Abstract

This paper addresses the Sensor Deployment Optimization Problem (SDOP) by presenting a novel hybrid metaheuristic algorithm designed to create resilient and self-healing wireless sensor networks (WSNs). We introduce the Dynamic Multi-Pack Adaptive Grey Wolf Optimizer (DMPA–GWO++), which effectively balances network performance with durability against sensor failures. The core innovation is a hybrid structure that combines multi-pack GWO exploration with PSO-style local exploitation and memory, avoiding local optima while converging fast. This combination allows the algorithm to avoid local optima while rapidly converging on highly efficient solutions. A multi-objective fitness function explicitly accounts for network robustness by integrating a Monte Carlo simulation framework, pre-conditioning deployment layouts to withstand realistic sensor dropouts. Post-failure recovery is enhanced through an auto-suggest relay placement mechanism that strategically adds nodes to repair connectivity gaps. The approach is validated through the development of reliable sensor layouts that maintain high coverage and connectivity under diverse failure scenarios, demonstrating its utility for real-world WSN applications.

1. Introduction

Wireless sensor networks (WSNs) underpin disaster response, environmental monitoring, and precision agriculture by enabling continuous, reliable sensing [1,2]. Practical deployments face tight energy budgets, obstacles, and random node failures that can fragment connectivity, so fault tolerance must be optimized alongside coverage.

Metaheuristic algorithms such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [3], Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) [4], and Genetic Algorithm (GA) [1,5] work well on the Sensor Deployment Optimization Problem (SDOP) in wireless sensor networks (WSNs). Various extensions have improved their applicability in realistic environments—including relay-based recovery [6,7,8], obstacle-aware deployment [9], hybrid PSO–GWO models [10,11], adaptive or multi-strategy GWO variants [12,13,14], and domain-specific optimizers such as the Pelican Optimization Algorithm (POA) [2]. However, most existing studies assume static conditions and treat node recovery as a separate, post-deployment step. In practice, WSNs deployed in outdoor or agricultural environments experience stochastic failures, which are better modeled using in-loop Monte Carlo simulations [15] to capture real-world uncertainty.

Despite these advances, key gaps remain. Few methods jointly optimize coverage and connectivity while modeling post-failure recovery; adaptive mechanisms for maintaining population diversity are limited, and the coupling between sensor placement and relay-based repair remains weak—restricting true self-healing capability. To address these challenges, we propose DMPA–GWO++, a hybrid PSO–GWO framework enhanced with Monte Carlo-based robustness evaluation, a self-regulating multi-pack scheme (entropy-guided diversity and neuro-adaptive leadership), and an auto-suggest relay–repair module. The composite objective jointly optimizes deployment efficiency and post-failure resilience, producing fault-tolerant, self-healing WSN layouts. A comparative summary of related approaches and their limitations is presented in Table 1, highlighting how DMPA–GWO++ advances prior work.

Table 1.

Comparison of representative approaches in WSN deployment optimization.

