Abstract

Pineapple processing generates substantial waste, which has the potential to be valorized according to circular economy principles. This study aimed to estimate the amount of waste generation from the pineapple industry and demonstrate its valorization by producing pectin-based hydrogels for fat replacement in reduced-fat sausages, in addition to cellulose-derived edible films for sausage casings. An analysis of the pineapple sector in Thailand, covering 2015–2024, revealed an average annual pineapple waste generation of 670,698 tons. The crude fiber content in pineapple waste was found to be 15–33%. In this study, pectin was successfully extracted using citric acid under microwave digestion for 10 min. Through the combination of extracted and commercial pectins, a hydrogel (fat replacer) could be formed following the incorporation of calcium residue in fish bone powder. Substituting this hydrogel for 25% fat in sausage recipes reduced fat content while improving textural properties and water-holding capacities. The reduced-fat sausage, wrapped with edible film made from gelatin and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) derived from pineapple waste, exhibited physicochemical stability, as evidenced by its unchanged color and pH during cold storage for 5 days. Storing this type of sausage within films containing CMC from pineapple waste exhibited superior antioxidative properties compared to those wrapped with commercial films. Our results indicated that polysaccharide residues in pineapple waste can be valorized to produce reduced-fat sausages and casings, supporting upcycling policies and waste management strategies.

1. Introduction

Pineapple is a major economic crop both globally and in Thailand, generating substantial income for farmers and contributing significantly to national export revenues. In 2022, global production reached 28.99 million tons, with Thailand contributing 1.714 million tons (5.91% of global output), establishing the country as a leading canned pineapple exporter, with export values of USD 460.51 million and a total export value of USD 683.22 million [1]. Thailand allocates 70–80% of its pineapple production to processing factories for export, while the remaining 20–30% is used for domestic consumption. Cultivation is concentrated in western and eastern regions, producing 1,075,537 tons from 294,262 rai in 2024, with average yields of 3655 kg/rai and factory prices of THB 11.88 per kilogram [2]. This extensive processing industry generates substantial organic waste, including peels, pomace, cores, and crown, representing approximately 40–60% of the fruit’s weight. Based on significant production volume and the economic importance of pineapple processing in Thailand, both environmental benefits and additional revenue streams are yielded when this waste is upcycled into value-added products, whereby circular economy principles are supported, and processor disposal costs are concurrently reduced.

The circular economy concept transforms the linear economic model—which focuses on producing goods for disposal after consumption—into a sustainable approach that emphasizes the efficient reuse and recycling of agro-industrial waste [3]. This circular economy model for agro-industrial waste aligns with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12, which aims to ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns [4].

The valorization of pineapple processing waste for various applications has recently gained increasing attention [5]. The chemical composition of this waste shows that it is a source of polysaccharides, including cellulose and pectin. The technological functions of these extracted components include the enhancement of texture due to rich dietary fiber contents, which improves the structural integrity of food products. Moreover, pineapple dietary fibers are effective in reducing fat content and improving the overall consistency of beef sausages [6].

Dried pomace powder has been supplemented into flour prior to producing cookies, resulting in increased dietary fiber [7]. The extraction of pectin from fruit and vegetable by-products to replace fat in yogurt has been reported [8]. Pectin extracted from banana peels was used as a fat replacer in muffins [9]. Moreover, low-methoxyl pectin from pineapple peel was successfully used to produce a hydrogel for use as a fat replacer in beef patties [10]. This type of pectin has also been reported to improve the quality of low-fat yogurt [11].

Pectin recovery from pineapple peel is typically performed using microwave-assisted extraction, which effectively mitigates the shortcomings of conventional methods. Furthermore, the simultaneous enhancement of extraction yields and the quality improvement of the resulting pectin are facilitated [12]. Thus, the extraction of low-methoxyl pectin from pineapple waste to produce a fat replacer for sausages is possible. This approach represents a strategy for upcycling pineapple waste to produce reduced-fat sausages as a healthier meat product.

Besides pectin, cellulose has been isolated from pineapple by-products and successfully modified by attaching carboxymethyl moieties to form carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) [13]. This CMC has been used to produce edible films via combinations with gelatin. These gelatin composite films exhibited antioxidant activity and modified material properties [14]. However, the use of these films as edible casings for sausages has not been reported. Evaluating the potential of these films as casings for reduced-fat sausages represents a promising area. This would strengthen the approach for upcycling pineapple industry waste while enabling the meat and fishery industries to produce healthier products.

Therefore, this study aimed to (1) update waste generation estimates from the pineapple industry in Thailand; (2) demonstrate waste upcycling by extracting pectin to produce fat-replacing hydrogels crosslinked by natural calcium from fish bone powder; and (3) evaluate the feasibility of using an edible film made with gelatin/carboxymethyl cellulose films, synthesized from pineapple waste cellulose, as casings for reduced-fat sausages during cold storage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Data regarding pineapple production from 2015 to 2024 were obtained from the Office of Agricultural Economics, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, Thailand.

