Abstract

This study aims to explain what drives consumers to adopt e-tipping in restaurants and determine whether interface-based manipulation reduces perceived autonomy, lowers satisfaction, and weakens brand favorability. Prior research indicates that when autonomy is undermined through manipulative design, satisfaction declines. This study integrates UTAUT2 and Self-Determination Theories to examine the determinants of consumers’ e-tipping intention, satisfaction, and brand favorability in Saudi restaurants. Four UTAUT2 motivators (performance expectancy, facilitating conditions, social influence, hedonic motivation) and service quality were modeled as antecedents, cultural attitude as mediator, and inferred manipulation as moderator. An online survey of restaurant consumers in Saudi Arabia who had previously engaged in e-tipping generated 607 valid responses, providing adequate sample power for PLS-SEM testing. Results show that performance expectancy, social influence, hedonic motivation, and service quality significantly predict intention; cultural attitude mediates several effects; and manipulation weakens the intention–satisfaction relationship, negatively impacting brand favorability. This research offers a theoretical contribution by extending UTAUT2 to the e-tipping context through integrating service quality as an antecedent and positioning satisfaction and brand favorability as core outcomes. It advances theory by demonstrating how technology-driven manipulation within payment interfaces influences cultural attitudes, behavioral intentions, and post-experience evaluations in a high-context, non-tipping society. Managerial and policy implications for responsible e-tipping designs are discussed.

1. Introduction

Tipping has been a long-studied service-related behavior, yet the rise of digital payments has transformed traditional practices, introducing new forms such as e-tipping that call for further academic exploration, especially in cross-cultural contexts (Chen et al., 2023; Warren & Hanson, 2023; Robledo, 2024). Previous research has predominantly focused on Western, low-context cultures where tipping is a social norm, while limited attention has been given to high-context societies (Wen et al., 2024). The world is experiencing a tremendous growth in the hospitality sector, where the global food service market reached 2.52 trillion U.S. dollars in 2021 and is expected to grow to 4 trillion by 2028 (Statista, 2025). Additionally, tips account for a significant portion of the U.S. economy, especially in restaurants, exceeding $47 billion annually (Azar, 2011). Tipping in restaurants was reported as the most popular practice among other service industries (Chen et al., 2023). Despite the hospitality sector’s and tipping practice’s growth, limited studies have examined e-tipping in non-tipping cultures.

Saudi Arabia, strategically positioned between three continents and classified as a high-context culture, is undergoing major technological and social changes under Vision 2030 (Saudi Vision 2030, 2025). Saudi Arabia has experienced rapid digital development and achieved a high global Information and Communications Technology (ICT) ranking (International Trade Administration, 2025). In this context, studying consumer acceptance of new technologies such as e-tipping becomes essential. Saudi Arabia provides a particularly rich setting for studying e-tipping because its cultural norms differ significantly from traditional tipping societies. As a collectivist culture, social behavior and decision-making are strongly influenced by group expectations and interpersonal approval (Hofstede, 2001). High-context communication patterns further imply that new practices, such as e-tipping, must gain cultural legitimacy before becoming normative (Hall, 1976). Unlike Western markets, where tipping is embedded in service norms, Saudi Arabia has limited historical tipping conventions (Lynn, 2015b). Yet at the same time, rapid adoption of mobile payments and fintech solutions is accelerating behavioral change (Alkhowaiter, 2022). This intersection of cultural norms and technological transformation makes Saudi Arabia an ideal empirical site for studying e-tipping. It allows examination of how motivations, attitudes, and satisfaction evolve in emerging non-tipping contexts.

This research applies the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT2) (Venkatesh et al., 2012) to examine the determinants of e-tipping intentions. It also integrates the Self-Determination Theories (Deci & Ryan, 2000) to assess psychological effects linked to autonomy and satisfaction. In e-tipping, satisfaction can stem from both the dining service and the e-tipping experience; customer satisfaction reflects the consumer’s overall affective evaluation of the dining and service encounter, whereas e-tip satisfaction captures their emotional response to the digital tipping interface at the payment moment, independent of the service experience. Modeling customer satisfaction and e-tip satisfaction as distinct constructs ensures conceptual clarity and acknowledges that these two evaluative judgments may not always converge. The concept of “inferred manipulation” defined as consumers’ perception of being nudged to tip through digital interfaces, is introduced in this study. The concept explains potential autonomy loss that may reduce e-tipping satisfaction and restaurant brand favorability (Alexander et al., 2021; Warren et al., 2021a; Jiao et al., 2022).

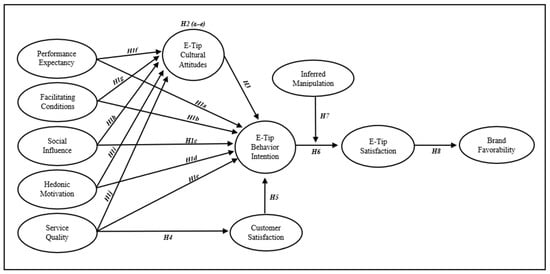

Prior tipping literature primarily examined motives such as service quality and social norms. However, no study has examined these motivations when tipping becomes technologically mediated. E-tipping introduces a new behavioral domain where technology acceptance factors intersect with tipping drivers. Although UTAUT has been widely applied across industries, including mobile and e-payments, no study has used UTAUT in restaurant service settings, nor integrated it with brand favorability as a core outcome. Moreover, no research has assessed m-payment adoption when payments are voluntary (tips) rather than transactional purchases. Given that tipping behavior is strongly shaped by culture and social norms, our study elevates attitude to a “cultural attitude” mediator. This is critically relevant in Saudi Arabia, where only limited research examined tipping behavior in high-context settings (Wen et al., 2024; Alsaati & Almeshal, 2024). Research on manipulation in e-tipping is recent and largely limited to default anchors in non-restaurant contexts (Chandar et al., 2019; Attari et al., 2025), with few studies examining how manipulation affects e-tipping satisfaction or brand favorability (Fan et al., 2024; Cabano & Attari, 2023). Therefore, this study addresses these gaps by integrating technology, cultural anthropology, and behavioral economics through the Electronic Tipping and Brand Favorability (ETBF) framework (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Electronic Tipping and Brand Favorability (ETBF).

The aim of this research is to examine how technology-related motivational factors and culturally rooted attitudes influence consumers’ intentions to engage in e-tipping in restaurant settings, and to test how inferred manipulation through default e-tip suggestions affects e-tip satisfaction and ultimately brand favorability. Accordingly, this study asks: What factors influence consumers’ intention to engage in e-tipping in Saudi restaurants, and how do cultural attitudes, customer satisfaction, and perceived manipulation influence this intention and its downstream effect on restaurant brand favorability? To address this overarching research question, the study draws on UTAUT2 and Self-Determination Theories to test how motivational, cultural, and psychological factors jointly influence e-tipping behavior and brand favorability outcomes in a high-context cultural environment.

1.1. Overview of Tipping and the Legal Environment

Research on tipping behavior has evolved over the past four decades, attracting scholars from psychology, economics, hospitality, marketing, and management disciplines (Furnham, 2021; Lynn & Brewster, 2020). Conceptually, tipping represents a voluntary payment, defined as a customer’s discretionary decision regarding whether, to whom, and how much to pay (Raghubir & Bluvstein, 2024). Economically, tipping remains a paradoxical phenomenon that continues to challenge rational choice theory (Lynn, 2022). As Lynn (2022) explains, individuals tip to attain social esteem, goodwill, or future service, while avoiding guilt or social disapproval—suggesting that tipping decisions are guided by self-interest, social reciprocity, and cultural expectations. Previous studies explored tipping motivations and show that people tip for multiple reasons; tipping is influenced by emotional, psychological, social, and fairness-related motives, including rewarding good service (Equity Theory), helping workers (Altruistic Act Theory), maintaining positive image (Impression Management), and remaining within social norms (Fernandez et al., 2024; Bluvstein Netter & Raghubir, 2021).

