Abstract

The general spread of water safety awareness and enforcement often masks the escalating risks of emerging contaminants (ECs) that evade standard detection and monitoring techniques. Traditional monitoring infrastructures depend heavily on localized laboratory-based testing, which is expensive, time-consuming, and reliant on specialized infrastructure and skilled personnel. While specific types of ECs and detection technologies have been examined in numerous studies, a significant gap remains in compiling and commenting on this information in a concise framework that incorporates global impact and monitoring strategies. We aimed to compile and highlight the impact ECs have on global water safety and how advanced sensor technologies, when integrated with digital tools such as the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), geographic information systems (GIS), and cloud-based analytics, can enhance real-time EC detection and monitoring. Recent case studies were reviewed for the assessment of EC types, global contamination, and current state-of-the-art for EC detection and their limitations. An emphasis has been placed on areas that remain unaddressed in the current literature: a cross-disciplinary integration of integrated sensor platforms, multidisciplinary research collaborations, strategic public–private partnerships, and regulatory bodies engagement will be essential in safeguarding public health, protecting aquatic ecosystems, and ensuring the quality and resilience of our water resources worldwide.

1. Introduction

A deceptively pure glass of tap water consumed at home may hold more than what meets the eye. A complex blend of emerging contaminants (ECs), including diverse physical, chemical, and microbial components, often enters various environmental sources, while evading conventional detection and monitoring systems [1]. These include not only familiar suspects like pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) and pesticides, but also novel threats that have only recently been recognized, such as microplastics, nanomaterials, and even antibiotic-resistant genes (ARGs) [2]. A recent review defines ECs as newly identified synthetic or naturally occurring chemical or biological agents found in the environment and considered potentially hazardous [3]. ECs are strikingly pervasive: they encompass everything from birth-control hormones in water bodies and persistent industrial compounds like per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) used in nonstick coatings, to potent toxins produced by harmful algal blooms, trace antibiotics, etc. Some other notorious ECs include fire retardants such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), flame-proof fabrics, plasticizers (phthalates), and detergents. Another pressing category, consisting of microplastics and nanoplastics, infiltrates ecosystems by the creation of micro-fragments during the degradation of larger plastics. Engineered nanomaterials or microscopic particles shed from synthetic clothing are also considered as ECs. Biological emerging contaminants include antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and viruses that proliferate in water sources and cause active contamination. Most of the contaminants or pollutants highlighted are not novel threats but are often present in concerning concentrations or levels globally [4].

To understand the scale of operation, take into consideration a meta-analysis of 22 national and regional inventories (2014–2019) that identified more than 350,000 distinct chemicals and mixtures that have been registered for global commercial use to date [5]. But only a tiny fraction is actively monitored, and barely a few hundred appear on priority pollutant or contaminant lists [6]. This gross disparity underscores a critical surveillance and knowledge gap: many ECs remain uncharacterized, unquantified, and unregulated, despite their potential ecological impacts Additionally, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) observed that ECs often escape removal by conventional treatment technologies, thus coming under heightened scientific and regulatory scrutiny [7]. Despite the long-standing presence of ECs and toxins, our scientific understanding of them is still evolving.

The monitoring approaches employed currently remain localized and heavily reliant on laboratory-based testing, which limits real-time detection and rapid response rates. There is, therefore, an urgent need to develop and integrate innovative sensing and analytical frameworks capable of identifying ECs efficiently and adaptively. We aim to compile and highlight the impact ECs have on global water safety and determine how advanced sensor technologies are when integrated with digital tools such as the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), geographic information systems (GIS), and cloud-based analytics, which can enhance real-time detection of ECs. Recent case studies were reviewed for the assessment of EC types, global contamination patterns, and current state-of-the-art for EC detection and their limitations. By evaluating current research, identifying technological and infrastructural gaps, and proposing integrative strategies, this Opinion article seeks to contribute to the advancement of a scalable, standardized, collaborative approach for safeguarding water quality and public health worldwide.

2. Global Impact

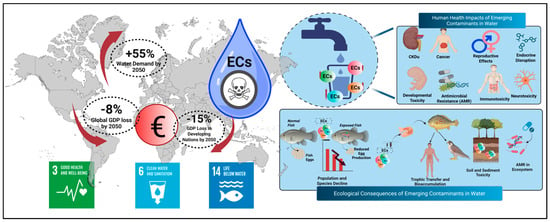

A scientifically grounded overview of the development, distribution, and subsequent implications of ECs in global water systems is required for the refinement of detection and monitoring methods. A major objective of this work is the illustration of the collective effect of EC contamination on various economies, with an emphasis on human health and ecosystem stability. The case studies were selected based on geographical diversity and data availability from peer-reviewed, high-impact studies and reports of reputed institutions including The World Health Organization (WHO), Global Commission on the Economics of Water (GCEW), and other EU monitoring programs. The significant and rapidly escalating damage that ECs cause and the subsequent implications for both economies and ecosystems have been highlighted in Figure 1. The global demand for freshwater is projected to increase by approximately 55% by 2050 [8], intensifying shortages that are already contributing to the migration of populations. But even in areas with guaranteed water availability, safe consumption is often not assured. A recent analysis by the GCEW indicates that water-related challenges could reduce roughly 8% of global GDP (gross domestic product) by 2050, with losses of up to 15% in developing economies (without remedial action) [9].

Figure 1.