Pineapple samples were sourced from a local farmer at Ban Mor, Srichiang Mai, Nong Khai, Thailand, with geographical coordinates of “17.956839, 102.589471”. The whole fruit was separated into peel, core, and flesh after removing the crown. The peel was washed with tap water and vacuum dried at 60 °C until a constant weight was achieved. Soy protein isolates (approximately 90% purity) were provided by Shandong Yuwang Ecological Food Industry Co., Ltd. (Dezhou, China). Commercial pectin (HSA310, low-methoxyl medium-reactivity calcium pectin E440) was obtained from Dangshan Haisheng Pectin Co., Ltd., (Suzhou, China).

2.2. Estimation of Pineapple Waste

The estimation of pineapple waste generation was based on 75% of the annual production, which is supplied to processing factories, according to the Office of Agricultural Economics of Thailand report for 2015–2024. Finally, the amounts of each waste constituent were determined based on our review [15], with peel and core accounting for an average of 35.5% and 14.7% of the fruit’s weight, respectively.

2.3. Utilization of Pectin from Pineapple Waste to Produce Reduced-Fat Sausage

2.3.1. Extraction of Pectin from Pineapple Waste

Pectin was extracted using a previously developed method [16]. A 5 g sample was mixed with citric acid (adjusted to pH 1.5) at a raw-material-to-solvent ratio of 1:30. Extraction was performed via microwave treatment at 300 W for 5, 7, and 10 min, followed by cooling in a cold bath for 15 min. The extract was filtered through filter paper prior to 30 min of centrifugation at 10,000× g. The clear fraction was mixed with 500 mL of 95% ethanol and allowed to precipitate overnight in a cold room. The precipitated pectin was washed with 70% ethanol and recovered via centrifugation at 10,000× g for 5 min. The final precipitate was vacuum-dried at 60 °C for 1 h to produce the fat replacer.

2.3.2. Production of Fat Replacer with Extracted Pectin

The fat replacer preparation followed a previously published method [10]. Pectin extracted from pineapple peel was mixed with commercial pectin at a 1:3 ratio to obtain mixed pectin. This mixed pectin sample was classified as low-methoxyl pectin as the degree of methylation was lower than 50%. This mixture was then combined with soy protein isolates (1.0%) before heating at 90 °C for 30 min. Fish bone powder (0.5%) from catfish was then added to release available calcium ions in order to induce the gelation of low-methoxyl pectin, while heating continued for 5 min. After cooling, the resulting hydrogel was used as a fat replacer (FR) in sausage formulations.

2.3.3. Production of Reduced-Fat Sausage

Sausage production followed the method of Hemung et al. [17]. The recipe ratio consisted of minced fish, corn oil, salt, and ice maintained at 60%, 20%, 0.5%, and 19.5%, respectively. Fat was reduced from the original recipe by substituting FR at 25% to facilitate quality comparisons. Minced fish, salt, and a quarter of the total ice were chopped for 30 s using a handheld food mixer (Bowl Rest™ mixer, Hamilton Beach, Glen Allen, VA, USA). The remaining ice was then added, and the mixture was chopped for an additional minute. Corn oil was then incorporated, and chopping continued for one more minute to form a batter with a temperature below 16 °C. This batter was stuffed into edible casings measuring 1.30 cm in diameter and hand-tied with a cotton rope at approximately 3 cm intervals. The sausages were incubated at 40 °C for 15 min, followed by cooking at 80 °C for an additional 15 min. The cooked samples were then cooled in ice water for 15 min. After cooling in a cold room overnight, the edible casings were removed before evaluating their characteristics.

2.3.4. Characterization of Reduced-Fat Sausage

Water-Holding Capacity (WHC)

Cubic samples (1.0 g) were prepared and wrapped in filter paper (3 layers); then, they were placed in centrifuge tubes. The samples were centrifuged at 2000× g for 30 min at ambient temperature. The sample’s weight was recorded before (Wi) and after (Wf) centrifugation. WHC was calculated as the percentage of weight remaining after centrifugation using Equation (1). The mean and standard deviation were calculated according to 3 replicates:

Texture Profile Analysis

Sausage texture was analyzed following a previously published method [18]. Sausage samples were cut into 1 cm cubes and compressed twice using a cylindrical aluminum probe with a texture analyzer (TA XT Plus, Godalming, UK). Cubes were compressed to half their original height at a 5 mm/s probe speed. Average texture parameters, including hardness, springiness, adhesiveness, cohesiveness, gumminess, and chewiness, were calculated according to 5 replicates.

Chemical Composition

The chemical composition of sausages was evaluated following standard procedures with slight adjustments [19]. Moisture content was assessed by drying the samples in an oven at 105 °C for over 12 h. Crude fat was measured using Soxhlet extraction with petroleum ether as the solvent. The total ash content was determined via dry ashing in a muffle furnace at approximately 550 °C for more than 6 h. Protein levels were quantified using the Kjeldahl method, and crude dietary fibers were evaluated according to AOAC [19]. All composition values were reported as averaged standard deviations from 3 replicates. Total carbohydrate content was calculated by subtracting all other compositions from a hundred.

2.4. Application of Cellulose from Pineapple Waste to Produce Edible Film

2.4.1. Extraction of Cellulose from Pineapple Waste

Pineapple waste was soaked in water for 8 h before drying under the same conditions as those for pectin extraction. Dried samples were stored under dry conditions until used. The cellulose was extracted according to a previously published method [20]. The procedure involved heating dried pineapple waste powder with 0.5 M NaOH at a 1:60 ratio for 3 h. The slurry obtained from this treatment was then filtered, and the cellulose was washed with cold water. The obtained cellulose was vacuum-dried at 60 °C for 1 h prior to carboxymethyl cellulose synthesis.

