Abstract

The key topic of this article is the attempt to take a comprehensive and not always reflected approach to environmental protection in the Ostrava-Karviná agglomeration. It emphasizes the importance of environmental interactions between humans and the landscape, which allow the emergence of environmental-interaction elements. These elements work with a balanced combination of top-down and bottom-up approaches in environmental protection. The research is based on the recognition that one of the key environmental problems of the Ostrava-Karviná agglomeration is the disturbed relationship of inhabitants to the landscape, which negatively affects their willingness to participate in its protection. Within the framework of the work, environmental-interaction elements at model sites of the Ostrava-Karviná agglomeration are identified and analyzed, and their potential for integration into environmental protection systems is assessed.

1. Introduction

Environmental protection is a complex issue that requires a coordinated and interdisciplinary approach. Environmental problems are often addressed in isolation—either by focusing on individual environmental components or within narrowly defined scientific disciplines. However, such an approach fails to reflect the actual interconnectedness of environmental processes and relationships, including the role of humans. To ensure effective and long-term sustainable protection, it is essential to adopt a holistic approach that carefully considers these diverse links and contexts [1,2].

Among the most serious environmental problems today are commonly listed, for example, biodiversity loss, soil degradation, climate change, and water pollution [3,4,5]. However, one key issue that significantly influences all of these is rarely highlighted—the weakening relationship between humans and the landscape, or more broadly, the environment [6,7]. This problem is particularly pronounced in industrial and post-industrial regions, where the landscape has undergone fundamental transformations, historical ties have been disrupted, or a sense of connection to the environment was never formed—especially among populations that migrated for work [8]. The Ostrava-Karviná agglomeration is a typical example of such a region.

This article focuses on the proposed use of so-called environmental-interaction elements as tools that can contribute to environmental protection by restoring the human connection to the landscape. It presents partial results in the form of a methodology aimed at identifying these elements in the landscape, describing them, and proposing their integration into strategic planning documents. The central idea is the harmonious combination of top-down and bottom-up approaches, which may lead to a sustainable and regionally anchored model of environmental protection.

2. Background

Within the current system of environmental protection, two fundamental approaches are generally applied—top-down and bottom-up [9,10]. In practice, these approaches rarely operate in complete isolation. They often overlap or build upon one another at various stages of decision-making processes. Nevertheless, each retains distinct characteristics that influence how environmental protection is perceived, managed, and implemented [11].

The top-down approach is based on a hierarchical model in which strategies and measures are defined at the global, supranational, or national level and subsequently implemented downwards, toward the general public. This approach enables the realization of measures with large-scale impact—for example, through national plans, scientific research, or the fulfillment of international commitments. Its advantage lies in the ability to respond quickly to emerging challenges and to introduce uniform regulatory frameworks [12]. Some of its proponents argue that systemic change can influence societal behavior even without the need for individual-level awareness-raising—by establishing new norms and routines that the population gradually adopts as their own [13]. However, for such measures to have a real impact, they must not only be well formulated in legislation and legally enforceable, but also consistently applied in practice. Top-down approaches are often motivated by pragmatic goals such as efficiency, cost reduction, or the maximization of benefits. A typical example is the concept of ecosystem services, which evaluates components of the environment based on the benefits they provide to humans—from provisioning services (e.g., food production) to cultural services such as recreation or the spiritual value of landscapes [14,15,16,17]. Nevertheless, this approach has also been subject to criticism—especially for its tendency to reduce the value of nature to its utility, thereby neglecting complex environmental interrelations and the ethical dimensions of the human–nature relationship [18].

In contrast, the bottom-up approach represents a model in which initiative arises from the local level—from individuals, communities, or local organizations actively engaging in decision-making processes. This ensures a higher degree of adaptation of measures to the specific conditions of a given place [12]. Since this approach is based on the active participation of residents, their knowledge of the local environment, and their willingness to contribute to its protection, it can lead to the formation of so-called pro-environmental identity—that is, a situation in which people begin to act in favor of the environment out of internal conviction rather than external pressure [19]. The advantages of the bottom-up approach include not only a greater likelihood of acceptance of proposed measures, but also a better identification of their impacts on different social groups [20]. However, this approach also faces certain limitations. In practice, participation tends to come primarily from those who already have a positive relationship with the environment. Conversely, groups that show little interest in environmental issues often remain outside the decision-making processes. Their behavior is thus predominantly influenced by the external framework—namely, top-down measures.

