Wellness Tourism Experiences and Tourists’ Satisfaction: A Multicriteria Analysis Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the primary satisfaction dimensions in wellness tourism as perceived by visitors?

- What is the relative importance and perceived performance of these dimensions?

- How can the results inform destination management and service design in wellness tourism settings?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Wellness Tourism: Definitions, Motivations, and Trends

2.2. Wellness Tourism in Greece

2.3. Tourist Satisfaction in Wellness Tourism

2.4. Multicriteria Satisfaction Analysis in Wellness Tourism

2.5. Conceptual Framework

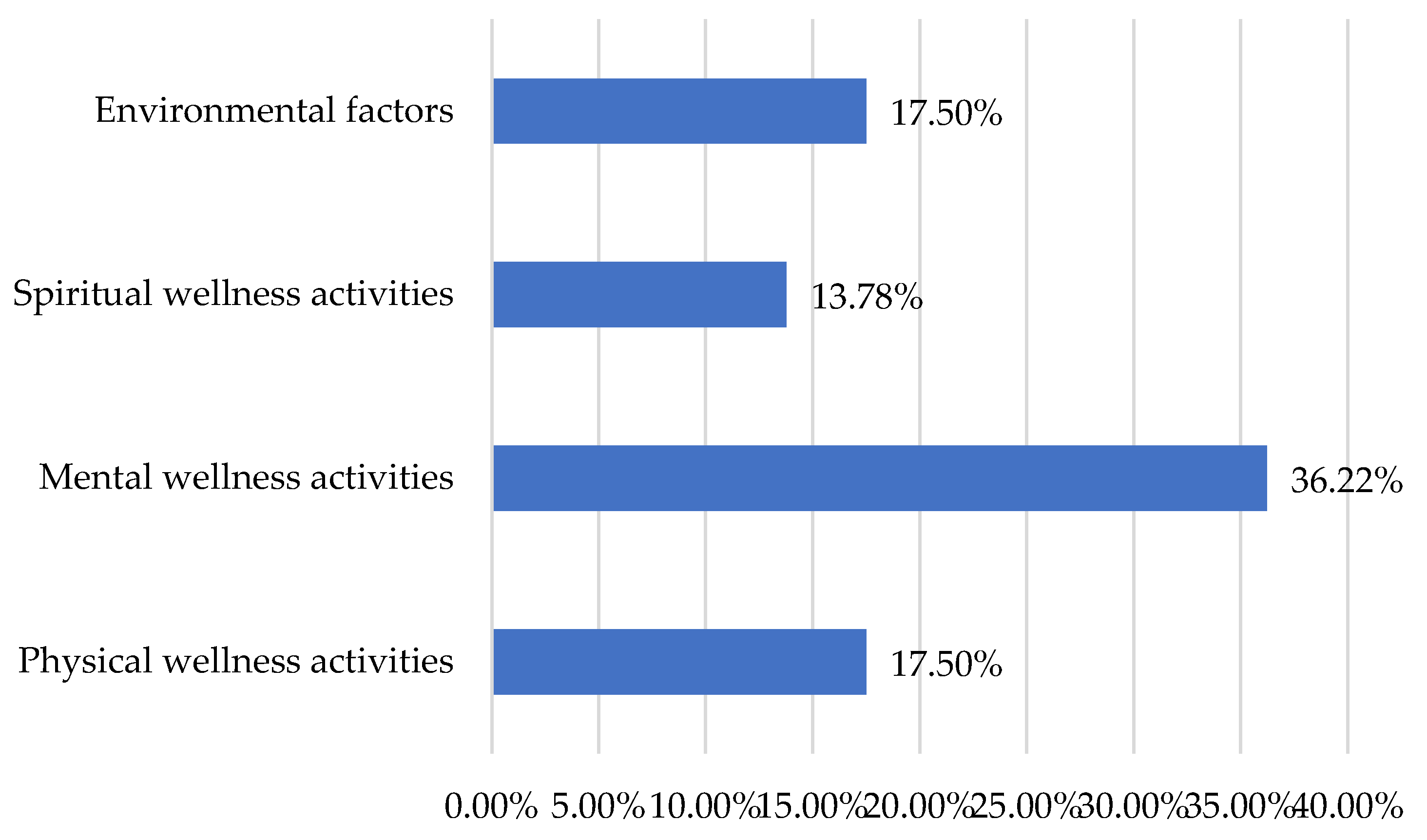

- Physical wellness activities: provided meals; physically engaging wellness activities; physically non-engaging wellness activities; activities supporting body detoxification.