2.4.2. Synthesis of CMC and Film Formation with Gelatin

The CMC from pineapple core was synthesized according to Seubsunthorn et al. [11], and it was used to produce composite films with gelatin. This was compared with films made from commercial cellulose according to Seubsunthorn et al. [14]. Cellulose from pineapple waste (5.0 g) was mixed with 30.0% NaOH (50 mL) and isopropyl alcohol (150 mL). The mixture was stirred at 30 °C for 30 min before adding monochloroacetic acid (6 g). Thereafter, the mixture was continually stirred for 90 min prior to incubating at 55 °C for 3 h. The incubated mixture was filtered through Whatman® No. 1 filter paper (Marlow, UK). The retentate was washed by mixing with 70.0% (v/v) ethanol (50 mL) and stirred for 5 min (adjusted pH to 7.00) before filtering through the filter paper. This washing step was repeated 4 more times. Then, the final retentate was dried overnight at 55 °C and used as CMC powder. The abbreviations CCMC and PCMC are used to denote commercial and pineapple waste CMC, respectively.

2.4.3. Storage Stability of Reduced-Fat Sausage Wrapped in Gelatin/CMC Film

The CCMC and PCMC were used to wrap the reduced-fat sausage, and they were kept at 4 °C for 5 days. Changes in quality were monitored as detailed in the following subsections.

Changes in Color Values

The color value of the sausages was measured using a Hunter colorimeter (Color reader, CR-10, Minolta, Osaka, Japan). The results were reported using Hunter L, a, and b scales, representing lightness, redness, and yellowness, respectively. Average values and standard errors were obtained from 5 measurements.

Changes in pH

The sausage’s pH was measured using a pH meter (PH850-BS Portable, Shanghai, China) following Janardhanan et al. [21] at room temperature. The pH meter was calibrated with standard buffer solutions at pH 4, 7, and 10 before measurement. A solid probe was inserted directly into the samples for each measurement. The reported pH values represent the average of 5 measurements.

Changes in Microbial Indices

The total viable count (TVC) is a measurement that estimates the total amount of living microorganisms in a sample. The TVC was determined using the spread plate method with a focus on aerobic bacteria, which normally deteriorate a sausage’s quality. In summary, a 25 g sausage sample was aseptically homogenized with 225 mL of normal saline (0.9% NaCl) in a stomacher (Model 400 Seward, London, UK) for 2 min. Then, a serial dilution was prepared using a normal saline solution. Then, a 0.1 mL sample mixture was spread on the plate count agar (PCA) prior to incubation at 37 °C for 24 h. The results were reported as log CFU/g from 3 replications. The number of Staphylococcus aureus was quantified according to the analysis method in the Bacteriological Analytical Manual Online (BAM). The quantification of Clostridium perfringens was carried out according to the analysis method in the Bacteriological Analytical Manual Online (BAM). The quantity of Salmonella spp. was determined according to the ISO 6579-1: 2017 standard reference method [22]. In addition, Escherichia coli was quantified according to the analysis method from the Food and Drug Administration [23].

Changes in TBARS

Lipid oxidation in sausages was assessed using the TBARS method [24]. Patty samples (2.00 g) were combined with 3 mL of the TBA solution; then, 17 mL of the TCA mixture was added. The mixture was boiled for 30 min and cooled to room temperature, and 5 mL of the clear upper layer was transferred to a 50 mL centrifuge tube containing 5 mL of chloroform. After centrifugation at 200× g for 5 min, 3 mL of the upper liquid was decanted, mixed with 3 mL of petroleum ether, vortexed, and centrifuged again at 200× g for 10 min. The absorbance of the lower layer was measured at 532 nm using a UV/VIS spectrometer (PG Instruments Model T70 Plus, PG Instruments Limited, Louth, UK). The TBARS results were expressed as mg malondialdehyde (MDA)/kg sample, averaged from 3 replications.

DPPH Radical Scavenging Ability

Antioxidant activities were determined using the DPPH assay. Antioxidants were extracted from the samples by immersing them in 3 mL of methanol for 48 h. Subsequently, 0.5 mL of the extract was mixed with 1.5 mL of ethyl acetate, followed by the addition of 1.5 mL of a DPPH solution. The mixture was then incubated in the dark for 30 min, and absorbance was measured at 515 nm (A sample) using a spectrophotometer (PG Instruments Model T70 Plus, PG Instruments Limited, Louth, UK). A control was prepared under the same conditions without the sample extract. The DPPH radical scavenging activity was calculated according to Equation (2). The average values were calculated from 3 replicates:

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The data were presented as mean ± SD. IBM SPSS statistical software (Version 28.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data analysis. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and F-tests were employed to determine statistical differences at a confidence level of 95%.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Upcycling Pineapple Waste Toward a Circular Model

