Abstract

Available reviews of the literature have failed to adequately address research on non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) that has been conducted in developing countries, with the aim of this study being to systematically review empirical research on NSSI that has been conducted among adolescents and young adults living in countries located on the African continent. Guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for mixed methods systematic reviews, searches were conducted in six databases—PubMed, Scopus, PsychINFO, African Journals Online, African Index Medicus, and Sabinet African Journals—with searches being conducted from inception to 31 December 2024. These searches identified 33 unique records published in peer-reviewed journals or presented in postgraduate theses during the period 1985 to 2024; with the process of data synthesis identifying three broad analytic themes: the nature of NSSI, risk/protective factors associated with NSSI engagement, and the functions of NSSI. Key findings in relation to these themes: (1) highlight the value of an ethnomedical perspective in cross-cultural research on NSSI, and (2) suggest that the conventional focus on intrapersonal and proximal interpersonal influences on NSSI (in relation to both risk/resilience and NSSI functions) could usefully be extended to include influences emanating from the broader sociocultural context in which individuals are embedded. These findings are discussed in terms of their implications for future research.

1. Introduction

As early as the mid-19th century, a subcategory of intentional self-injury was reported in the clinical literature, with this subcategory being distinguished from suicidal self-injury in the sense that it involved deliberate self-harm to the surface of the body without the intent to die [1,2]. A variety of terms have been used to describe this behavioural syndrome—including self-mutilation, deliberate self-harm, parasuicide, self-inflicted violence, and cutting—with the term non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) being favoured in the contemporary literature.

1.1. The Nature and Scope of NSSI

Although a proposal for a distinctive NSSI diagnosis was made as early as 1984 [3], it was only 30 years later that NSSI was included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) in 2013 [4], and retained in the more recent text revised edition of the DSM (DSM-5-TR) in 2022 [5], with proposed DSM criteria for NSSI including the following: (a) intentional damage to the surface of the body without the intent to die, (b) a frequency of at least five times in the past 12 months, and (c) forms of self-injury that are not culturally or socially sanctioned. While these criteria have been found to be largely non-contentious there has been an ongoing debate regarding the minimum annual frequency requirement, with a number of studies suggesting that the discriminant validity of the diagnosis would be improved if the minimum annual frequency threshold were to be increased to at least 15 times [6], or even 25 times [7].

The inclusion of NSSI in the DSM has attracted the attention of the research community, with there being an emerging body of literature that has reported on prevalence rates, risk factors for, and the functions of NSSI. With regard to global estimates of the prevalence of NSSI among adolescents and young adults, findings from available meta-analyses suggest that NSSI prevalence rates vary from 18.0% to 42.0% (M = 22.8%) for lifetime NSSI [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] and from 18.6% to 23.2% (M = 20.9) for past-12-month NSSI [10,11,15,16].

Factors that that have been found to be associated with higher prevalence rates for NSSI include sex, with females reporting significantly higher rates than males in four analyses [9,10,15,16], with this trend being qualified by one analysis [12] which found that females are more likely than males to engage in NSSI behaviours in Europe and North America but not in Asia. Available meta-analyses also suggest that there are likely to be regional differences in NSSI prevalence rates. However, there has been little agreement on the nature of such variations, with one analysis suggesting that prevalence rates for NSSI are higher in Asian countries [9], another suggesting that prevalence rates are highest in Australia [11], and a third concluding that prevalence rates are similar across countries [13].

With respect to whether available analyses provide a truly global perspective on NSSI prevalence rates, it is important to point out that available understandings of global rates for NSSI have been derived largely from five continents (Asia, Australasia, Europe, North America and/or South America), with most available meta-analyses failing to include any studies that have examined prevalence rates for NSSI in Africa [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Although Quarshie and colleagues have conducted a systematic review of self-harming behaviours among adolescents and young adults in sub-Saharan Africa [17], their review only identified four journal articles that reported on the prevalence of NSSI among young people in sub-Saharan Africa [18,19,20,21], with all four of these studies having been conducted in South Africa.

1.2. Risk and Resilience for NSSI Engagement

Risk factors for NSSI can be considered at a number of ecosystemic levels in which adolescents and young adults are embedded. At an individual level, NSSI has been found to be more common among females [9,10,13,15,16,22] and among adolescents aged 10 to 19 years [8,14,22]. NSSI has also been found to be associated with various mental health problems—including depression, generalized anxiety disorders, symptoms of posttraumatic stress, and emotion dysregulation [23,24,25,26]—and has been found to constitute a risk factor for both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts [23,27]. A history of child maltreatment in the family home has also been found to constitute a risk factor for NSSI [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], with all conventional forms of child maltreatment (sexual, physical, emotional, and/or neglect) having been found to be associated with NSSI outcomes [30].

At an interpersonal level, NSSI has been found to be associated with a lack of social support from those in an adolescent’s/young adult’s proximal social environment (family, peers, and/or teachers) [39,40,41,42], with high levels of social support and connectedness having been found to be associated with lower levels of NSSI engagement [40,41].

In addition, there is an emerging body of evidence which suggests that risk factors for NSSI engagement may also reflect the influence of broader sociocultural influences, with such influences varying across different sociocultural settings [43]. Sociocultural risk factors for NSSI that have been identified in recent studies include cultural stigmatization [44], racial and ethnic discrimination [45], sex- or gender-bias discrimination [46,47], acculturation stress [48], and poor spiritual/religious identity or religious doubt [49,50]. Social censure and derision have also been found to constitute a risk factor for NSSI in situations where individuals perform culturally sanctioned behaviours in a manner that is not socially sanctioned. Thus, for example, among the Māori people in New Zealand, tattoos are social sanctioned as long as the tattoo has cultural significance. However, individuals who have tattoos that do not have cultural significance open themselves to social censure and public derision [44,51].

Factors that have been found to exert a salutary influence on NSSI engagement include (a) individual characteristics such as high scores on measures of personal resilience [41,52,53,54,55,56], high levels of affect regulation [54], and/or positive/active coping styles [40]; (b) high levels of social support from either family members [39,40,41,44,52] or from peers and significant others in the individual’s life [40,41,42]; and (c) spiritual/religious influences including low levels of religious doubt or questioning [50].

Taken together, these finding for NSSI risk and resilience suggest the need for a broader perspective on NSSI risk and resilience that encompasses all levels of the ecosystem in which individuals are embedded.

1.3. Motives for NSSI Engagement

Efforts to conceptualize the reasons why individuals engage in NSSI have been largely informed by the two-factor conceptual model developed by Nock and Prinstein [57]. The first of the factors in this model relates to intrapersonal efforts designed to minimize distressing emotional/cognitive states or to produce positive emotional/cognitive states, while the second factor relates to interpersonal efforts designed to modify or to regulate an individual’s social environment (e.g., gaining attention from others or escaping from interpersonal task demands). In a recent meta-analysis of research on the functions of NSSI [58], it was found that intrapersonal functions (particularly, functions relating to emotion regulation) were most common (66–81%), with interpersonal functions also being relatively common (33–56%).

