that is, the period between 2016 and 2025.

The Biblioshiny interface of RStudio v.4.0.4 [] was used to create and display the graphs, clusters and thematic maps, and the data analysis was carried out using the following variables: information sources, authors, countries, author’s keywords and keywords plus.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the sample of 904 documents. The information collected includes the main sources of reference, the number of keywords in their two types, and authors as the main variables to be investigated. When we talk about the Authors section, which analyses authors and their productivity, we find 994, which is the total number of researchers identified in the set of publications in this research. There are 1158 author appearances, i.e., the number of times authors are repeated in different documents, reflecting the total level of participation. This is followed by 650 authors with sole authorship and 344 articles with collective authorship.

Table 1.

Main information of the sample.

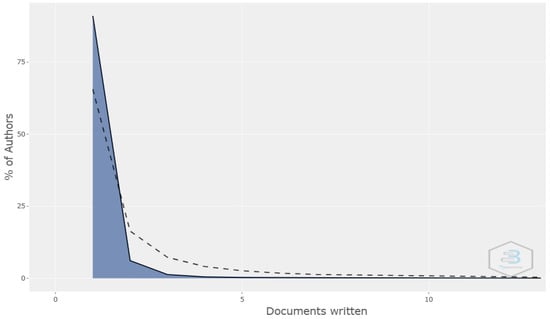

In Figure 1, the analysis of scientific productivity shows a clear downward trend: more than 75% of authors have published a single work, revealing a largely sporadic contribution. This distribution follows Lotka’s law [], which states that as the number of published articles increases, the frequency of authors producing that number of publications decreases. In this case, it can be seen that only a small group of authors exceed five articles, and the frequency tends towards zero after ten published works. Thus, the structure of unequal productivity is an effect of the social and institutional functioning of contemporary science itself, where prestige and academic visibility tend to be concentrated around centres of high productivity and intellectual leadership.

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of scientific productivity by authors.

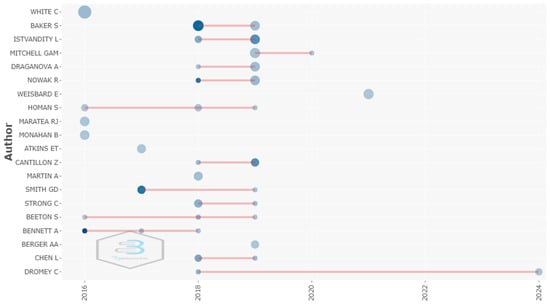

Figure 2 highlights the most prominent authors whose scientific work has been carried out in specific years and in a shorter period of time or who have published more regularly. The graph shows bubbles of different sizes and colours, with the largest corresponding to eight published articles, the medium-sized ones to two articles, and the smallest ones to one article and the blue colour refer to the highest concentration in that year of production where the keywords of the research are accumulated. According to the data, we observe that there is one major producer, White C., with more than eight documents related to the subject studied and concentrated in 2016, followed by Nowak R in 2021, Baker S. and Istvandity L. with similar output between 2018 and 2019. The rest of the authors, with between two and seven articles, can be considered medium-sized producers on this topic, concentrated between 2016 and 2019. Only Dromey C. maintained a constant output between 2018 and 2024.

Figure 2.

Production of leading authors over time.