3. Materials and Methods

The chosen methodology is based on the need to understand how environmental protection is structured, managed, and communicated across various levels within the Ostrava-Karviná agglomeration.

3.1. Analysis of Strategic Documents from a Top-Down Perspective

The first step involved an evaluation of strategic documents related to environmental protection within the Ostrava-Karviná agglomeration. This approach corresponds to the logic of the top-down model, in which the systemic framework set by the state or local authorities forms the foundation for implementing environmental measures. The analysis focused on the content of the documents, the way the region is reflected within them, and the extent to which they address the issue of developing the relationship of the citizens to the landscape.

3.2. Analysis of School Textbooks from a Bottom-Up Perspective

The second part of the methodology focused on the analysis of school curriculum documents, specifically textbooks used at primary and secondary schools. Although these materials are also produced within a systemic framework (i.e., from a top-down perspective), they play a key role in shaping the relationship of future generations to the landscape. The research therefore examined how the Ostrava-Karviná agglomeration is represented in these materials. The aim was to determine whether—and how—students are guided toward developing a connection to this region and understanding its environmental context.

3.3. Proposal of an Environmental-Interaction Element as a Tool of a Harmonious Approach

The third part of the methodology is based on our proposed concept of a harmonious approach, which combines both top-down and bottom-up perspectives through the use of so-called environmental-interaction elements.

An environmental-interaction element refers to a specific part of the landscape which—by its nature or the way it is perceived—enables environmental interactions between humans and their surroundings [19]. In essence, it is a material expression of environmental interactions through a tangible landscape element. Environmental interactions can be understood as dynamic processes that shape the relationship between humans and the landscape through various modes of perception and experience. Through these interactions, ordinary natural elements acquire deeper meaning and thus become environmental-interaction elements [21].

Unlike similar concepts used in legislation (such as “landscape elements” or “significant landscape elements”) or in landscape ecology (e.g., “interaction elements”), which are based primarily on biotic or abiotic characteristics, the environmental-interaction element is defined above all by the observer’s subjective experience.

Such an element may take many forms—from an individual organism to a geological formation or even entire biotopes. Its boundaries are not defined solely by physical or biological criteria, but rather by its capacity to evoke interaction with the observer. It is not merely a passive landscape feature in the ecological or geographical sense, but an entity that, through environmental interactions, fosters a deeper human connection to the landscape [21].

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Strategic Documents

Environmental protection in the Ostrava-Karviná agglomeration is not guided by a single, unified, and comprehensively conceived document that would address the issue in broader contexts. Existing strategies focus exclusively on individual components of the environment, and each area is thus addressed separately. The most important overarching document with a broader scope is the Development Strategy of the Moravian-Silesian Region, which, in addition to environmental issues, also covers other areas such as transport, education, culture, and tourism. Environmental protection is mentioned only marginally in this strategy—specifically in the areas of air quality, waste management, climate change adaptation, sustainable land use, environmental education and awareness, and so-called new energy [22,23].

Separate strategic documents have been developed primarily for those environmental components that are most affected in the region. Air quality is addressed in the Air Quality Improvement Program [24]. Water management is covered by the Sub-basin Plans of Upper Oder and Morava and Váh Tributaries [25,26]. Nature and landscape protection is addressed in the Strategy of Nature and Landscape Protection of the Moravian-Silesian Region [27]. These documents often overlap thematically—for example, the climate change adaptation strategy intersects multiple areas at once. However, soil protection, as one of the key environmental components, is not addressed in a separate document; it is mentioned only marginally, mainly in connection with agriculture or adaptation measures.

In this context, human society may also be considered a specific component—within the biosphere, it represents a unique case that, due to its significance and the focus of this study, deserves special attention. Two documents explicitly address the relationship between the population and the environment or region. The first is the Environmental Education and Awareness Strategy of the Moravian-Silesian Region, which aims to promote public awareness, strengthen relationships with the environment, and foster behavioral patterns aligned with the principles of sustainability [28]. The second is the Tourism Management Strategy of the Moravian-Silesian Region which, although primarily focused on tourism development, significantly influences residents’ relationship with the region and, consequently, with the environment as a whole [29].

