Abstract

This contribution presents a thermal analysis of a Hyundai i10 exposed to solar radiation and investigates the greenhouse effect, which causes the air temperature inside the parked car to rise well above the ambient temperature. Experimental measurements of the effects of customized window inserts on the temperature and heat absorption inside the car were carried out by thermal camera and thermal probes. The probes recorded the temperature at three locations inside the car—in the footwell of the rear seat, on the windscreen, and at the driver’s head height—on two consecutive days with similar weather conditions. The results show that the inserts effectively reduced heat build-up in the interior.

1. Introduction

The definition of energy is known in the literature as the body’s ability to do work. Due to the broad application of the term energy, it is sometimes difficult to understand the meaning of this important physical concept. Historically, the most famous physicists and scientists such as Leibnitz, Young, Helmholtz, and others have dealt with energy, and one of the first definitions, established at the beginning of the 19th century, was based on kinetic energy as we know it today [1].

Based on the concept of energy, a specific form that is particularly relevant in thermodynamics is thermal energy. The change in thermal energy that results in a temperature difference between two systems, as well as the transfer of this energy from the system with the higher temperature to the system with the lower temperature until thermal equilibrium is reached, is defined as heat [2]. The relationship between different forms of energy, such as thermal energy and heat, is governed by one of the fundamental principles of physics, the law of conservation of energy. This law states that the total energy in a closed system is conserved, which means that energy can neither be created nor destroyed but can only be converted from one form to another. In the context of heat transfer, thermal energy is not lost but redistributed between systems until thermal equilibrium is reached.

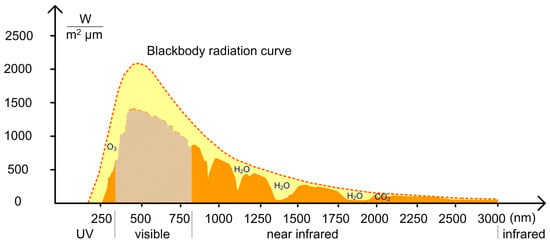

Solar radiation, which is electromagnetic in nature, reaches its peak in the visible part of the spectrum when it penetrates the atmosphere (see Figure 1) and then heats the Earth’s surface. Figure 1 shows the distributions of solar energy, with the peak in the visible range corresponding to the main portion of incoming radiation that warms the Earth’s surface. The longer wavelengths represent infrared radiation, which is partially absorbed and re-emitted by atmospheric gasses. Some of this radiation is radiated back into the atmosphere as infrared energy, where it is partially absorbed by carbon dioxide and water vapor molecules, while the rest is radiated back to the Earth’s surface and contributes to further warming. These energy transitions are summarized as the greenhouse effect [3]. In the case of a closed vehicle parked in the sun, solar radiation penetrates the atmosphere and heats the vehicle, absorbing and storing some of the energy. This leads to a significant increase in temperature inside the closed car. This situation serves as a simple illustration of the greenhouse effect, in which trapped solar energy causes a rise in temperature. The cabin of a parked car can be considered a closed system similar to a greenhouse, where visible light passes through the glass and warms the interior, while infrared energy remains trapped inside. On a larger scale, such processes are related to the Earth’s energy balance, a term that defines the flow of energy on Earth, including the energy coming in from the sun and the energy going out from the Earth’s surface [4]. When this balance is disturbed, the greenhouse effect intensifies and contributes to global warming. In this work, the undesirable effects of the greenhouse effect are addressed through the development of special inserts for the windshield and other car windows, supported by the ProStudent project [5]. The proposed inserts are designed to reduce the greenhouse effect by reflecting part of the solar radiation and lowering the overall heat load.

Figure 1.

The radiation spectrum of the Earth.

