Abstract

Conservative media have been shown to exert disproportionate levels of influence over other mainstream media agendas. This study explores the outsized influence of Australia’s conservative media during the 2023 Australian Voice to Parliament referendum on other news agendas and, in turn, the impact on public and political agendas. Combining conservative advocacy, agenda-setting, and frame-building theories, this study uses content analysis of news frames included in Australian news reports about the Marcia Langton “racism” controversy. The influence of conservative media frames on other news media reporting and political and public responses to the controversy is conceptualised as a self-propelling agenda feedback wheel, fuelled by deliberate media advocacy. By having an outsized influence on the rest of the Australian media’s reporting of the racism controversy, News Corp also influenced the public and political referendum debate. These findings add new insights into how conservative media power is used to influence other media and, in turn, democracy.

1. Introduction

Increasingly, studies have shown that conservative media wield a disproportionate level of influence over the news agenda of other media outlets. In their analysis of media coverage of the UK’s “Brexit” European Referendum in 2016, Deacon et al. (2016) found 60% of articles published by ten major newspapers supported the ‘Leave’ campaign and 40% supported ‘Remain’. When weighted for circulation, articles taking a ‘Leave’ position had a circulation of 80%, as compared to Remain articles with a circulation of 20% (Deacon et al., 2016). Amongst these pro-Leave newspapers, Gaber (2024) describes Rupert Murdoch’s The Sun, then the UK’s most popular newspaper, as a cheerleader for an extreme Brexit position, continuing the newspaper’s long tradition of advocating for a Eurosceptic mindset. Where such studies show the dominance of the pro-Brexit position amongst British newspapers, particularly popular tabloids known for their right-wing partisanship, the UK’s broadcast news outlets are notionally not partisan because they are regulated to ensure they present a balance of diverse perspectives (Phillips, 2019). However, Phillips (2019, p. 142) argues that despite these regulations, right-wing newspapers set the pro-Leave agenda for the issues covered by broadcast media, including the public broadcaster BBC, demonstrating broadcast outlets are ‘not immune from the pressures of well-capitalised campaigns emanating’ from right-wing media. Cushion et al. (2018) similarly highlighted the intermedia agenda-setting power of right-wing newspapers in finding that the majority of policy stories by broadcast media during the 2015 UK Election were first published in right-wing newspapers. In a study of online media coverage of the 2016 US election, Faris et al. (2017, p. 16) also describe right-wing media as playing a key role in ‘setting the agenda of mainstream, center-left media’, an agenda that focused on negative coverage about Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton.

This study explores conservative media’s outsized influence on other media and, in turn, their powerful effect on political and public agendas. This analysis draws on and adds to the literature in the following three research fields:

- conservative advocacy, where news media power is used to advocate for conservative positions in democratic debates;

- agenda setting, to understand how this conservative advocacy is a form of active agenda building, which has an intermedia agenda-setting effect;

- frame-building theory, which helps to explain the interaction between advocacy frames, more passive journalistic frames, and public opinion.

Through this theoretical synthesis, this paper conceptualises a self-propelling agenda feedback wheel, which is proposed to be fuelled by deliberate media advocacy. This framework adds new insights into how conservative media power is used to influence other media and, in turn, democracy.

The democratic contest analysed in this study is the 2023 Australian referendum, which asked the public to decide if they supported enshrining an Indigenous Voice to Parliament in the national constitution (‘the Voice’). The referendum was an election pledge by the centre-left Labor Party ahead of the 2022 federal election. Supporters of the Voice proposed that it was a practical way to recognise Australian First Nations people in the constitution via an advisory body that would offer advice to the government about policies aimed at closing the gap in life outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (ANU, 2023). However, the conservative Opposition Coalition, comprising the federal Liberal and National parties, formally opposed the Voice proposal, and most members of these parties actively campaigned for a ‘No’ vote against the proposition. Despite polls showing broad support for the Voice proposal before the referendum campaign began (Evershed & Nicholas, 2023) and a survey by the Australian National University after the referendum finding 87 percent of voters supported the concept of an Aboriginal advisory body (Biddle, 2023), the Voice was defeated, with 60 percent of Australians opposing the referendum change.

Opinion polling research conducted during the referendum by Accent Research (2023) asked respondents what their three most important reasons for voting No were and found the predominant ‘most important’ reason, cited by 82 percent as at least one of their main reasons, was that the Voice ‘will divide Australia’ along the lines of racial grounds and racial privileges. The accusation that the Voice was a divisive proposition was a key argument of the No campaign, as per this quote by a key opponent of the Voice, conservative Liberal leader Peter Dutton:

“This thing is permanent, it‘s divisive, it hasn’t been properly explained and it’s not going to provide the practical outcomes that we want to see for all Indigenous Australians.”(Armstrong, 2023)

The No campaign had a powerful ally in the propagation of its argument that the Voice divided Australia: Australia’s largest media organisation, Murdoch-owned News Corp Australia. News Corp holds a commanding position in Australia, the most concentrated media institution in the Western world, with an approximate 60 percent share of the print news market (Gaber & Tiffen, 2018). As Australia’s only mainstream national masthead, The Australian newspaper has been argued to have a particularly strong agenda-setting influence on other media reporting and political agendas (Manne, 2011; McKnight, 2003). Australia’s Murdoch media, like in the US and UK, is also well known for its conservative, right-wing partisanship (McKnight, 2013). The author (Fielding, 2023) suggests that this partisanship is more than mere bias towards right-wing and conservative interests but rather constitutes conservative advocacy journalism.

Advocacy journalism is defined by Fielding (2023) as different from the traditional liberal model of news media used in anglosphere media systems, which is characterised by journalists notionally reporting independently, passively, objectively, and in a balanced way. Advocacy journalism, instead, is a form of journalism that is not balanced, is subjective, active, and takes positions in parallel to political and social causes (Fielding, 2023). When advocacy journalism is used to champion the voices of marginalised people, groups, and causes who struggle to have their voices heard in the public sphere, Fielding (2023) defines this advocacy journalism as radical advocacy, which is theorised to be democratically productive. Contrastingly, as in the case of Murdoch’s News Corp, when news media advocates for people, groups, and interests who already hold power, they are defined as conservative advocates. This conservative advocacy is argued to be negative for democracy because it is used to further marginalise those who challenge power; conservative advocacy uses media power to reinforce existing power structures (Fielding, 2023).

Murdoch media’s conservative advocacy was evident during the Voice referendum. Fielding et al. (2025b) studied News Corp’s reporting about the Voice by analysing 1613 pieces of content across thirteen weeks of the referendum campaign published by four major outlets: national broadsheet newspaper The Australian, tabloid newspapers the Daily Telegraph and Herald Sun, and cable broadcast outlet Sky News. They found that amongst all the Voice referendum arguments platformed by these outlets, 68 percent supported the No campaign (Fielding et al., 2025b). Of these No arguments, the most common theme platformed by News Corp was that the Voice divided Australia, insinuating that the Voice was divisive along racial lines (Fielding et al., 2025b). Fielding et al. (2025b) concluded that News Corp was more than partisan or biased in their representation of the Voice but rather actively advocated for the No campaign in concert with No campaign spokespeople.

The No campaign and News Corp’s claim that the Voice divided Australia was particularly emphasised in the last month before the referendum after Indigenous leader, academic and Yes campaigner, Professor Marcia Langton, was reported by The Australian to have called No voters “racist” and “stupid” during a Yes campaign event, under the headline: ‘Langton brands No voters ‘racist, stupid’. The Guardian reported that The Australian changed this headline on their online newspaper without a formal retraction when Langton pointed out that she had been misquoted, having not accused No voters of racism, but rather the No campaign of using “stupid and racist claims” in their tactics (Butler, 2023b). A screen print of the original The Australian headline accusing Langton of calling voters racist was promoted by politicians supporting the No campaign, including Peter Dutton (Butler, 2023b).