However, comparisons of NSSI functions in Western and non-Western countries suggest that while intrapersonal NSSI functions are more common in Western countries [58], interpersonal functions tend to be more prominent in non-Western countries [59,60]. Further, given that risk factors for NSSI include a variety of sociocultural influences, it is likely that NSSI functions may also include efforts to moderate distress arising from socially mediated forms of stigma, alienation, and social exclusion. However, we were unable to identify any studies that have systematically attempted to explored this hypothesis.

1.4. Traditional African Conceptualizations of Disease and Distress

Traditional African conceptualizations of health and wellbeing tend to be holistic in nature, as they embrace not only the physical causes of disease but also interpersonal and sociocultural ‘causes’ of disease or distress [61]. Given that the 54 countries in Africa are characterised by markedly diverse cultural beliefs and practices (both between and within countries), perceptions, understandings of, and intervention strategies for disease or subjective distress (including NSSI) are likely to vary across different sociocultural contexts [43]. As such, a broad ethnomedical perspective would appear to be indicated in order to adequately capture the nature and dynamics of NSSI in the diverse African context [43,60,61,62].

1.5. This Review

Available reviews of the literature have failed to adequately address research on NSSI that has been conducted on the African continent, with the aim of this study being to systematically review empirical research on NSSI that has been conducted among adolescents and young adults living in countries located on the African continent. Although there has been one previous systematic review of research on self-harming behaviours in Africa [17], that review was restricted to studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, was published five years ago, and only identified four published studies that focused on NSSI among young people [18,19,20,21].

For purposes of this review, adolescents were defined as young people in the second decade of their lives (10 to 19 years) and young adults were defined as individuals aged 20 to 25 years [63]. In order to ensure that the definition of NSSI used in the study was broad enough to encompass emic perceptions of NSSI, a broad definition of NSSI was employed: “Deliberate self-harm to the surface of the body in the absence of suicidal intent”. While adequately capturing the core defining characteristics of DSM criteria for NSSI, it is broad enough to encompass culturally specific notions of NSSI. For example, it has been documented that an individual cutting their own hair may be regarded as a form of NSSI by some members of the Australian aboriginal community [44,51], with the definition of NSSI employed in this study being broad enough to accommodate such culturally specific understandings.

2. Methods

This review was guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for mixed methods systematic reviews [64]. In addition, efforts were made to ensure that findings from this review were reported in a manner that complied with the updated PRISMA 2020 checklist (registration number: CRD420251174876) for systematic reviews [65], with these efforts being summarised in Supplementary Data S3. Although a research protocol was developed for the study (see Supplementary Data S7), this protocol was not registered with PROSPERO prior to the commencement of data collection.

2.1. Research Question

The primary research question was as follows: “What is known about the nature, risk/protective factors for, and functions of NSSI among adolescents and young adults living on the African continent”? A more detailed breakdown of the key constructs in this question is presented in Table 1, with the structure of this breakdown being informed by the SPIDER Tool (Version 1) that can be used in the synthesis of qualitative, mixed methods, and quantitative data [66]. The process of operationalising key constructs was iterative in nature, with all team members meeting on a regular basis to adapt and refine operationalizations.

Table 1.

A breakdown of key constructs from the research question using the SPIDER Tool.

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria for this review were as follows: (a) original research studies that were published in peer-reviewed journals or presented in postgraduate theses/dissertations, (b) publication date being any date prior to 1 January 2025, (c) studies conducted on NSSI among adolescents aged 10 to 19 years and/or young adults aged 20 to 25 years (although studies that deviated by no more than two years either side of these age limits were included as long as such inclusion was not associated with significant changes in mean age scores), (d) studies that reported on self-harming behaviours that met this review’s definition of NSSI (i.e., deliberate self-harm to the surface of the body in the absence of suicidal intent), (e) studies conducted in African countries, (f) studies conducted in both African and non-African countries (as long as findings for African participants were reported separately), and (f) studies published in any language.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) articles/dissertations that did not report on original research (e.g., reviews of the extant literature, commentaries, and editorials), (b) articles not published in peer-reviewed journals or presented in postgraduate theses/dissertations, (c) articles that were published after 31 December 2024, (d) studies that reported on self-harming behaviours that did not meet this review’s definition of NSSI (i.e., deliberate self-harm to the surface of the body in the absence of suicidal intent), (e) studies that employed age ranges that deviated from the age ranges defined in the inclusion criteria, (f) studies not conducted in African countries, (g) studies conducted in both African and non-African countries, in which findings for African participants were not presented separately, and (h) types of NSSI that could be better accounted for by a psychotic disorder, an autistic spectrum disorder, or a cognitive developmental disorder.

2.3. Information Sources

Searches were conducted in six databases (PubMed, Scopus, PsychINFO, African Journals Online, African Index Medicus, and Sabinet African Journals), with searches being conducted from inception to 31 December 2024. The search strategy was informed by terms that emerged from the operationalisation of key constructs in the research question (Table 1), with the general form of searches being as follows: research participants (or equivalent) AND the names of each African country AND non-suicidal self-injury (or equivalent) AND research design (or equivalent) AND data analysis (or equivalent) AND research type (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed method), with the syntax employed in all database searches being presented in Supplementary Data S1. In line with inclusion/exclusion criteria for the study, we included qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies that reported original research in peer-reviewed journals or in postgraduate theses/dissertations on any date prior to 1 January 2025 and excluded conference proceedings/abstracts, reviews of the extant literature, editorials, and commentaries, with studies published in any language being considered for inclusion. Specific search terms used in database searches were formulated by members of the research team, with a specialist librarian being recruited to validate the appropriateness of search terms.

2.4. Study Selection

Records identified through database searches were uploaded to EndNote X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). Following the removal of duplicates, a title/abstract/keyword review of all identified studies was conducted by two researchers (S.J.C and D.R.), who worked independently, with any discrepancies being discussed until 100% agreement was reached. Identical procedures, involving the same researchers, were employed in the full-text evaluation of studies for inclusion. Finally, citation searches of identified reports were conducted in order to identify additional records that may not have been identified in database searches.

