Abstract

This study aims to assess the role of hotel departments in adapting to sustainable tourism indicators based on the resource conservation principle of Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory. Using the Best Worst Method (BWM) and Fuzzy TOPSIS, the findings reveal that waste management and reducing greenhouse gas emissions are top priorities. Results show that no single department dominates; instead, each contributes at varying levels. By applying COR theory at the departmental level in hotels, the study provides valuable insights into resource-efficient sustainability practices, offering a significant contribution to both academic literature and practical tourism management. The study offers managerial guidance on effective resource allocation, departmental collaboration, and policy integration to advance sustainability in hotels. It also emphasizes that cooperation among departments fosters social sustainability by enhancing awareness, accountability, and shared responsibility, contributing to long-term ecological and social goals in the hospitality sector.

1. Introduction

Sustainability is a concept that needs to be realized in all sectors and includes a whole set of guiding principles, strategies and goals as a necessity of human life (Choi & Sirakaya, 2006; Lee & Jan, 2019; Poudel et al., 2016). In this process, as part of a whole, how human beings can renew themselves, how multiple perspectives can be developed in common action, and how the education of the future will be shaped are important points to be emphasized. Therefore, the responsibility in the life cycle belongs to all countries of the world in every field. Common welfare is a central duty in the face of a developing global society and the relationships and issues associated with it. Social justice and common welfare should be recognized as the duty of all humanity, and development should be realized in a global context (Oesselman & Pfeifer-Schaupp, 2012). All development movements planned with the goal of sustainability should not be limited to one society, but should be implemented with a global joint decision. There is a need for an equitable and fair system that is carried out simultaneously in the development process to recycle resources, minimize waste, be socially and politically sustainable, and ensure human development (Mahadevia, 2001). At this point, the concept of sustainable development plays a leading role in meeting these needs.

The concept of sustainable development was first defined in the “Our Common Future” report prepared for the “World Commission on Environment and Development” in 1987 and became a term that started to be used frequently after the World Summit in 1992 (Adams, 2001). Global development until 2030 is set to be guided by 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), following their adoption and signature by 193 world leaders at the United Nations Summit in New York, 25–27 September 2015. Goals 8, 12 and 14 are linked to “Sustainable Tourism” and the benefits of tourism are important in achieving sustainable development goals (United Nations, 2015; UNWTO, 2020). Sustainable tourism indicators can be used to reveal these benefits. These indicators contribute to the fundamental principles of sustainable development and enable regular monitoring and improvement of tourism activities. According to Lee and Hsieh (2016), sustainable tourism indicators assist the tourism sector in weighing data and evaluating efficiency from the perspective of stakeholders.

It also determines strategies to protect the resources used in tourism activities in the long term. From this point of view, the present study is based on the conservation of resources theory (COR). COR theory is a psychological theory that explains individuals’ motivation to conserve available resources, use them efficiently, and increase their value (Hobfoll, 1989). The theory contributes to long-term resource management by managing employees’ decisions more qualitatively under limited resources (Guan et al., 2022). COR theory is a guide for measuring efficiency in sustainable practices of enterprises to achieve sustainable development goals. Within the theoretical framework, the aim of this study is to determine the role of departments in the process of hotels’ adaptation to sustainable tourism indicators. Another aim is to determine the level of sustainability practices of the departments and to reveal the differences with similar hotels.

As emphasized in the Total Quality Management approach, quality is the responsibility of employees at all levels of the organization. The success of sustainability efforts also depends on the internalization of sustainability practices by departments in hotel businesses in accordance with the principle. In this regard, this study is important as it highlights the role of departments. In the study, the food and beverage (D1), front office (D2), human resources (D3), marketing and sales (D4), housekeeping (D5), accounting (D6), and technical (D7) departments, which are commonly found in corporate five-star hotel businesses, were examined. Finally, this study provides significant practical implications regarding the efficiency-enhancing effects of sustainability certification when awarded to hotels, serving a complementary role in measuring sustainable practices. Additionally, it offers updated information on sustainable tourism practices in Türkiye, thereby contributing to practitioners and future research.

2. Literature Review

Sustainable tourism is a concept that aims to balance the economic, environmental and social aspects of tourism development (UNEP, 2005). The scope of this concept encompasses a tourism system predicated on ensuring the sustainable preservation of natural assets, the maintenance of socio-cultural life, and the sustained functionality of the economy for the benefit of upcoming generations (Maftuhah & Wirjodirdjo, 2018). The fundamental principles of sustainable tourism include minimizing negative impacts on the environment, promoting socio-cultural preservation, and supporting economic growth that benefits local communities (Angelevska-Najdeska & Rakicevik, 2012). Sustainable tourism indicators play a key role in determining the economic, socio-cultural and environmental impacts of tourism activities. The main indicators of sustainable tourism identified by UNWTO (2004) are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key issues and recommended indicators for sustainable tourism.

Sustainable tourism indicators can provide data on environmental aspects such as solid waste, greenhouse gas emission levels, water quality, the preservation of the current state of water, damage to forest areas, architectural pollution factors, renewable energy sources, and energy management. From a socio-cultural perspective, topics may include migration, accessibility of services for the local population, women’s employment, services for people with disabilities, preservation of cultural heritage, tourist satisfaction, and the welfare and satisfaction of local communities. Economically, data can be obtained regarding seasonality, quality employment, and local employment for residents. In this study, the indicators proposed by UNWTO (2004) were reassessed based on their relevance to the research questions and the characteristics of the study area within three main dimensions. Accordingly, the criteria to be used in the study were developed (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Criteria used in the study.

The reasons for the selection and the significance of the criteria presented in Table 2 are explained as follows:

C1: The level of measures taken to reduce energy consumption in the department.

Renewable energy is acknowledged as a critical factor in facilitating the achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) within the operational framework of the tourism sector (United Nations, 2015). Studies indicate that, as a sector, tourism may not be characterized by low energy consumption (Lu et al., 2019; Zhang & Liu, 2019). Pollution resulting from the use of fossil energy in tourism poses environmental challenges (Shan & Ren, 2023). In the long term, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and thereby lowering energy consumption are effective solutions for both environmental conservation and slowing global warming (Latief et al., 2024). In terms of these solutions, the use of renewable energy sources, which are a sustainable and environmentally friendly alternative, is quite important (Kalyani et al., 2015). Studies in the literature highlight the benefits of renewable energy use in tourism in terms of energy management (Wang & Wang, 2020), improving efficiency, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, controlling pollution, conserving natural resources, and supporting sustainable development (Shan & Ren, 2023; Azam et al., 2023; Suki et al., 2022). In the Sustainable Development Goals, increasing the global share of renewable energy is essential for Goal 7, which focuses on ensuring affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy access for all. From this perspective, expanding the use of renewable energy sources in the tourism sector can contribute to sustainable tourism practices (Silva, 2022). The escalation of renewable energy deployment within the tourism sector is positioned to significantly enhance the implementation of sustainable tourism practices (Silva, 2022).

C2: The level of measures taken to reduce water consumption in the department.

It is estimated that the global community could face a significant discrepancy between water supply and demand, potentially reaching a 40% gap within the next decade (World Economic Forum, 2023). In the tourism sector, the accommodation sector holds a significant place in terms of water consumption. Hotel businesses are facing water pollution, access to clean water, and most importantly, water scarcity. The water usage per guest in hotels is ten times higher than that of the local population (ITP, 2018). Tourist water footprint is also attributable to indirect consumption associated with operational activities such as daily room cleaning and laundry demand, as well as the water utilized for maintaining green spaces and supporting local food and electricity production (Dolnicar, 2022; Warnken et al., 2004). Both tourists and hotel employees should develop a sustainable awareness at this point. In order to develop sustainable awareness for the conservation of water resources in the tourism sector, water footprint analyses should be conducted based on both direct and indirect water consumption (WWF, 2014). By utilizing advanced technology, daily water consumption in accommodation businesses in the tourism sector can be monitored and controlled via computer systems, facilitating water savings. This not only provides ease of control but also helps prevent unnecessary water usage (Tosun & Özdemir, 2015). In the context of water and tourism, the political ecology approach influences water access and water equity in tourism centers (McCarroll et al., 2024).