In Saudi Arabia, historical attempts to impose mandatory service charges (e.g., 15%) met consumer pushback and enforcement by the Ministry of Commerce (Aleqtisadeya, 2011, 2012; Alriyadh, 2011) culminating in a clear principle: bill totals must reflect menu prices; tips remain voluntary. Contemporary discussion highlights e-tipping prompts embedded in POS/checkout interfaces and the risk of perceived manipulation (e.g., Sabq, 2025). Current consumer-protection documents (Ministry of Municipal Rural Affairs and Housing, 2021; Ministry of Commerce, 2022, 2023) emphasize clarity, non-misleading pricing, and inclusion of all fees in stated prices, though they do not explicitly legislate digital tip defaults. This situates Saudi Arabia as a high-context, non-tipping-norm environment with clear price-transparency rules yet nascent governance over digital nudges—an ideal setting for the present study.

1.2. E-Tipping and Technology

Tipping has traditionally been a face-to-face, cash-based act occurring at the end of a dining encounter. With the rapid diffusion of digital payment ecosystems, tipping behavior has shifted to technology-mediated environments, giving rise to e-tipping. Through mobile wallets, QR codes, contactless cards, and POS terminals, tipping is now embedded directly inside the payment interface. This digital intermediation is reshaping the classical tipping encounter, and its continued diffusion is expected across diverse sectors, servicescapes, and cultures (Warren & Hanson, 2023; Pek, 2022). Findings comparing cash vs. e-tipping remain mixed: electronic formats can increase amounts through lower pain-of-paying, reduced salience, and freedom from cash constraints (Lynn & Latané, 1984; Fernandez et al., 2024), while others highlight concerns regarding trust, deservingness, and loss of human reciprocity (Dyussembayeva et al., 2022). Defaults can push e-tip levels upward (Alexander et al., 2021; Chandar et al., 2019) yet reduce e-tip satisfaction and repatronage (as a brand favorability outcome) when autonomy is threatened (Haggag & Paci, 2014). These mixed outcomes highlight a tension between technological convenience and perceived pressure, making it essential to understand how digital design interacts with cultural norms when shaping tipping behavior.

Understanding e-tipping now requires both service theory and technology acceptance theory. The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) and UTAUT2 (Venkatesh et al., 2003, 2012) remain the most widely validated models predicting behavioral intention in digital payment contexts and therefore provide a strong theoretical base for investigating e-tipping acceptance. UTAUT2 integrates functional beliefs (performance expectancy and facilitating conditions), social pressures (social influence), and affective drivers (hedonic motivation), offering heightened explanatory power in consumer digital environments. Performance Expectancy (PE) refers to the degree to which consumers believe that e-tipping enhances convenience, speed, or efficiency during the payment process. Facilitating Conditions (FC) capture the perceived availability of resources, device compatibility, and payment infrastructure that support e-tipping use. Social Influence (SI) reflects perceived expectations from peers, staff, or broader cultural norms, which is an especially relevant factor in collectivistic societies where conformity influences emerging behaviors. Hedonic Motivation (HM) denotes the enjoyment or positive affect consumers experience when interacting with seamless or aesthetically pleasing digital payment interfaces.

Service Quality (SQ) is incorporated as an additional antecedent because, in restaurant settings, judgments about the fairness, professionalism, and overall service encounter remain central to tipping behavior, even when the tipping act becomes digitally mediated. As defined by Lewis and Booms (1983), service quality represents the extent to which the delivered service meets or exceeds customer expectations, and confirmation-disconfirmation mechanisms consistently influence customer satisfaction outcomes (Parasuraman et al., 1988). Empirical evidence further demonstrates that higher perceived service quality is positively associated with tipping likelihood and larger tip amounts (Cabano & Attari, 2023; Lynn & Sturman, 2010).

UTAUT2 has been widely extended in mobile payment research (Alkhowaiter, 2022; Patil et al., 2020) and therefore provides an appropriate theoretical foundation to examine consumers’ motives, intentions, and cultural attitudes toward e-tipping within Saudi Arabian restaurant services. Accordingly, the study advances the following hypotheses:

H1a.

Performance Expectancy (PE) positively influences E-Tip Behavior Intention (BI).

H1b.

Facilitating Conditions (FC) positively influence E-Tip Behavior Intention (BI).

H1c.

Social Influence (SI) positively influences E-Tip Behavior Intention (BI).

H1d.

Hedonic Motivation (HM) positively influences E-Tip Behavior Intention (BI).

H1e.

Service Quality (SQ) positively influences E-Tip Behavior Intention (BI).

Further, UTAUT2 logic suggests that motivational antecedents also influence attitudes toward emerging practices during early adoption phases (Dwivedi et al., 2019; Venkatesh et al., 2012). Because e-tipping in Saudi Arabia is still culturally emergent, understanding attitudinal formation is critical. Therefore, this study extends UTAUT2 by examining the effects of PE, FC, SI, HM, and SQ on e-tipping cultural attitudes (ATT).

H1f.

Performance Expectancy (PE) positively influences E-Tip Cultural Attitude (ATT).

H1g.

Facilitating Conditions (FC) positively influence E-Tip Cultural Attitude (ATT).

H1h.

Social Influence (SI) positively influences E-Tip Cultural Attitude (ATT).

H1i.

Hedonic Motivation (HM) positively influences E-Tip Cultural Attitude (ATT).

H1j.

Service Quality (SQ) positively influences E-Tip Cultural Attitude (ATT).

Unlike traditional tipping, which is driven primarily by social norms and interpersonal cues (Lynn, 2015b), e-tipping embeds the decision within a digital interface, making technology-related beliefs more salient. In Saudi Arabia’s emerging e-payment environment, perceptions of usefulness, ease, and social endorsement are critical for legitimizing voluntary digital behaviors. Thus, UTAUT2 constructs are expected to play a central role in shaping e-tipping intentions in this context.

1.3. E-Tip Cultural Attitudes

Attitude, defined as “the degree to which consumers have a positive or negative evaluation of a given behavior”, is a central determinant of behavioral intention in TPB (Ajzen, 1991) and a consistent predictor of technology adoption (Patil et al., 2020). In this study, cultural attitude represents not only individual evaluation of e-tipping but also broader societal norms, expectations, and meanings attached to tipping behavior within a high-context culture. Research demonstrates that cultural context plays a major role in shaping behavioral intentions. In collectivist societies, people often adjust their behavior based on social expectations and group norms (Hofstede, 2001). Similarly, in high-context cultures, new behaviors typically need cultural acceptance before becoming widely adopted (Hall, 1976). In Saudi Arabia, where social approval, interpersonal cues, and shared understandings influence how behaviors are judged, cultural attitude becomes especially important in shaping responses to new technologies (Lynn, 2015b; Alkhowaiter, 2022). Therefore, considering cultural framing is essential for understanding how consumers perceive e-tipping as both a technological and social practice. Thus, cultural attitude reflects consumers’ evaluative orientation toward e-tipping as a socially appropriate behavior, shaped by shared norms, expectations, and cultural meanings.

Dwivedi et al. (2019) demonstrated that incorporating attitude into UTAUT2 enhances explanatory power by approximately 7%, and similar mediating patterns were observed in e-payment and e-government studies (Alkhowaiter, 2022). In tipping contexts, psychological motives, social compliance, and moral duty drive tipping norms, while cultural context shapes expectations, motivations, and perceived appropriateness (Ferguson et al., 2017; Conlin et al., 2003). Tipping particularly prevails in cultures emphasizing social approval and status signaling (Lynn et al., 1993; Lynn, 2015b; Azar, 2007; Lynn & Brewster, 2020). Because technological behaviors in Saudi Arabia often require cultural legitimacy before becoming normative, attitude formation plays a disproportionately important role in early adoption settings. Therefore, in Saudi Arabia’s high-context, technology-embracing environment, this study positions cultural attitude as a mediating mechanism linking e-tipping motivations to behavioral intentions. Therefore, the study advances the following hypotheses:

E-Tip Cultural Attitude (ATT) Mediates the Relationship Between:

H2a.

Performance Expectancy (PE) and E-Tip Behavior Intention (BI).

H2b.

Facilitating Conditions (FC) and E-Tip Behavior Intention (BI).

H2c.

Social Influence (SI) and E-Tip Behavior Intention (BI).

H2d.

Hedonic Motivation (HM) and E-Tip Behavior Intention (BI).

H2e.

Service Quality (SQ) and E-Tip Behavior Intention (BI).