Global challenges and health–ecological impacts of ECs in water systems: Global water demand is projected to rise by over 55% by 2050, and ECs pose a growing threat to both human health and aquatic ecosystems. ECs enter drinking water supplies and bioaccumulate in aquatic organisms. Human health effects linked to EC exposure include chronic kidney disease, cancer, reproductive and developmental toxicity, endocrine disruption, neurotoxicity, immunotoxicity, etc. Ecologically, ECs reduce reproductive success in fish, drive species decline, and contribute to trophic transfer, sediment contamination, bioaccumulation, environmental persistence, AMR development and spread, and extinction of wildlife species. Addressing the ECs challenge is therefore critical to achieve the SDGs on health (SDG 3), clean water (SDG 6), and aquatic biodiversity (SDG 14). Created in BioRender. Thenuwara, G. (2025) https://BioRender.com/6xju2nt (accessed on 2 December 2025).

The growing ecological impact of ECs is becoming increasingly apparent. Many wildlife species in waterways are exposed to pharmaceuticals and other pollutants discharged from urban centers, where tiny plastic beads and nanoparticles accumulate in food webs and disrupt ecosystems; chemical contaminants are now considered a leading cause of extinction for a number of wildlife species [10]. Trace-level ECs elicit physiological stress responses in organisms ranging from zooplankton to birds, while PFASs bioaccumulate in fish and birds and impair reproductive and immune function [11]. Contrary to popular belief, the bigger crisis is not the exhaustion of water but the depletion of clean water [12]. Polluted water, air, and soil are linked to millions of premature deaths each year [13], and endocrine-disrupting chemicals, including BPA, parabens, and PFASs, interfere with hormones at parts-per-trillion (ppt) concentrations [11]. Cyanotoxins produced by harmful algal blooms pose threats to public health, ecosystems, and fish populations [14], while residues of antibiotics accelerate the spread of ARBs and genes, which present one of the largest public health risks today [9]. Similar trends are also observed across countries and continents. Some pertinent case studies have been highlighted as follows:

2.1. Asia

Kulathunga and colleagues reported that 23% of the rice samples analyzed in the Polonnaruwa district, Sri Lanka (where the prevalence of chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu) is higher) exceeded the permissible limit for the total daily intake (TDI) of lead (Pb) [15]. Additionally, analysis of the hazard index for cadmium (Cd), arsenic (As), and lead (Pb) indicated that 26% of the rice samples could pose a health risk to consumers in this population [15]. An audit of commercial (bottled) jar water in Bangladesh detected arsenic and thermotolerant coliforms in nearly half of the brands on sale, highlighting significant and serious regulatory oversight [16].

In India’s Brahmaputra floodplain (Darrang district), 347 wells were analyzed for arsenic, fluoride, and iron [17]. Thakur and coworkers reported elevated levels of these ECs in many samples and indicated significant carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic health risks [17]. Likewise, groundwater in China’s Guide Basin showed co-enrichment of arsenic (up to 0.355 ppm) and fluoride (0.005 ppm); geochemical modeling traced the mobilization to alkali desorption and carbonate weathering under high pH conditions [18].

2.2. Europe

A 2025 target and suspect screening campaign around Lyon (France) found that 67% of French tap water samples exceeded the EU’s newly established 0.1 ppm threshold for total per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) [19]. Also, the multiplex LC-MS/MS analysis of Spain’s Llobregat and Besòs rivers detected 78 pharmaceutical compounds, including diclofenac and carbamazepine, with risk quotients above ecological safety thresholds [20]. Similar trends have been observed across other countries and continents. Additional regional investigations, such as the assessment of heavy metal contamination in the Boka Kotorska Bay (UNESCO World Heritage Site) using Energy Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence (ED-XRF) and pollution indices (EF, Igeo, and PLI) further demonstrate localized sediment pollution and ecological stress [21]. These findings also overturn the belief that economically stable countries are shielded from the effects of ECs contamination.

2.3. Africa

In South Africa, antibiotics such as tetracycline (0.0013 ppm) and sulfathiazole (0.0011 ppm), along with resistance genes, were recently detected downstream of a wastewater treatment plant on the Msunduzi River [22]. In another study conducted in South Africa, a non-targeted screening workflow established on a high-resolution quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer coupled to an ultrahigh performance liquid chromatograph (UHPLC-QTOF-MS) was used for the identification of pollutants. PPCPs and metabolites made up 40%, biological and industrial compounds made up 24% and 18%, respectively, while pesticides and food additives made up 4% of the observed results. Additionally, antiretroviral drugs, along with a wide range of novel ECs, were confirmed for the first time in this region [23]. PPCPs and polymers (polyethylene and polypropylene fibers) were also reported in the Middle Eastern and North Africa (MENA) region [24]. Additionally, West African regions, including Ghana, Nigeria, and Cameroon, reported the highest number and concentrations of PPCPs. The reported results revealed about 27 groups and 112 compounds with concentrations ranges; in drinking water (200,000 to 3,200,000 ng/L), in groundwater (12 to 700,000 ng/L), in surface water (0.42 to 107,800,000 ng/L), in wastewater (8.5 to 121,310,000 ng/L), and in tap water (440 to 421,700 ng/L) [25].

2.4. America

Globally, an investigation of 1052 sites across 104 countries found that one quarter of rivers, particularly in Latin America, contain pharmaceutical mixtures at concentrations posing significant risks [26]. Additionally, another review compiled 79 documents (2007–2019) centered around the occurrence, concentrations, and sources of PhACs and hormones in different types of water bodies in Latin America and confirmed the presence of 159 PhACs due to wastewater in Ecuador and Brazil [27]. The rapid urbanization of various coastal cities has also significantly increased EC occurrence. PAHs were detected in the range 216.45 to 2166.6 µg/kg in the Maricá Lagoon complex. Reported results indicated that the transitional zone of the Maricá Lagoon complex was particularly impacted. For instance, synthetic sterols were measured to be at 748.05 µg/kg and Bisphenol-A at 55.22 µg/kg [28].

