Abstract

Celiac disease (CD) is a chronic autoimmune condition traditionally recognized for its gastrointestinal symptoms. However, growing evidence indicates that CD can also affect social and emotional health, particularly among children. This narrative review explores how the autoimmunity of CD may contribute to social–emotional dysregulation through mechanisms such as neuroinflammation, nutrient deficiencies, and disruption of the gut–brain axis. It summarizes the current literature on anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and autism spectrum disorder (ASD), highlighting how immune dysregulation may influence children’s social–emotional wellbeing. Delayed diagnosis, poor dietary adherence, and ongoing inflammation were recognized among children with social–emotional dysregulation. While digestive problems are commonly recognized and treated, social–emotional dysregulation among children with CD is frequently overlooked. However, a gluten-free diet without a confirmed diagnosis of CD is not sufficient to improve social–emotional outcomes. Children presenting with social–emotional dysregulation and clinical features suggestive of CD should be screened using standard serology and, when indicated, biopsy. Starting a gluten-free diet (GFD) without a confirmed diagnosis is not recommended. While mechanistic pathways are described, most evidence remains observational and clinically descriptive, underscoring the need for longitudinal and experimental studies to understand the intersectionality of CD with social–emotional dysregulation.

1. Introduction

Autoimmunity refers to an inappropriate immune response directed toward self-antigens [1]. It cannot be fully explained by genetic predisposition alone. It is influenced by a mix of environmental factors, psychological stress, epigenetic changes, and genetics [2]. Autoimmune diseases can affect nearly any part of the body. Gastrointestinal (GI) autoimmune disorders are particularly notable for their impact on the intestinal barrier, which can become more permeable and inflamed, resulting in a microbial imbalance [3,4]. The gut–brain axis hypothesis helps explain how psychological stress might influence gut health through shared hormonal and immune pathways [1,5].

Celiac disease is a chronic autoimmune condition caused by the ingestion of gluten—a protein found in grains such as wheat, barley, rye, oats, Khorasan, emmer, and malt [6]. Gluten provides elasticity to baked goods and has the potential to trigger both innate and adaptive immune responses in genetically predisposed individuals, leading to intestinal mucosal damage [7]. Celiac disease affects an estimated 0.5% to 1% of the global population, with a higher prevalence among people of Caucasian descent. In regions like the United States, Europe, and Australia, the prevalence among children ranges from 1 in 80 to 1 in 300 [8]. First identified centuries ago, celiac disease was more clearly understood during World War II when symptoms improved in children deprived of wheat during food shortages. This historical turning point helped solidify the link between gluten and disease manifestation, laying the foundation for today’s diagnostic approach [1].

Symptoms vary widely. It can range from asymptomatic to overwhelming systemic manifestations, including neurodevelopmental derangement [9]. Despite growing awareness and scientific advances in the management of celiac disease, the neurobehavioral effects remain underexplored and inconsistently studied, with notable methodological variability across reports.

Social–emotional dysregulation refers to the difficulty in managing emotions and engaging in healthy social interactions, which can negatively impact children’s quality of life [10]. In the context of chronic autoimmune disease, this dysregulation may arise not only from the stress of illness itself. It can originate from immune-driven changes in brain function, some of which are still not fully understood. Despite the link between autoimmunity and social–emotional dysregulation not yet fully understood, the immune activation and systemic inflammation appear to play central roles [11]. This review aims to summarize the current literature that studied the intersectionality of social–emotional dysregulation among children with Celiac disease.