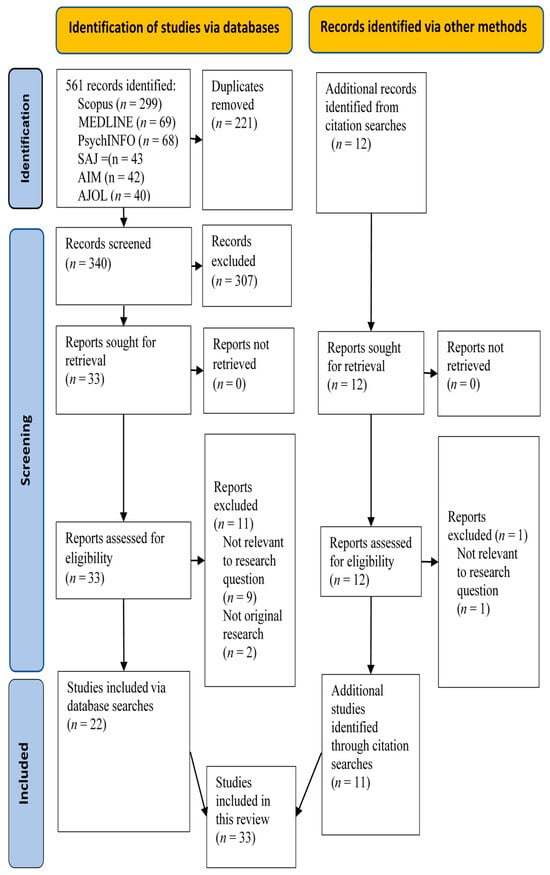

These procedures identified 33 unique records that were included in this review [18,19,20,21,25,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94], with 22 records being identified via database searches [18,19,20,21,25,67,68,70,72,73,74,75,76,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,89,90] and 11 records being identified via citation searches [69,71,77,78,86,87,88,91,92,93,94]. References for the 33 studies included in this review are provided in the Reference Section and are presented separately in Supplementary Data S2.

The PRISMA flow diagram for this selection procedure was guided by the updated framework developed by Page and colleagues [65], with the PRISMA template for searches involving both database searches and searches using additional procedures being employed in this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (AJOL = African Journals Online; AIM = African Index Medicus; SAJ = Sabinet African Journals).

2.5. Data Extraction

The following data were extracted from studies that were included in this review: (1) research context (geographical location, country, and country income level); (2) study design (definition of NSSI, types of NSSI studied, participant demographics, sampling strategy, research design, and data reduction strategies); (3) risk and salutary influences relating to NSSI engagement; and (4) intrapersonal, interpersonal, and sociocultural functions of NSSI. An initial data extraction sheet was developed by one researcher (S.J.C), with this sheet subsequently being adapted and augmented based on feedback provided by researchers during regular team meetings.

2.6. Data Synthesis

The process of data synthesis was informed by the JBI framework for mixed method systematic reviews (MMSR) [64], in terms of which data synthesis can be considered in terms of two key phases. The first of these phases involves data transformation using a convergent integrated approach, in terms of which data from quantitative studies are ‘qualitised’ through a process of converting quantitative data to ‘dequantified’ narrative statements in order to facilitate the integration of qualitative and ‘qualitised’ data. Thus, for example, a quantitative finding (e.g., “84% of participants reported intrapersonal functions for NSSI”) can be converted to a ‘dequantified’ narrative interpretation (e.g., “intrapersonal functions of NSSI were reported most often”). In the second phase of data synthesis, qualitative and ‘qualitised’ data are pooled and carefully perused in order to identify categories based on similarities of meaning, with these categories being aggregated to produce the overall findings of the review.

In this review, ‘qualitising’ of data was performed by all authors who worked independently. Each of these researchers conducted a careful perusal of all quantitative and mixed methods studies in order to identify quantitative statements relating to the nature and dynamics of NSSI, with all quantitative statements being transformed to ‘dequantified’ narrative statements. Following this initial data transformation stage, a meeting of all team members was held in which proposed data transformations were compared, with any discrepancies being discussed until consensus was reached. Finally, a team discussion of all researchers was arranged to confirm that proposed transformations were exhaustive and characterized by consistency in interpretation.

During this data transformation phase, it was noted that authors of studies often provided both quantitative data (normally in the Results Section) and ‘qualitised’ transformations of these data (normally in the Abstract or Discussion Sections). In such cases, the ‘qualitised’ descriptions provided by study authors were used to ensure that data transformations did not deviate significantly from meanings conveyed in the primary text. A description of all data transformations that were made during this phase is presented in Supplementary Data S4.

In the second phase of the synthesis, qualitative and ‘qualitised’ data were pooled and carefully perused in order to identify words/phrases/sentences that related to perceptions and understandings of NSSI, with these perceptions/understandings subsequently being combined into new (higher order) categories based on similarities of meaning. For example, findings that NSSI engagement was associated with efforts to reduce distressing emotional states or to produce positive affective states were included under the category ‘intrapersonal functions of NSSI’. Finally, a superordinate level of synthesis was conducted in order to identify analytic themes that went beyond identified categories to more directly address the review question (that had been put aside during earlier phases of data synthesis). For example, categories that describe specific functions of NSSI (interpersonal, intrapersonal, or sociocultural) were subsumed under the analytic theme of ‘NSSI functions’. During each of the stages of data synthesis, each of the authors of this review initially worked independently, with a series of subsequent team meetings being held in order to identify inter-rater similarities and discrepancies, with discrepancies being discussed until consensus was reached.

The process of data synthesis was iterative in nature, with adaptations and additions being made following team discussions during the course of the research process.

2.7. Quality Assessment

The quality of studies included in this review was assessed using the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT, Version 2018) [95], that contains three 5-point scales that contain different questions designed to concomitantly assess criteria relating to the methodological quality of quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods studies. Quality ratings were made independently by each of the authors of this review, with divergent ratings being discussed in a subsequent team meeting until consensus was reached. Overall, the methodological quality of studies was high, with 14 studies (42.4%) meeting all five methodological criteria [18,25,67,68,72,73,74,79,82,84,88,89,93,94], 14 studies (42.4%) meeting four out of five criteria [19,70,71,75,76,77,78,80,81,83,85,86,91,92], and the remaining five studies (15.2%) meeting three out of five criteria [20,21,69,87,90]. A detailed breakdown of quality ratings for each study is presented in Supplementary Data S5. No studies were excluded from the review based on quality ratings.

3. Results

Study findings are presented in two parts. First, a description of studies included in the review is presented and second, a detailed breakdown of the hierarchical structure that emerged from the data synthesis is provided.

3.1. Study Descriptions

A summary of study descriptions is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Study descriptions.

The data in Table 2 indicate that 33 studies were identified for this review, with these studies reporting on the experiences of 29,100 African adolescents and young adults. In terms of the World Bank classification of countries by income [96], 17 studies (51.5%) were conducted in one upper middle-income country (South Africa), 11 studies (33.3%) were conducted in lower middle-income countries (Egypt, Eswatini, Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, and Tunisia), and 5 studies (15.2%) were conducted in low-income countries (Burkina Faso, Mali, South Sudan, and Uganda). From Figure 2, it is evident that no studies were identified that reported on NSSI research conducted in the only high-income country in Africa (Seychelles), and no studies were identified that reported on NSSI research conducted in 42 out of 54 African countries.

