Abstract

Participation in running events has expanded worldwide, consolidating itself as a form of active leisure and a driver of social and tourism engagement. Although runners’ motivations have been extensively studied, perceived inclusivity, understood as motivation derived from the event’s promotion of equitable participation across gender, age and functional ability, has rarely been examined as a distinct motivational dimension within structural models. This study analyses the motivational structure of participants in the Elche Half Marathon (Spain) and assesses the incremental contribution of inclusivity to traditional motivational frameworks. Based on a sample of 1053 valid responses, a two-stage psychometric and segmentation approach was applied. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (EFA and CFA) were conducted to compare a four-factor model (sport-related hedonism, competition, socialization and digital socialization) with an extended five-factor model incorporating inclusivity. Subsequently, cluster analyses were performed using factor scores derived from each model. The results show that the inclusion of inclusivity improves model fit and increases explained variance, while also generating a more differentiated segmentation structure. The extended model revealed six motivational profiles, some of which displayed continuity with the classical solution, while others were reconfigured when inclusivity was introduced. Overall, the findings indicate that inclusivity functions as a complementary and context-dependent motivational dimension that refines the understanding of participation heterogeneity in running events. Rather than replacing traditional motives, inclusivity contributes incremental explanatory value and enhances the identification of motivational profiles, offering relevant insights for the design and management of mass-participation sporting events.

Keywords:

motivation; inclusion; running events; half marathon; sporting events; sports tourism; Elche (Spain) 1. Introduction

Participation in long-distance running events has become one of the most representative forms of popular sport and active tourism in recent decades, combining physical, social, and emotional dimensions that transcend the strictly competitive sphere (Scheerder & Helsen, 2023). This phenomenon has been driven by the growth of healthy leisure, the pursuit of psychological well-being, and the global expansion of sporting events as platforms for identity and belonging (Zach et al., 2017). Within this framework, urban races (particularly marathons and half marathons) have emerged as meeting spaces that integrate sport, tourism, and community, generating growing interest among researchers, managers, and public administrators (Malchrowicz-Mośko et al., 2020).

Scientific literature has addressed motivation to participate in running events from multiple theoretical approaches, most notably Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985), Serious Leisure Theory (Stebbins, 1982), and Flow Theory (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). These perspectives have helped identify various motivational dimensions, including sport-related hedonism, socialization, competition, club affiliation, and personal well-being (Parra-Camacho et al., 2019; Pereira et al., 2021). More recent research has converged toward a more parsimonious motivational structure based on core dimensions, such as hedonism, competition or personal challenge, socialization, and digital interaction (Parra-Camacho et al., 2019; Stragier et al., 2018; Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024). However, despite significant advances in the measurement and validation of instruments, theoretical fragmentation persists, limiting cross-study comparability and the practical application of findings to sports tourism management (Hammer & Podlog, 2016).

In recent years, a conceptual shift has emerged toward incorporating new and cross-cutting dimensions in the study of sport motivation, such as digital interaction and social inclusion (Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024). The former reflects the influence of social media and virtual communities on runners’ identity construction and symbolic recognition (Van de Pol, 2023). The motivation based on inclusion refers specifically to participants’ perceived inclusivity, understood as the subjective perception that an event facilitates and promotes equitable participation across gender, age, and functional ability, beyond the mere presence of diverse groups or the provision of basic accessibility measures (Darcy et al., 2017; O’Brien et al., 2022). Despite its relevance, inclusion has been addressed primarily within organizational, policy, or governance frameworks, and only to a limited extent as a psychological motivational dimension shaping individual participation decisions (Hiemstra & Rana, 2024).

Against this backdrop, the present study seeks to address this gap by integrating the inclusion dimension into a comprehensive motivational model applied to the case of the Elche Half Marathon, one of the oldest races in Europe and a reference point in Spain’s popular running tradition (Media Elche, 2025a). The suitability of this event as a case study lies not only in its large-scale participation and international profile, but also in its explicit commitment to inclusive values at both institutional and organizational levels. On the one hand, official communications by the Elche City Council have highlighted the progressive incorporation of categories for runners with disabilities, framing the event as an inclusive sporting initiative (Ayuntamiento de Elche, 2022). On the other hand, the official regulations of the event formalize inclusion through specific measures, such as differentiated categories for athletes with sensory, physical, and intellectual disabilities, reduced registration fees, and the provision of free guides for visually impaired runners (Media Elche, 2025b). The article is structured into the following sections: introduction, literature review, hypotheses, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusions, offering both an empirical and conceptual contribution to understanding inclusion as an emerging explanatory axis in sports motivation research.

Accordingly, this study addresses the following research question.

Research Question: To what extent does the incorporation of the inclusion dimension modify the motivational structure and segmentation of participants in running events such as the Elche Half Marathon?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Motivation in Distance Running and Sport Tourism Participation

Participation in running events has grown steadily over recent decades, consolidating itself as a form of active leisure, personal development, and social engagement on a global scale (Scheerder & Helsen, 2023). This expansion has generated substantial scientific interest in identifying the motivations that drive runners, forming a rich and diversified body of theoretical and empirical studies (Zach et al., 2017; Malchrowicz-Mośko et al., 2020). Among the principal explanatory frameworks, Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985), Serious Leisure Theory (Stebbins, 1982), and Flow Theory (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990) stand out, often applied in conjunction with specific measurement instruments such as the Motivations of Marathoners Scale (Masters et al., 1993), the Motives for Physical Activity Measure–Revised (Ryan et al., 1997), the Sports Tourism Motivation Scale (Hungenberg et al., 2016), the Cyclist Motivation Instrument (T. D. Brown et al., 2009), and the Running Addiction Scale (Chapman & De Castro, 1990), which have been repeatedly adapted to different cultural contexts (Ruiz-Juan & Zarauz, 2015; Duclos-Bastías et al., 2021; Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024).

These adaptations have confirmed the multidimensional nature of motivation in diverse geographical settings (Duclos-Bastías et al., 2021; Dybała, 2013; Hongwei & Resza, 2021). However, the proliferation of scales has also produced theoretical dispersion, complicating cross-study comparisons and limiting knowledge transfer to sport-management practice (Hammer & Podlog, 2016; León-Quismondo et al., 2023; Nikolaidis et al., 2019). Several authors have thus emphasized the need to simplify motivational models while preserving empirical rigour (Duclos-Bastías et al., 2021; Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024). In response, recent research has tended to synthesize motivation into more compact structures combining hedonism, socialization, competition, and emerging elements such as digital interaction and inclusion (Algaba-Navarro et al., 2024; Stenseng et al., 2023; Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024, 2026; Koper et al., 2024). This trend reflects the influence of social, technological, and cultural changes that are reshaping participation in running events (Zach et al., 2017; Avello-Viveros et al., 2022).

Additionally, scholars highlight the importance of validating motivational models in diverse territorial contexts because empirical evidence remains heavily concentrated in Anglo-Saxon, urbanized environments (León-Guereño et al., 2021; Pereira et al., 2021; Barrios-Duarte & Cardoso-Pérez, 2002). Overall, motivation in half-marathon events is now a consolidated research field at the intersection of sport psychology and sport tourism (Ryan & Deci, 2020; Hungenberg et al., 2016; Guereño-Omil et al., 2024). Despite the extensive development of motivation scales in endurance sports, none of the major instruments (e.g., MOMS, MPAM-R, STMS, CMI) include items specifically addressing inclusivity, equity or social justice, which limits their ability to capture motivations linked to diversity-oriented participation (Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024).

