Abstract

This study introduces a comprehensive benchmarking framework for evaluating visual odometry (VO) methods, combining classical, learning-based, and hybrid approaches. We assess 52 configurations—spanning 19 keypoint detectors, 21 descriptors, and 4 matchers—across two widely used benchmark datasets: KITTI and EuRoC. Six key trajectory metrics, including Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE) and Final Displacement Error (FDE), provide a detailed performance comparison under various environmental conditions, such as motion blur, occlusions, and dynamic lighting. Our results highlight the critical role of feature matchers, with the LightGlue–SIFT combination consistently outperforming others across both datasets. Additionally, learning-based matchers can be integrated with classical pipelines, improving robustness without requiring end-to-end training. Hybrid configurations combining classical detectors with learned components offer a balanced trade-off between accuracy, robustness, and computational efficiency, making them suitable for real-world applications in autonomous systems and robotics.

1. Introduction

Visual odometry (VO) is a fundamental technique for estimating a moving camera’s position and orientation from image sequences alone. It plays a crucial role in scenarios where traditional localization methods like GPS are unavailable or unreliable—such as indoor environments, underground tunnels, or underwater areas [1]. Since its introduction in the 1980s through optical flow techniques, significant progress has been achieved, including real-time applications such as the Mars Exploration Rovers [2,3].

Classical VO methods rely on geometric tracking of keypoints, whereas learning-based approaches use deep neural networks to extract motion directly from visual data [4]. Hybrid methods aim to combine the strengths of both, balancing efficiency and robustness. While learning-based VO offers greater adaptability, it also requires large datasets and high computational resources, especially in diverse or unseen domains.

Despite ongoing advances, VO systems remain sensitive to factors such as motion blur, lighting changes, sensor noise, and dynamic objects [5]. This study presents a systematic and comprehensive comparison of classical and learning-based VO configurations, focusing on accuracy, runtime, and computational efficiency under controlled experimental conditions.

2. Related Work

Interest in comparative analysis of visual odometry (VO) techniques has grown alongside the increasing deployment of SLAM systems and autonomous platforms [1,4,6]. Early VO methods were grounded in optical flow, with the Lucas–Kanade (LK) algorithm [7] serving as a foundational approach in frame-to-frame motion estimation.

Classical VO pipelines typically involve keypoint detection through algorithms such as SIFT [8], ORB [9], BRISK [10], AKAZE [11], or KAZE [12]; description via BRIEF [13], FREAK [14], RootSIFT [15], or BEBLID [16]; and matching using Brute-Force [17] or FLANN [18]. These methods are known for their interpretability and computational efficiency, although their performance can degrade under complex environmental conditions.

Learning-based approaches have introduced convolutional neural networks to extract and match features directly from raw image data. Models such as SuperPoint [19], D2-Net [20], ALIKED [21], R2D2 [22], LF-Net [23], DISK [24], ContextDesc [25] and KeyNet [26] have demonstrated significant improvements in robustness and generalization. Recently, LightGlue [27] has been proposed as an attention-based, context-aware matcher, capable of leveraging global relationships across features.

Hybrid methods pair classical detectors with learned descriptors or matchers. For instance, configurations such as ORB2_HardNet [9,28] and ORB2_SOSNet [9,29] pair traditional feature extraction with modern learned representations.

Although prior research has introduced and evaluated individual methods, broad comparisons that span classical, learned, and hybrid VO pipelines remain scarce. The present study addresses this limitation by systematically evaluating 52 representative configurations using a unified framework implemented in PySLAM [5]. Emphasis is placed on evaluating accuracy and robustness across diverse environments.

3. Materials and Methods

All experiments were conducted using the PySLAM (commit 9c20866) framework [5], which allows modular assembly of visual odometry (VO) pipelines. Keypoint detectors, descriptors, and matchers were flexibly combined into 52 distinct configurations. For each setup, trajectory estimation was carried out and performance was evaluated using six quantitative metrics. The modular structure of PySLAM ensured consistent benchmarking and reproducibility across all configurations.

3.1. Configurations

The evaluated VO pipelines were categorized into four groups, based on the nature of their components:

Classical configurations relied entirely on handcrafted modules. Keypoints were extracted using detectors such as SIFT [8], ORB [9], BRISK [10], or AKAZE [11], described with BRIEF [13], FREAK [14], RootSIFT [15], or BEBLID [16], and matched using either Brute-Force [17] or FLANN [18].

Learning-based configurations utilized deep networks for feature extraction and description. Representative models include SuperPoint [19], D2-Net [20], ALIKED [21], R2D2 [22], LF-Net [23], and DISK [24].

Hybrid configurations combined classical detectors with learned components. Examples include ORB2_HardNet [9,26] and ORB2_SOSNet [9,27], which replace handcrafted descriptors with learned ones.

LightGlue-based configurations employed the LightGlue matcher [25] in combination with classical (e.g., SIFT, ALIKED) or learned descriptors (e.g., SuperPoint). LightGlue, with its transformer-based architecture and context-aware matching, offers unique advantages that distinguish it from other hybrid configurations.

Despite integrating both classical and learned components, its approach to matching is significantly different, justifying its treatment as a distinct category in this study.

A detailed list of all 52 configurations—covering detector–descriptor–matcher pairings, grouping assignments, and per-configuration metrics—is available in our public GitHub repository (see Data Availability Statement). Additionally, the repository contains the full source code, configuration files, and instructions to replicate the experiments on different benchmark datasets, ensuring transparency and reproducibility of the results.

3.2. Datasets

Two publicly available datasets were selected to evaluate the VO configurations under diverse environmental conditions:

KITTI [30,31] provides urban driving scenarios with synchronized grayscale stereo images and ground truth poses derived from GPS and IMU sensors. Its realistic outdoor settings, dynamic objects, and long-range trajectories make it a standard benchmark for evaluating vehicle-based VO systems under large-scale, structured conditions.

EuRoC [32] is designed for micro aerial vehicle (MAV) applications and comprises indoor sequences captured by a stereo camera, with ground truth provided via a Vicon motion capture system. The dataset features rapid camera motion, low-texture surfaces, and challenging lighting conditions, thereby enabling robustness testing in confined or cluttered environments.

The two datasets cover contrasting conditions, providing a broad basis for VO evaluation.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

To measure VO performance, six commonly used trajectory-based metrics were applied [6,10]. Let and denote the estimated and ground truth positions at frame , respectively, over a sequence of frames:

Absolute Trajectory Error: Measures the overall deviation from the gt trajectory.

Mean Absolute Error: Computes the average absolute deviation across the sequence.

Mean Squared Error: Penalizes larger errors by squaring the distances.

Mean Relative Error: Normalizes error by the magnitude of the gt positions.

Relative Pose Error: Captures frame-to-frame drift.

Final Displacement Error: Measures the final position difference.

All metrics were calculated using external Python (version 3.11.9) scripts and were saved in CSV format for further statistical and graphical analysis.

4. Results

This section presents the evaluation results on the KITTI and EuRoC datasets using six performance metrics. Configurations were ranked individually for each metric. The final ranking was determined by computing the average rank across all metrics, resulting in a single aggregated performance score for each configuration. Lower aggregated ranks indicate better overall performance. The discussion focuses on top-performing configurations, with occasional reference to poorly performing ones.

All relevant information is publicly available on the GitHub repository, including the trajectory estimation text files (over 1000 files) for each run, the evaluation and execution scripts, and the detailed metrics. These metrics are provided for each configuration-sequence pairing as well as averaged across all sequences. Due to space constraints in the paper, only the average results are presented.