3.1.1. Pineapple Production and Waste Generation in Thailand

Pineapple production in Thailand was reduced to approximately 41% from 2015 to 2024 (Table 1). This is likely due to the fluctuation of prices, which may not be convincing enough to encourage farmers to provide a consistent supply. In addition, climate change plays a crucial role in governing the productivity of pineapple [25]. Moreover, the cost of production, which affects the demand/supply in global markets, is an important factor for determining the production scale of pineapple in each area [26]. In Thailand, pineapple production supplied to processing plants for canned pineapple production totaled approximately 0.41 million tons in 2023 [2]. In addition, this processing line generated approximately 474298.04 tons of peels and 196399.47 tons of core, respectively. Therefore, the total waste from canned pineapple processing was estimated at 670,698 tons between 2015 and 2024. These amounts were estimated based on average values from data from the past 10 years. The utilization of pineapple waste for high-value products should therefore be focused on. This type of waste is typically disposed of from processing plants or sold at a low price for producing feed and fertilizers. This traditional strategy cannot be considered as an upcycling method since low-value products are produced. The price of this waste type was reported in the range of 0.40–2.25 THB/kg and also depended on characteristics and moisture content [27]. Moreover, the demand for this continuous process may not be balanced with the generation capacity; some of this waste is still discarded as organic waste, which results in environmental pollution. This includes water pollution from leachate draining from waste piles, air pollution from decomposition odors, and pest infestations as these piles become breeding grounds for disease-carrying vectors. Therefore, in this part of the study, data on pineapple production over the past ten years were collected, and the amount of pineapple waste was calculated to indicate its potential for producing high-value products according to circular economy principles.

Table 1.

Total production of pineapple, the designated amount for canned processing, and the related waste generated.

3.1.2. Circular Model for Valorizing Pineapple Waste

The circular economy model plays a vital role in addressing food waste challenges within the pineapple industry. It emphasizes reducing, reusing, and recycling pineapple by-products generated during production processes. The distinctive feature of this model is the extension of food resource utilization, encouraging industries to adopt efficient resource management practices [28]. By implementing this, environmental impacts from pineapple production and consumption can be mitigated at all stages. Key strategies include curbing overproduction, converting waste into new products, and improving supply chain management to enhance sustainability within the pineapple production system. Integrating these principles promotes resource-efficient and sustainable pineapple industry development, maximizing the value of pineapple resources [29].

Food upcycling in the industry involves transforming food scraps, by-products, and production waste into higher-value products with greater economic worth than the original materials [30]. This process represents a core element of the circular economy strategy, closing resource loops by harnessing valuable biomolecules in waste streams—including proteins, fibers, oils, and phenolic compounds—that possess significant nutritional and industrial value. Rather than disposing these materials in landfills or treating them as low-value waste, upcycling enhances them to create premium products, thereby reducing environmental impact and maximizing resource efficiency [31].

Pineapple processing waste can be upcycled as a source of valuable polysaccharides, particularly pectin and cellulose. Cellulose extracted from waste undergoes carboxylation modification to produce CMC, which can be composited with gelling agents and cast into edible films suitable for use as sausage casings for meat and fish processing industries. Additionally, pectin from pineapple waste can be processed into hydrogels through natural calcium induction in the presence of soy protein isolates. These hydrogels serve as fat replacers in meat and fish sausages, reducing fat content while maintaining texture and palatability.

3.2. Application of Pectin from Pineapple Waste to Produce Reduced-Fat Sausage

In order to obtain information for the upcycling utilization of pineapple waste, pineapples were processed via the same methods as those used in the production of canned pineapple, and leftover waste was used as the sample for valorization. This comprises a model representation of the processes used at industrial scales. It can be observed that pineapple waste exhibited a good source of fiber in either the core or peel (Table 2). This suggests that pineapple waste is a potential resource for producing either pectin or cellulose, which are non-digestible polysaccharides. Therefore, the recovery of these compounds to produce higher-value products is a strategy that is aligned with the SDG model.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of pineapple waste.

3.2.1. Chemical Composition of Each Pineapple Waste Component

The chemical composition of the waste varies by part. However, both the peel and core are good fiber sources, as carbohydrate and fiber contents are consistently high across both waste components (Table 2).

