Abstract

The article focuses on allelopathic interactions between plants. It presents the results of the effect of biological extracts from Solidago canadensis and Robinia pseudoacacia on seedlings of Lepidium sativum and Solidago canadensis. Solidago canadensis extracts inhibit the growth of Lepidium sativum, while Robinia pseudoacacia extracts stimulate the growth of Lepidium sativum. The application of Solidago canadensis extracts to Solidago canadensis seedlings showed signs of autotoxicity.

1. Introduction

Invasive plant species represent a significant threat to biodiversity, particularly within sensitive and protected natural ecosystems. Their rapid and aggressive spread is often accompanied by allelopathic effects—namely, the release of biologically active compounds that inhibit the growth and development of neighboring plant species. The use of chemical herbicides near aquatic environments is restricted or prohibited under environmental regulations, highlighting the need for ecologically sound biological alternatives for invasive plant control.

One promising approach involves the development and application of phytotoxic extracts derived from invasive species themselves, offering a sustainable bioregulatory method. This study aims to assess the allelopathic potential of aqueous extracts from Solidago canadensis—collected at various phenological stages and from different plant parts (stem, leaf, inflorescence, root)—and roots of Robinia pseudoacacia, collected as a single batch. The effects of these extracts were tested on seed germination and early growth of Lepidium sativum and Solidago canadensis seedlings.

Species such as Solidago canadensis and Robinia pseudoacacia are not only aggressive colonizers but also potential candidates for biological management. Solidago canadensis is known for forming dense, monodominant stands that displace native flora and reduce local biodiversity [1]. The allelopathic effects of this species are attributed to its high content of secondary metabolites, including phenolic compounds and flavonoids (e.g., quercetin, kaempferol, rutin), as well as phenolic acids such as caffeic, ferulic, and gallic acids [2]. The concentrations of these allelochemicals vary by phenological stage, making this a relevant factor in evaluating their phytotoxicity throughout the growing season.

Robinia pseudoacacia, another invasive species, is widely used in phytoremediation due to its capacity for hyperaccumulating heavy metals (e.g., copper, lead) and its robust root system, which contributes to soil stabilization and remediation of contaminated sites [3,4]. Through symbiosis with nitrogen-fixing bacteria, it can thrive in nutrient-poor soils and rapidly colonize degraded areas. According to Nasir et al. (2005), the lack of understory vegetation beneath Robinia pseudoacacia is largely attributable to allelopathic activity. Isolated compounds such as robinetin, myricetin, and quercetin from its foliage and other tissues exhibit strong allelopathic potential [5]. The roots of Robinia pseudoacacia exert their effects primarily indirectly through the soil and are characterized by a broad spectrum of secondary metabolites [6], including phenolic compounds, alkaloids, and glycosides. These chemical properties highlight Robinia pseudoacacia as a promising potential source of phytotoxic compounds suitable for the biocontrol of other invasive plant species.

Although both Robinia pseudoacacia and Solidago canadensis are considered highly invasive, they also present opportunities for sustainable use in invasive species management. To this end, an analysis of published research was conducted, focusing on the effects of aqueous extracts from invasive plants. Extracts from Solidago canadensis have shown significant allelopathic activity, inhibiting seed germination and seedling growth of both agricultural and grassland species [7,8,9,10,11].

The allelochemicals in these extracts not only reduce seedling biomass and germination rates but also exhibit autotoxic effects, especially when derived from leaves, inflorescences, and roots [8,9]. These effects depend on extract concentration, seed mass, and photoreactivity [7,10]. Afzal et al. (2024) further note that allelopathic effectiveness may be influenced by the degree of plant material decomposition [11].

Research into the allelopathic potential of invasive species could therefore contribute to the development of novel, environmentally friendly strategies for invasive plant control, while also supporting sustainable applications in restoration ecology, soil conservation, phytoremediation, and plant-based biotechnology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Species

This study focused on Solidago canadensis and Robinia pseudoacacia. The allelopathic effects of aqueous extracts from these species were evaluated under controlled laboratory conditions, using seeds and seedlings of Lepidium sativum and Solidago canadensis as test organisms.

2.2. Plant Material Collection

Solidago canadensis plants were collected monthly from April to October 2024 at a reclaimed post-mining site near Paskov (49°44′45.9594″ N, 18°17′52.7994″ E). Plant height ranged from 23 to 134 cm and leaf count from 16 to 58. Plants were separated into leaves, stems, inflorescences, and roots, and dried at 35 °C using a laboratory dryer (Concept digi SO 1030–Concept company, Choceň, Czech Republic).