C3: The level of attention given to topics such as “Reduce,” “Reuse,” and “Recycle” in the department.

The concept of sustainable tourism has gained increasing importance in recent years due to the need to balance economic growth, environmental protection, and social responsibility within the tourism sector. The 3R model (reduce, reuse, recycle) has become crucial for sustainable tourism development, primarily due to its alignment with the principles of the circular economy (European Commission, 2015). This approach, defined as maximizing the sustained value of resources while minimizing waste generation (L. Liu et al., 2017, p. 1315), holds a significant role in securing long-term tourism sustainability. In a study examining stakeholder dynamics in sustainable tourism management, it has been revealed that the 3R principles are closely aligned with the economic, social, and environmental pillars of sustainability (Padín, 2012). In the mentioned 3R model, the “reduce” approach minimizes the use of resources such as water, energy, and raw materials, providing significant cost savings for tourism businesses while also reducing their carbon footprint (Padín, 2012; Nedyalkova, 2016; Strippoli et al., 2024). The “reuse” approach in the model provides cost savings for businesses and tourists (Cvelbar et al., 2017). The reuse of materials, such as the reuse of hotel linens or furniture, reduces waste and promotes a more circular economy in the sector (Padín, 2012; Nedyalkova, 2016). Finally, within the model, the “recycle” approach contributes to a sustainable waste management system by facilitating the recycling of waste materials, including food scraps, packaging, and electronic devices (Agyeiwaah, 2019). In this regard, implementing comprehensive recycling programs, encouraging waste separation, and supporting initiatives that transform waste materials into valuable resources in the tourism sector are essential (Nedyalkova, 2016). The 3R model has an important place in sustainable tourism development in terms of improving processes in the tourism sector, promoting efficient use of resources and contributing to environmental sustainability.

C4: The level of eco-friendly material usage in the department.

One of the key points in the development of sustainable tourism is the use of eco-friendly products. Eco-friendly products significantly contribute to sustainable tourism development (Ayad et al., 2021; Diawati & Loupias, 2018). Using eco-friendly products conserves resources by reducing waste, promoting recycling, and minimizing the extraction of raw materials (Yuliani & Setyaningsih, 2024). Eco-friendly products are generally produced using fewer resources, which contributes to the conservation of natural resources (Diawati & Loupias, 2018). The use of eco-friendly products by hotels helps reduce their environmental footprint (Prakash & Sharma, 2023). In addition, hotels that prioritize environmental sustainability by using eco-friendly products are more likely to attract environmentally conscious consumers (Subbiah & Kannan, 2011). In the context of sustainability, the use of eco-friendly products provides benefits not only environmentally but also economically and socially (Al Falah & Sundram, 2023).

C5: The level of contribution made to local communities by the department.

Recent trends indicate an increasing commitment to realigning tourism practices to foster greater sustainability and ensure positive socio-economic outcomes for resident populations. In this context, it is seen that efforts to contribute to the sustainable development and welfare of local communities are emphasized (Lara-Morales & Clarke, 2024). The development of tourism-related businesses in a place provides direct and indirect contributions to the local communities in and around that region (Bohdanowicz & Zientara, 2009). Tourism businesses interact with many stakeholders such as local communities, administrations, and non-governmental organizations (Kurar, 2021). Accommodation businesses also have the potential to contribute to the socio-economic development of local communities by carrying out activities such as providing employment, carrying out community-oriented projects, and purchasing products from local communities for use in their businesses. However, weak inter-sectoral cooperation can hinder these contributions, as farmers may struggle to sell their products, and communities may face challenges in accessing capital resources and education (Mrema, 2015). Inadequate waste management by businesses (such as leftover food and entertainment waste), failure to maintain optimal levels of electricity and water consumption, and similar harmful activities not only damage the economic sustainability of these businesses but also negatively impact the quality of life of local communities (Çelik & Çevirgen, 2021). Nyikana and Sigxashe (2017) emphasize that the accommodation sector is an important factor in development for local communities, especially in rural areas facing unemployment issues. There are few studies examining the role of accommodation businesses in the development of local communities, which is one of the key elements in developing a sustainable tourism industry in a destination (Muganda et al., 2010).

C6: The status of training provided to department staff on local cultural heritage.

Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of Agenda 2030 has become a central global priority (Achille & Fiorillo, 2022). The development of educational programs, training of instructors, sharing of knowledge, and the development of heritage management plans are among the management issues related to the sustainability of cultural heritage (Jelinčić & Tišma, 2020). Cultural heritage education should be a lifelong process, not a periodic one. Therefore, the combination of education and cultural heritage represents flexibility, better learning, communication, and the development of project and research skills. For professionals and educators involved in cultural heritage education, it is necessary to create special training courses and research and update opportunities to renew interdisciplinary knowledge and update planning skills (Achille & Fiorillo, 2022). Additionally, activities related to local culture and history can be organized for tourism staff, providing education about the local cultural heritage and the history of buildings (Ng et al., 2023).

C7: The status of department staff encouraging guests to act respectfully toward the local culture.

One of the important criteria in ensuring sustainability in tourism is to respect the socio-cultural structure of the local residents, the cultural heritage and traditional values in the region and to protect the structures in the region (Yüksek et al., 2019). One of the important factors in tourists’ destination choices is the unique cultural experiences in the region. Therefore, it is very important to respect and protect these cultural assets in tourism activities. Sustainable tourism aims to minimize the negative impacts of tourism while contributing to the protection of tourism and the welfare of the host community (Baloch et al., 2023). Unlike traditional tourism, sustainable tourism offers an alternative approach that aims to benefit local residents, respect local cultures, and preserve natural resources (Grah et al., 2020). According to this approach, the negative impacts of visitors on traditional structures, cultural heritage and local people should be minimized (Girard & Nijkamp, 2009; Hong Van, 2020). In this context, visitors should be encouraged to be aware of social, cultural and environmental impacts and respect local culture and its functioning (Sahoo et al., 2020).

C8: The level of practices aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the department to contribute to the fight against climate change.

As stated in Sustainable Development Goal 13, the importance of taking action to address climate change and its impacts is based on the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (Zhao et al., 2024). Sustainable tourism practices play an important role in mitigating the impacts of climate change in the tourism sector. Doran et al. (2022); Mandić et al. (2024) emphasize the contribution of tourism to climate change and the need for sustainable tourism practices in their studies. Tourism is thought to be responsible for 8% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Lenzen et al., 2018) and 5% of CO2 emissions (Khan & Hou, 2021). Especially in reducing the impacts of climate change, carbon management is considered an important strategy (Gössling et al., 2023). Consequently, it is imperative that the hospitality sector implements comprehensive departmental strategies aimed at mitigating climate change via the substantial reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

A review of the literature reveals that previous studies have examined the sustainability practices of businesses in relation to employees (Jia et al., 2014; Guan et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2021; Koo et al., 2022), tourists (S. Liu et al., 2022; Cheng et al., 2024), and the tourism sector (Rashid et al., 2024); however, no studies have been found that address sustainability practices specifically within the framework of hotel departments. This represents an important gap in the literature. Moreover, this study introduces an innovative framework that promotes the continuity and sharing of resources among departments, extending the application of COR theory to enhance long-term efficiency in environmental, economic, and socio-cultural resource management.