2.2. Core Motivational Dimensions in Running Events: Hedonism, Competition, Socialization and Digital Socialization

Sport-related hedonism represents one of the most consistent determinants of participation in running events, capturing the pleasure and personal satisfaction derived from physical activity (Parra-Camacho et al., 2019; Crossman et al., 2024). Several studies concur that enjoyment is the primary driver of long-term adherence to sport and significantly predicts re-participation (Crofts et al., 2012; Kruger et al., 2016; Malchrowicz-Mośko et al., 2020). Hedonism is also linked to emotional well-being, forming a core component of intrinsic motivation within Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2020; Pereira et al., 2021). Running further enables identity expression and flow-based pleasurable experiences that reinforce competence, autonomy and personal meaning (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; Sato et al., 2018). Sport hedonism also protects against psychological burnout and supports sustained commitment (Krippl & Ziemainz, 2010; Tian et al., 2020).

Competition, in turn, relates to personal challenge, achievement, and performance-oriented goals (Nikolaidis et al., 2019; León-Guereño et al., 2020). Runners with strong competitive orientation train more frequently, achieve higher performance levels and pursue result-based objectives (Masters et al., 1993; Zarauz et al., 2016). However, excessive competitiveness can trigger obsessive patterns and increase the risk of overtraining or exercise addiction (Hammer & Podlog, 2016; Ruiz-Juan et al., 2019). The literature distinguishes harmonious from obsessive passion, indicating that only the former supports autonomy and psychological well-being (Nogueira et al., 2018). Moreover, competitive motivation varies across sociodemographic groups, with men generally scoring higher on competitiveness while women tend to prioritize psychological well-being and social connection (Malchrowicz-Mośko et al., 2020; León-Guereño et al., 2021).

Socialization constitutes another core motivational pillar in running events, capturing the relational and communal aspects of participation (Heazlewood et al., 2019; C. S. Brown et al., 2018). Participation in running groups or clubs strengthens affiliation, identity and a sense of belonging, which increases event satisfaction and future engagement (Tian et al., 2020; Wegner et al., 2019). Running communities provide emotional support and facilitate participation among newcomers, women and recreational runners (Malchrowicz-Mośko & Waśkiewicz, 2020; Partyka & Waśkiewicz, 2024). Large-scale events also act as symbolic spaces where personal achievement is intertwined with collective celebration, reinforcing the social value of the experience (F. Chen et al., 2021; Piper et al., 2022).

Digital socialization has become an integral extension of traditional socialization, reshaping how runners connect, interact and construct meaning around participation. Sports tracking applications such as Strava or RunKeeper enable performance sharing, social comparison and instant feedback, generating motivational dynamics based on recognition, affiliation and gamification (Stragier et al., 2018; Chaloupský et al., 2020; Couture, 2021). Wearables and mobile apps increase training engagement and transform running into a socially shared and measurable experience (Van Hooren et al., 2020; Baldwin, 2023). Moreover, virtual communities allow runners to express identity, negotiate social norms and challenge stereotypes—particularly among women and minority groups who use digital platforms to foster safe, inclusive participatory environments (McAndrew & Jeong, 2012; Coche, 2017). Digital interactions extend the event experience beyond race day, strengthening loyalty, emotional bonding and long-term engagement with the event brand and its community (Schoenstedt & Reau, 2010; Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024). Accordingly, digital socialization is now recognised as an established motivational dimension that complements and amplifies face-to-face social experiences in running events (Stragier et al., 2018; Couture, 2021).

2.3. Diversity, Inclusion and Social Value as Motivational Dimensions in Mass Participation Events

Inclusion in sporting events has evolved from a narrow focus on accessibility to a broader model in which diversity becomes central to the participatory experience (Filo et al., 2011; Benn & Dagkas, 2013). Early work linked inclusion to charity-based events where participants engaged in physical activity to support social causes (Filo et al., 2009; Palmer, 2016). More recently, mainstream events have incorporated categories and formats that promote participation across groups regardless of gender, age, or ability (González-García et al., 2022; Doidge et al., 2020). This evolution highlights that inclusion may itself operate as an intrinsic motivational factor among individuals who value equity and social justice (O’Brien et al., 2022; Hiemstra & Rana, 2024). As a result, inclusive motivation emerges as a new dimension that expands classical motivational frameworks (Koper et al., 2024; Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024).

Studies on disability show that participation is motivated by well-being, empowerment, and personal growth (Koper et al., 2024; Qiu et al., 2019). Research on active aging reveals that older runners emphasize meaning and health over competition, reinforcing the integrative value of inclusive events (Avello-Viveros et al., 2022; Crossman et al., 2024). Inclusion also increases participation and recognition of women and gender minorities (Deckman & McDonald, 2023; León-Guereño et al., 2021). Women report higher motivation when they perceive safe and equitable conditions (Malchrowicz-Mośko et al., 2020; Fullagar & Pavlidis, 2012). Perceived inclusion enhances event loyalty and repeat participation (Roult et al., 2015; O’Brien et al., 2022). Inclusive events also strengthen the destination’s social reputation and attract wider audiences (Bartolomé et al., 2009; Sánchez-Sánchez & Sánchez-Sánchez, 2025). Furthermore, inclusive environments foster community cohesion and prosocial values (Benn & Dagkas, 2013; Doidge et al., 2020). Thus, inclusion emerges as a first-order explanatory factor linking sport, equality, and social sustainability (González-García et al., 2022; Deckman & McDonald, 2023).

2.4. Structural Inequalities and Participation Barriers in Sport and Event Contexts

Sport is widely recognized as a global cultural arena that both reflects and reproduces broader social inequalities (Nauright, 2004; Woodward, 2012). Major and mass-participation sporting events are often embedded in urban regeneration and “city-staging” strategies that prioritize competitiveness, visibility and image-building over social equity (Dupont, 2011; Costa, 2013). Evidence from mega-events shows that these dynamics frequently deepen socio-spatial polarization, displace low-income communities and divert public resources from urgent social needs, thereby reinforcing exclusion rather than mitigating it (Maharaj, 2015; Azzali, 2019; Potter, 2016; Sharples, 2024).

Gender inequality remains persistent across sport systems, affecting participation, visibility, leadership and event experience (Pavlidis, 2018; Meir et al., 2024). Cross-national analyses indicate that men are more likely than women to attend sport events, although gender gaps tend to narrow in more gender-equal societies (Lagaert & Roose, 2018; Balish et al., 2016). Historical and contemporary research documents delayed access, inferior conditions and uneven progress for women in international competitions, sport tourism contexts and national strategies, despite explicit equality-oriented discourses (Collado Martínez et al., 2021; Huang & Tsai, 2025; Whigham et al., 2021; Pavlidis, 2018). Media studies further highlight the systematic under-representation and marginalization of women’s sport across general and specialized coverage, including Olympic settings (Marín & García, 2022; Calvo-Ortega, 2020).

Inequalities related to disability also persist in sport and event environments, which continue to privilege able-bodied participants and spectators despite formal commitments to inclusion (Smith & Thomas, 2012; Alsarve & Johansson, 2022). Ethnographic studies reveal male-dominated cultures and organizational practices that marginalize women, children and people with disabilities in both symbolic and material terms (Alsarve & Johansson, 2022; Michetti & Von Mettenheim, 2019). Although initiatives such as sensory modulation rooms and accessible venue designs demonstrate the potential for more inclusive experiences, such practices remain exceptional rather than standard (Martin et al., 2025; Davis et al., 2025). Research on disability sport further shows that limited accessibility and low public awareness constrain community participation and social inclusion for people with intellectual and physical disabilities (Jermaina et al., 2025; Haynes et al., 2025).

Socioeconomic and territorial inequalities additionally shape who benefits from sporting events and their associated legacies (Nauright, 2004; Meir et al., 2024). Studies of mega-events in BRICS countries document forced evictions, livelihood losses and human-rights violations affecting residents of disadvantaged neighbourhoods (Maharaj, 2015; Fitzgerald & Maharaj, 2022). Urban analyses of Brazil’s World Cup and Olympic projects describe the production of “staged cities” through the removal or invisibilisation of groups deemed undesirable for international audiences, including sex workers and favela residents (Carrier-Moisan, 2020; Azzali, 2019). Systematic reviews conclude that disadvantaged communities tend to experience more negative than positive legacies, such as restricted access, limited participation in decision-making and weak long-term benefits (Liang et al., 2024; S. Chen et al., 2024). Recent evidence similarly shows that education, income, age and place of residence significantly condition participation in physical activity and post-crisis return to mass events (Peng et al., 2025; Martínez-Cevallos et al., 2025).