Robinia pseudoacacia roots were collected in September 2024 in Jistebník (49°44′57.84″ N, 18°9′36.7194″ E) from a recently uprooted ~50-year-old tree. Roots were classified by age: 1, 2, 3, and 4–8 years. After thorough rinsing, they were air-dried in the shade and stored in a dark, temperature-stable room. The dried material was subsequently grounded for extract preparation.

2.3. Preparation of Aqueous Extracts

Solidago canadensis extracts were prepared from 10 g of dry plant material and 100 mL of distilled water, as follows:

- Mix 0 (April): 2.5 g root + 7.5 g shoot;

- Mix I (May): 3.33 g each of leaf, shoot, and root;

- Mix II (May): 2.5 g each of leaf, stem, root, and inflorescence;

- Mix III (October): 2.5 g of leaf, stem, root, and seed-stage inflorescence.

Samples were kept in open glass flasks at room temperature for 72 h and filtered through KA-1 filter paper. Extracts were stored at 4 °C until use.

Robinia pseudoacacia root extracts (10 g and 100 mL) were prepared analogously:

- C1: roots 4–8 years of age;

- C2: 3-year-old root;

- C3: 2-year-old root;

- C4: 1-year-old root.

- CX: mixed root sample (C1: 0.464 g; C2: 3.271 g; C3: 2.628 g; C4: 3.637 g).

All Robinia pseudoacacia extracts were prepared on 19 December 2024, using the same protocol and storage conditions as for Solidago canadensis.

2.4. Cultivation and Germination Conditions

Solidago canadensis seeds, collected manually in Orlová (49°50′32.9892″ N, 18°26′2.6628″ E), were sown on 18 December 2024, onto KA-1 filter paper placed in 17 cm diameter Petri dishes. Seeds weighing 0.01 g (weighed using a Denver Instrument SL-234A analytical balance-Denver instrument Company, Denver, CO, USA) were added to each dish. Seeds were sown without surface sterilization to mimic natural conditions. The ambient temperature was maintained at 23 °C. Germination was supported by distilled water and a photoperiod extended by 3–4 h daily using 4500–5000 K LED lighting. Dishes were regularly ventilated. Germination began on 24 December 2024, and the first true leaves emerged on 21 January 2025.

Parallel control samples were established using Lepidium sativum to test the same Solidago canadensis and Robinia pseudoacacia extract variants. These control groups included:

- Control K: Lepidium sativum irrigated with distilled water;

- Control KK: Lepidium sativum co-cultivated with Solidago, irrigated with distilled water.

Lepidium sativum in sample KK was sown as an intercrop on 14 January 2025, after the emergence of cotyledons of Solidago canadensis. Germination began on 16 January 2025, and all control and treatment samples were maintained under identical environmental conditions.

2.5. Extract Application

When seedlings reached the cotyledon stage, a single foliar application of the prepared extracts (Mix 0, I, II, III for Solidago canadensis; C1–C4 and CX for Robinia pseudoacacia) was performed using a manual sprayer. Spraying was applied “to first drop”. Control groups KK and K were treated with distilled water under the same conditions.

2.6. Measurement of Growth Response

At the stage of the first true leaf, root and hypocotyl elongation was measured under a STEMI DV 4 microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany) using a calibrated grid slide (1 mm × 1 mm). Growth response was used to evaluate allelopathic effects.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All data were processed and visualized using R software (version 4.4.1) [12]. Basic descriptive statistics were calculated for the data sets, which were subsequently visualized using box plot diagrams.

3. Results

The complete dataset of measured growth response is available in Supplementary Material.

3.1. Results of Extract Application

A single foliar application of Solidago canadensis and Robinia pseudoacacia extracts was performed on seedlings at the cotyledon stage. Plants exhibited a rapid physiological response following treatment. Within five hours of application, Lepidium sativum seedlings showed signs of turgor loss and hypocotyl bending. Despite these symptoms, the seedlings remained viable. In some cases, a compensatory attempt to initiate additional primary roots was observed in response to root tissue necrosis.

Solidago canadensis extracts—characteristically dark brown—also induced visible discoloration in the hypocotyl and root zones (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Lepidium sativum after Solidago extract application.

In contrast, Robinia pseudoacacia extracts did not result in any observable pigmentation changes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Lepidium sativum after Robinia extract application.

After 15 h, the strongest reactions were recorded in response to Mix 0 and Mix I extracts from Solidago canadensis.