2.5. Australia

An investigation across the entirety of the Sydney estuary reported an alarming number of PPCPs, pesticides, and artificial sweeteners, with an indirect discharge of sewage water (stormwater overflow) and a direct discharge of domestic wastewater into the estuary [29]. Another study of different sewage treatment plants across Northern Queensland identified and quantified multiple classes of ECs, including PPCPs, PFASs, heavy metals (HMs) and polycyclic musks (PMs) in biosolids. The results revealed significant variations in ECs concentration, which was characterized by the mechanisms of the upstream sewage network, e.g., high concentration of Zn and Cu (2430 and 1050 mg/kg, respectively) was reported in biosolids obtained from a small agricultural shire [30].

2.6. Antarctica

An investigation was conducted on various biota samples collected from Antarctica (2018–2020) including fish muscle, seal muscle and placenta, and penguin samples. The reports pointed towards the occurrence and persistence of HMs, flame retardants, polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), and dioxins, while the polychlorinated bisphenols (PCBs) were frequently detected. An additional target screening revealed the presence of 33 contaminants from various chemical classes (42% PPCPs and 30% industrial chemicals (ICs) [31]. Another review described the impact of settlements in Antarctica, including the Mario Zucchelli Italian Research Station (MZS) in Terra Nova Bay. Contaminants, including methylxanthines, artificial sweeteners, taurine, nicotine, pharmaceuticals, UV filters, and industrial additives, were reported at concentrations ranging from dozens of ng/L to μg/L [32].

These results demonstrate that EC contamination in water is truly a global challenge, persistent and unhindered by geographical constraints. Thus, the early implementation of preventative and monitoring measures is becoming increasingly vital, surpassing the effectiveness of reactive measures taken after new contaminants are detected.

3. Types of Emerging Contaminants and Environmental Behavior

3.1. Emerging Contaminant Types

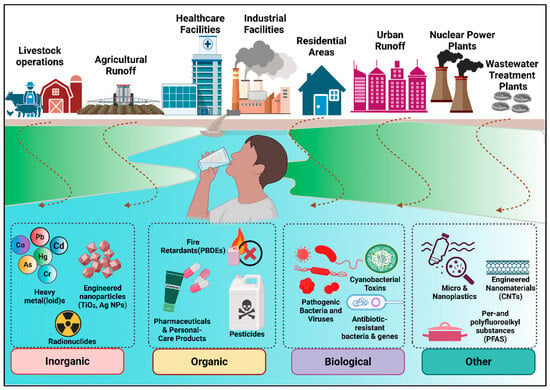

To understand the vast area of interest and provide a coherent framework for the interpretation of the wide spectrum of ECs, we adopted the classification proposed by Wang et al. [3]. They divided them into four categories: inorganic, organic, biological, and other ECs. This scheme offers a grouping system that facilitates differentiation based on origin, composition, and risk profiles, and thus aligns well with our focus. We have compiled and presented, in Figure 2 and Table 1, the various types, sources, and risks associated with ECs that originate from diverse origins and ultimately reach and contaminate our drinking water supplies.

Figure 2.

Emerging contaminants (ECs) types, sources, and associated health risks in aquatic environments: ECs originate from diverse sources such as agriculture, healthcare, industry, households, and wastewater, etc. Once released, they enter our aquatic systems and may ultimately contaminate drinking water. ECs are associated with a range of ecological and human health effects, and long-term environmental persistence, AMR development, and the extinction of wildlife species. Created in BioRender. Thenuwara, G. (2025) https://BioRender.com/dnmoejg (accessed on 2 December 2025).

Table 1.

Various ECs with type, examples, sources, and associated risks.

Inorganic ECs: These are non-carbon-based chemicals but include heavy metals, metalloids, metal complexes, mineral acids, and certain salts. Lead, mercury, arsenic, cadmium, chromium, nitrates, phosphates, etc., are the most common examples of inorganic ECs. Their major sources are industrial runoff, agriculture, mining, smelting, electronic waste, and natural geological processes. The concentrations in affected aquifers commonly reach 10–100 µg/L, and in severe cases (e.g., arsenic in South Asian groundwater), exceed 50–100 µg/L [15]. These contaminants are linked to chronic neurotoxicity, renal and hepatic dysfunction, carcinogenicity, and bioaccumulation in aquatic food webs. Nanometallic particles such as silver or zinc oxide (released from sunscreens and consumer products) have been detected (ng/L–µg/L levels), with demonstrated toxicity to aquatic organisms through oxidative stress pathways [33].

Organic ECs: These include carbon-based molecules such as pharmaceutical drugs, pesticides, consumer chemicals, and personal care products, phthalates, PBDEs, and herbicides. Organic ECs are commonly released from households, hospitals, farms, and industrial activities. These contaminants typically occur at ng/L to low-µg/L concentrations in surface and groundwater, while some endocrine-disrupting chemicals (e.g., estradiol) show biological activity at 1–10 ng/L [34]. Associated health risks include hormone disruption and impaired development (e.g., parabens), as well as carcinogenic and neurotoxic effects (e.g., flame retardants, pesticides). Their limited biodegradability further increases the risk of bioaccumulation and environmental persistence [35].