4.2. Analysis of School Textbooks

The second area analyzed comprised school textbooks for primary and secondary education (a total of 16), which significantly influence the formation of students’ attitudes toward the environment and the region itself. The results of the analysis showed that the Ostrava-Karviná agglomeration is most frequently presented in textbooks through the lens of its industrial past and present. The dominant topics are deep coal mining, metallurgy, and mechanical engineering, which are described as key drivers of regional development. In some cases, the decline of heavy industry and the transformation toward modern sectors—such as the chemical, automotive, or electrical industries—are also mentioned. Nevertheless, the region continues to be portrayed primarily as an industrial center with a marked negative impact on the environment.

The natural characteristics of the region are mentioned only marginally, typically as a contrast—for example, the Beskydy Mountains or Jeseníky Mountains are presented as recreational areas, usually located outside the core territory of the Ostrava-Karviná agglomeration. Cultural and historical landmarks are likewise often situated beyond the industrial core (e.g., Sovinec Castle, Šipka Cave), thus diverting attention away from the specific features of the local landscape. Current environmental changes or possibilities for territorial restoration are rarely addressed in textbooks.

Of the textbooks examined, only two offered a comprehensive approach to the region. The first textbook Czech Republic: Homeland History for Curious Children [30] applies the principle of learning through play and introduces the Ostrava region through practical tasks—for example, by using examples such as glacial erratic or wooden churches located directly in Ostrava. The second textbook Discovering the Secrets of Nature: The Nature of Cieszyn Silesia [31] provides a rich account of the region’s natural features, supplemented by activities, experiments, and local examples. Both publications balance the region’s industrial heritage with an emphasis on natural values and cultural history prior to the onset of deep coal mining. Interestingly, neither of these textbooks has undergone approval by the Ministry of Education.

4.3. Evaluation Criteria

In order to utilize environmental-interaction elements as a tool for environmental protection, it is essential to establish a framework for their systematic assessment. To this end, four categories and corresponding evaluation criteria were proposed. The proposed criteria do not serve merely to classify elements according to ecological significance in the traditional natural science sense but also assess their capacity to mediate environmental interaction between humans and the landscape.

The intention was to identify such elements that can carry deeper meaning and contribute to fostering a positive relationship with a specific place. The evaluation took into account both the intrinsic characteristics of each element and its potential to be used in the context of environmental education, spatial planning, or landscape interpretation. The criteria were formulated regarding the interdisciplinary nature of the concept and the potential for practical application across various fields of environmental protection.

