Abstract

The D1 Paskov spoil heap is a smaller brownfield covering an area of 71,188 m2, located in the former Paskov mining region. It serves as a model area for reclamation planning, based on a comprehensive assessment of its natural conditions and the risks posed by contamination from hazardous elements and erosion processes. Data for this assessment was collected through field research conducted between 2023 and 2025. In September 2023, additional fieldwork and mapping were carried out using unmanned aerial vehicles equipped with two types of sensors: an RGB camera and LiDAR. The dump is primarily covered with ruderal vegetation, with the summit plateau dominated by the expansive grass species Calamagrostis epigejos. With appropriate management, the plant communities on the western and northern slopes have the potential to develop into conservation-significant habitats. However, the southwestern slope presents challenges due to active rill erosion and contamination. Stabilization measures are required to prevent further degradation in this area.

1. Introduction

Spoil heaps, remnants of deep coal mining, are prominent and ecologically significant features of the Ostrava landscape. They represent a new type of anthropogenic landform that influences the structure, function, and dynamics of local ecosystems.

This study focuses on the D1 Paskov spoil heap, located near the Ostravice River and adjacent to the Řepiště spoil heap. The site, covering an area of 71,188 m2, is owned by the state enterprise DIAMO and lies within a designated mining area at coordinates Y: 470611.47, X: 1111225.08. It is classified as a protected mineral deposit zone.

The D1 spoil heap can be divided into two principal zones:

- Summit plateau--the uppermost area, partially reclaimed with herbaceous vegetation and scattered trees. Noticeable substrate waterlogging occurs here.

- Heap slopes-encompassing northern, southern, eastern, and western slopes, each exhibiting different site conditions. These areas are largely unreclaimed and include significant erosion features, particularly on the southern slope.

In modern reclamation practice, special emphasis is placed on soil and topographic conditions, which influence erosion, nutrient availability, and the success of biological reclamation, including both managed and spontaneous succession [1,2]. Moreover, the role of ruderal vegetation as a primary colonizer of degraded areas is gaining increasing importance in reclamation planning [3].

The objective of this study is to conduct a comprehensive assessment of the spoil heap, focusing on nutrient availability, concentrations of selected risk elements, soil erosion, and vegetation functions.

2. Material and Methods

The reclamation potential of the D1 spoil heap was assessed using three main criteria:

- Soil chemical and physical properties;

- Vegetation composition and structure;

- Erosion assessment.

