Abstract

This study examines how psycholinguistic features of online reviews relate to guest satisfaction in Bali’s spa hotel market. Using LIWC-22 category rates from Google Maps reviews, a corpus of 15,560 quality-filtered reviews from ten leading spa hotels was analyzed. Exploratory factor analysis yielded four interpretable dimensions—Social, Health and Wellness, Emotional Tone, and Lifestyle. In regressions predicting review star ratings (satisfaction), Social (β = 0.028) and Health and Wellness (β = 0.023) showed small but statistically detectable positive associations, whereas Emotional Tone (β = 0.006, t = 0.727) and Lifestyle (β = 0.004, t = 0.476) were not significant. The model’s explained variance is negligible (R2 = 0.001; F = 5.283, p < 0.05), reflecting the many influences on ratings beyond review language; findings are interpreted as directional associations rather than predictive effects. Practically, the results point to prioritizing interpersonal service cues and wellness/treatment assurances, with tone monitoring being used for service-recovery signals. The design favors interpretability (validated, word-based categories; full-history snapshot) over black-box complexity, and transferability is Bali-specific and conditional on comparable market features. Future work should add contextual covariates (e.g., price and location), apply explicit temporal segmentation, extend to multilingual corpora, and triangulate text analytics with brief questionnaires and qualitative inquiry to strengthen validity and explanatory power.

1. Introduction

Wellness tourism has rebounded strongly since the pandemic, with global spending rising from USD 651 billion in 2022 to USD 868 billion in 2023 (). Within this recovery, the spa industry, which is known as a high-touch segment, has changed from USD 114 billion in 2019 to USD 70 billion in 2020, before recovering to USD 104.5 billion in 2022 (≈22% annual growth; 92% of its 2019 size). There are now 181,175 spas worldwide, and hotel/resort spas lead the category in both revenue (UDS 49 billion) and footprint (≈80,423 establishments) ().

Against this backdrop, Bali’s market scale and recovery justify its selection as a wellness destination case. International arrivals reached ≈6.28 million in 2019, plunged during 2020–2021, and rebounded to ≈5.6 million in 2024 (≈6% year-on-year growth), alongside ≈9.88 million domestic trips in 2023 according to Badan Pusat Statistik Bali (BPS Bali), which is also known as Bali’s Central Bureau of Statistics (). These volumes underscore the managerial importance of spa hotel experience quality during recovery, positioning Bali as a premier luxury wellness destination for relaxation, rejuvenation, and culture-rich spa experiences. Within this resurgence, spa hotels have played a central role by offering integrated wellness programs, premium treatments, and high-end accommodation. The Indonesian Hotel and Restaurant Association (PHRI) reported the registration of 179 spa businesses in 2023, of which approximately 60% (around 107 establishments) operate within hotel settings, while the remainder function as independent entities (). Beyond volume, Bali’s wellness positioning is internationally recognized—it was named as Asia’s Best Spa Destination from 2019 to 2021 consecutively and has been nominated for the best spa destination in 2025—which, together with its dense hotel-embedded spa supply, makes it a compelling and generalizable case for this study ().

The proliferation of digital platforms and online review ecosystems has profoundly influenced consumer decision-making in the hospitality industry. According to (), 93% of global travelers consult online reviews before booking, while nearly 80% consider review scores to be a decisive factor (). In this context, spa hotels—positioned within the sensitive luxury wellness segment—are especially susceptible to reputational dynamics shaped by user-generated content (UGC). Simultaneously, guest experiences are increasingly mediated by algorithmic personalization and data-driven service enhancements. () emphasize that spatial and contextual insights derived from guest feedback significantly influence satisfaction, especially when services are tailored to localized preferences. For spa hotels, the integration of big data analytics offers strategic value by revealing emerging trends, streamlining operations, and customizing services to diverse guest expectations.

In this digital environment, managing online reputation has become essential for spa hotels striving to enhance guest experience, foster brand loyalty, and sustain a competitive edge (; ). A strong digital reputation not only attracts new clientele but also builds trust among existing guests, while negative reviews can damage business outcomes. Analyzing large-scale review data—such as from Google Reviews—enables hotel operators to extract actionable insights on guest sentiment, service expectations, and experience quality ().

Existing research confirms that online reviews are now central to evaluating guest experiences in hospitality, particularly within luxury wellness settings (). Such reviews provide meaningful insights into perceived service quality, value, and emotional satisfaction (; ). Moreover, studies have shown that sentiment-laden reviews strongly correlate with guest experience, underscoring the importance of data-informed marketing and personalized service strategies (; ). Cultural differences between domestic and international guests further shape review content, highlighting the need to consider localized perspectives in service refinement ().

In light of these trends, spa hotels in Bali are urged to implement big data analytics to manage digital reputation, fine-tune services, and personalize the guest journey. The literature suggests that such data-driven strategies not only optimize operational performance but also reinforce guest engagement and loyalty (; ). As the hospitality industry evolves toward a more personalized and feedback-oriented paradigm, data capabilities have become indispensable.