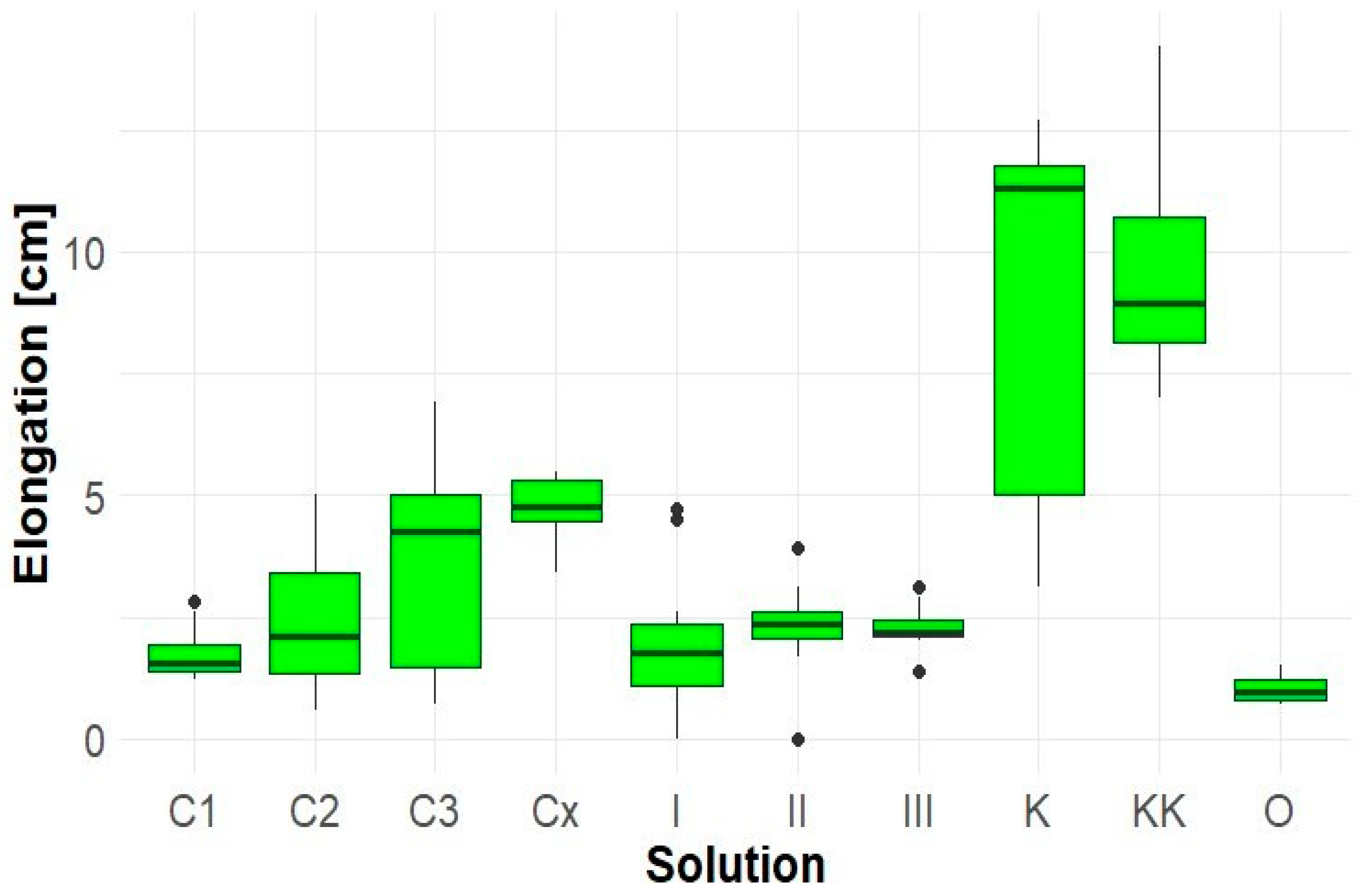

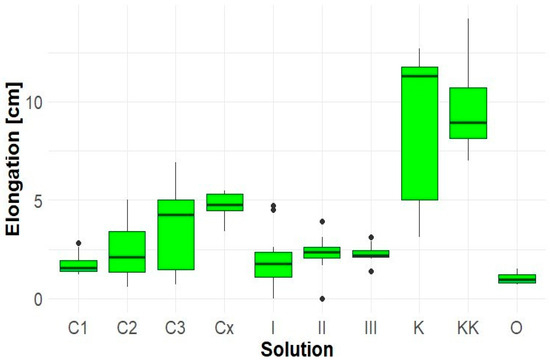

3.2. Root Elongation

The greatest root growth of Lepidium sativum was most frequently observed in the control (K), where roots reached up to 12.7 cm. Co-cultivation with Solidago (sample KK) resulted in a marked growth suppression, likely due to competition or the influence of allelopathic compounds. Extracts from Robinia pseudoacacia (samples C1, C2, C3, Cx) exhibited a negative effect on root elongation in Lepidium sativum (Figure 3). Aqueous extracts of Solidago canadensis (samples I, II, III, O) applied to Lepidium sativum significantly inhibited root growth (Figure 3). The lowest elongation was recorded in sample O (1 cm), which also exhibited pronounced necrotic changes. The average root lengths in control samples were: K—8.8 cm, KK—9.5 cm.