2.1. Soil Sampling and Analysis

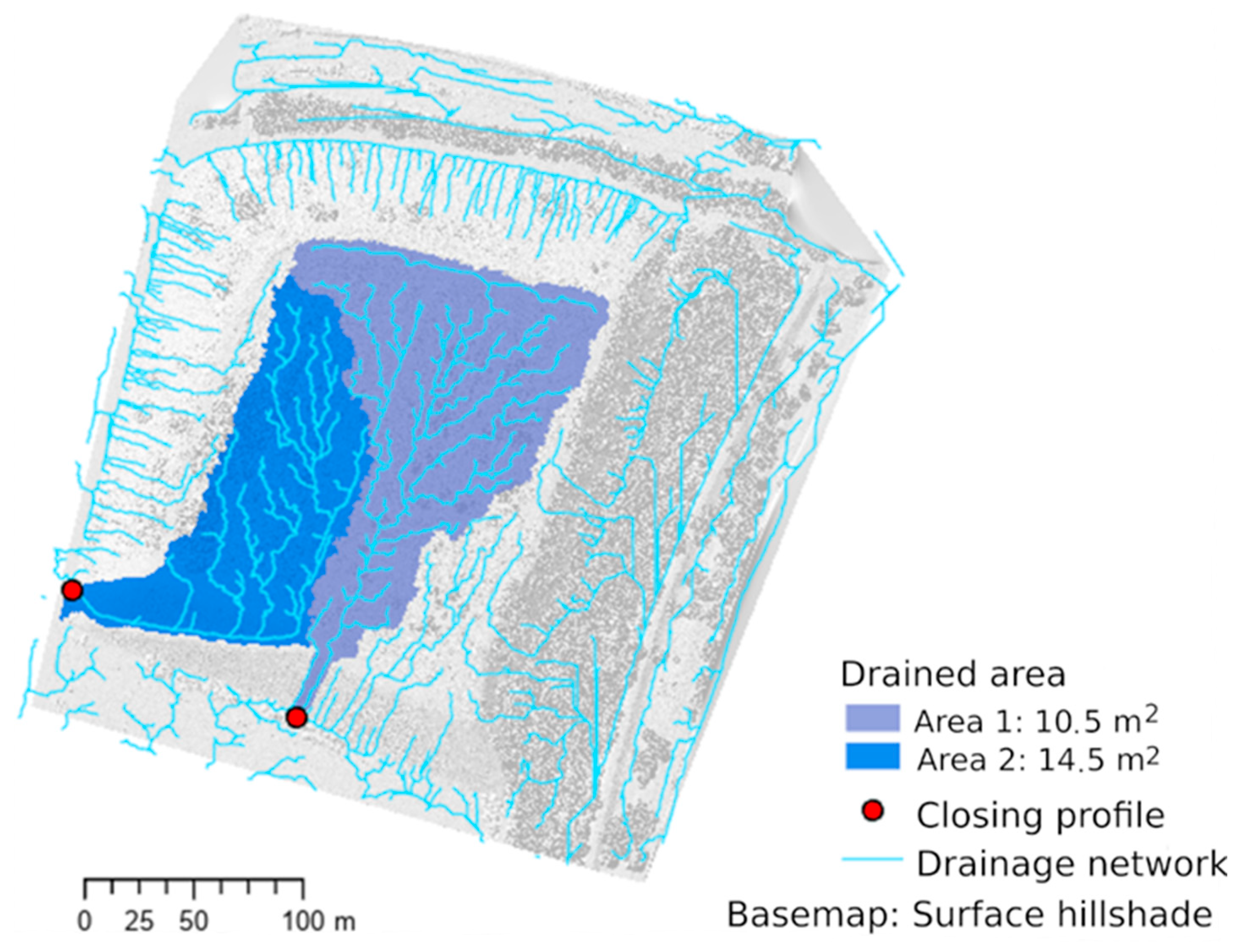

Soil samples were collected using a 50 × 50 m grid (see Figure 1). In autumn 2023, two composite topsoil samples (10–15 cm depth) were collected from 5 to 6 points per quadrant. Each composite weighed approximately 500 g and 200 g, respectively. Sampling was not conducted in quadrants A2, A3, A4, A5, or B1 (outside the area of interest); B7, C6, C7, D6, E6, or F5 (surface composed entirely of coarse spoil on very steep slopes); or D5, E4, or F4 (waterlogged areas with ponds). In quadrants with visually heterogeneous soils (C2, D1, E1, and G4), multiple composite samples were taken.

Figure 1.

Raster of D1 heap.

Nutrient analysis (S, Ca, Mg, K, C, P) was conducted using the Mehlich III method. Total nitrogen was determined via titration, and TOC was measured using infrared spectrometry. Risk element concentrations (Cr, Zn, Pb) were analyzed using atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) at the VŠB-TUO laboratory. Additional measurements-pH using KCl—were obtained from the spring 2024 samples.

Nutrient content was evaluated according to Decree No. 275/1998 Coll [4], and based on Mühlbachová et al., Smatanová, and Kulhánek et al. [5,6,7]. Risk elements were assessed according to the Methodological Guideline of the Ministry of the Environment: Pollution Indicators [8].