Beyond its mediating function, cultural attitude is expected to exert an independent direct influence on behavioral intention, as prior studies confirm that attitude strongly predicts consumer behavior (E. Newman, 2023). In high-context societies such as Saudi Arabia, attitudinal acceptance is typically required before new behaviors gain legitimacy, making attitude central to e-tipping adoption. Therefore, this study further tests the direct effect of cultural attitude on behavioral intention toward e-tipping:

H3.

E-Tip Cultural Attitude (ATT) positively influences E-Tip Behavior Intention (BI).

1.4. Customer Satisfaction and Behavioral Intention

Customer satisfaction is defined as “the extent to which a product’s perceived performance matches a buyer’s expectations” (Kotler & Armstrong, 2021) and reflects an affective evaluation of the experience (Cadotte et al., 1987). In voluntary payments such as tipping, satisfaction is a key emotional consequence of the act itself (Raghubir & Bluvstein, 2024). Service quality, defined as performance relative to expectations (Lewis & Booms, 1983), remains a primary antecedent of satisfaction, extensively supported in literature (Parasuraman et al., 1988; Zeithaml et al., 1996). According to the confirmation–disconfirmation paradigm, customer satisfaction results from the alignment—or misalignment—between expected and perceived service performance (Parasuraman et al., 1988). This relationship is extensively validated across decades of research (Zeithaml et al., 1996; Soeharso, 2024). Empirical studies further confirm that high service quality leads to increased customer satisfaction and loyalty (Srivastava & Sharma, 2013). Therefore, in the e-tipping context, customer satisfaction serves as an outcome of perceived service quality. Thus, the study hypothesizes:

H4.

Service Quality (SQ) positively influences Customer Satisfaction (CS).

In the restaurant context, service quality is still the primary basis on which customers form overall customer satisfaction judgments, but e-tipping adds a “last-touch” digital moment that can color the entire experience. In Saudi Arabia—where tipping is not historically institutionalized—the customer satisfaction is likely anchored more strongly in perceived fairness, professionalism, and respect during service delivery rather than in habitual tipping expectations. Therefore, higher perceived service quality should translate into higher customer satisfaction, providing a clear foundation for subsequent voluntary behaviors in the payment stage.

The link between customer satisfaction and tipping behavior is well-established, where tipping is frequently viewed as a post-service behavioral expression of customer satisfaction (Lynn & Brewster, 2020; Kwortnik et al., 2009). Satisfied customers are more likely to tip as a reciprocal response to positive service encounters (Lynn, 2015a; Becker et al., 2012; Fernandez et al., 2024). Equity Theory proposes that satisfied consumers reciprocate fairness (Adams, 1965), while Reciprocity Theory suggests positive experiences evoke prosocial responses (Whaley et al., 2019a). Self-Perception Theory also explains tipping as reinforcing a warm-glow effect (Alexander et al., 2021). Within UTAUT2 logic, satisfaction is a post-behavioral state that is expected to predict e-tipping intention and post-experience satisfaction (Cadotte et al., 1987; Dwivedi et al., 2011). In other words, customer satisfaction reflects the overall affective evaluation of the dining experience, whereas e-tip satisfaction captures consumers’ affective response to the digital tipping moment, independent of the service encounter. To ensure conceptual clarity, customer satisfaction and e-tip satisfaction are treated as distinct constructs, capturing evaluations of the service encounter and the digital tipping moment, respectively. Accordingly, the study hypothesizes:

H5.

Customer Satisfaction (CS) positively influences E-Tip Behavior Intention (BI).

H6.

E-Tip Behavior Intention (BI) positively influences E-Tip Satisfaction (ES).

Unlike traditional tipping, where intention and behavior are shaped largely by established norms and face-to-face reciprocity, e-tipping moves the decision into a technology-mediated interface where consumers must actively interpret the meaning and appropriateness of tipping. In a non-tipping setting such as Saudi Arabia, customer satisfaction with the dining experience can function as a stronger cue for whether tipping is warranted, thus shaping e-tip intention (CS → BI). Further, once consumers form an intention in a digital environment, their satisfaction with the tipping moment (ES) is influenced by how smoothly and respectfully that intention is executed through the interface (BI → ES), making the post-intention tipping experience a distinct evaluative episode rather than a routine extension of service.

1.5. Manipulation: Nudges, Defaults, and Autonomy

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) posits that autonomy, competence, and relatedness underpin intrinsic motivation, well-being, and satisfaction (Deci & Ryan, 1987, 2000). In e-tipping, inferred manipulation—perceived nudging or coercion via defaults, prompts, or social pressure—threatens autonomy and elicits reactance (Brehm, 1966; Dillard & Shen, 2005). Inferred manipulation therefore captures consumers’ perception that the digital interface is steering or pressuring them toward higher tips, reducing autonomy and emotional comfort during payment. While tip defaults can raise e-tip amounts (Haggag & Paci, 2014; Chandar et al., 2019; Alexander et al., 2021), they often reduce e-tip satisfaction and brand favorability outcomes (reuse intention, WOM, and ratings) when perceived as controlling (Warren et al., 2021a, 2021b; Fan et al., 2024; Jiao et al., 2022). Consumers sometimes even tip less or refuse entirely when confronted with high anchors (Haggag & Paci, 2014) or guilt-based pressure (Warren & Hanson, 2023). Behavioral economics explains these effects via nudging and choice architecture (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008) and anchoring (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974), where default magnitude, labels, and number of options influence fairness and deservingness judgments. Poor defaults trigger manipulation attributions (Campbell, 1995; Brown & Venkatesh, 2005), damaging e-tip satisfaction and brand favorability (Warren et al., 2021b). Social norms also influence responses to e-tipping: violating voluntariness can erode trust, generate negative affect, and harm brand evaluations (Alexander et al., 2021; Azar, 2007; Attari et al., 2025). In this study, inferred manipulation operates as a negative moderator, weakening the otherwise positive intention → e-tip satisfaction pathway.

H7.

E-Tip Inferred Manipulation (M) negatively moderates the relationship between E-Tip Behavior Intention (BI) and E-Tip Satisfaction (ES).

E-tipping differs from traditional tipping because influence attempts can be embedded directly in the payment screen (e.g., defaults, prompts, and pressured choice framing), making perceived control and autonomy central to the tipping experience. In Saudi Arabia, where tipping norms are still emerging, consumers may be especially sensitive to interface-based pressure because the act itself is less culturally “settled” and therefore more open to interpretation as optional versus imposed. As a result, even when consumers intend to tip, inferred manipulation can reduce emotional comfort during payment and weaken the translation of intention into a satisfying tipping experience, supporting the proposed negative moderation.

1.6. Brand Favorability

Brand favorability subsumes affective responses such as likability, repeat visit intention, recommendations (WOM), ratings, and loyalty (J. W. Newman & Werbel, 1973; McMullan, 2005; Bobalca et al., 2012). Brand favorability reflects consumers’ overall evaluative judgment of the restaurant, shaped not only by service encounters but also by fairness and comfort during payment interactions. In restaurants, tipping motivations relate to loyalty and long-term relationships (Whaley et al., 2019b). Satisfaction-profit logics suggest that satisfied customers sustain performance through repeat patronage and WOM. In digital contexts, e-satisfaction with payments fosters continuance and e-loyalty (Anderson & Srinivasan, 2003; Zhou, 2013; Al Amin et al., 2024). Additionally, brand perceptions are increasingly influenced by micro-experiences (such as tipping screens) that signal respect, autonomy, and customer-centricity. However, gratuity guidelines/high defaults can backfire—lowering tip amounts and brand favorability outcomes—particularly in self-checkout e-tipping (Cabano & Attari, 2023; Attari et al., 2025; Karabas et al., 2020; Warren & Hanson, 2023). Previous studies explored the negative effect tip request has on brand favorability, establishing an inverse relationship between the two, where consumer behavior will be affected in terms of their experience feedback, service provider ratings, word-of-mouth, repatronage and future recommendations to others (Warren et al., 2021b; Jiao et al., 2022). The mechanism is consistent with value perceptions (Varki & Colgate, 2001) and autonomy threats (reactance). Thus, satisfaction with the e-tipping moment becomes a critical affective cue that influences brand liking, willingness to return, and positive word-of-mouth. Aligning with the proposed outcome pathway, we posit satisfaction with e-tipping as a proximal driver of brand favorability:

H8.