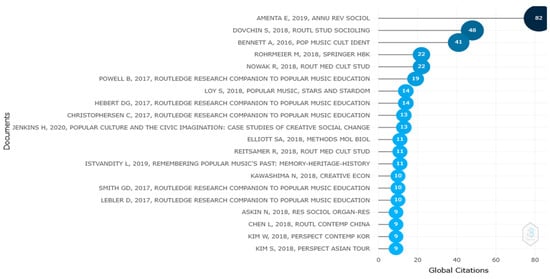

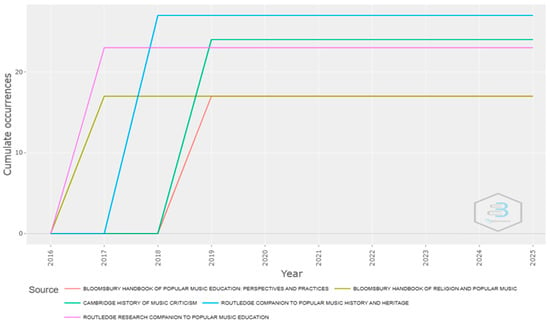

Figure 3 distinguishes between journals that have experienced the greatest growth over the last 10 years and those that show the highest number of authors of published articles. All the journals in the graph have between 9 and 82 citations. The most relevant journal, with 82 citations, is Annual Review of Sociology, followed by 48 and 41 citations for Routledge Stud Sociolinguistics and Pop Music, Culture and Identity, respectively. Continuing with the research topic, Figure 4 shows the journals with the highest annual growth by the scientific community, starting with Routledge Companion to Popular Music History and Heritage, Cambridge History of Music Criticism, some of which share the same editorial line, with publications such as Routledge Research Companion to Popular Music Education and, finally, Bloomsbury Handbook of Religion and Popular Music. Figure 5 shows how the most frequently used term is Popular Music.

Figure 3.

Most relevant journals for citations.

Figure 4.

Annual growth of the top 5 academic journals.

Figure 5.

Growth of keywords plus.

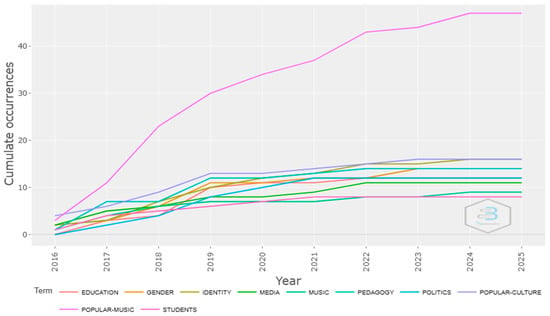

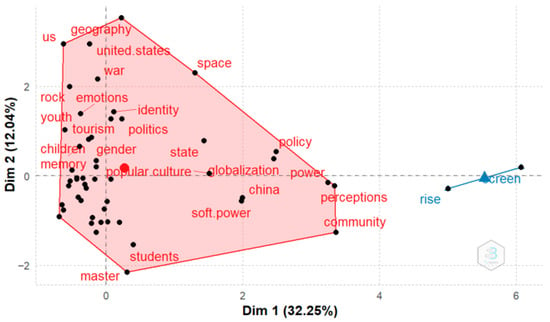

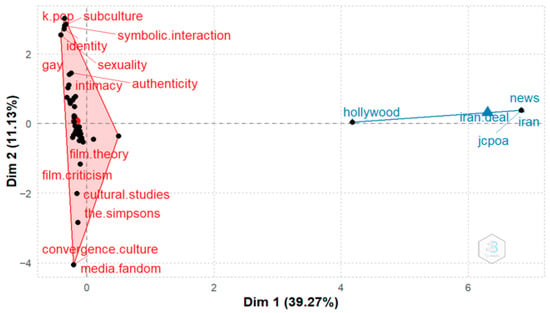

Continuing with this theme, we will develop a factorial analysis of the conceptual structure of music and its relationship with aspects such as Youth, Culture, Education, Music Criticism, Musicology, New Religious, Popular Culture, Popular Music, and Youth Culture. The two types of keywords provide precise information on the topics of the articles. On the one hand, there are the keywords plus, which are automatically generated by the databases from the titles of the cited documents, and the author’s keywords, which are words extracted from different thesauruses, providing a more specific view of the phenomenon studied. Using the Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) method for the two types of keywords, the aim is to reduce the data to latent factors and a lower dimensionality. Two clusters have been formed in both maps, one blue and one red. It is important to look at the location of the clusters on the plane, as this determines their proximity to the origins of the coordinate axes. This location reflects the average position of all column profiles, which in turn indicates the predominant and shared themes and trends within the field of study analysed. In Figure 6, Dimension 1 has the highest variance with 32.25%, while Dimension 2 has 12.04%. Following the same pattern, in Figure 7, Dimension 1 shows the highest variance with 39.27%, while the percentage of variance for Dimension 2 is 11.13%.