This study aims to examine how guest experiences and reputational perceptions of Bali’s spa hotels are manifested in the tone and language of online reviews. LIWC-22 is adopted because its validated word-category system (affect; social; body/perceptual; cognitive processes) directly operationalizes constructs central to wellness experience theory (hedonic/eudaimonic well-being) and to service quality/customer satisfaction frameworks (e.g., SERVQUAL; expectation–confirmation), where affect indexes capture hedonic tone; body/perceptual terms map the embodied and sensory dimensions of spa treatments; social/affiliation language reflects empathy, assurance, and responsiveness in service encounters; and cognitive process markers (e.g., insight, causation, and discrepancy) mirror appraisal and (dis)confirmation mechanisms that precede satisfaction and loyalty intentions (; ). Leveraging LIWC-22, a psycholinguistic analysis tool, this research analyzes large volumes of user-generated content to identify emotional and cognitive dimensions of guest feedback (). By employing this approach, the study offers evidence-based insights to inform service innovation and enhance reputation management in the luxury wellness tourism sector.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Wellness Tourism

Wellness tourism is defined as travel associated with the pursuit of maintaining or enhancing one’s personal well-being. It encompasses a range of services such as spa treatments, fitness activities, nutrition-focused programs, and spiritual retreats. According to the (), wellness tourism accounted for over USD 720 billion in global expenditure prior to the pandemic and is expected to rebound and grow significantly in the coming years. Bali, in particular, has distinguished itself as a global wellness destination due to its cultural richness, natural beauty, and integration of traditional therapies. Scholars such as () have emphasized that wellness tourists seek more than relaxation—they pursue transformative experiences that connect the body, mind, and spirit. This highlights the importance of spa hotels not just as lodging facilities, but as holistic providers of health-focused lifestyle services.

Moreover, wellness tourism is closely tied to the quality of guest experience and personalization. () argue that success in wellness hospitality relies on aligning services with the psychological and emotional expectations of guests. This includes incorporating local cultural elements and responding to evolving lifestyle trends. Recent studies have noted the increasing sophistication of wellness tourists, who now demand evidence-based treatments, eco-conscious design, and personalized care (). These expectations raise the standard for spa hotel operations, pushing businesses to innovate beyond conventional offerings. In a competitive environment such as Bali, where spa experiences are widely available, guest satisfaction and service differentiation become central to long-term sustainability.

2.2. Reputation and Guest Experience

In hospitality, guest experience is a multidimensional construct encompassing service quality, emotional fulfillment, and perceived value. Reputation, meanwhile, is the collective perception formed through repeated guest experiences and their public expression—most notably via online reviews. According to (), potential guests are significantly influenced by other travelers’ narratives, often trusting peer-generated reviews over official marketing messages. () further notes that online reviews affect not only booking intentions but also brand trust and loyalty. Particularly in wellness tourism, where emotional satisfaction plays a critical role, reputation is not merely a marketing concern but a strategic asset. Negative reviews can be especially damaging due to the subjective and intimate nature of wellness experiences.

The language and emotional tone used in reviews offer deeper insight into guest experiences. () demonstrated that the perceived authenticity and emotional expressiveness of a review significantly affect its impact on readers. In the context of spa hotels, this means that the words guests choose to describe their stay—whether focused on relaxation, empathy, or disappointment—can shape the reputation of the establishment. () emphasized that wellness-oriented reviews tend to carry stronger affective content than general hotel reviews, indicating a higher degree of emotional investment by guests. Thus, understanding and managing guest language in reviews becomes essential for hotels aiming to enhance satisfaction and maintain a favorable reputation in the luxury wellness sector.

2.3. Big Data in Tourism

The rise in big data has transformed how tourism firms generate insight and make decisions. With the proliferation of online reviews, booking systems, and social media, large volumes of unstructured text now capture travelers’ perceptions on such a scale. Big data approaches enable firms to understand preferences, predict demand, and optimize service delivery (). In hospitality industry and especially in wellness tourism where experiences are inherently subjective, text analytics complements traditional surveys by revealing emotional nuance and service cues embedded in guest narratives. Accordingly, natural language processing (NLP) and text mining are increasingly used to extract themes and satisfaction drivers from review content.

A prominent psycholinguistic tool for this purpose is LIWC (Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count). Originally developed by Pennebaker and colleagues, LIWC classifies words into validated psychological categories such as affect, social, body/perceptual, and cognitive processes (). LIWC-22 is well-suited to luxury wellness settings because its categories align with constructs central to wellness experience theory and service quality/customer satisfaction, where affect indexes capture hedonic tone; body/perceptual terms reflect the sensory and embodied dimensions of spa treatments; social language signals empathy, assurance, and responsiveness in service encounters; and cognitive process markers (e.g., insight, causation, and discrepancy) mirror appraisal and expectation–confirmation mechanisms that precede satisfaction and loyalty (; ). Recent tourism studies have successfully applied LIWC to user-generated content to detect psycholinguistic shifts and managerial levers, demonstrating its capacity to move beyond star ratings to interpretable, theory-linked indicators (; ). Thus, in this study, LIWC-22 category rates serve as theory-anchored inputs that are aggregated via factor analysis and tested in regression models with controls, providing transparent, decision-ready evidence for luxury wellness hospitality.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