4.1. KITTI

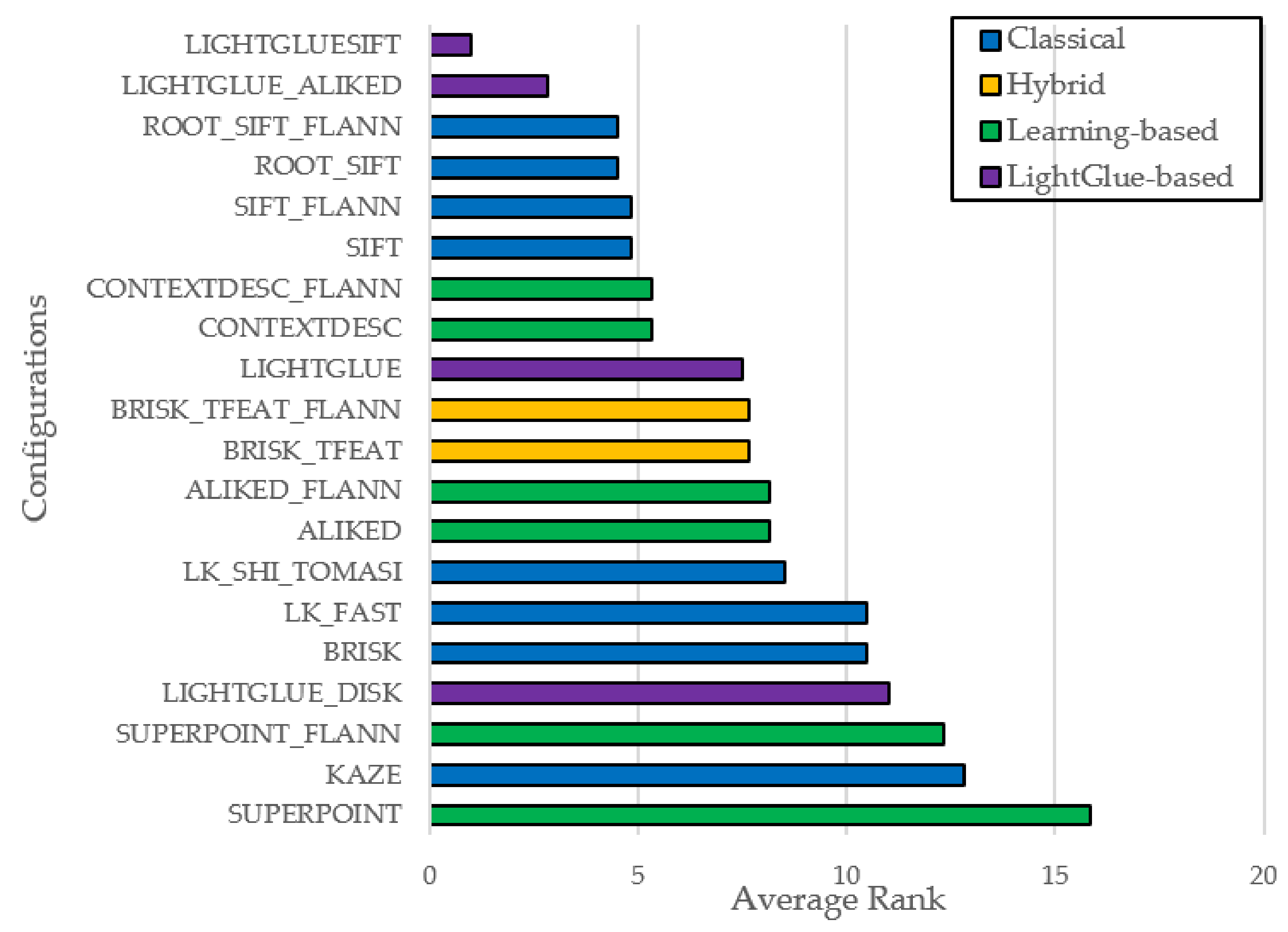

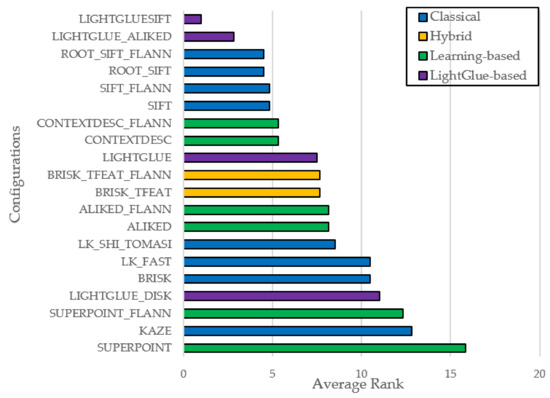

In the KITTI dataset, a broad range of performance was seen across VO configurations. Figure 1 shows the top-20 configurations, where LightGlue-based pipelines consistently ranked highest, with LIGHTGLUESIFT and LIGHTGLUE_ALIKED leading overall. These setups show that LightGlue effectively leverages classical descriptors like SIFT and ALIKED, outperforming both traditional and learning-based pipelines. Classical SIFT variants also performed strongly. Configurations such as ROOT_SIFT_FLANN, ROOT_SIFT, SIFT_FLANN, and SIFT followed closely behind LightGlue, confirming SIFT’s reliability under motion blur, scale, and illumination changes. Hybrid approaches like CONTEXTDESC_FLANN and CONTEXTDESC performed well, combining learned descriptors with traditional matching. Similarly, BRISK_TFEAT and BRISK_TFEAT_FLANN were competitive among hybrid methods, especially with robust matching. In contrast, learning-based pipelines like SUPERPOINT and SUPERPOINT_FLANN were generally outperformed by top classical and hybrid methods, though still within acceptable margins. Traditional frame-to-frame methods like LK_FAST and LK_SHI_TOMASI had moderate accuracy, while other classical pipelines—especially KAZE, BRISK, or ORB2—showed more drift and lower rankings.

Figure 1.

Top 20 VO Configuration (KITTI).