Taken together, this evidence indicates that sport and sporting events cannot be assumed to be inherently inclusive, as they often reproduce or intensify existing social hierarchies unless explicit counter-strategies are implemented (Woodward, 2012; D’Hoore et al., 2023). These structural inequalities therefore provide the contextual backdrop for analysing inclusive motivation in mass running events, shaping how participants interpret equity, accessibility and representativeness within their event experience (Meir et al., 2024; Liang et al., 2024).

2.5. Theoretical Foundations of Inclusion in Sport and Event Participation

From a social identity perspective, sporting events constitute powerful contexts in which individuals categorize themselves and others into in-groups and out-groups, thereby reinforcing or challenging social hierarchies (Nauright, 2004; Woodward, 2012). Case studies of alternative and multicultural football tournaments illustrate that events can serve as spaces where marginalized groups articulate post-colonial or minority identities that contest dominant narratives, even though such dynamics may coexist with the reproduction of mainstream exclusions (Burdsey, 2008; Dupont, 2011). Research on diaspora futsal tournaments and refugee-focused initiatives further shows that community-organized events can strengthen belonging, cultural sustainability and intergroup solidarity. In this sense, inclusion can be understood as expanding the symbolic boundaries of “who belongs” to the sporting community, particularly for migrants, racialised groups and people with disabilities (Spaaij & Schaillée, 2020; Digennaro & Falese, 2023; Rich et al., 2015).

Critical and social justice approaches emphasize that sport is embedded in global political–economic structures, making it a site where power, resources and recognition are unevenly distributed (Maharaj, 2015). Analyses of mega-events in India, Brazil and South Africa show that event-led development frequently privileges elites and corporate interests at the expense of low-income residents, reinforcing socio-economic inequalities (Fitzgerald & Maharaj, 2022). Studies of the Rio 2016 Olympics similarly reveal tensions between inclusive rhetoric and outcomes such as spatial fragmentation and the marginalization of vulnerable populations (Azzali, 2019; Sharples, 2024). Consequently, consensus and review papers argue that inclusion must be treated as a governance issue, requiring clearly defined target groups, dedicated resources and specific leverage strategies rather than generic legacy discourse (S. Chen et al., 2024; Liang et al., 2024).

The disability-sport literature further refines this framework by showing that inclusion may oscillate between symbolic representation and substantive participation (Mendes et al., 2023). Studies on volunteers and sport management assistants with disabilities indicate that targeted training programmes and accessible roles can enable meaningful involvement, although many venues and organizational practices remain poorly adapted (Jobst & Kreinbucher-Bekerle, 2025; Martin et al., 2025). Research on spectators with physical disabilities at the PyeongChang Paralympics highlights that inclusive experiences can enhance self-efficacy, group pride and perceived social inclusion, underscoring the affective and identity-related dimensions of participation (Kim et al., 2024). At the same time, work on sensory-inclusive programming and live events demonstrates that accessibility must address sensory, informational and social barriers, not only physical infrastructure (Davis et al., 2025).

Within this theoretical landscape, inclusion in sporting events can be conceptualized as a multidimensional construct encompassing equitable access, meaningful participation, positive identity processes and perceived fairness in the distribution of benefits (Benn & Dagkas, 2013). This conceptualisation aligns with empirical evidence showing that inclusive environments strengthen belonging, trust and social connection, particularly among historically under-represented groups (Koper et al., 2024; Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024). For analytical clarity, it is therefore necessary to distinguish between diversity (the presence of different social groups), accessibility (the material and organizational conditions enabling participation), and inclusivity, understood as participants’ subjective perception that diversity and accessibility translate into fair treatment and a welcoming event environment (O’Brien et al., 2022). Operationally, inclusivity refers to the perception that the event facilitates and celebrates equitable participation across gender, age, functional ability and sociocultural background through visible representation, accessible features, non-discriminatory norms and a safe event climate.

2.6. Integrating Inclusivity into Motivational Models for Sport Tourism Events

Classical motivational models in running events have traditionally focused on enjoyment, socialization, competition and, more recently, digital interaction, without explicitly incorporating participants’ perceptions of inclusion or inequality (Parra-Camacho et al., 2019; Stragier et al., 2018; Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024). However, research on inclusive and community-oriented sport practices shows that participants may also be motivated by the perception that events are fair, open and socially representative. Studies on alternative football tournaments, refugee sport programmes and diaspora events indicate that environments where diversity is visibly recognized and valued can shape engagement and identification with the event (Burdsey, 2008; Rich et al., 2015; Spaaij & Schaillée, 2020; Digennaro & Falese, 2023). Similarly, work on ethical sport campaigns, women’s sport events and community initiatives suggests that some participants are attracted to events that align personal goals with broader values such as equity, gender equality or support for disadvantaged groups (Timms, 2012; Whigham et al., 2021; Coombs & Yanity, 2025). These findings point to the relevance of conceptualizing inclusivity as a potential motivational driver that interacts with, but is not reducible to, traditional dimensions such as hedonism or socialization (Fullagar & Pavlidis, 2012; Deckman & McDonald, 2023).

Incorporating inclusivity into motivational models allows testing whether perceived fairness, accessibility and representativeness contribute incremental explanatory power and generate more nuanced participant profiles (Hammer & Podlog, 2016; Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024, 2026). Evidence from disability sport, sensory-inclusive venues and inclusive volunteering shows that both participants with and without disabilities value concrete inclusive practices, which can influence satisfaction and willingness to re-engage (Martin et al., 2025; Jobst & Kreinbucher-Bekerle, 2025; Jermaina et al., 2025). In line with research on event legacies and participant segmentation, this approach avoids assuming homogeneous motivational structures and instead recognizes differentiated sensitivities to equality and inclusion (Koper et al., 2024; O’Brien et al., 2022). Accordingly, the present study adopts a dual modelling strategy that first examines the classical motivational dimensions of hedonism, socialization, competition and digital interaction, and then tests an extended structure incorporating inclusivity as a fifth dimension, enabling assessment of its added explanatory value and its role in refining runner segmentation within a mass-participation sport tourism event.

3. Hypotheses

Research on motivation in running events consistently identifies four core dimensions: hedonism, competition, socialization, and digital socialization (Parra-Camacho et al., 2019; Stragier et al., 2018; Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024). These dimensions represent enjoyment, performance orientation, interpersonal interaction and virtual engagement, and form the basis of most existing motivational scales.

Recent studies, however, highlight that perceived inclusivity, understood as the sense that an event promotes equitable participation across gender, age and functional ability, may motivate participation in its own right (Koper et al., 2024; O’Brien et al., 2022). Yet classical instruments do not explicitly incorporate this construct.

Integrating inclusivity into motivational models may therefore (1) reveal whether it functions as a distinct psychological dimension, (2) improve the explanatory structure of motivations, and (3) generate new runner profiles when segmenting participants. Based on this framework, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H1.

The four classical motivations: hedonism, competition, socialization and digital socialization, will form four distinct factors in the baseline model.

H2.

Inclusivity will emerge as a separate and statistically distinct motivational factor when incorporated into the model.

H3.

The five-factor model including inclusivity will show superior model fit and greater explained variance compared with the four-factor baseline model.

H4.

Including the inclusivity dimension will modify the runner segmentation, producing cluster solutions that differ from those obtained using only the four classical motivational dimensions.

