Impact of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on Age at Death in the Hemodialysis Population: An Analysis of Data from the Korean National Health Insurance and Statistical Information Service, 2006 to 2018

Abstract

1. Introduction

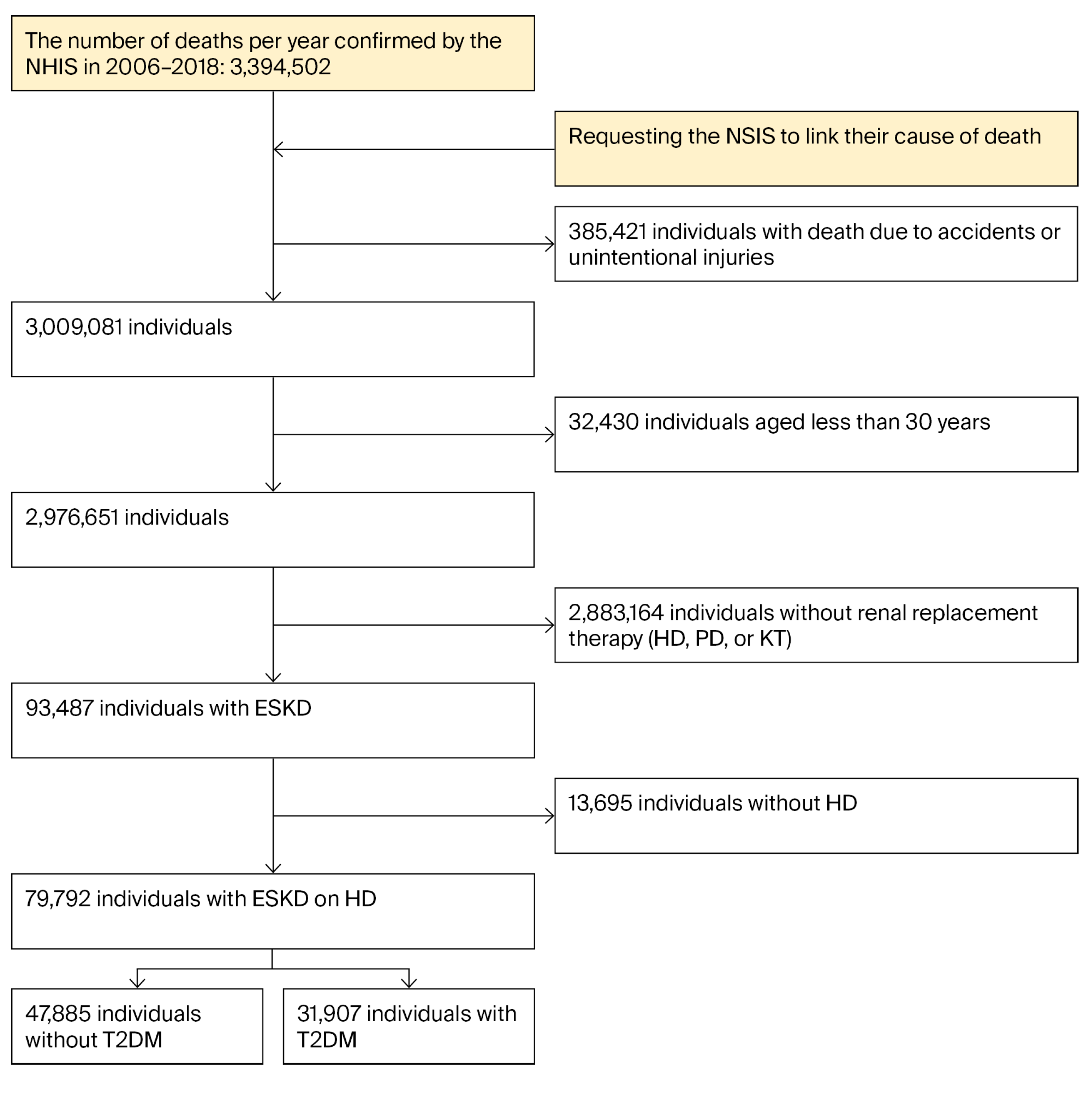

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Definition and Death Certificates

