1. Introduction

The rise of ergonomics within tourism and hospitality organizations reflects the growing need to meet the changing demands of a dynamic industry, marked by intensive service interactions and physically strenuous tasks (

Ciarlante et al., 2024). As the industry expands, there is increasing recognition of the importance of creating work environments that support the well-being of both employees and customers (

Al-Husain et al., 2025;

Al-Romeedy et al., 2025;

Khairy et al., 2025). Ergonomics centers on designing workplaces that boost comfort and efficiency while minimizing the risk of injury. In hospitality venues such as hotels, restaurants, and travel services, employees often perform repetitive tasks, work extended hours, and face physical challenges, all of which can contribute to fatigue and musculoskeletal issues. By applying ergonomic principles, businesses can create environments that encourage proper posture, minimize physical strain, and improve operational efficiency, ultimately fostering a more productive workforce (

Stack & Ostrom, 2023). Moreover, improving ergonomics benefits not only employees but also enhances guest experiences, with features like accessible seating and user-friendly service interfaces contributing to higher levels of customer satisfaction. As the emphasis on well-being and sustainable practices grows, tourism and hospitality businesses that prioritize ergonomics are likely to gain a competitive edge by appealing to both highly skilled workers and a loyal customer base (

Burke, 2020;

Tosi & Tosi, 2020).

Ergonomics advocates for a user-centered strategy that simultaneously improves human well-being and fosters environmental stewardship (

Davey, 2022). By incorporating ergonomic principles into workplace and product design, organizations can develop solutions that emphasize safety, comfort, and operational efficiency while reducing their ecological footprint. This often involves the adoption of sustainable materials, lessening waste, and increasing resource efficiency, thereby supporting broader sustainability objectives (

Stack & Ostrom, 2023). Additionally, ergonomic designs boost employee satisfaction and engagement, which in turn can stimulate creativity and drive innovation within the company (

Surianto & Nurfahira, 2024). Consequently, the integration of ergonomics with sustainable innovation addresses users’ immediate needs while also advancing long-term environmental sustainability, paving the way for a more resilient and socially responsible future for businesses and communities alike (

Karwowski et al., 2021).

Also, ergonomics, by its nature, enhances employee comfort, productivity, and overall well-being, which plays a crucial role in increasing work engagement (

Adiga, 2023). When employees feel physically supported and at ease in their workspaces, they tend to be more focused, dedicated, and attentive to their tasks, particularly those related to sustainable practices. This higher level of engagement fosters a sense of responsibility and alignment between employees’ values and the organization’s sustainability objectives (

Meng et al., 2024). Moreover, applying ergonomic principles to support green initiatives—such as using energy-efficient equipment, sustainable materials, and creating comfortable environments for sustainability tasks—naturally motivates employees to participate in these efforts. This intrinsic motivation arises from employees seeing their contributions as meaningful and impactful (

Hedge, 2016). For instance, an ergonomically designed workstation for green projects not only minimizes physical discomfort but also inspires employees to invest more in initiatives that benefit the environment. As a result, employees who experience greater physical comfort are more inclined to engage in eco-friendly behaviors, thereby fostering a culture of sustainability within the organization (

Norton et al., 2021).

In addition, when employees are deeply engaged in green work, they are more likely to come up with innovative ideas that align with sustainability goals (

Khairy et al., 2025;

Wang et al., 2025). This stems from the fact that engaged employees view their contributions as meaningful and closely tied to their values, motivating them to develop creative solutions for environmental challenges (

Ahmad et al., 2024;

Bhatnagar & Aggarwal, 2020). Similarly, green intrinsic motivation—the internal drive to engage in environmentally friendly behaviors based on personal beliefs—amplifies this process (

Meng et al., 2024). Employees driven by intrinsic motivation are more willing to experiment with new approaches, adopt sustainable practices, and advocate for environmentally sound changes, even without external rewards (

Leidner et al., 2019;

Graafland & Bovenberg, 2020). For example, employees passionate about reducing waste or enhancing energy efficiency often collaborate across departments to create innovative processes or products that reflect these goals. Furthermore, organizations that cultivate a culture of green work engagement and intrinsic motivation are better equipped to identify and act on emerging trends in sustainability. Their workforce, being environmentally conscious and proactive, consistently seeks out opportunities for sustainable innovation (

Brown et al., 2021;

Jamil et al., 2023).

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) provides a crucial framework for understanding the relationship between ergonomics, sustainable innovation, and employee motivation in hotel businesses by emphasizing the role of intrinsic motivation in driving engagement and well-being (

Zhang et al., 2023). According to SDT, individuals are more likely to engage in sustainability-promoting behaviors when they feel a sense of competence, autonomy, and relatedness in their work (

Gagné et al., 2018). In the context of ergonomics, when hotels introduce ergonomic practices that boost comfort and efficiency, employees develop a stronger sense of control and capability in their roles, which enhances their green intrinsic motivation. This increase in motivation drives employees to engage in sustainable initiatives and contribute to innovation, thereby fostering a culture of green work engagement (

Wang et al., 2025). Through SDT, we understand how ergonomic improvements not only enhance employee well-being but also spark sustainable innovation by aligning employees’ intrinsic values with the organization’s sustainability objectives. To enrich this understanding, the study also draws on insights from Innovation Theory, which emphasizes how supportive work environments, resource availability, and efficient work design stimulate creativity and the generation of new ideas (

Ramos et al., 2018). Innovation Theory complements SDT by illustrating the organizational conditions that enable employees to transform their intrinsic motivation into innovative, sustainability-oriented behaviors (

Duong, 2025;

Saxena et al., 2024). While SDT explains the psychological mechanisms—why employees become motivated (

El-Sherbeeny et al., 2023)—Innovation Theory clarifies how ergonomic improvements create the structural and organizational enablers that facilitate sustainable innovation (

Jorna, 2017). This integration provides a more comprehensive perspective, showing that ergonomic practices simultaneously activate internal motivational drivers and strengthen the organizational context needed for innovation to emerge within the hospitality sector.

Despite the growing acknowledgment of the importance of ergonomics and sustainable innovation in hotel businesses, several key research gaps remain that require further exploration. First, while the effects of ergonomics on employee performance and well-being are well-established, there is a scarcity of empirical studies that specifically examine the intersection of ergonomics and sustainable innovation within the hotel industry. Many existing studies tend to address general workplace ergonomics or sustainability initiatives in isolation, overlooking the potential for ergonomic improvements to catalyze sustainable innovation. Additionally, the mediating roles of green work engagement and green intrinsic motivation in this dynamic are largely underexplored. Although previous research has highlighted the link between employee engagement and sustainability outcomes, few studies have explicitly investigated how ergonomics can influence these mediators, leaving a significant gap in understanding how these elements interact. Furthermore, much of the research overlooks the unique challenges and opportunities that hotel businesses encounter when implementing ergonomic and sustainability practices, such as the wide variety of roles within the industry and the differing organizational structures. These context-specific factors are crucial for a comprehensive understanding of how ergonomics can drive sustainability in this sector.

