Abstract

Transition-age youth exiting foster care (TAY) are at high risk for housing instability, with nearly half experiencing homelessness before age 26. Multi-level factors are associated with greater risk, including individual, social, and geographic contexts. This study explored experiences of TAY in a large region of Texas to identify drivers of housing stability during the transition out of care. Youth aged 18–25 who were connected to the region’s foster care transition center were recruited to participate in a mixed-methods, semi-structured interview (n = 25). Youth were prompted to identify networks of up to 20 people who had provided support over the past year. Interview questions explored what happened when youth turned 18, including changes in their housing situations, and delved into relationships with the network members. An iterative coding process was used to create a matrix to examine housing transitions and social supports within and across cases, then identify themes and subthemes. Housing instability was common, with 13 of 25 participants reporting episodes of homelessness after turning 18. Abrupt transitions were driven by systemic factors related to placement settings, strict rules, and a lack of available housing options. Social network data illuminated the close link between housing and the social network, along with the importance of “housing-capable” adults who helped prevent homelessness. Findings call for the development of more youth-friendly housing options for TAY transitioning out of care and interventions that help to build enduring social supports.

1. Introduction

Each year, over 15,000 youth emancipate from the foster care system or “age out” to independence [1]. Studies consistently show that these youth are at high risk for experiencing homelessness as they transition out of care, with 31–46% experiencing an episode of homelessness by age 26 [2,3,4]. In addition, studies focused on the overall population of youth experiencing homelessness (YEH) have consistently found that foster youth are overrepresented among YEH, with approximately 38% having been in the foster care system [5,6]. There is a clear opportunity for the foster care system to intervene to prevent these episodes of homelessness; however, despite broad recognition of the problem, interventions to date have not prevented many youth exiting care from experiencing homelessness and housing instability.

Prior longitudinal research has identified multi-level factors associated with greater risk for housing instability in youth aging out of foster care, with some relatively consistent findings. In the longitudinal Midwest study of youth aging out of foster care in three states, Dworsky and colleagues [2] found that a history of mental health challenges, being male, and experiencing physical abuse were individual-level predictors of later homelessness. In addition, running away from placement and placement instability prior to leaving care were associated with homeless episodes after exiting care [2]. Shah et al. [7] also found that placement instability while in care, particularly in congregate care settings, was associated with homelessness in their sample using administrative data from over 1000 youth exiting foster care in Washington State. At the individual level, they found that Black youth had nearly twice the odds of experiencing homelessness and, consistent with Dworsky et al.’s findings, those with histories of mental health treatment were also at higher risk. Using data from the longitudinal National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD) combined with additional state-level data sources, Prince et al. [8] also found higher odds of homelessness for Black youth and those with histories of running away as well as histories of behavior problems and legal system involvement. These findings suggest some characteristics that might help systems identify youth who are at risk for homelessness and could be targeted for support as they exit care.

One potential target for intervention that has been consistently associated with reduced risk for homelessness is more robust social support and family connections. Some data in the Midwest study pointed to the potential impact of social support from parents and grandparents as protective factors against homelessness [2]. Shah et al. [7] found that having been placed with a relative during foster care was also protective against homelessness after aging out, pointing to the potential impact of stronger family connections. Further, Prince et al. [8] found that being connected to an adult at age 17 reduced the odds of experiencing homelessness at age 19. Recent findings from the longitudinal California Youth Transitions to Adulthood study (CalYOUTH) found that having supportive people who remained in the youth’s lives over time were particularly important [9]. They found that youth who identified an enduring support, a person who was present at both age 17 and 21, were significantly less likely to experience an episode of homelessness, and, overall, to have experienced fewer homeless episodes and fewer days homeless. These enduring relationships were largely with family and friends, highlighting the importance of enhancing these types of permanent connections as a route to preventing homelessness. These studies have been limited, however, in their measures of social support, which have not examined the youth’s entire social network or identified the types of support various people in the network provide to help identify how these individuals might prevent homelessness.

At the state level, policy intervention to extend the age of transition out of foster care, known as extended foster care (EFC), has generally been found to reduce homelessness among youth exiting care. The Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008 incentivized states to adopt EFC by providing federal Title IV-E reimbursement for the continued care of eligible youth beyond age 18, in recognition of their developmental needs and the importance of continued support during this critical life stage [8,10,11]. Most U.S. states now allow youth to remain in or re-enter care after age 18, and youth are typically eligible to remain in care until age 21 if they meet certain conditions, such as attending school, working, or participating in a program designed to address barriers to employment. A growing body of research links EFC participation with improved housing stability. Using NYTD data, national census, and homelessness data, Spindle-Jackson et al. [12] found that youth homelessness in a state was eventually reduced by 23%, four years after the implementation of an EFC policy. NYTD data also show that homelessness becomes increasingly common as youth age out of care, and most who report experiencing homelessness are no longer in care at the time. Kelly [11] found that youth who remained in care until age 21 were about 42% less likely to experience homelessness than those who exited earlier. Additionally, in the CalYOUTH study of youth transitioning out of care in California, youth who spent more time in extended care had a lower risk of homelessness at age 21 [10].