E-Tip Satisfaction (ES) positively influences Brand Favorability (BF).

In digital service encounters, brand evaluations are shaped not only by core service performance but also by payment-stage micro-experiences that signal fairness, respect, and customer-centricity. Because the e-tipping interface is often the final interaction before the customer leaves, satisfaction with the e-tipping moment can become a salient affective cue that carries forward into broader judgments about the restaurant. This mechanism is likely amplified in Saudi Arabia’s emerging e-tipping environment, where consumers are still forming expectations about what tipping requests “mean,” making e-tip satisfaction an important pathway to brand favorability.

This study advances theory by explicitly integrating UTAUT2, Self-Determination Theory, service quality, and cultural attitude formation into a unified explanatory framework for e-tipping behavior. The theoretical contribution lies not merely in applying existing models to a new context, but in introducing new mechanisms and outcome pathways within a voluntary, digitally mediated payment setting. Specifically, the study extends UTAUT2 by positioning cultural attitude as a mediating mechanism linking technology-related motivations to behavioral intention in a high-context, non-tipping society. It further integrates Self-Determination Theory by modeling perceived manipulation as a moderating mechanism that explains how interface-based influence undermines autonomy and weakens e-tip satisfaction, a dimension not captured in traditional technology adoption models. Incorporating service quality introduces a service-embedded logic, acknowledging that e-tipping evaluations remain anchored in the dining experience even when technologically mediated. Finally, by positioning e-tip satisfaction as a proximal driver of brand favorability, the study extends prior tipping and payment research by linking digital payment experiences to downstream brand favorability outcomes. Together, these theoretical extensions move beyond contextual application and offer a novel, mechanism-driven explanation of e-tipping behavior. As such, these findings matter for theory by demonstrating how voluntary digital payments require models that jointly account for technology adoption, psychological autonomy, service evaluation, and cultural legitimacy. From a practical perspective, the results highlight the importance of designing e-tipping interfaces that respect consumer autonomy while aligning with service quality and cultural expectations to protect e-tip satisfaction and brand favorability.

1.7. Boundary Conditions and Mechanisms

The proposed mediating and moderating mechanisms are contingent on specific contextual and behavioral conditions. Cultural attitude is expected to operate as a partial mediator when technology-related motivations directly influence behavioral intention while simultaneously shaping social legitimacy in a non-tipping context. Full mediation is more likely in early adoption stages, where behavioral intentions rely heavily on attitudinal acceptance rather than habitual norms. Likewise, the moderating role of inferred manipulation depends on the intensity of interface-based influence. Nudging choice with high-intensity prompts (e-tip defaults) is more likely to undermine autonomy, triggering reactance and reducing e-tip satisfaction even when e-tipping intention is high. These boundary conditions clarify when and how mediation and moderation effects are expected to emerge within digitally mediated, voluntary payment environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study employs a quantitative research methodology grounded in a deductive research approach. Consistent with the aims of positivist inquiry, the research seeks to empirically examine relationships among defined variables through objective measurement and statistical analysis. Given the practical and ethical constraints associated with manipulating behavioral variables in experimental settings, a survey-based research design was selected as the most appropriate quantitative method. This design enables the systematic collection of standardized data from a non-probabilistic sample of consumers with prior e-tipping experience, supporting the testing of hypotheses and contextual inference within the Saudi restaurant domain. Therefore, SEM is used to test the proposed relationships, including mediating and moderating effects, and assess the validity and reliability of the measurement model. PLS-SEM was chosen over CB-SEM because the study emphasizes prediction, tests a complex framework with both a mediator and a moderator, and expands theory exploratorily in an emerging e-tipping context where behavioral mechanisms are still being established.

2.2. Data Collection Method and Sample

A non-probability convenience sampling technique was employed, excluding individuals with no prior e-tipping experience. The target population consisted of consumers in Saudi Arabia who had recently visited a restaurant and used e-tipping services, with ages 18 and above, and an inclusion criterion focused on participants with recent e-tipping experience. Data were collected through an online survey administered via Google Forms and distributed through social media platforms (e.g., WhatsApp, LinkedIn), email, and targeted outreach to ensure diversity. Ethical approval KSU-HE-25-1029 was granted from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) unit at King Saud University on 29 September 2025. To control for common method bias, the survey enforced full item response, assured participant anonymity, and applied full-collinearity VIF diagnostics, confirming that CMV inflation did not meaningfully distort model estimates. A final usable sample of 607 valid responses was obtained. This sample size exceeds the minimum recommendations for PLS-SEM, as larger samples improve model estimation accuracy and statistical power, and meet the requirements suggested by Hair et al. (2019) and Sekaran and Bougie (2016) for complex multi-construct models. Therefore, the achieved sample size is considered sufficient, adequate, and methodologically appropriate for structural model evaluation and hypothesis testing in this research.

2.3. Measures and Instrumentation

The instrument utilized for this study consists of a questionnaire designed to reflect multiple dimensions under question in this research. The survey began with a screening question confirming participants’ recent e-tipping experience. Respondents then identified the restaurant and evaluated service quality and customer satisfaction (Parasuraman et al., 1988; Zhou, 2013). Constructs from UTAUT2 (Venkatesh et al., 2012)—performance expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, and hedonic motivation—were adapted as e-tipping motivations, supplemented with items from prior studies and researcher-developed additions. Subsequent sections measured cultural attitude (Lynn, 2015a), inferred manipulation (Campbell & Kirmani, 2000), e-tipping satisfaction (Zhou, 2013), and brand favorability (Cabano & Attari, 2023; Bobalca et al., 2012). Scale items were adopted from multiple prior studies, with minor contextual modifications to reflect the e-tipping setting, and were further supplemented with validated items from previous research alongside researcher-developed measures. All items in the sections followed the 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree, to 5 = Strongly Agree. The full research instrument can be found in Supplementary S1.

To ensure linguistic and conceptual equivalence of the data collection instrument, a rigorous translation procedure was implemented following established cross-cultural research guidelines. Given that the target population comprised Arabic-speaking residents of Saudi Arabia, a backward translation method was employed to preserve the semantic integrity of all measurement items. A pilot study was subsequently conducted to assess the instrument’s clarity, reliability, and internal consistency, yielding Cronbach’s alpha coefficients above 0.70 for all constructs. To validate the measurement structure of the adapted multi-source scale, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted using Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) with Promax rotation; factor retention followed eigenvalues > 1 and scree-plot inspection, and items loading ≥ 0.50 were retained. Sampling adequacy and factorability were confirmed via the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin KMO, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (p < 0.05), and all detailed statistics are reported in Supplementary S2.

3. Results

3.1. Survey Response Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SMART PLS version 4.0.9.6 with the PLS-SEM approach. The study focused on consumers who engage in e-tipping in restaurants within the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Prior to analysis, the dataset underwent systematic screening, descriptive review, and checks for missing values and outliers to ensure validity and analytical robustness. Data quality was validated through screening for missing values, outlier detection using the ±3 SD rule and residual scatter plots, and multicollinearity diagnostics, ensuring a reliable foundation for PLS-SEM estimation. The forced-response setting in Google Forms ensured a dataset free of missing values, enhancing data quality and supporting reliable PLS-SEM analysis. This analysis has identified 57 data points as outliers. Considering their potential effect on the accuracy of results, these observations were discarded. Of the 1271 questionnaires collected, 607 usable responses were retained following removal of cases that failed the attention check in item (31). Only participants who confirmed prior e-tipping usage in Saudi restaurants were included, yielding a valid response rate of 47.8%. Initial descriptive statistics were produced using SPSS Version 26 to provide preliminary distributional insights regarding the main study variables associated with e-tipping motivations, consumer behavioral intentions, and brand favorability outcomes. Means and standard deviations are reported in Supplementary S3. Respondent demographic characteristics (gender, age, region, education, occupation, and income) were analyzed in SPSS and highlights; 57.2% females, 55.4% of age group 18–24 followed by 23.9% of age group 25–34, 71.5% with a Bachelor’s degree, 52.7% students followed by 34.6% employees, and 70% income between 0–9999 SR. Complete sample characteristics are summarized in Supplementary S4.

