Abstract

Diabetes mellitus represents a global health concern, which is expected to worsen over the years. The prevalence is estimated to increase up to 642 million people by 2040. Almost half of diabetic patients are at a high risk of developing kidney involvement up to dialysis; moreover, macrovascular complication could be an obstacle to kidney transplant. Besides the classic albuminuric phenotype, non-albuminuric diabetic kidney disease was also discovered recently. Fortunately, compared with classic therapy with diet, oral hypoglycemic drugs, and insulin, current clinicians can rely on several new drugs that act with different pathways characterized by kidney and heart protection, as shown by several clinical trials and confirmed in clinical practice. Herein, we will review the therapies that nephrologist and diabetologist have available today and the future perspective.

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus represents a global health concern, which is expected to worsen over the years. The prevalence is estimated to increase up to 642 million people by 2040 [1]. There is an increase in global deaths and years of life lost in the 2040 forecast, showing both better and worse health scenarios for diabetes [2].

Despite the fact that it took over three millennia from the first description of diabetes to the association between diabetes and kidney disease [3], only several decades were needed for diabetic kidney disease to become the leading cause of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) worldwide, involving, nowadays, 40% of new patients requiring dialysis [4]. It can develop in the course of type 1 or type 2 diabetes, despite the different pathogenesis. Type 1 is an autoimmune disease due to the presence of the antibody working directly against pancreatic islet cells, while type 2 is a result of insulin resistance and insulin deficiency.

Until now, chronic kidney disease (CKD), defined by international guidelines as abnormalities of kidney structure or function present for ≥3 months and with implications for health [5], caused by diabetes mellitus is identified as diabetic nephropathy (DN), which begins with microalbuminuria, followed by macroalbuminuria and a progressive decline in kidney function, characterized by defined histopathological findings, such as increased mesangial substrate, nodular lesions, and tubulointerstitial fibrosis [6].

Recently, the finding of cases of impaired renal function without albuminuria in diabetic patients have led to epidemiological surveys that have underlined the heterogeneity of the natural history of kidney involvement, using “diabetic kidney disease” as the definition to include all types of renal injury occurring in diabetic patients [7]: classical diabetic nephropathy (DN), vascular and ischemic glomerular changes, and other glomerulonephritis in the presence or absence of DN [8]. The prevalence of these entities is influenced by ethnicity, geography, and selection criteria for renal biopsy in the presence of diabetes [9]. The risk for DKD is the same for type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

The pathogenesis of DKD includes glomerular hypertension with the upregulation of the renin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and consequently, a change in kidney hemodynamics, ischemia and hypoxia, and oxidative stress. Overall, the full pathogenesis remains not completely understood [10].

Several experimental models have shown the persistence of the aberrant expression of fibrotic, antioxidant, and inflammatory genes in vascular cells and endothelial cells despite glucose normalization. Recently, this phenomenon, known as “metabolic memory”, has shown that patients with past exposure to high levels of glycemia will more frequently develop complications, including DKD, even after the normalization of blood glucose levels, due to the accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and epigenetic changes, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, which could contribute to the progression of DKD as a cellular memory [11]. Several complications of diabetes appear to have a genetic predisposition: genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have uncovered only limited possible loci, while the evaluation of epigenotypes by epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) could provide new information about the pathogenesis of diabetic complications and metabolic memory, with the possibility of developing new therapeutic strategies and new biomarkers. Moreover, the most polymorphism seems to be in non-coding or other regulatory regions of the genome which can alter gene expression [11]. Molecular and cell-based therapies, such as miRNA modulators, stem cell therapy, and gene therapy, are in preclinical or early clinical phases, with the goal of promoting kidney repair [12]. This will result in precision medicine that, together with artificial intelligence, could help to stratify the risk of the progression of the disease and individualize therapy [13].

Moreover, the recently defined Cardio–Kidney–Metabolic (CKM) syndrome emphasizes the interconnectedness of cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic pathways. The American Heart Association (AHA) has formally described CKM syndrome as a systemic disorder characterized by pathophysiological interactions among metabolic risk factors (such as obesity and diabetes), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and cardiovascular disease (CVD), which collectively drive multiorgan dysfunction and substantially increase the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes [14,15].

The interconnectedness is rooted in shared mechanisms including chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, the activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, and neurohormonal dysregulation. For example, dysfunctional adipose tissue—especially visceral fat—releases pro-inflammatory and prooxidative mediators that contribute to vascular, cardiac, and renal injury, and further impair insulin sensitivity, amplifying metabolic dysfunction and systemic inflammation [14,16]. These processes create a vicious cycle in which the impairment of one organ system accelerates deterioration in the others.

The AHA emphasizes that CKM syndrome should be approached holistically, with integrated prevention, screening, and management strategies that address all three domains rather than treating them as isolated conditions because the presence of multiple CKM components confers additive risk for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, as well as progression to end-stage kidney disease [17].

Herein, we will review the therapies in greater number that nephrologists and diabetologists have available today, with a focus on the results of the latest clinical trials, and the use of these new drugs in kidney transplant recipients and in subjects with an oncological pathology.

2. Role and Importance of Kidney Biopsy for the Diagnosis of DKD

The true incidence of CKD and ESKD from diabetes is difficult to estimate because kidney biopsies have not always been performed due to the prevailing notion among nephrologists that CKD in the context of diabetes is attributed to DN [18]. Most nephrologists would agree that a kidney biopsy is needed when its result may change treatment [19].

Therefore, biopsy has been performed in defined clinical conditions such as the absence of diabetic retinopathy, an expected decrease in kidney function, the sudden onset of proteinuria, an unexpected increase in albuminuria, and the new onset of other signs of systemic disease.

The new clinical phenotype of DKD highlights the importance of performing kidney biopsy: patients with normo-albuminuric kidney disease show a predominance of macrovascular and tubule interstitial changes compared with classical DN [20].

The treatment strategy of DKD is still represented by a multidisciplinary approach starting with lifestyle modifications treating overweight, when present, smoke cessation, the improvement of blood glucose levels, and dyslipidemia and blood pressure control. To the pillar of therapy represented by RAAS inhibitors, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2is) have also been added as the new drug of choice for the treatment of DKD since 2019. In addition to these drugs, there are other emerging therapies aimed at slowing the progression of kidney disease towards ESKD.

In this new “pharmacological era”, histopathology provides the roadmap for tailoring treatment and reducing the progression of the disease [9]. The transition from a one-size-fits-all medical approach to personalized medicine is supported by the information unlocked through kidney biopsies [9].

In our experience, of sixty diabetic patients biopsied in fifteen years in our Kidney Unit, 63% showed histological lesions in line with diabetic kidney disease, 11% had other glomerulonephritis, while 26% exhibited lesions due to diabetes and associated glomerulonephritis. The therapeutic management of this last group of patients represents a challenge for clinicians, showing the importance of kidney biopsy for identifying the prevalent lesions and personalizing the therapy by weighing up the risks and benefits (for example the risk of worsening diabetes if steroid therapy is needed).

3. Metformin-Associated Lactic Acidosis (MALA)

Metformin is a biguanide drug commonly used for the initial treatment of type 2 diabetes. It works on gluconeogenesis, decreasing hepatic glucose production and increasing the glucose uptake in peripheral tissue.

Due to its pharmacokinetic features (high volume distribution, negligible plasma protein binding, primarily renal excretion), the risk of accumulation and toxicity is higher in acute or chronic renal failure and caution must be used in patients with CKD. In fact, for eGFR > 45 and <60 mL/min, no dosage adjustment is necessary (but the frequent monitoring of renal function is recommended), while eGFR lower than 30 mL/min represents one of the major contraindications to the use of metformin by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indications, which recommend avoiding starting use with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) between 30 and 45 mL/min [20,21].

The most feared complication related to drug intoxication is metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA), defined as pH < 7.3 and lactate > 5 mmol/L when drug plasmatic concentrations are >5 mg/L. Some medical conditions (like dehydratation due to gastroenteritis or fever and infections) are known as precipitating causes of MALA, predisposing to the development of acute kidney injury (AKI). The co-therapy with drugs acting on RAAS can often also contribute to decreased renal function.

MALA is a potentially life-threatening disease, characterized by a high mortality rate (reported to be between 30 and 50% [22,23]), for which no antidote is available. For this reason, in cases of oligoanuric AKI, severe lactic acidosis, or hyperkalaemia, when medical therapy is ineffective, kidney replacement therapy as emergency treatment could be necessary.