In line with the aim of the study, answers were sought to four fundamental questions:

Q1. How are the importance levels of sustainable tourism criteria ranked within hotel businesses?

Q2. What is the level of implementation of sustainability practices in the departments of hotels with a Sustainable Tourism Certificate?

Q3. Which department stands out in sustainability practices?

Q4. Is there any similarity or difference in sustainability awareness among the departments of the hotels?

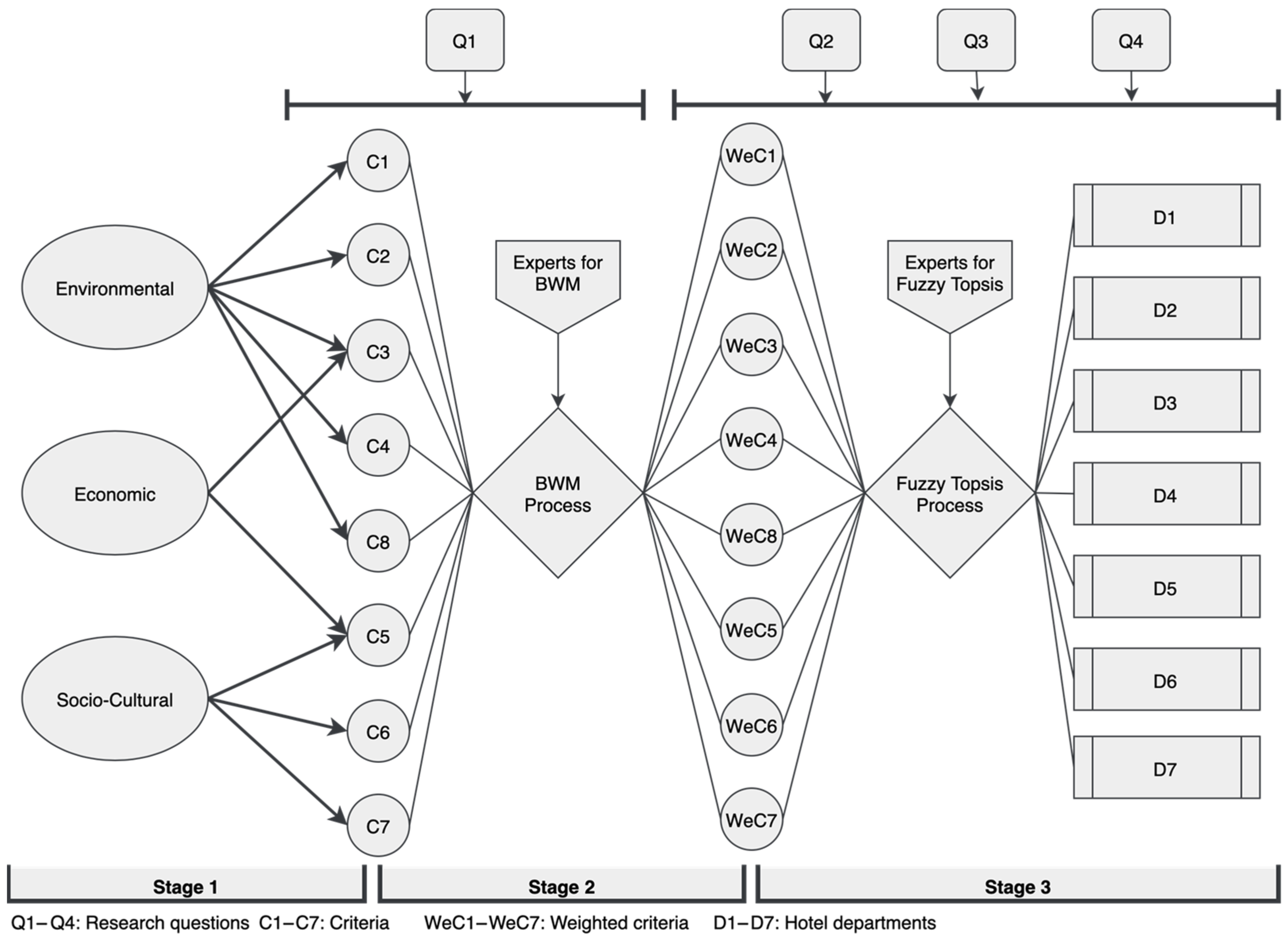

Figure 1 illustrates the main framework of the study. The research model was developed based on the methodological procedures outlined in the study conducted by Cicekdagi et al. (2023). According to the figure, the study consists of three main stages. In the first stage, sustainable tourism indicators categorized as environmental, economic, and socio-cultural were narrowed down to eight criteria through document analysis within the scope of the study’s objectives. In the second stage of the study, eight criteria were ranked according to their importance with BWM in order to answer Q1 of the research questions. In the third and final stage of the study, in order to answer Q2, Q3 and Q4, hotel managers who are authorized in sustainability studies were asked to score the sustainability study levels in seven different departments and the scores were analyzed with the Fuzzy TOPSIS method.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

The sample of this study consists of five-star hotels in Konya, Türkiye, that have sustainable tourism certification. The study consists of three main stages. In the first stage, criteria to be used in the study were obtained through a literature review. At this stage, eight criteria have been identified. In the second stage of the study, data obtained from academic experts in sustainable tourism were scored according to BWM, and the criteria weights were determined. In the third and final stage, general managers and assistant managers of the hotels scored the weighted criteria based on each department. The obtained data were used in the Fuzzy TOPSIS analysis to reveal the sustainable tourism implementation levels of the departments. A Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) technique that allows criteria to be ranked according to relative importance is the fuzzy TOPSIS method (Al Amin et al., 2023). The analysis results are presented with various tables and visuals.

3.2. Data Analysis

In the study, the BWM and Fuzzy TOPSIS method were utilized for data analysis. As a Multi-Criteria Decision-Making approach, the Best Worst Method (BWM) utilizes a structured pairwise comparison mechanism. It uses two comparison vectors in the optimization model: one from the best criterion to the others and another from the others to the worst. Consequently, this methodological approach possesses the capacity to ascertain the optimal weighting scheme for the specified criteria (Rezaei, 2020).

The TOPSIS method, an established procedure for ranking performance, was introduced by Hwang and Yoon (1981). In many fields, multi-criteria decision-making problems are encountered. Fuzzy TOPSIS is the most used technique to solve these problems (Nădăban et al., 2016; Sodhi & T.V, 2012). The methodology yields a solution by identifying the alternative that simultaneously minimizes the distance to the Positive Ideal Solution (PIS) and maximizes the distance from the Negative Ideal Solution (NIS) (Nădăban et al., 2016).

4. Results

BWM steps are listed as follows (Rezaei, 2015):

Step 1. Determine the criteria you will use in making decisions.

Step 2. Determine the criteria that are best (important) and worst (unimportant) for you.

Step 3. Indicate the level of relative preference by selecting an integer value from the 1–9 scale, where 1 signifies equal importance and 9 denotes the highest degree of importance. In this way, a vector that moves from the best to the others is reached. This vector, called Best-Others (AB), should be as follows:

Specifically, the value in this vector reflects the comparative superiority of criterion against the benchmark provided by the worst criterion, W.

= 1. This implies that a self-comparison procedure must be executed specifically for the worst-ranked criterion.

Step 5. Find the optimal weights for each criterion.

.

The core principle mandates that the optimal criterion weights, denoted by the vector must ideally satisfy the relationships . Therefore, the solution seeks to determine weights that minimize the maximum absolute deviation between the calculated ratio and the input preference values (i.e., , ). This objective is formally translated into the subsequent min-max model:

subject to

The resulting mathematical model is formally articulated as follows:

subject to:

The input data for the eight criteria (refer to Table 2), derived from the assessment of five experts, were calculated using the BWM Solvers Microsoft Excel add-in’s integrated Solver functionality.

