Abstract

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles are being applied in an increasing number of fields; however, their autonomous operation is associated with significant regulatory challenges. In this study, the performance of a PID and a Model Predictive Controller is compared based on the transfer function of the BLDC motor of a quadcopter using MATLAB simulations in the presence of white noise. The simulation results are used as reference values for measurements conducted on a cost-effective, custom-developed prototype drone. The prototype has been designed for short-duration hovering, allowing for an initial evaluation, but a more thorough analysis requires prolonged hovering tests to be carried out in an industrial environment. Based on the results, a recommendation is formulated for improving the PID controller to achieve performance closer to that of the MPC. The research is aimed at enhancing the energy efficiency of UAV systems and optimizing battery capacity, enabling longer autonomous flight time and more reliable control.

1. Introduction

The application of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) is rapidly expanding, and they are being utilized in an increasing number of fields. Drones are being employed for agricultural [1], transportation, and maritime navigation purposes, such as traffic monitoring and the detection of vessels lacking Automatic Identification System (AIS) [2]. They are also being used extensively for rescue operations [3]. With the growing demand for autonomous operation, the ability of drones to react independently has been brought to the forefront; for instance, automatic takeoff and alerting can be triggered from a docking station in the event of intrusion [4,5]. Another emerging application is the forerunner drone concept, in which autonomous flight is performed ahead of Emergency Ground Vehicles (EGV) to prevent collisions with road traffic [6].

The main causes of drone accidents have been identified as human factors, including inattentiveness, fatigue, and poor situational awareness [7]. In Australia, 60% of drone accidents have been attributed to technical failures [8], while in the city of Hangzhou, system malfunctions and low battery levels were reported as primary causes [9]. Although risks can be reduced with autonomous functions, their implementation requires substantial expertise [10].

In 97% of UAVs, Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controllers are applied for altitude control [11], and 90% of industrial systems also rely on this type [12]. Despite their popularity, PID controllers have been associated with several limitations, including low disturbance tolerance, limited adaptability, stability issues, and lack of robustness [13,14,15]. Their effectiveness is adequate under stable conditions, but performance degradation has been observed in unknown or adverse environments [16].

In this study, the performance of PID and Model Predictive Controller (MPC) controllers was compared in the control of a quadcopter BLDC motor. Based on the transfer function from a previous study, an MPC was designed and tested using MATLAB R2023b simulations in the presence of white noise.

Theoretical results were evaluated under laboratory conditions on a cost-effective, self-developed drone prototype, where disturbances were simulated using artificial wind gusts. The PID controller was then improved using a gain scheduling (GS-PID) method to approach the performance of the MPC.

In this study, the control objective was defined as the achievement of stable altitude regulation with minimal power consumption and low oscillation, even in the presence of external disturbances such as wind gusts. The primary aim was the assessment and comparison of the efficiency and robustness of different control strategies under these conditions. In the case of the custom-developed drone model, the system was required to maintain steady hovering between 8 and 10 cm in altitude, even during wind-induced disturbances.

2. Presentation of the Theoretical Background of the Research

The research was based on the work of Ahmed et al. [17], in which the transfer function of a quadcopter BLDC motor was experimentally determined (1):

where represents the transfer function, and denotes the Laplace transform variable. Based on this function, a PID controller was designed by Ahmed et al. [17].

Using Equation (1), the PID parameters were tuned by Say et al. [18] through a genetic algorithm, where the best results were obtained using remainder selection , , and , where the values correspond to the proportional, integral, and derivative terms, respectively.

In the present study, these values were applied, and the original results were reproduced. The performance of the PID controller was then evaluated in the presence of white noise. Subsequently, an MPC was designed based on transfer function (1), and the performance of the two controllers was compared. The theoretical results served as reference values for the practical tests conducted on a cost-effective drone prototype, where external disturbances were modeled using fan-generated wind. A proposal was made for improving the PID controller.

3. Presentation and Implementation of the MPC in MATLAB Environment

In this research, a discrete-time MPC was implemented in the MATLAB environment for a quadcopter BLDC motor, based on the transfer function (1) defined by Ahmed et al. [17]. The system was transformed into a state-space form and discretized with a sampling time of . During this process, the following matrices were obtained:

where denotes the state matrix, the input matrix, and the output matrix in the discretized state-space model.

The stability of the system was examined based on the eigenvalues of the matrix, which were found to be (0.5816, 0.5816, 0.9198), thus confirming system stability.

The cost function of the MPC is described for the discretized system in (5), according to [19]:

where is the cost function, is the reference signal in vector form, is the vector of predicted output values, is the vector of changes in the control inputs, and is a diagonal matrix containing the control weights, which is a scalar value in the case of a SISO system.

The prediction () and control horizon () values were determined through numerical optimization using the Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) algorithm. During the optimization process, the squared error with respect to the reference signal was minimized. The following optimal values were set and . The input and output weights were selected as 0.82513 and 1.3044, respectively, to improve control performance. The input weight penalized rapid changes in the control signal, while the output weight emphasized accurate reference tracking. With the configured MPC, an average power reduction of 0.04 W and a decrease in overshoot of 1.62 W were achieved compared to the PID controller.