4. Methodology

4.1. Survey Design

The data collection method selected was a self-administered questionnaire, a widely used approach in previous studies on sports tourism and participation in running events (Barrios-Duarte & Cardoso-Pérez, 2002; Parra-Camacho et al., 2019; Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024). The instrument design was based on consolidated motivation scales, as well as on subsequent adaptations and developments applied to mass participation races and other running contexts (Akbaş & Waśkiewicz, 2025; Avello-Viveros et al., 2022; Barrios-Duarte & Cardoso-Pérez, 2002; Crofts et al., 2012; Crossman et al., 2024; Guereño-Omil et al., 2024; Duclos-Bastías et al., 2021; Kazimierczak et al., 2020; Koper et al., 2024; Krippl & Ziemainz, 2010; Larumbe-Zabala et al., 2019; León-Guereño et al., 2020; Nikolaidis et al., 2019; Partyka & Waśkiewicz, 2024; Pereira et al., 2021; Ruiz-Juan & Zarauz-Sancho, 2011), as well as specific contributions on motivations for participating in sporting events were also considered, including those of Parra-Camacho et al. (2019), Malchrowicz-Mośko et al. (2020), and Ramos-Ruiz et al. (2024). Accordingly, an ad hoc questionnaire was developed to accurately capture the motivational dimensions identified in recent literature and adapt them to the specific context of the event (J. Hair et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2021).

The final instrument was structured into two main sections. The first included 22 items related to the five motivational dimensions analyzed: sport-related hedonism, socialization, competition, digital socialization, and inclusion (Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024). Following the methodological recommendations of J. Hair et al. (2020), a 7-point Likert scale was used because it offers greater sensitivity and precision than the 5-point format and provides an easily identifiable midpoint. In this case, a value of 1 corresponded to “strongly disagree,” 4 to “neither agree nor disagree,” and 7 to “strongly agree” (Koronios et al., 2018; Malchrowicz-Mośko et al., 2020). The second section consisted of categorical questions designed to collect information on the participants’ sociodemographic profiles, including variables such as gender, age, education level, occupation linked to physical activity and monthly income (León-Guereño et al., 2020; Qiu et al., 2020; Pereira et al., 2021; Thuany et al., 2021; Avello-Viveros et al., 2022). These variables are essential for establishing meaningful comparisons between groups and for analyzing potential motivational differences according to personal characteristics (Silva & Sobreiro, 2022; Partyka & Waśkiewicz, 2024).

Before final implementation, the questionnaire was reviewed by a panel of experts in sport management and active tourism to ensure content validity and item clarity (J. Hair et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2021). A pilot test was then conducted with a small group of local runners not included in the final sample, which confirmed the comprehensibility of the questions and optimized the total survey duration. This process also allowed refinement of the items related to inclusion and diversity motivations (Darcy et al., 2017; Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024). The purpose of these preliminary stages was to guarantee an efficient, easy-to-administer instrument aligned with the study’s objectives, minimizing respondent fatigue and enhancing data reliability (J. Hair et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2021). The final version of the questionnaire is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Questionnaire.

4.2. Data Collection

Data were collected following the celebration of the event on 23 March 2025. The organizing entity sent an email containing a link to the online questionnaire to the entire population of registered participants (N = 5550). The survey remained open from 24 March to 30 April 2025.

A total of 1053 valid questionnaires were obtained, resulting in a response rate of 18.97%. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and respondents were informed that they could withdraw from the survey at any time without consequence. This procedure ensured that all responses originated exclusively from officially registered runners and that the sample accurately reflected participants in the event.

4.3. Data Processing

Prior to the factorial and segmentation analyses, data quality and distributional assumptions were examined. Univariate outliers were identified using a combination of interquartile range (IQR) analysis and standardized z-scores. Specifically, values exceeding 1.5 times the interquartile range were inspected, and observations with absolute z-scores greater than 3.29 were considered extreme (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). Based on these criteria, two cases were identified as outliers and removed from subsequent analyses to prevent undue influence on the estimation of factorial and clustering solutions.

The normality of item distributions was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. As expected for Likert-type data collected in a large sample, the assumption of multivariate normality was not fully met. This result informed the choice of robust estimation methods in the confirmatory analyses.

Scale reliability was preliminarily examined using Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach, 1951) and McDonald’s omega. Following established psychometric guidelines, values equal to or above 0.70 were considered indicative of acceptable internal consistency (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994), while values above 0.95 were interpreted as suggestive of item redundancy and potential construct overlap (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011).

4.3.1. Factorial Validation and Model Comparison (H1–H3)

To address H1, H2 and H3, a psychometric procedure combining exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis was implemented to examine motivational dimensionality and to assess the incremental contribution of inclusivity. First, two exploratory factor analyses (EFA) were conducted using principal axis factoring, a recommended method for Likert-type data (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014). Sampling adequacy was examined through the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin index (KMO ≥ 0.70), considered acceptable for factor extraction (Kaiser, 1960), and through Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.05), which supports the presence of sufficient item intercorrelations (Everitt & Wykes, 2001).

Factor retention followed eigenvalues > 1 criterion (Kahn, 2006; Kaiser, 1960). Item retention criteria required factor loadings ≥ 0.40 and cross-loadings ≤ 0.30, in line with recommendations for structural clarity (Glutting et al., 2002). Total explained variance was expected to reach ≥ 50% for a satisfactory factorial solution (Merenda, 1997). Dimensional stability was assumed when at least 3 items loaded ≥ 0.50, reflecting the minimum condition for identifying an independent construct (Worthington & Whittaker, 2006). Internal consistency was initially assessed using Cronbach’s α ≥ 0.70 and omega ≥ 0.70 as an acceptable reliability threshold (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994), and lower than 0.95 (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011).

Subsequently, confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were estimated using robust maximum likelihood (MLR) due to the ordinal nature of indicators (T. A. Brown, 2015). Model fit was evaluated using CFI ≥ 0.90 (≥0.95 excellent) and TLI ≥ 0.90 (≥0.95 excellent) (Hu & Bentler, 1999), RMSEA ≤ 0.08 (≤0.06 optimal) as an indicator of parsimony (Steiger, 1990), and SRMR ≤ 0.08 as a residual-based metric (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Model comparison focused on increases in CFI and TLI, together with decreases in RMSEA and SRMR, following the logic of incremental fit improvement proposed in the structural modelling literature (T. A. Brown, 2015; Hu & Bentler, 1999; J. F. Hair et al., 2018; J. Hair et al., 2020).

This analytic sequence makes it possible to determine whether the four classical motivations form a differentiated structure (H1), whether inclusivity operates as an independent latent factor (H2), and whether the extended five-factor configuration improves model performance relative to the classical structure (H3).

4.3.2. Motivational Segmentation Through Cluster Analysis (H4)

H4 examined whether the inclusion dimension modifies the motivational segmentation of participants in the event. Standardized factor scores derived from the confirmatory models were used as clustering inputs, allowing the segmentation procedure to rely on latent motivational constructs rather than individual items.

A two-stage cluster procedure was implemented. First, Ward’s hierarchical method was applied to minimize within-group variance and to obtain an initial indication of the number of segments suitable for interpretation (Ward, 1963). The preliminary solution was determined through inspection of the agglomeration schedule and coefficient jumps (Ketchen & Shook, 1996). In a second stage, the initial cluster solution was refined using k-means, a non-hierarchical optimization algorithm that reallocates cases iteratively to maximize the homogeneity of the final partition (MacQueen, 1967). Cluster stability was checked by repeating the algorithm with alternative starting seeds, following recommendations for behavioural segmentation in tourism and consumer studies (Punj & Stewart, 1983).