This study investigates the relationship between guest experience and online reputation in the context of Bali’s spa hotel sector by leveraging large-scale user-generated reviews sourced from Google Maps (). The top ten spa resorts included in this study were selected based on Tripadvisor’s ‘Best Value’ rankings, which are determined using exclusive data such as traveler ratings, confirmed availability from partners, pricing, booking popularity, location, personal user preferences, and recently viewed hotels (). Based on previous studies, a dataset comprising reviews from ten hotels is considered sufficient for big data analysis, with some studies even employing fewer hotels (; ). Selecting ten market-leading spa hotels focuses the analysis on a comparable set of high-salience accommodation and prevents the dataset from becoming overly broad and heterogeneous. These hotels are The Kayon Jungle Resort, Padma Resort Ubud, The Alena Resort A Pramana Experience, Adiwana Bisma, Adiwana Unagi Suites, Kuta Seaview Boutique Resort, Ramayana Suites & Resort, Artotel Sanur Bali, Ayodya Resort Bali, and Adiwana Resort Jembawan. These establishments represent a cross-section of Bali’s luxury wellness accommodation and were chosen to ensure representation across geographical and brand diversity within the spa tourism segment.

The data were obtained using Outscraper, a third-party scraping tool that enables structured data collection from Google Maps review sections (). This study adopts a full-history snapshot of the hotels’ online reviews. For each of the ten spa hotel properties, all Google reviews available from the earliest review on record to the study’s data-snapshot date were included. The design prioritizes a comprehensive view of guest experience rather than period contrasts; accordingly, no pre/post temporal strata were imposed in sampling. Accordingly, the covered period is defined by the earliest and latest timestamps observed in the study. The initial scraping process yielded a total of 22,926 reviews. However, to enhance the quality and reliability of the dataset, a rigorous refinement process was conducted. This included the elimination of reviews with missing textual content, duplicated entries, irrelevant characters or emojis, and content not related to the hotel’s services or experiences. Emojis and special characters were removed because this study predictors are LIWC-22 category rates, which rely on validated word-level dictionaries rather than pictographic tokens. Including emojis without a dedicated, validated mapping would introduce construct inconsistency, and emoji meanings vary by rendering/platform, creating interpretation noise that LIWC does not model (). As a result, a final dataset comprising 15,560 valid reviews was retained for analysis.

Table 1 provides a summary of the number of raw and filtered reviews for each of the ten hotels. Notably, Ayodya Resort Bali received the highest number of reviews, with 6632 initially collected and 3975 retained after refinement. The total number of reviews used in the study reflects a diverse and representative set of guest perspectives, forming a solid foundation for psycholinguistic and statistical analysis.

Table 1.

Review data.

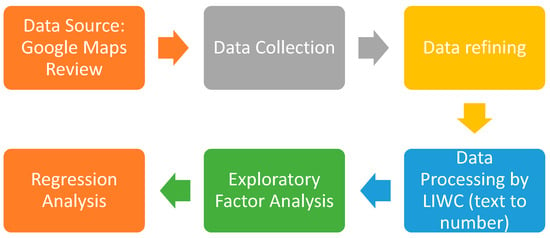

The research process followed in this study is depicted in Figure 1. It outlines each stage of the research workflow, beginning with hotel selection and data scraping, followed by review filtering, textual analysis, and statistical modeling. This systematic approach ensures that the study is methodologically sound and reproducible.

Figure 1.

Research flow.

3.2. Text Mining Using LIWC-22

To analyze the textual content of the collected reviews, this study employed the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC-22 v1.11.0) software. LIWC is a widely validated psycholinguistic tool that analyzes written or spoken language by categorizing words into psychological, cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions using a pre-developed dictionary (). Its applicability in hospitality and tourism research has been well established in the prior literature due to its ability to quantify qualitative data.

LIWC-22 (Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count) was used to quantify psycholinguistic properties of review text. The instrument provides a theory-anchored lexicon (affect, social, body/perceptual, cognitive) that maps tokens to validated categories and returns category rates (proportion of words per review), yielding transparent, reproducible indicators that are comparable across studies (; ). In this study, reviews were analyzed in English to align with LIWC-22’s native dictionary and preserve measurement consistency. The approach is lexicon-based (word categories) rather than employing contextual semantic modeling, prioritizing interpretability and cross-study comparability. The corpus was aligned with the native LIWC-22 dictionary, and the resulting category rates entered a structured pipeline, whereby exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to distill higher-order dimensions, followed by regression models with controls (review rating), linking guest language to the wellness experience and service quality constructs.