3.2.2. Extraction of Pectin from Pineapple Waste to Produce a Fat Replacer

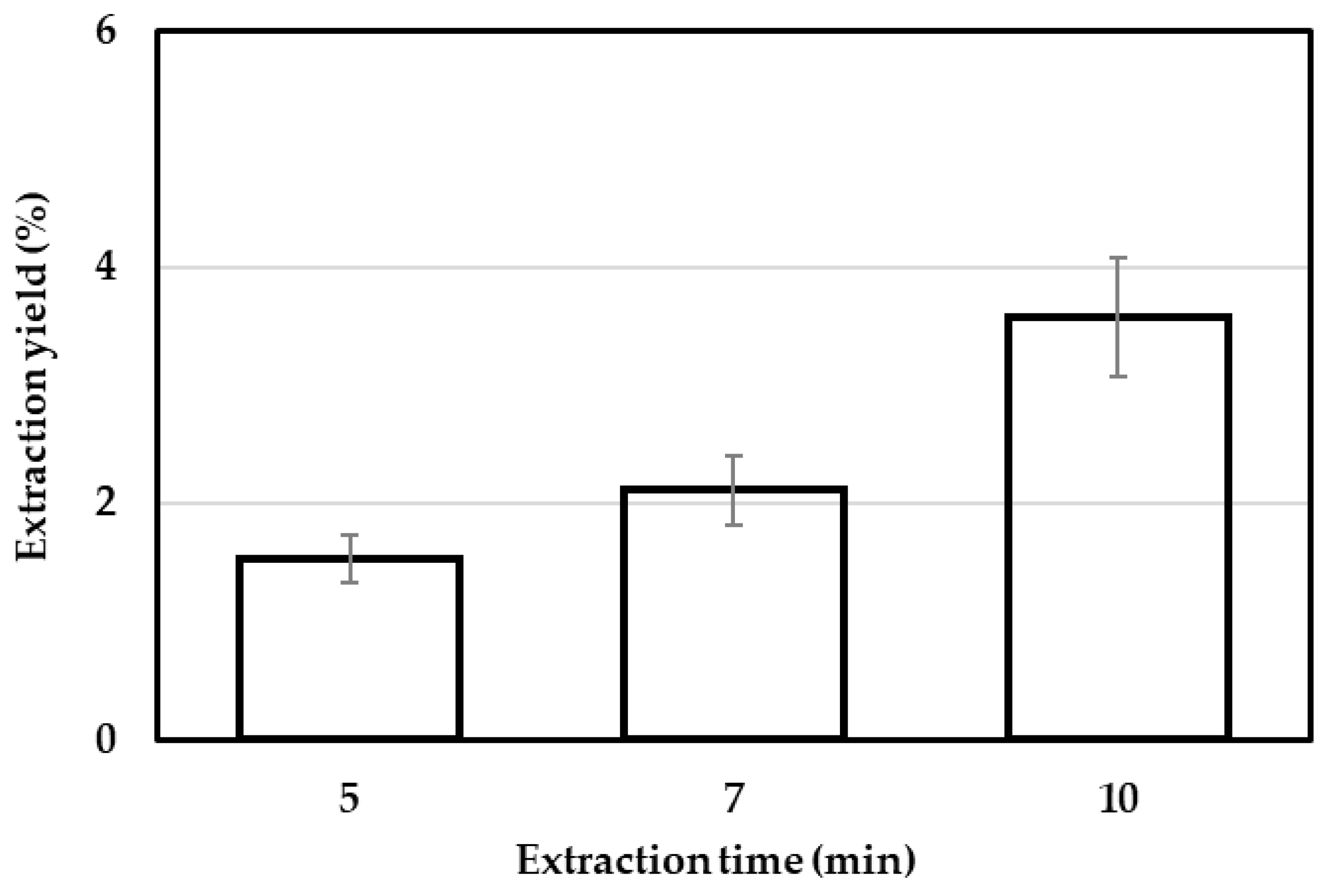

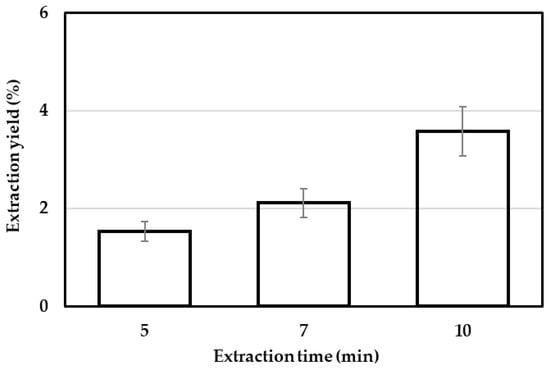

Extraction times used during microwave digestion at 300 W were tested to evaluate extraction efficiency. In this study, the 10 min extraction time window produced the highest yield (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of extraction time on pectin yield during microwave extraction at 300 W.

Pectin is a polysaccharide found abundantly in the cell walls of higher plants, particularly in the middle lamella, and it is present in vegetables and fruits. Industrial pectin extraction commonly employs hot acids—such as hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, or nitric acid—at a pH range of 1.3–3 and temperatures of 60–100 °C for 20–360 min. However, prolonged exposure to high temperatures may result in pectin degradation. The physicochemical and functional properties of pectin extracted from dragon fruit peel were altered due to heat digestion. Therefore, researchers have explored alternative extraction techniques. Microwave digestion with hot acid increased pectin yields from dragon fruit peel [32]. Additionally, the type of acid used affects pectin yields when microwave-assisted extraction is applied to extract pectin from passion fruit [33]. Chelating agents or acids with chelating properties, such as citric acid, can be used to enhance extracted pectin [16]. Pectin extraction from pineapple using citric acid combined with microwave treatment at 300 W for 5, 7, and 10 min at pH 1.5 showed that the 10 min extraction yielded the highest pectin content of 3.58%. This value exceeded that obtained by Rodsamran et al. [34], who used 420 W for longer durations (30 and 60 min), suggesting that higher power levels do not improve recovery yields. Pectin extraction via microwave digestion using citric acid at 300 W for 10 min was selected as the optimal method.