To bridge the identified research gaps, this study sets out several key objectives. Firstly, it aims to explore the influence of ergonomic interventions on sustainable innovation, green work engagement, and green intrinsic motivation within hotel businesses. This will provide a deeper understanding of how ergonomics not only affects employee well-being but also drives sustainable innovation. Secondly, the study seeks to examine the specific impact of green work engagement and green intrinsic motivation on sustainable innovation, offering insights into how these motivational factors contribute to organizational sustainability goals. Thirdly, the research will investigate the mediating roles of green work engagement and green intrinsic motivation in the relationship between ergonomics and sustainable innovation. By unraveling these connections, the study will shed light on how hotel organizations can cultivate environments that simultaneously promote employee well-being and advance sustainability practices. These objectives aim to address current gaps in the literature and contribute both to academic discourse and to practical strategies for improving ergonomics, sustainability, and management practices in the hospitality industry.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Effect of Ergonomics on Sustainable Innovation

The impact of ergonomics on sustainable innovation is increasingly seen as a key factor in driving efficiency, enhancing employee well-being, and promoting environmental responsibility across diverse sectors such as hospitality, manufacturing, and corporate settings. Ergonomics, which involves tailoring the work environment to meet the needs of the user, plays a crucial role in improving human performance and comfort. By focusing on ergonomic design, organizations create workspaces that not only reduce physical strain and discomfort but also boost productivity and job satisfaction (

Bolis et al., 2023). The connection between ergonomics and sustainable innovation can also be understood through systems thinking, which highlights how different components within an organization are interconnected (

Burke, 2020). Ergonomic enhancements support the integration of sustainable practices by making it easier for employees to engage in eco-friendly behaviors. For example, sustainability-focused ergonomic workstations can encourage efficient use of resources like energy and materials (

Stack & Ostrom, 2023). This not only improves organizational efficiency but also prompts employees to consider the environmental impact of their actions. When employees are equipped with ergonomic tools and systems aligned with sustainability goals, they are more likely to adopt green practices, fostering a culture of innovation centered on environmental stewardship (

Wang et al., 2025). This cultural shift can lead to the creation of new products, services, and processes that prioritize sustainability, giving the organization a competitive edge in the marketplace (

Hasanain, 2024;

Esty & Winston, 2009). So, the following hypothesis is suggested:

H1: Ergonomics positively influences sustainable innovation.

2.2. The Effect of Ergonomics on Green Work Engagement

Ergonomics plays a crucial role in enhancing employee comfort and satisfaction, significantly improving their well-being. When employees operate in ergonomically designed environments, they experience less physical strain and discomfort, which directly boosts their overall health and job satisfaction (

Tosi & Tosi, 2020). This improved well-being is essential for fostering engagement in green initiatives, as employees who feel comfortable and supported are more inclined to dedicate time and energy toward sustainable practices (

Burke, 2020). Beyond physical benefits, ergonomics also impacts the psychological dimensions of green work engagement by promoting feelings of autonomy and competence (

Molino et al., 2020). Ergonomic workplace designs provide employees with the necessary tools and resources to perform their duties efficiently, thereby empowering them and fostering a sense of ownership over their work. This empowerment increases motivation to participate in green practices (

Karwowski et al., 2021). For instance, when employees feel that their ergonomic workstations allow them to work more efficiently, they are more likely to have additional time and energy to devote to sustainability initiatives. This sense of competence strengthens their intrinsic motivation to contribute to environmental sustainability, as they view their efforts as meaningful and impactful. Therefore, ergonomics not only enhances physical comfort but also influences the psychological and emotional dynamics of the workplace, playing a vital role in shaping green work engagement (

Gajšek et al., 2022;

Hasanain, 2024).

Moreover, the connection between ergonomics and green work engagement is evident in how ergonomic enhancements can promote collaboration and communication among employees (

Duque et al., 2020). Ergonomically designed collaborative spaces, such as flexible meeting rooms and open work environments, encourage teamwork and the sharing of ideas focused on sustainability initiatives (

Norton et al., 2021). When employees feel at ease in ergonomically optimized settings, they are more inclined to engage in conversations about green practices, brainstorm innovative solutions, and collectively take ownership of sustainability objectives. This collaborative environment boosts green work engagement, as employees develop a sense of camaraderie and shared responsibility for environmental outcomes (

Hasanein & Metwally, 2025). Additionally, organizations that emphasize ergonomics often communicate their dedication to employee well-being and sustainable practices, reinforcing the importance of green engagement within their organizational culture. Employees are likely to respond positively to this ethos, resulting in increased participation in green initiatives and a deeper commitment to sustainability (

Stack & Ostrom, 2023;

Faeq & Saleh, 2025). Hence, the following hypothesis is adopted:

H2: Ergonomics positively influences green work engagement.

2.3. The Effect of Green Work Engagement on Sustainable Innovation

Green work engagement encompasses the enthusiasm, commitment, and proactive involvement of employees in environmentally sustainable initiatives within their organizations (

Karatepe et al., 2022;

Abdou et al., 2023). When employees are actively engaged in green practices, they not only contribute to the achievement of sustainability goals but also become catalysts for innovation in their respective areas. This engagement can take various forms, such as generating innovative ideas for waste reduction, enhancing energy efficiency, and developing eco-friendly products and services (

Fontoura & Coelho, 2022;

Begum et al., 2022). Employees who are passionate about sustainability often take the initiative to propose creative solutions that align with their organization’s environmental objectives, thereby fostering a dynamic atmosphere that supports sustainable innovation (

Khan et al., 2024). Moreover, green work engagement cultivates a culture of collaboration and creativity that is crucial for advancing sustainable innovation (

Arici & Uysal, 2022). When employees are committed to green initiatives, they are more likely to share ideas and collaborate with their colleagues. This collaborative mindset enhances the organization’s capacity to leverage diverse perspectives and expertise, both of which are vital for the innovation process (

Kim et al., 2017). For instance, when teams of engaged employees unite to address sustainability challenges, they can combine their knowledge and creativity to devise innovative strategies that may not have arisen in a more traditional, siloed work setting. This synergy not only accelerates the creation of sustainable solutions but also bolsters the overall innovation capacity of the organization (

Ajayi & Udeh, 2024;

Costa & Matias, 2020). As employees collaborate on green projects, they develop a sense of ownership and accountability for the results, which further inspires them to invest their best efforts in the innovation process (

Schaltegger & Burritt, 2018).

Furthermore, green work engagement plays a crucial role in ensuring the long-term success of innovation initiatives focused on sustainability (

Umair et al., 2024). When employees actively participate in sustainability efforts, they are more likely to perceive their contributions as significant and integral to the organization’s mission. This sense of intrinsic motivation drives them to remain dedicated to continuous innovation and improvement, even when faced with challenges or obstacles (

Afsar et al., 2020). For example, employees passionate about environmental issues are likely to persist in exploring new avenues for innovation, such as implementing advanced technologies or processes that enhance sustainability, even in the face of resistance or limited resources. Their determination and commitment can foster a perpetual cycle of innovation, where sustainable practices are consistently evaluated and improved, leading to a more substantial environmental impact and enhanced operational efficiency (

Al-Romeedy et al., 2025). Therefore, the following hypothesis is demonstrated:

H3: Green work engagement positively influences sustainable innovation.

2.4. The Mediating Role of Green Work Engagement

Ergonomics, which emphasizes the optimization of work environments and tasks to align with the physical and cognitive needs of employees, plays a pivotal role in enhancing their comfort, productivity, and overall job satisfaction. Organizations that prioritize ergonomic improvements—such as investing in ergonomic furniture, adequate lighting, and intuitive tools—cultivate a supportive atmosphere that minimizes physical discomfort and boosts mental focus (

Tosi & Tosi, 2020). This increased level of comfort and productivity fosters a positive work environment, encouraging employees to engage more actively in their responsibilities, including sustainability initiatives. As a result, ergonomic design becomes a vital factor in amplifying green work engagement, motivating employees to contribute proactively to sustainable practices and projects within their organization (

Stack & Ostrom, 2023).

