Abstract

This study re-examines generational differences in media literacy and news consumption within the evolving digital landscape. It expands on the well-known dichotomy of Digital Natives and Digital Immigrants by proposing a new conceptual framework that introduces the terms Analog Anchors and Digital Floaters. These terms aim to reflect the heterogeneity and fluidity more accurately, the adaptive nature of users’ engagement with digital media. A quantitative survey was conducted using an online questionnaire distributed to Greek participants (N = 1020) through a non-probability convenience sampling method. The analysis revealed significant variations in digital literacy, news consumption habits, and skepticism toward the media across generations. Findings indicate that the relationships with technology and information are not linear or age-bound but are shaped by cultural, cognitive, and social parameters. High levels of media skepticism observed across all age groups further challenge traditional divides. As a result, this study argues for a paradigm shift that captures the complexity of media literacy in the platform era, moving from static generational labels towards a more dynamic understanding of users as Analog Anchors and Digital Floaters.

1. Introduction

At first, it is clarified that Bawden (2001) defined digital literacy as the ability of a person to read and manage information in the various “hypertextual” and “multimedia” formats in which that information is available. The concept of Media and Information Literacy (MIL) refers to the ability to understand available information, regardless of how it is presented (Pangrazio et al., 2020; Reddy et al., 2020).

In contemporary society, readers are increasingly categorized using generational labels commonly found in the international literature, such as the Millennial Generation, the Web Generation, or Digital Natives. The term Digital Natives, introduced by Prensky (2001), refers to individuals who have grown up in a digital environment where interaction with computers and technological advancements is pervasive.

Digital Natives are those who have experienced the widespread integration of the internet into everyday life, alongside the continuous use of mobile phones, video games, multimedia devices, and other digital applications. This term predominantly describes members of the Millennial generation, as well as individuals belonging to Generation Z and Generation Alpha. Notably, the latter two generations are often characterized as Neo-Digital Natives, True Digital Natives, or Digital Integrators (Muleya et al., 2019). At the same time, Williams and Phillips (2025) argue that overly simplistic binary distinctions—such as those between Digital Natives and Digital Immigrants—fail to capture the complexity and diversity of digital experiences.

Despite ongoing debate regarding the usefulness of this dichotomy (Williams & Phillips, 2025), the differentiated patterns of behaviour documented between younger and older users remain relevant. These distinctions provide a useful point of departure for examining generational dynamics in the context of contemporary news engagement.

Recent research further suggests that even when the empirical differences that exist between generational groups are weak, the generational identities may remain meaningful. As Lee and Hartanto (2025) argue, generational labels are considered cultural identity markers. They shape expectations, stereotypes, and cross-generational interactions. From this perspective, the persistence of generational distinctions means their symbolic and interpretive value. In this framework, the present study does not aim to dismiss generational labels altogether. It aims to reposition them in a broader and cross-generational understanding of media engagement.

Ohme (2019) argues that Digital Natives often encounter information unintentionally, as news exposure is seamlessly embedded within their everyday interactions on social media. Similarly, Silveira (2020) notes that social media platforms function not only as spaces for social connection but also as the primary gateways through which younger users access news.

These environments prioritize immediacy and algorithmic personalization, ultimately shaping a mode of news consumption that is rapid, fragmented, and closely intertwined with peer communication. As a result, news for Digital Natives is not solely cognitive content; it also constitutes an ongoing expression of social belonging and personal identity.

In contrast, Digital Immigrants tend to engage with information in a more structured and context-dependent manner. For example, Rojas Torrijos and Garrote Fuentes (2025) observe that older users rely more heavily on institutionally recognized sources and display a preference for linear, coherent information flows. Consequently, they adopt practices that foreground credibility, professionalism, and editorial accountability.

This tendency aligns with Jarrahi and Eshraghi’s (2019) assertion that, for older generations, the use of technology is often the outcome of deliberate learning rather than natural immersion. As a result, Digital Immigrants’ news behaviours are shaped by conscious selection processes and an intensified focus on verification cues. This pattern is also reflected in Sterna’s (2018) argument that this group perceives digital tools as purpose-specific instruments rather than seamlessly integrated elements of everyday life.

These generational contrasts are further evident in the domain of digital literacy. Dingli and Seychell (2015) emphasize that Digital Natives have grown up in environments where digital technologies permeate all aspects of daily activity. This lifelong exposure results in higher levels of technical fluency and an intuitive ability to navigate digital platforms.

However, Menichelli and Braccini (2020) argue that familiarity with digital environments does not necessarily translate into advanced source evaluation skills or heightened resistance to misleading content. This suggests that the strengths of Digital Natives—namely speed and adaptability—may coexist with notable vulnerabilities in critical judgement.

Conversely, Digital Immigrants tend to report lower levels of technological confidence, even though they often demonstrate comparable or, in some cases, superior performance in reflective information processing. Anzak et al. (2021) examine the importance of technological self-perception in digital participation and note that older users’ assessments of their own digital competence are shaped largely by socio-cultural narratives rather than by their actual skill level.

Similarly, Creighton (2018) argues that stereotypes surrounding older adults’ presumed “digital illiteracy” influence how they perceive their abilities, potentially leading to an underestimation of their competence. This outcome may occur despite their frequently more deliberate and methodical engagement with information.