4.4. Visualization of the Complexity of Environmental Protection in the Ostrava-Karviná Agglomeration

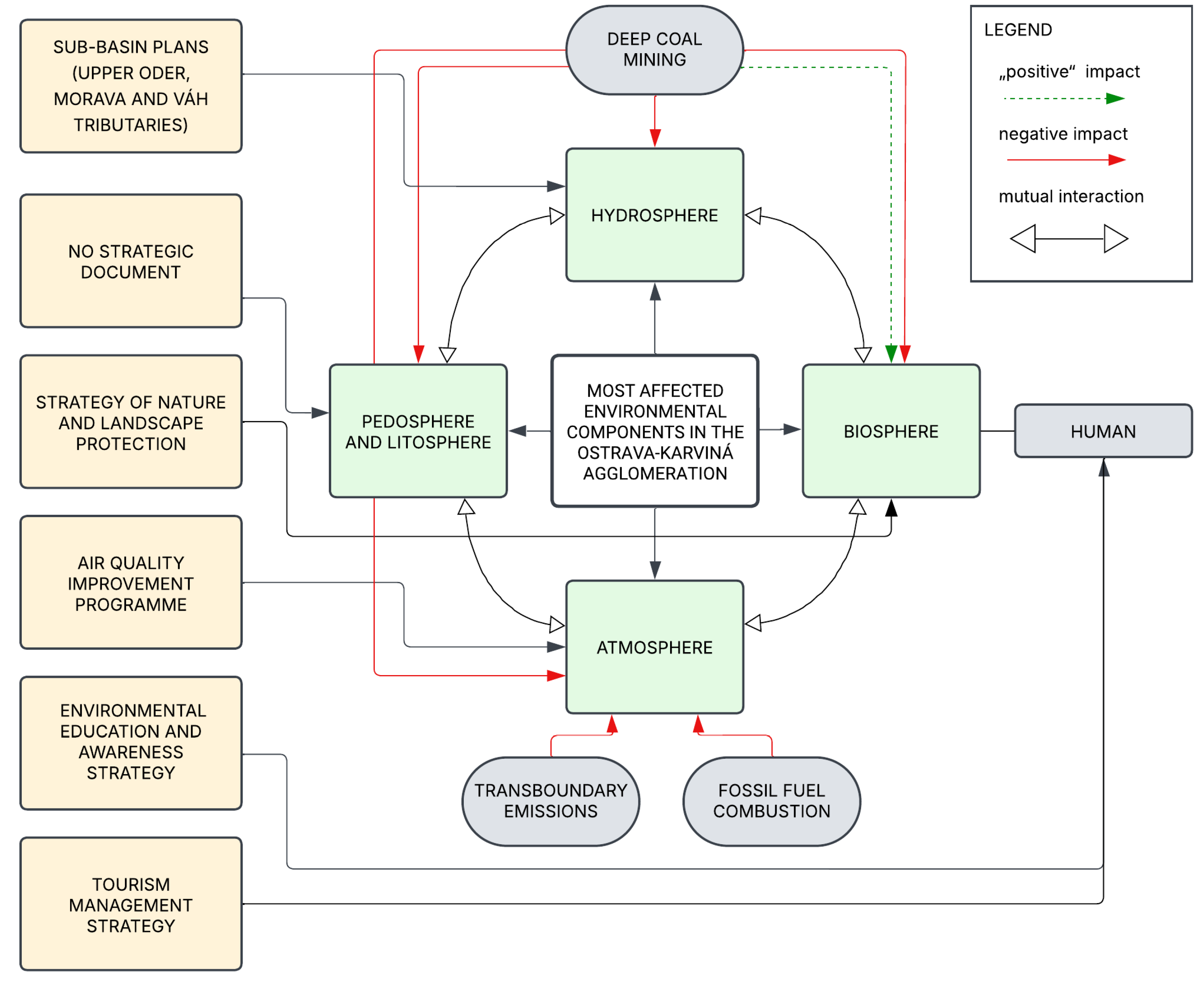

One of the outcomes of this study is a graphical representation (see Scheme 1) of the relationships between individual environmental components and the strategic documents that address their protection. The aim of this diagram was not only to illustrate the thematic structure of environmental protection in the Ostrava-Karviná agglomeration, but above all to highlight its fragmentation and the absence of an overarching, comprehensively conceived approach.

Scheme 1.

The diagram illustrates the complex relationships between key environmental components (light green fields), relevant regional strategic documents (light yellow fields), and dominant anthropogenic influences (gray fields). It emphasizes mutual interactions among environmental components and reveals gaps in strategic coverage (e.g., for soil), underlining the need for an integrated, interdisciplinary approach to environmental protection in the region (created with Lucid Application by authors).

The diagram is based on the results of the analysis of strategic documents (see Section 4.1) and illustrates how individual environmental components—air, water, soil, biosphere, and specifically the relationship between people and the landscape—are addressed in separate documents. It also captures overlaps and thematic intersections, demonstrating that environmental protection cannot be approached in isolation, but requires interdisciplinary coordination.

The visualization also includes documents that do not focus directly on the protection of natural components but have a significant impact on shaping residents’ relationships to their environment (e.g., environmental education or tourism strategies). This is because a weakened relationship to the landscape is, particularly in this region, perceived as one of the key environmental challenges. The diagram thus serves as a synthetic tool that provides a clear overview of existing linkages, helps identify gaps in the system, and supports arguments in favor of a holistic and integrated approach to environmental protection in post-industrial regions.

4.5. Proposed Measures and Tools for Implementing the Harmonious Approach

An effective system of environmental protection in post-industrial regions requires the integration of strategic (top-down) and participatory (bottom-up) levels. Each of these approaches has its strengths and weaknesses: the top-down perspective ensures an institutional and legal framework but often lacks connection with everyday experience, while the bottom-up perspective promotes local engagement but typically reaches only those who already have a positive relationship with the environment.