Green work engagement serves as a crucial link between the advantages of ergonomic design and the organization’s potential for sustainable innovation. When employees are actively involved in green practices, they demonstrate heightened enthusiasm and commitment to environmental initiatives, which catalyzes the generation of new ideas and strategies that advance sustainability (

Karwowski et al., 2021). Those who benefit from an ergonomic workspace often feel more competent and empowered to pinpoint areas for sustainability enhancements, whether through implementing energy-saving measures, reducing waste, or adopting eco-friendly products. This intrinsic motivation—stemming from both the comfort afforded by ergonomic conditions and the aspiration to achieve significant environmental objectives—empowers employees to take initiative toward innovation (

Stack & Ostrom, 2023). Therefore, green work engagement acts as a mediator between ergonomics and sustainable innovation, transforming employee comfort into actionable insights and creative solutions that align with the organization’s sustainability goals (

Mohezar et al., 2021). Moreover, the role of green work engagement as a mediator highlights the significance of fostering a supportive organizational culture that prioritizes both ergonomics and sustainability. When hotel businesses and other organizations emphasize ergonomic design, they communicate to employees that their well-being is valued, which nurtures a sense of loyalty and dedication. This supportive atmosphere deepens employees’ emotional connection to the organization, boosting their motivation to participate in sustainability initiatives (

E-Vahdati et al., 2023;

Jiménez-Estévez et al., 2023). As employees feel appreciated and comfortable, they are more inclined to collaborate with their colleagues, exchange ideas, and engage in joint efforts focused on improving the organization’s environmental performance. This collaborative engagement enhances the potential for innovative solutions, as varied perspectives and expertise unite to tackle sustainability challenges (

Pratson et al., 2021;

Valentine, 2016). Consequently, green work engagement acts not only as a mediator but also as a multiplier, increasing the efficacy of ergonomic initiatives in driving sustainable innovation (

E-Vahdati et al., 2023). Accordingly, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H4: Green work engagement mediates the effect of ergonomics on sustainable innovation.

2.5. The Effect of Ergonomics on Green Intrinsic Motivation

When employees operate within ergonomically designed environments, they experience a notable reduction in physical discomfort, significantly enhancing their overall job satisfaction (

Burke, 2020;

Miles & Perrewé, 2011). This increased comfort cultivates a positive workplace atmosphere and allows employees to concentrate better on their tasks, including sustainability-related activities (

Tosi & Tosi, 2020). With less physical strain and greater ease, employees can engage more fully—both mentally and emotionally—with their work, which in turn boosts their intrinsic motivation. This form of motivation refers to the desire to partake in an activity for its inherent enjoyment and satisfaction rather than for external incentives (

Reeve, 2024;

Karwowski et al., 2021). Green intrinsic motivation specifically denotes the internal impetus that drives employees to adopt environmentally friendly practices and initiatives based on their values and beliefs about sustainability (

Tian et al., 2020). When ergonomic principles are seamlessly woven into the workplace, employees are more likely to cultivate a strong sense of ownership and accountability regarding sustainable practices (

Meyer et al., 2017). For example, when provided with ergonomic workstations that prioritize comfort and efficiency, employees may feel more empowered to engage in green initiatives, such as recycling programs or energy-saving measures (

Thomas et al., 2024). The alleviation of physical stress, along with the provision of effective tools, enables employees to view their contributions to sustainability as significant and impactful. This sense of competence and effectiveness strengthens their intrinsic motivation to participate in eco-friendly actions, as they recognize that their efforts can yield positive environmental results (

Etuknwa et al., 2019;

Usman et al., 2023).

A thoughtfully designed ergonomic environment communicates to employees that their well-being is a priority, fostering a sense of belonging and loyalty to the organization. This emotional connection motivates employees to align their values with the organization’s goals, especially concerning sustainability efforts (

Mohezar et al., 2021). When employees believe that their organization genuinely values environmental stewardship, their intrinsic motivation to engage in green initiatives tends to rise (

Karwowski et al., 2021). They may feel driven to contribute not merely due to external rewards but because they identify with the organization’s values and mission. This alignment between individual and organizational values can cultivate a deeper commitment to sustainability, resulting in heightened efforts toward innovative green practices (

Wojtczuk-Turek et al., 2024;

Al-Romeedy et al., 2025). Accordingly, the following hypothesis is highlighted:

H5: Ergonomics positively influences green intrinsic motivation.

2.6. The Effect of Green Intrinsic Motivation on Sustainable Innovation

When employees are strongly intrinsically motivated toward sustainable practices, they are more inclined to actively engage in sustainability initiatives and contribute innovative solutions that align with their organization’s environmental objectives. This intrinsic motivation cultivates a deeper commitment to sustainability, encouraging a proactive attitude that empowers employees to take ownership of their roles in promoting sustainable innovation (

Buhl et al., 2016;

Ashraf et al., 2024). Employees who are driven by green values often perceive sustainability not merely as a responsibility but as a fundamental aspect of their professional identity. This sense of identity fosters a strong bond between employees and their organization’s sustainability goals, prompting them to prioritize green initiatives in their daily tasks (

Graves & Sarkis, 2018;

Aggarwal & Agarwala, 2023). Those motivated by a belief in environmental stewardship are more likely to identify inefficiencies in processes and propose creative solutions aimed at reducing waste, conserving energy, or utilizing sustainable materials (

Meng et al., 2024). This proactive involvement can lead to the creation of new products, services, or processes that not only adhere to sustainability standards but also enhance the organization’s competitive edge in the market. When employees are intrinsically motivated to pursue sustainable innovation, their contributions can result in breakthroughs that may not have emerged from a less engaged workforce (

Kuo et al., 2022;

Nazir & Islam, 2020).

In addition, green intrinsic motivation fosters collaborative efforts among employees, promoting knowledge sharing and the co-creation of innovative solutions. When individuals are united by shared sustainability values, they are more inclined to participate in teamwork and collective problem-solving. This collaboration is vital for sustainable innovation, as diverse perspectives and expertise lead to more comprehensive and effective solutions (

Colabi et al., 2022;

Steiner, 2009;

Mariani et al., 2022). Cross-functional teams, composed of members from various departments—such as marketing, operations, and product development—can brainstorm and implement innovative sustainability initiatives that address different facets of the organization’s operations (

Nakata & Im, 2010;

Piercy et al., 2013). The synergy created through these collaborative efforts not only enhances creativity and idea generation but also fosters a sense of community among employees, reinforcing their commitment to the organization’s sustainability goals (

Wright et al., 2022).

Furthermore, green intrinsic motivation can cultivate a culture of continuous improvement within an organization (

Rizvi & Garg, 2021). Employees who are driven by their passion for sustainability are more likely to seek new knowledge and skills to deepen their understanding of environmental issues and innovative practices. This quest for learning can lead to the adoption of cutting-edge technologies, processes, or practices that significantly propel the organization’s sustainability initiatives (

Jia et al., 2018;

Nwokolo et al., 2023). For instance, employees might proactively research and implement renewable energy sources, explore sustainable supply chain strategies, or invest in eco-friendly product development. Their dedication to ongoing learning and improvement ensures that sustainable innovation remains a priority, creating an adaptive and resilient organization capable of addressing the ever-changing landscape of environmental challenges (

Barakat et al., 2023;

Nuraini, 2024;

Moşteanu, 2024;

Alnasser et al., 2025). So, the following hypothesis is assumed:

H6: Green intrinsic motivation positively influences sustainable innovation.

2.7. The Mediating Role of Green Intrinsic Motivation

When organizations prioritize ergonomic principles in their design, they significantly enhance employees’ overall job satisfaction and comfort, which, in turn, fosters greater engagement in their work (

Tosi & Tosi, 2020). This increased engagement often leads to higher levels of green intrinsic motivation, where employees are internally driven to participate in sustainability initiatives not merely for external rewards but out of genuine concern for the environment and a commitment to sustainable practices (

Stack & Ostrom, 2023). The interplay between ergonomics and green intrinsic motivation is pivotal in creating an environment where employees feel empowered to innovate sustainably (

Khusanova et al., 2019). The implementation of ergonomic designs—such as adjustable workstations, comfortable seating, and optimal lighting—reduces physical strain and discomfort, enabling employees to experience increased comfort. This enhanced comfort can lead to heightened cognitive focus and emotional well-being, allowing employees to channel their energy toward creative problem-solving and sustainable initiatives (

McKeown, 2018). For instance, a comfortable workspace may inspire employees to actively seek ways to reduce waste or improve energy efficiency in their daily tasks. The reduction in physical barriers enhances their capacity to think critically about sustainability issues, leading to innovative ideas and solutions that align with the organization’s environmental goals. Thus, green intrinsic motivation serves as a mediator in the relationship between ergonomics and sustainable innovation, transforming physical comfort into a catalyst for creative thinking and environmental responsibility (

Staddon et al., 2016;

Tosi & Tosi, 2020).