Langton’s accusation that the No campaign was propagating racist tactics continued to be extensively framed by News Corp as controversial and problematic for the Yes campaign, with this framing implying Langton was victimising Australian voters by accusing them of racism. Other media outlets also followed News Corp’s lead by framing Langton’s comments negatively, with very few interrogating the other side of the story, such as analysing whether Langton’s criticism of the No campaign’s tactics as racist had any validity. The resulting media storm forced prominent Yes campaigners, including Labor government politicians, to criticise or distance themselves from Langton—again reinforcing her original comments as negative and unjustified in media coverage. The media agenda towards Langton’s comments was thus presented to news audiences near-homogenously as inherently divisive and unjustified. Such framing reinforced the No campaign’s claims that the Voice itself was inherently divisive.

This case study of News Corp’s representation of Langton’s comments in support of the No campaign and its influence on other media’s agendas raises important questions about the influence of such conservative advocacy on democratic contests. In particular, this study builds on the concept of advocacy journalism by characterising such advocacy as active and deliberate agenda-building (Arceneaux et al., 2024), akin to the agenda-building practices of strategic communicators who deliberately frame their public communication to serve their advocacy goals. New Corp’s active media agenda building, which framed the Voice as “divisive”, is proposed to have fuelled a self-propelling agenda feedback wheel between News Corp’s conservative advocacy and other media outlets, which ultimately negatively influenced public opinion about the Voice proposal and impeded the momentum of the Yes campaign. Although this feedback wheel was initially generated by News Corp’s advocacy, the influence on the political and public agenda is not proposed to have been linear. Rather, at times, the media agenda indirectly exerted pressure on the political agenda through public opinion, and at other times, the media agenda directly influenced the political agenda. The mechanism of this feedback wheel adds new understanding to the process by which conservative advocacy creates an imbalance and establishes momentum in news agendas and framing. Consequently, this imbalance and momentum disproportionately impact public and political agendas and exert media power beyond the News Corp audience. The following sections establish a theoretical framework synthesising studies of conservative media, agenda setting, and frame building before presenting an empirical analysis of the Langton case to inform new understanding of the powerful influence of conservative advocacy during democratic debates.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conservative Media Advocates

This research is interested in the practices and political influence of conservative media. Like Fielding et al.’s (2025b) argument that News Corp deliberately advocated for the No campaign during the Voice referendum, many other studies of conservative media also find that outlets like Fox News and Breitbart deliberately frame news and commentary in a way that advantages the political interests of conservative politicians (Bard, 2017; Benkler et al., 2018; Yang & Bennett, 2022). Although most studies of conservative media are US-based, conservative media in the UK and Australia, including outlets owned by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp, are comparably partisan towards right-wing causes and ideology (Deacon et al., 2016; Manne, 2011; McKnight, 2003). In Australia, News Corp is particularly powerful, holding a majority share of the print news market (Gaber & Tiffen, 2018). As such, although there are left-leaning outlets such as The Guardian in Australia that partake in radical advocacy, such as advocating for more action on climate change (Fielding, 2025), there are no outlets in Australia engaged in radical advocacy that are comparable to News Corp in terms of size or influence. This Australian study, therefore, contributes to conservative media scholarship by examining how conservative media influence not just the agendas and frames they present to their own audiences, but also those of other mainstream news outlets, with its results proposed to be applicable to conservative media operating across Western news markets.

There is a large field of research interested in the complex dynamics of media effects; that is, how media consumption affects the views and behaviour of audiences (Bryant & Finklea, 2022). Related to advocacy journalism, media effects research is interested in the influence of partisan media on partisan audiences, with partisan media suggested to contribute to growing political polarisation (Levendusky, 2024). One such study found right-wing Fox News and left-wing MSNBC attack their political opposition, which is argued to contribute to their audiences holding more negative views of their political opposition, trusting them less, and being less open to bipartisanship (Levendusky, 2013). There are also some scholars who argue that in the modern media landscape, since audiences can selectively expose themselves to media that aligns with their existing perspectives—such as partisan political views that align with the partisanship of the media—media does little more than reinforce existing views (Peterson et al., 2021). Gavin (2018), on the other hand, suggests that even if the media is only reinforcing views, this is a discernible and powerful media effect as it leaves audiences less open to changing their existing opinions, an effect that could decide the outcome of close democratic contests.

Emphasising this complexity, there are studies of media effects that find conservative media both shape and reinforce conservative values amongst their audience (DiMaggio, 2022; Martin & Yurukoglu, 2017). For instance, Hoewe et al. (2020) found Fox News viewers were more likely to support policies that restricted immigration, even when controlling for ideology and other news use, whereas viewing MSNBC and CNN was not influential on policy preferences. Broockman and Kalla (2022) tested the impact of Fox News viewers watching CNN for four weeks, finding that this change had a significant moderating impact on audience beliefs and attitudes, including allowing them to learn information that conflicts with their political views. Another study measured racial attitudes relating to an identical news report by comparing news depicting the CNN, Fox News, and no logo (Bell et al., 2022). The inclusion of the Fox News logo was found to lead White audiences to be more discriminatory towards Black people and more sympathetic to White people, suggesting conservative media signifiers act as ‘an ideological or even racialized prime’ (Bell et al., 2022). Yang (2025) suggests many conservative outlets, including Fox News, operate more like political organisations than news outlets. Where such studies convincingly show conservative media are influencing the political views of their own audiences, this study adds new ideas about the influence of conservative media advocacy on the coverage of non-conservative media and, in turn, wider political views beyond their own audiences.

2.2. Political Agenda Setting

Scholars have long been interested in the relationship between media, political, and public agendas, and particularly, as suggested by Dearing and Rogers (1996, pp. 22–23), ‘why the salience of an issue on the media agenda, public agenda, and policy agenda increases or decreases’. Historically, news media have been characterised as the key ‘agenda setters’; by choosing what to report about, news media have been viewed as an alert system for politicians, raising awareness about issues that the public will likely expect them to respond to (Sevenans, 2017). Through this alert function, news media are proposed to operate ‘like search engines constantly producing signals from society’ (Vliegenthart et al., 2016, p. 285). Several studies have demonstrated a link between issues that feature prominently on the news media agenda and issues that are prioritised by politicians (Edwards & Wood, 1999; Eshbaugh-Soha & Peake, 2005). The link between the media agenda and political priorities has been found to subsequently influence the level of political effort expended towards an issue—parties actively respond to favourable media coverage and retreat when media coverage does not fall in their favour (Van der Pas, 2014, p. 243).

Scholarship also suggests that political actors set media agendas. Agenda setting has been viewed as a way for politicians to put issues on the public agenda to solve societal issues (Wolfe et al., 2013) and as a way for political actors to place highly salient issues on the media agenda to advance their own interests (Elmelund-Praestekaer & Wien, 2008). However, Bartholome et al. (2015) found that in some instances, news media frames can actually usurp those originally set by political communicators. Gilardi et al. (2022) identified a close relationship between the media agenda and the social media agenda of political actors but found that ‘overall no agenda leads the others more than it is led by them’ (Gilardi et al., 2022, p. 41). Such studies demonstrate the complexity of the field, suggesting agendas are not unilaterally set by media or by politicians, but rather agenda setting is a dynamic process influenced by a range of issue-specific variables, differing media practices, and power dynamics.