The answers are given by 5 different decision-makers were analyzed and the criteria weights, final weights, Input-Based CR (IB), Associated Threshold (AT) and Reliability were given as seen in Table 3. If Input-Based CR (IB) < Associated Threshold (AT), it means ratios considered to be consistent. Based on this rule, all expert assessments appear to be consistent.

Table 3.

Criteria weights, final weights and reliability for each expert.

The findings related to the Q1 question sought in the research are shown in Table 3.

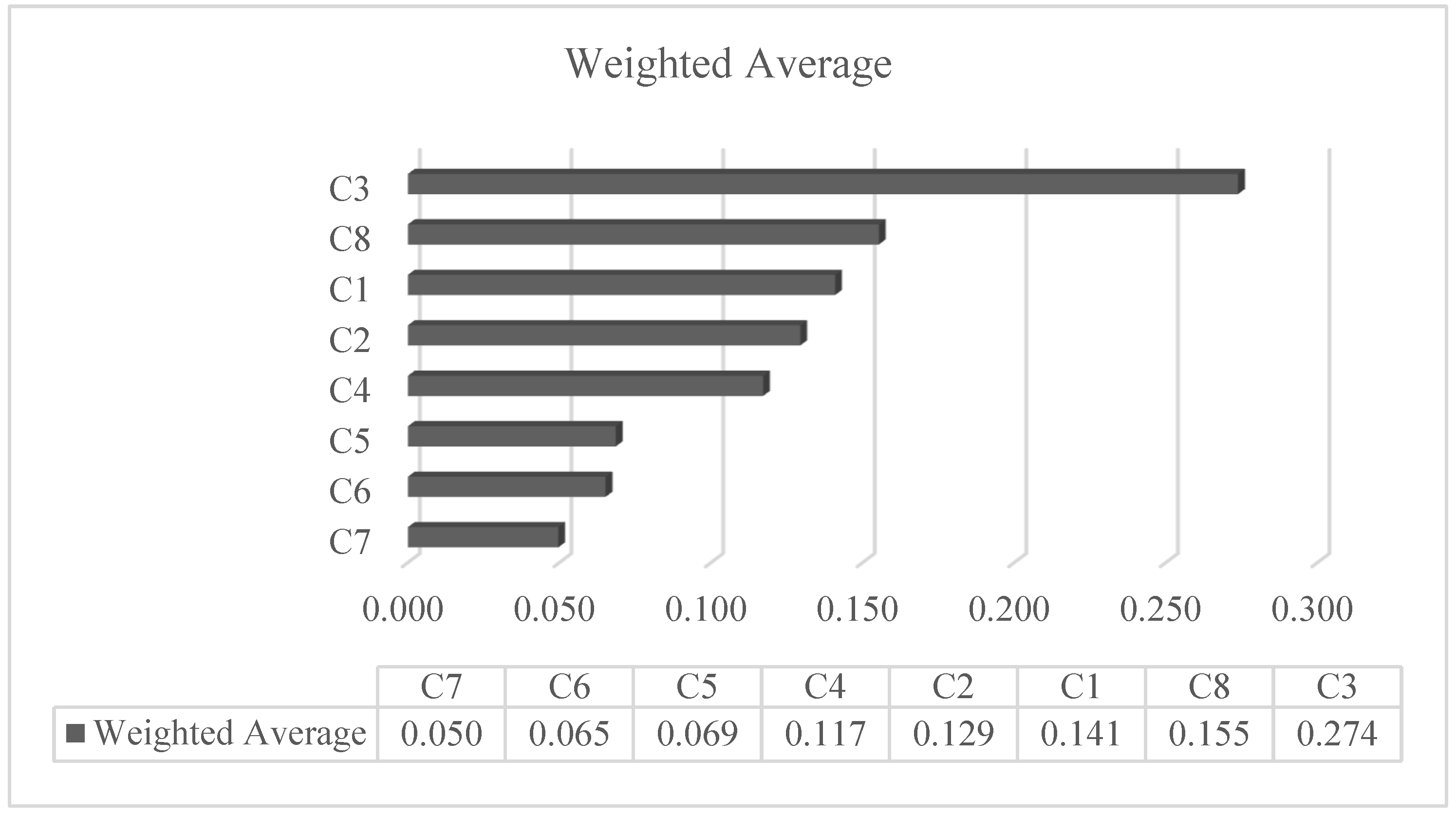

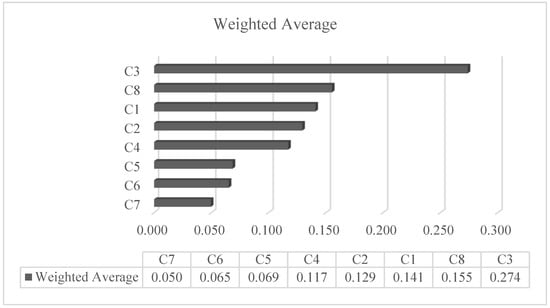

Considering the weighted averages of each criterion, the criteria are listed as C3, C8, C1, C2, C4, C5, C6 and C7 from the from most to least as seen in Figure 1. Accordingly, “C3-The level of attention paid to issues such as “Reduce”, “Reuse” and “Recycle” in the department” had the highest average, while “C7-The situation in which department staff encourage guests to behave respectfully towards local culture” had the lowest weighted average (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Weight distributions of criteria.

The fuzzy linguistic expressions related to the criteria are provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Fuzzy linguistic expressions for criteria.

Fuzzy linguistic expressions corresponding to the weighted average values of the criteria given in Figure 2 have been determined. Weighted average values have been classified in the range of “very high” to “moderately low.”

Fuzzy TOPSIS constitutes an established and widely employed MCDM technique for ranking alternatives in fuzzy environments, tracing its origins to the foundational work of Hwang and Yoon in 1981.

The Steps of the Fuzzy TOPSIS Method:

Step 1: Create a decision matrix.

In this study there are 8 criteria and 7 departments that are ranked based on FUZZY TOPSIS method. Linguistic expressions for Fuzzy TOPSIS are showed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Linguistic expressions for Fuzzy TOPSIS.

Table 6 summarizes the criterion type and the respective weight allocated to each element.

Table 6.

Characteristics of criteria.

The departments were evaluated according to various criteria and a decision matrix was created for each hotel.

Step 2: Create the normalized decision matrix.

Drawing upon the definition of the PIS and NIS, the normalization of the decision matrix is calculated via the following equation:

Step 3: Create the weighted normalized decision matrix.

The weight of each criterion in the normalized fuzzy decision matrix can be multiplied using the following formula to determine the weighted normalized decision matrix, taking into account the various weights assigned to each criterion.

where represents weight of criterion .

The following table shows the weighted normalized decision matrix.

Table 7.

Weighted normalized decision matrix for H1.

Table 8.

Weighted normalized decision matrix for H2.

Table 9.

Weighted normalized decision matrix for H3.

Table 10.

Weighted normalized decision matrix for H4.

Step 4: Determine the fuzzy positive ideal solution (FPIS, A*) and the fuzzy negative ideal solution (FNIS, A−).

The FPIS and FNIS of the alternatives can be defined as follows:

where is the max value of i for all the alternatives and is the min value of i for all the alternatives. B and C represent the positive and negative ideal solutions, respectively.

Step 5: Compute the distance metric (or separation measure) between every alternative and both the Fuzzy Positive Ideal Solution (A*) and the Fuzzy Negative Ideal Solution (A−).

The distance metrics from the FPIS and FNIS to every alternative are calculated according to the following formulas:

d is the distance between two fuzzy numbers; when given two triangular fuzzy numbers and , the distance between the two can be calculated as follows:

Note that and are crisp numbers.