Figure 6.

Map of the conceptual structure of the topic music and young people based on the author’s keywords.

Figure 7.

Map of the conceptual structure of the topic music and young people based on keywords plus.

Figure 6, corresponding to the conceptual structure map of the author’s keywords, shows that the main component in the red cluster is popular culture, around which we find related aspects such as gender, youth, emotions, identity, and globalisation, mainly. However, in the blue cluster, the main component would be “screen”, and related to the concept of elevation, it can be understood as audiovisual concerts where images are projected to the rhythm of the music.

However, in the map on keywords plus (Figure 7), in the red cluster we find terms such as sexuality, identity, symbolic interaction, subculture, films. In the case of the blue cluster, it is quite specific, we find the term Hollywood and news mainly related to Iranian cinema and soundtracks.

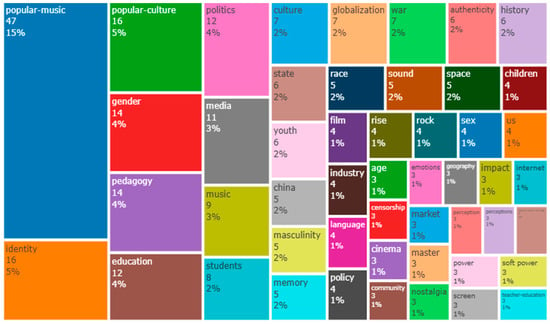

Figure 8, in TreeMap format, visually shows the most frequent topics in scientific production related to music and young people. The largest block is “popular music” (47 mentions), which is consistent with the way the records were extracted from the database. The next two largest blocks are “identity” and “popular culture” (16 mentions each). It should be noted that the following mentions, such as “gender” and “pedagogy” (14 each) and “education” (12 mentions), highlight the connection between music and culture and young people.

Figure 8.

TreeMap of keywords plus.