The characteristics of pectin extracted from pineapple waste have been previously determined, exhibiting antioxidative properties or antimicrobial activities superior to those of commercial pectin. Therefore, combining pectin from these two sources is a promising approach for producing low-methoxyl pectin, with obtained proportions at approximately 30–35%. The pectin mixture must form a gel upon dosing with residual calcium, which is derived from fish bone powder. It has been demonstrated that mixing pineapple waste pectin with commercial pectin at a 1:3 ratio could result in a hydrogel upon induction via natural calcium released from fish bone powder (1%). In addition, the inclusion of soy protein isolates enhances the mouth feel, mimicking the texture of fat tissue. This hydrogel was therefore used successfully as a fat replacer in patties, where 25% substitution did not affect the overall quality [10]. Thus, the feasibility of reducing fat content in sausages by substituting the hydrogel as a fat replacer is further investigated in this study.

3.2.3. Characteristics of Sausages with/Without the Substitution of Fat with FR

The chemical compositions revealed that the substitution of fat with FR at 25% resulted in fat reduction, but this also resulted in a higher moisture content. However, other components were not affected (Table 3). Hydrogel-substituted sausages demonstrated proportionally reduced crude fat content corresponding to the 25% substitution level. The enhanced moisture content was attributed to the water retention capacity of the hydrogel matrix. This resultant fat reduction improved the nutritional profile by decreasing lipid-derived energy densities, which is consistent with previous findings [10].

Table 3.

Chemical compositions of sausages with/without the substitution of fat with FR at 25%.

The physicochemical properties of these sausages were evaluated to elucidate the effect of fat substitution with hydrogel. Color improvements were evidenced by increased yellowness, likely due to residual carotenoids in the pectin (Table 4). Pineapple peels have been reported as a potential source of phenols and organic acids [35]. pH changes were observed in the reduced-fat sausage, and they are a result of the residual citric acid in the extracted pectin. Fat replacer substitutions affected physical and technological properties, reducing pH while increasing water-holding capacities. Yellowness increased in sausages containing FR.

Table 4.

Physicochemical properties of sausage with/without the substitution of fat with FR at 25%.

Textural properties improved significantly, especially in terms of hardness, gumminess, and chewiness. However, springiness, adhesiveness, and cohesiveness were not significantly affected (Table 5). The incorporation of hydrogels not only reduced fat and energy but also improved textural properties. Similar phenomena were found in yogurt and muffins when fat replacers made from recovered pectin were applied [9,11].

Table 5.

Textural properties of sausages with/without the substitution of fat with FR at 25%.

3.3. Changes in Qualities of Sausage Wrapped in Films Made from Different CMC Types

Color stability during storage was observed in reduced-fat sausages wrapped with both films (Table 6). Their pH values exhibited the same stability pattern. However, reduced radical scavenging abilities accompanied by increased TBARS were observed in samples wrapped with gelatin films supplemented with CMC synthesized from commercial cellulose.

Table 6.

Physicochemical properties of reduced-fat sausages after storage at 4 °C for 5 days.

The utilization of pineapple waste to produce edible films by extracting cellulose has been reported, which is then derivatized to CMC [13]. The CMC could be composited with gelatin to produce edible films, and their properties suggest suitability for use as sausage casings [14]. Therefore, the feasibility of using this film as a casing was evaluated, and a model was created in the laboratory by wrapping the reduced-fat sausages with gelatin films composed of CMC from different sources.

After storage in a refrigerator for 5 days, the DPPH value of the reduced-fat sausage wrapped with gelatin film supplemented with CMC from pineapple waste was higher than that wrapped with commercial CMC. This may be because the gelatin film supplemented with CMC from pineapple waste carried antioxidants, particularly phenolic compounds. Therefore, the gelatin film supplemented with CMC from pineapple waste effectively reduced oxidative rancidity, as evidenced by the lower TBARS throughout the storage period.

The lightness (L*) values of the fish sausages decreased with an increase in storage time. This could be attributed to the higher water vapor permeability (WVP) of gelatin films supplemented with CMC from pineapple waste [14]. This allowed more water vapor to escape from the sample, resulting in reduced lightness. Therefore, increased yellowness was subsequently observed.

Microbial growth in sausages was observed after 5 days of refrigerated storage, although none were detected immediately after processing (Table 7). However, foodborne bacteria such as Clostridium perfringens, Staphylococcus aureus, and Salmonella spp. were not detected.

Table 7.

Changes in the microbial indices of reduced-fat sausages stored at 4 °C for 5 days.

Changes in biological qualities revealed that samples wrapped with both films exhibited no Clostridium perfringens, Salmonella spp., and Staphylococcus aureus populations (Table 7). However, Escherichia coli was detected at levels below 3.0 log CFU/g, which complies with the Thai Industry Standard [36]. After storage at 4 °C for 5 days, the total microbial counts of fish sausages wrapped with gelatin films supplemented with CMC from pineapple waste exceeded industry standards (5.0 log CFU/g). However, counts for sausages wrapped with films supplemented with commercial CMC met the standard. The application of an essential oil from apricot (Prunus armeniaca) kernels in chitosan films resulted in improved barrier (WVP reduction), antibacterial and antioxidative properties [37]. Gelatin films with CMC from pineapple waste exhibited higher WVP and solubility compared to those with commercial CMC [14]. Therefore, further modifications of this film were investigated to reduce solubility and WVP in order to inhibit microbial growth. Although CMC from pineapple waste could not effectively retard microbial growth, its inhibition of oxidative rancidity was pronounced. This was evidenced by reduced TBARS levels, a secondary oxidation product, and a higher retained DPPH radical scavenging ability (Table 7). Flavonoids are an important phenolic component in pineapple waste, and they can be extracted using ethanol via microwave heating, with yields of approximately 365 mg/g [38]. The presence of phenolic compounds in the CMC/gelatin film likely explains the high remaining DPPH radical scavenging activity observed in the sausage. Based on this study, pineapple waste could be valorized for producing active films for reduced-fat sausage casings. This would constitute an alternative approach for upcycling agricultural waste through innovative and healthier meat and fishery products.