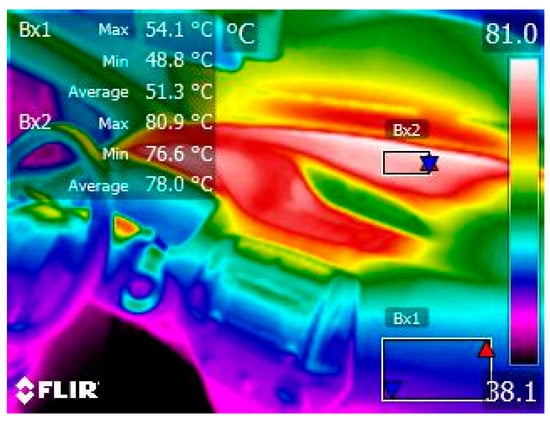

Solar radiation reaches the Earth’s surface and is absorbed, which leads to an increase in temperature. Conversely, the Earth radiates energy into the atmosphere, mainly in the form of infrared radiation, where some of this radiation is reflected and radiated back to the Earth’s surface [6]. These processes indicate that the Earth has the properties of a black body; a similar mechanism is observed in a closed vehicle parked in sunlight. When solar radiation penetrates the atmosphere and enters the vehicle, the components inside the vehicle, such as the seats, behave like black bodies, absorbing and storing solar energy. This leads to a significant increase in the vehicle’s interior temperature. In thermodynamics, an increase in the temperature of a system means that energy is being absorbed, while a decrease indicates that energy is being emitted. A black body absorbs and emits electromagnetic radiation across all wavelengths. The radiant power of a black body is defined by one of the fundamental laws of physics, the Stefan–Boltzmann law, which states that radiant power is proportional to the fourth power of temperature [7]. So, if you compare a system that resembles a black body, you can determine its radiant power. In this work, the observed closed system consists of a sealed car parked exposed to the sun’s rays. Figure 2 is a thermogram of the car’s control panel taken with a FLIR thermal imaging camera, model E6. The thermogram shows that the maximum temperature near the control panel is 81 °C. As the electromagnetic waves peak in the visible part of the spectrum, the car windows could be fully protected with inserts that have minimal absorption, essentially white bodies, the opposite of black bodies.

Figure 2.

Thermographic image of the car interior exposed to sunlight during summer day in Osječko-Baranjska County. Colors indicate the temperature distribution ranging from 38.1 °C (cooler colors) to 81 °C (warmer colors).

Thermal imaging technology has been widely explored for monitoring thermal comfort in vehicle cabins. Lyu et al. [8] used thermal imaging to develop a non-contact model for assessing thermal conditions inside a vehicle. Similarly, Román and Knoch [9] used a wide-angle infrared camera to capture the overall heat distribution within the vehicle interior for HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) system optimisation. Lyu et al. conducted field experiments in dynamic outdoor cabins to explore the correlation and synchrony between environmental factors and occupant thermal response, as well as to demonstrate the validation of IR-based comfort ratings in real-world conditions [10]. While these studies relied primarily on infrared imaging to obtain thermograms and assess thermal comfort, the present study takes a different approach.

In this study, air temperatures were recorded using three digital contact probes positioned inside the cabin. This method was chosen due to its high accuracy, stability, and suitability for capturing point thermal data in a confined space without visual analysis. When vehicles are exposed to sunlight for long periods of time, it can lead to extreme temperatures in the vehicles interiors, which not only accelerate the degradation of materials and electronic components but also significantly reduce thermal comfort for drivers and passengers. Solving this problem is important in maintaining vehicle functionality and comfort, especially during summer or in warm climate areas.

2. Materials and Methods

The heat absorbed by the body is proportional to the difference in body temperature, that is

where m is the mass of the body and c is the specific heat capacity of the substance. This fundamental relationship serves as the basis for analyzing the thermal processes that take place when vehicles overheat.

ΔQ = m c ΔT

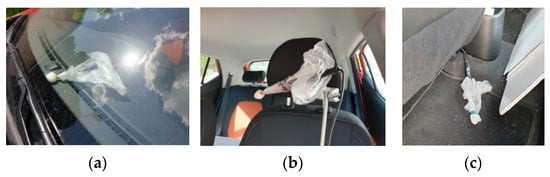

Based on the physical background described in the previous chapter, a simple solution to the problem of vehicle overheating due to the greenhouse effect [11] was presented. In practice, however, the effectiveness of such a solution depends largely on the choice of material. Not every material is suitable. Vehicles are often covered with white material through which electromagnetic waves easily penetrate. Therefore, the inserts for car windows proposed in the paper [11] were made of white forex sheets with a thickness of 3 mm and low mass. The inserts were cut according to the dimensions of the Hyundai i10 windows (Seoul, Republic of Korea), as shown in Figure 3. The inserts are intended specifically for cars parked in direct sunlight. They are not additionally coated and they do not require homologation. The inserts were placed on the windows after parking and removed before driving. Their purpose is to protect the car interior and electronic components, as well as to improve passenger comfort when entering a car that has been exposed to the sun.

Figure 3.

The inserts were customized to fit of all windows of the Hyundai i10.

In addition to the thermal efficiency of the materials used for the inserts, their recyclability in accordance with European Directive 2000/53/EC on end-of-life vehicles was also considered. In the automotive industry, the use of materials that can be reused and recycled is highly important. Paper [12] emphasized the need to replace difficult-to-recycle materials with more environmentally friendly solutions, integrating environmental criteria at the vehicle design stage. This covers the entire cycle, from production and use to end-of-life and recycling of materials. A similar principle is followed in this research, where the selection of materials is guided not only by the requirement to reduce thermal load but also by compliance with recycling requirements.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed inserts, measurements of the air temperature inside the car were carried out. Three digital temperature probes were used to measure the air temperature inside the car, the GTH 175/Pt Digital Thermometer Pt1000 −199.9…+199.9 °C from Greisinger Electronics. At the top end of the probe, where the sensor is located, it is wrapped in a damp pad to avoid direct contact with the material and introduce a systemic error into the measurement, as air and plastic have different specific heat capacities, which means that they have different temperatures when exposed to the same electromagnetic waves (until thermal equilibrium is reached). The sensor and the pad were wrapped in a PVC bag to prevent the evaporation of water, whose mass is negligible compared to the volume of the car interior. The measurement equipment and software used in the experiment are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The measurement equipment and software information.