In this research, four independent variables were derived from the LIWC categories—Emotional Tone, Social, Health and Wellness, and Lifestyle. These variables were standardized on a scale from 0 to 1, aligned with the original scale of 0 to 100, making the difference scale smaller than that of other variables (). This allows for more precise observations and comparisons among the variables. The Emotional Tone variable reflects the affective sentiment embedded in the reviews, capturing both positive and negative emotional cues. The Social dimension focuses on interpersonal elements such as guest interaction with staff, group dynamics, and references to family or friends. Health and Wellness captures mentions related to physical well-being, hygiene, cleanliness, and the availability or quality of spa treatments—factors particularly relevant to wellness tourism. The Lifestyle dimension refers to language relating to leisure, ambiance, spirituality, and recreational elements tied to the spa experience ().

All LIWC-derived scores were normalized to a scale ranging from 0 to 1. This transformation ensured consistency in measurement and allowed for meaningful comparison across the large dataset. The dependent variable in this study was customer satisfaction, which was operationalized using the 1- to 5-star rating assigned by guests in their Google Maps reviews. This rating serves as a reliable indicator of the overall evaluation of the hotel experience, encompassing both tangible and intangible service elements.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

To identify the latent constructs underlying the language used in the reviews, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted using SPSS 27. EFA was chosen as the primary technique because the study does not rely on a predefined theoretical structure and seeks to explore the underlying relationships between observed linguistic choices (). The extraction method applied was Principal Axis Factoring (PAF), which is suited for identifying common variance among correlated variables. To facilitate the interpretation of the factor structure, the Varimax orthogonal rotation was employed. The decision on the number of factors to retain was informed by Kaiser’s criterion, which considers eigenvalues greater than one as meaningful; this was further validated using parallel analysis to enhance the robustness of the factor solution.

To ensure the appropriateness of the data for factor analysis, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity were applied. A KMO value above the acceptable threshold of 0.60 was considered acceptable for exploratory factor analysis; values in the range of 0.60 are typically classified as mediocre but adequate when the construct domain is broad and intercorrelations are moderate (; ). A significant Bartlett’s Test result (p < 0.05) indicated that the inter-variable correlations were strong enough to justify factor extraction. A factor loading threshold of 0.40 was used to retain only those variables with meaningful contributions to the factor structure, with loadings below this value considered weak and therefore excluded from interpretation (; ).

Following the identification of factors, a multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to assess the impact of the LIWC-based independent variables on customer satisfaction. The regression model evaluated the direction and strength of each predictor, using standardized beta coefficients and significance levels (p < 0.05) to determine statistical relevance. This dual application of EFA and regression analysis provided a comprehensive methodological framework to uncover not only the structure of guest perceptions but also their practical implications for hotel reputation management ().

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Word Frequency

A total of 22,926 user-generated reviews were collected from Google Maps for ten selected spa hotels in Bali. As shown in Table 2, the number of reviews per hotel varies considerably, with Ayodya Resort Bali receiving the highest number of reviews (n = 6632), followed by Padma Resort Ubud (n = 4618). Interestingly, the volume of reviews appears to be independent of the listed hotel prices, suggesting that factors such as guest volume, brand popularity, and review solicitation strategies may influence engagement more than pricing alone.

Table 2.

Number of reviews and hotel prices.

To explore the most salient themes discussed by guests, a word frequency analysis was conducted using text mining techniques. The results are visualized in the word cloud displayed in Figure 1, where the size of each word reflects its relative frequency in the overall dataset. The word “hotel” appears as the most frequently mentioned term (n = 5096), followed by “staff,” “resort,” “great,” and “room.” These dominant terms highlight the central aspects of guest experience narratives, particularly in relation to the overall environment, personnel, facilities, and perceived service quality.

The repeated mentions of words such as “staff” and “service” emphasize the critical role of human interaction in shaping guest experience (). Simultaneously, terms like “pool,” “room,” “breakfast,” and “restaurant” indicate that physical amenities and food services are pivotal elements in spa hotel evaluations (). Positive affective expressions such as “great,” “nice,” “amazing,” and “friendly” further suggest that emotional impressions are strongly embedded in guest feedback, reinforcing the significance of experiential value in wellness-oriented tourism ().

The word cloud in Figure 2 offers a visual summary of these thematic patterns and serves as a foundation for the subsequent psycholinguistic and statistical analyses presented in later sections of this study. It provides an accessible overview of the most recurrent lexical items, enabling a preliminary understanding of guest priorities and perceptions.

Figure 2.

Wordcloud result.

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

To identify the underlying dimensions embedded in the psycholinguistic patterns of online reviews, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted using the LIWC-derived variables (). The results, presented in Table 3, reveal that the EFA extracted four distinct factors that account for the majority of the variance in the dataset: Social, Health and Wellness, Lifestyle, and Emotional Tone. These factors emerged through Principal Axis Factoring with Varimax rotation and met the standard retention criterion of having eigenvalues greater than 1, which is a widely accepted threshold indicating that the factor explains more variance than a single observed variable. Thus, factor loadings are correlations bounded in [-1, 1]. Varimax promotes simple structure with high primary loadings and minimal cross-loadings, so values near 0.99 are admissible when communalities are high (; ; ).

Table 3.

Exploratory factor analysis results.