3.2. Assessment of Measurement Model

Measurement model evaluation was then conducted using SmartPLS. Items ATT4, ATT5, ATT6, CS1, CS2, M5, and M6 were removed due to low outer loadings (<0.708) (Hair et al., 2019). After item removal, 50 of the original 57 items remained, all exceeding the recommended loading threshold, and removals improved convergent validity (AVE > 0.50) and internal consistency reliability (CR and α > 0.70) without altering construct conceptual boundaries. This confirms robust indicator-level reliability and accurate reflection of the latent construct. Consolidated outer loadings are presented in Supplementary S5. Internal consistency reliability was confirmed, as all constructs exceeded the recommended Cronbach’s alpha and Composite Reliability threshold of 0.70 (Hair et al., 2019), and all AVE values were above 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), indicating convergent validity (Table 1). Discriminant validity was assessed using both the Fornell-Larcker criterion and the HTMT ratio. All Fornell-Larcker diagonal values exceeded cross-construct correlations (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), and all HTMT ratios fell below 0.90 (Henseler et al., 2014), confirming distinctiveness among latent variables (Supplementary S6a,b). Although ATT–BI, ES–BF, and SI–BI represented stronger conceptual associations, discriminant validity remained acceptable under both criteria, supporting the theoretical distinct separation of constructs. Model fit was also assessed via SRMR, which yielded a value of 0.050, indicating satisfactory fit and supporting the adequacy of the proposed model for subsequent structural testing and hypothesis evaluation (Henseler et al., 2014).

Table 1.

Reliability Scores and Convergent Validity (AVE) Scores.

3.3. Assessment of Structural Model

Following the establishment of acceptable measurement properties, the structural model was assessed to determine the explanatory power, significance of the hypothesized paths, and predictive validity of the proposed e-tipping model. Collinearity was first reviewed to ensure that the independent constructs did not create redundancy or biased estimates. All VIF values fell below the recommended upper bound of 5.00 (Hair et al., 2019), ranging from 1.000 to 4.813, indicating that multicollinearity is not an issue for this model. The predictor variables’ independence sufficiently reinforces the dependability of the assessed path coefficients, positively affecting the model’s structural relationships.

Direct path testing was performed using 5000 bootstrap resamples. Multiple direct effects were significant at p ≤ 0.05, confirming theoretical expectations that attitudinal, normative, experiential and contextual variables jointly determine e-tipping behavior within this emerging cultural space. Bootstrapping is a non-parametric resampling method that repeatedly draws samples from the dataset to estimate the stability of path coefficients and standard errors without assuming normality, making it well-suited to PLS-SEM analysis involving mediation and moderation effects.

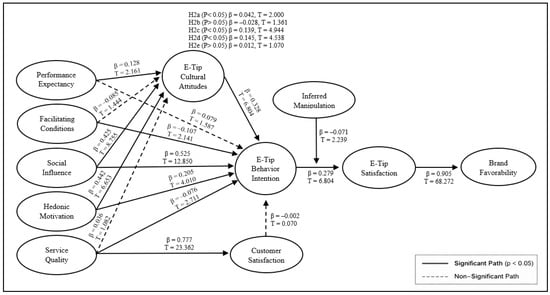

Social Influence (SI) had a strong, significant relationship with both Attitude toward E-tipping (ATT) (T-statistic = 8.755, p = 0.000) and Behavior Intention (BI) (T-statistic = 12.850, p = 0.000), reaffirming the dominant role of normative pressure in high-context cultures. Hedonic Motivation (HM) significantly predicted both ATT (T-statistic = 6.653, p = 0.000) and BI (T-statistic = 4.010, p = 0.000), demonstrating that enjoyment and experiential positivity act as powerful motivational triggers. Performance Expectancy (PE) positively influenced ATT (T-statistic = 2.161, p-value = 0.031) but did not significantly influence BI (T-statistic = 1.587, p-value = 0.113), indicating that usefulness influences cultural meaning but not behavioral likelihood directly. Facilitating Conditions (FC) significantly predicted BI (T-statistic = 2.141, p-value = 0.032) but not ATT (T-statistic = 1.444, p-value = 0.149), supporting the notion that infrastructure aids execution but not cultural positioning. Service Quality (SQ) demonstrated a significant direct effect on BI (T-statistic = 2.711, p-value = 0.007), as well as a very strong effect on Customer Satisfaction (CS) (T-statistic = 23.362, p-value = 0.000), but did not significantly influence ATT (T-statistic = 1.082, p-value = 0.279). ATT strongly predicted BI (T-statistic = 6.476, p = 0.000), BI predicted E-tip Satisfaction (ES) (T-statistic = 6.804, p-value = 0.000), and ES in turn strongly predicted Brand Favorability (BF) (T-statistic = 68.272, p-value = 0.000).

Mediation results show that ATT fully mediated PE → BI (T-statistic = 2.000; p = 0.046) and partially mediated SI → BI (T-statistic = 4.944, p = 0.000) and HM → BI (T-statistic = 4.538, p = 0.000), while no mediation was observed for FC → BI (T-statistic = 1.361, p = 0.174) and SQ → BI (T-statistic = 1.070, p = 0.285). This pattern confirms that the adoption of e-tipping is culturally filtered, where beliefs and enjoyment translate into intention primarily through the attitudinal layer. Moderation analysis using the two-stage approach confirmed a significant negative moderation effect of Inferred Manipulation (M) on the BI → ES link (T-statistic = 2.239, β = −0.071, p = 0.025). Thus, even when consumers intend to tip, e-tip satisfaction drops when the process feels coercive or manipulative, reinforcing ethical autonomy boundaries within e-tipping design. All results are demonstrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Direct Paths, Mediation and Moderation Coefficient Results.

The model demonstrated substantial explanatory power. R2 values achieved 0.819 for BF, 0.863 for BI, and improved for ES from 0.002 (without moderating variable) to 0.217 (with moderation), indicating that M meaningfully amplifies the model’s explanatory relevance for satisfaction. Effect sizes (f2) confirmed extremely large effects for ES → BF (4.521) and SQ → CS (1.521), and a large effect of SI → BI (0.645), with moderate contributions from M (0.275) and ATT (0.193), supporting the theoretical centrality of normative and experiential constructs. Predictive relevance (Q2) values indicated strong predictive capacity for BF (0.751), BI (0.736), and ATT (0.657), and moderate predictive relevance for ES (0.202). According to Hair et al. (2022), R2 values of 0.75, 0.50 and 0.25 represent substantial, moderate and weak explanatory power, respectively, while Cohen (1988) identifies f2 values of 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 as small, medium and large effect sizes. Additionally, Q2 values of 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 indicate small, medium and large predictive relevance (Chin, 2010). High R2 values were cross-checked with CMV diagnostics and predictive relevance (Q2), confirming strong explanatory and predictive power, while causal generalization is presented as a tentative interpretation to be validated in future longitudinal or experimental research. Table 3 summarizes the results of the hypothesis tests for this study. Of the 21 proposed hypotheses, the data supported 15, with 6 receiving no support. The relationship among the supported hypotheses demonstrates the presence of significant associations among the constructs. The empirical outcomes of all tested hypotheses, including the direction and significance of structural paths, are summarized visually in Figure 2. Overall, the structural model demonstrates strong predictive validity and theoretical coherence, confirming that e-tipping behavior in Saudi Arabia is primarily influenced by social influence, experiential enjoyment, cultural attitudes, and ethical perception of autonomy, more than traditional utility-based or satisfaction-based mechanisms.

Table 3.

Summary of Hypotheses Results.

Figure 2.

Visual Summary of Key Paths.

4. Discussion

Consumers’ behavioral intention to engage in e-tipping within the Saudi Arabian restaurant sector emerged as a multi-layered socio-technological, culturally moderated, and affect-driven decision rather than a purely utilitarian adoption response. The overall pattern of findings reinforces that the motivational architecture of e-tipping does not mirror the classic adoption psychology historically observed in most technology adoption domains. The non-significant direct impact of performance expectancy (T-statistic = 1.587, p-value = 0.113) on e-tipping behavioral intention represents one of the most theoretically consequential findings in this study. The results contradict the dominant UTAUT/UTAUT2 empirical tradition which consistently positions PE as a primary driver of behavioral intention (Venkatesh et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2010). The Saudi restaurant context appears to have reached a normalization stage where usefulness is no longer a discriminating construct. Consumers already assume digital payment systems will work as intended. The youth-dominant sample primarily reflects digitally fluent and fintech-active restaurant consumers in Saudi Arabia, strengthening the contextual relevance of the findings to real-world e-tipping behavior while maintaining appropriately tempered analytical inference.