Biological ECs: Biological ECs include pathogenic microorganisms and natural toxins such as cyanotoxins produced by algal blooms. Sewage discharges and livestock wastes can carry Cryptosporidium, E. coli, antibiotic-resistant Salmonella, or even viruses like norovirus or SARS-CoV-2. Effluents from hospitals and agricultural operations introduce ARBs bolstered by ARGs into water bodies. Cyanotoxins produced by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) are regarded as one of the most serious water-quality threats to both human and ecosystem health, impairing liver and nervous system function. Pathogens often occur in contaminated waters in the range 102–106 CFU/100 mL, and concentrations of microcystin in eutrophic lakes commonly occur in the range 0.1–10 µg/L [36,37].

Other ECs: These include microplastics and nano-plastics, PFASs, and engineered nanomaterials. Microplastics float in water, adsorb pollutants, and are ingested by wildlife. PFASs are highly bio-accumulative and associated with immunological and developmental toxicity. Microplastic concentrations in rivers and wastewater generally vary between 102–106 particles/m3, depending on land-use intensity and efficiency of treatment. PFASs persist at ppt-ng/L levels, but certain types, such as PFOA and PFOS, display toxicity at low concentrations and show half-lives of years to decades.

Nanomaterials can migrate into water systems under varying conditions, which potentially leads to human exposure through ingestion. The ability of certain nanomaterials, such as silver (Ag), titanium dioxide (TiO2), and zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles, to induce inflammation, oxidative stress, genotoxicity, and cellular dysfunction is concerning. Although these ECs often arise from novel materials, they pose distinct and emerging hazards to both ecosystems and human health.

3.2. Environmental Behavior Across EC Categories

These EC classes have marked differences but present overlapping factors in the context of environmental behaviors. Organic ECs exhibit chemical stability and resistance to degradation, complicating removal through conventional treatment processes. Inorganic ECs have long-term persistence that is driven by geogenic sources with strong environmental stability. Biological ECs exhibit episodic and seasonally variable spikes influenced by rainfall, wastewater overflows, or algal blooms. The “Other ECs” category is marked by exceptional persistence (PFASs), complex mobility (nanomaterials), and scarce toxicological data. The ranges of EC occurrences span from ppt to mg/L and reflect large differences in potency, environmental half-life, and exposure pathways. These contrasts underscore the need for monitoring systems that can detect categorically integrated ECs (at trace concentrations) across diverse environmental settings. The representative examples, sources, and risks for these EC categories [3,4,5,7,11,13,14,15] are summarized in Table 1.

4. Current State-of-the-Art: Detection Methods and Limitations

EC detection in water for timely intervention and enforcement is still a significant challenge. The diverse nature of unregulated chemicals further complicates monitoring, because each chemical requires specific detection strategies. Currently, water samples are transported to analytical laboratories where techniques such as liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) are applied. They provide unparalleled sensitivity and specificity but are inherently laboratory-based, time-consuming, require sample preparation, and are entirely dependent on accessible infrastructure and expert personnel. Additionally, inter-laboratory comparability is still limited, owing to discrepancies due to issues such as sample handling, calibration, and/or analytical parameters.

Field-deployable methods include immunoassay and colorimetric kits, which are cost effective and portable but offer limited detection ranges and inconsistent accuracy in real-world scenarios. Multi-parameter probes are useful for general water-quality monitoring (pH, conductivity, dissolved oxygen) but cannot be used to detect trace-level ECs or for providing information on chemical mixtures. Likewise, molecular techniques such as qPCR allow for the determination of pathogenic genes with heightened sensitivity; however, they face similar challenges to their chemical counterparts.

Most importantly, real-world validation of detection methods is generally poor. While many proof-of-concept sensors and prototype systems show great promise in controlled laboratory settings, most fail to demonstrate accuracy, stability, or reproducibility when applied in complex environmental matrices. In addition, factors like temperature variability, turbidity, and biofouling can seriously degrade sensor performance, yielding false readings or data loss. Moreover, a deficiency in harmonized method validation procedures reduces any confidence in measured concentrations [38]. However, recent pilot-scale initiatives, such as the ‘EU B-WaterSmart’ demonstration for wastewater reuse [39] and modular IoT-based water monitoring networks [40], illustrate the gradual translation of laboratory advances into real-world EC detection and management applications.

To address these gaps, there is an urgent need for robust, low-cost, low-power in situ sensors capable of automated sampling and multi-analyte detection directly at sources of contamination. However, the translation of such technologies into reliable commercial products has been slow to date due to validation challenges, high production costs, and inconsistent performance during field deployments. Many measures currently employed also fail to address practical needs that include site-specific variability and long-term operation.

5. Conclusive Remarks

5.1. Future Technologies in EC Monitoring

The trajectory of ECs detection and management in water bodies will include advances in integrated sensor platforms that unify multiple detection modalities. Rapid sensors, such as electrochemical sensors, remain highly valuable because of their quick response, sensitivity, low cost, and portability. However, the field is transitioning toward multi-faceted architecture that incorporates electrochemical, optical, piezoelectric, and microfluidic technologies [35,41,42,43]. For instance, a review by Baranwal et al. (2022) notes that LODs generally attained in routine practice with electrochemical sensors lie within the low micromolar to sub-micromolar range (~10−7 M) for a wide array of analytes, although in some advanced variants, the detection of femtomolar levels (10−15 M) has been reported [41]. Further, in the review on aptamer-nanomaterials by Mahmoudpour et al. (2022), electrochemical aptasensors for pesticide detection exhibited detection limits as low as ~10−12 M, with wide linear ranges extending up to 10−6 M [42]. Fan et al. (2019) reported a label-free electrochemical aptasensor for atrazine (ATZ) with a linear range of 0.25–250 pM and LOD of 0.10 pM [43]. These hybrid systems improve the robustness of detection, selectivity, and adaptability across diverse environmental contexts [43]. The accelerated development of multi-analyte sensor arrays integrated with microfluidic platforms enables the simultaneous detection of various contaminants and a substantial reduction in turnaround time.