Simulation Results in the Presence of White Noise

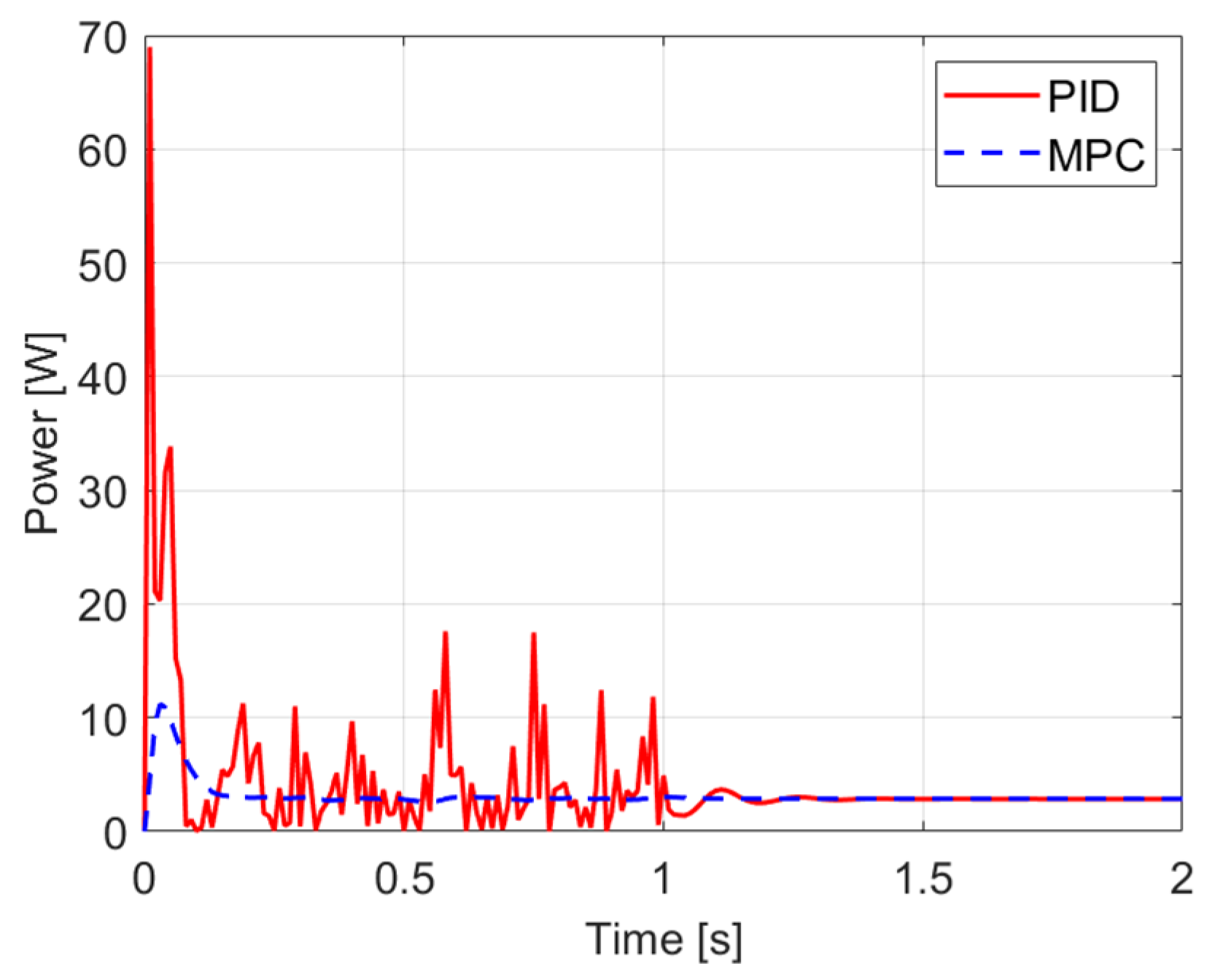

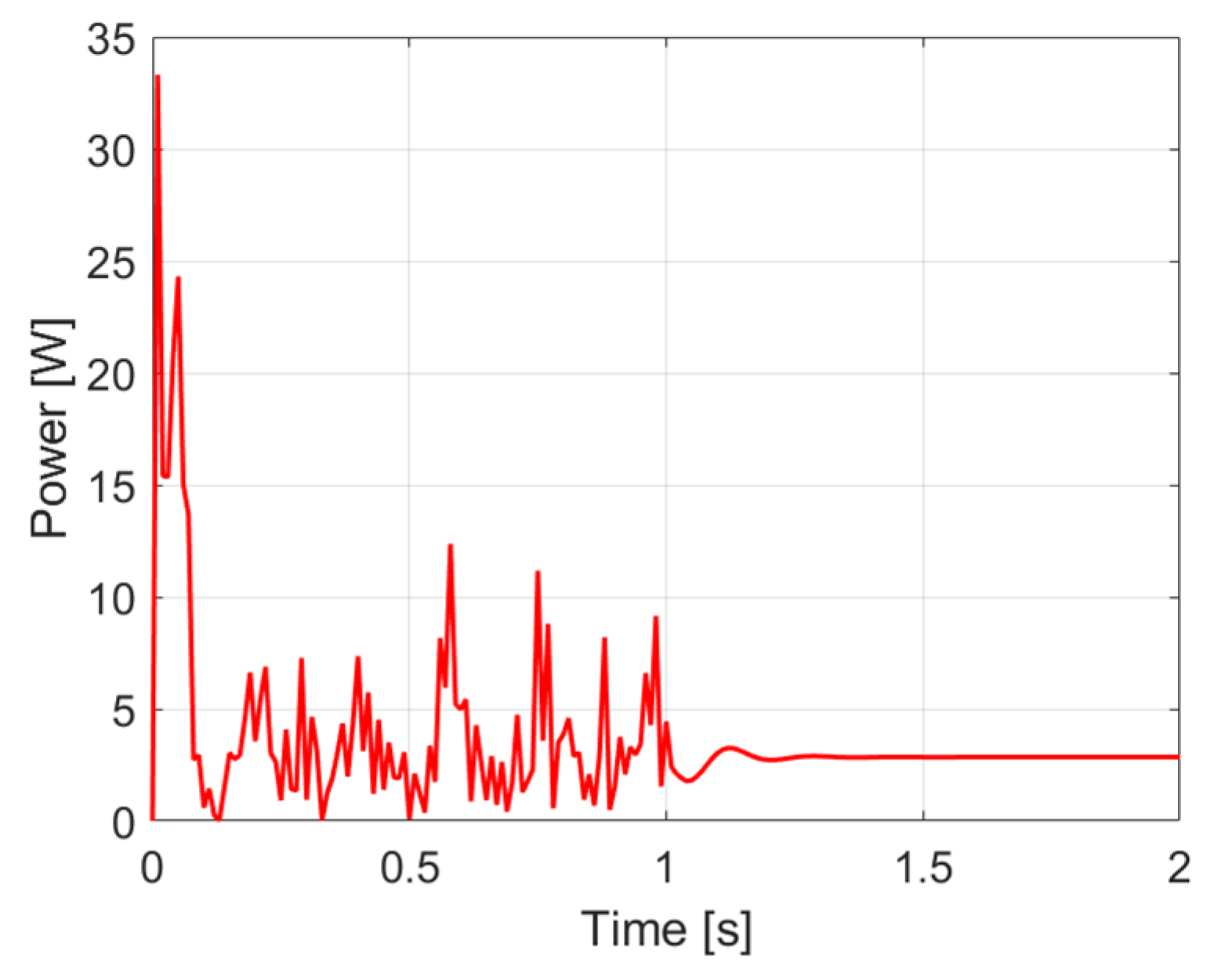

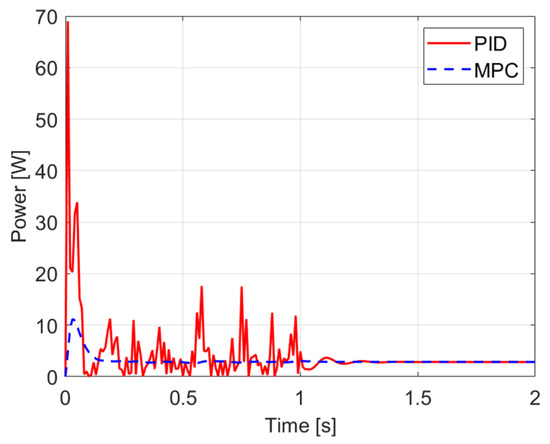

The performance curves of the PID and MPCs under white noise conditions are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Comparison of power curves with white noise applied to the output.

During the simulations, the performance of the PID and MPCs was compared in the presence of white noise. The noise, with an amplitude ranging from −0.3 to 0.3, was applied to the system output during the first 1 s, then set to zero.

A peak power of 68.99 W was observed for the PID controller at 0.01 s, while the MPC reached only 10.9 W at 0.04 s. For the PID controller, oscillations between 0 W and 20 W were detected, whereas for the MPC, the values remained between 2.541 W and 3.02 W. After the noise ceased, the power of the PID controller stabilized only after 0.32 s (within 1.551–4.913 W), while the MPC rapidly reached its steady-state value of 2.8704 W. The average power consumption was measured as 4.18 W for the PID controller and 3.13 W for the MPC, representing a 25% reduction in energy usage. The PID controller responded more strongly to the disturbance, while the MPC behaved more predictably with fewer oscillations. Based on the results, greater stability and energy efficiency were achieved by the MPC in the presence of disturbances.

To enable a comparison of computational demand, both control algorithms were tested under identical conditions in the MATLAB environment. Based on the measured results, each cycle of the PID controller was completed in approximately 0.86 milliseconds on average, while the MPC required around 1.58 milliseconds. This indicates that the MPC imposed nearly twice the computational load. It can be concluded that the increased computational requirements of MPC may represent a limiting factor when applied in resource-constrained embedded systems.