As regards the best treatment, no conclusive data are available to guide specialists in the choice of kidney replacement therapy (KRT) modality. Between 1 January 2022 and 30 September 2024, we treated 20 patients admitted at Piacenza “Guglielmo da Saliceto” Hospital with a diagnosis of MALA (Table 1, based on personal unpublished data.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory data and the start and end of dialysis session (mean and standard deviation values of 20 patients).

At dialysis start, metformin levels were toxic for all patients (mean range 7–61.01 mg/L, normal value 0–1.99 mg/L). After the first dialysis session, a drug reduction rate occurred in about 50% (44.8% for intermittent hemodialysis (IHD)) and 55.2% for sustained low-efficiency daily diafiltration (SLEDD-f) with a slight rebound in eleven patients. Two patients died after the first treatment (one received a SLEDD-f session and one IHD); all other patients received two or more dialysis sessions to avoid potential drug rebound. The other two patients died during hospitalization due to infectious complications several days after dialysis interruption (which occurred due to the normalization of electrolytes, acid–base disorders, and restored kidney function). After discharge, one patient continued ambulatory hemodialysis three times/week, with treatment interruption after 30 days for partial renal recovery function (residual stage 3b CKD).

Some authors have suggested sustained low-efficiency dialysis (SLED) as the best type of treatment in patients with MALA and AKI [24] but in our experience, both IHD and SLEDD-f were effective in patients with acute kidney injury and lactic acidosis caused by metformin intoxication.

The choice of treatment type was guided by patients’ hemodynamic status, hospitalization setting, and the availability of different dialysis machine types. Our 10% mortality rate for MALA treated with dialysis is lower than the mortality rates commonly reported in the medical literature [25,26], but still, it remains clinically significant. The mortality rate was low for both treatment types and renal recovery was not related to the initial choice of renal replacement therapy.

4. Contemporary Therapies

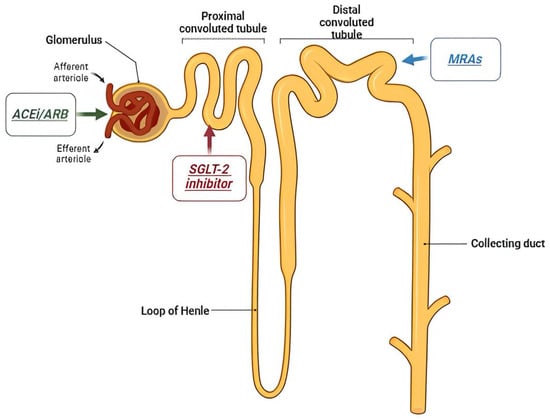

The role of kidney in the management of diabetic kidney disease is underlying by the mechanism of action of several drugs applied in this disease, that acting in several part of the nephron. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Antidiabetic drugs’ target within the nephron.

4.1. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor and Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker

The oldest and most pre-eminent drug for DKD treatment is RAS inhibition. RAS inhibitors have been shown to be effective in treating DKD in many clinical trials. In 1993, the Captopril Collaborative Study published by Lewis et al. showed that captopril, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I), inhibited the progression of nephropathy inpatients with type 1 diabetes mellitus [27]. Thereafter, large randomized controlled trials showed a reduction in the progression from microalbuminuria to proteinuria [10], as reported in Table 2.

RAASi are also able to prevent the development of microalbuminuria in normotensive patients; for this reason they should be used either in patients with hypertension or nephropathy [28].

Despite some studies reporting clinical benefits [29], such as the better control of albuminuria, better cellular sensitivity to insulin, and also reducing the risk of developing de novo diabetes [30] and improving diabetic nephropathy and heart failure, the combination therapy of ACE-I and angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) is not recommended based on ONTARGET and VA Nephron D trials [20,21]. These studies did not show significant differences in the efficacy for DKD, reporting on the other side, a higher number of adverse events, such as hyperkalemia and acute kidney injury (AKI), despite a substantial reduction in albuminuria. Moreover, in the ONTARGET patients a low risk of progression to ESKD was shown with a low urine albumin–creatinine ratio (7.2 mg/g) and an average eGFR of 73.6 mL/min/1.73 mq. Only 263 patients out of 25,620 were affected by CKD and stages 4 and 5 (eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 mq) and only 0.4% of the patients developed ESKD during the study [31,32]. The incidence of ESKD in the group of patients treated with ACEi or ARB overlapped with the group treated with both drugs [27]. Nevertheless, in selected patients, the risk of hyperkaliemia could be often better managed with diet with a low amount of potassium and with the use of new oral K+-binding agents.

Table 2.

Clinical trials with the use of ACEi and ARBs in diabetic patients with kidney disease. UACR: urine albumin–creatinine ratio; ESKD: end-stage kidney disease.

Table 2.

Clinical trials with the use of ACEi and ARBs in diabetic patients with kidney disease. UACR: urine albumin–creatinine ratio; ESKD: end-stage kidney disease.

| Trial | Treatment | Population | Follow Up | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RENAAL (2001) [33] | Losartan |

| 3.4 years | Significant reduction in the progression of diabetic nephropathy, slowing the onset of ESKD and doubling serum creatinine. It did not have a significant impact on overall mortality or cardiovascular events, however. |

| INDT (2005) [33] | Irbestartan |

| 2.6 years | Effectiveness in slowing the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension, independent of the effect on blood pressure. |

| INNOVATION (2007) [34] | Telmisartan |

| 2 years | Efficacy in delaying the worsening of diabetic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes who had microalbuminuria; inhibition of the progression from microalbuminuria to overt proteinuria by approximately 60% compared with placebo. |

| IRMA-2 (2001) [35] | Irbesartan |

| 2 years | Inhibition of the progression from microalbuminuria to overt proteinuria by approximately 70%. |

| MARVAL (2002) [36] | Valsartan |

| 6 months | The comparison between an ARB with a calcium channel blocker showed that only ARB was effective in lowering microalbuminuria, indicating that RAS inhibitors have an inhibitory effect on nephropathy and a blood pressure-lowering ability. |

| BENEDICT (2004) [37] | Tradolapril |

| 3.6 years | ARBs reduced the incidence of microalbuminuria among patients who did not present with microalbuminuria. |

| ROADMAP (2011) [38] | Olmesartan |

| 5 years | ARBs reduced the incidence of microalbuminuria among patients who did not present with microalbuminuria. |

4.2. SGLT2 Inhibitors

SGLT2 inhibitors (SGLT2is) were originally developed to treat type 2 diabetes and have demonstrated protective cardiorenal benefits in people with diabetes and in patients with known kidney disease [39,40], emerging as a pivotal class of medications in the management of CKD, especially for patients with DKD [39,40]. These drugs have been shown to significantly slow down the progression of kidney disease, reduce proteinuria, decrease the risk of end-stage kidney failure, and improve overall kidney function in patients with type 2 diabetes, as well as those with non-diabetic CKD [39,40,41].

The main mechanism whereby SGLT2is provide their nephroprotective effects is reducing the workload on the kidneys [41]. In CKD, the kidneys undergo hyperfiltration to compensate for the loss of functioning nephrons. This increased filtration can worsen kidney damage, according to Brenner’s hyperfiltration hypothesis. SGLT2is counteract this mechanism by promoting the excretion of glucose, sodium, and water, leading to a reduction in intraglomerular pressure, which improves kidney hemodynamics and consequently protects the kidneys from further damage and slows the progression of kidney disease. [40,41].

In in vitro and in vivo models, SGLT2is have been shown to improve pathological processes involved in the development and progression of kidney aging, including inflammation, fibrosis, cellular senescence, endothelial disfunction, and mitochondrial injury, through both blood glucose-dependent and independent mechanisms [42,43].

Clinical studies (see Table 3) have shown that SGLT2is, such as empagliflozin, canagliflozin, and dapagliflozin, reduce albuminuria (a marker of kidney damage) and improve the eGFR, a key indicator of kidney function (the reversible decrease in eGFR on initiation is generally not an indication to discontinue therapy) [44,45]. Furthermore, they reduce the risk of major adverse kidney events, including the need for dialysis or kidney transplant [40,46,47,48]. The CREDENCE trial, the DAPA-CKD trial, and the EMPA-KIDNEY trial have been instrumental in demonstrating the efficacy of these drugs in non-diabetic CKD as well, proving that their benefits extend beyond diabetes-related kidney disease to other forms of chronic kidney impairment [45].