The table below shows distance from positive and negative ideal solutions.

In Table 11, the results obtained following the procedures in Steps 4 and 5 are presented.

Table 11.

Distance from positive and negative ideal solutions.

Step 6: Compute the coefficient of closeness and utilize this metric to establish the final ranking of the departments.

The closeness coefficient of each department can be calculated as follows:

Given that the preferred alternative must be simultaneously closest to the FPIS and farthest from the FNIS, the Closeness Coefficient (CC) serves as the final ranking metric. The computed CC values for each alternative and the corresponding hierarchy are presented in the table below.

When Table 12 was evaluated in relation to the Q2 question sought in the research, the following results were obtained:

Table 12.

Closeness coefficient.

- In the H1 hotel, the levels of implementation of sustainable tourism by departments are as follows: Technical, Housekeeping, Human Resources, Front Office, Accounting, Food & Beverage, Marketing, and Sales.

- In the H2 hotel, the levels of implementation of sustainable tourism by departments are as follows: Front Office, Housekeeping, Food & Beverage, Human Resources, Technical, Front Office, Marketing and Sales, and Accounting.

- In the H3 hotel, the levels of implementation of sustainable tourism by departments are as follows: Food & Beverage, Housekeeping, Technical, Marketing and Sales, Human Resources, Front Office, and Accounting.

- In the H4 hotel, the levels of implementation of sustainable tourism by departments are as follows: Marketing and Sales, Food & Beverage, Front Office, Human Resources, Accounting, Housekeeping, and Technical.

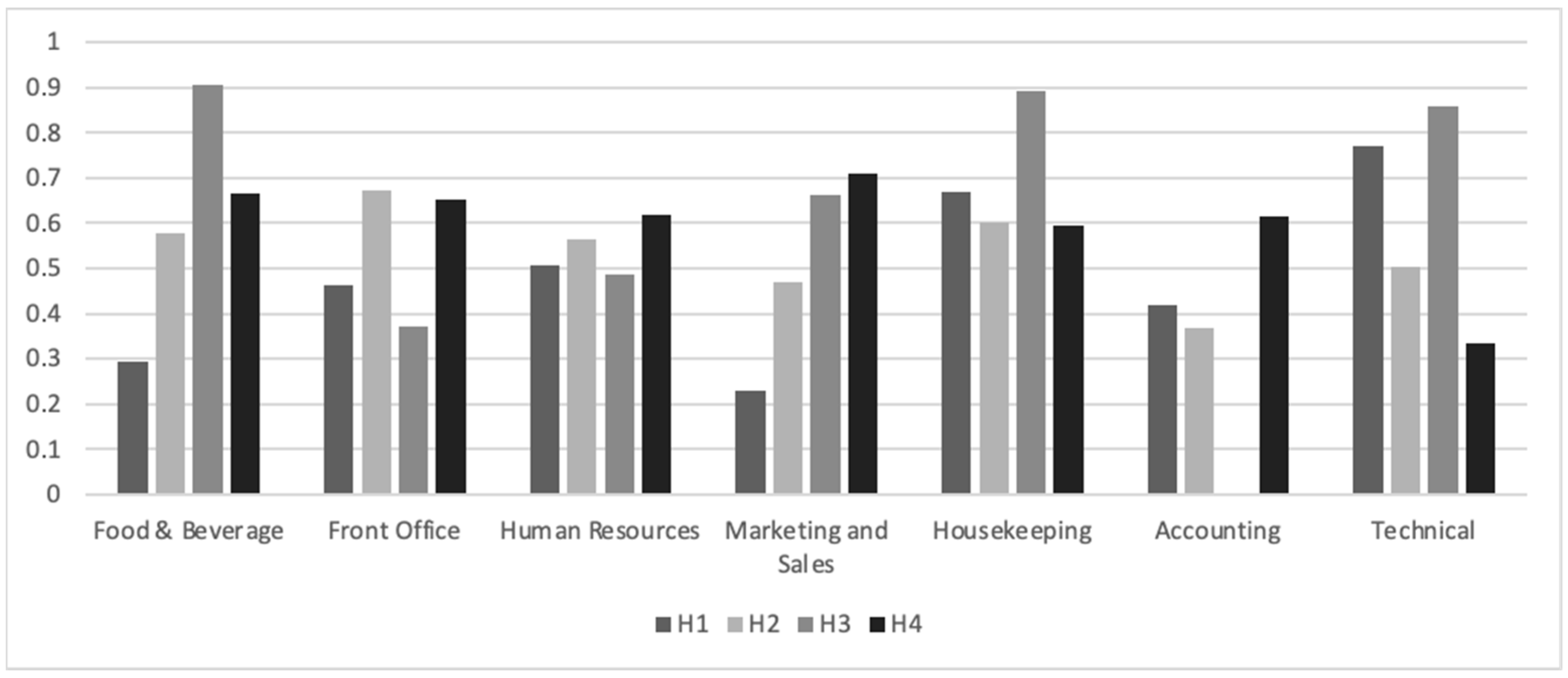

When evaluating Table 12 in response to the research question Q3, it is observed that the Technical in Hotel H1, Front Office in Hotel H2, Food & Beverage in Hotel H3, and Marketing and Sales in Hotel H4 rank first. Additionally, the housekeeping department ranks second in three hotels (H1, H2, H3). The position of the Food and Beverage department is also in the top two ranks in three hotels (H2, H3, H4). On the other hand, the Accounting Department consistently ranks among the lowest in all hotels (H1, H2, H3, H4).

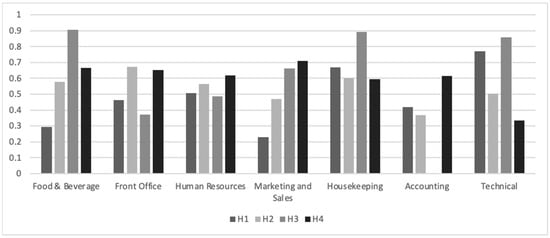

In the research, Figure 3 was examined to find an answer to question Q4.

Figure 3.

Closeness coefficient of each department.

Figure 3 shows the tendency of departments in four hotels to contribute to sustainable tourism. According to the figure, the contribution levels in the human resources department are close to each other, while the levels of sustainable tourism practices in other departments vary across the hotels.

5. Discussion

The study seeks to answer four research questions developed to examine sustainable tourism practices in hotels on a departmental basis. In this context, the results of evaluating the findings obtained in three stages are discussed in this section.

When evaluating the findings obtained using BWM to determine criteria weights, it was observed that experts rated criterion C3 (0.274) as the top priority by a significant margin. This situation supports the COR theory on which the study is based. According to the theory, the long-term conservation of resources is crucial for sustainability. In terms of long-term resource conservation, practices observed in the hotels included rainwater storage (using stored rainwater to irrigate hotel gardens) and heat recovery (capturing steam from heating fuel to reuse). These practices fall under the “Reduce,” “Reuse,” and “Recycle” framework. Although these practices are often perceived as an additional cost, the use of sustainable tourism practices that provide recycling, waste management, and energy conservation can contribute to long-term economic growth (Tosun et al., 2022).

