Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis-Supported Evaluation of Biowaste Anaerobic Digestion Options in Slovakia †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Produced electricity value, depending on installed power output: <500 kW: 152.36 EUR/MWh; for installed power between 500 and 1000 kW: 139.40 EUR/MWh; for >1 MW of installed power: 128.78 EUR/MWh [37];

- Average produced heat value: 12 EUR/MWh [38]; heat sale throughout the year is assumed as the plants are to be built in industrial areas;

- Average liquid digestate value of 5 EUR/t [39];

- Solid digestate pellets average value of 150 EUR/t [40].

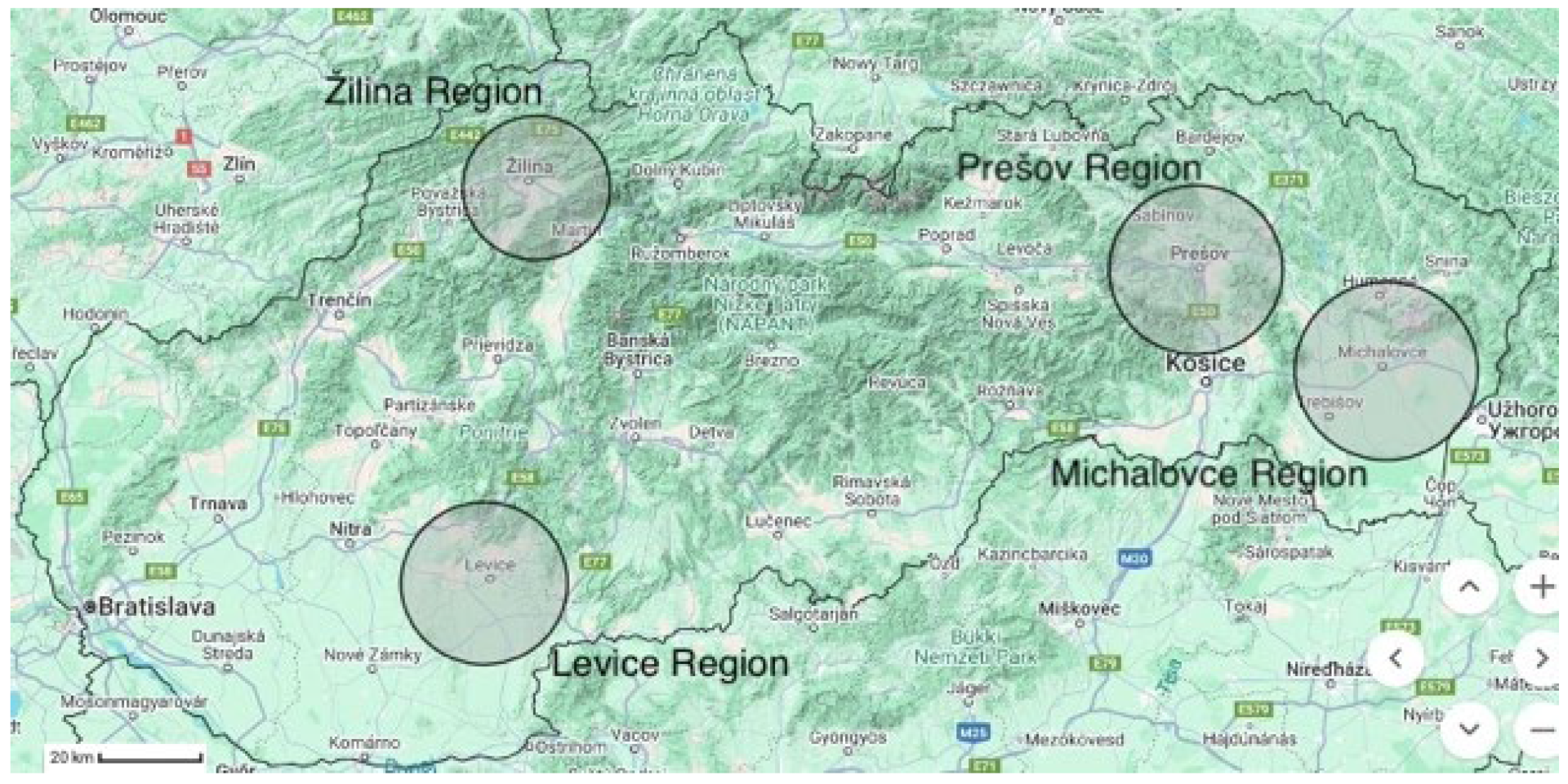

| Location | Potential Amount, t/Day | Reality (2021), t/Day |

|---|---|---|

| Žilina | 190.3 | 64.0 |

