Effects of Plasma Parameters on Ammonia Cracking Efficiency Using Non-Thermal Arc Plasma

Abstract

1. Introduction

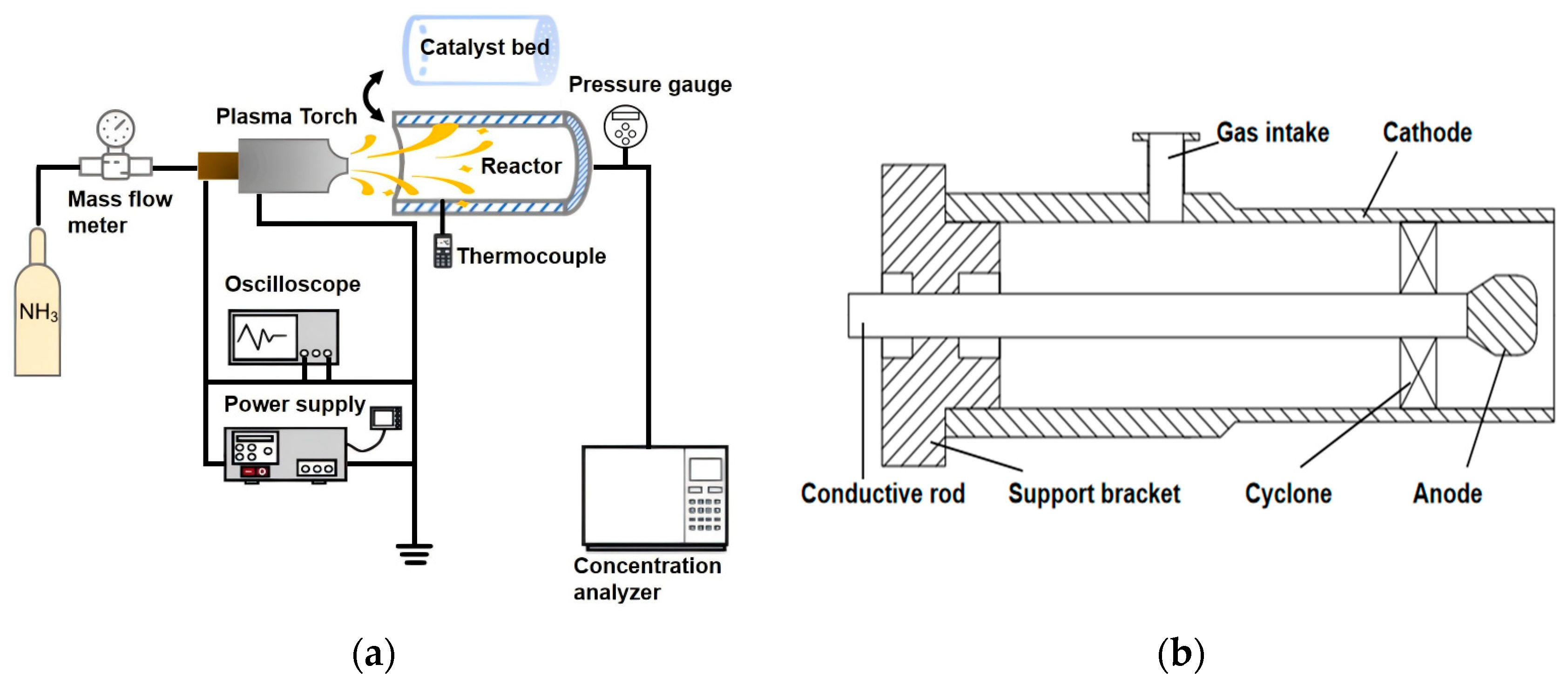

2. Experimental Setup

3. Results