Furthermore, Adjin-Tettey (2020) observes that Digital Natives tend to engage with news through the lenses of identity, social justice, and personal meaning-making. They frequently integrate mediated content into broader processes of social self-construction. Their affiliation with digital communities further strengthens the internalization of media narratives as tools of socialization, particularly regarding issues such as gender, human rights, and climate change—a pattern also highlighted by Pandit et al. (2025).

In contrast, Digital Immigrants tend to interpret news through more institutionalized and analytically driven frameworks. Osgerby (2020) argues that, for this group, news consumption remains closely tied to notions of civic responsibility and democratic functioning. Similarly, Manor and Kampf (2022), along with Rojas Torrijos and Garrote Fuentes (2025), emphasize that older adults exhibit higher levels of reflective reasoning, especially concerning the cultural implications of technologically mediated communication.

Regarding skepticism, it should be noted that this phenomenon manifests in multiple forms, ranging from outright rejection of information to critical distancing and the search for alternative sources. Skepticism is continually evolving within the contemporary digital environment (Kyriakidou et al., 2023). The concept is closely tied to the perception that news may be biased, discriminatory, or distorted. It reflects citizens’ concerns that the media do not objectively represent reality but instead filter events through political, economic, or ideological interests (Lakew & Olausson, 2019). As Kyriakidou et al. (2023) further emphasize, skepticism is intensified by the increasing complexity of today’s information landscape.

In terms of generational differences, Digital Natives and Digital Immigrants exhibit distinct skepticism profiles toward media content. Jung (2025) and Martin et al. (2022) note that Digital Natives tend to direct their skepticism toward institutional sources, which they often view as potentially biased. Consequently, their trust is more frequently oriented toward peer-generated content—a tendency also identified by Bărbuceanu (2020). More specifically, Bărbuceanu (2020) argues that Digital Natives interpret news within the broader context of digital identity formation and participatory culture.

In contrast, Digital Immigrants demonstrate a different pattern of skepticism, expressing greater caution toward unregulated platforms and user-generated, non-professional content. This tendency aligns with the concerns raised by Nelissen and Van den Bulck (2018) regarding the erosion of institutional journalism and the challenges posed by alternative news ecosystems.

Moreover, Xiao and Yang (2024) argue that critical skepticism can enhance individuals’ ability to filter and interpret information, provided it is accompanied by sufficient knowledge and evaluative skills. Within this framework, the differences between Digital Natives and Digital Immigrants do not indicate higher or lower levels of skepticism per se. Instead, they reflect qualitatively distinct epistemological orientations toward information.

This study aims to identify the differences between Digital Immigrants and Digital Natives in the following areas:

- Their preferences and habits in consuming news content.

- Their knowledge of digital literacy.

- Their levels of digital literacy.

- Their beliefs concerning the cultural influence audiences of the news they receive.

- Their skepticism toward the news they consume.

To address this objective, the following research questions are posed:

RQ1. News Content Consumption: How do Digital Immigrants differ from Digital Natives in their preferences and habits regarding news consumption?

RQ2. Digital Literacy Knowledge and Levels: (a) How do Digital Immigrants differ from Digital Natives in their knowledge of digital literacy? (b) How do Digital Immigrants differ from Digital Natives in their levels of digital literacy?

RQ3. Cultural Influence and News Attitudes: (a) How do Digital Immigrants differ from Digital Natives in their beliefs about the audience’s cultural influence on news content? (b) How do Digital Immigrants differ from Digital Natives in their skepticism toward news content?

Based on the empirical patterns that are identified, this study further proposes a new typology in place of digital immigrants and digital natives. This is the new typology of “Analog Anchors” and “Digital Floaters” accordingly.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study employed a quantitative research methodology. Accordingly, the primary data collection instrument was a questionnaire, which was designed and distributed entirely via the Google Forms online platform. This approach enabled the rapid, cost-effective, and wide dissemination of the research tool to diverse population groups across Greece.

The data collection process sought to examine the differences and similarities between Digital Immigrants and Digital Natives in terms of their news consumption patterns, levels of digital literacy, skepticism, and cultural attitudes toward contemporary media. Further details regarding the research instrument and its structure are presented in the next subsection.

2.1. Research Sample and Sampling Method

The total research sample consisted of 1020 participants from Greece. Of these, 51.47% identified as women and 48.53% as men. In terms of age, the majority of respondents belonged to the category of Digital Immigrants (i.e., individuals over 35 years old). Specifically, 67.25% of participants fell into this group, while 32.75% were classified as Digital Natives (i.e., up to 35 years old).

With respect to educational attainment, the largest proportion of participants (40.00%) were graduates of higher education institutions, holding a university degree, vocational qualification, or college diploma. Regarding professional status, the most common occupational category was full-time private-sector employment, reported by 36.86% of respondents. In addition, 50.59% stated that they were married, indicating a predominance of individuals with family commitments and stable partnerships, while 48.53% reported having no children.

The distribution of participants by area of residence revealed a significant predominance of the urban population. Specifically, 85.00% indicated that they lived in urban areas with more than 10,000 inhabitants. Moreover, the largest income group among respondents (31.57%) reported an individual monthly income between €1001 and €1500, reflecting a middle socioeconomic status.