SGLT2 inhibitors have revolutionized the treatment of CKD, offering significant nephroprotective effects and reducing the progression of kidney disease in both diabetic and non-diabetic subjects [5]. By improving kidney hemodynamics, reducing albuminuria, and providing cardiovascular benefits, these medications are now considered a first-line option in managing CKD, particularly in patients at a high risk of progression [5].

Moreover, SGLT2 inhibitors have shown significant cardioprotective effects [47]. Large clinical studies such as EMPA-REG OUTCOME, CANVAS, and DAPA-HF have shown that these agents reduce the risk of hospitalization for heart failure and cardiovascular death, while improving outcomes in heart failure, regardless of their glucose-lowering effects [48,49,50]. Their benefits are attributed to many mechanisms including osmotic diuresis, a reduction in blood pressure, an improvement of myocardial energy efficiency, and a reduction in inflammation [51,52]. Consequently, SGLT2 inhibitors are now recommended for diabetic patients with cardiovascular disease or at high cardiovascular risk [47].

Regarding adverse effects, SGLT2 inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of genital infections due to the loss of glucose in urine, acute kidney injury, and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), which is a potentially life-threatening complication; indeed SLGT2is are contraindicated in patients with type 1 diabetes [53].

SGLT2is should not be started in patients with a history of urinary infection, while DKA is more common in the presence of precipitating factors, such as starvation, acute illness, and surgical procedure, so it is mandatory to hold the drug during this time, particularly in elderly and oncology patients [54].

Table 3.

Clinical trials about the use of SGLT2is in diabetic patients with kidney disease.

Table 3.

Clinical trials about the use of SGLT2is in diabetic patients with kidney disease.

| Trial | Treatment | Population | Follow Up | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMPA-REG OUTCOME (2015) [50] | Empaglifozin |

| 3.1 years | Significant reduction in cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease and in progression of nephropathy |

| CANVAS (2017) [48] | Canaglifozin |

| 4.3 years | Reduction in cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), or nonfatal stroke by 14% compared with placebo 33% reduction in hospitalization for heart failure 40% reduction in the risk of a composite renal outcome |

| CREDENCE (2019) [55] | Canaglifozin |

| 2.6 years | Significant reduction in the risk of ESKD or cardiovascular death (30%) compared with placebo |

| DAPA-CKD (2020) [56] | Dapaglifozin |

| 2.4 years | Significant reduction in the risk of ESKD, ≥50% sustained decline in eGFR or cardiovascular death |

| EMPA-KIDNEY (2023) [45] | Empaglifozin |

| 2 years | Reduction in risk of CKD progression or cardiovascular death by 28% with empagliflozin compared with placebo Reduction in the risk of all-cause hospitalization by 14% |

4.3. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

Glucagon-like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), or incretin mimetics, bind to GLP-1 receptors, which are expressed in different tissues, including pancreatic β-cells, the brain, and kidneys [57,58]. They are effective in glucose control, weight loss, and CV risk reduction in subjects with diabetes [59,60,61,62]. Since obesity and T2DM present major global health challenges with an increasing prevalence worldwide, GLP-1RAs have emerged as a pivotal treatment option for both conditions [63].

With regard to renal function, firstly, they are safe and maintain their efficacy also in subjects with low eGFR. Moreover, recent studies suggest that GLP-1 RAs also provide renal protective effects in subjects with diabetes, namely reducing albuminuria, improving GFR, and potentially slowing the progression of CKD [64,65]. Dulaglutide provided adequate glycemic control irrespective of CKD stage and was associated with a reduced decline in eGFR in a CKD population [66,67]; semaglutide reduced the risk of clinically important kidney outcomes and death from cardiovascular causes in patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD [64,68]

Retatrutide (LY3437943), a dual (GLP1-GIP) receptor agonist, showed substantial body weight reduction in adults with obesity [69]; a post hoc analysis of phase 2 trials suggested possible benefits for kidney function [70] and another specifically designed trial is currently ongoing (NCT05936151). In a post hoc analysis of the SURPASS-4 trial [71], tirzepatide, a dual (GLP1-GIP) receptor agonist, reduced a composite kidney endpoint by 42%, compared with insulin glargine.

A recent retrospective study showed the real-world effectiveness of GLP-1 RAs for T2D and CKD [72]: GLP-1 RAs provided a higher reduction both in HbA1c and weight and greater kidney protection, compared with basal insulin, among adults with T2DM and CKD already treated with an SGLT2i. Interestingly, semaglutide improved kidney outcomes also in people without diabetes [73]. Clinical studies have shown the effects of weight loss on kidney function: caloric restriction can reduce proteinuria, even by more than 80% of the baseline values [74]. Moreover, evidence suggests that the antiproteinuric effect could be directly induced by caloric restriction by itself, even with the achievement of a significant weight loss [75]. The use of GLP-1 could be used therefore also in patients without diabetes but with obesity, which represents itself a risk condition to develop diabetes.

GLP-1 RAs improve endothelial function and vasodilation in the glomerulus, potentially reducing glomerular hyperfiltration; furthermore, they may reduce inflammation and oxidative stress in the kidney, both of which contribute to the pathogenesis of albuminuria and renal fibrosis [57,76]. GLP-1 RAs have also been shown to reduce intraglomerular pressure and influence renal hemodynamics by improving renal blood flow, which may help preserve GFR [57,58,76]. Their nephroprotective properties may therefore be related to both metabolic and non-metabolic mechanisms.

KDIGO Guidelines [77] strongly recommends long-acting GLP-1 Ras, with documented cardiovascular benefits for people with T2D and CKD who have not achieved individualized glycemic targets despite the use of SGLT2is, with or without metformin, or who are unable to use those medications. Incretin mimetics may also have a role in the treatment of people with CKD who do not have T2D. As for SGLT2is, initial studies of incretin mimetics focused on people with T2D, but as benefits were observed and suggested to be independent of glycemia control, inclusion criteria should be broadened to other CKD groups.

Therefore, these drugs are increasingly being considered in the management of CKD, particularly in patients with concomitant diabetes and other risk factors for CKD progression [5,77,78].

It is recognized that dialysis patients with a higher BMI show better survival, probably because it helps against protein–energy wasting and inflammation. This phenomenon is called the “obesity paradox”, which appears in conflict with the use of GLP-1 in this population. On the other hand, weight loss in these patients could represent the possibility of kidney transplant eligibility. The weight loss and sarcopenia must be associated with the preservation of muscle mass with a specific diet and physical exercise. However, long-term clinical data are still needed to fully understand their role in the management of CKD. Meta-analysis did not show serious adverse events, but in clinical practice there are some side effects, in particular, gastrointestinal (nausea, reduction in appetite, vomiting, and diarrhea). GLP1-RA may cause injection site reactions and an increase in heart rate, which is usually transient [79].

4.4. Mineralocorticoids Receptor Antagonists (MRAs)

In the past years, the renewed interest in aldosterone as a mediator of cardiovascular and renal disease, through its blood pressure effects, has resulted in a greater interest in using mineralcorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) to reduce proteinuria and delay CKD progression [80]. A 2009 meta-analysis, updated in 2014, demonstrated that the addition of MRAs to RAS blockade reduced blood pressure and proteinuria in CKD patients [81].

Elevated levels of steroid hormones, such as aldosterone and cortisol, may increase inflammation by inducing the pathological overactivation of the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) in the kidneys and the heart. However, elevated aldosterone release or high salt intake can activate the MR with an inflammatory response that may ultimately lead to organ damage [82].

There are two distinct groups of MRAs: steroidal MRAs (such as spironolactone and eplerenone), and the newer, different, nonsteroidal MRAs.

The use of spironolactone in treating patients with cardiovascular disease has been shown in several clinical studies [83,84], and they represent one of the cornerstones in patients with heart failure due to the improvements in survival, as documented in the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study (RALES) trial [85]. Subsequently, good results were obtained using eplerenone, a more selective steroidal MRA, which improved survival and reduced the rate of hospitalizations for heart failure. These drugs appear to also have beneficial effects on the kidney, improving albuminuria [86].