4. Custom-Built Drone Model for Investigating the Energy Efficiency of Controllers

4.1. Description of the Implemented Prototype

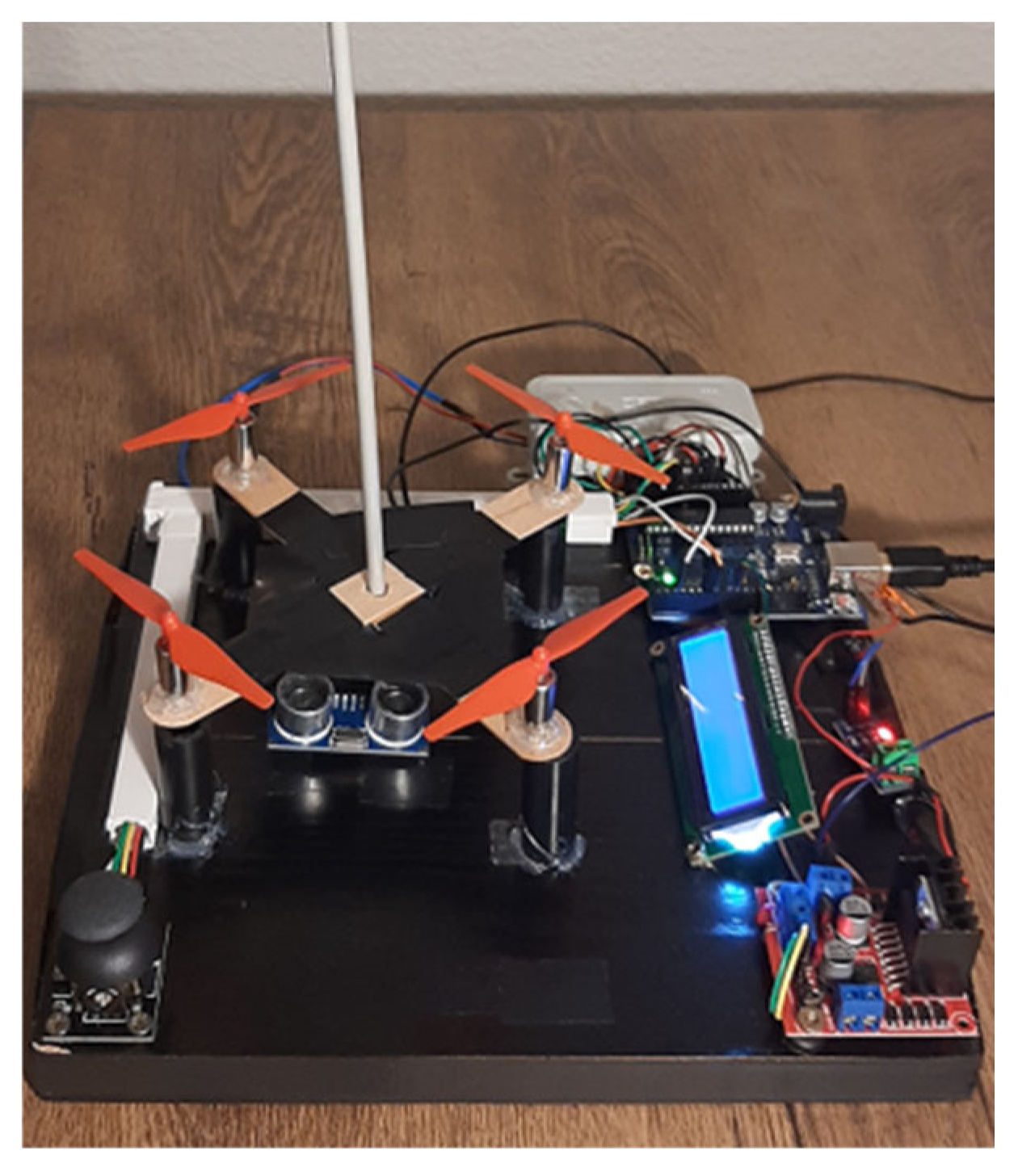

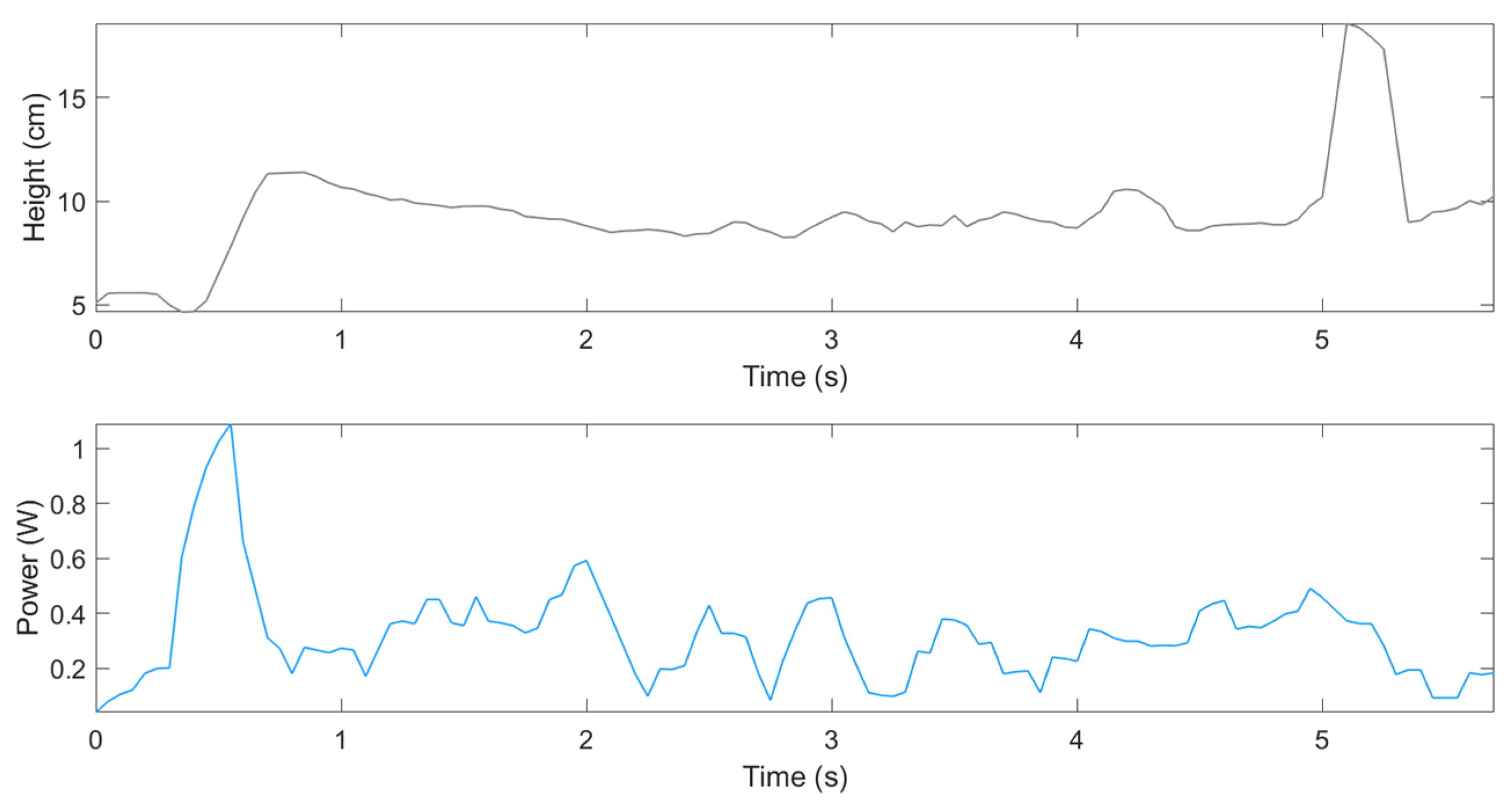

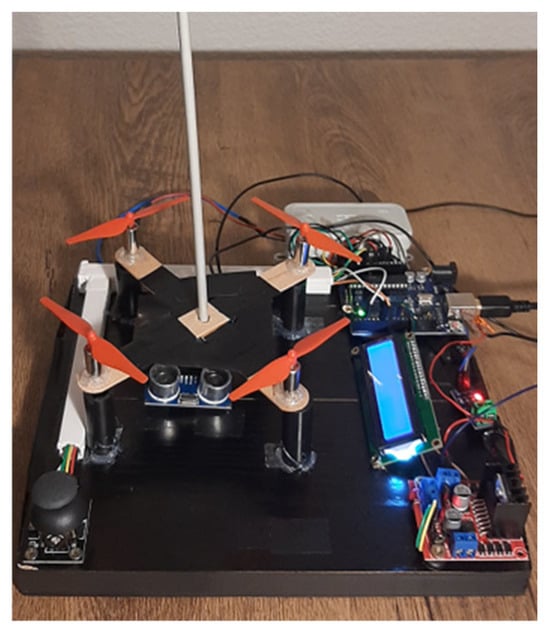

The objective of the model was to enable the practical comparison of PID and MPCs, examining which controller ensures more efficient energy usage during hovering. The implemented model is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The physically realized drone model.

For the targeted investigation of altitude control, a custom-developed, single-degree-of-freedom drone prototype was utilized, in which the motion was mechanically constrained along a 35 cm long guide rod, allowing for a vertical range of 30 cm. The altitude was monitored by an HC-SR04 ultrasonic sensor (OSEPP Electronics Ltd., Shenzhen, China). Propulsion was provided by four 4.2 V DJI Tello motors (SZ DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), powered by a 19 V, 3.95 A laptop adapter. The voltage was reduced to 16.8 V using a buck converter and distributed among the motors. An L298N module was applied for motor control, while central control was carried out using an Arduino Uno. Current consumption was measured by an ACS712 sensor (Allegro MicroSystems, LLC, Worcester, MA, USA). Since the computational capacity of the Arduino was insufficient, control algorithms and signal processing were performed in the MATLAB environment.

A potential direction for future research is represented by the implementation and testing of the controllers on a real UAV platform with multiple degrees of freedom.

4.2. Analysis of the Results Obtained from the Physical Drone Model

During the examination of the physical model, wind disturbance was simulated using a fan positioned at a 45-degree angle. The average wind speed was measured as 10.6 km/h using a HoldPeak HP-876 anemometer (Zhuhai JiDa Huapu Instrument Co., Ltd., Zhuhai, China). This wind load posed a significant challenge for the controllers.