2. Method

PubMed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and Scopus databases were searched for English-language studies from January 2000 to July 2025 using combinations of “celiac/coeliac”, “child/children/pediatric”, and terms for anxiety, GAD, ADHD, ASD, ODD, social–emotional outcomes, gut–brain axis, neuroinflammation, and cytokines. The review included pediatric or pediatric-stratified studies with biopsy and/or standard serology for CD; adult-only studies and non-CD gluten sensitivity without pediatric stratification were excluded unless directly informing mechanisms. The study prioritized population-based cohorts and longitudinal designs over small cross-sectional studies, but small studies were not excluded. There was no further statistical analysis or meta-analysis planned. Because of heterogeneity in study designs and outcomes, meta-analysis was not performed. Instead, we stratified the evidence by study type (registry-based cohorts, prospective, cross-sectional, case reports) and indicated relative strength and quality of evidence based on sample size, risk of bias, and study design.

2.1. Knowledge Gap and Rationale

Although gastrointestinal symptoms of celiac disease are widely recognized and screened, neurobehavioral symptoms often go unnoticed, especially among pediatric populations [12]. This gap in screening and diagnosis of CD presenting with social–emotional dysregulation can lead to delays in treatment and worsening developmental outcomes. Furthermore, clinical guidelines still tend to prioritize serological and histological findings, while ignoring psychosocial concerns and overall quality of life of children with CD [13].

2.2. The Objective of This Review

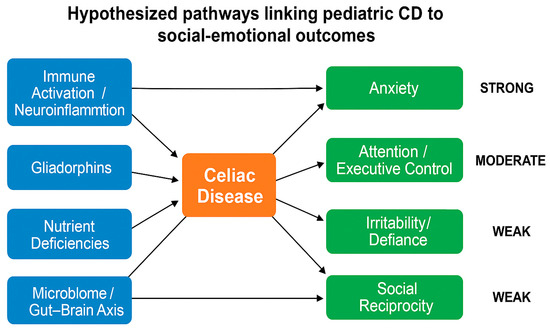

This narrative review aims to explore how autoimmunity and social–emotional dysregulation intersect with CD among children. The study focuses on the immunological drivers of neuropsychiatric symptoms while examining behavioral and cognitive outcomes of children with CD. Furthermore, the study weighs the role and potential benefits of a gluten-free diet for children with social–emotional dysregulation with or without a CD. These findings can improve early recognition and support interdisciplinary care that includes body, mind, and nutrition. By highlighting these connections, this study advocates for the integration of behavioral screenings into standard celiac care to improve the long-term quality of life among affected children. Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized pathways linking pediatric celiac disease (CD) to social–emotional outcomes. Celiac disease (orange) may influence child behavior and development through biological mechanisms (blue), including immune activation and neuroinflammation, gliadorphins, nutrient deficiencies, and disruption of the gut–brain axis. These pathways are linked to psychosocial outcomes (green), such as anxiety (supported by strong evidence from registry studies), ADHD/attention-executive dysfunction (moderate evidence from observational cohorts), and oppositional defiant disorder and autism spectrum features (weaker evidence from smaller cross-sectional studies). Arrows represent hypothesized associations, not proven causation.

2.3. Possible Pathophysiology of Social–Emotional Dysregulation Among Children with Celiac Disease

In celiac disease, incompletely digested gluten-derived peptides known as gliadorphins may mimic endogenous opioids. These peptides can cross both the intestinal and blood–brain barriers and may interact with opioid receptors in the brain, disrupting normal emotional processing and behavior [1]. Some studies suggest that this disruption may influence impulse control, irritability, and attention.

Immune activation is another mechanism implicated in the development of behavioral symptoms. Exposure to gluten in genetically susceptible individuals can lead to chronic inflammation. Activated T-cells and inflammatory cytokines may cross a permeable blood–brain barrier, contributing to localized neuroinflammation [14]. Even in the absence of overt neurological symptoms, changes such as silent cerebral inflammation and oxidative stress have been reported [14,15]. These processes may influence neurocognitive and emotional functioning. Oxidative injury in the small intestine may also have systemic effects that extend beyond the gut [15]. Stress-induced permeability of the intestinal lining has been observed in autoimmune conditions, possibly compounding this process [2].