Figure 2.

Countries in which NSSI studies were identified.

Sample sizes ranged from one (single case studies) to 11,518, with a median of 334.0 (IQR = 10.0 to 677.0), with the age of study participants ranging from 9 to 27 years (Mage = 16.5, SD = 2.4). In terms of age categories (adolescent = 10–19 years; young adult = 20–25 years), 16 studies employed exclusively adolescent samples [19,21,25,68,69,70,72,73,74,77,78,83,84,85,89,94], with a further 16 studies employing samples that contained both adolescents and young adults [18,20,67,71,75,79,80,81,82,86,87,88,90,91,92,93], and one study employing an exclusively young adult sample [76]. Sample sources included clinical settings (n = 9, 27.3%), schools (n = 8, 24.2%), tertiary educational institutions (n = 7, 21.2%), and the general community (n = 6, 18.2%), with one study (3.0%) employing samples that included both community samples and school children and two studies (6.1%) employing combined samples of school and tertiary education students. On average, there were slightly more females than males in the study samples (Mfemale = 58.9%), with sampling strategies involving convenience sampling in 29 studies (87.9%) and probability sampling in four studies (12.1%), with this primary reliance on convenience samples serving to limit the generalisability of study findings. Among the four studies that reported probability sampling, three studies involved samples drawn from the general community and one study involved a school sample, with there being no studies that involved participants drawn from clinical settings. With regard to DSM frequency and duration requirements, only one study met DSM requirements for NSSI (at least five times in the past year) [18], with only one study meeting the frequency requirement [18], and nine studies meeting the duration requirement [18,19,25,76,82,89,90,92,94].

Regarding research design, all studies employed cross-sectional designs. Quantitative methods were employed in 22 studies (66.7%) [18,19,20,21,25,75,77,78,79,80,81,83,84,85,86,87,88,90,91,92,93,94] and qualitative methods in nine studies (27.3%) [67,68,71,72,73,74,76,82,89], with a mixed method approach being adopted in two studies (6.1%) [69,70]. Modes of data collection included structured or semi-structured questionnaires (18 studies, 54.5%), in-depth interviews (seven studies, 21.2%), clinical assessments (three studies, 9.1%), structured or semi-structured interviews (3 studies, 9.1%), and/or clinical file reviews (two studies, 6.1%).

In sum, reviewed studies were characterised by marked heterogeneity (in relation to sampling, measurement, and design) that is likely to be reflected in methodological variance in study findings.

3.2. Data Synthesis

The process of data synthesis identified three broad analytic themes—the nature of NSSI, risk/protective factors associated with NSSI engagement, and the functions of NSSI—with each of these themes comprising subordinate categories that were identified with regard to similarities in meaning between narrative descriptions identified in the initial phases of data synthesis.

3.2.1. Analytic Theme 1: The Nature of NSSI

For the most part, conceptualizations of NSSI in the reviewed studies were consistent with the diagnostic criteria for NSSI provided in recent editions of the DSM and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) [97,98], with all identified instances of NSSI involving deliberate self-injury to the surface of the body in the absence of suicidal intent. However, DSM frequency and duration requirements (five times in the past 12 months) were only met in one study [18], with eight studies (24.2%) [19,25,76,82,89,90,92,94] focusing on a 12-month duration period and a frequency of exposure of at least once, with most studies (n = 24, 72.7%) focusing on lifetime exposure and a frequency of at least once [20,21,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,77,78,79,80,81,83,84,85,86,87,88,91,93].

With respect to conceptualizing types of NSSI behaviours, a number of measurement strategies were used to assess types of NSSI engagement, including psychometric tests that were originally developed and validated in the USA or Europe [20,75,79,81,83,85,88,92], with no efforts being reported relating to any modifications that were made to accommodate types of NSSI that may be unique to the African context (assessment instruments used in these studies are described in Supplementary Data S6). There were, however, two studies [80,86] that assessed for NSSI functions using an assessment instrument—the Self-Punishment Scale (SPS) [99]—that was developed and validated for use with Egyptian samples. In addition to assessing for physical self-harm (corresponding to DSM criteria for NSSI), the SPS also assesses other forms of non-suicidal self-harm behaviours including: (a) self-deprivation (e.g., “I deprive myself of sleep and food”), (b) thinking and affective self-harm (e.g., “I do things to make other people hate me”), and self-neglect (e.g., “I don’t care about my health”).

Although three studies did employ a process of translation and back translation to ensure the semantic equivalence of research instruments [78,88,92], no efforts were reported relating to efforts designed to ensure the broader sociocultural validity of test items. Additional procedures that were used to assess types of NSSI included (a) the use of author-developed measures that relied largely on the item content of available psychometric measures [18,19,72,78,91,93,94], (b) the use of single open-ended questions (e.g., “Have you ever harmed yourself on purpose in a way that was not to take your life?”) that provided opportunities for participants to mention novel types of NSSI that were salient to them [21,68,71,74,82,84,87], and (c) single case studies that reported on ‘unusual’ types of deliberate self-harm that met this review’s definition of NSSI [73,76,89].

3.2.2. Analytic Theme 2: Risk/Protective Factors for NSSI

From Table 3, it is evident that risk and/or protective factors were identified at all levels of the ecosystem in which individuals are embedded, with risk factors for NSSI being identified in 29 studies (87.9%) [18,19,20,25,67,68,69,70,71,72,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,94] and protective factors being identified in seven studies (21.2%) [21,68,69,81,82,87,91]. Risk factors that were mentioned most often were a current or past history of mental health problems (16 studies, 48.5%) [19,25,67,68,77,78,79,80,82,84,86,87,88,90,91,94], a history of exposure to adverse childhood experiences (12 studies, 36.4%) [18,25,68,69,72,74,77,79,81,82,83,89], and demographic factors including age and sex (11 studies, 33,3%) [18,19,20,25,73,75,76,77,79,83,90]. Contrary to expectations, country income level (lower-income, LMI, or UMI) did not emerge as a significant risk factor for NSSI engagement. With regard to salutary influences, factors associated with a reduced risk for NSSI engagement included an older age [87], low levels of mindfulness in relation to NSSI engagement [69], high levels of self-esteem [87], social-support-orientated coping [21], social support from parents, peers, or welfare organizations [82], and a strong desire to adhere to legal and/or cultural proscriptions against self-harming behaviours [82].

Table 3.

Risk/salutary influences on NSSI engagement.