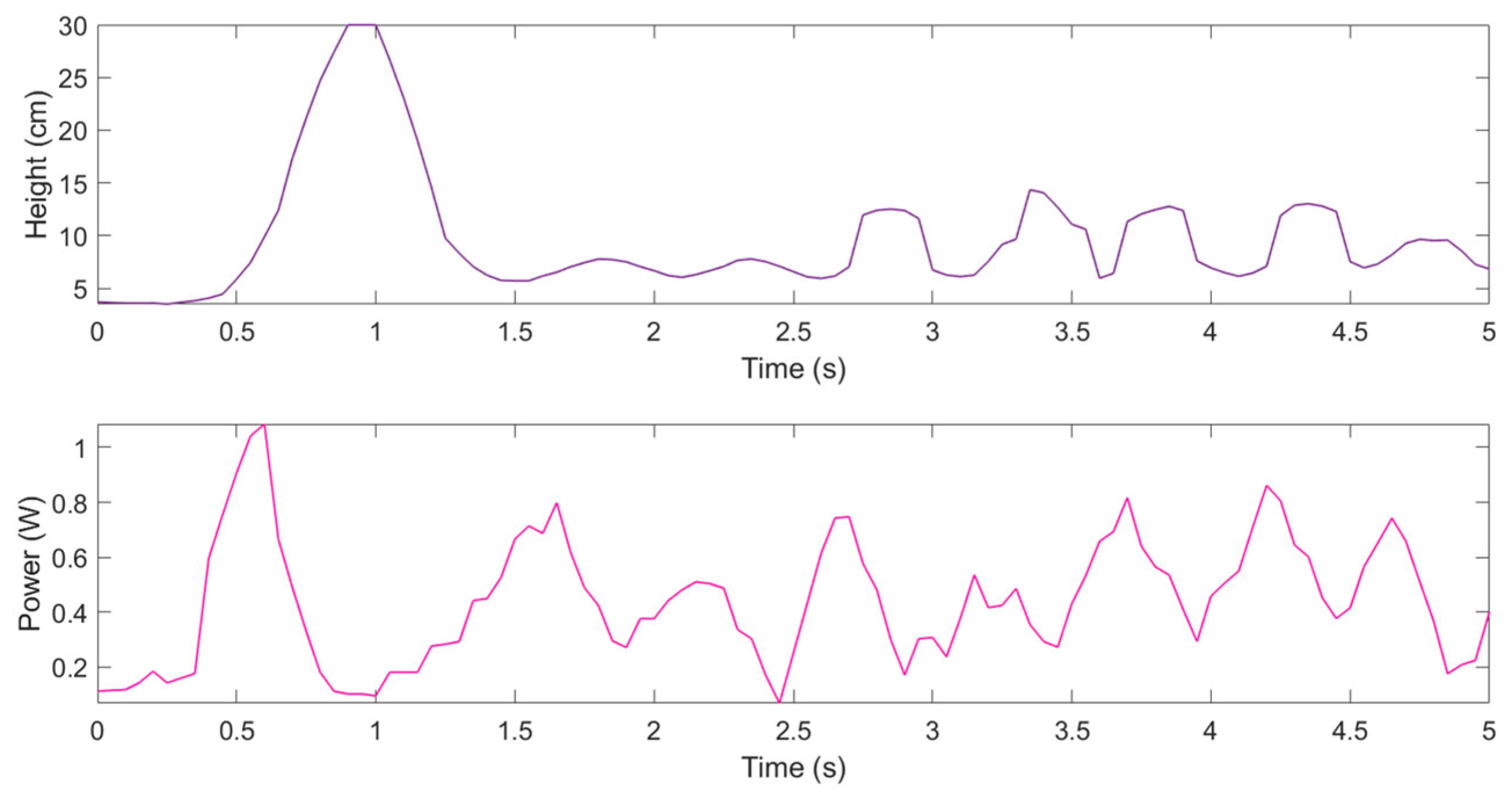

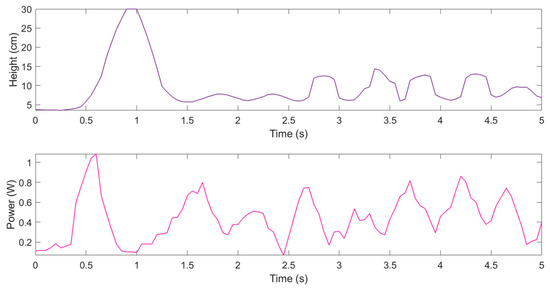

By applying the PID controller, the model exhibited the behavior represented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Height (purple graph) and power responses (pink graph) of the drone model controlled by the PID controller.