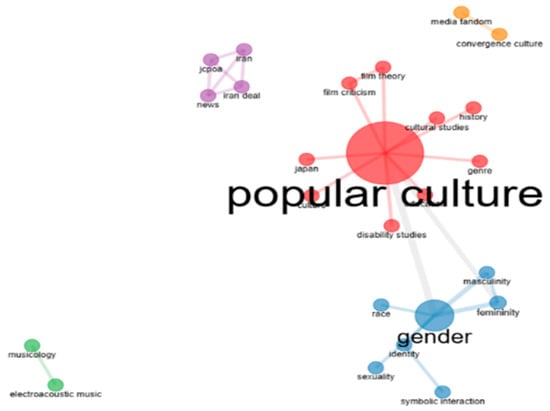

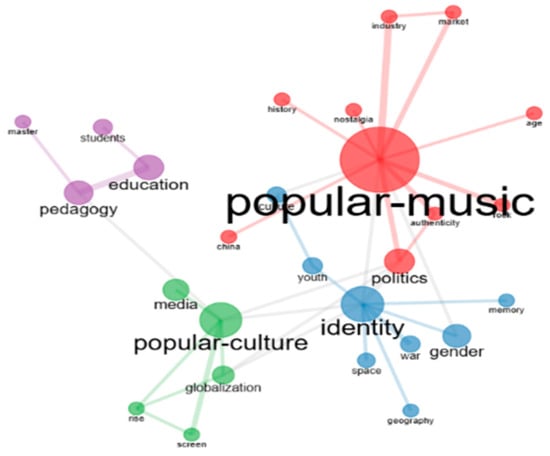

When we analyse Figure 9, we see that the term “popular culture” dominates the graph in size, indicating that it is the keyword most frequently mentioned by the authors. Another prominent term is “gender”, reflecting the prevalence of the concept of identity when we talk about young people and music today. The central position of nodes such as “popular culture” and “gender” highlights their strong interconnection with the rest of the concepts, while terms such as “electroacoustic-music” and “musicology” appear on the periphery, being less interconnected but maintaining relevance in specific niches. This indicates that authors focus more on the use of music from a more cultural perspective, closer to the reality of citizens, young people and their musical identity. As for the colour-coded thematic groups, the red group surrounding “popular culture” includes terms related to “disability studies”, “cultural studies”, “film criticism” and “film theory”, due to the intersection between education, music and young people. In contrast, the blue cluster focuses more on the concept of “gender” in young people, highlighting such current terms as masculinity, femininity, race, identity, sexuality, and symbolic interaction. The orange cluster is noteworthy for terms such as “media fandom”, which refers to fan communities that form around media works, and “convergence culture”, terms thatthat refers to the intersection between traditional and digital media, that is, a cross-cultural phenomenon between producers and consumers converging in a connected ecosystem. In contrast, in the keyword graph (Figure 10), the dominant terms are “pop music”, “popular culture”, “identity”, “pedagogy”, and “education”. In addition, this keyword graph shows a broader thematic diversity, with nodes covering topics ranging from politics, culture, identity, gender, war, youth, education, pedagogy, master’s degrees, students, and globalisation, among others. The terms tend to be more related to pedagogical aspects of music education that are of greater concern to young people today, while in the author’s keyword graph, the terms are more interconnected with cultural aspects.

Figure 9.

Concurrency network of the author’s conceptual structure (author’s keyword).

Figure 10.

Conceptual structure concurrency network (keywords plus).

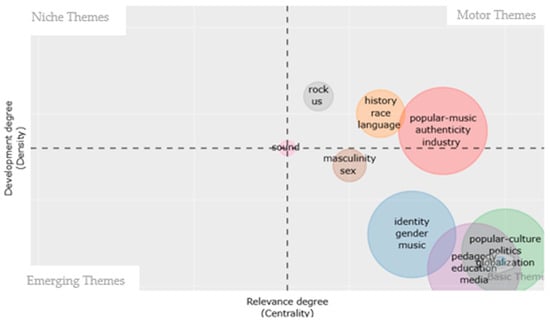

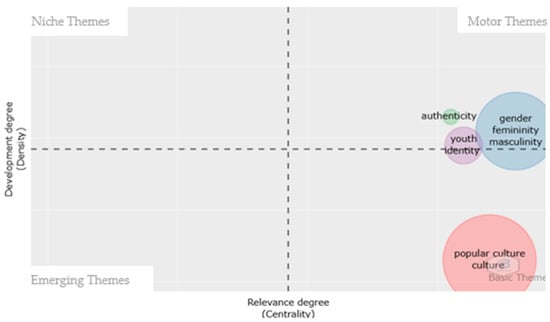

Figure 11 shows the distribution of keywords plus according to two parameters: degree of development (density) and degree of relevance (centrality). Among the “motorthemes” (upper right quadrant), keywords such as “popular music”, “authenticity” and “industry” stand out, forming the largest bubble, which indicates that these are central themes in the research, followed by the size of the bubble, the terms “history”, “rock” and “language” and, lastly, the term “rock”. The concept “sound” is at the centre of the thematic map. In the lower right axis, we find the “basic themes” in bubbles of equal size, and therefore of equal importance, where we see concepts such as “popular culture”, “politics”, “globalisation”, “identity”, “gender”, “music”, “pedagogy”, “education”, “masculinity” and “sex”. In Figure 12, the author’s most central and developed keywords include terms such as “gender”, “femininity” and “masculinity”, forming the largest cluster, followed by the medium cluster with the terms “youth” and “identity” and the last bubble with the concept of “authenticity”, which are also found in the motor themes quadrant. And on the “basic themes” axis, we find the terms “popular culture” and “culture”.

Figure 11.

Thematic map of keywords plus according to conceptual structure.

Figure 12.

Thematic map of the author’s keywords according to the conceptual structure (author’s keywords).