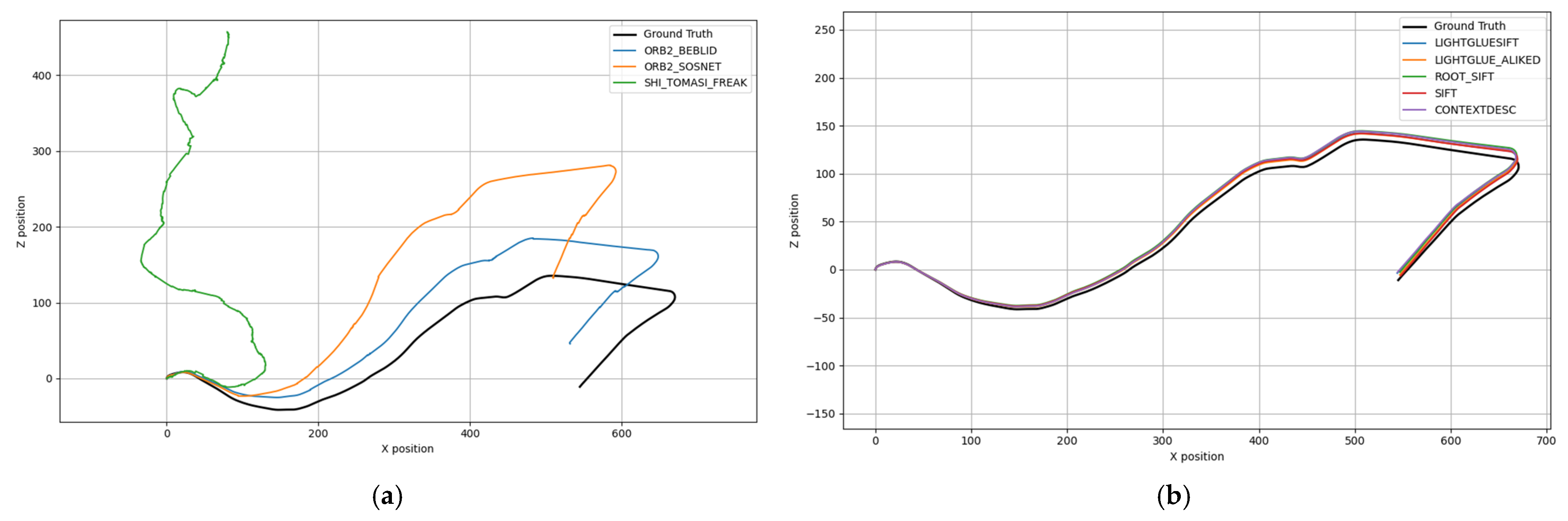

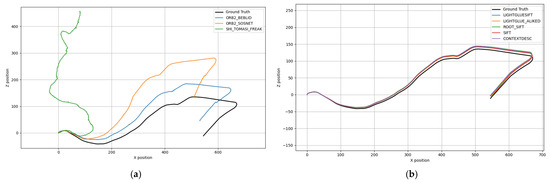

To illustrate the extremes of visual odometry performance, qualitative trajectory plots for Sequence 10 of the KITTI dataset are shown in Figure 2, comparing high-performing and poor-performing configurations.

Figure 2.

(a) Trajectories from low-performing configurations; (b) trajectories from top-performing configurations.

Left (Figure 2a): Underperforming methods show significant drift, with SHI_TOMASI_FREAK diverging drastically from the ground truth.

Right (Figure 2b): Top-performing configurations, including LIGHTGLUESIFT, LIGHTGLUE_ALIKED, ROOT_SIFT, SIFT, and CONTEXTDESC closely follow the ground truth, demonstrating stable motion estimation throughout the sequence.

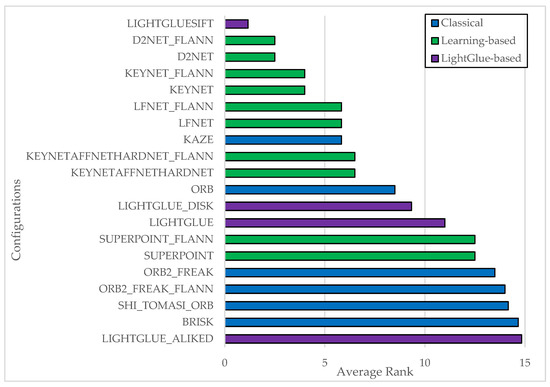

4.2. EuRoC

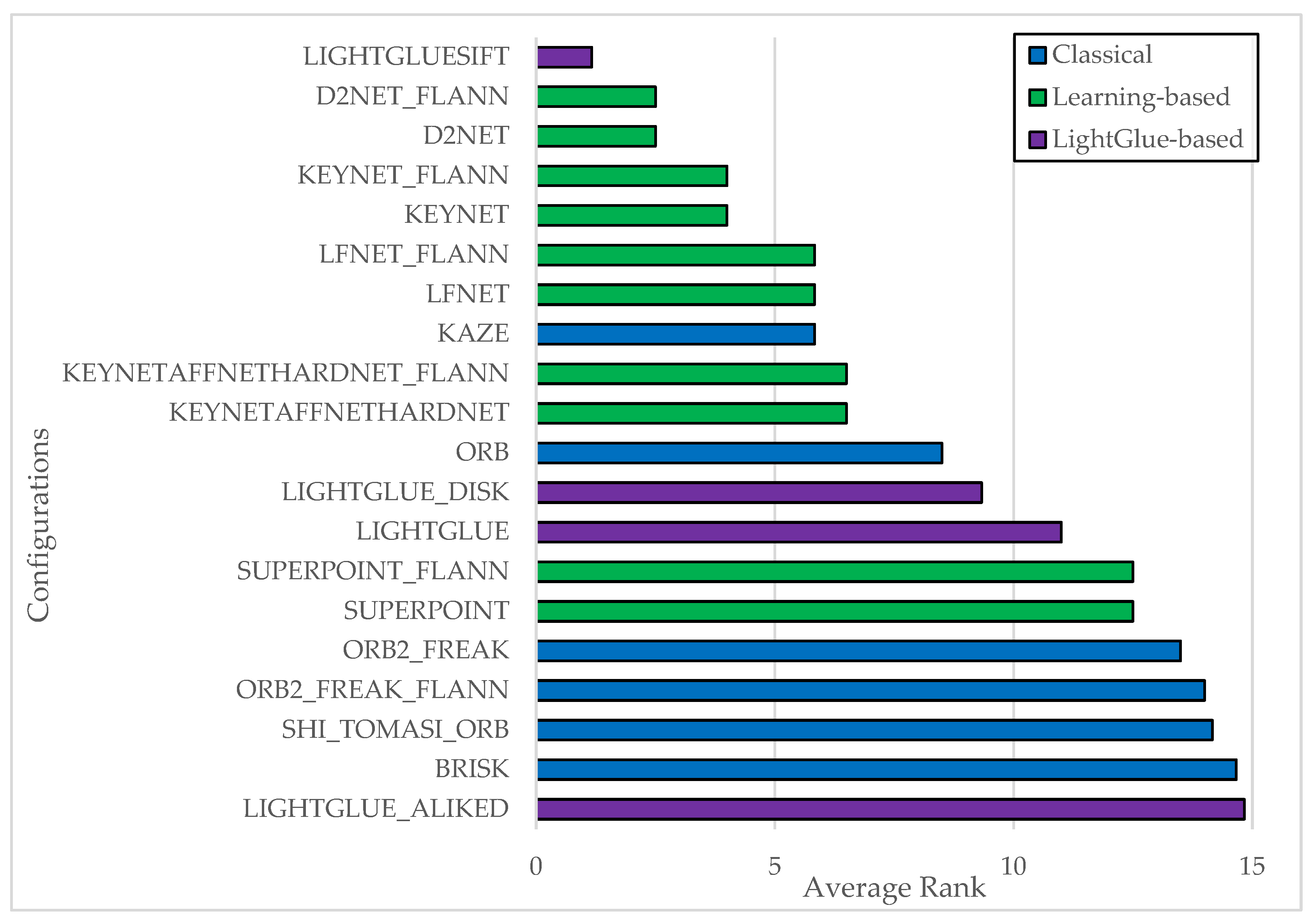

The EuRoC dataset presents a markedly different challenge, with indoor sequences characterized by rapid motion, low-texture environments, and varying illumination. Within this context, the LIGHTGLUESIFT configuration once again achieved the highest ranking, as shown in Figure 3, demonstrating strong generalization across both outdoor and indoor scenarios.

Figure 3.

Top 20 VO Configuration (EuRoC).

Learning-based configurations—notably those involving D2Net, KeyNet, and LFNet—also performed exceptionally well, regardless of whether Brute-Force or FLANN matching was used. These results suggest that learned features are particularly well-suited to the visual complexities of indoor scenes, where classical feature extractors often struggle due to lack of texture or lighting irregularities.