Despite this complexity, studies regularly identify a link between media agenda setting, political decision-making, and public opinion. Studies have found a direct correlation between the amount of media attention afforded to an issue and its salience for the public (Barberã et al., 2019). Politicians have been found to be acutely aware of the value of media and public attention towards their political agenda, and they equate high levels of media attention towards an issue with similarly strong levels of public opinion regarding the matter (Sevenans, 2017)—indicating a feedback mechanism between the political, media, and public agendas (Tan & Weaver, 2007). Wolfe et al. (2013, p. 186) help to clarify the relationship between media and policy agendas by describing media coverage as both ‘an input and an output of the political system’. Further elaborating on the symbiotic relationship between political, media, and public agendas, Langer and Gruber (2021) identified a feedback loop between strategic political communicators amplifying an issue, government figures being forced to respond, and sustained media attention further reinforcing the salience of an issue on the public agenda, a phenomenon they describe as a ‘media storm’.

2.3. Media Agenda Setting: Not a Passive Process

Yet, amongst this diverse range of agenda-setting studies, there is little attention paid to the origins of the news media’s agenda. For instance, Vesa et al. (2015) found that politicians tend to overestimate the media’s influence on the political agenda, yet the basis of the media’s agenda was not explored. Similarly, while Sevenans (2017) found that the media exerted a small but significant influence over the political agenda, the source of the media’s agenda was also unclear. This lack of attention is proposed to stem from the assumption that media agenda setting occurs passively. This assumed passivity derives from the normative values of Western liberal-pluralist news media, including neutrality, objectivity, independence, and balance (Christians et al., 2009). Through this lens of journalistic neutrality and passivity, Elmelund-Praestekaer and Wien (2008) argue there exists a mutually beneficial relationship between news media and political actors, whereby the news media are explicitly viewed as neutral and passive agenda setters who give politicians a way to ‘link a current problem to prefabricated solutions which the parties are just awaiting an occasion to promote’ (Elmelund-Praestekaer & Wien, 2008, p. 263). This study builds on such scholarship by proposing that, in some cases, issues are deliberately placed on the media agenda through advocacy journalism. In these cases, media are not passive agenda setters, but rather are argued to be active agenda builders. Agenda-building ties media advocacy to the fields of strategic communication, public relations, and political communication, where political actors and other elites are proposed to “build” agendas strategically by deliberately placing issues into the media cycle to advance their interests (Arceneaux et al., 2024; Lan et al., 2020; Schweickart et al., 2016). The goal of agenda building is not only to influence how often the media talk about an issue—referred to as first-level agenda-building but also how the issue is talked about—second-level agenda building (Arceneaux et al., 2024), with second-level agenda building related to strategic framing.

Strategic agenda building is often discussed in relation to media agenda setting. For example, Wolfe et al. (2013, p. 181) suggest that issue advocates use media coverage strategically to “help” the media frame issues advantageously in line with their policy positions. In such analysis, journalists are assumed to be influenced by strategic communicators and participants in the political system but are not assumed to be aiming to exert their own influence. Yet, the present paper proposes that media can also act as agenda builders, akin to strategic communicators, by using “news” in the form of advocacy journalism, where they advocate for particular interests in order to strategically and deliberately influence political and public agendas. By viewing media advocates as deliberate agenda builders, this raises the question of what influence such agenda building has on the news agendas of other outlets—a factor of intermedia agenda setting.

Intermedia agenda setting rests on the premise that journalists perceive repetition by other news outlets as validation of their news judgement (Cohen, 1963; Vonbun et al., 2015). Traditionally, journalists ‘write primarily for themselves, for their editors, and for other journalists’, and the ‘desire to be unique is far outweighed by the risk of being different and, perhaps, wrong in full view of the nation’ (Shoemaker & Reese, 1996, p. 120). Consequently, news media often operate as a ‘pack’ and engage in ‘group think’ (Matusitz & Breen, 2012). This ‘group think’ influences issue prioritisation amongst journalists, who often feel compelled to report on a story that has been widely reported elsewhere, when ‘a news event is already a big issue in other media outlets and they have to follow the “pack”’ (Bartholome et al., 2015, p. 449). Furthermore, ‘when the media start devoting attention to an issue, a sort of self-propelling mechanism can start up’ (Van Aelst & Walgrave, 2011, pp. 302–303), whereby news reporting repeats the same agenda and framing across mainstream platforms.

Since the rise of digital and social media, intermedia agenda setting has also been proposed to occur between mainstream and social media platforms. For example, Su and Borah (2019) studied intermedia agenda setting between Twitter and traditional newspapers when President Donald Trump withdrew the US from the Paris Agreement on climate change in 2017. They found that Twitter discourse influenced mainstream agendas in the five-day period after the news broke; however, before and after this five-day window, mainstream media dominated agenda-setting on the issue (Su & Borah, 2019). Although not named as intermedia agenda setting, studies have also analysed the flow of misleading and false information between mainstream and social media, finding that sometimes disinformation and conspiracy theories move in a bottom-up way from social media into mainstream news media, and sometimes top-down in the opposite direction (Benkler et al., 2020; Starbird et al., 2023). Fielding et al. (2025a) have built on such work in the context of the Voice referendum to suggest that News Corp Australia outlets legitimised accusations that there was more to the Voice than the Yes campaign was admitting by alleging the Uluru Statement had “hidden pages”. This accusation is argued to have lent mainstream legitimacy to more extreme disinformation spreading offline and online (Fielding et al., 2025a). Such studies suggest that mainstream and social media content is part of an interconnected ecosystem, where ideas, arguments, and agendas flow back and forth, albeit with mainstream media as a dominant force. This collective media agenda across mainstream and social media, and consequent issue momentum, then also exerts significant pressure on the political agenda (Van Aelst & Walgrave, 2011).

Although intermedia agenda setting does not explain the origin of media agendas, it does explain how, once built by conservative advocates like News Corp, an agenda can flow elsewhere in the media ecosystem, amongst mainstream and social media platforms. Just as traditional agenda-setting research tends to assume agendas are set by the media passively, intermedia agenda setting is similarly usually conceived as a passive process by which agendas organically flow throughout different types of media. This study, contrastingly, suggests that deliberate and active intermedia agenda-building acts as a powerful amplifier of an issue beyond the agenda-building outlet itself. Crucially, this agenda-building influences the framing of that issue throughout different types of media, thereby influencing not just what the public gives attention to, but how they interpret it.

2.4. Frame Building

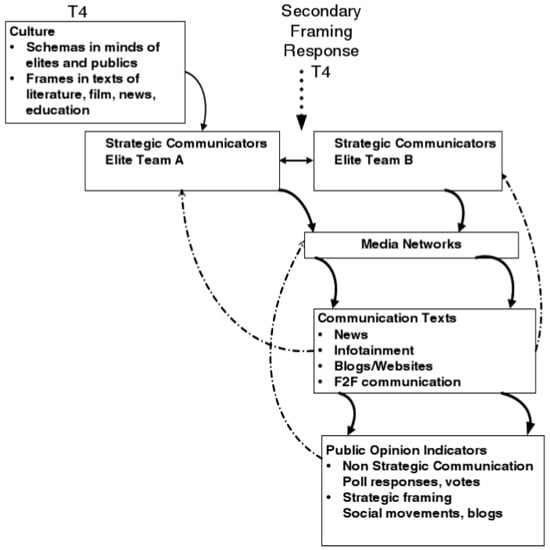

By synthesising agenda-building with frame-building theory, this study helps to explain the process by which the media gives attention to issues, as well as how issues on the media agenda are framed (Entman, 2007; Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007). The complex interplay between the agenda-building efforts of media advocates and media frame-building is discussed using Entman et al.’s diachronic framing process model (Figure 1) (2009).

