Abstract

There has been a decline in the age at which girls experience menarche worldwide. Research suggests that exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals is linked to negative health consequences, including early onset of menarche. This systematic review examined the association between exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and the early onset of menarche. Comprehensive searches of the PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus databases were conducted to find relevant studies published from inception to November 2024. Exposure to certain EDCs, such as particulate matter and phthalates, showed significant associations with earlier menarche onset, while exposure to other EDCs (e.g., pyrethroids) was linked to delayed menarche timing. Overall, there were mixed findings in the relationships between various EDC exposures and menarche onset. Few studies investigated how exposure to EDCs and early menarche differed by race and ethnicity. This underscores the need for more studies that examine the relationship between early menarche onset and exposure to endocrine-disrupting substances. Education and policy approaches are also warranted to address this issue.

1. Introduction

Globally, the age at which girls experience menarche (first menstrual period) has declined substantially over the past two centuries [1,2,3]. In developed nations, the average age of menarche has dropped from around 17 years in the mid-1800s to approximately 12 years today [1,2,3]. Similar downward trends have been reported in parts of Asia and Africa, suggesting that this phenomenon transcends geographical, socioeconomic, and ethnic boundaries [4,5,6]. Early menarche, typically defined as occurring before the age of 12, has emerged as a growing public health concern due to its associations with adverse health outcomes such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, uterine fibroids and breast cancer [7,8,9,10].

The reasons for this secular decline in age of menarche are multifactorial, reflecting complex interactions among genetic, nutritional, psychosocial, and environmental influences. Recent evidence highlights that disparities in exposures to environmental and social determinants—particularly endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), chronic stress, and obesity—may contribute to earlier pubertal timing [11]. Moreover, neighborhood racial and economic deprivation can shape both the degree of exposure to EDCs and biological susceptibility to their effects, emphasizing the intersection between environmental risk and social inequity [11,12].

According to the Endocrine Society [13], EDCs are exogenous substances or mixtures that interfere with hormonal activity, potentially leading to adverse health effects. This diverse group includes industrial compounds such as flame retardants (e.g., polychlorinated and polybrominated biphenyls and dioxins), plasticizers like phthalates and bisphenol A (BPA), persistent pesticides such as dichlorodiphenyldichloro-roethylene (DDE), and pharmaceuticals including diethylstilbestrol (DES). Because these compounds can mimic, block, or alter the action of endogenous hormones, they can disrupt normal endocrine signaling during critical developmental windows. Given their widespread presence in food, water, air, and consumer products, human exposure to EDCs is nearly ubiquitous [13].

Accumulating epidemiologic evidence suggests exposure to EDCs may be associated with early onset of menarche [14]. This link is biologically plausible, as many EDCs act as estrogen mimetics, potentially triggering premature activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis [15,16]. Nonetheless, the strength and consistency of the evidence remain uncertain. Differences in study design, exposure assessment, outcome measurement, and population characteristics have contributed to mixed findings across studies [17,18,19]. Furthermore, most research has focused on North American and European populations, with limited data from low- and middle-income countries, where patterns of exposure and vulnerability may differ [20,21,22].

Given these gaps, a comprehensive synthesis of existing evidence is needed to clarify the relationship between exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and early menarche. Therefore, the present systematic review aims to evaluate and summarize the available literature on this association. This review seeks to advance understanding of how environmental exposures contribute to early pubertal onset and to inform future research and public health strategies aimed at reducing exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

The study protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews Protocols (PROSPERO, identification number CRD42025635630). This systematic review was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [23].