Figure 3.

Elongation of Lepidium sativum roots.

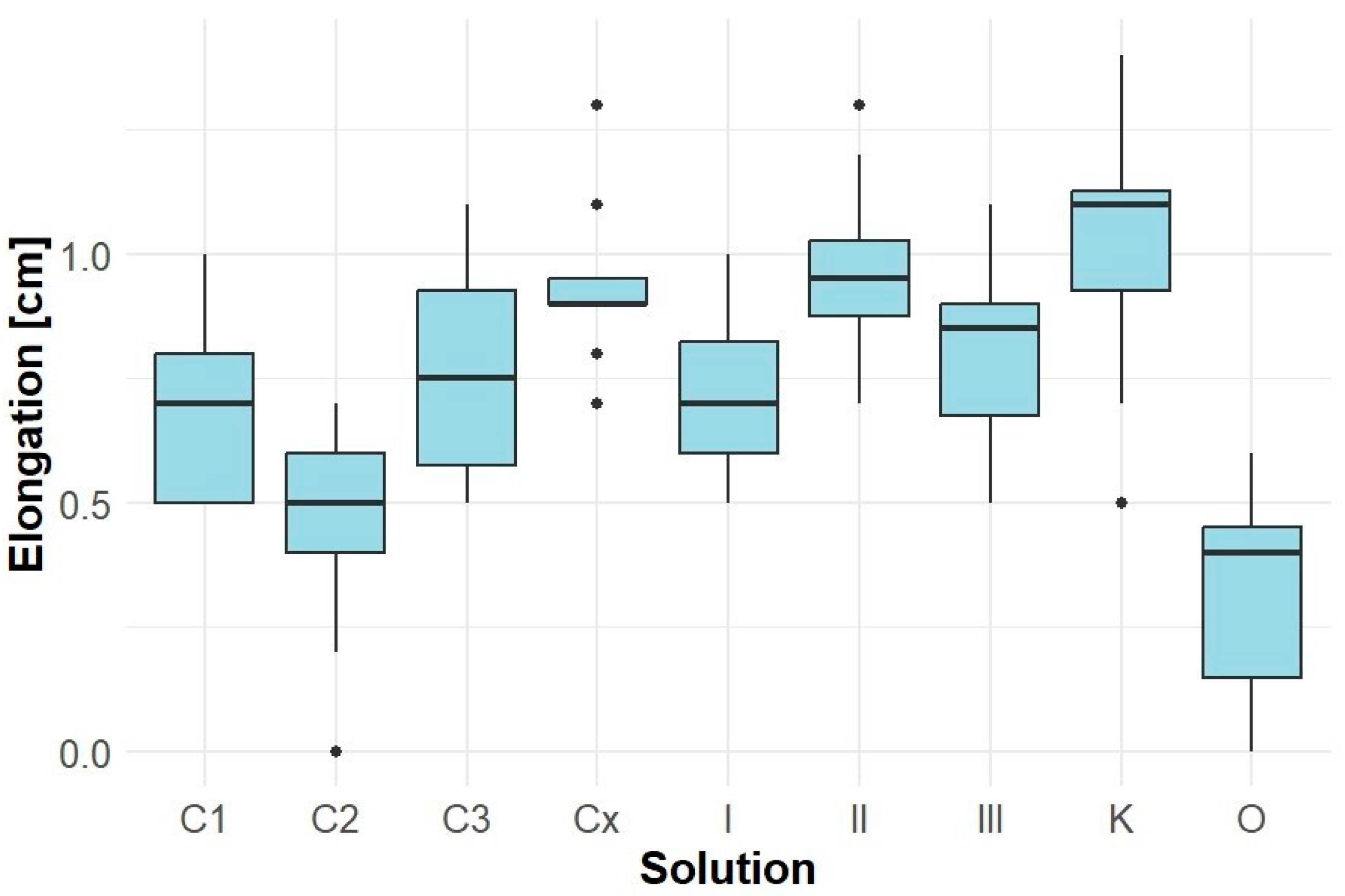

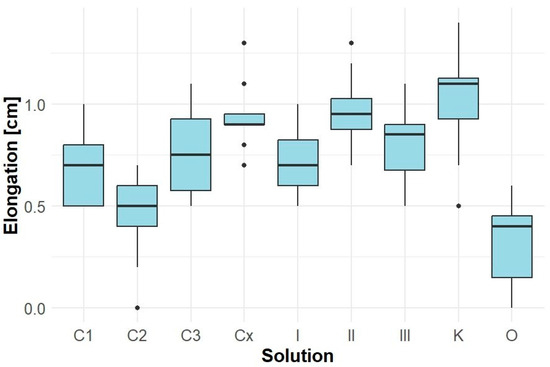

The root length of Solidago canadensis seedlings (samples of Lepidium sativum co-cultivated with Solidago canadensis) was relatively low in all variants, with the control sample K showing an average elongation of approximately 1.0 cm (Figure 4). Aqueous extracts from Robinia pseudoacacia (C1–Cx) did not significantly affect root growth, with values ranging between 0.7 and 1.0 cm. Similarly, Solidago canadensis extracts I, II, and III did not result in significant inhibition. In contrast, sample O exhibited a very strong root growth inhibition (average < 0.3 cm), accompanied by severe root necrosis.