Despite these promising outcomes, EFC remains substantially underutilized. In 2021, only about 22% of youth in care on their 18th birthday remained in care a year later [13]. Goodkind et al. [14] specifically sought to understand youth’s decisions to leave care through interviews and focus groups with 45 youth exiting care in one county in Pennsylvania. They found that youth chose to leave due to misunderstandings and misinformation about policies and procedures related to exiting care, combined with a desire for autonomy and independence. In contrast, in data from the CalYOUTH study, at age 17, youth reported high overall knowledge about the extended care program, and two-thirds reported they wanted to remain in extended care. They indicated that the top reasons for deciding to remain in care were their desire to further their education and receive material resources and housing [15]. This data highlights the importance of understanding the immediate context that may influence youth’s decisions to extend or not extend care and the associated impacts on housing stability.

The current study builds on this empirical evidence and draws on Brofenbrenner’s socio-ecological framework in conceptualizing housing instability for youth exiting foster care as the result of a multi-level developmental process [16]. We also draw on insights from social network theory [17] in highlighting the important role of the social environment and the structure and interconnections among support members as critical to understanding housing at this key point of transition. Given the empirical evidence that has identified the importance of the state and community context, social support, and individual risk factors, it is clear that there are intersecting factors at multiple levels that contribute to housing transitions and homelessness.

The current study aimed to elucidate the circumstances at multiple levels that lead to homelessness, with particular attention to social network structure and interconnections that facilitated or prevented housing stability. We sought to address several existing gaps in the literature. Prior studies have identified factors that contribute to housing instability, but have not examined how these factors work together to produce housing stability or instability. Given the important point of transition at age 18 when foster youth are often making the decision to extend or not extend care, we wanted to better understand specific situations that either fostered housing stability or contributed to housing instability at this specific time. And, while prior studies have clearly pointed to the importance of the social network for housing stability, they have generally included relatively limited measures of the social network and thus have had a limited ability to describe the wide array of people within the network, how they are connected to each other, and how the network specifically helped to protect against housing instability. In order to fill these gaps and better understand how housing instability happens for foster youth in young adulthood, we gathered in-depth, mixed-methods data from youth aging out of foster care in one region of Texas to answer the following research questions:

- (1)

- For youth who experienced homelessness, what were the drivers of the housing instability?

- (2)

- For youth who did not experience homelessness, what enabled them to remain housed throughout?

- (3)

- What was the role of extended care?

- (4)

- What was the role of the social network?

Together, these questions address the overall aim of the study to provide context to understand how factors previously identified in large quantitative studies produced housing stability or instability for young adults in the transition out of foster care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods

The study utilized a mixed-methods design with a primarily qualitative focus (QUAL + Quan), gathering both qualitative and quantitative data simultaneously to assist in understanding housing transitions and the youth’s social network. The study utilized mixed methods to enhance and broaden understanding through complementarity [18], collecting data that together provided a deeper understanding of youth housing transitions and the social networks that shaped these transitions. Participants were recruited through the designated agency responsible for administering services available for young adults who age out of the foster care system in one region of Texas. We sent flyers through email that were distributed by staff at the transition center. We aimed to understand a range of experiences with social networks for youth aging out of foster care, so we purposively recruited for a sample size within recommended targets for grounded theory approaches, capturing diverse experiences (n = 25) [18]. Young adults were eligible to participate if they were between ages 18–25 and had been in foster care when they turned 18. Research interviews were administered by a trained interviewer and conducted via secure videoconferencing due to the restrictions imposed by the COVID pandemic. We started with a structured interview followed by a qualitative semi-structured interview. Quantitative data, including detailed information about the social network, were entered into the social network data collection software, EgoWeb 2.0 [19], using tablets. Qualitative interviews were recorded and transcribed with identifying information removed. Participants were compensated with a USD 65 electronic gift card for an online retailer. All study procedures were approved by the university’s human subjects review board. Participants gave consent for quotes from their interviews to be used in publications, and pseudonyms are used to identify them.

2.2. Measures

The structured interview included self-report demographic questions and social network questions. Participants reported their age and race/ethnicity. They were asked to report their gender identity and then their sexual orientation with the question “which of the following best represents how you think about yourself?” with response categories of gay or lesbian, straight/not gay, bisexual, something else, or I don’t know/questioning. Participants were asked whether they had ever been homeless, and if they responded ‘yes’, they answered whether it had been in the past year. Those who had a history of homelessness but not in the past year were recoded as ‘homeless since turning 18’ based on information from their qualitative interview. Participants also reported whether they were currently still in foster care, the number of placements/homes they had been in while in care, and the number of years spent in care.

To assess their social network, respondents were asked to name people in their social network using an exchange approach [20]. We asked the following question which was adapted from a prior study with foster youth [21]: “I would like you to name up to 20 people in your life who provide you some type of support, including material support (like money or personal items), emotional support (such as comfort or caring), informational support (like sharing knowledge with you) or mental health support (like helping you with your mood or behaviors). These should be people from whom you have received some type of support in the past year.” Prompts were used to encourage participants to holistically include their entire network, such as, “Is this everybody? Remember, you can name friends, significant others like a boyfriend or girlfriend, family members, people you know through work or school, or just anyone that you’ve interacted with who has given you any type of support (nail tech, barber, restaurant server, etc.).” For youth who named fewer than five network members, we added additional prompts mentioning specific network members they might name and the reminder, “It can be anyone who has given you support, like a case worker, a librarian, a doctor/nurse or a bus driver. You do not need to know their name to include them.” Once all network members were named, we asked how well each network member knew each of the other listed members (not at all, somewhat, or well). The participants also provided information about the race and gender of the network members and their relationship to the network members. This approach enabled more extensive analysis of social networks than in prior studies, allowing for visual depictions of the networks to understand how connected network members were to each other as well as to identify key members of the network who were central and bridged different groups within it.