To assess whether the motivational variables contributed meaningfully to cluster differentiation, the ANOVA table generated by SPSS v28.0 during the k-means estimation was inspected. This output provides F-statistics and p-values for between-cluster differences in each factor score, offering a descriptive indication of whether the motivational dimensions discriminate across market segments. Although not used as a strict inferential test, this procedure is widely applied in tourism segmentation studies as a practical indicator of variable relevance in cluster formation. The final interpretation of segment profiles will be based on differences in mean factor scores, behavioural coherence and substantive meaning for event management.

To examine the degree of correspondence between the segmentation solutions obtained from Model 1 and Model 2, Cramér’s V coefficient was computed based on a contingency table crossing cluster membership across models. Cramér’s V provides a measure of association strength between categorical classifications and is commonly applied to assess stability and reallocation patterns in segmentation research (Cramér, 1946; Everitt et al., 2011). This procedure enables an evaluation of whether the inclusion of a values-oriented construct such as inclusivity alters the structure of sport-tourism segments relative to a classical motivational model, as proposed in H4.

Additionally, associations between cluster membership and sociodemographic characteristics (gender, generational cohort, educational level, income and occupational characteristics) were analyzed using chi-square tests of independence. For each association, Pearson’s χ2 statistic and the corresponding p-value were reported to assess statistical significance, while Cramér’s V was used as an effect size measure to evaluate the substantive strength of the relationships (Cohen, 1985; Field, 2018). This approach allows the identification of sociodemographic attributes that meaningfully differentiate motivational segments without imposing predictive or causal assumptions on data-driven cluster solutions.

Table 2 provides a schematic overview of the methodological process, specifying the techniques, criteria, thresholds, and references used to test each hypothesis.

Table 2.

Methodological process.

5. Results

As shown in Table 3, the sample is predominantly composed of male participants (72.2%), non-residents (67.6%), and young to middle-aged adults, mainly belonging to Generation Y and Generation Z (85.3%). Most respondents report having completed university education (60.6%), hold occupations not directly related to physical activity (84.5%), and fall within middle-income brackets, with the majority earning between €2001 and €3000 per month (71.6%), outlining a typical participant profile of a young-adult, well-educated runner with moderate economic capacity.

Table 3.

Sociodemographic profile of the sample.

Table 4 reports the descriptive statistics for all motivational items. The highest mean scores correspond to items within the sport hedonism dimension, particularly Q01 (“Feeling pleasure from practicing this sport”, M = 6.67), Q03 (“Feeling proud of finishing the race”, M = 6.66) and Q04 (“The emotions this event generates for me”, M = 6.64). These items also show the lowest standard deviations (SD < 0.85) and pronounced negative skewness, indicating strong agreement and limited dispersion among respondents. Conversely, the lowest mean values are observed in items related to competitive achievement and digital interaction, notably Q11 (“Winning the competition”, M = 2.24), Q17 (“Wanting to receive ‘likes’ on the photos or videos I post”, M = 3.05), Q18 (“Wanting to interact on social media as a result of my participation in this event”, M = 3.31) and Q08 (“Wanting to perform better than other participants”, M = 3.48), with additional low scores in Q09 (“Competing with teammates from my athletics club”, M = 3.58) and Q16 (“Wanting to post photos or videos on my social media”, M = 3.74). These items exhibit higher standard deviations (SD > 2.0) and more symmetric or positively skewed distributions, reflecting greater heterogeneity in participant motivations. Overall, skewness and kurtosis patterns indicate ceiling effects in hedonic motivations and more dispersed response patterns in competition- and digitally oriented items, foreshadowing the differentiated motivational structures explored in subsequent analyses.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics.

5.1. Results for H1; Model 1: Four-Factor Motivational Structure, Not Considering Inclusion

The initial exploratory factor analysis included the full set of 22 items. However, after successive estimation runs and according to the predefined decision criteria (standardized loadings ≥ 0.50, absence of cross-loadings, AVE ≥ 0.50, and CR ≥ 0.70), five items were removed due to insufficient loading strength or limited contribution to convergent validity (Q05, Q06, Q09, Q11, and Q15). The final Model 1 solution consisted of 13 items grouped into four factors, corresponding to digital socialization, sport hedonism, socialization, and challenge.

The EFA showed appropriate factorability (KMO = 0.816), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 = 6483.753; df = 78; p < 0.001). All four retained factors exceeded the eigenvalue-greater-than-one criterion and jointly explained 70.90% of the total variance. Standardized factor loadings ranged between 0.676 and 0.915, and global internal consistency was satisfactory (α = 0.837; ω = 0.837).

The associated confirmatory model yielded acceptable fit indices (CFI = 0.944, TLI = 0.927, RMSEA = 0.076, SRMR = 0.052), values compatible with a four-factor solution and moderate residual error. Collectively, these results support the presence of a classical motivational structure, thus confirming H1.

5.2. Results for H2; Model 2: Five-Factor Motivational Structure, Considering Inclusion

In the second analysis, items operationalizing the Inclusion construct were reinstated, generating a new factorial solution composed of 17 items distributed across five factors. The dataset again exhibited adequate sampling adequacy (KMO = 0.867; Bartlett p < 0.001), and five eigenvalues exceeded 1. The new factor Inclusion, comprising four indicators (Q19, Q20, Q21, Q22), displayed standardized loadings between 0.787 and 0.881, an eigenvalue of 3.189, and accounted for 18.76% of the variance, fulfilling convergent validity requirements (AVE = 0.720; CR = 0.911).

Across the full instrument, the five-factor model explained 73.29% of total variance, exceeding the proportion accounted for by the classical structure. Coefficients of global reliability increased relative to Model 1 (α = 0.870; ω = 0.859).

The confirmatory factor analysis supported the adequacy of the expanded structure, yielding CFI = 0.956, TLI = 0.945, RMSEA = 0.067, and SRMR = 0.047, indicating a reduction in approximation error and superior incremental fit relative to the four-factor solution. These results satisfy H2 by demonstrating that Inclusion emerges as a statistically distinct and psychometrically valid motivational dimension.

5.3. Results for H3; Incremental Comparison Between Models

Comparative analysis (Table 5) revealed a systematic improvement once the Inclusion construct was incorporated. The five-factor model explained a higher proportion of total variance (73.29% vs. 70.90%), increased internal consistency (α = 0.870 vs. 0.837; ω = 0.859 vs. 0.837), and strengthened convergent validity for the new factor (AVE = 0.720; CR = 0.911).

Table 5.

Comparison of the motivational factor structure between the two models.

Regarding confirmatory fit, Model 2 reported superior indices (CFI = 0.956; TLI = 0.945) compared with Model 1 (CFI = 0.944; TLI = 0.927). Error indices also decreased (RMSEA from 0.076 to 0.067; SRMR from 0.052 to 0.047), indicating lower residual misfit.

Taken together, these parameters show that the five-factor model improves parsimony, explained variance, reliability, and overall fit relative to the classical solution, providing empirical support for H3.

5.4. Results for H4; Participant Clustering Using Both Models

In Model 1, based on the four classic dimensions (digital socialization, sporting hedonism, socialization and challenge), the ANOVA results (Table 6) showed statistically significant differences between the clusters in all the factors considered. These results indicate that the four dimensions contribute significantly to the differentiation of the profiles obtained in the four-cluster solution. Similarly, in Model 2, which incorporates the dimension of inclusion along with the four classic motivations, all variables showed statistically significant differences between the six clusters identified. These results confirm that the dimension of inclusion, together with the other motivational factors, has sufficient discriminatory power for the segmentation of participants in the expanded model.

Table 6.

Significance of the factors for segmentation in each model.