The research sample was selected using a convenience sampling method, which falls under the category of non-probability sampling techniques. This method was chosen due to its practicality and the ease with which volunteer participants could be recruited via the internet. It was also deemed the most appropriate approach given the time constraints and limited resources available during the conduct of the study.

Although convenience sampling presents certain limitations, particularly with regard to the generalizability of findings, it remains suitable for examining correlations, attitudes, and emerging trends within the selected sample. It is also appropriate for generating interpretive insights, as noted by Creswell and Creswell (2018).

The composition of the present research sample reflects the age categories associated with the concepts of Digital Natives and Digital Immigrants, as defined in the preceding literature review. This age-based classification enabled a comparative analysis of participants’ perceptions, attitudes, and practices regarding news consumption across generational groups.

2.2. Research Tool

The research instrument employed in this study is a structured questionnaire comprising both closed-ended questions and items assessed on a 5-point Likert scale. It is organized into six thematic sections, each corresponding to a distinct area of investigation. The questionnaire was designed to ensure clarity in both structure and wording, thereby facilitating participants’ full comprehension of each item’s meaning and requirements.

The first section of the questionnaire collects demographic information from respondents. Classification into the categories of Digital Natives or Digital Immigrants is based on participants’ self-reported age. Individuals aged 35 years or younger are categorized as Digital Natives, as they were born and raised during a period marked by the daily use of mobile phones, video games, the internet, and digital applications, according to Prensky’s (2001) framework. Conversely, participants aged 35 and above are classified as Digital Immigrants—individuals who were not born into the digital world but who have adopted many aspects of modern technology.

The second section examines participants’ news preferences and consumption habits through multiple-choice items and 5-point Likert scale questions. This section had been developed based on previous studies that had examined platform-based news access and incidental exposure (Ohme, 2019; Silveira, 2020; Rojas Torrijos & Garrote Fuentes, 2025).

The third section assesses participants’ knowledge of digital literacy using similar formats. The items of this section were informed by conceptual approaches that distinguish between technical fluency and critical information-processing skills (Dingli & Seychell, 2015; Menichelli & Braccini, 2020).

The fourth section measures participants’ level of digital literacy using the internationally recognized Technology Integration Confidence Scale (TIC). Participants were asked to evaluate their confidence in completing specific technology-integration tasks on the following scale: 1 = Not at all confident, 2 = A little confident, 3 = Somewhat confident, 4 = Quite confident, 5 = Very confident, 6 = Absolutely confident.

The fifth section explores respondents’ perceptions of the cultural influence of news content, again through multiple-choice and Likert-scale items. Statements examining perceptions of cultural influence were grounded in literature addressing news as a carrier of cultural meaning and identity formation (Osgerby, 2020; Adjin-Tettey, 2020).

The sixth and final section asks participants to evaluate a series of statements using the following scale: 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither agree nor disagree, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly agree. Representative statements include: “News reports may differ in how they present an event due to variations in political preferences.” “Journalists’ political beliefs can influence the way they present a news story.” “In news reports, events are presented so vividly that you feel as if you are experiencing them yourself.”

These items assess participants’ levels of skepticism. In this study, skepticism refers to distrust and critical attitudes toward news-production processes, including perceived political or economic influence, potential bias, and the subjectivity inherent in news presentation. Also, skepticism-related items were informed by previous research on media skepticism, news bias, and critical distancing to the mediated communication (Lakew & Olausson, 2019; Kyriakidou et al., 2023; Xiao & Yang, 2024).

2.3. Data Collection

The selection of the data collection method was based on a strategy that relied exclusively on online recruitment, using Google Forms as the primary distribution tool. Google Forms provided substantial advantages, including automated data recording and storage, as well as the ability to disseminate the questionnaire widely within a short period. Additionally, the online format facilitated the preservation of participant anonymity.

Data collection took place over the course of one year. During this period, the questionnaire was circulated gradually through the researcher’s personal contacts, email communication, and posts or announcements on social media platforms. Particular emphasis was placed on promoting the questionnaire via LinkedIn, a professional and academic-oriented platform whose users were expected to demonstrate a higher degree of engagement and seriousness.

Participants completed the questionnaire through a hyperlink, without the need to provide personal information or passwords. Access to the questionnaire was unrestricted, and respondents retained the freedom to discontinue or refrain from submitting their responses at any point. To enhance the validity of the dataset, Google Forms’ “one response per user” setting was activated. Although this restricted participation to individuals with a Gmail account, it effectively prevented multiple submissions by linking responses to users’ personal accounts. It is also mentioned that the design and implementation of the questionnaire adhered fully to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Code of Ethics and Research Conduct of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

Upon completion of the data collection phase, the dataset was exported to Excel and subsequently imported into the SPSS statistical software package (version 23) for analysis. The initial analytical procedures included data cleaning, verification for duplicate or incomplete submissions, and coding of variables for statistical testing. Descriptive statistics, comparative analyses, and inferential statistical tests were then conducted to develop a clear overview of the findings and assess relationships among the key variables under investigation.