| Levice | 54.4 | 18.3 |

| Prešov | 146.9 | 49.4 |

| Michalovce | 140.7 | 47.3 |

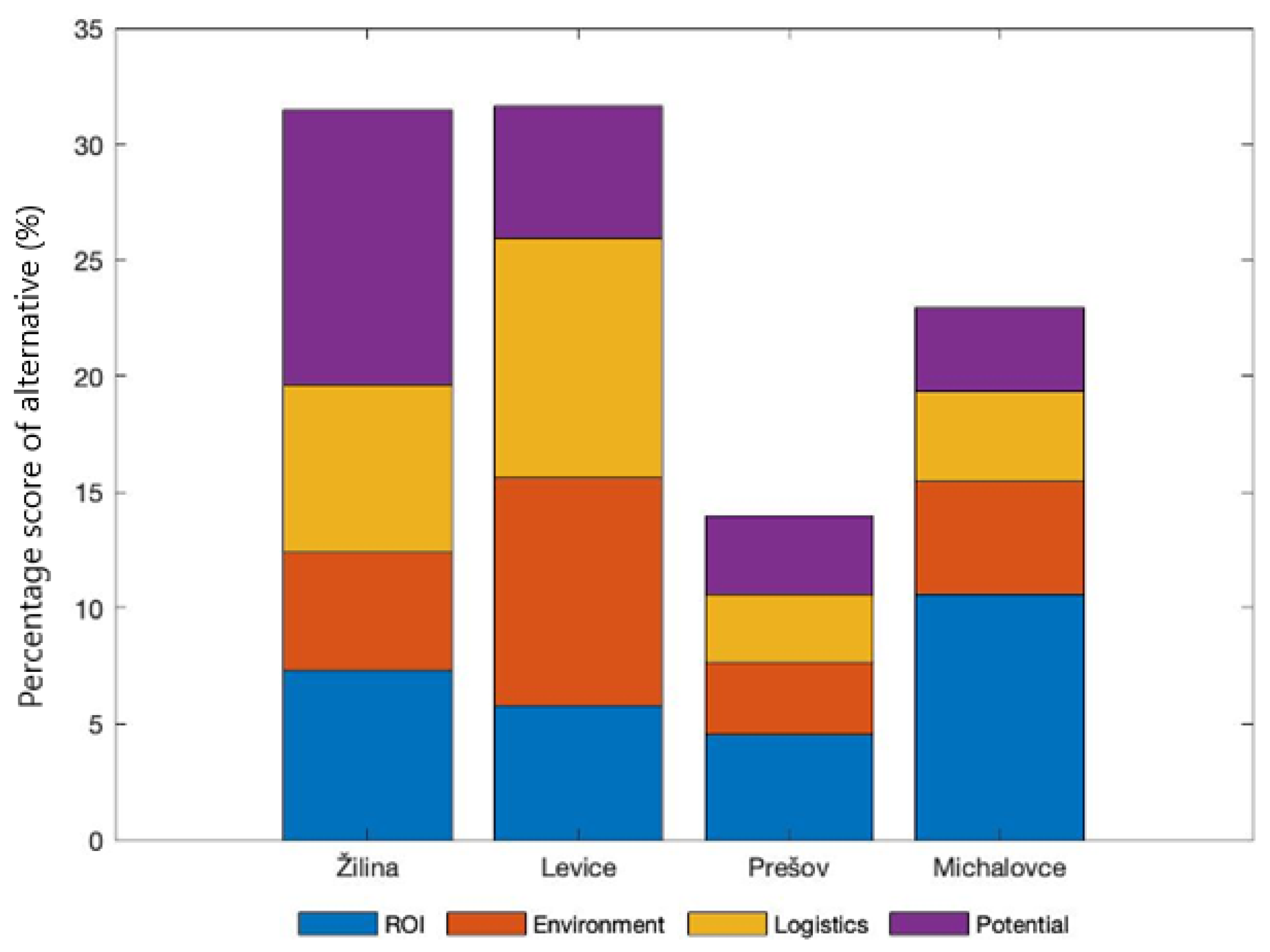

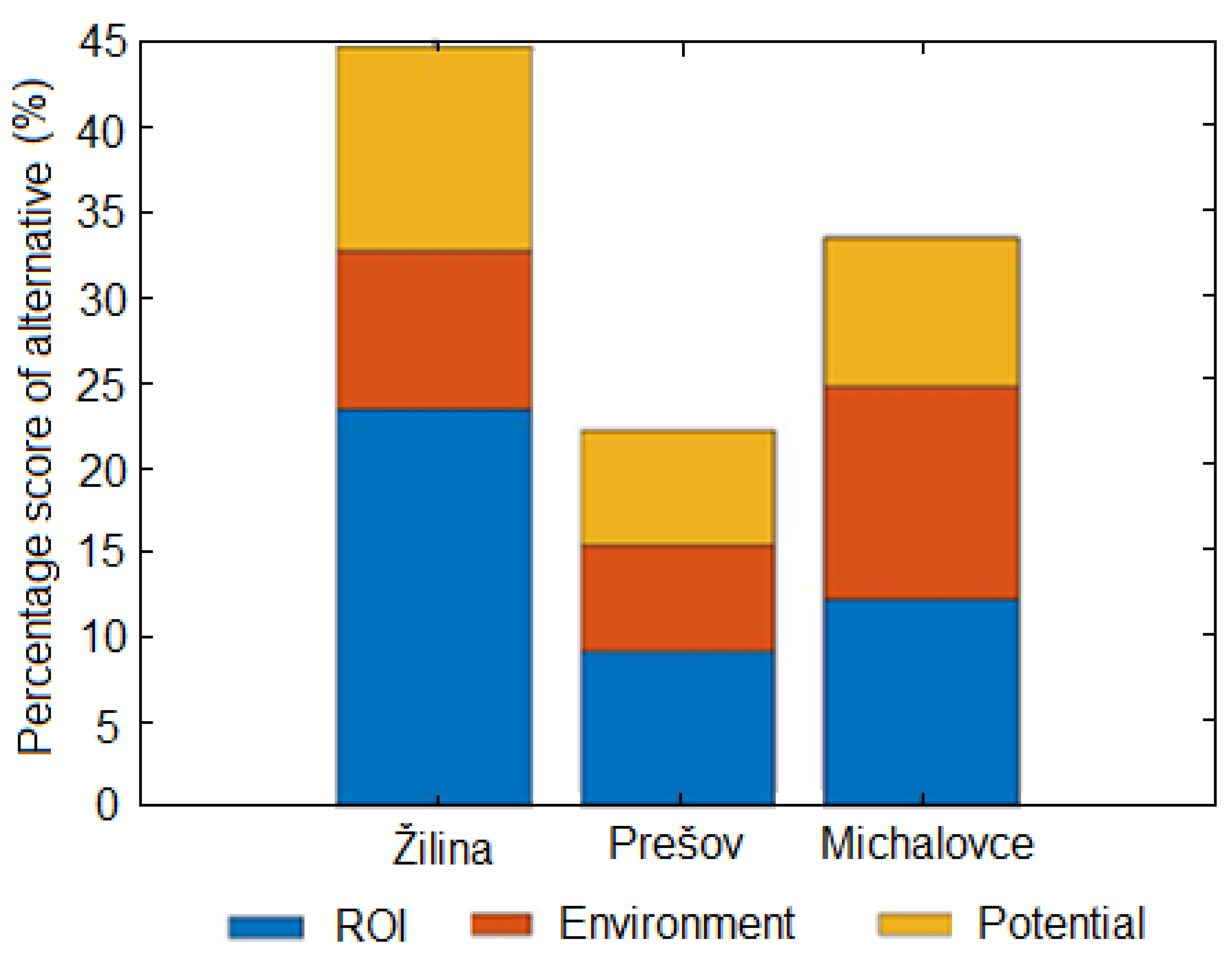

3. Results and Discussion

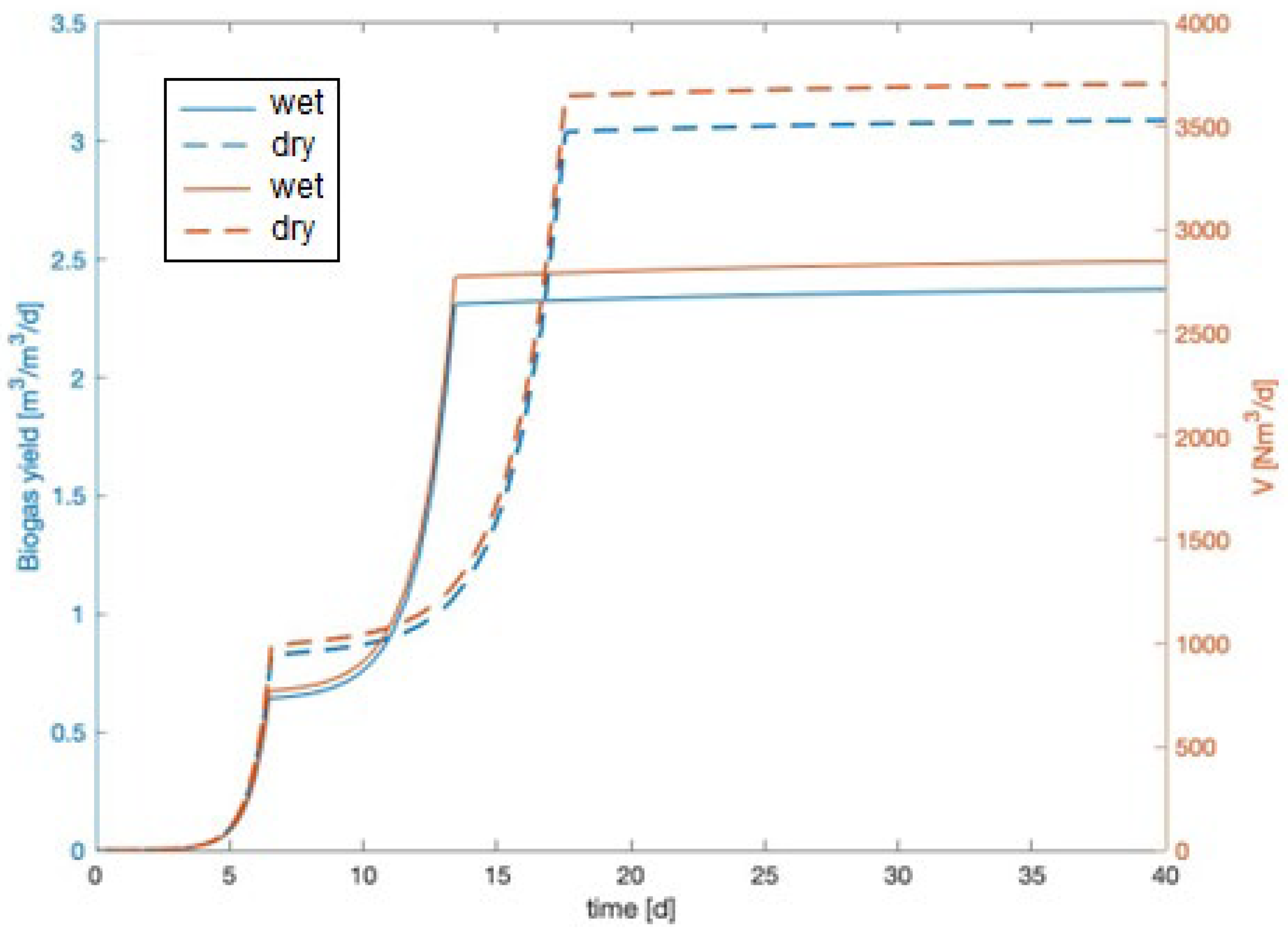