2. Materials and Methods

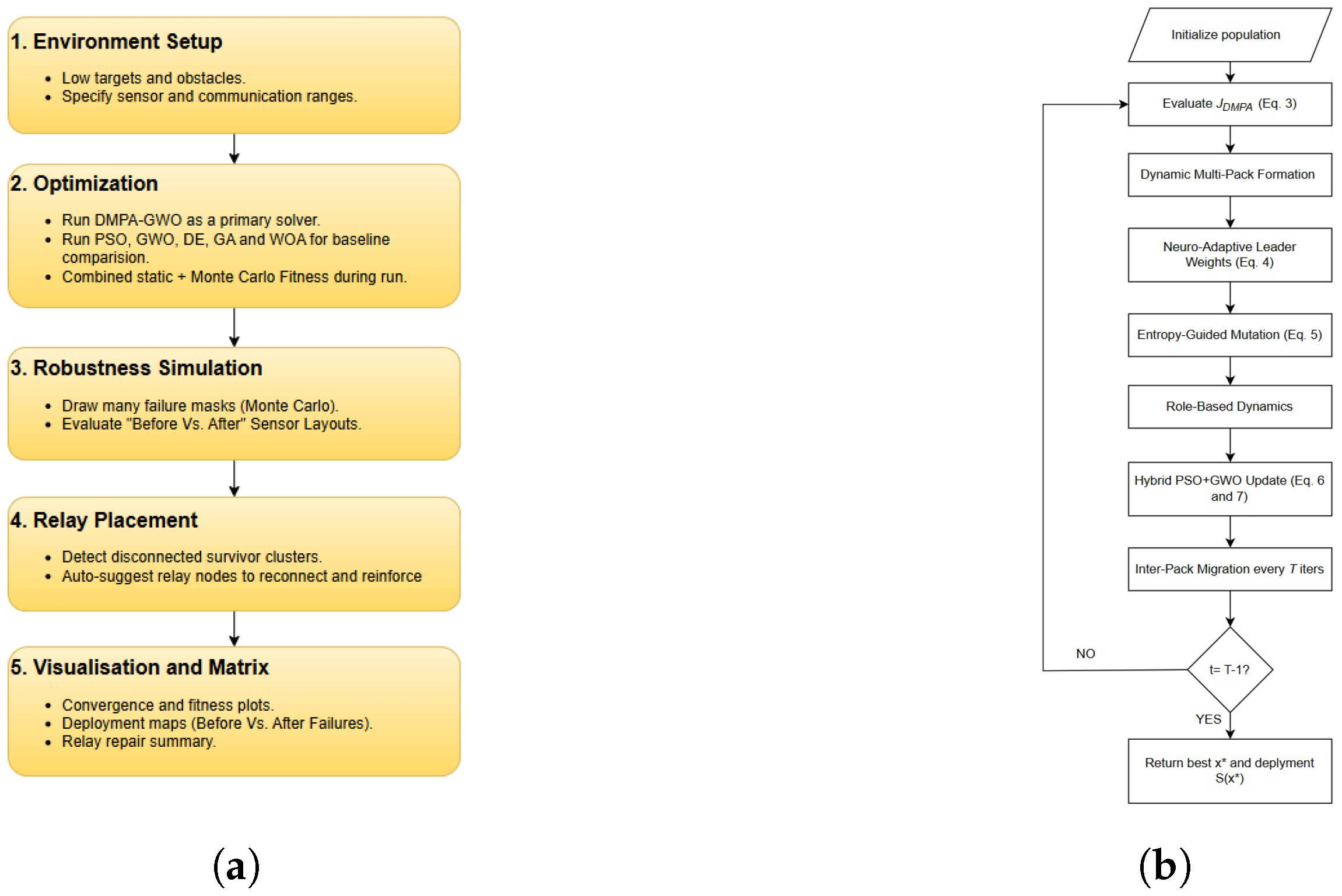

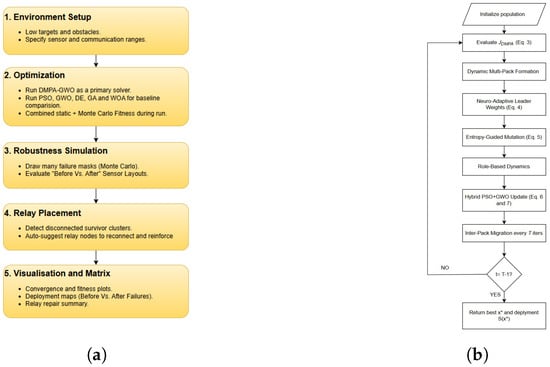

We follow the workflow in Figure 1a: initialize the environment (targets, obstacles, sensor parameters); run DMPA–GWO++ as the primary optimizer with PSO, GWO, DE, GA, and WOA as baselines under identical settings; score each candidate via the composite objective (Equation (3)) that blends static fitness (Equation (1)) and post-failure robustness (Equation (2)). Monte Carlo failures are embedded in-loop with = 20 samples per iteration to estimate expected performance; after convergence, robustness is re-evaluated over = 200 independent trials. If disconnections arise, an optional relay step (Equation (8)) computes the minimal relays to restore connectivity. We then visualize convergence, coverage, connectivity, and fitness before and after failures to assess overall resilience and recovery efficiency.

Figure 1.

DMPA–GWO++ workflow showing (a) the overall pipeline—environment setup, composite and Monte Carlo evaluation, failure simulation, relay placement, and final metric computation—and (b) the core algorithmic blocks, including adaptive multi-pack formation, neuro-adaptive leadership, entropy-guided mutation, role-based dynamics, and hybrid PSO–GWO updates that iteratively optimize candidate solutions and return the best solution x*, yielding the final sensor deployment S(x*).

2.1. Experimental Environment

Simulations were performed on a fixed field (). Default parameters were , , , , and independent per-sensor failure probability . In the absence of a real map, a seeded synthetic environment was used with 50 uniformly distributed targets and 8 circular obstacles (radius 8). All algorithms were tested under identical conditions for fair comparison. The base station (sink) was positioned at , interpreting as meters.