The first factor, Social, includes items such as social behavior, social, social references, and prosocial, with factor loadings ranging from 0.613 to 0.929. This dimension represents interpersonal interaction and social presence within the review content, contributing 21.94% of the total variance. The second factor, Health and Wellness, includes items such as wellness, mental health, health, and physical, with strong loadings above 0.95 (except physical at 0.416). This factor accounts for an additional 15.683% of the variance and reflects the importance of well-being and hygienic concerns in shaping spa experiences ().

The third factor, Lifestyle, comprises leisure, lifestyle, work, and money, with loadings ranging from 0.469 to 0.951. This factor captures the broader context of personal habits and values associated with relaxation, balance, and socioeconomic references, explaining 10.942% of the total variance. The fourth factor, Emotional Tone, is composed of positive emotion and distress emotion, both with exceptionally high loadings of 0.994, representing the emotional polarity expressed in reviews. This factor contributes 9.71% of the variance.

Together, these emotional dimensions explain the 58.28% of variance accounted for within the linguistic feature space (LIWC category rates) by the retained factors. This is distinct from variance in satisfaction ratings, which reflect additional influences beyond review language.

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) index was 0.642, exceeding the 0.60 benchmark for exploratory work in broad construct domains (). Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (p < 0.05), indicating a factorable correlation matrix. Pre-extraction screening removed near-zero-variance categories, excluded variables with measure of sampling adequacy (MSA) < 0.50 in the anti-image matrix, and dropped variables with low initial communalities. Using PAF with Varimax rotation, the retained solution satisfied the Kaiser eigenvalue-greater-than-one criterion and was corroborated by parallel analysis, yielding a clear, interpretable structure for subsequent regression analyses.

In addition, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity produced a highly significant result (χ2 = 89,012.143, p < 0.001), confirming that the correlation matrix is not an identity matrix and that sufficient correlations exist among the variables to proceed with factor analysis. This supports the statistical appropriateness of applying EFA in this context and strengthens the reliability of the extracted factor structure.

4.3. Regression Analysis

To determine the extent to which each identified factor influences guest satisfaction as a result of their experience, a multiple linear regression analysis was conducted using the four extracted variables from the Exploratory Factor Analysis as predictors. The dependent variable was the review rating provided by guests on Google Maps, serving as a quantitative proxy for customer satisfaction.

The results of the regression are presented in Table 4, which displays both unstandardized coefficients (β) and standardized coefficients (Beta) for each factor. The Social factor exhibited the strongest positive effect on review ratings, with a standardized coefficient of Beta = 0.028 and a corresponding t-value of 3.499, which is statistically significant at p < 0.05. The Health and Wellness factor followed with Beta = 0.023 (t = 2.852, p < 0.05), indicating a similarly significant but slightly weaker influence.

Table 4.

Standardized coefficients results.

Emotional Tone showed a small, non-significant association with satisfaction (β = 0.006, t = 0.727, p < 0.05), while the Lifestyle factor had the weakest contribution, with β = 0.004 and a non-significant t-value of 0.476.

The overall regression model yielded an R2 value of 0.001, with an adjusted R2 value of 0.001. Correlations between the independent variables and the dependent variable were small, which is expected because customer satisfaction is influenced by many factors not captured in the available data (). Although this indicates a relatively low proportion of explained variance, the F-statistic of 5.283 was statistically significant at p < 0.05, confirming that the model, as a whole, demonstrates a meaningful relationship between the extracted factors and guest satisfaction scores.

These results confirm that among the psycholinguistic dimensions extracted through text analysis, the Social and Health and Wellness factors are statistically significant predictors of review ratings, while Emotional Tone and Lifestyle are not significant contributors in this model.

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

First, the Social factor emerged as the most influential predictor of customer satisfaction. This finding confirms and extends the work of (), who emphasized the role of social and individual values in shaping customer engagement in luxury thermal spa hotels. Their study highlighted that constructs such as perceived justice and emotional brand experience mediate the relationship between social values and behavioral outcomes. The high factor loadings in our study on terms such as social behavior, social references, and prosocial suggest that Bali spa hotel guests place significant value on interpersonal connections—be it through guest–staff interaction, group participation (e.g., family or couple packages), or socially responsible practices (e.g., eco-conscious spa operations). This strongly supports the literature suggesting that social identity and community bonding are critical in luxury and wellness-based tourism ().

The Health and Wellness factor, the second strongest predictor, reaffirms the findings of (), who highlighted the centrality of wellness features in tourism satisfaction. However, while their work primarily focused on service quality dimensions such as facility cleanliness and professional competence, our study’s higher loadings on mental health and wellness (both at 0.966) suggest a stronger orientation toward psychological and emotional healing rather than solely physical treatments. This reflects the evolving demand for transformational wellness experiences, especially in post-pandemic travel contexts, where stress relief, mindfulness, and inner peace are key motivators (). The relatively lower loading for physical (0.416) supports this shift toward mind–body integration rather than a purely physiological focus.