The probes were placed at three points: Point A—on the dashboard, which is exposed to radiation the most due to the size and inclination of the windshield; Point B—near the driver’s head, where the heat affects driver’s comfort the most; Point C—at the base of the left passenger seat, which is least exposed to radiation in the entire car. Figure 4 shows the probe setup. The measurements were carried out in the interior of a Hyundai i10, model year 2014, with an interior volume of 252 L [13]. The measurements were carried out on 9th and 10th of May 2022 under very similar weather conditions (26 °C, sunny, cloudless) in a vehicle parked at the Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Computer Science and Information Technology Osijek, in Osijek. On 9 May, the measurements were carried out without window inserts, and with inserts on 10 May. In both cases, the car was parked in direct sunlight for two hours before the measurement, specifically from 13:00 to 15:00 pm. The air temperatures at three points in the interior were recorded using digital probes, with the readings extracted from the smartphone video footage in 2 min intervals. The car remained closed the entire time.

Figure 4.

Setup of Greisinger Electronic temperature probes used to measure the air temperature at three points in the car interior (in the figure, from left to right, points (a), (b), and (c)).

3. Results

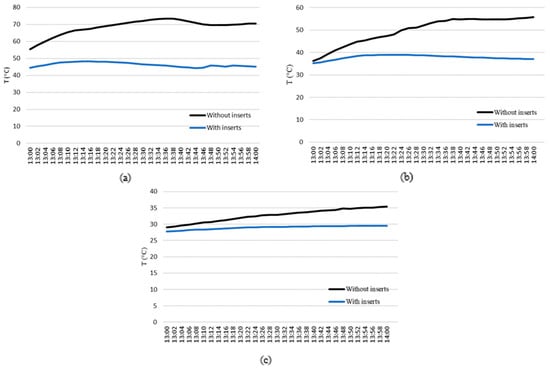

Figure 5 shows temperature variations inside the car at one-hour intervals, with black indicating temperatures without inserts and blue indicating temperatures with inserts. The second hour is omitted from the graphs for clarity, as the temperature increase during this period follows the same trend as in the first hour and does not provide new physical insights.

Figure 5.

Changes in the air temperature inside the car at the following points: (a) on the windshield, (b) on the driver’s head, and (c) at the foot of the rear seat.

The highest temperatures were recorded at the windshield, while the lowest were rescored near the floor. Specifically, the temperature at the windshield (point A) reached maximum of 70.6 °C without inserts, and 45.1 °C with inserts. Near the driver’s head (point B), the temperature reached maximum of 55.4 °C without inserts, and 37.1 °C with inserts. At point C, the temperature reached maximum of 35.4 °C without inserts, and 29.5 °C with inserts.

Table 2 shows the relative differences in the final temperatures at all three points for between two measurement cases (with and without inserts). After one hour of sunlight exposure, the temperature difference between exposed and shield car was about 36% at the windshield, whereas there was just about 16% temperature difference between these two cases at the point of footing.

Table 2.

Relative differences in the final temperatures without and with inserts at the three measuring points A, B, and C.

To determine the heat stored in the car, Equation (1) was applied, and the results are presented in Table 3. In Table 3, is the average initial air temperature without inserts and is the average final air temperature without inserts; is the average initial air temperature with inserts and is the average final air temperature with inserts. The interior volume V of the air in a Hyundai i10 is 252 L. The mass of air in the car was obtained from the interior volume V and the table value of air density. Although the air density changes with temperature, this effect can be neglected as the car remained closed during the measurements, meaning no air was lost into the environment. Finally, the heat absorbed by the air without and with inserts is labeled Q and Q′ in Table 3. After one hour, the air in the car absorbed 2901.8 J of heat, whereas with the inserts, it only absorbed 296.5 J, which corresponds to a reduction of 90.7%.

Table 3.

Average initial and final air temperatures and calculation of the absorbed heat without and with inserts.

4. Discussion

Due to optical properties of the glass and a black interior, the greenhouse effect occurs when the vehicle is exposed to sunlight. As a result, interior temperatures can reach up to 80 °C, posing a serious risk to the health and comfort of the driver and passengers.