- Mental wellness activities: activities that stimulate cognitive development; activities that promote mind escape and restoration from everyday thoughts.

- Spiritual wellness activities: spiritually meaningful experiences; shared experiences among visitors; experiences involving deep engagement or personal immersion in a specific activity or setting.

- Environmental factors: staff; location; price; private spaces; shared/public spaces; privacy and avoidance of overcrowding.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data and Research Tool

- Demographics (e.g., age, gender, education, employment, income);

- Travel characteristics (e.g., trip duration, purpose, participation frequency);

- Satisfaction evaluation, comprising 15 Likert-scale sub-criteria organized under four key criteria (physical, mental, spiritual, environmental);

- Overall satisfaction score, rated on a 5-point scale.

3.2. MUSA Method Application

3.2.1. Overview of the MUSA Method

3.2.2. Methodological Application of the MUSA Method

4. Results

4.1. Sample Demographics

4.2. Participation in Wellness Tourism Activities

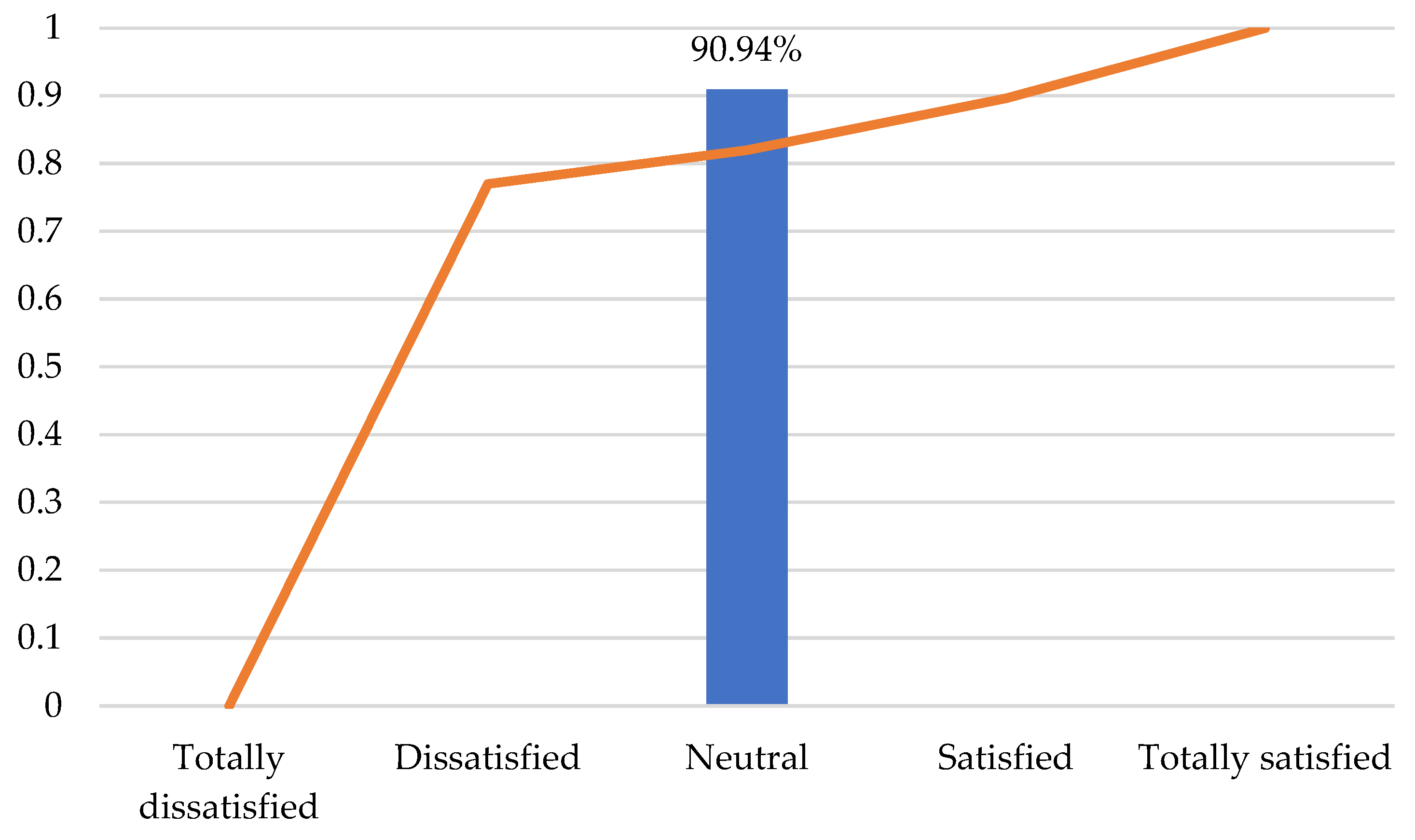

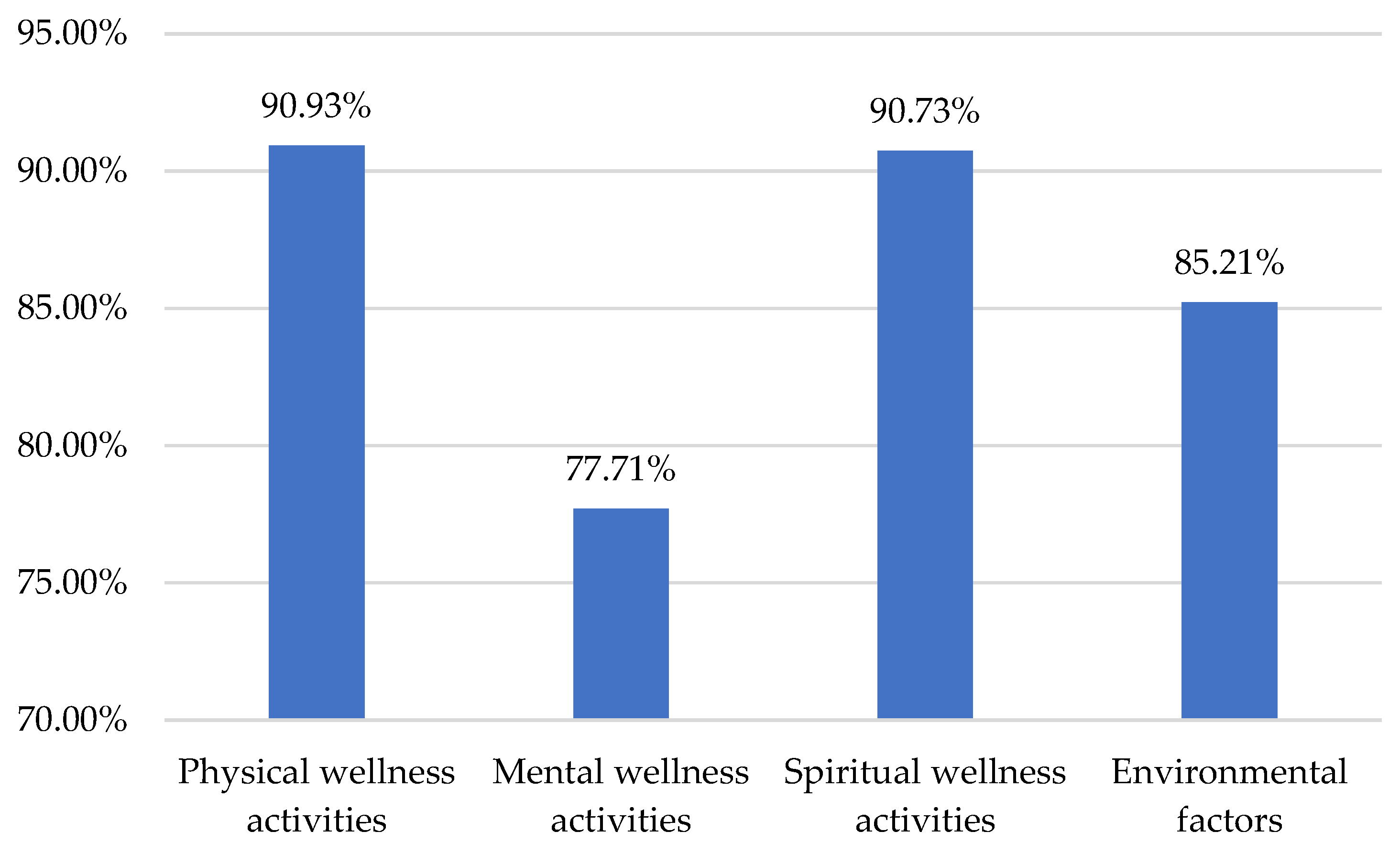

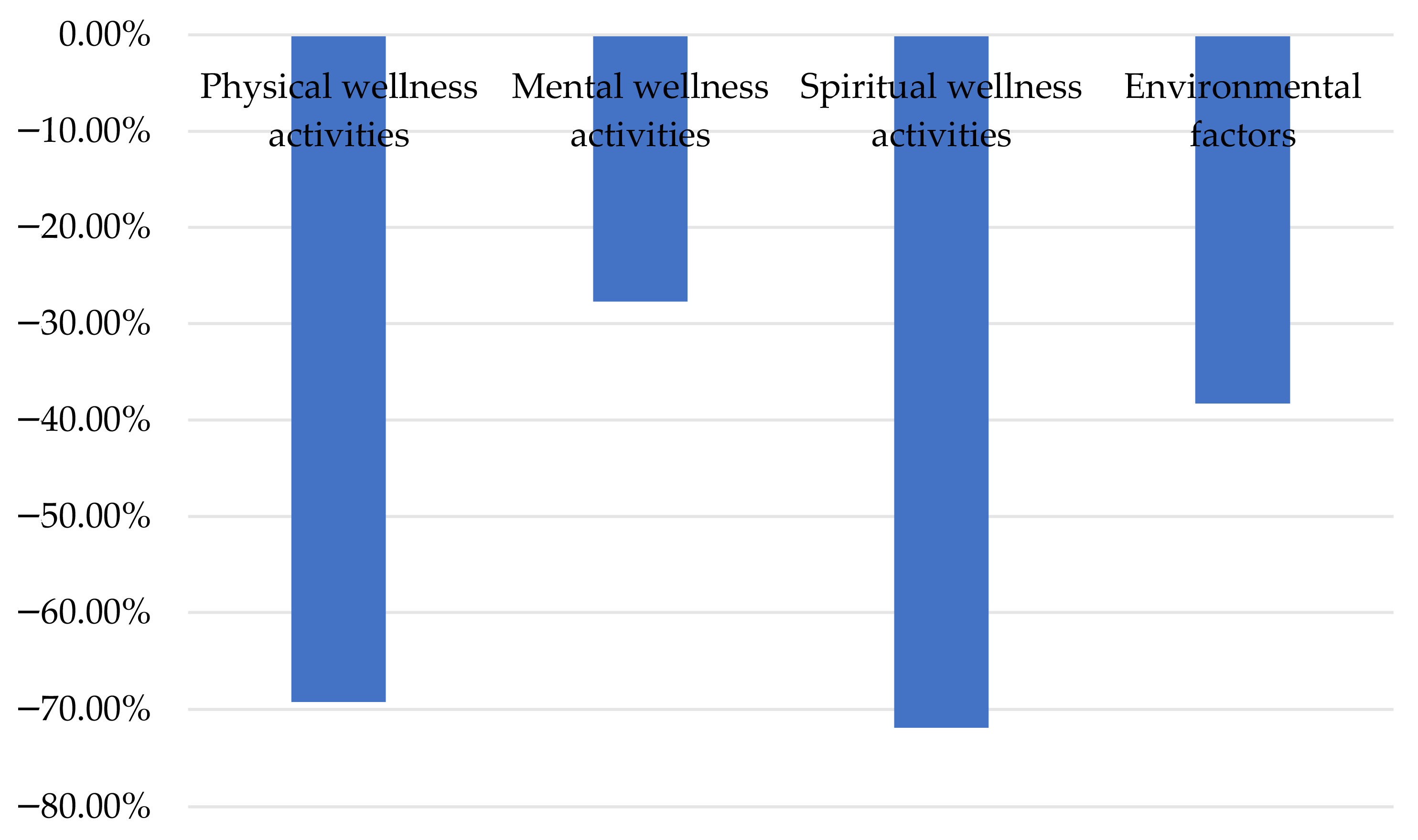

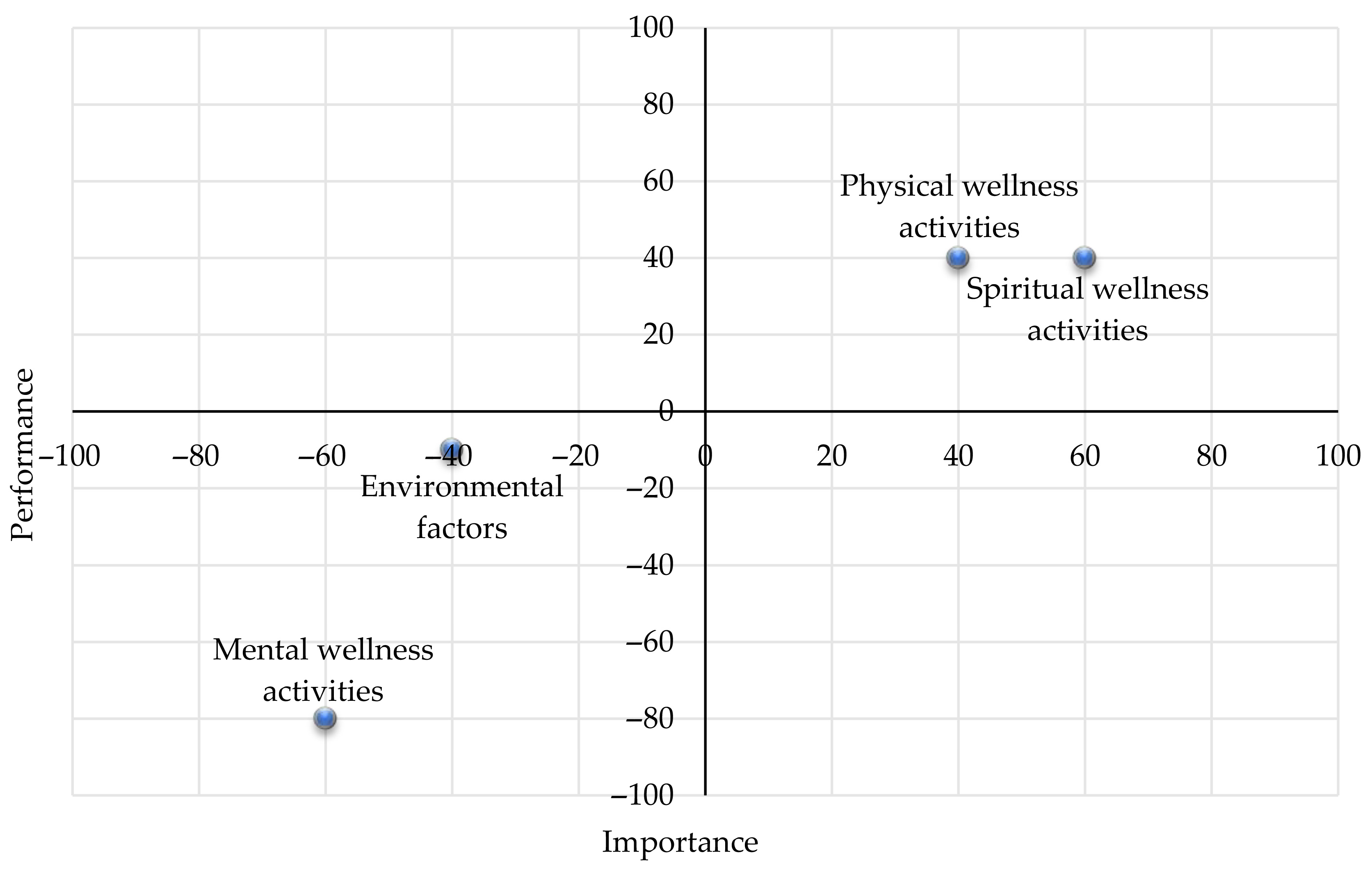

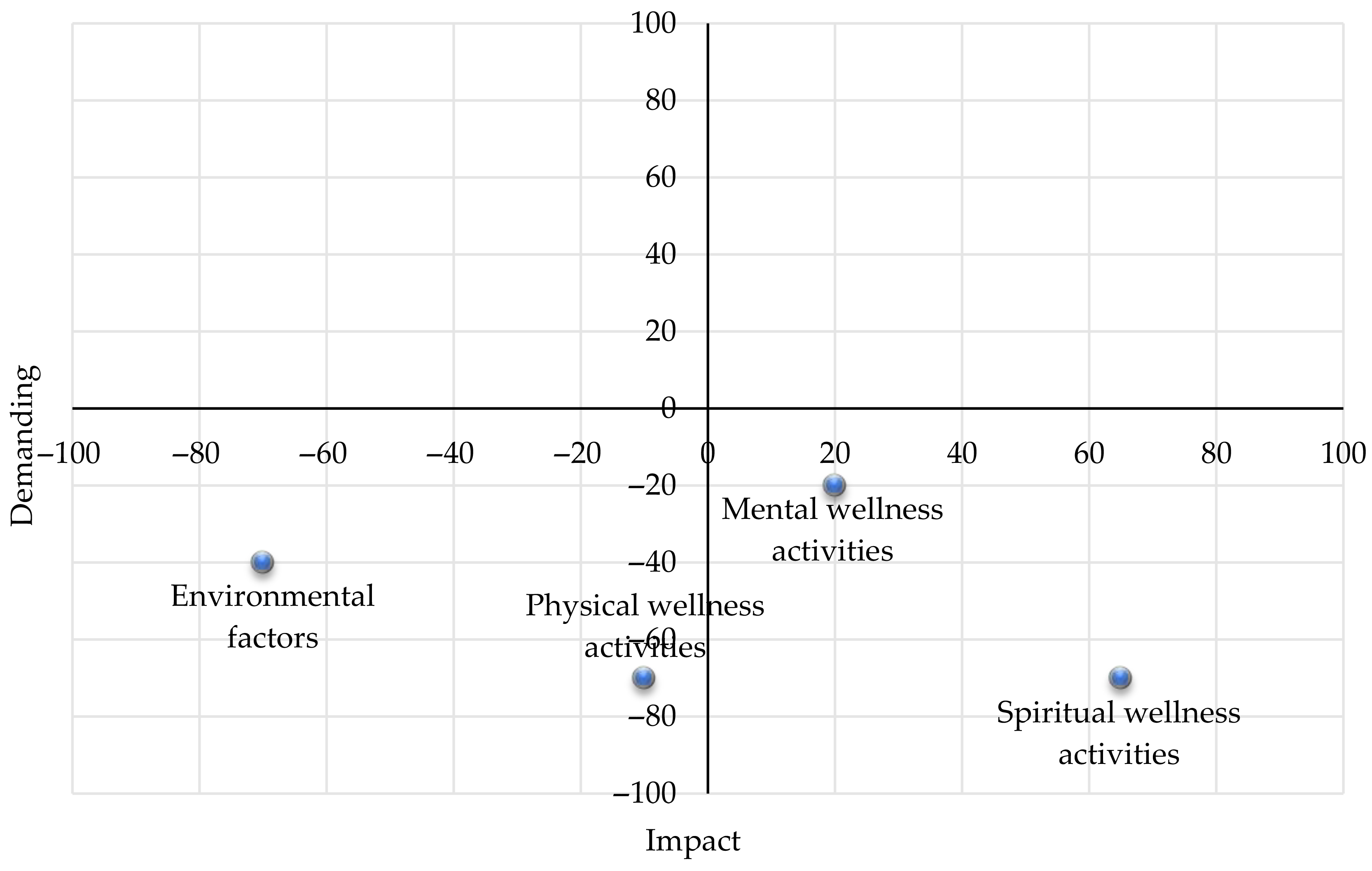

4.3. Satisfaction Measurement

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Conclusions

5.3. Managerial and Social Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahn, Y. J., & Kim, K. B. (2024). Understanding the interplay between wellness motivation, engagement, satisfaction, and destination loyalty. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allied Market Research. (2020). Wellness tourism market is expected to reach $1592.6 billion by 2030-Allied market research. Available online: https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/press-release/wellness-tourism-market.html (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Anaya-Aguilar, R., Gemar, G., & Anaya-Aguilar, C. (2021a). A typology of spa-goers in southern Spain. Sustainability, 13(7), 3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya-Aguilar, R., Gemar, G., & Anaya-Aguilar, C. (2021b). Validation of a satisfaction questionnaire on spa tourism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu, M. G. N. L., Font-Barnet, A., & Roca, M. E. (2021). Wellness tourism—New challenges and opportunities for tourism in Salou. Sustainability, 13(15), 8246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, Y., & Sonmez, S. (2014). Greek tourism on the brink: Restructuring or stagnation and decline? In Mediterranean Tourism (pp. 72–88). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Balcioglu, Y. S. (2024). Exploring consumer engagement and satisfaction in health and wellness tourism through text-mining. Kybernetes. Ahead of Print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardukova, L. (2024). Health and wellness tourism: Current trends and strategies in the Bulgarian tourism industry. Economics and Computer Science, 2, 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Campón-Cerro, A. M., Di-Clemente, E., Hernández-Mogollón, J. M., & Folgado-Fernández, J. A. (2020). Healthy water-based tourism experiences: Their contribution to quality of life, satisfaction and loyalty. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J. S., Prebensen, N. K., & Uysal, M. S. (2024). Handbook of experience science: Tourism, hospitality, and leisure. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Csirmaz, É., & Pető, K. (2015). International trends in recreational and wellness tourism. Procedia Economics and Finance, 32, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillette, A. K., Douglas, A. C., & Andrzejewski, C. (2021). Dimensions of holistic wellness as a result of international wellness tourism experiences. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(6), 794–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, M., & Pencarelli, T. (2022). Wellness tourism and the components of its offer system: A holistic perspective. Tourism Review, 77(2), 394–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosos, D., & Skordoulis, M. (2018). The role of environmental responsibility in tourism. Journal for International Business and Entrepreneurship Development, 11(1), 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosos, D., Skordoulis, M., Arabatzis, G., Tsotsolas, N., & Galatsidas, S. (2019a). Measuring industrial customer satisfaction: The case of the natural gas market in Greece. Sustainability, 11(7), 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosos, D., Skordoulis, M., & Chalikias, M. (2019b). Measuring the impact of customer satisfaction on business profitability: An empirical study. International Journal of Technology Marketing, 13(2), 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Wellness Institute. (2021). Wellness tourism. Available online: https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/what-is-wellness/what-is-wellness-tourism/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Grigoroudis, E., & Siskos, Y. (2002). Preference disaggregation for measuring and analysing customer satisfaction: The MUSA method. European Journal of Operational Research, 143(1), 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. M. (2011). Health and medical tourism: A kill or cure for global public health? Tourism Review, 66(1/2), 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M., Liu, B., & Li, Y. (2023). Tourist inspiration: How the wellness tourism experience inspires tourist engagement. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 47(7), 1115–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, H. (2024). Relationship between tourists’ perceived restorative environment and wellness tourism destinations. International Journal of Tourism Research, 26(5), e2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Kim, J. J. (2023). A study on market segmentation according to wellness tourism motivation and differences in behavior between the groups—Focusing on satisfaction, behavioral intention, and flow. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K. X., Jin, M., & Shi, W. (2018). Tourism as an important impetus to promoting economic growth: A critical review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 26, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C., Zuo, Y., Xu, S., Law, R., & Zhang, M. (2023). Dimensions of the health benefits of wellness tourism: A review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1071578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C., Kim, K. H., Kim, M. J., & Kim, K. J. (2019). Multi-factor service design: Identification and consideration of multiple factors of the service in its design process. Service Business, 13(1), 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y. J., Kim, H. K., & Lee, T. J. (2016). Visitor motivational factors and level of satisfaction in wellness tourism: Comparison between first-time visitors and repeat visitors. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(2), 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Zhou, Y., & Sun, X. (2023). The impact of the wellness tourism experience on tourist well-being: The mediating role of tourist satisfaction. Sustainability, 15(3), 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P., Neves de Jesus, S., Pocinho, M., & Pinto, P. (2025). Wellness tourism: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Spa and Wellness, 8, 215–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Economy and Finance. (2025). Medium-term fiscal-structural plan 2025–2028. Available online: https://minfin.gov.gr/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/EN_Greece_MTFSP_2025_28_final.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Pantouvakis, A., & Bouranta, N. (2013). The interrelationship between service features, job satisfaction and customer satisfaction: Evidence from the transport sector. The TQM Journal, 25(2), 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riswanto, A. L., & Kim, H. S. (2023). An investigation of the key attributes of Korean wellness tourism customers based on online reviews. Sustainability, 15(8), 6702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuckert, M., Peters, M., & Pilz, G. (2018). The co-creation of host–guest relationships via couchsurfing: A qualitative study. Tourism Recreation Research, 43(2), 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, A. N., Foroughi, B., & Choong, Y. O. (2024). Tourists’ satisfaction, experience, and revisit intention for wellness tourism: E word-of-mouth as the mediator. Sage Open, 14(3), 21582440241274049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiq, Z. F., & Sahman, Z. (2025). The role of artificial intelligence in transforming smart tourism: Enhancing customer experience and service personalization. Journal of Sharia Economy and Islamic Tourism, 5(2), 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordoulis, M., Alasonas, P., & Pekka-Economou, V. (2017). E-government services quality and citizens’ satisfaction: A multi-criteria satisfaction analysis of TAXISnet