Inductive statistical tests were accompanied by the necessary assumption checks. Specifically, the normality of variable distributions was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and Q–Q plots, both of which confirmed the normal distribution of the data. Additionally, Levene’s test was employed to verify the equality of variances, ensuring the appropriate application of t-tests in the subsequent analysis.

2.4. Research Ethics

From the outset, the principle of voluntary participation was strictly upheld. Participants were not subjected to any form of pressure or coercion and took part solely on their own initiative. Their access to the questionnaire was entirely open, without the requirement of identifiable information or passwords.

Regarding participants’ autonomy, safeguards were implemented both in terms of their decision to participate and their right to withdraw from the research at any time. Additionally, an extensive informational text was provided at the beginning of the questionnaire, clearly outlining the purpose of the study, its academic orientation, its non-profit character, and the anonymous nature of respondents’ participation.

This informational text served as an informed consent mechanism, enabling participants to understand in advance the focus of the research, the potential risks involved, and the manner in which the research data—specifically their questionnaire responses—would be used. Voluntary acceptance on the part of each participant, demonstrated through the active initiation of questionnaire completion, was taken as an indication of consent.

It should be noted that at no point during data collection were personal or sensitive data requested. The questions focused exclusively on issues related to digital media use, attitudes toward news, and levels of digital literacy, while the demographic variables collected—such as age, gender, educational level, and country of residence—were recorded in a fully generalised and non-identifiable form.

Through these measures, the anonymity and confidentiality of participants’ responses were fully preserved. Additionally, all data were processed without the use of names, IP addresses, email addresses, or any other form of personal information.

3. Results

3.1. Digital Literacy

To assess the suitability of the research sample for factor analysis, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) index and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were first employed. The KMO value was calculated at 0.963, which is characterised as “excellent” according to the relevant literature. This value indicates that the sample size is adequate and that the variables demonstrate a high degree of intercorrelation—an essential prerequisite for conducting factor analysis.

Simultaneously, Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded a statistically significant result (Approx. Chi-Square = 24,693.68, df = 190, p < 0.001), confirming the rejection of the null hypothesis that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix. In practical terms, this finding indicates that the variables are sufficiently related to justify proceeding with the factor analytic procedure.

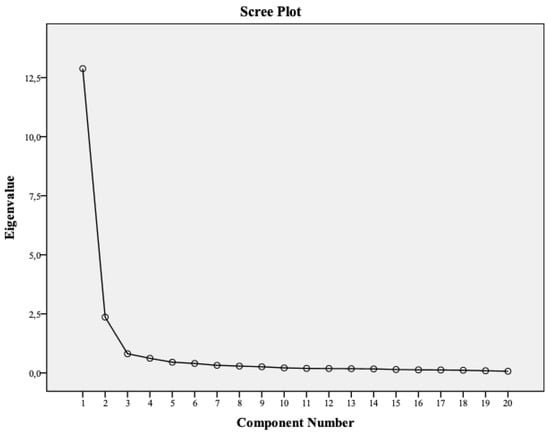

Subsequently, a factor analysis was carried out to examine the structure of the Technological Integration Confidence Scale (TIC). The inspection of the Scree Plot (Figure 1) clearly suggests the presence of a dominant factor, as evidenced by the sharp decline in eigenvalues after the first factor and the gradual flattening of the curve, forming the characteristic “elbow” in the diagram.

Figure 1.

Scree Plot—digital literacy factor analysis.

The shape of the Scree Plot (Figure 1), combined with the high internal consistency of the scale (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.971), indicates that the twenty items of the TIC scale represent a single underlying dimension measuring confidence in technology integration. Therefore, no further subdivision into separate subscales is deemed necessary.

The measurement of digital literacy was based on the values derived from the overall scale, as determined through the preceding factor analysis. According to the results presented in Table 1, the mean digital literacy score is 4.32, with a standard deviation of 1.27. This mean score places participants above the midpoint of the scale, indicating a relatively high perceived level of competence and confidence in the use of digital technologies.

Table 1.

Digital literacy.

3.2. Skepticism Toward Media

Initially, it is noted that the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient for the 15 skepticism statements is 0.733, a value that indicates satisfactory internal consistency of the scale. The KMO index is 0.83, which is considered very satisfactory, as values above 0.80 suggest that the correlations among the variables are sufficiently strong to support the use of factor analysis. Furthermore, Bartlett’s test of sphericity returned a statistically significant result (Chi-Square = 3575.66, df = 105, p < 0.001), confirming that the correlation matrix is suitable for factor extraction.

Based on the results of the factor analysis (Table 2), the data were found to cluster into two main factors. The first factor was labeled Skepticism and includes statements expressing doubt regarding the impartiality and objectivity of news reporting. The second factor, labeled Non-Skepticism, consists of statements reflecting a more positive or neutral attitude toward the capacity of news media to provide adequate and balanced information.

Table 2.

Factor analysis for skepticism.

This two-factor structure highlights a clear conceptual distinction between individuals who adopt a critical stance toward news content and those who perceive it in a more neutral or less questioning manner.

Following this analysis, mean values and standard deviations were calculated for the two factors that emerged, namely Skepticism and Non-Skepticism. The mean value of the Skepticism index is 3.92 with a standard deviation of 0.68 (Table 3), indicating that participants generally exhibit relatively high levels of doubt and critical thinking regarding news media and the way events are presented.