The qualitative interview then aimed to better understand the transition at age 18 and gather more information about the role of the social network. The interview guide began by asking the participant, “Tell me about where you were staying right before you turned 18.” Then followed up with “Did anything change for you when you turned 18?” and “What has happened in your life since you turned 18 to where you are now?” Then, the interviewer asked specifically about the people named in the social network and the types of support they provided, “You mentioned [xx] people who provide you different types of support. I’d like to learn more about those people. Tell me about how you formed relationships with them…” Prompts explored specific relationships and how support was delivered and received.

2.3. Data Analysis

We used a team-based consensus coding process that drew on grounded theory and employed case summaries and data matrix displays to facilitate identification of patterns and connections across cases [18]. We first divided cases into three categories to guide our analysis of the drivers of housing instability—those who had experienced homelessness in the past year, those who had experienced homelessness but not in the past year, and those who had never experienced homelessness. For each case, we reviewed case summaries and mixed-methods data, including quantitative data on foster care history and social networks, combined with qualitative transcripts and coding. Each person’s social network was displayed as a visual network map that illustrated the types of people represented (family, friends, intimate partners, professionals) and their relationship to each other. The team of three coders first met and reviewed all sources of data from one case from each of the three housing categories, discussing the findings that emerged and identifying key data that should be extracted to create our matrix display. We then created a matrix template [22], which we applied to six subsequent cases and met again to discuss our findings and the effectiveness of our tool. We then assigned cases and abstracted data for another group of cases, assigning some cases that overlapped to ensure consensus across coders (n = 7). There was a high level of agreement on the substance of the content extracted; however, we refined the level of detail that was desirable for extraction across cases, including the inclusion of more direct quotes within the matrix. At the culmination of this process, we assigned all remaining nine cases and the initial three cases that were used to develop the matrix to one coder to abstract into the final matrix. An example of the matrix categories is presented in Table 1. To generate our final results, each of the three coders reviewed the completed matrix and reflected on the key themes that emerged prior to a series of discussion meetings. We all took notes individually and developed candidate themes, staying close to the data and using the language from youth interviews to capture their meaning when possible. We had a high level of consensus as a team on the important findings and were able to finalize key themes that emerged over the course of two meetings. We specifically engaged in the team-based consensus process and kept an audit trail with team notes and individual reflections in order to enhance the rigor of our analysis [18]. To enhance the reflexivity of our process, we completed reflections about our prior personal and professional experiences that might shape how we read and interpreted the data prior to the start of the analysis process, in addition to checking in on our reactions as coders throughout the process [23].

Table 1.

Coding matrix categories.

3. Results

The sample demographics are presented in Table 2. Participants were racially diverse and disproportionately female. Over half of the sample (52%) had been homeless since exiting foster care. The average age was 19.4, and 40% were still in extended foster care.

Table 2.

Sample demographics.

Participants generally described multiple housing transitions after turning 18, regardless of whether they chose to remain in extended care or formally exit the foster care system. Our analysis identified some of the drivers of housing changes across cases, as well as what supported stability for those who reported no homelessness experiences.

3.1. Transitions at Age 18

Almost all cases reporting experiences of homelessness described turning 18 as a point of abrupt transition. Participants described both institutional and developmental changes that occurred at age 18, often in conjunction with their 18th birthday. The placement setting appeared to be a major contributor to housing instability at this point. Participants who turned 18 while in a residential treatment center (RTC) appeared to have particularly abrupt transitions, where they needed to leave immediately on their 18th birthday rather than in conjunction with the end of a school year or other sort of more natural transition point. For example, Jade, a 20-year-old, biracial young woman, described needing to leave the residential facility where she had spent the last several years on the day she turned 18: “they had kicked me out because I was 18 already so I had to go to a placement in [nearby city].” She spent several weeks in this foster home before moving to a supported independent living facility (SIL). Another 18-year-old biracial man, Will, described what happened when he turned 18: “I was put in a shelter because they didn’t have a place to put me just yet. And then the stay was ended because they have like a time to hold and then I went to a hotel, which I stayed for about two weeks, and then I got accepted here, a transitional facility.”

Conversely, participants who experienced housing stability were generally in well-established foster care placements that were committed to providing continued support. For example, Myra, a 20-year-old Latina woman, described what happened to her: “I was living with my foster parents, they allowed me to extend my care there after I turned 18…. nothing changed.”