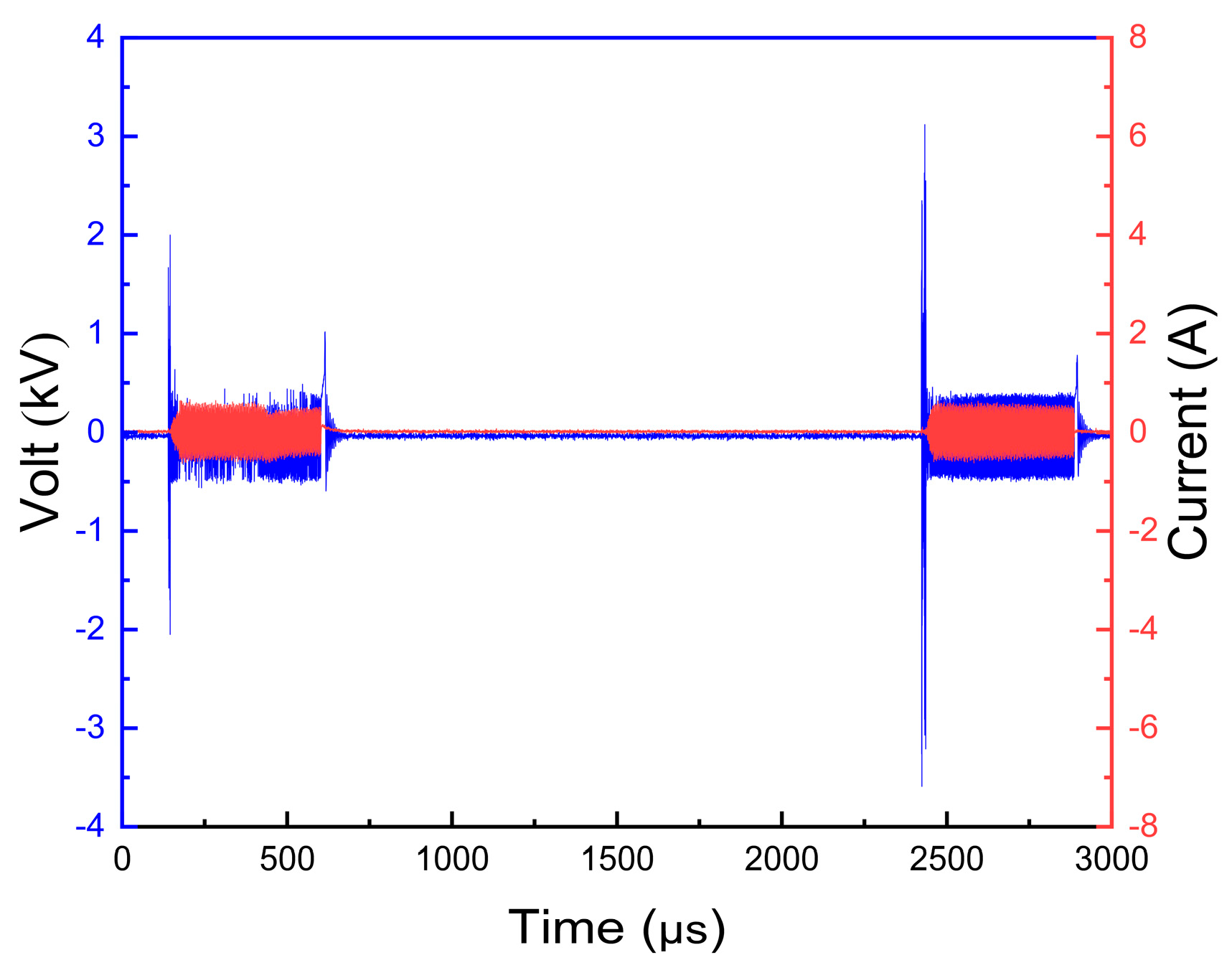

3.1. Analysis of Plasma Discharge

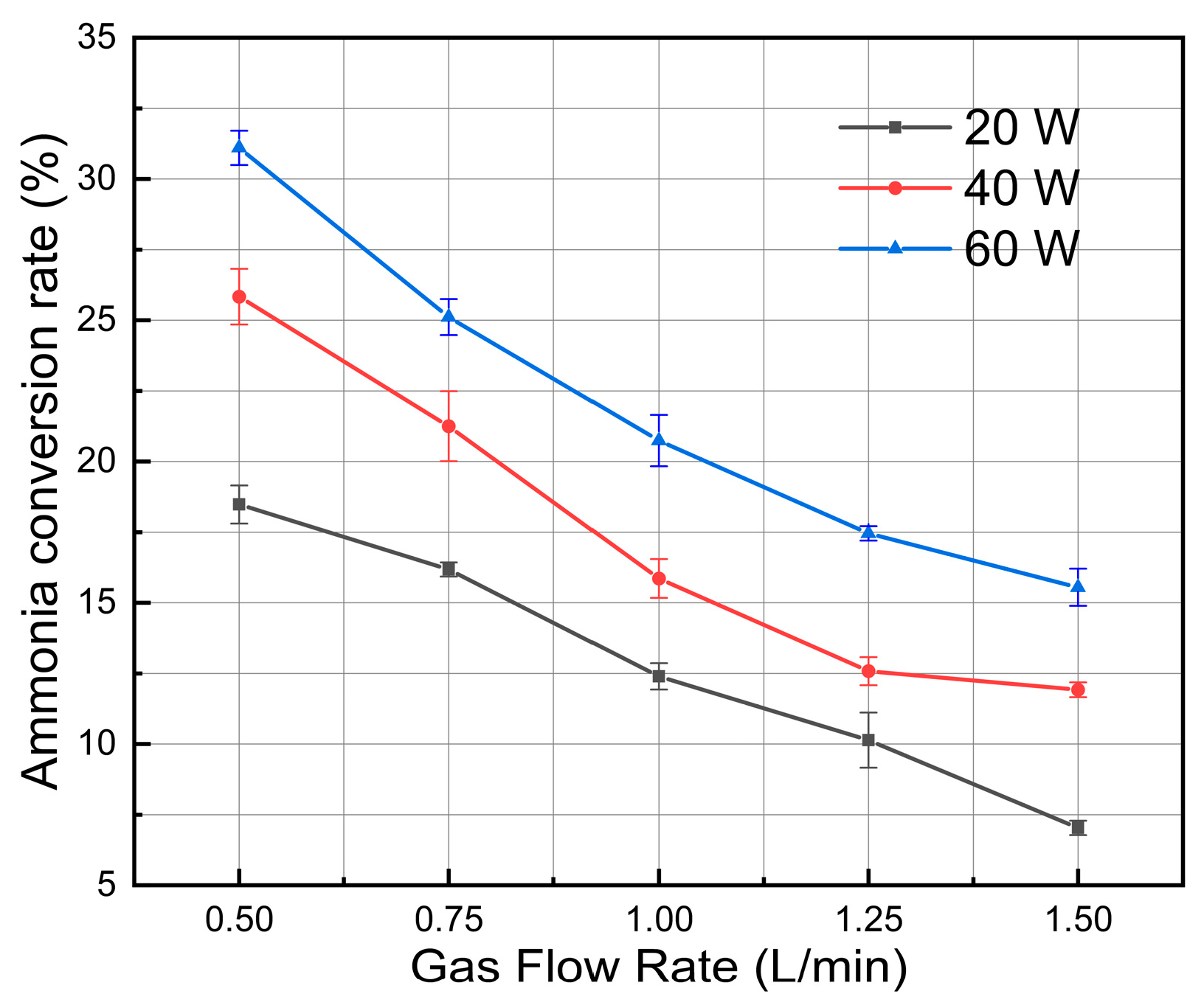

3.2. Effect of Ammonia Feed Rate

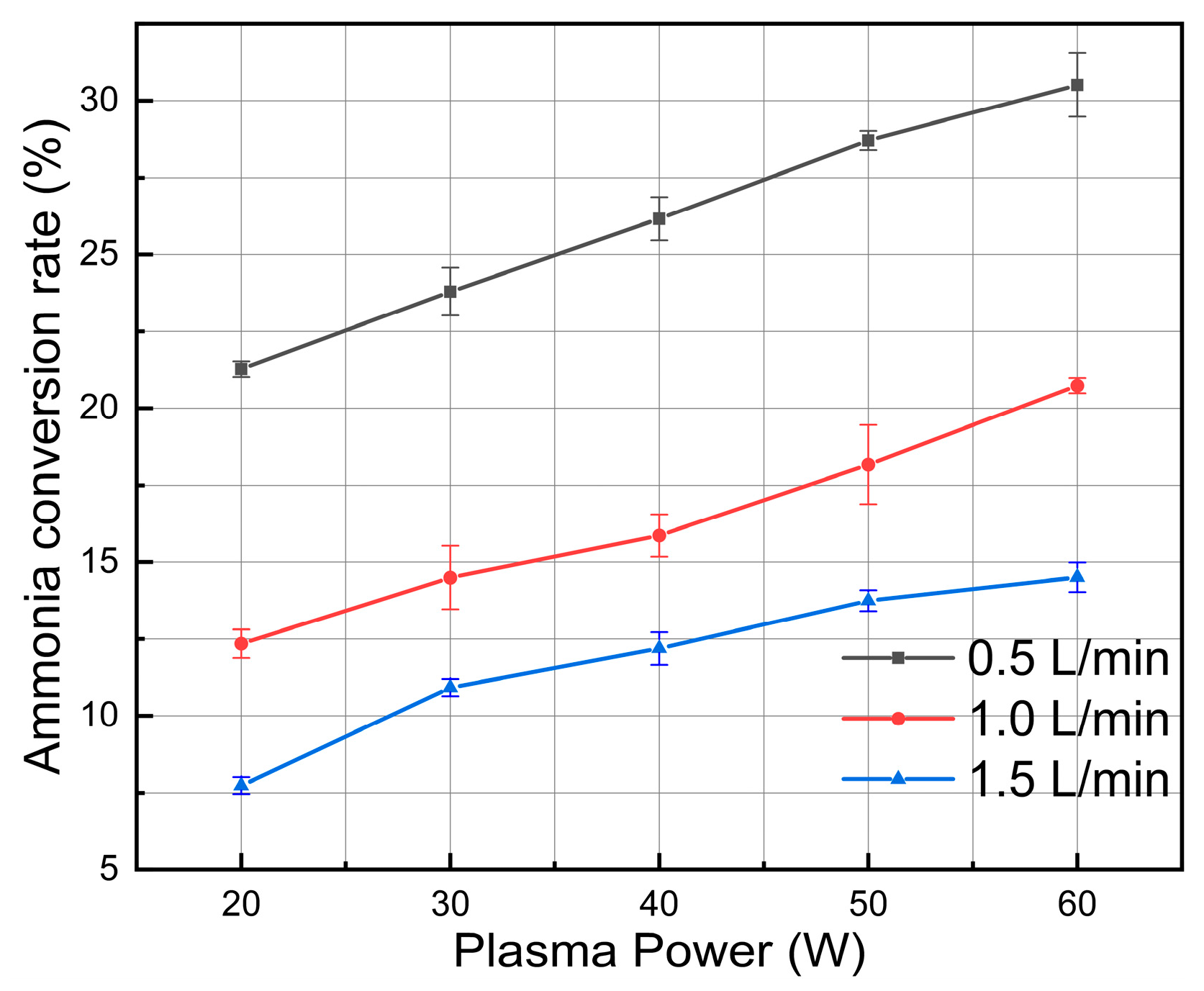