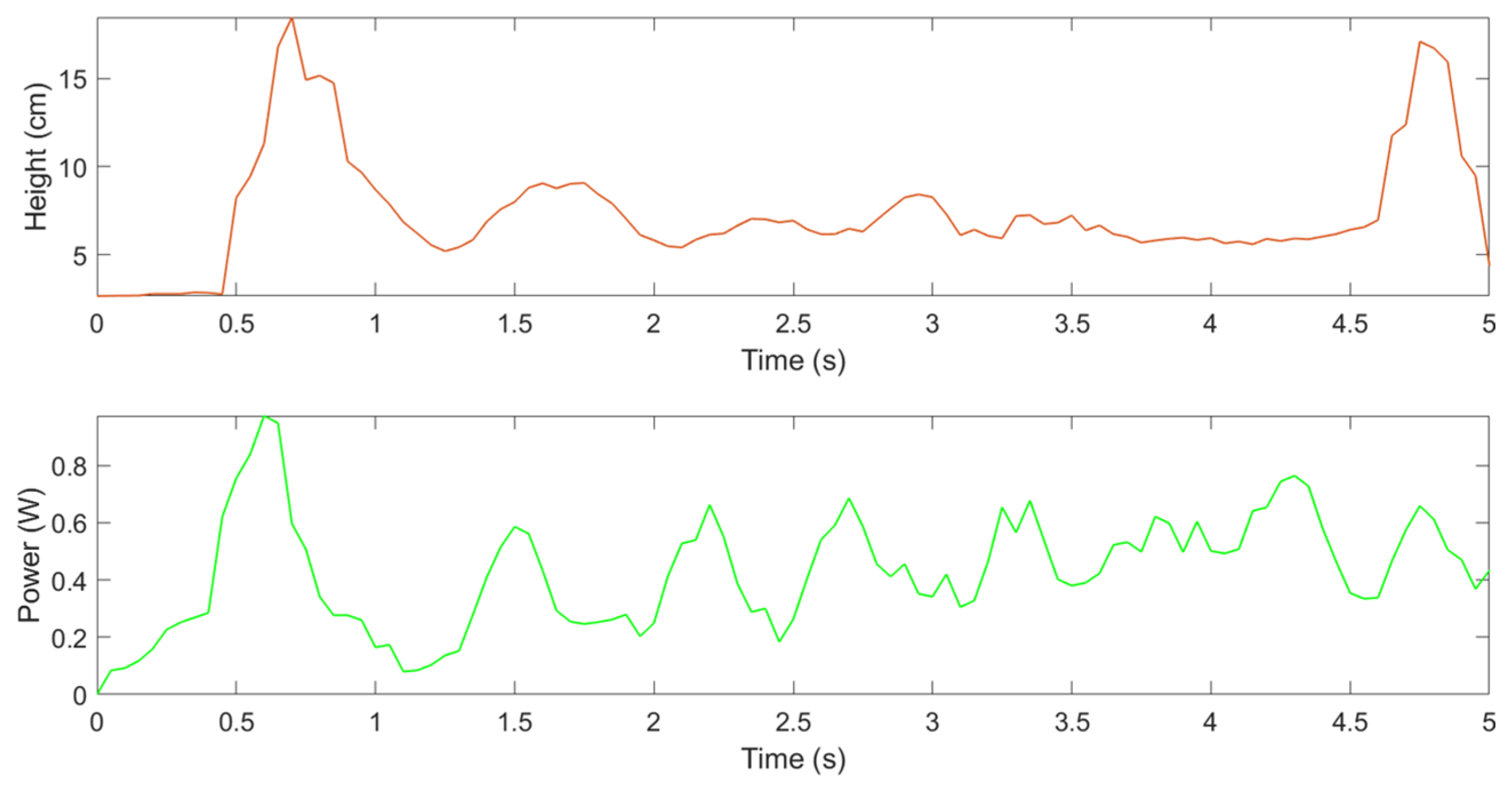

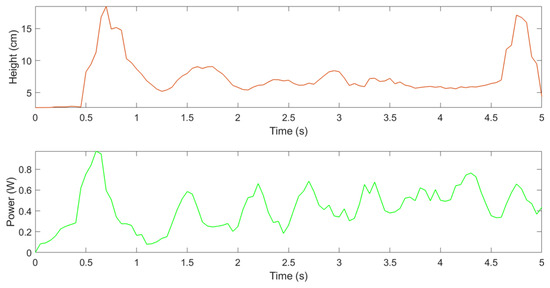

With the PID controller, the drone ascended to 30 cm within 1 s, showing significant overshoot. Subsequently, the altitude oscillated between 6 cm and 14 cm. The power consumption initially reached 1 W, and the average power was measured as 0.47 W. With the MPC (Figure 4), the drone reached 18.45 cm at 0.7 s, and from 1.25 to 4.6 s, stable hovering was observed between 5.416 cm and 9.072 cm. After a brief peak at 17.046 cm, the system quickly returned to a lower level. The initial power consumption of the MPC was 0.95 W, which is 5% lower than that of the PID controller. Between 1 and 5 s, the power varied between 0.1 W and 0.764 W. The average power consumption was 0.37 W, representing a 21% reduction compared to the PID controller.

Figure 4.

Height (brown graph) and power responses (green graph) of the drone model controlled by the MPC.

A 4% difference was observed between the simulation and the practical test results (25% vs. 21% savings), confirming the reliability of the model.

With the MPC, more stable hovering and lower energy consumption were achieved, while the PID controller resulted in larger oscillations, higher peak power, and longer stabilization time. Therefore, the MPC proved to be a more favorable choice even in a disturbance-prone environment.

5. Proposal for Improving the Energy Efficiency of the PID Controller

One of the disadvantages of classical PID control is that the control parameters are fixed, preventing the system from adapting to environmental changes and disturbances. To address this issue, a Gain Scheduling PID controller was proposed, in which the PID gains are adjusted according to the noise level [20].

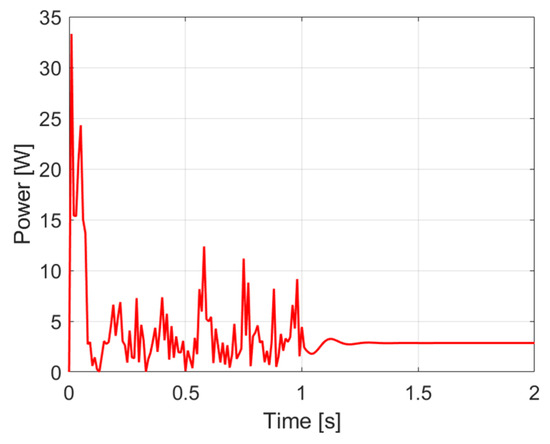

According to Figure 5, the peak power of the GS-PID controller was measured at 33.3 W, compared to 68.99 W with the classical PID. The average power consumption was 3.59 W, while for the classical PID it was 4.18 W, representing a 14% reduction. The steady-state was reached in 0.23 s with GS-PID, while the PID required 0.32 s.

Figure 5.

Performance curve of the GS-PID controller in simulation analysis.

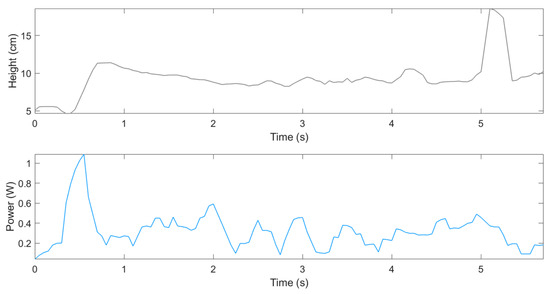

In the practical implementation shown in Figure 6, an initial overshoot of 11.39 cm was observed during hovering, compared to the 30 cm overshoot seen with the classical PID (Figure 3). The drone then maintained a stable altitude around 10 cm, followed by a peak of 18.56 cm, which still remained below the maximum value achieved by the PID controller. The average power consumption was 0.33 W, in contrast to 0.47 W with PID, resulting in a 30% improvement.

Figure 6.

Practically implemented quadcopter altitude (gray) and power curve (light blue) using GS-PID control.

During the practical tests, the power consumption of the MPC was measured at 0.37 W, meaning the GS-PID fell behind by 11%, but still closely approached the energy efficiency of the MPC.

In summary, the GS-PID controller enabled more efficient operation under noisy conditions, ensuring more stable hovering and lower energy consumption compared to the classical PID controller.

6. Summary of Results

The energy efficiency of the control strategies examined in this study was evaluated under both simulation and practical conditions. The MPC was found to be the most efficient, while the GS-PID controller showed significant improvement compared to the classical PID.

In simulation, the GS-PID controller consumed 3.59 W on average (Table 1), and in practical tests, 0.33 W, closely approaching the efficiency of the MPC.