In such an environment, the explanatory variance shifts away from rational utility. Instead, it centers on social influence, affective alignment, cultural legitimacy, hedonic gratification, and perceived autonomy. This reflects what Dwivedi et al. (2019) and Alalwan et al. (2017) call second-order digital embeddedness—when utility becomes invisible and emotional-normative factors begin to dominate over instrumental beliefs. This is reinforced by the fact that e-tipping involves extremely low task complexity, which prior research consistently finds reduces the salience of perceived usefulness (Ameen et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2020). Saudi consumers do not need to believe e-tipping “enhances performance” for them to consider doing it; it is cognitively effortless. Furthermore, e-tipping is not performed because it increases productivity; it is framed socially, relationally, symbolically, and emotionally rather than instrumentally. The construct therefore loses its predictive power. Yet, the same construct significantly predicted e-tip cultural attitude toward e-tipping (T-statistic = 2.161, p-value = 0.031). This duality reflects an important theoretical decoupling in the Saudi context: perceived usefulness can alter cultural meaning but does not directly alter behavioral willingness. This adds nuance to UTAUT2 and suggests that PE may increasingly function as an attitudinal rather than intentional lever in hyper-digitized markets. In environments where digital utility is already normalized, usefulness no longer operates as a behavioral driver, but still acts as a cognitive antecedent shaping cultural attitude schema—therefore influencing BI indirectly through cultural attitude rather than directly. As Zhao et al. (2010) emphasize, a mediator can fully transmit the effect even when the direct path is non-significant; a significant indirect effect in the absence of a direct effect is consistent with full mediation (Baron & Kenny, 1986).

By contrast, facilitating conditions strongly predicted behavioral intention (T-statistic = 2.141, p-value = 0.032) but did not significantly affect attitude (T-statistic = 1.444, p-value = 0.149). Saudi Arabia today is one of the most technologically advanced digital payment ecosystems globally. As a result, infrastructure is no longer a differentiating variable for consumers (International Telecommunication Union, 2023); rather, it has become a baseline expectation. In a mature digital environment, FC does not transform cultural values, but it does still reduce friction and increase behavioral likelihood. This aligns directly with Venkatesh et al. (2012), who conceptualized FC as a direct predictor of behavioral intention. Saudi consumers expect Apple Pay, STC Pay, seamless Near Field Communication (NFC) acceptance, and multi-option checkout. When present, it supports the actual enactment of behavior, but it does not meaningfully reshape cultural schemas around whether tipping itself “should” exist. This distinction between attitude and action layers in UTAUT-related constructs is theoretically valuable to future researchers working in digitally saturated markets.

Social influence emerged as one of the most dominant drivers in this study. It predicted both intention (T-statistic = 12.850, p-value = 0.000) and cultural attitude (T-statistic = 8.755, p-value = 0.000). This is a major confirmation of the high-context cultural argument (Hall, 1976; Hofstede, 2011). For e-tipping, Saudi consumers’ behavior is socially produced more than utility-produced. The normative pressure is not just peer pressure; it is symbolic alignment to modernity narratives, technology-forward self-presentation, and social compliance signaling. This explains why large global tipping research originating in U.S. settings (Lynn, 2015a; Lynn & Starbuck, 2015) cannot be directly transferred to the Saudi case. Here, tipping culture is being constructed socially—not inherited normatively from prior decades. E-tipping is also likely perceived as identity forward, status signaling, and value expressive—especially for younger consumers. In this sense, SI acts as a cultural diffusion mechanism for a non-native tipping norm.

Hedonic motivation also significantly predicted behavioral intention (T-statistic = 4.010, p-value = 0.000) and significantly predicted cultural attitude (T-statistic = 6.653, p-value = 0.000). This reinforces that in emerging, voluntary, and non-obligatory behavioral domains—pleasure, novelty, enjoyment, gamification, and digital experience aesthetic matter more than performance utility (Leong et al., 2013; Venkatesh et al., 2012). This is strongly aligned with the framing of digital consumption as hybrid emotional-function experiential layering. The act of e-tipping becomes part of the dining experience narrative rather than a post-service financial calculation. Service quality significantly predicted behavioral intention (T-statistic = 2.711, p-value = 0.007) and strongly predicted customer satisfaction (T-statistic = 23.362, p-value = 0.000) but surprisingly did not significantly influence cultural attitude (T-statistic = 1.082, p-value = 0.279). Two interpretation layers emerge. First, the positive BI relationship is consistent with tipping theory (Lynn, 2015b; Parasuraman et al., 1988). When customers receive great service, they naturally feel more willing to reward it. However, service quality is just one moment in time, while cultural attitude develops slowly over the years. In Saudi Arabia, where tipping norms are still emerging and not historically rooted, one good service experience is not enough to change how people culturally view whether tipping is the “right” thing to do. Ferguson et al. (2017) and Lynn and Brewster (2020) argue that attitude formation toward tipping is far more collective and slow-moving than episodic satisfaction evaluation. This decoupling reinforces that the Saudi tipping cultural system is still in formation, and therefore service quality is insufficient to institutionalize tipping norms.

Customer satisfaction did not significantly predict behavioral intention (T-statistic = 0.070, p-value = 0.944). This is a major theoretical contribution because it challenges the classical satisfaction–behavioral intention pipeline (Oliver, 1999) and also challenges Lynn’s (2015a) satisfaction-to-tipping logic. Younger consumers (55.4% aged 18–24 in this study) appear to operate on a different model. E-tip satisfaction influences brand favorability outcomes (patronage, WOM, return intention, brand attachment)—but not e-tipping intention. E-tipping intention in Saudi Arabia is a social compliance function, not a satisfaction response. E-tipping is experienced as a negotiation between fairness/deservingness (Gamble et al., 2025), moral role of hospitality labor, embarrassment avoidance, self-image maintenance, and technological suggestion cues rather than gratitude repayment. This point must be emphasized in future theory—e-tipping breaks the classical satisfaction pathway because the behavior is not pure gratitude behavior anymore. It is a social signaling behavior.

Behavior intention significantly predicted e-tipping satisfaction (T-statistic = 6.804, p-value = 0.000), supporting Expectancy Theory (Oliver, 1999). Consumers who intended to tip and actually engaged reported higher satisfaction because the enactment confirmed internal consistency and positive identity expression. Moreover, e-tipping satisfaction produced extremely strong brand favorability outcomes (T-statistic = 68.272, p-value = 0.000), which is one of the strongest effects in the entire model. This indicates that brand value is co-produced not only through food/service but also through the emotional end-of-journey digital exit experience. This demonstrates that e-tipping is not just an extra step; it is a brand touchpoint that emotionally seals the experience. E-tipping experiences that are frictionless, respectful, empowering, clear, transparent, and autonomy-preserving strengthen brand equity.

Cultural attitude toward e-tipping significantly predicted behavioral intention (T-statistic = 6.476, p-value = 0.000), confirming Ajzen (1991) and Venkatesh et al. (2012). This is crucial: cultural attitude is the largest psychological lever in this market. Without cultural alignment, consumers will not adopt e-tipping, even if the technology is easy and service quality is high. This suggests that future restaurant ecosystem strategies should focus on cultural meaning-making and not just UI design. In the Saudi context, the cultural meaning of e-tipping is socially constructed in real time, and this study demonstrates that behavioral adoption will not stabilize until cultural attitude stabilizes. Mediation results confirmed that ATT fully mediated PE → BI (H2a) and partially mediated SI → BI (H2c) and HM → BI (H2d), but did not mediate FC → BI (H2b) nor SQ → BI (H2e). This reinforces that e-tipping is a cultural meaning-based behavior, not a utilitarian functionality-based behavior. The cultural layer matters more than the infrastructural layer, and more than the episodic service encounter layer.