Table 3.

Skepticism and non-skepticism.

In contrast, the mean value of the Non-Skepticism index is 2.26 with a standard deviation of 0.69 (Table 3), suggesting that participants do not tend to accept news content uncritically and do not display elevated levels of uncritical acceptance or indifference toward potential distortions in the information presented.

The difference in mean values between the two factors is substantial and demonstrates that, within the present research sample, a more critical and skeptical stance toward the media predominates.

3.3. Differences in News Consumption, Digital Literacy, and Skepticism

Table 4 presents the results of the one-way ANOVA analysis between the different age groups, in news access, platforms, and modes of consumption.

Table 4.

One-way ANOVA results by age group with direction of differences in news access, platforms, and modes of consumption (N = 1020).

Table 5 presents the results of the one-way ANOVA analysis between the different age groups, in news interests, participation, and engagement.

Table 5.

One-way ANOVA results by age group with direction of differences in news interests, participation, and engagement (N = 1020).

Table 6 presents the results of the one-way ANOVA analysis between the different age groups, in news evaluation, literacy trust, and skepticism.

Table 6.

One-way ANOVA results by age group with direction of differences in news evaluation, literacy trust, and skepticism (N = 1020).

4. Discussion

4.1. News Content Consumption (RQ1)

The majority of Digital Natives reported a high frequency of accessing news through social media and other digital applications. This finding supports the view that information consumption in this age group is often incidental rather than the result of purposeful content seeking, as indicated by Ohme (2019). Furthermore, it confirms Silveira’s (2020) assertion that the use of digital platforms such as Instagram and TikTok serves not only social interaction purposes but also functions as a primary channel for news dissemination.

In contrast, Digital Immigrants appear to maintain a more structured relationship with information. The findings of the present research indicate that their approach is characterized by a conscious and deliberate selection of news sources. This is consistent with the position of Rojas Torrijos and Garrote Fuentes (2025), who note that Digital Immigrants place greater emphasis on the structure and sequencing of information, as well as on their preference for institutionally recognized media outlets. As supported by Jarrahi and Eshraghi (2019), the use of technology among Digital Immigrants is largely the result of intentional learning and training; therefore, it is reasonable that the present study observed higher levels of critical thinking and caution within this group.

The present research also confirmed the generational differences in modes of news reception. More specifically, Digital Immigrants show a preference for news content originating from institutional sources and distributed within clearly defined temporal routines. Digital Natives, by contrast, receive information in a more fragmented manner, integrated into their ongoing social interactions. As highlighted by Sterna (2018), Digital Immigrants tend to perceive technology as a tool with a clearly defined purpose and context of use.

What is significant in these findings is not the confirmation of generational differences in news access. It is the way these differences reflect different relationships with information. In more analysis, the fragmented and socially integrated news exposure that had been observed among the younger users challenges the hypothesis that the frequency of access is translated into the depth of engagement. This means that high exposure is able to coexist with reduced opportunities for contextualization and reflection.

At the same time, the persistence of structured and routine-based news practices in the older users’ case is worth mentioning. More analytically, rather than showing resistance to digital change, it is a pattern that might indicate a deliberate strategy for informational stability.

4.2. Digital Literacy Knowledge (RQ2a)

According to the results of the present research, Digital Natives generally exhibited higher levels of fluency in the technical use of digital media. This finding supports the view of Dingli and Seychell (2015), who argue that this generation has developed within environments where technology is naturally and continuously integrated into all aspects of daily life.

However, the present study also demonstrated that this high level of technical proficiency is not always accompanied by equivalent levels of critical literacy. In other words, although Digital Natives display increased ability in locating information and considerable ease in using technological tools, they continue to face difficulties in evaluating the credibility of sources and in recognizing misleading content. This observation confirms the argument of Menichelli and Braccini (2020), who highlight that familiarity with the digital environment does not equate to the development of advanced critical information-processing skills.

In contrast, Digital Immigrants—despite lagging in technical fluency or speed in performing digital tasks—demonstrated higher levels of conscious and reflective processing of the information they encountered. Although their practical performance in some cases was comparable to that of Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants reported lower levels of confidence in their digital abilities. This finding aligns with the observations of Anzak et al. (2021), who note that technological self-perception significantly influences individuals’ participation in digital environments as well as their willingness to assume new digital roles.

4.3. Digital Literacy Assessment (RQ2b)

More specifically, Digital Natives scored higher averages of digital literacy. This finding reflects their increased self-confidence in the use of digital tools. This is justified by the view of Evans and Robertson (2020), which emphasizes that their familiarity with technology from a young age enhances the naturalness of their use.

On the contrary, Digital Immigrants, despite often demonstrating satisfactory or even high performance in the use of basic technological applications, declared significantly lower levels of confidence. This research finding is in line with the conclusions of Anzak et al. (2021), according to which the technological self-confidence of Digital Immigrants does not depend solely on their practical competence, but is also influenced by the perception of themselves as ‘outsiders’ in digital environments.

Nevertheless, the lower technological confidence of Digital Immigrants is not a sign of inadequacy. It is an element that highlights the significant influence of the social and cultural context in shaping the self-image of digital users. As pointed out by Creighton (2018), their self-perception is influenced by prejudices and stereotypical perceptions of the ‘digital illiteracy’ of older people.