3.2. Life Hit Me: Sudden Freedom and Sudden Responsibility

Along with abrupt transitions in housing, there were abrupt transitions in the level of independence and responsibility, which had implications for housing. Several participants noted that they immediately experienced increased autonomy when they turned 18, both in how they viewed their situations and how they were treated by the system. A 19-year-old Black man, Cedrick, who had recently become a father and gotten an apartment on his own, described his mindset at 18 as, “when I turned 18, I’m a grown man now, so I can’t act like a little kid. I gotta… I’m a grown man, it’s time to step up. That’s how I feel.” Will, who transitioned from an RTC to a SIL, described the sudden change when he turned 18 in relation to the increased control in his life: “my medical stuff was in my hands, my daily routine is in my hands, anything that has to do with planning is in my hands…all my responsibility, all my responsibility was mine again.” This change was not always smooth. Another 19-year-old Black man, Gregory, who moved from a foster home to a SIL on his 18th birthday but then ended up in a shelter, described the change in responsibility: “Life hit me, like that’s really all I can say about that.”

The desire to be free from the system emerged as a factor in multiple descriptions of what happened when participants turned 18. This sentiment appeared to be particularly strong among young people who were exiting care from RTCs. One 18-year-old Black woman, Danisha, described her decision to leave care: “I was just so used to being in a placement, so used to being locked down, so used to rules and when I turned 18, I finally wanted that freedom. I just finally wanted... I had, I was so anxious, to just be able to go to sleep on my own time, not eat specific food, just be able just to have that freedom that’s been so long that I haven’t had since I’ve been in care.”

Another 19-year-old white man, Aaron, described living in an RTC: “It absolutely sucks, you feel trapped, you feel like you have no control over your life.” At age 18, he chose to remain in extended care but was immediately moved from an RTC to a more independent living facility, where he was kicked out and became homeless. He explained that “They gave me a little bit of freedom and I took it too far.” He ended up in another SIL placement and was savoring increased independence: “There’s not no one here to like basically tell me what to do. I can do whatever I need to do to get done. I get things done a lot faster. I can finally do my own laundry. I got my own like space. I’m allowed to go outside whenever I need to. I can take a walk whenever I want to. I can get a job. I can go to the store. I can basically do anything that a normal person can do with freedom and not having to worry about getting in trouble for it.”

3.3. Everything Sounds Great on Paper: Fragile Plans and Systemic Failures

Throughout descriptions of their transitions at age 18, participants described disappointments and failures on the part of the system that they believed would support them in the years after age 18. While a planning process was in place that was supposed to facilitate successful transitions, including housing stability, several participants described plans that seemed inherently fragile and disintegrated rapidly once they left care. Danisha, who described wanting to have increased freedom, also thought she would continue to have some support through aftercare services: “I had been told by several people while I was in care that whenever you age out… you’re going to have people even though you’re not in care…I found that not to be true… I get so little help while I’ve been out of care.”

Another 18-year-old biracial woman, Ashley, described the planning process when she left care: “Everything sounds great on paper, you know, everybody’s going to support you. Everybody’s there for you. And then, nobody’s there. So, kind of just they do what they have to do to file the papers that they need to. So their bosses don’t bother them.” She made the decision to exit care to a kinship placement, which fell apart one month later, and she scrambled to find temporary housing with her sister without any support from the foster care professionals.

Sometimes fragile placements appeared to be related to a lack of options for housing. A 23-year-old Black woman, Sara, described what happened when she turned 18: “I was basically causing trouble, too much trouble in the household, so the foster parent kicked me out. I had to go stay with someone. My dad had this lady that he was talking to-she was like a stepmom-but that was a nightmare. But that’s who I went to go stay with, and that was terrible.” She went on to describe eventually being kicked out and staying at a homeless shelter.

Some youth described plans for returning to family at age 18 or leaving foster care due to their own desires. They perceived the point of turning 18 as an opportunity to exert their autonomy and decide for themselves where they wanted to live. The desire to be free from the system and the people who told them what to do was a powerful motivator. One 20-year-old biracial woman, Carin, described how her relationship with her case worker led her to exit care when she turned 18: “We’re just not on the same page. It was just chaotic between us. I was just trying to do what I felt was best for me, and she wanted to do what she thought was best for me, which is not your choice, but it’s my choice…She was still trying to make decisions for me, and it wasn’t her call. … then I was just like I don’t want to do this anymore.”

3.4. Staying Housed: Transition Planning and Supportive Adults

About one-third of participants reported a relatively smooth experience at the point of transition, where they were able to remain housed. We identified several drivers of more positive outcomes, including early transition planning, continued access to housing placements that were able to support them, and a consistent adult who either provided housing or assisted in housing navigation.

One 18-year-old Black woman, Andrea, who was able to transition from an RTC back to reunify with her family, described a planned transition process for returning home: “I started to do some home visits and then it started to, you know, transition into like staying the weekend…And I think it’s made us stronger as a family … that helped me transition home.”

Another 19-year-old Black woman (Selena) ’s story illustrates the intersection of having family support and a transition plan to ensure housing stability. She transitioned from a foster placement of three years to a stable kinship placement with her aunt a month before her 18th birthday. She described the long-term presence of her aunt: “I always knew that if I was to age out, I can always be with her. … She would always just say ‘you know if you need anything you can call me’ and …. finally, they said that I was approved to live with her.”

Several participants also described the important role of their intimate partners in providing a smooth transition. One 18-year-old Black woman, Brandi, who transitioned out of care from her grandmother’s house described, “my boyfriend has been supporting me. We got our apartment together and we moved in together, and we go half on rent and the bills and stuff. So, it’s more easier on us.”