LightGlue and LightGlue_DISK configurations were positioned in the mid-range of the ranking. While their performance did not match that of combinations with robust handcrafted descriptors such as SIFT or ALIKED, they nonetheless exhibited stability and robustness across sequences. In contrast, configurations employing ALIKED and BRISK consistently ranked near the bottom, indicating limited adaptability to EuRoC’s conditions.

SUPERPOINT-based approaches delivered moderate performance—superior to many classical configurations, but generally outperformed by specialized learning-based and LightGlue-enhanced pipelines. This outcome suggests that SuperPoint is more effective in structured outdoor environments, while its performance degrades under more complex indoor conditions.

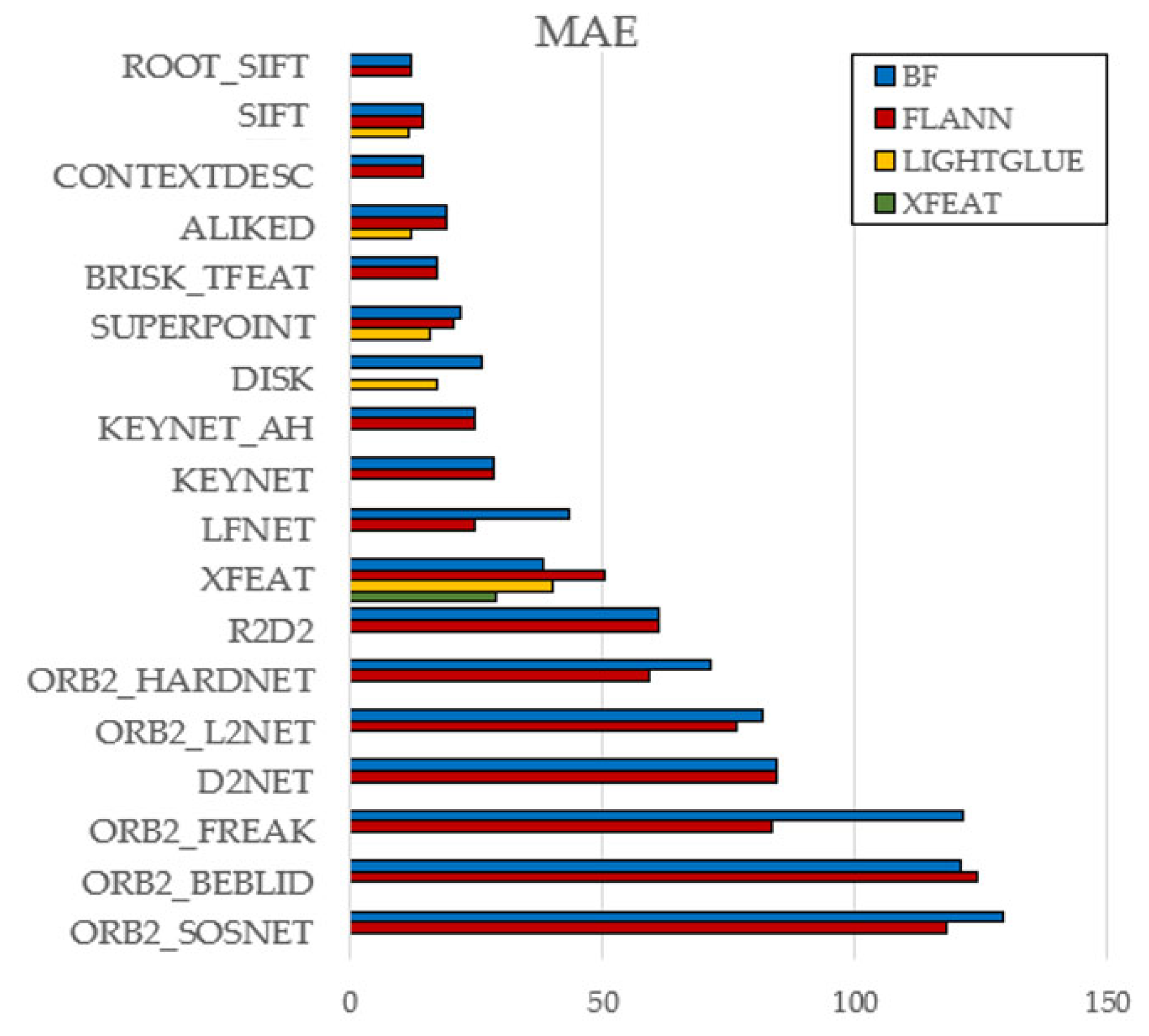

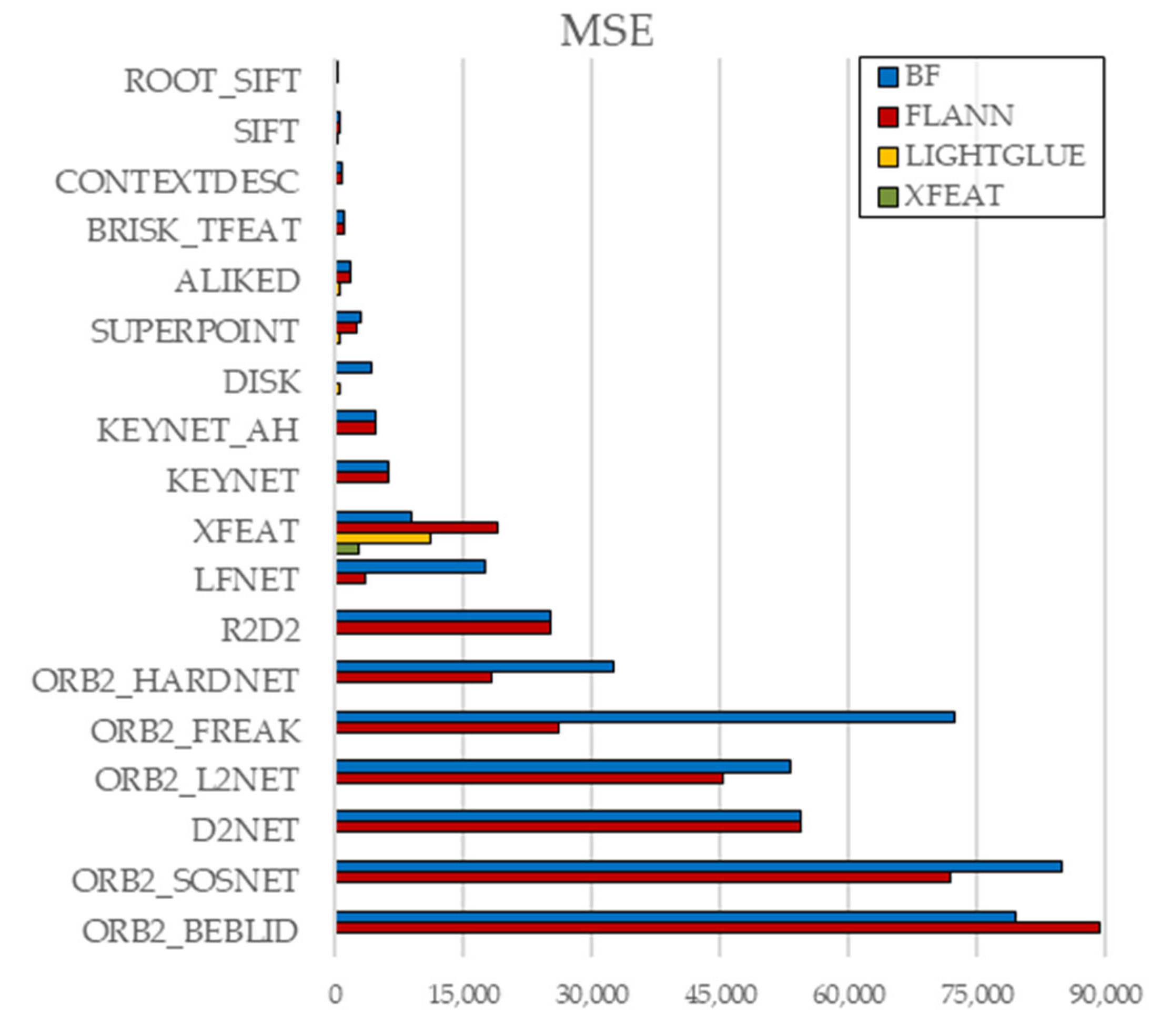

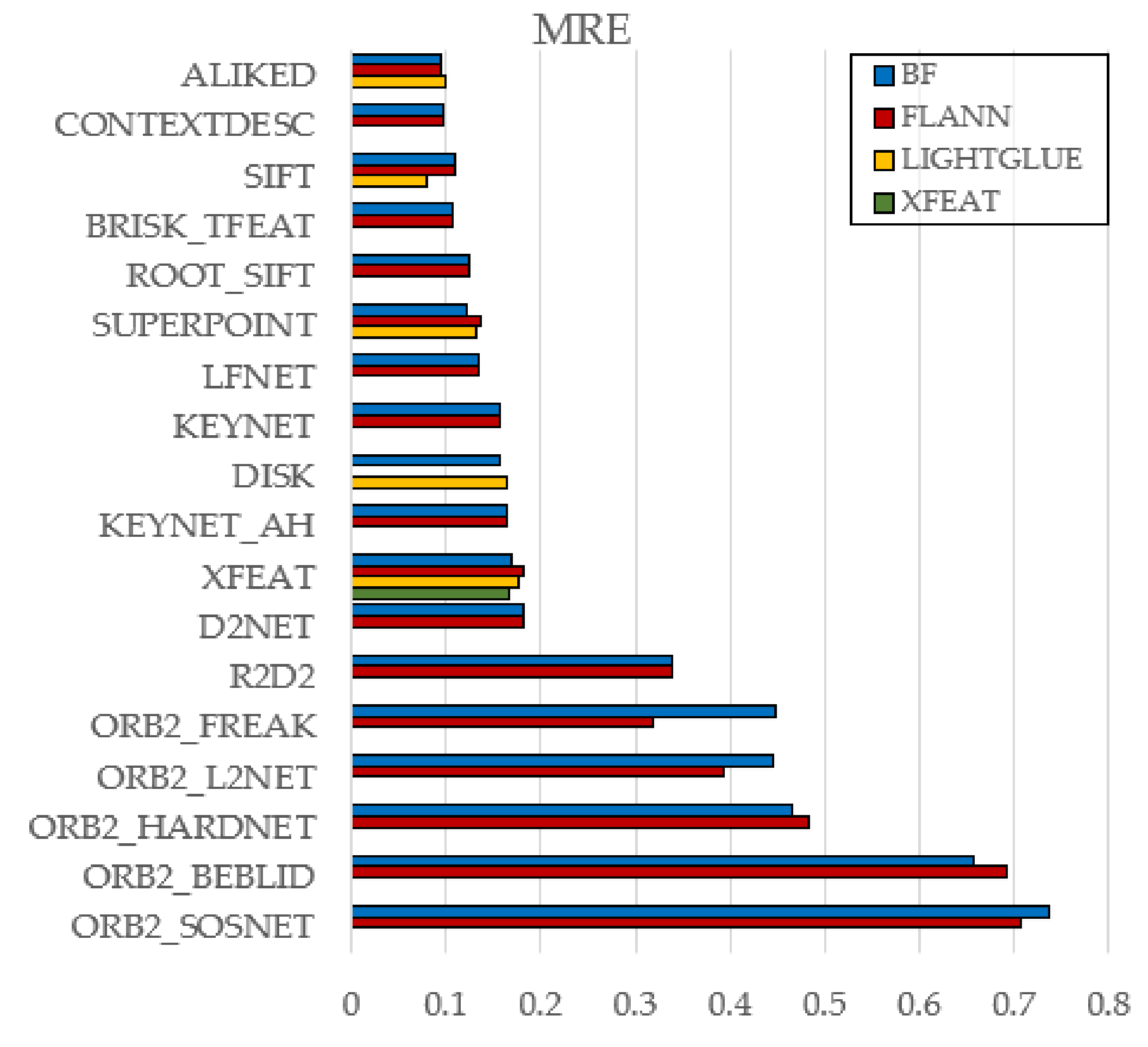