An important implication of these findings is the distinction that exists between perceived competence and critical capability. More analytically, while younger participants have higher levels of confidence in digital environments, this self-assurance is not translated into increased evaluative judgment. This tension means the existence of a paradox that might be frequently overlooked in the discussions on digital literacy.

Conversely, the lower self-reported confidence in the case of the older users should not be mentioned as evidence of digital inadequacy. On the contrary, it means the powerful role of socio-cultural narratives that surround age and technology. These shape individuals’ self-perceptions irrespective of their actual performance.

4.4. Cultural Influence Attitudes (RQ3a)

The findings of the present research indicate that Digital Natives are more strongly influenced by the aesthetics, communicative style, and thematic framing of news content. This group places particular emphasis on issues related to identity, social justice, and personal self-expression. For Digital Natives, information does not function solely as a cognitive resource; rather, it also serves as a tool for social integration, participation, and the construction of emerging social identities—a pattern consistent with the observations of Adjin-Tettey (2020).

The close and continuous engagement of Digital Natives with social media and digital communities further reinforces their tendency to internalize digital content as a central component of their socialization. As highlighted by Pandit et al. (2025), this influence is especially evident in thematic areas such as gender, identity, human rights, the climate crisis, and social inclusion.

Conversely, Digital Immigrants demonstrate a markedly different pattern of cultural engagement with news content. Their relationship with information is shaped to a greater extent by traditional communication models and a more analytical, institutional, and linear interpretation of news. This aligns with Osgerby (2020), who argues that for Digital Immigrants, news functions primarily as a means of cultivating political and social awareness within a framework anchored in institutional credibility and democratic processes.

Moreover, as noted by Manor and Kampf (2022) and Rojas Torrijos and Garrote Fuentes (2025), Digital Immigrants exhibit a higher degree of critical reflection concerning the cultural implications of technological mediation.

An especially notable finding of the present study concerns the distinct ways in which the two age groups are culturally influenced by news. Digital Natives tend to integrate elements of digital culture into their personal and collective identities, whereas Digital Immigrants interpret the cultural impact of news predominantly through concepts of institutional trust, informational reliability, and educational significance.

4.5. Skepticism (RQ3b)

According to the findings of the present study, Digital Natives expressed notably high levels of skepticism. As suggested by Jung (2025) and Martin et al. (2022), this skepticism appears to stem from a cautious stance toward institutional and traditional news sources, which are often perceived by younger audiences as politically biased, economically dependent, or detached from the real needs and concerns of society. Instead, Digital Natives tend to place greater trust in peer-to-peer information channels and social media platforms, even when these sources lack professional journalistic oversight.

This trend aligns with the argument of Bărbuceanu (2020), who emphasizes that, for Digital Natives, information is interpreted within the broader framework of digital identity and social participation, rather than viewed as an autonomous cognitive product.

In contrast, Digital Immigrants also demonstrated elevated levels of skepticism, although it was directed differently compared to the younger group. Their distrust was primarily oriented toward content disseminated through informal, unregulated digital platforms. Older participants reported limited trust in news originating from non-governmental organizations or non-professional sources, expressing concerns about insufficient documentation, the absence of journalistic accountability, and the widespread circulation of unverified claims. This pattern is consistent with Nelissen and Van den Bulck (2018), who argue that Digital Immigrants’ skepticism is largely driven by the perceived threat posed by the shift from institutional journalism to the mass production of content by unvetted and self-appointed “journalists.”

A particularly noteworthy finding concerns the distinct ways in which both groups conceptualize skepticism—as a mechanism of protection rather than as a devaluation of information itself. As confirmed by Xiao and Yang (2024), critical skepticism can serve as a constructive tool for filtering and interpreting information, provided it is supported by sufficient knowledge, metacognitive awareness, and evaluative competencies. In the context of this study, Digital Immigrants exhibited more consistent evidence of applying such critical mechanisms. Conversely, Digital Natives appeared to rely more heavily on emotional and experiential criteria when determining the trustworthiness of information.

The above-mentioned findings mean that skepticism should not be treated as a unidimensional indicator of distrust. It should be treated as a differentiated epistemic stance, that is shaped by users’ media environments and literacy resources. Also, the fact that both age groups showed elevated skepticism challenges simplistic narratives that equate skepticism with disengagement or cynicism.

5. Conclusions

The findings of the present study revealed substantial differences between age groups in terms of digital literacy, news consumption habits, and levels of skepticism. These results confirm that individuals’ relationships with technology are not uniform; rather, they are shaped by cultural, cognitive, and social factors, as well as by users’ digital literacy and degrees of critical skepticism. Notably, high levels of skepticism were observed across both age groups.

Regarding the limitations of the study, the non-probabilistic sampling procedure relied primarily on the accessibility and availability of individuals who received the questionnaire. This approach may have resulted in a partial representation of the wider population, particularly with respect to its socio-demographic characteristics. In addition, the online distribution of the research tool increases the possibility of self-selection bias. Also, the sampling method that was followed may possibly have caused potential biases, which are related to education level, socioeconomic status, and digital familiarity. This comes as a result of online recruitment and LinkedIn-based dissemination. Another important limitation concerns the study’s narrow focus on news-related practices and attitudes toward information. Other significant dimensions of digital engagement—such as entertainment, education, or professional uses of technology—were not examined, despite their potential influence on the development of digital identities.