2.2. Vegetation Assessment

A floristic inventory of vascular plants was conducted during the 2022 and 2023 growing seasons. Phytosociological surveys were carried out along slope transects, each divided into upper, middle, and lower sections, 2 m wide. Six 100 m2 phytosociological relevés were established on the summit plateau. Data collection followed the Zurich–Montpellier approach [9], and habitat types were classified according to the National Catalogue of Habitats [10].

A digital vegetation model was created using UAVs, generating an orthophoto (2 cm/pixel) and both surface and terrain models (10–15 cm/pixel), processed in ArcGIS Pro, version 3.3 [11].

2.3. Erosion Assessment

UAVs equipped with RGB and LiDAR sensors were used in September 2023 to map slope geometry and identify erosion gullies. Erosion risk was assessed using the Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE), based on the methodology outlined in Protection of Agricultural Soil Against Erosion [12]. Terrain slope, gully presence, and surface runoff dynamics were evaluated.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Chemical and Physical Properties

A total of 28 composite sample pairs were analyzed. Summary statistics for nutrients and risk elements are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Nutrients and risk elements content.

The lowest nutrient levels were found on the northwest slope—C1 and C2b (P), D1 (S), E1b (C); the southeast slope—F2 (N), G4c (Ca); the northern slope—B3 (Mg); and the summit plateau—C5 (K).

The highest nutrient levels were recorded on the summit plateau—C4 (N, C); northeast slope—D1a (K, P); southwest slope—F2 (Ca, Mg); and northern slope—B5 (S).

Minimum risk element concentrations were detected on the southwest slope—F1 (Pb), G3 (Cr); and northwest slope—D1b (Zn).

Maximum values were found on the southwest slope—F3 (Cr); and southeast slope—G5 (Pb, Zn).

Soil pH ranged from 5.701 (F2) to 7.789 (D5), with a mean of 6.782 ± 0.699.