Another 19-year-old Latina woman, Fedora, who transitioned from a foster placement where she had stayed for four years to live with her boyfriend and his family, described the process: “I’ve always explained it to her that once I turned 18 I’d be leaving foster care. It’s always been a plan of mine, so it wasn’t really a shocker. I just couldn’t be in the system any longer. It’s just I’ve already been in it for 15, 16 years. I was like I’m just through with it already. So we were planning for my 18th birthday…and it was just a breeze.”

Caseworkers also played an important role at times in helping participants navigate the system to stay stably housed. For example, Will, whose transition was described earlier from an RTC to a shelter and then hotels, did not perceive that he had experienced homelessness because his caseworker was overseeing his move from shelter to hotel to eventual placement in a SIL.

3.5. When You’re 18, You’re Not Guaranteed a Place: Support Through Extended Care

While we had anticipated that remaining in extended care would be protective against housing instability, participants often reported struggles to maintain housing, even when they chose to extend care. Young adults noted a distinct difference in the role of the system in providing housing once they turned 18. One 25-year-old Black man, Kingston, described this phenomenon: “Before you’re 18, it’s like they would find you a place to go. Even though it might not be the best place, you know, you’re guaranteed a place. When you’re 18, you’re not guaranteed a place… And then they not going to accept you because you’ve got this high level, this label that they put on you. So when you get 18, it’s really hard. Even when you’re in care because there’s no guaranteed placement for you.”

Another 19-year-old white woman, Megan, described this same change at age 18, “I mean you get a new found sense of independence but with that also comes… like you are expected from CPS if they don’t have somewhere to go once you turn 18 you’re just put to the curb.”

In addition to being more limited and not guaranteed, the primary placement options for youth in extended care, SILs, were described as sometimes having strict rules and the ability to kick youth out who did not follow those rules. Several young people described periods of homelessness after being kicked out of a SIL, even though they were still in extended care. For example, one 20-year-old biracial woman, Nyali, described her experience: “I had broke one of the rules here and when you break a rule they give you the chance to have three months’ probation to where you can come back in three months, so I was temporarily in trial of independence for three months.” She described spending those three months at a homeless shelter and staying temporarily with a boyfriend until she returned to the SIL and was able to be successful.

Extended care appeared to work best when housing was already relatively secure. For example, a 19-year-old Black man, Jerome, noted that at the time of turning 18, he was staying at “a foster home with my people, they’re good people” where he had lived since age 14. He described his transition to a SIL as the result of his own desire for independence “They told me I can stay but I kind of want to be on my own.” He had graduated from high school and was working for Amazon with aspirations to get his own apartment.

3.6. Returning to Stable Housing

Most participants were able to secure housing following periods of homelessness. The route to returning to housing stability often relied on reconnection with housing programs that they had access to due to their connection to the foster care system. Some participants left care, then returned and moved into a SIL. Others benefitted from a program run by the local transition center, which provided housing support in which participants rented independent apartments in a central location. A few others talked about housing vouchers they were able to secure through the housing authority because they had been in the foster care system, which provided housing support for them to rent their own apartments. All of these situations were possible due to connections with aftercare caseworkers, often paired with persistent self-advocacy.

We identified a pattern of what we termed “housing-capable” adults who were able to either directly provide stable housing themselves or were able to broker connections to assist young people in finding a stable housing situation. For example, Aaron’s return to housing was facilitated by a professional in his network whom he was able to call for support: “Mr. X, my PAL [Preparation for Adult Living] worker, he got me a hotel and then got me into this place…. I was sitting on the street in the cold, it was that one point when it was stormy and stuff and it was snowing and everything, but he picked me up and then he got me a hotel.”

3.7. Social Networks: Influence and Are Influenced by Housing

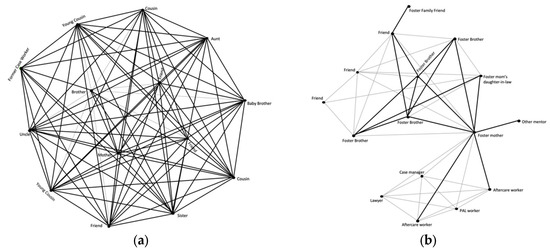

As we examined the social networks in conjunction with our themes and housing status data, we identified a few key aspects of the social network related to housing. As we had identified based on the qualitative data, the role of the social network was key to fostering housing stability. In general, those who reported housing stability had larger, more tightly connected networks that included “housing-capable” adults who could support them in securing and maintaining housing, whereas those who had experienced homelessness had fewer adults and more fragmented networks. In addition, we noted the reciprocal relationship between the housing setting and the network, where people who were physically in the same housing location, such as a housing manager or peers who lived in the same facility, were often listed in the network. To illustrate the key findings, we present some example case studies, including network visualizations and the associated case characteristics for two cases that experienced housing stability during the transition out of care and two cases that had housing instability.