Lab-on-a-chip technologies consolidate preparation, processing, and detection into automated systems suitable for rapid, in situ monitoring [44,45]. Recent advancements have expanded to include triboelectric nanosensors (TENSs) that offer exceptional sensitivity for real-time water quality monitoring, with applications ranging from mercury detection to bacterial biosensors [46]. Nano-biosensors have transformed environmental monitoring through their exceptional sensitivity, with the ability to detect HMs like lead at parts per billion (ppb) levels and organophosphate pesticides in agricultural runoff. These nanosensor technologies utilize diverse recognition mechanisms, including aptamers and enzyme-based systems, providing rapid and selective detection methods that are essential for comprehensive water quality assessment [47,48].

Deployable sensing devices further expand avenues for operational versatility, ranging from plant-wearable systems for continuous pesticide monitoring to long-duration buoy-based deployments [49,50]. Quantum sensing technology represents a revolutionary frontier in water quality monitoring, offering ultra-sensitive detection capabilities that surpass conventional methods. Quantum sensors exploit superposition and entanglement principles to achieve detection limits as low as 0.1 ppb for contaminants like lead, compared to 0.4 ppb for conventional sensors. These quantum-enhanced systems provide non-destructive analysis, real-time monitoring, and miniaturization potential that enables deployment in remote locations and handheld devices for rapid water quality assessments [51]. Regulatory agencies, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (US-EPA), are piloting field-deployable, real-time water quality monitoring networks, thus displaying the feasibility of large-scale implementation [52].

Water quality monitoring is now being transformed with the integration of digital technologies including IoT sensors, edge computing, AI, ML, cloud-based analytics, and GIS. The integration of edge-enabled systems supports localized data processing, reduces latency, bandwidth usage, and energy demand, and ensures timely and effective monitoring results [53]. IoT sensor networks execute continuous capture of high-resolution data and transmit only relevant information to centralized platforms, analytics, and visualization tools for real-time insights. On this foundation, the AI and ML algorithms make use of hydrological and meteorological data to identify subtle contamination that usually evades conventional systems. Predictive models can map the dispersion of ECs, identify sources of pollution, and support impact assessment [53]. AI-driven adaptive calibration also serves to extend sensor longevity and performance by correcting against environmental interference. Moving forward, AI-enabled digital twins of water systems may allow for real-time simulation, optimized operations, and automated decision-making under robust, standardized regulatory frameworks.

Despite these strengths, these systems still have significant limitations, thereby highlighting the need for multidisciplinary strategies and collaborative approaches to develop robust, ML adaptive frameworks which are capable of integrating heterogeneous data streams and optimizing computational resources across diverse monitoring contexts. Digital twin technology is emerging as a powerful tool for water resource management, creating real-time virtual models of water systems that integrate multiple data streams for comprehensive monitoring and predictive analysis. These systems combine NASA and ESA satellite data for historical trend analysis, weather information, in situ monitoring, vertical profiling, and bathymetric mapping to create detailed digital representations of water bodies. The Global Water Quality Digital Twin (GWDT) specifically addresses AMR monitoring, a critical concern as the EU mandates municipalities with populations over 100,000 to monitor AMR levels in water by 2027. Advanced digital twin platforms can process over 1 million data sets daily, enabling predictive analytics, automated decision-making, and proactive water management strategies [54,55,56].

Blockchain technology is increasingly being integrated into water management systems to ensure data integrity, transparency, and secure water rights trading. Blockchain provides tamper-proof data recording from water sources to end-users, ensuring accountability and reducing mishaps in water supply chains [57]. Along with professional monitoring, user-friendly mobile applications and near-field communication (NFC) technologies enable local communities to participate, expanding spatial coverage. This democratization of environmental intelligence not only improves accuracy and monitoring scope but also strengthens public engagement in promoting long-term resilient water management. Remote sensing technologies continue to advance, with hyperspectral sensors and quantum-enhanced remote sensing capabilities providing cost-effective, large-scale water quality monitoring with high temporal coverage. These systems can capture detailed spectral information for identifying specific contaminants and monitoring parameters such as chlorophyll levels, total phosphorus, and dissolved organic matter across diverse water bodies, from urban reservoirs to oceanic environments [58,59].

5.2. Policy and Governance Measures

However, technical innovation, along with regulatory standardization, would prove effective for EC contamination detection and monitoring. An integrated cross-disciplinary approach involving scientists, engineers, digital technologies, policymakers, regulatory bodies, and consumers is required to maximize capabilities. Regular engagement with stakeholders is essential to ensure sensor innovation and economic viability for field deployment. Additionally, standardized validation protocols, regulatory frameworks, and robust calibration will promote and ensure consistency across different areas and build confidence in sensor performance and reliability. The regulatory environment is experiencing a rapid overturn due to the recognition of ECs as a global issue, such as the EU adopting its fourth updated watchlist listing twelve pollutants including pesticides, pharmaceuticals, sunscreen agents, and tire antioxidants that need to be monitored in EU Member States for a minimum of two years to decide on extensive risk and possible inclusion in priority substance lists under the Water Framework Directive [60]. However, several limitations remain:

- Exorbitant expenses for quantum technologies, advanced sensors, and digital twin platforms can hamper large-scale deployment;

- Lack of internationally standardized workflows and detection limits for sensor calibration, validation, and data interoperability limits comparability across regions;

- Data governance, equitable access, and commercialization complications include the translation of research prototypes into operational systems.