3.2. Erosion Assessment

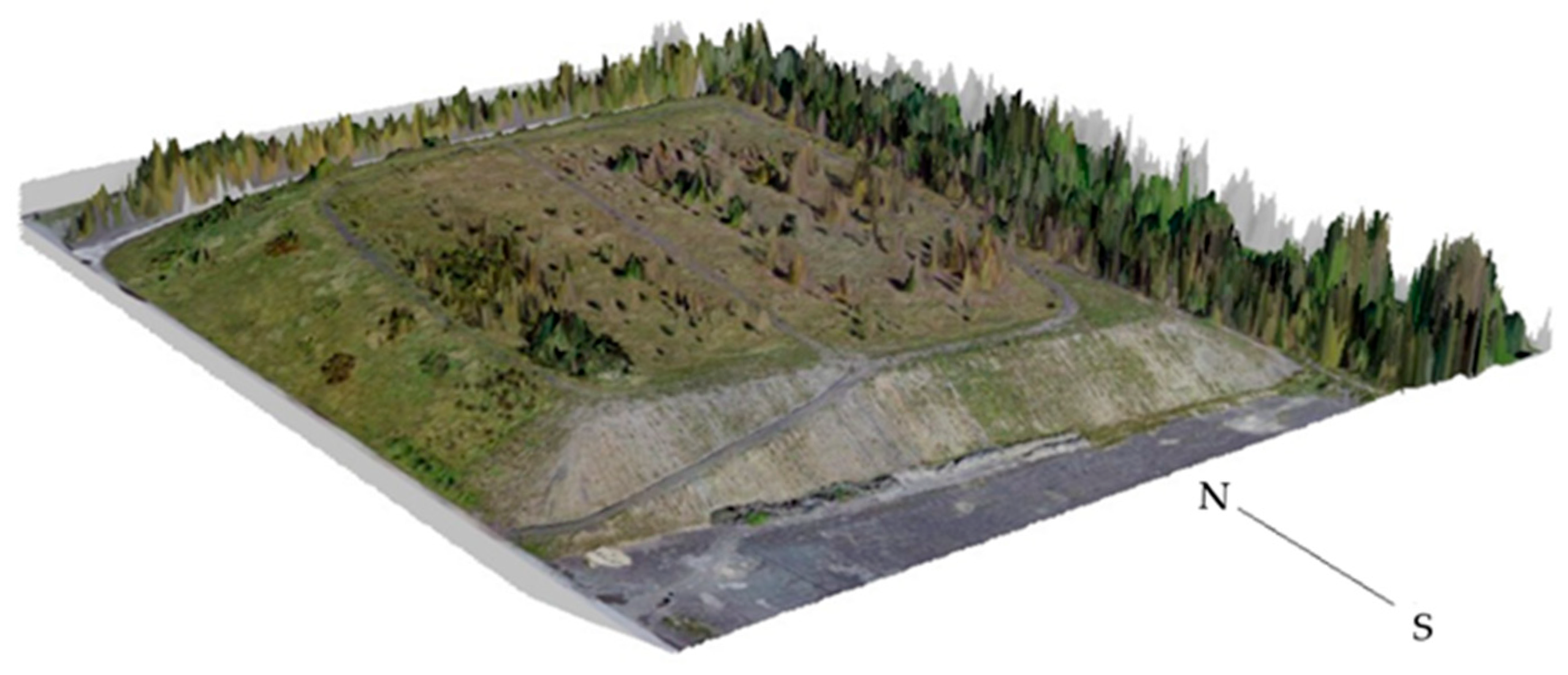

The terrain slope varies from 0° to 5°, with steep segments reaching 32–62° (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Terrain and slope of the Paskov heap D1.

3.2.1. Gully Erosion and Erosion Risk

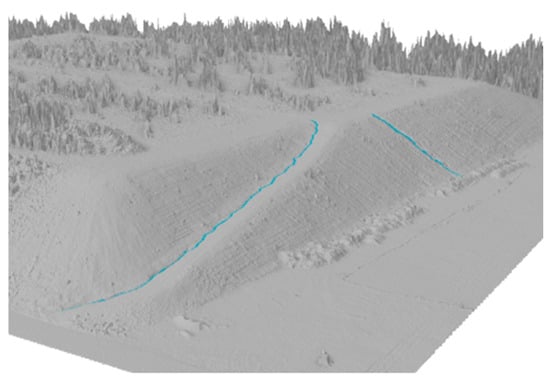

Two primary erosion gullies were documented on the southern slope (Figure 3), and their properties were established from imaging:

Figure 3.

Visualization of the two largest erosion grooves.

- First gully (SW slope, along access road):

Length: 118 m, avg. depth: 24.3 cm, max. depth: 48 cm, width: 0.63–1.96 m, avg. slope: 14.1%.

- Second gully (middle southern slope):

Length: 33 m, depth: 5–48 cm, width: 0.8–1.68 m.

Erosion risk was calculated for agricultural soils, as the spoil heap is intended to serve as permanent grassland and as an area for experimental grapevine cultivation. Soil loss was estimated at ~9 t/ha/year, within acceptable limits for agricultural land, although smaller gullies were excluded due to instability.