3.8. More Stable Housing: Selena and Felix

Selena, who was mentioned above, is a 19-year-old Black female who lives with her aunt and uncle. During her eight years in foster care, she had three foster care placements. She exited care to live with her aunt and uncle, who were also providing housing for her older sister. Her network includes fourteen people who are very interconnected (Figure 1a). In addition to her aunt and uncle, she reported a very close relationship with her mother and her siblings, and she also included a former caseworker and several friends in the network. She described what she appreciated about her former caseworker, who she feels she can still reach out to for support, “She was another one that always make sure my voice got heard like anytime… She was like always supportive.” Most network members have ties with each other; some live in the same house with her, and Selena is in frequent contact with many of them. She described the importance of the long-term relationship she has had with her aunt, who had tried to gain custody while she was in care and had maintained contact: “another reason why I felt like I’m so close with her, she never gave up for me....even when she knew she couldn’t [gain custody] she still tried.” She talks about moving into the transition center apartment program in the future or trying to secure a voucher on her own, but notes that her aunt’s house is always an option: “I know that she there, I know that anytime that I need somewhere to live, I could come be with her.” This type of situation illustrates the role of housing-capable adults who provide an unconditional place where a young person can find housing.

Figure 1.

Network maps of stably housed youth: (a) Network map with 14 members (Selena). (b) Network map with 16 members (Felix).

Felix is a 19-year-old Latino man who lives in a foster home where he had been for the past three years. He had two foster care placements during his four years in care. He identified 16 people in his network, most of whom were connected to the foster care system–4 foster brothers, his foster mother, her daughter-in-law, a close family friend, and four aftercare support workers (Figure 1b). He also named several friends and a lawyer who had helped him with a legal case. When he turned 18, he remained in extended care in the same foster home in order to finish high school. He noted that not much changed when he turned 18, “the only thing that really change was I was allowed to stay out longer.” He identified his foster mom as a critical key support in his life, and this was reflected in the network map, where she is the connector for the network. He noted that if he was having a problem: “I would just go to my foster mom and be like hey this is going on, I need help and then she’ll take it from there, you know she’ll be the one to take over and she’ll give me the help I need.” When asked about any connections to family outside the foster care, he stated, “I’m a foster kid so family is something I don’t like, you know, I don’t really talk to my family, so the only really family that I would say, is my foster family.” While the network contained primarily individuals that he had met through foster care, it appeared that he had built long-term connections that would remain in his life after he left the foster home. He described plans to go to college and clearly saw his foster family remaining in his life.

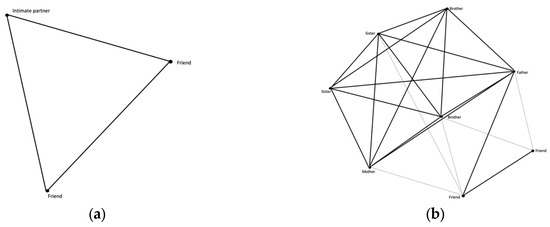

3.9. Periods of Housing Instability: Angel and Denise

Angel is a 19-year-old biracial female who had six placements during her two years in the foster care system. Her network contained only three people–two friends and her girlfriend (intimate partner; Figure 2a). She had met one of these friends and her girlfriend through a shelter and the other through a period of time she spent at Job Corps. When asked about family, she noted, “Um I don’t really talk to my people.” Overall, she noted that her network is small because, “I stay to myself, I don’t like people like that. Yeah so I stay to myself.” She described choosing to extend care at 18 and then moving from an RTC where she had been for a year to a SIL placement. She stated that she was there for “a couple months and then they kicked me out.” And she was “homeless, on the streets.” She remained in extended care technically during the next year, but noted, “they haven’t even talked to me, since I left.” She eventually found housing after a shelter stay and was able to use her foster care history to obtain a housing voucher. While she had some connection to the transition center, she described how she got the voucher, “I did it on my own.” Her network was notable for the absence of people who were able to help with housing, and a period in extended care had not provided any adult connections that helped her when her initial placement fell apart.

Figure 2.

Network maps of unstably housed youth: (a) Network map with 3 members (Angel). (b) Network map with 8 members (Denise).

Denise is a 20-year-old White woman who is currently residing in a transitional living program. She had 10 different placements during her eight years in foster care. When she turned 18, she left the foster home she had been staying at for the prior two years and moved in with her mother to try and reconnect. “I needed to figure out the truth, so I wanted to go with my mom. And, then I found out the truth.” She had chosen to extend care because, as she noted, “I didn’t know how it was going to go.” The situation with her mother did not work out, and she ended up homeless and bounced from staying with a boyfriend and his family to a lady across the street until she was able to reconnect with an old foster family that helped her find housing. Her network included eight people, six of them family members, including her former foster parents, whom she considers family, and two friends (Figure 2b). Notably, no professionals connected to the foster care system are in the network. Connections with family were recent reconnections, and Denise was hopeful that these would translate into long-term support.

4. Discussion

This study contributes new evidence on how foster care history, extended care, and social networks intersect to shape housing stability among transition-age youth, extending prior research by centering the lived experiences of young people in Texas and drawing on in-depth data from 25 participants in one region of the state. Findings provide insight into some of the specific factors that might be targeted in future interventions to improve housing stability as youth turn 18 within this context. Findings highlight the changing support that young adults received when they turned 18, whether they chose to remain in extended care or formally exit the system. Participants both appreciated the increased autonomy while also noting the abrupt transition to increased responsibility. Several key findings emerged that highlight potential avenues for enhancing supports, particularly for improving housing options and building social supports.