3.1. Anaerobic Digestion Modeling and Biogas Plants Assessment

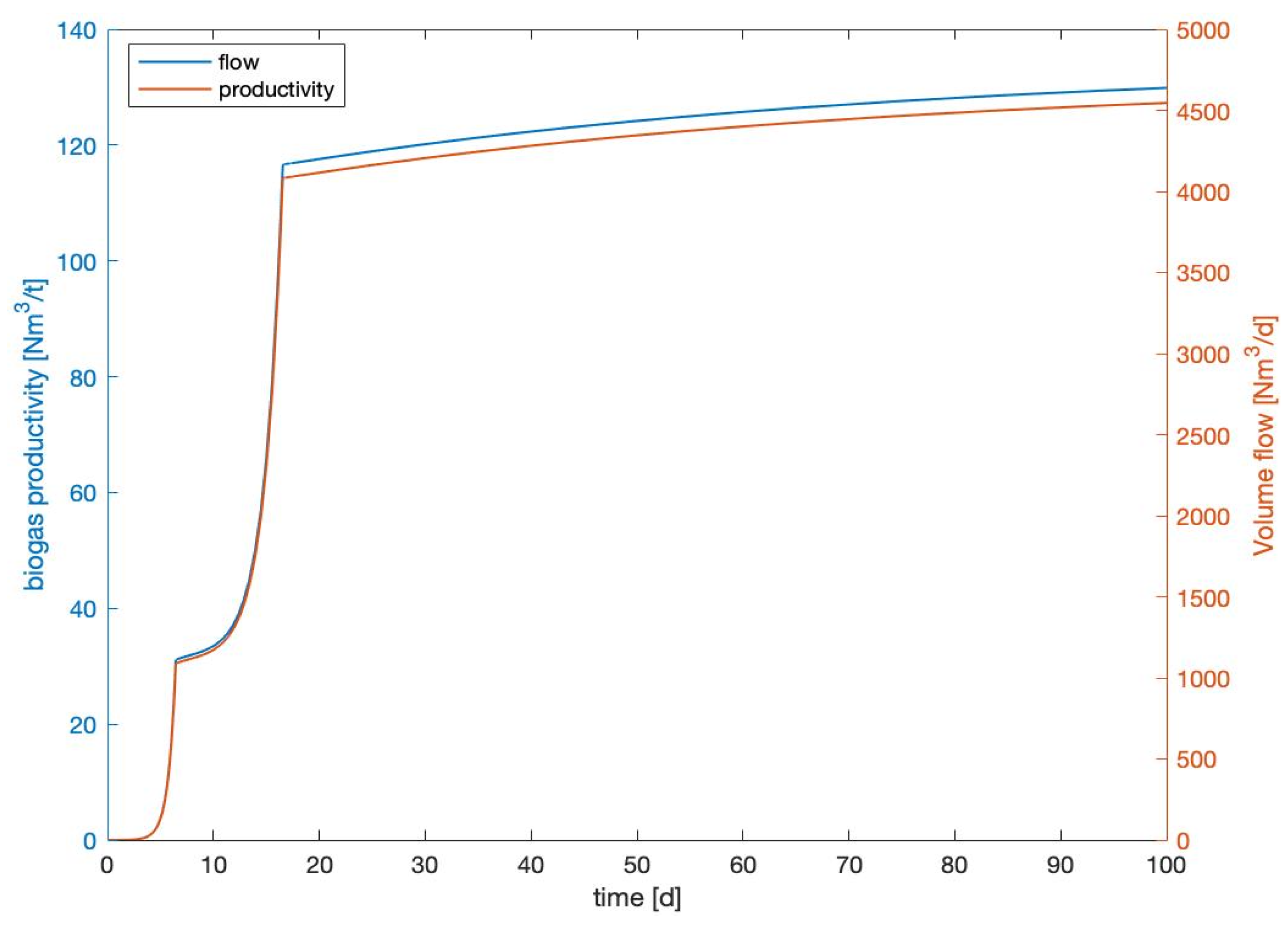

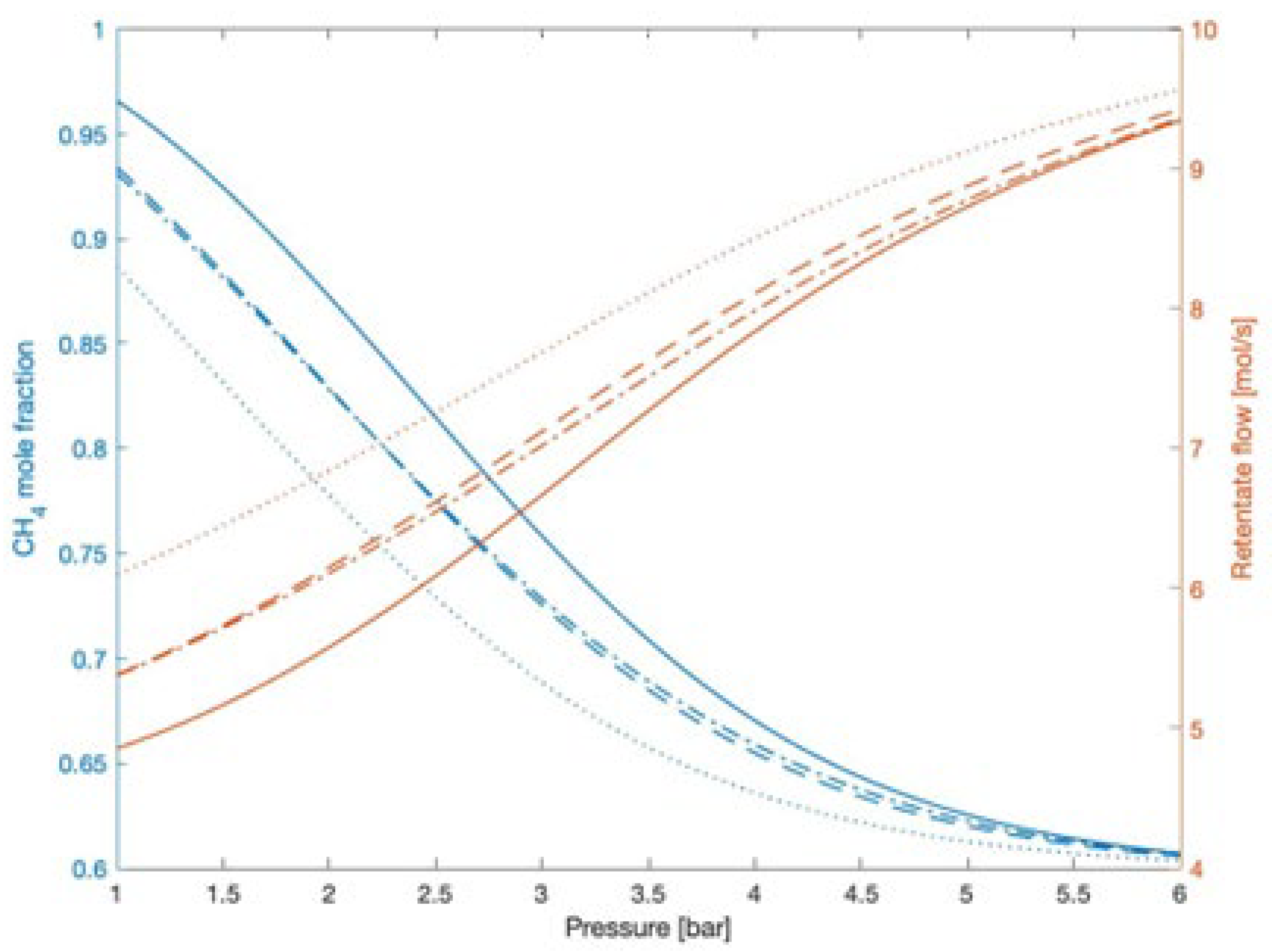

3.2. Biogas to Biomethane Upgrade and Biomethane Plants Assessment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Anaerobic digestion |