Figure 1.

The diachronic political framing process (Entman et al., 2009, p. 178).

This model proposes that frames evolve from culture and are influenced by the framing efforts of competing strategic communicators or agenda builders (Entman et al., 2009). These competing frames are theorised to influence news media frame building. The strongest, most dominant of these news frames is then proposed to have the largest influence on public opinion (Entman et al., 2009). Although this model predominantly assumes frames trickle downwards through these framing junctures, it also encompasses feedback mechanisms by assuming public opinion influences news framing and agendas, which in turn influences the communication of strategic actors who recalibrate their frames in response (Entman et al., 2009). The diachronic framing process model thus incorporates the feedback mechanisms described in agenda-setting research between political, media, and public agendas (Tan & Weaver, 2007) and helps to explain how media agenda setting is both an input and output from political communication (Wolfe et al., 2013). However, as shown in Figure 1, this model assumes—like the agenda-setting field—that frames trickle downwards through framing junctures in a passive way. It also assumes that framing inputs from both sides of strategic communicators are finely balanced, like a set of scales, and thus have equal opportunity to impact the media and public agenda. This study interrogates the assumptions about this passive frame-building process by theorising about the influence of active conservative advocacy on news media, political, and public frames.

By integrating scholarship interested in conservative advocacy, agenda setting and building, and frame building, this paper furthers understanding of how a powerful feedback process can be established by conservative media advocacy such as News Corp. This feedback wheel, the mechanism of which is elaborated in the discussion, is proposed to disproportionately influence political and public agendas. This paper, therefore, sheds new light on the outsized influence conservative media advocates like News Corp Australia have on democratic processes.

3. Materials and Method

This study asks: What influence did News Corp’s conservative advocacy have on the collective media agenda in the case of reports about prominent Indigenous Voice Yes campaigner Marcia Langton reportedly calling No voters ‘racist’ and ‘stupid’ during a Yes campaign event? To answer this question, this research uses Van Gorp’s (2010) two-step framing analysis, where frames are first identified inductively in News Corp’s conservative advocacy (frames are not pre-defined but emerge from qualitative analysis), and then frames are analysed deductively in other media reporting (pre-defined frames are qualitatively and quantitatively measured). For the first step, frames are inductively identified in News Corp’s reporting about the Langton case using a sample of news reports from a period of one week from News Corp publications, The Australian, Daily Telegraph, Herald Sun, and Sky News video clips on YouTube. The period 12–18 September 2023 was selected, as this was the week when reports first emerged of Langton’s comments. There was extensive media reporting about Langton’s comments during this period, but the issue dropped off the media agenda after this.

The second step involves deductive quantitative and qualitative analysis to measure the intermedia agenda-setting influence of News Corp’s reporting on other outlets. Although deductive analysis involves the identification of the presence of pre-defined frames, it also allows for new frames to emerge that may not have been present in the News Corp reporting. This quantitative analysis connects framing to agenda setting by measuring the quantity of depictions that presented Langton’s comments either negatively (framing the comments as controversial and problematic for the Yes campaign), positively (framing Langton’s comments as valid and therefore controversial and problematic for the No campaign), or a mix of negative and positive framing. The sample for the second step of analysis used the same period as step one, with reporting sourced from other major mainstream outlets, the public broadcaster ABC News, the independent news outlet The Guardian, and Nine Entertainment masthead publications The Age and Sydney Morning Herald. These findings are then discussed in relation to the public agenda that was set by the media in relation to this news story and the potential impact of this agenda on public opinion about the Voice.

4. Results

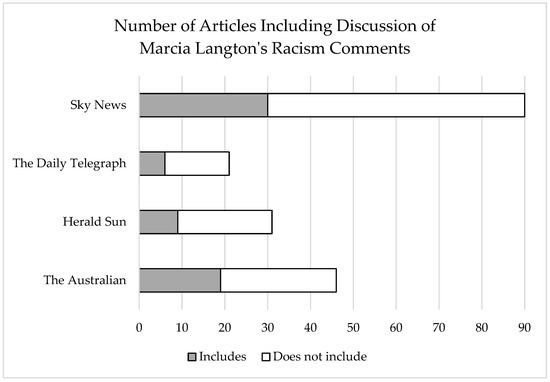

Analysis of News Corp’s coverage of Marcia Langton’s comments alleging racism by the No campaign shows that the news organisation dedicated a large amount of coverage to this news event during the week of 12–18 September 2023, which was a month before the referendum on 14 October. During this week, of the 188 news items about the Voice published by News Corp in The Australian, Herald Sun, Daily Telegraph, and Sky News, 64 (34%) discussed Langton’s comments. Figure 2 shows the prominence given to the story by the four News Corp outlets.

Figure 2.

Number of articles including discussion of Marcia Langton’s racism comments by outlet, 12–18 September 2023.

The first News Corp article about Langton’s comments was originally published by The Australian on 12 September with the headline ‘Langton brands No voters ‘racist, stupid’’. Without correction or explanation, this headline was changed soon after to remove reference to ‘voters’: ‘‘Base racism’: Indigenous voice to parliament Yes leader Marcia Langton in no-holds-barred call’ (Kelly & Lewis, 2023).

As reported in The Guardian, comments made by Langton at an Edith Cowan University event were first reported by the local Bunbury Herald under the headline: “Racist or stupid: voice author slams the no campaign” (Butler, 2023a). A video of Langton’s comments on The Australian’s report (Kelly & Lewis, 2023) showed she had said:

“Every time the No case raises one of its arguments, if you start pulling it apart you get down to base racism. I’m sorry to say it but that’s where it lands. Or just sheer stupidity.”

Langton was reported to have responded to The Australian’s initial headline misrepresenting her comments as directed at voters rather than the No campaign’s tactics by saying: “The media reporting is a very deliberate tactic to make me look like a racist when I’m not,” and “I am not a racist, and I don’t believe that the majority of Australians are racist. I do believe that the no campaigners are using racist tactics” (Butler, 2023a). In this respect, Langton defended her comments as a critique of the substance of the No campaign itself, rather than, as News Corp implied, a personal attack on No voters and campaigners themselves.

In the initial article by The Australian and the extensive News Corp coverage that followed, Langton’s accusation that the No campaign was exhibiting racist tactics was implicitly refuted by being characterised as an unfair and incorrect allegation. Instead, the comments were characterised as evidence that the Yes campaign was making personal attacks and unfairly highlighting racism as a problem during the referendum campaign. Furthermore, the key theme of News Corp’s coverage was of Langton’s comments as a controversial allegation that had caused harm to Langton’s own Yes campaign, rather than the No campaign, which she alleged was using racist tactics. This agenda was evident in the first line of the initial article, which described Labor Government Minister for Indigenous Australians and Yes advocate Linda Burney as having to intervene because of the comments:

Linda Burney has been forced to intervene and call for care and respect from both sides of the voice referendum debate after Marcia Langton accused the No case of racism and stupidity, undermining the Yes campaign’s strategy to win over five million undecided voters (Kelly & Lewis, 2023).

The conflict-driven and negative tone of this coverage is demonstrated in Table 1, which lists the headlines across the four outlets specifically referring to Langton.

Table 1.

Headline sample feature Marcia Langton’s comments, 12–18 September 2023.

Overall analysis of the News Corp coverage of Langton’s comments identified overtly negative framing, particularly emphasising that (1) Langton is problematic (including controversial and divisive) and (2) Langton is a problem for the Yes campaign.