In this context, environmental-interaction elements can serve as an effective tool of communication between systemic and individual levels. Their implementation in practice may be supported through the following measures:

At the top-down level:

- integrating the concept of environmental-interaction elements into strategic and spatial planning documents (e.g., regional development plans, adaptation strategies, or environmental protection programs),

- creating maps and databases of environmental-interaction elements that can serve as a basis for revitalization, interpretation, and educational projects,

- expanding landscape assessment methodologies to include cultural, perceptual, and identity-related dimensions (e.g., criteria linked to place perception, memory, and local identity),

- supporting the establishment of environmental education centers in regions with a strong industrial legacy.

At the bottom-up level:

- strengthening education and environmental awareness as a means of reaching groups that usually remain outside conventional participatory projects,

- using school textbooks, curricula, and field excursions as natural instruments for shaping young people’s relationship with the landscape,

- restoring and interpreting small landscape and cultural features (e.g., chapels, wells, mining relics, or natural outcrops) through school, community, or interdisciplinary projects,

- developing local guiding and landscape interpretation activities that use environmental-interaction elements as “living laboratories” of environmental education—for example, thermally active spoil heaps, subsidence lakes, sacral monuments, or natural habitats.

Education occupies a special position within this system. Although it is formally a top-down instrument, its universal reach makes it the most effective mechanism for activating bottom-up processes. Textbooks, curricula, and teachers’ daily work mediate a relationship with the landscape even among those who would otherwise not encounter such topics. In this way, education functions as a key bridge between institutional structures and individual experience—and as a foundation for developing environmentally interactive thinking.

Combining both levels—strategic embedding (top-down) and educational or community engagement (bottom-up)—creates a framework that is sustainable, culturally grounded, and open to participation. Environmental-interaction elements represent a practical and symbolic means of this connection: they allow the landscape to be understood not merely as an object of protection, but as a space of living experience, relationship, and identity.

5. Discussion

In the field of environmental protection, there is an ongoing lack of consensus regarding the appropriate extent to which top-down and bottom-up approaches should be applied. Some authors emphasize the potential of top-down governance and its systemic capacity [32], while others point to the importance of active involvement of local residents and communities [12,33]. However, academic literature increasingly reflects a consensus on the need for—and the advantages of—integrating both approaches [19,20].

This resonates with recent international frameworks that link environmental protection with education and competence development [34,35,36]. Such integration of cognitive, affective, and participatory dimensions has been identified as a key factor for sustainable regional development [37,38].

The findings of this study suggest that such a combined model may represent an effective framework for addressing environmental challenges in post-industrial regions such as the Ostrava-Karviná agglomeration. Although individual strategic documents address specific environmental components, they lack coherence and mutual coordination.

In addition, the question of how residents perceive the landscape and what relationship they have with it remains largely overlooked. This aspect is especially important in areas where historical ties to the landscape have been disrupted, and new ones have often failed to form. This condition strongly influences people’s attitudes toward environmental protection and can therefore be considered one of the key environmental challenges. This fact is supported by authors such as Daniš [39], Krajhanzl [40], Berto et al. [41], Mcleod [42], and Grocke et al. [43], who argue that environmentally responsible behavior tends to develop primarily when individuals perceive the landscape as a meaningful part of their everyday lives. Such a relationship is not created in abstract terms, but rather through specific places, phenomena, and repeated experiences that hold personal relevance.

The proposed harmonious approach is grounded in these principles. It seeks to integrate system-level planning with locally embedded experience by employing so-called environmental interaction elements. These elements serve both as a means of restoring—or establishing—people’s relationship with the landscape and as a tool that can be incorporated into environmental protection and land use planning frameworks. By mediating human–landscape interaction in a meaningful way, they contribute to more adaptive, context-sensitive strategies that support long-term environmental sustainability and integrated regional development.