2.2. Search Strategy

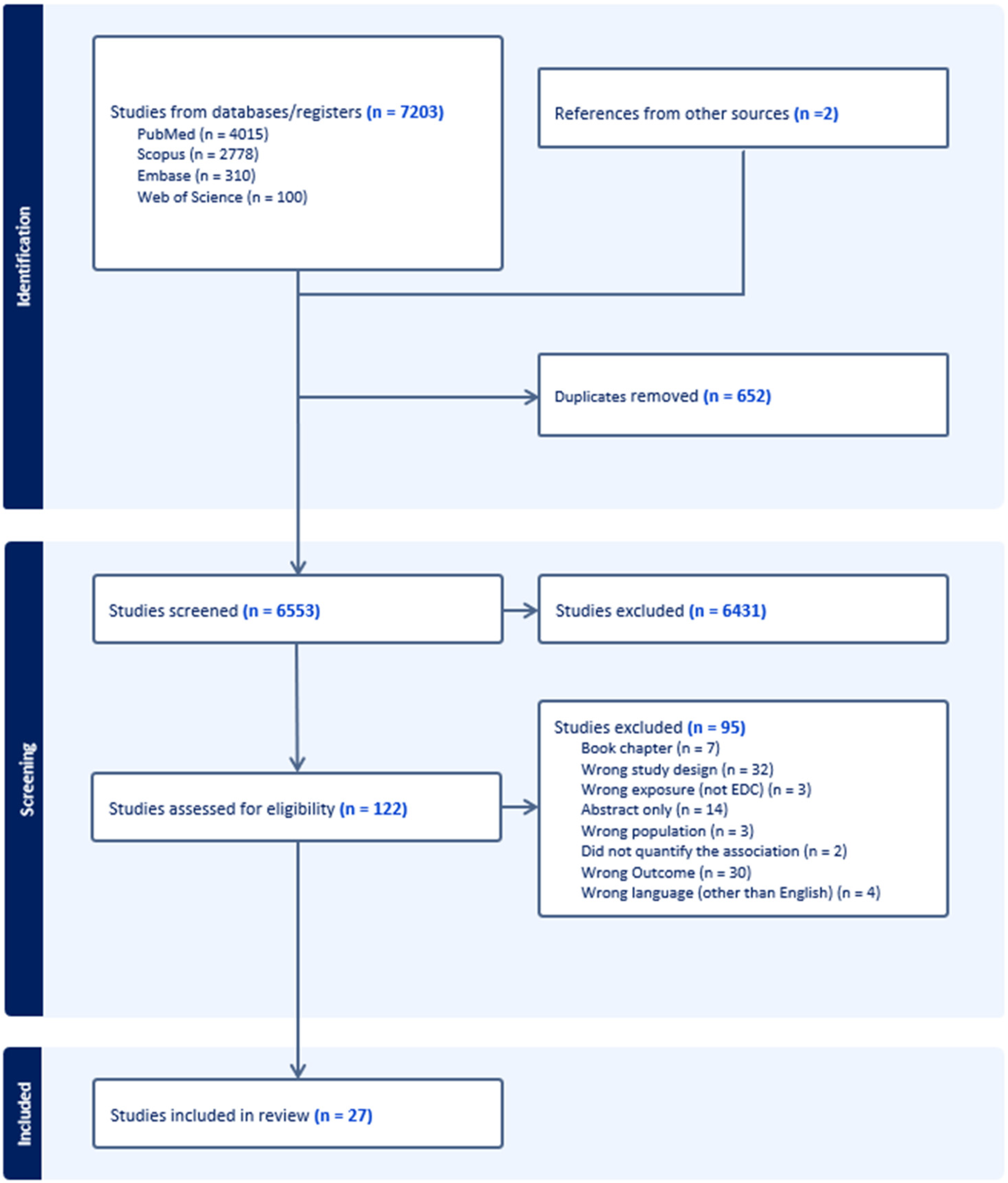

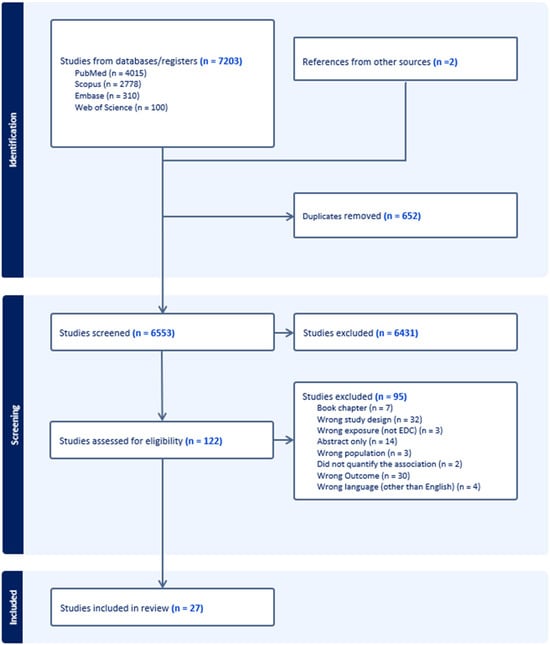

The search was performed in MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase (Ovid), Web of Science, and Scopus databases from inception to November 2024. In PubMed, the following search strategy was used: (“endocrine disrupting chemicals” OR “bisphenol A” OR phthalates OR “polybrominated biphenyls” OR chlorpyrifos OR dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane OR methoxychlor OR diethylstilbestrol OR phytoestrogens OR plasticizers OR solvents OR lubricants OR fungicides OR “flame retardant additives” OR “hair straightener” OR “cosmetic makeup” OR “Endocrine Disruptors” [Mesh] OR “Disorders of Sex Development” [Mesh] OR “Hormones, Hormone Substitutes, and Hormone Antagonists” [Mesh]) AND (“early menarche” OR “premature menarche” OR “precocious puberty” OR “early puberty” OR “pubertal development stage” OR “puberty, precocious” [MeSH Terms]). A similar strategy was used for Embase and Web of Science. A manual search was also performed. References and screening were managed using Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia). Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow chart that illustrates the research selection procedure.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

This review included peer-reviewed studies written in English that quantified the association between endocrine-disrupting chemicals and early onset of menarche in females. Studies conducted in males only, non-human subjects, reviews, commentaries, expert opinions, books, and articles without full text were excluded.

2.4. Early Menarche

Early menarche was defined as the onset of menstruation before the age of 12 years [24,25,26].

2.5. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals include those found in plasticizers such as BPA and phthalates, solvents and lubricants (polybrominated biphenyls (PBBs), polychloro-rinated biphenyls (PCBs), and dioxins), pesticides (chlorpyri-fos and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, or DDT), fungicides (vinclozolin), and flame retardants such as diethylstilbestrol (DES), a non-steroidal synthetic estrogen. EDCs can also be found naturally. For example, phytoestrogens, which are made by plants and mainly act through estrogen receptors, disrupt endogenous endocrine function [27,28,29,30].

2.6. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two reviewers assessed each article starting from the title and abstract; afterwards they completed the full text review. A third reviewer resolved any disagreements. Data was then extracted from the studies that fit the inclusion criteria. As the included studies were heterogeneous, a narrative synthesis was used to summarize the findings.

3. Results

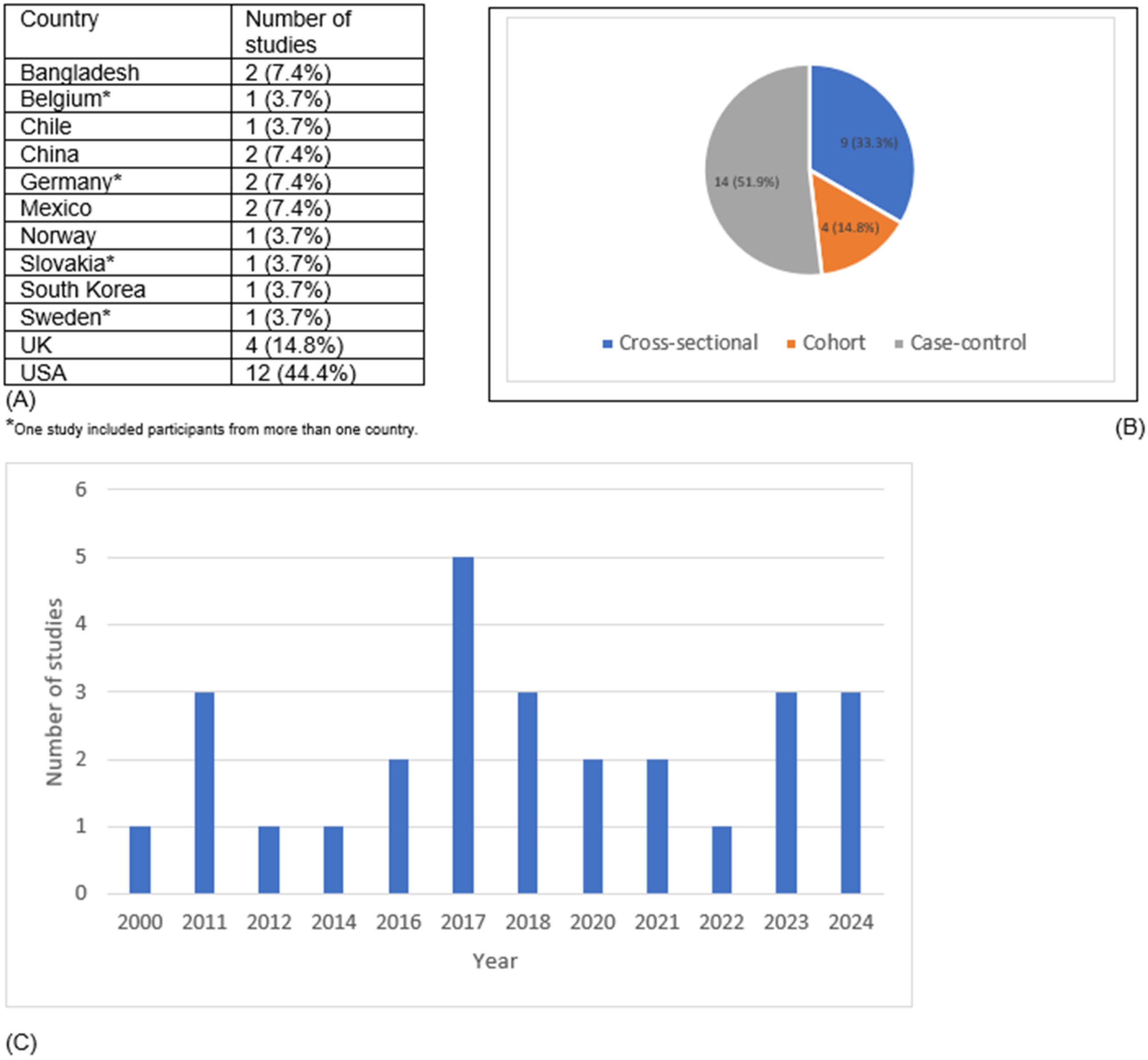

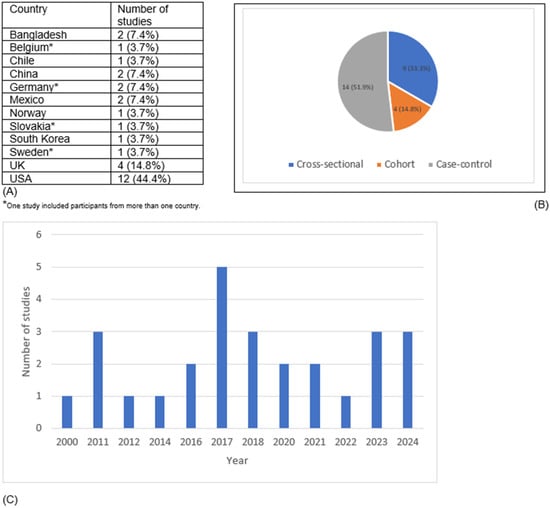

Our search yielded 27 eligible studies for data extraction (Figure 1). The U.S. accounted for 12 studies, while the U.K. contributed 4 studies, making them the primary locations of research (Figure 2). Although no time restriction was placed on the search, the studies included were published from the year 2000 onward. Fourteen studies were cross-sectional in design (providing a snapshot of EDC and early menarche at a single point in time), 9 were case–control studies (comparing participants with and without early menarche based on past exposure to EDC) and 4 were cohort studies (following participants over time to assess EDC–early menarche relationships). The characteristics and main findings of the included studies are summarized in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

Figure 2.

Distribution of included studies by (A) country, (B) study design, and (C) year of publication.