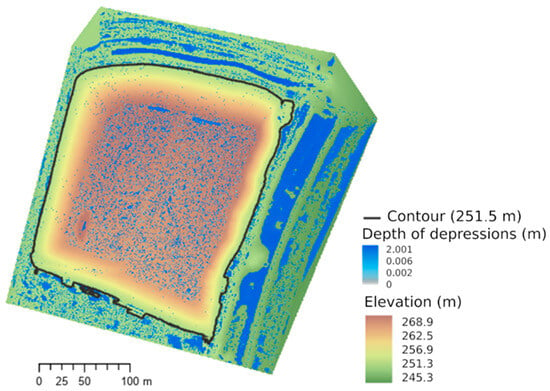

3.2.2. Surface Runoff

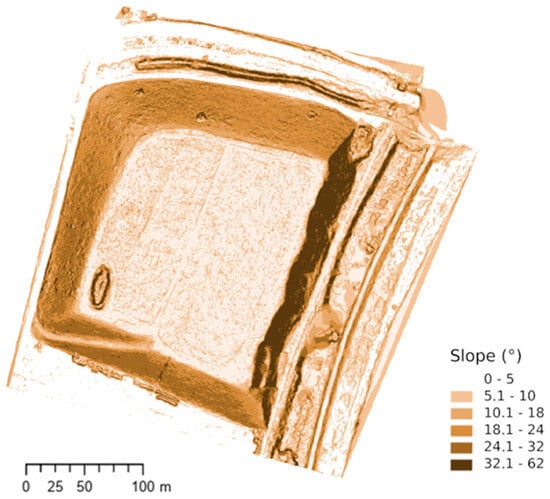

Water is drained from the entire spoil heap area (see Figure 4). The summit area enables ponding and wetland creation in closed depressions.

Figure 4.

Occurrence of small (including potential) wetlands and small pools.

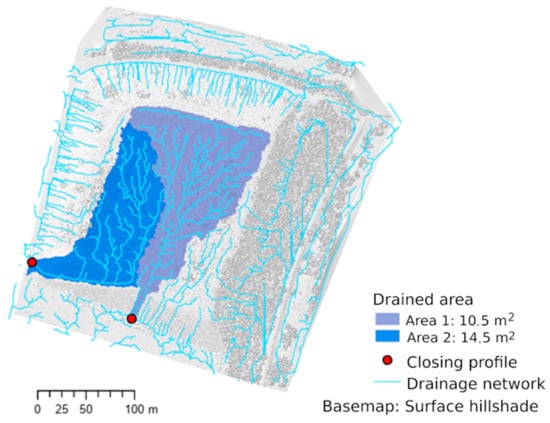

Discharge profiles were selected at the largest gullies (red dots in Figure 5). In the north, runoff is diverted via ruts formed by vehicle tracks that run along the perimeter of the upper platform.

Figure 5.

Drained area of spoil heap. Red dots: closing profiles; light blue area 1: drained area (10.505 m2); dark blue area 2: drained area (14.506 m2).

3.3. Vegetation and Habitat Assessment

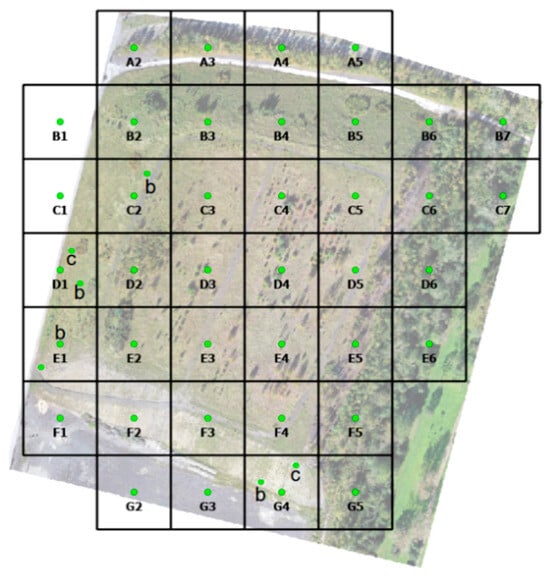

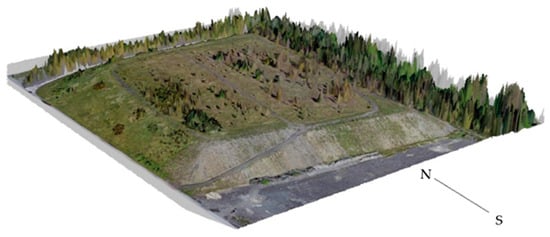

The digital surface model including existing vegetation and habitats is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Digital model of vegetation and biotopes.