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Availability of Data and Materials

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

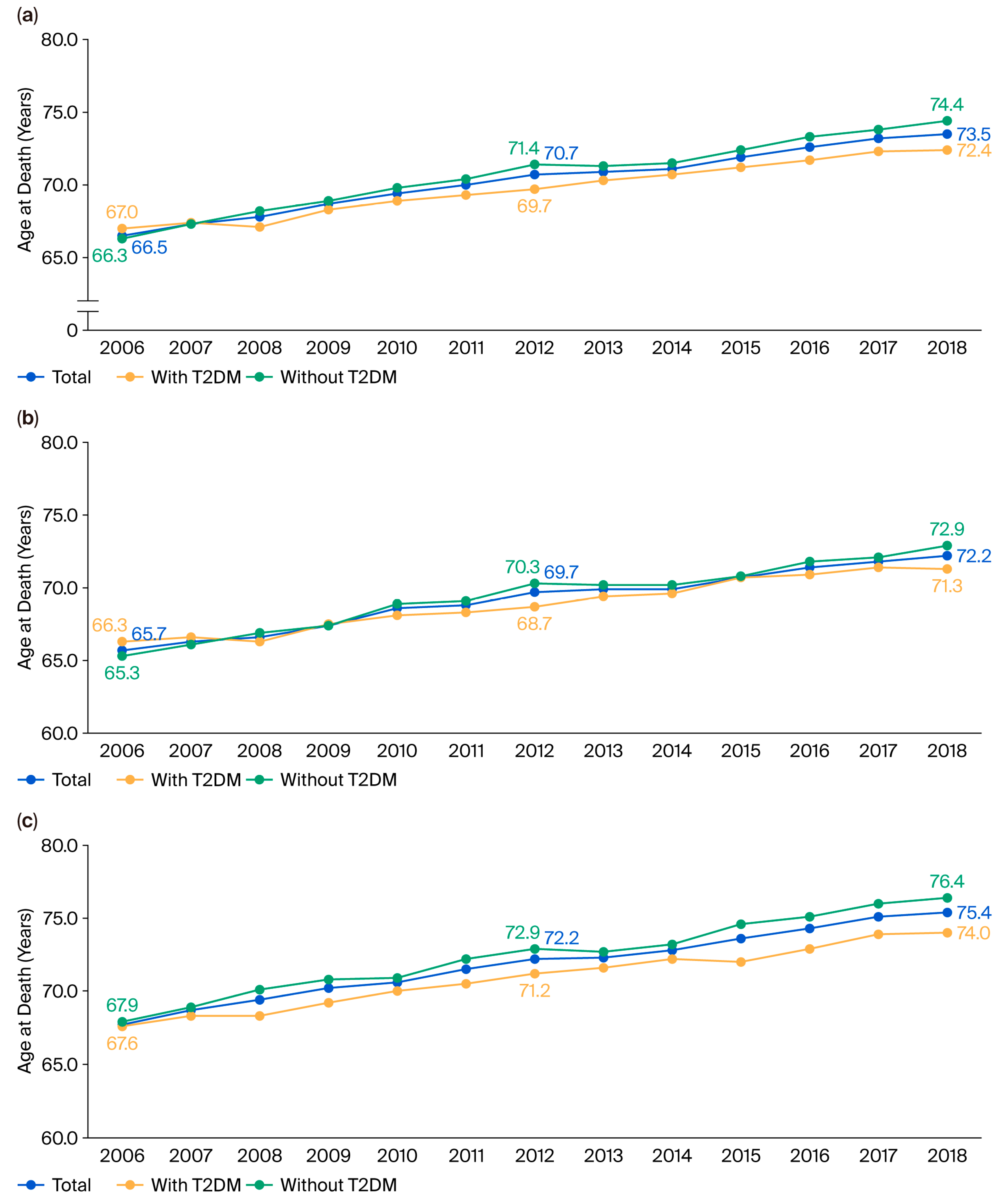

3.2. Changes in the Mean Age of Death in the Study Population

3.3. Factors That Contributed to Age at Death in the Study Population

3.4. Age-Standardized Mortality Rate in the Study Population

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, M.J.; Ha, K.H.; Kim, D.J.; Park, I. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Mortality of End-Stage Kidney Disease in South Korea. Diabetes Metab. J. 2020, 44, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forst, T.; Mathieu, C.; Giorgino, F.; Wheeler, D.C.; Papanas, N.; Schmieder, R.E.; Halabi, A.; Schnell, O.; Streckbein, M.; Tuttle, K.R. New strategies to improve clinical outcomes for diabetic kidney disease. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.M.; Jeong, S.A.; Ban, T.H.; Hong, Y.A.; Hwang, S.D.; Choi, S.R.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, T.H.; et al. Status and trends in epidemiologic characteristics of diabetic end-stage renal disease: An analysis of the 2021 Korean Renal Data System. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2024, 43, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheith, O.; Farouk, N.; Nampoory, N.; Halim, M.A.; Al-Otaibi, T. Diabetic kidney disease: World wide difference of prevalence and risk factors. J. Nephropharmacol. 2016, 5, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.H.; Seo, M.H.; Jung, J.H.; Han, K.D.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, N.H. 2023 Diabetic Kidney Disease Fact Sheet in Korea. Diabetes Metab. J. 2024, 48, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.C.; Kim, D.H.; Cho, A.; Kim, B.Y.; Lee, M.; Kim, G.O.; Kim, J.; Lee, Y.K. Remaining life expectancy of Korean hemodialysis patients: How much longer can they live? Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2024, 43, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderian, S.B.; Hayati, F.; Shayanpour, S.; Beladi Mousavi, S.S. Diabetes and end-stage renal disease; a review article on new concepts. J. Renal. Inj. Prev. 2015, 4, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Guo, Z.; Li, D.T.; Zhao, L.Y.; Wang, Z.; Gao, Y.B.; Wang, Y.X. The association between stress-induced hyperglycemia ratio and cardiovascular events as well as all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease and diabetic nephropathy. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E.; Song, S.O.; Kim, H.S.; Son, K.J.; Jee, S.H.; Cha, B.S.; Lee, B.W. Improvement in Age at Mortality and Changes in Causes of Death in the Population with Diabetes: An Analysis of Data from the Korean National Health Insurance and Statistical Information Service, 2006 to 2018. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 37, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Song, S.O.; Noh, J.; Jeong, I.K.; Lee, B.W. Data Configuration and Publication Trends for the Korean National Health Insurance and Health Insurance Review & Assessment Database. Diabetes Metab. J. 2020, 44, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koye, D.N.; Magliano, D.J.; Nelson, R.G.; Pavkov, M.E. The Global Epidemiology of Diabetes and Kidney Disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2018, 25, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, R.N.; Collins, A.J. End-stage renal disease in the United States: An update from the United States Renal Data System. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 18, 2644–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, D.C.; Yun, S.R.; Lee, S.W.; Han, S.W.; Kim, W.; Park, J.; Kim, Y.K. Lessons from 30 years’ data of Korean end-stage renal disease registry, 1985–2015. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2015, 34, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.O.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, D.W.; Song, Y.D.; Nam, J.Y.; Park, K.H.; Kim, D.J.; Park, S.W.; Lee, H.C.; Lee, B.W. Trends in Diabetes Incidence in the Last Decade Based on Korean National Health Insurance Claims Data. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 31, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgmehri, S.; Aboud, H.; Chamarthi, G.; Liu, I.C.; Tezcan, O.B.; Shukla, A.M.; Kazory, A.; Rupam, R.; Segal, M.S.; Bihorac, A.; et al. Association of early initiation of dialysis with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: A propensity score weighted analysis of the United States Renal Data System. Hemodial. Int. 2021, 25, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.K.; Zhou, H.; Shaw, S.F.; Shi, J.; Tilluckdharry, N.S.; Rhee, C.M.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Sim, J.J. Causes of Death in End-Stage Kidney Disease: Comparison between the United States Renal Data System and a Large Integrated Health Care System. Am. J. Nephrol. 2022, 53, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.M.; Zhang, J.; Morgenstern, H.; Bradbury, B.D.; Ng, L.J.; McCullough, K.P.; Gillespie, B.W.; Hakim, R.; Rayner, H.; Fort, J.; et al. Worldwide, mortality risk is high soon after initiation of hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2014, 85, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, P.; Xu, Z.; Lu, Z.; Yang, C.; Ning, J. Association of diabetes with cardiovascular calcification and all-cause mortality in end-stage renal disease in the early stages of hemodialysis: A retrospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couchoud, C.; Labeeuw, M.; Moranne, O.; Allot, V.; Esnault, V.; Frimat, L.; Stengel, B. A clinical score to predict 6-month prognosis in elderly patients starting dialysis for end-stage renal disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009, 24, 1553–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiris, D.; Jones, E.H.; Briggs, J.D.; Elinder, C.G.; Mehls, O.; Mendel, S.; Piccoli, G.; Rigden, S.P.; Pintos dos Santos, J.; Simpson, K.; et al. Deaths within 90 days from starting renal replacement therapy in the ERA-EDTA Registry between 1990 and 1992. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1999, 14, 2343–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.M.; Jamil, A.; Khan, Z.; Shakoor, M.; Kamal, U.H.; Khan, I.I.; Akram, A.; Shahabi, M.; Yamani, N.; Ali, S.; et al. Trends in mortality related to kidney failure and diabetes mellitus in the United States: A 1999–2020 analysis. J. Nephrol. 2024, 37, 1833–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.K.; Ko, G.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Jeong, K.H.; Moon, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Hwang, H.S. Glycated hemoglobin levels and risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality in hemodialysis patients with diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 190, 110016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, A.J.; Foley, R.N.; Gilbertson, D.T.; Chen, S.C. The state of chronic kidney disease, ESRD, and morbidity and mortality in the first year of dialysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 4 (Suppl. S1), S5–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, A.J.; Foley, R.N.; Gilbertson, D.T.; Chen, S.C. United States Renal Data System public health surveillance of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2015, 5, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriadis, T.; Liakopoulos, V.; Leivaditis, K.; Antoniadi, G.; Stefanidis, I. Infections in hemodialysis: A concise review—Part 1: Bacteremia and respiratory infections. Hippokratia 2011, 15, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- de Lourdes Ochoa-González, F.; González-Curiel, I.E.; Cervantes-Villagrana, A.R.; Fernández-Ruiz, J.C.; Castañeda-Delgado, J.E. Innate Immunity Alterations in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Understanding Infection Susceptibility. Curr. Mol. Med. 2021, 21, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischereder, M. Cancer in patients on dialysis and after renal transplantation. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2008, 23, 2457–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.H.; Vajdic, C.M.; van Leeuwen, M.T.; Amin, J.; Webster, A.C.; Chapman, J.R.; McDonald, S.P.; Grulich, A.E.; McCredie, M.R. The pattern of excess cancer in dialysis and transplantation. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009, 24, 3225–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Individuals Without T2DM (n = 47,885) | Individuals with T2DM (n = 31,907) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at death, years | 71.1 ± 12.4 | 70.2 ± 10.5 | <0.0001 |