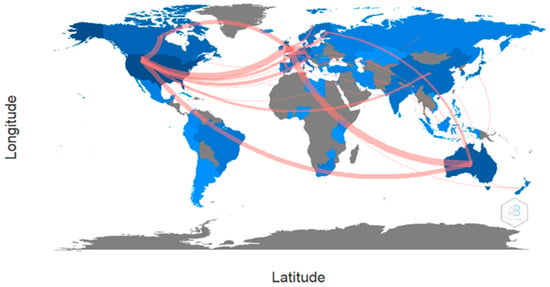

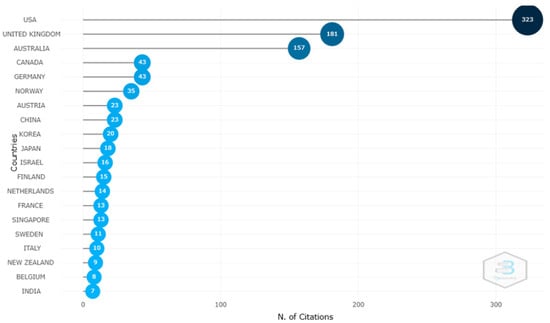

The distribution of collaborations between countries is shown in Figure 13. With regard to international collaborations, most of these took place between the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia. In terms of the language of publication, most articles were published in English. Production in Spanish accounted for 1% of articles; there are hardly any publications on this subject, hence the novelty of continuing to research it. This is also reflected in Figure 14, where we see that the United States is the country with the most citations on the research topic we are dealing with, followed by the United Kingdom with 181 citations and Australia in third place with 157.

Figure 13.

Map of the frequency of collaborations among countries.

Figure 14.

List of most cited countries.

4. Discussion

When discussing music and teenagers associated with culture, education, music criticism, musicology, ‘new religious’, ‘popular culture’, ‘popular music’ and ‘youth culture’, we have observed that this has been a booming area of research over the last 10 years. The scientific journals that have been used as sources of information belong to the Web of Science database, and their titles allow us to see the editorial lines along which the published works have been carried out. Scientific output has been analysed, highlighting the most productive authors and specialists in the field, given their regularity and involvement in this line of research over time, as well as the most productive countries. Through this, we observe that research on music, adolescents, culture and education is currently a growing trend. This multidimensional approach highlights music as a pedagogical resource capable of fostering creativity, cooperation, and emotional expression, which are essential aspects for the balanced development of students and for promoting cross-cutting skills that transcend the strictly academic sphere []. Adolescence is understood as a social construct that arises from identification with a group that shares common characteristics, values, and beliefs. This stage is not only a biological phenomenon, but also a sociocultural process closely linked to the context in which it develops, thus shaping the individual’s identity []. All of this is corroborated by the most relevant journals in terms of the total number of articles published and growth over time and keywords.

In Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA), the map of the conceptual structure of the topic of music and teenagers based on the keywords used by the authors identifies the main component that refers to the concept of popular culture, around which the rest of the topics develop, such as young people, emotions, identity and globalisation, results that are confirmed as we have seen above [], among others. However, if we look at the same map from the perspective of Keywords Plus, we find terms such as sexuality, symbolic interaction, subculture, films and news mainly related to Iranian cinema and soundtracks. hence an Iranian study that identifies young people’s preferences in self-care activities, such as listening to music, can be used to develop intervention programmes for adolescents to improve their lifestyle and, consequently, their emotional well-being according to their needs and situation [].

When we talk about the author’s conceptual framework, the most prominent term is popular culture, and according to the keyword plus concurrence, it is popular music. This must be understood in the context of a mass society, where cultural democratisation is promoted []. As well as thematic trends with a focus on identity [,], as well as a certain interest in the terms gender, education, pedagogy, and convergence culture [] and fandom, where an emotionally positive, personal and deep connection with a media element of popular culture is demonstrated [,], are results consistent with previous reviews [,,,,,,,].