Moreover, green intrinsic motivation serves as a powerful driver of collaborative efforts within organizations, further enhancing the potential for sustainable innovation. When employees are motivated by their values related to sustainability, they are more inclined to collaborate with colleagues across departments to develop innovative solutions (

Delmas & Pekovic, 2018). The comfortable and supportive environment fostered by ergonomic principles encourages teamwork, as employees feel physically and psychologically safe to express their ideas and participate in collective sustainability initiatives (

Karanikas & Pazell, 2022). For example, ergonomic workspaces that promote interaction among employees can lead to brainstorming sessions that generate innovative ideas for reducing the organization’s carbon footprint or enhancing the efficiency of resource use. This collaborative spirit is essential for sustainable innovation, as it allows diverse perspectives and expertise to converge, leading to more comprehensive and effective solutions (

McKeown, 2018). Additionally, when organizations invest in ergonomic improvements and foster an environment that prioritizes employee well-being, they signal their commitment to sustainability and employee engagement. This alignment of values reinforces employees’ intrinsic motivation to contribute to sustainability initiatives (

Hasanain, 2024;

Meng et al., 2024). Employees who feel valued and supported are more likely to see their contributions as meaningful, thus enhancing their motivation to innovate sustainably. This connection between ergonomic design, employee well-being, and green intrinsic motivation creates a feedback loop that not only fosters innovation but also strengthens the organization’s culture of sustainability (

Wikhamn, 2019;

Karwowski et al., 2021). Consequently, the following hypothesis is developed:

H7: Green intrinsic motivation mediates the effect of ergonomics on sustainable innovation.

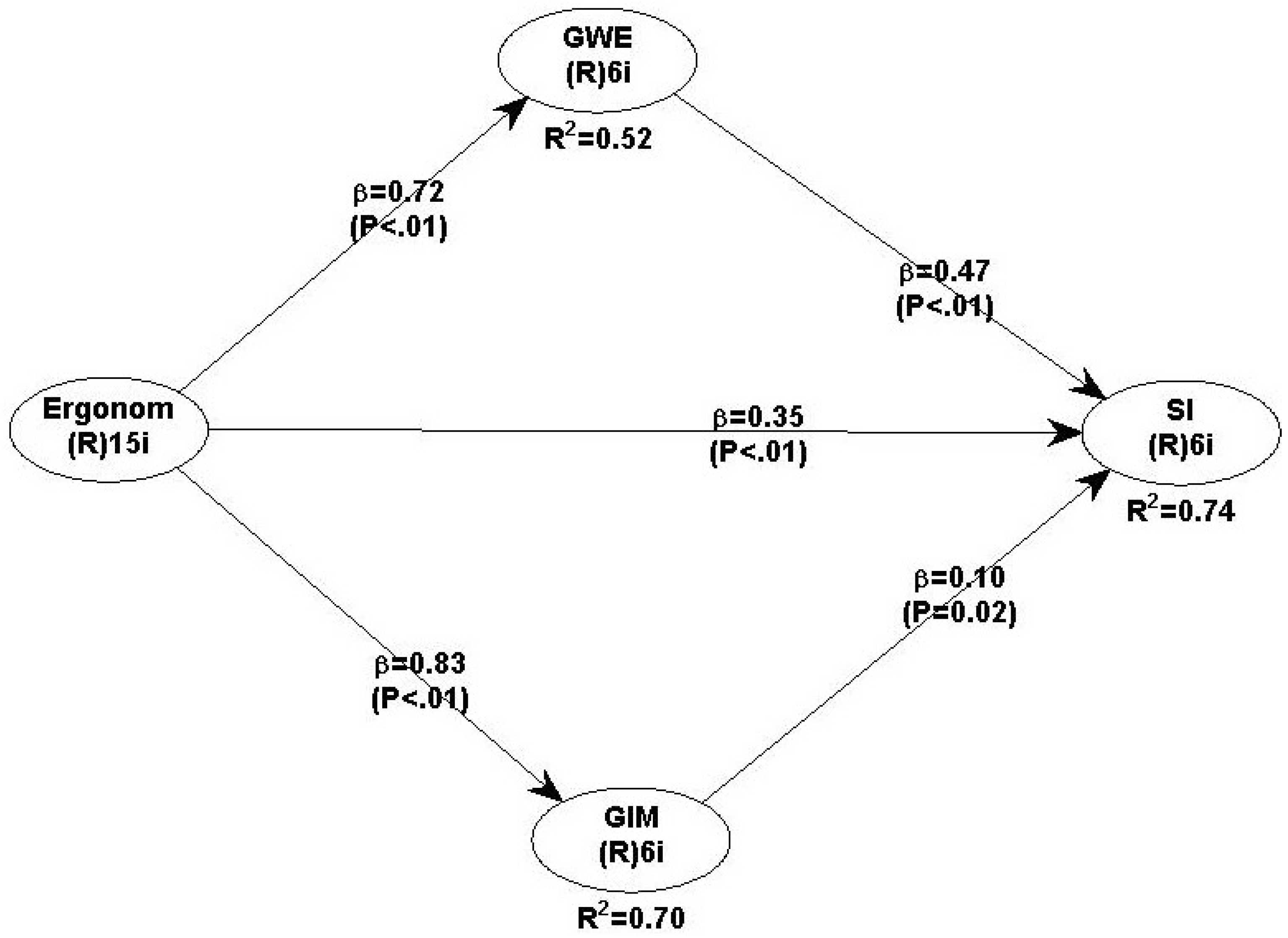

The conceptual framework of the study is presented in

Figure 1 below.

3. Methodology

3.1. Measures and Instrument Development

A quantitative research design was adopted, using a structured survey to collect the required data. The purpose of the survey was to examine ergonomics within the hospitality industry—specifically in five-star hotels—and to explore its effects on green work engagement, green intrinsic motivation, and sustainable innovation. The questionnaire was divided into two parts: the first included 33 items measuring the study’s latent variables, while the second contained 4 questions related to participants’ demographic and professional characteristics.

A self-administered questionnaire method was used for data collection. The initial survey was developed in English, after which a back-translation procedure was implemented to ensure linguistic accuracy and conceptual equivalence. First, a bilingual expert translated the English version into Arabic. Then, a second bilingual specialist translated the Arabic version back into English. The two English versions were compared to verify consistency. Because no discrepancies were identified, the Arabic version was selected for distribution to enhance clarity and improve response quality.

Ergonomics was measured using a tailored 15-item instrument adapted from

Coluci et al. (

2009). Sustainable innovation was evaluated using a 6-item scale based on

Delmas and Pekovic (

2018). Green intrinsic motivation was assessed using a six-item measure developed by

Li et al. (

2020), and green work engagement was examined using a 6-item scale proposed by

Aboramadan (

2022). Full measurement items are provided in

Appendix A.

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

The proposed research model was tested using data obtained from full-time employees working in five-star hotels in Egypt. This particular hotel category was chosen because it represents a major segment of the country’s hospitality industry. Moreover, five-star hotels frequently encounter difficulties in adopting sustainability practices, coordinating sustainability objectives among various stakeholders, and securing their commitment. The fragmented nature of the sector and the emphasis on short-term financial gains often hinder efforts to promote long-term environmental initiatives. At the outset, the study also included employees from travel agencies, as these organizations operate within the broader tourism and hospitality landscape. Travel agencies share similar service-oriented environments and face comparable ergonomic, environmental, and sustainability-related challenges, which justified their temporary inclusion.

According to

The Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (

2022), the Greater Cairo area has 30 five-star hotels. Owing to the large population size and limited research resources, a convenience sampling strategy was adopted, which is a common approach when probability sampling is not feasible. In total, 600 questionnaires were distributed across the selected establishments. Of these, 424 valid responses were received from 22 participating five-star hotels, resulting in a response rate of 70.7%.

Hair et al. (

2010) suggest determining sample size based on the number of measurement items, recommending a minimum ratio of 1:10. With 33 items included in the study, the minimum required sample size was 330 participants. Therefore, the final sample of 424 employees exceeded this threshold and was deemed adequate for statistical analysis.