In light of the above limitations, several directions for future research are recommended. First, the use of mixed research methods—such as incorporating qualitative interviews or focus groups alongside quantitative questionnaires—could provide deeper insight into participants’ subjective experiences and motivations. Second, the adoption of more representative sampling techniques would strengthen the generalizability of future findings. Third, including a broader range of age groups and professional categories would allow for a more nuanced exploration of how cultural background interacts with digital literacy levels.

It is important to clarify that the categories of Analog Anchors and Digital Floaters are not presented as statistically derived clusters, based on cluster analysis. Instead, they constitute an interpretive typology. This typology is based on empirical patterns that are observed across the dimensions of these research findings, including news consumption routines and skepticism profiles.

More specifically, the proposed typology came from the co-occurrence of behaviours and attitudes that had been identified in the analysis. A characteristic example is stable versus platform-fluid news practices. Another example is the differences in the emphases on ethical credibility versus technological adaptability and the distinct forms of critical engagement with mediated information. Taking these results into consideration, Analog Anchors and Digital Floaters are analytical constructs that synthesize recurring empirical tendencies, rather than mutually exclusive demographic groups.

In conclusion, based on the findings of this study and their interpretation within the existing theoretical framework, a revised conceptual typology of digital news media users is proposed. Specifically, it is suggested that the longstanding distinction between Digital Immigrants and Digital Natives—although historically useful in its original context (Prensky, 2001)—is now scientifically and empirically inadequate. This critique is consistent with the arguments of Williams and Phillips (2025), who highlight the limitations of age-based categorization as the sole criterion for differentiating digital user groups.

Advances in the field of Digital and Information Literacy (Media and Information Literacy—MIL), combined with the empirical evidence from the present research, underscore the need for a more dynamic and multidimensional typology. Such a framework should account for users’ habits, levels of critical thinking, and both functional and value-driven forms of engagement with digital news media.

Based on the empirical findings of this study, which revealed substantial differences in the ways individuals consume, access, evaluate, and engage with news—differences that extend beyond age—the dichotomous typology of Analog Anchors (i.e., Digitally Conservative Users) and Digital Floaters (i.e., Digitally Flexible Users) is proposed. This typology preserves the simplicity and communicative clarity of the traditional Digital Natives/Digital Immigrants distinction, while integrating the cultural, cognitive, and technological dynamics that characterize contemporary news users.

More specifically, Analog Anchors constitute a category of individuals who remain connected to traditional forms of information such as print, television, and radio. Their preference cannot be attributed solely to age or technological familiarity; rather, it is shaped by value-oriented, cognitive, and emotional factors, including trust in source validity and a desire for informational stability.

In contrast, Digital Floaters represent users with a strong and continuous presence in digital environments. They exhibit high mobility across platforms, consume news through multiple channels, and display a willingness to experiment with new forms of information and journalism, including emerging digital formats.

This proposed terminology is further substantiated by the finding that Digital Floaters tend to develop mainly the cognitive and aesthetic dimensions of digital literacy, whereas Analog Anchors prioritize the emotional and ethical dimensions, choosing news sources based on credibility, emotional coherence, and traditional evaluations of truth.

Within the interpretive model introduced in this paper, digital and news literacy are approached in relation to consumption frequency, depth of information processing, and the value frameworks that guide user behaviour. More precisely:

Analog Anchors correspond to news users who: approach information through structured, linear processes (structured learning), emphasize cultural literacy, prioritize credibility and ethical standards in selecting news sources.

Digital Floaters, by contrast, are news users who: display high mobility across platforms, develop skills related to misinformation detection and data verification (detect & alert), actively participate in content creation and redesign through tools such as artificial intelligence, gamification, and augmented reality.

Beyond its analytical contribution, the proposed typology offers practical implications for revising digital literacy strategies in both educational contexts and policymaking. In particular, Analog Anchors may benefit from pedagogical approaches that build trust in digital verification tools, whereas Digital Floaters require further cultivation of ethical boundaries, critical judgment, and mechanisms for preventing the spread of misinformation.

Table 7 presents a brief comparison between the two typologies.

Table 7.

Comparison between the two typologies.

Also, it is mentioned that the empirical patterns that had been identified in this study might be further shown through the already existing theoretical frameworks, such as Uses and Gratifications Theory and Media Dependency Theory. For example, from a uses and gratifications perspective, younger users’ platform-fluid practices can be understood as motivated by needs for immediacy and identity expression. These motivations align with the profile of Digital Floaters. Besides, Digital Floaters’ media use is characterized by adaptability and continuous movement across platforms.

On the other hand, Media Dependency Theory offers a useful base for interpreting the practices of the Analog Anchors’ case. For instance, their preference for stable news sources means the existence of a stronger dependency on media systems that offer predictability and credibility. Therefore, this dependency functions as a strategy for holding informational control.