A total of 107 plant species were recorded. No protected or endangered species were found. Invasive neophytes included Solidago canadensis, Erigeron annuus, Conyza canadensis, Negundo aceroides, and Populus × canadensis. Expansive natives included Calamagrostis epigejos, Cirsium vulgare, Arrhenatherum elatius, and Fraxinus excelsior.

The spoil heap was divided into five distinct areas for vegetation surveys:

- Summit plateau:

Habitat types-X6 anthropogenic areas with sporadic vegetation outside settlements, X7 ruderal herbaceous vegetation outside settlements, X12 pioneer woody vegetation colonization.

Dominated by Calamagrostis epigejos (up to 75%), often co-dominant with Solidago canadensis. About 30% of the plateau is overgrown with young spontaneous vegetation, mainly limes (Tilia cordata, T. platyphyllos), aspen (Populus tremula), and silver birch (Betula pendula).

- 2.

- Southern slope:

Habitat types: X6 anthropogenic areas with sporadic vegetation outside settlements, X7 ruderal herbaceous vegetation outside settlements, X12 pioneer woody vegetation colonization.

Highly eroded with sparse vegetation. Top of the slope sporadically overgrown with juvenile trees (Betula pendula, Populus tremula, and P. xcanadensis). The lower part of the slope is dominated by Calamagrostis epigejos. The base of the slope is bordered by a substrate embankment adjacent to the fence of a local industrial site.

- 3.

- Northern slope:

Habitat types: X7 ruderal herbaceous vegetation outside settlements.

Mesophilic grassland with shrubs (Rosa canina, Rubus fruticosus, Cornus sanguinea, and Lonicera xylosteum), reclamation plantings (Ligustrum vulgare, Cornus alba, and Viburnum opulus), and trees (juvenile Fraxinus excelsior, invasive Negundo aceroides, occasionally Betula pendula, and Populus tremula). Calamagrostis epigejos is dominant in upper areas (up to 80% cover).

- 4.

- Western slope:

Habitat types: X7 ruderal herbaceous vegetation outside settlements (likely developing into X7A-conservation-significant ruderal vegetation).

Relatively species-rich mesophilic grasslands with meadow phytocoenosis elements (Potentilla erecta, Symphytum officinale, Hypochaeris radicata, Agrimonia eupatoria, Silene nutans, Galium album, Pastinaca sativa, and Silene chalcedonia). Vegetation includes common shrubs (Swida sanguinea, Rosa canina, Rubus fruticosus, and Ligustrum vulgare). Quercus robur and Acer campestre are present in the middle and lower parts of the slope. Calamagrostis epigejos is also common but with a maximum cover of 25%.

- 5.

- Eastern slope:

Habitat types: X12 pioneer woody vegetation colonization (potentially developing into X12A-conservation-significant stands).

Ruderal forest type transitioning to riparian vegetation. Dominated by pioneer trees (Betula pendula, Populus tremula, Alnus glutinosa, juvenile Fraxinus excelsior, and invasive Populus xcanadensis), scree forests trees (Acer pseudoplatanus, A. platanoides, and Tilia cordata), shrubs (Rosa canina, Salix caprea, and Sambucus nigra), sparse understory with ruderal species (Picris hieracioides, Tanacetum vulgare, T. parthenium, Fragaria vesca, and Solidago canadensis), and grasses (Calamagrostis epigejos and Poa nemoralis).

4. Discussion

Effective reclamation requires alignment with ecological restoration principles [13]. Vegetation plays a crucial role in reducing erosion and enhancing nutrient cycling [1,3].

The spoil substrate is mineral-rich due to its Carboniferous origin [14] but suffers from low humus and nitrogen. These deficits can be addressed through plant succession, nitrogen-fixing species, or topsoil application [2,15].