At a broader level, some studies found that NSSI outcomes were influenced by interactions or synergies involving both risk and salutary factors as well as influences emanating from different ecosystemic levels. For example, in the study conducted by Quarshie and colleagues [82], it was found that exposure to adverse events in the home involved influences emanating from the intrapersonal level (e.g., the individual’s sex), the interpersonal level (e.g., punitive or abusive parenting styles), and the socio-cultural level (culturally defined perceptions regarding appropriate parenting practices). Such synergies are, of course, not particularly surprising in the context of contemporary conceptualizations of risk and resilience in terms of which the outcome of exposure to adverse life events has been found to be influenced by multisystemic transactions or synergies [100,101,102,103].

3.2.3. Analytic Theme 3: Functions of NSSI

The functions of NSSI reported in reviewed studies are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Functions of NSSI.

4. Discussion

This paper reviewed 33 studies with the aim of investigating what is known about the nature and dynamics of NSSI among African youth. A number of important conclusions can be derived from the results.

At a broad level, these data suggest that NSSI engagement is influenced by risk and resilience factors operating across all levels of the ecosystem in which the individual is embedded, with there being evidence to suggest that there may be synergies between influences operating at different systemic levels [82]. This holistic perspective on NSSI dynamics is not only consistent with African conceptualisations of mental and physical health [43,60,61,62] but is also consistent with contemporary Western perspectives in terms of which health is defined as a state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing [104], with a notion of multisystemic interactions underlying contemporary Western conceptualizations of risk and resilience [100,101,102,103]. Thus, while there may be differences in the behavioural manifestations of NSSI across different cultural settings, as well as possible cross-cultural differences in the nature and dynamics of multisystemic transactions in relation to NSSI, the broader holistic conceptualization of NSSI that emerged from this review may have universal relevance.

With regard to risk and protective factors for NSSI, study data suggest that the primary focus of identified studies was on pathogenic influences on NSSI outcomes, with comparatively few studies adopting a complementary salutogenic perspective that focused on factors that promote well-being and resilience (see Table 3). Consistent with the view that stress occurs when individuals, who are nested in family, social, and cultural relationships, experience a threat to valued assets or resources [102], risk and salutary influences for NSSI were identified at all levels of the ecosystem in which individuals were embedded, with there being evidence that there may be synergies between certain risk and salutary influences. For example, in the study by Kok and colleagues [69], it was found that individuals who act mindfully are more likely to engage in self-harming behaviours (a risk factor) but less likely to engage in NSSI behaviours involving more serious injury (a protective factor). As such, a more comprehensive perspective on the interplay between NSSI risk and salutary influences would appear to be indicated.

Further, the risk factors that were mentioned most often in reviewed studies (mental illness, exposure to ACES, age, and sex) correspond largely to findings from the extant literature [14,16,22,23,27,30,37,38]. However, this review identified a number of socially mediated risk factors for NSSI—including discrimination, acculturation, and noncompliance with socially prescribed rituals [25,76,82,89]—that have not adequately been considered in the extant literature, and which could therefore usefully be considered in future research.

The functions of NSSI identified in this study provide partial support for dominant Western conceptualizations of NSSI [57,58], in terms of which NSSI is regarded as serving primarily intrapersonal and/or interpersonal functions. However, in this review, a number of studies [25,76,82,89] additionally considered sociocultural functions of NSSI which were designed to cope with socially mediated forms of distress and/or to obtain a desired sociocultural reaction, with the incremental validity of this extended definition of NSSI functions being suggested by the fact that some types of NSSI engagement were found to involve transactions between sociocultural functions and intrapersonal and/or interpersonal functions [25,76,82,89].

At a broader level, studies in this review that assessed for NSSI using measures developed in Western countries have tended, not surprisingly, to produce findings that largely mirror Western conceptualisations of NSSI in terms of risk factors for, types of, and the functions of NSSI [19,72,78,91,93,94]. However, exploratory studies that have employed broad open-ended questions (e.g., “Have you ever harmed yourself on purpose in a way that was not to take your life?”), that provide opportunities for participants to mention novel types of NSSI that are salient to them [21,68,71,74,82,84,87], have provided a broader socially contextualised conceptualisation of the nature and dynamics of NSSI that would appear to be more congruent with African emic understandings. Finally, the one measure of NSSI that was identified in this review—the Self-Punishment Scale (SPS) [99]—that was developed and validated for use with African samples, assesses not only physical self-injury (as per the DSM), but also other forms of non-suicidal self-harm, including (a) self-deprivation (e.g., “I deprive myself of sleep and food”), (b) thinking and affective self-harm (e.g., “I do things to make other people hate me”), and self-neglect (e.g., “I don’t care about my health”). This broader conceptualisation of NSSI would appear to reflect the fact that African conceptualisations of NSSI may be informed by different/emic understandings that are not adequately captured by contemporary Western psychiatric conceptualisations.

4.1. Implications for Research on NSSI

Taken together, the holistic perspective on NSSI that emerged in this review would appear to have implications for future research.

First, at a most fundamental level, the notion of cultural sensitivity in NSSI research could be likened to a two-sided mirror that on one surface reflects the emic understandings of study participants and on the other surface reflects the etic understandings of the researcher, with ‘etic intrusion’ occurring in situations where research is designed and conducted in ways that foreground researchers’ etic preconceptions in ways that mask or preclude the expression of participants’ emic understandings. Thus, for example, in this review, ‘etic intrusion’ was evident in (a) a reliance on assessment instruments that were developed in Europe and the USA, which largely reflect the perspective of contemporary Western psychiatry, and (b) truncated conceptualizations of the nature and dynamics of NSSI that were developed in high-income countries, which, to a large part, fail to provide a holistic perspective on an individual’s familial, social, and cultural embeddedness. As such, there would appear to be a clear need for NSSI researchers to ensure that etic intrusion is avoided (or at least minimized) through the use of appropriately adapted/developed research instruments and/or a reliance on conceptualizations of the nature and dynamics of NSSI that are congruent with research participants’ emic understandings.

Second, reviewed studies did not provide an adequate basis for exploring distinctions in the functions of NSSI across different regional and sociocultural contexts on the African continent, with there being a need for future research designed to specifically address this issue.

Third, with regard to gaining an understandings of participants’ emic understandings of NSSI (and indeed of any social issue), Ungar and colleagues [101] recommend that community leaders and potential research participants should be recruited as ‘citizen co-researchers’, with such co-researchers playing an active role in the conceptualization, design, and interpretation of research findings. From an ethical perspective, and particularly in relation to research involving children and adolescents, this notion of positioning participants as ‘co-researchers’ is, of course, entirely consistent with the proposals outlined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (see particularly Article 12) [105].