4. Conclusions

Thailand, a key global canned pineapple exporter, generates significant annual processing waste (peels and cores), averaging approximately 600,000 metric tons (MT) over the past decade. Analyzing these constituents is essential for successful resource recovery and the promotion of sustainability. Pineapple waste could be a source of pectin, and quick extractions could be performed using the microwave-assisted method. The resultant pectin can be used to produce hydrogels as fat replacers in meat products. The application of this fat replacer in sausages not only reduces fat content without compromising desirable properties but also improves technological and textural properties. In addition, cellulose could also be extracted from pineapple waste, and its derivative, carboxymethyl cellulose, serves as an alternative material to composite with gelatin for forming edible films with superior antioxidative properties compared to those made from commercial cellulose. This film demonstrated suitability as an edible casing for reduced-fat sausages. Therefore, the upcycling approach results in maximized efficiency in these sectors and promotes the meat and fishery industries through the development of healthier food products.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.-O.H.; Methodology, N.U. and N.J.; Formal analysis, N.U., N.J. and B.-O.H.; Investigation, N.U. and N.J.; Resources, B.-O.H.; Data curation, N.J., N.C. and B.-O.H.; Writing—original draft, N.U., N.J., N.C. and B.-O.H.; Writing—review & editing, B.-O.H.; Funding acquisition, N.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Fund of Khon Kaen University and the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) grant number 200555. The APC was funded by Khon Kaen University.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available via the following URL: “https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1ysIIKGlODbOpMXC5mTgRqb4g0rcOIoCs?usp=sharing”. Data in the article can be accessed on 9 September 2025.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Faculty of Interdisciplinary Studies, Khon Kaen University, for providing all facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCMC | Commercial carboxymethyl cellulose |

| CFU | Colony-forming unit |

| CMC | Carboxymethyl cellulose |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| PCMC | Pineapple carboxymethyl cellulose |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric acid reactive substance |