Finally, although the empirical analyses in this study are organized around age-based comparisons, age is treated primarily as an analytical starting point. This means that it is not treated as a sufficient explanatory variable. The purpose of the age-centered analysis is to show recurring patterns in the news practices, in the literacy orientations, and in the skepticism profiles that cut across chronological categories. It is precisely the co-occurrence of these patterns that motivates the shift that exists toward the interpretive typology of Analog Anchors and Digital Floaters. Therefore, the proposed typology is not contradicted by age-based analyses. On the contrary, it is shown as a means of capturing dimensions of media engagement that age itself is not able to adequately explain.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised 2013). According to the institutional and national regulations governing non–interventional social-science research in Greece, ethics committee approval is not required for studies that: involve minimal risk, collect anonymous and non-sensitive data, do not involve clinical procedures or vulnerable populations. This exemption is aligned with the legal framework for social research and the policies of my institution (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adjin-Tettey, T. D. (2020). Can ‘digital natives’ be ‘strangers’ to digital technologies? An analytical reflection. Inkanyiso: Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 12(1), 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzak, S., Sultana, A., & Fatima, A. (2021). Impact of digital technology on the health and social well-being of digital natives. Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 9(3), 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawden, D. (2001). Information and digital literacies: A review of concepts. Journal of Documentation, 57(2), 218–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bărbuceanu, C. D. (2020). Teaching the digital natives. Revista de Științe Politice. Revue des Sciences Politiques, 65, 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Creighton, T. B. (2018). Digital natives, digital immigrants, digital learners: An international empirical integrative review of the literature. Education Leadership Review, 19(1), 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dingli, A., & Seychell, D. (2015). The new digital natives. JB Metzler. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, C., & Robertson, W. (2020). The four phases of the digital natives debate. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(3), 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrahi, M. H., & Eshraghi, A. (2019). Digital natives vs. digital immigrants: A multidimensional view on interaction with social technologies in organizations. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 32(6), 1051–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S. (2025). Social media natives perceive mediated communication as optimal communication: The roles of social media starting age and its usage. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 41(10), 6450–6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidou, M., Morani, M., Cushion, S., & Hughes, C. (2023). Audience understandings of disinformation: Navigating news media through a prism of pragmatic scepticism. Journalism, 24(11), 2379–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakew, Y., & Olausson, U. (2019). Young, sceptical, and environmentally (dis)engaged: Do news habits make a difference? Journal of Science Communication, 18(4), A06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D., & Hartanto, A. (2025). A cultural identity approach to the generational divide. New Ideas in Psychology, 79, 101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manor, I., & Kampf, R. (2022). Digital nativity and digital diplomacy: Exploring conceptual differences between digital natives and digital immigrants. Global Policy, 13(4), 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. D., Hassan, F., Anghelcev, G., Abunabaa, N., & Shaath, S. (2022). From echo chambers to ‘idea chambers’: Concurrent online interactions with similar and dissimilar others. International Communication Gazette, 84(3), 252–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichelli, M., & Braccini, A. M. (2020). Millennials, information assessment, and social media: An exploratory study on the assessment of critical thinking habits. In Exploring digital ecosystems: Organizational and human challenges (pp. 85–97). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Muleya, G., Simui, F., Mundeende, K., Kakana, F., Mwewa, G., & Namangala, B. (2019). Exploring learning cultures of digital immigrants in technologically mediated postgraduate distance learning mode at the University of Zambia. Zambia ICT Journal, 3(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelissen, S., & Van den Bulck, J. (2018). When digital natives instruct digital immigrants: Active guidance of parental media use by children and conflict in the family. Information, Communication & Society, 21(3), 375–387. [Google Scholar]

- Ohme, J. (2019). When digital natives enter the electorate: Political social media use among first-time voters and its effects on campaign participation. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 16(2), 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgerby, B. (2020). Youth culture and the media: Global perspectives. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pandit, M., Magadum, T., Mittal, H., & Kushwaha, O. (2025). Digital natives, digital activists: Youth, social media and the rise of environmental sustainability movements. arXiv, arXiv:2505.10158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangrazio, L., Godhe, A. L., & Ledesma, A. G. L. (2020). What is digital literacy? A comparative review of publications across three language contexts. E-Learning and Digital Media, 17(6), 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants part 1. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P., Sharma, B., & Chaudhary, K. (2020). Digital literacy: A review of literature. International Journal of Technoethics (IJT), 11(2), 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas Torrijos, J. L., & Garrote Fuentes, Á. (2025). The factuality of news on Twitter according to digital qualified audiences: Expectations, perceptions, and divergences with journalism considerations. Journalism and Media, 6(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, P. (2020). Fake news consumption through social media platforms and the need for media literacy skills: A real challenge for Z Generation. In INTED2020 proceedings (pp. 3830–3838). IATED. [Google Scholar]

- Sterna, M. (2018). Digital natives vs. digital immigrants. Zeszyty Glottodydaktyczne, 8, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, S., & Phillips, B. (2025). Investigation of the diverse factors that shape one’s digital identity. Available online: https://digital.library.ncat.edu/honorscollegesymposium25/39/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Xiao, X., & Yang, W. (2024). There’s more to news media skepticism: A path analysis examining news media literacy, news media skepticism and misinformation behaviors. Online Information Review, 48(3), 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.