Therefore, inhibiting the receptor with an MRA could reduce the progression of kidney disease. The main problem with MRAs is an increase in plasma potassium, which in people with CKD often leads to hyperkalemia and sexual side effects (such as gynecomastia). Nonsteroidal MRAs (nMRAs), instead, showed a protection of the kidney and the heart with a better side effect profile, compared with steroidal MRAs. The most developed nMRAs approved are finerenone and esaxerenone. The clinical benefits of the former were evaluated in two randomized, double-blind, place-controlled clinical trials: FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD [87,88] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Clinical trials about the use of nMRAs in diabetic patients with kidney disease.

The FIDELIO-DKD trial [87,89] assessed the long-term efficacy and safety of finerenone vs. placebo in patients with CKD (stage 3 to 4 with eGFR of 25–75 mL/min/1.73 m2) and type 2 diabetes. Patients treated with finerenone experienced an 18% lower risk compared with patients treated with a placebo in the rate of the primary kidney endpoint, which is defined as a composite of time to kidney failure, a sustained decrease of ≥40% in eGFR from baseline over ≥4 weeks, or death from renal causes. The safety profile of finerenone was comparable to that of the placebo, except for hyperkalemia, which occurred at a higher incidence with finerenone (18.3%) than with the placebo (9.0%), but regardless, the levels of hyperkalemia were lower compared with those reported in the literature using RAS blockade in CKD patients.

The FIGARO-DKD trial [88,90] evaluated a wider spectrum of CKD patients (eGFR between 25 and 90 mL/min/1.73 m2) with persistent moderately or elevated albuminuria levels. In this trial 61.7% of patients exhibited mild CKD, showing beneficial effects also in this group of patients.

In a pre-specified individual patient analysis of the FIDELITY-DKD trial [91] patients included in the FIGARO and FIDELIO trials were evaluated over a median follow up of 3 years: a 14% lower risk of the composite CV outcome was reported as well as a reduction in the risk of the composite kidney outcome. Moreover, finerenone decreased the incidence of dialysis initiation by 20%.

Currently, finerenone is recommended in patients with CKD associated with type 2 diabetes to decrease the risk of sustained eGFR decline, ESKD, cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and hospitalization for heart failure [89]. Esaxerenone, instead, has been clinically available in Japan since 2019 for treating hypertension and has been proved to have a higher incidence of urinary albumin remission in patients with type 2 diabetes with high levels of albuminuria treated with a RAS inhibitor [92].

Recently, aldosterone synthase inhibitors (ASis) have emerged as an alternative to MRAs. A phase II clinical study showed a significant improvement of the urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio compared with a placebo with vicadrostat, with or without SGLT2i therapy [93]. Currently, a large-scale randomized trial, the EASi-KIDNEY trial (NCT06531824), is ongoing to evaluate the cardiorenal efficacy and safety of vicadrostat in combination with empaglifozin in patients with CKD with or without diabetes. The composite primary outcomes are kidney disease progression and cardiovascular death from heart failure needing hospitalization [94].

4.5. SGLT-1 Inhibitors

SGLT1i improves glucose metabolism through the reduction in intestinal glucose absorption and increases the release of gastrointestinal incretins. In the kidney, SGLT1i is expressed in the macula densa where it affects glomerular hemodynamics and blood pressure. Evidence has shown the expression of SGLT1 also in the parotid, liver, lung, heart, brain, pancreatic alpha cells, and salivary glands, and the possible effects of SGLT1i on these organs are not fully known [95].

Sotaglifozin is a dual sodium–glucose co-transporter 1 and 2 inhibitor. The SCORED trial has shown a reduction in heart failure complications in patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD. Data from a secondary analysis [96], recently published from the SCORE trial, confirmed the reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events, with the reduction in myocardial infarction and stroke in this group of patients reflecting a possible unique role of SGLT1i compared with SGLT2i alone. Moreover, the drug reduced the risk of the composite of the first event of sustained reduction in eGFR, dialysis, or kidney transplant compared with the placebo, while the incidence of acute kidney injury was similar between the two groups [97].

The adverse events described include diarrhea, genital mycotic infections, volume depletion, and diabetic ketoacidosis. These data confirm the need for more studies to better define the therapeutic potential of SGLT1i inhibition alone or in combination with SGLT2i [95].

4.6. Endothelin Receptor Antagonists

Endothelin-1 promotes mesangial cell proliferation, sclerosis, and direct podocyte injury through the activation of endothelin type A and B receptors, which drive the progression of glomerulosclerosis in diabetic kidney disease [98].

Endotelin receptor antagonists (ERAs), including agents like atrasentan, are under investigation for their anti-fibrotic and hemodynamic effects, with ongoing trials assessing their impact on renal outcomes. Atrasentan antagonizes the vasoconstrictive action of endothelin A receptors within the smooth muscle cells of blood vessels [99].

Clinical trials have studied the effect of the drug in DKD patients with type 2 diabetes, showing an improvement of kidney function, a relative risk reduction in eGFR decline, [100,101] and an improvement of albuminuria levels [102]. However, fluid retention and an increased risk of heart failure associated with ERAs need careful consideration with further trials to optimize dosing and patient selection.

In conclusion, DM and its severe complications, especially DKD, represent an arduous and exciting challenge in the management of the disease and its treatment. Undoubtably, today we have in our hands several effective weapons that can help us in the best management of this disease and its often-dramatic complications. Probably, in the short term, other new drugs will be on the way, providing clinicians with new opportunities that were unthinkable until a few years ago.

5. Special Populations

5.1. Kidney Transplant Recipients

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a prevalent and complex issue among kidney transplant recipients, as the prevalence of pre-existing DM in kidney transplant patients is estimated to be 17.5–30% [46] and represents a growing concern, affecting both the immediate post-transplant period and long-term outcomes [103]. It can be classified into two main types: pre-existing diabetes, which is diagnosed prior to transplantation, and post-transplant diabetes (PTDM), which occurs after the transplant intervention [103]. While pre-transplant diabetes remains associated with an increased risk for mortality after kidney transplantation, mortality outcomes associated with PTDM are time dependent and likely to mature with time [104]. Moreover, PTDM is particularly concerning, as it is closely linked to the use of immunosuppressive medications [105]. The use of immunosuppressive agents, such as steroids, calcineurin inhibitors (e.g., tacrolimus and cyclosporine), and mTOR inhibitors (e.g., sirolimus), significantly contributes to insulin resistance, beta-cell dysfunction, and impaired glucose metabolism [106]. These medications, which are essential to prevent graft rejection, on the other hand, can exacerbate or trigger the development of PTDM [107].

The development of diabetes in kidney transplant recipients increases the risk of various complications, including cardiovascular disease, graft dysfunction, and an increased susceptibility to infections [108]. On the other hand, diabetes often results in an increased acute rejection rate [109]. Furthermore, diabetes exacerbates the risk of CKD progression, placing additional strain on already-compromised renal function. Data show that up to 20–40% of kidney transplant recipients may develop PTDM, depending on various risk factors such as age, ethnicity, obesity, and a history of impaired glucose tolerance [107].

Managing diabetes in kidney transplant recipients is particularly challenging due to the need for a careful balance between blood glucose levels and, at the same time, minimizing the side effects of immunosuppressive therapy. Moreover, treatment strategies must account for the unique pharmacokinetics of immunosuppressive drugs and their potential interactions with antidiabetic medications. Consequently, a multifaceted approach to address both glycemic control and the prevention of complications, while also minimizing the negative effects of immunosuppressive drugs, is required [110,111].

While pharmacologic agents are crucial for glycemic control, adjusting immunosuppressive therapy is equally important. The use of steroid-sparing regimens, such as tacrolimus monotherapy or the use of mycophenolate mofetil instead of steroids, can help minimize the hyperglycemic effects of corticosteroids. Transitioning to sirolimus (an mTOR inhibitor) in select patients may also improve glucose metabolism but requires careful monitoring due to its potential nephrotoxic effects, especially in those with pre-existing kidney dysfunction [111].

In addition to pharmacologic treatment, lifestyle modifications, including dietary counseling and exercise, play a pivotal role in managing diabetes in kidney transplant recipients.

5.2. Pharmacologic Management

- -

- Insulin therapy: Insulin remains the cornerstone of diabetes management in kidney transplant recipients, especially in those with significant hyperglycemia or advanced stages of PTDM. Given the altered pharmacokinetics of insulin in renal failure, dosing adjustments are necessary to avoid hypoglycemia, especially in patients with impaired kidney function [107].

- -

- Oral hypoglycemic agents: The use of oral agents is considered in patients with mild PTDM and preserved renal function. Metformin is generally avoided in patients with significant renal dysfunction due to the risk of lactic acidosis. Sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones can be used cautiously, but their use is often limited by their side effects, including weight gain and fluid retention, which can exacerbate cardiovascular risks [110].