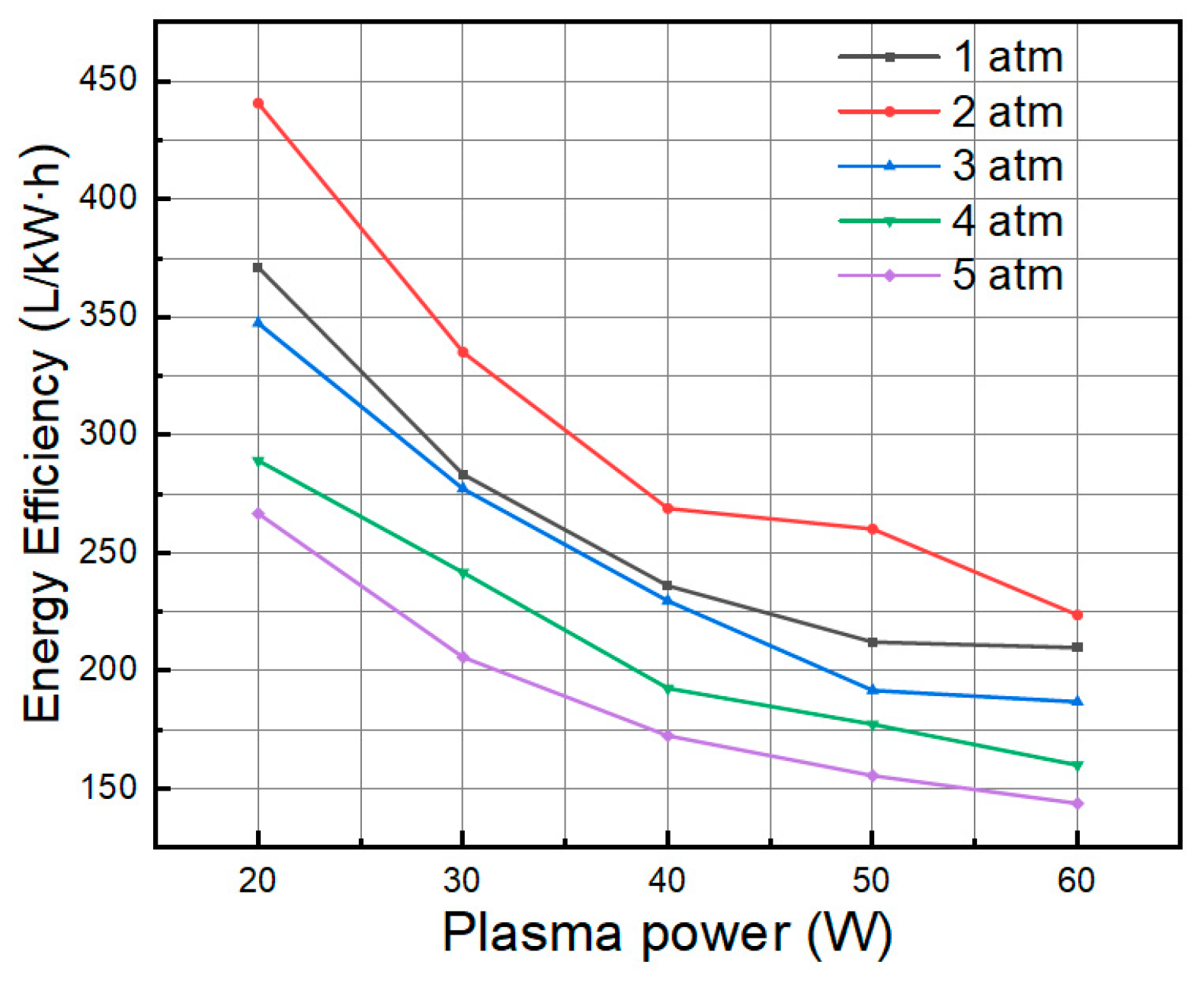

3.3. Effect of Discharge Power

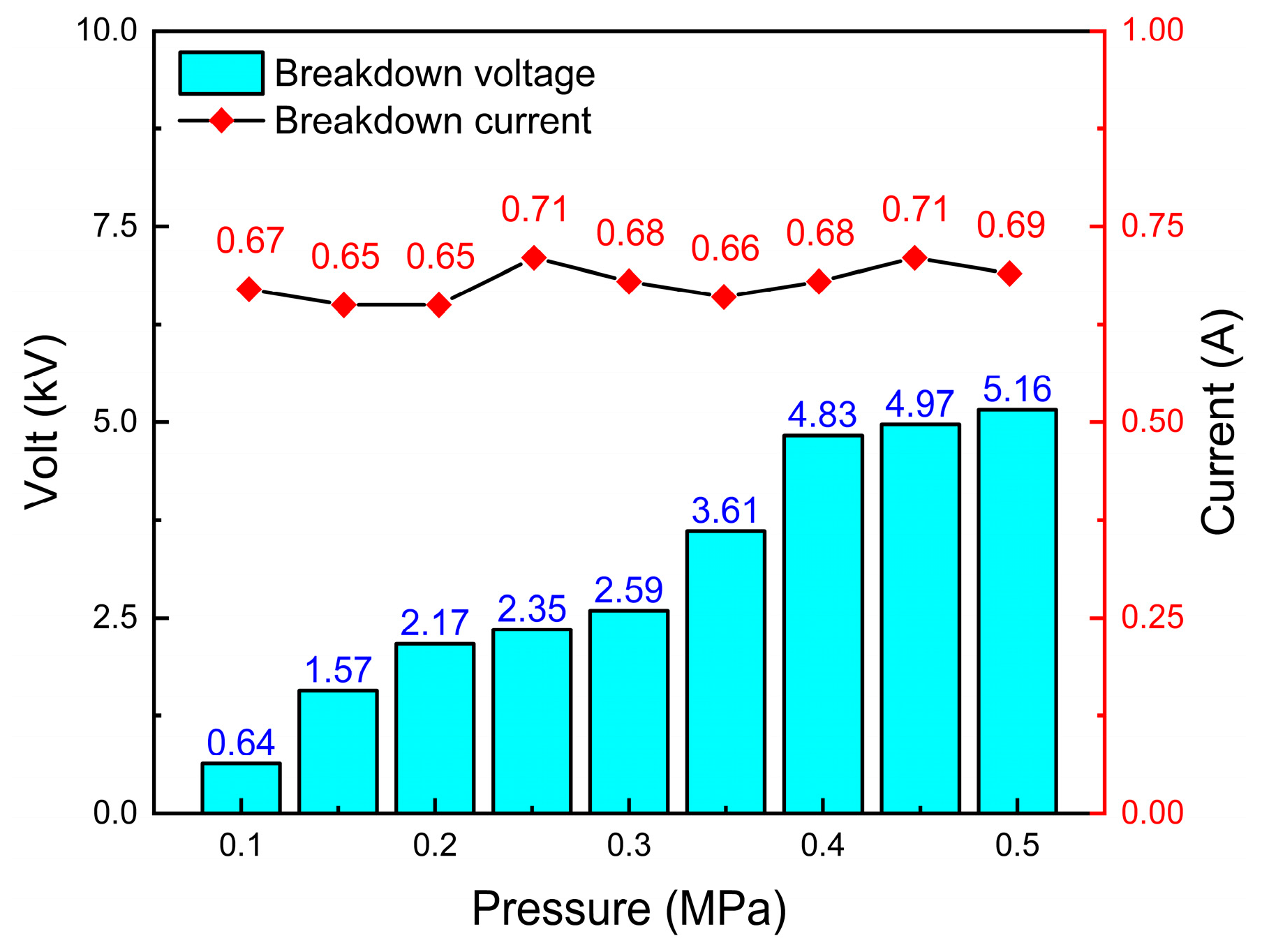

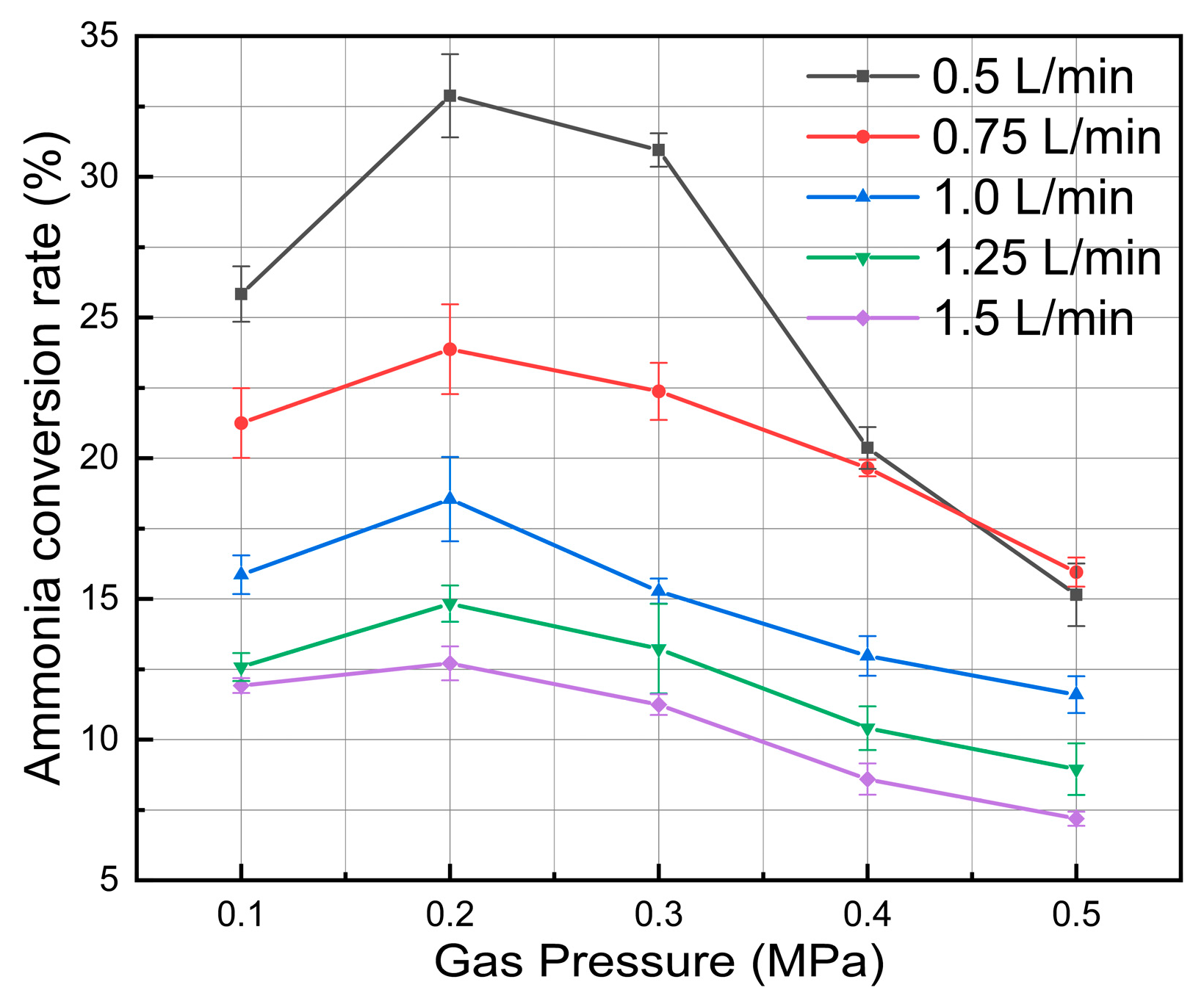

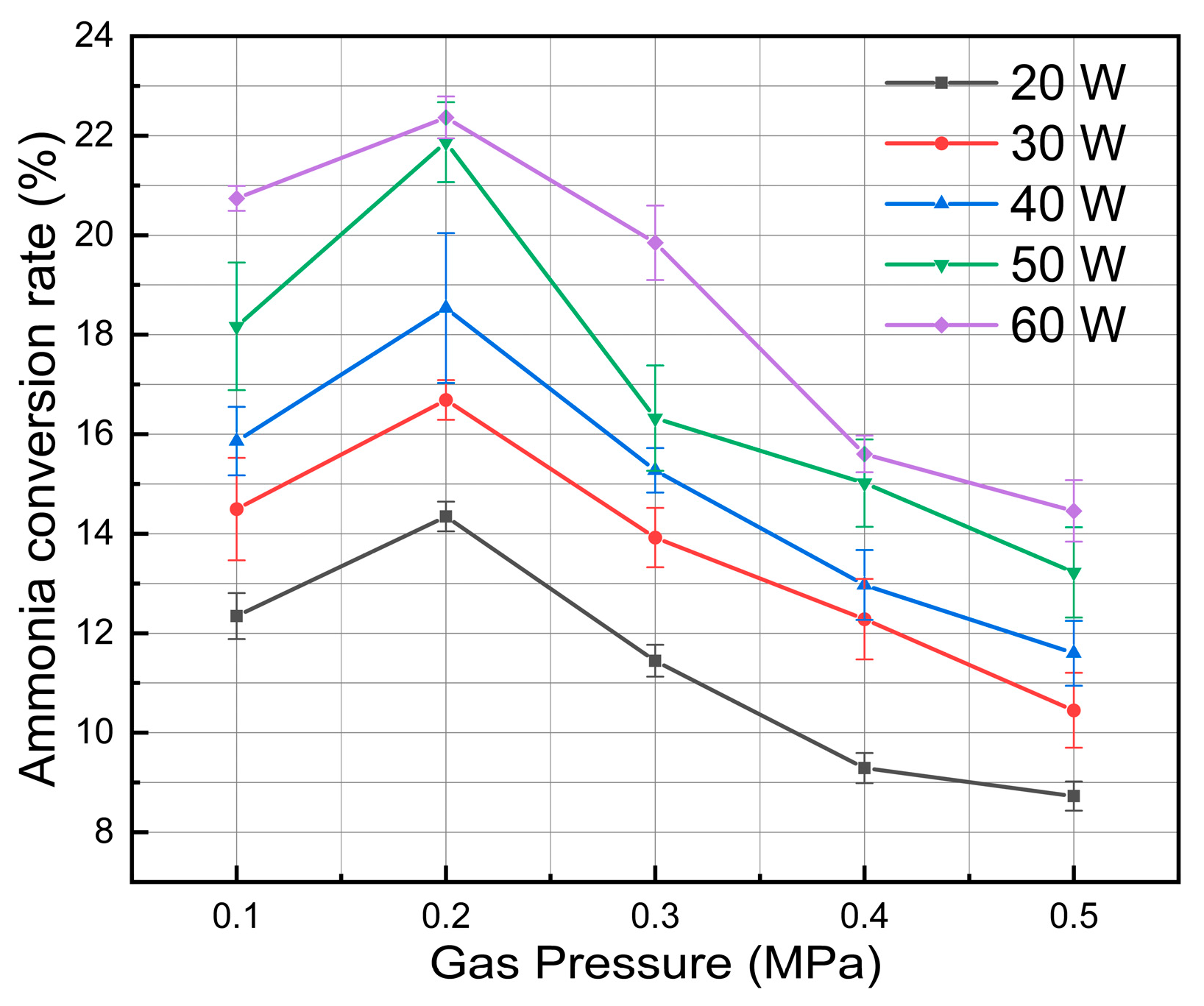