Data from the TEDDY study [6] showed that children with persistent tissue transglutaminase autoantibody (tTGA) positivity—considered celiac disease autoimmunity—often exhibit elevated levels of anxiety, sleep issues, aggression, and attention difficulties. These behavioral signs are more prominent when caregivers are unaware of the child’s condition. Younger children tend to display these symptoms through irritability and behavioral dysregulation, while older children are more likely to verbalize discomfort and distress.

The expression of psychiatric and behavioral symptoms among children with CD appears to be multifactorial, involving immunologic, metabolic, social determinants of health and age-related developmental factors [2,5,14].

3. Autism and CD

ASD has been examined in relation to CD; however, the overall findings are inconsistent and inconclusive. Proposed pathways—including increased intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”), immune activation, and gliadin-derived exorphins (gliadorphins)—remain unconfirmed. Importantly, current evidence does not support recommending GFD for ASD in the absence of confirmed CD.

One hypothesized mechanism is that breakdown products of gliadin cross a more permeable intestinal barrier and, potentially, the blood–brain barrier, contributing to neurobehavioral symptoms [8]. In a small study, De Magistris et al. reported a positive association between increased intestinal permeability and ASD; however, this was associational rather than causal [4]. A second hypothesis involves diet-derived opioid peptides (exorphins) from gliadin/casein that, when incompletely degraded, might be absorbed and affect neural function.

Findings across clinical studies are mixed. Juneja et al. found no significant association between ASD and CD, with some behavioral symptoms attributed instead to non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) [16]. Lau et al. observed higher anti-gliadin IgG among children with ASD and gastrointestinal symptoms, yet without elevated HLA-DQ2/DQ8, suggesting an immune response that differs from classic CD [17]. Taken together, these data indicate that gluten-related immune phenomena may occur in subsets of children with ASD, but they do not establish a causal ASD–CD link.

Several factors likely contribute to inconsistent results: small sample sizes and variable sex distributions (ASD more common in males; CD more often diagnosed in females), heterogeneous inclusion/exclusion criteria and non-uniform CD definitions (biopsy vs. serology vs. self-report), evolving pediatric CD diagnostic guidelines that may miss undiagnosed cases, and setting bias from inpatient samples where psychiatric symptoms may be over-represented [9,12,18,19]. Case reports describe improvement after initiating a GFD following confirmed CD diagnosis [20], and similar small observational reports exist [7,21], but these designs limit generalizability.

In children with ASD without confirmed CD, routine initiation of a GFD is not recommended given uncertain benefit and potential risks, including dietary restriction in already selective eaters, micronutrient insufficiency, and added psychosocial/financial burden.

Evidence quality/heterogeneity: Most ASD–CD studies are small, cross-sectional, rely on parent-reported measures, and use variable CD ascertainment, limiting causal inference and generalizability.

4. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Evidence for an association between CD and ADHD is mixed and methodologically variable. Proposed pathways include nutritional deficiencies (iron; B-vitamins including B6, B12, folate; zinc; magnesium; essential fatty acids) that may influence attention and emotion regulation [10], along with immune activation/neuroinflammation and oxidative stress observed in CD, though causal links to ADHD remain uncertain [14,15]. A serotonergic pathway has also been hypothesized: gluten-reactive T-cells can alter tryptophan metabolism, potentially reducing CNS serotonin and downstream melatonin, which may worsen sleep, a recognized contributor to ADHD-like symptoms [11,22,23].

Findings across clinical studies are heterogeneous. Population-level genetic work reports no clear shared genetic architecture between CD and ADHD (e.g., null Mendelian randomization results) [24]. Screening studies have not consistently shown increased biopsy-confirmed CD among ADHD cohorts [10]. Conversely, small intervention reports in diagnosed CD describe improvement in ADHD-like symptoms after ~6 months of a GFD. Still, these studies are small, at risk of bias, and often mix pediatric and adult participants, limiting generalizability [3]. Clinical studies of ADHD traits in pediatric CD likewise show inconsistent elevations and are typically cross-sectional with parent-reported outcomes [25].