information system in Greece. International Journal of Productivity and Quality Management, 22(1), 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordoulis, M., Patsatzi, O., Kalogiannidis, S., Patitsa, C., & Papagrigoriou, A. (2024a). Strategic management of multiculturalism for social sustainability in hospitality services: The case of hotels in Athens. Tourism and Hospitality, 5(4), 977–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordoulis, M., Stavropoulos, A. S., Papagrigoriou, A., & Kalantonis, P. (2024b). The strategic impact of service quality and environmental sustainability on financial performance: A case study of 5-star hotels in Athens. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(10), 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M., & Puczkó, L. (2014). Health, tourism and hospitality: Spas, wellness and medical travel. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M., & Puczkó, L. (2015). More than a special interest: Defining and determining the demand for health tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(2), 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E., Björk, P., & Coudounaris, D. N. (2023). Towards a better understanding of memorable wellness tourism experience. International Journal of Spa and Wellness, 6(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teeroovengadum, V., & Nunkoo, R. (2018). Sampling design in tourism and hospitality research. In Handbook of research methods for tourism and hospitality management (pp. 477–488). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, K., Ntanos, S., Kyriakopoulos, G. L., Skordoulis, M., & Getzner, M. (2024). Visitors’ environmental attitudes and willingness to pay for nature conservation: The case of Langtang National Park in the Himalayas. Global NEST Journal, 26(3), 05717. [Google Scholar]