Alongside the extensive negative framing of Langton’s comments, the four News Corp outlets during this week also presented much positive coverage and supportive commentary about No campaigner Jacinta Nampijinpa Price’s speech at the National Press Club. Price, an Indigenous Northern Territory senator from the Liberal-National Coalition Opposition, was one of the key spokespeople for the No campaign. In her National Press Club speech, she claimed that Indigenous organisations were trying to “demonise colonial settlement” in Australia (Butler & Allam, 2023). When asked to clarify these remarks, she said she did not believe Indigenous Australians suffered negative impacts from colonisation, and said colonisation had had a “positive impact, absolutely. I mean, now we have running water, readily available food” (Butler & Allam, 2023). Despite other media reporting that Indigenous people, including Labor Party Minister for Indigenous Australians Linda Burney, found these comments by Price “offensive” (Butler & Allam, 2023), News Corp framed Price as courageous. An example of the way Langton’s comments were juxtaposed negatively by News Corp outlets in contrast to the positive appraisal of Price’s comments was Sky News host Peta Credlin, who stated:

“Australia’s been much better served by someone much less honoured than Langton and that’s Jacinta Nampijinpa Price. The hardest thing is to go against the noisy bullies amongst your own peers. But Price has consistently had the moral courage to do so, it was a tour de force… Her best response was to a loaded question where she simply denied that Aboriginal disadvantage was the result of a colonial past.”(Credlin, 2023)

In this differential characterisation of Langton and Price, News Corp’s coverage consistently framed Langton negatively for alleging the No campaign was using racist tactics while using their support for No campaigners like Price to argue that Indigenous Australians do not suffer from discrimination, racism, or disadvantage because of their race. Such framing underpinned News Corp’s conservative advocacy in support of the No campaign during the Voice referendum (Fielding et al., 2025b). In particular, the accusation that the Yes campaign was behaving in a controversial, negative, and problematic way for making allegations of racism aligned with the official No campaign to claim the Voice itself was divisive, racist, and discriminatory towards non-Indigenous people. This frame suggested that the advisory body gave Aboriginal Australians special privileges not afforded to non-Indigenous Australians, privileges they did not need nor deserve.

The influence of this conservative advocacy on other major Australian news outlets was analysed through quantitative and qualitative analysis of reporting about Langton’s comments by ABC News, The Guardian, Nine publications, The Age, and The Sydney Morning Herald. These outlets devoted only moderate attention to the furore surrounding Langton’s comments, with only 22 original articles published across all of these publications during the week analysed (excluding duplicates). Qualitative and quantitative analysis of this coverage showed that not only did these publications devote less attention by way of news stories to Langton’s comments and the consequent media storm, but the content of these stories was also more muted than News Corp’s. This is evident in the greater number of frames used beyond the two negative frames identified in the News Corp coverage, with Table 2 showing which frames were identified across the coverage and their sentiment regarding Langton.

Table 2.

Frames identified and their sentiment in regard to Langton’s comments.

As per Table 3, when these codes are quantified using negative, positive, or mixed sentiment towards Langton, of the 22 articles, nine were found to be predominantly positively framed towards Langton by either criticising News Corp’s reporting of her comments, scrutinising racist behaviour by the No campaign, or framing the No campaign as problematic, controversial, or hypocritical. Six of the 22 articles were predominantly negative towards Langton, criticising her as problematic and controversial or a problem for the Yes campaign. A further seven articles were evenly split between framing Langton both positively and in a negative light.

Table 3.

Number of articles published by other major news outlets, 12–18 September 2023.

ABC News stories were the least supportive of Langton. Of the seven ABC News articles about Langton’s comments, four were predominantly framed negatively towards Langton for being problematic and controversial, two were evenly split between positive and negative towards Langton, and one was predominantly positive or supportive towards Langton. This compares to only three predominantly negative articles from the Nine newspapers and none from The Guardian. It is noteworthy, however, that even news stories that were critical of News Corp’s representation of Langton’s comments avoided directly criticising News Corp and instead relied on direct quotes from Langton herself, calling out the media misrepresentation of her remarks. With the exception of one (Crabb, 2023), almost all of the nine news stories that were predominantly positive towards Langton still equivocated by criticising or condemning her comments and/or the Yes campaign or asserting that politicians on “both sides” had been subjected to abuse.

Overall, while Nine, ABC, and The Guardian for the most part refrained from engaging in News Corp’s overtly negative coverage of Langton, they nevertheless repeated News Corp’s framing of Langton as controversial or problematic for the Yes campaign. By choosing to adopt News Corp’s agenda and framing of Langton as controversial or problematic, these publications further reinforced News Corp’s predominant agenda and framing throughout the referendum that the Voice was a political problem for Labor (Fielding et al., 2025b) and that the No campaign was not invoking racist tactics.

For instance, an ABC article proclaimed that Albanese had ‘avoided questioning’ regarding Langton’s comments (Roberts, 2023). Illustrating the impact of Langton’s comments on the political agenda, The Guardian asserted that ‘The Coalition had resolved to use the final parliamentary sitting week to go full demolition on the Voice’ (Murphy, 2023). Even an article by Jacqueline Maley in The Age that was strongly critical of News Corp’s pile-on surrounding Langton’s comments, and of Australian conservatives, nevertheless tempered her criticism of the controversy by noting that:

“Langton’s comments were undoubtedly unhelpful to the Yes case—it is perfectly reasonable for voters to have legitimate concerns about constitutional change, and the No campaign is within its rights to appeal to those doubts.”(Maley, 2023)

However, Crabb’s (2023) lengthy article was an outlier amongst the coverage, stridently supporting Langton without equivocating or tempering this support. This ABC article criticised News Corp’s depiction of Langton, scrutinised racist behaviours by the No campaign, and framed the No campaign as problematic. Crabb (2023) explored the basis for racist tropes that she alleged informed other media reporting of Langton’s comments, laying out the hypocrisy of those who view being called racist as more damaging than racism itself:

“when that’s your point of view—if that’s genuinely where you stand—then perhaps you get to a point where you can talk yourself into the idea that being called a racist is more hurtful or damaging or outrageous than being subjected to actual racism … to deny that racist arguments are out there and are being oxygenated by those who should know better is naïve on the very kindest interpretation, and grade-A gaslighting at its worst.”

Altogether, more than half of the stories from other news outlets about Langton’s comments presented Langton fully, or at least partially, negatively—reflecting a transfer of salience via intermedia agenda setting from News Corp’s agenda to the agenda of other Australian news media. In combination with News Corp’s concerted advocacy efforts to build an agenda of Langton as controversial and problematic, the broader Australian news media cumulatively framed Langton’s comments as problematic for the Yes campaign and, as such, created pressure on Labor politicians to respond to the media storm surrounding the comments. The interaction between the media agenda and the political agenda is proposed to have influenced public perception by presenting Langton and, in turn, the Yes campaign in a negative light.

5. Discussion

This study adds new understanding to the influence of conservative media advocates on broader media, political, and public agendas by demonstrating how News Corp’s conservative advocacy coverage of Yes campaigner Marcia Langton’s comments about racism during the Voice referendum had an outsized influence on the political debate, reinforcing negative public opinion towards the Voice. Although other news outlets were not found to precisely mirror News Corp’s aggressive and highly critical framing of Langton, they did passively accept that Langton’s comments were worthy of news coverage—a factor of intermedia agenda setting. Furthermore, where the other outlets were not as negative about Langton as News Corp, their coverage on the whole accepted and reinforced News Corp’s framing of Langton’s comments as politically problematic for the Yes campaign and the Labor government, while, apart from one exception, disregarding whether the No campaign was indeed using racist tactics as Langton alleged.