The cross-disciplinary and international nature of these challenges requires collaboration. The involvement of scientists, engineers, policymakers, regulatory agencies, and local communities will ensure stakeholder-driven sensor innovations, economic feasibility, and robust strategies for monitoring. Public–private partnerships can help speed up wider adoption, while international policy frameworks should bring in uniformity in monitoring protocols, data sharing, and operational practices regarding ECs management.

Future research should critically engage with the One Health approach, emphasizing interconnectivity between human, animal, and environmental activities and health in EC monitoring. This holistic framework offers an effective pathway to integrated water governance; however, its global translation is presented with several challenges: sectoral data standardization, governance and policy coordination, and resource sharing, particularly in developing economies [60]. To help overcome these barriers, federated learning, hybrid architectures at the edge-cloud, and digital twins using AI will provide secure, cross-domain data sharing without compromising privacy. Advanced sensing, AI/ML, quantum technologies, blockchain, and digital twins will contribute toward early contaminant detection, proactive risk mitigation, and ecosystem protection in an integrated manner. Integrating all these technologies within a pragmatic One Health framework will be enabled through continued efforts by WHO, FAO, and UNEP.

In summation, future efforts centered around EC monitoring will be based on the integration of effective governance, advanced sensing technologies and digital intelligence. Innovations like AI-driven multi-sensor systems, quantum and nano-sensing, and digital twins push water monitoring from reactive to predictive EC management. Policy and governance approaches like One Health can help overcome several challenges in terms of cost, standardization, and data sharing. This thereby enables sustainable, transparent, and resilient water systems that protect ecosystems and public health worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S.; software, G.T.; investigation, formal analysis & data curation, K.R., A.B. and B.S.; validation, A.B., K.R., G.T. and B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.S., A.B. and K.R.; writing—review and editing, B.S., A.S.N., C.O. and F.T.; visualization, G.T. and B.S.; supervision, B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge that all Figures in this article including the Graphical Abstract were Created in BioRender.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations & Symbols

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| ARB | Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria |

| ARGs | Antibiotic-Resistant Genes |

| As | Arsenic |

| ATZ | Atrazine |

| BPA | Bisphenol A |

| Cd | Cadmium |

| CKDu | Chronic Kidney Disease of Unknown Etiology |

| Co | Cobalt |

| CNFs | Carbon Nanofibers |

| CNTs | Carbon Nanotubes |

| Cr | Chromium |

| CR | Carcinogenic Risk |

| Cs | Cesium |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| ECs | Emerging Contaminants |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| ESBL | Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase |

| EU | European Union |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| GCEW | Global Commission on the Economics of Water |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| GWDT | Global Water Quality Digital Twin |

| Hg | Mercury |

| HMs | Heavy Metals |

| IoTs | Internet of Things |

| LC-MS | Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MRSA | Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| NFC | Near-Field Communication |

| PBDEs | Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers |

| PCBs | Polychlorinated Biphenyls |

| Pb | Lead |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PFAS | Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances |

| PFOA | Perfluorooctanoic Acid |

| PFOS | Perfluorooctane Sulfonate |

| Phthalates | Esters of Phthalic Acid (Plasticizers) |

| PMs | Polycyclic Musks |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| PPCPs | Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products |

| ppb | Parts Per Billion |

| ppt | Parts Per Trillion |

| qPCR | Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| TDI | Total Daily Intake |