2.2. Problem Formulation

We address the robust two-dimensional deployment of n homogeneous sensors over a square agricultural field of side A. Each sensor has a sensing radius and communication radius . Let T denote target crop locations and O denote circular obstacles. A deployment is represented as . The objectives are to (i) maximize target coverage, (ii) maintain multi-hop connectivity under random node failures, and (iii) minimize redundant overlap and boundary violations.

2.3. Quality Metrics

For a deployment S, we compute the following: (i) Coverage—fraction of targets within of any sensor; (ii) Over-coverage—fraction covered by sensors; (iii) Pairwise overlap—number of pairs with ; (iv) Boundary violations—sensors outside ; (v) Static connectivity—fraction of sensors in the sink-anchored component via edges . These aggregate into the static loss (lower is better):

2.4. Robustness Under Random Failures

We model random failures by retaining each sensor independently with probability , yielding a surviving set . We recompute coverage (radius ) and connectivity (radius ), and define the single-trial penalty:

This penalty increases with loss of coverage and connectivity (lower is better). During optimization, the expected penalty is estimated via Monte Carlo with = 20 samples per call; for final reporting, we use = 200 independent trials and summarize results as mean ± SD, complementing the static loss in Equation (1).

2.5. Optimization Objectives

We optimize under two objectives.

Composite (proposed).

which jointly trades off static layout quality (Equation (1)) and expected post-failure penalty (Equation (2)).

Robust-only (baselines). Minimize under the same budget.

- Here, reshapes to .

2.6. Proposed Algorithm: Dynamic Multi-Pack Adaptive Grey Wolf Optimizer (DMPA–GWO++)

Overview. GWO [4] explores well but can stagnate; PSO [3] converges fast but may over-exploit. DMPA–GWO++ fuses both via (i) dynamic multi-pack exploration, (ii) neuro-adaptive leader weights, (iii) entropy-guided mutation, (iv) role-based moves (exploit/explore/repair), (v) periodic inter-pack migration, and (vi) a hybrid PSO + GWO update. Candidates are scored by the composite objective (Equation (3)) with in-loop Monte Carlo robustness.

Notation. Population , ; personal best , velocity ; pack leaders .

(a) Dynamic Packs. Split into packs using k-means over ; adapt by dispersion (more packs when diverse). This adaptive partitioning maintains diversity by forming more sub-packs when agents are spatially scattered, enhancing global exploration.

(b) Neuro-Adaptive Leaders. With leader improvement and ,

These adaptive weights adjust each leader’s influence according to its improvement rate, assigning stronger impact to faster-converging leaders.

(c) Entropy-Guided Mutation. Let be diversity (fitness entropy):

Here, controls mutation strength based on population entropy, introducing higher stochasticity when diversity decreases to prevent stagnation.

(d) Role-Based Dynamics. Top 30% exploit (low noise), mid 50% explore (higher noise), bottom 20% repair (reconnect bias); mask sets intensity. This structured role division balances exploitation, exploration, and repair behavior, ensuring stable and resilient convergence.

(e) Inter-Pack Migration. Every iterations, exchange a few elites/weak agents across packs. The migration mechanism promotes information sharing between packs, avoiding premature convergence and improving diversity.

(f) Hybrid Update.

The velocity equation combines PSO’s cognitive–social learning with GWO’s leadership guidance, while the position update adds Gaussian noise for controlled diversity, enhancing both exploration and convergence stability.

2.7. Baselines and Convergence Evaluation

Robust variants of PSO, GWO, DE, GA, and WOA were implemented as baselines. Each used the robust-only objective under the same computational budget, with population size 30, 50 iterations, and identical box constraints.

2.8. Post-Failure Relay Redeployment

An optional repair analysis introduced a greedy relay strategy with budget . On the post-failure communication graph, disconnected components were iteratively bridged with relays along the shortest inter-component segment. The number of required relays was

where d is the nearest cross-component distance. Bridging continued until either full connectivity or exhaustion of the relay budget.

2.9. Statistical Reporting and Reproducibility

The full iterative workflow of the proposed DMPA–GWO++ method, including multi-pack adaptation, leader weighting, entropy control, and hybrid PSO–GWO updates, is detailed in Algorithm 1. Each algorithm was tested under random-failure masks. Robustness was reported as mean ± SD for fitness (↓), coverage (↑), and connectivity (↑). Convergence was summarized using the final best-so-far at iteration 50. All experiments used fixed seeds (e.g., numpy.random.seed(42)) to ensure reproducibility.

| Algorithm 1 DMPA–GWO++ |

|

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the findings from our study on robust sensor deployment using DMPA–GWO++, with comparisons against baseline optimizers and an analysis of convergence, robustness, and practical implications.