Other studies have shown, as the diachronic framing process model suggests (Entman et al., 2009), journalists are influenced by political actors and strategic communicators in the broader political system (Wolfe et al., 2013). Research also demonstrates that strategic communicators and political actors build agendas by strategically placing issues into the media cycle, ultimately advancing their interests (Arceneaux et al., 2024; Lan et al., 2020; Schweickart et al., 2016). By synthesising agenda-setting and building theories with the diachronic framing process model (Entman et al., 2009) to evaluate the influence of conservative advocacy journalism, this paper argues that, in this case, rather than being passive disseminators of information, News Corp acted as strategic agenda builders by building an agenda designed to advance the No campaign’s interests. These activities inevitably had an influence on the political and public agenda via the ‘alert function’ role that the media exert on the political agenda. Politicians are known to perceive high levels of media attention as reflective of equivalent public opinion (Sevenans, 2017). News media ‘produce signals from society’ (Vliegenthart et al., 2016, p. 285) that inform the political agenda, creating a flow of agenda filtering from the public to the political agenda via the news media agenda. As per the diachronic framing process (Entman et al., 2009), the agenda and frames built by news media flow not only to the public agenda but also back to the political agenda. ‘Non-strategic frames’ by news media are also shown to influence other news texts within the diachronic framing process (see Figure 1). As such, this study argues that not only did News Corp’s agenda influence other news agendas and framing, but crucially, in contrast to perceptions within the diachronic framing process model that news agendas are established passively, News Corp acted actively and strategically in building an agenda of Langton as controversial and problematic for Yes due to her statements about racism amongst the No campaign. In combination with the predominant frame of the Voice as ‘divisive’ that was emphasised by News Corp throughout the referendum campaign (Fielding et al., 2025b), the agenda built in this case ultimately reinforced public perceptions of the Voice as dividing Australia.

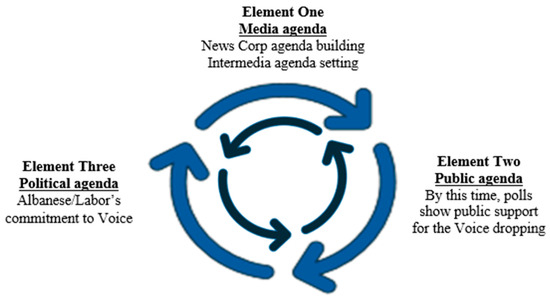

We propose that News Corp’s outsized influence on the referendum political debate can be conceptualised as a self-propelling agenda feedback wheel (see Figure 3). This agenda feedback wheel was established by News Corp’s agenda-building activities in line with their conservative advocacy for the No campaign, which acted as the catalyst for the type of self-propelling phenomenon described by Van Aelst and Walgrave (2011). Once built, this agenda flowed to other media via intermedia agenda setting, reinforcing existing public concerns about the Voice while also exerting pressure on the political agenda. News Corp is proposed to have deliberately built a ‘media storm’ (Langer & Gruber, 2021) by giving saturation coverage to Langton’s comments for the following week. Media storms prompt politicians to play “catch up” and correspondingly shift their agenda in the direction of that set by the media (Walgrave et al., 2017). This media storm had two benefits for News Corp’s No campaign agenda. Firstly, it placed the Yes campaign in a negative frame, reinforcing existing negative public sentiment towards the Voice, and thus indirectly pressuring the political agenda. The media storm also diverted attention away from the substance of Langton’s complaints about racist tactics amongst No campaigners and directly exerted pressure on the political agenda by forcing Labor figures to respond. Via the feedback process, such reporting exerted direct pressure on the political agenda. The media storm and political responses also shaped and further reinforced the public agenda, feeding into News Corp’s broader agenda throughout the campaign that the Voice was divisive and unjustified. This ultimately reinforced public perception that the Voice was divisive, which was cited in opinion polling as at least one of the main reasons for voting No by 82% of participants (Accent Research, 2023), and reflects the level of pressure exerted on the Yes campaign by public opinion in the later stages of the campaign.

Figure 3.

Bi-directional agenda feedback wheel.

The agenda feedback wheel model conceptualised here provides a valuable addition to agenda-setting and frame-building scholarship by explaining how deliberate media advocacy creates imbalance and momentum. For example, Entman et al. (2009) conceived the diachronic framing process model as a system where the positions of the two teams of strategic communicators resemble a set of scales, with competing strategic actors having equal opportunity to input into the media ecosystem, and also assumes that media frames are ‘non-strategic’ (Entman et al., 2009). This study instead proposes that Yes and No campaigners during the Voice referendum did not have equal opportunity to influence the public debate because of the outsized influence of News Corp’s conservative advocacy in support of the No campaign (Fielding et al., 2025b). Such advocacy, in effect, positions News Corp as another strategic communicator engaging in agenda-building activities. This agenda-building had a disproportionate influence on frame-building, creating an imbalance, and hence tipped the scales that are presented in the diachronic framing process model (Entman et al., 2009) as being equally balanced. The resulting imbalance created momentum that propelled the agenda feedback wheel, a process that advantaged the No campaign and disadvantaged the Yes campaign.

The self-propelling feedback wheel outlined here is suggested to operate bi-directionally by gaining momentum and rotational direction according to the level of force that is applied from any one of the following three elements: the media agenda, the public agenda, and the political agenda. While initially ignited by News Corp’s agenda in this case, as described by Van Aelst and Walgrave (2011), it quickly becomes self-propelling. In this case study, it is theorised that the transfer of salience was underpinned by momentum from two elements—the media agenda comprising News Corp’s agenda building and intermedia agenda setting (Element One) reinforcing public opinion of the Voice as divisive (Element Two), combining to apply a high level of force and, thus, negating the momentum of the Yes campaign’s political agenda (Element Three). The momentum established by this feedback wheel makes it challenging for other perspectives to enter the public debate, as alternative perspectives, such as those of the Yes campaign, are forced to play catch-up with the media and political agenda.

The mechanism of this feedback wheel provides further insights to explore conservative media’s outsized impact on public debate in Western democracies such as the US, UK, and Australia. Other studies of conservative media have found conservative media frames news to serve conservative interests (Bard, 2017; Benkler et al., 2018; Yang & Bennett, 2022), and this framing influences and reinforces the conservative views of these outlets’ audiences (Bell et al., 2022; Broockman & Kalla, 2022; DiMaggio, 2022; Hoewe et al., 2020; Levendusky, 2013; Martin & Yurukoglu, 2017). Such studies are interested in how conservative media influence the political opinions and behaviour of their own audiences. This study adds to this scholarship by demonstrating how conservative media power, particularly in the case of organisations like News Corp Australia, which holds a commanding position in a concentrated media market, can extend their media power—their media effect—beyond their own audiences. In the case of Langton’s comments about racism, News Corp is proposed to have successfully used their media power to build an agenda that framed Langton’s comments as a negative political problem for the Yes campaign, which successfully trickled into other media and onto the public and political agenda at a crucial point in the Voice referendum debate.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study have shown how, by building an agenda against the Voice proposal and creating a ‘media storm’ (Langer & Gruber, 2021) surrounding Langton’s “racist” comments, News Corp’s conservative advocacy created momentum for a self-propelling feedback wheel between the media, public, and political agenda during the week of news content analysed in this research. In doing so, this research helps to answer Dearing and Rogers’ (1996) question of why and how particular issues rise or fall in importance on the media, public, and policy agenda. This paper proposes that news media’s agenda-setting and frame-building processes can, in some cases, be explained—as in this study—through conservative media advocacy. Such conservative advocacy challenges the ideas that agenda-setting and frame-building processes occur in a passive, trickle-down process, as implied by the diachronic process model of framing (Entman et al., 2009), and rather proposes that powerful news media outlets can have an outsized influence on political debates, as News Corp did during the Voice referendum.