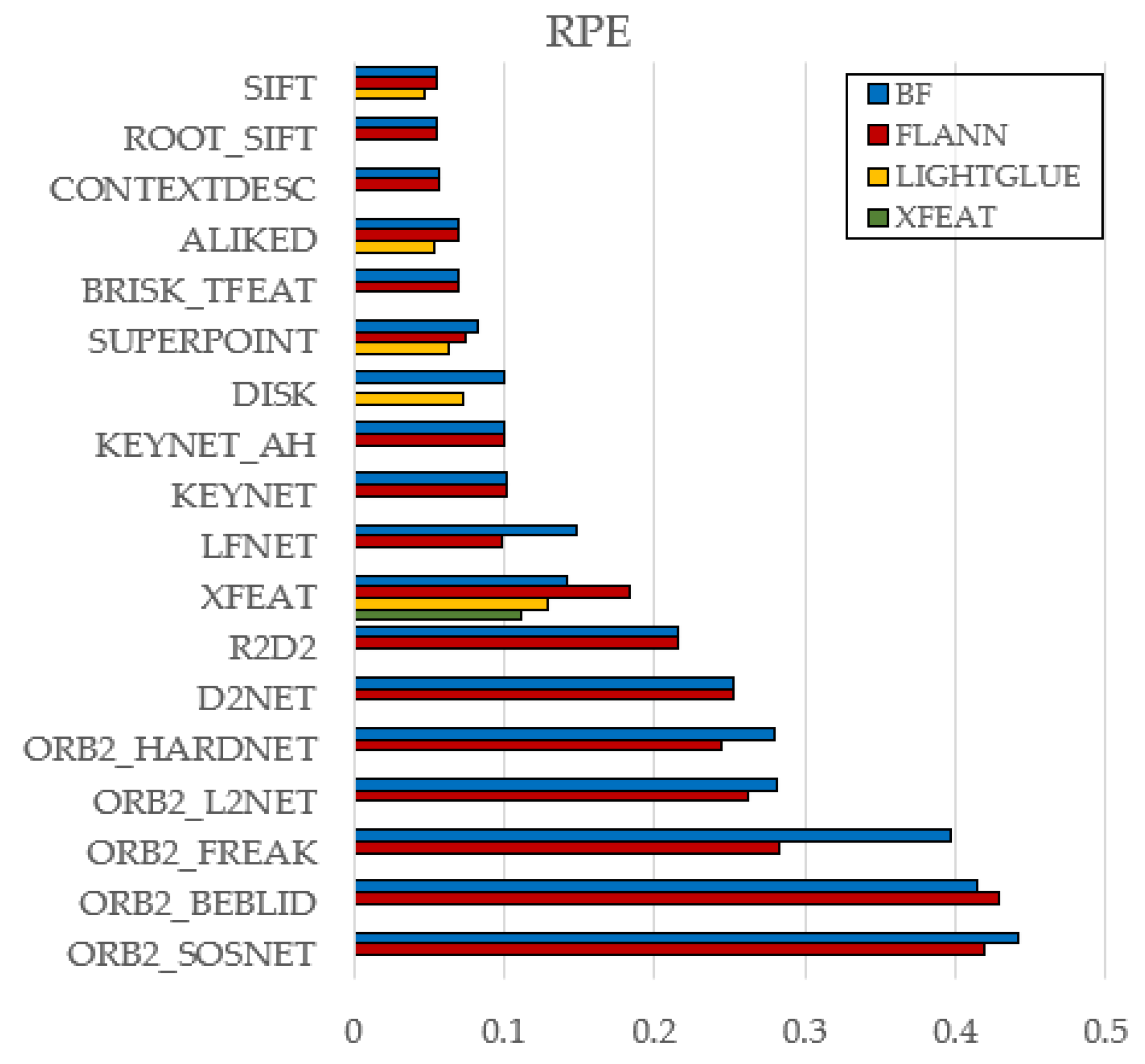

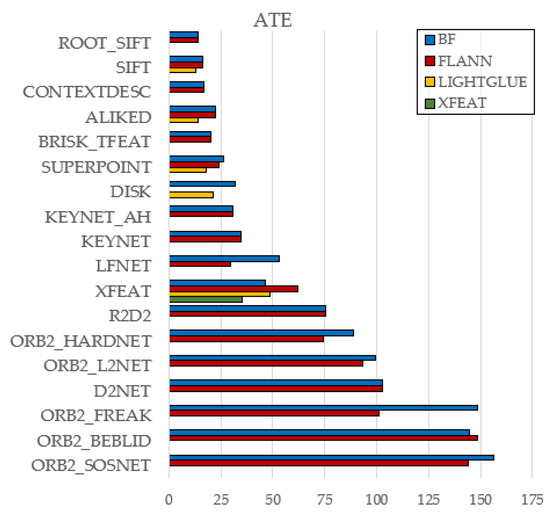

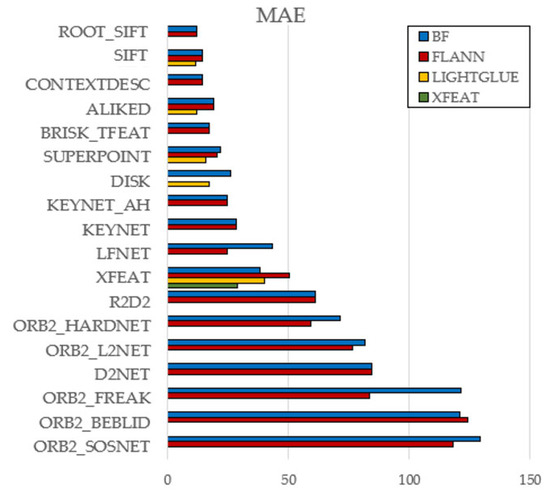

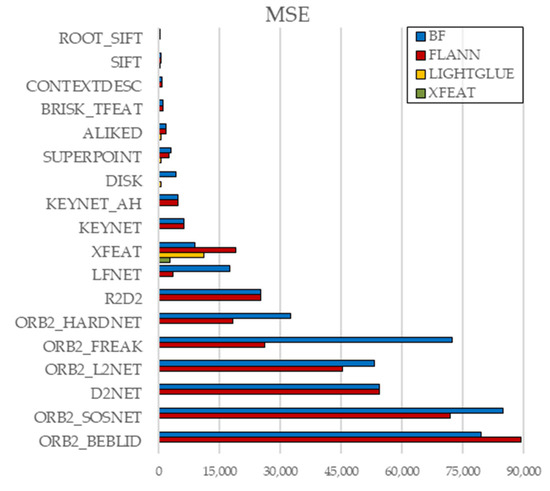

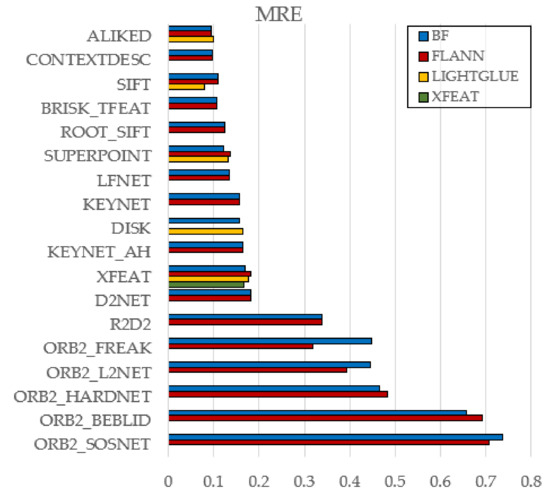

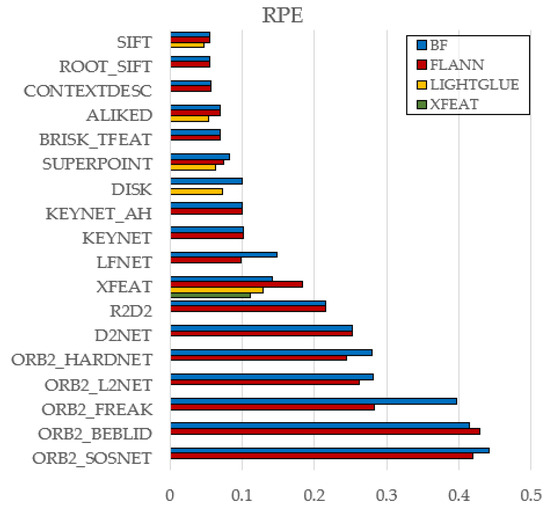

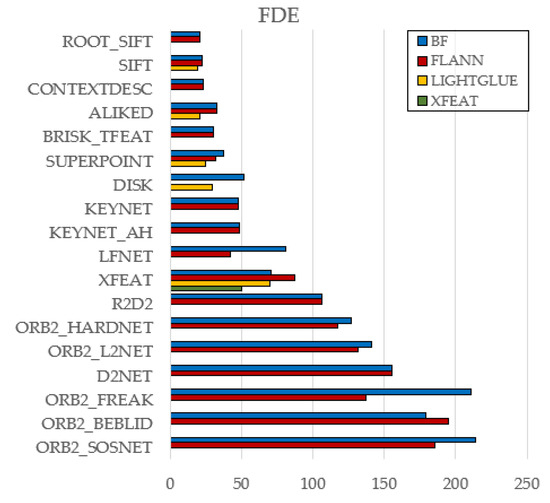

4.3. The Impact of Feature Matchers on Localization Accuracy

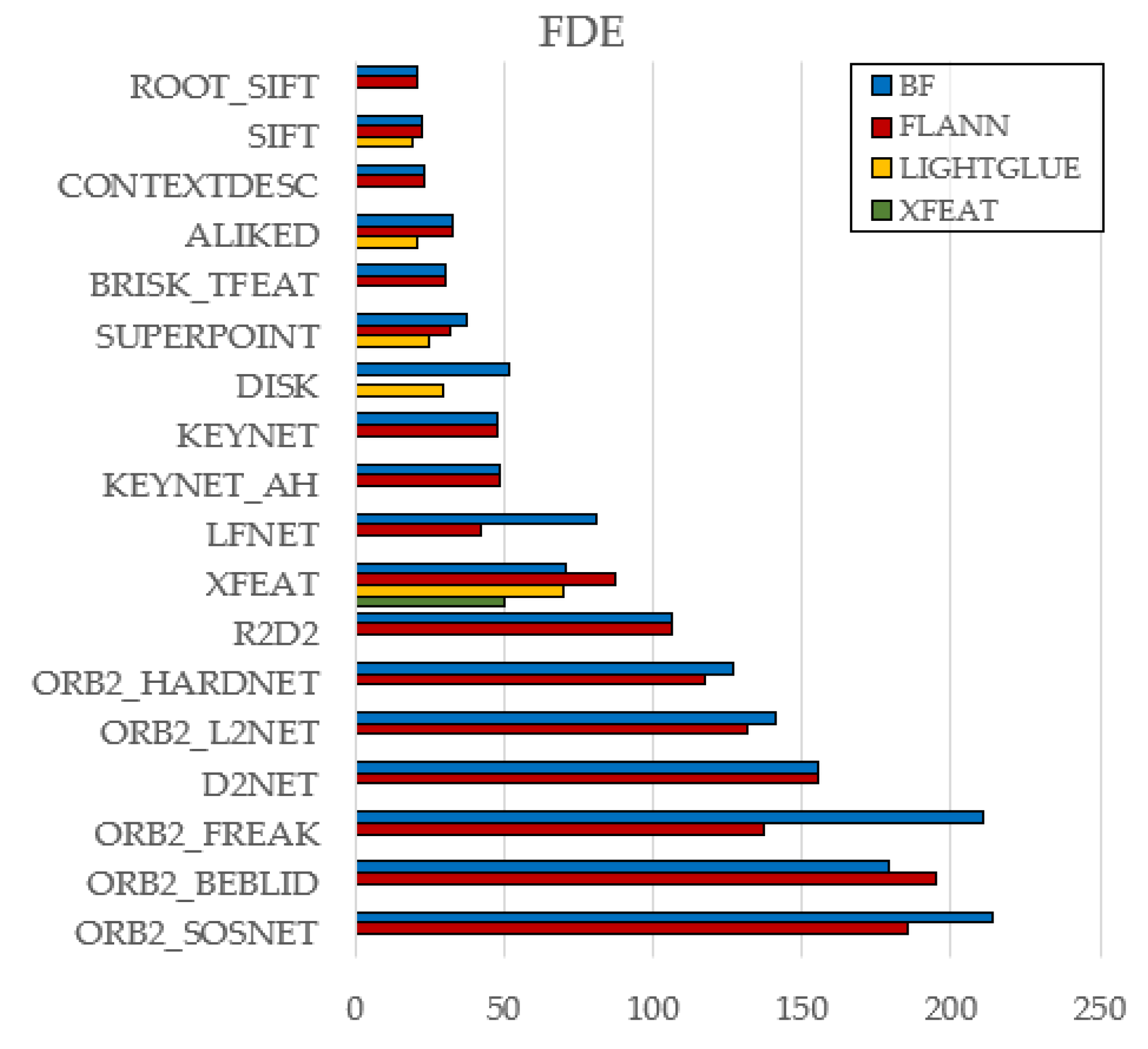

To isolate the effect of feature matchers, the analysis focuses on the KITTI dataset, whose