3.3. Non-Response and Common Method Biases

The study showed that early and late respondents did not differ significantly, as the t-test results yielded p-values greater than 0.05. This outcome indicates that the timing of survey completion did not influence participants’ responses, and therefore non-response bias is unlikely to have affected the validity of the findings. In other words, the sample appears to represent the target population consistently across different response periods.

To further ensure the quality and reliability of the data, the study also examined the possibility of common method variance (CMV). Harman’s single-factor test, supported by principal component analysis, was applied as an initial diagnostic tool. The results demonstrated that no single factor accounted for more than half of the total variance, which suggests that the data were not overly influenced by a shared measurement method. This provides additional confidence that the relationships observed among the study variables are genuine rather than artifacts of the data collection procedure.

3.4. Data Analysis

The study utilized Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) with WarpPLS version 7.0. PLS-SEM was chosen due to its suitability for exploratory research and its ability to handle complex models with multiple mediating variables. This technique emphasizes maximizing the explained variance (R

2) of dependent constructs, making it particularly effective for predictive modeling. Moreover, PLS-SEM is robust to small to medium sample sizes and deviations from normality, characteristics consistent with the current dataset (

Sarstedt et al., 2021;

Hair et al., 2023). Its advantages in analyzing complex relationships make it an ideal approach for examining the proposed links among ergonomics, green work engagement, green intrinsic motivation, and sustainable innovation.

4. Results

4.1. Participant’s Profile

The study involved 424 participants.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the study participants across several categories: gender, age, education, experience, and work organization. Below is a breakdown of the data as presented in

Table 1:

Overall, most respondents were male, aged between 30 and 40, held a Bachelor’s degree, and had over 2 years of experience.

4.2. Measurement Model

The four-factor measurement model—including ergonomics, sustainable innovation (SI), green work engagement (GWE), and green intrinsic motivation (GIM)—was examined through confirmatory factor analysis to ensure that the constructs were distinct and statistically sound. To evaluate the adequacy of the model, the study relied on the ten model-fit indices proposed by

Kock (

2021). These indices include the Average Path Coefficient (APC), Average R-squared (ARS), and Average Adjusted R-squared (AARS), all of which should demonstrate significance at

p < 0.05. Additional criteria involve the Average Variance Inflation Factor (AVIF) and the Average Full Variance Inflation Factor (AFVIF), both considered acceptable when values are ≤5 and ideally below 3.3. Model adequacy was further assessed through the Goodness of Fit (GoF), where values of 0.1, 0.25, and 0.36 indicate small, medium, and large fit levels, respectively. Structural performance indices—SPR, RSCR, SSR, and NLBCDR—must meet threshold values of ≥0.7, with optimal performance at 1.0.

The computed indices demonstrated that the model met or exceeded all recommended benchmarks, confirming its robustness. Specifically, the results were APC = 0.497 (p < 0.001), ARS = 0.654 (p < 0.001), AARS = 0.653 (p < 0.001), AVIF = 2.893, AFVIF = 3.086, GoF = 0.635, SPR = 1.000, RSCR = 1.000, SSR = 1.000, and NLBCDR = 1.000. Collectively, these values indicate that the measurement model demonstrates strong internal consistency, structural validity, and overall model fit.

In addition, the research constructs showed strong composite reliability, with ratings exceeding the recommended threshold (CR > 0.70) and all item loadings being significant (>0.50,

p < 0.05), as highlighted in

Table 2. Some items exhibited factor loadings below the threshold of 0.70 but above 0.500. These items were retained because they are theoretically meaningful, contribute to the content validity of the constructs, and have been previously validated in the source scales. Retaining these items ensures that the constructs fully capture the conceptual domains of ergonomics, green work engagement, green intrinsic motivation, and sustainable innovation while maintaining the integrity of the measurement model. Additionally, the constructs—ergonomics, sustainable innovation, green work engagement, and green intrinsic motivation—had an Average Variance Extracted (AVE) value greater than 0.50, indicating adequate convergent validity. Furthermore, the model was deemed free from common method bias, as the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for each latent variable was ≤3.3.

The discriminant validity of the constructs was confirmed by ensuring that the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct was greater than the off-diagonal correlations (see

Table 3). Additionally, discriminant validity was further verified by calculating the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT), as shown in

Table 4.

4.3. Results of Testing Hypotheses

Figure 2 and

Table 5 illustrate that ergonomics has a positive impact on sustainable innovation (SI) (β = 0.35,

p < 0.01), green work engagement (GWE) (β = 0.72,

p < 0.01), and green intrinsic motivation (GIM) (β = 0.83,

p < 0.01). This indicates that improved ergonomics leads to higher SI, GWE, and GIM, thereby validating hypotheses H1, H2, and H5. Additionally, SI is significantly influenced by both GWE (β = 0.47,

p < 0.01) and GIM (β = 0.10,

p = 0.02), confirming that GWE and GIM contribute to the enhancement of SI, supporting hypotheses H3 and H6.

The mediation effects of GWE and GIM in the ergonomics → SI relationship were analyzed using the method proposed by

Preacher and Hayes (

2008). As shown in

Table 6, the indirect effects of GWE and GIM, with a 95% bootstrapped confidence interval (LL, UL), did not include zero in-between, indicating the presence of a significant mediation effect. Thus, the study confirmed that both GWE and GIM act as significant mediators in the relationship between ergonomics and SI, supporting hypotheses H4 and H7.

5. Discussion

This research seeks to explore the influence of ergonomics on sustainable innovation in the hospitality industry, emphasizing the roles of green work engagement and green intrinsic motivation as mediating factors. The theoretical model has been developed and tested. The findings indicate that ergonomics directly influences sustainable innovation, aligning with the results of studies conducted by

Hasanain (

2024). Incorporating ergonomics into the innovation process can also enhance collaboration and communication among employees (

Burke, 2020). Ergonomic design principles that encourage open, flexible workspaces promote teamwork and the exchange of ideas, which are vital for cultivating innovative thinking (

Mattarelli et al., 2024). When employees feel comfortable and supported in their environment, they are more likely to engage in collaborative efforts around sustainability initiatives, actively participating in the creative process. This leads to the development of innovative solutions that address both operational challenges and environmental issues (

Mitchell & Walinga, 2017;

Baldassarre et al., 2017).

The findings also show that ergonomics has a positive effect on green work engagement, consistent with the results of

Stack and Ostrom (

2023). By incorporating ergonomic design principles, organizations can create environments that not only enhance employee well-being but also cultivate a culture of green engagement and commitment to sustainability (

Thomas et al., 2024). As the demand for sustainable practices continues to rise, it will be crucial for organizations to understand and leverage the link between ergonomics and green work engagement to meet their environmental goals while simultaneously improving employee satisfaction and productivity (

Bolis et al., 2014). This synergy ultimately fosters a more sustainable and resilient workplace, empowering employees to make meaningful contributions to environmental stewardship (

Tosi & Tosi, 2020).

Additionally, the findings indicate that green work engagement positively affects sustainable innovation and serves as a mediator between ergonomics and sustainable innovation. These results are consistent with previous research by

Khan et al. (

2024),

Ajayi and Udeh (

2024) and

Stack and Ostrom (

2023). Organizations that promote green work engagement are also better equipped to adapt to evolving market demands and regulatory pressures related to sustainability. Engaged employees tend to be more aware of trends and advancements in environmental practices, allowing the organization to proactively address emerging challenges and opportunities (

Ababneh, 2021;

Casey & Sieber, 2016). As consumer priorities increasingly shift toward sustainability, organizations with committed employees dedicated to green initiatives can more effectively innovate to align with these changing expectations. This agility not only boosts the organization’s competitive edge but also reinforces its reputation as a leader in sustainable practices, attracting customers and partners who prioritize environmental responsibility (

Quinn & Dalton, 2009;

Ahsan, 2024). Moreover, the mediating influence of green work engagement also underscores the feedback loop linking ergonomics, employee engagement, and sustainable innovation. As organizations recognize the positive effects of ergonomics on green work engagement, they are likely to further invest in ergonomic enhancements, creating a virtuous cycle (

Ahsan, 2024). Employees actively engaged in sustainability initiatives often provide valuable insights regarding ergonomic designs, proposing improvements that can further bolster their work conditions. This iterative process facilitates continuous advancements in both ergonomic practices and sustainability efforts, cultivating a culture of innovation that responds effectively to employee needs and environmental challenges (

Norton et al., 2021;

Thomas et al., 2024). By comprehending and leveraging this mediating relationship, organizations can improve their overall sustainability performance, ensuring that ergonomics and employee engagement are strategically aligned with their innovation objectives (

Stack & Ostrom, 2023;

Tosi & Tosi, 2020).