| ADM1 | Anaerobic digestion model one |

| AHP | Analytic hierarchy process |

| CSTR | Continuous stirred tank reactor |

| HRT | Hydraulic retention time |

| MCDA | Multi-criteria decision analysis |

| PFR | Plug-flow reactor |

| ROI | Return on investment |

| TS | Total solids |

| VS | Volatile solids |

| Xacetogenesis | Acetogenic bacteria concentration |

| Xacidogenesis | Acidogenic bacteria concentration |

| XmetaAC | Acetoclastic methanogens bacteria concentration |

| XmetaH2 | Hydrogenotrophic methanogens bacteria concentration |

References

- Wang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wu, G.; Zhan, X. A critical review on dry anaerobic digestion of organic waste: Characteristics, operational conditions, and improvement strategies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 176, 113208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsha Varthan, M.K.; Keerthana, V.; Saravanan, A.; Deivayanai, V.C.; Rejith Kumar, R.S.; Karunakaran Raveendran, S.; Tawfeeq Ahmed, Z.H.; Indumathi, S.M.; Prakash, P. Harnessing global biomass for bioenergy: Assessment techniques, technological advances, and environmental perspectives. Fuel 2026, 405, 136599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corigliano, O.; Iannuzzi, M.; Pellegrino, C.; D’Amico, F.; Pagnotta, L.; Fragiacomo, P. Enhancing Energy Processes and Facilities Redesign in an Anaerobic Digestion Plant for Biomethane Production. Energies 2023, 16, 5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Pera, A.; Sellaro, M.; Pellegrino, C.; Limonti, C.; Siciliano, A. Combined Pre-Treatment Technologies for Cleaning Biogas before Its Upgrading to Biomethane: An Italian Full-Scale Anaerobic Digester Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comparetti, A.; Ciulla, S.; Greco, C.; Santoro, F.; Orlando, S. State of the Art of Biomethane Production in the Mediterranean Region. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Mahari, W.A.W.; Li, G.; Yue, X.; Gu, H.; Peng, W.; Chen, X. Bioconversion of Biomass Waste Drives Sustainable Development. Eng. Sci. 2025, 37, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, A.; Akçay, S. A comprehensive analysis of a 250 kW biogas energy plant from energy, exergy, environmental and economical (4E) perspectives: Kastamonu case study. Biomass Bioenergy 2026, 207, 108762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birgani, A.G.; Assareh, E.; Ghafouri, A.; Jozaei, A.F. Innovative biomass cogeneration system for a zero energy school building. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelonidi, E.; Smith, S.R. A comparison of wet and dry anaerobic digestion processes for the treatment of municipal solid waste and food waste. Water Environ. J. 2015, 29, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achinas, S.; Achinas, V.; Euverink, G.J.W. A Technological Overview of Biogas Production from Biowaste. Engineering 2017, 3, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Shah, V.; Shilova, L.; Prajapati, P. A comprehensive review on post-treatment technologies for purification and enriching raw biogas. Biomass Bioenergy 2026, 207, 108710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinea, L.; Slopiecka, K.; Bartocci, P.; Alissa Park, A.-H.; Wang, S.; Jiang, D.; Fantozzi, F. Methane enrichment of biogas using carbon capture materials. Fuel 2023, 334, 126428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, L.; Imatoukene, N.; Lemaire, J.; Mounkaila, M.; Filali, R.; Lopez, M.; Theoleyre, M.-A. In-situ biogas upgrading by bio-methanation with an innovative membrane bioreactor combining sludge filtration and H2 injection. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 337, 125444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R.A. Simple Gas Permeation and Pervaporation Membrane Unit Operation Models for Process Simulators. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2002, 25, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusoh, N.; Hassan, T.N.A.T.; Suhaimi, N.H.; Mubashir, M. Hydrogen sulfide removal from biogas: An overview of technologies emphasizing membrane separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 373, 133466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczyński, S. Simulation of multi-stage membrane CH4/CO2 separation for upgrading biogas to grid injectable biomethane | Symulacja wielostopniowej separacji membranowej CH4/CO2 w uzdatnianiu biogazu do biometanu przeznaczonego do zatłaczania do sieci gazu ziemnego. Przem. Chem. 2025, 104, 918–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilloso, G.; Arpia, K.; Khan, M.; Sapico, Z.A.; Lopez, E.C.R. Recent Advances in Membrane Technologies for Biogas Upgrading. Eng. Proc. 2024, 67, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. Slovak Republic 2024. Energy Policy Review. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/d2f59c8b-1344-4b98-8a00-52ef074cfa06/Slovak_Republic_2024.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Liptáková, E.; Rimár, M.; Kizek, J.; Šefčíková, Z. The Evolution of Natural Gas Prices in EU Countries and Their Impact on the Country’s Macroeconomic Indicators. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2021, 31, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatayev, M.; Gaduš, J.; Lisiakiewicz, R. Creating pathways toward secure and climate neutral energy system through EnergyPLAN scenario model: The case of Slovak Republic. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 2525–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biomethane Plants. Available online: https://www.energie-portal.sk/Dokument/velke-bierovce-vyroba-biometanu-bioplynova-stanica-111582.aspx (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Ślusarz, G.; Twaróg, D.; Gołębiewska, B.; Cierpiał-Wolan, M.; Gołębiewski, J.; Plutecki, P. The Role of Biogas Potential in Building the Energy Independence of the Three Seas Initiative Countries. Energies 2023, 16, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencoova, B.; Grosos, R.; Gomory, M.; Bacova, K. Use of biogas plants on a national and international scale. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2021, 26, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimako, B.K.; Carpitella, S.; Menapace, A. Novel Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Based on Performance Indicators for Urban Energy System Planning. Energies 2024, 17, 5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, C.; Mesa Estrada, L.S.; Haase, M.; Tippe, M.; Wigger, H.; Brand-Daniels, U. MCDA for the sustainability assessment of energy technologies and systems: Identifying challenges and opportunities. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2025, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, F.; Rasheed, R.; Fatima, M.; Batool, F.; Nizami, A.