Notably, participants talked about the immediate change they experienced in what the system was able or willing to do to provide them with housing when they turned 18. And, this impacted the attractiveness of staying in care based on what the system could offer. For participants who were ready to move past the restrictiveness they had experienced in the foster care system, staying in care did not offer advantages if it was not able to provide tangible benefits such as housing. This situation may be context-dependent and vary from state to state. Courtney et al. [24] found positive outcomes related to SILs in California with reduced odds for homelessness among those who extended care and those who lived in transitional supportive housing. But California notably invests more into foster care than many other states [24]. In their analysis of data across states, Prince and colleagues [8] found that youth who were living in states that spent above average on housing for room and board for foster youth were less likely to experience homelessness than those living in states where spending was below average. It is likely that the experiences of the participants in our study illuminate the dynamics that lead to this difference. Texas has notably struggled to provide an adequate supply of housing for foster youth, and low reimbursement rates for providing independent living have made this a scarce and difficult-to-access resource [25]. In this environment of limited resources, youth who were more difficult to house ended up experiencing homelessness.

Multiple participants described being kicked out of supervised independent living programs due to rule violations. This highlights a problem that is embedded in the Fostering Connections legislation that contains conditions on what youth must do in order to receive support (working, being in school, etc.). With limited housing options, only the youth who are most functional may end up being successful in these settings, leaving a highly vulnerable group without housing options. Among young adults broadly, it is increasingly common that young adults end up returning home and relying on financial support from parents, in many cases with fewer conditions than foster youth experience [26]. Our findings highlight the need for a greater range of housing options that are available to meet the developmental needs of these youth, without rigid rules and conditions. This recommendation is in line with findings of a meta-synthesis of programs focused on interventions to address youth homelessness [27]. They found that the most important factors for successful implementation of programs for youth experiencing homelessness, a population with substantial overlap with youth aging out of foster care, are organizational factors and staff training. Specifically, they recommend that programs eliminate zero-tolerance policies and consider low-barrier approaches [27]. Several youth talked about publicly funded Housing Choice Vouchers (Section 8) that eventually provided a route to housing [28]. The Foster Youth to Independence voucher program, which was expanded in October 2020, provides housing vouchers specifically to young people under age 25 who have been in foster care and is in line with the type of less restrictive housing options that might support a wider range of young people than the more structured independent living programs [29].

The participants in our study also seemed to need additional information and support in making the decision to extend or not extend care. Research that examined variation in youth deciding to stay or exit care in Illinois identified the important role of court procedures in supporting youth decisions to stay in care [30]. It should be noted, however, that while education and support for youth in making informed decisions to stay in care may increase participation in extended care, without housing options, staying in care is inherently less attractive.

While housing access is clearly important, our research also supports the fact that having individuals in the social network who could assist with housing was key. Network enhancement strategies that can identify key supporters and bolster the ability of these key supporters to actually provide information and resources that facilitate housing could assist in preventing initial homelessness or helping youth reconnect with housing if an initial plan fails. Natural supports such as family and friends or other non-professional supportive adults are likely best positioned to provide this support for the long term, beyond involvement in the foster care system [9,31]. Housing-capable adults were key facilitators of housing stability in our study, highlighting that the quality of support within the network was an important target for intervention rather than merely increasing the number of network members. Housing-capable adults were characterized by both their sustained presence in the networks of our participants and their willingness and ability to provide housing support. Multi-pronged strategies that assist young adults to identify potential housing-capable adults, combined with cultivation of the capacity of these adults to provide the needed supports, could help youth navigate the transition without experiencing homelessness.

This study should be interpreted considering several limitations. First, the data were cross-sectional, capturing a snapshot of participants’ housing experiences that relied on retrospective recall rather than longitudinal prospective data. As a result, we cannot fully assess the durability of housing stability or instability over time. Second, the study was conducted in a single metropolitan region of Texas, which limits generalizability to other geographic contexts with different foster care policies, housing markets, or service landscapes. Third, the sample size was relatively small and does not fully capture the diversity of experiences among transition-age youth exiting care. Fourth, reliance on self-report introduces the possibility of recall bias or underreporting of sensitive experiences, such as homelessness, and may not accurately report child welfare experiences, such as the number of placements or years in care. Finally, our matrix analysis approach resulted in data reduction, and hence, there is a chance that we overlooked more nuanced dimensions of participant experiences. We attempted to guard against this, however, through our team-based inductive process. Despite these limitations, the mixed-methods approach, integration of social network mapping, and rich qualitative data provide valuable insights that advance understanding of the drivers of housing stability and instability among youth aging out of foster care.

5. Conclusions

Youth transitioning out of foster care face significant risks of housing instability, yet their pathways are shaped by an interplay of policy contexts, placement settings, and social networks. Our findings underscore the limitations of extended foster care when housing options are scarce or overly conditional, highlighting the need for flexible, youth-centered approaches. At the same time, enduring relationships with “housing-capable” adults, whether family members, kin, or former foster parents, emerged as a critical protective factor. Interventions that expand the supply of youth-friendly housing, adopt low-barrier policies, and intentionally strengthen the ability of housing-capable adults to provide housing support may reduce the likelihood of homelessness and improve outcomes as youth move into adulthood. Future research should continue to examine how social networks and housing systems intersect over time to promote stability and resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, and funding acquisition, S.C.N.; formal analysis, data curation, writing—review and editing, and visualization, C.M.; formal analysis, writing—review and editing, J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the University of Houston, High Priority Area Research Seed Grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Houston (STUDY00002359, approved 7 September 2020).”