Furthermore, the findings indicate that ergonomics has a positive effect on green intrinsic motivation, which aligns with the research of

Al-Romeedy et al. (

2025). Ergonomic design can significantly impact the cognitive processes that drive intrinsic motivation. Comfortable workspaces encourage employees to engage in creative thinking and problem-solving, which are crucial for innovation. This cognitive flexibility allows employees to brainstorm and develop new ideas for sustainable practices within the organization (

Tosi & Tosi, 2020). An ergonomically optimized workspace not only fosters critical thinking about waste reduction, energy efficiency, or sustainable sourcing practices (

Norton et al., 2021) but also amplifies employees’ involvement in these initiatives, further enhancing their intrinsic motivation. As they become more engaged, they begin to view themselves as agents of change within the organization, which intensifies their commitment to achieving environmental goals (

Afsar et al., 2016;

Heucher et al., 2024).

Finally, the findings demonstrate that green intrinsic motivation positively affects sustainable innovation and acts as a mediator between ergonomics and sustainable innovation. These results are consistent with the studies conducted by

Ashraf et al. (

2024),

Hasanain (

2024), and

Meng et al. (

2024). Organizations that actively nurture green intrinsic motivation among their workforce often see heightened employee satisfaction and retention. When employees perceive a strong alignment between their values and those of the organization, they are more likely to feel fulfilled and engaged in their roles. This boost in job satisfaction can lead to lower turnover rates, allowing organizations to retain talented individuals who are passionate about sustainability and innovation (

Aljumah, 2023;

Fawcett et al., 2008;

Jibril & Yeşiltaş, 2022). The continuity of these motivated employees further enhances the organization’s capacity for sustainable innovation, as they can leverage their existing knowledge and relationships to develop more effective and innovative solutions over time (

Lopes et al., 2017;

Holbeche, 2015). Moreover, the long-term impact of green intrinsic motivation on sustainable innovation cannot be overlooked. As employees become more engaged and motivated to pursue environmentally friendly practices, they may take the initiative to seek further education and training related to sustainability. This pursuit of knowledge can lead to the adoption of new technologies and practices that drive innovation (

Tosi & Tosi, 2020). An employee motivated by sustainability might attend workshops on sustainable design or research emerging trends in eco-friendly materials, subsequently sharing this knowledge with their colleagues. This continuous learning and improvement cycle can significantly enhance the organization’s capacity for sustainable innovation, as employees are empowered to explore and implement cutting-edge solutions (

Casey & Sieber, 2016;

Faulks et al., 2021).

Moreover, to enhance the generalizability of these findings, it is important to acknowledge that the model should be validated in different cultural contexts, across various types of hotel organizations, and in hospitality settings with diverse operational structures. Future studies could also extend the model to other service-intensive industries to examine whether the influence patterns identified in this research hold consistently across sectors.

6. Theoretical Implications

The insights gained from examining the interplay between ergonomics, sustainable innovation, green work engagement, and green intrinsic motivation offer substantial contributions to SDT. They provide concrete evidence of how external influences can bolster intrinsic motivation and subsequently stimulate innovative behaviors. According to SDT, intrinsic motivation thrives when individuals feel a sense of autonomy, competence, and connection with others. In this framework, ergonomics is pivotal as it addresses both the physical and psychological needs of employees, creating an environment that nurtures intrinsic motivation. Workspaces that are thoughtfully designed to be ergonomic alleviate physical discomfort and cognitive burdens, thereby enhancing employees’ feelings of competence and autonomy. This improved experience cultivates intrinsic motivation that resonates with their commitment to sustainability, encouraging them to become more actively involved in green initiatives and innovative practices. By illustrating how ergonomic principles can bolster these motivational factors, the findings emphasize the significance of environmental design in influencing employee engagement and the outcomes of innovation. This effectively broadens the application of SDT within the context of organizations, highlighting the necessity for businesses to create ergonomic work environments that not only support employee well-being but also drive sustainable innovation. Moreover, the study’s results also align with the broader assumptions of Innovation Theory, which emphasizes the importance of supportive structures, resourceful environments, and enabling work conditions in stimulating innovative outcomes. The integration of Innovation Theory provides an additional organizational-level explanation for why ergonomic environments facilitate sustainable innovation, complementing SDT’s focus on internal motivational mechanisms. By acknowledging both the psychological processes highlighted by SDT and the structural enablers emphasized in Innovation Theory, the findings offer a more comprehensive theoretical account of how ergonomic improvements activate both intrinsic motivation and organizational conditions conducive to sustainable innovation.

Furthermore, recognizing green work engagement and green intrinsic motivation as mediators in the relationship between ergonomics and sustainable innovation provides a deeper insight into how these motivational elements interact with ergonomic conditions to foster innovative outcomes. Green work engagement, defined as an employee’s active participation in sustainability efforts, is significantly shaped by the ergonomic features of their workspace. When employees experience comfort and support in their environment, they are more inclined to channel their efforts into green initiatives, effectively transforming their intrinsic motivation into concrete actions. This connection aligns with the principles of SDT, which posits that environmental and contextual factors can influence motivation levels and the resulting behaviors. The findings highlight that when organizations prioritize ergonomic design, they establish a conducive environment for nurturing green work engagement, ultimately driving enhanced sustainable innovation. This mediating effect underscores the notion that intrinsic motivation is not merely an individual trait but is also profoundly affected by organizational practices and environmental conditions. Additionally, Innovation Theory reinforces this view by suggesting that employee engagement in innovative and sustainability-oriented behaviors emerges most strongly when both psychological readiness (as explained by SDT) and organizational support systems coexist. Thus, the mediation patterns revealed in this study illustrate how ergonomic design simultaneously nurtures personal motivation and strengthens organizational foundations that encourage sustainability-driven innovation.

Moreover, the findings clarify the crucial role of green intrinsic motivation in promoting sustainable innovation. As employees grow more intrinsically motivated to participate in eco-friendly practices, their capacity for sustainable innovation significantly increases. This link between intrinsic motivation and innovation is vital for organizations aiming to cultivate a sustainability-oriented culture. When employees are inspired by their values and beliefs regarding sustainability, they are more inclined to recognize and suggest innovative solutions that align with the organization’s sustainability objectives. The evidence showing that green work engagement and green intrinsic motivation positively influence sustainable innovation expands the principles of SDT by illustrating how motivation grounded in personal values can lead to meaningful outcomes for the organization. This insight is further strengthened by Innovation Theory, which posits that employees are more likely to convert their internal motivation into innovative behaviors when the work environment provides the necessary resources, flexibility, and structural support. Together, SDT and Innovation Theory explain how intrinsic values and organizational enablers jointly shape employees’ contributions to sustainable innovation.

Additionally, by highlighting the mediating roles of green work engagement and green intrinsic motivation, the findings demonstrate how motivation acts as a connector between ergonomic practices and sustainable innovation. This mediation underscores the significance of creating an environment that nurtures both ergonomic principles and intrinsic motivation. Organizations that emphasize ergonomic design not only improve employee comfort and well-being but also foster conditions that promote greater involvement in sustainability efforts. By recognizing these relationships, organizations can devise targeted strategies to utilize ergonomic enhancements to strengthen green intrinsic motivation and engagement, ultimately advancing sustainable innovation. This relationship reinforces the SDT concept that well-structured environments can boost intrinsic motivation, leading to heightened engagement and innovative actions aligned with sustainability goals. At the same time, Innovation Theory adds an important layer by indicating that such structured ergonomic environments also serve as organizational catalysts that trigger creative problem-solving and sustainability-oriented innovation. The combined theoretical perspectives demonstrate that ergonomic design simultaneously satisfies psychological needs and provides the operational conditions required for innovation, offering a dual-path explanation for the emergence of sustainable innovation in the hospitality sector.