long and varied trajectories are well suited for highlighting differences. All six evaluation metrics (ATE, MAE, MSE, MRE, RPE, FDE) are considered, and their results are visualized in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9. Full results for both datasets are available in the public GitHub repository.

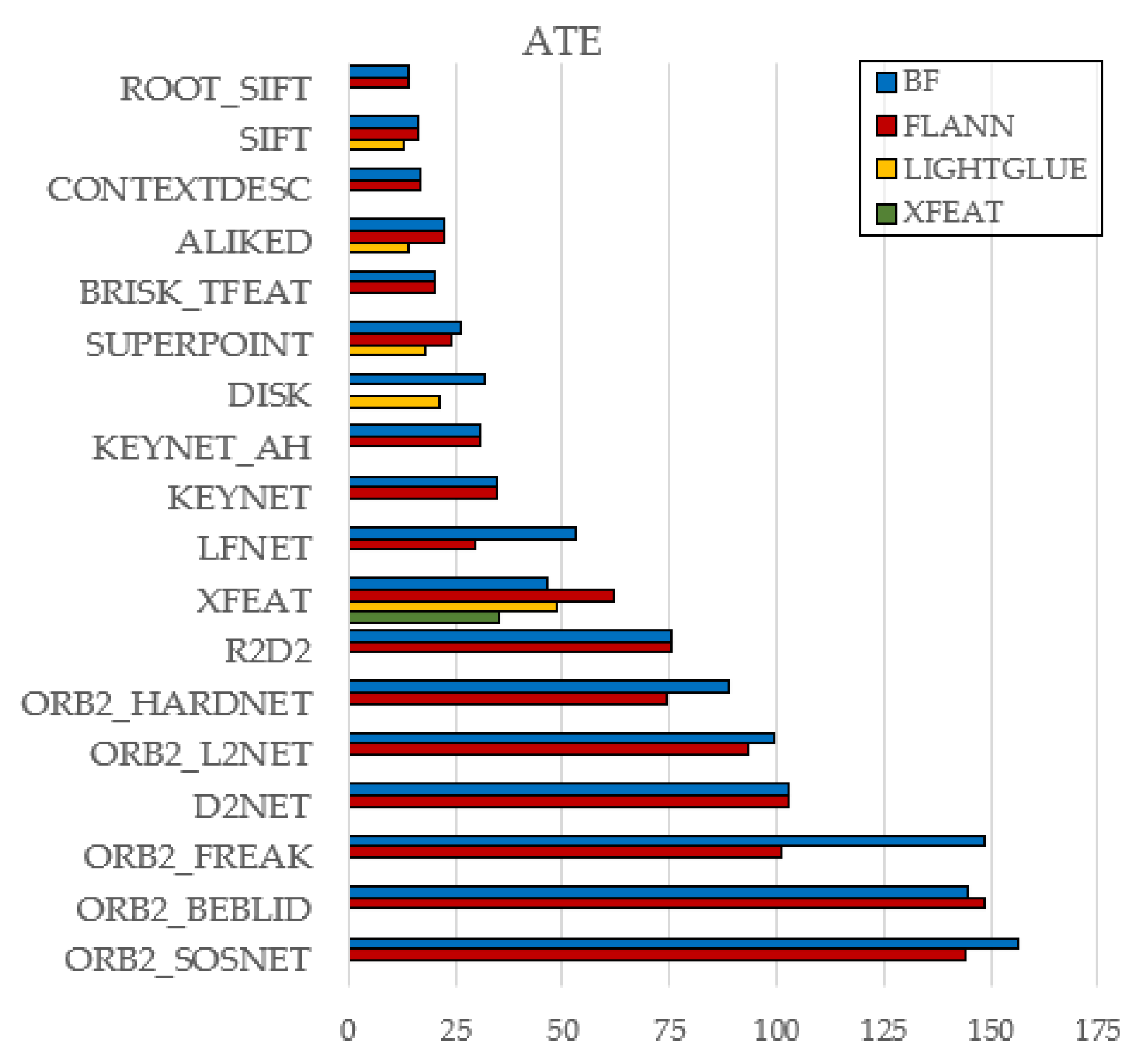

Figure 4.

Effect of Matcher Type on ATE (KITTI).

Figure 5.

Effect of Matcher Type on MAE (KITTI).