| TVC | Total viable count |

| WHC | Water holding capacity |

| WVP | Water vapor permeability |

References

- Department of Internal Trade. Pineapple, June 2024, Week 4. Available online: https://regional.moc.go.th/th/content/category/detail/id/3539/iid/55098 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Office of Agricultural Economics. Monthly Agricultural Statistics: January 2024. Available online: https://www.oie.go.th/assets/portals/1/files/monthly_report/en_briefJanuary2024.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Awasthi, M.K.; Azelee, N.I.W.; Ramli, A.N.M.; Rashid, S.A.; Manas, N.H.A.; Dailin, D.J.; Illias, R.M.; Rajagopal, R.; Chang, S.W.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Microbial biotechnology approaches for conversion of pineapple waste in to emerging source of healthy food for sustainable environment. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 373, 109714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal12 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Banerjee, S.; Ranganathan, V.; Patti, A.; Arora, A. Valorisation of pineapple wastes for food and therapeutic applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 82, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, S.S.C.; Tshalibe, P.; Hoffman, L.C. Physico-chemical properties of reduced-fat beef species sausage with pork back fat replaced by pineapple dietary fibres and water. LWT 2016, 74, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, M.; Himashree, P.; Sengar, A.S.; Sunil, C.K. Valorization of food industry by-product (Pineapple Pomace): A study to evaluate its effect on physicochemical and textural properties of developed cookies. Meas. Food 2022, 6, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adimas, M.A.; Abera, B.D. Valorization of fruit and vegetable by-products for extraction of pectin and its hydrocolloidal role in low-fat yoghurt processing. LWT 2023, 189, 115534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.; Ashraf, H.; Haq, I.U.; Liaquat, A.; Nayik, G.A.; Ramniwas, S.; Alfarraj, S.; Ansari, M.J.; Gere, A. Exploring pectin from ripe and unripe Banana Peel: A novel functional fat replacer in muffins. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thammawong, W.; Chanshotikul, N.; Sriuttha, M.; Kwantrairat, S.; Hemung, B.O. Utilization of a hydrogel made from mixed pectin/fish bone powder as a fat replacer in beef patty. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubber, S.; Chaturvedi, K.; Thakur, N.; Sharma, N.; Yadav, S.K. Low-methoxyl pectin stabilizes low-fat set yoghurt and improves their physicochemical properties, rheology, microstructure and sensory liking. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 111, 106240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar Zakaria, N.; Rahman, R.A.; Zaidel, D.N.A.; Dailin, D.J.; Jusoh, M. Microwave-assisted extraction of pectin from pineapple peel. Malays. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2021, 17, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suebsuntorn, J.; Jirukkakul, N. Synthesis and characterization of carboxymethyl cellulose from pineapple core. Food Agric. Sci. Technol. 2023, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Suebsuntorn, J.; Hemung, B.O.; Jirukkakul, N. Characterization of gelatin film supplemented with carboxymethyl cellulose from pineapple core. Asia-Pac. J. Sci. Technol. 2025, 30, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemung, B.O.; Sompholkrang, M.; Wongchai, A.; Chanshotikul, N.; Ueasin, N. A study of the potential of by-products from pineapple processing in Thailand. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 12605–12615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengkhamparn, N.; Lasunon, P.; Tettawong, P. Effect of ultrasound assisted extraction and acid type extractor on pectin from industrial tomato waste. Chiang Mai Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 2019, 18, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemung, B.O.; Yongsawatdigul, J.; Chin, K.B.; Limphirat, W.; Siritapetawee, J. Silver carp bone powder as natural calcium for fish sausage. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2018, 27, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemung, B.O.; Sriuttha, M. Effects of tilapia bone calcium on qualities of tilapia sausage. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2014, 48, 790–798. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 21st ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Xie, W.; Deng, H. Extraction, isolation and characterization of nanocrystalline cellulose from industrial kelp (Laminaria japonica) waste. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 173, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janardhanan, R.; Virseda, P.; Huerta-Leidenz, N.; Beriain, M.J. Effect of high–hydrostatic pressure processing and sous-vide cooking on physicochemical traits of Biceps femoris veal patties. Meat Sci. 2022, 188, 108772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6579-1:2017; Microbiology of the Food Chain-Horizontal Method for the Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella, Part 1: Detection of Salmonella spp. The International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Food and Drug Administration. Bacteriological Analytical Manual (BAM). Chapter 12: Staphylococcus aureus; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/foodscienceresearch/laboratorymethods/ucm071429.htm (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Deng, P.; Teng, S.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liao, B.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Y. Effects of basic amino acids on heterocyclic amines and quality characteristics of fried beef patties at low NaCl level. Meat Sci. 2024, 215, 109541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, P.A.; Crespo, O.; Essegbey, G.O. Economic implications of a changing climate on smallholder pineapple production in ghana. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 8, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Oniah, M.O.; Edem, T.O. Factors affecting pineapple production in central agricultural zone of cross river state, nigeria. Am. J. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2022, 7, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritthisorn, S.; Jutakanok, R.; Theegha, J. Production of pineapple peel handicraft paper from canned fruit industrial factory. Sci. Technol. RMUTT J. 2016, 6, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchherr, J.; Yang, N.N.; Schulze-Spüntrup, F.; Heerink, M.J.; Hartley, K. Conceptualizing the circular economy (revisited): An analysis of 221 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 194, 107001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouro-Salim, O.; Guarnieri, P.; Fanho, A.D. Unlocking value: Circular economy in NGOs’ food waste reduction efforts in Brazil and Togo. Discov. Environ. 2024, 2, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongsiriyakul, K.; Wongsurakul, P.; Kiatkittipong, W.; Premashthira, A.; Kuldilok, K.; Najdanovic-Visak, V.; Adhikari, S.; Cognet, P.; Kida, T.; Assabumrungrat, S. Upcycling coffee waste: Key industrial activities for advancing circular economy and overcoming commercialization challenges. Processes 2024, 12, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutrizio, M.; Dukić, J.; Sabljak, I.; Samardžija, A.; Biondić Fučkar, V.; Djekić, I.; Režek Jambrak, A. Upcycling of food by-products and waste: Nonthermal green extractions and life cycle assessment approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongkham, N.; Juntasalay, B.; Lasunon, P.; Sengkhamparn, N. Dragon fruit peel pectin: Microwave-assisted extraction and fuzzy assessment method. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2016, 51, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, F.L.; Fukuda, D.L.; Turbiani, F.R.B.; Garcia, P.S.; Petkowicz, C.L.O.; Jagadevan, S.; Gimenes, M.L. Extraction of pectin from passion fruit peel (Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa) by microwave-induced heating. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 38, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodsamran, P.; Sothornvit, R. Preparation and characterization of pectin fraction from pineapple peel as a natural plasticizer and material for biopolymer film. Food Bioprod. Process. 2019, 118, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, D.R.; Rotta, E.M.; Sargi, S.C.; Schmidt, E.M.; Bonafe, E.G.; Eberlin, M.N.; Visentainer, J.V. Antioxidant activity, phenolics and UPLC-ESI (-)-MS of extracts from different tropical fruits parts and processed peels. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vienna sausage TIS No. 2300-2549; Bureau of Thai Industrial Standard. Thai Industrial Standard: Bangkok, Thailand, 2006.

- Priyadarshi, R.; Sauraj; Kumar, B.; Deeba, F.; Kulshreshtha, A.; Negi, Y.S. Chitosan films incorporated with apricot (Prunus armeniaca) kernel essential oil as active food packaging material. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 85, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansod, S.P.; Parikh, J.K.; Sarangi, P.K. Pineapple peel waste valorization for extraction of bio-active compounds and protein: Microwave assisted method and Box Behnken design optimization. Environ. Res. 2023, 221, 115237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.