The high score of practices aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions (C8: 0.155) in the department to combat climate change highlights the prominence of the environmental dimension, one of the three pillars of sustainability. It was observed that the hotels in the study also focus on practices to reduce greenhouse gases in support of this approach. These practices include purchasing from local suppliers, using electric vehicles, and having electric vehicle stations, all of which contribute to reducing the carbon footprint. In addition, it has been observed that hotels have various initiatives to reduce greenhouse gases, such as improving waste management, saving energy by using renewable energy sources, and reducing unnecessary water consumption. In terms of long-term sustainability, this criterion supports the COR theory. Recognizing the global significance of tourism-related emissions, the UNWTO mentions market-based incentives in its two recommended reduction strategies to encourage operators to improve their energy and carbon efficiency (UNWTO, 2008). In this study, hotels with sustainable tourism certification also adopt this strategy in selecting agencies they work with. Similarly, it has been observed that agencies also request eco-friendly certificates from hotels. Additionally, hotels aim to support the local community and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by purchasing from nearby suppliers. The values of the criteria following this criterion, C1 (0.141), C2 (0.129), and C4 (0.117), are close to each other. The close values are thought to stem from the criteria being interconnected and closely related to each other. The literature also supports the prioritization of these criteria. The consumption of renewable energy is effective in the process of tourism development that promotes economic growth (Shan & Ren, 2023). The consumption of renewable energy is conducive to achieving sustainable tourism goals (Unruh, 2000). In terms of achieving energy efficiency, policymakers should promote the use of efficient technologies and renewable energy sources across all sectors. Thus, success can be achieved in reaching environmental sustainability and sustainable development goals in the long term. Latief et al. (2024) also present similar recommendations in their study. In this regard, governments can contribute by establishing specific energy quotas and providing incentives for various eco-friendly projects. Mahachi et al. (2015) and Silva (2022) state in their studies that the size of hotels is an important determinant in the adoption of renewable energy. This study similarly examines five-star hotels that have a more institutional structure and are chain hotels. Due to the characteristics of the chains to which these hotels are affiliated, it has been observed that they hold eco-friendly certifications and engage in various collaborations related to eco-friendly initiatives.

It is observed that the C5 (0.069), C6 (0.065), and C7 (0.050) criteria also have similar values and are ranked at the bottom. These results indicate that experts prioritize environmental and economic criteria in sustainable tourism, while criteria related to the socio-cultural dimension are less emphasized. This situation shows that actions supporting the development of the local community are being sidelined compared to other sustainability issues. These criteria involve elements that are difficult to measure quantitatively. Moreover, since the socio-cultural dimension to which these criteria belong is less directly associated with financial outcomes, experts are thought to have assigned it a lower level of priority. However, the participation of the local community in the process is extremely important for the long-term conservation of resources as required by community-based tourism. Ng et al. (2023) emphasized the importance of community participation in preserving the sustainability of cultural heritage. Jelinčić and Tišma (2020) emphasized the importance of establishing indicators to monitor the success of policies at national and local levels for the sustainability of investments in cultural heritage and to measure changes related to local communities.

When the results from the four hotels were examined, it was observed that no single department stood out in sustainability practices, and different departments contributed to the process to varying degrees. The hotel managers included in the study also emphasized that the process should progress from top management to departments and that departments should contribute to the process in different ways. Additionally, the variation in the departments that emerged prominently in the findings may stem from the differing approaches of the hotels’ sustainable tourism policies. For instance, in the food and beverage department, the correct use of resources is more crucial for waste management, while in the housekeeping department, water management and educating customers about environmental concerns may hold greater importance. Furthermore, the high ranking of housekeeping and food and beverage departments in hotels is primarily due to the significant role these departments play in environmental criteria.

It is believed that the differences in the contributions of departments to sustainable tourism among hotels are due to changes in the job descriptions of the departments in the respective hotel management. Different departments can prioritize sustainability to varying degrees based on their responsibilities. For example, the front office department, which has limited connections to practices like energy consumption, water usage, and waste management, remains behind in terms of sustainability. In some hotels, the quality department is involved, and processes progress in conjunction with it, while in hotels without such a department, initiatives are generally carried out by the technical department. Although the hotels share similar characteristics, the differences observed in sustainability performance across departments are likely attributable to operational and organizational factors. These factors may include variations in managerial priorities, resource allocation, and employee engagement. Examining these dynamics can provide a deeper understanding of sustainability practices within hotels. However, the successful implementation of sustainable tourism practices is only possible with equal participation from all departments under the leadership of hotel management.

5.1. Theoretical Implication

A review of the literature indicates that the COR theory has typically been used to measure employees’ behavioral and cognitive responses (Koo et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2021; Guan et al., 2022), examine tourists’ decision-making processes and behaviors (Cheng et al., 2024; S. Liu et al., 2022), and analyze resource conservation in sustainable tourism practices through green supply chain management (Rashid et al., 2024). However, this study differs from previous research by addressing the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory within the context of department-level sustainable tourism practices. This approach provides a theoretical contribution by emphasizing the protection of departmental resources such as human capital, knowledge, energy, time, and service quality. Accordingly, the study demonstrates that the applicability of COR theory extends beyond individual or organizational levels to include the departmental level as well. Moreover, it proposes an innovative framework that ensures the continuity and interdepartmental sharing of resources. In this regard, the research broadens the scope of COR theory in the sustainability literature and establishes a foundation for enhancing the efficiency of resource management across environmental, economic, and socio-cultural dimensions in the long term.

5.2. Practical Implication

Policymakers should make economic growth sustainable by promoting the use of renewable and clean energy sources, ensuring waste recycling, and conserving resources. In these processes, costs can be reduced by utilizing technology. To enhance sustainability performance, smart inventory and waste reduction systems, intelligent energy management technologies that minimize resource costs in departments, water monitoring sensors, and AI-based waste sorting technologies can be implemented. Indeed, Luo et al. (2023) also emphasized the importance of adapting these technologies to the operational characteristics of each department. Similar results were also included in the studies of Zhang and Liu (2019).

Hotels should develop strategies aimed at promoting environmentally friendly innovations among departmental staff. In line with these strategies, employees should receive regular training to stay updated with current information. In the hotels included in the research, employees receive training during the orientation process by the human resources departments. However, it would be beneficial for this training to be reinforced periodically in accordance with the latest developments in sustainability. It can be ensured that hotel employees have the necessary awareness in their respective work areas after training. In particular, to ensure the effectiveness of technological processes, department-based sustainability training sessions should be conducted regularly. Such training will not only enhance employee awareness but also contribute to the establishment of a sustainability-oriented culture throughout the hotel. Additionally, it is important to raise awareness among employees about cultural heritage within the framework of sustainable tourism indicators. In this regard, Ng et al. (2023) emphasize the need to provide training to staff on the region’s cultural heritage, the stories of historical buildings, and language skills. Similarly, Yan and Li (2023) highlight the importance of heritage education as one of the six dimensions they identified for the preservation of intangible cultural heritage in their research. The sustainability performance of the Accounting Department was found to be lower compared to other departments. To address this issue, several actions can be implemented, such as raising staff awareness of sustainability, incorporating environmental cost tracking into financial reporting systems, and considering sustainability principles in financial decision-making processes. These steps could help improve the sustainability performance of departments that currently exhibit weaker outcomes.