Figure 6.

Effect of Matcher Type on MSE (KITTI).

Figure 7.

Effect of Matcher Type on MRE (KITTI).

Figure 8.

Effect of Matcher Type on RPE (KITTI).

Figure 9.

Effect of Matcher Type on FDE (KITTI).

Brute-Force (BF) and FLANN yielded nearly identical results overall, indicating that FLANN’s approximation rarely affects accuracy—though a few cases (e.g., ORB2_FREAK, LFNet) showed BF underperformance.

LightGlue consistently outperformed BF and FLANN across classical (e.g., SIFT) and learned (e.g., ALIKED, DISK) descriptors, suggesting stronger robustness to geometric and photometric variations.

A single exception was found in XFEAT, where its native matcher slightly surpassed LightGlue. Given the system’s tight integration, it is treated as a special case.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This study introduced a comprehensive benchmarking framework to evaluate 52 visual odometry (VO) configurations, spanning classical, hybrid, and deep learning-based approaches. The results emphasize the significant impact of feature matchers on system performance, particularly under diverse environmental conditions. The LightGlue–SIFT combination emerged as a top performer, consistently ranking highly across both the KITTI and EuRoC datasets, positioning it as a promising foundation for future VO systems. Furthermore, the analysis revealed that modern learning-based matchers can be integrated into classical detector–descriptor pipelines without the need for full end-to-end training. This modular approach is highly applicable for real-world deployments.

Future work will focus on expanding the system to handle stereo input, optimizing runtime performance for real-time applications, and testing robustness in more complex environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and A.N.; methodology, A.N.; software, A.N.; validation, A.N.; formal analysis, A.N.; investigation, A.N.; resources, A.N.; data curation, A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.N.; writing—review and editing, J.H.; visualization, A.N.; supervision, J.H.; project administration, J.H.; funding acquisition, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the European Union within the framework of the National Laboratory for Artificial Intelligence (RRF-2.3.1-21-2022-00004).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available on GitHub at https://github.com/nagyarmand/visual-odometry-benchmarking (accessed on 7 July 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Scaramuzza, D.; Fraundorfer, F. Visual Odometry [Tutorial]. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2011, 18, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravec, H. Obstacle Avoidance and Navigation in the Real World by a Seeing Robot Rover. Ph.D. Thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Maimone, M.; Cheng, Y.; Matthies, L. Two Years of Visual Odometry on the Mars Exploration Rovers. J. Field Robot. 2007, 24, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena, C.; Carlone, L.; Carrillo, H.; Latif, Y.; Scaramuzza, D.; Neira, J.; Reid, I.; Leonard, J.J. Past, present, and future of simultaneous localization and mapping: Toward the robust-perception age. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2016, 32, 1309–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freda, L. pySLAM: An Open-Source, Modular, and Extensible Framework for SLAM. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2502.11955. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, G.; Tian, G.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Li, J. A Survey of Visual SLAM Based on Deep Learning. Robot 2017, 39, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, B.D.; Kanade, T. An iterative image registration technique with an application to stereo vision. In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 August 1981; pp. 674–679. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive Image Features from Scale-Invariant Keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rublee, E.; Rabaud, V.; Konolige, K.; Bradski, G. ORB: An Efficient Alternative to SIFT or SURF. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Vision, Barcelona, Spain, 6–13 November 2011; pp. 2564–2571. [Google Scholar]

- Leutenegger, S.; Chli, M.; Siegwart, R.Y. BRISK: Binary Robust Invariant Scalable Keypoints. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Vision, Barcelona, Spain, 6–13 November 2011; pp. 2548–2555. [Google Scholar]

- Alcantarilla, P.; Nuevo, J.; Bartoli, A. Fast Explicit Diffusion for Accelerated Features in Nonlinear Scale Spaces. In Proceedings of the 24th British Machine Vision Conference, Bristol, UK, 9–13 September 2013; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Demchev, D.; Volkov, V.; Kazakov, E.; Alcantarilla, P.F.; Sandven, S.; Khmeleva, V. KAZE Features. In Proceedings of the 12th European Conference on Computer Vision, Florence, Italy, 7–13 October 2012; pp. 214–227. [Google Scholar]

- Calonder, M.; Lepetit, V.; Strecha, C.; Fua, P. BRIEF: Binary Robust Independent Elementary Features. In Proceedings of the 11th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV 2010), Heraklion, Greece, 5–11 September 2010; pp. 778–792. [Google Scholar]

- Alahi, A.; Ortiz, R.; Vandergheynst, P. FREAK: Fast Retina Keypoint. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Providence, RI, USA, 16–21 June 2012; pp. 510–517. [Google Scholar]

- Arandjelović, R.; Zisserman, A. Three things everyone should know to improve object retrieval. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Providence, RI, USA, 16–21 June 2012; pp. 2911–2918. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, I.; Sfeir, G.; Buenaposada, J.M.; Baumela, L. BEBLID: Boosted efficient binary local image descriptor. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 2020, 133, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenCV Documentation. cv::BFMatcher Class Reference. Available online: https://docs.opencv.org/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Muja, M.; Lowe, D.G. Scalable nearest neighbor algorithms for high dimensional data. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2014, 26, 2227–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeTone, D.; Malisiewicz, T.; Rabinovich, A. Superpoint: Self-supervised interest point detection and description. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1712.07629. [Google Scholar]

- Dusmanu, M.; Rocco, I.; Pajdla, T.; Pollefeys, M.; Sivic, J.; Torii, A.; Sattler, T. D2-net: A trainable cnn for joint detection and description of local features. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.03561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wu, X.; Chen, W.; Chen, P.C.Y.; Xu, Q.; Li, Z. ALIKED: A Lighter Keypoint and Descriptor Extraction Network via Deformable Transformation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revaud, J.; De Souza, C.; Humenberger, M.; Weinzaepfel, P. R2D2: Reliable and repeatable detector and descriptor. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.06195. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, Y.; Trulls, E.; Fua, P.; Yi, K.M. LF-Net: Learning local features from images. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.09662. [Google Scholar]

- Tyszkiewicz, M.; Fua, P.; Trulls, E. Disk: Learning local features with policy gradient. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.13566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Shen, T.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, J.; Yao, Y.; Li, S.; Fang, T.; Quan, L. Contextdesc: Local descriptor augmentation with cross-modality context. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.04084. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso-Laguna, A.; Riba, E.; Ponsa, D.; Mikolajczyk, K. Key. net: Keypoint detection by handcrafted and learned cnn filters. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.00889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenberger, P.; Sarlin, P.E.; Pollefeys, M. LightGlue: Local Feature Matching at Light Speed. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 17627–17638. [Google Scholar]

- Mishchuk, A.; Mishkin, D.; Radenovic, F.; Matas, J. Working hard to know your neighbor’s margins: Local descriptor learning loss. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Yu, X.; Fan, B.; Wu, F.; Heijnen, H.; Balntas, V. SOSNet: Second Order Similarity Regularization for local descriptor learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.05019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Urtasun, R. Are we ready for autonomous driving? KITTI Vision Benchmark Suite. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Providence, RI, USA, 16–21 June 2012; pp. 3354–3361. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Stiller, C.; Urtasun, R. Vision meets robotics: The KITTI Dataset. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2013, 32, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burri, M.; Nikolic, J.; Gohl, P.; Schneider, T.; Rehder, J.; Omari, S.; Achtelik, M.W.; Siegwart, R. The EuRoC micro aerial vehicle datasets. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2016, 35, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).