To minimize the greenhouse effect, window inserts were made from thin white forex panels, which behave like a white body. Thermal analysis of the air trapped in the car interior was carried out to determine how these inserts affect heat build-up inside the car.

The temperature measurements with digital probes were carried out on two consecutive days from 13:00 to 15:00 at three locations within the car: near the windshield, near the driver’s head, and at the foot of the left rear seat. Ambiental conditions were the same on both days. On the first day measurements were performed without the inserts, whereas on the second day, inserts were applied to all car windows.

Results of probe testing revealed that the highest final temperature, 70.6 °C, was measured near the windshield without inserts. With inserts, the temperature at this point was 45.1 °C, which is 36.1% lower. The lowest final temperature was measured at the foot of the rear seat in both scenarios, 35.4 °C without inserts and 29.5 °C with inserts, a reduction of 16.7%. Near the driver’s head, the highest temperature reached 55.8 °C without inserts and 37.1 °C with inserts, which is a decrease of 33.5%.

The average initial and final temperatures were used to calculate the heat absorbed by the air. During one hour of solar radiation exposure, the air in the car absorbed 2901.8 J of heat without inserts, but only 296.5 J with inserts, which corresponds to a reduction of 90.7%.

The application of inserts on the car windows significantly lowered the thermal load, resulting in lower cabin temperatures, less heat stress, and reduced need for cooling via AC or vents. Given their simplicity, low cost, and effectiveness, such inserts offer a practical solution for reducing heat build-up in parked vehicles, especially during the summer.

However, future work should investigate improvement of their white body properties by applying a white coating of barium sulfate, an agent that is often used in passive cooling technologies. Furthermore, different vehicle types and a wider range of climatic conditions should be tested.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.B. and D.J.; methodology, D.J. and H.G.; validation, D.J., H.G. and R.G.; formal analysis, A.K.B. and D.J.; investigation, A.K.B. and D.J.; data curation, A.K.B. and D.J.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.B.; writing—review and editing, D.J., H.G. and R.G.; visualization, A.K.B. and D.J.; supervision, R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union–NextGenerationEU, under the project 581-UNIOS-38 “Optimizing the Operation of Electric Vehicles, Autonomous Vehicles, and Smart Mobility Systems”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Young, T.A. Course of Lectures on Natural Philosophy and the Mechanical Arts: In Two Volumes (Vol. 2), 1st ed.; Johnson: London, UK, 1807; pp. 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, D.; Resnick, R.; Walker, J. Fundamentals of Physics, 9th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2011; pp. 581–585. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T.R.; Hawkins, E.; Jones, P.D. CO2, the greenhouse effect and global warming: From the pioneering work of Arrhenius and Callendar to today’s Earth System Models. Endeavour 2016, 40, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shine, K.P.; Fuglestvedt, J.S.; Hailemariam, K.; Stuber, N. Alternatives to the global warming potential for comparing climate impacts of emissions of greenhouse gases. Clim. Change 2005, 68, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ProStudent FERIT. Available online: https://pro-student.ferit.hr/povijestprostudenta.php (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Ramanathan, V.; Vogelmann, A.M. Greenhouse effect, atmospheric solar absorption and the Earth’s radiation budget: From the Arrhenius-Langley era to the 1990s. Ambio 1997, 26, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- De Lima, J.A.S.; Santos, J. Generalized Stefan-Boltzmann Law. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 1995, 34, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Yang, Y.X.; Shi, Y.X.; Lian, Z.W. Application-driven development of a thermal imaging-based cabin occupant thermal sensation assessment model and its validation. Build. Simul. 2024, 17, 1401–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, P.; Knoch, E.-M. Wide-Angle Thermal Sensing for Personalized Climate Control in Vehicle Cabins. In IHSI 2025—Intelligent Human Systems Integration; Ahram, T., Karwowski, W., Eds.; AHFE International Open Access: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Volume 160, pp. 650–657. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, J.; Yang, Y.X.; Lai, D.Y.; Lan, L.; Lian, Z.W. Exploring the correlation and synchronicity between environmental factors and occupant thermal response in dynamic outdoor cabin environments. Build. Environ. 2024, 261, 111727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukić, D.; Glavaš, H.; Dukić, J.; Vulić, L. Ramifications of the Greenhouse Effect: A Closed Vehicle Example. In Proceedings of the Smart Systems and Technologies (SST), Osijek, Croatia, 19–21 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Milojević, S.; Pešić, R.; Lukić, J.; Taranović, D.; Skrucany, T.; Stojanović, B. Vehicles optimization regarding to requirements of recycling Example: Bus dashboard. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Scientific Conference—Research and Development of Mechanical Elements and Systems (IRMES 2019), Kragujevac, Serbia, 5–7 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Automobiledimensions. Available online: https://www.automobiledimension.com/model/hyundai/i10 (accessed on 12 February 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.