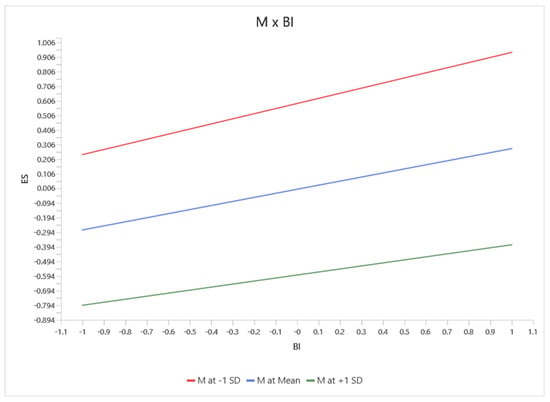

Finally, inferred manipulation negatively moderated BI → ES significantly (T-statistic = 2.239, β = −0.071, p-value = 0.025). This finding aligns with the dark tipping literature, which describes digital interface tactics that nudge or pressure consumers into leaving higher or unintended tips through defaults, framing, or restricted choices (Dyussembayeva et al., 2022; Lavoie et al., 2021; Attari et al., 2025). When inferred manipulation is high, the positive relationship between behavioral intention to engage in e-tipping and e-tip satisfaction weakens. Because e-tipping is a voluntary payment, perceived autonomy is essential; e-tip satisfaction arises when tipping is experienced as freely chosen but declines when interface-based nudging is perceived as coercive. Such pressure can trigger psychological reactance, reducing emotional comfort during the tipping moment and undermining e-tip satisfaction even when intention is present. Although the moderation effect (β = −0.071, p = 0.025) is statistically significant, the small effect size is reported transparently and contextualized visually through an interaction plot to support reader interpretation (Figure 3). The interaction plot indicates a statistically significant but small moderation effect, reflected in near-parallel slopes, reinforcing that inferred manipulation slightly attenuates the BI → ES relationship without materially altering its direction.

Figure 3.

Moderating Effect of M between BI and ES.

The findings both confirm and challenge existing theories in meaningful ways. UTAUT2 assumes performance expectancy as a primary intentional driver, yet the non-significant PE → BI path supports theoretical arguments of fintech normalization, where usefulness becomes cognitively assumed rather than consciously evaluated in digitally saturated markets. This aligns with high-context cultural communication theory (Hall, 1976), which emphasizes social legitimacy over instrumental reasoning for emerging behaviors. The strong SI and HM effects confirm cultural diffusion logic in such settings (Hofstede, 2001; Lynn, 2015a), while the moderation effect demonstrates that even small autonomy threats, as explained by SDT (Deci & Ryan, 1987, 2000), can activate consumer reactance when payments are voluntary rather than transactional. Finally, the absence of customer satisfaction-intention effects challenges classical tipping pipelines, confirming that in non-native tipping cultures, e-tipping intention operates more as a socially framed signaling behavior than a gratitude-driven satisfaction response. Collectively, this demonstrates that e-tipping must be theorized as a socio-technological and autonomy-sensitive behavior rather than a utility-based one. These interpretations are presented as context-based inference rather than confirmed temporal causality, given the study’s cross-sectional design. The observed patterns may suggest early signs of fintech normalization and autonomy sensitivity in voluntary e-tipping, consistent with UTAUT2’s normative–affective motivators and SDT’s autonomy-reactance logic. However, claims regarding behavioral stabilization or normalization stages should be considered tentative until validated through longitudinal or experimental research.

5. Conclusions

This study contributes to the emerging body of knowledge on e-tipping by extending traditional tipping theories to a digital and cultural context. While prior research has predominantly emphasized service quality and social norms, this study highlights the significance of technological determinants and elevates the construct from individual to cultural attitude within Saudi Arabia’s high-context, technology-driven environment. The findings underscore that digital manipulation—particularly through default tipping options—poses ethical and psychological challenges, diminishing consumer autonomy and satisfaction while negatively influencing restaurant brand favorability. By distinguishing between satisfaction with service and satisfaction with e-tipping under manipulative conditions, this research provides actionable insights for both scholars and practitioners, calling for the responsible design of digital payment systems and culturally sensitive policy interventions to protect consumer welfare.

5.1. Theoretical, Managerial and Policy Makers Implications

This study extends previous tipping research by examining the negative effects of inferred manipulation on e-tipping satisfaction and restaurant brand favorability (Attari et al., 2025; Cabano & Attari, 2023). It contributes to consumer behavior and service science by identifying determinants of e-tipping intentions and illustrating how low perceived control during electronic payment interactions reduces satisfaction (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Extending UTAUT2 (Venkatesh et al., 2012), the model integrates service quality as an independent variable and includes e-tip satisfaction and brand favorability as key outcomes. Addressing calls for further exploration of tipping across cultures (Lynn & Starbuck, 2015; Dyussembayeva et al., 2022), this research investigates e-tipping in a non-tipping, high-context society, providing insights into how digital technologies reshape cultural norms.

This study offers context-specific insights that may inform other high-context or non-tipping-norm societies, where digital payment interfaces mediate discretionary consumer choices (Hall, 1976; Hofstede, 2001). In emerging tipping environments, acceptance tends to rely more on social cues, interface fairness, and perceived autonomy than on inherited tipping norms (Lynn & Starbuck, 2015). The Saudi findings therefore provide conditional analytical inference relevant to similar cultural settings—such as Japan or Korea, where collective legitimacy shapes new digital behaviors, and to GCC markets including the UAE, where service encounters intersect with fast-growing fintech ecosystems and evolving gratuity expectations. Although broad generalization is not claimed, the study invites future cross-cultural and longitudinal validation to test whether autonomy-sensitive, interface-induced tipping evaluations similarly influence satisfaction and brand favorability in socially driven digital service contexts. Moreover, it highlights the need for continued study of evolving e-tipping systems and their psychological and behavioral implications in digital service contexts (Haggag & Paci, 2014; Whaley & Costen, 2019; Fan et al., 2025).

The findings of this study offer valuable insights for restaurant managers on implementing effective e-tipping practices and designing user-friendly digital payment systems. Managers should carefully construct choice architecture within e-payment platforms to minimize perceived manipulation and enhance e-tip satisfaction (Pek, 2022). They are encouraged to ensure that digital interfaces are transparent, non-intrusive, and culturally appropriate, especially in societies where tipping is not a traditional norm. Additionally, educating service employees to communicate tipping expectations clearly and respectfully can reduce customer discomfort and improve the service experience (Chen et al., 2023). Given the increasing role of consumer satisfaction as a major driver of organizational profitability, managers are encouraged to recognize how default e-tipping options, interface design, and perceived autonomy influence consumer emotions and brand favorability (Ogbonna & Harris, 2002). Furthermore, adopting customized point-of-sale (POS) designs—such as Qlub or Foodics in Saudi Arabia—can enhance hedonic experience and e-tip satisfaction. Managers should continuously monitor e-tipping practices, adapt them to local cultural norms, and align technological adoption with ethical and psychological considerations to preserve brand trust and long-term customer relationships (Whaley & Costen, 2019).

Given the non-experimental and non-probabilistic sampling design, the following implications are framed as conditional recommendations that align specifically with the empirical evidence observed in Saudi restaurant consumers. This study offers actionable policy implications aligned with the Saudi Vision 2030 digital transformation agenda (Saudi Vision 2030, 2025). As e-tipping adoption increases, there is a need to regulate predatory design practices that threaten consumer autonomy and well-being. The study recommends that the Ministry of Commerce, in collaboration with relevant authorities, establish regulatory guidelines governing e-tipping interface design—particularly default/stealth tipping features that obscure true choice. Public digital literacy campaigns should further inform consumers of their rights, supporting national directions that integrate behavioral economics into evidence-based policymaking (Ministry of Economy and Planning, 2023). Addressing dark patterns and unethical nudges within digital transactions will enhance consumer confidence, improve welfare, and protect citizens in future service automation ecosystems. Given the findings on the negative impact of default e-tipping on consumer autonomy, it is advised that the governing bodies, such as ministries, regulate manipulative tipping designs, promote transparency, and enhance consumer protection initiatives to preserve welfare and trust.