When ADHD-like symptoms occur with other features suggestive of CD (e.g., GI symptoms, growth concerns, family history of autoimmunity), screening for CD is reasonable. However, initiating a GFD solely for ADHD in the absence of a confirmed CD is not supported by current evidence.

Evidence quality/heterogeneity: Typical pediatric samples are dozens to low hundreds; designs are often cross-sectional with parent-report measures; and CD ascertainment varies (biopsy vs. serology vs. self-report/NCGS), limiting causal inference.

5. Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) Among Children with Celiac Disease

Research consistently shows a higher burden of anxiety and mood symptoms among children with biopsy-confirmed CD. Large population-based cohorts report an approximately 40% higher risk of anxiety/mood disorders in pediatric CD (adjusted HR ≈ 1.4), with longitudinal follow-up and sibling comparisons helping reduce confounding [12]. These findings fit biologic models involving the gut–brain axis, where intestinal inflammation, microbial imbalance, and increased permeability may contribute to neuroinflammation and altered stress responsivity [5].

Clinically, some children show behavioral improvement after diagnosis and a gluten-free diet (GFD), yet residual anxiety may persist in a subset despite good adherence—suggesting that once neuroimmune changes occur, their effects can be only partially reversible in the short term [6,26]. Delayed diagnosis, ongoing inflammation, and psychosocial stressors (dietary restrictions, feeling “different” at school) likely amplify symptoms.

For children presenting with anxiety alongside GI symptoms, growth issues, or a family history of autoimmunity, CD screening is reasonable. However, starting a GFD without a confirmed CD is not recommended.

Evidence quality/heterogeneity: Strongest signals come from registry-based longitudinal cohorts; nonetheless, residual confounding (e.g., unmeasured family factors, co-occurring conditions) cannot be excluded.

6. Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD)-like Symptoms in Pediatric Celiac Disease

In addition to anxiety, behavioral challenges resembling ODD are commonly seen in children with CD. These include frequent temper outbursts, defiance, irritability, and resistance to authority. Trovato et al. [27] point out that neuropsychiatric symptoms in CD go beyond depression or anxiety and often include impulsivity and disruptive behaviors.

The reasons behind these behaviors are complex. Chronic inflammation and nutrient malabsorption in untreated or poorly managed CD can lead to deficiencies in iron, B vitamins, and other nutrients essential for brain function. These deficiencies can affect neurotransmitter activity, which may impair attention, emotion regulation, and impulse control [11,15]. As a result, some children may struggle with mood swings, difficulty following rules, or reacting aggressively when frustrated. Even children who follow a strict GFD are not always free from these issues. Veeraraghavan et al. [28] observed that around 15% of pediatric CD patients continued to show symptoms despite dietary adherence. For some, these lingering symptoms were linked to comorbid anxiety or depression, while others were misdiagnosed or had overlapping conditions like functional abdominal pain or food aversions. Children who continue to feel unwell or misunderstood may act out through defiance, especially if they feel stigmatized or left out socially. Notably, most reports reflect ODD-like behaviors captured on behavior checklists (e.g., CBCL) rather than interview-confirmed ODD, and samples are typically clinic-based.

The emotional stress of dealing with CD, whether it is being singled out for food restrictions at school or coping with overprotective adults, can worsen oppositional behavior [2,29]. When children feel like their illness controls their lives, they may respond with resistance, anger, or refusal to follow instructions. Over time, these reactions can become ingrained, especially if emotional support is lacking.

Lastly, a study by Wahab et al. [30] showed that even children with positive CD autoimmunity markers, but without obvious gut symptoms, had increased rates of behavioral problems. This highlights a crucial point: behavioral issues in CD may not just come from dealing with the illness itself but might be rooted in the autoimmune activity affecting the developing brain.