-S. Sustainability Analysis of Commercial-Scale Biogas Plants in Pakistan vs. Germany: A Novel Analytic Hierarchy Process—SMARTER Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billig, E.; Thraen, D. Renewable methane—A technology evaluation by multi-criteria decision making from a European perspective. Energy 2017, 139, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llano, T.; Dosal, E.; Lindorfer, J.; Finger, D.C. Application of Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Tools for Assessing Biogas Plants: A Case Study in Reykjavik, Iceland. Water 2021, 13, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlken, A.; Wulf, K.; Grecksch, K.; Klenke, T.; Tsydenova, N. More Sustainable Bioenergy by Making Use of Regional Alternative Biomass? Sustainability 2020, 12, 7849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenarczyk, A.; Jaskólski, M.; Bućko, P. The Application of a Multi-Criteria Decision-Making for Indication of Directions of the Development of Renewable Energy Sources in the Context of Energy Policy. Energies 2022, 15, 9629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodkowska-Miszczuk, J.; Martinat, S.; Kulla, M.; Novotný, L. Renewables projects in peripheries: Determinants, challenges and perspectives of biogas plants—Insights from Central European countries. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2020, 7, 362–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belinska, S.; Bielik, P.; Adamičková, I.; Husárová, P.; Onyshko, S.; Belinska, Y. Assessment of Environmental and Economic-Financial Feasibility of Biogas Plants for Agricultural Waste Treatment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calise, F.; Cappiello, F.L.; D’Accadia, M.D.; Infante, A.; Vicidomini, M. Modeling of the Anaerobic Digestion of Organic Wastes: Integration of Heat Transfer and Biochemical Aspects. Energies 2020, 13, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calise, F.; Cappiello, L.; Cimmino, L.; Napolitano, M.; Vicidomini, M. Analysis of the Influence of Temperature on the Anaerobic Digestion Process in a Plug Flow Reactor. Thermo 2022, 2, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielič, M. Multifactorial Optimization of Biologically Degradable Waste Processing in Slovakia Emphasising Biomethane Production. Master’s Thesis, Slovak University of Technology, Bratislava, Slovakia, 2025. Available online: https://opac.crzp.sk/?fn=detailBiblioForm&sid=809C367C54749DCAA548A6FF7E5A (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Vrbová, K.; Ciahotný, K. Upgrading Biogas to Biomethane Using Membrane Separation. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 9393–9401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electricity Prices in Slovakia. Available online: https://www.zakonypreludi.sk/zz/2024-154 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Biogas and Biomethane Capital Costs. Available online: https://www.siea.sk/wp-content/uploads/poradenstvo/kontaktne_miesto/Kvantifikacia-energetickeho-potencialu-bioplynovych-stanic-SIEA.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Dahlin, J.; Herbes, C.; Nelles, M. Biogas digestate marketing: Qualitative insights into the supply side. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 104, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekała, W. Solid fraction of digestate from biogas plant as a material for pellets production. Energies 2021, 14, 5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natural Gas Prices. Burzové Ceny Elektriny a Plynu. Available online: https://www.okte.sk/sk/kratkodoby-trh/zverejnenie-udajov-dt/indexy-dt/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Gallovič, P.; Tóthová, A.; Sebíň, M.; Halász, L.; Chovanec, J.; Filák, R.; Šimková, Z.; Blaho, R.; Cehlár, M.; Sisol, M.; et al. Biela kniha Odpadového Hospodárstva v Slovenskej Republike. Údaje, Čísla, Fakty. Available online: https://www.zopsr.sk/storage/files/shares/analyzy/Biela_kniha_odpadoveho_hospodarstva_v_Slovenskej_republike.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Google Map Developers. Not associated with Google Maps. Available online: https://www.mapdevelopers.com (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Saaty, R.W. The analytic hierarchy process—What it is and how it is used. Math. Model. 1987, 9, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janošovský, J.; Boháčiková, V.; Kraviarová, D.; Variny, M. Multi-criteria decision analysis of steam reforming for hydrogen production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 263, 115722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraviarová, D. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis for Enhanced Decision-Making in Chemical Industry. Master’s Thesis, Slovak University of Technology, Bratislava, Slovakia, 2023. Available online: https://opac.crzp.sk/?fn=detailBiblioForm&sid=72C4190EA10FC8F711D500D508EF (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Biowaste Analysis. Odpadový Hospodár s.r.o, “ZOP_Analýza Triedeného Zberu BRKO na Slovensku_Odpadový Hospodár”, 2022. Available online: https://www.odpadovyhospodar.sk/analyza-zber-kuchynskych-odpadov-za-rok-2021/ (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Sun, Q.; Li, H.; Yan, J.; Liu, L.; Yu, Z.; Yu, X. Selection of appropriate biogas upgrading technology-a review of biogas cleaning, upgrading and utilization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 51, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutu, A.; Hernández-Shek, M.A.; Mottelet, S.; Guérin, S.; Rocher, V.; Pauss, A.; Ribeiro, T. A Coupling Model for Solid-State Anaerobic Digestion in Leach-Bed Reactors: Mobile-Immobile Water and Anaerobic Digestion Model. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 17, 100961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fdez-Güelfo, L.A.; Álvarez-Gallego, C.; Sales Márquez, D.; Romero García, L.I. Dry-Thermophilic Anaerobic Digestion of Simulated Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste: Process Modeling. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fdez-Güelfo, L.A.; Álvarez-Gallego, C.; Sales, D.; Romero García, L.I. Dry-Thermophilic Anaerobic Digestion of Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste: Methane Production Modeling. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biogas and Biomethane Emissions. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/SK/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02018L2001-20220607 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Al Mamun, M.R.; Torii, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Karim, M.R. Physico-chemical elimination of unwanted CO2, H2S and H2O fractions from biomethane. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2019, 3, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejčí, T.; Martinát, S.; Dvořák, P.; Kulla, M.; Klusáček, P.; Pícha, K.; Novotný, L.; Pregi, L.; Navrátil, J. Digesting the truth: The role of energy justice in perception of anaerobic digestion plants in Central Europe rural space. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 127, 104210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodkowska-Miszczuk, J.; Martinat, S.; Cowell, R. Community tensions, participation, and local development: Factors affecting the spatial embeddedness of anaerobic digestion in Poland and the Czech Republic. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 55, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvořák, P.; Krejčí, T.; Kulla, M.; Martinát, S.; Novotný, L.; Pregi, L.; Andráško, I.; Pícha, K.; Navrátil, J. Gains or losses of biogas: The point of view of inhabitants from Central and Eastern European perspective. Renew. Energy 2025, 252, 123493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Process | Component |