3.1. Overall Performance

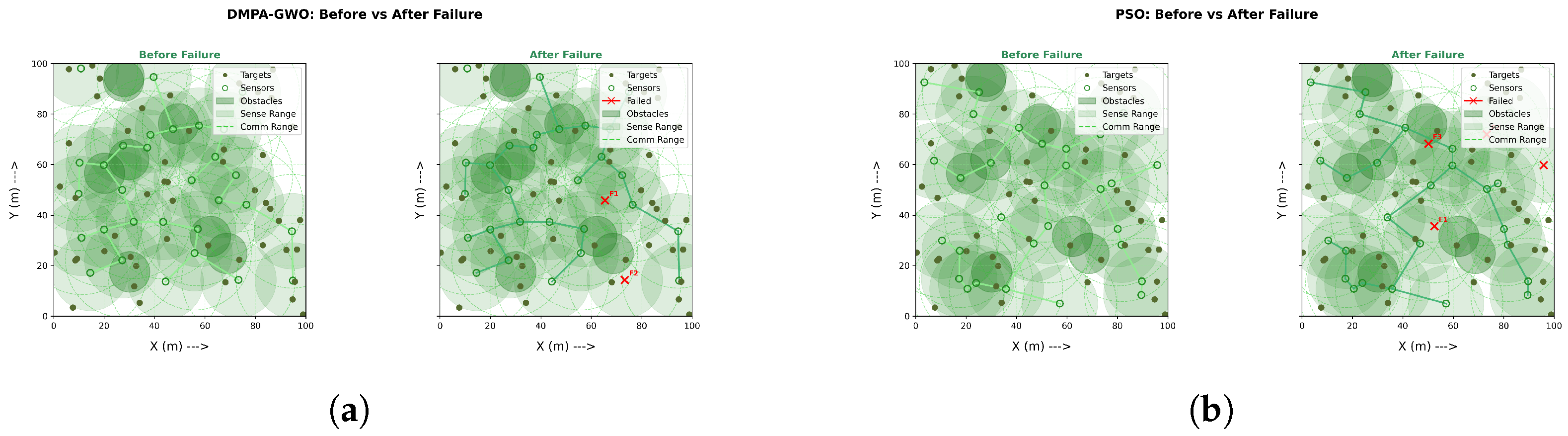

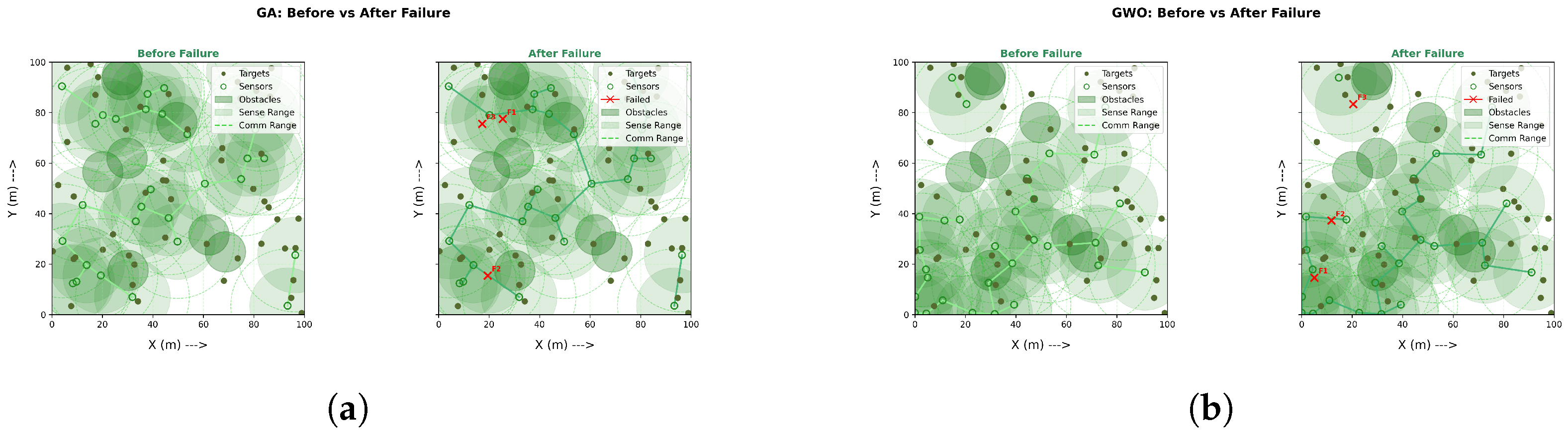

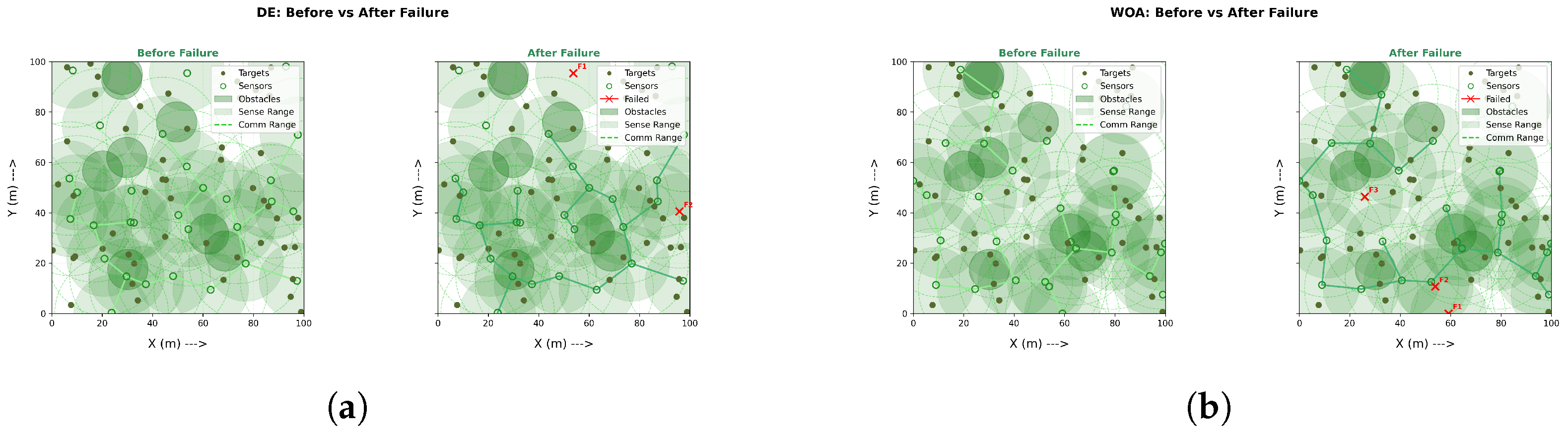

Under identical budgets, DMPA–GWO++ yields the most robust deployments (Figure 2a), sustaining higher coverage and stronger sink-anchored connectivity after failures. By comparison, PSO and GA (Figure 2b and Figure 3a) reach moderate coverage but leave isolated survivors; GWO and DE (Figure 3b and Figure 4a) degrade in both coverage and connectivity; and WOA (Figure 4b) attains high coverage yet poor connectivity, causing post-failure fragmentation. Conclusion: optimizing coverage alone is insufficient—maintaining a connected backbone is crucial for fault-tolerant WSNs.

Figure 2.

Overall performance (1/3): DMPA–GWO++ vs. PSO. (a) High coverage; survivor graph largely stays connected after failures. (b) Good coverage; survivor graph fragments in multiple regions.

Figure 3.

Overall performance (2/3): GA vs. GWO. (a) Coverage comparable to PSO but weaker backbone after failure. (b) GWO shows disconnected survivor components after failure.

Figure 4.

Overall performance (3/3): DE vs. WOA. (a) Moderate coverage; fragmentation persists after failure. (b) Highest raw coverage; backbone breaks after failure.