Although News Corp is characterised as a strategic communicator through their conservative advocacy, agenda building, and strategic framing activities, a news media organisation, particularly one the size of News Corp, cannot be treated as just another actor in the political debate. As suggested by Fielding et al. (2025b) in their description of News Corp’s conservative advocacy during the Voice referendum, News Corp uses the cultural and political legitimacy of mainstream journalism to advocate for political perspectives. In doing so, News Corp uses not only their powerful ownership of publishing and broadcasting platforms as a political weapon but also wields their cultural and political power. This power is the source of their intermedia agenda-setting influence over other news outlets.

In defining conservative advocacy, Fielding (2023) argues that it is negative for democracy because media power is used to champion voices that already have power while marginalising voices that challenge power. The results of this study demonstrate that News Corp’s advocacy during the Voice referendum was not just used to marginalise the Yes campaign—which was advocating for Australia’s marginalised Indigenous population to have a “voice” in parliament—in their own coverage but also had an outsized influence on the coverage of the rest of Australia’s mainstream media. In turn, News Corp had an outsized influence on the public and political referendum debate. News Corp’s conservative advocacy is therefore proposed to have undermined the health of the referendum democratic process by deliberately marginalising the Yes campaign while reinforcing the power—the Voice—of the No campaign, the more powerful group in the referendum amongst the entire media institution. In sum, the self-propelling feedback wheel proposed here—a process of deliberate momentum shift and imbalance—is suggested to be an undemocratic use of News Corp’s media power.

Although this case study is situated in an Australian context, we argue that its results provide fertile ideas to apply in other countries or contexts. For instance, where other studies have argued that conservative media outlets set agendas for non-partisan media in the UK (Cushion et al., 2018; Phillips, 2019) and US (Faris et al., 2017), this study’s Agenda Feedback Wheel framework can be used to explain the mechanism by which conservative media is not just influencing the agendas of other media, but also wider political and public agendas. Furthermore, where this study adds to scholarship interested in conservative media advocacy, scholars could apply the same ideas to explore if a similar feedback mechanism occurs when a progressive outlet deliberately uses radical advocacy to build agendas that influence other media reporting and wider political and public debates. This situation is proposed to be unlikely in media institutions like Australia’s, where conservative media dominates. However, in institutions with more plurality and balance amongst media voices and outlets, radical advocacy could theoretically be just as influential as conservative advocacy.

Moreover, although this research is limited to one case study in the Australian context, the findings align with other scholarship showing that strategic communicators and political actors advance their interests by strategically placing issues into the media cycle to build an agenda (Arceneaux et al., 2024; Lan et al., 2020; Schweickart et al., 2016). More research is needed to better understand the influence of conservative media advocacy on non-conservative media and to examine the machinations of this phenomenon across Western news markets. The Agenda Feedback Wheel proposed here may be applied to understand political contests where there is close alignment between conservative media and conservative political parties, such as in the UK and the US, to better understand the media, political, and public agenda ecosystem in these contexts.

While in this study, momentum was found to turn in the direction of the media, to the public, and ultimately to the political agenda, as Figure 3 demonstrates, the wheel is bi-directional. More research is needed to understand how this feedback wheel can also work in the opposite direction, for example, from the public agenda to the media agenda and ultimately the political agenda.

Lastly, where this study analysed intermedia agenda setting between mainstream media outlets, other studies have suggested there is an intermedia agenda-setting influence between mainstream media and social media (Benkler et al., 2020; Fielding et al., 2025a; Starbird et al., 2023; Su & Borah, 2019). Therefore, this study’s theorising could be applied to studies interested in how mainstream media advocacy influences political debates occurring on social media to understand if and how mainstream outlets expand their power and reach beyond mainstream news audiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; methodology, all authors; formal analysis, all authors; writing—original draft preparation, all authors; writing—review and editing, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Accent Research. (2023). An octopus group accent research report, understanding voter behaviour at the voice referendum: A first look. Available online: https://www.accent-research.com/voice (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- ANU. (2023). Indigenous voice to parliament. Australian National University. Available online: https://www.anu.edu.au/about/strategic-planning/indigenous-voice-to-parliament (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Arceneaux, P., Albishri, O., Anderson, J., & Kiousis, S. (2024). Dynamcis of campaign, press, and public discourse in electoral politics. Journalism Studies, 25(2), 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C. (2023, October 14). Albo in a tearful plea to voters. Daily Telegraph. [Google Scholar]

- Barberã, P., Casas, A., Nagler, J., Egan, P. J., Bonneau, R., Jost, J. T., & Tucker, J. A. (2019). Who leads? Who follows? Measuring issue attention and agenda setting by legislators and the mass public using social media data. The American Political Science Review, 113(4), 883–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bard, M. T. (2017). Propaganda, persuasion, or journalism? Fox News’ prime-time coverage of health-care reform in 2009 and 2014. Electronic News, 11(2), 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholome, G., Lecheler, S., & de Vreese, C. (2015). Manufacturing conflict? How journalists intervene in the conflict frame building process. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 20(4), 438–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A. M., DeSante, C. D., Gift, T., & Smith, C. W. (2022). Entering the “foxhole”: Partisan media priming and the application of racial justice in America. Research & Politics, 9(4), 20531680221137136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benkler, Y., Tilton, C., Etling, B., Roberts, H., Clark, J., Faris, R., Kaiser, J., & Schmitt, C. (2020). Mail-in voter fraud: Anatomy of a disinformation campaign. Berkman Center Research Publication No. 2020-6. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3703701 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Biddle, N. (2023). Vast majority of voters still think first nations Australians should have a voice. Australian National University. Available online: https://reporter.anu.edu.au/all-stories/vast-majority-of-voters-still-think-first-nations-australians-should-have-a-voice (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Broockman, D., & Kalla, J. (2022). The impacts of selective partisan media exposure: A field experiment with Fox News viewers. OSF Preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J., & Finklea, B. W. (2022). Fundamentals of media effects: Third edition. Waveland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. (2023a, September 12). Marcia Langton denies criticising no voters, and says media is targeting her. The Guardian. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. (2023b, September 13). Marcia Langton to seek legal advice over Dutton post quoting ‘absolutely not true’ voice headline. The Guardian. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J., & Allam, L. (2023, September 14). ‘A betrayal’: Burney condemns Price claim colonisation had no ongoing negative impacts. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/sep/14/jacinta-nampijinpa-price-says-colonisation-had-no-negative-impacts-on-indigenous-australians (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Christians, C. G., Glasser, T. L., McQuail, D., Nordenstreng, K., & White, R. A. (2009). Normative theories of the media: Journalism in democratic societies. University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, B. (1963). The press and foreign policy. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crabb, A. (2023, September 14). The attacks on Marcia Langton are not part of a theoretical debate. We know that racism exists. ABC. [Google Scholar]