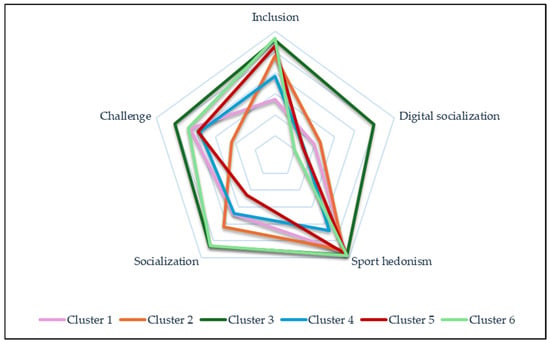

The segmentation solution obtained from Model 1 (Table 7, Figure 1), based on the four classic motivational dimensions (digital socialization, sporting hedonism, socialization and challenge), identified four distinct participant profiles. Cluster 1, called Individual Challenge Seekers (23.69% of the sample), is characterized by high levels of sporting hedonism and challenge, together with low values for socialization and digital socialization, reflecting an orientation towards individual experience and personal challenge. Cluster 2, identified as Digital Social Achievers (42.53%), has the highest scores in digital socialization, socialization, sporting hedonism and challenge, forming the profile with the greatest social, digital and sporting involvement within the classic model. Cluster 3, called Moderate Traditional Runners (17.89%), shows moderate values in all dimensions, with particular emphasis on low digital socialization and a balanced orientation towards enjoyment and challenge. Finally, Cluster 4, identified as Hedonic Recreational Runners (18.74%), combines high levels of sporting hedonism with low challenge values and moderate socialization, reflecting a predominantly recreational profile, focused on enjoying the event rather than competition.

Table 7.

Comparison of segmentation between the two models.

Figure 1.

Graphical comparison of clusters derived from Model 2.

The segmentation based on Model 2 (Table 7, Figure 1), which incorporates the dimension of inclusion alongside the four classic motivations, resulted in a more granular structure composed of six distinct clusters. Cluster 1, Individual Challenge Seekers (14.08%), maintains a profile similar to that observed in the classic model, with high levels of hedonism and challenge, low values of digital socialization and a moderate score for inclusion. Cluster 2, called Inclusive Social Hedonists (13.61%), is characterized by high levels of inclusion, sporting hedonism and socialization, together with a low level of challenge, forming a clearly social and recreational profile with an inclusive orientation. Cluster 3, identified as Digital Social Achievers (24.17%), has high values in all dimensions, especially inclusion, digital socialization, socialization and challenge, representing the profile with the highest overall involvement in the event. Cluster 4, called Moderately Inclusive All-Rounders (10.47%), shows moderate values in both inclusion and the other motivational dimensions, reflecting balanced participation without motivational extremes. Cluster 5, identified as Inclusive Individual Hedonists (15.89%), combines very high levels of inclusion and sporting hedonism with low values for socialization and digital socialization, together with a moderate level of challenge, suggesting an individual orientation towards enjoying the event from an inclusive perspective. Finally, Cluster 6, called Inclusive Social Competitors (21.79%), has the highest scores in inclusion, along with high levels of socialization, sporting hedonism and challenge, and low digital involvement, forming a social and competitive profile strongly oriented towards inclusive values.

Figure 1 provides a graphical comparison of the motivational structures of each cluster identified in Model 2, which incorporates inclusion as a motivational dimension.

Cramér’s V association test (Table 8) was performed to check the degree of association between Model 1 (4 motivation factors and 4 clusters) and Model 2 (5 motivation factors and 6 clusters). The results confirmed a statistically significant association between both segmentation solutions (Cramér’s V = 0.767; p < 0.001; N = 1051), which shows a strong, albeit imperfect, relationship between the classifications, consistent with the incremental validity of Model 2. Therefore, evidence has been found that some profiles show high stability between models, while others are redistributed when incorporating the inclusion dimension. In particular, Cluster 2 of Model 1 (Digital Social Achievers) is mainly concentrated in Cluster 3 of Model 2, indicating a clear continuity of this profile in both models. Similarly, a substantial part of Cluster 1 of Model 1 (Individual Challenge Seekers) remains in Cluster 1 of Model 2, while another relevant subset is reassigned to Cluster 5, reflecting an internal differentiation of this profile associated with inclusive orientation. For its part, Cluster 4 of Model 1 (Hedonic Recreational Runners) is mainly redistributed between Clusters 2 and 4 of Model 2, suggesting a more detailed segmentation of recreational profiles by expanding the motivational space. Finally, Cluster 3 of Model 1 (Moderate Traditional Runners) shows greater dispersion among several clusters of Model 2, evidencing less structural stability.

Table 8.

Case correspondence between clusters across models.

H4 is confirmed, as the inclusion of inclusivity as a motivational dimension increases the variance explained, improves confirmatory model fit, and also leads to a statistically significant redefinition of participant segments, yielding a more granular and substantively differentiated clustering solution than that obtained under the classical motivational framework.

Additionally, associations between cluster membership and sociodemographic characteristics were examined using chi-square tests of independence complemented by Cramér’s V as a measure of effect size. Results revealed statistically significant associations for gender (χ2(5) = 17.04, p = 0.004; V = 0.127), generational cohort (χ2(15) = 31.78, p = 0.007; V = 0.100), and educational level (χ2(5) = 56.89, p < 0.001; V = 0.233). While gender and generational cohort exhibited small effect sizes, educational attainment showed a small-to-moderate association, indicating a more substantive differentiation across clusters. In contrast, occupational physical demands were not significantly associated with cluster membership (χ2(5) = 8.79, p = 0.118; V = 0.091). Income level yielded a statistically significant chi-square result (χ2(30) = 45.25, p = 0.037); however, the effect size was negligible (V = 0.093), and a substantial proportion of expected cell frequencies fell below recommended thresholds, warranting cautious interpretation. Overall, these findings suggest that although certain sociodemographic variables introduce modest differences in cluster composition, the identified segments are primarily structured around motivational rather than demographic characteristics.

6. Discussion

The results confirm the multidimensional nature of motivation in running events and show that inclusivity can be empirically modelled as an independent motivational dimension alongside classical factors such as sport-related hedonism, competition, socialization and digital socialization. Rather than replacing traditional explanations of participation, the inclusion dimension operates as an additional layer that complements existing motivational frameworks, contributing incremental explanatory power to the overall model.

The incorporation of inclusivity increased the proportion of explained variance and led to a more differentiated segmentation of participants, suggesting that perceptions of equity, accessibility and representativeness are relevant for a subset of runners when interpreting their event experience. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that accessibility and perceived fairness can enhance satisfaction and identification with sport events, particularly in contexts where diversity and social responsibility are explicitly promoted (Darcy et al., 2017; Ramos-Ruiz et al., 2024). Importantly, the results do not imply that inclusivity is the dominant motivational driver across all participants, but rather that it meaningfully coexists with enjoyment-, challenge- and social-oriented motivations.

The cluster solutions further illustrate how inclusivity reshapes motivational profiles. In contrast to the four-cluster structure obtained under the classical model, the extended five-factor model yielded six segments that differentiated runners not only by performance orientation or social engagement, but also by their sensitivity to inclusive values. Clusters such as Inclusive Social Hedonists and Inclusive Social Competitors reflect hybrid profiles in which enjoyment, socialization and inclusion converge, while other segments remain primarily oriented towards individual challenge or recreational enjoyment with lower emphasis on inclusion. This pattern suggests that inclusion contributes to refining, rather than overturning, existing typologies of runners.

The interaction between inclusivity, sport-related hedonism and socialization indicates that inclusive perceptions may reinforce the emotional and communal aspects of the event experience for certain participants, supporting theoretical perspectives that emphasize belonging and relatedness as core psychological needs (Ryan & Deci, 2020). Compared with earlier studies of urban marathons in which competitive and hedonic motives predominated (Parra-Camacho et al., 2019; Nikolaidis et al., 2019), the present findings point to a gradual broadening of motivational logics, particularly in events that actively communicate inclusive values. At the same time, the persistence of the digital socialization dimension across both models confirms the relevance of online interaction in contemporary running cultures, even though its relative salience varies across clusters.