The findings indicate that there are differences among departments in terms of sustainability processes, with some departments exhibiting more intensive sustainability practices. This result suggests that departments need to develop strategies tailored to their own operational processes and resource types. Therefore, it is recommended that managers (Q1) prioritize sustainability criteria according to their level of importance, (Q2) monitor the implementation levels of sustainability practices within departments, (Q3) integrate the best-performing departments’ sustainability practices into other departments following the monitoring process, and (Q4) foster sustainability awareness across the organization. These steps will help position the business as a leader in sustainability efforts.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Yuedi et al. (2023) stated that measuring indicators such as tourists’ satisfaction levels, local residents’ satisfaction with tourism, the continuity of tourist satisfaction, and the seasonality of tourism is challenging. In the study, these indicators were excluded from the scope because it was not possible to address them from a departmental perspective. Additionally, the analysis can be enriched by conducting studies on hotels with various eco-friendly certifications or located in different destinations. In this study, only departments were examined. In future research, broader networks of relationships can be established by working with other stakeholders such as the local community, employees, tourism industry professionals and managers, and policymakers. Additionally, in this study, expert opinions were evaluated using the BWM and Fuzzy TOPSIS method. Future researchers can conduct their studies using different criteria weighting and multi-criteria decision-making techniques. In addition, more in-depth research can be conducted through qualitative approaches, such as interviews with hotel managers and local community members.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.O.A., A.C.B. and M.C.; methodology, S.O.A., A.C.B. and M.C.; software, M.C.; validation, S.O.A., A.C.B. and M.C.; formal analysis, S.O.A. and A.C.B.; investigation, S.O.A., A.C.B. and M.C.; resources, S.O.A., A.C.B. and M.C.; data curation, A.C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.O.A., A.C.B. and M.C.; writing—review and editing, S.O.A., A.C.B. and M.C.; visualization, A.C.B.; supervision, S.O.A.; project administration, S.O.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to get an exemption from Republic of Türkiye Selcuk University Faculty of Tourism Scientific Ethics Evaluation Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare that generative AI tools (GPT 5) were used only for language editing and improving the readability of the manuscript. All intellectual content, analysis, and interpretations were produced by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COR | Conservation of Resources |

| BWM | Best Worst Method |

| TOPSIS | Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution |

| UNWTO | The United Nations World Tourism Organization |

| WTO | World Trade Organization |

| ITP | The International Tourism Partnership |

| 3R | reduce, reuse, recycle |

References

- Achille, C., & Fiorillo, F. (2022). Teaching and learning of cultural heritage: Engaging education, professional training, and experimental activities. Heritage, 5(3), 2565–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, W. (2001). Green Development: Environment and sustainability in the third world (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Agyeiwaah, E. (2019). Exploring the relevance of sustainability to micro tourism and hospitality accommodation enterprises (MTHAEs): Evidence from home-stay owners. Journal of Cleaner Production, 226, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amin, M., Nabil, D. H., Baldacci, R., & Rahman, M. H. (2023). Exploring blockchain implementation challenges for sustainable supply chains: An integrated fuzzy topsis–ISM approach. Sustainability, 15(18), 13891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Falah, K. A., & Sundram, V. P. K. (2023). Effects of eco-friendly and green practices on operational performance: Moderating role of green behavioural intention. International Journal of Operations and Quantitative Management, 29(2), 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelevska-Najdeska, K., & Rakicevik, G. (2012). Planning of sustainable tourism development. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 44, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayad, T., Eshaer, I. A., Moustafa, M. A., & Azazz, A. M. (2021). Green product and sustainable tourism development: The role of green buying behavior. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 30(2), 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, W., Khan, I., & Ali, S. A. (2023). Alternative energy and natural resources in determining environmental sustainability: A look at the role of government final consumption expenditures in France. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(1), 1949–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, Q. B., Shah, S. N., Iqbal, N., Sheeraz, M., Asadullah, M., Mahar, S., & Khan, A. U. (2023). Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: A suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(3), 5917–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdanowicz, P., & Zientara, P. (2009). Hotel companies’ contribution to improving the quality of life of local communities and the well-being of their employees. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 9(2), 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y., Liang, S., Cheng, H., Law, R., & Sun, N. (2024). Between a rock and a hard place: How does the tourist crowding perception affect the decision of absolute displacement? Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 29(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H. C., & Sirakaya, E. (2006). Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1274–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicekdagi, H. I., Ayyildiz, E., & Akkoyunlu, M. C. (2023). Enhancing search and rescue team performance: Investigating factors behind social loafing. Natural Hazards, 119(3), 1315–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvelbar, L. K., Grün, B., & Dolnicar, S. (2017). Which hotel guest segments reuse towels? Selling sustainable tourism services through target marketing. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(7), 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, M. N., & Çevirgen, A. (2021). The role of accommodation enterprises in the development of sustainable tourism. Journal of Tourism and Services, 23(12), 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diawati, P., & Loupias, H. H. (2018, March). The negative impact of rapid growth of culinary tourism in Bandung City: Implementation of innovative and eco-friendly model are imperative. In 2nd international conference on tourism, gastronomy, and tourist destination (ICTGTD 2018) (pp. 372–381). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnicar, S. (2022). Tourist behaviour change for sustainable consumption (SDG goal 12): Tourism agenda 2030 perspective article. Tourism Review, 78(2), 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, R., Pallesen, S., Böhm, G., & Ogunbode, C. A. (2022). When and why do people experience flight shame? Annals of Tourism Research, 92, 103254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2015). An EU action plan for the Circular Economy. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52015DC0614 (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Girard, L. F., & Nijkamp, P. (Eds.). (2009). Cultural tourism and sustainable local development (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S., Balas, M., Mayer, M., & Sun, Y. Y. (2023). A review of tourism and climate change mitigation: The scales, scopes, stakeholders and strategies of carbon management. Tourism Management, 95, 104681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grah, B., Dimovski, V., & Peterlin, J. (2020). Managing sustainable urban tourism development: The case of Ljubljana. Sustainability, 12(3), 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X., Gong, J., & Huan, T. C. (2022). Trick or treat! How to reduce co-destruction behavior in tourism workplace based on conservation of resources theory? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 52, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X., Yeh, S., Chiang, T., & Huan, T. T. C. (2020). Does organizational inducement foster work engagement in hospitality industry? Perspectives from a moderated mediation model. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 43, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong Van, V. (2020). Linking cultural heritage with cultural tourism development: A way to develop tourism sustainably. Preprints, 2020080546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C. L., & Yoon, K. (1981). Multiple attribute decision making: Methods and applications, a state-of-the-art survey. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITP (The International Tourism Partnership). (2018). ITP’s water stewardship report for hotel companies—March 2018. ITP. [Google Scholar]