Figure 4.

Elongation of Solidago canadensis roots.

These results indicate that Solidago canadensis extracts have a limited inhibitory effect on the root growth of their own seedlings, apart from variant O. Extracts from Robinia pseudoacacia had a neutral effect.

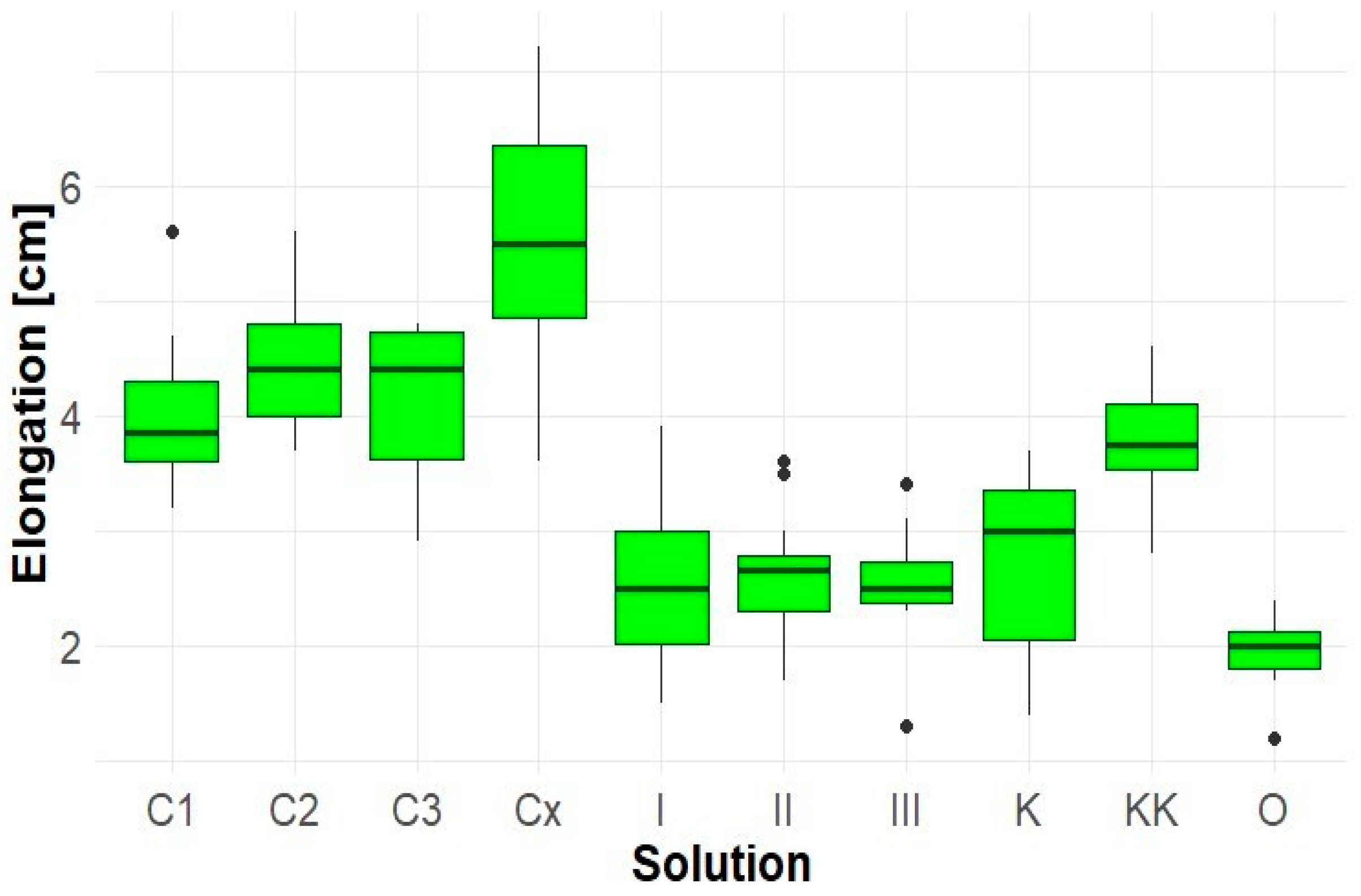

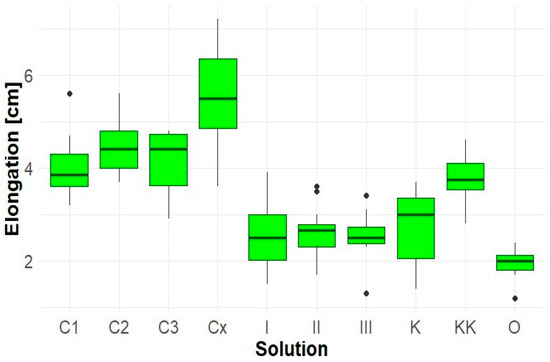

3.3. Hypocotyl Elongation

The extract of Solidago canadensis exhibited a pronounced inhibitory effect on the hypocotyl elongation of Lepidium sativum (Figure 5). All tested concentrations (I, II, III, and O) led to a significant reduction in average hypocotyl length compared to the control samples (K, KK), with the lowest values observed in sample O (average 2.0 cm).

Figure 5.

Elongation of Lepidium sativum hypocotyl.

In contrast, extracts from Robinia pseudoacacia did not show any inhibitory effect and, in some cases, even demonstrated a stimulatory influence (Figure 6). This trend was most evident in sample Cx, where the average hypocotyl length exceeded 5.5 cm, representing an increase of approximately 45% compared to the KK control. These results suggest that the allelopathic potential of Robinia root extracts towards Lepidium is minimal or absent or may depend on the concentration and method of extract preparation.