5. Conclusions

This bibliometric study analysed scientific output on music, young people related to culture, identity and gender, mainly between 2016 and 2025. In terms of productivity, the results follow Lotka’s law []. This finding is consistent with the trends observed in most scientific fields. Based on a sample of 904 documents extracted from the WoS database, the study evaluates emerging trends, patterns of collaboration between authors and countries, and the main topics related to the terms researched. To this end, the Biblioshiny tool from RStudio was used to generate structural concept maps, frequency networks, and thematic graphs that visualise the relationships between keywords and international collaborations. The results showed that the country leading in terms of scientific productivity is the United States, followed by the United Kingdom and Australia. This study provides an overview of trends in music and young people over the last 10 years, highlighting opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration.

As for keywords, analysis of the keywords plus and the author’s keywords shows convergence around two themes, as main axes, which are Popular Culture and Popular Music, respectively, with the research focusing on how music acts on young people to deal with emotions, the advance of globalisation, the world of social networks, fans and how it manifests itself in music education. However, it was observed that the author’s plus keywords tend to present greater thematic diversity, such as gender, media fandom, convergence culture, films, musicology, among others, while the keywords focus more on topics such as identity, education and pedagogy. This study shows how globalisation and social transformation processes are accelerating and modifying the components of popular culture [], influencing the ways of thinking and acting of adolescents, as well as the collective mentality. Popular music has been gaining ground in formal and informal education. Although it remains on the margins of traditional music education, it promotes inclusion and diversity in curricula, reflecting the cultural and musical variety of students. This calls for a pedagogical change that combines academic traditions with innovations based on real musical experiences. Education with popular music is crucial for renewing and diversifying the educational and cultural paradigm, promoting more inclusive and culturally responsible teaching [,]. However, we encounter the limitations of policy proposals that are far removed from the dynamics and specific needs of the educational or cultural sphere, which hinders their impact and their translation into concrete and sustainable results.

It should be noted that the limitations of this research lie in the consideration of more databases to explore and increasing the number of documents for the sample. While it is true that the coverage provided by the Web of Science database for the field of Musicology, the social sciences and education is exhaustive, it may not fully cover research in this interdisciplinary field, which generates a Eurocentric and neocolonial bias in academic production, overshadowing contributions from the Global South (Latin America, Africa, parts of Asia), where very specific and equally relevant youth and musical experiences are developed. We have also encountered the limitations of the bibliometric tool in the analysis of some results. However, this is a fairly broad field of study in which it is difficult to delve deeply into any specific discipline or area of knowledge. Therefore, for future studies, it would be necessary to expand the consultation of specialised databases such as Scopus or Eric, SciELO, among others, which can offer us a more specific and detailed view of the state and interest of the scientific community in non-Western contexts on aspects that directly relate forms of musical expression to the interrelationships between music, identity and adolescence, as well as the link between music and the mental health of adolescents in terms of its cultural aspect.

Author Contributions

R.P.L., M.L.S. and M.d.C.O.G. conceptualization. M.d.C.O.G., methodology and analysis of the data. M.L.S. and R.P.L. writing—review and editing. M.L.S., supervision. All authors contributed to data interpretation in the analysis. R.P.L., M.L.S. and M.d.C.O.G. wrote the paper with significant input from M.L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project “Iluminando oportunidades interseccionales: aprendizaje para la mejora educativa y laboral del uso de la inteligencia artificial (IA) en jóvenes [Illuminating intersectional opportunities: learning for educational and professional improvement through the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in young people]” MEL-14-UGR24, financed by “Proyectos de Investigación UGR/Ciudad Autónoma de Melilla 2024”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