5.2. Limitations and Future Studies

This study advances understanding of e-tipping behavior and its impact on restaurant brand favorability; however, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the use of non-probability convenience sampling informs applied inference rather than population-level estimates. The cross-sectional design further restricts the ability to assess relationships or changes in behavior over time. Second, reliance on self-reported survey data introduces risks of recall bias, social desirability bias, and self-selection bias in reporting e-tipping attitudes and practices. Third, because this study was conducted in Saudi Arabia—where tipping norms are still emerging—findings may not directly translate to countries with firmly institutionalized tipping cultures. Finally, the study did not incorporate third-party transactional data, nor did it measure brand favorability behaviorally.

This study employs convenience sampling, a non-probabilistic approach that is widely used in applied hospitality and fintech research when the objective is to test prediction-oriented relationships rather than population estimates. To enhance conceptual clarity, all earlier phrasings implying sample representativeness have now been refined to accurately frame the findings as context-specific to Saudi restaurant consumers who have prior e-tipping experience. Given the strong sample size (n = 607), the data provides robust analytical power for PLS-SEM testing and theory expansion. Since the majority of respondents fall within the 18–24 age group, the results may particularly reflect higher digital fluency and familiarity with fintech interfaces, which should be considered when interpreting generalizability. The study therefore positions its contributions at the level of behavioral insight, contextual inference, and applied industry relevance, while encouraging future research to build on these findings using probability-based and age-comparative sampling designs. Given the cross-sectional, non-probabilistic design, the findings support analytical and contextual inference, but should not be interpreted as definitive evidence of causality or population-level representativeness. Accordingly, the results should not be used to claim that: (a) all Saudi consumers will behave similarly, (b) fintech normalization eliminates the role of usefulness over time, or (c) digital interface pressure will consistently reduce tipping satisfaction across all service settings.

Future research is encouraged to employ longitudinal or experimental designs to validate how e-tipping attitudes, intentions, and interface-induced satisfaction evolve among consumer cohorts in Saudi Arabia, where repeated exposure and digital payment touchpoints may shape brand favorability and loyalty in non-tipping-norm settings. Specifically, future studies could employ: (1) longitudinal tracking of attitude and tipping-screen perceptions across multiple tipping occasions, and (2) experimental A/B testing of tip-default levels, framing, and prompt styles within Saudi POS or checkout interfaces. Such designs would allow stronger validation of mediation (cultural attitude) and moderation (inferred manipulation intensity) effects using repeated behavioral exposure or controlled interface conditions.

Integrating survey data with objective transactional data from digital payment providers (such as Qlub or Foodics) would also improve construct validity and reduce self-report bias. Cross-cultural comparative studies are recommended to assess how cultural dimensions (e.g., collectivism, power distance) influence e-tipping norms. Future models should additionally incorporate economic and psychological drivers such as trust, fairness perceptions, digital payment literacy, and income sensitivity, to better explain consumers’ willingness to engage in e-tipping behaviors. As societies continue to evolve toward cashless economies and digitally augmented service experiences, e-tipping will remain a revealing lens through which to observe the intersection of culture, technology, and human values.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/tourhosp7010018/s1, Supplementary S1. Research Instrument. Supplementary S2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). Supplementary S3. Descriptive Statistics of the Study Variables. Supplementary S4. Respondents’ Profile. Supplementary S5. Outer Loadings. Supplementary S6a. Fornell-Larcker Criteria. Supplementary S6b. HTMT Score.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A. and M.S.; methodology, T.A. and M.S.; software, T.A.; validation, M.S. and T.A.; formal analysis, T.A.; investigation, T.A.; resources, T.A.; data curation, T.A.; writing—original draft preparation, T.A.; writing—review and editing, T.A. and M.S.; visualization, M.S. and T.A.; supervision, M.S.; project administration, T.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Technology and Innovation Unit at King Saud University (STU-KSU), Saudi Arabia, grant number “Grant No. STU-1”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board Unit of King Saud University (approval number: KSU-HE-25-1029, date: 29 September 2025).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author due to the research uses primary survey data, which is not publicly archived to protect respondent privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2, 267–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A. A., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Rana, N. P. (2017). Factors influencing adoption of mobile banking by Jordanian bank customers: Extending UTAUT2 with trust. International Journal of Information Management, 37, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amin, M., Muzareba, A. M., & Chowdhury, I. U. (2024). Understanding e-satisfaction, continuance intention, and e-loyalty toward mobile payment application during COVID-19: An investigation using the electronic technology continuance model. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 29, 318–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleqtisadeya. (2011). Available online: https://www.aleqt.com/2012/04/28/article_651572.html (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Aleqtisadeya. (2012). Available online: https://www.aleqt.com/2012/03/10/article_634782.html (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Alexander, D., Boone, C., & Lynn, M. (2021). The effects of tip recommendations on customer tipping, satisfaction, repatronage, and spending. Management Science, 67(1), 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhowaiter, W. (2022). Use and behavioural intention of m-payment in GCC countries: Extending meta-UTAUT with trust and Islamic religiosity. Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, 7(4), 100240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alriyadh. (2011). Available online: https://www.alriyadh.com/691987 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Alsaati, T., & Almeshal, S. (2024). Exploring service gratuity motivations from a cultural context aspect and the moderating role of gender. British Journal of Marketing Studies, 12(1), 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, N., Tarhini, A., Reppel, A., & Anand, A. (2021). Customer experiences in the age of artificial intelligence. Computers in Human Behavior, 114, 106548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R. E., & Srinivasan, S. S. (2003). E-satisfaction and e-loyalty: A contingency framework. Psychology and Marketing, 20, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attari, A., Cabano, F. G., & Minton, E. A. (2025). The negative effects of tipping suggestions from non-human agents: Consumer dislike of manipulative intent perceptions. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 59(1), e12615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, O. H. (2007). The social norm of tipping: A review. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37(2), 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, O. H. (2011). Business strategy and the social norm of tipping. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32(3), 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C., Bradley, G. T., & Zantow, K. (2012). The underlying dimensions of tipping behavior: An exploration, confirmation, and predictive model. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(1), 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluvstein Netter, S., & Raghubir, P. (2021). Tip to show off: Impression management motivations increase consumers’ generosity. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 6(1), 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobalca, C., Gatej (Bradu), C., & Ciobanu, O. (2012). Developing a scale to measure customer loyalty. Procedia Economics and Finance, 3, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, J. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance (social psychology). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. A., & Venkatesh, V. (2005). Model of adoption of technology in the household: A baseline model test and extension incorporating household life cycle. MIS Quarterly, 29(4), 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabano, F. G., & Attari, A. (2023). Don’t tell me how much to tip: The influence of gratuity guidelines on consumers’ favorability of the brand. Journal of Business Research, 159, 113754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadotte, E. R., Woodruff, R. B., & Jenkins, R. L. (1987). Expectations and norms in models of consumer satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 24, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M. C. (1995). When attention-getting advertising tactics elicit consumer inferences of manipulative intent: The importance of balancing benefits and investments. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 4(3), 225–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M. C., & Kirmani, A. (2000). Consumers’ use of persuasion knowledge: The effects of accessibility and cognitive capacity on perceptions of an influence agent. Journal of Consumer Research, 27(1), 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandar, B., Gneezy, U., List, J., & Muir, I. (2019). The drivers of social preferences: Evidence from a nationwide tipping field experiment. Natural field experiments 00680. The Field Experiments Website. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w26380/w26380.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Chen, J., Xu, A. J., Rodas, M. A., & Liu, X. (2023). Order matters: Rating service professionals first reduces tipping amount. Journal of Marketing, 87(1), 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In V. Esposito Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and application (pp. 645–689). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Conlin, M., Lynn, M., & O’Donoghue, T. (2003). The norm of restaurant tipping. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 52(3), 297–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(6), 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar]

- Dillard, J. P., & Shen, L. (2005). On the nature of reactance and its role in persuasive health communication. Communication Monographs, 72(2), 144–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., Chen, H., & Williams, M. (2011). A meta-analysis of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). In Governance and sustainability in information systems-managing the transfer and diffusion of IT, Proceedings of IFIP international working conference, Hamburg, Germany, September 22–24 (pp. 155–170). Springer. [Google Scholar]