Table 1.

Comparison of controller performance based on simulation and practical experiments.

In simulation, a 14% reduction in energy consumption was achieved by the GS-PID controller, while in practical experiments, this improvement increased to 30%. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of controller performance improvement relative to classical pid in simulation and practical experiments.

With the GS-PID controller, an oscillation of 3 cm was recorded, which was lower than both the PID (9 cm) and the MPC (4 cm) results. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of the oscillation characteristics of controllers during drone hovering in the approximate steady-state phase.

In summary, the MPC was found to deliver the best performance in terms of energy efficiency and stability. However, the GS-PID controller also demonstrated significant improvements. With the GS-PID method, not only was energy consumption reduced, but oscillations were minimized. Based on these findings, the GS-PID approach can be considered an effective alternative in systems where MPC implementation is not feasible.

7. Conclusions

In this study, the performance of control strategies was evaluated, where the MPC achieved the most favorable energy efficiency and stability, while the GS-PID controller also demonstrated significant improvements in reducing energy consumption and oscillations. The results were supported by practical measurements, and further investigations of the controllers are planned to be conducted on a real industrial drone platform.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.K., Á.B. and M.K.; methodology, B.K.; software, B.K.; validation, Á.B. and M.K.; formal analysis, B.K.; investigation, B.K.; resources, B.K.; data curation, B.K.; writing—original draft preparation, B.K.; writing—review and editing, B.K.; visualization, B.K.; supervision, Á.B. and M.K.; project administration, B.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication was created in the framework of the Széchenyi István University’s VHFO/416/2023-EM_SZERZ project entitled. Preparation of digital and self-driving environmental infrastructure developments and related research to reduce carbon emissions and environmental impact” (Green Traffic Cloud).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hafeez, A.; Husain, M.A.; Singh, S.P.; Chauhan, A.; Khan, M.T.; Kumar, N.; Soni, S.K. Implementation of drone technology for farm monitoring & pesticide spraying: A review. Inf. Process. Agric. 2023, 10, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, B.; Ballagi, Á.; Kuczmann, M. Overview Study of the Applications of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in the Transportation Sector. Eng. Proc. 2024, 79, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, A.; James, A.; Kuantama, E.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Han, R. Drone high-rise aerial delivery with vertical grid screening. Drones 2023, 7, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, M.L. Smart Drone Surveillance System Based on AI and on IoT Communication in Case of Intrusion and Fire Accident. Drones 2023, 7, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuhne, D.; Vasiljević, G.; Bogdan, S.; Kovačić, Z. Design and Validation of a Wireless Drone Docking Station. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Warsaw, Poland, 6–9 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, P.; Hiba, A.; Nagy, M.; Simonyi, E.; Kuna, G.I.; Kisari, Á.; Zarándy, Á. Encounter Risk Evaluation with a Forerunner UAV. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, H.; Weckman, G.R. Working under the Shadow of Drones: Investigating Occupational Safety Hazards among Commercial Drone Pilots. IISE Trans. Occup. Ergon. Hum. Factors 2023, 12, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasri, M.; Maghrebi, M. Factors affecting unmanned aerial vehicles’ safety: A post-occurrence exploratory data analysis of drones’ accidents and incidents in Australia. Saf. Sci. 2021, 139, 105273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Guan, X.; Wang, S. Quantitative ground risk assessment for urban logistical unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) based on bayesian network. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, D.; Di Gennaro, S.; Di Ferdinando, M.; Acosta Lùa, C. Robust control of UAV with disturbances and uncertainty estimation. Machines 2023, 11, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezhil, V.S.; Sriram, B.R.; Vijay, R.C.; Yeshwant, S.; Sabareesh, R.K.; Dakkshesh, G.; Raffik, R. Investigation on PID controller usage on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle for stability control. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 66, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, N.; Marhoon, H.M. Towards evaluation of the PID criteria-based UAVs observation and tracking head within resizable selection by COA algorithm. Results Control. Optim. 2023, 12, 100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amertet, S.; Gebresenbet, G.; Alwan, H.M. Modeling of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for Smart Agriculture Systems Using Hybrid Fuzzy PID Controllers. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Lee, C.S. Research on logistics of intelligent unmanned aerial vehicle integration system. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2023, 36, 100534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmaksoud, S.I.; Mailah, M.; Abdallah, A.M. Control strategies and novel techniques for autonomous rotorcraft unmanned aerial vehicles: A review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 195142–195169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai, S.; Garg, A.; Jhawar, K.; Chamola, V.; Sikdar, B. A comprehensive survey on artificial intelligence for unmanned aerial vehicles. IEEE Open J. Veh. Technol. 2023, 4, 713–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.H.; Ouda, A.N.; Kamel, A.M.; Elhalwagy, Y.Z. Design and analysis of quadcopter classical controller. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Aerospace Sciences and Aviation Technology (ASAT-16), Cairo, Egypt, 26–28 May 2015; The Military Technical College: Cairo, Egypt, 2015; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Say, M.F.Q.; Sybingco, E.; Bandala, A.A.; Vicerra, R.R.P.; Chua, A.Y. A genetic algorithm approach to PID tuning of a quadcopter UAV model. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/SICE International Symposium on System Integration (SII), Iwaki, Japan, 11–14 January 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Model Predictive Control System Design and Implementation Using MATLAB, 3rd ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, A.G.; Andrade, F.A.; Guedes, I.P.; Carvalho, G.F.; Zachi, A.R.; Pinto, M.F. Fuzzy gain-scheduling PID for UAV position and altitude controllers. Sensors 2022, 22, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).