Overall, the discussion positions inclusivity as a meaningful motivational component that contributes to understanding how runners interpret the social meaning of their participation, without overstating its scope or generality. In this sense, inclusion should be understood as an incremental and context-dependent dimension within sport tourism motivation, particularly salient in events that visibly promote diversity and accessibility.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical Conclusions

This study provides evidence that perceived inclusivity can be conceptualized as a distinct and measurable motivational pull dimension within the framework of participation in running events, when defined in terms of equity, accessibility and representativeness. When incorporated alongside traditional dimensions, inclusion expands the explanatory scope of existing motivational models and contributes incremental value to their structural interpretation, rather than replacing or superseding classical drivers of participation.

The findings suggest that, although enjoyment, challenge and social interaction remain central to understanding participation in running events, a subset of participants also interprets their involvement through value-oriented lenses linked to fairness, accessibility and social responsibility. In this sense, participation is not explained exclusively by performance- or pleasure-based motives but may also be shaped by symbolic identification with events perceived as inclusive and socially representative.

From a theoretical standpoint, these results support a refinement of motivational theory in sport and sport tourism by recognizing inclusivity as a complementary and context-dependent motivational dimension. Rather than positioning inclusion as a dominant or universal driver, the present study shows that it functions as a higher-order construct that interacts with established motivations and helps capture heterogeneity in how participants relate to the social meaning of sporting events. This perspective contributes to ongoing theoretical efforts to integrate individual experiences with broader social values in the analysis of sport participation, while avoiding normative assumptions about the primacy of inclusivity across all participant groups.

7.2. Empirical Conclusions

The empirical results indicate that incorporating the inclusion dimension improves the performance of the motivational model by increasing the proportion of explained variance and enabling a more differentiated segmentation of participants. Compared with a classical motivation structure, the extended model yielded a more granular clustering solution and revealed motivational profiles that were not observable when inclusivity was excluded from the analysis. Specifically, the inclusion dimension contributed to distinguishing segments characterized by different combinations of enjoyment, social engagement and sensitivity to inclusive values. While some profiles maintained strong continuity across models, others were reconfigured when inclusivity was introduced, indicating that this dimension functions as a relevant discriminating factor for certain groups rather than as a universal driver of participation.

Overall, the findings show that considering inclusion in the empirical analysis of motivations enhances the explanatory precision and internal coherence of the model. Thus, inclusivity is not established as an indispensable component for all participants; the results demonstrate its capacity to refine the identification of motivational heterogeneity and to improve the representativeness of participant segmentation in mass running events.

7.3. Practical Implications

Based on the motivational structure and segmentation results, several practical implications can be derived. Each implication is presented as an identifiable managerial measure, followed by a brief explanation grounded in the empirical findings.

(a) Selective inclusivity design: Inclusivity should be implemented as a targeted design attribute rather than as a universal feature. The identification of clusters with high inclusion scores indicates that visible and concrete inclusive measures, such as accessible routes, adapted categories, and age-diverse participation, are particularly valued by specific segments while remaining neutral for performance- or challenge-oriented runners.

(b) Segment-sensitive communication strategies: The differentiated cluster structure supports the use of segmented communication. Inclusive and community-oriented messages may be emphasized in channels addressing socially engaged profiles, whereas challenge- and performance-focused narratives can be maintained for competitive segments, allowing motivational heterogeneity to be addressed without redefining the event’s overall positioning.

(c) Inclusivity as an internal differentiation lever: The partial stability and reconfiguration of clusters between models suggest that inclusivity primarily refines internal participant profiles rather than creating entirely new markets. Organizers may therefore use inclusivity to differentiate experiences within the existing participant base, for example, through symbolic recognition or tailored on-site experiences for inclusion-sensitive segments.

(d) Inclusion-oriented performance monitoring: Given its contribution to explained variance, inclusivity can be incorporated as an evaluative criterion in post-event assessments. Monitoring how different motivational profiles perceive inclusive practices allows organizers to assess whether these measures effectively reach the intended segments and to adjust strategies based on empirical feedback.

(e) Alignment between inclusive discourse and operational practice: The results underline the importance of coherence between communicated inclusive values and observable organizational practices. When inclusive discourse is not supported by tangible measures, its motivational impact is likely to be limited, whereas consistent implementation enhances perceived credibility and participant identification with the event.

7.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study is subject to limitations that should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings. First, the use of cross-sectional data could act as a bias. Future research could address this limitation through longitudinal designs that allow for examining the stability and evolution of motivational profiles across time, for example, by tracking runners across successive editions of the same event.

Second, the analysis is based on data from a single mass-participation running event. The motivational structure identified here may be influenced by event-specific, seasonal or contextual factors. Comparative studies across multiple events, destinations or calendar periods would therefore be valuable to assess the robustness and generalizability of the inclusion dimension.

Third, the reliance on a self-administered questionnaire introduces potential biases related to self-perception and social desirability, particularly when measuring value-laden constructs such as inclusivity. Future research could complement survey-based approaches with qualitative methods, including in-depth interviews or participant observation, to gain a more nuanced understanding of how inclusive practices are perceived and experienced by different runner profiles.

Future studies may expand on the present analytical framework by incorporating outcome variables such as satisfaction, loyalty or re-participation intentions, enabling a more direct assessment of the behavioural implications of inclusive motivation. In addition, alternative modelling approaches, such as partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM), may be employed to examine predictive relationships and mediation effects, while multilayer perceptron artificial neural networks (ANN) could be used to explore potential non-linear patterns and interaction effects among motivational dimensions and behavioural responses.

Finally, further case studies focusing on half marathons and other mass-participation sporting events in different cultural and institutional contexts are encouraged, as they would contribute to refining the proposed model and to clarifying the conditions under which inclusivity plays a more or less salient motivational role.

7.5. Main Contribution of This Research

The main contribution of this research lies in the empirical integration of inclusivity into a motivational model of running events, demonstrating its relevance as a distinct and measurable dimension that complements classical motivational drivers. Beyond confirming its psychometric validity, the study shows that incorporating inclusivity improves model performance and meaningfully reshapes participant segmentation, allowing for a more nuanced identification of motivational profiles. By combining factorial validation and segmentation analysis within a sport tourism context, this research advances the understanding of how value-oriented motivations interact with traditional drivers of participation, contributing to contemporary debates on diversity, sustainability, and socially responsible event management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.E.R.-R.; methodology, J.E.R.-R., J.M.C.-L. and D.A.-N.; validation, J.E.R.-R.; formal analysis, J.E.R.-R. and D.A.-N.; investigation, J.E.R.-R. and P.C.F.-G.; data curation, J.E.R.-R. and D.A.-N.; writing—original draft preparation, J.E.R.-R.; writing—review and editing, J.E.R.-R.; visualization, P.C.F.-G.; supervision, J.E.R.-R., P.C.F.-G. and J.M.C.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the code of responsible practices and integrity in research of the University of Córdoba.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akbaş, A., & Waśkiewicz, Z. (2025). From nonstarters through marathon to ultramarathon: A comparative analysis of models derived from a factor analysis of the Motivations of Marathoners Scales. Personality and Individual Differences, 240, 113153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algaba-Navarro, D., Orgaz-Agüera, F., Maldonado-López, B., & Ramos-Ruiz, J. E. (2024). Campeonatos de pádel amateur como recurso de turismo deportivo: Explorando la motivación de los participantes. In J. A. Marmolejo-Martín, & S. Moral-Cuadra (Eds.), Nuevas dimensiones de cambio en el panorama turístico actual. Melilla como destino emergente (pp. 494–504). Dykinson. ISBN 979-13-7006-081-7. [Google Scholar]