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- US Administration for Children and Families. Exit Reason Dashboard, AFCARS Data Viewer. Tableau Public. Available online: https://acf.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/afcars (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Dworsky, A.; Napolitano, L.; Courtney, M. Homelessness during the Transition from Foster Care to Adulthood. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, S318–S323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.J.; Toro, P.A.; Miles, B.W. Pathways to and From Homelessness and Associated Psychosocial Outcomes Among Adolescents Leaving the Foster Care System. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 1453–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect (NDACAN). National Youth in Transition Data (NYTD) Brief #7; NDACAN: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, K.; Yang, J.; Ferguson, K.; Thompson, S. Experiences and Needs of Homeless Youth with a History of Foster Care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 55, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narendorf, S.C.; Brydon, D.M.; Santa Maria, D.; Bender, K.; Ferguson, K.M.; Hsu, H.-T.; Barman-Adhikari, A.; Shelton, J.; Petering, R. System involvement among young adults experiencing homelessness: Characteristics of four system-involved subgroups and relationship to risk outcomes. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 108, 104609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.F.; Liu, Q.; Eddy, J.M.; Barkan, S.; Marshall, D.; Mancuso, D.; Lucenko, B.; Huber, A. Predicting homelessness among emerging adults aging out of foster care. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2017, 60, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, D.M.; Vidal, S.; Okpych, N.; Connell, C.M. Effects of individual risk and state housing factors on adverse outcomes in a national sample of youth transitioning out of foster care. J. Adolesc. 2019, 74, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okpych, N.J.; Park, S.; Powers, J.; Harty, J.S.; Courtney, M.E. Relationships that persist and protect: The role of enduring relationships on early-adult outcomes among youth transitioning out of foster care. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2023, 97, 619–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, M.E.; Okpych, N.J.; Park, S. Report from CalYOUTH: Findings on the Relationship between Extended Foster Care and Youth’s Outcomes at Age 21; Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, P. Risk and protective factors contributing to homelessness among foster care youth: An analysis of the National Youth in Transition Database. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 108, 104589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindle-Jackson, A.; Byrne, T.; Collins, M.E. Extended foster care and homelessness: Assessing the impact of the Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act on rates of homelessness among youth. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2024, 164, 107820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Annie E. Casey Foundation. Fostering Youth: Executive Summary; The Annie E. Casey Foundation: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2023; Available online: https://assets.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/aecf-fosteringyouth-executivesummary-2023.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Goodkind, S.; Schelbe, L.A.; Shook, J.J. Why youth leave care: Understandings of adulthood and transition successes and challenges among youth aging out of child welfare. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, L.; Sulimani-Aidan, Y.; Courtney, M.E. Extended Foster Care in California: Youth and Caseworker Perspectives; CalYOUTH: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Dev. Psychol. 1986, 22, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Mehra, A.; Brass, D.J.; Labianca, G. Network Analysis in the Social Sciences. Sci. (Am. Assoc. Adv. Sci.) 2009, 323, 892–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padgett, D. Qualitative Methods in Social Work Research, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- EgoWeb 2.0, Computer Software. Qualintitative. Available online: http://egoweb.info (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- McCarty, C.; Lubbers, M.J.; Vacca, R.; Molina, J.L. Conducting Personal Network Research: A Practical Guide; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, R. Social networks of youth transitioning from foster care to adulthood. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 107, 104520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.L.; Adkins, D.; Chauvin, S. A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, 7120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtney, M.E.; Park, S.; Harty, J.S. Foster Care Policy and Homelessness among Youth Transitioning to Adulthood from Foster Care. Child. Abus. Negl. 2025, 169, 107638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narendorf, S.C.; Gendron, C.; Minott, K.; Barillas, K.; Santa Maria, D. Youth Homelessness in Texas: A Report to Fulfill the Requirements of HB 679; Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs: Austin, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A.R. FP-21-23 Young Adults in the Parental Home, 2007–2021; Bowling Green State University: Bowling Green, OH, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, S.R.; Baiocchi, A.; Tully, B.A.; Garst, N.; Bielz, S.; Kugley, S.; Morton, M.H. Improving program implementation and client engagement in interventions addressing youth homelessness: A meta-synthesis. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Section 8 Housing. Available online: https://www.usa.gov/housing-voucher-section-8 (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Pergamit, M.; Prendergast, S.; Coffey, A.; Gedo, S.; Ali, Z. An Examination of the Family Unification Program for Youth; Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, C.M. Examining regional variation in extending foster care beyond 18: Evidence from Illinois. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 1709–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munson, M.R.; Smalling, S.E.; Spencer, R.; Scott, L.D., Jr.; Tracy, E.M. A steady presence in the midst of change: Non-kin natural mentors in the lives of older youth exiting foster care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2010, 32, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).