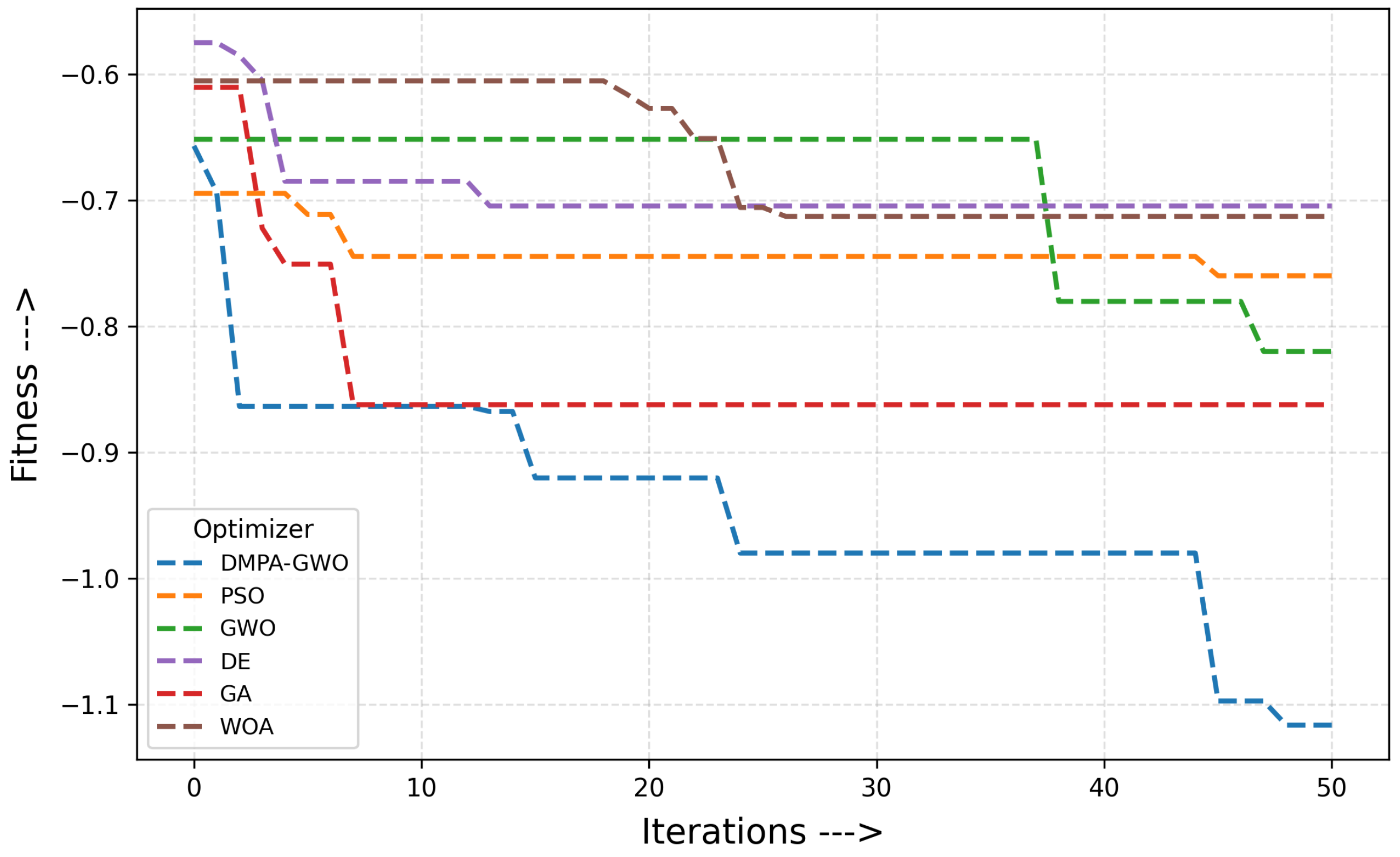

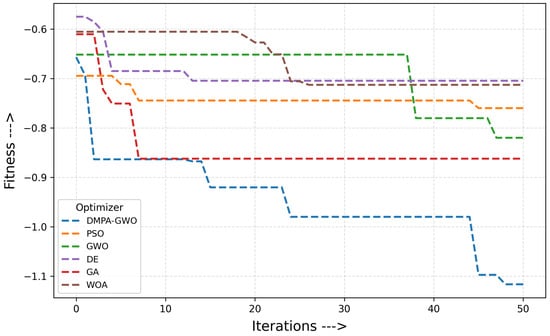

3.2. Convergence Dynamics

Measured by best-so-far post-failure static fitness per iteration (Figure 5), DMPA–GWO++ descends rapidly and stabilizes at a lower loss than all baselines. PSO and GA converge more slowly; GWO and DE plateau earlier at higher losses; WOA mainly lowers loss via coverage gains but fails to secure resilient connectivity. The steady progress of DMPA–GWO++ stems from its multi-pack diversity, neuro-adaptive leadership, and role specialization.

Figure 5.

Convergence dynamics: best-so-far post-failure static fitness per iteration.

3.3. Monte Carlo Robustness

Over = 200 random-failure trials, DMPA–GWO++ achieved the lowest (best) mean fitness with lower variance than all baselines (Table 2), reflecting consistently higher resilience. WOA had the highest coverage but poor post-failure connectivity; PSO/GA offered moderate balance; GWO/DE plateaued at higher loss.

Table 2.

Monte Carlo robustness (mean ± SD over 200 trials).

Significance. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (two-tailed, = 0.05, paired n = 200) against each baseline yielded p < 0.01, confirming that DMPA–GWO++ improvements are statistically significant.