|---|---|

| Disintegration | Simple particulate organic matter represented by a mixture of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids |

| Hydrolysis | Composite particulate matter, which includes organic and inorganic materials in particulate form, is contained in waste and biomass |

| Acidogenesis | Particulate inert matter |

| Acetogenesis | Soluble organic inert matter |

| Acetoclastic methanogenesis | Soluble monomers, a mixture of sugars, amino acids, and long-chain fatty acids |

| Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis | Mixture of organic acids—propionate, butyrate, and valerate |

| Xacidogenesis Decay | Acetate |

| Xacetogenesis Decay | Methane |

| XmetaAC Decay | Hydrogen |

| XmetaH2 Decay | Acetogenic bacteria |

| Acidogenic bacteria | |

| Acetoclastic methanogens bacteria | |

| Hydrogenotrophic methanogens bacteria |

| Membrane | CH4 Permeability, Barrer | CO2 Permeability, Barrer |

|---|---|---|

| Polyimide | 0.25 | 10.7 |

| Cellulose acetate | 0.21 | 6.3 |

| Polycarbonate | 0.13 | 4.2 |

| Polysulfone | 0.25 | 5.6 |

| Technological Regime | Žilina, Nm3/d | Levice, Nm3/d | Prešov, Nm3/d | Michalovce, Nm3/d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry thermo. | 9380 | 2695 | 7248 | 6935 |

| Wet thermo. | 10,173 | 2909 | 7863 | 7521 |

| Continual thermo. | 11,380 | 3253 | 8766 | 8409 |

| Location | Membrane Area, m2 | Biomethane Flow Rate, Nm3/Year | Total Flow Rate, Nm3/Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Žilina | 2 modules á 13.5 | 1,062,231 | 1,094,098 |

| Levice | 2 modules á 2.5 | 299,226 | 308,801 |

| Prešov | 2 modules á 9.9 | 840,535 | 868,272 |

| Michalovce | 2 modules á 9.5 | 793,965 | 820,166 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Variny, M.; Danielič, M.; Polakovičová, D. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis-Supported Evaluation of Biowaste Anaerobic Digestion Options in Slovakia. Eng. Proc. 2025, 117, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117036

Variny M, Danielič M, Polakovičová D. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis-Supported Evaluation of Biowaste Anaerobic Digestion Options in Slovakia. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 117(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117036

Chicago/Turabian StyleVariny, Miroslav, Martin Danielič, and Dominika Polakovičová. 2025. "Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis-Supported Evaluation of Biowaste Anaerobic Digestion Options in Slovakia" Engineering Proceedings 117, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117036

APA StyleVariny, M., Danielič, M., & Polakovičová, D. (2025). Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis-Supported Evaluation of Biowaste Anaerobic Digestion Options in Slovakia. Engineering Proceedings, 117(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117036