The authors stated that the study does not require any ethical approval since it is based on review of existing literature.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the second author via mlsuarez@ugr.es (M.L.S.).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fernández, J.F.; García, M.; Gamella, D.J. Mood regulation through music in adolescence. Eur. Public Soc. Innov. Rev. 2024, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilska, T.A.; Holkkola, M.; Tuominen, J. The role of social media in the creation of young people’s consumer identities. Sage Open 2023, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, S.S.; Requena, S.O. Música, identidad de género y adolescencia: Orientaciones didácticas para trabajar la coeducación. Epistemus. Rev. Estud. Mus. Cognición Cult. 2019, 7, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marí, V.M.; Bonete, B.; Ceballos, G.; Rengel, J.; Egoscozabal, M. Adolescentes y Abuso de las Tecnologías de la Información y de la Comunicación en la Provincia de Cádiz. 2016. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10498/18340 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Moreno, A. Informe Juventud en España 2012; Instituto de la Juventud: Madrid, España, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, J.S. Influencia de la música en el comportamiento de los adolescentes. Cienc. Acad. 2023, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, G.F.; Biasutti, M.; MacRitchie, J.; McPherson, G.E.; Himonides, E. The Impact of Music on Human Development and Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, C.F.; Montes, M.D.L.Á. Músicas populares, cognición, afectos e interpelación: Un abordaje socio-semiótico. Oído Pensante 2020, 38–64. Available online: https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/bitstream/handle/11336/141045/CONICET_Digital_Nro.583781f1-21f2-4cfa-8edf-83ceda5f4cf7_A.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y (accessed on 12 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Oriola, S.; Gustems, J.; Filella, G. Las bandas y corales juveniles como recurso para el desarrollo integral de los adolescentes. Revi. Electron. Complut. Investig. Educ. Music. 2018, 15, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriola, S.; Gustems, J. Música y emoción, un binomio inseparable. Rev. Int. Educ. Emoc. Bienestar 2021, 1, 11–24. Available online: http://ri.ibero.mx/handle/ibero/5954 (accessed on 4 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.S. Music Preferences and the Adolescent Brain: A Review of Literature. Update Applicat. Res. Music Educ. 2016, 35, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.I.; Lauer, J.E.; Tanenbaum, C.; Burr, L. The development of children’s gender stereotypes about STEM and verbal abilities: A preregistered meta-analytic review of 98 studies. Psychol. Bull. 2024, 150, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Mayén, R.; Montes-Berges, B. Análisis de los estereotipos de género actuales. An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrota, S.; Reić, I. Music preferences with regard to music education, informal influences and familiarity of music amongst young people in Croatia. Br. J. Music Educ. 2017, 34, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drovenik, T.; Blažić, M.; Kovačič, B. Influence of Factors on the Development of Outstanding Musical Talent—A Case Study. Pedagoš. Obz. 2020, 35, 54–70. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366185484_Influence_of_Factors_on_the_Development_of_Outstanding_Musical_Talent_-_a_Case_Study (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Perić, D.; Lazić, S.; Matović, M. Popular Music in Young People’s Social and Cultural Values Formation. Pedagoš. Obz. 2021, 36, 120–133. Available online: https://www.dspo.si/index.php/dspo/article/view/47 (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Athanasopoulos, G.; Tan, S.L.; Moran, N. Influence of literacy on representation of time in musical stimuli: An exploratory cross-cultural study in the UK, Japan, and Papua New Guinea. Psychol. Music 2016, 44, 1126–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández de Juan, T. Psychotherapy Music therapy for women survivors of intimate partner violence: An intercultural experience from a feminist perspective. Arts Psychot. 2016, 48, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupacher, J.; Witek, M.A.; Vuoskoski, J.K.; Vuust, P. Cultural familiarity and individual musical taste differently affect social bonding when moving to music. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitaker, N. Student-created musical as a community of practice: A case study. Mus. Educ. Res. 2016, 18, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements-Cortés, A. Artful wellness: Attending chamber music concert reduces pain and increases mood and energy for older adults. Arts Psychother. 2017, 52, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, K.; Van Niekerk, C.; Le Roux, L. Drumming as a medium to promote emotional and social functioning of children in middle childhood in residential care. Music Educ. Res. 2016, 18, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Stegemann, T. Music listening for children and adolescents in health care contexts: A systematic review. Arts Psychother. 