7. Practical Implications

To improve ergonomics, green work engagement, and green intrinsic motivation, hotel businesses should implement a holistic strategy that integrates these elements into their organizational culture and practices. By prioritizing these areas, hotels can cultivate a sustainable and innovative environment that benefits both employees and guests, ultimately enhancing operational performance and competitive advantage. Firstly, hotels should perform comprehensive assessments of their work environments to identify ergonomic challenges faced by staff. This includes evaluating workstations, equipment, and overall design to ensure they align with the physical and cognitive needs of employees. For instance, in housekeeping, using ergonomically designed cleaning tools and equipment can help minimize physical strain and reduce the risk of injury. Similarly, adjustable workstations in administrative areas can accommodate diverse body types and preferences. Additionally, implementing ergonomic training programs can boost employee awareness of best practices, empowering them to adopt strategies that promote comfort and health. Such investments can lead to greater employee satisfaction and productivity while reducing absenteeism and turnover, resulting in a more stable and experienced workforce.

To foster green work engagement, hotels should make sustainability a central component of their operations and employee responsibilities. This can be achieved by setting clear sustainability goals and actively involving employees in reaching these objectives. For example, hotels can establish green teams made up of staff from various departments to design and implement sustainability initiatives, such as reducing energy consumption, minimizing waste, or improving recycling efforts. By encouraging employees to take ownership of these initiatives, hotels can nurture a culture of engagement and shared responsibility, motivating staff to participate actively in sustainability efforts. Furthermore, regularly recognizing and celebrating employees’ contributions to green initiatives can enhance this engagement, reinforcing the notion that sustainability is a collective endeavor that benefits everyone within the organization.

Further, to boost green intrinsic motivation among employees, hotel businesses need to cultivate an organizational culture that reflects their values and objectives. This process starts with instilling a sense of purpose by clearly articulating the significance of sustainability within the organization’s mission and vision. When employees grasp how their roles contribute to overarching sustainability goals, they are more likely to feel driven to adopt environmentally friendly practices. Additionally, offering personal development opportunities, such as workshops and training on sustainability topics, can further enhance employees’ intrinsic motivation. These programs empower staff to broaden their knowledge and skills related to sustainability, making them feel competent in effecting positive change in their roles. Promoting open dialog and feedback regarding sustainability initiatives can also strengthen the sense of connection among employees, reinforcing their commitment to green practices.

Establishing regular feedback mechanisms is essential for enhancing ergonomics, green work engagement, and green intrinsic motivation. Hotels should create channels for employees to express their experiences, concerns, and suggestions regarding ergonomic practices and sustainability initiatives. This could include surveys, focus groups, or suggestion boxes designed to encourage open communication. By actively soliciting and acting on employee feedback, hotel management demonstrates a commitment to continuous improvement, fostering a workplace environment that values employee input and engagement. This two-way communication builds trust and collaboration, allowing employees to feel more connected to their organization and its sustainability objectives.

Finally, hotel businesses should ensure that their ergonomic initiatives are aligned with broader sustainability goals to develop a cohesive strategy. For example, when choosing materials for renovations or new constructions, hotels can prioritize products that are both sustainable and ergonomic, enhancing employee comfort while supporting environmental sustainability. Likewise, implementing energy-efficient lighting and climate control systems can improve working conditions for employees and reduce the hotel’s ecological footprint. By integrating ergonomic considerations into their sustainability strategies, hotels can create synergies that benefit both employees and the environment, leading to innovative solutions that promote sustainable innovation.

8. Limitations and Future Research

Although the exploration of ergonomics and sustainable innovation in hotel businesses, particularly through the framework of green work engagement and green intrinsic motivation, offers valuable insights, several limitations warrant acknowledgment. These limitations underscore the necessity for further research to enhance our understanding of these intricate relationships and their implications for the hospitality sector. A notable limitation of the current study is its dependence on self-reported data, which can introduce biases such as social desirability and recall bias. Participants may exaggerate their involvement in sustainable practices or their levels of intrinsic motivation, potentially skewing the results. To mitigate this issue, future research should adopt a mixed-methods approach that integrates both qualitative and quantitative data collection. For instance, including observational studies could provide more objective metrics of employee behavior and performance indicators that monitor actual participation in sustainability initiatives over time. By capturing both self-reported perceptions and objective data, researchers can gain a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between ergonomics and sustainable innovation.

The study primarily concentrated on short-term outcomes associated with ergonomics and sustainability initiatives, possibly overlooking long-term effects. It is essential to determine whether initial boosts in employee motivation and engagement lead to sustained changes in behavior and innovation. Future research should utilize longitudinal designs to examine the impact of ergonomic enhancements and green engagement over extended periods. By tracking changes in employee motivation, engagement, and sustainability practices over time, researchers can gain deeper insights into the causal relationships and the conditions that foster enduring behavioral change within hotel businesses. Additionally, the current study did not adequately consider contextual factors that can influence the effectiveness of ergonomics and sustainability initiatives, such as organizational culture, leadership styles, and available resources. These elements can play a significant role in shaping employee engagement and motivation. Future research should investigate how these contextual variables interact with ergonomic practices and sustainability efforts. For example, studying the influence of green transformational leadership on fostering a culture of sustainability could shed light on how organizational dynamics affect employee motivation. Understanding these interactions will enable hotels to develop targeted strategies that effectively enhance ergonomics and promote sustainable innovation.

In addition, future research should examine potential moderating variables that were not considered in the current study but may significantly influence the strength or direction of the identified relationships. Examples include sustainability training policies, job stability, access to green technologies, and key organizational factors such as hotel size and corporate culture. Demographic characteristics—such as education level, tenure, and age—may also moderate the effects of ergonomics on motivation and innovation. Exploring these moderators would allow for a more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms underlying sustainable innovation and would further enhance the transferability and robustness of the proposed model across different organizational and workforce profiles.

Furthermore, although sustainable innovation is recognized as a complex, multidimensional construct, the present study employed a unidimensional measure adapted from

Delmas and Pekovic (

2018). This approach allowed us to capture organizations’ overall environmentally oriented innovation efforts in a parsimonious manner suitable for the study’s broader mediation model. However, using a general measure may limit the ability to distinguish how ergonomics influences specific types of innovation (e.g., product, process, organizational, or marketing innovations). Future studies are encouraged to employ multidimensional or higher-order conceptualizations of sustainable innovation to provide more granular insights into how different innovation domains respond to ergonomic practices.

Finally, the generalizability of the findings is limited by the fact that data were collected from a single cultural context and from one category of hotel organizations. Future studies should validate the model across different cultural environments and across diverse types of hotels, including international chains, boutique hotels, and budget accommodations. Researchers may also extend the examination of the model to other service-intensive sectors such as restaurants, airlines, healthcare, and education to assess whether the influence patterns identified here remain consistent. Employing multi-group or cross-cultural comparative analyses would further strengthen the external validity of the model and provide deeper insights into how cultural and sectoral differences shape the relationships among ergonomics, motivation, and sustainable innovation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.H., B.S.A.-R., N.A. and H.A.K.; methodology, H.A.K.; software, H.A.K.; validation, A.M.H., B.S.A.-R., N.A. and H.A.K.; formal analysis, H.A.K.; investigation, B.S.A.-R., N.A. and H.A.K.; resources, B.S.A.-R. and A.M.H.; data curation, B.S.A.-R., N.A. and H.A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.H., B.S.A.-R., N.A. and H.A.K.; writing—review and editing, A.M.H., B.S.A.-R., N.A. and H.A.K.; visualization, A.M.H. and B.S.A.-R.; supervision, H.A.K. and B.S.A.-R.; project administration, H.A.K. and N.A.; funding acquisition, N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia, grant number [KFU253910].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Deanship of Scientific Research Ethical Committee, King Faisal University (Approval Code KFU253910), with the approval granted on 1 January 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from researchers who meet the eligibility criteria. Kindly contact the first author privately through e-mail.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Detailed measurement scale items.