- -

- Glucagon-like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Receptor Agonists: They are increasingly being used in kidney transplant recipients, especially in those with mild to moderate PTDM, especially for the benefit of weight loss [77].

- -

- SGLT2 inhibitors: Their positive cardiovascular and kidney effects make them an attractive option for PTDM in kidney transplant recipients [111,112,113]. A multicenter study involving 750 KTRs recently reported that SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs), including myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality, without increasing the incidence of urinary tract infections (UTIs). Furthermore, a systematic review of 18 studies reported that SGLT2 inhibitors led to modest reductions in HbA1c and body weight, without a significant impact on eGFR or systolic blood pressure [114]. Despite these benefits, concerns remain regarding the potential risk of UTIs, in immunosuppressed patients, and the long-term effects on graft function [114].

6. Future Perspective

Emerging cellular approaches for diabetes management include stem cell therapy, microRNA modulation, gene therapy, and islet transplantation. These advanced therapies are being developed to address the limitations of conventional treatments, particularly the inability to restore endogenous insulin production and the progressive decline of β-cell mass and function seen in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes [115].

Stem cell therapy utilizes pluripotent stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to generate insulin-producing β-like cells or to support endogenous β-cell regeneration. MSCs, especially those derived from adipose tissue, have shown immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects, facilitated β-cell regeneration, and improved insulin sensitivity [116]. Cell-free derivatives such as exosomes are also under investigation for their therapeutic potential [117]. Challenges include immune rejection, tumorigenesis, and ensuring long-term cell survival and function.

Gene therapy and microRNA modulation are being explored to enhance β-cell proliferation, protect against apoptosis, and improve insulin secretion. Gene editing technologies, such as CRISPR/Cas9, are used to correct genetic defects or engineer stem cells for improved therapeutic efficacy [118,119].

Islet transplantation remains a viable option for selected patients with type 1 diabetes but is limited by donor availability and immune-mediated rejection [120]. The use of stem cell-derived islet-like clusters and MSC co-transplantation is being investigated to overcome these barriers and improve graft survival [117,120]

Precision medicine and artificial intelligence (AI) are being increasingly integrated with these approaches. The AI-driven analysis of multi-omics data (including miRNA profiles) and clinical parameters enables improved risk stratification, the identification of therapeutic targets, and the prediction of individual responses to therapy, which is particularly relevant in CKM syndrome given the complex interplay of cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic pathways [121].