Most pediatric CD studies reporting “oppositional” features rely on broad behavior checklists (e.g., CBCL) rather than structured diagnostic interviews; thus, findings often reflect ODD-like behaviors (irritability/defiance) rather than formal ODD diagnoses. Available pediatric samples are small to moderate (tens to low hundreds) and typically clinic-based, introducing selection bias. Taken together, the data support ongoing behavioral monitoring in CD, while underscoring the need for structured diagnostic assessments in future studies.

Evidence quality/heterogeneity: Reports mainly capture ODD-like behaviors on checklists rather than interview-confirmed ODD; samples are typically clinic-based. Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of representative pediatric studies by condition, showing CD ascertainment (biopsy/serology/self-report), design and sample size, key findings, and effect sizes where reported. Labels reflect study design and consistency, not causation. Abbreviations: CD, ASD, ADHD, ODD, GFD, CBCL (Child Behavior Checklist).

7. Strengths and Limitations

This review has several strengths. It highlights how CD affects more than just the gastrointestinal system, drawing on large-scale data such as the Swedish cohort of over 10,000 children, which showed a 1.4-fold higher risk of anxiety, depression, ADHD, autism, and intellectual disability among those with biopsy-confirmed CD [12]. Their unaffected siblings did not show the same issues, suggesting that the disease itself, rather than shared familial or genetic factors, may be responsible. Another strength is the discussion of biological mechanisms, including chronic inflammation, immune system activation, and vitamin deficiencies such as B6, B12, D, E, and folate [7,32]. Antibodies, including tTGA6 and GAD65, may also target the brain, with levels decreasing after adherence to a strict gluten-free diet [32,33]. The review further emphasizes that many children display behavioral changes before diagnosis [12], highlighting the role of the gut–brain axis, chronic inflammation, and psychosocial stressors [6,29,32].

There are also important limitations. Many included studies are small, observational, and cross-sectional, often relying on parent-reported checklists such as the CBCL, which introduces recall bias. In some cases, distinctions between biopsy-confirmed CD, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, and self-reported gluten avoidance were not made [10,16], weakening conclusions. Publication bias, selection bias, and reverse causality (for example, anxiety leading to gastrointestinal complaints and prompting CD testing rather than resulting from CD) further complicate interpretation. Several studies also combine pediatric and adult participants or lack age-stratified data, limiting their relevance to children. Most are cross-sectional, which prevents conclusions about causality. Finally, the review only included English-language publications, reducing generalizability. These limitations underscore the need for large, prospective cohort studies with standardized diagnostic and behavioral assessments. Reverse causality also needs to be considered; for example, anxiety or attentional problems may worsen gastrointestinal symptoms and prompt CD testing, rather than being caused by CD itself.

8. Conclusions

The relationship between CD and social–emotional dysregulation among children is increasingly supported by research. Although the exact mechanisms remain unclear, factors such as nutrient deficiencies, immune responses, gliadorphins, and proinflammatory cytokines, and gut–brain axis are possible pathways. Autoantibodies, such as anti-transglutaminase 6 and anti-Purkinje cell antibodies, may also contribute in genetically predisposed children.

Multiple small observational studies showed that CD among children is associated with higher risks of mood and anxiety disorders, ADHD, and autism spectrum disorder. While links to schizophrenia and panic disorder are less specific, evidence supports viewing CD as a systemic condition with social–emotional dysregulation.

In practice, children with anxiety, attentional concerns, or oppositional features accompanied by GI symptoms, poor growth, or family autoimmunity should be screened for CD using standard serology (and biopsy when indicated). Routine initiation of a gluten-free diet for behavioral symptoms without confirmed CD is not recommended, given the uncertain benefit and potential nutritional/psychosocial burden. These recommendations are consistent with recent pediatric guidelines, including the ESPGHAN Position Paper and the ACG Clinical Guidelines [34,35]. These guidelines emphasize that biopsy-confirmed diagnosis and holistic care that addresses both gastrointestinal and psychosocial outcomes should always be practiced.