Table A1.

Detailed measurement scale items.

| Ergonomics-Related Job Factors | Coluci et al. (2009) |

| Ergo.1. Performing a broad selection of tasks across the workday. |

| Ergo.2. Undertaking prolonged activities at a slower tempo (such as lifting, grasping, or pulling). |

| Ergo.3. Having no requirement to manage or manipulate oversized items. |

| Ergo.4. Receiving sufficient intervals for rest throughout the shift. |

| Ergo.5. Carrying out duties in positions that offer physical ease and adequate space. |

| Ergo.6. Frequently alternating between short-duration postures (standing, bending, sitting, kneeling, and similar). |

| Ergo.7. Maintaining a naturally aligned and comfortably upright back position. |

| Ergo.8. Performing tasks that remain well within one’s physical limits. |

| Ergo.9. Conducting work that can be reached easily and kept close to the body. |

| Ergo.10. Working in environments with moderate, cool, and dry conditions that promote comfort. |

| Ergo.11. Handling, lifting, or transporting materials or equipment of light weight. |

| Ergo.12. Taking necessary leave to recuperate following injury or physical strain. |

| Ergo.13. Benefiting from adaptable scheduling that ensures reasonable hours and balanced workloads. |

| Ergo.14. Using ergonomically designed tools that are comfortable, light, and low in vibration. |

| Ergo.15. Performing duties with access to thorough training and continuous support. |

| Green intrinsic motivation | Li et al. (2020) |

| GIM.1. I enjoy creating new environmentally friendly ideas. |

| GIM.2. I like working on environmental tasks at my job. |

| GIM.3. I enjoy taking on environmental tasks that are completely new to me. |

| GIM.4. I like improving or refining existing green ideas at work. |

| GIM.5. I feel excited when I come up with new green ideas. |

| GIM.6. I want to be more involved in developing green ideas. |

| Green Work Engagement | Aboramadan (2022) |

| GWE.1. My environmentally focused tasks motivate and inspire me. |

| GWE.2. I feel proud of the environmental work I perform. |

| GWE.3. I become fully absorbed in my environmental duties. |

| GWE.4. I feel enthusiastic about the environmental tasks I handle at work. |

| GWE.5. I feel happy when I am deeply engaged in environmental tasks. |

| GWE.6. I feel energized and full of vitality when working on environmental tasks. |

| Sustainable innovation (SI) | Delmas and Pekovic (2018) |

| SI.1. My organization has implemented product, process, organizational, or marketing innovations that lower the amount of materials and resources used per unit of output. |

| SI.2. My organization has adopted innovations in products, processes, organization, or marketing that reduce energy consumption. |

| SI.3. My organization has introduced innovations that help decrease carbon dioxide emissions. |

| SI.4. My organization has developed innovations that replace existing materials with less harmful or less polluting alternatives. |

| SI.5. My organization has implemented innovations that help reduce pollution in soil, water, air, or noise levels. |

| SI.6. My organization has adopted innovations that support the recycling of waste, water, or materials. |

References

- Ababneh, O. (2021). How do green HRM practices affect employees’ green behaviors? The role of employee engagement and personality attributes. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 64(7), 1204–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A., Al Abdulathim, M., Hussni Hasan, N., Salah, M., Ali, H., & Kamel, N. (2023). From green inclusive leadership to green organizational citizenship: Exploring the mediating role of green work engagement and green organizational identification in the hotel industry context. Sustainability, 15(20), 14979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M. (2022). The effect of green HRM on employee green behaviors in higher education: The mediating mechanism of green work engagement. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 30(1), 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiga, U. (2023). Enhancing occupational health and ergonomics for optimal workplace well-being: A review. International Journal of Chemical and Biochemical Sciences, 24(4), 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Afsar, B., Badir, Y., & Kiani, U. (2016). Linking spiritual leadership and employee pro-environmental behavior: The influence of workplace spirituality, intrinsic motivation, and environmental passion. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B., Maqsoom, A., Shahjehan, A., Afridi, S., Nawaz, A., & Fazliani, H. (2020). Responsible leadership and employee’s proenvironmental behavior: The role of organizational commitment, green shared vision, and internal environmental locus of control. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(1), 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P., & Agarwala, T. (2023). Relationship of green human resource management with environmental performance: Mediating effect of green organizational culture. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 30(7), 2351–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N., Samad, S., & Han, H. (2024). Charting new terrains: How CSR initiatives shape employee creativity and contribute to UN-SDGs in a knowledge-driven world. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 9(4), 100557. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, M. (2024). Unlocking sustainable success: Exploring the impact of transformational leadership, organizational culture, and CSR performance on financial performance in the Italian manufacturing sector. Social Responsibility Journal, 20(4), 783–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, F., & Udeh, C. (2024). Agile work cultures in IT: A Conceptual analysis of HR’S role in fostering innovation supply chain. International Journal of Management & Entrepreneurship Research, 6(4), 1138–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Husain, R. A., Jasim, T. A., Mathew, V., Al-Romeedy, B. S., Khairy, H. A., Mahmoud, H. A., Liu, S., El-Meligy, M. A., & Alsetoohy, O. (2025). Optimizing sustainability performance through digital dynamic capabilities, green knowledge management, and green technology innovation. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 24217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljumah, A. (2023). The impact of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on job satisfaction: The mediating role of transactional leadership. Cogent Business & Management, 10(3), 2270813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnasser, E. M., Alkhozaim, S. M., Alshiha, A. A., Al-Romeedy, B. S., & Khairy, H. A. (2025). Intellectual capital and organisational resilience in tourism and hotel businesses: Do organisational agility and innovation matter? Current Issues in Tourism, 28(16), 2649–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Romeedy, B. S., Khairy, H. A., Abdelrahman Farrag, D., Alhemimah, A., Salameh, A. A., Gharib, M. N., & Fathy Agina, M. (2025). Green inclusive leadership and employees’ green behavior in tourism and hospitality businesses: Do green psychological climate and green psychological empowerment matter? Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arici, H., & Uysal, M. (2022). Leadership, green innovation, and green creativity: A systematic review. The Service Industries Journal, 42(5–6), 280–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S., Ali, S., Khan, T., Azam, K., & Afridi, S. (2024). Fostering sustainable tourism in Pakistan: Exploring the influence of environmental leadership on employees’ green behavior. Business Strategy & Development, 7(1), e328. [Google Scholar]

- Baldassarre, B., Calabretta, G., Bocken, N., & Jaskiewicz, T. (2017). Bridging sustainable business model innovation and user-driven innovation: A process for sustainable value proposition design. Journal of Cleaner Production, 147, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, B., Milhem, M., Naji, G., Alzoraiki, M., Muda, H., Ateeq, A., & Abro, Z. (2023). Assessing the impact of green training on sustainable business advantage: Exploring the mediating role of green supply chain practices. Sustainability, 15(19), 14144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, S., Ashfaq, M., Xia, E., & Awan, U. (2022). Does green transformational leadership lead to green innovation? The role of green thinking and creative process engagement. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(1), 580–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, J., & Aggarwal, P. (2020). Meaningful work as a mediator between perceived organizational support for environment and employee eco-initiatives, psychological capital and alienation. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(6), 1487–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolis, I., Brunoro, C., & Sznelwar, L. (2014). Mapping the relationships between work and sustainability and the opportunities for ergonomic action. Applied Ergonomics, 45(4), 1225–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolis, I., Sigahi, T., Thatcher, A., Saltorato, P., & Morioka, S. (2023). Contribution of ergonomics and human factors to sustainable development: A systematic literature review. Ergonomics, 66(3), 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P., Von Daniels, C., Bocken, N., & Balkenende, A. (2021). A process model for collaboration in circular oriented innovation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 286, 125499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]