A key challenge lies in incorporating this approach into strategic and planning frameworks. To retain its potential, the environmental interaction approach must remain context-sensitive, flexible, and resistant to reduction into a purely formal or technocratic instrument. Its successful implementation requires collaboration among professionals in environmental protection, education, spatial planning, and public administration. At the same time, it offers a significant opportunity: by linking top-down and bottom-up approaches through the concrete reality of landscape, it can contribute to a functional and regionally anchored model of environmental governance.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study confirm that a comprehensive approach integrating both top-down and bottom-up perspectives is essential for effective environmental protection in post-industrial regions such as the Ostrava-Karviná agglomeration. Environmental-interaction elements can serve as a practical and conceptual bridge between systemic environmental management and local community engagement. Their integration into strategic and planning frameworks, as well as into environmental education, has the potential to enhance both the ecological and socio-cultural dimensions of sustainability. Future research should focus on developing standardized assessment methodologies and exploring the possibilities for incorporating environmental-interaction elements into regional and national policies. Moreover, the proposed harmonious approach is applicable not only in post-industrial landscapes, but also in any area where strengthening the relationship between local inhabitants and their landscapes is essential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K.C. and J.K.; methodology, J.K. and T.K.C.; investigation, T.K.C., J.K. and L.K.; resources, T.K.C. and L.K.; data curation, T.K.C. and L.K.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K.C. and J.K.; writing—review and editing, T.K.C. and J.K.; visualization, T.K.C.; supervision, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, and the APC was funded by Faculty of Mining and Geology, Department of Environmental Engineering.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Benda, L.E.; Poff, L.N.; Tague, C.; Palmer, M.A.; Pizzuto, J.; Cooper, S.; Stanley, E.; Moglen, G. How to Avoid Train Wrecks When Using Science in Environmental Problem Solving. BioScience 2002, 52, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zębek, E.; Augustyniak, M.; Kowalczyk, M. An interdisciplinary approach to environmental protection: Legal, economic, technological, and philosophical considerations. J. Mod. Sci. 2021, 47, 497–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadulaeva, A.; Salamova, A. Evolution of the Global Environmental Agenda: Climate Change, Biodiversity Loss. BIO Web Conf. 2023, 63, 03015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldan, B. Environmentální procesy globálního významu. Zivotn. Prostr. 2019, 53, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kročová, Š.; Čablík, V.; Kubečková, D.; Krylow, M.; Rouchalová, K. Środowisko i jego wpływ na ekosystemy wodne krajobrazów przemysłowych. Inżynieria Miner. 2024, 2, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Jančaříková, K. Odcizování přírodě. Strach z přírody jako modelový příklad odcizování přírodě. In Environmentální Výzkum a Hrozby 21. Století; Cajthaml, T., Frouz, J., Moldan, B., Eds.; Karolinum: Prague, Czech Republic, 2022; pp. 108–128. [Google Scholar]