- Alsarve, D., & Johansson, E. (2022). A gang of ironworkers with the scent of blood: A participation observation of male dominance and its historical trajectories at Swedish semi-professional ice hockey events. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 57(1), 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avello-Viveros, C., Ulloa-Mendoza, R., Duran-Aguero, S., Carrasco-Castro, R., & Pizarro-Mena, R. (2022). Association between level of Physical Activity and Motivation in older people who practice running. Retos, 46, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuntamiento de Elche. (2022). La Media Maratón de Elche suma nuevas categorías para las personas con diversidad funcional. Available online: https://www.elche.es/2022/02/la-media-maraton-de-elche-suma-nuevas-categorias-para-las-personas-con-diversidad-funcional/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Azzali, S. (2019). Challenges and key factors in planning legacies of mega sporting events: Lessons learned from London, Sochi, and Rio de Janeiro. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research, 14(2), 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, K. (2023). Run like a mother: Running, race, and the shaping of motherhood under COVID-19. Feminist Media Studies, 23(6), 2546–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balish, S. M., Deaner, R. O., Rainham, D., & Blanchard, C. (2016). Sex differences in sport remain when accounting for countries’ gender inequality. Cross-Cultural Research, 50(5), 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios-Duarte, R., & Cardoso-Pérez, L. (2002). Motivación para competir en corredores populares cubanos. EFDeportes.com. Available online: https://www.efdeportes.com/efd47/motiv.htm (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Bartlett, M. S. (1951). The effect of standardization on a χ2 approximation in factor Analysis. Biometrika, 38(3/4), 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomé, A., Ramos, V., & Rey-Maquieira, J. (2009). Residents’ attitudes towards diversification sports tourism in the Balearics. Tourism Recreation Research, 34, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, T., & Dagkas, S. (2013). The Olympic Movement and Islamic culture: Conflict or compromise for Muslim women? International Journal of Sport Policy, 5, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. S., Masters, K. S., & Huebschmann, A. G. (2018). Identifying motives of midlife Black triathlete women using survey transformation to guide qualitative inquiry. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 33(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. D., O’Connor, J. P., & Barkatsas, A. N. (2009). Instrumentation and motivations for organised cycling: The development of the Cyclist Motivation Instrument (CMI). Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 8(3), 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Burdsey, D. (2008). Contested conceptions of identity, community and multiculturalism in the staging of alternative sport events: A case study of the Amsterdam World Cup football tournament. Leisure Studies, 27(3), 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Ortega, E. (2020). News coverage of women athletes during the Olympic Games. RICYDE, Revista Internacional de Ciencias del Deporte, 16, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier-Moisan, M. E. (2020). The dramatic losses of Brazil: City-staging, spectacular security, and the problem of sex tourism during the 2014 World Cup in Natal. City & Society, 32(3), 530–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaloupský, D., Chaloupská, P., & Hrusova, D. (2020). Use of fitness trackers in a blended learning model to personalize fitness running lessons. Interactive Learning Environments, 29, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, C. L., & De Castro, J. M. (1990). Running addiction: Measurement and associated psychological characteristics. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 30(3), 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F., Naylor, M., Li, Y., Dai, S., & Ju, P. (2021). Festival or sport? Chinese motivations to a modern urban hiking event. SAGE Open, 11(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Quinton, M., Alharbi, A., Bao, H. X., Bell, B., Carter, B., Duignan, M. B., Heyes, A., Kaplanidou, K., Karamani, M., Kennelly, J., Kokolakakis, T., Lee, M., Liang, X., Maharaj, B., Mair, J., Smith, A., Blerk, L. V., & Zanten, J. V. V. (2024). Propositions and recommendations for enhancing the legacies of major sporting events for disadvantaged communities and individuals. Event Management, 28(8), 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coche, R. (2017). How athletes frame themselves on social media: An analysis of Twitter profiles. Journal of Sports Media, 12(1), 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. P. (1985). The symbolic construction of community. Tavistock. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado Martínez, M., Robles Tascón, J. A., & Álvarez Del Palacio, E. (2021). Mujeres olimpicas en el descenso internacional del sella. Evolución de su participación. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte, 21(81), 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, D. S., & Yanity, M. (Eds.). (2025). Politics, social issues and the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, G. (2013). Mega sporting events in Brazil. Critical issues. Territorio, 64(1), 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 10(7), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couture, J. (2021). Reflections from the “Strava-sphere”: Kudos, community, and (self-)surveillance on a social network for athletes. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(4), 666–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramér, H. (1946). A contribution to the theory of statistical estimation. Scandinavian Actuarial Journal, 1946(1), 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crofts, C., Schofield, G., & Dickson, G. (2012). Women-only mass participation sporting events: Does participation facilitate changes in physical activity? Annals of Leisure Research, 15(2), 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossman, S., Drummond, M., Elliott, S., Kay, J., Montero, A., & Petersen, J. M. (2024). Facilitators and constraints to adult sport participation: A systematic review. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 72, 102609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Darcy, S., Lock, D., & Taylor, T. (2017). Enabling inclusive sport participation: Effects of disability and support needs on constraints to sport participation. Leisure Sciences, 39(1), 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L., Brown, A. E., & Hayes, C. J. (2025). Making the case for exploring accessibility and inclusion at live music events held in sports stadiums. Event Management, 29(4), 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckman, M., & McDonald, J. (2023). Uninspired by old white guys: The mobilizing factor of younger, more diverse candidates for Gen Z women. Politics and Gender, 19(1), 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Hoore, N., Helsen, K., & Scheerder, J. (2023). The elite breakaway sustains its lead on the peloton: Social leverage, major sport events, and cultural decolonisation. Leisure Studies, 42(6), 833–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digennaro, S., & Falese, L. (2023). Sport organisations’ contribution to migrants’ social inclusion in Italy: A sociological insight. Sport in Society, 26(11), 1820–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doidge, M., Keech, M., & Sandri, E. (2020). ‘Active integration’: Sport clubs taking an active role in the integration of refugees. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 12, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclos-Bastías, D., Vallejo-Reyes, F., Giakoni-Ramírez, F., & Parra-Camacho, D. (2021). Validation of the marathon motivation scale in Chile. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 16(2), 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, V. D. (2011). The dream of Delhi as a global city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35(3), 533–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybała, M. (2013). The Polish adaptation of the motives of runners for running questionnaire. Rozprawy Naukowe, 40, 118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Everitt, B. S., Landau, S., Leese, M., & Stahl, D. (2011). Cluster analysis (5th ed.). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B. S., & Wykes, T. (2001). Diccionario de estadística para psicólogos. Ariel. ISBN 84-344-0893-7. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. P. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Filo, K. R., Funk, D. C., & O’Brien, D. (2009). The meaning behind attachment: Exploring camaraderie, cause, and competency at a charity sport event. Journal of Sport Management, 23(3), 361–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filo, K. R., Funk, D. C., & O’Brien, D. (2011). Examining motivation for charity sport event participation: A comparison of recreation-based and charity-based motives. Journal of Leisure Research, 43(4), 491–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, T., & Maharaj, B. (2022). Mega-event trends and impacts. In A research agenda for event impacts (pp. 181–192). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullagar, S., & Pavlidis, A. (2012). “It’s all about the journey”: Women and cycling events. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 3(2), 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glutting, J. J., Monaghan, M. C., Adams, W., & Sheslow, D. (2002). Some psychometric properties of a system to measure ADHD among college students: Factor pattern, reliability, and one-year predictive validity. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 34(4), 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, R. J., Martínez-Rico, G., Bañuls-Lapuerta, F., & Calabuig, F. (2022). Residents’ perception of the impact of sports tourism on sustainable social development. Sustainability, 14(3), 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guereño-Omil, B., León-Guereño, P., Garro, E., Rozmiarek, M., Malchrowicz-Mośko, E., Młodzik, M., Włodarczyk, A., & Łuć, B. (2024). Motivations behind active sport tourists participating in natural and cultural landscapes. Sustainability, 16(18), 8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Page, M., & Brunsveld, N. (2020). Essentials of business research methods (4th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]