3.1. Toxic Metals (Lead, Cadmium, Mercury) and Minerals (Fluoride)

One study [31] found a link between elevated blood lead and mercury levels and an earlier onset of menarche in Korean girls. Specifically, the blood concentrations of these heavy metals in their study were higher in Korean girls compared to those reported in other developed countries. For instance, the average blood lead level in girls aged 10–18 years was 1.15 μg/dL, significantly higher than the 0.57 μg/dL reported in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Additionally, children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and poorer living conditions had notably higher blood heavy metal levels compared to those from higher socioeconomic backgrounds and enhanced living conditions [31].

In contrast, a study in Bangladesh found no correlation between childhood cadmium or lead exposure and earlier menarche. In fact, cadmium exposure was associated with a later onset of menarche, while the link to lead exposure remained unclear. The study also explored maternal exposure to environmental chemicals, revealing that maternal arsenic exposure was linked to delayed menarche, but no similar association was observed for cadmium or lead [32].

In the United States, a study [33] reported mixed results regarding fluoride exposure and the timing of menarche among adolescent girls. While there was no significant relationship between fluoride exposure and menstrual cycle regularity, higher concentrations of fluoride in drinking water were associated with earlier menarche. Specifically, a 0.53 mg/L increase in household tap water fluoride led to menarche occurring 3.3 months earlier. When the study looked at racial/ethnic differences, higher plasma fluoride concentrations were found to correspond with earlier menarche, but this effect was seen only in non-Hispanic Black adolescents. A 0.3 µmol/L rise in plasma fluoride was linked to menarche occurring five months earlier in this group [33].

Furthermore, Malin Igra et al. [32] observed that, at the same age, girls with higher urinary cadmium levels at 5 and 10 years old experienced a later onset of menarche compared to those with lower cadmium levels. Specifically, girls in the highest cadmium quartile at age 5 had a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.62, 1.01), and those at age 10 had an HR of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.60, 0.98), indicating a delayed menarche. In contrast, girls with higher urinary lead levels at age 10 experienced an earlier onset of menarche, with an HR of 1.23 (95% CI: 0.97, 1.56). However, no such relationship was found for urinary lead at age 5. Additionally, girls born to mothers with higher levels of erythrocyte arsenic during pregnancy were less likely to have reached menarche than those born to mothers in the lowest arsenic quartile [32].

3.2. Personal Care Products and Plasticizing Chemicals (PCPPCs)

Regarding personal care products and plasticizing chemicals (PCPPCs), Harley et al. [34] demonstrated that prenatal exposure to triclosan and 2,4-dichlorophenol accelerated menarche timing in girls, while prenatal monoethyl phthalate (MEP) was associated with earlier pubarche [34]. This aligns with Bigambo et al.’s [35] finding that 2,4-DCP was positively associated with early menarche onset. Todd et al. [36] further supported these associations, revealing that childhood hair oil use increased the likelihood of earlier menarche by 1.4 times (95% CI: 1.1–1.7). Additionally, Harley et al. [34] found that peripubertal methyl paraben concentrations were linked to earlier thelarche, pubarche, and menarche in girls, suggesting both prenatal and childhood exposures may influence pubertal timing.

Despite some positive findings, research also reveals numerous chemicals with no clear association to menarche timing. James-Todd et al. [36] determined that while hair oils showed associations with early menarche, other commonly used products, including hair lotion, leave-in conditioner, and various other hair products, demonstrated no significant association with menarche timing. Bigambo et al. [35] found mixed results regarding Sex Hormone Binding Gene (SHBG) associations, with some chemicals (BPA, PrP, MCOP, MBzP) showing positive associations while others (BZP, MCNP, MECPP, MEHHP, MiBP) demonstrated negative associations, indicating complex and potentially contradictory biological mechanisms. Additionally, McDonald et al. [37] found that earlier age at menarche was linked to hair product use during childhood, especially among African American girls.

3.3. Bisphenol A (BPA)

Kasper-Sonnenberg et al. [38] identified a link between pre-pubertal exposure to phthalates and BPA and pubertal timing in children, particularly in girls. Research findings indicated that exposure to DiNP metabolites was positively associated with the onset of menarche (ORs 1.08–1.14). Breast development and menarche were the most impacted by metabolite concentrations. However, phthalate metabolite and BPA levels were negatively associated with pubertal development, except for DiDP and DiNP metabolites. Watkins et al. [39] found that specific stages of reproductive development may be particularly susceptible to phthalate or BPA exposure. The study identified an association between phthalate exposure during the third trimester of pregnancy and changes in reproductive hormone levels and pubertal onset among the participating girls.

3.4. Plant-Derived/Organic/Naturally Occurring EDCs (e.g., Phytoestrogen)

Research by Marks et al. [40] indicated no association between prenatal phytoestrogen exposure and early menarche onset. Their findings revealed a complex relationship, where increased in utero enterodiol exposure was linked with decreased odds of early menarche in the second and third trimesters of expectant mothers. Higher in utero enterodiol concentrations, comparing the highest to the lowest exposure tertiles, were inversely associated with the likelihood of early menarche (OR = 0.47, 97%CI = 0.29–0.83), while higher desmethylangolensin (O-DMA) levels were associated with early menarche (OR = 1.89, 95% CI = 1.04–3.42) [40].

3.5. Phenols

Binder et al. [41] looked at the association between phenol and phthalate exposure during childhood and menarche. Their research showed that higher levels of B12,5-dichlorophenol were associated with earlier menarche. The strength of the relationship between childhood exposure to phenols and phthalates and the onset of menarche depended on the timing of biomarker measurements, highlighting critical windows of heightened vulnerability during hormone-driven developmental stages [41]. Wolff et al. [42] reported associations for three urinary biomarkers (2,5-dichlorophenol, enterolactone, MCPP). When comparing girls in the 5th versus 1st quintiles of biomarker concentrations, the analysis showed that adjusted median ages at menarche were 7 months earlier for 2,5-dichlorophenol, 4 months later for enterolactone, and 5 months later for MCPP [42].

In their study, Buttke et al. [18] revealed an inverse association between 2,5-dichlorophenol (2,5-DCP) and summed environmental phenols (2,5-DCP and 2,4-DCP) with the age of menarche. However, there were no significant associations between other exposures (total parabens, bisphenol A, triclosan, benzophenone-3, total phthalates, and 2,4-DCP) and age of menarche. Considering the total environmental phenol concentration, they found that for adolescent girls above the 75th percentile, the mean age of menarche was lower at 11.8 years (95% CI: 11.6, 12.0). In contrast, the mean age of menarche for adolescent girls below the 25th percentile of total environmental phenol urine concentration was higher at 12.4 years (95% CI: 12.2, 12.6) [18].

3.6. Polybrominated Biphenyls (PBBs), Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs)

Evidence from Blanck et al.’s [43] study indicates that postnatal exposure to PBBs via breastfeeding is associated with accelerated timing of menarche. They found that menarche occurred nearly 1 year earlier in PBB-exposed breastfed girls (11.6 years) than in unexposed girls (12.2–12.7 years), suggesting that combined prenatal and lactational exposure accelerates puberty. The study also observed an association between PBB exposure and earlier pubic hair development but not breast development, indicating that organic halogens may disrupt normal pubertal development when exposure occurs during both fetal and early postnatal periods [44].

However, the analysis revealed no statistically significant relationship between maternal PCB levels and either menarche timing or pubertal development as measured by Tanner staging. Similarly, Marks et al. [44] explored the impact of fetal exposure to mixtures of long-lasting endocrine disruptors, including PCBs, in a large cohort and found no association with early menarche onset (<11.5 years). They used advanced statistical models to conclude that exposure to PCB mixtures did not significantly impact pubertal timing, reinforcing the lack of convincing evidence linking PCB exposure to early onset of menarche [44].

3.7. Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether (PBDE)

The study by Harley et al. [45] focused on polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), a class of flame retardants with known endocrine-disrupting properties, on pubertal timing in a predominantly Latina population in Northern California. No significant links were found between in utero PBDE contamination and indicators of female pubertal development (breast or pubic hair stages). While most childhood PBDE exposures showed no effect, BDE-153 demonstrated a specific association with later menarche onset [45]. However, Chen et al. [46] reported that PBDEs were associated with slightly earlier ages at menarche.