In the context of Cardio–Kidney–Metabolic (CKM) syndrome, these cellular therapies have the potential to not only restore glycemic control but also mitigate downstream cardiovascular and renal complications by addressing the root cause—β-cell dysfunction and systemic metabolic dysregulation. The integration of these therapies into clinical practice will require multidisciplinary care models and a careful consideration of their impact on interconnected organ systems [115,116,117].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.G., M.D., M.R.V., A.M.B., M.B., and R.S.; investigation: M.G., A.M.B., M.B., and R.S.; data curation: M.G., M.D., M.R.V., and R.S.; writing—original: M.D., M.R.V., A.M.B., and M.B.; writing—review and editing: M.G. and R.S.; supervision: R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alicic, R.Z.; Rooney, M.T.; Tuttle, K.R. Diabetic Kidney Disease: Challenges, Progress, and Possibilities. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 12, 2032–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman, K.J.; Marquez, N.; Dolgert, A.; Fukutaki, K.; Fullman, N.; McGaughey, M.; Pletcher, M.A.; Smith, A.E.; Tang, K.; Yuan, C.-W.; et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: Reference and alternative scenarios for 2016–40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet 2018, 392, 2052–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, J.S. The discovery of diabetic nephropathy: From small print to centre stage. J. Nephrol. 2006, 19 (Suppl. 10), S75–S87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pugliese, G.; Penno, G.; Natali, A.; Barutta, F.; Di Paolo, S.; Reboldi, G.; Gesualdo, L.; De Nicola, L. Diabetic kidney disease: New clinical and therapeutic issues. Joint position statement of the Italian Diabetes Society and the Italian Society of Nephrology on “The natural history of diabetic kidney disease and treatment of hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes and impaired renal function”. J. Nephrol. 2020, 33, 9–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, P.E.; Ahmed, S.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Foster, B.; Francis, A.; Hall, R.K.; Herrington, W.G.; Hill, G.; Inker, L.A.; Kazancıoğlu, R.; et al. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tervaert, T.W.C.; Mooyaart, A.L.; Amann, K.; Cohen, A.H.; Cook, H.T.; Drachenberg, C.B.; Ferrario, F.; Fogo, A.B.; Haas, M.; de Heer, E.; et al. Pathologic classification of diabetic nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, S.M.; Friedman, A.N. Diagnosis and Management of Type 2 Diabetic Kidney Disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 12, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Li, N.; Wu, Y.; Wang, M.; Yang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Deng, X.; Xiang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, P.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Diabetes-Related Chronic Kidney Disease from 1990 to 2019. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 672350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesualdo, L.; Fiorentino, M.; Conserva, F.; Pontrelli, P. Should we enlarge the indication for kidney biopsy in patients with diabetes? The pro part. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfad266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, T.; Mimura, I.; Tanaka, T.; Nangaku, M. Treatment of Diabetic Kidney Disease: Current and Future. Diabetes Metab. J. 2021, 45, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.A.; Zhang, E.; Natarajan, R. Epigenetic mechanisms in diabetic complications and metabolic memory. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elendu, C.; Okah, M.M.J.; Fiemotongha, K.D.J.M.; Adeyemo, B.I.M.; Bassey, B.N.M.; Omeludike, E.K.M.; Obidigbo, B.M. Comprehensive advancements in the prevention and treatment of diabetic nephropathy: A narrative review. Medicine 2023, 102, e35397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limonte, C.P.; Kretzler, M.; Pennathur, S.; Pop-Busui, R.; de Boer, I.H. Present and future directions in diabetic kidney disease. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2022, 36, 108357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Tuttle, K.R.; Chow, S.L.; Mathew, R.O.; Khan, S.S.; Coresh, J.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; Després, J.-P.; et al. A Synopsis of the Evidence for the Science and Clinical Management of Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) Syndrome: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 148, 1636–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndumele, C.E.; Rangaswami, J.; Chow, S.L.; Neeland, I.J.; Tuttle, K.R.; Khan, S.S.; Coresh, J.; Mathew, R.O.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; et al. Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health: A Presidential Advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 148, 1606–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutruc, V.; Bologa, C.; Șorodoc, V.; Ceasovschih, A.; Morărașu, B.C.; Șorodoc, L.; Catar, O.E.; Lionte, C. Cardiovascular–Kidney–Metabolic Syndrome: A New Paradigm in Clinical Medicine or Going Back to Basics? J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.-K.; Kao, J.T.-W.; Wong, C.-S.; Liao, C.-T.; Lo, W.-C.; Chien, K.-L.; Wen, C.-P.; Wu, M.-S.; Wu, M.-Y. Cardiovascular–kidney–metabolic syndrome and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2025, 22, e1004629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A. Should we enlarge the indication for kidney biopsy in diabetics? The con part. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfad267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penno, G.; Solini, A.; Bonora, E.; Fondelli, C.; Orsi, E.; Zerbini, G.; Trevisan, R.; Vedovato, M.; Gruden, G.; Cavalot, F.; et al. Clinical significance of nonalbuminuric renal impairment in type 2 diabetes. J. Hypertens. 2011, 29, 1802–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulkin, T.V.; Bosman, D.; Krentz, A.J. Contraindications to metformin therapy in patients with NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1997, 20, 925–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.-C.; Chang, Y.-K.; Liu, J.-S.; Kuo, K.-L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Hsu, C.-C.; Tarng, D.-C. Metformin use and mortality in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease: National, retrospective, observational, cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalau, J.D. Lactic acidosis induced by metformin: Incidence, management and prevention. Drug Saf. 2010, 33, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidowsky, A.; Nseir, S.; Houdret, N.; Fourrier, F. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis: A prognostic and therapeutic study. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37, 2191–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, P.; Regolisti, G.; Maggiore, U.; Ferioli, E.; Fani, F.; Locatelli, C.; Parenti, E.; Maccari, C.; Gandolfini, I.; Fiaccadori, E. Sustained low-efficiency dialysis for metformin-associated lactic acidosis in patients with acute kidney injury. J. Nephrol. 2019, 32, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thammavaranucupt, K.; Phonyangnok, B.; Parapiboon, W.; Wongluechai, L.; Pichitporn, W.; Sumrittivanicha, J.; Sungkanuparph, S.; Nongnuch, A.; Jayanama, K. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis and factors associated with 30-day mortality. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, D.; Onisko, N.; Cao, J.D.; Koyfman, A.; Long, B. High risk and low prevalence diseases: Metformin toxicities. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 72, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.J.; Hunsicker, L.G.; Bain, R.P.; Rohde, R.D. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. The Collaborative Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 329, 1456–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.K.; Bullard, K.M.; Saaddine, J.B.; Cowie, C.C.; Imperatore, G.; Gregg, E.W. Achievement of goals in U.S. diabetes care, 1999-2010. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1613–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, P.; Andersen, S.; Rossing, K.; Jensen, B.R.; Parving, H.-H. Dual blockade of the renin-angiotensin system versus maximal recommended dose of ACE inhibition in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003, 63, 1874–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheen, A.J. Renin-angiotensin system inhibition prevents type 2 diabetes mellitus. Part 2. Overview of physiological and biochemical mechanisms. Diabetes Metab. 2004, 30, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.F.; Schmieder, R.E.; McQueen, M.; Dyal, L.; Schumacher, H.; Pogue, J.; Wang, X.; Maggioni, A.; Budaj, A.; Chaithiraphan, S.; et al. Renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet 2008, 372, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, L.F.; Emanuele, N.; Zhang, J.H.; Brophy, M.; Conner, T.A.; Duckworth, W.; Leehey, D.J.; McCullough, P.A.; O’Connor, T.; Palevsky, P.M.; et al. Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1892–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambers Heerspink, H.J.; Weldegiorgis, M.; Inker, L.A.; Gansevoort, R.; Parving, H.-H.; Dwyer, J.P.; Mondal, H.; Coresh, J.; Greene, T.; Levey, A.S.; et al. Estimated GFR decline as a surrogate end point for kidney failure: A post hoc analysis from the Reduction of End Points in Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan (RENAAL) study and Irbesartan Diabetic Nephropathy Trial (IDNT). Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2014, 63, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makino, H.; Haneda, M.; Babazono, T.; Moriya, T.; Ito, S.; Iwamoto, Y.; Kawamori, R.; Takeuchi, M.; Katayama, S. The telmisartan renoprotective study from incipient nephropathy to overt nephropathy–rationale, study design, treatment plan and baseline characteristics of the incipient to overt: Angiotensin II receptor blocker, telmisartan, Investigation on Type 2 Diabetic Nephropathy (INNOVATION) Study. J. Int. Med. Res. 2005, 33, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellemons, M.E.; Persson, F.; Bakker, S.J.; Rossing, P.; Parving, H.-H.; De Zeeuw, D.; Heerspink, H.J.L. Initial angiotensin receptor blockade-induced decrease in albuminuria is associated with long-term renal outcome in type 2 diabetic patients with microalbuminuria: A post hoc analysis of the IRMA-2 trial. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 2078–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viberti, G.; Wheeldon, N.M.; MicroAlbuminuria Reduction with VALsartan (MARVAL) Study Investigators. Microalbuminuria reduction with valsartan in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A blood pressure-independent effect. Circulation 2002, 106, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BENEDICT Group. The BErgamo NEphrologic DIabetes Complications Trial (BENEDICT): Design and baseline characteristics. Control. Clin. Trials 2003, 24, 442–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, G. The ROADMAP trial: Olmesartan for the delay or prevention of microalbuminuria in type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2011, 12, 2421–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohda, T.; Murakoshi, M. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors—Miracle Drugs for the Treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease Irrespective of the Diabetes Status: Lessons from the Dedicated Kidney Disease-Focused CREDENCE and DAPA-CKD Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A. SGLT2 Inhibitors and Kidney Protection: Mechanisms beyond Tubuloglomerular Feedback. Kidney360 2024, 5, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, L.P.; Richardson, P.A.; Nambi, V.; Petersen, L.A.; Matheny, M.E.; Virani, S.S.; Navaneethan, S.D. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitor and Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Discontinuation in Patients with CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2024, 36, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, E.; Zanetti, V.; Macciò, L.; Benizzelli, G.; Carbone, F.; La Porta, E.; Esposito, P.; Verzola, D.; Garibotto, G.; Viazzi, F. SGLT2 inhibition to target kidney aging. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfae133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Reeves, W.B.; Awad, A.S. Pathophysiology of diabetic kidney disease: Impact of SGLT2 inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2021, 17, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günes-Altan, M.; Bosch, A.; Striepe, K.; Bramlage, P.; Schiffer, M.; Schmieder, R.E.; Kannenkeril, D. Is GFR decline induced by SGLT2 inhibitor of clinical importance? Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Fernandez, B.; Sarafidis, P.; Soler, M.J.; Ortiz, A. EMPA-KIDNEY: Expanding the range of kidney protection by SGLT2 inhibitors. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Chen, Q.; Sun, Z.; Liang, G.; Yan, F.; Niu, Y. Pretransplant Diabetes Mellitus and Kidney Transplant Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transplant. Proc. 2024, 56, 2149–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, A.Y.; Tecson, K.M.; Barbin, C.M.; Lee, A.Y.; Lerma, E.V.; Rosol, Z.P.; Rangaswami, J.; Lepor, N.E.; Cobble, M.E.; McCullough, P.A. Cardiorenal Outcomes in the CANVAS, DECLARE-TIMI 58, and EMPA-REG OUTCOME Trials: A Systematic Review. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 19, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkovic, V.; de Zeeuw, D.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Fulcher, G.; Erondu, N.; Shaw, W.; Barrett, T.D.; Weidner-Wells, M.; Deng, H.; Matthews, D.R.; et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: Results from the CANVAS Program randomised clinical trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannad, F.; Ferreira, J.P.; Pocock, S.J.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Brueckmann, M.; Ofstad, A.P.; Pfarr, E.; Jamal, W.; et al. SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: A meta-analysis of the EMPEROR-Reduced and DAPA-HF trials. Lancet 2020, 396, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherney, D.Z.I.; Zinman, B.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Koitka-Weber, A.; Mattheus, M.; von Eynatten, M.; Wanner, C. Effects of empagliflozin on the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio in patients with type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease: An exploratory analysis from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rådholm, K.; Figtree, G.; Perkovic, V.; Solomon, S.D.; Mahaffey, K.W.; de Zeeuw, D.; Fulcher, G.; Barrett, T.D.; Shaw, W.; Desai, M.; et al. Canagliflozin and Heart Failure in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Results from the CANVAS Program. Circulation 2018, 138, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplinsky, E. DAPA-HF trial: Dapagliflozin evolves from a glucose-lowering agent to a therapy for heart failure. Drugs Context 2020, 9, 2019-11-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somagutta, M.R.; Agadi, K.; Hange, N.; Jain, M.S.; Batti, E.; Emuze, B.O.; Amos-Arowoshegbe, E.O.; Popescu, S.; Hanan, S.; Kumar, V.R.; et al. Euglycemic Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors: A Focused Review of Pathophysiology, Risk Factors, and Triggers. Cureus 2021, 13, e13665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlKindi, F.; Boobes, Y.; Shalwani, F.; Ansari, J.; Almazrouei, R. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitor (SGLT2i) Associated Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Oncology Patients: A Case Series and Literature Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e53816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.J.; Oshima, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Agarwal, R.; Capuano, G.; Charytan, D.M.; Craig, J.; de Zeeuw, D.; Di Tanna, G.L.; et al. Canagliflozin and Kidney-Related Adverse Events in Type 2 Diabetes and CKD: Findings from the Randomized CREDENCE Trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2022, 79, 244–256.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.C.; Stefansson, B.V.; Batiushin, M.; Bilchenko, O.; Cherney, D.Z.I.; Chertow, G.M.; Douthat, W.; Dwyer, J.P.; Escudero, E.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; et al. TThe dapagliflozin and prevention of adverse outcomes in chronic kidney disease (DAPA-CKD) trial: Baseline characteristics. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2020, 35, 1700–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.J.; AlSaffar, A.H.; Mohamed, A.A.; Khamis, M.H.; Khalaf, A.A.; AlAradi, H.J.; Abuhamaid, A.I.; Sanad, A.H.; Abbas, H.L.; Abdulla, A.M.; et al. Effect of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists on Renal Functions and Diabetic Nephropathy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2024, 16, e71739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michos, E.D.; Tuttle, K.R. GLP-1 receptor agonists in diabetic kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 16, 1578–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marso, S.P.; Daniels, G.H.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Kristensen, P.; Mann, J.F.E.; Nauck, M.A.; Nissen, S.E.; Pocock, S.; Poulter, N.R.; Ravn, L.S.; et al. Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marso, S.P.; Bain, S.C.; Consoli, A.; Eliaschewitz, F.G.; Jódar, E.; Leiter, L.A.; Lingvay, I.; Rosenstock, J.; Seufert, J.; Warren, M.L.; et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1834–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstein, H.C.; Colhoun, H.M.; Dagenais, G.R.; Diaz, R.; Lakshmanan, M.; Pais, P.; Probstfield, J.; Riesmeyer, J.S.; Riddle, M.C.; Rydén, L.; et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): A double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, D.K.; Marx, N.; Mulvagh, S.L.; Deanfield, J.E.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Pop-Busui, R.; Mann, J.F.; Emerson, S.S.; Poulter, N.R.; Engelmann, M.D.; et al. Oral Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in High-Risk Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 2001–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaris, N.; Waldrop, S.; Johnson, V.; Boaventura, B.; Kendrick, K.; Stanford, F.C. GLP-1 single, dual, and triple receptor agonists for treating type 2 diabetes and obesity: A narrative review. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 75, 102782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossing, P.; Baeres, F.M.M.; Bakris, G.; Bosch-Traberg, H.; Gislum, M.; Gough, S.C.L.; Idorn, T.; Lawson, J.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Mann, J.F.E.; et al. The rationale, design and baseline data of FLOW, a kidney outcomes trial with once-weekly semaglutide in people with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 38, 2041–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Liang, X.; Sun, N.; Zhang, D. Influence of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on renal parameters: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2025, 25, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; An, J.N.; Song, Y.R.; Kim, S.G.; Lee, H.S.; Cho, A.; Kim, J.-K. Effect of once-weekly dulaglutide on renal function in patients with chronic kidney disease. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botros, F.T.; Gerstein, H.C.; Malik, R.; Nicolay, C.; Hoover, A.; Turfanda, I.; Colhoun, H.M.; Shaw, J.E. Dulaglutide and Kidney Function–Related Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes: A REWIND Post Hoc Analysis. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 1524–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaffey, K.W.; Tuttle, K.R.; Arici, M.; Baeres, F.M.M.; Bakris, G.; Charytan, D.M.; Cherney, D.Z.I.; Chernin, G.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Gumprecht, J.; et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with semaglutide by severity of chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes: The FLOW trial. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 46, 1096–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff, A.M.; Kaplan, L.M.; Frías, J.P.; Wu, Q.; Du, Y.; Gurbuz, S.; Coskun, T.; Haupt, A.; Milicevic, Z.; Hartman, M.L. Triple–Hormone-Receptor Agonist Retatrutide for Obesity—A Phase 2 Trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.L.; Lu, Z.; DU, Y.; Duffin, K.L.; Coskun, T.; Haupt, A.; Hartman, M.L. 754-P: Effect of Retatrutide on Kidney Parameters in People with Type 2 Diabetes and/or Obesity—A Post-Hoc Analysis of Two Phase 2 Trials. Diabetes 2024, 73 (Suppl. 1), 754-P. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Sattar, N.; Pavo, I.; Haupt, A.; Duffin, K.L.; Yang, Z.; Wiese, R.J.; Tuttle, K.R.; Cherney, D.Z.I. Effects of tirzepatide versus insulin glargine on kidney outcomes in type 2 diabetes in the SURPASS-4 trial: Post-hoc analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Bradley, R.M.; Auerbach, P.; Abitbol, A. Real-world impact of adding a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist compared with basal insulin on metabolic targets in adults living with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease already treated with a sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor: The Impact GLP-1 CKD study. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 4674–4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colhoun, H.M.; Lingvay, I.; Brown, P.M.; Deanfield, J.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Kahn, S.E.; Plutzky, J.; Node, K.; Parkhomenko, A.; Rydén, L.; et al. Long-term kidney outcomes of semaglutide in obesity and cardiovascular disease in the SELECT trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2058–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praga, M.; Morales, E. Obesity-related renal damage: Changing diet to avoid progression. Kidney Int. 2010, 78, 633–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, A.N.; Yu, Z.; Juliar, B.E.; Nguyen, J.T.; Strother, M.; Quinney, S.K.; Li, L.; Inman, M.; Gomez, G.; Shihabi, Z.; et al. Independent influence of dietary protein on markers of kidney function and disease in obesity. Kidney Int. 2010, 78, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ussher, J.R.; Drucker, D.J. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists: Cardiovascular benefits and mechanisms of action. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, I.H.; Caramori, M.L.; Chan, J.C.; Heerspink, H.J.; Khunti, K.; Liew, A.; Michos, E.D.; Navaneethan, S.D.; Olowu, W.A.; Sadusky, T.; et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and other incretin mimetics for diabetes and chronic kidney disease—A KDIGO commentary. Kidney Int. 2025, 107, 767–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaman, A.M.; Bain, S.C.; Bakris, G.L.; Buse, J.B.; Idorn, T.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Mann, J.F.E.; Nauck, M.A.; Rasmussen, S.; Rossing, P.; et al. Effect of the glucagon-likePeptide-1 receptor agonists Semaglutide and liraglutide on kidneyoutcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: Pooled analysis of SUS-TAIN 6 and LEADER. Circulation 2022, 145, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michos, E.D.; Bakris, G.L.; Rodbard, H.W.; Tuttle, K.R. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in diabetic kidney disease: A review of their kidney and heart protection. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2023, 14, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, G.; Taylor, A.H.M.; Fujita, T.; Ohtsu, H.; Lindhardt, M.; Rossing, P.; Boesby, L.; Edwards, N.C.; Ferro, C.J.; Townend, J.N.; et al. Effect of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists on proteinuria and progression of chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2016, 17, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaneethan, S.D.; Nigwekar, S.U.; Sehgal, A.R.; Strippoli, G.F.M. Aldosterone antagonists for preventing the progression of chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 4, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauersachs, J.; Jaisser, F.; Toto, R. Mineralocorticoid receptor activation and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist treatment in cardiac and renal diseases. Hypertension 2015, 65, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, B.; Remme, W.; Zannad, F.; Neaton, J.; Martinez, F.; Roniker, B.; Bittman, R.; Hurley, S.; Kleiman, J.; Gatlin, M. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zannad, F.; McMurray, J.J.; Krum, H.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Swedberg, K.; Shi, H.; Vincent, J.; Pocock, S.J.; Pitt, B. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, B.; Zannad, F.; Remme, W.J.; Cody, R.; Castaigne, A.; Perez, A.; Palensky, J.; Wittes, J. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrou, M.-E.; Papagianni, A.; Tsapas, A.; Loutradis, C.; Boutou, A.; Piperidou, A.; Papadopoulou, D.; Ruilope, L.; Bakris, G.; Sarafidis, P. Effects of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in proteinuric kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Hypertens. 2019, 37, 2307–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Joseph, A.; Anker, S.D.; Filippatos, G.; Rossing, P.; Ruilope, L.M.; Pitt, B.; Kolkhof, P.; Scott, C.; Lawatscheck, R.; et al. Hyperkalemia Risk with Finerenone: Results from the FIDELIO-DKD Trial. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 33, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippatos, G.; Anker, S.D.; Agarwal, R.; Ruilope, L.M.; Rossing, P.; Bakris, G.L.; Tasto, C.; Joseph, A.; Kolkhof, P.; Lage, A.; et al. Finerenone Reduces Risk of Incident Heart Failure in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: Analyses from the FIGARO-DKD Trial. Circulation 2022, 145, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakris, G.L.; Agarwal, R.; Anker, S.D.; Pitt, B.; Ruilope, L.M.; Rossing, P.; Kolkhof, P.; Nowack, C.; Schloemer, P.; Joseph, A.; et al. Effect of Finerenone on Chronic Kidney Disease Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2219–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, B.; Filippatos, G.; Agarwal, R.; Anker, S.D.; Bakris, G.L.; Rossing, P.; Joseph, A.; Kolkhof, P.; Nowack, C.; Schloemer, P.; et al. Cardiovascular Events with Finerenone in Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 2252–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Filippatos, G.; Pitt, B.; Anker, S.D.; Rossing, P.; Joseph, A.; Kolkhof, P.; Nowack, C.; Gebel, M.; Ruilope, L.M.; et al. Cardiovascular and kidney outcomes with finerenone in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: The FIDELITY pooled analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, S.; Kashihara, N.; Shikata, K.; Nangaku, M.; Wada, T.; Okuda, Y.; Sawanobori, T. Esaxerenone (CS-3150) in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Microalbuminuria (ESAX-DN): Phase 3 Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 15, 1715–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttle, K.R.; Hauske, S.J.; Canziani, M.E.; Caramori, M.L.; Cherney, D.; Cronin, L.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Hugo, C.; Nangaku, M.; Rotter, R.C.; et al. Efficacy and safety of aldosterone synthase inhibition with and without empagliflozin for chronic kidney disease: A randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2024, 403, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, P.K.; Tuttle, K.R.; Staplin, N.; Hauske, S.J.; Zhu, D.; Sardell, R.; Cronin, L.; Green, J.B.; Agrawal, N.; Arimoto, R.; et al. The potential for improving cardio-renal outcomes in chronic kidney disease with the aldosterone synthase inhibitor vicadrostat (BI 690517): A rationale for the EASi-KIDNEY trial. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2025, 40, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oe, Y.; Vallon, V. The Pathophysiological Basis of Diabetic Kidney Protection by Inhibition of SGLT2 and SGLT1. Kidney Dial. 2022, 2, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Bhatt, D.L.; Szarek, M.; Cannon, C.P.; Leiter, L.A.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Lopes, R.D.; McGuire, D.K.; Lewis, J.B.; Riddle, M.C.; et al. Effect of sotagliflozin on major adverse cardiovascular events: A prespecified secondary analysis of the SCORED randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, V.S.; Bhatt, D.L.; Odutayo, A.; Szarek, M.; Davies, M.J.; Banks, P.; Pitt, B.; Steg, P.G.; Cherney, D.Z. Sotagliflozin and Kidney Outcomes, Kidney Function, and Albuminuria in Type 2 Diabetes and CKD: A Secondary Analysis of the SCORED Trial. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2024, 19, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empitu, M.A.; Rinastiti, P.; Kadariswantiningsih, I.N. Targeting endothelin signaling in podocyte injury and diabetic nephropathy-diabetic kidney disease. J. Nephrol. 2025, 38, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, N.; James, S.; Coughlan, M.T.; MacIsaac, R.J.; Ekinci, E.I. Novel Therapies for Kidney Disease in People with Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, e1–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Parving, H.-H.; Andress, D.L.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Hou, F.-F.; Kitzman, D.W.; Kohan, D.; Makino, H.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Melnick, J.Z.; et al. Atrasentan and renal events in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (SONAR): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 1937–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zeeuw, D.; Coll, B.; Andress, D.; Brennan, J.J.; Tang, H.; Houser, M.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Kohan, D.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Makino, H.; et al. The endothelin antagonist atrasentan lowers residual albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andress, D.L.; Coll, B.; Pritchett, Y.; Brennan, J.; Molitch, M.; Kohan, D.E. Clinical efficacy of the selective endothelin A receptor antagonist, atrasentan, in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Life Sci. 2012, 91, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.; Suvarna, R.; Awasthi, A.; Bhojaraja, M.V.; Pappachan, J.M. Emerging Biomarkers and Innovative Therapeutic Strategies in Diabetic Kidney Disease: A Pathway to Precision Medicine. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.; Culliford, A.; Phagura, N.; Evison, F.; Gallier, S.; Sharif, A. Comparing survival outcomes for kidney transplant recipients with pre-existing diabetes versus those who develop post-transplantation diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2022, 39, e14707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfieri, C.; Campioli, E.; Fiorina, P.; Orsi, E.; Grancini, V.; Regalia, A.; Campise, M.; Verdesca, S.; Delfrate, N.W.; Molinari, P.; et al. Post-Transplant Diabetes Mellitus in Kidney-Transplanted Patients: Related Factors and Impact on Long-Term Outcome. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourad, G.; Glyda, M.; Albano, L.; Viklický, O.; Merville, P.; Tydén, G.; Mourad, M.; Lõhmus, A.; Witzke, O.; Christiaans, M.H.L.; et al. Incidence of Posttransplantation Diabetes Mellitus in de Novo Kidney Transplant Recipients Receiving Prolonged-Release Tacrolimus-Based Immunosuppression with 2 Different Corticosteroid Minimization Strategies: ADVANCE, A Randomized Controlled Trial. Transplantation 2017, 101, 1924–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbay, M.; Copur, S.; Topçu, A.U.; Guldan, M.; Ozbek, L.; Gaipov, A.; Ferro, C.; Cozzolino, M.; Cherney, D.Z.I.; Tuttle, K.R. An update review of post-transplant diabetes mellitus: Concept, risk factors, clinical implications and management. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 2531–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B.; Radek, M.; Ciałkowska-Rysz, A.; Gluba-Brzózka, A. Diabetes and cardiovascular risk in renal transplant patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonato, V.; Barni, R.; Cataldo, D.; Collini, A.; Ruggieri, G.; De Bartolomeis, C.; Dotta, F.; Carmellini, M. Analysis of Posttransplant Diabetes Mellitus Prevalence in a Population of Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplant. Proc. 2008, 40, 1888–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghrib, Y.; Hilbrands, L.; Oniscu, G.C.; Crespo, M.; Gandolfini, I.; Mariat, C.; Mjøen, G.; Sever, M.S.; Watschinger, B.; Velioglu, A.; et al. Current practices in prevention, screening, and treatment of diabetes in kidney transplant recipients: European survey highlights from the ERA DESCARTES Working Group. Clin. Kidney J. 2025, 18, sfae367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, V.S.; Ambinathan, J.P.N.; Gillard, P.; Mathieu, C.; Cherney, D.Z.; Lytvyn, Y.; Singh, S.K. Cardiometabolic and Kidney Protection in Kidney Transplant Recipients With Diabetes: Mechanisms, Clinical Applications, and Summary of Clinical Trials. Transplantation 2022, 106, 734–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.-H.; Kwon, S.; Jeon, Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Kwon, H.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.-L.; Kim, C.-D.; Park, S.-H.; et al. The Efficacy and Safety of SGLT2 Inhibitor in Diabetic Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 2022, 106, E404–E412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, A.; Chakkera, H.; de Vries, A.P.J.; Eller, K.; Guthoff, M.; Haller, M.C.; Hornum, M.; Nordheim, E.; Kautzky-Willer, A.; Krebs, M.; et al. International consensus on post-transplantation diabetes mellitus. In Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2024; Volume 39, pp. 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellos, I.; Lagiou, P.; Benetou, V.; Marinaki, S. Safety and Efficacy of Sodium-Glucose Transport Protein 2 Inhibitors and Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Diabetic Kidney Transplant Recipients: Synthesis of Evidence. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siehler, J.; Blöchinger, A.K.; Meier, M.; Lickert, H. Engineering islets from stem cells for advanced therapies of diabetes. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 920–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikłosz, A.; Chabowski, A. Adipose-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Therapy as a new Treatment Option for Diabetes Mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 1889–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.T.; Dadheech, N.; Tan, E.H.P.; Ng, N.H.J.; Koh, M.B.C.; Shapiro, J.; Teo, A.K.K. Stem cell therapies for diabetes. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2147–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madkor, H.R.; Abd El-Aziz, M.K.; El-Maksoud, M.S.A.; Ibrahim, I.M.; Ali, F.E.M. Stem Cells Reprogramming in Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetic Complications: Recent Advances. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2025, 21, e010124225101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.M.I. Advancing diabetes management: Exploring pancreatic beta-cell restoration’s potential and challenges. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 4339–4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, L.; Wang, T.B.; Wang, X.; Pu, Z. Advancing diabetes treatment: The role of mesenchymal stem cells in islet transplantation. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1389134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccali, C.; Mallamaci, F.; Lightstone, L.; Jha, V.; Pollock, C.; Tuttle, K.; Kotanko, P.; Wiecek, A.; Anders, H.J.; Remuzzi, G.; et al. A new era in the science and care of kidney diseases. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]