Fourth, the process of studying NSSI from a multisystemic perspective is likely to pose some additional challenges for researchers. As Ungar and colleagues [101] point out, such studies should ideally involve multidisciplinary research teams who are open to seeking linkages between different theoretical perspectives, and who are prepared to “work outside their intellectual comfort zones and engage in scientific methods that are less familiar” (p. 12). Such potential obstacles clearly need to be acknowledged, pre-empted, and addressed in any multisystemic research.

Fifth, and finally, it is important to consider the extent to which the findings from this review may have relevance to studies conducted in developed countries. After all, countries in North America and Europe have multicultural populations, with different sub-populations possibly having their own nuanced emic understandings of the nature and dynamics of NSSI. This is, however, not a question that can be answered based on findings from this review but may constitute a fruitful line of enquiry for future research studies.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this review represents the first attempt to explore factors related to the nature and dynamics of NSSI among adolescents and young adults living on the African continent, with (a) searches being conducted using six databases (PubMed, Scopus, PsychINFO, African Journals Online, African Index Medicus, and Sabinet African Journals) augmented by forward and full-text citation searches in identified records, (b) reporting procedures being informed by the updated PRISMA 2020 statement [65], and (c) the review being guided by the JBI methodology for systematic mixed methods reviews [64]. A further strength of this review is that it provides social researchers with a broader, socially contextualized, conceptualization of the nature and dynamics of NSSI as well as an extended perspective of research participants as being nested in multiple, interrelated, ecosystemic levels of influence.