| TENS | Triboelectric Nanosensors |

| TiO2 | Titanium Dioxide |

| UNEP | United Nations Environment Programme |

| U | Uranium |

| US-EPA | United States Environmental Protection Agency |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Nishmitha, P.S.; Akhilghosh, K.A.; Aiswriya, V.P.; Ramesh, A.; Muthuchamy, M.; Muthukumar, A. Understanding emerging contaminants in water and wastewater: A comprehensive review on detection, impacts, and solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 18, 100755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Prabhakar, R.; Barua, V.B.; Zekker, I.; Burlakovs, J.; Krauklis, A.; Hogland, W.; Vincevica-Gaile, Z. Microplastics in aquatic systems: A comprehensive review of its distribution, environmental interactions, and health risks. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 56–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Xiang, L.; Sze-Yin Leung, K.; Elsner, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Pan, B.; Sun, H.; An, T.; Ying, G.; et al. Emerging contaminants: A One Health perspective. Innovation 2024, 5, 100612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, M.; Gandhi, K.; Kumar, M.S. Emerging environmental contaminants: A global perspective on policies and regulations. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 332, 117344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Walker, G.W.; Muir, D.C.G.; Nagatani-Yoshida, K. Toward a Global Understanding of Chemical Pollution: A First Comprehensive Analysis of National and Regional Chemical Inventories. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 2575–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harish, H.; Jegatheesan, V. A Review of Sources, Worldwide Legislative Measures and the Factors Influencing the Treatment Technologies for Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs). Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2025, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-EP. Evidence Rising: The Emerging Pollutants Poisoning Our Environment. 2019. Available online: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/evidence-rising-emerging-pollutants-poisoning-our-environment (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Osei-Owusu, J.; Heve, W.K.; Duker, R.Q.; Aidoo, O.F.; Larbi, L.; Edusei, G.; Opoku, M.J.; Akolaa, R.A.; Eshun, F.; Apau, J.; et al. Assessments of microbial and heavy metal contaminations in water supply systems at the University of Environment and Sustainable Development in Ghana. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2023, 2, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disner, G.R.; Tareq, S.M. Emerging water contaminants in developing countries: Detection, monitoring, and impact of xenobiotics. Front. Water 2025, 7, 1584752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groh, K.; vom Berg, C.; Schirmer, K.; Tlili, A. Anthropogenic Chemicals as Underestimated Drivers of Biodiversity Loss: Scientific and Societal Implications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 707–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, S.Y.; Aris, A.Z. Revisiting the “forever chemicals”, PFOA and PFOS exposure in drinking water. npj Clean Water 2023, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GCEW. Global Commission on the Economics of Water. Available online: https://watercommission.org/ (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Fuller, R.; Landrigan, P.J.; Balakrishnan, K.; Bathan, G.; Bose-O’Reilly, S.; Brauer, M.; Caravanos, J.; Chiles, T.; Cohen, A.; Corra, L.; et al. Pollution and health: A progress update. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e535–e547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, B.W.; Lazorchak, J.M.; Howard, M.D.A.; Johnson, M.V.V.; Morton, S.L.; Perkins, D.A.K.; Reavie, E.D.; Scott, G.I.; Smith, S.A.; Steevens, J.A. In some places, in some cases, and at some times, harmful algal blooms are the greatest threat to inland water quality. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2017, 36, 1125–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulathunga, M.R.D.L.; Wijayawardena, M.A.A.; Naidu, R.; Wimalawansa, S.J.; Rahman, M.M. Health Risk Assessment from Heavy Metals Derived from Drinking Water and Rice, and Correlation with CKDu. Front. Water 2022, 3, 786487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahma, P.P.; Akter, S.; Haque, M.M.; Khirul, M.A. Probabilistic human health risk assessment of commercially supplied jar water in Gopalganj municipal area, Bangladesh. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1441313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R.; Nath, H.; Neog, N.; Bora, P.K.; Goswami, R. Groundwater hydrogeochemistry and potential health risk assessment through exposure to elevated arsenic in Darrang district of north bank plain of the Brahmaputra. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, H.; Adimalla, N.; Pei, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H. Co-occurrence of arsenic and fluoride in groundwater of Guide basin in China: Genesis, mobility and enrichment mechanism. Environ. Res. 2024, 244, 117920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymoorian, T.; Delon, L.; Munoz, G.; Sauvé, S. Target and Suspect Screening Reveal PFAS Exceeding European Union Guideline in Various Water Sources South of Lyon, France. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2025, 12, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-García, P.; Aljabasini, O.; Barata, C.; Gómez-Canela, C. Environmental risk assessment of pharmaceuticals in wastewaters and reclaimed water from catalan main river basins. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 175020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaskovski, B.; Petrović, M.; Kljajić, Z.; Degetto, S.; Stanković, S. Analysis of major, minor and trace elements in surface sediments by X-ray fluorescence spectrometry for assessment of possible contamination of Boka Kotorska Bay, Montenegro. Maced. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2014, 33, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addis, T.Z.; Adu, J.T.; Kumarasamy, M.; Demlie, M. Occurrence of Trace-Level Antibiotics in the Msunduzi River: An Investigation into South African Environmental Pollution. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abafe, O.A.; Lawal, M.A.; Chokwe, T.B. Non-targeted screening of emerging contaminants in South African surface and wastewater. Emerg. Contam. 2023, 9, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouda, M.; Kadadou, D.; Swaidan, B.; Al-Othman, A.; Al-Asheh, S.; Banat, F.; Hasan, S.W. Emerging contaminants in the water bodies of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA): A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangola, J.; Abagale, F.K.; Cobbina, S.J. A systematic review of pharmaceutical and personal care products as emerging contaminants in waters: The panorama of West Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 911, 168633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, J.L.; Boxall, A.B.A.; Kolpin, D.W.; Leung, K.M.Y.; Lai, R.W.S.; Galbán-Malagón, C.; Adell, A.D.; Mondon, J.; Metian, M.; Marchant, R.A.; et al. Pharmaceutical pollution of the world’s rivers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2113947119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdez-Carrillo, M.; Abrell, L.; Ramírez-Hernández, J.; Reyes-López, J.A.; Carreón-Diazconti, C. Pharmaceuticals as emerging contaminants in the aquatic environment of Latin America: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 44863–44891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, M.L.; Bila, D.M.; Fonseca, E.M.; Neto, J.A.B.; Moreira, L.B.; Cavalcante, R.M. Impacts of Rapid Development in a Subtropical Region of South America (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil): Insights from Emerging Contaminants Across Various Chemical Classes. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 237, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, G.F.; Drage, D.S.; Thompson, K.; Eaglesham, G.; Mueller, J.F. Emerging contaminants (pharmaceuticals, personal care products, a food additive and pesticides) in waters of Sydney estuary, Australia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 97, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Whelan, A.; Cannon, P.; Sheehan, M.; Reeves, L.; Antunes, E. Occurrence of emerging contaminants in biosolids in northern Queensland, Australia. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 330, 121786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alygizakis, N.; Ng, K.; Gkotsis, G.; Nika, M.-C.; Vasilatos, K.; Kostakis, M.; Oswald, P.; Savenko, O.; Utevsky, A.; Dykyi, E. Contaminants of emerging concern in Antarctica. J. Environ. Expo. Assess 2025, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglietto, M.; Mackeown, H.; Benedetti, B.; Scapuzzi, C.; Cossu, B.; Di Carro, M.; Magi, E. The anthropic impact on Antarctica: A biennial study on emerging contaminants’ occurrence. In Proceedings of the Atti del XXVIII Congresso, Milan, Italy, 26–30 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, A.; Ravi, K.; Tian, F.; Singh, B. Arsenic Contamination Needs Serious Attention: An Opinion and Global Scenario. Pollutants 2024, 4, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Céspedes, R.; Petrovic, M.; Raldúa, D.; Saura, Ú.; Piña, B.; Lacorte, S.; Viana, P.; Barceló, D. Integrated procedure for determination of endocrine-disrupting activity in surface waters and sediments by use of the biological technique recombinant yeast assay and chemical analysis by LC–ESI-MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2004, 378, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibi, C.; Liu, C.-H.; Anandan, S.; Wu, J.J. Recent Advances on Electrochemical Sensors for Detection of Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs). Molecules 2023, 28, 7916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Gao, X.; Zuo, Y. Research and Application of Water Treatment Technologies for Emerging Contaminants (ECs): A Pathway to Solving Water Environment Challenges. Water 2024, 16, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernova, E.; Russkikh, I.; Voyakina, E.; Zhakovskaya, Z. Occurrence of microcystins and anatoxin-a in eutrophic lakes of Saint Petersburg, Northwestern Russia. Oceanol. Hydrobiol. Stud. 2016, 45, 466–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateia, M.; Wei, H.; Andreescu, S. Sensors for Emerging Water Contaminants: Overcoming Roadblocks to Innovation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 2636–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, R.M.C.; Figueiredo, D.; Mesquita, E.; Charrua, S.; Costa, C.; Lourinho, R.; Rosa, M.J. Pilot-scale demonstration of advanced wastewater treatment for direct potable water reuse for beer production. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 372, 133419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrmos, E.; Sidiropoulos, V.; Bechtsis, D.; Stergiopoulos, F.; Aivazidou, E.; Vrakas, D.; Vezinias, P.; Vlahavas, I. An Intelligent Modular Water Monitoring IoT System for Real-Time Quantitative and Qualitative Measurements. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranwal, J.; Barse, B.; Gatto, G.; Broncova, G.; Kumar, A. Electrochemical Sensors and Their Applications: A Review. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudpour, M.; Karimzadeh, Z.; Ebrahimi, G.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi, J. Synergizing Functional Nanomaterials with Aptamers Based on Electrochemical Strategies for Pesticide Detection: Current Status and Perspectives. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2022, 52, 1818–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zhang, C.; Yan, W.; Guo, Y.; Shuang, S.; Dong, C.; Bi, Y. Design of a facile and label-free electrochemical aptasensor for detection of atrazine. Talanta 2019, 201, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, S.; Li, X.; Gao, H.; Yang, L.; Jiang, C. Design of microfluidic fluorescent sensor arrays for real-time and synchronously visualized detection of multi-component heavy metal ions. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 493, 152636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, P.; Hefner, C.; Martinez, B.; Henry, C.S. Microfluidics in environmental analysis: Advancements, challenges, and future prospects for rapid and efficient monitoring. Lab A Chip 2024, 24, 1175–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, S.; Giwa, A. Advances in real-time water quality monitoring using triboelectric nanosensors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 11134–11158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, H.K.; Choudhury, S.; Sabharwal, U. Nanobiosensors in the Prediction of Environmental Pollutants: Recent Advances and Challenges. In Plant-Microbe Interaction Under Xenobiotic Exposure; Roy, S., Mandal, V., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, N.; Sah, N.; Saxena, K.; Jain, U. A review on biosensor approaches for the detection of hazardous elements in water. Talanta Open 2025, 12, 100536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Guo, L.; Man, C.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X. Emerging biosensors integrated with microfluidic devices: A promising analytical tool for on-site detection of mycotoxins. npj Sci. Food 2025, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.C.; Gomes, N.O.; Calegaro, M.L.; Machado, S.A.S.; de Oliveira, T.V.; de Fátima Ferreira Soares, N.; Raymundo-Pereira, P.A. Sustainable plant-wearable sensors for on-site, rapid decentralized detection of pesticides toward precision agriculture and food safety. Biomater. Adv. 2023, 155, 213676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathoni, M.; Zaki, A.; Razak, F. Ultra-Sensitive Quantum Sensor for Detection of Pollutants in Water. J. Tecnol. Quantica 2024, 1, 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- EPA, U.S. Nutrient Sensor Action Challenge—Stage I Winners. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/innovation/nutrient-sensor-action-challenge-stage-i-winners (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Frincu, R.M. Artificial intelligence in water quality monitoring: A review of water quality assessment applications. Water Qual. Res. J. 2024, 60, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, A.; Aqlan, F.; Baidya, S. Drone-based digital twins for water quality monitoring: A systematic review. Digit. Twins Appl. 2024, 1, 131–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lu, G.; Wu, Z. Remote sensing technology in the construction of digital twin basins: Applications and prospects. Water 2023, 15, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dui, H.; Cao, T.; Wang, F. Digital twin-based resilience evaluation and intelligent strategies of smart urban water distribution networks for emergency management. Resilient Cities Struct. 2025, 4, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, S.; Kumar, K.S.; Kumar, T.A.; Ashok, V.; Julie, E.G. Blockchain architecture for intelligent water management system in smart cities. In Blockchain for Smart Cities; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, L.; Ning, R.; Yu, S.; Gao, N. Application of remote sensing technology in water quality monitoring: From traditional approaches to artificial intelligence. Water Res. 2024, 267, 122546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, X.; Lan, Z.; Guo, W. Hyperspectral remote sensing technology for water quality monitoring: Knowledge graph analysis and Frontier trend. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1133325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Dhiman, G.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, A.; Tselykh, A. An IoT and Blockchain-based approach for the smart water management system in agriculture. Expert Syst. 2023, 40, e12892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).