| Age groups at death, n (%), years | <0.001 | ||

| 30–39 | 656 (1.4) | 173 (0.5) | |

| 40–49 | 2326 (4.9) | 981 (3.1) | |

| 50–59 | 5756 (12.0) | 3996 (12.5) | |

| 60–69 | 9821 (20.5) | 8573 (26.9) | |

| 70–79 | 16,209 (33.9) | 12,161 (38.1) | |

| ≥80 | 13,117 (27.4) | 6023 (18.9) | |

| Sex, males, n (%) | 27,350 (57.1) | 18,953 (59.4) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 35,680 (74.5) | 29,752 (93.3) | <0.0001 |

| Years from HD to death | 3.74 ± 3.5 | 2.09 ± 3.1 | <0.0001 |

| Age at HD, years | 67.4 ± 13.1 | 67.2 ± 11.1 | 0.032 |

| Cause of death | <0.0001 | ||

| Malignancy, n (%) | 5564 (11.6) | 2757 (8.6) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 2688 (5.6) | 1471 (4.6) | |

| Heart disease, n (%) | 2562 (5.4) | 1753 (5.5) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 6381 (13.3) | 11,939 (37.4) | |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 952 (2.0) | 414 (1.3) | |

| Others, n (%) | 28,682 (59.9) | 12,884 (40.4) |

| Parameter | β | Standard Error | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.0275 |

| Diabetes | −0.012 | 0.003 | <0.0001 |

| HTN | −0.047 | 0.004 | <0.0001 |

| Age at HD initiation for ESKD | 0.998 | 0.000 | <0.0001 |

| Duration in years from HD initiation to death | 0.985 | 0.000 | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | Cancer | Cardiovascular Disease | Cerebrovascular Disease | Pneumonia | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | With Diabetes | Without Diabetes | Overall | With Diabetes | Without Diabetes | Overall | With Diabetes | Without Diabetes | Overall | With Diabetes | Without Diabetes | Overall | With Diabetes | Without Diabetes | |

| 2006 | 25.4 | 46.6 | 14.7 | 10.9 | 7.3 | 12.6 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 5.5 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| 2007 | 23.9 | 43.1 | 12.1 | 10.1 | 6.3 | 12.5 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 5.1 | 6.5 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.1 |

| 2008 | 21.8 | 37.9 | 11. | 9.0 | 6.2 | 10.8 | 5.1 | 5.6 | 4.9 | 5.7 | 4.9 | 6.2 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 1.8 |

| 2009 | 22.4 | 39.2 | 12.0 | 11.1 | 7.8 | 13.1 | 5.1 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 5.6 | 4.6 | 6.2 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| 2010 | 23. | 40.0 | 12.7 | 11.1 | 8.1 | 13.1 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 4.2 | 6. | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| 2011 | 28.3 | 47.0 | 16.0 | 9.6 | 7.9 | 10.7 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 3.4 | 5.6 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| 2012 | 27.6 | 44.0 | 16.7 | 10.6 | 9.4 | 11.3 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 3.4 | 5.1 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.2 |

| 2013 | 26. | 42.7 | 16.2 | 10.9 | 9.3 | 11.9 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| 2014 | 23.7 | 37.6 | 14.7 | 10.7 | 9.1 | 11.7 | 5.6 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 5.8 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.6 |

| 2015 | 21.9 | 34.1 | 14.2 | 10.9 | 9.3 | 12.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.9 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 5.3 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| 2016 | 20. | 31.7 | 11.5 | 10.4 | 9.8 | 10.9 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 3.1 |

| 2017 | 18.8 | 29.2 | 11.0 | 10.3 | 9.4 | 11.0 | 6.6 | 7.4 | 6.1 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 5.6 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.2 |

| 2018 | 19.5 | 30.3 | 11.1 | 10.1 | 9.2 | 10.7 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 5.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

You, J.H.; Son, K.J.; Park, K.S.; Lee, B.-W.; Song, S.O. Impact of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on Age at Death in the Hemodialysis Population: An Analysis of Data from the Korean National Health Insurance and Statistical Information Service, 2006 to 2018. Diabetology 2025, 6, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120145

You JH, Son KJ, Park KS, Lee B-W, Song SO. Impact of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on Age at Death in the Hemodialysis Population: An Analysis of Data from the Korean National Health Insurance and Statistical Information Service, 2006 to 2018. Diabetology. 2025; 6(12):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120145

Chicago/Turabian StyleYou, Ji Hong, Kang Ju Son, Kyoung Sook Park, Byung-Wan Lee, and Sun Ok Song. 2025. "Impact of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on Age at Death in the Hemodialysis Population: An Analysis of Data from the Korean National Health Insurance and Statistical Information Service, 2006 to 2018" Diabetology 6, no. 12: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120145

APA StyleYou, J. H., Son, K. J., Park, K. S., Lee, B.-W., & Song, S. O. (2025). Impact of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on Age at Death in the Hemodialysis Population: An Analysis of Data from the Korean National Health Insurance and Statistical Information Service, 2006 to 2018. Diabetology, 6(12), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120145