However, the inclusion criterion that restricted all searches to adolescents and young adults may have excluded some potentially relevant studies. Second, the cross-sectional nature of reviewed studies limits the confidence with which causal inferences can be made, and third, the fact that NSSI studies were only identified in 22% of all African countries, with low-income countries being particularly underrepresented, suggests that study findings may not be generalizable to all African countries.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/adolescents5040067/s1, Data S1: Syntax employed in database searches; Data S2: References for studies included in the review; Data S3: The PRISMA 2020 checklist for systematic reviews; Data S4: The process of ‘qualitising’ data; Data S5: Quality of studies evaluated using MMAT criteria; Data S6: Validated instruments used to assess for NSSI; Data S7: Research protocol.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J.C., S.R.V. and D.R.; Methodology, S.J.C., S.R.V. and D.R.; Formal analysis, S.J.C. and S.R.V.; Writing—original draft, S.J.C. and S.R.V.; Writing—review and editing, S.R.V., S.J.C. and D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Study data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Angelotta, C. Defining and refining self-harm: A historical perspective on nonsuicidal self-injury. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2015, 203, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, S. Psyche on the Skin: A History of Self-Harm; Reakton Books: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kahan, J.; Pattison, E.M. Proposal for a distinctive diagnosis: The Deliberate Self-Harm Syndrome (DSH). Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 1984, 14, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetterqvist, M.; Lundh, L.-G.; Dahlström, Ö.; Svedin, C.G. Prevalence and function of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in a community sample of adolescents, using suggested DSM-5 criteria for a potential NSSI disorder. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013, 41, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brager-Larsen, A.; Zeiner, P.; Mehlum, L. DSM-5 non-suicidal self-injury disorder in a clinical sample of adolescents with recurrent self-harm behavior. Arch. Suicide Res. 2023, 28, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muehlenkamp, J.J.; Brausch, A.M.; Washburn, J.J. How much is enough? Examining frequency criteria for NSSI disorder in adolescent inpatients. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armoon, B.; Mohammadi, R.; Griffiths, M.D. The global prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury, suicide behaviours, and associated risk factors among runaway and homeless youth: A meta-analysis. Community Ment. Health 2024, 60, 919–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, B.F.; Takacs, Z.K.; Kollárovics, N.; Balázs, J. The prevalence of self-injury in adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 3439–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillies, D.; Christou, M.A.; Dixon, A.C.; Featherston, O.J.; Rapti, I.; Garcia-Anguita, A.; Villasis-Keever, M.; Reebye, P.; Christou, E.; Al Kabir, N.; et al. Prevalence and characteristics of self-harm in adolescents: Meta-analyses of community-based studies 1990-2015. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 57, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, K.S.; Wong, C.H.; McIntyre, R.S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Tran, B.X.; Tan, W.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Global lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury in children and adolescents between 1989 and 2018: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moloney, F.; Amini, J.; Sinyor, M.; Schaffer, A.; Lanctôt, K.L.; Mitchell, R.H.B. Sex differences in the global prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents: A meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2415436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muehlenkamp, J.J.; Claes, L.; Havertape, L.; Plener, P.L. International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2012, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swannell, S.V.; Martin, G.E.; Page, A.; Hasking, P.; St John, N.J. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2014, 44, 273–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Song, X.; Huang, L.; Hou, D.; Huang, X. Global prevalence and characteristics of non-suicidal self-injury between 2010 and 2021 among a non-clinical sample of adolescents: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 912441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresin, K.; Schoenleber, M. Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 38, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarshie, E.N.; Waterman, M.G.; House, A.O. Self-harm with suicidal and non-suicidal intent in young people in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penning, S.L.; Collings, S.J. Perpetration, revictimization, and self-injury: Traumatic re-enactments of child sexual abuse in a nonclinical sample of South African adolescents. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2014, 23, 708–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlebusch, L. Self-destructive behaviour in adolescents. S. Afr. Med. J. 1985, 68, 792–795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van der Walt, F. Self-harming behaviour among university students: A South African case study. J. Psychol. Afr. 2016, 26, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wal, W.; George, A.A. Social support-oriented coping and resilience for self-harm protection among adolescents. J. Psychol. Afr. 2018, 28, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plener, P.L.; Schumacher, T.S.; Munz, L.M.; Groschwitz, R.C. The longitudinal course of non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm: A systematic review of the literature. Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregul. 2015, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiekens, G.; Hasking, P.; Claes, L.; Mortier, P.; Auerbach, R.P.; Boyes, M.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Green, J.G.; Kessler, R.C.; et al. The DSM-5 nonsuicidal self-injury disorder among incoming college students: Prevalence and associations with 12-month mental disorders and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, X. Non-suicidal self-injury function: Prevalence in adolescents with depression and its associations with non-suicidal self-injury severity, duration and suicide. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1188327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, S.J.; Valjee, S.R. A multi-mediation analysis of the association between adverse childhood experiences and non-suicidal self-injury among South African Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenk, C.E.; Noll, J.G.; Cassarly, J.A. A multiple mediational test of the relationship between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.T.D.; Wong, P.W.C.; Lee, A.M.; Lam, T.H.; Fan, Y.S.S.; Yip, P.S.F. Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: Prevalence, co-occurrence, and correlates of suicide among adolescents in Hong Kong. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013, 48, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, B.S. Early childhood environment and genetic interactions: The diathesis for suicidal behavior. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, N.; Lugo-Marín, J.; Oriol, M.; Pérez-Galbarro, C.; Restoy, D.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A.; Ferrer, M. Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescent population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2024, 157, 107048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, A.Y.Y.; Hartanto, A.; Wan, T.S.; Teo, S.S.M.; Sim, L.; Sandeeshwara Kasturiratna, K.T.A. The impact of childhood sexual, physical and emotional abuse and neglect on suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychiatry Res. Commun. 2025, 5, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin-Vézina, D.; De La Sablonnière-Griffin, M.; Sivagurunathan, M.; Lateef, R.; Alaggia, R.; McElvaney, R.; Simpson, M. “How many times did I not want to live a life because of him”: The complex connections between child sexual abuse, disclosure, and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Bord. Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregul. 2021, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.Y.; Liu, J.; Zeng, Y.Y.; Conrad, R.; Tang, Y.L. Factors associated with non-suicidal self-injury in Chinese adolescents: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 747031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; Zhang, L. Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: Testing a moderated mediating model. J. Interpers. Violence 2024, 39, 925–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Huang, J.; Shang, Y.; Huang, T.; Jiang, W.; Yuan, Y. Child maltreatment exposure and adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: The mediating roles of difficulty in emotion regulation and depressive symptoms. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.; Jiang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Gong, T.; Liu, X.; Leung, F.; You, J. Distress intolerance mediates the relationship between child maltreatment and nonsuicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: A three-wave longitudinal study. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 2220–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.T.; Scopelliti, K.M.; Pittman, S.K.; Zamora, A.S. Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagtegaal, M.H.; Boonmann, C. Child sexual abuse and problems reported by survivors of CSA: A meta-review. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2021, 31, 147–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Li, X.; Ng, C.H.; Xu, D.W.; Hu, S.; Yuan, T.F. Risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents: A meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 46, 101350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellerman, J.K.; Millner, A.J.; Joyce, V.W.; Nash, C.C.; Buonopane, R.; Nock, M.K.; Kleiman, E.M. Social support and non-suicidal self-injury among adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2022, 50, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simundic, A.; Argento, A.; Mettler, J.; Heath, N.L. Perceived social support and connectedness in non-suicidal self-injury engagement. Psychol. Rep. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Li, W.; Ding, W.; Song, S.; Qian, L.; Xie, R. Your support is my healing: The impact of perceived social support on adolescent NSSI—A sequential mediation analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 43, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Liang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, X. Social support and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: The differential influences of family, friends, and teachers. J. Youth Adolesc. 2025, 54, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Hoye, A.; Slade, A.; Tang, B.; Holmes, G.; Fujimoto, H.; Zheng, W.Y.; Ravindra, S.; Christensen, H.; Calear, A.L. Motivations for self-Harm in young people and their correlates: A systematic review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2025, 28, 171–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westers, N.J. Cultural interpretations of nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide: Insights from around the world. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 1231–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurigio, A.J.; Nesi, D.; Meyers, S.M. Nonsuicidal self-injury among young adults and adolescents: Historical, cultural and clinical understandings. Soc. Work. Ment. Health 2023, 22, 122–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Hou, Y.; Liu, D.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X. Influential factors of non-suicidal self-Injury in an Eastern cultural context: A qualitative study from the perspective of school mental health professionals. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 681985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.T.; Sheehan, A.E.; Walsh, R.F.L.; Sanzari, C.M.; Cheek, S.M.; Hernandez, E.M. Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 74, 101783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisler, S.; Sleman, S.; Orgler, M.; Tossman, I.; Hamdan, S. Examining the relationship between non-suicidal self-injury and mental health among female Arab minority students: The role of identity conflict and acculturation stress. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1247175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elvina, N.; Bintari, D.R. The role of religious coping in moderating the relationship between stress and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury (NSSI). Humaniora 2023, 14, 124717511–124717521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, M.; Hamza, C.A.; Willoughby, T. A longitudinal investigation of the relation between nonsuicidal self-injury and spirituality/religiosity. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 250, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.S. Cross-cultural representations of NSSI. In The Oxford Handbook of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury; Lloyd-Richardson, E.E., Baetens, I., Whitlock, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2024; pp. 167–186. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, M.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Qian, H.; Zhu, P.; Xu, X. Family intimacy and adaptability and non-suicidal self-injury: A mediation analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Xiang, Y. Child maltreatment and nonsuicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: The mediating effect of psychological resilience and loneliness. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 133, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Li, Z.; Ma, T.; Jiang, X.; Yu, C.; Xu, Q. Stressful life events and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model of depression and resilience. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 944726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Cai, Y.; Pan, M. Correlation analysis of non-suicidal self-injury behavior with childhood abuse, peer victimization, and psychological resilience in adolescents with depression. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2024, 52, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorobi, M.A.; Mahfar, M.; Fakhruddin, F.M.; Senin, A.A. The Relationship between resilience, loneliness, and non-suicidal self-injurious behavior among adolescents in Johor Bahru. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2024, 14, 1714–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Prinstein, M.J. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 72, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.J.; Jomar, K.; Dhingra, K.; Forrester, R.; Shahmalak, U.; Dickson, J.M. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 227, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, A.; Luyckx, K.; Adhikari, A.; Parmar, D.; Desousa, A.; Shah, N.; Maitra, S.; Claes, L. Non-suicidal self-injury and its association with identity formation in India and Belgium: A cross-cultural case-control study. Transcult. Psychiatry 2021, 58, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamrezaei, M.; De Stefano, J.; Heath, N.L. Nonsuicidal self-injury across cultures and ethnic and racial minorities: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2017, 52, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogolo, G. On a socio-cultural conception of health and disease in Africa. Afr. Riv. Trimest. Stud. Doc. Ist. Ital. Africa Oriente 1984, 41, 390–404. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40760024 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Edet, R.; Bello, O.I.; Babajide, J. Culture and the development of traditional medicine in Africa. J. Adv. Res. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2019, 6, 22–28. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/827 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Curtis, A.C. Defining adolescence. J. Adolesc. Fam. Health 2015, 7, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lizarondo, L.; Stern, C.; Carrier, J.; Godfrey, C.; Rieger, K.; Salmond, S.; Apostolo, J.; Kirkpatrick, P.; Loveday, H. Mixed methods systematic reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024; Chapter 8; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER Tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J. Motives Underlying Bulimic and Self-Mutilating Behaviour. Master’s Thesis, Rand Afrikaans University, Johannesburg, South Africa, 1996. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10210/7573 (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Toerien, S. Selfdestruktiewe Gedrag by Die Adolessent: ‘n Maatskaplikewerkperspektief (Self-Destructive Behaviour in the Adolescent: A Social Work Perspective). Master’s Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2006. Available online: https://repository.up.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/7a6f4c05-46b8-43e8-8e79-96ab9fd07cac/content (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Kok, R.; Kirsten, D.K.; Botha, K.F.H. Exploring mindfulness in self-injuring adolescents in a psychiatric setting. J. Psychol. Afr. 2011, 21, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, S. Deliberate Self-Harm Among Adolescents in South African Children’s Homes. Master’s Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2011. Available online: https://repository.up.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/df293fe8-579c-4236-81d3-bc819f33a9e4/content (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Bheamadu, C.; Fritz, E.; Pillay, J. The experiences of self-injury amongst adolescents and young adults within a South African context. J. Psychol. Afr. 2012, 22, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgway, M.J. Every Scar Tells a Story: The Meaning of Adolescent Self-Injury. Master’s Thesis, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2013. Available online: https://scholar.sun.ac.za/items/62e33aab-f581-4033-a7da-039bfced87f9 (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Akhaddar, A.; Malih, M. Neglected painless wounds in a child with congenital insensitivity to pain. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2014, 17, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfman, D.; Jacobs, I. An only-child adolescent’s lived experience of parental divorce. Child Abuse Res. S. Afr. J. 2015, 16, 116–129. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC180366 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Idemudia, E.S.; Mokoena, K.M.; Maepa, M.M. Dynamics of gender, age, father involvement and adolescents’ self-harm and risk-taking behaviour in South Africa. Gend. Behav. 2016, 14, 6846–6859. [Google Scholar]