- Credlin, P. (2023, September 15). Credlin in ‘national hero’: Peta Credlin praises Jacinta Price’s ‘moral courage’. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=odfyIXrIlLc (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Cushion, S., Kilby, A., Thomas, R., Morani, M., & Sambrook, R. (2018). Newspapers, impartiality and television news: Intermedia agenda-setting during the 2015 UK general election campaign. Journalism Studies, 19(2), 162–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, D., Downey, J., Harmer, E., Stanyer, J., & Wring, D. (2016). The narrow agenda: How the news media covered the Referendum. EU Referendum Analysis, 2016, 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dearing, J. W., & Rogers, E. (1996). Agenda-setting. Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, A. R. (2022). Conspiracy theories and the manufacture of dissent: QAnon, the ‘Big Lie’, COVID-19, and the rise of rightwing propaganda. Critical Sociology, 48(6), 1025–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, G., & Wood, B. (1999). Who influences whom? The President, congress, and the media. The American Political Science Review, 93(2), 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmelund-Praestekaer, C., & Wien, C. (2008). What’s the fuss about? The interplay of mediahypes and politics. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 13(3), 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R. M. (2007). Framing bias: Media in the distribution of power. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R. M., Matthes, J., & Pellicano, L. (2009). Nature, sources and effects of news framing. In K. Wahl-Jorgensen, & T. Hanitzsch (Eds.), The handbook of journalism studies (pp. 175–190). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Eshbaugh-Soha, M., & Peake, J. (2005). Presidents and the economic agenda. Political Research Quarterly, 58(1), 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evershed, N., & Nicholas, J. (2023, October 13). Voice referendum 2023 poll tracker: Latest results of opinion polling on support for yes and no campaign. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/ng-interactive/2023/oct/13/indigenous-voice-to-parliament-referendum-2023-poll-results-polling-latest-opinion-polls-yes-no-campaign-newspoll-essential-yougov-news-by-state-australia (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Faris, R., Roberts, H., Etling, B., Bourassa, N., Zuckerman, E., & Benkler, Y. (2017). Partisanship, propaganda, and disinformation: Online media and the 2016 US presidential election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Available online: https://dash.harvard.edu/entities/publication/73120379-47f2-6bd4-e053-0100007fdf3b (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Fielding, V. (2023). Conservative advocacy journalism: Explored with a model of journalists’ influence on democracy. Journalism, 24(8), 1817–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, V. (2025). Evaluating reporting roles in climate disasters. In S. Cottle (Ed.), Communicating a world-in-crisis (1st ed., Vol. 31, pp. 43–63). Peter Lang Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding, V., Boucaut, R., Son, C., & Beare, A. H. (2025a). News media’s legitimisation of disinformation: Propaganda and the length of the Uluru Statement. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 42(1), 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, V., Son, C., Boucaut, R., & Beare, A. H. (2025b). News corp australia’s conservative advocacy against the indigenous voice to parliament. International Journal of Communication, 19(21), 437–457. [Google Scholar]

- Gaber, I. (2024). Brexit and murdoch—A marriage made in hell. In The routledge companion to business journalism (pp. 399–408). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gaber, I., & Tiffen, R. (2018). Politics and the media in Australia and the United Kingdom: Parallels and contrasts. Media International Australia, 167(1), 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, N. T. (2018). Media definitely do matter: Brexit, immigration, climate change and beyond. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 20(4), 827–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilardi, F., Gessler, T., Kubli, M., & Müller, S. (2022). Social media and political agenda setting. Political Communication, 39(1), 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoewe, J., Brownell, K. C., & Wiemer, E. C. (2020). The role and impact of Fox News. The Forum, 18, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J., & Lewis, R. (2023, September 12). ‘Base racism’: Indigenous voice to parliament Yes leader Marcia Langton in no-holds-barred call. The Australian. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, X., Tarasevich, S., Proverbs, P., Myslik, B., & Kiousis, S. (2020). President Trump vs. CEOs: A comparison of presidential and corporate agenda building. Journal of Public Relations Research, 32(1–2), 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, A. I., & Gruber, J. B. (2021). Political agenda setting in the hybrid media system: Why legacy media still matter a great deal. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 26(2), 313–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levendusky, M. (2013). Partisan media exposure and attitudes toward the opposition. Political Communication, 30(4), 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levendusky, M. (2024). How partisan media polarize America. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maley, J. (2023, September 17). Pity the subject of a pile-on. The Age. [Google Scholar]

- Manne, R. (2011). Bad news: Murdoch’s Australian and the shaping of the nation. Quarterly Essay, (43), 1–119. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, G. J., & Yurukoglu, A. (2017). Bias in cable news: Persuasion and polarization. American Economic Review, 107(9), 2565–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusitz, J., & Breen, G.-M. (2012). An examination of pack journalism as a form of groupthink: A theoretical and qualitative analysis. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 22(7), 896–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D. (2003). “A world hungry for a new philosophy”: Rupert Murdoch and the rise of neo-liberalism. Journalism Studies, 4(3), 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D. (2013). Murdoch’s politics: How one man’s thirst for wealth and power shapes our world. Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K. (2023, September 16). Some Australians seem more outraged by accusations of racism than by racism itself. Guardian Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, E., Goel, S., & Iyengar, S. (2021). Partisan selective exposure in online news consumption: Evidence from the 2016 presidential campaign. Political Science Research and Methods, 9(2), 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A. (2019). The british right-wing mainstream and the European referendum. In A. Nadler, & A. J. Bauer (Eds.), News on the right: Studying conservative news cultures (pp. 141–156). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, G. (2023, September 14). Sussan Ley says Liberals not running No campaign as mass distribution of text messages questioned. ABC. [Google Scholar]

- Scheufele, D. A., & Tewksbury, D. (2007). Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of Communication, 57, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweickart, T., Neil, J., Kim, J. Y., & Kiousis, S. (2016). Time-lag analysis of the agenda-building process between White House public relations and congressional policymaking activity. Journal of Communication Management (London, England), 20(4), 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevenans, J. (2017). The media’s informational function in political agenda-setting processes. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 22(2), 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, P., & Reese, S. (1996). Mediating the message: Theories of influences on mass media content (2nd ed.). Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Starbird, K., DiResta, R., & DeButts, M. (2023). Influence and improvisation: Participatory disinformation during the 2020 US election. Social Media+ Society, 9(2), 20563051231177943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y., & Borah, P. (2019). Who is the agenda setter? Examining the intermedia agenda-setting effect between Twitter and newspapers. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 16(3), 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y., & Weaver, D. (2007). Agenda-setting effects among the media, the public, and Congress, 1946–2004. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 84(4), 729–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aelst, P., & Walgrave, S. (2011). Minimal or massive? The political agenda-setting power of the mass media according to different methods. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 16(3), 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Pas, D. (2014). Making hay while the sun shines: Do parties only respond to media attention when the framing is right. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 19(1), 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gorp, B. (2010). Strategies to take subjectivity out of framing analysis. In P. D’Angelo, J. A. Kuypers, & I. Ebrary (Eds.), Doing news framing analysis empirical and theoretical perspectives (pp. 84–109). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vesa, J., Bloomberg, H., & Kroll, C. (2015). Minimal and massive! Politicians’ views on the media’s political agenda-setting power revisited. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 20(3), 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vliegenthart, R., Walgrave, S., Baumgartner, F., Bevan, S., Breunig, C., Brouard, S., Chaques Bonafont, L., Grossoman, E., Jennings, W., Mortensen, P., Palau, A., Sciarini, P., & Tresch, A. (2016). Do the media set the parliamentary agenda? A comparative study in seven countries. European Journal of Political Research, 55(2), 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonbun, R., Konigslow, K., & Schoenbach, K. (2015). Intermedia agenda setting in a multimedia news environment. Journalism Theory, Practice, and Criticism, 17(8), 1054–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walgrave, S., Boydstun, A. E., Vliegenthart, R., & Hardy, A. (2017). The nonlinear effect of information on political attention: Media storms and U.S. congressional hearings. Political Communication, 34(4), 548–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, M., Jones, B. D., & Baumgartner, F. R. (2013). A failure to communicate: Agenda setting in media and policy studies. Political Communication, 30(2), 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. (2025). Weapons of mass deception: How right-wing media wage information warfare and undermine american democracy. Oxford University Press, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y., & Bennett, L. (2022). Interactive propaganda. In P. Van Aelst, & J. G. Blumler (Eds.), Political communication in the time of coronavirus (pp. 83–100). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.