- Jelinčić, D. A., & Tišma, S. (2020). Ensuring sustainability of cultural heritage through effective public policies. Urbani Izziv, 31(2), 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L., Shaw, J. D., Tsui, A. S., & Park, T. Y. (2014). A social-structural perspective on employee-organization relationships and team creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 57(3), 869–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyani, V. L., Dudy, M. K., & Pareek, S. (2015). Green energy: The need of the world. Journal of Management Engineering and Information Technology, 2(5), 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, I., & Hou, F. (2021). The dynamic links among energy consumption, tourism growth, and the ecological footprint: The role of environmental quality in 38 IEA countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28, 5049–5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, I., Anjam, M., & Zaman, U. (2022). Hell is empty, and all the devils are here: Nexus between toxic leadership, crisis communication, and resilience in COVID-19 tourism. Sustainability, 14(17), 10825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurar, İ. (2021). Research on the determination of recreational experience preferences, expectations, and satisfaction levels of local people. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Knowledge, 9(1), 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Morales, O., & Clarke, A. (2024). Sustainable tourism value chain analysis as a tool to evaluate tourism’s contribution to the sustainable development goals and local Indigenous communities. Journal of Ecotourism, 23(2), 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latief, R., Pei, Y., Javeed, S. A., & Sattar, U. (2024). Environmental sustainability in the belt and road initiative (BRI) countries: The role of sustainable tourism, renewable energy and technological innovation. Ecological Indicators, 162, 112011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. H., & Hsieh, H.-P. (2016). Indicators of sustainable tourism: A case study from a Taiwan’s wetland. Ecological Indicators 67, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. H., & Jan, F.-H. (2019). Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development? Evidence from residents’ perceptions of the sustainability. Tourism Management, 70, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, M., Sun, Y. Y., Faturay, F., Ting Y, P., Geschke, A., & Malik, A. (2018). The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nature Clim Change, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Liang, Y., Song, Q., & Li, J. (2017). A review of waste prevention through 3R under the concept of circular economy in China. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 19, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Cheng, P., & Wu, Y. (2022,The negative influence of environmentally sustainable behavior on tourists. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 51, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z., Gozgor, G., & Lau, C. K. M. (2019). The dynamic impacts of renewable energy and tourism investments on international tourism: Evidence from the G20 countries. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 20(6), 1102–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D., He, S., Wu, H., Cheng, L., & Li, J. (2023). An integrated approach to green mines based on hesitant fuzzy TOPSIS: Green degree analysis and policy implications. Sustainability, 15(13), 10468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftuhah, D. I., & Wirjodirdjo, B. (2018, June). Model for developing five key pillars of sustainable tourism: A literature review. In AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 1977, No. 1, p. 040009). AIP Publishing LLC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahachi, D., Mokgalo, L., & Pansırı, J. (2015). Exploitation of renewable energy in the hospitality sector: Case studies of Gaborone Sun and the Cumberland Hotel in Botswana. International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Administration, 16(4), 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevia, D. (2001). Sustainable urban development in India: An inclusive perspective. Development in Practice, 11(2–3), 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, A., Walia, S. K., & Rasoolimanesh, S. M. (2024). Gen Z and the flight shame movement: Examining the intersection of emotions, biospheric values, and environmental travel behaviour in an Eastern society. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(8), 1621–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarroll, M. J., LaVanchy, G. T., & Kerwin, M. W. (2024). Tourism resilience to drought and climate shocks: The role of tourist water literacy in hotel management. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 5(2), 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrema, A. A. (2015). Contribution of tourist hotels in socio-economic development of local communities in Monduli District, Northern Tanzania. Journal of Hospitality and Management Tourism, 6(6), 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muganda, M., Sahli, M., & A Smith, K. (2010). Tourism’s contribution to poverty alleviation: A community perspective from Tanzania. Development Southern Africa, 27(5), 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nădăban, S., Dzitac, S., & Dzitac, I. (2016). Fuzzy TOPSIS: A general view. Procedia Computer Science, 91, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedyalkova, S. (2016, October 5–9). Applying circular economy principles to sustainable tourism development. PM4SD European Summer School-Abstract and Conference Proceedings (pp. 38–44), Akureyri, Iceland. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, W. K., Hsu, F. T., Chao, C. F., & Chen, C. L. (2023). Sustainable competitive advantage of cultural heritage sites: Three destinations in East Asia. Sustainability, 15(11), 8593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyikana, S., & Sigxashe, Z. (2017). Owner/managers perceptions on the influence of the accommodation sector on tourism and local well-being in Coffee Bay. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 6(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Oesselman, D., & Pfeifer-Schaupp, U. (2012). Sustainability—Six dimensions of a holistic principle. Amazon, Organizations and Sustainability, 3(2), 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padín, C. (2012). A sustainable tourism planning model: Components and relationships. European Business Review, 24(6), 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, M., Nyaupane, G. P., & Budruk, M. (2016). Stakeholders’ perspectives of sustainable tourism development: A new approach to measuring outcomes. Journal of Travel Research, 55(4), 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A., & Sharma, V. (2023). Ecotels-a way to green sustainable tourism. International Journal of Asian Business and Management, 2(2), 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A., Rasheed, R., Albhirat, M. M., & Amirah, N. A. (2024). Conservation of resources for sustainable performance in tourism. Journal of Tourism Management Research, 11(1), 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J. (2015). Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method. Omega, 53, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J. (2020). A concentration ratio for nonlinear best worst method. International Journal of Information Technology & Decision Making, 19(03), 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S. S., Xalxo, M. M., & BG, M. M. (2020). A study on tourist behaviour towards sustainable tourism in Karnataka. International Research Journal on Advanced Science Hub, 2(05), 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y., & Ren, Z. (2023). Does tourism development and renewable energy consumption drive high quality economic development? Resources Policy, 80, 103270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L. (2022). Adoption of renewable energy innovations in the Portuguese rural tourist accommodation sector. Moravian Geographical Reports, 30(1), 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, B., & T.V, P. (2012). A simplified description of Fuzzy TOPSIS. arXiv, arXiv:1205.5098. [Google Scholar]

- Strippoli, R., Gallucci, T., & Ingrao, C. (2024). Circular economy and sustainable development in the tourism sector–An overview of the truly-effective strategies and related benefits. Heliyon, 10(17), e36801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbiah, K., & Kannan, S. (2011, December). The eco-friendly management of hotel industry. In International conference on Green technology and environmental Conservation (GTEC-2011) (pp. 285–290). IEEE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, N. M., Suki, N. M., Sharif, A., Afshan, S., & Jermsittiparsert, K. (2022). The role of technology innovation and renewable energy in reducing environmental degradation in Malaysia: A step towards sustainable environment. Renewable Energy, 182, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C., & Özdemir, S. (2015). Green-Star study in environmentally-sensitive hospitality industry in terms of managers as a competitive advantage. Journal of Recreation and Tourism Research, 2(4), 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, C., Parvez, M. O., Bilim, Y., & Yu, L. (2022). Effects of green transformational leadership on green performance of employees via the mediating role of corporate social responsibility: Reflection from North Cyprus. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 103, 103218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. (2005). Making tourism more sustainable: A guide for policy makers. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/making-tourism-more-sustainable-guide-policy-makers (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- United Nations. (2015). International year of sustainable tourism for development. Available online: http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/C.2/70/L.5 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Unruh, G. C. (2000). Understanding carbon lock-in. Energy Policy, 28(12), 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. (2004). Indicators of sustainable development for tourism destinations: A guidebook. UNWTO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. (2008). Climate change and tourism responding to global challenges (World Tourist Organisation, United Nations Environment Programme, World Meteorological Organisation, 2008). Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284412341 (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- UNWTO. (2020). International tourist numbers could fall 60–80% in 2020 (Unwto Reports). Available online: www.unwto.org/news/covid-19-international-tourist-numbers-could-fall-60-80-in-2020 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Wang, Q., & Wang, L. (2020). Renewable energy consumption and economic growth in OECD countries: A nonlinear panel data analysis. Energy, 207, 118200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnken, J., Bradley, M., & Guilding, C. (2004). Exploring methods and practicalities of conducting sector-wide energy consumption accounting in the tourist accommodation industry. Ecological Economics, 48(1), 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. (2023). Available online: https://www.weforum.org (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- WWF (World Wildlife Fund). (2014). Turkey’s water footprint report. Available online: http://www.wwf.org.tr (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Yan, D., & Li, G. (2023). A heterogeneity study on the effect of digital education technology on the sustainability of cognitive ability for middle school students. Sustainability, 15(3), 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuedi, H., Sanagustín-Fons, V., Coronil, A. G., & Moseñe-Fierro, J. A. (2023). Analysis of tourism sustainability synthetic indicators. A case study of Aragon. Heliyon, 9(4), e15206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuliani, S., & Setyaningsih, W. (2024). Green architecture in tourism sustainable development a case study at Laweyan, Indonesia. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 24(1), 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksek, G., Dinçer, F. İ., & Dinçer, M. Z. (2019). Sustainable tourism awareness of Seyitgazi stakeholders. Uluslararası Türk Dünyası Turizm Araştırmaları Dergisi, 4(1), 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S., & Liu, X. (2019). The roles of international tourism and renewable energy in environment: New evidence from Asian countries. Renew. Energy, 139, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Zhang, Y., He, X., Axmacher, J. C., & Sang, W. (2024). Gains in China’s sustainability by decoupling economic growth from energy use. Journal of Cleaner Production, 448, 141765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Mistry, T. G., Kim, W. G., & Cobanoglu, C. (2021). Workplace mistreatment in the hospitality and tourism industry: A systematic literature review and future research suggestions. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 49, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).