The calcium content is ~27× higher than the regional average (157 mg/kg) [16], likely due to construction debris. Pertile et al. [16] report that construction waste can contain up to 27% Ca; in their study, Ca made up 0.68% of spoil material in the Ostrava-Karviná Coal Basin. The highest calcium content was recorded in the southern part of the spoil heap, where intensive water erosion also affects the waste. This part also showed the highest soil pH (7.79) and the highest magnesium content. The southern slope also showed the highest chromium content. According to the methodological guideline [5], the limit for Cr6+ is 0.29 mg.kg−1 for non-agricultural areas. Our analysis measured total Cr across all oxidation states. In nature, chromium most commonly occurs as Cr0, Cr2+, and Cr6+. Cr3+ is the naturally dominant, less mobile form and is typically reduced from Cr6+ in soils. The sparse vegetation on the southern slope lacks calciphilous species due to extreme conditions (slope, erosion, and lack of fine soil).

The highest sulfur content was recorded in the central part of the northern slope. (85–250 mg.kg−1) [17]. This is due to spoil rocks containing sulfides. However, the high sulfur content does not result in low soil pH, likely due to elevated Ca levels from construction debris. No significant water erosion was observed on the northern slope. The vegetation is herbaceous with occasional fruit-bearing shrubs.

On the heavier soils of the western slope, very high potassium and phosphorus levels were found, but phosphorus content is generally low; supplementation will be necessary for grapevine cultivation on the southern slope. The K/Mg ratio (0.58) remains within agronomic limits [6]. The western slope is not threatened by erosion due to relatively rich and continuous vegetation, including basiphilic mesotrophs.

The eastern slope has the character of a ruderal forest. In the SE part, the highest lead and zinc concentrations were measured, but the measured values are below the limits set by the guideline [8]. However, compared to typical arable soils (average 5.6 mg.kg−1) [3], these are high values.

The summit plateau is characterized by an almost monodominant stand of Calamagrostis epigejos, which produces a substantial amount of biomass. The soil is waterlogged, with frequent small ponds and pools, many of which remain at least slightly saturated even in late summer. These create interesting wetland habitats with moisture-loving vegetation. Due to the large amount of plant debris and slow biomass mineralization in the wet environment, the highest carbon and nitrogen contents were likely measured here. The average C/N ratio is 21.9%, indicating higher nitrogen immobilization, especially in the waterlogged parts of the heap [6].

5. Conclusions

The analysis of the Paskov D1 spoil heap exhibits significant heterogeneity in nutrient content, contamination, erosion, and vegetation, especially on the slopes, where more intense soil and water movement occurs.

From an erosion perspective, the southern slope is the most vulnerable, with two prominent erosion gullies. Although soil loss calculated using the USLE model falls within acceptable limits, the substrate’s heterogeneity warrants cautious interpretation and should be supplemented with direct measurements. The western and northern slopes are stabilized by continuous vegetation.

The expansive grass Calamagrostis epigejos is critical for sustainable restoration and requires long-term monitoring.

The summit plateau is characterized by a waterlogged environment with the presence of hygrophylous vegetation.

Overall, it can be concluded that the Paskov D1 spoil heap has potential for ecological restoration and agricultural use, particularly as permanent grassland and for extensive grapevine cultivation. However, successful reclamation will require targeted nutrient management, erosion control, and monitoring and control of expansive and invasive plant species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Š., B.S.; methodology, H.Š., P.P., B.S.; investigation, H.Š., P.P., B.S., J.N., K.R., M.K.; formal analysis, H.Š., K.R.; data curation, H.Š., P.P., K.R., M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Š.; writing—review and editing, H.Š., P.P., B.S.; visualization, K.R., M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project LIFE20 IPC/CZ/000004 OP LIFE for Coal Mining Landscape Adaptation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Plohák, P.; Švehláková, H.; Svozilíková Krakovská, A.; Turčová, B.; Stalmachová, B. Impact of Chromium, Arsenic and Selected Environmental Variables on the Vegetation and Soil Seed Bank of Subsidence Basins. Carpath. J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 17, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, A. Restoration of Mined Lands—Using Natural Processes. Ecol. Eng. 1997, 8, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranđelović, D.; Jakovljević, K.; Šinžar-Sekulić, J.; Kuzmič, F.; Šilc, U. Recognising the Role of Ruderal Species in Restoration of Degraded Lands. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 938, 173104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decree, No. 275/1998 Coll., on Agrochemical Testing of Agricultural Soils and Determination of Soil Properties of Forest Land; Ministry of Agriculture: Prague, Czech Republic, 1998.