Table 1.

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs, PFAS, PCBs, PBBs, PBDEs, OCPs, etc.).

Table 1.

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs, PFAS, PCBs, PBBs, PBDEs, OCPs, etc.).

| References | Year of Publication | Study Design | Country | Study Participants | Sample Size | Exposure | Outcome Definition | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blanck et al. [43] | 2000 | Retrospective cohort | United States | Female offspring at least 5 years of age as of 1997, born during or after the Michigan PBB incident | n = 327 | Polybrominated diphenyl (PBB) | self-reported age at menarche | Girls who were breastfed and exposed to high levels of PBBs before birth started their periods earlier (around age 11.6) compared to breastfed girls with lower exposure (12.2–12.7 years) and girls who were not breastfed (12.7 years). |

| Marks et al. [44] | 2021 | Case–control | United Kingdom | pregnant women with an expected delivery date between 1 April 1991 and 31 December 1992, from three health districts in the former county of Avon, Great Britain. Mother and daughter | n = 448 | EDCs (poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and organochlorine pesticides (OCPs)) | age at menarche | There is no significant association between prenatal exposure to certain endocrine-disrupting chemicals (PFAS, PCBs, and OCPs) and early menarche (<11.5 years). |

| Harley et al. [45] | 2017 | Cohort | United States | Mothers during pregnancy (n = 263) and their children at age 9 years (n = 522). Mexican-origin families | n = 522, 314 girls | Polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE) | timing of menarche by self-report | Childhood PBDE exposure was not associated with any measure of pubertal timing, except for an association of BDE-153 with later menarche. |

| Chen et al. [46] | 2011 | Cross-sectional | United States | NHANES 2003–2004 | n = 271 | blood Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) | age at menarche | Higher serum PBDEs were associated with slightly earlier ages at menarche in multivariable model. Each natural log unit of total BDEs was related to a change of −0.10 (95% CI: −0.33, 0.13) years of age at menarche and a RR of 1.60 (95% CI: 1.12, 2.28) for experiencing menarche before 12 years of age |

| Averina et al. [47] | 2024 | Cross-sectional | Norway | First year high school students aged 12–19 years | n = 1038 | persistent organic pollutants (polyfluroalkyl substances PSA) | self-reported age at menarche | Some PFAS had a positive association to earlier menarche, specifically PFDA and PFUnDA. |

| Christensen et al. [48] | 2011 | Case–control | United Kingdom | female offsprings in the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children (ALSPAC) | n = 448 | polyfluroakyl chemicals (PFCs) during pregnancy | age at menarche | All study participants had nearly ubiquitous exposure to most PFCs examined, but PFC exposure did not appear to be associated with altered age of menarche of their offspring |

| Pinney et al. [49] | 2023 | Cohort | United States | Girls were recruited at 6–8 years of age in 2004–2007 from (a) Mount Sinai School of Medicine, (b) Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and (c) Cincinnati Children’s Hospital/University of Cincinnati | n = 379 | PFAS | thelarche, pubarche, and menarche | PFAS may delay pubertal onset through the intervening effects on BMI and reproductive hormones. The decreases in DHEAS and E1 associated with PFOA represent biological biomarkers of effect consistent with the delay in onset of puberty. |

3.8. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

Due to their long-lasting nature in the environment, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) may disrupt endocrine function due to their biological activity. However, their relationship with early menarche remains inconclusive. While some studies, such as Averina et al. [47], identified positive correlations between PFDA and PFUnDA exposure and earlier onset of menarche in Norwegian adolescents, others, including Mark’s and Christensen’s groups, did not observe any meaningful relationships [44,48]. Additionally, some studies have reported that exposure to PFOS and PFOA may be associated with delayed menarche [49].

Recent findings by Cox et al. [50] analyzing four European cohorts (ages 12–18) showed that while phthalates like MEHP and 5OH-MEHP were significantly linked to earlier menarche, PFAS compounds, such as PFOA and PFHxS exhibited a weak trend toward delaying menarche without statistical significance.

Table 2.

Plasticizers (Phenols, Phthalates, BPA, PCPPCs).

Table 2.

Plasticizers (Phenols, Phthalates, BPA, PCPPCs).

| References | Year of Publication | Study Design | Country | Study Participants | Sample Size | Exposure | Outcome Definition | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cox et al. [50] | 2023 | Cross-sectional | Sweden, Slovakia, Germany and Belgium | female participants aged 12–18 years in the Human Biomonitoring for Europe initiative(HBM4EU) | n = 514 | Polyfluoakyl (PFA) and phthalates | age at menarche | Urinary DEHP concentrations, particularly 5OH-MEHP is associated with an earlier age of menarche in 12–18-year-old teenage participants. |

| Binder et al. [41] | 2018 | Cohort | Chile | random subset of the longitudinal Growth and Obesity Cohort study | n = 200 | Endocrine-disruptive chemicals (EDCs) phenols and Phthalates | self-reported age at menarche | Higher B1 concentrations of 2,5-dichlorophenol and benzophenone-3 were associated with earlier menarche. Elevated B4 concentrations of monomethyl phthalate were similarly associated with earlier menarche. |

| Cathey et al. [51] | 2020 | Cohort | Mexico | Subset of adolescent children aged 8–14 years from mothers with early life exposure in Mexico to environmental toxicants (ELEMENT) project. | n = 554 | Gestational exposure to Phthalate | tanner staging+ menarche onset | Gestational phthalates exposure is associated with earlier onset and slower progression of sexual maturation outcomes in girls, particularly breast development. |

| Buttke et al. [18] | 2012 | Cross-sectional | United States | NHANES 2003–2008 | n = 1598 | Endocrine-disruptive chemicals (EDCs) phthalates, parabens and phenols | age at menarche | Girls with urinary environmental phenol concentrations above the 75th percentile had significantly lower age of menarche than girls below the 75th percentile. No other significant association was seen between urinary EDC biomarkers and age of menarche. |

| Harley et al. [45] | 2018 | Cohort | United States | Pregnant women recruited in 1999–2000 from community clinics serving California’s Salinas Valley. Eligibility criteria included being at least 18 years of age, <20 weeks gestation, English-or Spanish-speaking, and qualifying for low-income health insurance | n = 338 | Phthalates and parabens found in personal care and consumer products | tanner stage + age at menarche | All biomarkers were detected in more than 90% of samples, except triclosan (73% in prenatal and 69% in peripubertal samples) and butylparaben (detected in less than 40% of samples and therefore excluded from analyses). |

| Watkins et al. [39] | 2017 | Cohort | Mexico | Pregnant women in Mexico City and their children. Our analysis includes women who were recruited from maternity hospitals during their first trimester between 1997 and 2004 and their children | n = 120 | Phthalate and bisphenol A | tanner stage + menarche status | Mean mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate in the third trimester was associated with higher odds of having a Tanner Stage > 1 for pubic hair development. |

| Wolff et al. [42] | 2016 | Cohort | United States | Black or Hispanic girls mainly from East Harlem in New York City; Cincinnati Children’s Hospital (Cincinnati) that recruited from the greater Cincinnati metropolitan area; and Kaiser Permanente Northern California (California) that recruited members of the KPNC Health Plan in the San Francisco Bay Area. | n = 1051 | Phenols and phthalates | age at menarche | Environmental biomarkers measured ten years before puberty were found to be associated with timing of both breast development and menarche; two others were associated with breast development but not menarche. Six other biomarkers or composite indices were associated with neither. |

| McGuinn et al. [52] | 2014 | Cross-sectional | United States | NHANES 2003–2010 | n = 987 | Urinary bisphenol A (BPA) | age at menarche | No association between BPA and age at menarche in multivariable model including race. |

| Bigambo et al. [35] | 2022 | Cross-sectional | United States | NHANES 2013–2016 females aged 12–19 years | n = 297 | personal care products and plasticizing chemicals (PCPPCs) Phenols, Parabens and phthalates | self-reported age at menarche | The mixture of PCPPCs was significantly associated with reproductive hormones particularly TT and SHBG and early menarche in girls 12–19 years. |

| Kasper-Sonnenberg et al. [38] | 2017 | Cohort | Germany | Eight- to ten-year-old children from the German Duisburg Birth and Bochum Cohort studies | n = 408, girls = 198 | Bisphenol A and phthalates | tanner staging+ menarche onset | Girls started puberty earlier than boys. Breast development and the onset of menstruation were more strongly influenced by metabolite levels than pubic hair growth. BPA showed no consistent association with the individual PFD scales. |