- Barrable, A.; Booth, D. Disconnected: What Can We Learn from Individuals with Very Low Nature Connection? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, L.; Aytekin, E.A. Transformed landscapes and a transnational identity of class: Narratives on (post-)industrial landscapes in Europe. Int. Sociol. 2019, 34, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Thomas, C. Environmental Governance, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 1–310. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, L.; Gorris, P.; Pahl-Wostl, C. Narratives, narrations and social structure in environmental governance. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 69, 102317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilly, O.; Hüttl, R.F. Top-down and Europe-wide versus bottom-up and intra-regional identification of key issues for sustainability impact assessment. Environ. Sci. Policy 2009, 12, 1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eicken, H.; Danielsen, F.; Sam, J.-M.; Fidel, M.; Johnson, N.; Poulsen, M.K.; Lee, O.A.; Spellman, K.V.; Iversen, L.; Pulsifer, P.; et al. Connecting top-down and bottom-up approaches in environmental observing. BioScience 2021, 71, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSombre, E.R. Individual behavior and global environmental problems. Glob. Environ. Politics 2018, 18, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legesse, S.F.; Degefa, S.; Soromessa, T. Valuation methods in ecosystem services: A meta-analysis. World J. For. Res. 2022, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, Y.; Liu, S.; Fu, B. Ecosystem service: From virtual reality to ground truth. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 2492–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osúchová, J. Ekosystémové služby: Cesta, jak měřit hodnotu krajiny. Živa 2020, 68, 126–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bieganska, J.; Tora, B.; Sinka, T.; Čablík, V.; Hlavatá, M. Reclamation and revitalization of post-mining sites—Ups and downs. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2023, 28, 637–654. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-López, B.; Iniesta-Arandia, I.; García-Llorente, M.; Palomo, I.; Casado-Arzuaga, I.; Del Amo, D.G.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Palacios-Agundez, I.; Willaarts, B.; et al. Uncovering ecosystem service bundles through social preferences. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jans, L. Changing environmental behaviour from the bottom up: The formation of pro-environmental social identities. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 73, 101531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolus, J.F.; Hanley, N.; Olsen, S.B.; Pedersen, S.M. A bottom-up approach to environmental cost-benefit analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 152, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupka, J.; Brázdová, A.; Chowaniecová, T. Environmental Interaction Elements in the Post-Mining Landscape of the Karviná District (Czech Republic). Eng. Proc. 2023, 57, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Databáze Strategií. Available online: https://www.databaze-strategie.cz/czx/strategicke-mapy-kraje/strategicka-mapa-msk (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Moravskoslezský kraj: Strategie Rozvoje Moravskoslezského kraje 2019–2027. Available online: https://www.msk.cz/assets/temata/cestovni_ruch/strategie-rozvoje-msk-2019-2027---navrhova-cast.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Ministerstvo Životního Prostředí: Programy Zlepšování Kvality Ovzduší (PZKO). Available online: https://mzp.gov.cz/system/files/2024-11/OOO-PZKO_aglomeraceCZ08A-200922.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Povodí Odry: Plán dílčího Povodí Horní Odry. 2022. Available online: https://www.pod.cz/plan-Horni-Odry-2022/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Povodí Moravy: Plán Dílčího Povodí Moravy a Přítoků Váhu 2021–2027. Available online: https://pop.pmo.cz/download/web_PDP_Morava_2127/index.html (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Moravskoslezský kraj: Koncepce Strategie Ochrany Přírody a Krajiny. Available online: https://www.msk.cz/assets/temata/zivotni_prostredi/koncepce.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Moravskoslezský kraj: Environmentální Vzdělávání, Výchova a Osvěta. Available online: https://www.msk.cz/assets/temata/zivotni_prostredi/aktualizovana-koncepce-environmentalniho-vzdelavani--vychovy-a-osvety-2021.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Moravskoslezský kraj: Strategie Řízení Cestovního Ruchu Moravskoslezského kraje 2021–2025. Available online: https://www.msk.cz/assets/temata/cestovni_ruch/strategie-rizeni-cestovniho-ruchu-msk-2021-2025_navrhova_cast.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Machatý, R. Vlastivěda pro Zvídavé děti: Česká Republika—Učebnice pro 3.—5. Ročník ZŠ; Fragment ve společnosti Albatros Media a. s.: Praha, Czech Republic, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kupka, J. Objevujeme Tajemství Přírody: Příroda Těšínského Slezska—Učebnice (nejen) pro 4.-5. Ročník ZŠ; Nakladatelství Beskydy ve spolupráci s Pedagogickým centrem pro polské národnostní školství v Českém Těšíně: Český Těšín, Czech Republic, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, W.; Stockwell, C.; Flachsland, C.; Oberthür, S. The architecture of the global climate regime: A top-down perspective. Clim. Policy 2010, 10, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafarasat, Z.A. Defining their real problems, getting public and policy attention: Global struggles of deprived communities for sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 7215–7225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key Competencies in Sustainability: A Reference Framework for Academic Program Development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030: OECD Learning Compass 2030—A Series of Concept Notes; OECD: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/about/projects/edu/education-2040/1-1-learning-compass/OECD_Learning_Compass_2030_Concept_Note_Series.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Sobel, D. Place-Based Education: Connecting Classrooms & Communities; Orion Society: Great Barrington, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniš, P. Děti Venku v Přírodě: Ohrožený Druh? Tereza, Vzdělávací Centrum: Praha, Czech Republic, 2016; ISBN 978-80-87905-10-4. [Google Scholar]

- Krajhanzl, J. Psychologie Vztahu k Přírodě a Životnímu Prostředí: Pět Charakteristik, ve Kterých se Lidé Liší; Lipka & Masarykova Univerzita: Brno, Czech Republic, 2014; ISBN 978-80-210-7063-9. [Google Scholar]

- Berto, R.; Barbiero, G.; Barbiero, P.; Senes, G. An individual’s connection to nature can affect perceived restorativeness of natural environments: Some observations about biophilia. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, L.J.; Kitson, J.C.; Dorner, Z.; Tassell-Matamua, N.A.; Stahlmann-Brown, P.; Milfont, T.L.; Hine, D.W. Environmental stewardship: A systematic scoping review. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0284255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grocke, C.L.; Eversole, R.; Hawkins, C.J. The influence of place attachment on community leadership and place management. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2021, 15, 298–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).