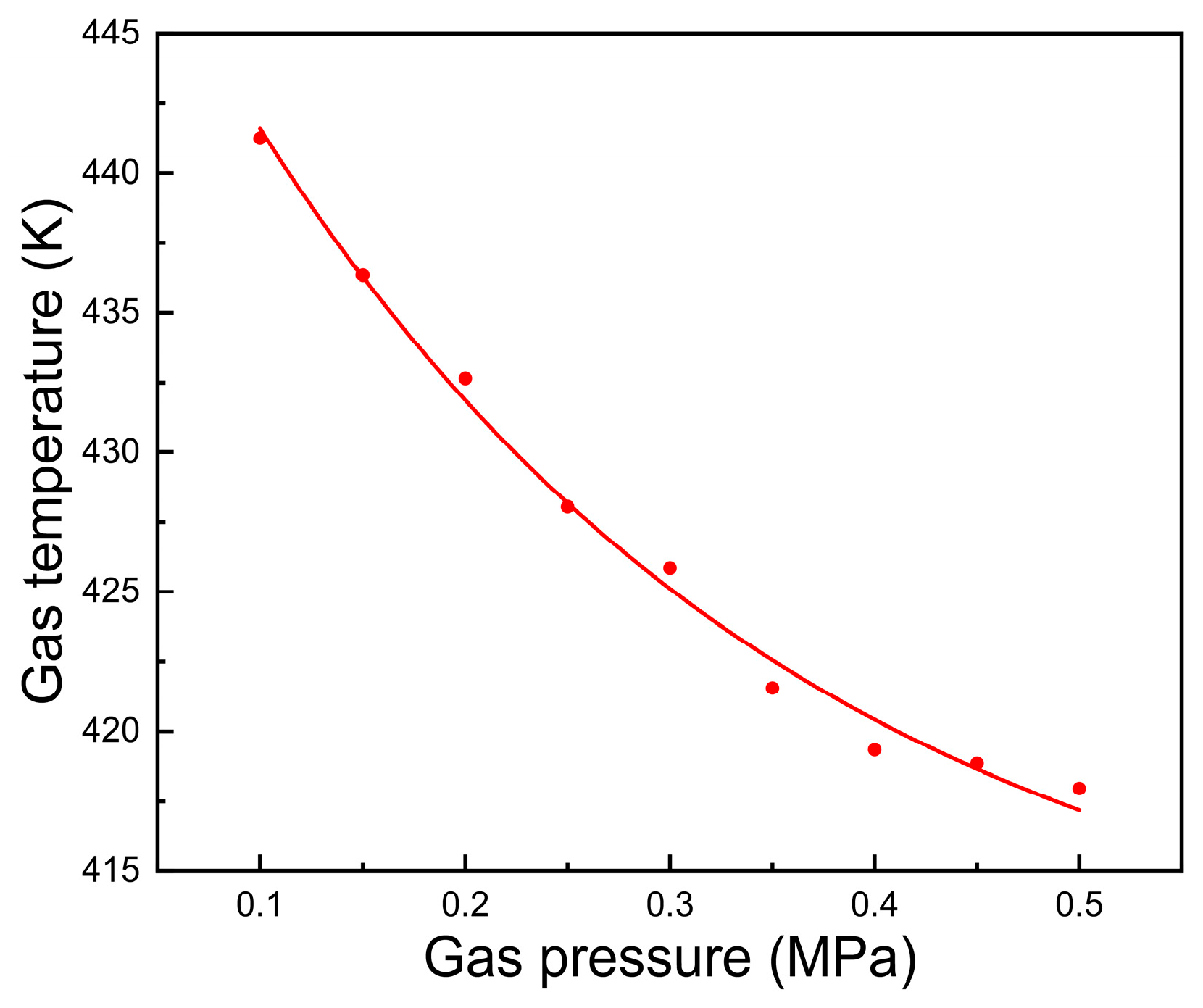

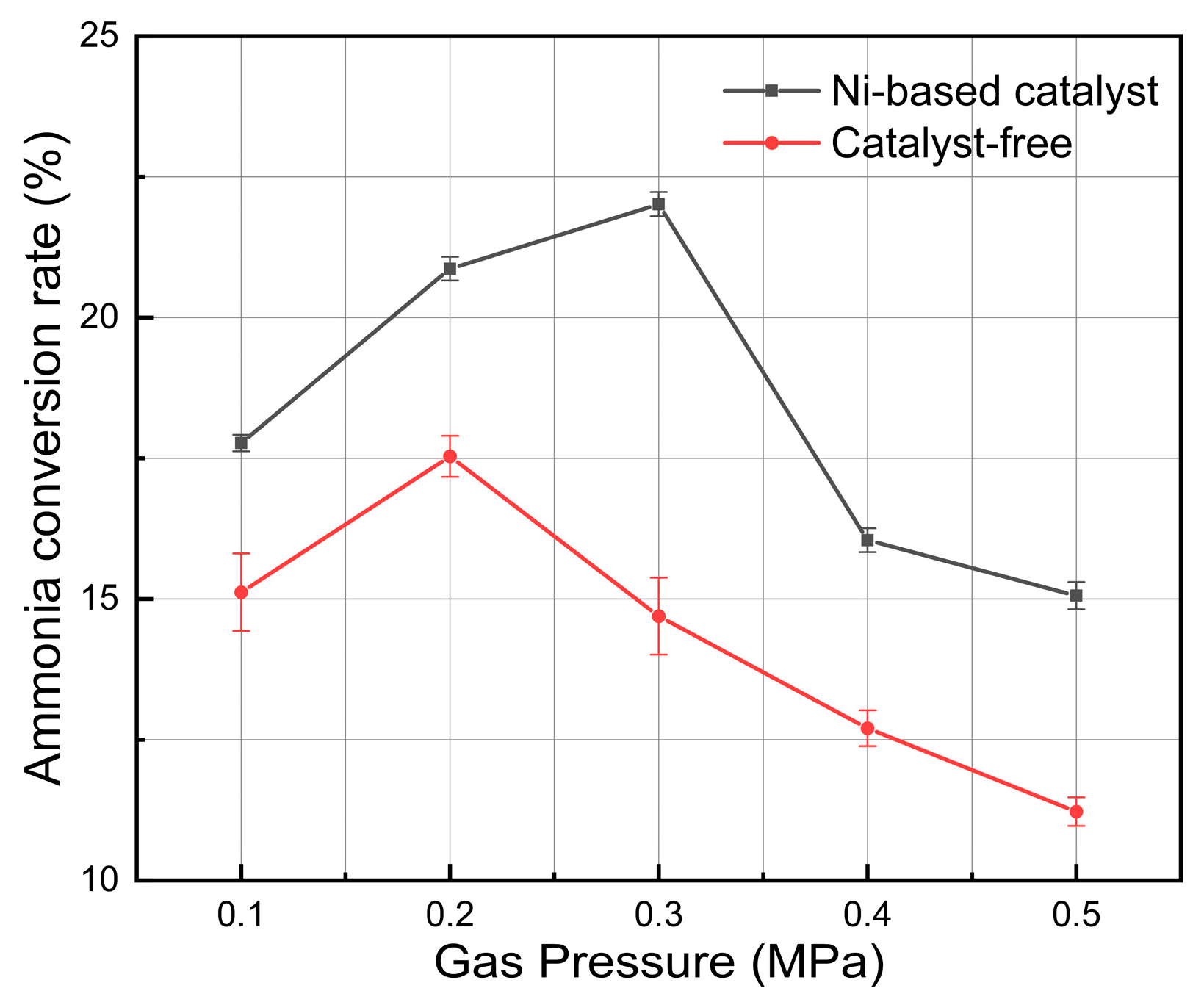

3.4. Effect of Plasma Gas Pressure

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Reduced gas inlet flow greatly increases the residence time of reactants in the plasma active zone, thereby increasing energy input per molecule and cracking efficiency. Increasing discharge power consistently increases the density of high-energy electrons and the production of reactive species in the non-equilibrium plasma, which facilitates effective ammonia molecule dissociation.

- (2)

- The introduction of a catalyst enhances the ammonia cracking efficiency by modifying the reaction kinetics through a dual mechanism: reducing the activation energy of the reaction and promoting the adsorption of reactants.

- (3)