Author Contributions

Conceptualizing the study: S.A. and Y.A.; study design: S.A., Y.A., F.M. and G.R.Z.; literature review: S.A., Y.A., F.M., G.R.Z. and S.P.; data extraction: S.A., Y.A., F.M., G.R.Z. and S.P.; drafting and editing: S.A., Y.A., F.M., G.R.Z. and S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There was no fundig for this study by governmental or non-govermental agencies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Akhondi, H.; Ross, A.B. Gluten-Associated Medical Problems. 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538505/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Ilchmann-Diounou, H.; Menard, S. Psychological Stress, Intestinal Barrier Dysfunctions, and Autoimmune Disorders: An Overview. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederhofer, H.; Pittschieler, K. A Preliminary Investigation of ADHD Symptoms in Persons with Celiac Disease. J. Atten. Disord. 2006, 10, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Magistris, L.; Familiari, V.; Pascotto, A.; Sapone, A.; Frolli, A.; Iardino, P.; Carteni, M.; De Rosa, M.; Francavilla, R.; Riegler, G.; et al. Alterations of the Intestinal Barrier in Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorders and in Their First-degree Relatives. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2010, 51, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, A. Celiac disease, gut-brain axis, and behavior: Cause, consequence, or merely epiphenomenon. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20164323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.B.; Lynch, K.F.; Kurppa, K.; Koletzko, S.; Krischer, J.; Liu, E.; Johnson, S.B.; Agardh, D.; TEDDY Study Group. Psychological Manifestations of Celiac Disease Autoimmunity in Young Children. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20162848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Leffler, D.A.; Bai, J.C.; Biagi, F.; Fasano, A.; Green, P.H.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Kaukinen, K.; Kelly, C.P.; Leonard, J.N.; et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut 2013, 62, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Murray, J.A. Epidemiology of Celiac Disease. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 48, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcia, G.; Posar, A.; Santucci, M.; Parmeggiani, A. Autism and Coeliac Disease. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2008, 38, 407–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumperscak, H.G.; Rebec, Z.K.; Sobocan, S.; Fras, V.T.; Dolinsek, J. Prevalence of Celiac Disease Is Not Increased in ADHD Sample. J. Atten. Disord. 2020, 24, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernanz, A.; Polanco, I. Plasma precursor amino acids of central nervous system monoamines in children with coeliac disease. Gut 1991, 32, 1478–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butwicka, A.; Lichtenstein, P.; Frisén, L.; Almqvist, C.; Larsson, H.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Celiac Disease Is Associated with Childhood Psychiatric Disorders: A Population-Based Study. J. Pediatr. 2017, 184, 87–93.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zingone, F.; Swift, G.L.; Card, T.R.; Sanders, D.S.; Ludvigsson, J.F.; Bai, J.C. Psychological Morbidity of Celiac Disease: A Review of the Literature; SAGE Publications Ltd: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgic, B.; Aygun, D.; Arslan, A.B.; Bayram, A.; Akyuz, F.; Sencer, S.; Hanagasi, H.A. Silent neurological involvement in biopsy-defined coeliac patients. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 34, 2199–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojiljković, V.; Todorović, A.; Pejić, S.; Kasapović, J.; Saičić, Z.S.; Radlović, N.; Pajović, S.B. Antioxidant status and lipid peroxidation in small intestinal mucosa of children with celiac disease. Clin. Biochem. 2009, 42, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juneja, M.; Venkatakrishnan, A.; Kapoor, S.; Jain, R. Autism Spectrum Disorders and Celiac Disease: Is there an association? Indian Pediatr. 2018, 55, 912–913. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, N.M.; Green, P.H.; Taylor, A.K.; Hellberg, D.; Ajamian, M.; Tan, C.Z.; Kosofsky, B.E.; Higgins, J.J.; Rajadhyaksha, A.M.; Alaedini, A. Markers of Celiac Disease and Gluten Sensitivity in Children with Autism. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, S.; Parma, B.; Morabito, V.; Borini, S.; Romaniello, R.; Molteni, M.; Mani, E.; Selicorni, A. Celiac disease in autism spectrum disorder: Data from an Italian child cohort. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2023, 49, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madra, M.; Ringel, R.; Margolis, K.G. Gastrointestinal Issues and Autism Spectrum Disorder; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genuis, S.J.; Bouchard, T.P. Celiac Disease Presenting as Autism. J. Child Neurol. 2010, 25, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pynnönen, P.A.; Isometsä, E.T.; Aronen, E.T.; Verkasalo, M.A.; Savilahti, E.; Aalberg, V.A. Mental disorders in adolescents with celiac disease. Psychosomatics 2004, 45, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erland, L.A.; Saxena, P.K. Melatonin Natural Health Products and Supplements: Presence of Serotonin and Significant Variability of Melatonin Content. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, Q.; Li, L.; Xue, Z. Celiac disease and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1291096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassoff, J.; Wiebe, S.T.; Gruber, R. Sleep patterns and the risk for ADHD: A review. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2012, 4, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Efe, A.; Tok, A. A Clinical Investigation on ADHD-Traits in Childhood Celiac Disease. J. Atten. Disord. 2023, 27, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collin, P.; Kaukinen, K.; Mattila, A.K.; Joukamaa, M. Psychoneurotic symptoms and alexithymia in coeliac disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 43, 1329–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trovato, C.M.; Raucci, U.; Valitutti, F.; Montuori, M.; Villa, M.P.; Cucchiara, S.; Parisi, P. Neuropsychiatric manifestations in celiac disease. Epilepsy Behav. 2019, 99, 106393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeraraghavan, G.; Therrien, A.; Degroote, M.; McKeown, A.; Mitchell, P.D.; Silvester, J.A.; Leffler, D.A.; Leichtner, A.M.; Kelly, C.P.; Weir, D.C. Non-responsive celiac disease in children on a gluten free diet. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slim, M.; Rico-Villademoros, F.; Calandre, E.P. Psychiatric Comorbidity in Children and Adults with Gluten-Related Disorders: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, R.J.; Beth, S.A.; Derks, I.P.; Jansen, P.W.; Moll, H.A.; Kiefte-de Jong, J.C. Kiefte-De Jong. Celiac Disease Autoimmunity and Emotional and Behavioral Problems in Childhood. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20183933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, M.T.; Abdo, Q.; Jaber, M.M.; Qatanani, A.A.; Raba’a, A.O.; Rabba, G.F.; Deeb, S.W.; Jallad, S.; Badrasawi, M. Eating behaviors and mental health among celiac patients, case-control study. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 44, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionetti, E.; Francavilla, R.; Pavone, P.; Pavone, L.; Francavilla, T.; Pulvirenti, A.; Giugno, R.; Ruggieri, M. The neurology of coeliac disease in childhood: What is the evidence? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2010, 52, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Reutfors, J.; Ösby, U.; Ekbom, A.; Montgomery, S.M. Coeliac disease and risk of mood disorders—A general population-based cohort study. J. Affect Disord. 2007, 99, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearin, M.L.; Agardh, D.; Antunes, H.; Al-toma, A.; Auricchio, R.; Castillejo, G.; Catassi, C.; Ciacci, C.; Discepolo, V.; Dolinsek, J.; et al. ESPGHAN Position Paper on Management and Follow-Up of Children and Adolescents with Celiac Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2022, 75, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Tapia, A.; Hill, I.D.; Kelly, C.P.; Calderwood, A.H.; Murray, J.A. ACG Clinical Guidelines: Diagnosis and Management of Celiac Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 108, 656–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).