- Mühlbachová, G.; Kusá, H.; Vavera, R.; Káš, M. Použití diagnostických metod pro hodnocení přijatelných živin v půdě; Výzkumný ústav rostlinné výroby, v.v.i.: Praha, Czech Republic, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Smatanová, M. Výsledky agrochemického zkoušení půd a jejich využití v praxi; Agromanuál.cz, 2023. [Online]. Available online: https://www.agromanual.cz/cz/clanky/vyziva-a-stimulace/hnojeni/vysledky-agrochemickeho-zkouseni-pud-a-jejich-vyuziti-v-praxi (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Kulhánek, M.; Balík, J.; Sedlář, O.; Zbíral, J.; Smatanová, M.; Suran, P. Stanovení přístupné síry v půdě metodou Mehlich 3. Certifikovaná metodika; Česká zemědělská univerzita v Praze, Katedra agroenvironmentální chemie a výživy rostlin, FAPPZ: Prague, Czech Republic, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstvo životního prostředí. Metodický Pokyn: Indikátory Znečištění; MŽP: Prague, Czech Republic, 2013; [Online]. Available online: https://mzp.gov.cz/system/files/2024-09/OES-MZP_%20Indikator-%20znecisteni-akt-2013-20140318_0.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Pflanzensoziologie: Grundlage der Vegetationskunde, 3rd ed.; Springer: Wien, Austria, 1964; 631p. [Google Scholar]

- Chytrý, M.; Kučera, T.; Kočí, M.; Grulich, V.; Lustyk, P. (Eds.) Katalog biotopů České republiky, 2nd ed.; Agentura ochrany přírody a krajiny ČR: Praha, Czech Republic, 2010; [Online]; Available online: https://www.sci.muni.cz/botany/chytry/Chytry_etal2010_Katalog-biotopu-CR-2.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Esri. ArcGIS Pro, Version 3.3, Environmental Systems Research Institute: Redlands, CA, USA, 2025; [Software].

- Janeček, M.; Dostál, T.; Kozlovsky Dufková, J.; Dumbrovský, M.; Hůla, J.; Kadlec, V.; Kovář, P.; Krása, J.; Kubátová, E.; Kobzová, D.; et al. Ochrana zemědělské půdy před erozí: Metodika; Česká zemědělská univerzita v Praze: Prague, Czech Republic, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Society for Ecological Restoration International Science & Policy Working Group. SER International Primer on Ecological Restoration; Society for Ecological Restoration International: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2004; [Online]; Available online: https://www.ser.org/page/SERDocuments (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Grunda, B.; Kulhavý, J. Půdy lesnicky rekultivovaných hald v Ostravsko-karvinském revíru. In Lesnictví; Ústav vědeckotechnických informací pro zemědělství: Praha, Czech Republic, 1984; pp. 321–332. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Cao, Y.; Bai, Z.; Qin, Q. Effects of Soil and Topographic Factors on Vegetation Restoration in Opencast Coal Mine Dumps Located in a Loess Area. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertile, E.; Dvorský, T.; Václavík, V.; Syrová, L.; Charvát, J.; Máčalová, K.; Balcařík, L. The Use of Construction Waste to Remediate a Thermally Active Spoil Heap. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matula, J. Use of Multinutrient Soil Tests for Sulphur Determination. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1999, 30, 1733–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).