- When the system pressure grew from 0.1 MPa to 0.5 MPa, the ammonia cracking rate first increased and then declined, peaking at about 2 atm, which suggests an existence of an ideal pressure window for ammonia cracking that successfully balances the rate of radical reactions, gas density, and electron energy distribution.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhong, R.; Wei, C.; Zhu, B. Hydrogen energy development in China: Potential assessment and policy implications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Jiang, Z. Overview of hydrogen storage and transportation technology in China. Unconv. Resour. 2023, 3, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; An, R. Research on the coordinated development capacity of China’s hydrogen energy industry chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. The Development Trend of and Suggestions for China’s Hydrogen Energy Industry. Engineering 2021, 7, 719–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B. China’s Clean Energy Transition: Progress and Challenges Ahead. East Asian Policy 2025, 17, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.M.; Nemah, A.K.; Al Bahadli, Y.A.; Kianfar, E. Principles and performance and types, advantages and disadvantages of fuel cells: A review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10, 100920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenina, I.A.; Yaroslavtsev, A.B. Prospects for the Development of Hydrogen Energy. Polymer Membranes for Fuel Cells and Electrolyzers. Membr. Membr. Technol. 2024, 6, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge-Palacios, M.; Zhang, X.; Morlanes, N.; Nakamura, H.; Pezzella, G.; Sarathy, S.M. Ammonia pyrolysis and oxidation chemistry. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2024, 105, 101177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauret, F.; Ji, J.; Kinzel, P.; Saxén, H.; Baniasadi, M. Ammonia as a Green Energy Carrier to Lower Blast Furnace CO2 Emissions. ISIJ Int. 2025, 65, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, D.; Lu, Q.; Sakaushi, K.; Zhang, X. Advanced cold plasma-assisted technology for green and sustainable ammonia synthesis. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 154920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.C.; Chung, H.K. Enhanced hydrogen production through cracking of ammonia water using liquid plasma on titanate-based perovskite catalysts. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 311, 118509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakurt, B.; Zhu, H.; Soydal, O.; Sun, G.; Luterbacher, J.S.; Matioli, E. Low-Power Tunable Micro-Plasma Device for Efficient and Scalable CO2 Valorization. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2507687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.-B.; Jeong, H.-B.; Yang, J.-H.; Vinu, A.; Lee, B.-H.; Jeon, C.-H. Enhanced hydrogen production from polypropylene via NiO/Zeolite Y catalyzed high-pressure pyrolysis: Effects of pressure and methanation reactions. J. Energy Inst. 2025, 121, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, H.; Zhao, B. Negative corona plasma and its synergistic catalytic effect with Fe-based catalyst on hydrogen production via ammonia decomposition. J. Northwest Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 47, 526–532. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.; Zhou, R.; Zhou, R.; Liu, B.; Zhang, T.; Xian, Y.; Cullen, P.J.; Lu, X.; Ostrikov, K. Sustainable ammonia production by non-thermal plasmas: Status, mechanisms, and opportunities. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 421, 129544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, Y.; Kambara, S.; Miura, T. Hydrogen production from ammonia by the plasma membrane reactor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 32082–32088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, L.; Zhang, W.; Ding, J.; Li, J. Instantaneous hydrogen production from ammonia by non-thermal arc plasma combining with catalyst. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 4064–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, A. Derivation of the Paschen curve law. In ALPhA Laboratory Immersion; Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Masumbuko, R.K.; Kobayashi, N.; Suami, A.; Itaya, Y.; Zhang, B. Effect of High Voltage Electrode Material on Methanol Synthesis in a Pulsed Dielectric Barrier Discharge Plasma Reactor. Catalysts 2024, 14, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolas, N.; Yetter, R.A. Kinetics of plasma assisted pyrolysis and oxidation of ethylene. Part 1: Plasma flow reactor experiments. Combust. Flame 2017, 176, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Zhu, F.; Bo, Z.; Cen, K.; Tu, X. Non-oxidative decomposition of methanol into hydrogen in a rotating gliding arc plasma reactor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 15901–15912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, R.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Mu, H.; Zhang, G.; Yu, J.; Huang, Z. Stability and emission characteristics of ammonia/air premixed swirling flames with rotating gliding arc discharge plasma. Energy 2023, 277, 127634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morillo-Candas, A.S.; Klarenaar, B.L.M.; Guerra, V.; Guaitella, O. Fast O atom exchange diagnosed by isotopic tracing as a probe of excited states in nonequilibrium CO2–CO–O2 plasmas. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 6135–6151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yan, B.; Jin, Y.; Cheng, Y. Non-thermal arc plasma combined with NiO/Al2O3 catalyst for hydrogen production from ammonia decomposition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 10234–10245. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, B. Gliding arc discharge plasma assisted decomposition of ammonia into hydrogen. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2011, 39, 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Soucy, G.; Jurewicz, J.; Boulos, M.I. Kinetic and spectroscopic analysis of NH3 decomposition under R.F. Plasma at moderate pressures. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 1995, 15, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, M.; Aihara, K.; Sawaguchi, T.; Matsukata, M.; Iwamoto, M. Ammonia decomposition to clean hydrogen using non-thermal atmospheric-pressure plasma. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 14493–14497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Guo, H.; Gong, W. Enhancing the ammonia to hydrogen (ATH) energy efficiency of alternating current arc discharge. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 7655–7663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogungbemi, E.; Ijaodola, O.; Khatib, F.N.; Wilberforce, T.; El Hassan, Z.; Thompson, J.; Ramadan, M.; Olabi, A.G. Nonthermal plasma-assisted catalysis NH3 decomposition for COx-free H2 production: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 56, 452–470. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, K.; Park, Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Jung, S. Green hydrogen production from ammonia water by liquid–plasma cracking on solid acid catalysts. Renew. Energy 2023, 216, 119068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthanarasimhan, J.; Lakshminarayana, R. Influence of flow regime on the decomposition of diluted methane in a nitrogen rotating gliding arc. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Typical Value | Scope |

|---|---|---|

| P/W | 40 | 20~60 |

| f/Hz | 20 | 20 |

| q(NH3)/(L·min−1) | 1 | 0.5~1.5 |

| Plasma Type | Discharge Gas | NH3 Gas Flow Rate (SLM) | Discharge Power (W) | EE (L/kW·h) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF plasma | NH3/Ar/H2 | 27.0 | 13,000 | 56.1 | [26] |

| DBD | NH3 | 0.5 | 400 | 9.3 | [16] |

| DBD | NH3 | 0.00487 | 50 | 8.8 | [27] |

| NTAP | NH3 | 0.2 | 20 | 331.2 | [28] |

| NTAP | NH3 | 1 | 20 | 440.7 | This paper |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lin, Q.; Wu, D.; Gong, J.; Lv, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L. Effects of Plasma Parameters on Ammonia Cracking Efficiency Using Non-Thermal Arc Plasma. Hydrogen 2026, 7, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen7010006

Li Y, Wang Z, Lin Q, Wu D, Gong J, Lv Z, Zhang Y, Chen L. Effects of Plasma Parameters on Ammonia Cracking Efficiency Using Non-Thermal Arc Plasma. Hydrogen. 2026; 7(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen7010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yong, Zhiwei Wang, Qifu Lin, Dianwu Wu, Jiawei Gong, Zhicong Lv, Yuchen Zhang, and Longwei Chen. 2026. "Effects of Plasma Parameters on Ammonia Cracking Efficiency Using Non-Thermal Arc Plasma" Hydrogen 7, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen7010006

APA StyleLi, Y., Wang, Z., Lin, Q., Wu, D., Gong, J., Lv, Z., Zhang, Y., & Chen, L. (2026). Effects of Plasma Parameters on Ammonia Cracking Efficiency Using Non-Thermal Arc Plasma. Hydrogen, 7(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen7010006