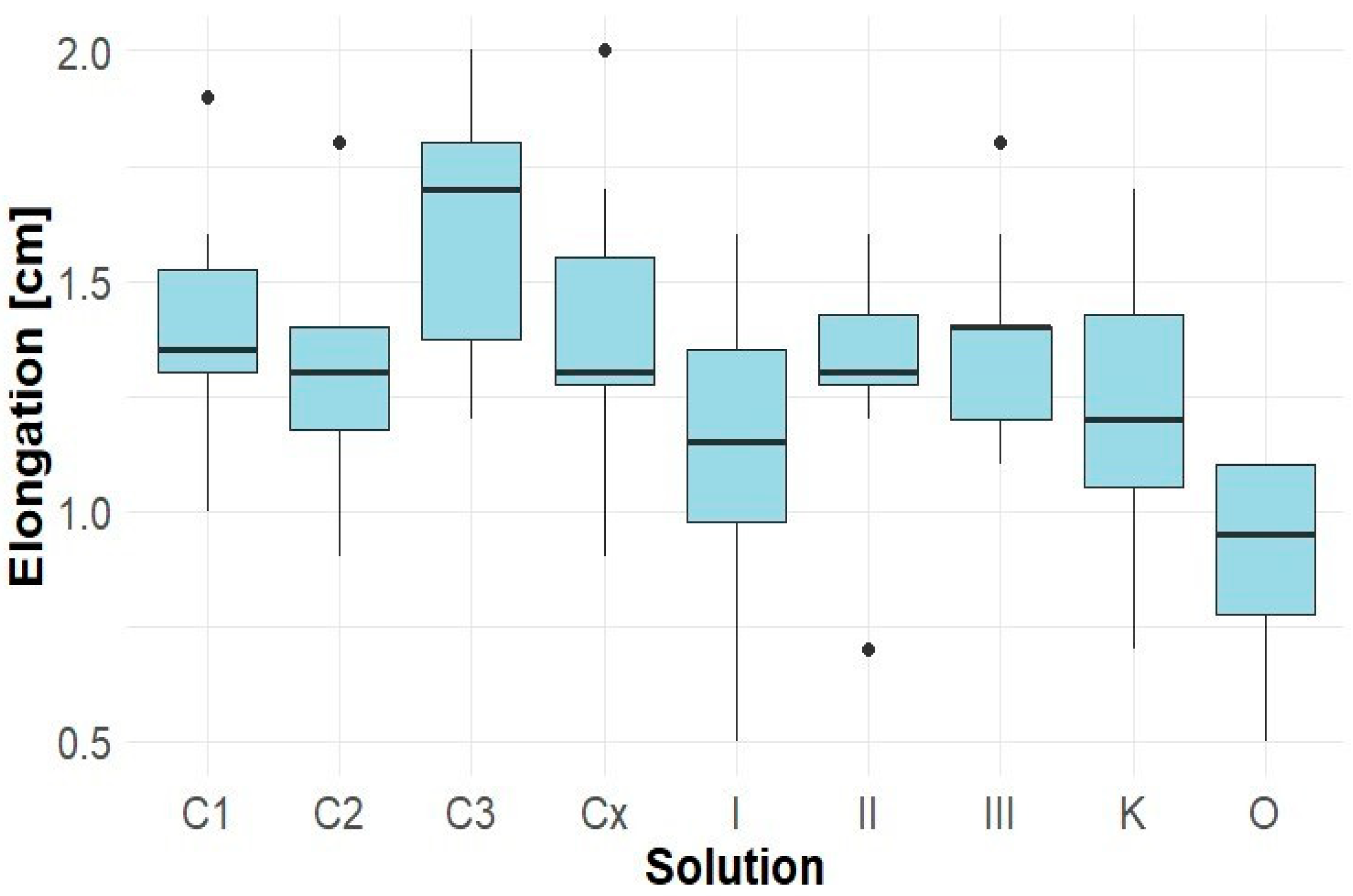

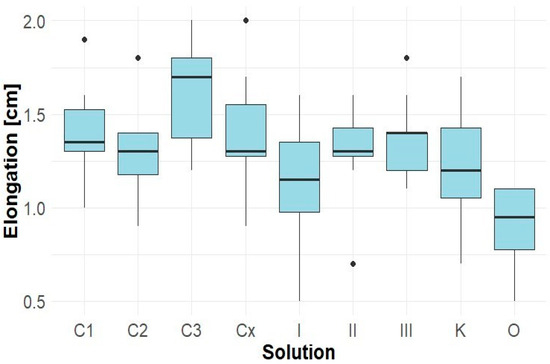

Figure 6.

Elongation of Solidago canadensis hypocotyl.

The results further indicate that Solidago canadensis extracts (I, II, III, O) slightly reduced the hypocotyl length of their own seedlings. The lowest values were recorded in sample O (1.0 cm), while control K reached approximately 1.4 cm. However, the degree of inhibition was not substantial.

Extracts of Robinia pseudoacacia (C1–Cx) did not restrict growth, and in some cases (particularly sample C3), the stem length exceeded that of the control (~1.8 cm), indicating a potential stimulatory effect.

4. Discussion

Auto-allelopathic effects of Solidago canadensis seedlings were confirmed during the experiment. Seedlings exhibited reduced growth dynamics when exposed to aqueous extracts derived from conspecific plant material. This phenomenon is consistent with previous findings, particularly under the influence of extracts from young plants or those collected during the budburst and flowering phases [8]. In our study, this effect was pronounced and clearly observable (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Lepidium sativum plants co-cultivated with Solidago canadensis.

The observed auto-allelopathy supports the potential application of Solidago canadensis as a natural source for the development of bioherbicides and as a biocontrol agent in invasive species management [8,10].

Previous research has shown that the phytotoxic activity of Robinia pseudoacacia is primarily associated with its aboveground biomass, especially when applied fresh [4]. In our study, root aqueous extracts were used, which may account for the relatively milder effects observed on Lepidium sativum seedlings. Nevertheless, the extracts still produced a measurable response, indicating that secondary metabolites present in the roots—capable of release under natural conditions [6]—may contribute to allelopathic interactions. Future research could explore the effects of adjusted extract concentrations or repeated applications to enhance phytotoxic impact.