The Emotional Tone factor revealed emotionally complex narratives in which positive and distress terms often co-occur, consistent with the idea of emotional transitions during the spa journey. Although Emotional Tone did not significantly predict satisfaction once the Social and Health and Wellness factors were controlled, the factor structure points to emotional ambivalence and trajectory (e.g., movement from stress to calm), aligning with recent work on emotional journeys in reviews and transformation in spa contexts (; ). Practically, this suggests using tone monitoring for service-recovery cues rather than expecting strong direct effects on ratings.

In contrast, the Lifestyle factor demonstrated the weakest predictive power. This contradicts earlier works such as from () and (), which highlighted lifestyle motivations—such as escape from work, indulgence, and luxury self-care—as being central to spa and wellness tourism. Our findings suggest that while guests do mention terms like leisure, lifestyle, work, and money, these are not decisive in determining their satisfaction. One explanation is that lifestyle may be a background motivator rather than an evaluative factor, meaning guests might travel for lifestyle-related reasons but ultimately evaluate their stay based more on relational and emotional experiences. Moreover, Bali’s wellness tourism may uniquely emphasize cultural immersion and spiritual healing, which are not captured well by conventional lifestyle metrics.

Lastly, the modest explanatory power of the regression model (R2 = 0.001) implies that there are additional factors influencing customer satisfaction that were not captured through LIWC-based psycholinguistic dimensions. Elements such as environmental esthetics, cultural symbolism, and place attachment—especially prominent in Bali’s wellness context—might be underrepresented in LIWC’s generic lexicon. Taken together, these points indicate that the findings should be interpreted within the lexical and language scope of LIWC-22 and the Bali cultural setting. Aspects like melukat purification rituals, nature-based design (e.g., jungle views and open-air spas), or local heritage experiences could play a meaningful role in shaping satisfaction yet fall outside the scope of conventional textual categories. Future work can broaden coverage through multilingual/cross-lingual lexicons or contextual models, as well as triangulating with qualitative evidence (interviews and observations) to consolidate the subjective dimensions of the experience.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the hospitality and wellness tourism literature by demonstrating how a psycholinguistic analysis of user-generated content can reveal the underlying drivers of guest experience. By applying LIWC-22 to Google Maps reviews, the study extends methodological boundaries in tourism research, offering a scalable approach to capture the affective and cognitive dimensions of the guest experience that are often overlooked in traditional surveys.

The prominence of the Social and Health and Wellness factors reinforces the growing theoretical consensus that wellness tourism is not solely about physical rejuvenation but also about social connectedness and emotional healing. These findings support existing frameworks on service co-creation () and transformational tourism (), while highlighting how such constructs are linguistically encoded in natural guest feedback. Moreover, the distinct linguistic salience of mental health over physical health nuances previous wellness tourism theories by emphasizing psychological restoration as a core evaluative component.

Finally, the emergence of emotional duality—with both positive and distress emotions loading highly on the same factor—challenges binary sentiment models commonly used in tourism studies. This supports more complex emotional theories, such as emotional ambivalence (), and encourages future research to consider emotional transitions and narrative dynamics in guest reviews. The relatively weak impact of the Lifestyle factor also invites a refinement of existing models by distinguishing between motivational drivers and satisfaction outcomes in spa and wellness tourism contexts. While the LIWC-based pipeline is portable across destinations, the magnitude and salience of linguistic factors are context-dependent (e.g., culture, language mix, and spa product configuration); replication in other wellness hubs is recommended before drawing broader theoretical claims.

5.3. Practical Implications

The implications are Bali-specific, calibrated to a market with dense hotel-embedded spa supply, substantial online review volume, and a strong wellness identity. Transfer to other destinations is appropriate when similar structural conditions hold, and should be calibrated to local culture, language, and supply structure. The findings offer several actionable directions for spa hotel operators and destination managers aiming to enhance guest experience and digital reputation. The strong influence of social-related language suggests that spa hotels in Bali should invest in facilitating interpersonal engagement—such as group wellness activities, family packages, and personalized staff–guest interactions. Training programs that emphasize empathy, attentiveness, and cultural sensitivity among staff can further strengthen guest perceptions and contribute to favorable online reviews.

Given the significant role of health and wellness language, marketing strategies should go beyond highlighting physical spa treatments and instead emphasize holistic and mental rejuvenation. Phrases like “emotional reset,” “spiritual healing,” or “stress detox” can resonate more strongly with wellness travelers seeking transformation, especially in post-pandemic contexts. Offering curated programs that blend mindfulness practices, yoga, local healing rituals, and natural surroundings will help align service offerings with evolving guest expectations.

Although emotional tone and lifestyle references did not show a significantly predictive power, they still provide value when interpreted strategically. Management can utilize sentiment analysis tools to monitor changes in emotional expressions over time and address guest concerns before they escalate into negative reviews. While lifestyle themes like luxury or indulgence may not directly drive satisfaction, they remain important for market positioning. Promoting spa packages as “earned escapes” or “self-care investments” can appeal to professionals and experience-seeking travelers without overpromising outcomes unrelated to core satisfaction factors. As a result, destinations sharing these features can adapt the principles by aligning hygiene/treatment standards, investing in staff empathy and multilingual services, and institutionalizing text-analytics for reputation management, while safeguarding local wellness traditions.