3.9. Phthalates

Phthalates are known to have endocrine-disruptive effects on humans; however additional evidence is needed to establish the extent of this effect [51]. Binder et al. [41] explored the impact of childhood contamination to phthalates on the age of menarche in Latina girls, revealing that several biomarkers were significantly linked to menarche timing. Specifically, a log (ng/mL) rise in B1 di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate biomarker levels was associated with delayed menarche, with a hazard ratio of 0.77 and a 95% confidence interval of 0.60 to 0.98. Conversely, increased B1 concentrations of 2,5-dichlorophenol and benzophenone-3 were linked to earlier menarche, showing hazard ratios of 1.13 (95% CI: 1.01–1.27) and 1.17 (95% CI: 1.06–1.29), respectively. Higher B4 levels of monomethyl phthalate were also associated with earlier menarche (HR: 1.30; 95% CI: 1.10–1.53) [41]. Cathey et al. [51] found that gestational phthalate exposure in Mexico City was associated with a twofold increase in the likelihood of reaching a higher Tanner stage or menarche, as well as a doubling in the pace of sexual maturation. With a twofold increase in gestational monobenzyl phthalate (MBzP) levels, the odds of attaining menarche were marginally elevated (OR: 3.86; 95% CI: 0.96–15.5), while the rate of progression to menarche was reduced (OR: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.47–1.02).

A study from Mexico [51] also concluded that first-trimester MEP levels were associated with elevated odds of menarche (OR/IQR: 3.9; 95% CI: 1.1–14.2), whereas BPA exposure in the second trimester corresponded to higher odds of reaching Tanner Stage >1 in breast development (OR/IQR: 2.2; 95% CI: 1.0–4.5). Cox et al. [50], in a study conducted in Europe, found that phthalate exposure in the environment contributed to an earlier onset of menarche. Using single-pollutant multiple linear regression models, elevated concentrations of MEHP, 5OH-MEHP, and 5oxo-MEHP were significantly associated with a lower age at menarche, with estimated decreases of 0.19 (95% CI: 0.05–0.33), 0.28 (95% CI: 0.12–0.43), and 0.18 (95% CI: 0.04–0.31) years per interquartile increase, respectively [52].

However, Buttke et al. [18] found that total parabens, triclosan, BPA, benzophenone-3, and total phthalates were not significantly associated with age of menarche in the study conducted in the U.S. Still, the mean age of menarche was significantly lower among non-Hispanic Black adolescent girls than among non-Hispanic White adolescent girls. Additionally, McGuinn et al. [52] found no association between BPA and age at menarche in a multivariable model including race.

3.10. Other (e.g., PM2.5 (Particulate Matter), Toxic Metals, Parabens, Pyrethroids, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs))

Li et al. [53] reported that in Chinese adolescents, combined exposure to PM2.5 and its components was linked to an earlier onset of menarche. According to Xiong et al. [54], higher levels of PM2.5, sulfate, nitrate, ammonium, and OM exposure were linked to a greater likelihood of early menarche.

A study among Chinese girls by Ye et al. [55] found that pyrethroids, a class of ubiquitous insecticides, delay onset of menarche. For every unit rise in the log-transformed 3-PBA levels, the odds of being in breast stage 3 (B3) were significantly reduced by 45% [OR = 0.55 (95%CI: 0.31–0.98), p = 0.042]. Similar negative correlations were observed between urine 3-PBA levels and pubic hair stage 2 (P2), which was later in onset [OR = 0.56 (95%CI: 0.36–0.90), p = 0.015]. Urinary 3-PBA levels and pubertal onset, as indicated by menarche, also showed a similar negative correlation [OR = 0.51 (95%CI: 0.28–0.93), p = 0.029].

Harley et al. [34] revealed significant associations between peripubertal chemical exposures and pubertal timing in girls. Their analysis demonstrated that each doubling of urinary methyl paraben concentrations was associated with accelerated onset of multiple pubertal milestones: thelarche occurred 1.1 months earlier (95% CI: −2.1, 0.0), pubarche 1.5 months earlier (95% CI: −2.5, −0.4), and menarche 0.9 months earlier (95% CI: −1.6, −0.1). Similarly, a twofold increase in propyl paraben levels at age 9 corresponded with earlier pubarche (−0.8 months; 95% CI: −1.6, −0.1). Conversely, the study reported that elevated peripubertal levels of 2,5-dichlorophenol were linked to a later onset of pubarche (mean shift: +1.0 month; 95% CI: 0.1–1.9), indicating compound-specific influences on pubertal development [31].

Malin Igra et al. [56] investigated the timing of pubertal onset and maternal exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons during pregnancy in a longitudinal mother-child cohort in rural Bangladesh. Findings showed that compared to girls whose mothers were in the lowest quintile, girls whose mothers were in the second and third quintiles of ΣOH-Phe metabolites had a greater menarche rate, indicating a younger menarcheal age (HR 1.39; 95% CI 1.04, 1.86, and HR 1.41; 95% CI 1.05, 1.88, respectively) [57].

Namulanda et al. [58] investigated pregnant mothers in the Bristol area of southwest England, United Kingdom, with daughters due between 1 April 1991, and 31 December 1992. Study results suggested a potential link between prenatal exposure to DACT, a degradate of atrazine metabolites, and earlier menarche. Even though the correlation was weak and the null was included in the confidence intervals, among people with complete data, the link was statistically significant in greater exposure groups (≥median). Although at somewhat lower rates, DACT was the most commonly discovered analyte (58%), which is consistent with previous research [59].

Table 3.

Other EDCs (Fluoride, Heavy metals, PAHs, Hair Products, Atrazine, Phytoestrogens, Air Pollutants, Pesticides).

Table 3.

Other EDCs (Fluoride, Heavy metals, PAHs, Hair Products, Atrazine, Phytoestrogens, Air Pollutants, Pesticides).

| References | Year of Publication | Study Design | Country | Study Participants | Sample Size | Exposure | Outcome Definition | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malin et al. [33] | 2022 | Cross-sectional | United States | Participants from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2013–2016) all female | n = 524 | Fluoride | age at menarche | Higher fluoride in drinking water was linked to earlier puberty. Overall, blood fluoride levels were not tied to age of menarche, but among Non-Hispanic Black girls, higher blood fluoride was linked to earlier puberty, about 5 months earlier for every 0.3 µmol/L increase. |

| Li et al. [53] | 2024 | Cohort | China | Chinese girls 10–17 who had reached menarche 146 participants were classified as early menarche | n = 855 | PM2.5 | menarche timing | Higher exposure to PM2.5, sulfate, nitrate, ammonium, and organic matter was linked to increased odds of early menarche, with sulfate appearing to play the most important role. |

| Ye et al. [55] | 2017 | Cohort | China | A total of 305 girls at the ages of 9–15 years old were recruited in Hangzhou, China in this study. | n = 305 | pyrethroids exposure | tanner staging + onset of menarche | Pyrethroid exposure is unlikely to contribute to the observed secular trend of earlier pubertal timing in girls. |

| Choi et al. [31] | 2020 | Cross-sectional | Korea | Subset female children and adolescents from the sixth Korean national health and Nutrition Examination survey (KNHANES) | n = 179 | Lead, mercury and Cadmium | timing of menarche | Higher blood concentrations of lead and mercury were associated with lower age of menarche. |

| Igra et al. [32] | 2023 | Cohort | Bangladesh | Children born to women in the Maternal and Infant Nutrition Interventions trial in MATLAB R2025a | n = 935 | Exposure to Cadmium, Lead, and Arsenic | age at menarche | Long-term childhood cadmium exposure was associated with later menarche, whereas the associations with child lead exposure were inconclusive. Maternal exposure to arsenic, but not cadmium or lead, was associated with later menarche. |