2016, 51, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soley, G.; Spelke, E.S. Shared cultural knowledge: Effects of music on young children’s social preferences. Cognition 2016, 148, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.L.; Cohen, A.; Cohen, A.J.; Lipscomb, S.D.; Kendall, R.A. The Psychology of Music in Multimedia; University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ovchinnikova, Y.S. Intercultural competence in modern education: Experience of building a music-orientated model. Music Art Educ. 2022, 10, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, H.; Karlsen, S.; Partti, H. Visions for Intercultural Music Teacher Education; Springer Open: Londres, Inglaterra, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, G.; Cortezo, A.; Corpus, M.L.A. Artificial Intelligence and the Integration of industrial Revolution 6.0 in Ethnomusicology: Demands, Interventions and Implications. Musicologist 2024, 8, 75–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckles, R. Migration, music and the mobile phone: A case study in technology and socio-economic justice in Sicily. Ethnomusicol. Forum. 2021, 30, 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschalidou, S. Technology Mediated Hindustani Dhrupad Music Education: An Ethnographic Contribution to the 4E Cognition Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.; Carlo, G.; Davis, A.N. The Associations Between Culture-Related Stressors and Prosocial Behaviors in U.S. Latino/a College Students: The Mediating Role of Cultural Identity. Adolescents 2025, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettl, B. The Study of Ethnomusicology: Thirty-Three Discussions; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bracknell, C.; Barwick, L. The Fringe or the Heart of Things? Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Musics in Australian Music Institutions. Musicol. Aust. 2020, 42, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossman, A. Sociological Definition of Popular Culture: The History and Genesis of Popular Culture. Retrieved on 29 April 2025. Available online: https://www.thoughtco.com/popularculture-definition-3026453 (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Kumar, A. A Study of Popular Culture and its Impact on Youth’s Cultural Identity. Creat. Launcher 2022, 7, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormigos, J. Estudio de los factores comunicativos que definen la percepción social de la música en la juventud española. El Oído Pensante 2023, 11, 32–58. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8889120 (accessed on 27 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.; Ballesteros, J.C. Jóvenes, Ocio y TIC. Una Mirada a la Estructura Vital de la Juventud Desde los Referentes del Tiempo Libre y las Tecnologías; Centro Reina Sofía Sobre Adolescencia y Juventud, FAD: Madrid, España, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granado, F.S. Aplicación de la ley de Lotka en los trabajos de ascenso del personal académico de la universidad nacional abierta. En el período 2000–2004. Rev. Pensam. Academ. 2019, 2, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremades-Andreu, R.; García-Sanz, J. Proyectos Musicales En Secundaria: Una Herramienta Para Facilitar la socialización en Adolescentes. Prax. Saber 2022, 13, e13058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parella, S.; Contreras, P.; Pàmies, J. La reconstrucción de la identidad musulmana de las jóvenes de ascendencia marroquí con estudios superiores en Cataluña. Rev. Estud. Soc. 2022, 1, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremades, R.; Lorenzo, O.; Turcu, I. Raï music as a generator of cultural identity among young magrebies. Int. Rev. Aesthet. Sociol. Music. 2015, 46, 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadzadeh, M.; Alizadeh, T.; Awang, H.; Mohammadzadeh, Z.; Mirzaei, F.; Stock, C. Knowledge, Perspectives, and Priorities Regarding Self-Care Activities: A Population-Based Qualitative Study among Iranian Adolescents. Adolescents 2021, 1, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Company, J.F.; García-Rodríguez, M.; Alvarado, J.M.; Jiménez, V. Adolescencia y música, una realidad positiva. In La Convivencia Escolar: Un Acercamiento Multidisciplinar a las Nuevas Necesidades; Pérez, M.C., Molero, M.M., Martos, A., Barragán, A.B., Simón, M.M., Sisto, M., Del Pino, R.M., Tortosa, B.M., Gázquez, J.J., Eds.; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Duffett, M. Understanding Fandom: An Introduction to the Study of Media Fan Culture; Bloomsbury: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Duffett, M. Fan Words. In Popular Music Fandom: Identities, Roles and Practices; Duffett, M., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 146–164. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.D.; Moir, Z.; Brennan, M.; Rambarran, S.; Kirkman, P. The Routledge Research Companion to Popular Music Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).