6. Conclusions

This study highlights the central role of social connection and holistic wellness in shaping guest experience and digital reputation in Bali’s spa hotel market. A psycholinguistic analysis of Google reviews identifies four stable dimensions—Social, Health and Wellness, Emotional Tone, and Lifestyle—with the first two being the most influential; in the text, these manifest as staff empathy/responsiveness (e.g., “friendly,” “attentive,” “felt welcomed”), treatment quality and hygiene (e.g., “massage,” “therapist,” “professional,” “clean/spotless”), affective cues (e.g., “relaxed,” “calm,” “recharged,” “stressed,” “disappointed”), and ambience/esthetics (e.g., “ambience,” “scent,” “music,” “view,” “pool”). Theoretically, the findings deepen our understanding of experiential value by foregrounding interpersonal and emotional dynamics; managerially, they translate into targeted actions in service training, hygiene/treatment assurance, sentiment monitoring, and ambience curation.

While this study focuses on the top 10 spa hotels on TripAdvisor to capture the dynamics of the luxury spa segment, we acknowledge that mid- to low-range accommodation and independent spa operators may highlight different dimensions of the spa experience, offering opportunities for future comparative research. This study also notices that distinctive Balinese healing traditions, such as melukat rituals, are not represented in this research due to the image of being offered as separate cultural experiences outside the resort setting, which explains their absence from the spa resort reviews analyzed in this study.

The study intentionally prioritizes interpretability and comparability by using LIWC-22’s validated word-based categories and analyzing the full review history (rather than pre/post-COVID-19 partitions); to preserve lexical consistency, emojis and special characters were excluded. Because ratings are influenced by many factors beyond language, a modest R2 value is expected; therefore, interpretation centers on the direction and magnitude of effects. External context (e.g., price, location/access, marketing exposure) may also shape evaluations, and online reviews can reflect self-selection. This study’s contribution could be significantly enhanced by including additional independent variables to improve explanatory power and by incorporating cultural context, which is also an important consideration for future research. Future work may also broaden the scope by adding contextual covariates, applying explicit temporal segmentation, incorporating emoji-aware or context-sensitive models, conducting multi-site or multilingual validation, and triangulating text analytics with qualitative interviews, observations, and brief questionnaires (e.g., service quality and post-stay satisfaction scales) to further strengthen both validity and explanatory power.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: N.A. and A.W.; methodology: N.A., A.W., and H.-S.K.; formal analysis: N.A. and A.W.; data curation: N.A. and A.W.; writing—original draft preparation: N.A. and A.W.; writing—review and editing: H.-S.K.; visualization: N.A.; supervision: H.-S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aliyah, U., Williady, A., & Kim, H. S. (2025). An evaluation of green hotels in Singapore, Sentosa Island: A big data study through online review. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asia’s Best Spa Destination. (2025). World spa awards. Available online: https://worldspaawards.com/award/asia-best-spa-destination (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- BaliPost. (2023). Ketua phri bali minta industri spa jaga martabat. Available online: https://www.balipost.com/news/2023/09/09/361131/Ketua-PHRI-Bali-Minta-Industri...html (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Baloglu, S., Busser, J., & Cain, L. (2019). Impact of experience on emotional well-being and loyalty. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(4), 427–445. [Google Scholar]

- Bastič, M., & Gojčič, S. (2012). Measurement scale for eco-component of hotel service quality. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3), 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R. L., Ashokkumar, A., Seraj, S., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2022). The development and psychometric properties of LIWC-22. University of Texas at Austin. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BPS Bali. (2024). Banyaknya wisatawan mancanegara bulanan ke bali menurut pintu masuk (orang). Available online: https://bali.bps.go.id/id/statistics-table/2/MTA2IzI=/banyaknya-wisatawan-mancanegara-bulanan-ke-bali-menurut-pintu-masuk--orang-.html (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Chamberlain, L. A., Moreno-Brito, Y. L., & Kim, H.-S. (2025). eWOM revenge in small accommodations: Investigating the mediating role of clout in guest de-influencing behaviour in Jamaica. Consumer Behavior in Tourism and Hospitality, 20(2), 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrey, A. L., & Lee, H. B. (2013). A first course in factor analysis. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dryglas, D., & Salamaga, M. (2018). Segmentation by push motives in health tourism destinations: A case study of Polish spa resorts. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effendi, M., Matore, E. M., Khairani, A. Z., & Adnan, R. (2019). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) for adversity quotient (AQ) instrument among youth. Journal of Critical Reviews, 6(6), 234–242. [Google Scholar]

- Fabrigar, L. R., & Wegener, D. T. (2012). Exploratory factor analysis. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Filieri, R. (2015). What makes online reviews helpful? A diagnosticity-adoption framework to explain informational and normative influences in e-WOM. Journal of Business Research, 68(6), 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Wellness Institute. (2021). Wellness tourism, spas, thermal/mineral springs. Available online: https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/wellness-tourism-spas-mineral-thermal-springs-the-global-wellness-economy-looking-beyond-covid-2021/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Gretzel, U., Sigala, M., Xiang, Z., & Koo, C. (2015). Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electronic Markets, 25(3), 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, L., & Stephen, A. T. (2019). Credibility of negative online product reviews: Reviewer gender, reputation and emotion effects. Journal of Marketing Research, 56(5), 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Jr., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis. In Pearson new international edition. Annabel Ainscow. [Google Scholar]