A notable finding was the suppression of Lepidium sativum growth even in the control group without any extract treatment. This may reflect passive allelopathic effects or intraspecific competition due to high sowing density, as previously reported by other studies [2,7].

Our results demonstrated a pronounced allelopathic effect of Solidago canadensis aqueous extracts on Lepidium sativum seedlings, as evidenced by a significant reduction in both root and hypocotyl growth compared to control groups (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6). Pronounced inhibitory effects were observed with extracts derived from aboveground biomass collected at various phenological stages. These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting high phytotoxicity of Solidago canadensis leachates [7,9].

By contrast, Robinia pseudoacacia extracts exhibited comparatively weaker effects, likely due to the lower concentration or different composition of allelopathic compounds in root tissues. This aligns with reports indicating that the phytotoxicity of Robinia pseudoacacia is more prominent in its aerial organs and when using fresh biomass [4]. The observed inhibitory effects on Lepidium sativum seedlings may be attributed to the presence of secondary metabolites such as glycosides, saponins, phenolics, and alkaloids.

An interesting observation emerged from the comparison of control treatments: the mixed control group (KK), consisting of Lepidium sativum co-cultivated with Solidago canadensis and irrigated with distilled water, exhibited signs of growth inhibition (Figure 7) compared to the absolute control (K) of Lepidium sativum alone. This suggests passive allelopathic interactions through root exudates and supports previous findings that Solidago canadensis is capable of releasing allelochemicals into its rhizosphere [11], thereby forming a chemical exclusion zone around its seedlings.