| Igra et al. [56] | 2024 | Cohort | Bangladesh | Pregnant women who received services from the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research in Bangladesh | n = 582 | Maternal PAH exposure during pregnancy | age at menarche + tanner staging | Girls whose mothers had moderate (second and third quintile) levels of ΣOH-Phe metabolites reached menarche earlier than those with the lowest levels. No link was found for higher quintiles or for other PAH metabolites. |

| James-Todd et al. [36] | 2011 | Cross-sectional | United States | African American, African-Caribbean, Hispanic, and white women | n = 300 | Childhood Hair Product Use | age at menarche | Childhood use of hair oils was associated with earlier recalled age at menarche, independent of year of birth and race/ethnicity. Hair lotions, leave-in conditioners, and other types of products were not associated with an early menarche |

| McDonald et al. [37] | 2018 | Cohort | United States | Women from the New York site of the National Collaborative Perinatal Project, NY-NCPP and women from New York City Multiethnic Breast Cancer Project NYMBCCP | n = 248 | Hair oils, lotions, leave-in conditioners, root stimulators, perms/relaxers, and hair dyes | age at menarche | Childhood use of hair products, especially among African American girls, was linked to earlier menarche. Hair product use in childhood or adulthood showed no strong connection to mammographic density. Non-Hispanic Black women reported higher use than other groups, indicating differences in exposure. |

| Marks et al. [40] | 2017 | Case–control | United Kingdom | Pregnant women with an expected delivery date between 1 April 1991 and 31 December 1992, from three health districts in the former county of Avon, Great Britain. Mother and daughter | n = 370 | Phytoestrogens | age at menarche | Higher levels of enterodiol were linked to later puberty, while enterolactone showed no clear effect. O-DMA, a gut bacteria metabolite of daidzein, was associated with earlier puberty, suggesting gut bacteria may play a role. The study supports the idea that in utero exposure to phytoestrogens could affect pubertal development, as fetal stages are sensitive to endocrine-disrupting compounds. |

| Namulanda et al. [58] | 2016 | Case–control | United Kingdom | Pregnant women living in the Bristol area, in the southwest of England, United Kingdom, with an expected date of delivery from 1 April 1991 to 31 December 1992 and daughters | n = 369 | atrazine analytes | age at menarche | Potential link between in utero exposure to DACT (a degradate of atrazine) and earlier timing of menarche. |

4. Discussion

This review highlights complex and often inconsistent associations between exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and the timing of menarche. Some studies found that toxic metals, namely, lead, mercury, and fluoride, were associated with earlier menarche, whereas arsenic and cadmium were linked to delayed onset. Similarly, phthalates and BPA demonstrated mixed effects, with some exposures advancing and others delaying pubertal development, likely depending on the timing and level of exposure. Personal care products, plasticizers, and phytoestrogens also showed variable associations, with certain chemicals accelerating puberty while others had no effect or delayed development. Prenatal and perinatal exposure to organic halogens such as PBBs, PBDEs, and PCBs presented mixed results, with some studies reporting early menarche and others showing no significant impact. Likewise, PFAS compounds like PFOA and PFOS yielded conflicting findings across populations. Exposure to air pollution, particularly exposure to PM2.5 and its components, showed consistent associations with earlier menarche in studies conducted in China. However, evidence for parabens and other emerging EDCs remains inconclusive. Racial and ethnic disparities were also observed, indicating differential susceptibility or exposure levels, yet remain underexplored in current research.

The findings from this review indicated that exposure to various endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) may affect the onset of menarche; however, the strength and direction of these associations differ according to the specific compound, the developmental period of exposure, and the population studied. These inconsistencies likely reflect differences in study design, exposure measurement, and individual biological susceptibilities, including genetic and racial/ethnic factors.

One possible biological mechanism involves the interaction of EDCs with the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, which regulates pubertal development [57]. Many EDCs, like phthalates, BPA, and PCBs, have estrogenic or anti-estrogenic activity, potentially mimicking or blocking natural hormones and altering the production of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). This disruption can lead to premature or delayed activation of pubertal pathways. Some toxicants, like cadmium and lead, may also interfere with ovarian steroidogenesis or increase oxidative stress, affecting reproductive tissue development [59]. Phytoestrogens, while generally considered weak estrogens, may influence estrogen receptor signaling during sensitive developmental periods, potentially modulating pubertal timing. EDC exposure might bind to sex hormones during puberty, potentially accelerating the maturation process and leading to earlier menarche [52].

The finding that particulate matter and some PFAS compounds are associated with early menarche suggests that systemic inflammation, endocrine disruption, or epigenetic modifications could mediate these effects [60]. Furthermore, timing of exposure (e.g., in utero, early childhood, peripubertal) appears critical, as the developing endocrine system is particularly vulnerable during these periods [56].

The presence of racial and ethnic disparities in the associations, as seen with fluoride and PFAS exposures, points to potential differences in cumulative exposure burdens, socioeconomic factors, or genetic susceptibility, warranting further investigation.

4.1. Recommendations

In light of these findings, future studies should aim to use longitudinal designs to better establish temporality between EDC and early menarche. In addition, the underlying mechanisms, including hormonal, inflammatory, and epigenetic changes, require further investigation. Our study findings also underscore a need for more research to enhance the understanding of racial and ethnic differences in exposure to EDCs and the early onset of menarche. Future studies should include diverse populations to assess disparities.

It is also important to broaden the environmental health lens to include structural and social determinants of women’s health disparities and to frame chemical exposures as a health disparities concern [61,62,63]. While there is limited research on racial and ethnic differences in exposure to EDCs and adverse health outcomes, communities of color disproportionately bear the brunt of exposure to EDCs in the United States [12,64,65].

Legislation aimed at regulating endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDC) and industrial pollutants is essential for minimizing human exposure. Enacting laws to restrict these chemicals could reduce the negative health impacts linked to EDC exposure, emphasizing the considerable influence of environmental toxins on at-risk populations.

4.2. Limitations and Strengths

One of this study’s limitations is that the heterogeneity of the study made it difficult to combine within a meta-analysis. Many studies relied on single-time-point biomarker measurements, which may not accurately capture long-term or cumulative exposures, particularly for chemicals with short biological half-lives. The observational nature of the included studies also limits causal inference due to potential residual confounding, particularly from unmeasured socioeconomic, nutritional, or lifestyle factors. Furthermore, the underrepresentation of racially and ethnically diverse populations in many studies hinders generalizability and limits the ability to explore disparities in exposure and susceptibility. Finally, few studies examined mixtures of EDCs, despite real-world exposures often occurring concurrently.

Despite these limitations, this review offers valuable insights into the crucial role of EDCs and the early onset of menarche. By including various classes of EDCs—such as toxic metals, plasticizers, flame retardants, air pollutants, and personal care product components—this review captures the complexity and breadth of environmental exposures potentially influencing pubertal development. It highlights both consistent and divergent findings, offering nuanced insight into chemical-specific effects and population-specific susceptibilities. The inclusion of studies examining different developmental windows, including prenatal, early childhood, and peripubertal exposures, allows for a more complete understanding of the critical periods during which EDCs may affect reproductive maturation. Importantly, this review also identifies gaps in the literature, such as the limited focus on racial and ethnic disparities and EDC mixtures, providing direction for future research. Overall, the review contributes valuable context to the evolving field of environmental epidemiology and adolescent reproductive health.