- Handani, N. D., Williady, A., & Kim, H. S. (2022). An analysis of customer textual reviews and satisfaction at luxury hotels in Singapore’s marina bay area (SG-clean-certified hotels). Sustainability, 14(15), 9382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Chen, C. B., & Gao, M. J. (2019). Customer experience, well-being, and loyalty in the spa hotel context: Integrating the top-down & bottom-up theories of well-being. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(5), 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japutra, A., Loureiro, S., Molinillo, S., & Primanti, H. (2023). Influence of individual and social values on customer engagement in luxury thermal spa hotels: The mediating roles of perceived justice and brand experience. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 25(1), 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justitia, A., Semiati, R., & Ayuvinda, N. R. (2019). Customer satisfaction analysis of online taxi mobile apps. Journal of Information Systems Engineering and Business Intelligence, 5(1), 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B., Kim, S., & Heo, C. Y. (2016). Analysis of satisfiers and dissatisfiers in online hotel reviews on social media. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(9), 1915–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R., Ye, H., & Chan, I. (2021). A critical review of smart hospitality and tourism research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(2), 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magno, F., Cassia, F., & Bruni, A. (2018). “Please write a (great) online review for my hotel!” Guests’ reactions to solicited reviews. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 24(2), 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M., & Baggio, R. (2022). Big data and analytics in hospitality and tourism: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(1), 231–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M., & Borghi, M. (2020). Environmental discourse in hotel online reviews: A big data analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(5), 829–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, M. S., Handani, N. D., & Kim, H. S. (2023). Exploring user generated content for beach resorts in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh: A pre- and post-pandemic analysis. Environment and Social Psychology, 8(2), 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, L. C., & Lunders, E. R. (2002). Resolution of lexical ambiguity by emotional tone of voice. Memory & Cognition, 30(4), 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Y., Mistur, E., Kim, D., Mo, Y., & Hoefer, R. (2022). Toward human-centric urban infrastructure: Text mining for social media data to identify the public perception of COVID-19 policy in transportation hubs. Sustainable Cities and Society, 76, 103524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plutchik, R. (2001). Integration, differentiation, and derivatives of emotion. Evolution and Cognition, 7(2), 114–205. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creating unique value with customers. Strategy and Leadership, 32(3), 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A., Bala, P. K., & Rana, N. P. (2021). Exploring the drivers of customers’ brand attitudes of online travel agency services: A text-mining based approach. Journal of Business Research, 128, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rencher, A. C. (2002). Methods of multivariate analysis. In Wiley series in probability and statistics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M., & Puczkó, L. (2014). Health, tourism and hospitality: Spas, wellness and medical travel. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, B. A., & Browning, V. (2011). The impact of online reviews on hotel booking intentions and perception of trust. Tourism Management, 32, 1310–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2023). Main resources used for trip inspiration by travelers worldwide as of April 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1412020/resources-trip-inspiration-travelers-worldwide/ (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Tang, M., & Kim, H. S. (2022). An exploratory study of electronic word-of-mouth focused on casino hotels in las vegas and macao. Information, 13(3), 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S., & Kim, H.-S. (2022). Online customer reviews: Insights from the coffee shops industry and the moderating effect of business types. Tourism Review, 77(5), 1349–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tausczik, Y. R., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2010). The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 29(1), 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripadvisor. (2025). The 10 best Bali spa resorts 2025 (with prices). Available online: https://www.tripadvisor.com/Hotels-g294226-zff13-Bali-Hotels.html (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Voigt, C., Brown, G., & Howat, G. (2011). Wellness tourists: In search of transformation. Tourism Review, 66(1), 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigert, A. J. (1991). Mixed emotions: Certain steps toward understanding ambivalence. State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williady, A., Narariya, D. H., & Kim, H. S. (2024). Investigating efficiency and innovation: An exploratory and predictive analysis of smart airport systems. Digital, 4(3), 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williady, A., Wardhani, H. N., & Kim, H. S. (2022). A study on customer satisfaction in Bali’s luxury resort utilizing big data through online review. Administrative Sciences, 12(4), 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z., Schwartz, Z., Gerdes, J. H., Jr., & Uysal, M. (2015). What can big data and text analytics tell us about hotel guest experience and satisfaction? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 44, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Mao, Z., & Tang, J. (2018). Understanding guest satisfaction with urban hotel location. Journal of Travel Research, 57(2), 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarezadeh, Z. Z., Rastegar, R., & Xiang, Z. (2022). Big data analytics and hotel guest experience: A critical analysis of the literature. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(6), 2320–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., & Kim, H.-S. (2021). Customer experience and satisfaction of disneyland hotel through big data analysis of online customer reviews. Sustainability, 13(22), 12699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).