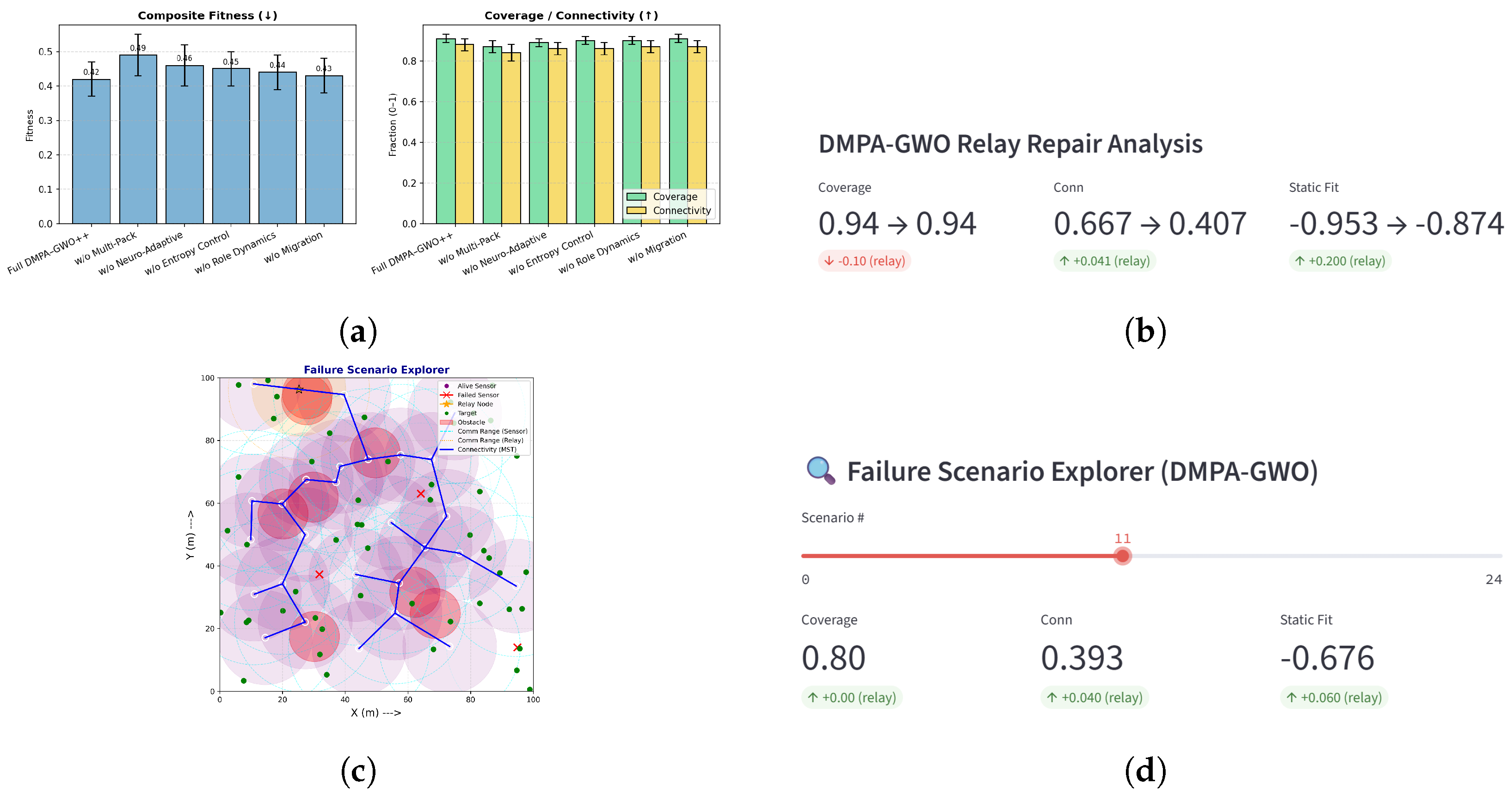

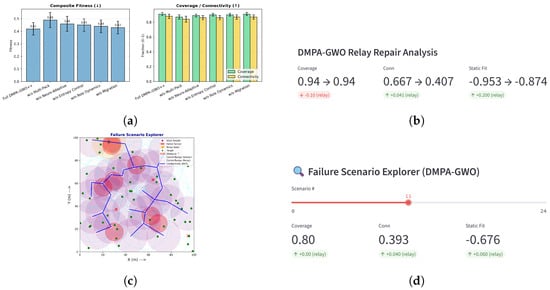

3.4. Relay Redeployment After Failures

With , connectivity was typically restored with 2–3 relays (median = 2, IQR = 2–3), while coverage remained largely unaffected. Figure 6b. reports the ablation results: the multi-pack mechanism produces the largest benefit (≈25% loss reduction), with neuro-adaptive and entropy modules improving stability and diversity; role-based dynamics aid reconnection and migration reduces variance, together yielding balanced coverage–connectivity. Greedy bridging required only a few relays, as optimized layouts already aligned sensors along resilient corridors. Minor static penalties from relay overlap were offset by connectivity gains (Figure 6c), with overall coverage and fitness improving after relay insertion (Figure 6d).