- Tsekouropoulos, G., Vasileiou, A., Hoxha, G., Dimitriadis, A., & Zervas, I. (2024). Sustainable approaches to medical tourism: Strategies for central Macedonia/Greece. Sustainability, 16(1), 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, M., Tsartas, P., & Stogiannidou, M. (2016). Wellness tourism: Integrating special interest tourism within the Greek tourism market. Tourismos, 11(3), 210–226. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Category | % Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 31.48 |

| Female | 68.52 | |

| Age group | 18–35 | 43.2 |

| 36–45 | 22.2 | |

| 46–55 | 26.5 | |

| 56–65 | 7.4 | |

| Over 65 | 0.6 | |

| Annual income | Less than 10,000€ | 25.9 |

| 10,001€–20,000€ | 44.4 | |

| 20,001€–30,000€ | 19.1 | |

| 30,001€–40,000€ | 3.7 | |

| More than 40,000€ | 6.8 | |

| Profession | Unemployed | 3.09 |

| Public sector | 25.31 | |

| Private sector | 44.44 | |

| Self-employed/entrepreneur | 13.58 | |

| Retired | 1.28 | |

| Student | 12.35 | |

| Educational level | Secondary education | 4.32 |

| Associate’s degree | 15.43 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 50 | |

| Master’s degree | 25.31 | |

| Doctorate degree | 4.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karagianni, V.; Kalantonis, P.; Tsartas, P.; Sdrali, D. Wellness Tourism Experiences and Tourists’ Satisfaction: A Multicriteria Analysis Approach. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040179

Karagianni V, Kalantonis P, Tsartas P, Sdrali D. Wellness Tourism Experiences and Tourists’ Satisfaction: A Multicriteria Analysis Approach. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(4):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040179

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaragianni, Vasiliki, Petros Kalantonis, Paris Tsartas, and Despina Sdrali. 2025. "Wellness Tourism Experiences and Tourists’ Satisfaction: A Multicriteria Analysis Approach" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 4: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040179

APA StyleKaragianni, V., Kalantonis, P., Tsartas, P., & Sdrali, D. (2025). Wellness Tourism Experiences and Tourists’ Satisfaction: A Multicriteria Analysis Approach. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040179