- Kintu-Luwaga, R. The emerging trend of self-circumcision and the need to define cause: Case report of a 21-year-old male. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2016, 25, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancheva, V.P. Self-Mutilation in Adolescents Admitted to Tara Psychiatric Hospital: Prevalence and Characteristics. Master’s Thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2016. Available online: https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/bitstreams/0659521b-efe5-4491-9b0c-78656fcc8dd7/download (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Guedria-Tekari, A.; Missaoui, S.; Kalai, W.; Gaddour, N.; Gaha, L. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Tunisian adolescents: Prevalence and associated factors. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 34, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, S. The prevalence, nature, and functions of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in a South African student sample. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2019, 39, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, A.A.; Mohamed, N.A. Prevalence and correlates of deliberate self-harming behaviors among nursing students. J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2019, 8, 52–61. Available online: https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jnhs/papers/vol8-issue2/Series-7/G0802075261.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Maepa, M.P.; Ntshalintshali, T. Family structure and history of childhood trauma: Associations with risk-taking behavior among adolescents in Swaziland. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 563325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarshie, E.N.-B.; Waterman, M.G.; House, A.O. Adolescent self-harm in Ghana: A qualitative interview-based study of first-hand accounts. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyneke, A.; Naidoo, S. An exploration of the relationship between interpersonal needs and nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents. S. Afr. J. Soc. Work Soc. Dev. 2020, 32, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boduszek, D.; Debowska, A.; Ochen, E.A.; Fray, C.; Nanfuka, E.K.; Powell-Booth, K.; Turyomurugyendo, F.; Nelson, K.; Harvey, R.; Willmott, D.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among children and adolescents: Findings from Uganda and Jamaica. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 283, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduaran, C.; Agberotimi, S.F. Moderating effect of personality traits on the relationship between risk-taking behaviour and self-injury among first-year university students. Adv. Ment. Health 2021, 19, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Nagar, Z.M.; Barakat, D.H.; Rabie, M.A.E.M.; Thabeet, D.M.; Mohamed, M.Y. Relation of non-suicidal self-harm to emotion regulation and alexithymia in sexually abused children and adolescents. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2022, 31, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedong, W.; Coulibaly, S.P.; Sidibe, A.M.; Hesketh, T. Self-harm, suicidal ideation and attempts among school-attending adolescents in Bamako, Mali. Children 2022, 9, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebalu, T.I.; Kearns, J.C.; Ouermi, L.; Bountogo, M.; Sié, A.; Bärnighausen, T.; Harling, G. Prevalence and correlates of adolescent self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: A population-based study in Burkina Faso. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2023, 69, 1626–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudugbe, S.; Acquah, E.P.K.; Akuaku, R.S.; Jaaga, B.N.N.B.; Maison, P. Teasing-induced self-circumcision in a teenager: A case report. J. Adv. Med. Med. Res. 2023, 35, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaguga, F.; Mathai, M.; Ayuya, C.; Francisca, O.; Musyoka, C.M.; Shah, J.; Atwoli, L. 12-month substance use disorders among first-year university students in Kenya. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukoyi, O.; Orok, E.; Oluwafemi, F.; Oni, O.; Oluwadare, T.; Ojo, T.; Bamitale, T.; Jaiyesimi, B.; Iyamu, D. Factors influencing suicidal ideation and self-harm among undergraduate students in a Nigerian private university. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2023, 30, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, E.A.; Haggag, W.; Anwar, K.A.; Sayed, H.; Ibrahim, O. Methods and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in an adolescent and young adult clinical sample. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2024, 31, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Wolke, D.; Bärnighausen, T.; Ouermi, L.; Bountogo, M.; Harling, G. Sexual victimisation, peer victimisation, and mental health outcomes among adolescents in Burkina Faso: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2024, 11, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erskine, H.E.; Maravilla, J.C.; Wado, Y.D.; Wahdi, A.E.; Loi, V.M.; Fine, S.L.; Li, M.; Ramaiya, A.; Wekesah, F.M.; Odunga, S.A.; et al. Prevalence of adolescent mental disorders in Kenya, Indonesia, and Viet Nam measured by the National Adolescent Mental Health Surveys (NAMHS): A multi-national cross-sectional study. Lancet 2024, 403, 1671–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: A modified e-Delphi study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 111, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, N.; Van Rompaey, C.; Metreau, E.; Eapen, S.G. New World Bank Country Classifications by Income Level: 2022–2023. 2022. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2022-2023 (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision (ICD-11), World Health 2019/2021. Available online: https://icd.who.int/en/ (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Shoqer, Z. Scale of Diagnosing Self-Punishment, 1st ed.; Nahdet Misr Publishing: Cairo, Egypt, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Theron, L.; Ungar, M.; Höltge, J. Pathways of resilience: Predicting school management trajectories for South African adolescents living in a stressed environment. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 69, 102062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M.; Theron, L.; Murphy, K.; Jeffries, P. Researching multisystemic resilience: A sample methodology. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Lucke, C.M.; Nelson, K.M.; Stallworthy, I.C. Resilience in development and psychopathology: Multisystem perspectives. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 17, 521–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Basic Documents, 49th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/pdf_files/BD_49th-en.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Treaty Series. 1989. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/crc.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).