Figure 6.

Relays bridge nearest inter-component gaps; few relays suffice. Purple shaded disks represent the communication ranges of alive sensors (conceptually shown as white hollow circles in the system model). insertion and ablation results: (a) ablation impact; (b–d) relay effects on topology and metrics. (a) Ablation: composite fitness (left) and coverage/connectivity (right). (b) Connectivity rises with minimal coverage change; fitness improves. (c) Relays bridge nearest inter-component gaps; few relays suffice. Purple shaded disks represent the communication ranges of alive sensors (conceptually shown as white hollow circles in the system model). (d) Scenario-level coverage, connectivity, and fitness (pre/post relays).

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Conclusions. Connectivity drives robustness. DMPA–GWO++ achieves the best mean fitness (0.42 ± 0.05; 200 trials) and strong coverage/connectivity (0.91 ± 0.02, 0.88 ± 0.03), converging in <50 iterations. With K = 5, typically 2–3 relays restore links. Guideline: build connectivity-aware backbones and retain spares for targeted repair.

Future work. (i) Couple robustness with energy/traffic (lifetime, QoS); (ii) model path-loss/terrain and correlated/targeted failures; (iii) multi-objective Pareto (coverage, connectivity, energy, relay cost); (iv) co-design sensors+relays and use variance-reduction for faster estimates; (v) scale (n = 50–100), enable online/decentralized reconfiguration, and validate on-farm.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.; methodology, A.K.; investigation and results, A.K. and K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K. and L.V.; writing—review and editing, A.K. and L.V.; supervision and guidance, K.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge that this research was carried out at the International Institute of Information Technology (IIIT), Naya Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India. The authors are grateful to the institute for providing the necessary infrastructure and supportive environment for this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gouda, O.; Nassif, A.; Abutalib, M.; Nasir, Q. A Systematic Literature Review on Metaheuristic Optimization Techniques in WSNs. Int. J. Math. Comput. Simul. 2020, 14, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Cao, Q.; Cao, B.; Jin, B. An Innovative Coverage Optimization Method for Smart Information Monitoring in Agricultural IoT Using the Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the ICNN’95-International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey Wolf Optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Das, S.K. Coverage and Connectivity Issues in Wireless Sensor Networks: A Survey. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2008, 4, 303–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xue, G.; Misra, S. Fault-Tolerant Relay Node Placement in Wireless Sensor Networks: Problems and Algorithms. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2007-26th IEEE International Conference on Computer Communications, Anchorage, AK, USA, 6–12 May 2007; pp. 1649–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Hao, B.; Sen, A. Relay Node Placement in Large Scale Wireless Sensor Networks. Comput. Commun. 2006, 29, 2700–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, S.; Parvathy, P. Optimal Relay Node Placement with Game Theory in Wireless Sensor Networks. J. High Speed Netw. 2024, 30, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza-Gutiérrez, J.M.; Caballé, N.; Gómez-Pulido, J.A.; Crawford, B.; Soto, R. Toward a Robust Multi-Objective Metaheuristic for Solving the Relay Node Placement Problem in Wireless Sensor Networks. Sensors 2019, 19, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, G.; Wei, G. Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization-Based Modeling of Wireless Sensor Network Coverage Optimization. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 982–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siamantas, G.; Kandris, D. Particle Swarm Optimization for k-Coverage and 1-Connectivity in Wireless Sensor Networks. Electronics 2024, 13, 4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Qin, F.; Zhou, K.-Q.; Yin, P.-F.; Mo, L.-P.; Mohd Zain, A. An Improved Grey Wolf Optimizer with Multi-Strategies Coverage in Wireless Sensor Networks. Symmetry 2024, 16, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Yuan, X.; Yan, B.; Song, Y.; Xu, Q.; Yang, X. An Improved Grey Wolf Optimization with Multi-Strategy. Sensors 2022, 22, 6843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; He, W. Review of the Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 2713–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Das, S.K. Modeling and Analysis of Cascading Node-Link Failures in Multi-Sink Wireless Sensor Networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 197, 106813. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).