5. Conclusions

The current body of evidence indicates that exposure to some endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) may influence the timing of menarche, though findings are often inconsistent and depend on the specific chemical, timing of exposure, and population characteristics. While some EDCs—such as phthalates, PFAS, and air pollutants—appear to accelerate pubertal onset, others, like cadmium and phytoestrogens, may delay it. The mixed results highlight the complex biological pathways involved and the need for more standardized, longitudinal research to clarify causal relationships. With the growing attention to PFAS, future studies should explore its effect on the early onset of menarche. Notably, limited attention has been paid to the role of racial and ethnic disparities and the impact of cumulative or combined exposures. Future studies should prioritize diverse populations, exposure assessment across critical developmental periods, and mechanistic investigations to better understand how EDCs disrupt endocrine function and influence reproductive health. Advancing this knowledge is critical for informing public health policies and interventions aimed at protecting vulnerable populations during sensitive windows of development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.-H. and A.N.; methodology, W.S., A.N., M.A.-H., T.P., K.A. and S.T.;; validation, W.S., A.N. and T.P.; formal analysis, W.S.; investigation, W.S., A.N., M.A.-H., S.T., K.A. and T.P.; resources, W.S., A.N., M.A.-H., T.P., K.A. and S.T.; data curation, W.S., A.N., M.A.-H., S.T., K.A. and T.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.N. and W.S.; writing—review and editing, A.N., W.S., T.P., M.A.-H., K.A. and S.T.; visualization, A.N.; supervision, A.N. and W.S.; project administration, A.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bajpai, A.; Bansal, U.; Rathoria, R.; Rathoria, E.; Singh, V.; Singh, G.K.; Ahuja, R. A Prospective Study of the Age at Menarche in North Indian Girls, Its Association with the Tanner Stage, and the Secular Trend. Cureus 2023, 15, e45383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.T.K.; Fan, H.-Y.; Tsai, M.-C.; Tung, T.-H.; Huynh, Q.T.V.; Huang, S.-Y.; Chen, Y.C. Nutrient Intake through Childhood and Early Menarche Onset in Girls: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert-Lind, C.; Busch, A.S.; Petersen, J.H.; Biro, F.M.; Butler, G.; Bräuner, E.V.; Juul, A. Worldwide Secular Trends in Age at Pubertal Onset Assessed by Breast Development Among Girls: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, e195881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, S.K.; Nishio, M.; Huang, H.-L.; Leung, C.Y.; Islam, R.; Rahman, S.; Saito, E.; Shin, A.; Merritt, M.A.; Choi, J.-Y.; et al. Age at menarche by birth cohort: A pooled analysis of half a million women in Asia. Public Health 2024, 237, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwase, M.; Taniyama, Y.; Koyanagi, Y.N.; Kasugai, Y.; Oze, I.; Masuda, N.; Ito, H.; Matsuo, K. A century of change: Unraveling the impact of socioeconomic/historical milestones on age at menarche and other female reproductive factors in Japan. J. Epidemiol. 2024, 34, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okagbue, H.I.; Samuel, O.W.; Nzeribe, E.C.; Nto, S.E.; Dahunsi, O.E.; Isa, M.B.; Etim, J.; Orya, E.E.; Sampson, S.; Yumashev, A.V. Assessment of the differences in Mean Age at Menarche (MAM) among adolescent girls in rural and urban Nigeria: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.J.; Cook-Wiens, G.; Johnson, B.D.; Braunstein, G.D.; Berga, S.L.; Stanczyk, F.Z.; Pepine, C.J.; Merz, C.N.B.; Shufelt, C.L. Age at Menarche and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes: Findings From the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute-Sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e012406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrman, B.J.; Moore, S.C.; Byrne, C.; Makhoul, I.; Kitahara, C.M.; de González, A.B.; Linet, M.S.; Weiderpass, E.; Adami, H.-O.; Freedman, N.D.; et al. Association of the Age at Menarche with Site-Specific Cancer Risks in Pooled Data from Nine Cohorts. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 2246–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Lee, Y.A.; Shin, C.H.; Suh, D.I.; Lee, Y.J.; Yon, D.K. Long-term health outcomes of early menarche in women: An umbrella review. QJM Int. J. Med. 2022, 115, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.R.V.; Baird, D.D.; Hartmann, K.E. Association of Age at Menarche with Increasing Number of Fibroids in a Cohort of Women Who Underwent Standardized Ultrasound Assessment. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 178, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, T.N.; Rosinger, A.Y. Reproductive Health Disparities in the USA: Self-Reported Race/Ethnicity Predicts Age of Menarche and Live Birth Ratios, but Not Infertility. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2021, 8, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acker, J.; Mujahid, M.; Aghaee, S.; Gomez, S.; Shariff-Marco, S.; Chu, B.; Deardorff, J.; Kubo, A. Neighborhood Racial and Economic Privilege and Timing of Pubertal Onset in Girls. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 72, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endocrine Society. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. 2025. Available online: https://www.endocrine.org/advocacy/position-statements/endocrine-disrupting-chemicals (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Fisher, M.M.; Eugster, E.A. What is in our environment that effects puberty? Reprod. Toxicol. 2014, 44, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Liu, P.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J. The adverse role of endocrine disrupting chemicals in the reproductive system. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1324993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucaccioni, L.; Trevisani, V.; Marrozzini, L.; Bertoncelli, N.; Predieri, B.; Lugli, L.; Berardi, A.; Iughetti, L. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and their effects during female puberty: A review of current evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uldbjerg, C.S.; Koch, T.; Lim, Y.-H.; Gregersen, L.S.; Olesen, C.S.; Andersson, A.-M.; Frederiksen, H.; Coull, B.A.; Hauser, R.; Juul, A.; et al. Prenatal and postnatal exposures to endocrine disrupting chemicals and timing of pubertal onset in girls and boys: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2022, 28, 687–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttke, D.E.; Sircar, K.; Martin, C. Exposures to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and age of menarche in adolescent girls in NHANES (2003–2008). Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 1613–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, A.; Aydin, A.; Büyükgebiz, A. Thematic Review of Endocrine Disruptors and Their Role in Shaping Pubertal Timing. Children 2025, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moodie, J.L.; Campisi, S.C.; Salena, K.; Wheatley, M.; Vandermorris, A.; Bhutta, Z.A. Timing of pubertal milestones in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, T.; Brown, L.J. Timing and determinants of age at menarche in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e003689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.L.; Harrison, K.; Viner, R.M.; Costello, A.; Heys, M. Adolescent cohorts assessing growth, cardiovascular and cognitive outcomes in low and middle-income countries. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S. Why should we be concerned about early menarche? Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2021, 64, 26–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibitoye, M.; Choi, C.; Tai, H.; Lee, G.; Sommer, M. Early menarche: A systematic review of its effect on sexual and reproductive health in low-and middle-income countries. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, A.M.R.L.; Laufer, M.R.; Breech, L.L. Menstruation in girls and adolescents: Using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 2245–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, A.C. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 1705–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, H. Phthalates and Their Impacts on Human Health. Healthcare 2021, 9, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, A.; Herrmann, S.; Lucas, M. The role of endocrine-disrupting phthalates and bisphenols in cardiometabolic disease: The evidence is mounting. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2022, 29, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, L.G.; Philippat, C.; Nakayama, S.F.; Slama, R.; Trasande, L. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: Implications for human health. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.S. Relationships of Lead, Mercury and Cadmium Levels with the Timing of Menarche among Korean Girls. Child Health Nurs. Res. 2020, 26, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igra, A.M.; Rahman, A.; Johansson, A.L.; Pervin, J.; Svefors, P.; El Arifeen, S.; Vahter, M.; Persson, L.; Kippler, M. Early Life Environmental Exposure to Cadmium, Lead, and Arsenic and Age at Menarche: A Longitudinal Mother–Child Cohort Study in Bangladesh. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 027003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malin, A.J.; Busgang, S.A.; Garcia, J.C.; Bose, S.; Sanders, A.P. Fluoride Exposure and Age of Menarche: Potential Differences Among Adolescent Girls and Women in the United States. Expo. Health 2022, 14, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, K.G.; Berger, K.P.; Kogut, K.; Parra, K.; Lustig, R.H.; Greenspan, L.C.; Calafat, A.M.; Ye, X.; Eskenazi, B. Association of phthalates, parabens and phenols found in personal care products with pubertal timing in girls and boys. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 34, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigambo, F.M.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X.; Yu, Q.; Wu, D.; Wang, X.; Xia, Y. Exposure to a mixture of personal care product and plasticizing chemicals in relation to reproductive hormones and menarche timing among 12–19 years old girls in NHANES 2013–2016. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 170, 113463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James-Todd, T.; Terry, M.B.; Rich-Edwards, J.; Deierlein, A.; Senie, R. Childhood Hair Product Use and Earlier Age at Menarche in a Racially Diverse Study Population: A Pilot Study. Ann. Epidemiol. 2011, 21, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, J.A.; Tehranifar, P.; Flom, J.D.; Terry, M.B.; James-Todd, T. Hair product use, age at menarche and mammographic breast density in multiethnic urban women. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasper-Sonnenberg, M.; Wittsiepe, J.; Wald, K.; Koch, H.M.; Wilhelm, M. Pre-pubertal exposure with phthalates and bisphenol A and pubertal development. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, D.J.; Sánchez, B.N.; Téllez-Rojo, M.M.; Lee, J.M.; Mercado-García, A.; Blank-Goldenberg, C.; Peterson, K.E.; Meeker, J.D. Phthalate and bisphenol A exposure during in utero windows of susceptibility in relation to reproductive hormones and pubertal development in girls. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, K.J.; Hartman, T.J.; Taylor, E.V.; Rybak, M.E.; Northstone, K.; Marcus, M. Exposure to phytoestrogens in utero and age at menarche in a contemporary British cohort. Environ. Res. 2017, 155, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, A.M.; Corvalan, C.; Calafat, A.M.; Ye, X.; Mericq, V.; Pereira, A.; Michels, K.B. Childhood and adolescent phenol and phthalate exposure and the age of menarche in Latina girls. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.S.; Pajak, A.; Pinney, S.M.; Windham, G.C.; Galvez, M.; Rybak, M.; Silva, M.J.; Ye, X.; Calafat, A.M.; Kushi, L.H.; et al. Associations of urinary phthalate and phenol biomarkers with menarche in a multiethnic cohort of young girls. Reprod. Toxicol. 2017, 67, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanck, H.M.; Marcus, M.; Tolbert, P.E.; Rubin, C.; Henderson, A.K.; Hertzberg, V.S.; Zhang, R.H.; Cameron, L. Age at Menarche and Tanner Stage in Girls Exposed In Utero and Postnatally to Polybrominated Biphenyl. Epidemiology 2000, 11, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, K.J.; Howards, P.P.; Smarr, M.M.; Flanders, W.D.; Northstone, K.; Daniel, J.H.; Calafat, A.M.; Sjödin, A.; Marcus, M.; Hartman, T.J. Prenatal exposure to mixtures of persistent endocrine disrupting chemicals and early menarche in a population-based cohort of British girls. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 276, 116705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harley, K.G.; Rauch, S.A.; Chevrier, J.; Kogut, K.; Parra, K.L.; Trujillo, C.; Lustig, R.H.; Greenspan, L.C.; Sjödin, A.; Bradman, A.; et al. Association of prenatal and childhood PBDE exposure with timing of puberty in boys and girls. Environ. Int. 2017, 100, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Chung, E.; DeFranco, E.A.; Pinney, S.M.; Dietrich, K.N. Serum PBDEs and age at menarche in adolescent girls: Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004. Environ. Res. 2011, 111, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Averina, M.; Huber, S.; Almås, B.; Brox, J.; Jacobsen, B.K.; Furberg, A.-S.; Grimnes, G. Early menarche and other endocrine disrupting effects of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in adolescents from Northern Norway. The Fit Futures study. Environ. Res. 2024, 242, 117703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.Y.; Maisonet, M.; Rubin, C.; Holmes, A.; Calafat, A.M.; Kato, K.; Flanders, W.D.; Heron, J.; McGeehin, M.A.; Marcus, M. Exposure to polyfluoroalkyl chemicals during pregnancy is not associated with offspring age at menarche in a contemporary British cohort. Environ. Int. 2011, 37, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinney, S.M.; Fassler, C.S.; Windham, G.C.; Herrick, R.L.; Xie, C.; Kushi, L.H.; Biro, F.M. Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Associations with Pubertal Onset and Serum Reproductive Hormones in a Longitudinal Study of Young Girls in Greater Cincinnati and the San Francisco Bay Area. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 097009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, B.; Wauters, N.; Rodríguez-Carrillo, A.; Portengen, L.; Gerofke, A.; Kolossa-Gehring, M.; Lignell, S.; Lindroos, A.K.; Fabelova, L.; Murinova, L.P.; et al. PFAS and Phthalate/DINCH Exposure in Association with Age at Menarche in Teenagers of the HBM4EU Aligned Studies. Toxics 2023, 11, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathey, A.; Watkins, D.J.; Sánchez, B.N.; Tamayo-Ortiz, M.; Solano-Gonzalez, M.; Torres-Olascoaga, L.; Téllez-Rojo, M.M.; Peterson, K.E.; Meeker, J.D. Onset and tempo of sexual maturation is differentially associated with gestational phthalate exposure between boys and girls in a Mexico City birth cohort. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinn, L.A.; Ghazarian, A.A.; Joseph Su, L.; Ellison, G.L. Urinary bisphenol A and age at menarche among adolescent girls: Evidence from NHANES 2003–2010. Environ. Res. 2015, 136, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, D.; Xiong, J.; Cheng, G. Long-term exposure to ambient PM2.5 and its components on menarche timing among Chinese adolescents: Evidence from a representative nationwide cohort. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Q.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Rao, B.; Ji, X.; Xu, Z.; Wu, S.; Deng, F. Long-term exposures to ambient particulate matter and ozone pollution with lower extremity deep vein thrombosis after surgical operations: A retrospective case-control study in Beijing, China. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Pan, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, J. Association of pyrethroids exposure with onset of puberty in Chinese girls. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 227, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igra, A.M.; Trask, M.; Rahman, S.M.; Dreij, K.; Lindh, C.; Krais, A.M.; Persson, L.; Rahman, A.; Kippler, M. Maternal exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons during pregnancy and timing of pubertal onset in a longitudinal mother-child cohort in rural Bangladesh. Environ. Int. 2024, 189, 108798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, A.C.; Chappell, V.A.; Fenton, S.E.; Flaws, J.A.; Nadal, A.; Prins, G.S.; Toppari, J.; Zoeller, R.T. EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocr. Rev. 2015, 36, E1–E150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namulanda, G.; Taylor, E.; Maisonet, M.; Barr, D.B.; Flanders, W.D.; Olson, D.; Qualters, J.R.; Vena, J.; Northstone, K.; Naeher, L. In utero exposure to atrazine analytes and early menarche in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children Cohort. Environ. Res. 2017, 156, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, J.J.; Mijal, R.S. Adverse Effects of Low-Level Heavy Metal Exposure on Male Reproductive Function. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 2010, 56, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hood, R.B.; Hart, J.E.; Laden, F.; Rosner, B.; Chavarro, J.E.; Gaskins, A.J. Exposure to Particulate Matter Air Pollution and Age of Menarche in a Nationwide Cohort of U.S. Girls. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 107003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smarr, M.M.; Avakian, M.; Lopez, A.R.; Onyango, B.; Amolegbe, S.; Boyles, A.; Fenton, S.E.; Harmon, Q.E.; Jirles, B.; Lasko, D.; et al. Broadening the Environmental Lens to Include Social and Structural Determinants of Women’s Health Disparities. Environ. Health Perspect. 2024, 132, 15002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osinubi, A.; Angeles, C.P.L.-D.L.; Poitevien, P.; Topor, L.S. Are Black Girls Exhibiting Puberty Earlier? Examining Implications of Race-Based Guidelines. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2021055595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zota, A.R.; Shamasunder, B. The environmental injustice of beauty: Framing chemical exposures from beauty products as a health disparities concern. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 217, 418.e1–418.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, M.S.; Upadhyaya, S.; Nzegwu, A.W.; Kuiper, J.R.; Buckley, J.P.; Aschner, J.; Barr, D.; Barrett, E.S.; Bennett, D.H.; Dabelea, D.; et al. Racial and ethnic differences in prenatal exposure to environmental phenols and paraben in the ECHO chort. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2025, 35, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njoku, A.U.; Sampson, N.R. Environment Injustice and Public Health. In Handbook of Social Sciences and Global Public Health; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).