Additionally, in certain extract variants, stimulation of root growth or initiation of new roots was observed. This may result from the presence of low concentrations of growth-promoting compounds (e.g., phytohormones) in the extracts, or from compensatory responses of the treated seedlings. Similar stimulatory effects have been documented for diluted allelochemical solutions [10], underscoring the dose-dependence and phenological sensitivity of plant material used for extract preparation.

Overall, this study confirms that Solidago canadensis possesses a strong allelopathic potential, exerting inhibitory effects on both heterospecific and conspecific seedlings. This trait may be exploited in biological weed control strategies and offers insights into the ecological dynamics of invasive plant dominance. Despite its milder effects, Robinia pseudoacacia also demonstrated measurable allelopathic activity, particularly in root-mediated interactions.

5. Conclusions

The results of the experiment revealed significant differences in species-specific responses to extracts derived from invasive plants. Lepidium sativum exhibited substantially higher sensitivity to allelopathic effects compared to Solidago canadensis.

The effect of Robinia pseudoacacia root extracts on the monitored parameters was generally weak and mostly insignificant. In some cases (e.g., Lepidium sativum hypocotyl), a mildly stimulatory effect was observed. The chemical composition of the extracts from this woody species is complex, and certain secondary metabolites may only be released under specific conditions or from other plant parts (e.g., leaves and seeds).

Both studied species, Solidago canadensis and Robinia pseudoacacia, can therefore be regarded as promising sources of natural phytotoxins with potential applications in biocontrol and biocoenotic management strategies. These properties may be further exploited in fields such as land reclamation and ecological restoration, agriculture and forestry, landscape ecology, the development of environmentally friendly agrotechnology, and environmental engineering—including the remediation of contaminated soils and the sustainable management of ecosystems.

Supplementary Materials

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. The supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/engproc2025116015/s1. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B. and B.S.; methodology, D.B., B.S. and P.P.; investigation, D.B.; resources, D.B. and B.S.; data curation P.P. and B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B., P.P. and B.S.; writing—review and editing, P.P. and B.S.; visualization, P.P.; supervision, B.S.; funding acquisition, B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by LIFE Programme, project No. LIFE20 IPC/CZ/000004, “IP LIFE for Coal Mining Landscape Adaptation”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rajdus, T.; Svehlakova, H.; Plohak, P.; Stalmachova, B. Management of Invasive Species Solidago canadensis in Ostrava Region (Czech Republic). In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference “Advances in Environmental Engineering” (AEE2019), Ostrava, Czech Republic, 25–27 November 2019; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 444, p. 012046. [Google Scholar]

- Chernyaeva, K.V.; Zhuravleva, A.E.; Viktorov, V.P.; Konichev, V.S.; Kozlenkov, G.M. On the Importance of Chemosystematic Correlation in the Study of the Allelopathic Potential of Congeneric Native and Exotic Species of Herbs. Izv. Saratov Univ. New Ser. Ser. Chem. Biol. Ecol. 2023, 23, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezuhla, L.; Bieloborodova, M.; Bondarenko, L.; Herasymenko, T. Recreation Areas Optimisation and Nature Exploitation in Urban Ecosystems. Stud. Reg. I Lokal. 2023, 3, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chirilă Băbău, A.M.; Micle, V.; Damian, G.E.; Sur, I.M. Lead and Copper Removal from Sterile Dumps by Phytoremediation with Robinia pseudoacacia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasir, H.; Iqbal, Z.; Hiradate, S.; Fujii, Y. Allelopathic Potential of Robinia pseudoacacia L. J. Chem. Ecol. 2005, 31, 2179–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferus, P.; Bošiaková, D.; Konôpková, J.; Hoťka, P.; Kósa, G.; Melnykova, N.; Kots, S. Allelopathic Interactions of Invasive Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) with Secondary Aliens: The Physiological Background. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2019, 41, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, P.C.D.; Chmielowiec, C.; Szymura, T.H.; Szymura, M. Effects of Extracts from Various Parts of Invasive Solidago Species on the Germination and Growth of Native Grassland Plant Species. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gala-Czekaj, D.; Synowiec, A.; Dąbkowska, T. Self-Renewal of Invasive Goldenrods (Solidago spp.) as a Result of Different Mechanical Management of Fallow. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jiang, K.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J.; Wu, B. Moderate and Heavy Solidago canadensis L. Invasion Are Associated with Decreased Taxonomic Diversity but Increased Functional Diversity of Plant Communities in East China. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 112, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpavičienė, B.; Danilovienė, J.; Vykertaitė, R. Congeneric Comparison of Allelopathic and Autotoxic Effects of Four Solidago Species. Bot. Serbica 2019, 43, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.R.; Naz, M.; Ullah, R.; Du, D. Persistence of Root Exudates of Sorghum bicolor and Solidago canadensis: Impacts on Invasive and Native Species. Plants 2024, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).